Abstract

Background

There is a very large body of publications discussing the management of patients with an acute sore throat. Advocates for a restrictive antibiotic policy and advocates for a more liberal use of antibiotics emphasise different and valid arguments and to date have not been able to unite in a consensus. Contradicting guidelines based on the same body of knowledge is not logical, may cause confusion and cause unwanted variation in clinical management.

Methods

In multiple video meetings and email correspondence from March to November 2022 and finally in a workshop at the annual meeting for the North American Primary Care Group in November 2022, experts from different countries representing different traditions agreed on how the current evidence should be interpreted.

Results

This critical analysis identifies that the problem can be resolved by introducing a new triage scheme considering both the acute risk for suppurative complications and sepsis as well as the long-term risk of developing rheumatic fever.

Conclusions

The new triage scheme may solve the long-standing problem of advocating for a restrictive use of antibiotics while also satisfying concerns that critically ill patients might be missed with severe consequences. We acknowledge that the perspective of this problem is vastly different between high- and low-income countries. Furthermore, we discuss the new trend which allows nurses and pharmacists to independently manage these patients and the increased need for safety netting required for such management.

Introduction

An acute sore throat is a common reason for visits to a health-care provider, most often in primary health care [Citation1–3]. A multitude of reasons, such as fear of complications and patient demand, results in an overprescription of antibiotics in patients with this condition [Citation4].

Guidelines and the remaining problem

All sore throat guidelines in high-income countries recommend being restrictive with antibiotics [Citation5,Citation6]. Furthermore, almost all guidelines focus on group A beta-haemolytic Streptococcus (GAS) [Citation7,Citation8]. However, in several aspects, the advice of guidelines on the management of patients with an acute sore throat varies widely [Citation4,Citation9–11]. One major distinction is recommendations to use or refrain from using point-of-care testing (POCT) to detect the presence of GAS [Citation11]. Contradicting guidelines based on the same body of knowledge is not logical, may cause confusion and cause unwanted variation in clinical management [Citation4,Citation10]. A consensus between experts from different countries representing different traditions is therefore needed and this critical analysis aimed to reach such consensus.

Methods

The first author R.G. took the initiative to invite general practitioners from Europe and the USA with long experience in research and policy-making on management of the acute sore throat. R.G. also invited co-author R.C. to represent the hospital’s perspective. All invited researchers had previously made extensive contributions to current evidence and also represented differences of opinion on best management of these patients. The aim was to explore to what extent diverging opinions could be merged into a common ground.

Initially, a number of video meetings and email discussions were held to clarify the difference of opinions. Further discussions aimed to find pathways to a common ground on how to interpret current evidence. Video meetings and email discussions took place from March to November 2022 and finally in a workshop at the annual meeting for the North American Primary Care Group in Phoenix in November 2022 where all authors agreed on a common ground as outlined in the following sections.

Results and discussion

Aetiology of acute sore throat

In patients with an acute sore throat various viruses are found in approximately 30% of cases, GAS in 7–30%, and no potential pathogen is identified in approximately 30% [Citation12,Citation13]. Studies in recent decades found that bacteria like Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis [Citation14], Fusobacterium necrophorum and other bacteria are also frequently found in adolescents and young adult patients with a sore throat [Citation13,Citation15–18].

Few healthy adults harbour GAS [Citation12]. Hence, when found in an adult with a sore throat it is likely to be the aetiologic agent rather than a commensal (). Children carry GAS as a commensal much more often than adults. Hence, GAS in the throat of a child with a sore throat is less likely to represent the aetiology than in adults ().

Table 1. Probability that a potentially pathogenic bacteria detected in someone with a sore throat is linked to the symptoms.

Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis is a new definition of strains including those group C and G Streptococci now considered to be potential pathogens in humans. Some strains of group C Streptococci previously considered potential pathogens in humans are not included in S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis since their pathogenicity in humans has been reconsidered [Citation14]. The key question is to what extent these bacteria are causative and to what extent they are merely a coincidental finding of a temporary commensal bacteria [Citation23]. Patients with a sore throat harbouring S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis have similar symptoms as those with GAS indicating that S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis is of some importance [Citation17]. Case-control studies, analysing the prevalence of bacteria in symptomatic patients as well as in healthy controls, conclude that S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis in adolescents and adults with an apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat is of some importance () [Citation14]. Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis is probably unimportant in children with an apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat () [Citation14].

Fusobacterium necrophorum has gained increasing interest and is of importance in a few critically ill patients as well as in some adolescent or young adult patients with a potentially complicated acute sore throat. Case-control studies also conclude that F. necrophorum in adolescents and adults with an apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat is of some importance () [Citation21].

