ABSTRACT

The Eurosceptic turnabout which has taken place in the CEE constitutes one of the most significant factors weakening the cohesion of the EU. In this group, Poland is the key element in view of its size and the status of the ‘poster boy’ of Europeanization acquired in the previous years. This paper analyses the major trends in the European policy of the Polish governments in the long-term period of 1990–2018 on the basis of standardized data (addresses by the Polish ministers of foreign affairs) and a quantitative analysis. These data also shed light on the essence of changes taking place in Poland’s EU policy. What appeared to be important was both the change in the country’s status after joining the EU, which limits the pressure of the EU (conditionality), and the arrival in power of populist, Eurosceptic parties.

1. Introduction

Sovereign and democratic Poland does not know any foreign policy other than that closely connected with the processes of European integration. The Polish road to democracy was simultaneously the road to a united Europe. Observed since 2015, the symptoms of moving away from democracy are combined with renouncing the policy of close European integration.

The following two aspects determine the significance of this article: the subject matter of the study and the unique form of the source.

Poland was the first and largest country of the former communist block to start the process of democratic transformation, combining it with its aspirations towards getting close to the EU and, in the longer perspective, acquiring the status of a Member State (Gavin, Citation2012). In the 1990s striving for membership in the EU constituted foundations for the country's both internal and foreign policy (Kułakowski & Jesień, Citation2007, p. 299; Poole, Citation2003, p. 54). Irrespective of any tensions or frictions on the way to the EU and those related to EU membership, Poland has earned the reputation of a difficult, yet predictable partner (Szczerbiak, Citation2012, p. 185; Vachudova, Citation2005, p. 20). It was only the change which occurred after the party Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS) had seized power in consequence of winning the presidential and parliamentary elections in 2015 that undermined, and in numerous aspects challenged the previous model of Poland's EU policy.

On 20 December 2017 the European Commission concluded that ‘there is a clear risk of a serious breach of the rule of law in Poland’ and recommended the initiation of a procedure under Article 7 of the Treaty on the European Union. Subsequently, on 2 July 2018, the Commission announced the initiation of ‘an infringement procedure to protect the independence of the Polish Supreme Court’ (European Commission, Citation2018). In just two years Poland lost its status of the ‘poster boy’ of democratization and Europeanization and became the ‘sick man’ of Europe. The United Kingdom's decision to leave the EU makes Poland a particularly crucial case of the largest country in the eastern part of the Union. Whether it will turn out to be a ‘new awkward partner or a new heart of Europe’ (Szczerbiak, Citation2012) will enormously influence the future of the whole European project.

2) The article is based primarily on Addresses by the Ministers of Foreign Affairs (AMFAs), which make it possible to look at more than a quarter century of Poland’s EU policy from the perspective of a stable and standardized form of communication. Their annual presentation constitutes a form of parliamentary control of a government's foreign policy. Each Member State of the EU has developed its own unique system of parliamentary debates over European issues; however, they usually have the character of periodic debates over particular initiatives or events taking place at the EU level (Karlas, Citation2011; Wendler, Citation2016, p. 76).

Information on the main directions of Poland's foreign policy, which is the most frequently used title of relevant documents, is embedded in a particular context of the parliamentary discourse (Meany & Shuster, Citation2003) or, generally, the political discourse on foreign policy (Daddow, Citation2015). Thus such information does not constitute a simple emanation of the government's intentions, but rather the effect of inter-party rivalry, the government's public relations activities. Furthermore, according to J. G. A. Pocock, political speeches constitute both the verbalization of a political act and a political act itself (Pocock, Citation1973, p. 27). The awareness of these conditions is indispensable for a critical analysis of AMFAs.

The objective of this analysis is to determine the following:

- the main tendencies in the Polish governments’ EU policy in the years 1990–2019;

- the impact of the government's ideological and programme-related factors on relations with the EU;

- Poland's key partners in multilateral and bilateral relations within the EU;

- the degree of political consensus among the parliamentary elites about the EU policy of the particular governments.

2. Data and methods

Content analysis constitutes the article's methodological foundation. It is based on the rules of the Comparative Manifesto Project (CMP). This method has been extensively described (Werner et al., Citation2015) and used (see: List of Publications, Citation2017). The form of the documents and the degree of their uniformity make the CPM a much more effective and precise tool for the examination of AMFAs than party manifestos for the study of which the method was developed. While party manifestos sometimes radically differ from one another with respect to volume, form or structure, AMFAs are standardized documents containing generally the same thematic categories which additionally are similarly structured. A change of government contributes to changes in the content, but the form remains basically unchanged.

This analysis focuses in particular on the following two categories from the CMP: European Community/Union: Positive (per108) and European Community/Union: Negative (per110). The analysis of bilateral relations within the EU required a correction in the existing code category. In the case of Poland, the research into party manifestos in the categories of Foreign Special Relations: Positive (per101) and Foreign Special Relations: Negative (per102) comprised the country's relations with the USA, Russia and Germany. In this analysis, these categories have been replaced by separate categories connected with relations with the particular EU Member States (Germany, France, and the United Kingdom).

