Abstract

Background

Effective direct-acting antiviral treatment against hepatitis C virus infection is available in many countries worldwide. Despite good treatment results, a proportion of patients does not respond to treatment. The aim of this study was to investigate the long-term prognosis and the outcome of salvage therapy, after an initial treatment failure, in a nation-wide real-life setting.

Method

Data from all adult patients registered in the national Swedish hepatitis C treatment register who did not achieve sustained virological response after initial antiviral treatment, was retrieved from 2014 through 2018.

Results

In total, 288 patients with primary treatment failure were included, of whom 236 underwent a second treatment course as salvage therapy after a median delay of 353 (IQR: 215–650) days. Fifteen patients received a third treatment course as second salvage treatment after a further median delay of 193 (IQR: 160–378) days. One-hundred-eleven out of 124 (90%) non-cirrhotic and 62/79 (78%) cirrhotic patients achieved sustained virological response following the first salvage treatment. Sustained virological response was achieved by 108/112 (96%) patients who received a triple antiviral regimen. In total 69 patients were lost to follow-up or died waiting for salvage treatment. Baseline cirrhosis was associated with poor long-term survival.

Conclusion

Our study indicates that salvage therapy was effective in most patients with primary treatment failure, in particular when a triple direct acting antiviral regimen was given. To avoid the risk of death or complications, patients with primary treatment failure should be offered salvage therapy with a triple regimen, as soon as possible.

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is associated with progressive liver damage, liver failure, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and death in severe cases [Citation1]. Effective treatment with direct acting antivirals (DAA) is currently available. A combination of two or more DAAs is necessary to avoid selection of antiviral resistance. The outcome of DAA treatment in patients with chronic HCV has proven excellent in large treatment trials as well as in real-life settings, in several countries worldwide [Citation2–7]. Sustained virological response (SVR), defined as non-detectable HCV-RNA in plasma 12 weeks after treatment discontinuation, can be achieved by 90–95% of patients using different regimens. Despite the excellent treatment results, a small proportion of patients do not respond to the given treatment. The long-term prognosis for this group of patients is poorly investigated.

In Sweden, the first DAA regimen was approved in 2014. Thereafter, all patients receiving DAA treatment against HCV infection have been registered in the national Swedish HCV treatment register for quality evaluation and surveillance purposes.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the long-term prognosis, as well as the outcome of salvage therapy, for patients with HCV infection who fail to achieve SVR following initial DAA treatment, in a real-life setting.

Method

Patients and study design

Data from all adult patients registered in the national HCV treatment register who did not achieve SVR after their first DAA treatment, defined by a positive test for HCV-RNA 12 weeks after cessation of treatment, during the period from 2014 through 2018, were retrieved. Patients from all 31 Swedish centres offering DAA treatment were included. Cirrhosis at baseline (i.e. before starting their initial DAA treatment) was defined as either a liver elastography examination indicating cirrhosis (>12.5 kPa), a liver biopsy showing fibrosis stage 4, according to Ludwig and Batts, or clinical signs of cirrhosis. Delay to salvage treatment was defined as the time between initial treatment failure and the start of salvage treatment. Loss to follow-up was defined as loss of contact with the patient for any other reason than death. Patients who received less than 8 weeks of initial treatment for any reason, were excluded. For a subgroup of patients, information regarding the time-point for development of liver decompensation (defined as either radiologic signs of ascites or oesophageal varices, or clinical signs of liver failure), diagnosis of hepatocellular cancer (HCC; verified either by computerised tomography or magnetic resonance imaging) and/or death (by any cause) was also retrieved from patient files when this information was available (follow-up cohort). The duration of the follow-up period was defined as the time between initial treatment failure and the end of follow-up (due to either end of study or lost to follow-up) or death. All patients were followed according to clinical routine at the discretion of their treating physician. Decisions regarding treatment regimen and duration of treatment were based on which compounds were available and/or recommended at the time of treatment initiation.

Ethics

The study was approved by the national ethical review board as well as the steering committee for the national HCV treatment register. Since this was a register-based study in which no individual data is presented, informed consent was not required.

