ABSTRACT

U.S. cities annually spend over $6 billion in building and maintaining public parks that afford places for social and physical activity. However, adolescent tendencies toward physical inactivity and sedentary behavior continue to increase and may be due to social and physical barriers that limit affordances to public space. The trend suggests that urban researchers should revisit adolescent place needs. Building upon the urban socio-ecological model, I suggest that social media is a social ecosystem service in adolescent placemaking. As part of the socioecology of youth, social media – especially video in Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, and Instagram creates opportunities for feedback and behavioral loops that inform young people of new affordances. The urban socioecological model identifies social media as an ecological post-affordance–experience and peer support not immediately afforded by the visible, physical environment. The phenomenological study builds upon 6,686 downloaded, indexed, and coded scenes from 998 videos to identify three salient place-based categories of adolescent play behavior in five U.S. cities. The place-categories are then interpreted for urban design theory using three influential urban theorists, Bachelard, de Certeau, and Benjamin. Findings suggest that social media makes the real ‘real’ and provides a key mechanism to enhance adolescent affordances in public space.

Introduction

Social media is transforming the way adolescents perceive, play, and re-imagine place. Urban researchers and designers can benefit from this trend and participate in the transformative power of place to improve youth outcomes. Transformative power refers to those unanticipated experiences with the environment that change or transform our worldview (Sarkar Citation2012). Both natural and cultural entities may contain a transformative power that, for good or bad, either go beyond preference (demand/instrumental value) or a known intrinsic value. In other words, the aura of place, how it is perceived in a particular situation or setting, is always subject to the changing cultural values placed on it (i.e. Confederate monuments), for good or ill (Benjamin and Arendt Citation1986). The paper suggests that the transformative power of the environment captured and shared through social media acts a socioecological post-affordance (Brofenbrenner Citation2000).

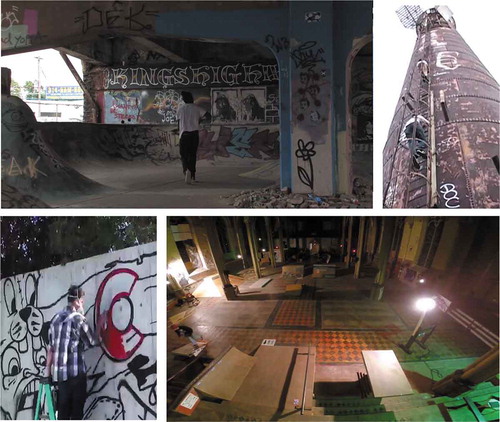

Figures 9–12. Skating in a massive DIY skate park, climbing in an abandoned industrial site, graffiti, and a skate-park built inside an abandoned church demonstrate the transformative nature of ‘city play’. Screen captures of adolescent ‘no place for play’ categories were collected from online sources.

Social media makes the real ‘real’ through reflexive properties like functional, ecological models. However, aside from the life world of the individual, social media is not a function of the immediate, physical environment. Using big data on a human play in cities from across the globe, I will discuss how social media challenges the instrumental or intrinsic value of place with a socially produced representational value that situates play in space (Lefebvre Citation1991). The transformative power of place implies that built environments should be considered beyond objective measures (hot, cold, polluted, clean, green, natural) to include the individual’s (age, gender, race, ethnicity, ability, status, orientation, vulnerability, etc.) relation (observable activity, socializing, playing) with place. A transformative model of place acknowledges that the urban space of affordances shape and are shaped through human activity. Building upon urban ecological theory (Nassauer Citation2012), the transformative power of place would include relevant ecosystem services, feedback loops, and reflexivity as key to understanding the human-environment relationship. I contend that social media is a socio-ecosystem service. The paper begins by (1) revisiting affordances and the need to go beyond structuralist and functionalist theories of causal human relations to the environment; (2) presents the methods and approach for the current study; (3) develops three salient categories from social media related to adolescent play in cities; and, (4) closes with an interpretation of the categories in the context of urban theory and practice. The approach employs empirical methods but is primarily a phenomenological investigation into the symbolic place of adolescent play in cities, observed, interpreted, and described through their post-affordances of city play.

From affordances to post-affordances

Affordance is a term developed through ecological psychology to understand the ‘perceivable meanings of objects’ (Heft Citation1989). Currently, the most referenced definition of affordance is from E. Gibson: ‘the fit between an animal’s capabilities and the environmental supports and opportunities (both good and bad) that make possible a given activity,’ which is often incorrectly attributed to her husband J.J. Gibson. This definition was actually penned by Eleanor Gibson, also an ecological psychologist, who researched environmental perception and the visual cliff (Gibson and Pick Citation2000). The definition is highly functional – the environment is reduced to its practical fit towards the individual – and it differs from an earlier definition. Defined by J.J. Gibson, ‘the affordances of the environment are what it offers the animal, what it provides or furnishes, either for good or ill’ (Gibson Citation1979). This earlier definition reflects the social Spencerism of Spencer, Morgan, and Darwin in its survival of the fittest overtone. The environment is dichotomized by survival outcomes, unmediated by the actual growth, ability, change, and interdependence of the individual and environment. Both definitions include moral outcomes, good and bad, good or ill, implying some cultural variability due to social norms. Outside of survival or fit, such norms may not actually be good or bad for the individual, society, or ecosystem. Both definitions also imply predetermined environmental antecedents that discount the historic origin of the material environment, i.e. some environments, like ghettos, may be structured by society to segregate people based on race and afford poor outcomes better that positive outcome. Most importantly, the transition, from J.J. Gibson’s earlier definition where the individual is a passive receiver of what the environment offers, to a focus on the active fit of an individual, emphasizes a shift away from ecological determinism to functionalism. The change is that affordances are interpreted in relation to the abilities and capabilities of the individual, implying individual level variability. For our purposes, affordance will be defined following the work of Harry Heft: ‘Affordances constitute the ecological resources of the environment that may be utilized by the individual’ (Heft Citation1989). Heft’s emphasis on the individual’s volition, may be utilized, is an important third step in the evolving definition of affordance: (1) what it (the environment) offers, (2) the fit between, and (3) that may be utilized. By recognizing the agency of the individual, affordance moves further from a model of ecological determinism and functionalism towards one of reciprocal determinism or interdependence. Additionally, Heft eliminates the moral dichotomy as an excuse for individual or environmental outcomes.

