ABSTRACT

After the 2019 European Parliament (EP) election, the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) party grouping experienced a major change in its representation and leadership, with the wholescale departure of its core British Conservative MEPs. Yet the ECR remained an important and coherent transnational party federation in Strasbourg, acting as a strong voice for conservatism in Europe as distinct from Christian Democracy and the radical right. With large numbers of MEPs from Poland’s Law and Justice (PiS) party within the grouping, there was also much continuity with policies that were opposed to ‘ever closer union’, in favour of business and the single market and also of the wider role of the USA and NATO in international relations. Often written off as merely a ‘Eurosceptic’ faction, the start of the 2019–2024 EP session saw the grouping consolidate its influence and profile in EU affairs as a distinctive right-of-centre party in the Hemicycle.

Introduction

Not for a long time was a party grouping in the European Parliament (EP) perceived so differently by so many commentators and analysts. By their own account, the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) were a centre-right grouping founded by the British Conservatives, unashamedly promoting free market economics in domestic politics and a strong role for NATO and the USA in international relations (European Conservatives and Reformists group, Citation2020). To others, however, the ECR was a far right - or at the very least ‘right wing’ - faction with unpalatable members such as the Sweden Democrats (SD) and held together since the 2019 elections by Poland’s at times controversial Law and Justice (PiS) party (see McDonnell and Werner 2019). So, what was the real ECR? In our view, both interpretations represent over-simplifications. Regardless of this, studies of the ECR make a new contribution to the political science scholarly literature on the political right, conservative and Christian Democratic parties in Europe. Our work builds on the earlier pioneering article by Bale et al. (Citation2010) and subsequent monograph by Steven (Citation2020), both of which have attempted to develop more nuanced approaches to understanding the ideological nature of the ECR. The very existence of the ECR - and indeed its growth and expansion over a decade since 2009 - was a powerful statement about the differences between contemporary Western European Christian Democracy and the ‘Anglo-American’ brand of conservatism (see Mair, Citation1990).

It was Von Beyme’s development of the influential concept of ‘familles spirituelles’ which represented perhaps the first sustained attempt to identify Conservatism as being a distinct party family from both Christian Democracy and the radical right within the context of West European politics (Von Beyme, Citation1985). This institutionalist approach, where parties are regarded as being path dependent on their historical origins, continues to provide an extremely useful framework for thinking about European politics comparatively. While it has been criticised since for being too ‘one dimensional’ where clearly modern political parties are blurred at the edges in real life, the existence of the ECR is a very powerful confirmation of Von Beyme’s analysis of the different dynamics of European party politics (see also Ware, Citation1996). While no true consensus in the scholarly literature exists over what it actually means to be ‘right’ or ‘conservative’ due to differences in definitions and perceptions (see Garnett, Citation2018), much has been written about the practical distinction between ‘Anglosphere’ Conservatism and Western European Christian Democracy in reality. Ultimately, Christian Democrats in Germany, Belgium and The Netherlands are much less hostile to the role of the state in the private sector in domestic politics and much less enthusiastic about free market economics than, for example, British Conservatives or American Republicans. As well as making an empirical contribution on an under-researched case, this paper thus adds a whole new dimension to the theoretical debate started by Von Beyme, and developed further by Mair (Citation1990) on the ideological differences between Christian Democracy and Conservatism. This analysis therefore fills an important gap in the political science literature on the contemporary nature of Conservative politics in Europe.

Related to all of this is the puzzle about the different factors and reasons that lay behind the ECR’s electoral success in Strasbourg in three successive EP elections (2009, 2014 and 2019). Ultimately, was the grouping merely an expedient vehicle for first the British Conservatives and then Law and Justice of Poland to utilise along with other like-minded politicians in order to organise their MEPs in the European Parliament (EP) without having to come to a less convenient deal with the still dominant European People’s Party (EPP)? Or was such an interpretation overly cynical? In fact, was the ECR ultimately a constructive platform for traditional conservatives who shared an ideological distaste for ‘ever closer union’ in Europe and who truly believed in the benefits of free market capitalism, trade and business activities? In other words, did the ECR merely exist for short-term instrumentalist reasons revolving around the insular world of Brussels and Strasbourg policy circles or rather was it actually a longer term, better intentioned enterprise than that, with a deeper set desire to act as a voice for ‘Anglo-American’ style freedoms throughout the EU?

In order to explore and pull out the evidence as to whether the ECR was not simply a short-term vehicle for right-wing Euroscepticism but ultimately more than simply a non-descript ‘empty vessel’ into which new Central European wine was subsequently poured, this paper examines a number of key aspects of the ECR’s ideology and programmatic approach. To get at this, a core objective of this paper is to examine whether the ECR has a coherent conservative ideology underpinning it. Although the paper also contributes to the broader literature analysing the development and role of European trans-national party federations (TPFs) and ‘Europarties’ (see Hertner, Citation2018; Hix et al., Citation2007; Jansen & Van Hecke, Citation2011; McElroy & Benoit, Citation2010), its primary contribution is to examine this EP grouping as an attempt to carve out a distinctive conservative ideological space within the EU and broader European party family spectrum. In this sense, the analysis also builds on the work of Leruth (Citation2016) and McDonnell and Werner (Citation2018), both of whom identify that the ECR is a party grouping within the Parliament worth studying in the longer term. Crucially, however, these studies choose to mainly accentuate the ‘Eurosceptic’ nature of the ECR rather than its small state ‘conservatism’.

We begin by reviewing the changes in the composition of the ECR that occurred as a result of the 2019 EP elections and departure from the grouping of the British Conservative party following the UK’s withdrawal from the EU in January 2020. We then move on to examine the grouping’s ideological profile and trajectory in a number of key policy areas, particularly its approach towards: European integration (which might be termed ‘Eurorealist’); trans-Atlantic relations and international relations more generally; free markets, business and trade; and, finally, what might be labelled ‘family values’ and social issues.