Complications and sequelae after a sore throat

A sore throat is usually a self-limiting illness and without antibiotic treatment, roughly four out of five patients are well within 1 week [Citation24].

A sore throat can occasionally lead to suppurative complications, such as peritonsillar abscess (quinsy) and in rare cases otitis media, sinusitis and sepsis [Citation25]. Skin infections may also occur, predominantly in low-income settings. Suppurative complications are primarily linked to GAS but also to F. necrophorum in adolescents and young adults with quinsy [Citation25]. The most feared, but rare, complication associated with F. necrophorum is the Lemierre Syndrome characterised by internal jugular suppurative thrombophlebitis with metastatic emboli mostly commonly to the lung [Citation26]. Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis is less frequently linked to suppurative complications compared to GAS and F. necrophorum [Citation25]. Clinical scoring such as Centor scores [Citation27,Citation28], McIsaac scores [Citation27,Citation29,Citation30] or FeverPain scores [Citation17,Citation31] do not reliably predict acute suppurative complications [Citation32].

Non-suppurative complications, linked primarily to GAS, include rheumatic fever and glomerulonephritis. Rheumatic fever and subsequent rheumatic heart disease is a feared complication that leads to many fatalities, mostly in children and young adults in low-income countries [Citation33]. Although the risk for rheumatic heart disease remains high in most low-income countries it has declined steeply in high-income countries where it has almost vanished. However, rheumatic fever may still have to be considered in high-income countries in a few high-risk individuals such as immigrants from low-income countries, and homeless persons as well as in some first nations people [Citation33]. Antibiotic treatment of patients with a sore throat reduces the rate of subsequent rheumatic fever in settings where the risk for rheumatic fever is high [Citation34–37]. Adherence to secondary prophylaxis after one episode of rheumatic fever was very high in a controlled trial with extensive monitoring [Citation37]. However, in routine health care, adherence to secondary prophylaxis is very poor [Citation38,Citation39], emphasising the importance of primary prevention in settings with high risk for rheumatic fever.

Antibiotic treatment of patients with an acute sore throat

The many potential adverse effects of antibiotics and concerns about increasing antibiotic resistance make it important to target antibiotics to patients where the benefits outweigh the adverse effects [Citation4].

Most empirical studies show that antibiotics reduce acute symptoms more frequently in adult patients harbouring GAS than in those who do not [Citation24]. Antibiotic treatment for children harbouring GAS seems to reduce recurrences [Citation40]. There is mixed evidence for reducing acute symptoms in children harbouring GAS. Two studies showed an effect of antibiotics [Citation41,Citation42] while one did not [Citation43]. There are several studies presenting results in both children and adults showing that antibiotics reduced acute symptoms if GAS was present [Citation44–46].

In adult patients with S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, two studies showed a borderline effect (p = .05 and p = .049) on reducing acute symptoms [Citation47,Citation48], and it is likely that S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis are, at least partly, responsible for the effect of antibiotics observed when GAS is not present in a Cochrane review [Citation24]. There are no studies exploring the effect of antibiotics on acute symptoms in children harbouring S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis.

It has been suggested that antibiotic treatment of patients harbouring F. necrophorum and with apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat may reduce the incidence of the serious Lemierre’s syndrome [Citation49], although no published studies support this suggestion.

In summary, the strongest evidence for an effect of antibiotics on symptoms in patients with an acute sore throat is reported in adult patients harbouring GAS. The evidence is weaker in children harbouring GAS and in adults harbouring S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis. There is no evidence for an effect of antibiotics on duration or intensity of acute symptoms in children harbouring S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis nor in adolescents and young adults harbouring F. necrophorum.

In light of current evidence, antibiotic treatment, when deemed necessary, should in most cases target patients with GAS present in throat swabs. For some patients with a potentially complicated acute sore throat, it may be relevant to also cover S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis and F. necrophorum.

Identifying patients with GAS

Different scoring algorithms, such as the Centor scores [Citation27,Citation28], the FeverPAIN scores [Citation17,Citation31] and the McIsaac scores [Citation27,Citation29,Citation30] were developed to identify patients with high, moderate or low probability of harbouring GAS (). The ability of clinical scoring algorithms to discriminate between patients with or without GAS may not be optimal when algorithms are used as standalone methods [Citation4,Citation50,Citation51].

Table 2. Scoring algorithms predicting the presence of beta-haemolytic Streptococcus (BHS) in patients with an acute sore throat.

