ABSTRACT

In recent years, there have been numerous academic and policy debates on the delivery mechanisms of European Union (EU) funds in member states. Studies focused on issues arising, for instance, during the management and implementation of EU aid at the local level but devoted less attention to the economic and institutional impact of EU funds. To what extent do EU funds act as drivers of socio-economic development and institutional change? Theoretically, this paper contributes to debates about economic convergence and the institutional spillover effects generated by EU aid across national and local settings. Empirically, the paper evaluates the impact of EU aid in Bulgaria and Romania after a decade of EU membership. Firstly, the paper examines a mix of quantitative indicators and secondary sources on the socio-economic impact of EU funds in the two countries. Secondly, using original qualitative evidence, the paper assesses the spillover effects of EU aid on domestic institutions and stakeholders, policies and practices. Finally, the paper provides an analysis of the unintended domestic consequences triggered by EU funds. It contributes to growing debates on the impact of European aid and suggests potential avenues for policy development and for further academic research in this area.

1. Introduction

Accessing large amounts of funding has often been seen as one of the main benefits of European Union (EU) accession. This has been a primary driver motivating candidate countries to comply with demands from Brussels. Given the level of national and intra-national disparities affecting Bulgarian and Romanian regions, as compared to their Western counterparts, it was hoped that European funds would contribute towards reducing such development gaps. Following 2007, Bulgaria and Romania were entitled to access large sums of money. These derived from Structural Funds, direct payments in agriculture, rural development and fisheries funding among others. Despite this, the first years of EU funding implementation has been marred by several difficulties ranging from weak state and administrative capacity for EU aid implementation, to legal gaps (e.g. public procurement) and politicisation. At the same time, questions have been raised on the effective use of these funds and the impact that these may have had on national and local developments in the two countries during their first decade of membership.

This paper addresses the following questions: What has been the economic impact of EU funds in Bulgaria and Romania? To what extent has the management and implementation of external assistance had any spillover effects, from the European to the national and local level, in terms of institutions, domestic policies and practices in the two countries? Both questions provide two distinct areas of inquiry, in line with the remit of this Special Issue. Firstly, a mix of quantitative and secondary evidence will be examined on the way in which European funds have been used by governments in Sofia and Bucharest and what socio-economic impact have these had on the two countries. This tackles the conceptual issue of convergence and whether EU funding transfers have had any positive effects on the economies of the two countries. Secondly, using original and in-depth qualitative evidence, the paper assesses potential spillover effects and the impact of European funding may have had on the configurations and workings of domestic institutions, policies or practices. Finally, apart from weighting the effects of EU funds implementation, the paper provides an analysis of the unintended domestic consequences triggered by the implementation of EU funds in both countries. The paper draws on a comparative research design which used several case studies. Fieldwork was conducted in Bulgaria, Romania and Brussels during 2013–2015. The interviewed stakeholders were based in the different institutions managing EU funds in Bulgaria and Romania at both the central and local level. Insights were drawn from EU funds administrators from Managing Authorities/Intermediate Bodies, politicians, local experts and civil society representatives. The qualitative data was analysed and triangulated with several secondary sources such as academic papers, policy evaluations and civil society reports. Overall, the paper contributes to growing discussions on the impact of European external assistance on its member states.

In line with debates in the literature, it is was initially expected that European funds would have a largely positive impact on national and local development in the two countries. Nevertheless, the analysis has shown that the impact of European aid in the two countries has been mediated by different external and domestic factors. With regard to economic convergence, it is still difficult to qualify whether or not EU funds have led to an increase in national GDP and per capita (PPS). This is despite the fact that EU aid has represented the main source of internal investment buffering, in both countries, the effects of the 2008 economic and financial crisis. In terms of spillover effects, there is some evidence of learning and adaptation of EU strategic frameworks, tools and templates by domestic local institutions. Nevertheless, there have been several unforeseen consequences derived from the use of EU funds (e.g. it provided national and local politicians with opportunities to shift the focus on misusing domestic budgets). Overall, it is argued that EU transfers have had an ambivalent effect on the national economies of the two countries and a positive, yet limited, impact on domestic institutions, policies and practices.

The remainder of the paper is divided in the following manner. The second section discusses the main concepts of convergence and spillover effects, whilst reviewing them in line with the literature. The third section outlines the allocation and use of EU funds in both countries whilst examining the socio-economic impact these have had against evidence from specialised studies in this area. The fourth section provides evidence on the spillover effects and the potential for institutional diffusion and learning from the adaptation to Europeanised institutional systems developed to manage EU aid. Section five discusses some of the unintended consequences generated by the use of EU external assistance in the two countries. The final section brings together core reflections derived from the analysis and concludes by suggesting areas for further academic inquiry.

2. Convergence and spillover effects – insights from the literature

Economists and regional geographers have been very interested in studying the effects of European transfers on national and regional/local economies. In this respect, academic studies looking at Cohesion Policy (CP) and Structural Funds (SF) have reached mixed results (Beugelsdijk & Eijffinger, Citation2005; Boldrin & Canova, Citation2001; Bouvet & Dall’erba, Citation2010). Several studies have been critical on the long-term impact and effectiveness that SF have on national economies (Ederveen, Groot, & Nahuis, Citation2006), given for instance, the excessive focus on infrastructure development (Rodríguez-Pose & Fratesi, Citation2004). By contrast, many of the models often used by EU institutions, time and again find positive effects of European funds on national Gross Domestic Products (GDP) (Bradley, Gács, Kangur, & Lubenets, Citation2005; in ‘t Veld & Varga, Citation2010). As a result, the issue of economic convergence, as triggered by European investments, remains subject to further scrutiny (see Dall’Erba & Fang, Citation2017 for a wide review of the current literature). Within the debate, there are various other perspectives. On the one hand, some have argued that EU funding investments have potentially mitigated the effects of the recent financial crisis (Becker, Egger, & von Ehrlich, Citation2018). On the other hand, due to domestic conditions such as the quality of government or institutions, more developed regions might benefit more from the redistribution of EU funds (Crescenzi & Giua, Citation2016; Rodríguez-Pose & Garcilazo, Citation2015).

In parallel, there have been several discussions about the potential spillover effects that EU funding implementation triggers at the local level. These have widely been linked to discussions on Europeanisation and multi-level governance, and how processes of EU policy enforcement facilitate such developments and trigger domestic responses (Bache, Andreou, Atanasova, & Tomsic, Citation2011; Benz & Eberlein, Citation1999; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2001; Marks, Citation1996). More specifically, academics have sought to assess the impact that EU funds implementation may have on the triad of domestic institutions, procedures and policies in both old and new member states (Dąbrowski, Bachtler, & Bafoil, Citation2014; Paraskevopoulos, Getimis, & Rees, Citation2006; Paraskevopoulos & Leonardi, Citation2004). Specifically, some policy-oriented studies have examined the potential spillover effects that EU funds have as ‘agents of change’ (EPRC and METIS, Citation2009; Polverari, Ferry, & Bachtler, Citation2017). In other words, there is a growing literature that seeks to understand the indirect effects EU funds have on domestic users and in particular those central, regional or local institutions in charge with strategic directions and policy enforcement.

