ABSTRACT

While the division between the people and the elite created by populism is typically understood within a national framework, the aim of this article is to analyse how the understanding of the people and the elite is constructed by the use of interwoven scales. By focusing on the scalar politics of the Spanish party Vox, the discursive articulation of space through scales are analysed. By means of a qualitative discourse analysis of six Twitter (now X) accounts of the most prominent leaders, we argue that the use of political spaces is strictly connected to the party’s broader political narrative. Concretely, the analysis of the spatial imaginaries evoked by Vox on Twitter shows the importance of different scales – local, regional, national and global – to organize its populist antagonism spatially. In so doing, this paper makes a contribution to the literature on ‘scalar politics’ of radical right parties, which has recently focused on different geographical constituencies. We argue that the national scale maintains its predominance in opposition to the global scale (dominated by the cosmopolitan elites), the regional one (where separatism represents a threat against Spain's unity), the local scale which is nationalized against migrants and people who do not feel as Spaniards.

Introduction

On the 10th of October 2021, Santiago Abascal, the leader of the Spanish far-right party Vox, posted a tweet which reads: ‘Reclaiming our great and diverse Homeland is the best antidote against globalism and separatism’. (in Spanish: ‘La reivindicación de nuestra Patria grande y diversa es el mejor antídoto del globalismo y del separatismo’ #VIVA21 https://t.co/vqNHWHM4eg). The tweet, which came along with a video of the 2021 party gathering ‘Viva21’, was posted on the occasion of the upcoming celebration of the 12th of October, the Spanish National Day.

In a single tweet, three spatial scales, which are associated with different political values, are set out and presented as connected: the national (homeland), the global (globalism) and the regional (separatism). Given that globalization is associated with the construction of supra and subnational scales (Sheppard, Citation2022), Abascal’s tweet can arguably be seen as a good summary of Vox’s articulation of these scales.

The growing scholarship on Vox has analysed the surge of this political party, explaining the causes of its success, its discourse, its policy agenda, its implication for the whole party system, as well its nationalist-populist nature, and proto-authoritarian rhetoric, among other things (e.g. Ortiz Barquero, Citation2018; Turnbull-Dugarte-, Rama, & Santana, Citation2020). However, there is still a gap in the study of Vox’s spatial politics. Surprisingly, although the scholarship has stressed the party’s combination of nationalism and populist traits (e.g. Ferreira, Citation2019; Rubio-Pueyo, Citation2019), the literature has not yet paid enough attention to Vox’s ways of using political spaces, from the local to the global scale, and how it contributes to its broader political discourse (e.g. Santamarina, Citation2021). This paper finds its starting point with this scientific lack, and it inquiries about the type of spatial scales at the centre of Vox’s political discourse. How does Vox refer to the local, regional, national, and global spatial spaces? How does the references to spatial scales contribute to Vox’s political ideology? How does Vox’s use of social media promote the connection between spatial scales? These are important questions that have so far found limited room in the study of populist and far-right parties.

Being located on the nationalist and populist far-right political spectrum (Rama et al., Citation2021; Santamarina, Citation2020), it is not surprising – as Abascal’s tweet clearly shows – that Vox discursively reinforces the national space against supra and subnational forces. However, there is a scientific need for further exploring the connections between both the populist and the nationalist logics and the different scales (local, regional, national, and global ones). As highlighted by Biancalana et al. (Citation2023, p. 2), ‘populist discourse adapts to subnational, national and supranational scales by incorporating different definitions of in- and out-groups’. To understand this connection better, this article addresses the following research question: How does Vox’s online discourse represent the antagonistic relation between ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’ at different scales? To answer this question, two sub-questions relate to Vox’s ‘scalar politics’: (1) Which are the main spaces used in Vox’s discourse? and (2) Which are the main scales, and how are they interconnected? Quantitative content analysis is used to identify the main spaces and scales as well as their frequency. To examine the formation and interrelation between scales, a qualitative analysis is conducted. Whilst the mapping of spaces and scales is carried out based on tweets by prominent members of the party to get a general impression of Vox’s online discourse, the qualitative analysis focuses only on the tweets of the party leader: Santiago Abascal. The reason is twofold: he is the leader of the party, embodying the values of the party, and, although he is a national politician, he deploys different scales and is not limited to the national one.

In all, we argue that the divide between ‘us’ and ‘them’ is discursively organized at scales. Two hypotheses serve as our starting point: (a) Vox does not appeal to an abstract and general notion of the people, but to a historic and geographic one that varies through scales, as does the enemy: whether the spatial scale is the global (the cosmopolitan elites) or the local one (immigrants); and (b) The nation, for its part, maintains a central position in Vox’s discourse, against both global and regional scales. These hypotheses would confirm the essential role attributed to the national(ist) space and the strategic use of populism to delimitate who the in- and out-groups are at different scales.

The paper is structured as follows. First, it develops an overview about the relationship between space/scale and politics, and links this to the literature on far-right, nationalism, and populism. Second, it sketches out an understanding of Vox’s main ideological and discursive traits. Third, this paper presents the method used for the inquiry. In this regard, content analysis has been deployed in the study of Vox’s communication on Twitter. Fourth, an in-depth analysis is carried out about Santiago Abascal’s Twitter account by combining content and interpretative analyses. Here four scales are detailed and analysed. The discussion stresses the role of these spatialities in the overall discourse of Vox.

