ABSTRACT

Epistemic democracy implies that in order for democratic decisions to be legitimate, it is no enough that they are taken according to established democratic procedures. In addition, epistemic democracy demands that two additional demands should be fulfilled, namely that the decisions produced by a democratic process also are ‘fair’ and ‘true’. The fairness demand is in this article connected to the principle of human rights while the ‘true’ demand related to the propensity of representative democracy to produce outcomes that increases human well-being. Empirical research shows that representative democracy without a high quality of the institutions responsible for implementing public policies do not deliver increased human well-being. A special problem is that representative democracy has not turned out to be a safe cure against endemic corruption. The ‘quality of government’ factor thus implies control of corruption and also the rule of law and competence in the public administration. It is argued that meritocracy in the recruitment and promotion to positions in the public administration can serve to increase both the level of ‘fairness’ and the level of ‘truth’ in democracies.

The real epistemic problems in democracies are for real

My starting point in the discussion about the theoretical approach known as epistemic democracy is a critique. A very large part of the discussion in this approach has been focused on the alleged inability of representative democracy to handle the ‘aggregation of preferences’ problem in a way that will result in also representing the will of the voters (List & Goodin, Citation2001). The main problem held forth in this literature is the well-known Arrow impossibility theorem, stating that when voters have three or more distinct alternatives, no ranked order voting system can convert the ranked preferences of individuals into a community-wide (complete and transitive) ranking while also meeting a number of criteria that are the basis for a democratic voting procedure. Following Arrow, rational choice theorists inspired by William Riker’s Rochester school, denied value to voting. Based largely on Arrow’s theory, Riker’s Liberalism against Populism (Citation1982), declared democratic voting impossible, arbitrary and therefore meaningless. Cohen’s (Citation1986) article, which coined the term ‘epistemic democracy’, was largely written as a response to Riker and the Rochester School (Schwartzberg, Citation2015). Largely accepting Riker’s critique of populist democracy ‘in the abstract’, Cohen argued that an epistemic conception of democracy required, inter alia, ‘an independent standard of correct decisions – that is, an account of justice or the common good that is independent of current consensus and the outcomes of votes’. However, as argued by Mackie (Citation2003), Arrow’s independence condition, which is central to his approach, is not theoretically justified (see also Regenwetter, Citation2006; Wittman, Citation1995). Moreover, it is rejected by almost all human subjects as shown in behavioural social choice experiments (Mackie, Citation2014). Empirically, in ‘real politics’, voting cycles are almost completely absent, or trivial amongst the preferences of mass voters (Mackie, Citation2003, pp. 86–92; cf. Regenwetter, Citation2006). Mackie also shows that they are empirically undemonstrated (Mackie, Citation2003, pp. 197–377; see also Wittman, Citation1995) in actual legislatures. I thus agree with Mackie (Citation2014) that the ‘social choice’ problem, á la Arrow and Riker, is one of the most overblown and irrelevant discussions in the social sciences to have ever taken place (the Thomson Web of Science database shows that some 1500 published articles for the search terms ‘arrow’ and ‘theorem’).

My take on what is the important problem presented to us by the epistemic theory of democracy is thus different from the above. It is based on the notion that political (or democratic) legitimacy will be achieved if the process of representative democracy also produces ‘good outcomes’ (Brennan, Citation2016; Cohen, Citation1986; Estlund, Citation2008; Schwartzberg, Citation2015). The central idea is that we, as citizens, have reason to demand more than that the decisions that are produced by the democratic polity are carried out in a manner that is in line with procedurally correct democratic procedures. In addition, two other demands should also be fulfilled, namely that the decisions produced by a democratic process are ‘fair’ and ‘true’.

The problem of ‘fair’ can be illustrated by the rise of the Human Rights Agenda as a social movement, but also as a field in political theory. There are certainly numerous ways to interpret this remarkable change in the international political landscape (Neier, Citation2002), but it seems safe to state that one important implication is that the Human Rights Agenda sets limits on what is to be seen as ethically acceptable decisions and policies, even if these are decided by a procedurally correct and legitimate democratic process. An example of this can be found in the area of development policy. While democracy aid has become a major thing for many donors, the terms ‘democracy’ or ‘democratisation’ are nowadays almost always accompanied by the term ‘human rights’, clearly indicating that the aid and development community is not content with only ‘representative democracy’.

The problem of demand for decisions to be ‘true’ can be illustrated by the policies against the HIV-AIDS epidemic disease launched by the then democratically elected President of South Africa, Thabo Mbeki. Although these policies were decided and implemented in a system that followed all reasonable demands for being in line with correct standard procedures for decision making in a representative democracy, they were not ‘true’ in the sense that they were in not in line with the scientifically established knowledge about the causes and possible prevention of this disease. According to a conservative estimation, the policies launched by the South African government in this area caused the premature death of some 330.000 individuals (Chigwedere & Seage, Citation2008; Nattras, Citation2008).

In most democracies, what should be counted as ‘true’ in medicine and other sciences is usually left to the academic community but, in many cases social scientists and political philosophers are called in to provide knowledge that can inform decisions about public policies (Wolff, Citation2011). In sum, it is certainly easy to come up with examples of decisions that an ever so procedurally correct democratic parliament could, in theory, produce that most of us would simply reject and find illegitimate because the decisions in question would be in a clear conflict with what we believe is ‘true’ or ‘fair’. As stated by Goodin (Citation2004, p. 99), ‘outcomes that are undeniably democratic can be palpably unjust’. It should be underlined that the epistemic problems are not about ideological or materially generated differences in interests. There is no independent standard of fairness and no available ‘evidence based’ knowledge for deciding if a state should spend more money on pensions or child allowances. In addition, democracy requires that the losing minority is willing to accept decisions in cases like these because they perceive that procedural justice in the decision-making process has been respected (Esaiasson, Citation2010). Instead, the epistemic problem of democracy concerns decisions that we genuinely would think are ‘false’ like in the HIV/AIDS example above or patently ‘unfair’ such as gross violations of human rights.