Built environment researchers often use affordances to refer to an individual’s physical, social, technological, or behavioral dependency on a setting (Voorhees et al., Citation2011) and risk falling into the trap of ecological determinism. Ecological determinism, the idea that the environment predisposes classifiable groups on certain trajectories, is responsible for theories that biological or environmental antecedents shape individual and sociocultural outcomes (Harris Citation1968) and has been used to justify institutionalized racism, poverty, obesity, sexism, and eugenics. Such theories fall victim to the ecological fallacy – that what is true of the group is also true of the individual. Similarly, place-based ecological determinism can be traced to wilderness theories, bio philia’s restorative good of nature, and the crippling stress of cities. The need for false dichotomies, good or bad, good or ill, persists in ‘nature or city’ affordances due to a deterministic or functionalist model of the environment and a rejection of interdependence. Instead, as suggested by Carolyn Voorhees et al. (Citation2011) in their study on adolescent neighborhoods, the environment can have a direct or mediated influence on behaviors due to reciprocal determinism between the developing cognition of the individual, environmental, and behavioral factors.

Reciprocal determinism suggests that affordances describe an individual’s relation to place as determined and mediated by the history of the place and the individuals previous experience, i.e. not all adolescents will have similar outcomes due to fit or ability within similar ecological contexts – social factors like race, gender, fashion, and peer groups also affect outcomes. Since the developmental process is highly influenced by parental figures, peer groups, and other adult figures, like coaches, mentors, pastors, etc. (Patnode et al. Citation2010), further study along the lines of reciprocal determinism and interdependence would benefit from a socio-ecological approach (Bronfenbrenner and Evans Citation2000) to understand the affordances of place. Affordances need to account for the capacity of the individual to acquire new reflexive knowledge – information specific to one’s own situation – that enables them to adapt and adapt place to support all activity, even play. This is an important contribution to the study of affordances for adolescents in built environment research, especially given the status quo perception of unsupervised adolescents as delinquents (Shirtcliff Citation2015a, Citation2015b).

A post-affordance model acknowledges the role of reflexivity from social media to impact contemporary adolescents’ interpretation of the physical environment. Social media, typically framed around the interest of the individual, contributes to the interpretations of affordances as socio-ecological resources. Further, adolescents’ divergent interpretations may better reflect their unique capacity and cognitive plasticity to creatively play with available ecological resources. As multiple researchers show, the cognition of the adolescent individual is characterized by a period of developing from child-like views of the world (Ellis et al. Citation2012), increased focus on peer evaluation (Guyer et al. Citation2014), challenging such perceptions as well as the views of adults, and developing a more independent identity in relation to the larger world. Following Heft, the individual, particularly the developing adolescent with a growing repertoire of interpretations of the built environment ‘expands and differentiates’ and ‘new affordances in the environment are discovered’ (Citation1989). The developing or plasticity of adolescents’ awkward period of adult-‘immaturity’ suggests, following Heft and Bjorklund, an extended period for them to play or try on different roles, and such play permits flexibility. Bjorklund, along these lines, suggests the cognitive development of adolescents benefit from a ‘developmental immaturity’ that has ‘an adaptive role in human phylogeny and that it continues to have an adaptive role in human cognitive and social ontogeny’ (Citation1997, p. 3). Bjorklund attributes such play, new interpretations, and experimentations as key to innovations that improve human phylogeny. Or, in addition to their own physical and cognitive development, ‘adolescent immaturity’ (behavioral neoteny) has a transformative power that potentially helps the individual and society adapt to environmental and social changes. Play may be one of the most important human characteristics guiding individual and societal development.

Play and the plasticity of the developing adolescent presents a unique window into understanding the affordances of place. Ecological affordances do not determine the social utilization of the physical environment. The ability to discover new affordances and play with ecological resources in new and innovative ways reflects a plasticity that, as Bjorklund suggests, plays an important adaptive role in the development of immature adolescents into competent adults as well as the adaptation of society to the greater socioecological challenge. In this perspective, affordances are still viewed as contributing to the experience of the individual in relation to place, but are no longer limited to ecological determinism, structuralist, or functionalist outcomes. As a post-affordance, described below, social media can be seen as an influential socio-ecosystem resource mediating adolescent behavior.

Playing in the city is fun but somehow sharing it on social media makes it real. Social media enables the transfer of reflexive knowledge of socio-ecological resources at a greater efficiency than ever before in history. Social media is a post-affordance that acts as a catalyst encouraging adolescents to expand and differentiate their repertoire of affordances. By definition, an ecological resource supports an individual’s continued, reciprocal relationship with the world. Social media, as an influential process in contemporary society, could be described as a socio-ecological post-affordance. Post-affordance attempts to capture the shift from an individual’s real-time, physically bounded, and observable interaction with environmental affordances to include the growing repertoire of spatially and temporarily disconnected affordances instantly available through online resources. Unlike learning from television, magazines, or friends about new ways to play – the warning ‘do not try this at home’ comes to mind – the post-affordance of social media allows individuals to contribute and engage in reciprocal determinism or interdependence. The global base of related interests among diverse and disconnected communities provides an opportunity for designers to help make cities more inclusive. As a post-affordance, social media has a transformative power for urban research to promote city play. The post-affordance approach to understanding lived experience with the place also suggests that if we want to understand how this social-ecosystem influences adolescent play; then, we need to look at the place from the lens of their lived experience. Accordingly, the remainder of the paper switches from the visible, ecological perception of the individual in relation to ecological affordance and focuses on interpreting the place of lived experience accessible through the post-affordances of social media.

Places of lived experience

The current study seeks to understand the place of adolescent play in cities as rendered meaningful through the countless examples of post-affordances found on social media, like YouTube, Instagram, and Vimeo. With a representative sample in the billions, big data from YouTube and social media is the next paradigmatic shift in challenging how civilization learns about its condition. The move is already having important impacts on the urban design and landscape architecture of the theatre of everyday life, eg. the Better Block (Tayebi Citation2013), DIY Urbanism (Douglas Citation2012), and the use of Kickstarter (Ward Citation2013) to crowd fund and crowd source better public space.