Our central contention is that it is wrong to suggest that the ECR existed merely for expedient reasons linked to forming factions in the EP and that, for better or worse, the grouping was part of a much bigger, more ambitious project to promote ideological conservatism in European public affairs. Our argument is not just that the ECR seeks to function in a conservative manner in the EP, but also aspires to represent Conservatism on a Europe-wide basis; although these two aspects are clearly linked. As it was mentioned earlier, although this paper does add to the trans-national party federations (TPFs) literature (see Hertner, Citation2018; Hix et al., Citation2007; Jansen & Van Hecke, Citation2011; McElroy & Benoit, Citation2010), our key point is that the ECR is not simply a TPF but a wider vehicle for promoting Conservatism across Europe. As our objective is to provide an overview of the ECR to offer an introduction to the group’s under-researched parliamentary activities, we have deliberately adopted a qualitative approach rather than attempting to quantify all of its policy positions statistically.Footnote1

The ECR and the 2019 European Parliament elections

As shows, after the 2019 EP elections the ECR had 64 Members of the European Parliament (MEPs), making it the sixth largest grouping after the EPP, the social democratic Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in Europe (S&D), the liberal ‘Renew Europe’ (RE), the Greens (Greens-EFA) and the radical right ‘Identity and Democracy’ (ID). If that sounds like a relatively modest achievement, it ought to be placed within the context of wider European party systems. Four of the five party groupings with more MEPs than the ECR had been in existence for significantly longer - the Christian Democrats, Social Democrats, Liberals and Greens had all been active in Strasbourg politics since either the late 1970s or the early 1980s while the ECR was only formally founded ahead of the 2009 elections. Indeed, at the 2014 elections, the ECR emerged as the third largest grouping, holding the status of ‘king maker’ in the Parliament until the 2019 elections, and displacing the liberals (then known as ‘ALDE’ - the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe) from their previously central position. Moreover, it was widely assumed that, after Brexit (the UK leaving the EU), the grouping would simply fold, given how vital the British Conservative party had been in setting it up and providing it with resources. For the ECR, then, to actually perform relatively solidly in 2019, and continue to be able to form a recognisable grouping in Strasbourg for the third consecutive parliamentary session, was a solid achievement.

Table 1. EP political groupings by number of MEPs after the 2019 EP elections.

In fact, all the signs were ahead of the 2019 elections that the ECR was in any case a longer term project than many had realised, with perhaps two key elements to this. First the ECR Party, the wider umbrella grouping (or ‘Euro party’/transnational party federation) that included member parties from across Europe and not just EU-27, always had a much broader remit to promote conservatism across policy areas (see also Hix et al., Citation2007; McElroy & Benoit, Citation2010). Its President for ten years was Jan Zahradil, the Czech Civic Democrat (ODS) MEP, who demonstrated a consistent desire to stand up for free market economics and the role of NATO and America in international relations. He had been clear that while the British Conservatives had undoubtedly been the ‘backbone’ of the ECR since the 2000s, the departure of their MEPs did not simply signal the end of the ECR. Conservatism, in his view, was a recognisable political ideology and a mainstream set of values that should have its own party grouping in Strasbourg regardless of the nuances of Brexit (Interview with author, Brussels, 2 March 2017). Indeed, Czech Civic Democrat political figures were highly instrumental in the origins and development of the ECR since the 2000s and their levels of representation also increased somewhat in 2019 having enjoyed something of a mini-electoral revival domestically in the Czech Republic, where they also returned to government in 2021.

Second, Poland’s Law and Justice (PiS) party was also central to the development of the ECR since the start, and unlike the Civic Democrats, also had a large contingent of MEPs to provide something of a counter balance to the influence of the British Conservatives. As shows, while the 2019 EP elections were disastrous for the British Conservatives even before Brexit was completed in January 2020 with a substantial loss of MEPs, they were a success for Law and Justice who comfortably emerged as the largest party in Poland with a 45% vote share despite having been in office for the previous four years. Very healthy numbers of Polish Law and Justice MEPs were returned, making up the shortfall of British MEPs to some extent at least. While there were undoubtedly differences between Law and Justice and the British Conservative party, there were also clear similarities too, especially with regard to their view of the purpose of the EU overall and also the role of NATO and the USA in international relations – which, as we shall see, within the context of EP, were more than sufficient to provide an intellectual continuity as well as clarity of messaging.

Table 2. Largest parties in the ECR grouping after the 2019 EP elections.

Table 3. Percentage of MEPs from CEECs by EP party grouping after the 2019 EP elections.

So did the ECR merely exist for pragmatic reasons revolving around the necessities of parliamentary group formation in Strasbourg or rather was it actually a longer term enterprise than this? When answering this fundamental question, the 2019 EP elections significantly updated the case study with regard to evidence and context and ought to allow for an even more nuanced and in-depth analysis of the ECR. If the ECR was led and dominated by MEPs from the Law and Justice – at the time of writing, still Poland’s ruling party - there lay a question mark over how its leadership could claim to be the same party grouping at all as the one previously dominated by the British Conservatives? One answer to the question would be that the 2019- 2024 ECR was completely different from the 2014–2019 ECR and shared only its name and blue lion party logo. Therefore, it might also be straightforward to conclude briefly that ECR was the perfect embodiment of the ‘empty bottle’ model of political parties into which new wine could be poured to provide electoral refreshment (see Katz & Mair, Citation1994).

However, it will be argued in this paper that there was actually much more continuity between the Conservative-led ECR and the Law and Justice-led ECR than perhaps meets the eye of the casual observer - and that ultimately the ECR party remained an under-researched (both theoretically and empirically) and at times misinterpreted transnational party federation. In doing so, as noted above, this paper moves forward and brings a new dimension to theoretical debates about the ideological differences between European Christian Democracy and Conservatism. To argue that ECR only existed because the British Conservatives saw an electoral advantage in not being in the EPP or to argue that it existed subsequently because Law and Justice had a similar aversion to the Christian Democrats, is too simplistic. Clearly, there was a much deeper mission that drove the ECR forward. Its overall MEP total may have been slightly lower after the departure of UK MEPs from the Parliament but, given that the grouping was predicted to collapse altogether after Brexit, it remained a significant vehicle in Strasbourg in the 2019–2024 session. Its underlying organisational apparatus remained intact, as did aspects of its core leadership, with MEPs from Poland and the Czech Republic continuing to play a key role as they did from the early stages of the grouping’s development. The ECR has long-established headquarters situated on Rue de Trône in central Brussels, in close proximity to the Parliament. Many of the staffers who work here are long-serving while the group’s bureau features highly experienced figures such as Jan Zahradil (ODS), Karol Karski, Zdzislaw Krasnodęsbski (both PiS) and Johan Van Overtfeldt (N-VA).

