To the editor,

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly hampered the progression of reducing TB burden and reaching global targets of TB elimination. Along these lines and in the present journal, a recent report from Malaysia focussed on attempts to restore TB services, including online appointment systems for clinical services, drive-through sputum collection and enhancement of mobile radiography tools [Citation1]. We here report our experience on video supported treatment (VST) as a flexible way to monitor tuberculosis (TB) treatment. We conducted an observational evaluation of implementation of VST to routine clinical practice in two university hospitals in a low TB incidence country. Asynchronous VST was carried out by two different methods regarding digital technology and devices used, and health care workers monitoring the VST.

Pulmonary departments of Helsinki University Hospital (HUH) and Tampere University Hospital (TUH) in Finland enrolled TB patients starting asynchronous VST according to their local protocols. Two different technologies were used. In HUH a digital TB solution was implemented by an external company (HealthFOX Ltd) utilising TB Application which was installed to patients’ smartphones (AppVST). Whereas, in TUH technology department carried out digital solutions and provided tablet devices for the patients (TabletVST). In addition to video recording, the smartphone application contained information on disease, nutrition, and physical health. Visual function test was included. TabletVST included only the plain action of recording videos with rec and stop buttons. Both solutions had the live-video function if needed. All patient data, servers, transmissions, and cloud storage were encrypted to ensure data protection. The software was not integrated in the patient record systems. VST was observed remotely via web-based platform by clinical pharmacist (HUH) or TB nurse (TUH) working on the pulmonary ward.

All patients were diagnosed and treated according to the national TB guidelines. Eligible patients for VST were prospectively enrolled from 2018 to 2021. Inclusion criteria were age 18 years or above, communication language Finnish or English, and patient having an own smartphone or capability to use the tablet device provided by the hospital. Patients with multi-drug (MDR) or extensively drug-resistant (XDR) TB or those who were at risk for poor adherence (uncontrolled substance abuse, psychiatric disease, or dementia) were excluded. VST was mainly started on a pulmonary ward. Patients received written instructions of VST and practiced the use of the smartphone app or tablet device before going home. Time frame for recording the video was set for two hours and a reminder popped up when the recording time started. Pill dispensers were used and filled by the clinical pharmacist (HUH) or patients themselves (TUH). Treatment adherence was verified by the proportion of sent videos over agreed VST days including technically corrupted clips. Patients as well VST observers were asked to fill in a feedback questionnaire after VST completion. Patients were given an informed consent form. Protocols were approved by the ethics committee of Tampere University Hospital.

To test the equality of the distributions of treatment adherence in different subgroups defined by categorical variables sex, birth country, employment or device, Wilcoxon rank-sum test or Kruskal-Wallis test was used. Spearman correlation coefficient was calculated to estimate a strength of monotonical association between treatment adherence and age. Due to small number of observations multivariable model was not build. Calculations were done with Stata program version 17.0, StataCorp, College Station, TX 7784 USA.

Altogether 31 patients were recruited in two hospitals during the implementation period. One patient in HUH was excluded after discontinuing the treatment because of negative cultures and no verification of TB diagnosis. Thus, 30 patients accomplished VST. Baseline characteristics of the patients are presented in . Four patients had resistance to 1–3 drugs (isoniazid, ethambutol, streptomycin). None of the patients had HIV-infection. Tuberculosis was confirmed by culture in 26 patients and by PCR in 3 patients. Treatment outcome was good in 93% of the cases. In one case treatment was interrupted due to severe adverse effects. In one culture-negative case treatment was continued as a TB preventive treatment (TPT) after two months, when no treatment response with full TB medication was detected. Hence, the precedingly accumulated data was included in the study.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the patients carrying out AppVST and TabletVST.