Social media is – referencing the theory of the production of space from Henri Lefebvre – representational. Play has strong ties to individual creativity, developing competencies, and building capacity to accept difference and support diversity. Representational space belongs to ‘inhabitants and users’ (Lefebvre Citation1991). Lefebvre writes further, ‘as a space of “subjects” rather than calculations, as a representational space, it has an origin, and that origin is childhood, with its hardships, its achievements, and its lacks’ (Lefebvre Citation1991). Representational space is a space of lived experience. It is a space to play, try on different roles, create identities, make mistakes, and build memories. Representational space is filled with the symbolic actions of individuals and individual experience that may be in-line, playful, or in conflict with functional or instrumental space. Unlike instrumental places that represent the ideologies of a society, representational space is the symbolic space of subjective experience (Lefebvre Citation1991). An analysis of the space produced by adolescents in cities would support the inquiry into the contemporary social discourse on design to their play behavior.

Towards interpretive inquiry of big data

While the definition of big data continue to be diverse and debated (Chen et al. Citation2014), big data is best described as the aggregation and analysis of ‘data trails left from our digital footprints (Chandler Citation2015, p. 837).’ The literature delineates that it is not so much the volume or quantity of data as it is the use of algorithms to search, aggregate, and analyze (scrape) multiple datasets of information in a manner beyond its original intent. As Boyd and Crawford (Citation2012, 663) note, ‘big data is less about data that is big than it is about capacity to search, aggregate, and cross-reference large data sets.’ For this paper, the interpretation of big data is not limited to data mining, data science, volume, velocity, or variability, because such references to ‘big data’ continue to echo the ecosystem determinism of ‘big science’ (Aronova et al. Citation2010). Instead, big data represents a radical shift in how we approach to research on human networks (Boyd and Crawford Citation2012). For the sake of simplicity, I will follow the interpretation of big data provided by Chandler (Citation2015) for the duration of this paper:

Big Data transforms our everyday reality and our immediate relation to the things around us. This ‘datification’ of everyday life is at the heart of Big Data: a way of accessing reality through bringing interactions and relationships to the surface and making them visible, readable, and thereby governable, rather than seeking to understand hidden laws of causality. Big Data is generally understood to generate a different type of ‘knowledge’: more akin to the translation or interpretation of signs rather than that of understanding chains of causation (836).

YouTube, for example, is a nearly boundless record of human experience. Statistics from YouTube’s product page, identify that it has 1 billion users, hundreds of millions of viewing hours daily generate billions of views, represents 75 countries and 61 languages, and 300 h of video are uploaded every minute: source, youtube.com/yt/press/statistics.html. While the subject in YouTube tends to be a performance, what is incredibly meaningful for urban research is the background context affording the performance.

Research using social media as a form of data needs to recognize that the representations of play posted online were selected, edited, and staged by individuals sharing some kind of performance. The framed moment is useful for its symbolic content, not its matter-of-factness, for the role place plays in adolescent behavior. After discussing the play, urban space, and how videos were collected and coded, the paper will move on to discuss the relevance of the symbolic content to urban research to support play in cities.

Similar to Stevens (Citation2006), the goal is to understand how ‘urban form might frame experiences which are unexpected, unfamiliar, spontaneous, and risky’ by examining ‘non-instrumental, social behavior, or play, in urban public spaces. (805)’ While Stevens employs a more traditional method, unobtrusive observation, I’m suggesting that the momentary fragments of experience recorded and posted online occupy another window into representational space. Adolescents often interpret public space for play in a non-instrumental manner, and examples of play-places posted online can be interpreted as representative of individual experience with the place. The online video, sometimes a well-edited document and other times a raw fragment of a moment in time, is only a representation of a moment of experience. The publicly available, the recorded moment becomes data once imagined by the researcher as something useful for interpretation. As Gitelman and Jackson (Citation2013) writes:

Events produce and are produced by a sense of history, while data produce and are produced by the operations of knowledge production more broadly. Every discipline […] has its own norms and standards for the imagination of data, just as every field has its accepted methodologies and its evolved structures of practice (p. 9).

Knowledge production in landscape architecture and urban design has long relied on data from the observation of human behavior to improve design (Jacobs Citation1961, Whyte Citation1980, Gehl Citation2011). The approach has affected policy aimed to overcome barriers due to physical ability, for example, the Americans with Disabilities Act, improve plaza design, protect street life, and has even found that patients heal faster with views of natural spaces. Following Gitelman, the representational space found on social media could be imagined as data to inform the design and improve the human condition in cities. Research along these lines would begin by pulling data out of the ‘undifferentiated blur’ and interpret individual moments in a matter relevant to the discipline (Gitelman and Jackson Citation2013).

The method of inquiry considers the representations of lived experience found in social media as symbolic actions from which the researcher can inscribe data relevant to place. For this paper, I am defining symbolic action as the represented moments of human action for play found online; and, that symbolic actions could be interpreted as data inscribing new information about the place. The approach is similar to what anthropologist Clifford Geertz described as ethnography. ‘The ethnographer “inscribes” social discourse, he writes it down.’ Geertz (Citation1973) continues, ‘In so doing, he turns it from a passing event, which exists only in its moment of occurrence, into an account, which exists in its inscriptions and can be reconsulted’ (19). Urban research could access online videos to jot down moments of people’s engagement with place, pulling it from the undifferentiated blur of social media.

Individual behaviors represented through online media inscribe contemporary social discourse. Geertz describes thick description as the process of extracting, interpreting, and analyzing the inscribed moments in a contextually appropriate manner. Human behavior is interpreted as a symbolic action. Following Gilbert Ryle, whom Geertz cited as coining thick description, analysis – the ‘sorting of the structures of signification’ – takes place through codes. Geertz, similar to Ryle, emphasized that codes in the thick description are not ciphers. The need to consider social context is what differentiates a wink from a twitch, an insult, or an invitation – ‘winks upon winks upon winks.’ Codes in thick description aim to interpret the affordances of place and successfully import the relevant context from the inscribed moments. The methodological approach for design is to analyze what new insights into the design of public space can be accessed from the endless stream of captured moments. The form of inquiry would seek to address questions like:

what can urban research learn from the post-affordances available through social media?

how do representations of play in public space challenge normative perceptions of urban form?

what does the analysis of our own inscriptions tell us about the effectiveness of urban design to afford positive experience in public space?

