Introduction

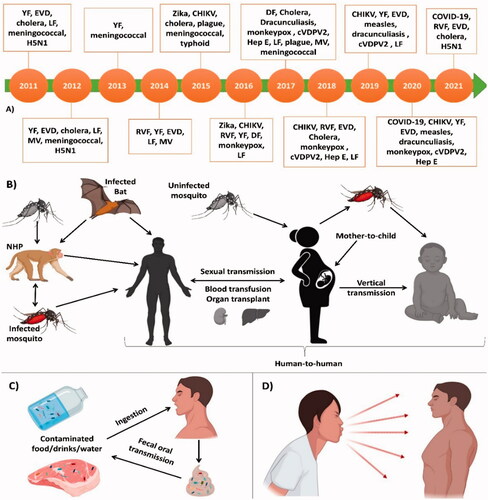

Emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) has been defined as infections that newly appear within a population or pre-existed but are now rapidly increasing in incidence or geographic range [Citation1]. Africa is known to be home to not only emerging and but also re-emerging infectious diseases. Most of those emerging infectious diseases that cause death to humans are presumed to originate from Africa [Citation2]. Classical examples of emerging infectious diseases that caused public health burdens in the past decade across Africa include tuberculosis, Ebola, malaria, measles, Yellow fever, Rift Valley fever, Zika virus, chikungunya virus, and the recently emerged severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [Citation2–5]. presents a detailed summary of EIDs in Africa, while a timeline of EIDs in Africa in the past decade is shown in .

Figure 1. Disease outbreak and transmission modes: (A) Timeline of disease outbreaks in Africa according to WHO’s Disease Outbreak News (Disease Outbreak News (who.int)). (B) Disease transmission to humans by animals and human-to-human transmission. (C) Disease transmission by the faecal-oral route. (D) Respiratory disease transmission route. COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; DF: Dengue fever; LF: Lassa fever; YF: Yellow fever; CHIKV: Chikungunya virus; MV: Marburg virus; Hep E: Hepatitis E; EVD: Ebola virus disease; HFN1: Avian influenza; cVDPV2: Circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus 2; NHP: Non-human primates.

Table 1. Emerging Infectious Diseases in Africa.

Similar to global EIDs, the majority of Africa’s EIDs originate from (wild) animal reservoirs, and are transmitted to humans by vectors like ticks, midges, and mosquitos () [Citation26]. Africa also shares the same factors including demographic change, global travel and trade, and climate change as drivers for EIDs [Citation2,Citation3,Citation11].

African countries are at a disadvantage compared to the rest of the world when it comes to preparedness to cope with EIDs [Citation2,Citation27,Citation28]. Some of the factors contributing to these disadvantages include political instability, economic insecurity, and mass population displacements that have led to the collapse of many health systems that are responsible for the management of EIDs [Citation27]. Also, Africa lacks proper disease surveillance systems that will help manage, predict, and prevent future emerging infectious diseases. Poverty and dependence on foreign countries to fund research related to EIDs also slow Africa’s progress in fighting EIDs [Citation2,Citation27]. Routine updates about the state of Africa’s EIDs burden will help different public health officials and researchers to plan well for current and future EIDs outbreaks. This review summarizes opinions from different African experts around the globe on the emerging infectious diseases that affected Africa in the past decade and their suggestions for better future surveillance and control.

Africa's vulnerability and response to emerging infectious diseases in the past decade

Africa, with underdeveloped healthcare system, has raised serious concerns among experts (Africans and non-Africans) on African countries’ ability to keep EIDs under control [Citation29]. There are still significant gaps in the application of the full concepts of the 2005 International Health Regulations (IHR), despite efforts by governments in Africa and their development partners. The core capacities of IHR (i.e. Regulation, Policy and Finance, Coordination and National IHR Focal Point Communication, Surveillance, Response, Preparedness, Risk Communication, Human Resource Capability, Laboratory, Potential Hazards, Points of Entry) continue to fall short in most Sub-Saharan African countries [Citation30]. Joint External Assessment studies from the World Health Organization (WHO) indicate that most Sub-Saharan African countries are not prepared to respond sufficiently to the International Health Regulations’ threat, although epidemics and pandemics perennially plague African regions [Citation31]. Invariably, Africa's experience in the management of serious health emergencies emphasized the fragility of the Africa Health system. Even though recent Africa's response to the COVID-19 pandemic was quick and decisive, with decisions instrumental in keeping the number of cases low on the continent, yet, because of the socioeconomic dynamics in most African nations, these quick measures are unsustainable in the long term [Citation32].