AMFAs became a part of the Polish parliament's practice in 1990 (Sprawozdanie stenograficzne, Citation1990, p. 20). Speeches and subsequent debates are published in the stenographic reports of the Sejm's sessions and posted on its website (but not in one place) as well as on the website of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The AMFAs from the years 1990–2012 have been published in a book form (Ceranka, Citation2011). This article is based on the versions published in the stenographic reports.

In the theoretical dimension, the author follows the issue-salience approach, focusing on the importance of the EU in the structure of Poland’s foreign policy. Thanks to a methodological isolation of a particular issue from the entirety of the state’s policy, this approach allows the researcher to establish its importance, evolution, as well as conditions determining its content and character (Oppermann & de Vries, Citation2011).

European integration has constituted the foundation of Poland's foreign policy since 1990. presents the percentage of quasi-sentences (Q-S) dedicated to European integration divided into the three phases specifying Poland's status with respect to the EU. The ideological profiles of the governments presenting particular AMFAs have also been taken into consideration. The data included in constitute a starting point for the analysis of the general tendencies in Poland's policy towards the EU.

Table 1. Quasi-sentences (Q-S) concerning policy towards the EU in AMFAs in the years 1990–2019 (per cent).

Simultaneously, they provide a number of clues making it possible to identify the impact of the main four factors determining the importance of the European issue in the overall structure of Poland's foreign policy after 1989:

The status of Poland with respect to the EU;

The ideological and programme-related character of particular governments;

The coalitions and bilateral relations at the European level;

The level of political consensus.

AMFAs do not make it possible to identify accurately the significance of the particular factors. Referring to qualitative analysis, one can only indicate general conditions determining their significance in a particular configuration.

3. The status of Poland with respect to the EU

The factor of time (and Poland's changing status with respect to the EU) as the determinant of the significance of the European issue was of particular importance in the first two periods, i.e. the aspiration and candidacy periods.

During the aspiration period the growth of the significance of European integration in the structure of Poland's foreign policy was not linear as it was determined by progress in strengthening the country's relations with the EU. In that seven-year period, Poland built the foundations of its European policy and moved from the status of a completely external country to the status of an associated country ready to start membership negotiations. The EU was perceived in the categories of a historical and civilizational choice of a geopolitical option. Therefore, it was perceived as a part of a larger process whose objective was to ensure Poland's security, stable economic development and consolidation of democracy. Within the structure of the country's priorities, it was only the questions of security and defence that could compete with that of European integration (Carey, Citation2000, p. 53). During the whole period the image of the EU was unambiguously positive. In the qualitative dimension, the most characteristic element in that period was the highlighting of one objective, i.e. the EU's confirmation of Poland's membership aspirations.

During the candidacy period the salience of the European issue continued to grow. The key element in that process was the commencement and progress of the accession negotiations. In half of the examined cases from that period (six out of 12), the percentage of sentences dedicated to the EU exceeds 20 per cent. Poland's foreign policy and domestic policy were dominated by the process of integration with the EU. What was of key importance for that period was the governments’ focus on the conditions (primarily those related to financial matters) of membership, which had practically been a settled matter. The issues of the EU's character and its development model, i.e. what EU Poland wanted to join, were of marginal significance at that stage. And the image of the EU in that period was unequivocally positive; only once (2000) were reservations voiced about the proposed membership conditions. Poland’s accession to the EU yet again changed the status of the mutual relations and simultaneously the place of the European question in the country's foreign policy. An analysis of the political parties’ attitude towards the European integration in the period directly preceding Poland’s accession to the EU and in the period directly afterwards shows the phenomenon of relaxation. Political parties lost the main plane of dispute when the very issue of membership was decided in the referendum of 2003 (Zuba, Citation2009, p. 338). The analysis of AMFAs puts this question in a completely different light. From the perspective of the governments, the European question not only did not lose its importance but, just the opposite, as a trend, temporarily acquired (until 2012) an even higher standing.

The year 2013 witnessed a decline in the salience of the European issues. Originally quantitative, this change became also qualitative in character in 2016. A characteristic feature of the second sub-period was a radical increase in the number of negative statements; in one case their number was even higher than the number of positive ones – the only such situation in the entire thirty-year period of mutual relations between Poland and the EU.