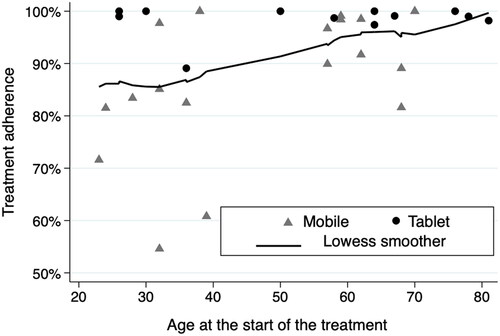

The mean percentage of sent videos was 87% (range 55–100%) for patients monitored by AppVST and 98% (range 97–100%) for those observed via TabletVST. Further, treatment adherence for all patients was 91%. Individual proportions of the sent videos are presented on the . Adherence to VST was on a good level irrespective of age, over 80% in 27/30 cases. Commitment was < 65% with two foreign-born patients regardless of repeated reminders and motivation. In addition, one patient had severe nausea due to TB medication and refused to take the medications as ordered. She was admitted to the hospital and the medication was restarted gradually. Statistically significant association between treatment adherence and sex (p = 0.93), age (p = 0.10), country of birth (p = 0.49) or employment (p = 0.30) was not detected. The distribution of treatment adherence differed slightly between tablet users (mean 98%) and smartphone users (mean 87%), p = 0.0025.

In Finland DOT is traditionally carried out five times a week during business days. Thus 71% of the treatment days are observed. Cloud-based video monitoring enables observing of 100% of the treatment days while patients can work, study and travel. Videos can flexibly be recorded with smartphone even abroad. Video applications also include regular reminders which improves adherence.

In total, 18 out of 30 patients filled in feedback questionnaires. All of them would have chosen VST over DOT and all except one would have recommended it to other patients. TB nurses and clinical pharmacists noticed several advantages in VST. Most patients were self-reliant and mutual trust for treatment completion was high. Asynchronous VST enabled shift workers and young people record videos at any agreed time of the day, while observers could check the videos at suitable timeframe during their working days. Further, during COVID pandemic patients with immunosuppressive condition or multiple diseases avoided DOT visits at outpatient clinics. Elderly patients generally needed more technical education, and younger patients repeated motivating to carry out the treatment course. VST workers would have recommended DOT for four patients who needed strong support due to severe adverse events from TB drugs or various problems with other diseases.

Video supported treatment (VST) has world-widely been promoted to support patient-centred treatment [Citation2]. VST can be arranged with synchronous or asynchronous method [Citation3]. There are plenty of previous studies on video supported treatment of tuberculosis patients both in high- and low-resources settings [Citation3–8]. In countries with low TB burden the results have been similar to ours [Citation5,Citation9]. In high-burden countries with low-resources VST has also proven to be a feasible method [Citation4,Citation7,Citation8]. As far as we know, our study is the second study in Scandinavian countries evaluating VST in TB management. In the Norwegian study a real-time recording was used. The treatment adherence in our study was slightly better, 91% versus 76% [Citation5]. They experienced technical problems in 8,9% of the live video calls which reduced treatment motivation and contributed to returning to DOT with 2 out of 17 patients. In our study 9,4% of the recordings included technical problems. However, detected recording attempts were interpreted as sent video clips after quick confirmation of medication intake by chat or phone call. Further, technical malfunctions were solved without delays. This might explain why patients were content with asynchronous VST despite occasional technical problems. In one real-life study comparing VST to DOT, patients receiving VST were on average younger than those receiving DOT (46 vs. 61 years) [Citation10]. Our study provides practical evidence on VST functioning well with elderly patients.

Treatment adherence was slightly better with TabletVST compared to AppVST. The reason for that could be the technical differences of VST methods. Both solutions were easy to use but TabletVST even simpler. Further, during the study TB nurse had no more than four patients concurrently to observe and she phoned to patients regularly, whereas pharmacist monitored simultaneously 5–15 patients. One explanation might be that patients using AppVST were somewhat younger and more often foreign-born.