Factors that aggravate an already fragile state of Africa are low Physicians' density and health expenditure. Low physician density is one of the major weaknesses of the health system in Africa, with some health institutions run by assistant medical doctors, clinical officers with only two years of experience, a few registered nurses, and doctors [Citation33]. Similarly, it is a growing concern globally that the shortage of health workers has reached epic proportions, affecting almost all countries across the globe, including Africa [Citation34]. The WHO estimates that a total of 4¼ million health workers are needed to fill the gap [Citation35]. Of the 46 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, only 6 have a workforce density of over 2.5 per 1,000 individuals. That is, the level of health workers in Africa averages 0.8 workers per 1,000 population, which is slightly lower relative to some other regions of the World with an average level of 5 workers per 1,000 population [Citation34].

Emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases are at alarming rates and it has been estimated that half of all deaths in Africa are caused by infectious diseases [Citation2]. Thus, it becomes very pertinent to evaluate Africa’s responses to infectious diseases in the past decade, with the view to ascertaining the correctness of these responses and proffering better approaches in responding to future outbreaks. Most of Africa’s responses to outbreaks in the past decade have had major gaps in surveillance, research and training programs, and the availability of qualified infectious disease professionals [Citation3,Citation36,Citation37]. Many disease surveillance programs in Africa have been of too much paperwork and conflicting instructions, with fewer actions. Furthermore, unlike developed countries where research is the basis of direct interventions and responses to infectious diseases, researches in Africa are less focussed and applied to tackle the rising burden of infectious diseases. Also, the number of qualified personnel at all levels of health in Africa have been low relative to those in other regions of the world.

Africa’s response to EIDs in the past decade has been, in part, that of waiting for emergency interventions and help from developed countries, which costs lives, health and resources [Citation38]. Although, African countries are starting to invest more in their citizens’ health, less than 15 of her countries have institutions that can function as National Public-Health Institutions (NPHIs), i.e. disease surveillance linked with a diagnostic laboratory, and the capacity to activate a rapid-response team for outbreaks and serve as an operation center in public-health emergencies [Citation39].

Economic impacts of emerging infectious diseases in Africa

The emergence and re-emergence of infectious diseases account for huge mortality rates across the globe [Citation40]. For centuries, man has continuously witnessed the insurgence of different kinds of infectious diseases with varying devastating impacts. Across the globe, millions of lives have been lost to these incidences most importantly in the developing nations with poor and inadequate health systems [Citation2,Citation41]. Besides these threats to man, one of the key paradoxes associated with infectious diseases is often its impact on the economy. For instance, the West Africa sub-region during its fight on the Ebola epidemic lost over six billion US dollars while a general estimate of about 15 billion dollars was lost across the globe [Citation42,Citation43].

During global health emergencies, the severity of outbreaks and the economic burden usually depend on the preparedness of a nation and her economic resilience [Citation44]. Most underdeveloped nations are faced with a huge and distorted economic impact; for instance, during the severe influenza pandemic where about 4%–5% loss gross national income was recorded [Citation45]. It was also reported that some countries such as Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia lost about $2.2 billion in their gross domestic products to Ebola in 2015 [Citation46]. Elsewhere, it was reported that $12 Billion was lost to tuberculosis globally [Citation47]. In addition, the World Bank estimated the overall economic impact of the Ebola crisis on Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone at approximately $2.8 billion: $600 million for Guinea, $300 million for Liberia, and $1.9 billion for Sierra Leone [Citation48], this no doubt would have a negative effect on these countries with lean marginal income and poor gross domestic products.

