Abstract

Background

Scrub typhus is a vector-borne infection caused by the obligate intracellular organism Orientia tsutsugamushi. In some cases, scrub typhus can result in severe complications, multiorgan failure and death.

Objective

To study the clinical and laboratory profiles of patients who succumbed to scrub typhus.

Methods

A prospective cohort study was conducted from August 2019 through April 2023 on scrub typhus patients admitted to our hospital. Clinical and laboratory parameters of all the patients were recorded, and blood samples were drawn. To confirm scrub typhus, a nested polymerase chain reaction (nPCR) was performed in collected samples. Viable amplicons were sequenced, and phylogenetic analyses were performed to identify infecting genotypes.

Results

A total of 261 patients were enrolled. Of these, nine (3.45%) patients succumbed at a median (Interquartile Range) duration of 5 (1.5, 10.5) days after admission. Sepsis with septic shock (9, 100%) and acute kidney injury (AKI) (6, 66%) were noted among the succumbed patients. All the succumbed patients (100%) required intensive care admission, inotropic and ventilatory support. While 5 (55%) patients required dialysis, two (22%) required blood transfusion. Three (33%) patient samples were co-positive for Leptospira IgM, and four (44%) patients had superinfection with Candida tropicalis, multi-drug-resistant (MDR) E. Coli sepsis, pan drug-resistant (PDR) Acinetobacter Baumanii, and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Phylogenetic analysis revealed Orientia tsutsugamushi Japanese Gilliam-variant (JG-v) like (50%), Karp-like (37.5%), and Japanese Gilliam (JG) like (12.5%) strains among succumbed patients.

Conclusion

Delay in scrub typhus diagnosis can result in severe complications, septic shock, and multisystem organ failure, culminating in death.

Introduction

Scrub typhus is transmitted by the bite of larval stage Leptotrombidium chigger mite and is caused by the obligate intracellular organism ‘Orientia tsutsugamushi’ [Citation1,Citation2]. The clinical manifestations of scrub typhus infection are non-specific and resemble that of other tropical infections like dengue, malaria, chikungunya and leptospirosis [Citation3,Citation4]. The early manifestations include an eschar at the site of mite bite, fever, headache, myalgia, generalised lymphadenopathy, cough, gastrointestinal symptoms, and rash. Progression of severe scrub typhus may manifest as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), meningoencephalitis, gastrointestinal bleeding, acute renal failure, hypotensive shock, and coagulopathy [Citation5]. Patients with these complications may have poor prognosis. The primary site of multiplication of Orientia tsutsugamushi is endothelial cells. Focal or disseminated vasculitis is the pathologic characteristic of scrub typhus, which can cause single or multi-organ dysfunction [Citation6]. Here, we present the clinical and laboratory profile of Orientia tsutsugamushi nPCR and sequencing confirmed patients who succumbed to scrub typhus.

Patients and methods

A prospective cohort study was conducted on scrub typhus patients admitted to a tertiary care teaching hospital in Karnataka, India from August 2019 through April 2023. Adult patients of either gender presenting to hospital with fever more than or equal to 38 °C for 3–14 days with a diagnosis of scrub typhus by either IgM ELISA or IgM RDT or eschar were enrolled. Patients not willing to provide informed consent or patients with immunosuppressive conditions or patients with a laboratory diagnosis of other infections or with a clinical diagnosis of other infections as deemed by the treating physician were excluded.

Clinical and laboratory profiles of all patients were recorded in a proforma and stored electronically in Microsoft Excel. The intravenous treatment for scrub typhus trial (INTREST) severity criteria, which considers cardiovascular, respiratory, central nervous system, renal, hepatic, and haematological parameters was used to define severity and organ involvement among the cohort [Citation7]. Simultaneously, a clinical risk scoring algorithm (CRSA) that forecasts severe scrub typhus was also used to determine if the scoring algorithm can predict mortality among the cohort [Citation8].