There is, more and more, evidence about the influence of EU funds on domestic capacity building. However, it has often been argued that central governments are the main beneficiaries of such processes (Bache & Andreou, Citation2013; Bailey & De Propris, Citation2002; Hughes, Sasse, & Gordon, Citation2004). Moreover, due to the application of the partnership principle, EU funding processes actively involve several stakeholders such as civil society (Batory & Cartwright, Citation2012) or other sub-national actors (Dąbrowski, Citation2013). Overall, the literature has sought to examine the potential ‘added value’ of European funds (Mairate, Citation2006). This goes beyond the immediate and long-term effects that EU funds have on domestic economic development. It refers to the added value produced by the use of EU funds in terms of policy (e.g. innovation in policy, leverage of domestic resources), implementation (e.g. evaluation culture, audit/control), learning (e.g. exchanging of experience) and visibility (increased participation of local actors) (Mairate, Citation2006, p. 168; Polverari et al., Citation2017, p. 13). For instance, EU funding is largely credited for allowing states to adopt a more strategic and long-term approach regarding public expenditure, via the creation of multi-annual frameworks and strategic frameworks. This equally applies to more developed states such as Austria and Germany (Balsiger, Citation2016). Drawing on case studies from less and more developed regions, Bachtler et al. found that exposure to expertise through exchanges has been beneficial for local capacity development in regions from Greece, Portugal and Spain (Citation2013, p. 123). Finally, in new member states, the use of EU funds has contributed to the development of monitoring and reporting procedures, as well as for adopting international evaluation standards (Knott, Citation2007; Olejniczak, Citation2013).

There is, thus, some evidence of the medium to long-term effects that EU aid implementation has on institutions and practices within member states. It is against this background, that this paper evaluates the impact of EU funds on Bulgaria and Romania and the extent to which these countries benefited, or not, from these during their first decade of membership.Footnote1 The following section contextualises this by highlighting evidence on the allocation and use of EU aid in the two countries and by assessing evidence of potential convergence effects.

3. Allocations and use of European funds in Bulgaria and Romania – any signs of convergence?

During their first decade of membership, Bulgaria and Romania have been net beneficiaries of EU funding, namely they have received substantially more resources than they have contributed to the EU budget. For instance, during 2007–2016, Romania had received approximately 40.5 billion EUR from the EU (including from pre-accession funds) and contributed to Brussels’ common budget with 13.6 billion EUR.Footnote2 Therefore, the remainder of the funding was invested in the country under the form of different funds. outlines the data for the main EU funding received during the two implementation periods of 2007–2013 and 2014–2020. It highlights that during these periods Bulgaria will have had access to 31 billion EUR whilst Romania could obtain 85 billion EUR in total. In terms of the actual spending, by March 2017, Bulgaria managed to absorb 13.3 billion into its economy whilst Romania absorbed 31.9 billion EUR. Throughout 2007–13, more than 11 thousand projects were funded in Bulgaria and 15 thousand in Romania from Structural Funds.Footnote3 These varied from small to large infrastructure development projects to research projects or educational and social investments. Moreover, several thousand peasants and farmers benefited from rural investments or direct payments in agriculture.

Table 1. Post-accession European funding implementation in Bulgaria and Romania.

In general, the implementation of EU funds faced several difficulties ranging from the weak administrative capacity of state institutions to internal regulatory barriers or deficiencies in applying public procurement law. In this respect, there have been many issues in both countries with regard to the low capacity of institutions managing the funding to establish and coordinate the process, engage with EU funds final beneficiaries or ensure the political stability and commitment required for the management and implementation of the funds (Paliova & Lybek, Citation2014; Zaman & Georgescu, Citation2009). Moreover, despite both countries lacking experience in terms of dealing with EU funds, some differences have emerged between the two countries in terms of SCF absorption, especially given the higher level of political support granted to the process by authorities in Sofia as opposed to Bucharest (Surubaru, Citation2017a). Finally, a considerable number of projects were subject to irregularities, unveiled following inspections and controls from national or European auditors. Furthermore, several projects were plagued by a potentially fraudulent use of EU resources and faced legal investigations. Problematic projects were often sanctioned through financial corrections affecting national and local budgets.

In spite of these raw figures, the question remains to what extent have EU funds contributed to a convergence process and reduced the development gaps between Bulgaria and Romania and other EU member states? This question can be examined by looking at several important indicators. Firstly, it must be stressed that EU funding became one of the largest sources of public investment in both countries. In other words, a large amount of public investments were carried out using EU funds. For instance, for 2011–13, the European Commission asserts that approximately 70% of total public investments in Bulgaria and 40% in Romania were funded via Structural Funds (EC, Citation2014, p. 156). Secondly, it is widely accepted by both national politicians and policy-makers in Brussels that EU funding has acted as a buffer and has minimised the effects of the financial crisis, maintaining levels of investment (e.g. gross fixed capital formation) which would have fallen with 50% in these countries (EC, Citation2014, p. XV).

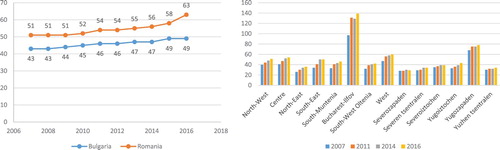

Secondly, a different way for assessing potential convergence effects is to examine the pre- and post-accession levels of economic growth in both countries. The most widely used indicator is the Gross Domestic Product per capita PPS (purchasing power standards), with the EU-28 average being benchmarked at 100 percentage points. Eurostat data (see ) outlines that in both countries there has been an increase in GDP PPS per capita since their accession, with Bulgaria seeing a 6 percentage point increase whilst Romania benefited from double that amount. At the regional level (NUTS 2) the situation is much more complex given the vast inter- and intra-regional disparities affecting both countries (Benedek, Citation2015; Yanakiev, Citation2010). Some regions have experienced a higher increase towards the EU GPD per capita (PPS) average (see ). This is largely the case for the capital regions of Yugozapaden and Bucharest-Ilfov. A moderate growth level has been observed in other regions as well (e.g. Yugoiztochen, West, Centre and North-West Romania). Finally, there are still several regions, lagging very much behind the EU average, in which growth levels have been very slow (e.g. Severozapaden, Severen tsentralen and Yuzhen centralen in Bulgaria and North-East in Romania).