A comparison of the particular periods shows general tendencies. However, what attracts attention is considerable fluctuations within the periods and, especially interestingly, within the particular governments. They were the most distinctive in the years 2008–2015 (the PO-PSL coalition government). These fluctuations can be explained if one takes into consideration the impact of the remaining factors. At this point, it becomes necessary to identify the factor which distorts the quantitative indexes of the importance of the European question. It is connected with the occurrence of particular critical events. If they concern integration with the EU (e.g. the commencement of the negotiations, the signing of the treaty, the beginning of the presidency), they cause a temporary increase in the importance of the European questions in AMFAs, but rather fail to influence the governments’ general attitude towards integration (the ratio of positive sentences to negative sentences).

The most distinctive change that took place in the same period was a radical intensification of the criticism of the EU by the rightist government of PiS in 2016. The reasons for such a violent Eurosceptic change are multidimensional. Previously masked, the ideological factor acquires strength and influence. Its role will be discussed below. The change occurred under the influence of both internal (the government's anti-democratic and nationalistic attitude) and external (the intensifying conflict with the EC and the leading countries of the EU: France and Germany) factors. The Polish government was clearly encouraged by the offensive of the Eurosceptic forces in Europe (the ‘illiberal’ government in Hungary; the referendum in the UK; the elections in the Netherlands and France).

The period of the PiS government (AMFAs: 2016–2019) brought not only a radical decrease in the salience of the European question, but first of all an increase in the number of negative sentences – for the first time after 1990 their number became comparable to that of positive sentences. At the same time, it should be remembered that the CMP methodology results in the overrepresentation of the latter type of sentences, classifying also neutral sentences as positive. Thus, the PiS government has rejected the principles of the European policy followed by its predecessors that – irrespective of ideological or programme-related differences – did not question the essence of European integration, let alone Poland’s presence in the EU. Regardless of the government’s declarations that European integration remains the pillar of Poland’s foreign policy (Sprawozdanie stenograficzne, Citation2016; Sprawozdanie stenograficzne, Citation2017; Sprawozdanie stenograficzne, Citation2018), AMFAs project a completely different picture. After the 2015 parliamentary elections, Poland’s previous European policy was questioned and even rejected.

4. Ideology and rivalry: the government – the opposition

The dispute about ideology as the determinant of the political parties’ and governments’ attitude towards the European question cannot be settled unequivocally (Mudde, Citation2011). Generally speaking, it is conditioned additionally by a number of other factors which either strengthen or weaken the role of ideology. One of the key elements is the positioning of a given party on the axis between the centre and the periphery of the political scene. If political parties show the ideological tendency towards Euroscepticism, they strengthen their criticism of the EU when in opposition and muffle it when they enter the core-government. For pro-European parties, the aforementioned change in their position is of no considerable importance (Sitter, Citation2002). What is of key significance in this aspect is the change from the strictly party point of view to the governmental one. The ideological factor becomes reduced, while the factor of rivalry between the government and the opposition gains in importance (Hirst et al., Citation2014, p. 114).

During the aspiration period, all parties shared a broad consensus about the questions of the European policy. Consequently, the factor of inter-party rivalry did not influence the position of these questions in the political discourse. It can be stated that this consensus muffled the ideological factor and the rivalry factor to the same degree.

Comparing the changes taking place between party manifestos and AMFAs may indicate the direction of the evolution occurring between a party's electoral platform and a government’s agenda. We are interested in absolute differences between these two types of documents rather than in relative ones. Thus, in order to reduce the radical disproportion between the number of Q-S dedicated to integration and included in party manifestos (they concern the overall policy) and AMFAs (they concern the foreign policy only), in the latter case, the number of Q-S was reduced tenfold. Consequently, they were reduced to the level of similar values. Presented in and , the differences between the party manifestos and the AMFAs have the character of an analytical coefficient, and not of a value in itself.

Table 2. The relative ratio of the number of quasi-sentences dedicated to European integration in the party manifestos to the number of such sentences included in the governing parties’ AMFAs in the years 1997–2001 (per cent).

Table 3. The relative ratio of the number of quasi-sentences dedicated to European integration in the party manifestos to the number of such sentences included in the governing parties’ AMFAs in the years 2005–2012a (per cent).

Let us have a closer look at two cases: one from the candidacy period and the other from the membership period.

The former case concerns the two parties which after the election of 1997 formed the coalition government: the rightist Solidarity Electoral Action (Akcja Wyborcza Solidarność, AWS) and the liberal Freedom Union (Unia Wolności, UW). In the pre-election period (particularly in the constitutional referendum period) AWS had earned the label of a party of ‘soft Euroscepticism’; UW – a label of a positively Euroenthusiastic party. After the election the AWS-UW coalition government was regarded as unambiguously pro-European. It can be assumed that the pro-European orientation of Buzek’s government resulted, to a considerable extent, from the fact that the European policy was the responsibility of Bronisław Geremek, a UW politician with established pro-European opinions. In order to verify this assumption with the AWS manifesto of 1997 we compared the AMFA (of the coalition government) of 1998 with the AMFA of 2001 delivered already after the collapse of the coalition, when AWS was individually responsible for the whole of the government's policy.