The first year of the 2019–2024 era saw the ECR continue to use its still healthy representation in Strasbourg for similar purposes to the British-led 2014–2019 version - resisting a federal EU, and pushing for greater sovereignty for member states while equally protecting what it perceived to be the undoubtable benefits of the EU single market, trade and free movement of people and services (see European Conservatives and Reformists group, Citation2020). A recognisably ‘Anglophile’ conservative agenda emphasising, as the ECR saw it, the inherent value of freedom was enthusiastically promoted by its 64 MEPs albeit with a more overtly socially conservative Central European undertone to the fore in its policy literature and online documents.

It is important to also remember that Law and Justice was not a new national delegation to the ECR in any way - it always had a similar number of MEPs to the British Conservatives and, in addition to this, advocated a strong role for the USA in international relations, and the importance of the related activities of NATO. Poles, according to social attitudes surveys, may have been sceptical of both Germany and Russia in geo-politics but looked much more favourably upon the influence of both the UK and the USA (European Council on Foreign Relations, Citation2018). Indeed, during the term in office of US President Donald Trump, the Law and Justice-led Warsaw administration was one of his closest ideological allies. In fact, Law and Justice would have been proponents of a strong transatlantic relationship regardless of who sat in the Oval Office, although it was clear that leading Law and Justice figures particularly embraced Mr Trump’s anti-(liberal) establishment style as one that they also aimed to promote within Poland (Poland in, Citation2020). Within this context, the ECR remained an important Europe-wide organisation through which such values and interests could be advanced at a supra-national level.

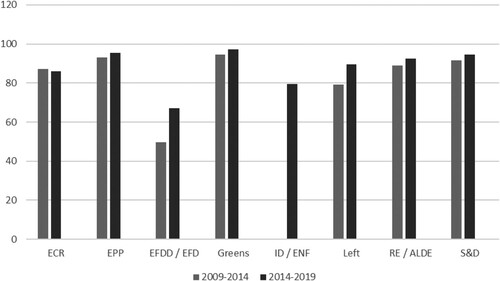

Even taking into account the fact that the whipping system in Brussels/Strasbourg is relatively loose, the ECR’s approach to voting and law-making in the Parliament remains distinct. Importantly, the ECR is the only group that does not actively whip its MEPs. At group meetings, ahead of plenary sessions, the group chief whip simply asks for a show of hands to establish what the formal position will be and even then, if a national delegation or individual MEPs wishes to dissent, there is no censure process (see interviews with Ulrike Trebesius MEP, Strasbourg, March 2019 and Daniel Dalton MEP, November 2017). This is justified on the grounds that the ECR does not believe in centralised EU decision making and respects the autonomy of its member parties. Despite this, the ECR’s cohesion rates in both the seventh and eighth sessions of the European Parliament are actually comparable with those of the other main party groupings. As shows, the level at which ECR MEPs vote together in the Hemicycle is not substantively different from the way MEPs from other groups vote, and indeed is noticeably better than the cohesion rates of MEPs from the radical right or hard Eurosceptic factions.

Figure 1. Roll call voting cohesion amongst party groups, 2009–2019 (%) Sources: European Parliament; VoteWatch Europe; Fondation Robert Schuman.

Moreover, as we shall see, throughout the ECR’s policy positions, a very strong sense comes through of the grouping trying to project a consistently conservative approach to public affairs - no matter what the policy is, one can be sure that the ECR’s positions have attempted to adopt what they would see as a cautious, as they saw it, ‘common sense’ traditionalist approach without necessarily being moderate or centrist. In other words, unlike the Christian Democrats, the ECR MEPs had no interest in triangulating and providing ‘all things to all people’ and always winning votes from both the left and right. However, equally, ECR leaders were often unhappy to be accused of being radical or revolutionary in the way that an explicitly insurgent radical right politician would not necessarily recoil instinctively from, and possibly even bask in. According to the ECR leader in the EP at the time of writing, Law and Justice MEP Ryszard Legutko (a well-known scholar of conservatism working at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków), his party’s MEPs were inherently comfortable with being associated with the term ‘conservatism’ (Interview with author, Brussels, 28 November Citation2017), as well as related descriptions such as ‘centre-right’ or ‘right-of-centre’.

For sure, we accept that some of the ECR’s member parties appeared to be more closely aligned with the radical right. For example, from 2014–2019 the grouping included the Finns (PS) and the Danish People’s Party (DF) – and, since the 2019 elections, the Sweden Democrats, Vox from Spain and the Dutch Forum for Democracy (FvD) were all signed-up national delegations, as were the Brothers of Italy (FdI), a political party with openly fascist roots. Indeed, in September 2020, Brothers of Italy leader Giorgia Meloni was also elected the new president of the wider ECR Party network, replacing the long serving libertarian ‘Thatcherite’ Czech MEP Jan Zahradil, although this role does not have a direct impact on the leadership of the group in the EP. Nevertheless, there remains a substantive difference between a group in the European Parliament allowing a party with extremist positions to join its faction and the composition of the formal leadership of the group which takes decisions about which policy positions to adopt.

Indeed, moreover, EP parliamentary groupings have always been broad churches and all factions have within them controversial member parties. For example, until recently the Fidesz grouping - Hungary’s governing party at the time of writing, and much maligned (along with Law and Justice) for its alleged ‘illiberalism’ – was an EPP member, while the liberal ‘Renew Europe’ grouping included the Czech ANO 2011 grouping led by the controversial businessman-politician (and, at the time of writing, prime minister) Andrej Babis. However regardless of this, in our view, while we fully concede that these are potentially anomalous parties, this ought to not ultimately conceal the wider points about ideological coherence and the longer term policy proposals advanced by the ECR grouping that we will develop in the rest of this paper.