Recently, the incidence of COVID-19 pandemic in sub-Saharan Africa had immense socio-economic impacts with a regional estimated loss of between $37 and $79 billion thereby reducing agricultural production, weakening of supply chains, increasing trade deficit, increasing unemployment and massive job loss, political instability and regulatory/policy bottle necks [Citation5,Citation49]. This, according to the study could spark regional recession by contracting the 2019 growth of 2.4% to between −2.1 and −5.1% in 2020 [Citation50]. In Ghana, the socio-economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in market places were evident with the increase in food prices, the economic hardships associated with the lockdown directive, the forceful relocation and decongestion exercises to enforce social distancing among traders [Citation51,Citation52]. The reductions in net oil export and international oil trade owing to the global pandemic have resulted in $35–$65 billion trade loss in countries whose economy rely solely on oil export such as Angola, Equatorial Guinea and Nigeria. In the tourism industry, a net loss of $5 billion (2.0% of 2018 gross domestic products) has been recorded as it affects hospitalities and aviation/airline travels especially in Ethiopia and Kenya where tourisms contribute mainly to their economy [Citation53]. Generally, sub-Saharan Africa could lose about $200 Billion to the COVID-19 pandemic with over 20 million jobs lost which suggests further social unrest such as rise in terrorism, unemployment, increase in human trafficking, and other social menaces [Citation54,Citation55]. It is therefore suggested that economic woes presented oftentimes by global health emergencies significantly affect both developed and undeveloped economies most importantly in Africa; leading to inflation, trade loss, withdrawal of investors, and a major shift of the budget from developmental projects to the health sector from its lean marginal revenue and taxes generation.

Without a doubt, African nations suffer from the economic consequences and repulsion arising from EIDs which would slow down the growth and developments of the region. Hence, the need for economic recovery intervention programs with thematic goals of reducing unemployment, improvement of total health care systems, political wills and resources management. It is paramount therefore that these challenges which are often faced during global health emergencies are curtailed through policy formulation among member states, regional bodies, and the Africa Union to consolidate on her economic recovery processes.

Recommendations for improved preparedness to future outbreaks

The series of past EID outbreaks in Africa have provided insights into Africa’s preparedness for ongoing and future outbreaks. For adequate preparations for future outbreaks, Africa requires a strengthened Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) and national public health institutions (NPHIs). Strong public health institutions are critical to harmonize and coordinate public health responses across sectors, disciplines, and borders [Citation38]. Moreover, increased investment in the public health workforce, as well as local production of vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics, are strongly recommended. Despite the threats posed by infectious diseases in Africa, it is important to note that the continent only produces 1% of its vaccines and lacks the adequate capacity to manufacture them at scale [Citation38]. Thus, African countries must invest hugely in local vaccine production, including process development and maintenance, production facilities, life cycle management, and product portfolio management [Citation56]. We further provide recommendations to help improve the preparedness and response to future outbreaks in Africa ().

Table 2. Recommendations for Improvement of Africa’s Preparedness and Response to Future Outbreaks.

Concluding remarks

To improve the situation of the current unsatisfying response strategies of Africa to emerging infectious diseases, we suggest strengthened public health surveillance, proper communication between researchers and policy makers, more research and training opportunities for professionals, emphasis on feedback, effective public health infrastructures, and lastly, collaborations of African countries with their neighbours to establish surveillance and lab networks. According to the World Bank, Africa needs between US$2 billion and $3.5 billion per year for epidemic preparedness [Citation39]. Although to fully establish these strategies may take a while, the earlier Africa began to respond appropriately to the rising emergence of infectious, the better for her. In the face of the current pandemic, African nations should appropriate and judiciously use COVID-19 donations from the Africa Union, donor countries and other agencies (foreign and indigenous), including seeking alternatives and indigenous solutions for the much-needed therapy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Morse SS. Factors in the emergence of infectious diseases. Emerg Infect Dis. 1995;1(1):7–15.

- Fenollar F, Mediannikov O. Emerging infectious diseases in Africa in the 21st century. New Microbes New Infect. 2018;26:S10–S18.

- Nyaruaba R, Mwaliko C, Mwau M, et al. Arboviruses in the east African community partner states: a review of medically important mosquito-borne arboviruses. Pathog Glob Health. 2019;113(5):209–228.

