ABSTRACT

This article provides an empirical contribution into the discursive repertoire of seven populist radical right-wing parties. Within the context of the European Parliamentary elections of 2014 and 2019, we examine and compare how these parties discursively shape the content of social demands by assessing how ‘the people’, ‘the nation’, ‘the elite’ and ‘others’ are constructed, and how different demands are incorporated. In doing so we assess the specific role of populism and nationalism in these parties’ discourse. We apply a two-stage measurement technique, combining both qualitative and quantitative content analytical modes of research, with advantages over existing methods, looking at both levels and form of the populist and nationalist signifiers. Our results suggest that although parties often combine both populism and nationalism, there is a general disposition to construct the signifer ‘the people’, not primarily through staging an antagonism between ‘people/elite’ (populism), but rather through articulating ‘the people’ as a national community in need of protection from the EU (nationalism). In view of this, we highlight that populism does not operate as the differentia specifica of populist radical right wing parties’ discourse.

Introduction

During the past two decades, the most prominent examples of populism in Europe has come in the form of parties broadly categorised as populist radical-right (PRR)Footnote1 (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2018). The notion of PRR parties has often been used as an umbrella term for these parties in Europe, and to label and distinguish radical right actors from their mainstream counterparts (Wodak et al., Citation2014). However, the applicability of the term ‘populism’ and its role as a defining feature of these parties has become somewhat of a ‘hot’ topic within the literature (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2018; Rooduijn et al., Citation2019). An increasing number of scholars have suggested that grouping together these political parties under the general header of ‘populist radical right’ may not only lead to conceptual confusion of populism with other ‘isms’, such as nationalism, but it can also reduce these actors to manifestations of the same ideology (Bonikowski et al., Citation2019; Brubaker, Citation2017; Charalambous & Christoforou, Citation2018; Glynos & Mondon, Citation2019; Van Kessel, Citation2015; Vasilopoulou & Halikiopoulou, Citation2015). Yet at the same time one should be careful that other isms such as nationalism do not become a euphemistic term for these parties in the same way that populism has done in media and academic discourse. Mudde (Citation2007, Citation2019), for example, not only notes the radical right as a particular form of nationalism (nativism) but he is also careful to point out how populism is not the key defining feature of these parties.

Despite the increase acknowledgment that populism is not always the ‘key’ element of these parties’ discursive repertoire, we argue that it is still used unchallenged by pundits and scholars alike as a defining mechanism of PRR parties. We are not alone in highlighting that this issue still maintains. Art (Citation2020, p. 1) raised very recently that the expansive use of populism has led it to become ‘a primary metanarrative’ to understand events in democracies, and the tendency to see it at work in very diverse populist parties. Yet, he suggests that it is still a deeply misleading lens. Indeed, how the different core components of populism are foregrounded in populist party discourse shapeshifts depending on what it travels with and therefore can vary considerably across populist parties and countries (Breeze, Citation2018; Kaltwasser et al., Citation2017). In light of this, De Cleen and Stavrakakis (Citation2017, Citation2020) suggest that if one wishes to grasp the complexity and variance of different populist actors one needs to distinguish between populism and nationalism. While populism discursively pits ‘the people’ against an ‘elite’, nationalism discursively pits the ‘the people’ as a homogenous national community against ‘dangerous others’ outside of the national community (Breeze, Citation2018; De Cleen & Stavrakakis, Citation2017; Stavrakakis et al., Citation2017). Although it is indeed possible to be both populist and nationalist, it is likewise possible for nationalist parties not to articulate populism or to incorporate merely peripheral populist features within a predominantly nationalist outlook.

Despite the theoretical advancement we still lack systematic comparative overviews of parties’ populism and nationalism that focuses on both levels and form. We belive that the empirical identification and separation of nationalist features from populist ones help, on the one hand, to better frame the current debate on contemporary populism and its effects on liberal democracies. On the other, highlights the need to use the label of populism more carefully as it does not seem to operate as the differentia specifica of such parties’ discourse.

The ambition of this article is therefore to make an empirical contribution to the current debate about how populism and nationalism, two distinct, yet interconnected, phenomena, are manifested in the discourse of contemporary PRR parties. We do so by applying a discourse-theoretical approach to operationalise populism and nationalism (De Cleen & Stavrakakis, Citation2017, Citation2020) as well as combining both quantitative (levels) and qualitative (forms) modes of research. This approach provides a detailed and comparative account of how the populist and nationalist signifiers are foregrounded and articulated by PRR parties across Western Europe. We are specifically interested in PRR parties given that populism is a ubiquitous term in the existing literature and therefore aim to dissect how these parties articulate the main components attached to nationalism and populism, broadly considered to be ‘people’, ‘elite’, ‘nation’ and ‘others’.

To this end, this study seeks to answer the principal question: are PRR discourses in the context of European Parliamentary elections primarily inclined to the populist or nationalist axis? To answer the question, we study the discourse of seven PRR-wing parties in Denmark, Germany, Greece, France, Italy, Spain and Sweden during European Parliamentary elections of 2014–2019.

This article makes three main substantial contributions. First, it provides empirical richness to the study of populism and nationalism within the radical right’s electoral communication and shows how often populist and nationalist signifers are identified. It demonstrates that although the up/down populist discourse operates to strengthen the nationalist discourse, the parties construct ‘the people’ as a relatively homogenous group with a shared nation, cultural heritage, and hostile towards an ‘outside’ immigration group. These ‘outside’ groups are constructed as posing a threat to the unity of ‘the people’, both culturally and in a more abstract form. As such, we argue that it is crucial to consider the other discursive features of radical right-wing parties and, more critically that the label of ‘populism’ in the populist radical right, despite it sometimes being said to be just an adjective, should be used more sparingly. Secondly, methodologically, it proposes a two-stage measurement technique, combining both qualitative and quantitative content analytical modes of research, with advantages over existing methods, because it looks at both levels and forms of populism and nationalism. Thirdly, we combine a corpus of manifestos, speeches and interviews, exceeding the national context, and answer if PRR parties position the signifiers mainly on the populist or nationalist axis during the two most recent European Parliamentary elections (2014–2019). We find, interestingly, that the form of expressions in manifestos is less circumspect than in the speeches and interviews.