Throat swabs can identify potentially pathogenic bacteria such as GAS. However, swab samples sent to a laboratory for analysis are disadvantaged by the long delay in obtaining the result [Citation52]. Modern high-quality POCTs have a high sensitivity and specificity, on par with conventional culture [Citation4], and a result is available within a few minutes [Citation53–55].

Myths and misconceptions about the use of POCT to detect GAS have been described previously [Citation4]. The take-home message is that most POCT will be negative, ruling out the presence of GAS and GAS as aetiology. This may reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in patients with an apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat and this is the primary reason for using a POCT [Citation4,Citation54,Citation55]. Identifying GAS is a secondary function of POCT that may be beneficial in adults but may work less well in children due to the higher proportion of carriers of GAS () [Citation4,Citation54,Citation55].

Acute triage of patients with an acute sore throat

Triage of patients attending with acute sore throat is currently common practice in many clinics. The content of triage schemes varies, but most focus on identifying patients with higher probability of harbouring GAS. However, the rate of antibiotic prescribing remains high despite guidelines advising against and this warrants a clarification of appropriate triage. We aimed to present a new triage scheme, including an appropriate safety netting, that may contribute to a reduction in the current high levels of antibiotic prescribing.

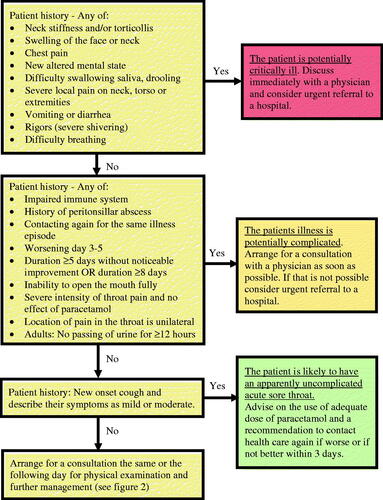

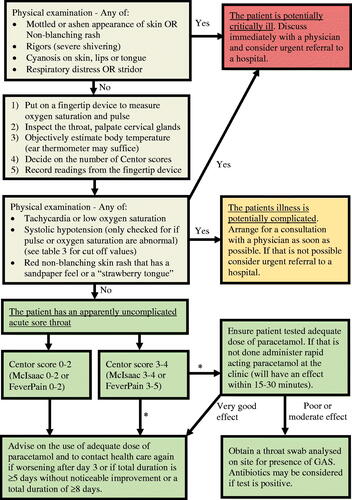

We postulated that failure to clearly distinguish patients with apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat from those with potentially complicated acute sore throat significantly contributes to overprescribing of antibiotics. Hence, we propose a new triage scheme for patients with acute sore throat to initially detect those with risk for suppurative complications or sepsis (, and ) as well as those with risk for later sequelae such as rheumatic heart disease (). This assessment leads to a different management depending on their risk for acute suppurative complications as well as their later risk for rheumatic fever. Failure to differentiate between patients with apparently uncomplicated versus potentially complicated acute sore throat will most likely result in too many patients being managed as if they are potentially complicated which leads to unnecessary antibiotic prescribing.

Figure 1. Initial triage of patients in a setting with low risk for rheumatic fever (can be done in a phone or video consultation).

Figure 2. Further assessment and management of patients in a setting with low risk for rheumatic fever (requires a physical visit).

*Some policymakers recommend no antibiotic use, irrespective of the presence of GAS, for patients with an uncomplicated acute sore throat while other policymakers allow a limited use. Policymakers should decide which of these two alternative pathways to recommend in their guidelines.

Table 3. Levels of acute risk for suppurative complications and sepsis in patients attending with a sore throat.

Table 4. Classification of patients attending with an acute sore throat.

Management of patients with low risk for rheumatic fever

In most patients, acute sore throat will be classified as apparently uncomplicated. However, some patients will have a potentially complicated acute sore throat. Rarely, there are patients who may develop critical illness () and require immediate transfer to a hospital with facilities for intensive care.

Apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat

Fortunately, most patients in any country have apparently uncomplicated acute sore throats, the green column in and (and green boxes in and ). The main goal in management is to reduce antibiotic use, provide symptomatic relief and, where relevant, to reduce the risk of developing rheumatic fever. Reducing acute symptoms can often be achieved with adequate doses of analgesics [Citation45,Citation56].

There are two principally different approaches to antibiotic prescribing to patients attending with apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat. One wait-and-see approach recommends no antibiotic use irrespective of the presence of GAS while the other recommends the use of antibiotics to a few selected patients harbouring GAS to reduce acute symptoms where analgesics are insufficient. There is no definite evidence to recommend one approach over the other.