As stated above much of the discussion of epistemic democracy has focused on a problem with little or no ‘real-life’ (or ‘real politics’) relevance, namely the problem of ‘cyclical majorities’ that are supposed to lead to inconclusive and arbitrary outcomes from standard voting procedures. This has largely been a purely deductive theoretical operation and when confronted with empirics hardly anything has survived (Mackie, Citation2003, Citation2014; Wittman, Citation1995). One problem, pointed out by Schwartzberg (Citation2015), is that the discussion of the epistemic problem of democracy has largely been decoupled from empirical research. Schwartzberg (Citation2015, p. 201) states that ‘because the viability of epistemic democracy as a normative strategy depends on its capacity to be realised in practice, testing the core mechanisms over a range of domains is essential’. If there has been any such discussion, it has been confined to the ‘input’ side of the democratic system in the sense that focus has been of the capacity of representative democracies to reach ‘fair’ and ‘true decisions in their parliamentary institutions. This is of course important since citizens certainly can suffer from parliamentary decisions that are in conflict with ‘true’ and ‘fair’. However, as is well-known from the large literature about policy implementation, what is decided by a parliament or a central government can be something that is very different from what is actually implemented by a state’s administrative agencies (Saetren, Citation2005). For citizens in general, the latter must be what is most important since this is how they are actually effected by what governments do. Several empirical studies of what causes citizens to perceive their government as legitimate has shown that procedural factors in the implementation process, such as upholding the principles of the rule-of-law and control of corruption, have a stronger impact on how citizens perceive political legitimacy than variable pertaining to democratic rights (Dahlberg & Holmberg, Citation2014; Gilley, Citation2006; Gjefsen, Citation2012). As Gilley states (Citation2006, p. 58), this ‘clashes with standard liberal treatments of legitimacy that give overall priority to democratic rights’. On way to think about this surprising result is the following: In elections around the world’s democracies, about a third of the electorate do not bother to vote. Even fewer use their democratic rights such as participation in demonstrations, signing petitions or writing op-ed articles. In many cases, voters live in a constituency where their vote will never matter. What happens with the life of these citizens that do not (or cannot) make much use of their democratic rights? In most cases, nothing. However, if they cannot get adequate health care to their children because they cannot afford the bribes demanded by the staff at the public health care hospital, if the police will not protect them because they belong to a minority group, it they cannot get the job in the city administration that they are most qualified for because they do not have the ‘right’ political connections, and if the fire brigade will not show when their home is on fire up because they live in the ‘wrong’ part of the city, their life will be seriously affected. From this micro-logic perspective, it is not unreasonable or irrational for citizens to take implementation issues more seriously than democratic rights when they make up their mind whether their government is legitimate. Given this, it is surprising that one cannot find analyses in the epistemic democracy approach that focuses on this policy implementation problem, that is, to what extent democratic states can also implement policies that are ‘true’ and ‘fair’.

Do democracies deliver policies that are epistemically fair?

There are unfortunately a number of current examples in which governments that have come to power in a procedurally acceptable way, have infringed civil liberties. It is not necessary to go to the developing world to find examples, there are several current examples of this problem in industrialised and fairly prosperous countries, such as Hungary (Kornai, Citation2015), Poland (Ascherson, Citation2016), Turkey (Turam, Citation2012), and maybe now also in the United States (Levitsky & Ziblatt, Citation2018). Without denying the importance of central civil liberties, the fairness problem I want to use in this analysis is of a somewhat different type and builds on recent works arguing for a connection between political corruption and human rights (Rothstein & Varraich, Citation2017). The basic and fairly novel idea is that corruption in many cases should be seen as a violation of human rights (Boersma & Nelen, Citation2010; Bohara, Mitchell, Nepal, & Raheem, Citation2008; de Beco, Citation2011; Pearson, Citation2013). This line of reasoning is that the right not to be discriminated against by public authorities, the right not to have to pay bribes for what should be free public services and the right to get treated with ‘equal concern and respect’ from the courts are in fact not very distant from what counts as universal human rights (Rothstein & Varraich, Citation2017). This is based on the notion that what people generally perceive as corruption is not confined to bribes. Instead, what is thought of as corruption can be various forms of favouritism related to the public sector in which money is not involved. For example, when a small business person can only get a contract if she has the ‘right’ personal connection in City Hall, or when jobs in the public sector are reserved for those belonging to the ‘right’ political party. As stated by Goodin, ‘the antithesis to justice is favouritism’ (Goodin, Citation2004, p. 100). It can be added that the preamble to the Council of Europe Convention on Corruption states, ‘Corruption threatens the rule of law, democracy and human rights’. Thus, democracies that cannot get corruption under control can be seen as violating the principle not to produce outcomes that cannot be judged as ‘fair’.