The primary form of data for understanding the affordances of a place is publicly posted online videos found on Instagram, YouTube, and Vimeo. Other forms of data are possible, like Twitter, Facebook, Pinterest, and others changing every day, but the focus here is on video. Online videos and CCTV cameras are becoming more accessible for researchers, event planners, and police thanks to search algorithms that characterize crowd movement and demographic characteristics (Nam Citation2014, Wang et al. Citation2014). Accordingly, thickly coding video remains a time-consuming method to study the human condition. The human observer still needs to sit, watch, listen, and inscribe observations of human behavior as they relate to a mode of inquiry, i.e. unlike machine learning, the algorithm is not the end point of inquiry. The researcher still needs to learn, so the first challenge of searching and viewing online content is discovering the various, incomprehensible signifiers used by diverse individuals to render their content meaningful to a niche group of people. The second challenge is viewing and filtering the meaningful videos from the blur. Billions of examples of human experience, filtered through an initial search, still need to be watched and verified for relevance: representations of adolescents play in public space. The third is coding the videos in such a way that they retain sufficient context to meaningfully inscribe affordances. Coding all of the videos as a wink, wink, or wink ignores the contextual information that places the moment within a larger social discourse.

Limitations

People perform and produce multiple forms of play in a wide range of public places across cities. While this point might not be surprising, and multiple studies on urban play exist, no study has attempted to explore the representations of play on the urban stage using big data – maybe for good reason. The author’s previous study focused on a single type of play, skateboarding, in known locations in a single city. Geographic, activity, and age limitations focused videos into a manageable quantity to search, verify, and inscribe. The current research approach has expanded to multiple representations of play in five cities: Denver, St. Louis, Minneapolis/St. Paul, Des Moines, and New Orleans. Representations of play have been expanded to include: deep play like skateboarding, parkour, and time-consuming installations like DIY parks, graffiti or street art, and environmental art; social play like flash mobs, zombie crawls, parades, dancing, and singing; and, other spontaneous forms of play like splashing in a fountain. While machine learning and AI algorithms are an evolving field for video-based big data research, currently the breadth of play limits the depth to which any single place can be analyzed.

Collecting and coding data

Analysis proceeded in two phases: first, locate and identify relevant examples of play in the representational space of YouTube; second, interpret collected data and develop new, salient typologies that can be used to frame massive amounts of information into manageable categories useful for landscape architecture research. I describe the twofold process of analysis below.

Search terms for adolescent play were developed through an inductive, or grounded theory approach (Babbie Citation2007), and placed into a matrix to identify the relevance of the place-based search terms in each city. The search uses a hit and miss approach, where terms are iterated until relevant social media is found. Following Babbie’s suggestion, once terms connect to content, then snowball sampling through the poster’s feeds, user comments, and links to other posts creates a more robust and socially specific set of search terms. After the bulk of data is collected from social media, the time of posting becomes a more reliable filter of relevant and recent content. The matrix now comprises 476 possible combinations of search terms (eg. skateboarding and DIY) to access data from social media (See ). Through this process, over a two-year period, 998 relevant videos of people playing in public space have been collected (See ). These videos were initially screened by trained graduate and undergraduate research assistants at Iowa State. Student researchers used a spreadsheet in Excel to index usable videos and generated new metadata identifying the relevance of data to design inquiry.

Table 1. Videos and scenes by age and category.

Table 2. Matrix used to identify divergent categories of city play.

Table 3. Search terms used for city play.

Currently, we have 40 h of highly relevant content of individuals playing in public space. The primary subjects of the 998 videos include: 372 (37%) with adults, 514 (50%) with youth 9–18+, and 102 (10%) with children under 10 (). Following the robust coding scheme previously developed by the author (see Shirtcliff Citation2015b, Citation2016), the process of coding each scene of individual behavior, based upon an earlier study, would take approximately 427 h to code 1000 unique scenes. At over 6000 scenes, the researcher did not have the capacity to support this amount of time to coding behavior. Instead, we focused on extracting scenes of optional or ‘play’ behaviors as shown in the table. After a process of timeframe selection, pulling out the precise duration of play and excluding other content, usually focused on the indirectly related environmental context or illicit behaviors, we identified 6686 scenes of ‘City Play’ from the 998 videos.

Correspondingly, the prior analytic strategy (Shirtcliff Citation2015b, Citation2016) was modified to achieve meaningful data useful for an interpretive paper within a reasonable amount of time. At this point, the study shifted from focusing on the particulars of each scene of individual play behavior and towards saliently aggregating adolescent play behavior into divergent place-based categories (Marshall and Rossman Citation2006). As described in detail in the discussion and illustrated in the following matrix (), we found play divergence in normative or alternative play behaviors based on formal or alternative places into the three categories: formal places to play, spaces for play, or no place to play. The goal was to be able to efficiently and reliably place each scene in a salient category for further coding and analysis. Accordingly, we set out to find new categories that had internal convergence and external divergence – scenes in one category express similarities while being distinguishable from scenes in other categories.

After detailed discussions and corroboration of the variations and similarities in scenes as a lab – trained researchers including four undergraduate and four graduate students across two years –, we identified three divergent categories (see ): Play in place (n = 1357, m = 20%), space for play (n = 1280, m = 19%), no place to play (n = 2941, m = 44%). Once the categories were identified, as recommended by Haidet, 10% of the videos were the recoded and reliably identified among trained raters for saliency (Haidet et al. Citation2009). Kappa, a measure of internal agreement among coders with acceptable limits in controlled studies at .75, were used to identify internal consistency with play in place (K > .8), space for play (K > .84), and no place to play (K > .6), all demonstrating sufficient internal consistency (see ). No place likely rated lower due to the wide variety of place-based situations. The interpretation of the categories and relevance to urban design theory are discussed in the following section.