This study had some limitations. Due to low incidence of TB (3,0/100 000) in Finland, study population was small, leading to small number of observations and limited statistical power. However, patients participating video supported treatment represented well the spectrum of TB cases detected in a real-world setting. Platform of the AppVST was further adjusted towards the end of VST implementation to improve monitoring and shorten observation time. Features such as colour-coded graphics for follow up and automatic calculation of the treatment days and missed videos, were added to the worker’s platform. However, patient’s application remained stationary, and therefore this did not influence patients’ adherence to treatment.

Both asynchronous VST methods have their advantages. AppVST application contains information on tuberculosis, as well as guidance on nutrition and exercise. Patients can perform an Ishihara vision test and track remaining treatment days independently. However, our patients seldom used supplemental material, which might be explained by the disease itself and its treatment requiring their essential attention. The chat feature was fluent for short communications, and with improved platform it enabled a follow up to 15 patients concurrently by one pharmacist. Regular phone calls might be more effective for those patients needing more comprehensive support. This was the communication method with TabletVST. Tablet device is simple to use with only buttons to turn on and off recording. This is particularly important for the elderly and those who do not own smartphone or have modest language skills. However, regardless of the video application patients needed frequent feedback of the quality of the videos. Also, similar determined actions as in DOT were necessary to enhance adherence when videos were missing. Beneficial in both methods was that, as observers were working in the hospital, information of any detected problems reached treating clinicians quickly.

In low-incidence countries new entrants in digital health care increase continuously and various video-aided treatment solutions are available for professionals. VST software can be operated concurrently with various patient record systems. In an ideal situation asynchronous VST is integrated with nationally shared patient record system, but in Finland this kind of setting is not yet achievable.

In conclusion, patients achieved a high 91% treatment adherence with asynchronous VST applications. Patients were content with digital technology regardless of age. Satisfaction of patients and health care personnel for VST was at good level. Asynchronous video supported treatment is a flexible tool to monitor TB treatment of adult patients. It can be implemented in various ways regarding digital technology and workers observing the treatment. Hence, in an optimal situation asynchronous video application could be elected according to patients’ individual needs and health care resources available.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the pulmonary clinics of Helsinki and Tampere University Hospitals and pharmacists Liina Veissi and Nina Vara as well as TB nurses Merja Laitala and Marianne Helander for the contribution to implementing VST in clinical practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Tok PSK, Kamarudin N, Jamaludin M, et al. Effect of COVID-19 on tuberculosis notification in Johor bahru, Malaysia. Infect Dis. 2022;54(3):235–237.

- World Health Organization. Handbook for the use of digital technologies to support tuberculosis medication adherence. WHO/HTM/TB2017.30

- Garfein RS, Doshi RP. Synchronous and asynchronous video observed therapy (VOT) for tuberculosis treatment adherence monitoring and support. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2019;17:100098.

- Ravenscroft L, Kettle S, Persian R, et al. Video-observed therapy and medication adherence for tuberculosis patients: randomised controlled trial in Moldova. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(2):2000493.

- Bendiksen R, Ovesen T, Asfeldt AM, et al. Use of video directly observed treatment for tuberculosis in Northern Norway. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2020;140(1)

- Truong CB, Tanni KA, Qian J. Video-Observed therapy versus directly observed therapy in patients with tuberculosis. Am J Prev Med. 2022;62(3):450–458.

- Sekandi JN, Buregyeya E, Zalwango S, et al. Video directly observed therapy for supporting and monitoring adherence to tuberculosis treatment in Uganda: a pilot cohort study. ERJ Open Res. 2020;6(1):00175–2019.

- Sinkou H, Hurevich H, Rusovich V, et al. Video-observed treatment for tuberculosis patients in Belarus: findings from the first programmatic experience. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(3):1602049.

- Story A, Aldridge RW, Smith CM, et al. Smartphone-enabled video-observed versus directly observed treatment for tuberculosis: a multicentre, analyst-blinded, randomised, controlled superiority trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10177):1216–1224.

- Perry A, Chitnis A, Chin A, et al. Real-world implementation of video-observed therapy in an urban TB program in the United States. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2021;25(8):655–661.