ABSTRACT

European democracies appear to be facing substantial difficulties. Challenges arise from the emergence of right-wing populist parties and the withdrawal of citizens from established political parties. These changes it is claimed have led to an erosion of trust in the democratic political system. Drawing on ten waves of the European Social Survey from 2002 to 2020 in 11 Western European countries we test the evidence for a decline in democratic sentiment. Results do not support any deterioration in satisfaction with the way democracy works and trust in parliament, legal and police systems. Nor have hostile attitudes to immigrants increased in this period. Given the general rise in the electoral support for these parties our findings appear puzzling. However, while the evidence indicates no deterioration, attitudes to political parties and parliaments were far from positive in 2002 providing fertile ground for the emergence of populist radical right-wing parties.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

European democracies appear to be weakening and face substantial difficulties. Challenges arise from two well-documented and interrelated factors in the emergence of populism, particularly in the form of right-wing populist parties, and the withdrawal of citizens from established political parties and democratic participation generally. Right-wing populist parties have emerged in most European countries in recent decades as relatively major political players in national elections and are likely to be an integral part of the European political landscape for some time (Rensmann et al., Citation2017; Rooduijn, Citation2015). Indeed these parties have won national elections and dominate the parliaments in Hungary and Poland. In France the National Rally gained just 19 per cent of the vote in the 2022 election to the National Assemble and 41 per cent in the second round of the presidential election while in the same year in Italy the right-wing populist party Brothers of Italy won 26 per cent of the vote in the national election to the Italian parliament. A second threat undermining the health of democratic societies it is claimed is the ‘withdrawal’ of citizens from the political process and the weakening of established political parties thus undermining a fundamental core of the political process (Anheier, Citation2015; Mair, Citation2013). Such trends would represent a clear threat to the system of democratic government that is a crucial institution of European countries in which rulers are held accountable for their actions in the public realm by citizens, acting indirectly through their elected representatives (Schmitter & Hary, Citation1991, p. 76). A consequence of these political shifts poses a threat it is argued to the European Union as a democratic entity and to democracy in individual member states (Fossum, Citation2023; Spittler, Citation2018).

However, it may be the case that such political changes and realignments in recent decades likely reflect disappointment among a substantial proportion of people (the eponymous losers) with the outcomes of an increasingly globalised economy and growing material inequality rather than disaffection with democracy as a method of government (Zaslove et al., Citation2021, p. 732). Structural inequality has always been a characteristic of mature industrial societies but since the 1970s there has been a consistent and general rise in wealth-to-income ratios that appears to be returning to the high values observed in Europe in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Piketty & Zucman, Citation2014, p. 1257). Yet there appears to be incongruence between political parties, governments and their citizens in addressing issues of redistribution. According to Rosset and Stecker (Citation2019) citizens in Europe are more likely to be to the left of their government on issues of redistribution. In particular relatively poor citizens are under-represented on redistribution while richer and better-educated citizens are likely to get a representation bonus from their representatives or their governments (Rosset & Stecker, Citation2019). In this context, the rejection of the political status quo and the shortcomings of established political parties by many European citizens is, perhaps unsurprising, especially among those at the bottom of the social hierarchy who are the perennial losers in the allocation of social and material goods (Pichler & Wallace, Citation2009; Schäfer, Citation2012). Here we examine whether the increase in support for right-wing populist parties and the weakening of established political parties has been accompanied by an erosion of the political public sphere in a number of mature Western European democracies. To assess the extent of European citizens’ dissatisfaction with the state of democracy and trust in specific state institutions in a number of European countries we draw on ten waves of the European Social Survey from 2002 to 2020. Political trust can be considered a core indicator of political legitimacy and its decline is associated with declining voter turnout, reduced compliance with public policy and more conservative preferences over government policy (Devine, Citation2024).

Threats to democracy in Europe

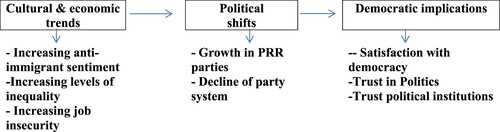

A number of economic and cultural trends are identified in the literature as causes for the growing strength of right populism such as rising income inequality (Stoetzer et al., Citation2021), growing economic insecurity as a result of globalisation and transformed labour markets (Rodrik, Citation2018), anti-immigrant sentiment (Margalit, Citation2019) and declining trust in political elites and established political parties (Gidron & Ziblatt, Citation2019; Rooduijn, Citation2018). Much of the research on populist right-wing parties indicates a preponderance of low-skill workers in production and services voting for such parties who formerly voted for political parties on the left (Oesch & Rennwald, Citation2018).