The data presented in indicate that the ideological change took place not at the level of developing the government’s agenda, but already at the level of the election manifesto in view of the expected electoral victory. The differences concerning this issue appearing between UW and AWS in the coalition government (e.g. the dispute over control of the European Integration Committee) were not reflected in the government's agenda, irrespective of who was responsible for Poland's foreign policy. A ‘cross’ comparison between both parties’ positions presented during the election period and during the period of running the coalition government shows a very strong pressure of the factors which reduced both the strength of the ideological factor and the status of a party in the interplay between the government and the opposition.

The other case concerns the years 2005–2012, when the Polish political scene was dominated by the rivalry between the two parties: PO and PiS. compares the number of quasi-sentences dedicated to European integration and included in PiS's manifesto from 2005 and PO's manifestos from 2007 and 2011 with the number of such sentences included in the AMFAs: for PiS from 2006 and for PO from 2008 and 2012.

indicates that PiS was the party which in 2005 changed its position presented in the election period the most. The party radically increased the relative number of positive sentences about European integration, substantially reducing the number of negative sentences in this period. PiS metamorphosed from a Eurosceptic party (2005 election manifesto) to the nominally Euroenthusiastic grouping (AMFA 2016). It can be said that in 2016 the party clearly was ‘no longer being itself’ with respect to its previous programme and ideology. What obviously worked in this case was a change in the party's position on the government-opposition axis.

In the context of the election of 2007, an important change could be also assigned to PO. In relative comparisons, the number of sentences in the AMFA of 2008 ‘decreased’ with respect to the party's election manifesto. However, these are only apparent changes. PO's manifesto of 2007 was ‘hyper-Euroenthusiastic’. A relative ‘decrease’ in the number of positive sentences dedicated to the EU and included in the AMFA of 2008 did not change the spirit of either document at all. The AMFA of 2008 is one of the most pro-European speeches delivered by Polish foreign ministers. Having been a Euroenthusiatic party before the election, PO remained such a party while forming a government after the election. This is proved by the absence of negative sentences in both the party's manifesto and the AMFA. Thus no changes took place in the ideological and programme dimension. The same conclusions apply to PO in the context of the parliamentary election of 2011. The observed change between the party manifesto of 2011 and the AMFA of 2012 does not indicate any shift in the party's ideology or programme; just the opposite, it proves the coherence between the programme of the party and the agenda of the PO government. Both documents were Euroenthusiastic, with the AMFA being hyper-Euroenthusiastic. Also both documents have no negative quasi-sentences dedicated to the EU.

In principle, the Polish case confirms the thesis that a given party’s participation (or even, as the case with AWS in 1997, prospects for participation) in the core-government suppresses Eurosceptical themes. However, in 2016 this logic was undermined. Before 2016 all Polish governments, irrespective of their coalition parties, followed the same line of policy towards the EU. There were a number of reasons for such a state of affairs. Firstly, despite using the European question at the domestic level, relative consensus was maintained in the area of foreign policy. Secondly, the determinants of European policy make each successive government follow the steps of its predecessors. In this respect, diplomacy has an important unifying quality as it is based principally on complying with previously assumed obligations which, unlike in the case of domestic policy, cannot be easily ignored. This is confirmed by the case of the right-populist government holding power in the years 2005–2007 (the AMFA of 2006–2007). The government was formed by the parties critical of the EU (PiS) or hostile towards the EU (League of Polish Families, Liga Polskich Rodzin, LPR; Selfdefence, Samoobrona). Aleks Szczerbiak notes that ‘ … at the EU level, the change of government in 2005 did not lead to a significant change in Poland’s approach to the core issues covered by this particular debate about Europe’s future trajectory … ’ (Szczerbiak, Citation2012, p. 47).

The situation was changed after the parliamentary election in 2015 when PiS established a single-party majority government.Footnote1 The data included in shows that in 2016 for the first time in the history of AMFAs and quite radically the number of negative quasi-sentences about the EU was larger than the number of positive sentences. Free from the limitations characteristic for the earlier periods, the ideological factor was able to operate with its full force. The policy of the PiS government is the policy of a radically rightist party for which the categories of the traditionally perceived state sovereignty, the ethnically perceived nation and the international relations defined in the vein of political realism result directly from its ideology and programme.

5. Alliances at the European level

The establishment of alliances – strategic or tactical ones – among countries is a normal thing in European politics. As a middle-sized country, Poland aspires to the role of an important player. Such aspirations manifested themselves, among other things, in the country's participation in such initiatives as the Visegrad Group (VG) or the Weimar Triangle (WT). In the former, Poland as the largest country in Central and Eastern Europe aspired to the role of the regional leader; in the latter, it positioned itself in the structure of relations with the European powers, i.e. Germany and France.