SCALAR Politics: the spatial dimension of populism and nationalism

Since modern times, the territorialization of power was established around nation-states and their borders (Jessop et al., Citation2008). From this perspective, the ‘spatiality’ of politics has fundamentally focused on the dichotomy between the inside and the outside of the nation-state, hence the idea of natives and foreigners. Moreover, within the nation-state, space has also been conceptualized in a dichotomous way in terms of centre/periphery and urban/rural. Likewise, outside the nation-state, special attention has been paid to supranational entities, the international alliances, and more broadly, the globalization processes (Galli, Citation2010).

Within populism studies (both right- and left-wing populism), the spatial metaphor horizontal–vertical has been used to compare with and differentiate from nationalism. A distinctive line of research differentiates the two according to the different logics these two phenomena operate through. ‘The nation’ and ‘the people’ are constructed through an antagonist vision that differentiates on the basis of a horizontal axis (those inside versus outside the nation) and a vertical one (those belonging to the people versus those belonging to the elite) (De Cleen, Citation2017). In this sense, while populism operates through the vertical, up–down, line of conflict, the people versus the elite, nationalism would operate through a horizontal line of conflict, dividing the ingroup and the outgroup, those who belong to the national community and those who do not (e.g. Blokker, Citation2005; Jansen, Citation2011).

From geography and border studies, the approach of nationalism (e.g. Richardson, Citation2020) has been questioned. The relevance of scales is introduced to explain how the connection between globalization and rising inequalities of contemporary politics favours populism, proposing itself as the guard of national integrity and national sovereignty (Basile and Mazzoleni, Citation2020; Casaglia et al., Citation2020). Populist radical parties are, besides, ‘grounded in their local, regional, and/or national electoral constituencies, which are moulded within differentiated and complex territorial scales’ (Biancalana et al., Citation2023, p. 3). We share a similar interest in the concept of scale to organize, create hierarchies, and connect spaces.

The notion of ‘scale’ has been used to describe the physical and social organization of the world and to ‘explain and showcase processes of spatial ordering, shaping, exclusion, and other ‘power tools’’ (Prys-Hansen et al., Citation2023). Scales are socially produced and ideological; a process (not a product) that entails drawing distinctions (e.g. what is ‘near’ and what is ‘far’) as well as interconnecting levels, structures, and practices. (Carr & Lempert, Citation2016; Jessop, Citation2009; Prys-Hansen et al., Citation2023). Since scales are social constructions and representations of space, scales are also produced through political struggle. The notion of ‘politics of scale’ reflects the interplay between mechanism of exclusion by prevailing power and of inclusion by political contestation (Blakey, Citation2021). Danny MacKinnon makes an interesting point when he refers to ‘scalar politics’, instead of ‘politics of scale’, claiming that scales are not the ‘prime object of contestation between social actors, but rather specific processes and institutionalized practices that are themselves differentially scaled’ (2010: 22–23).

As mentioned by MacKinnon (Citation2010), ‘scalar politics’ implies that political actors use scalar classifications and discourses to naturalize and legitimize the scaling of particular projects. Radical Right Parties (RRPS) clearly attempt to naturalize the national scale as the only legitimate one in opposition to supranational and even regional powers, but the ‘defence of national sovereignty […] does not preclude their strategic uses of alternative scales in their public discourse’ (Biancalana et al., Citation2023, p. 2).

From our approach, the ‘scalar politics’ of RRPS, and specifically of Vox, is attached to different representations of ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’. Thus scaling populism responds to creating spatial antagonisms through scales. There are two reasons for this: (a) scales show how changes in one spatial entity (e.g. the neighbourhood or the nation) are affected by change at other geographic scales, e.g. the regional or the global one; and (b) scales create vertical hierarchies (Sheppard, Citation2002) that reinforce the vertical divide forged by populism. When focusing on scales, that are nested, the main analytical unit is not the nation, which has been dominant in the studies of populism and nationalism, but the interconnection between the nation and other spatial representations. The verticality of spatial scales implies a hierarchy that parallels and complements the populist-nationalist spatial metaphors – the vertical, up–down, line of conflict between ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’. Consequently, globalization tends to be perceived as an imposition to the nation-state, as subordinated scale, and, conversely, local democracy must be saved from state centralism, for the same reason.

To address these questions, we focus on the Spanish case, and particularly on Vox and its Twitter communication. Before delving into that, we need to sketch out Vox’s main ideological and discursive boundaries.

Vox as nationalist and populist radical right party

Despite Spain being one of the last countries in Europe to experience the rise of the far-right wave, the literature about Vox is fast increasing. Founded in 2013 by ex-members of the conservative People’s Party (PP) who were discontent with the moderate politics attributed to the party leader of the time, Vox attempted to occupy a political space to the right of the PP. Despite its minimal electoral success, Vox positioned itself as a combative conservative and nationalist party, especially after the Catalan referendum for independence in 2017. Vox showed its convening power and ideological rearming at its congress in Vistalegre in 2018. A few months later, Vox obtained its first electoral success in the region of Andalusia in December and has since then gained electoral representation at local and national level. As a result of the general elections in November 2019, Vox obtained 52 parliamentary seats out of 350 at the Congress of Deputies. In the 2023 elections, with 31 seats, Vox confirmed its position as the third largest political party.

Parallel to the party’s success, debates about the nature of Vox have also flourished. Recent literature has underlined how this party fits within the family of populist radical right (e.g. Rama et al., Citation2021; Turnbull-Dugarte et al., Citation2020), while others have insisted on the radical nature of the party, ruling out (or strongly limiting) the populist component (e.g. Barrio, Citation2019; Ferreira, Citation2019; Marcos-Marne et al., Citation2021; Vampa, Citation2020). Camargo Fernández (Citation2021) singles out that, despite the differences associated with the terminologies (extreme right, radical right, and right populism), all of them share the fictious unequal battle between powerful enemies that threaten the patriotic values of the nation.