At the core of Right-wing populism whether conceived as a concept or ideology is the notion of ‘nativism’ a xenophobic form of nationalism where states should be occupied only by members of the native group or nation and non-native elements represent a threat to the homogenous nation-state (Mudde, Citation2007). Political parties that espouse such policies are commonly referred to as populist radical right-wing parties (Mudde, Citation2007; Rooduijn, Citation2015). Not surprisingly ant-immigrant policies are central to populist radical right-wing parties (PRR) parties and negative attitudes to immigrants are strong among the supporters of these parties. In the populist narrative society is considered to consist of two distinct homogenous and antagonistic groups – the pure people versus the corrupt elite while politics should be an expression of the general will of the people. Populist parties generally claim to give voice to people who have been neglected and ignored by alleged corrupt elites (Eatwell & Goodwin, Citation2018, p. 48; Schmidtke, Citation2021). In sum populist parties are associated with opposition to outsiders such as immigrants, antagonism towards the elite and the establishment, culturally conservative and claim to represent the common or true/pure people (the nation). At the extreme end popular democracy that reflects the pure will of the people can potentially lead to a majoritarian tyranny or democratic illiberalism as has occurred in Hungary under Victor Orben’sFidesz party and the Law and Justice party in Poland (Berman, Citation2017; Bustikova & Guasti, Citation2017; Horonziak, Citation2022; Pappas, Citation2019). The appeal of populism originates from a ‘deep-seated discontent’ with representative liberal democracies (Rensmann et al., Citation2017, p. 110). Indeed where right-wing populist parties have achieved an elected majority in parliament as in Hungary and Poland there has been a notable weakening of democratic institutions and the rule of law (Horonziak, Citation2022, p. 271). Consequently the conventional position is that right-wing populism constitutes an intrinsic danger to democracy (Mudde & Kaltwasser Citation2018; Spittler, Citation2018).

However the evidence from people with populist attitudes is not wholly conclusive. Using survey data from the Netherlands Zaslove et al. (Citation2021) found that individuals with stronger populist attitudes are ‘more’ supportive of democracy and democratic principles compared to individuals with weaker populist attitudes. Mauk (Citation2020) combining various surveys reported that populist party success had an overall positive effect on levels of political trust at least in the short run among the general public in 23 European democracies (see also Haugsgjerd (Citation2019) for a similar outcome in Norway). Despite such findings, it appears that right-wing populists endorse principles of liberal democracy such as the granting of civil liberties and the protection of minorities to a lesser extent compared to non-populist individuals and were less supportive of democratic norms (Bos et al., Citation2023; Guinjoan, Citation2023). Certainly, the core characteristics of populism such as anti-elitism, nativism and anti-immigrant sentiment are claimed to be associated with negative sentiment and dissatisfaction towards the established political order (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2012).

Changes in the way that contemporary liberal democracies, particularly established political parties, function has also been seen as a factor in the emergence of populism (Canovan, Citation2002; Mair, Citation2002). Mair (Citation2002; Citation2013) argues that the ideological and policy difference between political parties has reduced while the relationship between parties and voters has become more tenuous and transient. A lack of polarisation leads to the rise of populism where established political parties fail to offer any radical alternative to a depoliticized liberal democracy in which an enforced consensus has taken the politics out of politics (Laclau, Citation2005; Mouffe, Citation2000). Too much emphasis on consensus coupled with an aversion to confrontation can lead to ‘apathy and to disaffection with political participation’ (Mouffe, Citation2000, p. 16). An example of such a consensus Grindheim (Citation2019) observes is how a ‘duopoly of the centre-left and centre-right political establishment’ has kept issues such as immigration ‘off the public agenda’ opening the way for PRR parties with an anti-immigration agenda. These changes it is claimed have created a growing distrust of parties and political institutions by the public with citizens and politicians withdrawing from electoral politics (Mair, Citation2008). Withdrawal has taken the form of declining electoral turnout, increased voter volatility, declining party identification and reduced political activism (Carty, Citation2022; Mair, Citation2013).

Hypotheses

The set of relationships suggested from our literature review are outlined in . Cultural and economic changes such as increasing ethnic diversity in society, increasing inequality, economic insecurity for those with low educational and skill levels and declining trust in extant political institutions, are linked to shifts in political alignments with implications for the democratic system.