Eurorealism

In terms of its approach to European integration, the ECR’s ‘Eurorealism’ may not have been an especially profound political philosophy - indeed, it would probably have horrified some of its elected representatives to even contemplate the idea that they had come up with a new political idea, sceptical as they were of anything ‘radical’ or ‘intellectual’ (Interview with senior group staff, 5 November 2018)! Nevertheless, the term does a reasonable job of encapsulating the consistently Soft Eurosceptic position (see Szczerbiak & Taggart, Citation2008) that all its national delegations signed up to since its inception. ECR politicians could be considered sincere when they argued that, while they wished to reform the EU, and had no desire to destroy it. For British Conservatives, that ultimately stemmed back to Churchill’s view of European integration - that some sort of ‘United States of Europe’ had to be created but not necessarily with Britain always being an active part of it (Churchill, Citation1946). ‘Eurorealism’ was, formally at least, a ‘third way’ in its attempts to chart a middle course between ‘ever closer union’ and the collapse of the EU altogether (see European Conservatives and Reformists group, Citation2020).

For MEPs from Law and Justice, that stemmed from a genuine desire to be part of the European project but not to the extent that they felt that Poland’s sovereignty was compromised yet again. That stance on European integration did - for better or worse - place the ECR somewhere in the middle of the spectrum between the ‘ever closer union’ advocates of the Christian Democratic EPP and the anti-globalisation position of the more explicitly radical right groupings. Both the British Conservatives and Law and Justice politicians offered an intellectually consistent alternative to the current model of the EU - an international order based on rules and co-operation with a leading role for the USA and NATO rather than obsessing, as they would see it, with creating a European ‘super-state’. The 2019 EP elections did not change that. Although the Polish government was increasingly frustrated with the EU political establishment - following repeated clashes with the European Commission, EP and major European powers - Law and Justice MEPs had no desire for Poland to leave the EU or for the EU to disappear altogether. Rather, they wanted to use the ECR as a coherent vehicle in Brussels and Strasbourg to advance their own agenda and interests. However, they were also clear - and as clear as any British Conservative Eurosceptic - that this should not come, as they saw it, at the cost of sovereignty or national independence.

Ultimately, post-2019, the ECR’s position on European integration remained akin to such Soft Euroscepticism, or ‘Eurorealism’ as its MEPs would have it, and this was a distinctive stance to adopt amongst the EP groupings. The EPP, Socialists and Democrats, ‘Renew Europe’ and Greens could all have been characterised as un-ambiguously ‘pro-EU’, in the sense that they believed passionately in the benefits of deeper European integration through the EU and ‘ever closer union’. Meanwhile, the radical right ‘Identity and Democracy’ faction was Hard Eurosceptic (see Szczerbiak & Taggart, Citation2008) and unashamedly advocated a complete dismantling of the structures of the EU in principle (Identity and Democracy, Citation2020). The ECR’s position - to praise aspects of European integration but to call for greater autonomy for member states - remained a ‘unique selling point’ that its MEPs could try to advance via their campaigns, speeches and other political activities. Indeed, it also fitted neatly with the grouping’s conservative agenda of smaller states trading independently with each other. ‘Eurorealism’ could, thus, be said to articulate effectively and originally the antipathy of European conservatives towards ‘ever closer (political) union’ while, at the same time, communicating their sympathy for the more economic aspects of European integration.

Moreover, ultimately, both Poland’s Law and Justice and the British Conservatives approached the question of how European integration ought to function from similar perspectives. The British Conservative Party always adopted a ‘cost-benefit’ approach to what was the European Community, and the Common Market prior to the Maastricht Treaty - if it was good for the UK economy to be a member of the EEC (European Economic Community) then that was what ought to happen, it was argued at the time by party leaders (see Churchill College Cambridge party archives). Similarly, Law and Justice MEPs put forward an equally ‘Poland first’ type of strategy: Poland should be very much a member of the EU but not to the extent that the interests of the EU were placed ahead of those of Poles (Szczerbiak, Citation2018). Ultimately, the EPP, Socialist and Democrats, ‘Renew Europe’ and Green politicians were always wary of criticising the EU, believing it to be an inherent good in and of itself, whereas both British Conservative and Polish Law and Justice MEPs did not back away from displaying their ‘patriotic’ credentials within the context of the EU.

Indeed, if anything, it appeared that the post-2019 ECR would be even more ‘Eurorealist’ than the 2014–2019 version as its motivations could not be as easily questioned as those of the UK Conservatives. Prior to the 2019 EP elections, an important accusation that was made against the grouping was that it was really just a short-term expedient way for Eurosceptics in the British Conservative Party to make a symbolic gesture that they did not wish to be part of the Christian Democratic EPP (Whitaker & Lynch, Citation2014). Subsequently, however, the heavily CEEC-dominated ECR developed a more openly sincere position - Law and Justice and the Czech Civic Democrats contained amongst their ranks many politicians who genuinely believed in the benefits of the European single market but who also wanted to see the EU reformed so that, as they saw it, it respected the sovereignty of member state borders, including those Visegrad states with a different experience of European integration from longer serving countries in Western Europe.

While the prospect of Brexit hovered over the activities of the ECR for much of its relatively short life span, the prospect of Poland leaving the EU altogether (‘Polexit’) was much less likely. In the UK, a substantial cross-section of the electorate, especially those parts located in the provincial regions of England and Wales, had become sympathetic towards the prospect of leaving the EU altogether and, as they saw it, the country regaining its ‘independence’. Similar polling in Poland did not reflect that type of sentiment and there was no incentive for Law and Justice to try to exploit such a view for electoral gain (Chryssogelos, Citation2019). After the 2016 British referendum, Law and Justice leader Jarosław Kaczyński stated that is ‘obviously a very bad event’ and that ‘Poland’s place is in the EU regardless of the result of the vote in Britain’ (Chapman, Citation2020). ‘Euro realism’ may have been developed originally in London but it appeared to find its true home in Warsaw and Prague and, for that reason, it was expected that the 2019–2024 parliamentary session would see the ECR grouping cement its solid position even more within the corridors of power in Strasbourg.

Atlanticism

At the same time, after the 2019 EP elections, the ECR remained the most overtly pro-American grouping in the EP. ECR MEPs were strong advocates of the role of the United States in geo-politics and the related role of NATO in international relations and security (European Conservatives and Reformists group, Citation2020). While the leadership of the ECR changed from the British Conservatives to Law and Justice, a proud Atlanticism remained - and, indeed, was strengthened. In the case of the British Conservatives, this trans-Atlantic stance was rooted in ‘Anglo-sphere’ values related to an enthusiasm for free market economics and a cultural aversion to too overbearing a state. In the case of Law and Justice, the affection for the United States had its origins in the recent history of twentieth century Europe, the Cold War, and an antipathy towards both a perceived overly-aggressive Russia and an alleged overly-dominant Germany.