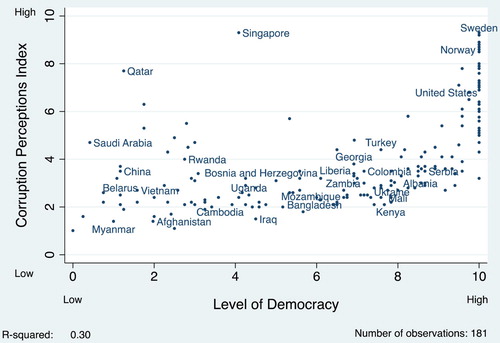

The epistemic problem for democracies here is that empirically, the correlation between standard measures of the level of democracy and the level of corruption is far from straightforward and positive. As the figure below shows, the relation between corruption and democracy is U- or J-shaped, implying that quite a number of autocracies have managed to get corruption under some control, while a large number of democracies have failed to do so (Chang & Golden, Citation2007; Chang, Golden, & Hill, Citation2010; Charron & Lapuente, Citation2011; de Sousa & Moriconi, Citation2013; Sung, Citation2004). Thus, not all democracies are equally blessed with the mechanisms to curb corruption and enable a state’s administrative capacity. To visualise this, the graph below plots the level of democracy, on one hand, and another widely used measure of corruption, namely Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index, on the other ().

Figure 1. Level of democracy and level of perceived corruption. Sources: Transparency International (2010); Freedom House (2010); Polity (2010).

In the top right corner, we find consolidated democracies, like the Scandinavian countries, New Zealand, Australia, Canada, and Japan, where democracy is rated as both very free and fair, and where we also observe low corruption. In the top left quadrant of the graph we find autocratic and semi-autocratic regimes like Singapore, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates. Simply put, the introduction of democracy is not a safeguard against corruption. Moreover, corruption is also high in a number of well-established democracies such as Italy, Greece and Spain (Charron, Lapuente, & Rothstein, Citation2013). The amount of money, and the influence of special interests in the United States, have made some scholars defining it as a country with a high level of corruption and what economists have labelled organised ‘rent-seeking’ (Teachout, Citation2014; Wedel, Citation2014; Zingales, Citation2012).

From the epistemic perspective, a very problematic result is that the ‘accountability mechanism’ in representative democracy that is to be secured by ‘free and fair’ elections seems not to work as the theory of representative democracy assumes (Achen & Bartels, Citation2016). That is, voters are often not punishing corrupt, dishonest or grossly incompetent politicians. Instead such politicians are quite often re-elected. To conclude so far, it seems safe to state that if minimising corruption as a part of human rights is taken as the empirical test for democracy’s ability to produce outcomes that are fair, we are facing a miserable result.

Do democracies deliver policies that are epistemically true?

In order to answer the question of whether democracy is able to deliver policies that are ‘true’ we have to come up with some idea of what ‘true’ could mean. In one of the most cited volumes about representative democracy, Manin, Przeworski, and Stokes (Citation1999, p. 29) state that this political system is based on the idea that ‘if elections are freely contested, if participation is widespread, if citizens enjoy political liberties, then governments will act in the best interests of the people’. Thus, the question about ‘true’ should be related to empirical investigation if policies, that can be said to be ‘in the interest of the people’, are actually implemented.

In the so called ‘mandate’ model of representative democracy, parties present programmes and platforms (bundle of policies) and argue how these would increase citizens’ welfare. Citizens evaluate ex ante which of these are most likely to be beneficial for their welfare and when the elected politicians implement the policies that will be beneficial for the well-being of the majority. Political parties seeking power will thus launch and implement welfare enhancing policies. In an alternative theory, known as ‘retrospective accountability’, voters evaluate ex post the performance of the political party or parties that have held power and if found wanting, because of being unable to increase the citizens’ welfare, the incumbents will be voted out of office. Knowing this, both incumbents and opposition will produce and implement welfare enhancing policies. In this theory, democratic elections serve as an accountability mechanism that prevents politicians from implementing policies that are detrimental to the well-being of the majority of the population. In both cases, however, the idea is that procedural fairness will result in outcomes that are in line with ‘the best interests of the people’. In a much acclaimed and discussed book, Christopher Achen and Larry Bartels (Citation2016) show that this theory of representative democracy has hardly had any support in empirical research. Voters are according to them too myopic, uninterested, short-sighted and uninformed for this theory to work and the system cannot produce ‘responsive government’.

Joshua Cohen seems to be the one who coined the term ‘epistemic democracy’. One of the epistemic requirements according to him was the capability of representative democracy to ensure ‘that the basic institutions that provide the framework for political deliberation are such that outcomes tend to advance the common good’ (Cohen, Citation1986, p. 31). Thus, all decisions in a democracy do not need to be in accordance with what we have reason to believe is ‘the common good’ for us to accept them, but there should be an overall tendency. Cohen also argued that there had to be an ‘independent standard’ of what should be seen as a ‘correct decision’, this is of course the central point in the epistemic notion of democracy, which implies that we should operate with ‘an account of justice or the common good that is independent of current consensus and the outcomes of votes’ (p. 34). Simply put, we should not accept whatever decisions a procedurally correct democracy delivers based on the notion that procedural fairness has been upheld. In addition, we should have some form of independent evaluation if the decisions are in line with ‘justice’ and the ‘common good’. This is highly problematic from a normative perspective because we have to ask who would be the right persons or expert for deciding what is ‘justice or the common good’, irrespective of what a democratically elected assembly may have decided. At least, this is a proposition that invites a fair amount of expert-based paternalism in politics. This is not a theoretical problem. For example, in their definition of what should be defined as ‘good governance’ experts (mostly economists) at the World Bank have included ‘sound policies’ (Kaufmann, Kraay, & Mastruzzi, Citation2005). A question is of course if these economic experts actually know what ‘sound policies’ is. After the factual collapse of the economic policies for developing and post-communist countries that came out from the World Bank (known as the Washington Consensus), the track record of this economic approach to development is not overly impressive, to put it mildly. However, if Manin, Przeworski and Stokes are correct, we do not need any such ‘independent standard’ for judging if the democratic system produces policies that are in the ‘common good’. Instead, we have reason to expect that the system of representative democracy is in line with the demand for ‘true’, in the sense that it is able to deliver policies that are ‘in the best interest of the people’. A reasonable interpretation of what this means is that the overall welfare of citizens should increase. This is a demand that we can evaluate from an epistemic point of view if we can come up with a measure of ‘welfare’ as a common good that we can agree upon. My suggestion for such a measure is based on the capability approach to social justice launched by Amartya Sen (Sen, Citation2009). This approach to justice is built on three basic ideas. The first is that the freedom to achieve well-being is of central moral importance and the second is that this requires that the individuals have resources that can be converted to capabilities. The third idea is anti-paternalism in the sense that it is not the professional philosophers that, as experts, decide what these capabilities shall be used for. Instead, it is the individual itself who is to convert these capacities to real opportunities to do and be what they themselves have reason to value (Robeyns, Citation2011; Sen, Citation2009; Wells, Citation2012). This has been translated into various metrics of what should count as ‘human well-being’ and has been influential for the well-known United Nations Development Program’s index of human well-being. This is not the place for a lengthy discussion or comparison of these metrics. Instead, the theory (including I) assume that most of us would prefer to live in a country where few newborn babies die, where most children survive their fifth birthday, where almost all ten-year olds can read, where people live a long and reasonably healthy life, where child deprivation is low, where few women die when giving birth, where the percentage of people living in severe poverty is low, and where many report being reasonably satisfied with their lives. We may also like to live in a society in which people think that the general ethical standard among their fellow citizens is reasonably high, implying that they perceive corruption to be fairly uncommon and that ‘most people in general’ can be trusted (Holmberg & Rothstein, Citation2015).