Here our primary focus is whether the apparent fundamental realignments in politics due to the emergence of PRRs and the hollowing out of established parties have been accompanied by an erosion of citizens’ attitudes and trust in the democratic process in eleven Western-European countries from 2002 to 2020. Right-wing populist parties in most of the countries selected have experienced a surge in their vote in national and European elections with the exception of the Netherlands, Norway and Ireland (where there is no established populist party) (). In the Netherlands the Party for Freedom experienced a considerable decline in the European elections in 2019 but subsequently recorded a substantial increase in the national elections in 2023 while in Norway the Progress Party’s national vote declined slightly in 2012 by three per cent.

Table 1. National vote for PRR parties and the proportion of foreign born population per country.

Given the considerable evidence noted earlier it is likely that those who vote for populist parties are more likely to be dissatisfied with how democracy works. Moreover, the core aspects of populism such as anti-elitism, nativism and anti-immigrant sentiment are likely to be associated with dissatisfaction towards the established political order and hence it can be predicted that satisfaction with the way democracy works has declined in the twenty-first century (hypothesis 1). In addition, the void in the political system as political parties become ideologically similar and more distant from citizens is likely to adversely affect attitudes toward the traditional political establishment including traditional political parties and key political institutions like parliament. In this context, it can be predicted that over the period 2002 and 2020 citizens are likely to have reduced levels of trust in political parties and politicians generally (hypothesis 2). Likewise, it can be expected that citizens will display lower trust levels over time with their parliament and with the legal and police systems (hypothesis 3).

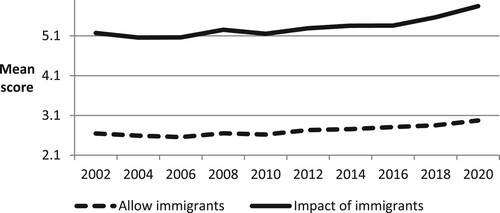

A central feature of the hollowing out of established political parties is the decreasing tendency of citizens to become politically active both regarding voting in elections and in protest type actions. An important claim of the proponents of the hollowing-out thesis is that generally citizens have become alienated from the political process as there is little to decide between main-stream parties. Consequently, it can be predicted that citizens have become less interested in politics (hypothesis 4). A common platform of PRR parties and populists voters is the curtailment and control of immigration flows into the country. Anti-immigrant policies appear to play a central role in the attraction of populist voters. In a study of seven Western European countries attitudes to immigration according to Ivarsflaten (Citation2008) was the principal motivation to vote for such parties (see also Van der Brug et al., Citation2000 and Rodi et al., Citation2023). Most European Union (EU) countries experienced a significant increase in migration in the latter part of the twentieth century, including countries previously characterised as emigrant countries such as Ireland, Italy and Spain (Van Mol & de Valk, Citation2016). Since 2000 the proportion of immigrants resident in the EU has increased substantially (Eurostat, Citation2023). The proportion of the foreign-born population in our sample countries averaged 15.2 per cent in 2022 (). Given the well documented link between right-wing populism and anti-immigrant sentiment it can be expected that negative attitudes towards allowing immigrants into the country and their economic and cultural impact have increased since 2000. People who favour a more restrictive policy on immigration are likely to blame established political parties and politicians for liberal immigration policies. This disenchantment with the extant political establishment may extend beyond the established political parties to encompass key political institutions like the national parliament. In this context, it can be predicted that attitudes towards allowing a greater number of immigrants into the country have decreased since 2000 (hypothesis 5) and that attitudes towards the economic and cultural impact of immigrants have become more negative (hypothesis 6).

Data and methodology

Countries are selected based on a relatively long and stable democratic tradition and participation in all ten survey rounds (Italy being an exception with participation in only 9 survey rounds). Thus the countries in our sample represent the foundation of the European democratic tradition and any weakening in the commitment of their citizens to the democratic process and its institutions would herald a fundamental realignment of European political life. Eleven countries are included in our sample (see ). Appropriate weights are applied to adjust for sampling and population size. The data used here comes from ten rounds of the European Social Survey (ESS). The ESS is a biennial multi-country survey covering over 20 nations. The first round was fielded in 2002 and the tenth round in 2020. Data collection is by means of face-to-face interviews of approximately an hour in duration. The requirement is for random (probability) samples with comparable estimates based on full coverage of the eligible populations aged 15 and over resident within private households in each country, regardless of their nationality, citizenship or language. Individuals are selected by strict random probability methods at every stage and a target response rate of 70 per cent is set for each country. All countries must aim for a minimum ‘effective achieved sample size’ of 1500 or 800 in countries with populations of less than 2 million after discounting for design effects.