Populism & nationalism: a discourse-analytical approach

Both nationalism and populism focus on a thinking that revolves around in-group/out-group classification, yet with different focuses. For nationalism the in-group of people is mainly classified as a nation, whilst populism sees ‘the people as demos’ (De Cleen & Stavrakakis, Citation2017). Both, however, tap into a more general predisposition to divide the world into ‘us’ and ‘them’. Given this it is not hard to see why there can be a confusion between the two. Mudde, for example, has argued that ‘the step from “the nation” to “the people” is easily taken, and the distinction between the two is often far from clear’ [sic] (Mudde, Citation2004, p. 549, Citation2007). De Cleen and Stavrakakis (Citation2017) suggest that the confusion often lays in whether the ‘in-group’ of ‘people’ is used to refer to ‘ethnos’ or ‘demos’ or both. Consequently, the nature of this ‘in-group’, how it is located in relation to the ‘out-group’ or ‘constitutive outsiders’ and how these are constructed can vary considerably across populist parties (Breeze, Citation2018). In order to grasp these nuances and differences an emerging scholarship have suggested that focus should be given to distinguishing between populism and nationalism in party discourse (e.g. De Cleen & Stavrakakis, Citation2017, Citation2020).

The discourse-analytical approach presented by De Cleen and Stavrakakis (Citation2017, Citation2020) builds on the poststructuralist discourse theory (Laclau & Mouffe, Citation1985) and understands populism as a discourse articulated around a down/up vertical axis, staging an antagonism between ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’. Nationalism prioritises an in/out horizontal discourse where the ‘in’ represents ‘the people’ as a homogenous national community and the ‘out’ the ‘dangerous others’. To examine populism and nationalism, De Cleen and Stavrakakis (Citation2017, Citation2020) suggest that scholars should focus on the construction or subject position of ‘the people’ political actors claim to represent (see also Howarth et al., Citation2000; Laclau & Mouffe, Citation1985). The construction of an identity through discourse targets and interpellates certain groups while excluding others. This dichotomous identification of difference produces a sense of collective identity and strengthens the identity of an ‘in-group’ against an ‘out-group’, to put it into spatial terms. Based on this separation, the different articulations of ‘the people-as demos’ and/or ‘the people-as-nation’ can offer a more precise understanding as to who is excluded, and by extent, who ‘the elites’ are and who the ‘others’ are (De Cleen & Stavrakakis, Citation2020, pp. 152–153).

This definition is not far from the more minimalist ideological definition of populism formulated by Mudde (Citation2007) and colleagues. But the notion of logic in the discourse-theoretical stance stresses more rigorously that populism is a way of formulating demands, rather than a set of demands. Given that we are interested in assessing and exploring how these demands are formulated and the particular way these are constructed (either in the name of ‘the-people-as-ethos’ or ‘the-people-as-demos’ and who the elite/others are) the discourse-theoretical elements provide us the tools to understand how discourse acquires meaning through the creation of political frontiers in social relations, and, in our case, how to classify the presence, salience and depth of populism and nationalism in the discourses of political parties. We therefore apply this conceptualisation of populism and nationalism to a broad sample of European PRR-wing parties than seen in previous scholarship, to determine its validity and further explore the possibilities of distinguishing populism from nationalism in the discourse of these parties. We focus our examination on how populist actors shape discursively the content of social demands (Laclau, Citation2005) by assessing how ‘the people’, ‘the nation’, ‘the elite’ and ‘others’ are constructed.

To this end, we perceive populism as a form of politics that entails the antagonism between ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’ (De Cleen & Stavrakakis, Citation2017). In populist terms, the element of ‘the people’ is an opposition to ‘the elite’ (Laclau, Citation2005; Stavrakakis & Katsambekis, Citation2014). Populism can be situated on a vertical axis, up/down or high/low, based on socio-economic or socio-cultural coordinates (Dyrberg, Citation2003; Ostiguy, Citation2009). Nonetheless, populism does not solely focus on the word ‘the people’, but equivalent references to ‘the common man’, or ‘the ordinary people’ etc. can be employed, as long as these phrases/words embodies ‘the people’ as the ‘underdog’, put in juxtaposition to ‘the ruling class’ or ‘the establishment’.

Nationalism is a discourse that constructs the nation (Day & Thompson, Citation2004; De Cleen & Stavrakakis, Citation2017). Within this context, the first element in the discursive definition of nationalism is the signifier ‘the nation’, serving as the nodal point of the discourse around which all other signifiers such as ‘state’, ‘democracy’ and ‘culture’ take their meaning (Freeden, Citation1998; Sutherland, Citation2005). However, in such nationalist configuration, ‘the people’ can be invoked as a nodal point around which every other element is articulated. In this instance ‘the people’ is utilised in a way to draw its meaning from the nation, and it functions as synonymous to the nation; that is to say, ‘the people’ operates as representing the national community envisaged as a sovereign entity with a shared historical past, space, culture and tradition. In other words, ‘the people’ indicates a signifier attached to the signified ‘the nation’ – the ‘in-group’ – and ‘out-group’ consist of those not belonging to or being outside of the nation (De Cleen & Stavrakakis, Citation2017; Freeden, Citation1998).

We should mention here that nationalism has many faces, ranging from ethnic and civic nationalism to nativismFootnote2 (Bonikowski et al., Citation2019; Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2013, p. 2018; Halikiopoulou et al., Citation2012). Yet despite there being different forms we argue in line with Breeze (Citation2018, p. 2) that this does not invalidate the use of the term itself ‘as long as we understand this to refer to the core structure of the concept, rather than to details of its manifestation in particular cases’. In fact, the essential components (in/out) of the above instances of nationalism are very similar. Civic nationalism, for example, is based on the idea of a more political understanding of belonging and a protection of that belonging, whilst ethnic nationalism is based on the ideas of shared ancestry and a protection of those shared values (Bonikowski et al., Citation2019; De Cleen, Citation2017; Spencer & Wollman, Citation1998; Stavrakakis et al., Citation2017). Nativism, which has been argued to be similar to the more common concept of ‘ethnic nationalism’ (Rydgren, Citation2010) is based on the idea that non-native elements (persons, institutions, norms or ideas) are threatening the ‘the people’ of same ancestry (Riedel, Citation2018). Yet all forms centre on the idea of a shared space with clearly defined boarders and on the homogenous ‘in-group’ of that shared space, who are united by their specific shared characteristic, be it cultural, language, or values (Freeden, Citation1998). Moreover, they all suggest a notion of protecting the interest of the ‘domestic’ over the interest of ‘the other’ (Freeden, Citation1998). In this respect, the inclusiveness of nationalism may vary, not all forms of nationalism are exclusionary (as seen e.g. in the Scottish National Party and various Catalan nationalist parties), whilst others will take on more of a ‘ethnic’ and exclusionary form (or nativist) (Riedel, Citation2018). While the respective definition of nationalism also states something similar, emphasis is given on ‘the nation’ as a national community in a broader manner. In this respect, nationalism articulates the people as a homogenous bloc contrasted to nations or entities outside this bloc.

summarises the operationalisation and core structural characteristics of nationalism and populism at the centre of our analysis. Consequently, our analytical framework consists of two kinds of articulation. It is worth noting that we expect a potential trade-off between the two as we are studying PRR parties.