Nativism is one of the main ideological pillars of Vox, consisting of separating the natives (the nationals) from the non-natives (immigrants), and the consequent criminalization of the latter (Camargo Fernández, Citation2021; Mudde, Citation2007). Santamarina (2020) offers a complementary vision of nativism by using the term ‘xenophobic populism’ to emphasize the combination of nationalism, xenophobia, and populism. According to her, Vox appeals to the Spaniards and, despite their neoliberal program, tries to reach not only the upper classes but also the national working class. Regarding nationalism, besides turning to tradition and nostalgia, Vox ‘appeals to patriotism, the Spanish flag, and the history and traditions of Spain are pervasive in its discourse, and Spaniards are often idealized as holders of deep, positive values’ (Marcos-Marne et al., Citation2021, p. 7).

Initially, Vox used immigrants as scapegoats and gave weight to rural areas (Wheeler, Citation2020). However, Vox has proven its capacity to adapt to the political context and evolve from ‘a traditionally conservative discourse to a more aggressive populist one’ (Olivas Osuna & Rama, Citation2021, p. 13). The party’s ideology is based on Christian values, rejection of multiculturalism, unitary and centralized conception of Spain, and anti-globalism (Olivas Osuna & Rama, Citation2021). While all these components clearly define Vox as far right, its populist nature has been subject of longer discussions. The appeals to the people and the people’s will are not very frequent. However, there is an explicit polarization between ‘us’ (the people) and ‘them’ (the corrupt political elite), although grounded in exclusive nativism and the defence of the national (Sosinski & García, Citation2022). Attempting to account for the peculiarity of Vox’s populism, Franzé and Fernández-Vázquez (Citation2022) talk about ‘inverted populism’, arguing that Vox’s antagonism emerges between Spaniards and allegedly minority groups and ideologies (i.e. feminism, separatism, leftism, multiculturalism), which are seen as opponents to Spain and to the constitutional order.

Drawing on this broad literature that stresses various concerns and nuances about Vox’s nature, in this paper we consider Vox a RRP whose adoption of populist strategy aims to reinforce nationalism. This does not mean that the nation is the only space used by Vox, but the articulation of the people, even as ‘national people’, is produced differently according to the scales. This move implies that scales become essential to understand how Vox’s political antagonism is spatially produced and the extent to which Vox aims to preserve the dominance of the national scale by (a) opposing it to supra and subnational scales and (b) by nationalizing other scales (i.e. ordinary people at the local scale are deprived of their regional traits and only are conceived as ordinary Spaniards).

Data and method

Recent scholarship on social media has shown that Twitter is hugely used by politicians for both campaigning and agenda-building objectives (e.g. Stier et al., Citation2018). Moreover, Twitter has been conceived as a means of polarizing the message (Pallarés-Navarro & Zugasti, Citation2022). However, despite the growing research on Vox’s social media use (e.g. Alonso-Muñoz & Casero-Ripollés, Citation2020; Barbeito Iglesias & Iglesias Alonso, Citation2021; Pérez-Curiel, Citation2020), there is still a need of both quantitative and qualitative analysis of Vox’s online discourse, and particularly for what concerns its spatial narrative. These are the reasons why focusing on Vox’s use of Twitter will allow to explore polarization and socio-spatial divide and the party’s discourse.

The analysis aims to answer the following research questions: How is Vox’s ideology related to its geographical discourse on Twitter? How do Vox’s leaders conceptualize scales such as the global, the national, and the local spaces? To answer to these questions, this article employs content and text analysis. We have opted for a content analysis to map out the content of online communication and to identify the salience of certain themes. Content analysis involves identifying and interpreting patterns of meaning within qualitative data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Besides content analysis, we have also conducted a more in-depth text analysis where we stress the formation of scales in more detail by focusing on a sampled corpus of tweets.

As explained above, the dataset is made of two corpora, one for the quantitative analysis, aimed to map the main spaces used by Vox and their frequency, and another one for the qualitative analysis, centred on the scalar politics of the party leader, Abascal. The first one consists of 6 Twitter accounts of main political leaders, Santiago Abascal, Javier Ortega Smith, Iván Espinosa de los Monteros, Macarena Olona, Rocío Monasterio, and Rocío de Meer. While selecting the Twitter accounts, balance have been sought both in terms of political role – the accounts belong to the six most important and visible leaders within the Party, with an active role in parliament, and in terms of gender – 3 men and 3 women. We chose a 24-month timeframe (1 January 2020 to 1 January 2022) as this sample of data typifies Vox’s discourse on a diversity of issues. In addition, this timeframe covers the first 2 years of Vox’s electoral representation at the national level. Vox entered into the Spanish parliament (after the GE of November 2019), becoming the third most voted force. Moreover, during this timeframe different regional elections also took place: Catalan regional elections in February 2021, and Madrid’s regional elections in May 2021. In addition to that, as the literature has stressed, the COVID-19 pandemic has offered Vox an opportunity to gain further popularity by promoting anti-lockdown protests (Wheeler, Citation2020), and to increase its populist’s strategy and discourse (Olivas Osuna & Rama, Citation2021). For these reasons, the sample of data analysed arguably epitomizes Vox’s discourse ().

Table 1. Number of tweets by account (sum of tweets = 12,081, after retweets removal).