Political measures and openness to outsiders

Conceptually our political measures can be divided into those that reflect a more diffuse attitude to democracy such as satisfaction with democracy and more specific type measures that focus on political actors and institutions (Singh & Mayne, Citation2023). Diffuse support for democracy reflects a more stable and strong attachment to a democratic regime (Thomassen & van Ham, Citation2017). Satisfaction with democracy can be considered a relatively reliable construct given the study is restricted to mature Western European countries (see for example Poses & Revilla, Citation2022; Singh & Mayne, Citation2023). It is measured here by two items that gauge satisfaction with the way democracy works and the way the government is doing its job (). Trust in political institutions by citizens is commonly considered essential to the functioning and legitimacy of democracy and acts as the glue that keeps the system together (see for example Schneider, Citation2017; van der Meer & Zmerli, Citation2017). Political trust denotes belief in the reliability, truth, or ability of political institutions such as government and parliament to look after the interests of its citizens (Devine, Citation2024). Specific measures of trust in a democratic regime typically focus on political actors and democratic institutions. Here the former is measured by two items: trust in politicians and political parties. Trust in core institutions is measured by three items (Cronbach alpha = 0.75): trust in country’s parliament, the legal system and the police. Interest in politics is measured by one item.

Table 2. Comparing changes in the dependent measures in 2002 and 2020.

Attitudes to immigrants are gauged by the extent to which respondents agree with allowing more into the country measured by three items (alpha = 0.9): allowing immigrants of the same ethnic group as majority in the country, immigrants of a different ethnic group from the majority and immigrants from poorer countries outside Europe. Lastly, the economic and cultural impact of immigrants is measured by three items that gauge their impact on the economy and cultural and social life.

Control measures

While our main approach is descriptive using trend data we also test associations between a number of control variables and possible interaction effects between openness to outsiders and the political measures. Particularly whether respondents with restrictive views towards immigrants (a proxy measure for potential supporters of populist right wing partiesFootnote1) display greater disaffection with the political establishment compared to respondents with liberal views. In line with the causal associations specified in shifts in traditional political alignments specifically the emergence of successful right-wing populist parties and the fragmentation of traditional party systems dominated by centre-left and centre right parties are argued to be rooted in the emergence of new cleavages particularly between the expanded mass graduate class and early school leavers, a deepening generational divide across aging societies and the development of mass migration and growing ethnic diversity (Ford & Jennings, Citation2020). Along with age and years of education a number of societal and material measures are used in the multivariate analysis that includes generalised trust levels and political orientation; work-related measures of whether respondents are able to cope on their income, experience of unemployment and union membership. Generalised trust embodies the belief that others are generally reliable and will not take an unfair advantage. As Jamal and Nooruddin (Citation2010, p. 46) observe ‘one of the long-standing stated correlates of support for democracy has been generalized trust’ (see, for example, Putnum Citation1993). Having difficulties coping with an inadequate income and experiences of unemployment are likely to have less commitment to the existing social and political order compared to those in a more privileged position in the social hierarchy who are more likely to espouse a conception of democracy consistent with the political status quo than individuals with lower social status (see for example Ceka & Magalhães, Citation2020). Being a member of a trade union is also included as it has been associated with a stronger commitment to democracy. The independent effect of trade union membership on political participation was found to be both significant and positive and is associated with higher levels of political activism and electoral participation (Turner et al., Citation2020).

Results

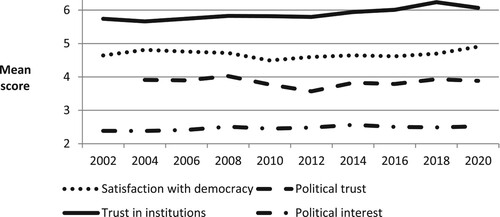

In the countries as a whole, the trend in the mean score of the four political measures between 2002 and 2020 has remained relatively static ().

All the dependent measures show a decrease in the proportion of respondents with negative attitudes below the midpoint of the range and a corresponding increase in positive attitudes above the midpoint in a comparison of the results for 2002 and 2020 (). Satisfaction with democracy, trust in parliament, the law and police and to a lesser extent political interest increased between the survey year of 2002 and 2020 (). Thus there appears to be no support for the proposition that satisfaction with the way democracy works has decreased in the twenty-first century or that respondents display lower trust levels with their parliament, legal and police systems (hypothesis 1 and 3). Nor is there any support that citizens have become less interested in politics (hypothesis 4). Indeed the decline in negative attitudes and increase in positive attitudes above the midpoint for all three measures was statistically significant between 2002 and 2020. However, there was negligible and statically non-significant change in the level of trust in politics during this period providing no support for hypothesis 2 that over the period 2002 and 2020 citizens are likely to have reduced levels of trust in political parties and politicians generally.