Table 1. Conceptualisation of nationalism and populist discourses.

Analytical approach

We analyse first the presence of populism and nationalism in the discourse of seven different PRR parties; Danish People’s Party (DFP), Alternative for Germany (AfD), the Independent Greeks (ANEL), the League, National Rally (RN), the Sweden Democrats (SD) and VOX. The aim is thereafter to compare how these parties articulate their vision of ‘the people’, ‘the nation’. ‘elites’ and ‘other’, and how these signifiers are positioned on the in/out and up/down axes. Although these parties are not identical, in the sense that they have different histories and campaign on different platforms, they all share a common denominator of nationalism, authoritarianism and populism, which we are interested in dissectingFootnote3 (Krisi & Pappas, Citation2015; Mudde, Citation2007). In this respect, we follow a diverse case selection strategyFootnote4 that aims to maximise the variance among the relevant dimensions of political competition (Gerring, Citation2008, p. 650). Yet, we restrict our analysis to include cases from Western Europe, given the difference in the structure of political opportunities that exists for PRR in Central and Eastern European countries (Allen, Citation2017; Pytlas, Citation2018).

The seven cases are therefore selected on the basis of their (i) regional geographical position; (ii) records of governmental participation; and (iii) electoral success (see ), which allows us to separate the populist and nationalist discourses from the potential oppositional behaviour of these parties. In this respect, we acknowledge the importance to move from the challenger/outsider paradigm in studying the populist radical right (Mudde, Citation2016), by including parties with a diverse record of governmental participation. Among our cases, four never took part in the national governmental arena (RN, SD, AfD and VOX). One party, despite its support of minority governments and its high degree of integration in its party system (Christiansen, Citation2017), never officially entered into government (DFP); while the remaining two parties possess experience in government (League and ANEL). Finally, all the countries are members of the EU in which our cases also show a high variance in their degree of electoral success in EP elections (see ).

Table 2. The domestic path of RRP parties: year of establishment, electoral results* and governmental experiences.

Table 3. European Parliamentary election result 2014 & 2019 of seven PRR parties (%).

Among the various possible arenas for analysing populism and nationlism, we focus on manifestos, speeches and interviews produced during the 2014–2019 EP elections. EP elections are interesting in their own right. First, we aim to move beyond the national context. Second, we have witnessed a sharp rise of parties on the right extreme of the political spectrum in especially EP elections, and thus, the landscape of representation, in the EU, has been markedly changed. Moreover, EP elections can still be regarded as second-order elections, a competitive context in which strategic considerations have less relevance in the minds of voters and thus benefiting small and peripheral parties (Reif & Schmitt, Citation1980; Schmitt-Beck, Citation2017). By focusing on the two most recent EP elections (2014–2019) it allows for the investigation of the same time-setting across all seven cases and enhances comparability. In this respect, our study includes ‘two waves’ of electoral periods: 2014–2019.

For our research, we focus on party manifestos, leader speeches and interviews. By analysing different sources we will be able to assess if some communication channels are more inclined to transmit populist and/or nationalist discourses. When a source was not available, we selected proxy documentsFootnote5 such as televised interviews (for the full list of our corpus see online Appendix).

The EP manifestos published by all the respective parties were obtained from the Euromanifesto Study (Schmitt & Teperoglou, Citation2016). Manifestos were chosen as they are appropriate documents for comparative content analysis due to their reasonable comparability between countries and over time (Klemmensen et al., Citation2007; Rooduijn et al., Citation2014). When available, we collected three campaign party-leader speeches that took place before, during and after the EP election. We chose two interviews with the party leader that took place before the EP election, but not exceeding either the year of 2014 or 2019.

A qualitative content analysis with a quantitative component proceeding in two steps was applied. First, we focused on manifestos and the quantitative component of the study.Footnote6 The material was divided into quasi-sentence,Footnote7 which were analysed separately, assessing if it was better classified as populist and/or nationalist. The number of units classified as populist and/or nationalist were thereafter quantified, and its share on the whole amount of textual units was calculated to get a respective percentage value. The quantification is an attempt to explore the levels of populism and nationalism used by the parties.

In a second analytical step, we employed an in-depth qualitative approach to assess how the parties construct and articulate the signifiers of ‘the people’, ‘the nation’, ‘the elite’ and ‘others’. Here we focused on the EP manifestos, speeches and interviews. The speeches and interviews have not been divided into quasi-sentences; instead, the whole text or transcripts has been assessed to provide an in-depth analysis. By doing so, we gain insight into how the discourses are positioned on the in/out and up/down axes. We hold that, to derive the meaning of a text with all its nuances and to determine if it resembles a manifestation of complex phenomena like nationalism and populism, qualitative interpretative analysis of the texts acquire advantages over its alternative to get an in-depth understanding of the different constructs.

Findings

Quantitative results: manifestos

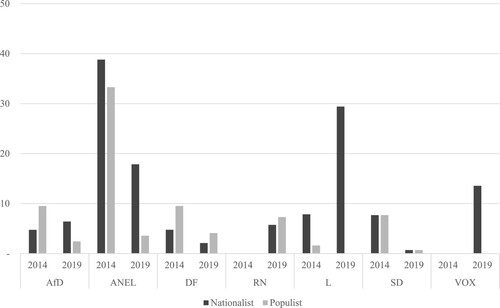

presents the frequency of populism and nationalism identified in the seven parties’ manifestos between 2014 and 2019. It highlights that both populist and nationalist discourses co-exist, yet to varying degrees in each case.

Figure 1. Nationalist and populist discourses in 2014 and 2019 European election manifestos.

Note: The data shows the percentages of nationalist and populist quasi-sentences out of the total number of quasi-sentences contained in the document (N). The N of each party follows: AfD 2014: 294; AfD 2019: 452; ANEL 2014: 17; ANEL 2018: 27; DFP 2014: 21; DFP 2019: 48; RN 2014: 21; RN 2019: 888; L 2014: 498; L 2019: 17; SD 2014: 39; SD 2019: 423; VOX 2014: 18; VOX 2019: 273.

