ABSTRACT

The European Semester of socio-economic policy coordination has been criticised for poor capacity to induce national ownership of reforms. Reacting to these pressures, the European Commission intensified bilateral and multilateral efforts to increase the legitimacy of the Semester. European Semester officers (ESOs) were sent to Commission’s representations in Member States to reinforce policy dialogue. This paper spells out to what extent and how ESOs contribute to national ownership and throughput legitimacy of the European Semester in Member States. The findings suggest that ESOs are an important domestic link in fostering throughput legitimacy of the European semester by way of establishing dialogue with domestic actors and justifying the reasoning behind Commission’s initiatives. Conversely, they succeed less in transmitting stakeholders’ policy concerns and suggestions to the Commission. ESOs’ domestic engagement could, nonetheless, serve as an entry point for Commission’s future efforts in building domestic ownership and hence reducing blame-shifting practices.

1. Introduction

The economic, financial and sovereign-debt crisis in the European Union (EU) has deteriorated the legitimacy of the European project. Many citizens judge EU legitimacy on its output effectiveness. They applied this shortcut also during the crisis. Accordingly, we see a rise of exclusive nationalist identification after the crisis (Polyakova & Fligstein, Citation2016, p. 65), whereas the ‘losers’ of the Great Recession end up showing lower support for the EU (Gomez, Citation2015). After almost three decades of intense academic debate on the nature of EU’s democratic deficit, a crisis-ridden EU is now urged more than ever to cloak the EU polity with broad legitimacy (Piattoni, Citation2015, p. 3).

In 2011, a new system of coordinating socio-economic policies in the EU was implemented, the European Semester (henceforth: Semester). It works as an overarching surveillance architecture for early warning on fiscal and macro-economic instabilities, coordination of structural reforms and assessment of policy progress. It did not take long before first criticisms of the new structure were thrown to challenge the legitimacy of the new governance architecture. As a reaction, the European Commission (hereafter: Commission) introduced several legitimacy-seeking tools. Among other things, so-called European Semester officers (ESOs) were sent to Member States to bring the Semester closer to domestic actors. They are Commission’s economic experts send to Member States to follow the Semester on the ground and feed the Semester Country Teams with country-specific analysis, insights from the ground and actors’ sentiments. Against the backdrop of a crisis-driven austerity agenda the Commission realized that investment in Semester ownership in Member States would lend legitimacy and increase implementation of reforms. This paper anchors the question of Semester’s legitimacy into the broader discussion on the democratic legitimacy of EU’s post-crisis economic governance architecture. In examining the legitimacy of EU economic governance, the throughput dimension is particularly salient as it concentrates on the quality of deliberation, openness and accountability of socio-economic coordination (Fromage and van den Brink, Citation2018, p. 240). Therefore, this paper seeks to address the question to what extent and how ESOs enhance throughput legitimacy of the Semester by way of fostering domestic ownership of reforms. Applying a sender-receiver model, this study is an exploratory attempt to theorize and empirically test the role ESOs play in Semester governance.

In so doing, thematic analysis is used to unravel ESOs’ role-perceptions. The paper presents data from interviews conducted with ESOs, followed by 18 validation interviews with Commission officials, civil servants and stakeholders. Findings paint a mixed picture. On the one hand, there is evidence suggesting that ESOs contribute to Commission’s throughput legitimacy during the Semester cycle in that they, to some extent, foster ownership over EU-proposed reforms. They explain the reasoning behind Commission’s analysis, assessment and recommendations, and engage in argumentative discussions with a broad range of stakeholders. Despite this apparent success, ESOs are more limited in transmitting stakeholders’ messages upstream in the preparatory phases of the Semester, before the crucial documents are passed. In that regard, ESOs are, at best, valuable assets to the Commission in ringing the bell on potentially harmful tone and language of Semester throughputs. However, ESOs rarely find themselves in the position to enrich the substance or set the agenda of the Commission on suggestion by stakeholders.

The paper continues as follows. Section 2 summarizes the Commission’s role in the Semester governance architecture. Legitimacy concerns of the Semester are discussed in Section 3. Section 4 theorizes on the role of ESOs. Following a short note on methodology, the paper presents the findings. The final section concludes, explains the implications of the study and points to further research directions.

2. The European Semester and the Commission

The euro crisis brought to light the need to reform the Economic and Monetary Union. Among other crisis-management tools, a series of legislation was passed, for instance, the Six-Pack and Two-Pack. The new framework tightened the punitive aspect of economic governance, both in the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) and with creating a new Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure (MIP) (Coman, Citation2017). The European Semester is one of the key economic governance innovations launched in 2011 as part of this agenda. It is an annual cycle of socio-economic surveillance which streamlines existing coordination efforts, such as the Europe 2020 agenda, the SGP, the MIP and the Euro Plus Pact into one coherent process. Effectively, it monitors the implementation of (fiscal) rules and guidelines of multiple coordination mechanisms, some of which rely more on soft coordination (Europe 2020 strategy), whereas other combine soft and hard (law) tools (SGP, MIP) (Bekker and Klosse, Citation2014, p. 8). The Semester starts by setting EU-wide economic priorities in the Annual Growth Survey (AGS). The Commission then analyses fiscal and socio-economic developments in Member States, including progress towards area-specific guidelines and recommendations of the previous year (Country Report). Governments report in National Reform Programs on policy progress and intended efforts to meet EU-targets, rules and recommendations. These are assessed and followed by the creation of country-specific recommendations (CSRs), drafted by the Commission, approved by the Council and endorsed by the European Council. National governments put their reform plans into action or continue implementing existing policies throughout the year.