Interpreting play in place, space for play, and no place to play

The current study is a phenomenological investigation into the place of adolescent activity rendered visible through the lens of social media. Representations of their activity were used to uniquely differentiate and categorize place through social media. By interpreting the categories through the following influential theorists on place and space, I aim to make the findings relevant to the context of urban design and research. Walter Benjamin, Michel de Certeau, and Gaston Bachelard, each interpreted representations of space to understand socio-cultural and socio-economic forces informing place. Each of these authors’ works exemplifies the challenge of how to make individual affordances of place in everyday life empirically meaningful through the process of inscribing. Walter Benjamin’s investigation of the poetry of Charles Baudelaire presents a window into a rarely discussed story of Paris (occasionally, the bright side) at the height of industrialization. Benjamin’s rigorous analysis of Baudelaire’s poetry demonstrates the tremendous import researchers can learn from the effort of others who struggle to represent daily life through poetry, art, or other media (Benjamin Citation1997). Michel de Certeau and Gaston Bachelard both discuss the meaning of space that lies within their own individual experience. Certeau (Citation1984, p.123) uses metaphor to reveal how the story of space is a ‘culturally creative act.’ Bachelard, along with the same lines, works through poetry to inscribe a perception of space that we would not otherwise have access.

. Screen captures of Adolescent ‘Play in Place’ categories collected from online sources. Note for figures: All videos were sourced from public domains YouTube.com or Vimeo.com. Institutional human subjects review stipulated data would be deidentified and no identifying information of individual identities, including author pseudonyms, would be published as a result of this research.

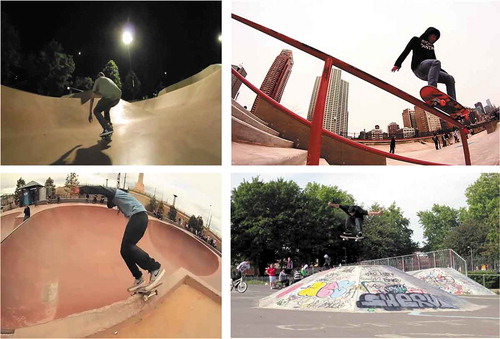

Figures 1–4. Risky play takes practice and designated play places provide an instrumental value, permitting repetition. Screen captures of Adolescent ‘Play in Place’ categories collected from online sources. Note for figures: all videos were sourced from public domains YouTube.com or Vimeo.com. Institutional human subjects review stipulated data would be deidentified and no identifying information of individual identities, including author pseudonyms, would be published as a result of this research.

Play in place

“The modalities of pedestrian enunciation which a plane representation on a map brings out could be analyzed. They include the kinds of relationship this enunciation entertains with particular paths by according them a truth value, an epistemological value, or finally an ethical or legal value. Walking affirms, suspects, tries out, transgresses, respects, etc. the trajectories it “speaks.” (Certeau Citation1984)

de Certeau’s metaphor of walking as a form of speech presents the initial category for categorizing videos. Walking becomes useful for analysis following de Certeau’s triple enunciative function of the present, discreet and the phatis. The phatis directs our attention to the implicit rules that frame a common, often overlooked human activity, walking, within a social context of behavior in formally designed space. His focus is on the thickening of an instrumental space. de Certeau referenced the difference here between the place with ‘proper’ rules – ‘the elements taken into consideration are beside one another, each situated in its own “proper” and distinct location’ – and space – ‘vectors of direction, velocities, and time variables’ (Certeau Citation1984). He goes on to suggest that ‘space is practiced place’ and that the street is transformed into a space by walkers ibid. A thin interpretation of a sidewalk would be mapping it, whereas a thicker interpretation would be how it is used, tried out, and contested by different ideas of appropriation. Taken literally, walking is one of the most common human activities supported by urban design. An increasing amount of research and policies directed at making cities more walkable, e.g. complete streets due to an obesity epidemic, has made walking a frontline issue in the United States (Eyler et al. Citation2003, Forsyth et al. Citation2008, Hoyt et al. Citation2014, King and Clarke Citation2015). It seems relatively straightforward that cities should afford walking. However, as the above papers indicate, too often urban and suburban design fails to incorporate safe, accessible, and desirable places for walking. U.S. cities have become so walking intolerant that laws prevent people from walking in streets (jay-walking). Our collective memory should recall that the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri was initiated by the law enforcement of jay-walking. One of the most common human activities has a formally designed place with implicit rules representative of our social context and social problems. The notion that walking has escaped the design process and become restricted to the occasionally accessible and adequate affordance is similar to what has happened to play.

Play and the grounds for play became flags waved during the reform movement to call playgrounds to the attention of politicians and city planners in the 1920s and 1930s. However, neither the city planners nor the reformers were actually interested in play (Gaster Citation1992, Howell Citation2008a). The reformer perspective argued that organized playgrounds provide ‘political socialization’ and places to ‘supervise and control’ children (Howell Citation2008b); their implicit goal was to make good citizens out of children who would someday become adults. ‘Play’ became an institutionalized act used to further extend the hand of ‘proper society’ over people at an early and influential age. Playgrounds institutionalized age-segregation, specialization of function, and supervised play (Lynch Citation1981). Following Gaster, Howell, Lynch and others (Gilliland et al. Citation2006, Holt et al. Citation2009, Khan and Kotharkar Citation2012, Loxham Citation2013, Kirshner and Jefferson Citation2015, Villanueva et al. Citation2016), schools and schoolyards, not playgrounds, are now responsible for most opportunities to play. Little surprise that only twenty percent of the representations of city play found in the YouTube videos (1,357) evidence examples of people playing in place – in a place intentionally set aside for play. Playgrounds like skate parks in the suburban United States, evidence age and gender segregation, specialization of a space for a single function, and a form of peer-to-peer supervision that often results in territorialization (Woolley et al. Citation2011). The videos produced at places where people are found playing in place tend to focus on what Vivoni (Citation2009) found: big air. Each scene is a clipped fragment of a moment, emphasizing the success of an endless stream of similar, successfully landed maneuvers. The place is instrumental by permitting such repetition. Risky play takes practice. The place, a skate park, evidences the fulfillment of its highly specific function through the streaming videos of various techniques and maneuvers. The examination of adolescent behavior as instrumental with place reveals specific qualities about materials and physical design to improve the specialization of the place to support the activity. ‘Play in place’ approaches to design tend to be specialized, instrumental, overtly aestheticized, and highly-segregated, i.e. play that here not there. In reference to de Certeau, what happens when we look beyond use and age segregation, beyond formal and informal rules of designated spaces, and observe the city through the act of playing? . Screen captures of Adolescent ‘Space for Play’ categories collected from online sources.