As for the qualitative analysis, the study has focused on Santiago Abascal’s Twitter account. Despite not being the most prominent figure in terms of use of Twitter (see ), Abascal is nonetheless the most visible leader within the party, and he’s been the public face embodying the party’s narrative, and therefore it is worth focusing on his online communication. We chose to zoom in on his communication on Twitter for the qualitative analysis in order to gain an in-depth insight into the articulation of nationalism and space. In this case, the dataset consisted of all tweets from Abascal’s official profile (@Santi_ABASCAL) during the period 1 January 2021 to 1 January 2022. For the qualitative analysis, since the huge number of tweets, we have used these keywords to filtrate the huge number of tweets (a total of 3199 between tweets and retweets) and to identify the most relevant ones for the purpose of our research. These keywords, being representative of the different spatial organizations of scales, are: ‘barrio’ (neighbourhood, and its plural), ‘Madrid’, ‘Cataluña’, ‘comunidad autónoma’ (autonomous community, and its plural), ‘España’, ‘nación’ (nation), ‘patria’ (homeland), ‘global’ and ‘globalista(s)’ (globalist, and its plural). The tweets have therefore been sampled so that at least one of them feature in the tweet. The resulting sample was analysed by means of content and text analysis, as a method to understand Abascal’s discourse, seeking to identify his discursive interpretations of the main spatial dimensions, and how these shape the content of his discourse.

Table 2. Percentage of each theme in six main Twitter accounts associated to Vox.

The analysis for this paper has been computer-assisted using Atlas.ti. The coding has been both deductive and inductive, since the tweets went through a thorough reading that enabled us to identify empirically the types of scales and the actors and values associated with those spaces. The quantitative coding of the tweets was carried out by one coder (Cossarini) to ensure consistency (see codebook below), whereas the qualitative analysis of the tweets was done collectively by the authors. As for the qualitative analysis, we illustrate Abascal’s discourse with excerpts from his tweets.

Content analysis

Prior to a more in-depth interpretative analysis, we conducted a content analysis to map out the content of the tweets and identify the salience of themes associated to the diverse geographical spaces. Two specific sets of codes stand out in the quantitative analysis: nationalism/sovereignty and nativism. The first brings together codes centred on territorial ideas, such as Spain, Catalonia, nation, Madrid, patriotism, sovereignty, separatism, populism, Europe, neighbourhood. The second group codes centred on nativism and issues related to security, such as Frontiers, immigration, insecurity, invasion, protection.

We argue that these macro themes allow us to grasp the overall picture of Vox’s discourse on Twitter, and to illustrate the major discursive lines of Vox, which (a) are useful to confirm general considerations about the political nature of Vox and (b) will guide the more in-depth analysis about the ‘spatialities’ in Vox’s online discourse.

shows the percentage of these themes, revolving around key dimensions of Vox’s discourse. Unsurprisingly, the percentage of nationalism/sovereignty-related topics appears in an average of over 40 per cent in all political leaders, reaching 51 per cent in Ortega Smith. Nativism-related topics appear in an important percentage, from 9 per cent of Monteros and Olona to 21 per cent of De Meer.

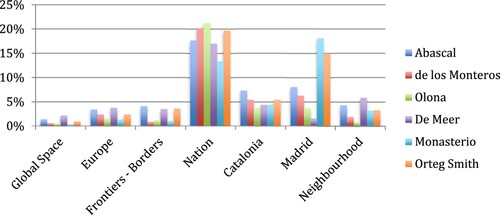

Thus the overall narrative of Vox is highly focused on nationalism and sovereignty-related issues. If we focus on the percentages of each of the terms directly related to the different spaces, as in , we can account for the weight that the Vox leaders give to each of the macro territorial themes. Indeed, Graph 1 shows the percentages for each leader’s discourse for each spatial scale and geographical reference. It is evident, and at the same time hardly surprising, that there is a predominance of tweets in which the nation is mentioned, which in this case includes the term ‘Spain’. ‘Madrid’ and ‘Catalonia’ are the following spaces.

Graph 1. Percentage of tweets containing specific space-related topics (*‘Nation’ also includes the term ‘España`).

The conceptualization of space is predominantly associated to the ‘territoriality’ of Spain, and it is attached to national sovereignty. Sovereignty itself, however, is internally and externally delimitated. Internally, sovereignty is discursively conceived in relation to the centrality of Madrid as capital city of Spain, and in relation to Catalan separatism as threat for the Spanish territorial unity. Externally, sovereignty is patently associated to borders and migration. This territoriality in Vox’s online discourse is further reinforced by the use of specific hashtags, such as #RecuperemosCatalonia, #ProtegeMadrid, and #EspañaSiempre, as shown in .

Table 3. Most frequent hashtags in the leaders’ account.

The geographical scales in the online discourse of Vox

While the thematic analysis delineates the boundaries of the discourse, the text analysis of the tweets of these leaders of Vox generates more in-depth insights into the way this political party conceptualizes the different spatial imaginaries.

In this section, we advance a conceptualization of how socio-spatial relations are organized into four scales, from the local to the global dimension: the neighbourhood, the regional dimension (specifically epitomized by the centralist vision on Madrid, and the ‘peripheral’ areas, such as Catalonia), the national, and the global one. Whilst the selection of the national and global scales is made from the traditional division into scales, we decided inductively to focus on: (1) Madrid vs. Catalonia as a way to produce territorial antagonism and (2) neighbourhood as the most prominent space used by Vox to express antagonism between nationals and immigrants. To carry out this interpretative analysis, we focus on the party leader Santiago Abascal’s official account (@Santi_ABASCAL) over 12 months, from January 2021 to January 2022, for a total number of 3199 tweets and retweets.