During the four-year study period, nine scrub typhus patients succumbed. The clinical and laboratory profile of succumbed and recovered patients was analysed using IBM SPSS statistics software Version 20.0 for Windows (SPSS IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The categorical variables were described in terms of their counts and percentages, while continuous variables that followed a normal distribution were presented as mean and standard deviation. For those not following a normal distribution, median and interquartile range (IQR) were used. To compare the mean or median of continuous variables between the groups who recovered, and the succumbed, independent samples t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test was employed. To compare categorical variables between the groups who recovered, and the succumbed, Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test were performed. All tests of significance were two-tailed, and a p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Laboratory procedures

A 4 ml of blood was drawn into an EDTA tube, and 2 ml of blood was drawn into a plain tube. The serum was separated from the plain tube to perform IgM ELISA with Scrub typhus DirectTM IgM ELISA kit (InBios International, Inc., Seattle, WA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The scrub typhus IgM OD value cut-off previously determined in the same geographical location was adopted for this study [Citation9]. The blood collected in the EDTA tube was separated into plasma and buffy coat. Approximately, 300 µl of the buffy coat was utilised to extract DNA using the salting out method. The extracted DNA was subjected to a nested polymerase chain reaction (nPCR) targeting the 483 bp segment of Orientia tsutsugamushi 56-kDa type-specific-antigen (TSA) gene [Citation10]. The amplicons were resolved on a 1.5% agarose gel and were visualised in a UV Gel documentation system. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, successful amplicons were gel purified using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany). The purified amplicons were sanger sequenced bidirectionally using both forward 5′-GATCAAGCTTCCTCAGCCTACTATAATGCC-3′ and reverse primers 5′-CTAGGGATCCCGACAGATGCACTATTAGGC-3′. The BigDye Terminator Cycle sequencing ready reaction kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) was used for sequencing the amplicons in an ABI 3730 DNA Analyser (Applied Biosystems). The sequences obtained were deposited to NCBI GenBank (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) with accession numbers “OP617281-OP617329, OQ320014 – OQ320038, OQ428197, and OR526472 - OR526477””. Some of the sequences (OP617281-OP617329) previously published [Citation11] by our research group during the same study period, were utilised for the current study to provide a perspective of infecting genotypes among the survived and succumbed patients. A total of 30 reference sequences representative of Karp, Saitama, Kuroki, TA763, Gilliam, Kawasaki, JG, JG-v, and Kato genotypes of Orientia tsutsugamushi were retrieved from NCBI GenBank. The reference sequences, along with the sequences of succumbed patients obtained in the study, were aligned using Clustal W (http://www.clustal.org/). Phylogenetic analyses and evolutionary tree were performed using Mega X [Citation12].

Ethics statement

The study was reviewed by Kasturba Medical College and Kasturba Hospital Institutional Ethics Committee and received approval with number IEC:412/2019. Written informed consent was obtained from all the patients or their family members.

Results

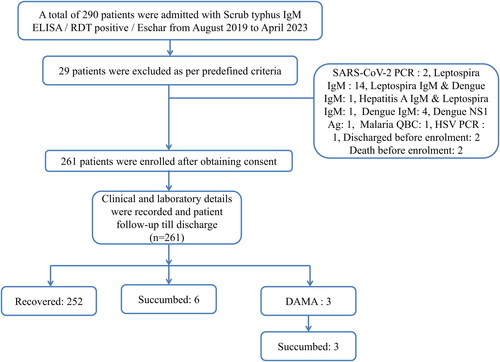

From August 2019 to April 2023, 261 patients of scrub typhus diagnosed by scrub typhus IgM ELISA were enrolled in the study (). The mean age of the cohort was 49.5 ± 14.8 years with male (57.9%) preponderance. During the four-year study period, 252 (96.55%) patients recovered and nine (3.45%) patients succumbed. Among the 252 recovered patients, nPCR was positive in 103 (40.8%) patient samples, and among the succumbed nPCR was positive in all the nine (100%) patient samples.

The mean age of the succumbed patients was 58 ± 14.99 years, and males were 5 (55%). Clinical manifestations at the time of presentation were fever (77%), breathlessness (44%), abdominal pain (44%), myalgia (33%), jaundice (33%) and cough (22%). Altered sensorium and pathognomonic eschar were seen in 2 (22%) patients each (). Five (55%) succumbed patients had comorbidities at the time of admission. The median duration of illness at the time of presentation among succumbed patients was 4 (4, 6.5) days and recovered patients was 7 (5, 10) days (). The succumbed group of patients had significant cardiovascular, respiratory, renal and hepatic involvement as compared to the recovered group of patients (). At the time of presentation, leukocytosis (total white blood cell count >10,000 cells/µl) was seen in 6 (66%) patients. None of the patients had leukopenia. While thrombocytopenia (platelet count <50,000 cells/µl) was seen in five (55%) patients. One (11%) patient had severe thrombocytopenia with a platelet count of 4,000 cells/µl at admission. All the succumbed patients had total protein <6.0 g/dL and serum albumin </=3.0 g/dL at admission. Elevated transaminases were also noted in all the succumbed patients (). While haemoglobin, platelet count, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, and serum creatinine were significantly elevated, total protein and serum albumin were significantly low among the succumbed group of patients (). C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin (PCT) were elevated among all the patients tested at the time of admission ().