With this metric in hand, it is possible to empirically evaluate how well representative democracies perform in producing policies that increase human well-being by launching policies that de facto have a positive effect (‘true’) on the various measures of human well-being. Unfortunately the results are, for the most part, not reassuring. In an article published in The New York Review of Books in 2011, Amartya Sen compared ‘quality of life’ in China and India. As is well-known, Sen hailed the democratic system in India, several times, not least for being able to prevent famine. In this article however, he reaches the conclusion that on almost all standard measures of human well-being, communist and autocratic China clearly outperforms liberal and democratically governed India (Sen, Citation2011). This applies, inter alia, for infant mortality, mortality rates for children under the age of five, life-expectancy, immunisation of children, basic education of children, poverty rates and adult literacy. Sen comments on, but presents no explanation as to why India’s democratic system performs so poorly when it comes to improving human well-being for its population compared to autocratic China.

The problem with dysfunctionality in the electoral accountability mechanism has recently been underlined in an empirical study based on survey data for four states in southern Africa. The authors’ findings are both surprising and normatively disturbing. They state that:

a powerful normative justification for democratic government is that voters can hold politicians responsible for service delivery. And by rewarding good service, democracy should have positive effects on human development. Our analysis of four of Africa’s most robust democracies, with a focus on South Africa, demonstrates a pattern that cuts exactly against this grain: Voters who receive services may in fact be more likely to punish, and those who receive fewer services are more likely to stick with, the incumbent. (de Kadt & Lieberman, Citation2016, p. 47)

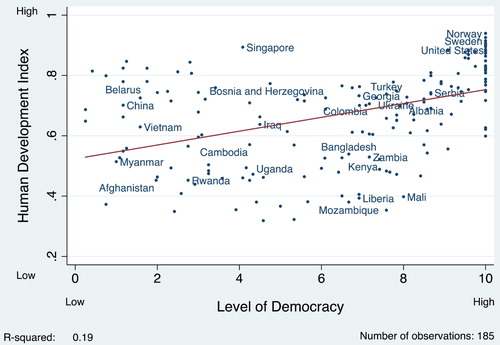

In a cross national comparative empirical analysis, Holmberg and Rothstein (Citation2015) examine the relationship between democracy and more than thirty standard measures of human well-being and development, including some related to the potential for public goods provision, such as the capacity for taxation. Ranging from 75 to 169 countries, depending on the variable, the study shows either weak, no, or even negative correlations between the level of democracy and the various measures of development. Plotting the level of democracy against the United Nations’ Human Development Index (HDI), which aggregates life expectancy, literacy, education, and income, into one score, illustrates the absence of any clear relationship in the figure below ().

Figure 2. Level of democracy and human development index. Sources: UNDP (2010); Freedom House (2010); Polity (2010).

Halleröd, Rothstein, Daoud, and Nandy (Citation2013) further add to the dismay of the lack of positive effects of representative democracy on development outcomes. Their study starts with a measure of child deprivation in 68 developing countries, with data for the access to safe water, food, sanitation, shelter, education, health care, and information. The data covers seven data-points for more than two million cases (children). Their analyses show no positive impact of democracy on any of the seven aspects of child deprivation, even when controlling for GDP per capita, while quality of government has a significant impact on four of the measures of child deprivation (Halleröd et al., Citation2013). It should be underlined that this ‘performance problem’ for democracies is not confined to developing countries. Charron et al. (Citation2013, Citation2018) has carried out two large-scale surveys with citizens in more than two-hundred ‘official’ regions in all EU countries. These surveys have aimed at measuring the quality of government in these regions at defined levels of corruption (perceived and experienced), as well as the impartial treatment of citizens. The findings show huge variation in quality of public institutions not only between EU countries, but also between regions within European countries. This European Quality of Government Index shows persistent positive correlations across the regions with many standard measures of human well-being (especially population health issues), as well as measures of economic performance. These studies also show that these differences in the ‘performance of democracies’ are causally related to the quality of the public institutions, both at the country and at the regional level of government.