Particular attention has been paid to shorter specific timeframe, as relevant events have occurred during the 2021, such as the Catalan Elections in February 2021, the regional election in Madrid, in May 2021, and the Vox national act ‘Viva 2021’, in October 2021. Data have been gathered, sampling tweets from 1 month before to 1 month after such events.

As shows, by mapping out the most frequent words in Abascal’s twitter accounts, it is possible to give an account of the extent to which the leader of Vox’s discourse is significantly associated to spatial and geographical imaginaries. Spain (España) and Spaniards (Españoles) are the two most frequent terms, followed by other spaces such as Madrid, Catalonia (Cataluña), borders (fronteras), and Ceuta (the Spanish enclave city on the north coast of Africa). Given this context, it is possible to delve into the four scales, the global, national, regional, and local dimensions. For the qualitative analysis, we identify two scalar strategies that show how the national scale plays a central role: scaling up, where especially the global is connected to the national as external interference, and scaling down, where the local and the regional are shaped by references to the nation.

Table 4. 20 most frequent words in Abascal’s twitter account.

Global scale: ‘The future doesn’t belong to the cosmopolitan forces of the progressive left’

Despite the fact that references to the global scale are not the most frequent in Vox's discourse, nor in Abascal's, this dimension has a peculiar relevance since it is, as the quote that opens this paper suggests, a space to which as it is necessary to confront and provide an ‘antidote’. Data is revealing in this regard: in Abascal's tweets, ‘globalist’ and ‘globalists’ appear a total of 41 times, compared to the more than 500 of ‘Spain’. However, this scale is central, insofar as it defines – by opposition, and as the space of the left and cosmopolitanism – the national scale, the space of the patriots. It also creates a sense of hierarchy, the global as vertical imposition over the (horizontal) national.

Abascal is crystal clear when defining his diagnosis of the current social and political context. On 16 January 2021, on the occasion of a transnational meeting with far-right leaders from Europe and the Americas, Abascal retweeted a post from La Gaceta de la Iberosphera (@gaceta_es) an online newspaper linked to Fundación Disenso and Vox, in which it reads:

The future belongs to the patriots, the globalists will be defeated and will not be able to suffocate freedom.Footnote1

The globalists and the left are frightened, they have perceived that the future no longer belongs to them, that it belongs to the patriots.

Globalists must be confronted firmly, according to Abascal, since ‘submission to supranational powers and the liberal consensus condemn rural Spain to misery and depopulation’ (tweet of 19 October 2021). In this case, globalism is a threat to rural areas that suffer from the processes of globalization, being the recovery of national sovereignty the only implicit solution.

The way in which Abascal refers to his enemies is explicit and aims to delegitimate them: ‘caviar activists’ who are committed to an agenda that – according to the leader of Vox – is ‘totalitarian’ and ‘globalist’. The following tweet from 2 November 2021, with a video of Joe Biden closing his eyes during the Glasgow climate summit, where it reads, shows the pejorative characterization Abascal makes of the elites:

Globalist billionaires, caviar activists and outcast politicians. They call the climate summit the classism of all life: luxuries for the elite and relocation, poverty, unemployment, energy dependence, depopulation and ruin for workers and families.

National scale: unity, anti-globalist, and pride of the past

By opposition to the global scale, Vox focuses its political discourse on the national scale as true political space. The central ‘spatiality’ of Vox’s discourse revolves around the nation: Spain. The same term ‘Spain’ appears 500 times in Abascal's tweets, as well as the mention of ‘the Spaniards’ up to 476 (significantly, the use of the female gender when Abascal refers to ‘the Spaniards’ is very limited, only 4 times). Likewise, the idea of ‘nation’ appears 28 times, 31 that of ‘homeland’, and 47 that of ‘patriots.’

Looking at co-occurrences, as in , helps us locate Abascal’s tweets in his larger narrative, as well as delineate the discursive framework he uses when talking about Spain. In fact, it can be seen through which other values, actors, and themes the leader of Vox associates his country with concepts of ‘freedom’, ‘working class’, and ‘enemies’, are the first three words, followed by the concept of ‘sovereignty’.

Table 5. Co-occurrences of the term ‘Spain’ in Abascal’s tweets.

The fact that Spain, in Vox’s discourse, is linked to the idea of freedom, to the working class, and is talked about by mentioning its ‘enemies’ characterizes the general narrative of the Vox leader’s discourse. This could be summarized as follows: Spain, in its unity and sovereignty, represents true freedom for the working class, against Spain’s enemies who want to destroy it. On occasion of May 1, the International Workers’ Day, vox tweets a video of Abascal, in which the leader rejects any internationalist spatial imaginary and conceives that workers share their national belonging rather than being exploited by the global labour conditions of the capitalist system:

The true anthem of the workers of Spain is not the International but the anthem of our Homeland. #WorkerAndSpaniar

In this context, the ideas (and hashtags) of ‘traitor’ (mostly in reference to Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez) and ‘coup plotters’ (in reference to pro-independence Catalan politicians) are frequent in Abascal's tweets that speak of the dangers for the ‘unity’ of Spain. Abascal constructs a spatiotemporal representation of Spain as a continuum between the past and the future.

Faced with whom Abascal calls traitors, or the ‘government of ruin’, Vox intends to ‘give back [to the Spanish] the Spain they deserve’: In a tweet from 2 March 2021.