Statistics

All statistical calculations were done using the JMP software package version 15.0.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Group comparisons were made by the Chi squared test for proportions and by the Wilcoxon test for continuous variables. Survival analysis was made using Kaplan-Meier plots, separated by a grouping variable. Group comparisons in the survial analyses were made by the Log rank test. P-values below 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Altogether, 14 003 patients underwent DAA treatment in Sweden during the study period. Of those 13 103 (93.6%) achieved a verified sustained virological response (SVR), defined by undetectable HCV-RNA by PCR 12 weeks after the end of initial treatment. The SVR rate ranged between 88.8% in 2014 and 94.0% in 2018. Reliable data regarding HCV-RNA status at 12 weeks follow-up were missing or pending in 581 cases. Data from the remaining 319 patients was extracted from the national HCV treatment register, based on failure to achieve SVR following DAA treatment. Thirty-one subjects were excluded because the duration of the initial treatment was less than 8 weeks. The remaining 288 patients with primary DAA failure constituted the study population. Clinical and demographic data is displayed in for the entire study population. One hundred patients had cirrhosis at baseline. Data regarding fibrosis stage was missing in 41 cases and the group of patients with a confirmed non-cirrhotic stage at baseline contained 147 subjects. Genotype 3 was significantly more common in patients with baseline cirrhosis than in patients without cirrhosis (61/98 (62%) vs. 46/145 (32%); p < 0.0001, Chi squared test). No other significant differences between patients with and without baseline cirrhosis were identified.

Table 1. Clinical and demographic data for all patients with primary DAA failure.

Salvage treatment

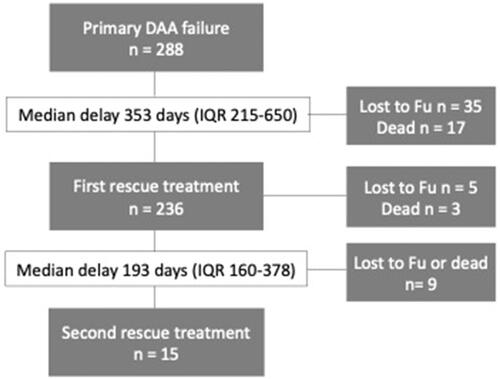

Two hundred-thirtysix patients received a first salvage treatment course and 15 patients a second when SVR was not achieved after the first one. The delay between treatments and drop-out rates during delay and treatment/follow-up periods are displayed in . The risk of dying while waiting for the first salvage treatment was higher in patients with baseline cirrhosis than in patients without baseline cirrhosis (12/100; 12% vs. 2/147; 1%, p = 0.001).

Figure 1. Flow chart displaying the delay as well as death and drop-out rates during treatment and delay periods before and between salvage therapies for 288 patients with primary DAA failure.

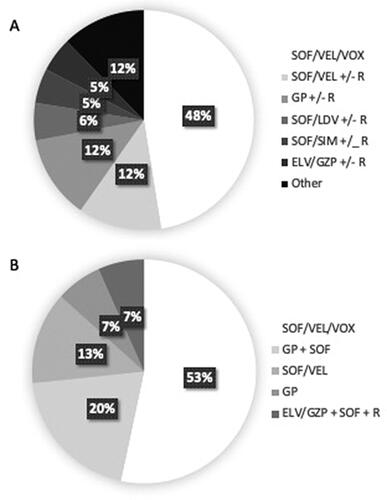

shows the type of treatment given as first and second salvage treatment, respectively. Patients were treated throughout the study period and the duration of delay as well as the type of treatment provided was dependent on which regimens were available and recommended at the time. Triple therapy was given to 48% and 86% of the cases at first and second salvage treatment, respectively.

Outcome of salvage treatment

show the treatment outcome of first and second salvage treatment for the entire study population as well as for subgroups of patients with and without baseline cirrhosis. The SVR rate after first salvage treatment was higher for patients without than for patients with baseline cirrhosis (111/124; 90% vs. 62/79; 78%, p = 0.003).

Table 2. Outcome of first and second salvage treatments according to presence of baseline cirrhosis.