Figure 1. National and regional (NUTS2) Gross Domestic Product (PPS) evolution (EU-28 = 100).

Source: Authors’ compilation using Eurostat data.

Figure 2. Geography of expenditure (EUR million allocated and spent per region) in Bulgarian and Romanian NUTS 2 regions during 2007–2013 (Structural Funds only).

Source: Author’s compilation using European Commission data on EU payments, cumulative allocations to selected projects and expenditure at NUTS2, available at: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/policy/evaluations/data-for-research/.

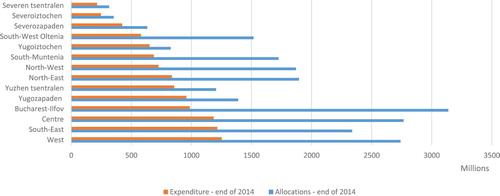

Several interesting aspects can be noted in relation to the geography of expenditure for SF during the 2007–2013 period.Footnote4 First, the concentration of funding (overall allocations) is highest in the capital regions as compared to all other regions. This could be due to the fact that several large infrastructure projects are either funded there (e.g. Sofia metro) or are being managed from there for the entire country (e.g. Romanian Ministry of Transport managing highway development infrastructure for the whole country). Second, in terms of actual expenditure, three Romanian regions (West, South-East and Centre) managed to spend more funding than the capital region of Bucharest-Ilfov. In Bulgaria, however, the capital region of Yugozapaden has been the first in spending EU funding.Footnote5

Another way to qualify the potential impact of EU funding on national and regional convergence is to assess the evidence advanced by the policy and academic literature on the topic, in particular those studies using economic modelling. Similarly to the wider academic literature on EU funds impact, the results of these studies are mixed. On the one hand, several studies argue that EU funds, in particular Structural Funds, bring consistent returns on investments. Policy studies using various economic models find a positive impact of EU funds on GDP growth in both countries. Studies using the HERMIN model estimated that, in the short run, Bulgaria will benefit from a GDP increase of 3.7% and Romania slightly below 3% (EC, Citation2009). Whereas, in the long-run, both countries will benefit from a GDP increase of 5% thanks to EU funds injections during 2007–2020 (EC, Citation2009, p. 6). Bradley (Citation2006, p. 196) estimated, using cumulative multipliers,Footnote6 that Romania’s GDP will increase by 2020, with 1.8% due to Structural Funds. Lastly, an analysis, looking at regional GDP growth (NUTS 2) using RHOMOLO, simulations found that, by 2023, two Romanian regions (Centre and West) and one Bulgarian region (Yugoiztochen) will be among the top ten regions in Europe where GDP PPS is expected to increase, as a result of using structural and rural development funds (EC, Citation2016, p. 9).

On the other hand, independent studies seem to obtain different and more cautious results. On Bulgaria, Paliova and Lybek have estimated that if the country fully absorbs these funds its GDP may increase with 3.6% by 2015 and with 2.1%, in case the EU funds are not fully spent (Citation2014, p. 22). Other studies, however, have found fewer positive effects. Танчев and Терзиев (Citation2018) suggest that during 2008–2014 EU funds have managed to produce only a 1% increase in national GDP. Finally, Durova found that, in the short term, EU funds did not have any effects on economic growth, employment or unemployment in Bulgaria (2018, p. 34). On Romania, Dobre (Citation2014) found a strong correlation between EU agricultural and structural funds and national economic growth. By contrast, Lungu (Citation2013) has argued that EU funds have had a modest impact on Romanian economic growth during 2007–2012, ranging from 0.5 to o.8% of GDP. The author stressed that, in a best case scenario and up to 2020, a 1.63% in GDP growth could be generated by using EU funds (Lungu, Citation2013, p. 12).

Overall, quantifying the impact of EU funds on macro-economic developments in both countries has produced ambivalent results. There are other factors that could potentially moderate the impact of EU transfers in this area. Apart from the low levels of absorption, in the first years of implementation, the effects of the economic crisis have potentially reduced the impact of the funding. However, it is more and more acknowledged that, for instance, Structural Funds acted as buffer against the effects of the financial crisis in new member states (Jacoby, Citation2014). Co-financing EU funded projects has been a budgetary burden for the governments of both countries and led to reductions in other national budgetary lines (Kamps, Leiner-Killinger, & Martin, Citation2009). Finally, against the background of the Eurozone crisis, the European Commission has strengthened its approach regarding economic governance. As a result, Brussels has been much stricter in enforcing the excessive deficit procedure of the Stability and Growth Pact, especially in new member states (Leaman, Citation2012) and threatened states with EU funds suspension in order to correct deficits (Coman, Citation2018). Consequently, limits to public sector borrowing and the effects of the crisis on state budgets has affected the ability of governments in Sofia and Bucharest to co-finance and contract EU funding. Apart from the potential macro-economic impact of EU funds, in Bulgaria and Romania, there are other softer effects which manifested at the institutional level. These are examined in more depth in the following section.

4. Spillovers and the institutional impact of EU aid

Accessing EU funds does not attract only economic effects. As outlined in the literature dealing with institutional effects and spillovers (for a review see Polverari et al., Citation2017), processing EU aid entails other indirect effects. During their first decade of membership, Bulgaria and Romania have engaged in two multi-annual periods of EU funds implementation 2007–2013 and 2014–2020. The effects of the 2007–13 management and implementation period are slowly becoming more visible. For this paper, these were captured through interviews with key stakeholders involved in the process in both countries and triangulated with the results of similar studies. Overall, there are several areas, identified from the research, as being substantive in terms of institutional impact: (1) templates for development, (2) domestic administrative capacity developments, (3) cooperation and partnership, (4) project management spillovers, (5) reporting and evaluation culture, and finally, (6) perceptions regarding public spending and accountability. Although these are treated separately here, there are significant links between most of them.

Firstly, being involved in the strategic programming of EU aid, various stakeholders have acknowledged that this has offered both governments and local / regional actors a framework in which they can think and prioritise their development needs, also taking into account wider EU goals and strategies.Footnote7 This has allowed and motivated local and regional authorities to think of and develop local strategies and interventions tailored to their needs and to think of longer term priorities and the required interventions.Footnote8 This has potentially influenced the thinking on regional development, for instance, given the introduction and use of EU territorial development and urban strategies.Footnote9 In essence, this has led to an increase in the strategic capacity of both Bulgarian and Romanian governments and the visions for development of stakeholders at different levels.