Spain walks towards the abyss with the Government of the ruin. While the families try to survive, the social-criminal government spends millions on its ideological deliriums. VOX will work every day to give you back the Spain you deserve.

Disguised as a gesture against racism, some insist on bringing nations to their knees, as we are seeing in sports. Spain must not kneel before those who insult our history and the legacy of a nation that never looked at the colour of the skin. #SpainDoNotkneel

The tension between the global powers and the nation-state can also derive into scale bending (Smith, Citation2004), when the scale at which political activities fit properly is challenged and, consequently, at stake. In these cases, Vox opts for claiming the appropriateness of the national scale. When, for example, the Report of the Council of Europe in June 2021 criticized the trial in Spain against Catalan pro-independence politicians (pardoned by the Pedro Sánchez’s government on the 23rd of June 2021), Abascal attacked that European institution and considered that solving the issue at the European level would go against the Spanish institutions and history:

The Council of Europe approves a report full of lies. Once again, Sánchez tolerates that our institutions remain at the feet of the propagandist horses of the Black Legend: neither yesterday nor ever will you be able to with Spain. Nobody plays with our sovereignty.

Regional scale: negating diversity and autonomy, promoting centralism

The regional dimension is extremely relevant in the Spanish political context, as this is characterized by a decentralized structure with a quasi-federal character, and with important territorial tensions and separatist dynamics. In this context, Vox devotes an important part of its online narrative to the regional dimension.

With a Tweet from 20 May 2021, complemented by a video of a rally from Cordoba, Abascal clearly synthesizes the centralist vision of Vox, rebelling (at least rhetorically) against the administrative division of Spain into 17 Autonomous Communities.

Spain needs an alternative, and not seventeen #Córdoba #GraciasCórdoba

On the elections in Catalonia, Abascal compares the territorial secession with the division in society and in families. Vox is precisely needed, as it is to only able to restore the territorial and societal order by getting back to a unitary situation. In the days before the Catalan regional elections, Abascal tweets (on 9 February 2021):

Separatism has broken Catalonia. It has divided society, and it has divided families. #GettingBackCatalonia #GettingBackSpain

Whilst Catalonia is threatened by separatist, Madrid represents the spatial imaginary of resistance ‘against communists and socialists’, especially ensuring Vox’s role in power. The territorial importance of Catalonia to maintain the Spanish unity and of Madrid to reinforce the conversative ideology explains why the regional scale is framed exclusively from a national perspective.

Local scale: leftist politics has brought insecurity and migrant criminality to our ‘neighbourhoods’

The local scale becomes important for Vox’s discourse and its representation of workers and ordinary people in place. It materializes both at rural and urban places. We focus, in particular, on ‘neighbourhood’ as the place of (re)producing identity and sense of belonging. It should be noted that, in Abascal's tweets, terms such as ‘barrio’ and ‘barrios’ appear a total of 131 times. As indicated by the analysis of co-occurrences, one of the most notable elements of the is the relationship that the local scale is strongly associated with immigration and insecurity. In fact: ‘immigration’ appears 65 times linked to the neighbourhood, while ‘insecurity’ it does so 53 times, ‘anti-left’ 27, ‘the working class’ 17, the idea of ‘invasion’ 12 times and 11 the idea of ‘get back’.

In addition, as evidenced by some of the most viral tweets, these issues are related to the ‘invasion’ by immigrants, criminality, law and order, and the idea of ‘ get back’ control.

On occasion of the electoral campaign for the regional elections of Madrid, Abascal focused on linking the insecurity of the neighbourhoods of the city with immigration and the increase in crime that this would entail. These criminals, he insists, would ‘impose’ their violence in the neighbourhoods. The formation of ‘us’ and ‘them’ is inseparable from the spatial scale formation (the neighbourhood, the city, and the nation). On 2 April 2021, Abascal tweeted: ‘We will not allow criminals to continue imposing their violence in Madrid, or anywhere in Spain. We will expel illegals and foreigners who commit crimes. Let's take back our neighbourhoods’.

Another important electoral target for Vox was migrant minors not accompanied by parents or guardians (MENAS), present in the neighbourhoods through the centres of reception. Whilst Abascal attributes insecurity to migrant minors and the responsibility to the government, the solutions would require security and freedom. On April 20, Abascal tweeted:

Today in the neighbourhood of #Hortaleza #Madrid with the neighbours demanding security and freedom in the streets, destroyed by the left that imports Foreign Unaccompanied Minors and illegals while discriminating against Spaniards and destroying their neighbourhoods. #VOX #ProtectMadrid #VoteSafe

Today we are in #Vallecas together with hundreds of VOX supporters who have been stoned with impunity by the brigade members of Iglesias and with the complicity of Sánchez and Marlasca. Neither with stones, nor with sticks, nor with shots. VOX does not take a step back!

In the neighbourhood of #Vicálvaro with Rocío Monasterio @monasterioR together with the neighbours explaining our proposals to recover the security and prosperity that the left has stolen from the neighbourhoods of Madrid. #ProtectMadrid

Thus the local scale is presented as a threatened space due to the criminality of immigrants and the lack of economic prosperity for Spaniards. Vox scales up the responsibility for this situation by blaming the national policies of the left Spanish government.