When all 288 patients with primary DAA failure in the entire study population were included in an intention-to-treat analysis (ITT), the total SVR rate was 199/288 (69%) after first and 212/288 (74%) after both first and second salvage treatment.

The number of patients with baseline cirrhosis reaching SVR in ITT analysis was 62 (62%) after the first and 69/100 (69%) after both salvage treatments and 111 (76%) after the first and 116/147 (79%) after both salvage treatments for patients without baseline cirrhosis.

Patients receiving a regimen including three different DAAs (SOF/VEL/VOX in all cases) as salvage treatment had higher SVR rate than patients with any double regimen (108/112 (96%) vs. 91/121 (75%), p < 0.0001).

Survival analysis of the follow-up cohort

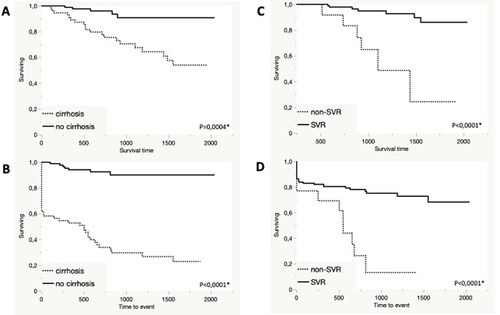

For 156 (54%) of 288 patients with DAA failure (the follow-up cohort), the time-point for death and/or diagnosis of liver-related complications (liver decompensation or HCC) could be determined. The median age was higher in the follow-up cohort (57 vs. 53 years, p = 0.001 Wilcoxon test) but there were no significant differences regarding sex, fibrosis stage or genotype distribution compared to the rest of the study cohort. Fifty-five patients (32%) in the follow-up cohort had cirrhosis at baseline, 85 (54%) had a verified non-cirrhotic stage while 16 (10%) had an unknown fibrosis stage at baseline. Twenty-eight patients (18%) died during the follow-up period. Median duration of the follow-up period was 586 (IQR 349–921) days for deceased patients and 945 (IQR 603–1464) days for survivors. The annual death rate (number of deaths/median follow-up time) in the cohort was 11.5% which is much higher compared to the crude death rate of Sweden of 9.3 per 100000 in 2022 [Citation8]. shows the overall survival for the 55 patients with and the 85 patients without cirrhosis at baseline.

Figure 3. (A) Overall survival (days) following primary DAA failure in 55 patients with and 85 patients without baseline cirrhosis. (B) Event-free survival (days) following primary DAA failure in 55 patients with and 85 patients without baseline cirrhosis. Events were defined as either death, liver decompensation or HCC. (C) Overall survival (days) following primary DAA failure in 117 patients with and 13 patients without SVR after first salvage treatment. (D) Event-free survival (days) following primary DAA failure in 117 patients with and 13 patients without SVR after first salvage treatment. Events were defined as death, liver decompensation or HCC. * Log rank test.

Twenty-two patients had decompensated liver disease at baseline while another 10 developed liver decompensation, within a median of 640 (IQR 260–812) days. Thirteen patients had HCC at baseline and another 20 patients developed HCC within a median time of 386 (IQR 127–610) days. displays event-free survival for the subgroups with and without baseline cirrhosis. In a subgroup of 130 patients, liver elasticity data were available at baseline, of whom 37 (28%) patients had a value > 20 kPa, indicating portal hypertension. The patients with portal hypertension had significantly poorer survival than patients without portal hypertension (13/37 (35%) vs. 8/93 (9%) died during the follow-up period, p = 0.002, Log rank test).

Altogether, 130/156 (83%) patients underwent a first salvage treatment with SVR in 117/130 (90%). shows the overall survival over time according to outcome of first salvage treatment (117 cases with SVR vs. 13 with non-SVR). The 26 patients who died or were lost to follow-up before or during first salvage treatment were excluded. shows event-free survival according to outcome of first salvage treatment.