As shows positive attitudes to immigrants in terms of access to the country and economic and cultural effects have almost consistently increased in the survey rounds from 2002 to 2020. The differences are sizeable between 2002 and 2020 and are statistically significant (). These results refute the expected trend that more hostile attitudes to immigrants have emerged in the twenty-first century providing no support for hypotheses 5 and 6.

In countries are grouped into those with a tendency to score above the mean on the dependent measures and those tending below the mean. Countries in the latter group include France, Spain, UK, Belgium and Italy while Finland, Sweden, Ireland, Norway, Netherlands and Germany make up the former group with above-average scores. T-tests are used to gauge statistical differences in the mean scores between the survey round of 2002 and 2020. A positive sign (+) denotes an increase in the mean between the two points and a minus sign (−) shows a decrease in the mean. Apart from Sweden negative shifts in the mean score in the dependent measures have occurred in those countries with below mean tendencies. Nevertheless, even in the latter group the general pattern is a shift towards more positive attitudes across all the dependent measures.

Table 3. Mean change in political attitudes in individual countries 2002–2020.

Nor is there any consistency between changes in attitudes and a surge in populist support in a country between 2002 and 2020 (see ). In Sweden where support for the populist Sweden democrats rose sharply mean scores were either significantly lower in 2020 or non-significant across the dependent measures except levels of political interest. Alternatively despite the strong increase in the populist True Finns Party in Finland and the populist Party for Freedom in the Netherlands mean scores in all of the dependent measures increased significantly in both countries. Moreover, in countries such as Spain, France, the UK and Italy where populist parties also enjoyed considerable gains in the twenty-first century there are more instances of an increase in positive than negative sentiment with regard to our dependent measures. Although Spain, UK and Belgium recorded a decline in satisfaction with democracy and to a lesser extent political trust between 2002 and 2020 there was a significant positive increase in these countries in the measures of trust in institutions, political interest and attitudes to immigrants. Specifically, the prediction of hypothesis 1 that satisfaction with the way democracy works has declined is supported by the results in Sweden, Spain, the UK and in Belgium. Support for hypothesis 2 that citizens are likely to have reduced levels of trust in political parties and politicians generally is only strongly supported in Spain and more weakly in the UK. Only in Italy do respondents display lower trust levels over time with their parliament and with the legal and police systems as predicted by hypothesis 3. Nor is the proposition in hypothesis 4 that citizens have become less interested in politics except for a weak negative association in Italy. Finally the prediction of hypothesis 5 that attitudes towards allowing a greater number of immigrants into the country has decreased and hypothesis 6 that attitudes towards the economic and cultural impact of immigrants has become significantly more negative is only borne out in Sweden. Thus there are exceptions among individual countries to the aggregate pattern outlined in . Yet these exceptions remain in a minority to the overall positive scenario demonstrated in .

Multivariate analysis

Linear regression is used in to assess the impact on political sentiment of individual characteristics, generalised trust, political orientation and workplace factors. As noted earlier an anti-immigrant platform is central to PRR parties and respondents with negative views of immigrant are more likely to be PRR supporters. Regression allows a test of the effects of negative attitudes toward immigrants on the dependent measures of satisfaction with democracy, political and institutional trust. In particular respondents with restrictive views on allowing immigrants into their country are more likely to be supporters of PRR parties, The measure of political interest is also included as a dependent variable as it allows an assessment of whether people who have no interest in politics are more likely to be disenchanted with democracy and established political parties.

Table 4. Factors affecting political attitudes (Linear regression method with significant standardised Betas reported).

All eleven countries are combined together across the ten survey rounds from 2002 to 2020. In addition, the ten survey rounds are constructed as dummies with the 2002 survey as the referent year. Controlling for the various independent measures respondents in the 2020 survey round are significantly more likely to have higher levels of satisfaction, trust in institutions and political interest compared to the 2002 survey. However, trust in politicians and political parties significantly declined between 2002 and 2020 providing some support for hypothesis 2. Aside from this, the results confirm our previous findings of no support for a decline in democratic sentiment (Hypotheses 1, 3 and 4).

Higher levels of generalised trust and affirmative attitudes towards the impact of immigrants and to a lesser extent satisfaction with income have consistently the strongest positive effect on democratic sentiment. Although holding restrictive attitudes to allowing immigrants into the country had a relatively weak impact on the political measures there is a significantly high Pearson correlation between negative attitudes to the impact of immigrants and restrictive attitudes to allowing immigrants into the country (P = 0.62***). Clearly negative attitudes to the access and impact of immigrants, our proxy measure for the support of PRR parties, is significantly associated with lower levels of satisfaction with democracy and the core political institutions. Having a left political orientation, experience of unemployment and surprisingly being more amenable to allowing immigrants into the country are negatively associated with democratic sentiment.