Table 1. Clinical manifestations and organ involvement of the scrub typhus cohort (N = 261).

All patients received either doxycycline, azithromycin, or a combination of both. Two (22%) patients were administered with intravenous doxycycline and one patient received oral doxycycline. Intravenous azithromycin was administered to three (33%) patients, and combination of intravenous azithromycin and intravenous doxycycline were administered to two (22%) patients. One patient received a combination of oral azithromycin and intravenous doxycycline. Six out of nine patients were treated with steroids. Methylprednisolone was administered to two patients, hydrocortisone to two patients, and a combination of both sequentially to the remaining two patients. All the succumbed patients (100%) required intensive care admission, inotropic and ventilatory support. While five (55%) patients needed dialysis, two (22%) patients required blood transfusion.

Three (33%) patient samples were co-positive for Leptospira IgM at the time of admission. Four (44%) patients had superinfection. Superinfection was defined as patients acquiring a new secondary infection after 48 hours of hospital admission. Super infections among the patients were Candida tropicalis, multi-drug resistant (MDR) E. Coli sepsis, pandrug-resistant (PDR) Acinetobacter baumanii, and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Sepsis with septic shock (9, 100%) and AKI (6, 66%) were noted among the succumbed patients. Despite receiving good supportive care, death occurred at a median duration of 5 (1.5, 10.5) days after admission.

When the scoring algorithm devised by Sriwongpan et al. was applied to our cohort, the non-severe group (score ≤5) consisted of 90 (34.5%) patients, the severe group (score 6–9) consisted of 95 (36.4%) patients and the fatal severity group (score ≥10) consisted of 76 (29.1%) patients. Though all the fatal patients (9, 100%) were correctly classified to the fatal severity group, the scoring algorithm misclassified 67 (88.1%) survivors to the fatal severity group (score ≥10).

The data was stratified based on the CRSA severity score of ≥7 (severe group) determined among the Indian population. A total of 137 (52.5%) patients had a severity score ≥7 and the remaining 124 (47.5%) patients had a score of < 7. All the succumbed patients were correctly classified to the severity score ≥7.

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

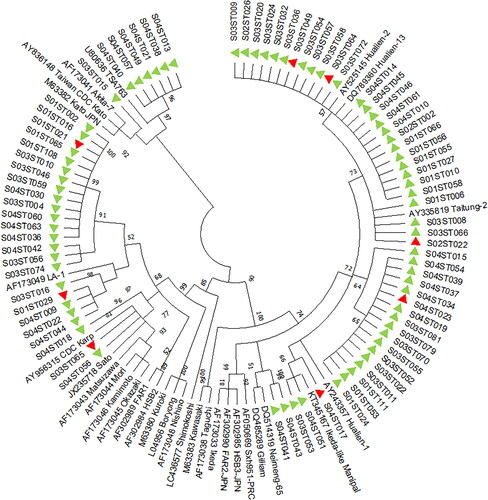

Out of the 112 nPCR positives, 81 bright amplicons were purified, sequenced and were subjected to phylogenetic analysis. The phylogenetic analysis of the 81 sequences, along with 30 reference sequences of the Orientia tsutsugamushi 56 kDa TSA gene, showed that most of the sequences (28, 34.56%) were close to the Japanese Gilliam-variant (JG-v), followed by Karp-like (24, 29.62%), Japanese Gilliam-like (JG) (20, 24.7%), TA763-like (6, 7.4%), Gilliam-like (2, 2.46%) and Kato-like (1, 1.23%) strains.

Among the nine patients who succumbed, only eight patient samples produced bright amplicons of the Orientia tsutsugamushi 56 kDa TSA gene at ∼483bp, which were suitable for sequencing. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that four of the sequences were JG-v-like strains, three sequences were Karp-like strains, and the other sequence was a JG-like strain ().