- Kalk A, Schultz A. SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in African countries; are we losing perspective? Lancet Infect. 2020;3099:30563–30566.

- Oyejobi GK, Olaniyan SO, Awopetu MJ. COVID-19 in Nigeria: matters arising. Curr Med Issues. 2020;18(3):210–212.

- Keeling PJ, Rayner JC. The origins of malaria: there are more things in heaven and earth. Parasitology. 2015;142(S1):S16–S25.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites -Guinea Worm, www.cdc.gov/parasites/guineaworm. 2020 (accessed 3 June 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Plague, www.cdc.gov/plague/index.html. 2021 (accessed 3 June 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Meningococcal disease, www.cdc.gov/meningococcal. 2020 (accessed 3 June 2021).

- Nelson EJ, Harris JB, Glenn MJ, et al. Cholera transmission: the host, pathogen and bacteriophage dynamic. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(10):693–702.

- Petersen E, Petrosillo N, Koopmans M. Emerging infections-an increasingly important topic: review by the emerging infections task force. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24(4):369–375.

- Kabwama SN, Bulage L, Nsubuga F, et al. A large and persistent outbreak of typhoid fever caused by consuming contaminated water and street-vended beverages: Kampala, Uganda, January–June 2015. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):23.

- World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2020, www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240013131. 2020 (accessed 3 June 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Listeria (Listeriosis), www.cdc.gov/listeria/index.html. 2021 (accessed 3 June 2021).

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Coronavirus (COVID-19), www.afro.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus-covid-19. 2021 (accessed 3 June 2021).

- Posen HJ, Keystone JS, Gubbay JB, et al. Epidemiology of zika virus, 1947–2007. BMJ Glob Health. 2016;1(2):e000087.

- Rohan H, McKay G. The ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: why there is no 'silver bullet'. Nat Immunol. 2020;21(6):591–594.

- Furuse Y, Suzuki A, Oshitani H. Origin of measles virus: divergence from rinderpest virus between the 11th and 12th centuries. Virol J. 2010;7:52.

- Beer EM, Rao VB. A systematic review of the epidemiology of human monkeypox outbreaks and implications for outbreak strategy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(10):e0007791.

- Jorba J, Diop OM, Iber J, et al. Update on vaccine-derived polioviruses-worldwide, January 2015–May 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(30):763–769.

- Mehndiratta MM, Mehndiratta P, Pande R. Poliomyelitis: historical facts, epidemiology, and current challenges in eradication. Neurohospitalist. 2014;4(4):223–229.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lassa fever, www.cdc.gov/vhf/lassa/index.html. 2019 (accessed 3 June 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Marburg (Marburg virus disease), www.cdc.gov/vhf/marburg/index.html. 2021 (accessed 3 June 2021).

- Kayali G, Kandeil A, El-Shesheny R, et al. Active surveillance for avian influenza virus, Egypt, 2010–2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(4):542–551.

- World Health Organization. Disease Outbreak News (DONs), https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news. 2021 (accessed 3 June 2021).

- Jones KE, Patel NG, Levy MA, et al. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature. 2008;451(7181):990–993.

- Shears P. Emerging and re-emerging infections in Africa: the need for improved laboratory services and disease surveillance. Microbes Infect. 2000;2(5):489–495.

- Braack L, De G, Almeida AP, et al. Mosquito-borne arboviruses of African origin: review of key viruses and vectors. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11(1):29.

- El‐Sadr WM, Justman J. Africa in the path of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(3):e11.

- Paintsil E. COVID-19 threatens health systems in Sub-Saharan Africa: the eye of the crocodile. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(6):2741–2744.

- Talisuna AO, Okiro EA, Yahaya AA, et al. Spatial and temporal distribution of infectious disease epidemics, disasters and other potential public health emergencies in the world health Organization Africa region, 2016–2018. Global Health. 2020;16(1):9.