Conclusion

Scales work as a form of organizing and ordering spaces by creating connections, exclusions, and hierarchies. We have focused on the scalar politics deployed by Vox to show how the party legitimizes the national scale as the ‘natural space’ for politics through prioritizing and connecting it with other scales. When interconnecting scales, Vox produces spatially different representations of the antagonism between ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’. The conceptual framework on scales gives a different angle on the diverse ideological components of RRPS (nativism, nationalism and populism) as we highlight the importance of connecting scales to shape ‘the people’, not as a homogenous entity, and of the nationalization of scales. Rather than utilizing (only) the vertical metaphor of ‘the people’ versus ‘the elite’, Vox divides the political space vertically between the global scale, filled with cosmopolitan and leftist values, and the national scale, associated with patriotism. Moreover, rather than appealing (only) to the ethnic nation, Vox presents the regional and local scales as nationalized scales in opposition to the global dimension.

National sovereignty, as shown in the paper, is presented by Vox as the solution to global interference, whilst the heartland offers the sense of preserving the community and history against spatiotemporal threats. The importance of the nation relies likewise on the connection between scales. Globalization, as the space occupied by globalists, creates a hierarchy upon the nation, the space of the patriots. Consequently, the problems and threats are scaled up and responsibility attributed to global elites, who become essential to reinforce the sense of belonging of the national community. Likewise, the process of scaling down is very important. Nation- and state-related frames are also used at the regional and local scales, and both the local and regional scales become nationalized. The ordinary people of the neighbourhoods are presented as ‘ordinary Spaniards’, incarnating the national values in the cities. The local scale offers a materiality and proximity, which are not present in other scales. Although migrants are presented as a territorial problem to be solved by border control, migrants are a ‘real’ threat and cause of insecurity when spatialized in the neighbourhoods. The ‘decent’ Catalans are, in reality, Spaniards who share the same sense of patriotism and oppose any attempt of increasing autonomy or sovereignty. Whereas, when the scale refers to the state, but not the nation, Vox’s discourse is mainly focused on attributing responsibility to the central government for causing insecurity, division, and poverty locally. This shows that antagonism is scaled up, at different levels. Besides scaling it up to the global elites, the antagonist logic is articulated also towards the national elites, when it comes to single out the opponents of the local or regional scales.

However, it is worth noting that the scale-up strategy that Vox uses to create hierarchic antagonism between global and national is avoided within the Spanish nation: contrary to the state, which is associated to the central government, Vox avoids reproducing spatial vertical metaphors between the national – meaning by that the Spanish nation – and the regional and local scales. The reason is that Vox aspires to a strong centralized nation-state without the existing administrative division into regions (Comunidades Autónomas). That could be perceived as an imposition of the state upon the regions and even cities where the state would impose its will, away from the everyday life and concerns of ordinary people. Thus, as analysed in the paper, it is important for Vox to nationalize the other scales and show that a government led by Vox would protect the ordinary people against local and global threats.

Overall, this paper has connected complementary fields of research on nationalist and populist politics and argued that the antagonist logic of these phenomena – taking Vox as a case study – is inextricable from the geographical narrative. While it seems clear, as a recent strand of literature is arguing (e.g. Chou, Moffitt, & Busbridge, Citation2022; García Agustín & Cossarini, Citation2023), that the geographical appeal of populism cannot be overlooked, this paper has contributed to the theoretical and empirical analysis of the spatial dimension in the online narrative of Vox: the articulation of the meanings of ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’ is performed by Vox through continuous references to spatial imaginary, that is, concrete territorial and spatial dimensions. Making a case for the value of this spatial imaginary – as we have done in this paper – is indeed a way to expand our understanding of nationalist and populist radical right politics.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (29.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Translations are our own. Original tweet in Spanish annexed.

References

- Alonso-Muñoz, L., & Casero-Ripollés, A. (2020). Populism against Europe in social media: The eurosceptic discourse on twitter in Spain, Italy, France, and United Kingdom during the campaign of the 2019 European parliament election. Frontiers in Communication, 5, 54. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2020.00054

- Barbeito Iglesias, R., & Iglesias Alonso, Á. (2021). Political emotions and digital political mobilization in the new populist parties: The cases of Podemos and Vox in Spain. International Review of Sociology, 31(2), 246–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906701.2021.1947948

- Barrio, A. (2019). Vox, la fin de de l’exception espagnole. Fondation pour l’Innovation Politique (Fondapol).

- Basile, L., & Mazzoleni, O. (2020). Sovereignist wine in populist bottles? An introduction. European Politics and Society, 21(2), 151–162.

- Biancalana, C., Lamour, C., Mazzoleni, O., Yerly, G., & Carls, P. (2023). Multiscalar strategies in right-wing populism: A comparison of west European parties in borderlands. Territory, Politics, Governance, 1–20.

- Blakey, J. (2021). The politics of scale through Rancière. Progress in Human Geography, 45(4), 623–640.

- Blokker, P. (2005). Populist nationalism, anti-Europeanism, post-nationalism, and the East–West distinction. German Law Journal, 6(2), 371–389. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2071832200013687

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Camargo Fernández, L. (2021). El nuevo orden discursivo de la extrema derecha española: de la deshumanización a los bulos en un corpus de tuits de Vox sobre la inmigración. Cultura, Lenguaje Y Representación, 26, 63–82. https://doi.org/10.6035/clr.5866

- Carr, E. S., & Lempert, M. (2016). Scale. Discourse and dimensions of social life. University of California Press.

- Casaglia, A., Coletti, R., Lizotte, C., Agnew, J., Mamadouh, V., & Minca, C. (2020). Interventions on European nationalist populism and bordering in time of emergencies. Political Geography, 82, 102238.