Europe-US relations had, of course, been intimate for many decades, and their relationship was especially close politically after the end of the Second World War and during the period of the Soviet domination of Eastern Europe. All mainstream EU leaders, such as President Emmanuel Macron of France and German Chancellor Angela Merkel, were formally in favour of a strong USA and a continued role for NATO in global politics. Nevertheless, in reality, the relationship between the EU and the US was at times strained and there were clear cultural differences between the European and American political mainstreams that emerged periodically, with some more significant than others. Mr Macron, for example, made it clear that he wanted to see the development of a European army (European Defence Union) advance apace and had concerns about France and Germany becoming overly reliant on the USA for its military security (French Ministry for Foreign Affairs, Citation2017). ECR MEPs, on the other hand, were very critical of this proposal to create a European Union army - instead, they wanted to see NATO strengthened and refreshed, feeling that Russia remained a geo-political threat especially with regard to ongoing energy and military security (European Conservatives and Reformists group, Citation2021). Mr Macron also possessed a traditional French aversion to political and economic terms such as ‘liberal’ and ‘conservative’. Relations between Germany and the USA, meanwhile, became cooler due to personal antipathy between Chancellor Merkel and President Donald Trump (Spetalnick & Nichols, Citation2020). ECR MEPs, on the other hand, were less nervous about these geo-political dimensions and wanted to see the trans-Atlantic alliance continue well into the twenty first century.

The leadership of the ECR was also much warmer and more positive about the election of Donald Trump as US President in 2016. While there may have existed a range of views about Mr Trump on a personal level, within the ECR overall its leadership showed a determination to give him a chance and to not simply write him off as a ‘populist’ novice. In the week leading up to the 2020 Polish presidential election, Law and Justice-backed incumbent Andrzej Duda, a former MEP himself, was invited to the White House in Washington for an official meeting to show the symbolic strength of the relationship between Poland and the USA (BBC News, Citation2020). During the 2020 US presidential election, the ECR formally endorsed Mr Trump’s candidacy, and actively supported his campaign via its online platforms (European Conservatives and Reformists party, Citation2020). This was perhaps not quite as controversial or ‘inappropriate’ as it sounds as the Republican Party was formally affiliated to the wider ECR movement as a sister organisation.

Moreover, the ECR grouping was also by far the most enthusiastic faction in Strasbourg with regard to the TTIP initiative (Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership) - they lobbied heavily for its completion prior to its suspension in 2017 and remained committed to any policy that strengthened ties between the USA and Europe (European Conservatives and Reformists party, Citation2020). TTIP was relegated primarily due to Mr Trump’s inherent suspicion of some aspects of global trade and his ‘America first’ policy but even prior to 2016, the trade negotiations also had a very controversial political element due to a shared wariness of it amongst more left-wing MEPs. In this sense, the ECR’s commitments to an EU that was less centralised and technocratic, more closely associated with the values of the USA, and more enthusiastic about free market capitalism, trade and a small state, all complimented each other and looked set to continue in the 2019–2024 EP session.

Free markets, business and trade

The 2019 EP elections also did not alter the ECR leadership’s predilection for free markets, business and trade - and again, in a way that gave the grouping a distinctive position compared with both the EPP and more radical right groupings such as ‘Identity and Democracy’. For the former, the market was seen as good but needed to be regulated – centre-right politicians in France, Germany and other parts of Western Europe have traditionally support a so-called European Social Model (ESM) of political economy that envisaged a large role for the government and trade unions in economic management. Meanwhile, radical right politicians in Europe tended to be less interested in issues relating to trade and financial institutions, and more concerned with questions of immigration, culture and social affairs. The senior Czech MEP Jan Zahradil performed a key role for the ECR here, acutely aware that the ECR appeared to fill a gap in the ideological spectrum by offering a Thatcherite/‘Reagonomics’ view of public affairs that was not supported by either Christian Democrats or the radical right (Interview with author, Brussels, 2 March Citation2017). For sure, this did not necessarily mean that every single ECR (indeed, especially not Law and Justice) MEP was a passionate free marketer but it did result in the formal policy positions of the grouping being clearly right-of-centre on questions surrounding the respective role of the state and the private sector in the economy and the perceived wider benefits of the European single market.

For certainly, given its huge social welfare programmes and fiscal transfers and promotion of Polish capital and state intervention in what it saw as key strategic sectors, Law and Justice MEPs were hardly synonymous with free market capitalist economics at home in Poland. Nonetheless, in the context of the EU and EP, they were enthusiastic supporters of the European single market with regard to Polish products, services and citizens being able to move freely around the European continent in an unhindered way that radical right politicians from France, Italy and Germany did not so consistently support due to their protectionist instincts (Law and Justice, Citation2019). In fact, Law and Justice was often a difficult party to pin down socio-economically and more unambiguously ‘right-wing’ in terms of its social conservativism on moral-cultural issues surrounding Polish nationhood, and its commitment to a promoting a traditional model of the family and conservative Christian values in public life. Nevertheless, within the context of EU politics and the EP, its MEPs were entirely happy to be part of a faction that sought to further deepen the single market economically without necessarily advancing ‘ever closer union’ politically. Indeed, Law and Justice politicians and supporters were equally critical of a type of ‘crony capitalism’ where old elites monopolised certain sectors; their portrayal of the kind of economic system that (they argued) had developed in post-communist Poland and (they claimed) they were trying to reform (Law and Justice, Citation2019).

Thus, in addition to their recognisable stances on European integration and wider international relations, ECR MEPs were also often distinctive voices for free market capitalism, global trade and business activities within the EP. They were strong advocates for the completion of the single market in as many sectors as possible and opening up trade between the EU-27 with minimal barriers. In this sense, they were true to their distinctively conservative identity, which reflected a fairly classical economically liberal position on the role of the state in relation to the private sector and other issues related to the distribution of wealth in society. This brand of conservatism could be contrasted with the European Social Model (ESM) or social market economics that had traditionally been found in Western European states such as France and Germany (Erhard, Citation1958). Conservatism’s natural home on the other hand tended to be the ‘Anglosphere’ or English speaking countries such as the UK, US, Canada and Australia.