Avoiding drawing far-reaching conclusions, let us focus on three aspects related to both initiatives as a starting point for an analysis of Poland's alliances at the European level. Firstly, the average number of quasi-sentences dedicated to VG (1.32) is twice as much as the average number of quasi-sentences devoted to WT (0.63). Secondly, the number of quasi-sentences dedicated to VG is characterized by more fluctuations than the number of sentences about WT. In the case of VG there are years (1997, 2008) when this initiative is not referred to at all; 12 times the number of sentences exceeds 1 per cent, five times – 2 per cent, and once (2013) – 4.5 per cent. As far as WT is concerned, in only four cases the number of sentences exceeds 1 per cent, and only once – 2 per cent. Thirdly, VG is usually mentioned more frequently than the states participating in it, while in the case of WT, there is a reverse relation.

Thus it is possible to draw conclusions that confirm the image of both organizations existing in the literature on the subject. VG has more practical objectives than those of WT. VG is perceived as a category of a unique ‘interest group’, a sub-regional agreement (Törö et al., Citation2014) or even a geographical name of the most developed part of post-communist Europe (Fawn, Citation2001, p. 48). VG fulfilled an important coordinative role at the stage of accession negotiations. A considerably high level of fluctuations in the number of quasi-sentences dedicated to VG shows that it is not a permanent community of countries based on shared strategic objectives and visions, but rather a group uniting from time to time around common goals. This is also proved by the qualitative analysis of the documents; the years in which VG’s strategic character is emphasized are interwoven with the years when the initiative is said to be in crisis.

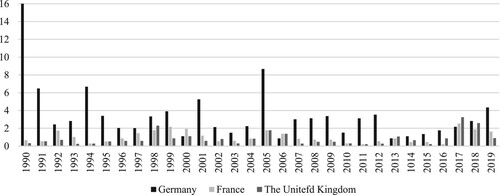

The Weimar Triangle has a consultative character and for Poland (and only for Poland) – a prestigious character. The weakness of this initiative is further determined by two more aspects. Firstly, the disproportion between the respective potential of Poland, France and Germany; Warsaw cannot be an equal partner for either Paris or Berlin in undertakings requiring the use of considerable (financial, organizational, political) potential. Secondly, the disproportion between the German-French relations, the Polish-German relations and Polish-French relations: we have very close German-French relations, close Polish-German, and poorly developed (and quickly worsening) Polish-French relations. The AMFAs () show clearly that WT is deprived of one side (the Paris-Warsaw axis).

Figure 1. The salience of Poland's bilateral relations with Germany, France and the United Kingdom in the AMFAs (per cent).

The take-over of power by PiS in 2015 resulted in a new proposal and initiative regarding regional coalitions within the EU. The Three Seas Initiative is based on the premise that the EU Member States located in the region between the Baltic Sea, the Black Sea, and the Adriatic Sea are able to create a separate coalition constituting a new political centre in the EU, capable of counterbalancing the growing domination of Germany (Zwolski, Citation2017, p. 173). This concept became one of the central elements of the European doctrine of PiS; its main theoretician and advocate is the president's consultant for foreign affairs Krzysztof Szczerski (Citation2017, p. 236). The Three Seas appear in all three AMFAs delivered by the PiS government and the average percentage of sentences from that period (1.43) show the priority character of this new project.

In the pre-accession period, both at the aspiration and candidacy stages, Germany played the key role in the process of Poland's integration with the UE. The role of the other Member States, including the two largest ones, i.e. France and the United Kingdom, appeared to be marginal.

The dominant role of Germany in Poland's European policy is understandable (Cordell & Wolff, Citation2005, p. 77; Lebioda, Citation2000, p. 165; Poole, Citation2003, p. 55), but it does not explain the lack of developed relations with the other Member States. In light of the AMFAs, France and the United Kingdom are second-order partners. They are usually dealt with in just one sentence, sometimes indirectly or contextually. Only once (in 1999) was France the subject of more than 2 per cent of quasi-sentences, although it was not the result of any intensification in mutual relations. This shows that Poland's European policy is the policy of the ‘near abroad’. It is defined primarily with respect to Germany, in both the positive and negative dimensions.

The rightist governments attempted to change this situation. In the AMFA of 2007, in the context of the relations with Germany, the foreign minister Anna Fotyga said, ‘Today, within the European Union, we have to jointly develop new and strong foundations for our strategic relations’ (Sprawozdanie stenograficzne, Citation2007, p. 366). Simultaneously, it had been the only AMFA since 1990 in which the number of negative sentences (2.24) dedicated to relations with Germany greatly (threefold) exceeded the number of positive sentences (0.86). It can be said that during the government of the PiS – Samoobrona – LPR coalition the role of Germany as Poland’s strategic partner in the EU was rejected, but no alternative solution was proposed. It was proposed in 2016 when PiS returned to power and formed a single-party government. In his AMFA, Witold Waszczykowski declared,