Parties such as ANEL and the League used more nationalism than populism in both manifestos. In contrast, the German AfD, employed more populism in 2014, whilst shifted its discourse in 2019 to include more utterances identified as nationalist. For VOX we identified only nationalist utterances in the 2019 manifesto (13.5 per cent), whilst neither populism nor nationalism were identified in the 2014 manifesto.

In the French case, RN did not issue a manifesto for the 2014 election and therefore we are unable to provide a comparative perspective. Yet, in the 2019 manifesto, populism rather than nationalist utterances was identified to a greater extent. also shows an equal distribution of populism and nationalism between 2014–2019 in the Swedish case. Finally, DFP employed more populism than nationalism throughout both elections.

To further provide a more nuanced overview of the populist and nationalist expressions employed by the parties, the indicators have been disaggregated by years and party, presented in the below frequency table ().

Table 4. Percentages of populism and nationalism in parties’ manifesto (2014–2019).

In general, then, the result from the quantitative analysis shows that there is no clear trend whether populism is more present than nationalism amongst parties’ manifestos. In fact, the levels varied between cases. We recognise that the variation could be case specific reasons such as party specific factors, inter-and within-party changes. For example, VOX was still a newly established rightist party during the 2014 election but in 2019 established a more populist radical right-wing agenda (Ferreira, Citation2019). The League, as well as ANEL, underwent a process of change during the period in focus. For the League it suffered the worst national electoral results in 2013, whilst reached highest popularity and became the largest party in Italy in 2019 (Albertazzi et al., Citation2018).

Overall, the result suggests that the degree of nationalism and populism varies between cases and thus could be dependent upon the different parties’ trajectories within their national party system (see also ). The analysis now moves to the second stage (qualitative) focusing briefly on the main signifiers of populism and nationalism of each party.

Qualitative analysis

Constructing ‘the people’

According to our analysis, all parties assumed a homogenous vision of ‘the people’, and we note similar constructs across the cases. Firstly, all parties explicitly presented their vision of society within its national context, making frequent use of adjectives such as ‘the French’, ‘the Spanish’, ‘Danes’ and ‘Italians’, ‘we’ and ‘here’ when formulating its demands for ‘the people’.

Secondly, nationalist sentiments are foregrounded in the construct of ‘the people’ in all cases. This primarily revolved around articulating a universal state of identity and belonging set closely to the national community and cultural traits. Take for example VOX which insistence ‘the Spanish people’ as a unitary group bound by specific values, unique to Spain and the Spanish nation. More specifically in the 2019 speech and manifesto, VOX leader Abascal suggested that these ‘values’ were part of the Spanish national identity. He refered to ‘bullfighting, hunting and rural life’ – all reputed as ‘core’ Spanish traditions and a cornerstone of the Spanish identity (VOX, 2019a, 2019b). A similar construct is further noted within the electoral communication of the French RN, where ‘the people’ is formulated close to the national community. For example, we find reoccurring references to ‘the great French people’, those ‘who believe in France and its beauty’ (RN, 2014a). In parallel, ANEL argued that ‘the Greek people have a common culture and history and above all, share this in their bravery’ (ANEL, 2014a). ‘The people’ as a subject is, for ANEL, connected by ‘the Greek soil’ and ‘Greece’s national sovereignty’ (ANEL, 2014b).

The League also referred to the national context with specific cultural characteristics as the nodal point for the construction of ‘the people’ (League, 2019a, 2019b, 2019c). Here, specifically, the division is articulated by juxtaposing the interest of the Italian people and those of foreign heritage. Although this can be interpreted as an attempt for the party to appeal to the national interest of the whole Italy, the League’s independentist roots and its rhetoric legacy – discriminating against southern Italians – prevented the party to fully construct the nationalist discourse around a common and shared culture. In view of this, one can compare the nationalist discourse of the League to an ‘empty vessel’ as it failed to construct the boundaries of the ‘Italian identity’ (Albertazzi et al., Citation2018, p. 661). This nationalist discourse has mainly been articulated through the threat related to migration flows, building a demarcation between the Italian people and migrant ‘other’ (League, 2014b).

The references to ‘the people’, in the above cases, illustrate that the formation of the political subject, ‘the people’ is articulated mainly within a nationalist paradigm. All parties formulated their demands around ‘the people’ united in their shared values, similarities, and thus a constant flagging of the national identity. We also noted the use of small but crucial words such as ‘we’ and ‘here’, reinforcing the ‘in-group’ identification of the nation. In many instances, however, the reference to ‘our values’, ‘our identity’ and ‘national sovereignty’ was not elaborated and tended to remain on an abstract level. In doing so the opposition (out-group) is to be assumed, despite ‘the people’ being explicitly articulated.

Turning our attention to potential variation between sources and cases, we note two points worth raising. First, the form of expression in manifestos tended to be less circumspect than in the speeches and interviews. In general, PRR leaders are more explicit in their construct of ‘the people’ in speeches and interviews than in manifestos. For example, actors tend to speak more freely about the ‘outside forces’ that are allegedly menacing ‘the people’ ranging from the influx of immigrants and culture of the ‘others’. In this way the demarcation lines between ‘us’ and ‘them’ are more strongly formulated in speeches and interviews than manifestos. By explicitly identifying what the ‘others’ are, and in effect what ‘the people’ are not, it strengthens the homogenising of the in-group and threat of the out-group.

Interestingly, both DFP and AfD shifted their discourse between the 2014 and 2019 elections. For example, in the 2019 manifesto, there are rarely any instances where the DFP positions ‘the people’ either on the top-down nor in–out axes. This is somewhat unexpected, yet we believe that this could in part be due to DFPs participation in the centre-right coalition. With DFP striving for political normalisation the party has at times abandoned some of its more radical standpoint (Meret & Borre, 2014). Indeed, the general behaviour of populist parties tend to change when entering coalition (Rydgren, Citation2010). For example, any coalition between mainstream and populist might hamper the populist party to present itself, with credibility as the opposition to the political class (Rydgren, Citation2005, Citation2010) and thus adopt a more mainstream guise, which might explain the lack of populist and nationalist discourses during the 2019 election.