There is agreement that the new governance architecture increased the Commission’s authority over budgetary and macroeconomic monitoring, and strengthened its ability to monitor, analyse, assess and enforce socio-economic developments in Member States (Savage & Verdun, Citation2016, p. 101; Bauer & Becker, Citation2014). According to Dehousse (Citation2016, p. 29), DG ECFIN has continuously advocated the introduction of a structured economic governance framework that would monitor Member States’ commitment to reform agendas, fiscal and macroeconomic targets. The new economic governance structure and increased executive powers have raised concerns on the adequacy of democratic control (Fromage and van den Brink, Citation2018). This paper demystifies the role of ESOs in mitigating these concerns.

3. The Semester and throughout legitimacy

Scholarship has identified multiple ‘legitimacy gaps’ in the Semester architecture (Coman, Citation2017). The first gap concerns the legitimacy of integrating macro-economic, budgetary and social/employment procedures within the Semester. The strongly-felt primacy of economic objectives over social, gradual absorption of social and employment targets and objectives into the SGP and MIP, and encroachments into national prerogatives are seen by national governments as a threat to national sovereignty (Bekker, Citation2015). The punitive base of economic procedures may come at a double cost. Member States raise concerns regarding the legitimacy of such action which consequently imperils willingness to comply and ownership of reforms (Hallerberg, Marzinotto, & Wolff, Citation2012, p. 2). Another issue raised is the poor responsibility and low inclusiveness in the CSRs drafting process. Coman and Ponjaert (Citation2016) argue that Member States in the Council have only limited power to deflect the Commission’s angle on recommendations (cf. Zeitlin & Vanhercke, Citation2014, p. 44). A third objection highlights the asymmetric contribution of national parliaments and the European Parliament (EP) to Semester publications. Advocates of stronger parliamentary oversight claim that the Commission’s executive powers are not matched with sufficient democratic control (Barrett, Citation2018). A final concern is stakeholder participation which is necessary ‘to ensure broader social acceptance of reforms’ (Zeitlin & Vanhercke, Citation2014, p. 65). The degree to which civil society actors contribute to both EU-led and national processes in the Semester is considered unsatisfactory (EAPN, Citation2016).

The Commission pursues domestic ownership to solve the throughput legitimacy gap in the Semester. In general, throughput legitimacy of EU economic governance has received considerable attention in the post-crisis literature (Barrett, Citation2018; Fromage and van den Brink, Citation2018; Coman, Citation2017). The distinctiveness of the throughput concept must be clarified. Scharpf (Citation1999) initially distinguished two forms of legitimacy: input and output. In his view, input legitimacy is attained when political decisions follow the ‘will of the people’ and collective interests and preferences are preserved. In representative democracies, input legitimacy denotes the ability of policy-making systems to consider the interests of citizens-voters via majoritarian mechanisms of representative democracy. However, as Scharpf points out, input legitimacy of the EU is systematically flawed since the basic instruments of input legitimation are missing – electing and holding accountable an EU government and existence of a European identity/demos. Therefore, input legitimacy is a less fruitful avenue for assessing Semester’s legitimacy.

Contrarily, decision-makers derive their output legitimacy from solving collective problems effectively. Output legitimacy then reflects the capacity to design policy solutions considered effective and appropriate by the people, which can be controlled by mechanisms of political accountability (i.e. elections). Similarly, the Commission can influence output legitimacy only indirectly as ultimate decision-making powers lie in the hands of Member States who, albeit the fiscal and macro-economic constrains defined in the Semester, create fiscal, macroeconomic and social/employment policy. Primary responsibility for policy outcomes lies with national governments. They are concerned about output legitimacy as they are the ones to be held accountable for policy choices. It is rather the mechanism of ‘throughput legitimacy’ which is central in ownership creation of the Semester. Throughput legitimacy depends on the quality of the governance and policy-making process. Compared to ‘output’, the concern is not with policy performance. ‘Throughput’ is rather ‘process-oriented and based on interactions – institutional and constructive – of all actors engaged in EU governance’ (Schmidt, 2015, p. 5). Throughput legitimacy is then evaluated based on both the inclusiveness and openness of the Semester governance process to various stakeholders, and the capacity for deliberation and persuasion (Schmidt, 2015, pp. 6–7). Efficacy, accountability and transparency of the governance process are equally important. Unlike some perspectives which conflate input and process (throughput) legitimacy (Weiler, Citation2012), the nature of throughput-oriented interactions is different from input-related participation. Citizens’ input demands are channelled in the form of elections, protests, referenda and similar forms of interest articulation, whereas throughput participation is linked to involvement of domestic actors in institutional decision-making processes (Schmidt, 2015, p. 7). Moreover, the difference between input, output and throughput is that better input participation and more effective policies improve the public perception of legitimacy, while better throughput is publicly less valued. Nonetheless, it is equally important to focus on quality of the throughput process as lack of transparency, openness, inclusiveness or accountability can be detrimental for the public perception of legitimacy (Schmidt, 2015, pp. 8–9).

The Commission sees the creation of domestic ownership as a key mechanism to achieve Semester’s throughput legitimacy. This paper draws on Vanheuverzwijn and Crespy (Citation2018) to conceptualize ownership. They distinguish between institutional, political and cognitive ownership. Each addresses the deficit in Semester’s throughput differently. Institutional ownership is achieved when domestic actors, especially national administrations, are able to contribute to Semester outcomes meaningfully so that their policy arguments and expertise influence policy debates and recommendations at EU level. This dimension emphasizes active participation and substantive impact on policy-making. Political ownership denotes instances when there is convergence in opinion between the EU level and domestic actors regarding policy goals or means proposed in the Semester cycle. When agreement is reached on what policies should be pursued, throughput legitimacy is strengthened, and domestic actors will be able to use the Semester objectives as a strategic reference. This dimension values consensus-building and as such is closely related to building institutional ownership since the later rests on deliberation. Finally, cognitive ownership reflects the degree to which domestic actors have come to perceive Semester policies as something standard and not alien or imposed by the EU. Cognitive ownership should lead domestic actors to ‘consider policies promoted from outside as normal, as being their own’ (Vanheuverzwijn & Crespy, Citation2018, p. 582). Thus, this dimension underscores information provision, awareness raising and persuasive action from the EU level. These three ownership dimensions should improve the inclusiveness of the Semester process and translate into greater throughput legitimacy. The capacity for ownership creation in the Semester will depend on the inclusiveness and transparency of the process of formulating and disseminating Semester documents to national authorities, social partners and civil society. Building ownership is especially important for policy implementation in Semester areas in which the EU cannot sanction policy inaction.