Conclusion

Using ten rounds of the ESS this paper tests the claims that the growing strength of right populism and declining trust in political elites and established political parties has resulted in a general erosion of trust in the democratic political system in the twenty-first century. Based on the results from the ESS there is scant evidence that this is the case. On the whole, the aggregate trend in the diffuse measure of satisfaction with democracy and specific measures focusing on political actors and institutions between 2002 and 2020 remained relatively consistent for the combined eleven countries with a modest positive increase in trust levels. Thus there appears to be little support that satisfaction with the way democracy works has decreased in the twenty-first century or that respondents display lower trust levels with their parliament, legal and police systems or have become less interested in politics. Nor is there any evidence that more hostile attitudes to immigrants have emerged as positive attitudes to immigrants in terms of access to the country and economic and cultural effects have generally increased in the survey rounds from 2002 to 2020. Countries that scored below the mean average on the political measures such as France, Spain, UK, Belgium and Italy were more likely to record some evidence of a negative shift between 2002 and 2020. Nevertheless, even in this group the general pattern is a shift towards more positive attitudes across the dependent measures. Sweden though scoring above the mean average on all measures stands out as an exception with negative shifts in satisfaction with democracy and attitudes to immigrants. This is consistent with the expectation that a surge in support for populist parties would lead to an increase in anti-elite sentiment and lower levels of trust in the extant social institutions including parliament, established political parties and the legal system. Yet the evidence for such a relationship is absent in Finland and the Netherlands, countries that experienced an increase in the vote for PRR parties. Although Spain, UK and Belgium recorded a decline in satisfaction with democracy there was a significant increase in Italy. Moreover, attitudes to immigrants became more positive even in those countries where PRR parties increased their vote with the exception of Sweden. This is particularly significant as a central and common platform of these parties is their hostile policy stance on immigration as ‘outsiders’ are perceived as a threat to a homogeneous native state. Given the general rise in the electoral support for these parties in the twenty-first century the trends in trust in the political system and attitudes to immigrants in our findings appear puzzling.

It may be the case that support for democracy and immigrants has increased to such an extent among respondents who are not sympathetic to PRR parties that it outweighs any negative tendencies from right-wing populist voters. In the absence of longitudinal type data this is difficult to verify. Moreover, it assumes that supporters of PRR parties are a homogeneous cohort with similar attitudes towards politics and state institutions. The attitudes of voters within and between different parties within the populist platform are likely to vary considerably. A study of 11 Western European countries found that the electorates of populist parties did not always consist of individuals more likely to be losers of globalisation with Eurosceptic attitudes and low levels of political trust Rooduijn (Citation2018). In this vein, the increase in parliamentary representation of PRR parties in most of the countries in our study may act as a signal for many voters that perceived political norms have shifted to ‘make radical right views less stigmatised’ and more legitimate and acceptable (Valentim Citation2021, p. 2475). Political normalisation and legitimacy of populist parties possibly function to reduce distrust in the political system for traditional PRR supporters and attract a wider cohort of voters less distrustful of the political system.

A further possibility is that while a commitment to democracy remains relatively unchanged in the twenty-first century, confidence in democratic institutions particularly established political parties were already relatively weak at the start of the century due in many cases to a convergence of centre right and centre left parties offering similar policies to voters (Abedi, Citation2002). PRR parties tend to attract the politically discontented and alienated from the established parties particularly those who are ‘regular losers of the political game’ and favour radical system change (König & Wenzelburger, Citation2022, p. 3). Indeed only 18 per cent of respondents across the eleven countries reported levels of trust in political parties above the centre point of the range in 2004 rising to 21 per cent in 2020 while the majority 61 per cent indicated low trust levels in parties in 2004 increasing to 63 per cent in 2020. Low levels of trust in parliament increased from 41 per cent below the centre point of the range in 2002 to 43 per cent in 2020 compared to 36 per cent with high levels of trust in 2002 and 39 per cent in 2020. Thus even at the beginning of the twenty-first century a majority of people appeared to have low levels of trust in political parties and a substantial proportion of respondents had relatively low levels of trust in parliament.

Although the evidence from the ESS indicates no deterioration in democratic sentiment between 2002 and 2020, attitudes to political parties and parliaments were far from positive in 2002 providing fertile ground for the emergence of new political forces such as populist radical right-wing parties. Our findings in this context provide some solace that commitment to democracy and its institutions has not declined over this period but there is little room for complacency.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data used here is available from the European Social Survey website.