Gunnarsson et al. [Citation4] explored nine different strategies for managing patients with apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat to identify a restrictive antibiotic use for clinical practice. They recommended that patients with apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat and low risk for rheumatic fever are provided with analgesics as part of a decision tree where antibiotics should only be considered if symptoms are poorly controlled (e.g. significant pain, fever, malaise) after adequate analgesics (e.g. full doses of rapid-acting paracetamol), 3–4 Centor scores [Citation27,Citation28] (or 3–5 FeverPAIN scores [Citation17,Citation31] or 3–4 McIsaac scores [Citation27,Citation29,Citation30]) and POCT confirms the presence of GAS. It should be noted that Gunnarsson et al. [Citation4] assumed 2–3 FeverPAIN scores is equivalent to 3–4 Centor scores but it is more correct to assume that 3–5 FeverPAIN scores is equivalent to 3–4 Centor scores [Citation57].

The strategy recommended by Gunnarsson et al. for patients with apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat at low risk for rheumatic fever, and assuming the analgesic strategy is effective in approximately 40% of patients [Citation56], would require that only 10–15% of patients be tested for GAS and only 3.5–6.6% would be prescribed antibiotics (which is 8–10 times lower than what we see today) [Citation4]. Expressed inversely; 85–90% of these patients do not require a POCT and 93–97% do not require antibiotics. This strategy could be considered a most restrictive policy while still allowing use of antibiotics in a few patients with apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat.

The use of POCT to detect GAS will reduce overall antibiotic prescribing by approximately 25% in patients with acute sore throat [Citation58]. However, the purpose of using POCT is not only to reduce overall antibiotic prescribing but also, perhaps more importantly, to target antibiotic prescribing to patients harbouring GAS [Citation4,Citation59].

To be practical, but at the same time act safely, we suggest an initial triage () that for some patients is followed by an in-person visit (). As seen in , clinical scores for the presence of GAS such as Centor, McIsaac or FeverPAIN, are mainly relevant after the patient is deemed to have an apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat and if any antibiotic use is allowed. An important message in and is that patients with apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat and low clinical scoring should neither be tested nor prescribed antibiotics. Those with a higher clinical score can either be tested, and treated if the POCT is positive, or a wait-and-see strategy could be used.

Whether or not patients initially deemed to have uncomplicated acute sore throat are prescribed antibiotics they should always be instructed to contact a health-care provider again if symptoms are worse on day 3 after start of their illness or with no noticeable improvement after 5 days or have a total duration of ≥8 days. They should be classified as having potentially complicated acute sore throat if they return unwell and are initially evaluated and triaged by a nurse or pharmacist (). A physician may after assessment reclassifies the condition as apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat.

Potentially complicated acute sore throat

Patients with potentially complicated acute sore throat require assessment by a physician to explore the presence of potential complications or diagnoses requiring special action. Certain symptoms suggest the possibility of suppurative complications indicating a potentially complicated acute sore throat (). Warning signs are worsening symptoms after 3 days (also after antibiotics), inability to open the mouth fully, unilateral neck swelling, rigours (shaking chills which have a high odds ratio for bacteraemia) and dyspnoea. Patients with these symptoms require careful investigation, often including imaging and it may be relevant to test for the presence of F. necrophorum or S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, especially in adolescents and young adults. The most common serious suppurative complication is peritonsillar abscess. It occurs most frequently in adolescents and young adults (approximately 15–30 years old). The very rare Lemierre Syndrome should be kept in mind in very few cases with rapid deterioration.

Some patients have a longer duration of sore throat and symptoms of fatigue (). In these patients, with potentially complicated acute sore throat, one should consider viral infections such as infectious mononucleosis, and, in rare cases, acute HIV. The monkeypox virus has recently acquired attention and can cause symptoms that mimic an acute sore throat. It is currently unclear if Monkeypox will remain a relevant differential acute sore throat diagnosis or if it will vanish. Patients with a prolonged illness should undergo appropriate testing and this is especially important in adolescents and young adults.

In conclusion, it is important to not too narrowly focus on the outcome of a POCT to detect GAS in patients with a potentially complicated acute sore throat but to also be open to the possibility of other aetiologic agents.

Management of patients with moderate or high risk for rheumatic fever

Initially, patients require the same triage as described above ( and , and ). Patients who are potentially critically ill or with potentially complicated acute sore throat require proper diagnostics and management, as described above, to reduce the risk for acute suppurative complications and sepsis. In addition, the risk for subsequent rheumatic fever must be considered.