Secondly, managing EU funding has promoted various domestic administrative capacity advances. Foremost, it must be stressed that the various institutions involved in the management and implementation of EU funds (e.g. Managing Authorities, Intermediate Bodies, Certifying and Payment Authorities, Audit Authorities) have, most of the time, been insulated within the local public administration. This allowed them to undertake a more thorough selection of staff and to offer higher wages and professional incentives. This attracted a large degree of interest among professional young people, in the two countries, and in time the institutions have become models (although often despised by some of their institutional peers) for the public administration of the two countries.Footnote10 This has equally been the case due their functionality and the importance they allocated to preserving institutional memory.Footnote11 It has been claimed that ministries hosting Managing Authorities have increased their performance and that at the local and regional level institutions and final beneficiaries (e.g. municipalities or NGOs) have benefited from EU funds to improve their administrative capacity.Footnote12 Furthermore, investments made through Structural Funds via the Operational Programmes for Administrative Capacity have targeted the development of areas such as the digitalisation of public administration or improving the human resources management systems of various central ministries.Footnote13 Overall, the institutional models developed through EU funds management and the specific investments discussed above have had some effects on domestic capacity building.

Thirdly, increased cooperation and the application of the partnership principleFootnote14 by different authorities has been one of the clearest spillover effects triggered by EU aid. In both Bulgaria and Romania, the application of this principle and the involvement of stakeholders in strategic processes has often been highly formalistic. Despite this, the management of EU aid has created new opportunities and new formal and informal channels of cooperation between and across different actors, such as local and national civil servants, local and national politicians, local and central NGOs.Footnote15 Often for the first time, local politicians met local civil servants and final beneficiaries (e.g. schools, hospitals) to discuss priorities and how to obtain or implement EU funded projects to achieve them. For instance, environmental non-governmental organisations have had some say in the proceedings of Monitoring Committees, tasked with formally supervising the implementation of EU funded programmes, on the impact of different projects. Consequently, it has been argued that these interactions have been beneficial for increasing the transparency of institutions dealing with EU aid and in promoting the voice of various stakeholders, which would have otherwise been excluded (e.g. Roma community) in the design and implementation process for EU funded interventions.Footnote16

Fourthly, one of the main spillover effects derived from managing different EU funds related to project management. In particular, the public administration, mainly the institutions managing the funding, have become accustomed to the project management cycle of public policy interventions. To this aim, EU approved management instruments and legally standardised procedures have been adopted.Footnote17 In addition, the public procurement laws and procedures of the two countries have been shaped by the need for complying with EU directives, as well as, by the experience of the authorities in this area, including through punitive measures (e.g. financial corrections). Furthermore, EU aid came with extensive provisions regarding financial irregularities and how to address them.Footnote18 All these areas were highly deficient in domestic ministries and in other public institutions. National authorities have become more aware of such aspects and have, to a certain extent, strengthened and clarified them in line with the experience drawn from the management of EU funding.

Fifthly, there are significant spillover effects regarding the development of a reporting and evaluation culture, in both countries, as a result of the need to formally assess the use and effects of EU funded interventions. Whereas, during the pre-accession period, Bulgarian and Romanian civil servants got accustomed to the vocabulary, role and structure of policy evaluations (Knott, Citation2007, p. 49), following accession, they have slowly started to carry out and understand the benefits of robust reporting and analysis. As stressed by a Bulgarian interviewee, it was ‘totally unimaginable’ before 2007 to allow external evaluators to appraise various funding programmes following their closure.Footnote19 Similarly, one Romanian interviewee highlighted the fact that the authorities are today much more aware about the purpose of studies and evaluations.Footnote20 The same can be said regarding the use of complex project and programme indicators for reporting. There is increasing evidence about the use of instruments such as territorial impact assessments or GIS data for assessing the impact of large infrastructure projects or preparing future national and local strategies in this area.Footnote21 All these could have a potential impact on the reporting and evaluation of domestic programmes, although evidence that local administrations are now widely using such tools is still limited.Footnote22

Last but not least, the management of EU funds has raised important questions about the accountability and transparency of public spending. After more than a decade of EU funds implementation, there has been a growing awareness among practitioners and among citizens that there are in fact two parallel systems: the EU funded one – more developed and prone to rigorous procedures and controls and the national public funding system – subject to systemic deficiencies and political interference.Footnote23 The use of EU funds have contributed to a potential change of perceptions and attitudes of citizens towards the accountability of national public funds spending. Visible improvements in neighbouring cities or local media pressure (e.g. on what is being done with EU funds) has raised discussions on this.Footnote24 As a result, there are debates on how to potentially limit political influence on national spending by harmonising EU and national selection criteria for state funded projects (World Bank, Citation2015). Moreover, it has been argued that even local politicians have realised the potential advantages of long-term priorities and the benefits that EU funds’ investments could have, even for their own political careers.Footnote25 Nevertheless, despite some advocacy for a unified public spending system (using the same principles and procedures for both EU funds and national funding) there are many difficulties facing a potential harmonisation process, ranging from a lack of political will to deficient legislation.Footnote26 The next chapter will dwell on some of these issues by examining the unforeseen and potentially negative consequences generated by EU funds transfers in the two countries under analysis.

5. Unintended consequences from the use and implementation of EU funds

Accessing European funding did not only entail only advantages. On the contrary, it can be argued that there were several unintended consequences resulting from the usage of extensive EU aid. Before outlining them, it must emphasised that these are varied in nature and cut across different sectors. What’s more, similarly to the above spillover effects, their impact is not yet clear or fully visible.

The first unintended consequence relates to the fact that many EU funded Operational Programmes have become de facto national strategies in certain areas. Two highly relevant examples can be given in this respect. Both the EU funded Regional Development Programme (ROP) and the Human Resources Development Operational Programme (HRD) have to a large extent, and in a gradual manner, substituted for the lack of functional governmental strategies in Sofia and Bucharest in these specific areas. For instance, given its efficiency and legitimacy, the Regional Development Operational Programme has become one of the main instruments for regional development in Romania.Footnote27 In Bulgaria, the Human Resources Development Operational Programme has become one of the main strategic and investment tools supporting approximately 75% of Bulgarian labour market policies and 98% of expenses for people with disabilities.Footnote28 Moreover, the programme equally contributed with significant funding to the deinstitutionalisation process for abandoned children (Ivanova & Bogdanov, Citation2013).