The Commission has been well-aware of the Semester’s early legitimacy gaps and therefore initiated formal and informal adjustments to the design of its architecture to appease legitimacy concerns (European Commission, Citation2017). First, Commission’s extended responsibilities within the Semester caused some changes in the organizational structure of DGs. They now increasingly rely on the expertise and knowledge of desk officers who form Country Teams (Savage & Verdun, Citation2016). Staff is in permanent contact with Member States, they exchange information and meet bilaterally in sectoral ‘fact-finding missions.’ This process should mitigate potential conflict over EU initiatives. In most cases the Commission will act on the principle of ‘anticipated reactions’ therefore recommendations will rarely contradict the will of Member States so as not to antagonize domestic leaders (Dunlop & Radaelli, Citation2016, p. 120). The bilateral exchanges should make sure the CSRs are ‘sufficiently precise as regards policy outcomes but not overly prescriptive as regards policy measures so as to leave sufficient space … for national ownership’ (Coman & Ponjaert, Citation2016, p. 48). Second, regarding parliamentary accountability and scrutiny in the Semester, the EP interacts with the Commission and the Council within the Economic Dialogue procedure. Parliamentary committees can invite the President of the Council, the Commission, Member States or the Eurogroup to discuss Semester issues. In addition, the adoption of the AGS or CSRs is discussed in the EP, however in both cases the EP has no voting right. Concerning national parliaments, their involvement in EU economic governance has improved (see Fromage and van den Brink Citation2018), albeit the form and degree of involvement in Semester processes varies considerably across Member States. Hallerberg, Marzinotto, and Wolff (Citation2018) stipulate that budgetary committees have become more active while parliaments in Member States outside the eurozone engage more in the monitoring of CSRs’ implementation. In total, however, even when parliaments acquired greater oversight rights, they did so ‘only in the lower ranges of accountability mechanisms (information, consultation and debate)’, whereas only the Latvian parliament acquired hard competencies to approve or amend the Stability Programme (Crum, Citation2018, p. 275). Similarly, Barrett (Citation2018, p. 259) concludes that parliamentary involvement in EU economic governance (incl. Semester) is limited. However, he Juncker administration encourages Commissioners to visit Member States and engage in dialogue with parliamentary committees on Semester processes. Further procedural changes happened under the Juncker Commission in an attempt to ‘revamp the European Semester’ (European Commission, Citation2015). Concerned about prospects of having productive bilateral and multilateral dialogue on Country Reports and CSRs and genuine stakeholder involvement, the Commission streamlined the Semester to create more time for dialogue and space for national ownership of reform initiatives (Zeitlin & Vanhercke, Citation2014). This paper looks into European Semester Officers. Striving to ‘gradually establish a deeper and more permanent dialogue with the Member State’ (European Commission, Citation2015), the Commission seconded these economic experts to Commission’s Representations to Member States in order to increase Semester’s throughput legitimacy. This paper asks the question to what extent ESO’s have contributed to the Commission’s quest for throughput legitimacy by building domestic ownership of the Semester.

4. Theorizing the role of ESOs

ESOs are Commission employees deployed to Member States to add weight to the Commission’s capacity to conduct surveillance activities, assess policies, gather country-specific intelligence and increase the compliance record on Semester initiatives. They are members of Country Teams led by SECGEN which consist of desk officers responsible for monitoring Semester issues in individual countries. ESOs are central to the agenda of improving domestic ownership of reforms and to narrow down CSR implementation gaps (Coman & Ponjaert, Citation2016, p. 42).