Discussion

In the present study we describe the long-term prognosis and outcome of salvage treatment for Swedish HCV-infected patients who did not achieve SVR after initial DAA treatment, in a real-life setting. Most patients responded to salvage treatment, although a group of patients were lost to follow-up or died during periods of delay or waiting for access to another treatment. Patients with cirrhosis before initial unsuccessful DAA treatment had a rather poor long-term prognosis. Note that in this analysis, baseline cirrhosis was recorded before initial DAA treatment and the survival analysis started at the time of lack of SVR at 12 weeks. Thus, the rate of cirrhosis in the study group may be an underestimation since some patients may have deteriorated during treatment and/or follow-up.

The proportion of patients not achieving SVR following DAA treatment is commonly under 5% for all available antiviral treatment regimens. Retreatment with a triple regimen in patients who failed after the first treatment has been reported in clinical trials to give 96–98% SVR rate [Citation9]. These favourable results have also been confirmed in real-life studies [Citation10–13]. This is in line with our results that salvage therapy using a triple DAA regimen is effective, even with a certain delay, also in patients with cirrhosis. Such a regimen containing 3 DAAs with different mechanisms of action is currently recommended for retreatment in the EU and the US [Citation14,Citation15]. Patients with decompensated cirrhosis were not included in the pivotal trials. Triple regimens including protease inhibitors have been associated with deterioration of liver failure in patients with decompensated liver disease. Therefore, regimens including protease inhibitors are not recommended for decompensated patients, although successful treatment including protease inhibitors have been reported in small patient series [Citation16]. The alternative is a prolonged 24 weeks course of sofosbuvir and a NS5A inhibitor. In any case, treatment of hepatitis C in patients with decompensated liver disease requires close monitoring for adverse events and other disease manifestations during treatment. Our long-term results underscore the importance of initiating salvage therapy as soon as possible in the event of DAA failure, considering the chance of a fair outcome as well as the risk of further disease progression and development of complications if therapy is delayed or postponed. The effect of salvage treatment using a triple DAA regimen with ribavirin was confirmed (94% SVR; 47/50 patients) and was associated with a lower risk of HCC development in a report from Egypt [Citation17].

Treatment with a triple DAA regimen is effective also in the presence of mutations conferring resistance to both NS5A-inhibitors and protease inhibitors [Citation18]. Thus, we do not think that salvage therapy should be delayed by waiting for results of resistance testing. Resistance to protease inhibitor tends to disappear after a certain period of time, while NS5A- inhibitor resistance does not. Therefore, some guidelines recommend a wash-out period to wait for reversion to wild-type virus before starting retreatment [Citation19]. Our results suggest that retreatment should be initiated without delay, in order to improve survival, especially in patients with advanced liver disease. We believe that the risk of further development of complications outweigh the risk of reduced treatment effect due to protease inhibitor resistance.

The overall benefit of cure of hepatitis C has been confirmed in large cohort studies showing lower all-cause mortality and lower rates of HCC in patients achieving SVR compared to those who do not [Citation20,Citation21]. Furthermore, treatment with DAAs with subsequent SVR reduced the risk of liver decompensation and de novo HCC in a large prospective multicentre cohort excluding patients with decompensated liver disease and prior HCC [Citation22]. In patients with advanced liver disease, however, the effect of DAA-induced HCV clearance on disease progression might depend on disease severity. In a multicentre retrospective cohort study SVR was independently associated with improved clinical outcome in patients with compensated cirrhosis. In patients with decompensation prior to treatment, however, SVR had no impact on event-free survival [Citation23]. This is in line with our results and underscores the importance of prompt retreatment in order to avoid further deterioration of liver function and/or development of HCC, since those conditions may affect treatment outcome.

An important finding in our investigation is that baseline cirrhosis is an important determinant of poor long-term prognosis after treatment failure. This underscores the importance of an adequate estimation of the degree of liver fibrosis, prior to initiation of antiviral therapy. It also highlights the value of early treatment, before cirrhosis develops, if possible. Retreatment of cirrhotic patients after initial DAA treatment failure should be handled by experienced specialists and accurate investigation of liver damage by liver elastography measurement, or liver biopsy, should be performed if it was not done before the initial treatment. Our results indicate that when salvage therapy was given and tolerated, outcome was fair despite severe liver disease, since 79% of patients with baseline cirrhosis responded to salvage therapy. Injection drug use is common among HCV patients and a high proportion of the patients in our study likely have previous or ongoing experience of this. This and other comorbid conditions have probably affected survival, especially among patients who were lost to follow-up. This highlights the importance of providing proper care for drug dependency as well as other medical conditions in order to improve survival and adherence to therapy.