Discussion

Scrub typhus affects approximately one million individuals annually and over a billion population is at risk of this disease residing in the Tsutsugamushi triangle [Citation13,Citation14]. However, in recent times, data pertaining to the emergence of Orientia outside the Tsutsugamushi triangle in the regions of Africa, Europe, the Middle East and South America have been documented [Citation15]. In our study, the patients were admitted to the hospital with complaints of fever, chills, headache, myalgia, vomiting, abdominal pain, and cough. A subset of patients had breathlessness, altered sensorium and seizures at admission (). During the four-year study period, nine (3.45%) patients succumbed to scrub typhus. Patients suffering from scrub typhus and exhibiting mild-to-moderate symptoms, such as fever without any organ dysfunction, may only need antipyretics along with azithromycin or doxycycline. However, the patients presenting with organ dysfunction would require supportive therapy based on the organ involved and extent of organ dysfunction. All nine (100%) patients in our study required intensive care admission, received inotropic and ventilatory support. In addition to supportive therapy among severe patients, early initiation of appropriate antibiotics plays an important role in treatment outcomes. A recent multi-centre randomised controlled trial on severe scrub typhus patients (INTREST Trial) demonstrated that the combination of azithromycin and doxycycline was superior to either of the antibiotics alone [Citation7]. Notably, 6 of the nine patients received either doxycycline or azithromycin in our study (). Perhaps the combination of azithromycin and doxycycline could have better outcomes.

Table 2. Clinical characteristics and complications in patients succumbed to scrub typhus (N = 9).

In the current study, six patients were treated with either methylprednisolone or hydrocortisone, or a combination of both. Limited data is available regarding the use of steroids in patients with scrub typhus. However, a recent case report demonstrated the success of using methylprednisolone and therapeutic plasma exchange in a scrub typhus patient with ARDS [Citation16]. The coadministration of steroid therapy with antibiotics during early infection has been found to be useful in reducing neurological symptoms in both scrub typhus and spotted fever rickettsioses [Citation17]. Further randomised control trials can be carried out to determine the efficacy of steroids among severe scrub typhus patients.

The majority of the succumbed patients in our study did not have any comorbidities. However, they were older. The mean age of these patients was 58 ± 14.99 years. Sepsis with septic shock was the common finding noted in all the succumbed patients. Septic shock is a severe form of sepsis that causes hypotension despite sufficient fluid resuscitation and has a high mortality [Citation18]. CRP and PCT are indirect markers of sepsis. Though CRP levels may be elevated due to non-infectious conditions, some studies suggest that elevated levels of plasma CRP being associated with an increased risk of organ failure and death [Citation19]. Similarly, in our study, six (66%) patients who were tested for CRP had their CRP values elevated (>5 mg/L) (.). In scrub typhus patients requiring intensive care admission, elevated PCT is associated with mortality [Citation20]. Similarly, in our study, six (66%) patients who were tested for PCT had their PCT values elevated (>0.5 mcg/L) ().

Table 3. Laboratory findings of the patients succumbed due to scrub typhus (N = 9).

Table 4. Laboratory parameters of the scrub typhus cohort (N = 261).

AKI in our study was present in 6 (66%) patients. AKI is also one of the predictors of mortality in scrub typhus patients [Citation5]. AKI in scrub typhus usually resolves with antibiotics and supportive therapy [Citation21]. AKI in scrub typhus could be due to multiple factors such as shock, hypovolemia, vasculitis, rhabdomyolysis, or acute interstitial nephritis. Elevated creatine phosphokinase (CPK) levels in AKI patients might suggest the role of rhabdomyolysis [Citation21]. However, CPK was not performed in all the succumbed patients in our study. Fluid intake and output should be monitored thoroughly in critically ill patients with complications such as AKI, ARDS, acute lung injury, and sepsis, as studies have demonstrated a correlation between fluid overload and mortality in such patients [Citation22,Citation23].

Liver dysfunction in scrub typhus patients has been previously reported in various studies. Hepatitis (Bilirubin ≥2 mg/dl) was reported in 63.7% of patients with multi-organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) [Citation5]. Similarly, in our study, hepatitis was noted in 8 (88%) patients who succumbed to scrub typhus. Mortality due to liver failure in scrub typhus is rare. However, there were a couple of case reports of scrub typhus patients who had succumbed due to acute liver failure [Citation24,Citation25]. Histopathological findings of autopsy tissue samples were suggestive of submassive hepatocellular necrosis, inflammatory cell infiltration in Glisson’s capsules, and sporadic fibrin thrombi in the hepatic sinusoids [Citation24].