The second unintended consequence stems from the previous one. Although EU funding has to be additional, namely EU support must not replace public expenditure, in recent years, national public investments have decreased in Bulgaria, Poland and Romania. This is most probably a consequence of the financial crisis as well as given the considerable use of EU funds for public investments (Halasz, Citation2018). More importantly, domestic politicians and affiliated interest groups may have profited from a clear demarcation between EU funded programmes (much more rigorous and subject to external scrutiny) and national funded ones. This has potentially allowed them to further profit from and politicise state run programmes in similar areas (e.g. National Development Programme: Bulgaria 2020 and the Romanian National Programme for Local Development – PNDL).Footnote29

Furthermore, despite the fact that EU funds are subject to more controls and rigorous procedures, there are more and more discussions about clientelistic networks affiliated to key politicians which could have profited from their distribution. One of the primary mechanisms consisted in rigging public procurement contracts (Doroftei & Dimulescu, Citation2015; Fazekas, Chvalkovska, Skuhrovec, Tóth, & King, Citation2013; Stefanov, Yalamov, & Karaboev, Citation2015). Equally, the politicisation of senior management (in Managing Authorities/Intermediate Bodies) overseeing the selection EU funded projects and their implementation could have facilitated profiteering and embezzlement of EU aid (Hagemann, Citation2017; Surubaru, Citation2017b).

Thirdly, there were many reports of absurd EU funded projects (e.g. parks in rural villages), wasted resources (e.g. multifunctional business centres opened in areas with extremely low economic activity) or double financing of similar projects across different regions (e.g. training for unemployed people and upfront payments to fictional participants in order to reach required quotas for project participation) (CeRe, Citation2010).Footnote30 Similarly, an EU funds absorption ‘gold rush’ driven by the mirage of significant short-term profits has captured the attention of many societal actors. This manifested in different ways. For instance, many economic firms have specialised only in accessing and implementing EU funded projects, acting as intermediaries and cultivating practices of ‘body shopping’.Footnote31 Moreover, there have been reports of ‘civil society capture’. In the quest of making additional profits, many non-governmental organisations have given up their advocacy purposes and have, in essence, become ‘service providers’.Footnote32 This phenomenon has been pushed forward by the emergence of several new NGOs and foundations, often linked to politicians and other decision-makers, newly created in order to access EU funded projects.Footnote33 This entailed that many NGOs became dependent and often unwilling to criticise the funders (in this case the governmental institutions distributing EU aid).

The final unintended consequence relates to the area of agriculture and rural development. Bulgaria and Romania are among the countries with one of the highest share of active employment in agriculture and with one of the highest number of small scale farmers in the EU (Wegener et al., Citation2011). In 2015, both countries had the highest share of employment in agriculture from all EU countries, 25.8% in Romania and 18.2% in Bulgaria, mainly in subsistence and small scale farms.Footnote34 The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) of the EU has been often criticised by various stakeholders on the grounds of skewed support for large scale farmers and a disruption of agricultural production in the countries where it is implemented (Euractiv, Citation2017). The introduction of direct payments to farmers and different rural development funds, although welcomed by some, has potentially created a dependency of small and subsistence farmers on cultivating their land, as a condition for receiving EU payments. Moreover, direct payments in agriculture were criticised by activists for consolidating the position of big agricultural companies given their higher degree of land ownership (Euractiv, Citation2015). This is also in light of the weak voice of small local farmers in the two countries (Wegener et al., Citation2011). Finally, the phenomenon of ‘land grab’ and the expansion of agricultural production by Western agricultural companies buying arable land in the area could have been facilitated by the introduction of EU agricultural subsidies which could have long-term cultural implications for rural areas (Ciutacu, Chivu, & Vasile, Citation2017) or for the environment and biodiversity of the two countries (Dobrev, Popgeorgiev, & Plachiyski, Citation2016).

6. Conclusions

This paper has examined the question of European funds in Central and Eastern Europe, by focusing on the specific impact these had in two of the newest members of the European Union – Bulgaria and Romania. This was done by assessing a mix of largely quantitative indicators (e.g. impact of EU transfers on national and regional GDP growth) and qualitative evidence on the spillover effects derived from the institutional and procedural ecosystem of EU aid. The paper contributes to the literature in three ways. First, it has focused on two less known case studies (Bulgaria and Romania) drawing on original empirical evidence. Second, it developed an original framework for analysing institutional spillover effects which could be replicated and verified in other cases. Finally, it adds to the growing literature seeking to analyse issues of EU internal development in a critical manner.

In terms of background, apart from impact, the management of EU funds has attracted considerable attention from scholars. There have been several contributions stressing the importance of administrative and political factors and how these moderate the implementation process (Bachtler, Begg, Polverari, & Charles, Citation2013; Surubaru Citation2017a). In this sense, both factors could moderate not only the management of the funding, but on a longer term basis, also their impact (Incaltarau, Pascariu, & Surubaru, Citation2019). In this respect, more attentions is needed at the European level for developing domestic capacity and in taking into account the input and preferences of local political actors. Although some space has been dedicated to accounting for the internal factors mediating the management and implementation of EU funds in Sofia and Bucharest, the primary aim here has been to qualify the potential effects of European aid in the two countries. This was done by evaluating evidence of convergence, the institutional spillover effects of the funding and, a less scrutinised area, the unintended consequences derived from the use of EU aid at the domestic level.

With respect to convergence, the countries have benefited from considerable injections of EU funds, during their first decade of membership. This has been crucial in maintaining levels of public investment and acted as a buffer to the effects of the 2008 financial downturn. Notwithstanding, the quantitative evidence and secondary literature points to an ambivalent effect of EU funds transfers in terms of economic convergence. Although there has been a significant level of GDP growth (PPS / per capita), at both the central and regional level since accession, it is not clear whether EU funding transfers can account for this. Whilst policy studies forecast substantial GDP growth due to EU transfers (as high as 4.7% for Romania and 3.6% for Bulgaria), academic ones are more modest in their assessments (1–2.1% in Bulgaria and 0.5–1.6% in Romania), provided of course that certain macro-economic conditions are met. The evidence so far is, therefore, at best ambivalent. Although EU funding has had an impact on public investment (e.g. gross fixed capital formation) in the two countries and could, as a result of considerable transfers, have contributed to an increase in national GDP, other factors could equally have influenced internal economic growth (e.g. increase in domestic consumption or higher rates of tax collection).

The institutional effects of EU funding could, in the long-term, prove more valuable than their impact on national and regional GDP. Both Bulgaria and Romania have went through a steep learning curve in adopting and implementing institutions, principles and procedures related to EU funds implementation. The latter have contributed towards developing new visions and frameworks for domestic development, taking into account long-term priorities, through enhanced cooperation and by creating new areas of interaction between different societal stakeholders. Moreover, the institutions managing EU aid, although often insulated from the rest of the administration, could in the future provide a blueprint for administrative capacity developments and a model of public sector professionalisation. The latter objective is also targeted by specific investments and by the adoption of various EU approved project management principles and procedures, as well as by an increasing understanding of the importance of data and evidence for public policy development, enhanced by new principles reporting and evaluation. Finally, one potentially significant effect relates to an increasing awareness of the need for more accountability and transparency in the expenditure of domestic public funds. Unifying or harmonising procedures for EU and national funding, in order to limit arbitrary political interference could be, in the future, an important spillover effect. Finally, it must be underlined that these effects are present only in embryonic forms, in both countries, and do not apply globally to the wider public administration.