- Chou, M., Moffitt, B., & Busbridge, R. (2022). The Localist Turn in Populism Studies. Swiss Political Science Review, 28(1), 129–141.

- De Cleen, B. (2017). Populism and nationalism. In C. R. Kaltwasser, P. A. Taggart, P. O. Espejo, & P. Ostiguy (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of populism (Vol. 1., pp. 342–262). Oxford University Press.

- Fernández Riquelme, P. (2022). Communism or freedom: Right-wing populist discourse and the false disjunctives. In J. J. Gómez Gutiérrez, J. Abdelnour-Nocera, & E. Anchústegui Igartua (Eds.), Democratic institutions and practices. A debate on governments, parties, theories and movements in today’s world (pp. 105–123). Springer.

- Ferreira, C. (2019). Vox as representative of the radical right in Spain: A study of its ideology. Revista Española de Ciencia Política, 51, 73–98. https://doi.org/10.21308/recp.51.03

- Franzé, J., & Fernández-Vázquez, G. (2022). El postfascismo de Vox: un populismo atenuado e invertido. Pensamiento al margen, 16, 57–92.

- Galli, C. (2010). Political spaces and global war. University of Minnesota press.

- García Agustín, O., & Cossarini, P. (2023). The image of the urban people: Visual analysis of the spatialised demos of left-wing populism in Madrid. Javnost, 30(4), 603–621. https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2023.2170614

- Jansen, R. S. (2011). Populist mobilization: A new theoretical approach to populism. Sociological Theory, 29(2), 75–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9558.2011.01388.x

- Jessop, B. (2009). Avoiding traps, rescaling the state, governing Europe. In R. Keil & R. Mahon (Eds.), Leviathan undone? Towards a political economy of scale (pp. 87–104). University of British Columbia Press.

- Jessop, B., Brenner, N., & Jones, M. R. (2008). Theorizing socio-spatial relations. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 26(3), 389–401. https://doi.org/10.1068/d9107

- Mackinnon, D. (2011). Reconstructing scale: Towards a new scalar politics. Progress in Human Geography, 35(1), 21–36.

- Marcos-Marne, H., Plaza-Colodro, C., & O’Flynn, C. (2021). Populism and new radical-right parties: The case of VOX. Politics, 2021, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/02633957211019587.

- Mudde, C. (2007). Populist radical right populist parties in Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Olivas Osuna, J. J., & Rama, J. (2021). COVID-19: A political virus? VOX’s populist discourse in times of crisis. Frontiers in Political Science, 3, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.678526

- Ortiz Barquero, P. (2019). The electoral breakthrough of the radical right in Spain: Correlates of electoral support for VOX in Andalusia (2018). Genealogy, 3(4), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3040072

- Pallarés-Navarro, S., & Zugasti, R. (2022). Santiago Abascal’s Twitter and Instagram strategy in the 10 November 2019 General Election Campaign: A populist approach to discourse and leadership? Communication & Society, 35(2), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.35.2.53-69

- Pérez-Curiel, C. (2020). Trend towards extreme right-wing populism on Twitter. An analysis of the influence on leaders, media and users. Communication & Society, 33(2), 175–192. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.33.2.175-192

- Prys-Hansen, M., Burilkov, A., & Kolmaš, M. (2023). Regional powers and the politics of scale. International Politics, 61(1), 13–39. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-023-00462-8

- Rama, J., Zanotti, L., Turnbull-Dugarte, S. J., & Santana, A. (2021). VOX: The rise of the Spanish populist radical right. Routledge.

- Richardson, P. (2020). Rescaling the border: National populism, sovereignty and civilizationism. In J. Scott (Ed.), A research agenda for border studies (pp. 241–262). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Rubio-Pueyo, V. (2019). Vox: A new far right in Spain. Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung.

- Santamarina, A. (2021). The spatial politics of far-right populism: VOX, anti-fascism and neighbourhood solidarity in Madrid City. Critical Sociology, 47(6), 891–905. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920520962562

- Sheppard, E. (2002). The spaces and times of globalization: Place, scale, networks, and positionality. Economic Geography, 78(3), 307–330.

- Smith, N. (2004). Scale bending and the fate of the national. In E. Sheppard & R. B. McMaster (Eds.), Scale and geographic inquiry: Nature, society, and method (pp. 192–212). Blackwell.

- Sosinski, M., & García, F. J. S (2022). “Efecto invasion”. Populismo e ideología en el discurso político español sobre los refugiados. El caso de Vox. Discurso and Sociedad, 16(1), 149–172.

- Stier, S., Bleier, A., Lietz, H., & Strohmaier, M. (2018). Election campaigning on social media: Politicians, audiences, and the mediation of political communication on Facebook and Twitter. Political Communication, 35(1), 50–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2017.1334728

- Taggart, P. (2002). Populism and the pathology of representative politics. In Y. Mény & Y. Surel (Eds.), Democracies and the populist challenge (pp. 62–80). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Turnbull-Dugarte, S. J., Rama, J., & Santana, A. (2020). The Baskerville's dog suddenly started barking: Voting for VOX in the 2019 Spanish general elections. Political Research Exchange, 2(1), 1781543. https://doi.org/10.1080/2474736X.2020.1781543

- Vampa, D. (2020). Competing forms of populism and territorial politics: The cases of Vox and Podemos in Spain. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 28(3), 304–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2020.1727866

- Wheeler, D. (2020). Vox in the age of COVID-19: The populist protest turn in spanish politics. Journal of International Affairs, 73(2), 173–184.