Patients with apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat but with moderate or high risk for rheumatic fever require management focussing on reducing this risk [Citation4]. Clinical judgement alone without the use of POCT to detect GAS is likely to leave a large proportion of patients ill from GAS without antibiotics even in settings with known moderate or high risk for rheumatic fever [Citation53]. Hence, if POCT is available we recommend testing all patients judged to be at moderate or high risk for rheumatic fever, irrespective of clinical scoring for GAS, and to prescribe antibiotics to all patients harbouring GAS [Citation4]. If POCT is unavailable we recommend that all patients with acute sore throat receive antibiotics in settings with a high risk for rheumatic fever [Citation4]. In settings with moderate risk and POCTs are unavailable, antibiotics should be prescribed to patients with a clinical score indicating probability for the presence of GAS such as Centor scores 2–4 or FeverPAIN scores 2–5 [Citation4].

Level of care

Patients presenting with potentially critical illness or with potentially complicated acute sore throat need diagnosis and management by a physician. With a structured triage scheme other categories of staff such as nurses or pharmacists may independently triage, and perhaps manage, patients with apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat in settings with low risk for rheumatic fever provided that they are given appropriate training [Citation4]. Previous studies suggest that this may significantly reduce antibiotic prescribing as well as visits to primary health-care clinics [Citation4,Citation57]. In some countries, nurses or pharmacists are already involved in management [Citation57]. Triage by nurses or pharmacists requires a rigorous safety net and and (supported by ) provide that. POCT to detect GAS performed by physicians may not be cost-effective [Citation60] but POCT performed by pharmacists might be [Citation61–63]. However, more evidence is needed before recommending pharmacy management as part of routine care and implementation should be carefully monitored.

Demand for testing or antibiotic prescribing

In high-income countries, the aim is that most, perhaps all, patients with apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat manage the self-limiting illness themselves without attending a health-care facility or pharmacy. However, patients with potentially complicated acute sore throat or with potentially critical illness must receive health care as soon as possible. In settings with a high prevalence of rheumatic heart disease, all patients with acute sore throat should seek health care for evaluation. Hence, we want to reduce the demand for testing or antibiotic prescribing in some patients while in other patients, these should increase. In high-income countries, the emphasis will be on reducing these demands while in low-income countries, the opposite is desired.

Current evidence points to a correlation between antibiotic prescribing and several factors: (A) The patient’s propensity to visit a physician when ill. This is partly a personality factor [Citation64] and partly influenced by government information campaigns competing with all other more or less accurate information available from friends, relatives, the press and social media on the Internet. (B) The degree of access to an appointment with a physician. The number of doctors is increasing both in absolute numbers and per capita in most high-income countries [Citation65]. However, this is a double-edged sword being both good and potentially bad. There is a correlation between attendance rates and antibiotic prescribing [Citation66] and lowering the threshold to see a physician is likely to increase antibiotic prescribing. (C) The threshold of the physician to prescribe antibiotics. This can be labelled as the doctor risk factor. The threshold for a physician to prescribe antibiotics varies due to different perceptions and personal preferences [Citation67,Citation68]. A multitude of interventions has been implemented to change prescribing of antibiotics. Some of the studies show a benefit in various infectious diseases [Citation69] but, as yet, there is no evidence that any of the attempts have shown long-term benefits in patients with acute sore throat [Citation69].

Testing for the presence of GAS or prescribing antibiotics for immediate use may imply to patients that they must see a physician, nurse or pharmacist next time they experience similar symptoms. Delayed prescriptions are redeemed in roughly a third of cases suggesting that delayed prescriptions may also cause patients to come back when experiencing similar symptoms, although to a lesser extent than prescribing for immediate use [Citation70]. Our proposal to test only a small proportion of patients with apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat, or, alternatively, to test none, will likely gradually educate the population towards self-management and in the long run, reduce demands in high-income countries. This can effectively be accomplished using our proposed triage ( and ).

Conclusions

Triage of patients with acute sore throat is part of current practice. The main contribution of this work to the literature is clarifying the type of triage required and defining exactly how this triage should be done to safely reduce antibiotic prescribing and to target the few patients who potentially benefit from antibiotic treatment.

The second contribution is stating that critically ill patients or patients with potentially complicated acute sore throat should be managed by a physician, while patients with apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat may be managed by other categories of staff like nurses or pharmacists. Allowing a pharmacist to make the initial triage as proposed here, and perhaps to also independently manage patients with apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat, might be a cost-effective alternative. This requires appropriate training and future research supports this approach without risks for the patient.