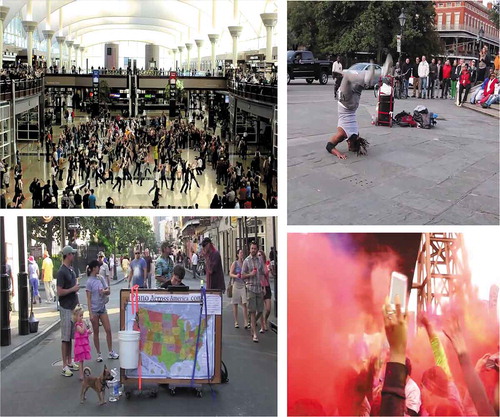

Figures 5–8. Flash mobs, break-dancing, a mobile piano, and countless phones recording a fun run demonstrate how crowds and performance creates an intrinsic value to space. Screen captures of adolescent ‘space for play’ categories were collected from online sources.

Space for play

The transformation of a street for walkers, and not cars or buses, introduces the second distinct category of social media on the play. Space for play captures the intrinsic value of urban life at a moment where an event transforms the city beyond its instrumental value. However, the permitted deviance from social norms does not abandon norms altogether, potentially explaining why space for play represents only 19% of the collected scenes of play in cities. Spaces for play temporarily transform the purposeful place to support non-purposeful activities and bring a richer meaning to life in cities. Such event-spaces have an intrinsic value due to their unique timing and location. The analysis of online videos reveals two similar types of symbolic actions relevant to the affordances of space for play: 1. play on space, such as temporary, environmental art like the Kurt Perschke’s Big Red Ball; 2. space for play, such as a Mardi Gras parade, zombie crawl, or red dress run. Videos in this category tend to be longer, lack a specific focus, and generate too much content to code separate individual behaviors from the movement and flow of the crowd. The background, on the other hand, remains a constant above the swarming, unimpenetrable mass of human life, and provides more information on urban context than in the short, clipped scenes in play in place. The second category emerges from YouTube as the crowd ‘sets aside’ urban space for play.

Space for play temporarily reimagines the city beyond instrumental value. Such play has an intrinsic value that elicits a critical revision of the social discourse on contemporary cities. The value of social media to capture and produce a representational space of symbolic actions is similar to Benjamin’s reading of Nineteenth-Century Paris represented by Baudelaire. ‘What speaks against this [whether or not Baudelaire’s poetry is still relevant] is precisely that when we read Baudelaire we are given a course of historical lessons.a critical reading of Baudelaire and a critical revision of this course of lessons are one and the same thing’ (104). Benjamin focused on the influential role that the arcades of Paris had on the poet, Baudelaire. Arcades were spaces set aside from ‘the sight of carriages that did not recognize pedestrians as rivals’ for people to ‘leisurely stroll’ and shop (53).

What Benjamin found in Baudelaire’s poetry was the intentional self-commodification of the poet as the flaneur – who ‘demanded elbow room and was unwilling to forego the life of a gentleman of leisure’ (54). Through the poet’s immersion in the crowd and representation of love at last sight, Benjamin critically revised a moment in history where cities changed the space of public life. The availability of elbow room for alternative activities was an indirect result of the design of new places, away from the street, for shopping. Through YouTube videos, we find multiple examples from flash mobs to zombie crawls to videos documenting when Banksy comes to town and leaves behind the satirical, graffiti sketches. In such cases, formal public places are temporarily reinterpreted in an alternative manner that creates a unique play on space. The crowd is an anticipated result. These ‘spaces for play’ occur when streets are transformed to support parades, or when neutral grounds (boulevards) become semi-privatized as ‘places’ for a weekend of festivals, and when port-o-potties generally show up for the duration of an event. The transformation of the street into a park permits behaviors typical of a park and less so of a street; a car driving down such a street would become the alternative behavior and has been known to provoke hostility from the crowd.

The production of representational space for play is accessible through YouTube as the lens of anonymous producer records the symbolic actions of contemporary public discourse in cities. The availability of multiple, highly visible and accessible productions of urban space to support play is a click away. Benjamin writes that Baudelaire captured the social aura crystalized in the crowd. Benjamin’s historical materialist approach aimed to discover still-reigning political forces through the work of the poet. Baudelaire reproduced the crowded streets of Paris by capturing moments otherwise lost to experience. Similarly, the category of ‘space for play’ interprets the representations of urban space on YouTube to reveal unique insights about positive social experiences found in events, crowds, protests, and other cultural gatherings generating an alternative discourse on cities. In a post-affordance context, social media plays a lesser role in the transformation of place to support play than the crowd’s investment in the intrinsic experience of the moment.

. Screen captures of Adolescent ‘Space for Play’ categories collected from online sources.

No place to play

Where the first two categories are placed in planned or designed environments, the third category, no place to play, focuses on re-imagining informal places for a kind of play otherwise inaccessible. Through 2,941 examples, 44% of social media content, an associative process emerges that permits the city to become re-imagined for the urban designer. The apex of this representation is found in recent discussions on Do-It-Yourself (DIY) urbanism (Iveson Citation2013). Without permits, permission, or financial support, parks are appearing in cities in place of unused, dilapidated urban spaces. Such DIY parks support environmental art, spontaneous play, skateboarding and biking, guerilla gardening, off-leash dog walking, street art, drinking and other illicit activities, and simply hanging-out with friends without the surveillance, expectations, prohibitions, and policies typical of urban, public space. No place to play accounts for how such places are temporarily or permanently transformed to support a new, previously unimagined affordance.