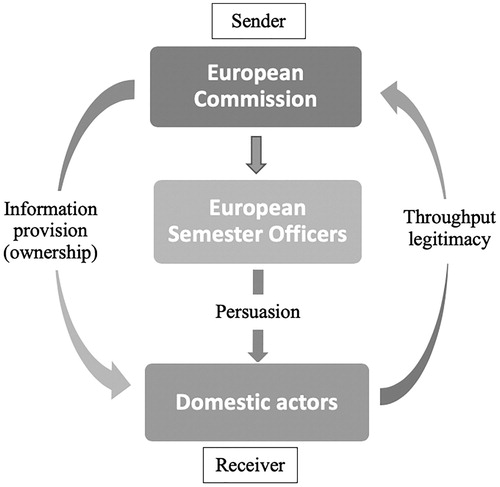

As intermediaries, ESOs link two levels in the Semester – the Commission on the one hand, and (sub)national actors on the other. Their work resembles a two-way communication process of information transmission. They help facilitate communication processes. Drawing from the political communication literature, the relationship between the Commission and the domestic tier, and the role that ESOs play in this relationship can be conceptualized via a sender-receiver model (Berlo, Citation1960). Two types of resource exchanges can be distinguished which explain the relationship between a sender and a receiver, one of which is more relevant for building cognitive ownership (model 1), whereas the other intents to foster institutional and political ownership (model 2). In the first model (), the Commission acts as a sender of information and seeks to exchange information for throughput legitimacy (cognitive ownership) granted by domestic stakeholders – national administrations, social partners, interest groups and civil society. This happens when the main ‘commodities’ of the Semester are published – the AGS, Country Reports and the CSRs.Footnote1 The Commission sends a clear message to national authorities and other stakeholders on the annual priorities of the Commission, on problems in the national economy and on recommendations which address domestic policy challenges. Since information provision is crucial for cognitive ownership, the Commission publicly announces these documents and engages in discussion with Member States on implementing the recommendations. Furthermore, the level of cognitive ownership that is created depends on the quality of debating and communicating EU requests domestically. This is where ESOs are central. They ought to facilitate the discussion on policy proposals, explain the reasoning behind Commission’s requests and persuade domestic actors embrace a reform agenda. This objective is pursued either in bilateral or multilateral fora, and the goal is to motivate relevant stakeholders to work towards the implementation of the recommendations and see them as being their own, and not as foreign-imposed. The Commission has an interest in avoiding the perception of imposing measures but wishes to build domestic alliances and increase the cognitive ownership of the proposed policies. ESOs ought to make Commission’s requests amenable to stakeholders, but also to the general public so as to pre-empt anti-EU backlashes. They are expected to contribute to EU’s communicative discourse by way of deliberating and demystifying Semester’s substantive impact both in public and consultative fora as a means of minimizing blame-shifting on the EU (Schmidt, Citation2004). The greater ESOs’ ability to argue persuasively and communicate clearly Semester documents to domestic actors, the higher the throughput legitimacy (Expectation 1).

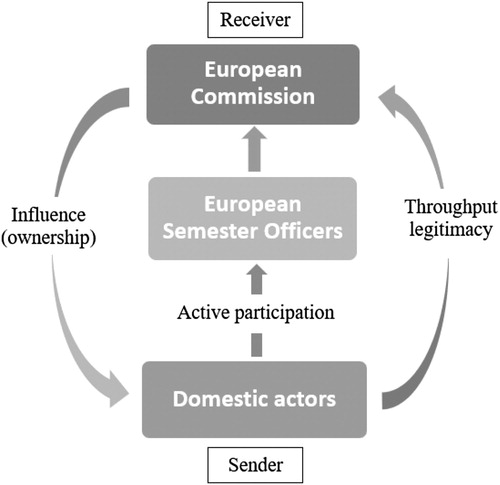

Whereas model 1 outlined a top-down, ex-post process in which the information flow starts only after Semester documents have been passed, model 2 () reflects a bottom-up, ex-ante relationship between the domestic level and the Commission in the Semester’s preparatory phases. In this model, the roles are reversed – national actors act as senders (suppliers), and the Commission is the receiver. The Member State level has an interest in voicing their opinion on Semester documents by providing views, policy concerns and solutions. They also seek to upload domestic agendas to the EU level. In so doing, domestic actors, in this case both government and social partners, civil society and interest groups, may seeks to minimize potential adjustment costs or build leverage from below. The level of inclusiveness of actors in this process and the influence that they manage to exert on Semester documents will determine the degree of institutional and political ownership created, and thus the level of throughput legitimacy transferred to the Commission. On the receiving side, the Commission may want to increase participation with the prospect of being rewarded with greater throughput legitimacy whilst minimizing conflict. Domestic actors are then expected to develop political and institutional ownership. ESOs should fit into the picture by providing a deliberation-conducive setting for stakeholder inclusion. Their ability to activate the ‘listening mode’ and foster active participation is key, because their position of being on the ground gives them a comparative advantage compared to Brussels. From a domestic actor perspective, ESO’s work will be evaluated based on how successfully they transmit their views to the Commission, which in turn, depends on the Commission’s responsiveness. It is expected that the greater ESO’s and Commission’s ability to include, consult, and transmit the concerns of the government and a wide range of interest groups in Semester’s preparatory phases, the higher throughput legitimacy (Expectation 2).

5. Methodology

This paper uses thematic analysis to find out to what extent and how ESOs increase throughput legitimacy of the Semester (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The exploratory nature of this investigation warrants the use of thematic analysis as it is a flexible ‘method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data’ (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, p. 78). Guided by theoretical expectations proposed in the previous section, a two-step interview strategy is employed.

First, 22 semi-structured (phone) interviews were conducted with ESOs in the period between May 2016 and February 2017 to identify themes relevant for investigating ESOs’ role in fostering throughput legitimacy in the Semester. Interviews were conducted with individual ESOs from 22 Member States.Footnote2 They are considered to reflect perceptions, experiences and understandings of ESOs. Investigating ESOs experiences lies at the heart of this research. However, the methodological concern is that ESOs’ perspectives are too biased for credible claim-making on ownership. Although this concern is justified, the large sample size of ESOs increases confidence in the generalizability of findings. It also mitigates the possibility of interviewees’ subjectivity on the matter as the analysis focuses on patterns, and not on anecdotal evidence. To ameliorate existing credibility concerns, secondly, 18 supplementary validation interviews were conducted with Commission officials (high-ranked officials and desk officers), national administrations and stakeholders (see Supplemental Material). As they are, in terms of the theoretical framework, senders and receivers in the Semester, they are well-placed to offer independent evidence on ESOs’ contributions to Semester’s legitimacy.

Data analysis was conducted in NVivo11 Pro. Relevant themes were coded partly deductively (theory-driven) and partly inductively (data-driven). First, ESOs’ reflection on the different types and scope of activities that they cover in their daily work were extracted and coded inductively. Second, for testing ESOs ability to argue persuasively and communicate clearly the Country Reports and CSRs to domestic actors (cognitive ownership), respondents were asked whether they think their work contributed to greater acceptance of the Semester throughputs and to reflect on their presence in the media. Two indicators captured their responses – level of publicity and ownership creation. Although not a perfect indicator, publicity indicates ESOs’ capacity for communicative discourse as posited by Schmidt (Citation2013). The assumption is that, if regularly present in the media, the higher the chances of adding an EU perspective to the debate that counterbalances the filtering of European policies through national lenses in domestic media (Polyakova & Fligstein, Citation2016, p. 64). Throughput legitimacy in the sense of political and institutional ownership can effectively be operationalized as ‘quality of participation’, measured by the inclusiveness/equality of actors, level of consideration given to domestic actors’ inputs and domestic actors’ degree of influence on the Country Reports and CSRs (Iusmen & Boswell, Citation2017, p. 464).