Current European guidelines recommend that treatment follow-up testing in order to confirm SVR, could be omitted in some cases considering the overall good treatment results [Citation14]. We do not recommend this strategy in patients with cirrhosis and/or adherence problems, since the rare cases of treatment failure would remain unrecognised with potentially detrimental consequences.

A fairly large proportion of patients in our study had cirrhosis and/or decompensation or HCC at baseline which in previous studies has been associated with treatment failure [Citation24]. In our study, as expected, DAA treatment failure was associated with advanced liver disease which has probably contributed to the unsuccessful treatment in some cases. A proper investigation including staging of liver disease and diagnostic procedures, to rule out or confirm potential liver tumours is warranted following treatment failure. Interventions against HCC and optimisation of liver function may impact on quality of life as well as outcome of further treatment efforts. Salvage treatment is often more complicated for patients with decompensated disease or HCC but may still be effective. In the present study, 13 out of 22 (59%) of the patients with decompensation and 6 out of 13 (46%) of those with HCC achieved SVR after salvage therapy. Thus, salvage treatment should be initiated as soon as possible, to avoid further potential complications. A number of patients in our study were lost to follow-up or died waiting for salvage therapy which is a real risk in this group of vulnerable individuals. Thus, close monitoring and management without unnecessary delay may be essential.

In our study, a triple DAA regimen (mainly sofosbuvir, velpatasvir and voxilaprevir) was by far the regimen with the best outcome. However, since this was not a randomised trial, indications for treatment were not uniform, some currently available options may have been inaccessible, and outcome could not be compared across groups. Although we beleive this is correct and in line with previous reports, our results should be interpreted with some caution. In the current Swedish guidelines for treatment of hepatitis C, the triple regimen is reserved as a second line treatment, mainly for patients with treatment failure following primary DAA treatment [Citation19].

The current study included patients from all Swedish HCV treatment centres with a large sample size with a unique retrospective cohort design and an extended follow-up period. There are, however, several limitations including a heterogenous patient group where indications for treatment and available treatment options varied over the study period. Moreover, reinfection could not be ruled out as cause of treatment failure, nor distinguished from relapse. Data on adherence to treatment, injection drug use, duration of treatment for patients who were lost to follow-up during salvage treatment, comorbidity, cause of death and antiviral resistance data were not available. Thus, the impact of these factors on treatment outcome could not be investigated. The data in the national treatment register relies on local data input at each centre and the quality or validity of the data could not be properly controlled. Additionally, a number of patients were excluded because of missing data which is a limitation.

In conclusion, our study shows excellent outcome of salvage therapy for patients with primary DAA failure when implemented and tolerated, even despite a certain delay, especially when a triple DAA regimen was used. However, a certain number of patients were lost to follow-up or died waiting for salvage therapy and the long-term prognosis for patients with baseline cirrhosis was poor. We suggest close monitoring of patients with primary DAA failure and initiation of salvage therapy using a triple DAA regimen, as soon as possible.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Susanne Cederberg, Frida Samuelsson and Camilla Håkangård, as well as managers and staff at the infectious disease clinics in Sundsvall, Karlskrona and Halmstad for help in retrieving data.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Lingala S, Ghany MG. Natural history of hepatitis C. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2015;44(4):717–734. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2015.07.003.

- Zeuzem S, Foster GR, Wang S, et al. Glecaprevir-Pibrentasvir for 8 or 12 weeks in HCV genotype 1 or 3 infection. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(4):354–369. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1702417.

- Zeuzem S, Ghalib R, Reddy KR, et al. Grazoprevir-Elbasvir combination therapy for treatment-naive cirrhotic and noncirrhotic patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1, 4, or 6 infection: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(1):1–13. doi: 10.7326/M15-0785.

- Feld JJ, Jacobson IM, Hezode C, et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV genotype 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(27):2599–2607. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1512610.