Notes

1 Overall 73 per cent would allow many or some immigrants into the country while 27 per cent would allow none or few in the eleven countries across the ten survey rounds combined.

References

- Abedi, A. (2002). Challenges to established parties: The effects of party system features on the electoral fortunes of anti-political-establishment parties. European Journal of Political Research, 41, 551–583.

- Anheier, H. (2015). Conclusion: How to rule the void? Policy responses to a ‘hollowing out’ of democracy. Global Policy, 6(S1), 127–129.

- Berman, S. (2017). The pipe dream of undemocratic liberalism. Journal of Democracy, 28(3), 29–38.

- Bos, L., Wichgers, L., & van Spanje, J. (2023). Are populists politically intolerant? Citizens’ populist attitudes and tolerance of various political antagonists. Political Studies, 71(3), 851–868.

- Bustikova, L., & Guasti, P. (2017). The illiberal turn or swerve in Central Europe? Politics and Governance, 5(4), 166–176.

- Canovan, M. (2002). Taking politics to the people: Populism as the ideology of democracy. In Y. Mény & Y. Surel (Eds.), Democracies and the populist challenge (pp. 25–44). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Carty, R. (2022). Into the void: The collapse of Irish party democracy. Irish Political Studies, 37(2), 303–325.

- Ceka, B., & Magalhães, P. (2020). Do the rich and the poor have different conceptions of democracy? Socioeconomic status, inequality, and the political status Quo. Comparative Politics, 52(3), 383–403.

- Devine, D. (2024). Does political trust matter? A meta-analysis on the consequences of trust. PolitBehav, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-024-09916-y

- Eatwell, R., & Goodwin, M. (2018). National populism: The revolt against liberal democracy. Pelican.

- Eisinga, R., teGrotenhuis, M., & Pelzer, B. (2013). The reliability of a two-item scale: Pearson, Cronbach, or Spearman-Brown? International Journal of Public Health, 58(4), 637–642.

- Eurostat. (2023). Migration and asylum in Europe – 2023 edition. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/interactive-publications/migration-2023.

- Ford, R., & Jennings, W. (2020). The changing cleavage politics of Western Europe. Annual Review of Political Science, 23, 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-052217-104957

- Fossum, J. (2023). In what sense does right-wing populism pose a democratic challenge for the European union? Social & Legal Studies, 32(6), 930–952.

- Gidron, N., & Ziblatt, D. (2019). Center-right political parties in advanced democracies. Annual Review of Political Science, 22(1), 17–35.

- Grindheim, J. (2019). Why right-leaning populism has grown in the most advanced liberal democracies of Europe. Political Quarterly, 90(4), 757–771.

- Guinjoan, M. (2023). How ideology shapes the relationship between populist attitudes and support for liberal democratic values. Evidence from Spain. ActaPolit, 58, 401–423.

- Haugsgjerd, A. (2019). Moderation or radicalisation? How executive power affects right-wing populists’ satisfaction with democracy. Electoral Studies, 57, 31–45.

- Horonziak, S. (2022). Dysfunctional democracy and political polarisation: The case of Poland. Z VglPolitWiss, 16(2), 265–289.

- Ivarsflaten, E. (2008). What unites right-wing populists in Western Europe? Comparative Political Studies, 41(1), 3–23.

- Jamal, A., & Nooruddin, I. (2010). The democratic utility of trust: A cross-national analysis. Journal of Politics, 72(1), 45–59.

- König, P., & Wenzelburger, G. (2022). Right-wing populist parties and their appeal to pro-redistribution voters. Politics, https://doi.org/10.1177/02633957221125450

- Laclau, E. (2005). On populist reason. Verso.

- Mair, P. (2002). Populist democracy vs party democracy. In Y. Mény & Y. Surel (Eds.), Democracies and the populist challenge (pp. 81–98). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mair, P. (2008). The challenge to party government. West European Politics, 31(1–2), 211–234.

- Mair, P. (2013). Ruling the void: The hollowing of western democracy. Verso.

- Margalit, Y. (2019). Economic insecurity and the causes of populism, reconsidered. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(4), 152–170.

- Mauk, M. (2020). Rebuilding trust in broken systems? Populist party success and citizens’ trust in democratic institutions. Politics and Governance, 8(3), 45–58.

- Mouffe, C. (2000). Deliberative democracy or agnostic pluralism. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Mudde, C. (2007). Populist radical right parties in Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, R. (2012). Populism and (liberal) democracy: A framework for analysis. In C. Mudde & C. R. Kaltwasser (Eds.), Populism in Europe and the Americas (pp. 1–26). Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, R. (2018). Studying populism in comparative perspective: Reflections on the contemporary and future research agenda. Comparative Political Studies, 51(13), 1667–1693.