6. Findings

ESOs describe their role as twofold – first, reaching out to Member States with Semester information, and second, informing the Commission about the concerns of domestic actors (ESO2; ESO17; ESO19). Substantively, ESOs predominantly conduct policy monitoring and report back to the Country Team. They feed the Commission with Semester-relevant policy developments. The majority of ESOs seem to be involved in monitoring political developments too, tasks traditionally ascribed to attachés (ESO6). Another substantive task is meeting various stakeholders – either to explain and disseminate Semester documents (AGS, Country Reports, CSRs) or to listen to their perspective on policy issues and reforms (ESO20).

In procedural terms, ESOs are involved in regular reporting, briefing and coordination activities. They are largely involved in coordinating sectoral fact-finding missions. They prepare visits, occasionally set the agenda (ESO18) but generally make sure to liaise between Commission officials and national authorities/stakeholders (ESO11). Their work in that regard is mostly administrative – to make sure the right people meet and exchange information on Semester issues.

6.1. Building legitimacy through cognitive ownership

A bulk of ESOs’ work concentrates on creating ownership of Semester processes, both from above and below. From above, ESOs engage in argumentative action with national authorities and stakeholders (civil society, social partners, think tanks, academia, private sector) to justify the rationale behind certain policy analysis in the Country Report or CSRs. Such on-the-ground activities exist in most member states. In general, ESOs trust that their work during the Semester helps create a sense of cognitive ownership among domestic actors or at least makes a difference as compared to periods where there was no ESO in the Member State. Some (ESO19; ESO4; ESO9) received feedback that their daily engagement in explaining and communicating the Semester helped change the negative image or stigma of the Commission being synonymous to fiscal consolidation. ESOs’ presence makes: ‘the involvement of the Commission now being perceived differently than before … ’ (ESO9).

When it comes to creating reform ownership, only one ESO explicitly denied positive impact of various information-providing activities organized by ESOs. A vast majority of other ESOs are more optimistic about their impact. Outreach activities to local and regional municipalities, parliamentary committees, bilateral meetings with ministry officials and fact-finding missions with stakeholders are believed to increase the national ownership of reform agendas in the sense that Semester recommendations and analysis are not seen as being imposed on them from outside (cognitive ownership). The effect is at times empowering in that the argumentation and analysis done by the Commission is seen as being used as a lever in domestic policy discussions (ESO14). Authorities tend to selectively cherry-pick initiatives that are ‘politically amenable’ (ESO6). In many cases, ESOs note willingness to engage in reforms only when they suit pre-defined governmental agendas (ESO14). In essence, domestic actors use the Semester strategically to bolster their agendas. In such instances when there is agreement between the Semester and domestic actors which policy goals or instruments should be attained, ownership can be created, and the throughput legitimacy of the Semester is increased. Contrary, lack of agreement on the fundamental logic of a policy intervention can lead actors to contest the appropriateness of Semester recommendations which inhibits cognitive ownership.

Many ESOs believe their explanations and arguments on the policy rationale can impact positively on the understanding of what the Commission wants to achieve within a specific proposal. ESOs are engaged in smoothening potential policy controversies (ESO5), in building trust between the EU-level and domestic actors (ESO2), but also in contributing to the pace of policy change on the ground (ESO4). On the other hand, a vast majority of ESOs are often the ones initiating contacts with civil society actors and social partners. Nevertheless, social partners and civil society from the interview sample did not share the enthusiastic view on the distinct effect of ESOs: ‘We do get invited to these roundtables, but that’s about it’ (CSO01). Activities that are organized fit the purpose of dissemination of information, but as such do not contribute significantly to other forms of ownership beyond cognitive. One ESO summarized the nature of ownership which is expected to result from interactions with stakeholders: ‘We consider stakeholders to be multipliers who use CSRs and argumentation in their own work, so that the Semester becomes relevant in their work and they feel ownership’ (ESO21). The regular contacts between ESOs and stakeholders are helpful in building such cognitive ownership as ESOs invest in argumentative, persuasive action on the ground.

The qualitative analysis identified four reasons why ESOs’ power of persuasion might, however, be impeded. These include agenda proximity, electoral risks and issue salience, government sentiment towards the EU, and temporal expectations. First, as existing Europeanization literature teaches, domestic actors will be more likely to embrace a reform initiative if it fits their existing paradigms, activities and agendas (Büchs, Citation2007). Second, governments fear electoral losses and thus have little appetite for initiatives which might endanger the prospects of re-election. This problem mostly pertains to ‘unpopular measures’ which trigger negative popular reaction – such as pension reforms, social policy interventions or healthcare issues. Governments are mostly aware of existing problem loads but decide to postpone structural reforms so as not to intimidate their constituencies. Third, much depends on how the EU is perceived domestically. Changes in government, for example, from Eurosceptic to pro-European is reported to make a huge difference in how ESOs work was appreciated (ESO5). Finally, the Commission and the national authorities may have different expectations about the timing of certain reforms, how long it may take for a reform to bear fruit. Sometimes the same CSRs are repeated year after year, when the problem does not seem to be lack of ambition on behalf of the government, but rather divergent expectations on how fast reforms can be rolled out.