- Lampertico P, Carrion JA, Curry M, et al. Real-world effectiveness and safety of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir for the treatment of patients with chronic HCV infection: a meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2020;72(6):1112–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.01.025.

- Berg T, Naumann U, Stoehr A, et al. Real-world effectiveness and safety of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C infection: data from the german hepatitis C-Registry. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49(8):1052–1059. doi: 10.1111/apt.15222.

- Mangia A, Milligan S, Khalili M, et al. Global real-world evidence of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir as simple, effective HCV treatment: analysis of 5552 patients from 12 cohorts. Liver Int. 2020;40(8):1841–1852. doi: 10.1111/liv.14537.

- Sweden Statistics. Mortality rate, per 1,000 of the mean population by age, sex and year. 2022. Available from: https://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/ssd/START__BE__BE0101__BE0101I/Dodstal/table/tableViewLayout1/.

- Bourliere M, Gordon SC, Flamm SL, et al. Sofosbuvir, velpatasvir, and voxilaprevir for previously treated HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(22):2134–2146. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1613512.

- Xie J, Xu B, Wei L, et al. Effectiveness and safety of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir as a hepatitis C virus infection salvage therapy in the real world: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis Ther. 2022;11(4):1661–1682. doi: 10.1007/s40121-022-00666-0.

- Degasperi E, Spinetti A, Lombardi A, et al. Real-life effectiveness and safety of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir in hepatitis C patients with previous DAA failure. J Hepatol. 2019;71(6):1106–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.07.020.

- Llaneras J, Riveiro-Barciela M, Lens S, et al. Effectiveness and safety of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir in patients with chronic hepatitis C previously treated with DAAs. J Hepatol. 2019;71(4):666–672. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.06.002.

- Wilson E, Covert E, Hoffmann J, et al. A pilot study of safety and efficacy of HCV retreatment with sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir in patients with or without HIV (RESOLVE STUDY). J Hepatol. 2019;71(3):498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.05.021.

- European association for the study of the liver. EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C: final update of the series. J Hepatol. 2020;73(5):1170–1218.

- Ghany MG, Morgan TR; Panel Aasld-Idsa Hepatitis C Guidance. Hepatitis C guidance 2019 update: american association for the study of liver diseases-infectious diseases society of america recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2020;71(2):686–721. doi: 10.1002/hep.31060.

- Patel S, Martin MT, Flamm SL. Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir for hepatitis C virus retreatment in decompensated cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2021;41(12):3024–3027. doi: 10.1111/liv.15075.

- Hanafy AS, Soliman S, Abd-Elsalam S. Rescue therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus infection after repeated treatment failures: impact on disease progression and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2019;49(4):377–384. doi: 10.1111/hepr.13303.

- Sarrazin C, Cooper CL, Manns MP, et al. No impact of resistance-associated substitutions on the efficacy of sofosbuvir, velpatasvir, and voxilaprevir for 12 weeks in HCV DAA-experienced patients. J Hepatol. 2018;69(6):1221–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.07.023.

- Lagging M, Wejstal R, Duberg AS, et al. Treatment of hepatitis C virus infection for adults and children: updated swedish consensus guidelines 2017. Infect Dis (Lond). 2018;50(8):569–583. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2018.1445281.

- Backus LI, Belperio PS, Shahoumian TA, et al. Impact of sustained virologic response with Direct-Acting antiviral treatment on mortality in patients with advanced liver disease. Hepatology. 2019;69(2):487–497. doi: 10.1002/hep.29408.

- Carrat F, Fontaine H, Dorival C, et al. Clinical outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis C after direct-acting antiviral treatment: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2019;393(10179):1453–1464. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32111-1.

- Mendizabal M, Pinero F, Ridruejo E, et al. Disease progression in patients With hepatitis C virus infection treated With Direct-Acting antiviral agents. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(11):2554–2563 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.02.044.

- Krassenburg LAP, Maan R, Ramji A, et al. Clinical outcomes following DAA therapy in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis depend on disease severity. J Hepatol. 2021;74(5):1053–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.11.021.

- Kushner T, Dieterich D, Saberi B. Direct-acting antiviral treatment for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2018;34(3):132–139. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000431.