Such potential positive effects can be, however, outweighed by unexpected developments triggered by the use of EU funding in both countries. The fact that some EU funded programmes have become, de facto, national strategies in certain areas (e.g. human resources/regional development) might mean that national governments are eschewing their responsibilities in these areas. Moreover, a strong demarcation between EU funded investments and national funded ones, might allow local politicians to find ways to further profit from domestic public spending schemes. Also, EU funds have not remained untouched by various interest cartels and clientelistic networks in both countries. Added to this, there is the issue of wasted funding on absurd projects, irregularities and projects affected by fraud. In many cases, the funds spent on the latter was paid back to Brussels via financial corrections. Last but not least, EU aid may have indirectly contributed to a phenomenon of civil society capture or to land grabbing. Nevertheless, the question is to what extent would have these developed in the absence of EU aid or how much are these phenomena’s stimulated by it.

All things considered, it can be stressed that EU funds have had a relatively important, and often visible, impact on the economy of the two countries. This is especially the case for investments in public, social, educational and institutional infrastructure. However, at this point in time, their exact effects are ambivalent, difficult to qualify and to measure precisely. EU funded investments could prove valuable in the medium and long-term. It might take another decade of EU membership to draw a more refined conclusion on these aspects. Meanwhile, on the one hand, national and Brussels based administrators should take seek to improve the capacity of the institutions responsible for EU funding, with an eye towards simplifying and harmonising different areas of public spending. Politicians could try to provide more realistic, yet complex visions, for development in line with current challenges (demographic, automatisation). On the other hand, more research is needed in specifying the exact economic, social and institutional impact of the funding, at different geographical and thematic levels of analysis. Weighting the costs of EU aid (by also learning from the vast global literature on development aid) and understanding its impact, whether positive or negative, could drive a new research agenda in this area.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Cristian Nitoiu and two anonymous reviewers for the helpful comments received when drafting this article. Studio Europa and the Maastricht Working on Europe (MWOE) programme are kindly acknowledged for their support whilst finalising this article.

Notes

1 The literature also addresses the question of regional development and empowerment. Given the scope and limited space for this paper, this aspect will be treated elsewhere.

2 Romanian Ministry of Public Finance, available at https://media.hotnews.ro/media_server1/document-2017-01-3-21508496-0-fonduri.pdf, accessed September 2018.

3 These are composed of three funding streams: European Regional and Development Fund (ERDF), Cohesion Funds (CP) and European Social Fund (ESF). These are allocated to member states using a GDP per capita criteria and, therefore, favour countries with a GDP per capita (PPS) below the EU average (EU-28 = 100), and mostly to those countries below 75%. Bulgaria and Romania easily qualify for this aspect.

4 This data is only relevant for Structural Funds (ERDF and CF) and excludes ESF funding.

5 The data is valid for the end of 2014 and the expenditure for all regions is much higher currently.

6 Defined as:

A cumulative multiplier is defined as the cumulative percentage increase in the level of GDP from the beginning of European Cohesion Policy intervention to 2020 divided by the cumulative European Cohesion Policy funding injection (expressed as a percentage of GDP) (EC, Citation2009, p. 7).

7 Director General of Romanian Ministry, 6 March 2014; Romanian Expert #1, 18 March 2018.

8 EC Head of Unit #2, 16 October 2013; Romanian MA Programme Evaluations Officer #2, 12 March 2014.

9 Bulgarian Mayor #1, 5 June 2014; Director in the Romanian Regional Development Ministry, 31 May 2016.

10 EC Policy Officer for administrative capacity #1, 17 October 2013.

11 EC Head of Unit #2, 16 October 2013.

12 Director in Bulgarian Audit Authority, 31 May 2014; Deputy Director of Bulgarian Managing Authority #2, 30 April 2014; Director in Romanian North-East Regional Development Agency, 17 April 2014; Bulgarian Intermediate Body Representative #1, 22 May 2014.

13 EC Head of Sector #1, 16 October 2013.

14 The European Commission publicly defines this principle in the following manner:

Each programme is developed through a collective process involving authorities at European, regional and local level, social partners and organisations from civil society. This partnership applies to all stages of the programming process, from design, through management and implementation to monitoring and evaluation. This approach help ensure that action is adapted to local and regional needs and priorities, available at: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/EN/policy/how/principles/ (accessed September 2018).

15 Director in Romanian North-East Regional Development Agency, 17 April 2014; Bulgarian Mayor #1, 5 June 2014.

16 Bulgarian Civil Society Leader #3, 5 June 2014; Former Romanian EU funds minister, 16 May 2017.

17 Bulgarian Expert #1, 8 May 2014; EC Head of Sector #1, 16 October 2013.

18 Director in Romanian Audit Authority #1, 14 April 2014.

19 Bulgarian Expert #2, 19 May 2014.

20 Former Romanian EU funds minister, 16 May 2017.

21 Romanian MA Programme Evaluations Officer #3, 11 April 2014; Director in Romanian North-East Development Agency, 17 April 2014.

22 EC Head of Unit #2, 16 October 2013.

23 Head of Unit in Bulgarian Central Coordination Unit #1, 24 April 2014; Romanian Expert #1, 18 March 2014.

24 Representative of the Bulgarian National Association of Municipalities, 19 May 2014.

25 Director in Romanian North-East Regional Development Agency, 17 April 2014.

26 Former Director of Bulgarian Managing Authority #2, 16 May 2014; Head of Unit in Bulgarian Central Coordination Unit #1, 24 April 2014; Representative of Romanian Certifying Authority, 27 March 2014.

27 Romanian Expert #1, 18 March 2014; Director in Romanian Ministry of Regional Development, 10 May 2017.

28 Figures estimated by the Deputy Director of Bulgarian Managing Authority #2, 30 April 2014; Bulgarian Intermediate Body Representative #1, 22 May 2014.

29 Romanian Expert #1, 18 March 2014; Bulgarian Civil Society Leader #1, 21 May 2014; Bulgarian Civil Society Leader #3, 5 June 2014.

30 Permanent Representative #1, 18 October 2013; Romanian Expert #2, 11 April 2014; EC Head of Unit #2, 16 October 2013.

31 Director of Bulgarian Managing Authority #1, 30 April 2014.

32 Romanian Civil Society Leader #1, 9 April 2014; Bulgarian Civil Society Leader #1, 21 May 2014.

33 Bulgarian Expert #3, 19 May 2014; Former EC Head of Unit #1, 8 October 2014.

34 Eurostat data, available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Farmers_in_the_EU_-statistics, accessed October 2018.