Our proposal is in agreement with previous publications in stating that patients with apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat and low clinical scoring (Centor score 0–2 or FeverPAIN 0–2) in a setting with low risk for rheumatic fever do not require testing for the presence of GAS nor a prescription of antibiotics. Patients with apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat and a higher clinical score can either be tested, and treated if positive, or a wait-and-see strategy could be used ().

Patient and public involvement

This report discusses an acute, and in most cases, self-limiting illness of short duration. It describes an expert consensus. Patients or the public were not involved in producing this consensus.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- André M, Vernby Å, Odenholt I, et al. Diagnosis-prescribing surveys in 2000, 2002 and 2005 in Swedish general practice: consultations, diagnosis, diagnostics and treatment choices. Scand J Infect Dis. 2008;40(8):648–654.

- Tyrstrup M, Beckman A, Molstad S, et al. Reduction in antibiotic prescribing for respiratory tract infections in Swedish primary care – a retrospective study of electronic patient records. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:709.

- Armstrong GL, Pinner RW. Outpatient visits for infectious diseases in the United States, 1980 through 1996. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(21):2531–2536.

- Gunnarsson R, Orda U, Elliott B, et al. What is the optimal strategy for managing primary care patients with an uncomplicated acute sore throat? Comparing the consequences of nine different strategies using a compilation of previous studies. BMJ Open. 2022;12(4):e059069.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). NICE Guideline [NG84] – sore throat (acute): antimicrobial prescribing. 2018. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng84

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). SIGN Guideline [117] – management of sore throat and indications for tonsillectomy. A national clinical guideline. 2010. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng84

- Shulman ST, Bisno AL, Clegg HW, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(10):1279–1282.

- Pelucchi C, Grigoryan L, Galeone C, ESCMID Sore Throat Guideline Group, et al. Guideline for the management of acute sore throat. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(Suppl 1):1–28.

- Hoare KJ, Ward E, Arroll B. International sore throat guidelines and international medical graduates: a mixed methods systematic review. J Prim Health Care. 2016;(1):20–29.

- Mustafa Z, Ghaffari M. Diagnostic methods, clinical guidelines, and antibiotic treatment for group A streptococcal pharyngitis: a narrative review. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:563627.

- Gunnarsson RK, Ebell M, Wächtler H, et al. The association between guidelines and medical practitioners’ perception of best management for patients attending with an apparently uncomplicated acute sore throat – a cross-sectional survey in five countries. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9):e037884.

- Gunnarsson RK, Holm SE, Söderström M. The prevalence of beta-haemolytic streptococci in throat specimens from healthy children and adults. Implications for the clinical value of throat cultures. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1997;15(3):149–155.

- Hedin K, Bieber L, Lindh M, et al. The aetiology of pharyngotonsillitis in adolescents and adults – Fusobacterium necrophorum is commonly found. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(3):263.e1–263.e7.

- Gunnarsson RK, Manchal N. Group C beta haemolytic Streptococci as a potential pathogen in patients presenting with an uncomplicated acute sore throat – a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2020;38(2):226–237.

- Lindbaek M, Hoiby EA, Lermark G, et al. Clinical symptoms and signs in sore throat patients with large colony variant β-haemolytic streptococci groups C or G versus group A. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(517):615–619.

- Tiemstra J, Miranda RL. Role of non-group A streptococci in acute pharyngitis. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(6):663–669.

- Little P, Moore M, Hobbs FDR, PRISM investigators, et al. PRImary care Streptococcal Management (PRISM) study: identifying clinical variables associated with Lancefield group A β-haemolytic streptococci and Lancefield non-Group A streptococcal throat infections from two cohorts of patients presenting with an acute sore throat. BMJ Open. 2013;3(10):e003943.

- Centor RM, Atkinson TP, Ratliff AE, et al. The clinical presentation of Fusobacterium-positive and streptococcal-positive pharyngitis in a university health clinic: a cross-sectional study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(4):241–247.

- Woldan-Gradalska P, Gradalski W, Gunnarsson R, et al. Group A beta haemolytic streptococci as a pathogen in patients presenting with an uncomplicated acute sore throat – a systematic literature review and meta-analysis considering climate zone and patient’s age. (Submitted manuscript). 2022.

- Klug TE, Rusan M, Fuursted K, et al. A systematic review of Fusobacterium necrophorum-positive acute tonsillitis: prevalence, methods of detection, patient characteristics, and the usefulness of the Centor score. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35(12):1903–1912.

- Malmberg S, Petrén S, Gunnarsson R, et al. Acute sore throat and Fusobacterium necrophorum in primary health care – a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(6):e042816.

- Gunnarsson RK, Lanke J. The predictive value of microbiologic diagnostic tests if asymptomatic carriers are present. Stat Med. 2002;21:1773–1785.