A central figure in architectural theory, Bachelard proposed a research method similar to psychoanalysis but with a focus on dwelling – ‘study of the sites of our intimate lives’ (8). Bachelard uses topoanalysis to access the intimate spaces of subjective experience, in a manner similar to Benjamin, through the imagery provided in works of poetry. Pint (Citation2013) suggests that, despite major advances in psychology and philosophy, Bachelard’s approach remains useful for the contemporary study of intimate space or dwelling (114). Pint recommends that a ‘significant modification to Bachelard’s “topoanalysis” would be the extension of the media in which to look for alternative images’ (117). Such alternative images, he contends, would similarly ‘produce a topography of imaginary dwelling in which different, unknown sensations or insights can be explored’ (ibid.). The category of no place to play is filled with such moments. The act of reimagining is highly reflexive and involves an active imagination to transform place for play.

In The Poetics of Space, Bachelard uses a similar approach to de Certeau and looks towards works of poetry as a means of accessing the intimate meaning of spatial experience. Bachelard’s writing focuses on how ‘images’ like house or city are burned into our mind with meanings whose origin we are often unaware. Bachelard begins from a point similar to the current discussion:

“how can an image, at times very unusual, appear to be a concentration of the entire psyche? How – with no preparation – can this singular, short-lived event constituted by the appearance of an unusual poetic image, react on other minds and in other hearts, despite all the barriers of common sense, all the disciplined schools of thought…?” (Bachelard and Jolas Citation1994).

Bachelard employs poetry in The Poetics of Space as a means to approach the image of the house as the specific entity for his phenomenological investigation into the meaning of spatial experience (Bachelard and Jolas Citation1994). The image of the house, following his investigation, defies definition and provides structural support for memory to be fixed to a space (Citation1994). Bachelard’s text is foundational in its use of the phenomenological method to access spatial experience. His text leaves us with an important point to consider regarding the play behavior of youth in cities. The image of the city available to youth is accessible through the observation of their representations. Through social media and in physical environments, adolescents are actively creating an image of the city meaningful to their affordances of space.

The category of no place to play broadly categorizes representations of play that are neither a result of the instrumental design of the place nor the intrinsic moment of activity. Videos found and categorized as no place to play possess a transformative quality with an intimate feel. We found that these videos felt like an exclusive, backstage pass to places packed with unique, symbolic actions of an uninhibited, social discourse on the play. The alternative, symbolic actions present a unique, transformative image of the city: a highly individualized, intimate fragment preserved in the public space of social media. The category is similar to Daniel Campo’s discussion in The Accidental Playground. In a detailed place-ethnography, Campo describes the evolution of unique social and cultural conditions found in a ‘scrap of land, this booger of land that stands right on the fringe’ slowly being ‘eaten by water, being eaten on the other side by the ever increasing cleaning up of the neighborhood’ (Citation2013). People entering the accidental playground access an intimate-public-private space, with laws and rules loosened enough to permit more freedom than could be found elsewhere. Yet, these places are temporary and the users lack the rights or the authority to protect the place for themselves. An increasingly dense urban population is likely to also look for such intimate, almost public places to play as formal public places become overrun with normalizing expectations, zombie places (Lashua Citation2015), and exclusionary tactics. The cleaning up of the city is ‘great but it’s less interesting […] as an unpoliced place, where you feel kind of free, even though it’s dirty and not safe’ (Campo Citation2013). Such examples of play found on YouTube might be no place to play but they offer a window into urban life unavailable and, maybe more importantly, unafforded in typical city parks and public spaces. In reference back to Bachelard, the intimacy of no place to play includes an inherent separation of normative expectations and rules.

Conclusion

Post-affordances of urban play collected from the representational space of online video were saliently categorized as: places to play, spaces for play, and no place to play. Places to play are formal, designed environments, like playgrounds, parks, and skate parks, where instrumental and non-instrumental, spontaneous activity is anticipated and accepted to some culturally and legally acceptable limit. Spaces for play are the permitted use of places typically set aside for commerce and commuting, like streets, neutral grounds, and parking lots. A permit acknowledges that an event or performance, such as a parade, can transform the space into a place to play for a permitted period of time. No place to play is the unpermitted and unpermissioned appropriation of public or abandoned private space as a place to support intrinsically motivated, unplanned, alternative human activity.

Videos on play in formal places internally converge on normative behaviors, the sophistication that come with practice, and short, performance based scenes exemplifying individual success. The videos are divergent from videos that focus on the scene created by a crowd or the activation of informal places. Space for play videos tend to maintain internal convergence through a longer, unedited length, often without the focus on a single individual, and occur during a planned event. Spaces for play are divergent from places to play in that the play is intrinsically motivated in a place with a different formal instrumental value. The appropriation of formal space is acceptable to a group or crowd and distinct from no place to play because the place is clearly formally designed, just maybe not what is occurring at the moment. No place to play videos are internally convergent through the intimate insights they offer into informal semi-public-private places, scenes tend to be longer than play in place but shorter and more focused than space for play, and are often loaded with unique social and cultural contexts not found informally designed environments. A future, deeper analysis of human behavior across the three categories would reveal further insights into the level of spontaneity, predictability, and play afforded in each setting.

The three categories presented here are not novel to this paper and have a substantial supporting literature in landscape architecture and allied urban design fields. Playgrounds, festivals, parks, skateparks, streets, sidewalks, plazas, and even DIY parks all have supportive (and unsupportive for adolescents) literature in the design fields. The goal here was to assess the post-affordances of urban place from the shared representations of lived experience in social media. Given the ‘undifferentiated blur’ of social media, it was necessary to create a new framework for how the videos would provide insight for urban research. While it will and must be argued that research in the representational space of social media is no replacement for research-in-place, I suggest that dismissing the approach fails to acknowledge that people are more likely to learn about the affordances urban space and place through locally disconnected, global communities. Whether the play occurs in formally designed spaces, through formally programmed events in spaces designed for other uses, or through the informal reimagining of intimate, transformative places for alternative activities, new insights are afforded to people of similar interests from unknown individuals across the globe. Foremost, this research demonstrates that social media is an integral part of the socioecology of adolescents. Post-affordances present new opportunities and new challenges for urban design and urban research on children and youth; for instance, what happens when the messy life of everyday individuals becomes the primary means of imagining the city? Research along these lines has only just begun and presents a fruitful place for urban research to improve the capacity for cities to welcome an increasingly diverse population and support adolescent play.