While DFP toned down both its populism and nationalism, in 2019 AfD spoke more often of immigrants set against the integrity of the German national identity. In this respect, the down/up spatial representation shifted to be positioned on the horizontal axis, in the way that De Cleen and Stavrakakis (Citation2017) regard the characteristic of nationalism. For example, we note reoccurring references to ‘the fatherland’ (Weidel, 2019a) rhetorically constructed as a place for the German ancestry, true language, and the Germans own cultural traditions. Interestingly, these values and cultural traits are described as German ‘human rights’ (Gauland, 2019). As mentioned above, there is an overt message about ‘us’, the Germans and the German ‘fatherland’, which can be associated with the representation of the nation as an imagined community (Lauenstein et al., Citation2015; Taggart, Citation2000). This message is even further amplified with reference to Islam and Sharia Laws, deemed as incompatible with the ‘fatherland’ and ‘our fundamental values of freedom in the West’ (Weidel, 2019b). By continually flagging or reminding the audience about the fatherland versus the immigrant ‘other’, AfD can reinforce the cultural difference between the nation (‘us’) and ‘others’.

The shift from populism to nationalism in the German case, may be a sign of the intra-party strife, on the one hand, which has led to frequent changes in leadership and consequently discourse and ideological orientation of the party. From Lucke and Henkel’s Euro criticism, Frauke Petry’s national conservatism, to Gauland’s identity politics (Decker, Citation2016, pp. 5–6), AfD has been subjected to various modifications of its agenda which, by extend, may have changed the focus of its political strategy. On the other hand, it could be interpreted as a sign that populism and nationalism are conditional qualifiers to another, signalling the fluid state of populism in contemporary European radical right.

Elites and the threat from the outside

Anti-elitism is directed mainly against ‘Brussels’ and the ‘established elites’. In many instances, these elite groups are described as a socio-political force that exists outside of the national community and acting against its very own community. These elites are portrayed as favouring the values and status of those who are deemed as not being part of ‘the people’ (‘the outsiders’), rather than the actual national ‘people’. The elites are, in this sense, aligned against ‘the people’ from the outside, in the way that De Cleen and Stavrakakis (Citation2017) regards the characteristic of nationalism positioned on the horizontal axis.

According to the findings, the parties’ anti-elitism and ‘otherness’ can be divided into two categories: those that maintained the same construct of the elite and ‘others’; and those that shifted their discourse between the elections.

The former group of parties where the same construct is identified throughout 2014–2019 consist of ANEL, DFP, League, RN and SD. These parties speak mainly of the elite and ‘others’ in three different ways. First are references to the national elite. All parties focused on the national established parties, portrayed as having broken their commitments and bond with ‘the people’. Here the established parties are constructed not only as incompatible and unfit to lead the national people, but also as having betrayed the community by ignoring the danger of immigration, multiculturalism and internationalisation. In this respect the ‘outsiders’ are not only elites but entwined with the threat of the dangerous others.

Second are references to the elite outside of the national context. In most cases this type of anti-elitism was directed mainly at the EU, portrayed as an entity endangering the national cohesion. The main message of the five parties (ANEL, DFP, League, RN and SD) is that the EU has acted without obtaining any democratic legitimacy from the national ‘people’. ANEL, for example, suggests that the nation-state in general, and the Greek national identity more specifically, is threatened by a ‘federalised Europe’ (ANEL, 2019). Similarly, DFP argues that the EU, as a political apparatus, is jeopardising and corrupting Danish sovereignty as it prioritises ‘cheap eastern-Europeans’ over ‘Danish workers’. For the SD focus is on ‘taking back control’ from the supranational order. This message was foregrounded in the 2014 manifesto title ‘more Sweden, less EU’ (SD, 2014a).

For both the League and RN there is a strong focus on the national sovereignty and ‘the fatherland’ opposed to the supranational project. According to RN, the EU as a union of elites has endangered and inflicted upon the French integrity and national sovereignty. Yet, the EU and its elite have not acted alone. At their side stand the ‘national established elite’ giving, ‘gladly away Frances national sovereignty’ (RN, 2014a). Although not as strongly voiced as the discontent towards the EU, the populist perception of ‘the people’ as underdogs and ‘elite’ is evident in the interaction between RN’s self-image, as ‘the good-guys’ defender of the French peoples’ interest, and the perception of the establishment as ‘evil’, ‘backstabbing’, who have ‘betrayed the opinion of the French people’ (RN, 2014a, 2014b).

The third type of references identified in the communication of these parties concern issues related to immigrants and refugees. For ANEL, DFP, League, RN and SD, the ‘outside’ groups are portrayed as a threat to the national homogeneity in general, and the whole European civilisation more specifically. We find that all parties employ anti-Islamic rhetoric, juxtaposing the ‘Western civilisation’ or ‘Europe’ against ‘Islam’. For example, ANEL speaks of ‘the Greek people’ versus ‘Islam’s attempt to invade the Balkans’ (Kammenos, 2019a).

Another telling example is found voiced by RN. The internal threat takes its form by differentiating between French values and the values of other specific cultures, mainly Islam. In an interview, Le Pen articulated an extreme discontent that over 8000 chocolate mousses had been thrown away because it contained pork jelly (RN, 2014b). Although a symbolic construct, Le Pen refers to the abstract figure of Islam as an internal threat to French (gastronomic) values. The idea, according to Le Pen, of throwing away French food in France just because its content is not in line with some religious aspects of Islam, undermines the inherent character of the French community.

Moving on to the categories of parties that did change their framing of the elite between elections were AfD and VOX. In 2014, AfD positioned the elite mainly on the populist axis, focusing on both domestic (established party, SPD and CDU/CSU) and supranational (‘EU’, ‘European Central Bank’, ‘IMF’) forces. These elite groups were framed as not representing the true will of ‘the people’ (AfD, 2014a, pp. 4–8; Lucke, 2014a). Yet during the 2019 election a notable shift can be observed. Although the elites still featured as the bad guys, the ‘others’ take more of a central position. ‘The elites’ are not only portrayed as not being the true representer of ‘the people’ but they are also supporting immigrants and refugees at the expense of the German people, the German identity and its cohesion. As in the case of the French RN, Islam and Muslims are main targets, framed as an unwanted ‘wave’, incompatible with the German culture and values.

In an interesting contrast, VOX did not display any populist nor nationalist features during the 2014 election. We believe that this is due to its history. In 2014 the party described itself as a ‘centre-right national party’ (quoted in Ferreira, Citation2019, p. 76). Yet, post 2014 election, the party changed its course. The new leader Abascal, in an attempt to distance the party from other centre-right competitors (PP and Ciudadanos), moved closer to the radical right by promoting authoritarian policies in reaction to the Catalan separatist threat and suggested controversial measures to curb immigration (Turnbull-Dugarte, Citation2019). As such, in 2019 there is a predominant focus on articulating the signifiers on the nationalist axis. In this context, Spain’s national integrity is threatened mainly by the ‘other’ migrants, but the liberal politicians are also foregrounded in this context. The main claim is that progressive liberal legislations are endangering the conservative and national values of ‘the people’.