This being said, ESOs seem to make some, but not much substantive difference in how domestic actors perceive the Commission’s engagement with domestic policy. Stakeholders become increasingly aware of policy problems as a result of Semester’s dissemination activities. But how successfully do ESOs engage in communicative discourse with the broader public? They barely do so. ESOs are expert staff, not political appointees. As reported by a dozen of ESOs, their publicity is low and intensity of media presence is low. Their capacity to engage with the broader audience on TV, radio or newspapers is constrained by strict rules and instructions prohibiting public appearance without clearance. They are confined in their efforts to communicate Semester issues to the public due to internal policy. However, experiences vary between Member States. There are instances where ESOs are quite active on social media or in classical media. Still, it appears that not all ESOs favour a pro-active approach. Some fear the risk of being drawn into political confrontations (ESO17, ESO19), others would appreciate more training in media appearance (ESO22). Yet again, others see no point in creating restrictions: ‘It’s a bit bizarre to be sent to countries to communicate, but not being able to communicate to media’ (ESO21). Hence, the evidence adds some weight on ESOs contribution to increasing throughput legitimacy via cognitive ownership among civil servants and stakeholders, whereas the capacity for more communicative discourse and engagement with the broader public is fairly limited.

6.2. Building legitimacy through political/institutional ownership

As demonstrated, one of ESOs’ crucial instruments of seeking legitimacy is domestic actors’ inclusion in the formulation of Semester documents. Most of this work includes coordinating bilateral meetings of fact-finding missions and post hoc dissemination of information during the second half of the Semester (ESO13). It would seem that ESOs’ ability to transmit information up the hierarchical ladder is indirect, and their influence on the substance of documents limited. Nonetheless, many ESOs engage with authorities and stakeholders to receive inputs and feedback on policy developments, which are then communicated to Country Teams. In that sense, one of the criteria for quality participation is satisfied – ESOs value domestic insights highly and give them great consideration. To answer whether domestic actors can influence the content of Semester throughput is more intricate. But before answering, one needs to assess the inclusiveness and equality of stakeholder participation. Roughly three thirds of ESOs give uneven attention to various stakeholders. Some establish contacts predominantly with government officials and civil servants, others focus on social partners and NGOs. In the first half of the Semester, ESOs interact more intensively with national authorities to assess policy progress (ESO7), whereas the second part is reserved for social partners’ feedback. Others see no point in focusing on institutional actors which have easy access to Brussels (ESO9; ESO22). As a result, it would not be prudent to accuse ESOs for negligence. On the contrary, most ESOs show great interest in conveying messages to the pen-holders. The real question is do ESOs’ attempts make any difference?

If we judge upon ESOs’ impressions on the substance of the Semester – the Country Reports and the CSRs, the picture is blurred. Perceptions are equally split between those who think CSRs are beyond their influence and those who feel that their analysis is reflected in final versions of Country Reports and CSRs. Although it would an exaggeration to claim that ESOs draft chapters, those who see their influence reflected in the Country Report regularly contribute with comments on the analytical part of the reports. Their opinions are usually ‘taken on board’ (ESO19; ESO21). A number of ESOs had agenda-setting powers in that, on the one hand, they managed to include issues and topics in the Country Report that would have otherwise been excluded (ESO5), and on the other, they were able to convince the Country Team leader not to include a certain issue for which he believed might antagonize the Member State in question (ESO9). One interviewee put it this way: ‘I have been fighting with the Country Team to include vocational education and training and labour shortages in the Country Report … they were reluctant, but they nevertheless included it’ (ESO5). Whether or not they can influence the substance, depends sometimes on the dynamics in the Country Team and how open the leader is to inputs (ESO14; ESO16; ESO20). Moving from substance to wording, a majority of ESOs confirm their influence on the language, phrasing, tone and wording in the Country Report. They would regularly point to controversial language which might cause domestic uproar. This finding confirms that having economic experts on the ground who understands the domestic landscape, feel the stakeholders’ sentiment and monitor the socio-political circumstances, can help pre-empt negative reactions to initiatives from Brussels. It adds weight to the claims that the Commission is increasingly acting as a strategic entrepreneur that is ‘reluctant to endorse … initiatives that stand little immediate chance of success’ (Hodson, Citation2013). This is further corroborated by the recent trend of giving national authorities the possibility to have a look at the Country Report before publication.

Turning to CSRs, a widely-held impression amongst ESOs is that the drafting of recommendations is still a ‘black-box’ beyond their sphere of influence: ‘What comes out is completely out of the scope of my awareness’ (ESO6). The only time that ESOs comment on the CSRs, if at all, is in the first version of the document. Only two ESOs claimed to have managed to change the wording of the CSRs, but most ESOs fear to see unexpected surprises on publication day. They generally see it as a more political process in which SECGEN reportedly has high autonomy to decide what goes and what not, based on the political instruction of the College of Commissioners and issue prioritization (see below). One ESO compared the situation now and before:

We are involved in the first drafting, but later it goes to SECGEN and we are cut out. It has become more closed with the Juncker Commission because the process has become more political. It is a real black-box for us. This was not the case before, until 2015. (ESO21)

Validation interviews with Commission staff () confirmed that ESOs’ substantive contribution to the drafting process is limited, whereas most interviewees regarded ESOs as helpful advisers on national political/policy developments and sentiments of key domestic actors. Having little substantive say on the CSRs and Country Reports, ESOs are unlikely channels for pushing upstream concrete suggestions by social partners and interest groups, the more so given the fact that none of the interviewed stakeholders considered ESOs to be useful means of influencing the Semester process (TU01, TU02, TU03, CSO01, CSO02). This finding resonates with Sabato and Vanhercke’s (Citation2017) conclusion that national social partners are only being ‘listened to, but not heard’ in the Semester and the general feeling that interactions with the Commission on Semester documents is not considered ‘full involvement, just a process of sharing information’ (Eurofound, Citation2018, p. 1). Domestic stakeholders are therefore more likely to develop cognitive, rather than institutional and political ownership.

Table 1. Commission staff experiences with ESOs.