- Orda U, Gunnarsson RK, Orda S, et al. Etiologic predictive value of a rapid immunoassay for detection of group A streptococci antigen from throat swabs in patients presenting with a sore throat. North American Primary Care Research Group (NAPCRG) Annual Meeting; 2016 Nov 12–16; Colorado Springs, CO, USA. 2016. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YHMeQuKOYpw

- Spinks A, Glasziou PP, Del Mar CB. Antibiotics for treatment of sore throat in children and adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;12(12):CD000023.

- Nygren D, Wasserstrom L, Holm K, et al. Associations between findings of Fusobacterium necrophorum or β-hemolytic streptococci and complications in pharyngotonsillitis – a registry-based study in Southern Sweden. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76(3):e1428–e1435.

- Lemierre A. On certain septicaemias due to anaerobic organisms. Lancet. 1936;227(5874):701–703.

- Fine AM, Nizet V, Mandl KD. Large-scale validation of the Centor and McIsaac scores to predict group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(11):847–852.

- Centor RM, Witherspoon JM, Dalton HP, et al. The diagnosis of strep throat in adults in the emergency room. Med Decis Making. 1981;1(3):239–246.

- McIsaac WJ, White D, Tannenbaum D, et al. A clinical score to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use in patients with sore throat. CMAJ. 1998;158(1):75–83.

- McIsaac WJ, Goel V, To T, et al. The validity of a sore throat score in family practice. CMAJ. 2000;163(7):811–815.

- Little P, Hobbs FD, Moore M, PRISM investigators, et al. Clinical score and rapid antigen detection test to guide antibiotic use for sore throats: randomised controlled trial of PRISM (primary care streptococcal management). BMJ. 2013;347:f5806.

- Little P, Stuart B, Hobbs FD, DESCARTE investigators, et al. Predictors of suppurative complications for acute sore throat in primary care: prospective clinical cohort study. BMJ. 2013;347:f6867.

- Watkins DA, Johnson CO, Colquhoun SM, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of rheumatic heart disease, 1990-2015. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(8):713–722.

- Catanzaro FJ, Stetson CA, Morris AJ, et al. The role of the streptococcus in the pathogenesis of rheumatic fever. Am J med. 1954;17(6):749–756.

- Lennon D, Anderson P, Kerdemilidis M, et al. First presentation acute rheumatic fever is preventable in a community setting: a school-based intervention. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36(12):1113–1118.

- Robertson KA, Volmink JA, Mayosi BM. Antibiotics for the primary prevention of acute rheumatic fever: a meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2005;5(1):11.

- Beaton A, Okello E, Rwebembera J, et al. Secondary antibiotic prophylaxis for latent rheumatic heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(3):230–240.

- Kevat PM, Reeves BM, Ruben AR, et al. Adherence to secondary prophylaxis for acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease: a systematic review. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2017;13(2):155–166.

- Kevat PM, Gunnarsson R, Reeves BM, et al. Adherence rates and risk factors for suboptimal adherence to secondary prophylaxis for rheumatic fever. J Paediatr Child Health. 2020;57(3):419–424.

- Pichichero ME, Disney FA, Talpey WB, et al. Adverse and beneficial effects of immediate treatment of Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis with penicillin. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1987;6(7):635–643.

- Nelson JD. The effect of penicillin therapy on the symptoms and signs of streptococcal pharyngitis. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1984;3(1):10–13.

- Krober MS, Bass JW, Michels GN. Streptococcal pharyngitis. Placebo-controlled double-blind evaluation of clinical response to penicillin therapy. JAMA. 1985;253(9):1271–1274.

- Zwart S, Rovers MM, de Melker RA, et al. Penicillin for acute sore throat in children: randomised, double blind trial. BMJ. 2003;327(7427):1324.

- De Meyere M, Mervielde Y, Verschraegen G, et al. Effect of penicillin on the clinical course of streptococcal pharyngitis in general practice. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;43(6):581–585.

- Middleton DB, D'Amico F, Merenstein JH. Standardized symptomatic treatment versus penicillin as initial therapy for streptococcal pharyngitis. J Pediatr. 1988;113(6):1089–1094.

- Dagnelie CF, van der Graaf Y, De Melker RD. Do patients with sore throat benefit from penicillin? A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial with penicillin V in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1996;46(411):589–593.

- Petersen K, Phillips RS, Soukup J, et al. The effect of erythromycin on resolution of symptoms among adults with pharyngitis not caused by group A streptococcus. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(2):95–101.