Indeed, through its leadership in particular, many ECR politicians valued their ability to be an unashamedly right-of-centre party grouping with regard to economics. Jan Zahradil, the ECR Party President from 2010 to 2020, was a member of the Czech Civic Democratic Party, which explicitly modelled itself on conservative parties in Britain, North America and Australia (Hanley, Citation2007). Mr Zahradil was a close disciple of former Czech President and university economics professor Vaclav Klaus, who - in his role as Czechoslovak finance minister and then Czech prime minister - was the architect of the country’s transition from a centrally planned to a free market economy, and was even described at the time as the ‘Margaret Thatcher of Central Europe’ (Boyes, Citation2009). Civic Democrat MEPs, while not as large in number as Polish Law and Justice representatives, were nevertheless extremely influential in the development of the ECR EP grouping and its wider ‘Euro-party’ from the early 2000s. Although the British Conservative Party no longer had MEPs in Strasbourg after 2020, its influence lived on via the activities of the wider ECR party and its high profile enthusiasm for a strongly free market model of capitalism.

Linked to this, it was not a coincidence that both during the 2014–2019 EP session – and, again, from the start the new 2019–2024 session – the ECR grouping held the chair of important economic-orientated committees related to the EU single market. Anneleen Van Bossuyt MEP was chair of the Internal Market Committee from 2014–2019 while Johan Van Overtfeldt became chair of the Budget Committee after 2019. Both these politicians were MEPs from the New Flemish Alliance (N-VA), the largest political party in Belgium at the time of writing and, like the Czech Civic Democrats, enthusiastically in favour of business, trade and a small state (see Leruth, Citation2016). Since their first election back in 2009, ECR MEPs quietly built up something of a reputation for themselves as being the main voice of free market economics in Strasbourg and Brussels which allowed the grouping to work closely with the EPP and ‘Renew Europe’ MEPs and which, helpfully for them, did not attract the same level of controversy or acrimony as their Soft Euroscepticism or ‘Eurorealism’.

During the 2014–2019 session in particular, the EP’s committee work was affected substantially by the activities of ECR MEPs with regard to business and trade affairs. According to the British Conservative MEP and former chief whip Daniel Dalton, it represented major progress for a conservative approach to the economy that on each committee EPP MEPs were joined by similarly right-of-centre orientated ECR MEPs (Interview with author, 20 November 2017). This resulted in policy issues related to the single market being discussed and debated by twice as many politicians from the right of the political spectrum as before, meaning that the policy outcomes were also more likely to be favourable to a ‘conservative’ way of thinking than had previously been the case when the EPP was really the only right-of-centre party EP grouping attending the different stages of policy-making and law-making. Indeed, as below shows, the ECR was by far the most coherent group in the first three years of the ninth Parliament (2019-2021) when it came to roll call votes on free trade, and by far the most consistently enthusiastic.

Table 4. Roll call voting cohesion amongst party groups on Free Trade, 2019–2021 (%).

Finally, it should be noted that the ECR’s interest in what it saw as protecting the private sector from state interference was, in and of itself, explicitly linked to its ‘Eurorealism’ and not a mere ‘add-on’. In the same way that ECR politicians disliked too large a role for the state in domestic politics, they were equally sceptical of the need for a large, over-reaching EU at a supranational level. Their position was consistent in this regard and explains why the grouping had considerable affection for the EU’s trade policies but much less for the concept of political union (‘free market, free countries, free people’ as they would have it’, European Conservatives and Reformists party, Citation2020). While covering different issues, the ECR’s Euro-realism, its Atlanticism and its advocacy of the need for a small state, all originated in the same conservative place, and that did not change fundamentally simply because of Brexit or the fact that its largest national delegation became Poland’s Law and Justice party.

‘Family values’, Christianity and immigration

Lastly, policy areas surrounding what is sometimes called ‘family values’ and wider social issues such as religious freedom and immigration may perhaps have appeared less central to the business of the EP - and, indeed, specifically to the ‘Eurorealist’, free market-orientated ideas of the ECR - than, for example, international relations and global trade. Nevertheless, it is clear that such issues did form an important part of the grouping’s distinctive identity in Strasbourg, and not simply because, after Brexit, Law and Justice became the largest party within the ECR transnational party federation. Indeed, on social affairs, the 2019–2024 version of the ECR appeared likely to continue to try and carve out a middle ground on the right-of-centre with regard to issues such as the role of religion and the family in society.

In fact, even prior to the 2019 elections when Law and Justice became the largest party within the ECR, the grouping’s MEPs were clear voices in the Hemicycle with regard to social issues such as freedom of religion, as well as the importance of what the pre-eminent scholar of religion in public life, Robert Putnam, has termed old-fashioned ‘social capital’ (Citation2000). Once again, there was continuity here between the 2014–2019 and 2019–2024 sessions. Indeed, in many ways, the ECR’s mixture of free market capitalism and social conservatism came across as a modern, updated version of 1980s British ‘Thatcherism’. Conservative prime minister from 1979 to 1990, Margaret Thatcher revolutionised the British economy, moving it away from a reliance upon traditional heavy industries and manufacturing and towards becoming more service-orientated and centring around financial services in the City of London. She also famously enjoyed a very close personal friendship with Ronald Reagan, the Republican US President from 1980 to 1988, who together were often regarded as conservative ‘kindred spirits’. Even at the time of writing, more than 30 years on, public opinion within the UK remained extremely divided and polarised over whether or not there was a need to make such radical sweeping changes to the British economy and society in the 1980s, although the 1970s had been an unquestionably difficult period for the UK with regard to economic decline and, at times, social unrest. Indeed, these difficulties were among the prominent reasons behind why the UK joined the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1975 in the first place, and why Mrs Thatcher herself was, for many years, a passionate advocate for European integration through the EEC.