We will maintain the dialogue and regular consultations at various levels with the most important European partners – first of all with Great Britain, with which we share not only the understanding of many important elements of the European agenda but also the similar approach to the issues of European security. (Sprawozdanie stenograficzne, Citation2016, p. 78)

The meaning of this declaration was clear – Poland regarded its partnership with the United Kingdom as one of strategic importance within the EU. The erroneous assumptions for this position were disclosed in its confrontation with reality, mainly the British people's subsequent decision to leave the EU. In the two subsequent AMFAs of the PiS government of 2017 and 2018 the UK was the subject of the record number of sentences (3.25, 2.59 per cent; Germany – 2.17; 1.88). While in the AMFA 2017 it was directly the consequence of starting the Brexit debate, the attention devoted to the UK also in the following year indicates the will of the Eurosceptic PiS government to maintain strategic relations with London also after the UK's departure from the EU. It is symptomatic that both AMFAs did not include any critical sentences about the UK leaving the EU. Furthermore, Waszczykowski stressed that the UK's decision to secede from the EU was the factor determining the intention of strengthening cooperation with London: ‘In reaction to Great Britain's intention to leave the EU, we have undertaken successfully completed actions aimed at maintaining strengthened cooperation with that country’ (Sprawozdanie stenograficzne, Citation2017, p. 109). In his first AMFA, Jacek Czaputowicz, who replaced Waszczykowski as foreign minister in January 2018, adopted a similar tone (‘We emphasize that the European Union needs the United Kingdom also after it has left the organization. Relations between the two subjects should be as close as possible, but based on the balance of rights and obligations’; ‘The United Kingdom belongs to our closest partners’) (Sprawozdanie stenograficzne, Citation2018, p. 87).

6. The level of political consensus over the question of European integration

As it has been mentioned before, an AMFA was subjected to a vote if a relevant motion was put forward. If there was no motion, the Speaker proposed that the AMFA be adopted without a vote. The results of the votes make possible to assess the degree of political consensus in the Parliament over the government's position on European integration. AMFAs refer to the entire range of Poland's foreign policy, and not to European policy only, which also determines their weakness as a tool to measure consensus over the question of European integration. However, the following two aspects need to be taken into consideration. Firstly, votes on the European question only were so sporadic that it was impossible to use them as a basis for presenting a comprehensive and coherent picture. Secondly, as it was mentioned above, the European question dominated Poland's foreign policy. There was no other issue which would constitute a comparable plane of conflict. Constituting the second most frequently formulated plane of criticism, the relations with Germany were also discussed from the perspective of relations within the EU.

Let us stress again that if we assume that AMFAs give us a certain (imperfect) picture of the level of parliamentary consensus, such consensus concerns not European integration itself, but a particular government's policy towards European integration.

presents the results of the votes on the AMFAs in the years 1990–2017. If a vote was held, its result is given in the form of the percentage of the voting MPs. Votes ‘in favour’ were assigned to those who supported AMFAs, while votes ‘against’ to those who voted for motions to reject a particular AMFA. The table also identifies the party whose representative put forward a motion to reject the AMFA.

Table 4. The results of the votes on the AMFAs in the years 1990–2019 (per cent).

After 1989 it was generally accepted that Poland's foreign policy, and European policy in particular, should be subject to political consensus. This formula was effective during the first eight years (1990–1998), when the AMFAs were adopted without a vote. In 1999 Jan Łopuszański, the leader of NK, a small parliamentary fraction which had left AWS a year before, was the first to put forward a motion to reject the AMFA. Since then such motions have been proposed every year with the exception of the years 2006–2007.

The consensus over governments’ foreign policy was broken only in the candidacy period, at the stage of accession negotiations. The lack of such consensus was increasing (with the exception of the aforementioned period of 2006–2007). During the candidacy period, the percentage of MPs voting against AMFAs was growing linearly but never exceeding the threshold of 30 per cent. Three years after Poland’s accession to the EU, after the election of 2007, the consensus over governments’ foreign policy broke down. The parties of the government coalition voted in favour of the AMFA, while almost the whole opposition was against. Before 2016, motions to reject the AMFA had been put forward by the rightist parties only and the consensus had been broken unilaterally – the left and the centre supported the AMFAs of the rightist government in the years 2006–2007. In the years 2016–2019 also the centrist PO proposed a motion to reject the AMFA presented by the rightist PiS government.