Among scrub typhus patients with MODS, respiratory involvement was reported in 76.9% of patients, of which 68.9% required ventilatory support [Citation5]. In our study, all the 9 (100%) patients required ventilatory support. Though vasculitis is the common pathological finding in scrub typhus, an alternative mechanism, an immunological response of the lung to previous infection might be involved in the development of ARDS and other lung manifestations in scrub typhus patients [Citation26]. This has been evidenced in an open lung biopsy of a patient deteriorating with ARDS [Citation26]. Pathological findings were suggestive of diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) in the organising stage in the absence of vasculitis. Immunofluorescent antibody staining and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) did not demonstrate the presence of Orientia tsutsugamushi in the lung biopsy sample [Citation26].

In our study, 4 (44%) succumbed patients had superinfections with Candida tropicalis, MDR E. Coli, PDR Acinetobacter Baumanii and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Superinfections with Acinetobacter Baumanii and Klebsiella pneumoniae in scrub typhus patients have been reported previously [Citation27,Citation28]. Superinfections are healthcare-associated infections (HAIs). These HAIs are preventable conditions that may lead to prolonged hospital stay, additional diagnostic and therapeutic interventions and undesired outcomes.

Varghese et al. have devised independent predictors of mortality in scrub typhus, viz. shock requiring vasoactive agents, central nervous system dysfunction and renal failure [Citation5]. In cases of complicated scrub typhus with central nervous system (CNS) involvement and MODS, mortality could be up to 13.6% and 24.1% respectively [Citation29]. The overall case-fatality ratio of scrub typhus in India is 6.3% [Citation30]. Mortality of scrub typhus was 8.13% at our tertiary care centre between 2010 and 2012 [Citation31]. In the current study, conducted during 2019 through 2023, an improvement in mortality trend (3.45%) was observed. The improvement in mortality trend could be due to early recognition of scrub typhus cases and timely initiation of appropriate antibiotics.

Though all the succumbed patients were correctly classified into fatal scrub typhus group according to CRSA, the algorithm has misclassified 67 (88.1%) survivors to the fatal severity group (score ≥10). Gulati et al. have validated the CRSA in Indian population [Citation32]. A CRSA severity score of ≥7 had an optimal combination of sensitivity (75.9%) and specificity (77.5%) in predicting severity [Citation32]. In our study, 137 (52.5%) patients had a severity score ≥7. All the succumbed patients were correctly classified to the severity score ≥7. Further, scoring algorithm that takes into account additional clinical and laboratory parameters can be devised. These algorithms can aid clinicians in identifying severe patients and initiate aggressive patient management, thereby reducing morbidity and mortality associated with scrub typhus.

The median duration of symptoms at admission among the succumbed was 4 (4, 6.50) days and death occurred at a median duration of 5 (1.5, 10.5) days after admission, indicating that patients had a fulminant course of infection. This understates the importance of high index of suspicion, early diagnosis, and the need for robust rapid diagnostic tests. Scrub typhus diagnosis is often challenging without an eschar or a confirmatory test such as immunofluorescence assay (IFA) or PCR. The presence of eschar in scrub typhus patients varies vastly (9.5% − 92%) [Citation33,Citation34]. The overall presence of eschar among our cohort was 13.4%. Scrub typhus IgM is known to persist for a longer duration above the diagnostic cut-off up to 12 months [Citation35]. This further makes the diagnosis of scrub typhus by IgM ELISA with a single serum sample challenging [Citation35]. New assays targeting novel Orientia tsutsugamushi antigens can be explored to aid in the rapid detection of scrub typhus.

In our study, serological co-positives of scrub typhus and Leptospira IgM were seen in 3 (33%) patients. However, a confirmation of Leptospira with microscopic agglutination test (MAT) or Urine Dark Ground Microscopy (DGM) or molecular assays could not be performed due to limited resources. Scrub typhus and leptospirosis are major acute febrile illnesses endemic in the study region. They present with similar clinical manifestations, often challenging diagnosis [Citation3]. Serological co-positives of scrub typhus and leptospirosis have been reported in earlier studies [Citation3,Citation36]. A confirmatory test is essential to rule out serological co-positives [Citation3].