Yet at the same time, Mrs Thatcher was unequivocally socially conservative - the daughter of a Methodist lay preacher, she maintained traditional social and cultural values with regard to human sexuality, outlawing the ‘promotion’ of homosexuality in schools, for example. The ECR’s promotion of traditional ‘family values’ certainly fitted within such a ‘Thatcherite’ worldview, where a small state left the economy to function on its own and families were left to live their lives without government promoting what they would regard as permissive and ‘faddish’ ideas about personality morality. After Mrs Thatcher left office in 1990, the British Conservatives underwent a gradual but steady ‘modernisation’, with the youthful leaderships of William Hague and then David Cameron especially important in relation to changing the image of the party as being attractive mainly to older voters. Nevertheless, Mrs Thatcher’s influence on the party remained and the ECR’s think tank in Brussels, New Direction, continued to recognise her as its ‘founding patron’ (New Direction, Citation2021). At the time of writing, New Direction’s senior advisor was Tony Abbott, the former Australian Prime Minister, who, whilst in office, also combined a Thatcherite affection for both the free market and social conservatism. At the same time, although Law and Justice has often been described as ‘nationalist’ or ‘populist’ (Henley & Davies, Citation2020) an equally, if not more, accurate description of the party would be as a socially conservative grouping that believed firmly in the role of traditional ‘family’ and Christian values.

Indeed, this policy stance could be contrasted with other EP groupings in Strasbourg. The Socialists and Democrats, ‘Renew Europe’ and the Greens could all have been described as culturally left-wing and ‘socially liberal’ in terms of their attitudes towards issues such as state recognition of same-sexual relationships, societal structures, and the place of religion and Christian values in public life. The EPP did contain some socially conservative elements given its roots in Christian Democracy. For example, the Bavarian wing of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) in Germany, the Christian Social Union of Bavaria (CSU), was less afraid of saying that it wanted to see a traditional approach taken towards ‘family values’, multi-culturalism and secularism but was ultimately outvoted at a national German level. (Christian Social Union, Citation2020). Ultimately, the EPP tended to shy away from confrontation over sensitive and emotive topics such as human sexuality or multi-culturalism. Meanwhile, at the other end of the political spectrum, ‘Identity and Democracy’ MEPs focused much more on issues related to immigration and were relatively unconcerned about being denounced as ‘offensive’ by social liberals when it came to issues surrounding race, religion and diversity (Identity and Democracy, Citation2020).

The ECR’s formal position as an EP grouping on migration and freedom of movement around the EU bloc was broadly favourable – although it also started from the premise that the system could be managed better. Individual member states, they argued, should have more say on who could or could not enter their territory, and there should be greater security around the EU’s external borders with individual member states exercising more autonomy (see European Conservatives and Reformists group, Citation2020). Moreover, crucially, it was ultimately rooted in its affection for the role of Christianity in European society - politicians such as Marine Le Pen in France or Matteo Salvini in Italy in the ‘Identity and Democracy’ grouping, on the other hand, were much more prepared to come out and argue for lower levels of immigration overall and in every respect (Identity and Democracy, Citation2020). The ECR disliked what it saw as the bland Western European secularism of the EPP but, at the same time did not advocate a systematic closing of the Europe’s borders, nor did it show open hostility towards non-European immigrants per se. The Polish Law and Justice party was, for example, more concerned about mass Muslim immigration and what it felt constituted enforced multi-culturalism, exemplified by the EU’s 2015 migrant re-location scheme.

Indeed, in some areas of its work, ECR MEPs were active in promoting the freedom of religion and the need for the state to respect all beliefs, including those of Christians living in non-Christian countries (European Conservatives and Reformists party, Citation2020). Between 2014–2019 the ECR leader in the EP was British Conservative MEP Syed Kamall, a practising Muslim representing the metropolitan Greater London region. Although some of the ECR’s activities and stances on social policy issues were sometimes described as ‘far right’ by some of its critics in the opinion-forming social and culturally liberal media (Henley & Davies, Citation2020), its members felt that they actually represented the mainstream of public opinion in many European countries, especially in the Central and Eastern states, that rarely found a voice in such outlets.

Conclusions

In spite of the fact that it secured the smallest number of seats since it was formed ahead of the 2009 EP election, ironically the 2019 poll could perhaps be considered the most successful of all for the ECR. In the 2009 elections, the ECR emerged as the fourth largest grouping in the EP, while after the 2014 poll it held the third largest number of seats in the Hemicycle, displacing the Liberal ALDE faction as the parliament’s ‘kingmakers’. For the grouping to become only be the sixth largest faction unquestionably represented a decline of sorts, superficially at least. Yet many leading ECR MEPs felt that the 2019 elections represented a strong performance across the EU-27 (European Conservatives and Reformists group, Citation2020) and, in many ways, this was not an inaccurate evaluation. The grouping firmly consolidated its long term presence in Strasbourg and Brussels as a political vehicle for conservatism, despite the fact it lost its largest national delegation, the British Conservatives, as a consequence of the UK leaving the EU. Its leadership could look ahead to another five years of, as they saw it, enthusiastically promoting conservative values in the EP, and arguing for a ‘looser‘ EU with a greater focus on security, the single market and the sovereign rights of member states as well as the freedom of individual Europeans.

Moreover, the greater prominence for Poland’s Law and Justice party in the leadership of ECR did not represent a radical departure from its pre-2019 organisation either but rather considerable continuity. The ECR always contained large numbers of Central and Eastern European member parties attracted by its ‘Anglosphere’ pro-America messaging, strong support for NATO, and a broader ‘Eurorealist’ dislike of aspects of ‘ever closer (political) union’. The fact that the British Conservative Party no longer enjoyed representation in the EP did not mean that its strong conservative legacy did not continue via MEPs from Poland, the Czech Republic and elsewhere. Those MEPs were completely comfortable with using the conservative term, and owning such a label, and often promoted policies associated with this political tradition in their approach to European integration, trans-Atlantic relations, the single market and business, and ‘family values’ and Christianity.