The findings also confirm the centrality of SECGEN and DG ECFIN in the drafting of Semester documents. SECGEN is not only crucial for the internal co-ordination in the Commission, but it also carries out the political agenda of the President’s cabinet – becoming ‘almost an extension of the President’s cabinet and enforcer of his agenda’ (Peterson, Citation2017, p. 352). This is in line with President Juncker’s vision of the Commission being less of a technocratic institution. He prefers ‘not to dictate what countries have to do’ but ‘ … listen to countries. You have to understand what is happening in different countries’ (Dinan, Citation2016, p. 108). ESOs have confirmed that President Juncker is willing to pursue dialogue with national authorities on matters of the Semester both on expert level, with deliberation-based multilateral surveillance, and political level through Commissioner’s visits, bilateral meetings and fact-finding missions. Some of the changes in Semester proceeding have been particularly useful in creating space for institutional ownership. For instance, the possibility given to national authorities to comment on drafts of the Country Report ensures factual and analytical agreement between the Commission and government (NATMIN02), which is important for political ownership. Also, fact-finding missions, when attended by high-ranked officials, offer national authorities the space to express their policy priorities. Their reflections help the Commission in fine-tuning CSRs to resonate with national agendas and ultimately create ownership. National officials agreed that direct contacts with the Commission via fact-finding missions supported ownership (NATMIN01, NATMIN02). They offer a chance to challenge Commission’s analysis and provide alternative perspectives, and the regular flow of information helps in building trust. In those cases, however, ESOs only serve as organizers of such visits, but do not act as mediators.

This is not to say that the Country Reports and CSRs are completely politicized and not evidence-based (grounded in economic analysis). It only shows that the Commission does not operate in a political vacuum. It considers the prospect of their advice being taken into consideration and how CSRs will resonate domestically. The Commission is explicitly employing an ownership strategy to avoid political rifts with member states when possible and chooses its battles carefully. One high-ranked SECGEN official describes the strategy: ‘CSRs are not naïve and they do take into account the political dimension. We are concerned about the follow-up on recommendations and ownership in their regard’ (SECGEN01). Political considerations thus have an influence when sensitive issues are discussed, however much less on the substance, which remains evidence-based, but more on the wording of recommendations so that it is not confrontational: ‘We still try to recommend things, but not in a frictional way, which is why we pay attention to the wording of the recommendations’ (DGEMPL09).

7. Conclusion

This paper studied the throughput legitimacy of the Semester. It theorized on the role of ESOs – Commission staff which were deployed to Representations of the Commission to Member States. Two pathways were developed for increasing throughput legitimacy. One was top-down in which ESOs transmit and communicate Semester throughputs to national authorities, social partners, civil society and interest groups to foster cognitive ownership. The other was bottom-up in which ESOs facilitate inclusive stakeholder participation in the preparatory stages of the Semester to build political and institutional ownership. The findings give a variegated picture of ESOs contribution to greater throughput legitimacy of the Semester. On the one hand, ESOs’ presence on the ground proves somewhat helpful in creating cognitive ownership. Domestic actors have largely been europeanized in the Semester discourse and practices. Building cognitive ownership, however, has its limits, especially when EU initiatives are incompatible with domestic agendas or touch upon controversial topics. Also, wider engagement of the public with the Semester and thus broader cognitive ownership currently seems untenable. On the other hand, ESOs crucial function is to build bridges and broker between domestic actors and the Commission whilst providing valuable intelligence to the Commission on political/policy trends in the country. They are mostly left without substantive influence on the ‘meat’ of the documents prepared during the Semester. This blocks ESO’s attempts at channelling upstream stakeholders’ policy suggestions, which creates the impression that ESOs alone are less likely to improve institutional ownership, albeit the high level of Semester’s inclusiveness. They do, however, influence the phrasing in Country Reports, which serves both the political purposes of the Commission, and domestic actors who feel greater political ownership. The findings indicate that the Commission has lately become more open to policy dialogue with Member States. Intensified dialogue with the Commission allows Member States to influence the formulations of Country Reports and CSRs. ESOs are extremely helpful in that regard as they are informed on national sensitivities and often help the Commission identify formulations in Country Reports which could run against the objective of increasing political ownership.

The implications of this research for policy are threefold. First, ESOs showcase how soft governance can increase the legitimacy of external engagement with Member States. This finding is pertinent even beyond the Semester as is goes to show that mechanisms of persuasion and social pressure can make governments and stakeholders amenable to requests – which can uplift EU legitimacy (cf. Schlipphak & Treib, Citation2017). Second, ESOs’ role makes the case for the institutionalization of network governance between domestic actors and Commission officials. From the perspective of the Commission, it would be wise to formalize stakeholder involvement. A higher profile of these meetings, greater publicity and inclusiveness would contribute to a positive image of the Commission within the civil society. Building coalitions from below might prevent blame being shifted to Brussels as the Commission would have domestic allies debunking such attempts. Third, the Commission should seriously rethink the way ESOs’ human resources are employed on the ground. Arguably, more easily accessible assistance to all ESOs who request help and more flexibility and autonomy in appearing on the record would improve ESOs’ effectiveness.

This research aspires to prompt interest for new research agendas. For instance, it is worth studying the modernization of Commission Representations and how their functional diversification influences policy transfer, public perceptions of the Commission and Commission’s involvement in domestic policy-making. This paper confirmed that Representations outgrew strictly communicative functions and now perform substantive political and policy analysis. Another interesting direction would be to study multi-level administrative networks created within the Semester and implications this intensification of relations has on throughput legitimacy. As demonstrated, fact-finding missions create networks between Country Teams, civil servants and high-level officials from both sides. It is therefore worthwhile studying the Commission’s quest for ownership beyond the specific focus on ESOs. Finally, further research is needed to elucidate the Commission’s political role and to what extent the Semester process is politicized.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Markus Haverland, Uwe Puetter, Peter Starke, Jonathan Zeitlin and the anonymous referees for their very helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper.