In sum, the picture is this: Representative democracy is not a safeguard against extensive poverty, child deprivation, high levels of economic inequality, illiteracy, being unhappy or not satisfied with one’s life, high infant mortality, short life-expectancy, high maternal mortality, lack of access to safe water or sanitation, low school attendance for girls, systemic corruption or low interpersonal trust. If the ‘independent standard’ against which we should evaluate the epistemic qualities of existing democracies is the system’s capacity to deliver human well-being, the results are not overly impressive. However, if we instead of democracy take the quality of institutions that implement public policies into account, we find systematically positive correlations with the above-mentioned measures of human well-being.

The reasons why representative democracy often fails to deliver increased human well-being are manifold (for an excellent summary of the literature see Gerring et al., Citation2015). As mentioned above, there are good reasons to concentrate on one factor that has received substantial empirical support, namely what has been termed ‘quality of government’ (Rothstein & Teorell, Citation2008). The argument, in short, is that delivering policies such as universal health care, universal education, sanitation, immunisation, social insurances and physical infrastructure are large, complex and complicated operations that require considerable administrative competence and capacity. This is the case whether or not the state itself is the producer of such policies, or if they are contracted out to private or semi-private producers. In the latter case, high capacity and competence is required for enacting and monitoring contracts. In addition, in both cases there is ample room for corruption and other forms of malfeasance, for example nepotism, clientelism and of course outright bribery. As Fukuyama (Citation2014a, Citation2014b) has argued, the large majority of political scientists that study development concentrate their efforts on issues related to democratisation and pay little or no attention to issues related to state capacity. From an epistemic ‘fair and true’ perspective, this is problematic because, as argued above, it is variables related to state capacity, such as rule of law, control of corruption and administrative capacity, and not democratic rights that have positive correlations with almost all standard measures of human well-being. One could of course argue that the reason for democracy is to create political legitimacy and not ‘true’ and ‘fair’ outcomes, but the results stay the same. To conclude so far, from the perspective of human well-being understood as the practical implication of Sen’s capability approach, the general idea in epistemic democracy that ‘democratic decisions rightly oblige us because they are likely to be correct’ (Schwartzberg, Citation2015, p. 188) seems simply untrue or at least it has yet to be proven.

The meritocratic solution

For being able to handle the inability of many existing democracies to produce outcomes that are ‘true’ and ‘fair’, at least two things are needed. One is of course knowledge and competence in the sense that a democratically elected government needs to have capacity to ‘know’ what is ‘true’. Something must feed the system with knowledge of which type of policies are most likely to increase human well-being (at a reasonable cost for the taxpayer). The second demand is that the system should be institutionalised in ways so as to minimise corruption and corruption related problems in order to secure fairness in the implementation of policies. Ober suggests a model he labels, ‘relevant expertise aggregation’. The idea is not that we can rely on any general experts in politics, but that there are experts in various relevant fields of knowledge that should be consulted for weighing and ranking various options which are then put forward for a democratic decision (Ober, Citation2013). Putting up ‘ad hoc’ expert committees is of course one way to feed the political system with knowledge. The problem with this salutation may be precisely that it is an ‘ad hoc’ model meaning that once the specific committee of experts is dissolved, politicians do not have to take the experts into account any more.

Dahlström and Lapuente (Citation2017) have recently made a strong case for the positive effects on controlling corruption through a meritocratically oriented civil service. They argue that this does not only provide more competence to the political system, but that it also serves as a solution to the quality of government problem. They argued that when the power of democratically elected politicians is balanced by the influence of a meritocratic civil service, this serves as an inbuilt and compared to the ‘ad-hoc’ expert committees, continuous ‘checks-and-balance’ device against various forms of opportunistic behaviour, such as for example corruption. The causal mechanism they identify is that these two groups have different sources of legitimacy and that they are held accountable to different standards. Politicians in power base their legitimacy on the amount of electorate support they can muster and also the support they get from party activists to which they are held accountable. Meritocratic civil servants and experts in government base their legitimacy on respect within their peer-groups to which they are held accountable. Dahlström and Lapuente argue that when groups with different sources of legitimacy have to work closely together, they will monitor each other and this ‘pushes both groups away from self-interest towards the common good’. Logically, this also implies that ‘abuse of power will be more common if everyone at the top has the same interest, because no one will stand in the way of corruption and other self-interests’. Thus, what determines success or failure in these two groups are very different. This elegant theory is supported by a wealth of both historical and large-N comparative empirical analyses. Empirically, meritocratic recruitment of civil servants, as opposed to political appointment, is found to reduce corruption. This remains true even when controlling for a large set of alternative explanations, such as political, economic, and cultural factors, that previously were seen as important for the functioning of the public sector. The conclusion is that a professional bureaucracy, in which civil servants are recruited strictly on the basis of their qualifications and skills, rather than their loyalty to the politicians, is a very important factor for handling the ‘fairness’ question in the epistemic approach to democracy as it has been operationalised here. One mechanism behind this is that, when faced with corruption or inefficient management of public resources, it is easier for civil servants to protest or act as a whistleblower, than if he or she were dependent on and loyal to the politicians. The chance that someone exposes corruption or other forms of malfeasance is simply larger if the potential exposer is not dependent on those engaged in the corruption.