- Oesch, D., & Rennwald, L. (2018). Electoral competition in Europe’s new tripolar political space: Class voting for the left, centre-right and radical right. European Journal of Political Research, 57(4), 783–807.

- Pappas, T. (2019). Populism and liberal democracy: A comparative and theoretical analysis. Oxford University Press.

- Pichler, F., & Wallace, C. (2009). Social capital and social class in Europe: The role of social networks in social stratification. European Sociological Review, 25(3), 319–332.

- Piketty, T., & Zucman, G. (2014). Capital is back: Wealth-income ratios in rich countries 1700–2010. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(3), 1255–1310.

- Poses, C., & Revilla, M. (2022). Measuring satisfaction with democracy: How good are different scales across countries and languages? European Political Science Review, 14(1), 18–35.

- Putnum, R. (1993). What makes democracy work? National Civic Review, 82(2), 101–107.

- Rensmann, L., de Lange, S., & Couperus, S. (2017). Editorial to the issue on populism and the remaking of (Il)Liberal democracy in Europe. Politics and Governance, 5, 106–111.

- Rodi, P., Karavasilis, L., & Puleo, L. (2023). When nationalism meets populism: Examining right-wing populist & nationalist discourses in the 2014 & 2019 European parliamentary elections. European Politics and Society, 24(2), 284–302.

- Rodrik, D. (2018). Populism and the economics of globalization. Journal of International Buiness Policy, 1(1), 12–33.

- Rooduijn, M. (2015). The rise of the populist radical right in Western Europe. European View, 14(1), 3–11.

- Rooduijn, M. (2018). What unites the voter bases of populist parties? Comparing the electorates of 15 populist parties. European Political Science Review, 10(3), 351–368.

- Rosset, J., & Stecker, C. (2019). How well are citizens represented by their governments? Issue congruence and inequality in Europe. European Political Science Review, 11(2), 145–160.

- Schäfer, A. (2012). Consequences of social inequality for democracy in Western Europe. ZeitschriftfürVergleichendePolitikwissenschaft, 6(2), 23–45.

- Schmidtke, O. (2021). We the people: Demarcating the demos in populist mobilization – The case of the Italian lega. Social Sciences, 10(10), 351–365.

- Schmitter, P., & Hary, T. (1991). What democracy is–and is not. Journal of Democracy, 2(3), 75–88.

- Schneider, I. (2017). Can we trust measures of political trust? Assessing measurement equivalence in diverse regime types. Social Indicators Research, 133(3), 963–984.

- Singh, S., & Mayne, Q. (2023). Satisfaction with democracy: A review of a major public opinion indicator. Public Opinion Quarterly, 87(1), 187–218.

- Spittler, M. (2018). Are right-wing populist parties a threat to democracy? In W. Merkel & S. Kneip (Eds.), Democracy and crisis (pp. 97–121). Springer.

- Stoetzer, L., Giesecke, J., & Klüver, H. (2021). How does income inequality affect the support for populist parties? Journal of European Public Policy, 30(1), 1–20.

- Thomassen, J., & van Ham, C. (2017). A legitimacy crisis of representative democracy?. In C. van Ham, J. Thomassen, A. Kees, & R. Andeweg (Eds.), Myth and reality of the legitimacy crisis: Explaining trends and cross-national differences in established democracies (pp. 3–16). Oxford Academic.

- Turner, T., Ryan, L., & O’Sullivan, M. (2020). Does union membership matter? Political participation, attachment to democracy and generational change. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 26(3), 279–295.

- Valentim, V. (2021). Parliamentary representation and the normalization of radical right support. Comparative Political Studies, 54(14), 2475–2511.

- Van der Brug, W., Fennema, M., & Tillie, J. (2000). Anti-immigrant parties in Europe: Ideological or protest vote? European Journal of Political Research, 37(1), 77–102.

- van der Meer, T., & Zmerli, S. (2017). The Deeply rooted concern with political trust. In T. van der Meer & S. Zmerli (Eds.), Handbook on political trust (pp. 1–16). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Van Mol, C., & de Valk, H. (2016). Migration and immigrants in Europe: A historical and demographic perspective. In B. Garcés-Mascareñas & R. Penninx (Eds.), Integration processes and policies in Europe: Context, levels and actors. IMISCOE Research Series (pp. 31–55). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-21674-4_3

- Zaslove, A., Geurkink, B., Jacobs, K., & Akkerman, A. (2021). Power to the people? Populism, democracy, and political participation: A citizen’s perspective. West European Politics, 44(4), 727–751.