- Senghore M, Savi MK, Gnangnon B, et al. Leveraging Africa's preparedness towards the next phase of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Lancet Glob. 2020;8(7):S2214–109X. 30234:–30235

- Azevedo MJ. The state of health system(s) in Africa: challenges and opportunities. In: Historical perspectives on the state of health and health systems in Africa, volume II. African histories and modernities. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2017. pp.1–73.

- Anyangwe SC, Mtonga C. Inequities in the global health workforce: the greatest impediment to health in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2007;4(2):93–100.

- Chen L, Evans T, Anand S, et al. Human resources for health: overcoming the crisis. Lancet Public Health. 2004;364(9449):1984–1990.

- Mboussou F, Ndumbi P, Ngom R, et al. Infectious disease outbreaks in the African region: overview of events reported to the world health organization in 2018. Epidemiol Infect. 2019;147:e299.

- Otu A, Effa E, Meseko C, et al. Africa needs to prioritize one health approaches that focus on the environment, animal health and human health. Nat Med. 2021;27(6):943–946.

- Nkengasong JN, Tessema SK. Africa needs a new public health order to tackle infectious disease threats. Cell. 2020;183(2):296–300.

- Nkengasong JN. How Africa can quell the next disease outbreaks. Nature. 2019;567(7747):147.

- Bloom DE, Cadarette D. Infectious disease threats in the twenty-first century: strengthening the global response. Front Immunol. 2019;10:549.

- De-Graft AA, Unwin N, Agyemang C, et al. Tackling Africa's chronic disease burden: from the local to the global. Global Health. 2010;6:5.

- Ross AGP, Crowe SM, Tyndall MW. Planning for the next global pandemic. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;38:89–94.

- Gostin LO, Friedman EAA. Retrospective and prospective analysis of the West African ebola virus disease epidemic: robust national health systems at the foundation and an empowered WHO at the apex. Lancet. 2015;385(9980):1902–1909.

- Menzel C. 2017. The Impact of Outbreaks of Infectious Diseases on Political Stability: Examining the Examples of Ebola, Tuberculosis and Influenza, 1996-2014. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/THE-IMPACT-OF-OUTBREAKS-OF-INFECTIOUS-DISEASES-ON-Menzel/735cf727230c68e4e960a46e161eea4377bfb48d. (accessed 3 June 2021).

- Fan V, Jamison D, Summers L. 2016. The inclusive cost of pandemic influenza risks. Working Paper 22137. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Wojda TR, Valenza PL, Cornejo K, et al. The ebola outbreak of 2014–2015: from coordinated multilateral action to effective disease containment, vaccine development, and beyond. J Glob Infect Dis. 2015;7(4):127–138.

- Kim JY, Shakow A, Castro A, et al. Tuberculosis control. In: Smith R, Beaglehole R, Woodward D, et al. (eds) Global public goods for health: health economic and public health perspectives. Oxford University Press for the World Health Organization, New York, 2003. pp.54–72.

- World Bank. The economic impact of the 2014 ebola epidemic: Short- and Medium-Term estimates for West Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2014. p.109.

- Farayibi A, Asongu S. The economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria. Eur Xtramile Cent Afr Stud. 2020. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/228019

- Isaac ON. Africa: COVID 19 and the future of economic integration. Soc Sci Res Netw. 2020. DOI:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3607305

- Smith KM, Machalaba CC, Seifman R, et al. Infectious disease and economics: the case for considering multi-sectoral impacts. One Health. 2019;7:100080.

- Asante LA, Mills RO. Exploring the socio-economic impact of COVID-19 pandemic in marketplaces in urban Ghana. Afr Spectr. 2020;55(2):170–181.

- Tahanout K, Berkane A. Impact of COVID-19 on the tourism industry in Africa and recovery strategies: case of Kenya. Rev Écon Stat. 2021;18:29–44.

- Bisong A, Ahairwe PE, Njoroge E. The impact of COVID-19 on remittances for development in Africa. European Centre for Development Policy Management. https://ecdpm.org/publications/impact-covid-19-remittances-development-africa/. 2020 (accessed 3 June 2021).

- Cutler DM, Summers LH. The COVID-19 pandemic and the $16 trillion virus. JAMA. 2020;324(15):1495–1496.

- Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):475–481.