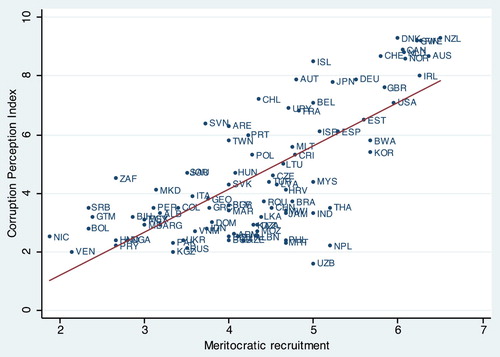

To this, one should add that meritocracy, everything else being equal, increases the competence in the public sector and thereby state capacity. Using data from an Expert Survey for the study of the public administration in 126 countries, carried out by the Quality of Government Institute, one finds a positive correlation between a measure of impartiality in the civil service and several standard measures of population health including the UNDP measure of human well-being (Rothstein & Holmberg, Citation2014). A study of Peru and Bolivia finds that the implementation of aid programmes can be seriously obstructed if there are high turnover rates among public sector employees, especially if they are recruited on a political basis (Cornell, Citation2014). The reason is that loyalty among politically recruited public officials lies with the appointing political party, rather than with the public institution, and politically recruited officials are therefore often reluctant to take over the implementation of aid programmes that have been established under the former government. This is problematic for development agencies, as the implementation timeline of aid programmes do not correspond to the term of office of the elected government that appoints public sector personnel. Yet another study finds that in democratic countries with a highly politicised recruitment process to the civil service, there is a strong likelihood that the production of knowledge, for example accurate statistics about the factual situation in the country, will be manipulated for the interests of the incumbent government (Boräng, Cornell, Grimes, & Schuster, Citation2017). The simple bi-variate correlation between meritocratic recruitment and corruption is, as shown in the figure below, quite impressive ().

Figure 3. Meritocratic recruitment and corruption. Sources: Meritocratic recruitment is taken from the QoG Institute’s Expert Survey (Dahlström, Lapuente, & Teorell, Citation2012) and the measure of Corruption is from World Bank Control of Corruption Index 2010.

It could be argued that meritocracy and corruption are linked by definition in that a low corrupt society will have less patronage in the public sector. Against this, I have two arguments. The first one is sequential. Historical studies indicate that the introduction of meritocracy in countries like Denmark, Britain, Germany, France and Sweden served as a mean to break systemic corruption (Dahlström & Lapuente, Citation2017; Rothstein & Teorell, Citation2015). A second argument comes from a comparison with the idea of electoral integrity. One could also argue that integrity in the electoral system and low corruption are linked by definition. However, as shown above, empirical research shows that they are not. There are, in principle, two ways for getting a position of power in the public sector in a democracy. One is by elections and the other is by system of recruitment to the civil service. The results from the research about meritocracy show that as an organising principle ‘free and fair’ recruitment (and promotion) to the civil service has a stronger positive impact on the quality of government than has ‘free and fair’ elections (Rothstein & Tannenberg, Citation2015).

Interestingly enough, Dahlström and Lapuente do not find a positive effect of, what is known as the ‘closed’ Weberian system of public administration with special exams, isolation from the private sector by special employment laws and guaranteed life-long employment.Footnote1 Instead, it is ‘open’ meritocratic systems, such as in Australia, Canada and Sweden, where employment in the civil service is open also for applicants from the private sector, and where there is not much difference in employment laws between the private and the public sector. The positive effect on controlling corruption comes only from meritocracy and a de-politicised civil service, while the traditional Weberian closed bureaucracy fails to deliver. Empirically, the extent to which the civil service is politicised in OECD countries varies enormously. Figures are somewhat uncertain, but the lowest seems to be Denmark where only about 25 ‘ministerial advisors’ are exchanged when there is a change of government. In Sweden, it is about 200, in Italy about 1600. In the United States the number of ‘spoils’ appointments are about 3500 and in Mexico about 70.000 civil servants have to leave their positions if results from a national election change the government (Garsten, Rothstein, & Svallfors, Citation2015). In most developing, and possibly also in former communist countries, the figures are in all likelihood much higher. In many democracies, elected governments seem not to be able to withstand the temptation to use their power over the state machinery for rewarding their political supporters.

Discussion

At least one political philosopher has found this epistemic problem so overwhelming that he suggests that we should abandon democracy (Brennan, Citation2016). From their empirically based critique of the ‘Santa Claus’ notion of representative democracy, Achen and Bartels (Citation2016) conclude that although this system cannot produce responsive governments, it still has a number of valuable effects. Among these, that democracy comes with the rule of law, change of government and peaceful change of governments, respect for civil rights, tolerance of opposition, and control of corruption. The last point is, at least, as argued above, questionable. Altogether, it is hard to imagine that it would be possible to come up with a perfect solution to the epistemic problem of democracy that would somehow guarantee against the decisions about public policies that were ‘unfair’ or ‘untrue’. A more reasonable expectation is to find some acceptable institutional devices that would increase the tendency that the democratic system would produce policies that are based on established knowledge/science and that are likely to increase the overall fairness in society. ‘Quality of Government’ has been conceptualised as impartiality in the exercise of public power (Rothstein & Teorell, Citation2008; Rothstein & Varraich, Citation2017). For the recruitment and promotion of personnel to the public administration, this principle translates into meritocracy. Applicants should be appointed or promoted based on their factual competence for carrying out the job, which of course excludes the importance of, inter alia, political connections. It is certainly possible to perceive meritocracy as a form of anti-democratic elitism. However, one could also interpret that meritocracy is the opposite to elitism in the sense that if combined with a reasonably universal system for education, it should give individuals from all social backgrounds a fair chance for upward mobility (Charron & Rothstein, Citation2016). What is serving the existing ruling elite is when the possibility for upward mobility is reserved to persons from families with the ‘right’ political connections. One part of what constitutes democracy, namely ‘equal treatment’ is thus built into the notion of meritocracy.