Scrub typhus should be considered as a differential diagnosis of acute febrile illnesses in the country, particularly during outbreaks. Scrub typhus had a history of wreaking havoc during seasonal outbreaks in Uttar Pradesh, India [Citation37]. The major circulating strain of Orientia tsutsugamushi in the northern part of the country is Gilliam [Citation37], as opposed to JG-v, noted in our geographical region. The Karp genotype of Orientia tsutsugamushi is known to cause mortality, as demonstrated in animal models [Citation38]. However, in our study, JG-v was more prevalent among succumbed patients, followed by Karp (). Further studies focusing on both host and pathogen factors can aid in understanding factors associated with the severity of illness, organ involvement and poor outcomes among scrub typhus patients.

In conclusion, delay in early diagnosis of scrub typhus can result in severe complications such as ARDS, septic shock, and multisystem organ failure, culminating in death. Early initiation of intravenous azithromycin and doxycycline combination could improve treatment outcomes among patients with severe scrub typhus infection. Care should be taken to avert superinfections among patients admitted to the intensive care unit, as it may lead to adverse outcomes.

Acknowledgements

None.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability

All the sequences obtained were deposited to NCBI GenBank with accession numbers OP617281-OP617329, OQ320014 – OQ320038, OQ428197, and OR526472 - OR526477.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Chrispal A, Boorugu H, Gopinath KG, et al. Scrub typhus: an unrecognized threat in South India – clinical profile and predictors of mortality. Trop Doct. 2010;40(3):129–133. doi: 10.1258/td.2010.090452.

- Rahi M, Gupte MD, Bhargava A, et al. DHR-ICMR guidelines for diagnosis & management of rickettsial diseases in India. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141(4):417–422. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.159279.

- Gupta N, Chaudhry R, Mirdha B, et al. Scrub typhus and leptospirosis: the fallacy of diagnosing with IgM enzyme linked immunosorbant assay. J Microb Biochem Technol. 2016;08(02):71–75. doi: 10.4172/1948-5948.1000265.

- Chaudhry R, Thakur CK, Gupta N, et al. Mortality due to scrub typhus - report of five cases. Indian J Med Res. 2019;149(6):790–794. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1314_18.

- Varghese GM, Trowbridge P, Janardhanan J, et al. Clinical profile and improving mortality trend of scrub typhus in South India. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;23:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.02.009.

- Li W, Huang L, Zhang W. Scrub typhus with multi-organ dysfunction syndrome and immune thrombocytopenia: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2019;13(1):358. doi: 10.1186/s13256-019-2299-x.

- Varghese GM, Dayanand D, Gunasekaran K, et al. Intravenous doxycycline, azithromycin, or both for severe scrub typhus. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(23):2204–2205. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2208449.

- Sriwongpan P, Krittigamas P, Tantipong H, et al. Clinical risk-scoring algorithm to forecast scrub typhus severity. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2013;7:11–17. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S55305.

- Koraluru M, Bairy I, Varma M, et al. Diagnostic validation of selected serological tests for detecting scrub typhus. Microbiol Immunol. 2015;59(7):371–374. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12268.

- Furuya Y, Yoshida Y, Katayama T, et al. Serotype-specific amplification of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi DNA by nested polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31(6):1637–1640. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.6.1637-1640.1993.

- Chunduru K, A. R M, Poornima S, et al. Clinical, laboratory, and molecular epidemiology of Orientia tsutsugamushi infection from southwestern India. PLoS One. 2023;18(7):e0289126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0289126.

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, et al. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35(6):1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096.

- Watt G, Parola P. Scrub typhus and tropical rickettsioses. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2003;16(5):429–436. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200310000-00009.

- Kelly DJ, Fuerst PA, Ching W-M, et al. Scrub typhus: the geographic distribution of phenotypic and genotypic variants of Orientia tsutsugamushi. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48 Suppl 3(s3):S203–S230. doi: 10.1086/596576.

- Jiang J, Richards AL. Scrub typhus: no longer restricted to the tsutsugamushi triangle. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2018;3(1):11. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed3010011.

- Rathnasekara T, Wijekoon L, Senanayake H, et al. Rapid recovery of acute respiratory distress syndrome in scrub typhus, with pulse methylprednisolone and therapeutic plasma exchange. Cureus. 2022;14(10):e30329. doi: 10.7759/cureus.30329.