CEE states such as Poland and Hungary became the main context for electoral Soft Euroscepticism and, in particular, ‘Eurorealism’ - where mainstream voters expressed broad support for EU membership in principle but, at the same, wariness of any perceived Brussels overreach. Despite suggestions to the contrary, this was far removed from the more often openly ‘Hard Eurosceptic’ sentiment expressed by radical right politicians such as Matteo Salvini of Lega Nord in Italy or Marine Le Pen of National Rally in France. Yet it was also distinct from the more uncritically pro-EU support also found in the EPP grouping traditionally associated with the centre-right. In spite of the departure of the British Conservatives, through the vehicle of the ECR, conservatism continued to very much have a central voice in Strasbourg and Brussels, albeit with much more of a CEE pronunciation.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the helpful comments made when a draft paper was presented at a research seminar hosted by the Sussex European Institute. No financial benefit has arisen from the direct application of the research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The research for the article draws upon a range of primary and secondary sources, including interviews with key ECR politicians conducted in Brussels and Strasbourg between 2016 and 2019, programmatic statements and a period of primary documentary study in the Conservative Party archives at Churchill College, Cambridge, alongside more overtly quantitative analyses of European Parliament elections results.

References

- Bale, T., Hanley, S., & Szczerbiak, A. (2010). May contain nuts? The reality behind the rhetoric surrounding the British conservatives’ new group in the European parliament. The Political Quarterly, 81(1), 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-923X.2009.02067.x

- BBC News. (2020). ‘Poland’s clash of values in presidential election’: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-53190016, 29 June.

- Boyes, R. (2009). ‘Klaus determined to weather the storm over Lisbon Treaty veto’, The Times: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/vaclav-klaus-determined-to-weather-the-storm-over-lisbon-treaty-veto-26bxt9wjwr8, 17 October.

- Chapman, A. (2020). ‘Poland’s leadership doesn’t need “Polexit”: it can undermine the EU from within’, The Guardian, 10 March.

- Christian Social Union of Bavaria. (2020). ‘Program’, available here: http://csu-grundsatzprogramm.de/.

- Chryssogelos, A. (2019). ‘What Europe can learn from the Law and Justice’s Party victory in Poland’, Chatham House https://www.chathamhouse.org/2019/10/what-europe-can-learn-law-and-justice-partys-victory-poland, 15 October.

- Churchill, W. (1946). ‘United States of Europe’, speech delivered at University of Zurich, 19 September.

- Erhard, L. (1958). Prosperity through competition. Thames and Hudson.

- European Conservatives and Reformists. (2021). ‘European Parliament adopts the European Defence Fund’, available here: https://ecrgroup.eu/article/european_parliament_adopts_the_european_defence_fund, 29 April.

- European Conservatives and Reformists group. (2020). ‘Our vision for Europe’, available here: https://ecrgroup.eu/vision_for_europe.

- European Conservatives and Reformists party. (2020). ‘2020 United States Elections’, available here: https://ecrparty.eu/event/2020_united_states_elections.

- European Council on Foreign Relations. (2018). ‘Divided at the centre: Germany, Poland and the troubles of the Trump era’, available here: https://www.ecfr.eu/publications/summary/divided_at_the_centre_germany_poland_and_the_troubles_of_the_trump_era, 19 December.

- European Parliament. (2022). ‘2019 European Parliament elections results’, available here: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/election-results-2019/en.

- French Ministry for Foreign Affairs. (2017). ‘President Macron’s Initiative for Europe: a sovereign, united, democratic Europe’, available here: https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/french-foreign-policy/europe/president-macron-s-initiative-for-europe-a-sovereign-united-democratic-europe/, 26 September.

- Garnett, M. (2018). Conservative moments: Reading Conservative texts. Bloomsbury.

- Hanley, S. (Ed.). (2007). The New right in the New Europe: Czech transformation and right-wing politics, 1989-2006. Routledge.

- Henley, J., & Davies, C. (2020). ‘Poland’s populist Law and Justice party win second term in power’, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/oct/14/poland-populist-law-and-justice-party-increases-majority, 14 October.

- Hertner, I. (2018). Centre-left parties and the European Union: Power, accountability and democracy. Manchester University Press.

- Hix, S., Noury, A. G., & Roland, G. (2007). Democratic politics in the European parliament. Cambridge University Press.

- Identity and Democracy. (2020). ‘Platform’, available here: https://www.id-party.eu/.

- Jansen, T., & Van Hecke, S. (2011). At Europe’s service: The origins and evolution of the European People’s party. Springer.

- Katz, R., & Mair, P. (1994). How parties organize: Change and adaptation in party organization in Western democracies. Sage.

- Law and Justice. (2019). ‘Program’, available here: http://pis.org.pl/dokumenty, 14 September.

- Legutko, R. (2017). Interview with author, Brussels, 28 November.

- Leruth, B. (2016). Is “euro-realism” the new “euro-scepticism”? modern conservatism, the European Conservatives and Reformists and European integration. In J. FitzGibbon, B. Leruth, & N. Startin (Eds.), Euroscepticism as a transnational and Pan-European phenomenon: The emergence of a New sphere of opposition (pp. 46–62). Routledge.

- Mair, P. (1990). The Western European party system. Oxford University Press.

- McDonnell, D., & Werner, A. (2018). Respectable radicals: Why some radical right parties in the European Parliament forsake policy congruence. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(5), 747–763. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1298659

- McElroy, G., & Benoit, K. (2010). Party policy and group affiliation in the European parliament. British Journal of Political Science, 40(2), 377–398. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123409990469

- New Direction. (2021). ‘About’, available here: https://newdirection.online/about, accessed 30 April 2021.

- Poland In. (2020). ‘Duda-Trump meeting: Brothers in arms not on parade in Moscow’, 25 June.

- Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster.

- Spetalnick, M., & Nichols, M. (2020). ‘Despite changes at the White House, US allies will remain wary after Trump’, Reuters, 7 November.

- Steven, M. (2020). The European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR): politics, parties and policies. Manchester University Press.

- Szczerbiak, A. (2018). Politicising the Communist past: The politics of truth revelation in post-Communist Poland. Routledge.

- Szczerbiak, A., & Taggart, P. (2008). Opposing Europe? The comparative party politics of euro-scepticism, volumes I and II. Oxford University Press.

- Von Beyme, K. (1985). Political parties in Western democracies. St Martin’s.

- Ware, A. (1996). Political parties and party systems. Oxford University Press.

- Whitaker, R., & Lynch, P. (2014). Understanding the formation and actions of the Eurosceptic groups in the European Parliament: Pragmatism, principles and publicity. Government and Opposition, 49(2), 232–263. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2013.40

- Zahradil, J. (2017). Interview with author, Brussels, 2 March.