The empirical support for the positive consequences of meritocracy is strong and the theoretical argument for why this should be the case, as put forward by Dahlström and Lapuente, is logical and convincing. It should be underlined that the argument put forward for this solution to the epistemic problem in democracies is not ‘rule by experts’ or ‘rule by the civil service’. Plato was not right, we ought not to be ruled by the experts alone. Instead, this is more a ‘balance of power system’ where opportunistic politicians are held in check by professional civil servants/experts and where unelected civil servants/experts are held in check by democratically elected politicians. Such a system could maybe be labelled ‘rule through experts’. One argument for the positive effect of deliberative processes in democratic decision-making is that when arguments have to be presented to an audience of equals for discussion, the arguments are usually ‘laundered’. The effect of such ‘laundering’ seems to be that although self-interest can play a role, the argumentation must at least be dressed up to meet some standard for being in line with what can be considered as the ‘common good’. One could think of a similar effect in the ‘rule-through-experts’ that is suggested here. If politicians have to present and defend their policy proposals for a meritocratic group of highly competent civil servants or experts, outright false or patently opportunistic positions are less likely to be put on the table. Similarly, experts/civil servants are less likely to come up with policy solutions for which they believe the politicians have little chance to gain political legitimacy for. Thus, meritocracy can be seen as an additional, and I would argue, important ‘checks and balances’ ingredient in democracy. Alas, if President Thabo Mbeki had not been surrounded by his waste entourage of political cronies, but instead had to listen to the advice of HIV/AIDS experts, there is probably some chance that he would not have carried out the deadly policies he did.

Notes

1 Typical examples are Germany and South Korea.

References

- Achen, C. H., & Bartels, L. M. (2016). Democracy for realists: Why elections do not produce responsive government. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Ascherson, N. (2016, January 17). The assault on democracy in Poland is dangerous for the poles and all Europe. The Guardian. Retrieved from URL: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/jan/17/poland-rightwing-government-eu-russia-democracy-under-threat

- Boersma, M., & Nelen, J. M. (2010). Corruption & human rights: Interdisciplinary perspectives. Portland, Oregon: Intersentia.

- Bohara, A. K., Mitchell, N. J., Nepal, M., & Raheem, N. (2008). Human rights violations, corruption, and the policy of repression. Policy Studies Journal, 36(1), 1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2007.00250.x

- Boräng, F., Cornell, A., Grimes, M., & Schuster, C. (2017). Cooking the books. Bureaucratic politization and policy knowledge. Governance, 30(1), 1–20. doi: 10.1111/gove.12250

- Brennan, J. (2016). Against democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Chang, E. C. C., & Golden, M. A. (2007). Electoral systems, district magnitude and corruption. British Journal of Political Science, 37(1), 115–137. doi: 10.1017/S0007123407000063

- Chang, E. C. C., Golden, M. A., & Hill, S. J. (2010). Legislative malfeasance and political accountability. World Politics, 62(2), 177–220. doi: 10.1017/S0043887110000031

- Charron, N., & Lapuente, V. (2011). Which dictators produce quality of government? Studies in Comparative International Development, 46(4), 397–423. doi: 10.1007/s12116-011-9093-0

- Charron, N., Lapuente, V., & Rothstein, B. (2013). Quality of government and corruption from a European perspective: A comparative study of good government in EU regions. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Charron, N., Lapuente, V., & Rothstein, B. (2018). Mapping the quality of government in Europe. Stockholm: Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies.

- Charron, N., & Rothstein, B. (2016, April). Obstructing opportunity. Corruption and intergenerational social mobility. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago.

- Chigwedere, P., & Seage, G. R. (2008). Estimating the lost benefits of antiretroviral drug use in South Africa. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 49(4), 410–415. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818a6cd5

- Cohen, J. (1986). An epistemic conception of democracy. Ethics, 97(1), 26–38. doi: 10.1086/292815

- Cornell, A. (2014). Why bureaucratic stability matters for the implementation of democratic governance programs. Governance, 27(2), 191–214. doi: 10.1111/gove.12037

- Dahlberg, S., & Holmberg, S. (2014). Democracy and bureaucracy: How their quality matters for popular satisfaction. West European Politics, 37(3), 515–537. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2013.830468

- Dahlström, C., & Lapuente, V. (2017). Organizing the leviathan: How the relationship between politicians and bureaucrats shapes good government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dahlström, C., Lapuente, V., & Teorell, T. (2012). The merit of meritocratization: Politics, bureaucracy, and the institutional deterrents of corruption. Political Research Quarterly, 65(3), 656–668. doi: 10.1177/1065912911408109

- de Beco, G. (2011). Monitoring corruption from a human rights perspective. The International Journal of Human Rights, 15(7), 1107–1124. doi: 10.1080/13642987.2010.497336

- de Kadt, D., & Lieberman, E. S. (2016, April). Do citizens reward good service? Voter responses to basic service provision in South Africa. Paper presented at the GWU Conference on the Economics and Political Economy of Africa, Georg Washington University, Washington, DC.

- de Sousa, L., & Moriconi, M. (2013). Why voters do not throw the rascals out? — A conceptual framework for analysing electoral punishment of corruption. Crime, Law and Social Change, 60(5), 471–502. doi: 10.1007/s10611-013-9483-5

- Esaiasson, P. (2010). Will citizens take no for an answer? What government officials can do to enhance decision acceptance. European Political Science Review, 2(3), 351–371. doi: 10.1017/S1755773910000238

- Estlund, D. (2008). Democratic authority. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Fukuyama, F. (2014a). Political order and political decay: From the industrial revolution to the globalization of democracy. New York: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux.

- Fukuyama, F. (2014b). States and democracy. Democratization, 21(7), 1326–1340. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2014.960208

- Garsten, C., Rothstein, B., & Svallfors, S. (2015). Makt utan mandat: de policyprofessionella i svensk politik [ Power without mandate: The policy professionals in Swedish politics]. Stockholm: Dialogos.