References

- Танчев, С, & Терзиев, М. (2018). Еврофондовете и икономическият растеж в България [EU funds and economic growth in Bulgaria]. Списание “Икономическа мисъл” [Economic Thought], бр. 1/2018.

- Bache, I., & Andreou, G. (2013). Cohesion policy and multi-level governance in South East Europe. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Bache, I., Andreou, G., Atanasova, G., & Tomsic, D. (2011). Europeanization and multi-level governance in south-east Europe: The domestic impact of EU cohesion policy and pre-accession aid. Journal of European Public Policy, 18(1), 122–141. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2011.520884

- Bachtler, J., Begg, I., Polverari, L., & Charles, D. (2013). Evaluation of the main achievements of cohesion policy programmes and projects over the longer term in 15 selected regions (from 1989–1993 Programme Period to the Present (2011.CE.16.B.AT.015), Final Report to the European Commission (DG Regio), European Policies Research Centre, University of Strathclyde (Glasgow) and London School of Economics.

- Bailey, D., & De Propris, L. (2002). EU structural funds, regional Capabilities and enlargement: Towards multi-level governance? Journal of European Integration, 24(4), 303–324. doi: 10.1080/0703633022000038959

- Balsiger, J. (2016). Cohesion policy in the rich central regions. In L. Polverari & S. Piattoni (Eds.), Cohesion policy in the EU (pp. 268–285). Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Batory, A., & Cartwright, A. (2012). Monitoring committees in cohesion policy: Overseeing the distribution of structural funds in Hungary and Slovakia. Journal of European Integration, 34(4), 323–340. doi: 10.1080/07036337.2011.595486

- Becker, S. O., Egger, P. H., & von Ehrlich, M. (2018). Effects of EU Regional Policy: 1989–2013. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 69, 143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2017.12.001

- Benedek, J. (2015). Spatial differentiation and core-periphery structures in Romania. Eastern Journal of European Studies, 6(1), 49–63. doi: 10.1080/2040350X.2014.992130

- Benz, A., & Eberlein, B. (1999). The Europeanization of regional policies: Patterns of multi-level governance. Journal of European Public Policy, 6(2), 329–348. doi: 10.1080/135017699343748

- Beugelsdijk, M., & Eijffinger, S. C. W. (2005). The effectiveness of structural policy in the European Union: An empirical analysis for the EU-15 in 1995–2001. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 43(1), 37–51.

- Boldrin, M., & Canova, F. (2001). Inequality and convergence in Europe’s regions: Reconsidering European regional policies. Economic Policy, 16(32), 206–253. doi: 10.1111/1468-0327.00074

- Bouvet, F., & Dall’erba, S. (2010). European regional structural funds: How large is the influence of politics on the allocation process? JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 48(3), 501–528.

- Bradley, J. (2006). Evaluating the impact of European Union Cohesion policy in less-developed countries and regions. Regional Studies, 40(2), 189–200. doi: 10.1080/00343400600600512

- Bradley, J., Gács, J., Kangur, A., & Lubenets, N. (2005). HERMIN: A macro model framework for the study of cohesion and transition. In J. Bradley, G. Petrakos, & J. Traistaru (Eds.), Integration, growth and cohesion in an enlarged European Union (pp. 207–241). New York, NY: Springer.

- CeRe. (2010). ‘112 pentru Fonduri Structurale “100 de sesizări”’ [112 for Structural Funds ‘100 complaints’]. Report of the Romanian Coalition of NGO’s for Structural Funds. Bucharest: Centrul de Resurse pentru participare publică.

- Ciutacu, C., Chivu, L., & Vasile, A. J. (2017). Land grabbing: A review of extent and possible consequences in Romania. Land Use Policy, 62, 143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.01.001

- Coman, R. (2018). How have EU “fire-fighters” sought to douse the flames of the Eurozone’s fast- and slow-burning crises? The 2013 structural funds reform. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 20(3), 540–554. doi: 10.1177/1369148118768188

- Crescenzi, R., & Giua, M. (2016). The EU Cohesion policy in context: Does a bottom-up approach work in all regions? Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 48(11), 2340–2357. doi: 10.1177/0308518X16658291

- Dąbrowski, M. (2013). Europeanizing sub-national governance: Partnership in the implementation of European Union structural funds in Poland. Regional Studies, 47(8), 1363–1374. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2011.628931

- Dąbrowski, M., Bachtler, J., & Bafoil, F. (2014). Challenges of multi-level governance and partnership: Drawing lessons from European Union cohesion policy. European Urban and Regional Studies, 21(4), 355–363. doi: 10.1177/0969776414533020

- Dall’Erba, S., & Fang, F. (2017). Meta-analysis of the impact of European Union Structural funds on regional growth. Regional Studies, 51(6), 822–832. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2015.1100285

- Dobre, A. S. (2014). The impact of EU funds on Romanian economy. Journal of Financial and Monetary Economics, 1(1), 38–48.

- Dobrev, V., Popgeorgiev, G., & Plachiyski, D. (2016). Effects of the common agricultural policy on the coverage of grassland habitats in Besaparski Ridove special protection area (Natura 2000), Southern Bulgaria. Acta Zoologica Bulgarica, 66(Suppl. 5), 147–155.

- Doroftei, M., & Dimulescu, V. (2015). Corruption risks in the Romanian infrastructure sector. In A. Mungiu-Pippidi (Ed.), Government favouritism in Europe. The anticorruption report – Volume 3 (pp. 19–35). Opladen: Barbara Budrich.

- Ederveen, S., Groot, H. L. F., & Nahuis, R. (2006). Fertile soil for structural funds? A panel data analysis of the conditional effectiveness of European cohesion policy. Kyklos, 59(1), 17–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6435.2006.00318.x

- Euractiv. (2015). Dosar Political Agricolă Comună. Prima mare reformă din ultimii zece ani. Retrieved from https://www.euractiv.ro/agricultura/dosar-politica-agricola-comuna-prima-mare-reforma-din-ultimii-zece-ani-1006.

- Euractiv. (2017). EU agricultural policy incoherent and outdated – report. by Samuel White. Retrieved from https://www.euractiv.com/section/agriculture-food/news/eu-agricultural-policy-incoherent-and-outdated-report/.

- European Commission. (2009). A cross-country impact assessment of EU cohesion policy applying the cohesion system of HERMIN models. By Zuzana Gáková, Dalia Grigonytė and Philippe Monfort. Working Papers of the Directorate General for Regional Policy, n° 01.

- European Commission. (2014). Investment for jobs and growth. Promoting development and good governance in EU regions and cities: Sixth report on economic, social and territorial cohesion. Brussels: DG Regional and Urban Policy.