Conclusion

This article illustrates that the core features of the seven PRR parties did not revolve around a populist vertical opposition between ‘the people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’. Instead, our two-stage measurement technique combining both qualitative and quantitative content analytical modes of research showed that these parties employed a strong predisposition to articulate ‘the people’ as a national community embedded in exclusionary claims. The enemies were set as external to ‘the people’, consisting mainly of a ‘dangerous other’ (foreigners and migrants). In terms of the parties’ populism, we noted that even when parties employed a vertical top-down articulation, it was still embedded, to a great degree, in the distinction between the national community and its cultural-ethnic outsiders. Moreover, the speeches and interviews of the parties revealed a construct of ‘the people’ menaced by outside forces in need of defence. The populist elements remained secondary to the nationalist in this respect. There are cross-party variations, as noted above, that are worth re-visiting (see ).

Table 5. Values of populism and nationalist signifiers in PRRP discourses 2014–2019.

First, we found that some parties, such as AfD and the League, shifted how they positioned the signifers of ‘people’, ‘nation’ ‘elite’ and ‘others’ from the populist axis to the national one between 2014 and 2019. In other cases, such as the French RN, we noted the opposite. During the 2014 election RN centred primarily on articulating the subject of ‘the people’ as a nation, whilst in 2019 this horizontal in–out articulation was toned down. In its place, we noted a stronger emphasis on the sovereignty of the people not against ‘the dangerous others’ but against the EU, as part of the political elite.

In the other cases, a continuum of the same discourse was observed. Mainly the nationalist articulation of ‘the people’ was supplemented by the antagonism against the supranational elite and the national political class. For example, DFP maintained their construct of ‘the people’ closely connected to the national community. ANEL focused mainly on the people as nation, while populism and its vertical articulation was a secondary feature. In the same vein, SD blamed Swedish elites for their lack of responsiveness, yet the party constructed ‘the people’ predominantly based on Sweden as a national community.

Moreover, our analysis showed that the form of expression in manifestos was less circumspect than in the speeches and interviews. One plausible explanation relates to the issue some scholars have raised regarding the format of manifestos themselves (Rooduijn et al., Citation2014). As election manifestos are ‘the official statements of intended policy issued by political parties at the beginning of election campaigns’ (Robertson, Citation2004, p. 295), these might contain less populist and nationalist statements, and focus more on the policies of the parties, than speeches and interviews.

Our initial question was if PRR parties’ discourses in the context of EP elections were primarily inclined to the populist or nationalist axis. Revisiting the question, we want to address a couple of final points. The separation of populism and nationalism is a delicate undertaking given that the two are often intwined. Indeed, our analysis reflect this and highlighted that in many instances the parties articulated the vertical and horizontal axes simultaneously. However, the in/out axis seems to be more prominent because these parties address ‘the people’ as a homogenous group with a shared culture and with reference to the nation set in stark contrast to immigrants, multiculturalism and internationalisation, in addition to taking a critical stance towards the ‘elite’, both nationally and supranationally. In this way, the up/down populist discourse operated to some degree to strengthen the nationalist discourse of these parties. On balance, the populist features act more as a conditional qualifier to boost the nationalist exclusionary discourse: the political, supranational and foreign class takes a ‘top’ position – in populist terms – whilst ‘the people’ threatened by these elites overlap to a great degree with the national community which excludes foreigners, migrants and non-integrated citizen. Thus, in these terms, ‘the people’ acquire a homogeneous and indivisible status that perfectly overlaps with the boundaries of the national community.

In view of this, we suggest that that the other discursive features of radical right-wing parties especially nationalism should be addressed more emphatically, and, most importantly that the label of populism should be used more sparingly and not as a defining feature, not even as an adjective of those parties, given that ‘the-people-as-a-nation’ generally prevails within these parties’ discourse.

There are two main areas for further research opening themselves here. The first would be to include a greater variety of countries, specifically those of Eastern Europe to provide a more inclusive and comprehensive understanding of PRR party discourse across Europe. The results from our research showed that neither populism nor nationalism remains constant. Indeed, we recognise that the fluctuation of these discursive elements of each party could also be affected by the socio-political context. As such, the second line of research would be to focus on a more extended time period to enable comparison to be drawn to a greater degree. Nonetheless, our research should be seen as an empirical contribution to de Cleen’s & Stavrakakis’ research (e.g. Anastasiou, Citation2019; Breeze, Citation2018) and as a motivation for scholars to undertake more empirical research on the subject of the intersection between populism and nationalism.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (33.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Benjamin De Cleen, Yannis Stavrakakis, Aurelien Mondon and Giorgos Katsambekis for their valuable feedback and insightful comments on an earlier version of this article, and an extended thank you to the reviewer and editor for comments and feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 We focus our analysis on radical right-wing parties as opposed to extreme right wing or far right parties. This decision has been guided by the debate on the differences between the two categories that started in the beginning of the XXI century when the term ‘extreme’ was associated with an explicit rejection of democracy in favour of anti-parliamentarism or corporativist arrangements (Minkenberg, Citation2000; Mudde, Citation2007; Zaslove, Citation2004). The term far right, instead, has been recently (re)popularised by Mudde, in order to combine radical and extreme right parties (Citation2019). Considering our focus on populism and nationalism, and the inherent link that the former possesses with democracy (e.g. Canovan, Citation1999), we decided to focus on radical right parties as opposed to far right.

2 The meaning of the term nativism, as well as populism and nationalism, depends on the context in which it developed and connected to populism (Betz, Citation2017, Citation2019), making nativism a ‘highly contested’ term with multiple understandings and variants (Betz, Citation2019, p. 111).

3 Until recently the League was classified as a regionalist populist party (McDonnell, Citation2006) and AfD a populist radical right party based primarily on an anti-Euro agenda (Berbuir et al., Citation2015, p. 155). However, despite their initial diverse positions both parties have transformed since its inception, embodying classical radical right-wing issues regarding immigration, and law and order (Albertazzi et al., Citation2018; Arzheimer & Berning, Citation2019). In addition, these parties are often included in comparative analysis on radical right-wing parties (Mudde, Citation2007) and thus have been included in our analysis.