ORCID

Mario Munta http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7613-4748

Notes

1 The focus in Semester’s throughput legitimacy is only on Country Reports and CSRs. National Reform Programmes and Stability/Convergence Programmes are government-produced document and therefore better suited for studying relationships between governments and domestic actors. Since the paper concentrates on Commission’s attempts to foster throughput legitimacy, it is more relevant to study EU-produced documents targeting Member States.

2 ESOs from Bulgaria, United Kingdom, Sweden, Luxemburg and Romania did not respond to repeated interview requests. Greece did not participate in the Semester. All interviewees insisted not to be cited on country-specific policy details.

References

- Barrett, G. (2018). European economic governance: Deficient in democratic legitimacy? Journal of European Integration, 40(3), 249–264.

- Bauer, M. W., & Becker, S. (2014). The unexpected winner of the crisis: The European Commission’s strengthened role in economic governance. Journal of European Integration, 36(3), 213–229.

- Bekker, S. (2015). European socioeconomic governance in action: coordinating social policies in the third European Semester. European Social Observatory Paper Series, No. 19, January 2015.

- Bekker, Sonja, & Klosse, Saskia. (2014). The changing legal context of employment policy coordination. European Labour Law Journal, 5(1), 6–17.

- Berlo, D. (1960). The process of communication: An introduction to theory and practice. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

- Büchs, M. (2007). New governance in European social policy: The open method of coordination. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Coman, R. (2017). The legitimacy gaps of the European Semester: Who decides, what and how. L’Europe en Formation, 383–384(2), 47–60.

- Coman, R., & Ponjaert, F. (2016). From one semester to the next: Towards the hybridization of new modes of governance in EU policy. Cahiers du CEVIPOL Brussels Working Papers, 5/2016.

- Crum, B. (2018). Parliamentary accountability in multilevel governance: What role for parliaments in post-crisis EU economic governance? Journal of European Public Policy, 25(2), 268–286.

- Dehousse, R. (2016). Has the European Union moved towards soft governance? Comparative European Politics, 14(1), 20–35.

- Dinan, D. (2016). Governance and institutions: A more political commission. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 54(Annual Review), 101–116.

- Dunlop, C. A., & Radaelli, C. M. (2016). Policy learning in the Eurozone crisis: Modes, power and functionality. Policy Sciences, 49, 107–124.

- Eurofound. (2018). Involvement of the national social partners in the European Semester 2017: Social dialogue practices. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- European Anti-Poverty Network. (2016). Toolkit on engaging with Europe 2020 and the European Semester. Country Reports, Country Specific Recommendations, National Reform Programmes 2016. Brussels, March 2016.

- European Commission. (2015). Recommendation on steps towards completing the economic and monetary union. COM(2015) 600 final, 21 October. Brussels: EC. Retrieved from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52015DC0600.

- European Commission. (2017). Reflection paper on the deepening of the economic and monetary union. COM(2017) 291, 31 May, Brussels: EC. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/publications/reflection-paper-deepening-economic-and-monetary-union_en.

- Fromage, Diane, & van den Brink, Ton. (2018). Democratic legitimation of EU economic governance: Challenges and opportunities for European Legislatures. Journal of European Integration, 40(3), 235–248.

- Gomez, R. (2015). The economy strikes back: Support for the EU during the great recession. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 53(3), 577–592.

- Hallerberg, M., Marzinotto, B., & Wolff, B. G. (2012). On the effectiveness and legitimacy of EU economic policies. Brussels: Bruegel Institute.

- Hallerberg, M., Marzinotto, B., & Wolff, B. G. (2018). Explaining the evolving role of national parliaments under the European Semester. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(2), 250–267.

- Hodson, D. (2013). The little engine that wouldn’t: Supranational entrepreneurship and the Barroso commission. Journal of European Integration, 35(3), 301–314.

- Iusmen, I., & Boswell, J. (2017). The dilemmas of pursuing ‘throughput legitimacy’ through participatory mechanisms. West European Politics, 40(2), 459–478.

- Peterson, J. (2017). Juncker’s political European Commission and an EU in crisis. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 55(2), 349–367.

- Piattoni, S. (2015). The European Union. Letigimating values, democratic principles, and institutional architectures. In S. Piattoni (Ed.), The European Union: Democratic Principles and institutional Architectures in times of crisis (pp. 4–26). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Polyakova, A., & Fligstein, N. (2016). Is European integration causing Europe to become more nationalist? Evidence from the 2007–9 financial crisis. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(1), 60–83.

- Sabato, S., & Vanhercke, B. (2017). Listened to, but not heard? Social partners’ multilevel involvement in the European Semester. OSE Paper Series, Research Paper No. 35, Brussels: European Social Observatory.

- Savage, D. J., & Verdun, A. (2016). Strengthening the European Commission’s budgetary and economic surveillance capacity since Greece and the euro area crisis: A study of five directorates-general. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(1), 101–118.

- Scharpf, F. (1999). Governing in Europe: Effective and democratic? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schlipphak, B., & Treib, O. (2017). Playing the blame game on Brussels: The domestic political effects of EU interventions against democratic backsliding. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(3), 352–365.

- Schmidt, V. A. (2004). The European Union: Democratic legitimacy in a regional State?* JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 42(5), 975–997.

- Schmidt, V. A. (2013). Democracy and legitimacy in the European Union Revisited: Input, output and throughput. Political Studies, 61, 2–22.

- Vanheuverzwijn, P., & Crespy, A. (2018). Macro-economic coordination and elusive ownership in the European Union. Public Administration, 96(3), 578–593.

- Weiler, J. H. H. (2012). In the Face of crisis: Input legitimacy, output legitimacy and the political Messianism of European Integration. Journal of European Integration, 34(7), 825–841.

- Zeitlin, J., & Vanhercke, B. (2014). Socializing the European Semester? Economic governance and social policy coordination in Europe 2020. Stockholm: Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies. SIEPS) 2014:7, December 2014.