We have been witnessing a gradual corrosion of the consensus over the government's foreign policy leading to its eventual breakdown. This manifests itself not only in the deepening polarization of the parliament in votes on AMFAs but also in the change in the models of putting forward motions for their rejection. Originally (1999–2005) such motions were proposed by marginal parties such as NK, PP, LPR, RKN. Among this group, it was only LPR that entered the parliament on its own, the other parties were the result of the disintegration of AWS. During votes motions proposed by these marginal groupings were gradually supported by more and more MPs from the larger opposition parties, particularly Samoobrona and PiS. At the next stage, motions to reject the AMFA were put forward by the representatives of the main opposition party: PiS in the years 2008–2015 and PO in the years 2016–2018. In the period from 2008 to 2010 such motions were tabled on behalf of the main opposition party (PiS) by second-rate MPs, and not its speakers responsible for the foreign policy (formally in the existing hierarchy, it is only the first MP that speaks on behalf of their parliamentary club; the others are so-called individual MPs). After the 2011 election the motion was proposed on behalf of PiS by the party's main speaker responsible for the foreign policy. All these elements create a picture of the gradation of the inter-party conflict about the country's foreign policy / European policy. At the beginning motions for the rejection of AMFAs are proposed by marginal parties, subsequently by the major parties, but under the pretence of not being involved (motions put forward by back benchers), and eventually AMFAs are openly challenged by the leaders of the opposition parties.

7. Conclusions

This analysis makes it possible to look at the three decades of Poland's integration with the EU from the perspective of standardized source material, i.e. AMFAs, and to formulate a few generalizing conclusions.

Poland's foreign policy is dominated by the policy towards and within the EU. It is only the issues of national security (in particular, membership in the NATO) that are of comparable importance, but even these issues are frequently related to European integration. A separate problem is to what extent the EU policy of a Member State is objectively included in its foreign policy. In Poland, however, it is still regarded as such, which is proved by the structural subordination of the EU policy to the minister of foreign affairs.

The key element determining the significance of the European policy was Poland's status with respect to the EU which could be divided into the aspiration, candidacy and membership periods. In all these periods the EU was presented by all governments in the unequivocally positive light; negative sentences have the character of individual objections which could be classified as belonging to ‘constructive criticism’. It was only in 2016 that this positive image of the EU was tarnished; the number of negative sentences in the AMFA presented by the rightist government of PiS decidedly exceeds the number of positive ones.

Before 2015 the ideological and political character of a government did not have much influence on its policy towards the EU. No matter how much a particular opposition party had previously criticized the government policy related to the question of European integration, when such a party participated in the establishment of a new government, it adopted a positive attitude towards the EU. After the 2015 election the single-party government formed by PiS was the first to question openly European integration as the main element of Poland's foreign policy.

Within the EU, Poland is building coalitions of Member States based mainly on the two initiatives: the Visegrád Group and the Weimar Triangle. VG has the character of an ad hoc coalition of interests established by the Central and Eastern European Member States, which, however, do not have the same strategic goals. WT has the character of a symbolic initiative. In view of disproportions resulting from the comparison of Poland's potential to that of France and Germany, the former is not able to establish fully equal relationships with the latter. The weakness of WT is also determined by the poor relations between Poland and France.

The analysis of AMFAs from the perspective of bilateral relations shows the domination of Poland's European policy by relations with Germany. The other Member States, including France and the United Kingdom, play a marginal role in this policy. The dominant role of Germany in Poland's European policy constituted a plane of criticism on the part of the rightist parties and governments. This led to a search of the rightist governments for alternatives to Germany as the main partner of Poland in the EU. In 2016, the attempts to base Poland's European policy on an alliance with the United Kingdom ended in a complete fiasco.

From 1990, parliamentary parties accepted the consensus over the question of Poland's foreign policy, including its European policy. Before 1999 AMFAs had not been subjected to votes, which in fact meant their adoption by acclamation. In 1999 this consensus was breached by a small rightist party in the parliament. Subsequently we witnessed a slow corrosion of the consensus; in votes on AMFAs, more and more MPs and opposition parties declared against the current government’s foreign policy. After the 2007 election the consensus was finally broken; the opposition parties started to challenge openly the common vision of the foreign policy, in particular, the common vision of the European policy. Before 2016 it had been only the rightist parties that had spoken out against the policy of a government other than their own. The initiators of motions for the rejection of AMFAs represented the rightist parties only. In 2005 the establishment of a government by the rightist and populist parties showed that the centrist and leftist parties were willing to return to the policy of consensus; during the two years of the government of PiS, LPR and Samoobrona, the opposition did not propose a motion to reject the AMFAs. The downfall of the rightist government indicated the return to the policy of confrontation, which has continued since the return of PiS to power in 2015 – remaining in opposition, in the years 2016–2019, PO put forward motions to rejects the AMFAs.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The structure of the PiS government is a little bit complicated. In the election, PiS ran as a single party, but it included the representatives of two smaller parties in its ticket. However, these parties did not form an election coalition with PiS and did not establish a government coalition after the election, either.

References

- Carey, R. (2000). The contemporary nature of security. In T. C. Salmon & M. F. Imber (Eds.), Issues in international relations (pp. 51–69). Routledge.