4 Gerring (Citation2008, p. 650) classifies a diverse case selection strategy as one that attempts to achieve: ‘maximum variance along relevant dimensions’ and ‘requires the selection of a set of cases – at minimum, two – which are intended to represent the full range of values characterizing X, Y, or some particular X /Y relationship’.

5 This strategy has been used only in two cases (i.e. The League 2019 and RN 2014) and it follows a consolidated tradition in party manifesto analysis (see the codebook of Schmitt-Beck, Citation2017, p. 8 and Werner et al., Citation2015, p. 3).

6 We assessed the inter-coder reliability of the results of the analysis, by following the approach of Rooduijn et al. (Citation2014). A sample based on English-language material was analysed. We used Krippendorff’s alpha on r to calculate reliability scores (R Core Team, Citation2017), using the nominal method. The reliability score was α =.882 which is satisfactory by usual standards (Krippendorff, Citation2004).

7 Quasi-sentence can be understood as the unit of textual analysis as an endogenous text fragment, an argument which is the verbal expression of one political idea or issue (Däubler et al., Citation2012).

References

- Albertazzi, D., Giovannini, A., & Seddone, A. (2018). ‘No regionalism please, we are Leghisti!’ The transformation of the Italian Lega Nord under the leadership of Matteo Salvini. Regional & Federal Studies, 28(5), 645–671. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2018.1512977

- Allen, T. J. (2017). All in the party family? Comparing far right voters in Western and post-communist Europe. Party Politics, 23(3), 274–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068815593457

- Anastasiou, M. (2019). Of nation and people: The discursive logic of nationalist populism. Javnost - The Public, 26(3), 330–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2019.1606562

- Art, D. (2020). The myth of global populism. Perspectives on Politics. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592720003552

- Arzheimer, K., & Berning, C. C. (2019). How the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and their voters veered to the radical right, 2013–2017. Electoral Studies, 60, 102040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.004

- Berbuir, N., Lewandowsky, M., & Siri, J. (2015). The AfD and its sympathisers: Finally a right-wing populist movement in Germany? German Politics, 24(2), 154–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2014.982546

- Betz, H.-G. (2017). Nativism across time and space. Swiss Political Science Review, 23(4), 335–353. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12260

- Betz, H.-G. (2019). Facets of nativism: A heuristic exploration. Patterns of Prejudice, 53(2), 111–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/0031322X.2019.1572276

- Bonikowski, B., Halikiopoulou, D., Kaufmann, E., & Rooduijn, M. (2019). Populism and nationalism in a comparative perspective: A scholarly exchange. Nations and Nationalism, 25(1), 58–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12480

- Breeze, B. (2018). Positioning “the people” and its Enemies: Populism and Nationalism in AfD and UKIP, Javnost - The Public.

- Brubaker, R. (2017). Between nationalism and civilizationism: The European populist moment in comparative perspective. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40(8), 1191–1226. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1294700

- Bundeswahlleiter. (2013, September). Wahl zum 18. Deutschen Bundestag am 22. https://www.bundeswahlleiter.de/bundestagswahlen/2013/ergebnisse.html

- Bundeswahlleiter. (2017, September). Wahl zum 19. Deutschen Bundestag am 24. https://www.bundeswahlleiter.de/bundestagswahlen/2017.html

- Canovan, M. (1999). Trust the people! populism and the Two faces of democracy. Political Studies, 47(1), 2–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.00184

- Charalambous, G., & Christoforou, P. (2018). Far-Right extremism and populist rhetoric: Greece and Cyprus during an era of crisis. South European Society and Politics, 23(4), 451–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2018.1555957

- Christiansen, F. J. (2017). Conflict and co-operation among the Danish mainstream as a condition for adaptation to the populist radical right. In P. Odmalm & E. Hepburn (Eds.), The European mainstream and the populist radical right (pp. 49–70). Routledge.

- Däubler, T., Benoit, K., Mikhaylov, S., & Laver, M. (2012). Natural sentences as valid units for coded political texts. British Journal of Political Science, 42(4), 937–951. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123412000105

- Day, G., & Thompson, A. (2004). Theorizing nationalism. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Decker, F. (2016). The “alternative for Germany:” Factors behind its emergence and profile of a new right-wing populist party. German Politics and Society, 34(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3167/gps.2016.340201

- De Cleen, B. (2017). Populism and nationalism. In C. R. Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. O. Espejo, & P. Ostiguy (Eds.), Oxford handbook of populism (pp. 342–365). Oxford University Press.

- De Cleen, B., & Stavrakakis, Y. (2017). Distinctions and articulations: A discourse theoretical framework for the study of populism and nationalism. Javnost - The Public, 24(4), 301–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2017.1330083

- De Cleen, B., & Stavrakakis, Y. (2020). How should we analyze the connections between populism and nationalism: A response to Rogers Brubaker. Nations and Nationalism, 26(2), 314–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12575

- Delwit, P. (2012). Le Front national et les élections. In P. Delwit (Ed.), Le Front national: Mutations de l’extreme droite francaise. Editions de l’Université de Bruxelles.

- Dyrberg, T. B. (2003). Right/left in the context of new political frontiers. Journal of Language and Politics, 2(2), 333–360. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.2.2.09dyr

- Ferreira, C. (2019). Vox como representante de la derecha radical en España: un estudio sobre su ideología. Revista Española de Ciencia Política, 5, 73–98. https://doi.org/10.21308/recp.51.03

- Freeden, M. (1998). Is nationalism a distinct ideology? Political Studies, 46(4), 748–765. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.00165

- Gerring, J. (2008). Case selection for case-study analysis: Qualitative and quantitative techniques. In J. Box-Steffensmeier, H. Brady, & D. Collier (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political methodology (pp. 645–684). Oxford University Press Inc.

- Glynos, J., & Mondon, A. (2019). The political logic of populist hype: The case of right-wing populism’s ‘meteoric rise’ and Its relation to the status Quo 1. In P. Cossarini & F. Vallespín (Eds.), Populism and passions: Democratic legitimacy after austerity. Routledge Advances in Democratic Theory. Routledge.

- Halikiopoulou, D., Nanou, K., & Vasilopoulou, S. (2012). The paradox of nationalism: The common denominator of radical right and radical left euroscepticism. European Journal of Political Research, 51(4), 504–539. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.02050.x

- Harmel, R., Svasand, L. G., & Mjelde, H. (2019). Institutionalization (and De-Institutionalization) of right-wing protest parties: The progress parties in Denmark and Norway. Rowman&Littlefield/ECPR Press.