- Zwart S, Sachs AP, Ruijs GJ, et al. Penicillin for acute sore throat: randomised double blind trial of seven days versus three days treatment or placebo in adults. BMJ. 2000;320(7228):150–154.

- Bank S, Christensen K, Kristensen LH, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of identifying Fusobacterium necrophorum in throat swabs followed by antibiotic treatment to reduce the incidence of Lemierre’s syndrome and peritonsillar abscesses. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32(1):71–78.

- Seeley A, Fanshawe T, Voysey M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of Fever-PAIN and Centor criteria for bacterial throat infection in adults with sore throat: a secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. BJGP Open. 2021;5(6):20211214.

- Willis BH, Coomar D, Baragilly M. Comparison of Centor and McIsaac scores in primary care: a meta-analysis over multiple thresholds. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(693):e245–e254.

- Cheung L, Pattni V, Peacock P, et al. Throat swabs have no influence on the management of patients with sore throats. J Laryngol Otol. 2017;131(11):977–981.

- Orda U, Biswadev M, Orda S, et al. Point of care testing for group A streptococci in patients presenting with pharyngitis will improve appropriate antibiotic prescription. Emerg Med Australas. 2016;28(2):199–204.

- Orda U, Gunnarsson RK, Orda S, et al. Etiologic predictive value of a rapid immunoassay for detection of group A streptococci antigen from throat swabs on patients presenting with a sore throat. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;45:32–35.

- Gunnarsson MS, Sundvall PD, Gunnarsson R. In primary health care, never prescribe antibiotics to patients suspected of having an uncomplicated sore throat caused by group A beta-haemolytic streptococci without first confirming the presence of this bacterium. Scand J Infect Dis. 2012;44(12):915–921.

- Kenealy T. Sore throat. BMJ Clin Evid. 2007;2007:1509.

- Mantzourani E, Wasag D, Cannings-John R, et al. Characteristics of the sore throat test and treat service in community pharmacies (STREP) in Wales: cross-sectional analysis of 11 304 consultations using anonymized electronic pharmacy records. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2022;78(1):84–92.

- Cohen JF, Pauchard JY, Hjelm N, et al. Efficacy and safety of rapid tests to guide antibiotic prescriptions for sore throat. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;6(6):CD012431.

- Gunnarsson RK, Orda U, Elliott B, et al. Improving antibiotics targeting using PCR point-of-care testing for group A streptococci in patients with uncomplicated acute sore throat. Aust J Gen Pract. 2021;50(1–2):745–753.

- Fraser H, Gallacher D, Achana F, et al. Rapid antigen detection and molecular tests for group A streptococcal infections for acute sore throat: systematic reviews and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2020;24(31):1–232.

- Health Technology Wales (HTW). Rapid antigen detection tests for group A streptococcal infections to treat people with a sore throat in the community pharmacy setting (Evidence Appraisal Report). 2020; p. 20. Available from: https://healthtechnology.wales/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/EAR020-Rapid-antigen-detecting-tests.pdf

- Health Technology Wales (HTW). Rapid antigen detection tests for group A streptococcal infections to treat people with a sore throat in the community pharmacy setting (HTW Guidance). 2020; p. 24. Available from: https://healthtechnology.wales/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/GUI020-Rapid-antigen-detecting-tests-English.pdf

- Klepser DG, Bisanz SE, Klepser ME. Cost-effectiveness of pharmacist-provided treatment of adult pharyngitis. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(4):e145–e154.

- Andre M, Hedin K, Hakansson A, et al. More physician consultations and antibiotic prescriptions in families with high concern about infectious illness-adequate response to infection-prone child or self-fulfilling prophecy? Fam Pract. 2007;24(4):302–307.

- OECD iLibrary. Health at a Glance: Europe 2020. State of health in the EU cycle. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2020.

- Tyrstrup M, van der Velden A, Engstrom S, et al. Antibiotic prescribing in relation to diagnoses and consultation rates in Belgium, The Netherlands and Sweden: use of European quality indicators. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2017;35(1):10–18.

- Pitts J, Vincent S. What influences doctors’ prescribing? Sore throats revisited. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1989;39(319):65–66.

- Howie JG. Some non-bacteriological determinants and implications of antibiotic use in upper respiratory tract illness. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1983;39:68–72.

- Coxeter P, Del Mar CB, McGregor L, et al. Interventions to facilitate shared decision making to address antibiotic use for acute respiratory infections in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(11):CD010907.

- Little P, Moore M, Kelly J, PIPS Investigators, et al. Delayed antibiotic prescribing strategies for respiratory tract infections in primary care: pragmatic, factorial, randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2014;348:g1606.