- Ceranka, P. (Ed.). (2011). Exposé Ministrów Spraw Zagranicznych 1990–2011. Ministerstwo Spraw Zagranicznych.

- Cordell, K., & Wolff, S. (2005). Germany’s foreign policy towards Poland and the Czech Republic. Ostpolitic revisited. Routledge.

- Daddow, O. (2015). Interpreting the outsider tradition in British European speeches from thatcher to Cameron. Journal of Common Market Studies, 53(1), 71–88. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12204

- European Commission. (2018, July 2). Rule of law: Commission launches infringement procedure to protect the independence of the Polish Supreme Court. Press release. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-18-4341_en.htm.

- Fawn, R. (2001). The elusive defined? Visegrád co-operation as the contemporary contours of Central Europe. Geopolitics, 6(1), 47–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14650040108407706

- Gavin, R. (2012). Poland’s return to capitalism: From the socialist bloc to the European Union. I.B. Tauris.

- Hirst, G., Riabinin, Y., Graham, J., Boizot-Roche, M., & Jijkoun, V. (2014). Text to ideology or text to party status. In B. Kaal, I. Maks, & A. van Elfrinkof (Eds.), From text to political positions. Text analysis across disciplines (pp. 93–115). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Karlas, J. (2011). Parliamentary control of EU affairs UN Central and Eastern Europe: Explaining the variation. Journal of European Public Policy, 18(2), 258–273. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2011.544507

- Kułakowski, J., & Jesień, L. (2007). The accession of Poland to the EU. In G. Vassiliou (Ed.), The accession Story. The EU from 15 to 25 countries (pp. 297–317). Oxford University Press.

- Lebioda, T. (2000). Poland, die Vertriebenen, and road to integration with the European Union. In K. Cordell (Ed.), Poland and the European Union (pp. 165–181). Routledge.

- List of Publications. (2017). Manifesto project data. https://manifestoproject.wzb.eu/publications/all.

- Meany, J., & Shuster, K. (2003). On that point! An introduction to parliamentary debate. International Debate Education Association.

- Mudde, C. (2011). Sussex v. North Carolina. The comparative study of party-based Euroscepticism (EPERN Working Paper, 23).

- Oppermann, K., & de Vries, C. E. (2011). Analyzing issue salience in international politics: Theoretical foundations and methodological Approaches. In K. Oppermann & H. Viehrig (Eds.), Issue salience in international politics (pp. 3–19). Routledge.

- Pocock, J. G. (1973). Verbalizing a political act: Toward a politics of speech. Political Theory, 1(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/009059177300100103

- Poole, P. A. (2003). Europe unites: The EU’s eastern enlargement. Praeger.

- Sitter, N. (2002). Opposing Europe: Euro-scepticism, opposition and party competition (SEI Working Paper, 56).

- Sprawozdanie stenograficzne. (1990). Z 28. Posiedzenia Sejmu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej w dniach 26, 27 i 28 kwietnia 1990 r. Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej.

- Sprawozdanie stenograficzne. (2007). Z 41. Posiedzenia Sejmu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej w dniu 11 maja 2007 r. Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej.

- Sprawozdanie stenograficzne. (2016). Z 10. Posiedzenia Sejmu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej w dniu 29 stycznia 2016 r. Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej.

- Sprawozdanie stenograficzne. (2017). Z 35. Posiedzenia Sejmu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej w dniu 9 lutego 2017 r. Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej.

- Sprawozdanie stenograficzne. (2018). Z 60. Posiedzenia Sejmu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej w dniu 21 Marca 2017 r. Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej.

- Szczerbiak, A. (2012). Poland within the European Union. New awkward partner or new heart of Europe? Routledge.

- Szczerski, K. (2017). Utopia europejska. Kryzys integracji i polska inicjatywa naprawy. Biały Kruk.

- Törö, C., Butler, E., & Grúber, K. (2014). Visegád: The evolving pattern of coordination and partnership after EU enlargement. Europe-Asia Studies, 66(3), 364–393. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2013.855392

- Vachudova, M. A. (2005). Europe undivided. Democracy, leverage, and integration after communism. Oxford University Press.

- Volkens, A., Lehmann, P., Matthiess, T., Merz, N., & Regel, S. (2016). The manifesto data collection. Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR). Version 2016b. Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung. https://manifestoproject.wzb.eu/datasets.

- Wendler, F. (2016). Debating Europe in national parliaments. Public justification and political polarization. Palgrave–Macmillan.

- Werner, A., Lacewell, O., & Volkens, A. (2015, February). Manifesto coding instructions (5th revised version). https://manifesto-project.wzb.eu.

- Zuba, K. (2009). Through the looking glass: The attitudes of Polish political parties towards the EU before and after accession. Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 10(3), 326–349. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15705850903105744

- Zwolski, K. (2017). Poland’s foreign-policy turn. Survival, 59(4), 167–182. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2017.1349825