- Howarth, D. R., Norval, A. J., & Stavrakakis, Y. (2000). Discourse theory and political analysis: Identities, hegemonies, and social change. Manchester University Press.

- Kaltwasser, C. R., Taggart, P. A., Espejo, P. O., & Ostiguy, P. (Eds.). (2017). The Oxford handbook of populism. Oxford University Press.

- Klemmensen, R., Binzer Hobolt, S., & Hansen, M. E. (2007). Estimating policy positions using political texts: An evaluation of the wordscores approach. Electoral Studies, 26(4), 746–755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2007.07.006

- Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage.

- Krisi, H., & Pappas, T. (2015). European populism in the shadow of the great recession (studies in European political science). ECPR Press.

- Laclau, E. (2005). On populist reason. Verso.

- Laclau, E., & Mouffe, C. (1985). Hegemony and socialist strategy: Towards a radical Democratic politics. Verso.

- Lauenstein, O., Murer, J. S., Boos, M., & Reicher, S. D. (2015). Oh motherland I pledge to thee … : A study into nationalism, gender and the representation of an imagined family within national anthems. Nations and Nationalism, 21(2), 309–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12123

- McDonnell, D. (2006). A weekend in padania: Regionalist populism and the Lega Nord. Politics, 26(2), 126–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9256.2006.00259.x

- Minkenberg, M. (2000). The renewal of the radical right: Between modernity and anti-modernity. Government and Opposition, 35(2), 170–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-7053.00022

- Mudde, C. (2004). The populist Zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

- Mudde, C. (2007). Populist radical right parties in Europe. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511492037

- Mudde, C. (2016). Europe's populist surge: A long time in the making. Foreign Affairs, 95(6), 25–30.

- Mudde, C. (2019). The Far right today. Polity Press.

- Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2013). Exclusionary vs. Inclusionary populism: Comparing contemporary Europe and Latin America. Government and Opposition, 48(2), 147–174. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2012.11

- Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2018). Studying populism in comparative perspective: Reflections on the contemporary and future research agenda. Comparative Political Studies, 51(13), 1667–1693. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414018789490

- Ostiguy, P. (2009). The High and the Low in Politics: A two dimensional political space for comparative analysis and electoral studies (No. 360). https://kellogg.nd.edu/sites/default/files/old_files/documents/360_0.pdf

- Passarelli, G., & Tuorto, D. (2018). La Lega di salvini: Estrema destra di governo. Il Mulino.

- Pytlas, B. (2018). Radical right politics in East and West: Distinctive yet equivalent. Sociology Compass, 12(11), 11. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12632

- R Core Team. (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Core Team. https://www.R-project.org/

- Reif, K., & Schmitt, H. (1980). Nine second-order national elections: A conceptual framework for the analysis of European election results. European Journal of Political Research, 8(1), 3–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.1980.tb00737.x

- Riedel, R. (2018). Nativism versus nationalism and populism – bridging the gap. Central European Papers, 6(2), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.25142/cep.2018.011

- Robertson, D. (2004). The Routledge dictionary of politics. Routledge.

- Rooduijn, M., de Lange, S. L., & van der Brug, W. (2014). A populist Zeitgeist? Programmatic contagion by populist parties in Western Europe. Party Politics, 20(4), 563–575. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068811436065

- Rooduijn, M., Van Kessel, S., Froio, C., Pirro, A., De Lange, S., Halikiopoulou, D., & Taggart, P. (2019). The PopuList: An overview of populist, far right, far left and Eurosceptic Parties in Europe. http://www.popu-list.org

- Rydgren, J. (2005). Is extreme right-wing populism contagious? Explaining the emergance of a new party family. European Journal of Political Research, 44(3), 413–437. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2005.00233.x

- Rydgren, J. (2010). Radical right-wing populism in Denmark and Sweden: Explaining party system change and stability. SAIS Review of International Affairs, 30(1), 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1353/sais.0.0070

- Schmitt, H., & Teperoglou, E. (2016). The 2014 European Parliament elections in Southern Europe: Secondorder or critical elections? South European Society and Politics, 20(3), 287–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2015.1078271

- Schmitt-Beck, R. (2017). The ‘alternative für deutschland in the electorate’: Between single-issue and right-wing populist party. German Politics, 26(1), 124–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2016.1184650

- Spencer, P., & Wollman, H. (1998). Good and bad nationalisms: A critique of dualism. Journal of Political Ideologies, 3(3), 255–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569319808420780

- Stavrakakis, Y., & Katsambekis, G. (2014). Left-wing populism in the European periphery: The case of SYRIZA. Journal of Political Ideologies, 19(2), 119–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2014.909266

- Stavrakakis, Y., Katsambekis, G., Nikisianis, N., Kioupkiolis, A., & Siomos, T. (2017). Extreme right-wing populism in Europe: Revisiting a reified association. Critical Discourse Studies, 14(4), 420–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2017.1309325

- Sutherland, C. (2005). Nation-building through discourse theory. Nations and Nationalism, 11(2), 185–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1354-5078.2005.00199.x

- Taggart, P. (2000). Populism. Open University Press.

- Turnbull-Dugarte, J. S. (2019). Explaining the end of Spanish exceptionalism and electoral support for Vox. Research & Politics, 6(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168019851680

- Valmyndigheten. (2018). valresultat. val.se: https://www.val.se/valresultat.html

- Van Kessel, S. (2015). Populist parties in Europe : Agents of discontent? Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vasilopoulou, S., & Halikiopoulou, D. (2015). The golden Dawn’s ‘nationalist solution’: Explaining the rise of the Far Right in Greece. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Werner, A., Lacewell, O., & Volkens, A. (2015, February). Manifesto coding instructions (5th rev. ed.). MARPOR. https://manifestoproject.wzb.eu/down/papers/handbook_2014_version_5.pdf

- Wodak, R., KhosraviNik, M., & Mral, B. (2014). Right-Wing populism in Europe. Bloomsbury.

- Ypes. (2012). Αποτϵλέσματα Εθνικών Εκλογών Μαϊου 2012. http://ekloges-prev.singularlogic.eu/v2012a/public/index.html#{%22cls%22:%22main%22,%22params%22:{}}

- Ypes. (2015). Αποτϵλέσματα Εθνικών Εκλογών Σϵπτϵμβρίου 2015. http://ekloges-prev.singularlogic.eu/v2015b/v/public/index.html#{%22cls%22:%22main%22,%22params%22:{}}

- Zaslove, A. (2004). The dark side of European politics: Unmasking the radical right. Journal of European Integration, 26(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.1080/0703633042000197799