- European Commission. (2016). The impact of cohesion policy 2007–2013: Model simulations with RHOMOLO. Summary of Simulation Results. Work Package 14b. Directorate General for Regional policy and Joint Research Centre Seville.

- European Policies Research Centre (EPRC) and METIS. (2009). Ex-post evaluation of EU cohesion policy programmes 2000–2006 co-financed by the ERDF (Work Package No. 11: Management and Implementation Systems for Cohesion Policy. Final Report to the European Commission). Glasgow: EPRC.

- Fazekas, M., Chvalkovska, J., Skuhrovec, J., Tóth, I. J., & King, L. P. (2013). Are EU funds a corruption risk? The impact of EU funds on grand corruption in Central and Eastern Europe (Working Paper Series No. CRCB-WP/2013:03). Budapest: Corruption Research Center.

- Hagemann, C. (2017). How politics matters for EU funds’ absorption problems – A fuzzy-set analysis. Journal of European Public Policy, 26, 188–206. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2017.1398774

- Halasz, A. (2018). Additionality of EU funds in central and eastern European countries – Recent developments. Retrieved from http://www.cohesify.eu/2018/01/23/additionality-of-eu-funds/.

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2001). Multi-level governance and European integration. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Hughes, J., Sasse, G., & Gordon, C. (2004). Conditionality and Compliance in the EU’s eastward enlargement: Regional policy and the reform of sub-national government. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 42(3), 523–551.

- Incaltarau, C., Pascariu, G., & Surubaru, N.-C. (2019). Evaluating the determinants of EU funds absorption across old and new member states – The role of administrative capacity and political governance. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies. doi:10.1111/jcms.12995.

- in ‘t Veld, J., & Varga, J. (2010). The potential impact of EU cohesion policy spending in the 2007–13 Programming Period: A Model-Based (European Economy – Economic Paper No. 422). Directorate General Economic and Monetary Affairs (DG ECFIN), European Commission. Retrieved from http://ideas.repec.org/p/euf/ecopap/0422.html.

- Ivanova, V., & Bogdanov, G. (2013). The deinstitutionalization of children in Bulgaria – The role of the EU. Social Policy & Administration, 47(2), 199–217. doi: 10.1111/spol.12015

- Jacoby, W. (2014). The EU factor in fat times and in lean: Did the EU amplify the boom and soften the bust? The EU factor in fat times and in lean. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 52(1), 52–70.

- Kamps, C., Leiner-Killinger, N., & Martin, R. (2009). The cyclical impact of EU cohesion policy in fast growing EU countries. Intereconomics, 44(1), 23–29. doi: 10.1007/s10272-009-0274-2

- Knott, J. (2007). The impact of the EU accession process on the establishment of evaluation capacity in Bulgaria and Romania. International Public Policy Review, 3(1), 49–68.

- Leaman, J. (2012). Weakening the fiscal state in Europe the European Union’s failure to halt the erosion of progressivity in direct taxation and its consequences. In A. Chitis, A. J. Menendez, & P. G. Teixeira (Eds.), The European Rescue of the European Union? The existential crisis of the European political project. ARENA Report No 3/12; RECON Report No 19 (pp. 157–193). Oslo: Arena Centre for European Studies.

- Lungu, L. (2013). The impact of EU funds on Romanian finances. Romanian Journal of European Affairs, 13(2), 5–27.

- Mairate, A. (2006). The ‘added value’ of European Union Cohesion policy. Regional Studies, 40(2), 167–177. doi: 10.1080/00343400600600496

- Marks, G. (1996). Exploring and explaining variation in EU cohesion policy. In L. Hooghe (Ed.), Cohesion policy and European integration: Building multi-level governance (pp. 388–422). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Olejniczak, K. (2013). Mechanisms shaping an evaluation system—A case study of Poland 1999–2010. Europe-Asia Studies, 65(8), 1642–1666. doi: 10.1080/09668136.2013.832996

- Paliova, I., & Lybek, T. (2014). Bulgaria S EU funds absorption: Maximizing the potential!. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

- Paraskevopoulos, C., Getimis, P., & Rees, N. (2006). Adapting to EU multi-level governance: Regional and environmental policies in cohesion and CEE countries. Aldershot, England; Burlington, VT: Routledge.

- Paraskevopoulos, C., & Leonardi, R. (2004). Introduction: Adaptational pressures and social learning in European regional policy – Cohesion (Greece, Ireland and Portugal) vs. CEE (Hungary, Poland) countries. Regional & Federal Studies, 14(3), 315–354. doi: 10.1080/1359756042000261342

- Polverari, L., Ferry, M., & Bachtler, J. (2017). The structural funds as “agents of change”: New forms of learning and implementation. IQ-Net Thematic Paper 40(2), European Policies Research Centre, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Fratesi, U. (2004). Between development and social policies: The impact of European structural funds in objective 1 regions. Regional Studies, 38(1), 97–113. doi: 10.1080/00343400310001632226

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Garcilazo, E. (2015). Quality of government and the returns of investment: Examining the impact of cohesion expenditure in European regions. Regional Studies, 49(8), 1274–1290. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2015.1007933

- Stefanov, R., Yalamov, T., & Karaboev, S. (2015). The Bulgarian procurement market: Corruption risks and dynamics in the construction sector. In A. Mungiu-Pippidi (Ed.), Government favouritism in Europe. The Anticorruption Report – Volume 3 (pp. 35–53). Opladen: Barbara Budrich.

- Surubaru, N.-C. (2017a). Administrative capacity or quality of political governance? EU cohesion policy in the New Europe 2007–13. Regional Studies, 51(6), 844–856. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2016.1246798

- Surubaru, N.-C. (2017b). Revisiting the role of domestic politics: Politicisation and European Cohesion policy performance in Central and Eastern Europe. East European Politics, 33(1), 106–125. doi: 10.1080/21599165.2017.1279606

- Wegener, S., Labar, K., Petrick, M., Marquardt, D., Theesfeld, I., & Buchenrieder, G. (2011). Administering the common agricultural policy in Bulgaria and Romania: Obstacles to accountability and administrative capacity. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 77(3), 583–608. doi: 10.1177/0020852311407362

- World Bank Group. (2015). Prioritization strategy for state-budget and EU-funded investments, according to harmonized selection criteria pursuant to EU-funded project. Washington, DC: World Bank. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/24447.

- Yanakiev, A. (2010). The Europeanization of Bulgarian regional policy: A case of strengthened centralization. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 10(1), 45–57. doi: 10.1080/14683851003606804

- Zaman, G., & Georgescu, G. (2009). Structural fund absorption: A new challenge for Romania? Journal for Economic Forecasting, 6(1), 136–154.