- Fisher J, Card G, Soong L. Neuroinflammation associated with scrub typhus and spotted fever group rickettsioses. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(10):e0008675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008675.

- Thap LC, Supanaranond W, Treeprasertsuk S, et al. Septic shock secondary to scrub typhus: characteristics and complications. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2002;33(4):780–786.

- Lobo SMA, Lobo FRM, Bota DP, et al. C-reactive protein levels correlate with mortality and organ failure in critically ill patients. Chest. 2003;123(6):2043–2049. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.6.2043.

- Peter JV, Karthik G, Ramakrishna K, et al. Elevated procalcitonin is associated with increased mortality in patients with scrub typhus infection needing intensive care admission. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2013;17(3):174–177. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.117063.

- Attur RP, Kuppasamy S, Bairy M, et al. Acute kidney injury in scrub typhus. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2013;17(5):725–729. doi: 10.1007/s10157-012-0753-9.

- Payen D, de Pont AC, Sakr Y, et al. A positive fluid balance is associated with a worse outcome in patients with acute renal failure. Crit Care. 2008;12(3):R74. doi: 10.1186/cc6916.

- Alobaidi R, Morgan C, Basu RK, et al. Association between fluid balance and outcomes in critically ill children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(3):257–268. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.4540.

- Shioi Y, Murakami A, Takikawa Y, et al. Autopsy case of acute liver failure due to scrub typhus. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2009;2(4):310–314. doi: 10.1007/s12328-009-0087-7.

- Gaba S, Sharma S, Gaba N, et al. Scrub typhus leading to acute liver failure in a pregnant patient. Cureus. 2020;12(9):e10191. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10191.

- Park JS, Jee YK, Lee KY, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome associated with scrub typhus: diffuse alveolar damage without pulmonary vasculitis. J Korean Med Sci. 2000;15(3):343–345. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2000.15.3.343.

- Acharya A, Bhattarai T. Meningoencephalitis: a rare presentation of scrub typhus. Cureus. 2022;14(9):e29597. doi: 10.7759/cureus.29597.

- Wu H, Xiong X, Zhu M, et al. Successful diagnosis and treatment of scrub typhus associated with haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome: a case report and literature review. Heliyon. 2022;8(11):e11356. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11356.

- Bonell A, Lubell Y, Newton PN, et al. Estimating the burden of scrub typhus: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(9):e0005838–e0005838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005838.

- Devasagayam E, Dayanand D, Kundu D, et al. The burden of scrub typhus in India: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(7):e0009619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009619.

- Munegowda K, Nanda S, Varma M, et al. A prospective study on distribution of eschar in patients suspected of scrub typhus. Trop Doct. 2014;44(3):160–162. doi: 10.1177/0049475514530688.

- Gulati S, Chunduru K, Madiyal M, et al. Validation of a clinical risk-scoring algorithm for scrub typhus severity in South India. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2021;25(5):551–556. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23828.

- Mahajan SK, Rolain J-M, Kashyap R, et al. Scrub typhus in himalayas. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(10):1590–1592. doi: 10.3201/eid1210.051697.

- Kim D-M, Won KJ, Park CY, et al. Distribution of eschars on the body of scrub typhus patients: a prospective study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76(5):806–809. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2007.76.806.

- Varghese GM, Rajagopal VM, Trowbridge P, et al. Kinetics of IgM and IgG antibodies after scrub typhus infection and the clinical implications. Int J Infect Dis. 2018;71:53–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.03.018.

- Gupta N, Joylin S, Ravindra P, et al. A diagnostic randomised controlled trial to study the impact of rapid diagnostic tests in patients with acute febrile illness when compared to conventional diagnostics (DRACO study). J Infect. 2021;82(6):e6–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.04.001.

- Behera SP, Kumar N, Singh R, et al. Molecular detection and genetic characterization of Orientia tsutsugamushi from hospitalized acute encephalitis syndrome cases during two consecutive outbreaks in Eastern uttar pradesh, India. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2021;21(10):747–752. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2021.0003.

- Fukuhara M, Fukazawa M, Tamura A, et al. Survival of two Orientia tsutsugamushi bacterial strains that infect mouse macrophages with varying degrees of virulence. Microb Pathog. 2005;39(5-6):177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2005.08.004.