- Gerring, J., Knutsen, C.-H., Skaaning, S.-E., Teorell, J., Maguire, M., Coppedge, M., & Lindberg, S. I. (2015). Electoral democracy and human development. Gothenburg: V-Dem Institute.

- Gilley, B. (2006). The determinants of state legitimacy: Results for 72 countries. International Political Science Review, 27(1), 47–71. doi: 10.1177/0192512106058634

- Gjefsen, T. (2012). Sources of legitimacy: Quality of government and electoral democracy (Master’s thesis). UiO DUO vitenarkiv.

- Goodin, R. E. (2004). Democracy, justice and impartiality. In K. Dowding, R. E. Goodin, & C. Pateman (Eds.), Justice and democracy (pp. 97–111). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Halleröd, B., Rothstein, B., Daoud, A., & Nandy, S. (2013). Bad governance and poor children: A comparative analysis of government efficiency and severe child deprivation in 68 low- and middle-income countries. World Development, 48(1), 19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.03.007

- Holmberg, S., & Rothstein, B. (2015). Good societies need good leaders on a leash. In C. Dahlstrom & L. Wängnerud (Eds.), Elites, institutions and the quality of government (pp. 101–124). New York: Palgrave.

- Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2005). Governance matters IV: Governance indicators for 1996–2004. Retrieved from www.worldbank.org/wbi/governance/pubs/govmatters4.html

- Kornai, J. (2015). Hungary’s U-turn: Retreating from democracy. Journal of Democracy, 26, 34–48. doi: 10.1353/jod.2015.0046

- Levitsky, S., & Ziblatt, D. (2018). How democracies dies: What history tells us about our future. London: Penguin.

- List, C., & Goodin, R. E. (2001). Epistemic democracy: Generalizing the condorcet jury theorem. Journal of Political Philosophy, 9(3), 277–306. doi: 10.1111/1467-9760.00128

- Mackie, G. (2003). Democracy defended. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mackie, G. (2014). The reception of social choice theory by democratic theory. In S. Novak, & J. Elster (Eds.), Majority decisions: Principles and practice (pp. 77–102). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Manin, B., Przeworski, A., & Stokes, S. (1999). Elections and democracy. In A. Przeworski, S. C. Stokes, & B. Maning (Eds.), Democracy, accountability and representation (pp. 29–54). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nattras, N. (2008). AIDS and the scientific governance of medicine in post-apartheid South Africa. African Affairs, 107(427), 157–176. doi: 10.1093/afraf/adm087

- Neier, A. (2002). Taking liberities: Four decades in the struggle for rights. New York: Public Affairs.

- Ober, J. (2013). Democracy’s wisdom: An Aristotelian middle way for collective judgment. American Political Science Review, 107(1), 104–122. doi: 10.1017/S0003055412000627

- Pearson, Z. (2013). An internation human rights approach to corruption. In P. Larmour & N. Wolanin (Eds.), Corruption and anti-corruption (pp. 30–62). Canberra: Asia Pacific Press.

- Regenwetter, M. (2006). Behavioral social choice: Probabilistic models, statistical inference, and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Riker, W. H. (1982). Liberalism against populism: A confrontation between the theory of democracy and the theory of social choice. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman.

- Robeyns, I. (2011). The capability approach. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Retrived from https://plato.stanford.edu/

- Rothstein, B., & Holmberg, S. (2014). Correlates of quality of government. Gothenburg: The Quality of Government Institute, University of Gothenburg.

- Rothstein, B., & Tannenberg, M. (2015). Making development work: The quality of government approach. Stockholm: Swedish government expert group for aid studies ( report 2015:17). Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg.

- Rothstein, B., & Teorell, J. (2008). What is quality of government? A theory of impartial government institutions. Governance, 21(2), 165–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0491.2008.00391.x

- Rothstein, B., & Teorell, J. (2015). Getting to Sweden, part II: Breaking with corruption in the nineteenth century. Scandinavian Political Studies, 38(3), 238–254. doi: 10.1111/1467-9477.12048

- Rothstein, B., & Varraich, A. (2017). Making sense of corruption. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Saetren, H. (2005). Facts and myths about research on public policy implementation: Out-of-fashion, allegedly dead, but still very much alive and relevant. Policy Studies Journal, 33(4), 559–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2005.00133.x

- Schwartzberg, M. (2015). Epistemic democracy and its challenges. Annual Review of Political Science, 18, 187–203. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-110113-121908

- Sen, A. (2009). The idea of justice. London: Allen Lane.

- Sen, A. (2011). Quality of life: India vs. China. New York Review of Books, LVIII(2011:25), 44–47.

- Sung, H.-E. (2004). Democracy and political corruption: A cross-national comparison. Crime, Law & Social Change, 41, 179–193. doi: 10.1023/B:CRIS.0000016225.75792.02

- Teachout, Z. (2014). Corruption in America: From Benjamin Franklin’s snuff box to citizens united. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Turam, B. (2012). Turkey under the AKP: Are civil liberties safe? Journal of Democracy, 23(1), 109–118. doi: 10.1353/jod.2012.0007

- Wedel, J. R. (2014). Unaccountable. How anit-corruption watchdogs and lobbyists sabotaged America’s finance, freedom and security. New York: Pegasus Books.

- Wells, T. R. (2012). Sen’s capability approach. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrived from http://www.iep.utm.edu/

- Wittman, D. (1995). The myth of democratic failure. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Wolff, J. (2011). Ethics and public policy: A philosophical inquiry. New York: Routledge.

- Zingales, L. (2012). A capitalism for the people: Recapturing the lost genius of American prosperity. New York: Basic Books.