Play in place, space for play, and no place to play challenges the status quo to consider the occasional mode of adolescents’ playing the city. Whether a formal park, a permitted festival, or a hidden retreat, design and policy should adapt to make room in cities to afford the transformative value of play. The finding that most of the coded scenes and videos were from places that were never designed or permitted to support the activity supports two competing theories: 1. Design and policy continue to fail to meet the needs of teens; 2. Adventurous teens will follow the post-affordance model to identify and create new opportunities to play, regardless of what has formally been provided or permitted. Both theories have positive implications. Cities should create, support, and follow the lead of adolescents to build more inclusive and safer places to play.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by Iowa State University Center for Excellence in Arts and Humanities & Fieldstead and Co. Endowment for Community Enhancement Fund.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Benjamin Shirtcliff

Dr Benjamin Shirtcliff is a scholar on urban ecological theory, built environments, and adolescent play, my work addresses inequalities between adolescents and health outcomes related to design, policies, and practices. I contend that opportunities to engage adolescents in public space will have long-term societal benefits. I have been actively researching, designing, and engaging adolescent built environments for two decades. My award-winning design and research addresses opportunities for cities to support play in response to rising obesity rates, isolation, and condemning perceptions of risk.

References

- Aronova, E., Baker, K.S., and Oreskes, N., 2010. Big science and big data in biology: from the international geophysical year through the international biological program to the Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) network, 1957–present. Historical studies in the natural sciences, 40, 183–224. doi:10.1525/hsns.2010.40.2.183

- Babbie, E.R., 2007. The practice of social research. 11th. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.

- Bachelard, G. and Jolas, M., 1994. The poetics of space. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Benjamin, W., 1997. Charles Baudelaire: a lyric poet in the era of high capitalism. London,: Verso.

- Benjamin, W. and Arendt, H., 1986. Illuminations. New York: Schocken Books.

- Bjorklund, D.F., 1997. The role of immaturity in human development. Psychological bulletin, 122, 153–169.

- Boyd, D. and Crawford, K., 2012. Critical questions for big data: provocations for a cultural, technological, and scholarly phenomenon. Information communication and society, 15, 662–679. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2012.678878

- Brofenbrenner, E.A., 2000. Developmental science in the 21st century: emerging questions, theoretical models, research designs and empirical findings. Social development theory, 9, 11.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. and Evans, G.W., 2000. Developmental science in the 21 [sup st] century: emerging questions, theoretical models, research designs and empirical findings. Social development theory, 9, 115–125. doi:10.1111/1467-9507.00114

- Campo, D., 2013. The accidental playground: Brooklyn waterfront narratives of the undesigned and unplanned. New York, NY: Fordham University Press.

- Certeau, M.D., 1984. The practice of everyday life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Chandler, D., 2015. A world without causation: big data and the coming of age of posthumanism. Millennium: journal of international studies, 43, 833–851. doi:10.1177/0305829815576817

- Chen, M., Mao, S., and Liu, Y., 2014. Big data: a survey. Mobile Networks and Applications, 19, 171–209. doi:10.1007/s11036-013-0489-0

- Douglas, G., 2012. Do-it-yourself urban design in the help-yourself city. Architect-Northbrook, 43.

- Ellis, B.J., et al., 2012. The evolutionary basis of risky adolescent behavior: implications for science, policy, and practice. Developmental psychology, 48, 598–623. doi:10.1037/a0026220

- Eyler, A.A., et al., 2003. The epidemiology of walking for physical activity in the United States. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 35, 1529–1536. doi:10.1249/01.MSS.0000084622.39122.0C

- Forsyth, A., et al., 2008. Design and destinations: factors influencing walking and total physical activity. Urban studies, 45, 1973–1996. doi:10.1177/0042098008093386

- Gaster, S., 1992. Historical changes in children’s access to U.S. cities: a critical review. Children, youth and environments, 9, 34–55.

- Geertz, C., 1973. The interpretation of cultures: selected essays. New York: Basic Books.

- Gehl, J., 2011. Life between buildings: using public space. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Gibson, E.J. and Pick, A.D., 2000. An ecological approach to perceptual learning and development. USA: Oxford University Press.

- Gibson, J.J., 1979. The ecological approach to visual perception. Rev. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Gilliland, J., et al., 2006. Environmental equity is child’s play: mapping public provision of recreation opportunities in urban neighbourhoods. Vulnerable children and youth studies, 1, 256–268. doi:10.1080/17450120600914522

- Gitelman, L. and Jackson, V., 2013. “Raw data” is an oxymoron introduction. “Raw data” is an oxymoron Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1–14.

- Guyer, A.E., et al., 2014. Will they like me? Adolescents’ emotional responses to peer evaluation. International journal of behavioral development, 38, 155–163. doi:10.1177/0165025413515627

- Haidet, K.K., et al., 2009. Methods to improve reliability of video-recorded behavioral data. Research in nursing & health, 32, 465–474. doi:10.1002/nur.20334

- Harris, M., 1968. The rise of anthropological theory; a history of theories of culture. New York: Crowell.

- Heft, H., 1989. Affordances and the body - an intentional analysis of gibson ecological approach to visual-perception. Journal for the theory of social behaviour, 19, 1–30. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5914.1989.tb00133.x

- Holt, N.L., et al., 2009. Neighborhood physical activity opportunities for inner-city children and youth. Health and place, 15, 1022–1028. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.04.002

- Howell, O., 2008a. Play pays. Journal of urban history, 34, 961–994. doi:10.1177/0096144208319648

- Howell, O., 2008b. Play pays: urban land politics and playgrounds in the United States, 1900-1930. Journal of urban history, 34, 961–994. doi:10.1177/0096144208319648

- Hoyt, L.T., et al., 2014. Neighborhood influences on girls’ obesity risk across the transition to adolescence. Pediatrics, 134, 942–949. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-1286

- Iveson, K., 2013. Cities within the city: do-it-yourself urbanism and the right to the city. International journal of urban and regional research, 37, 941–956. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12053

- Jacobs, J., 1961. The death and life of great American cities. NY: Random House.

- Khan, S. and Kotharkar, R., 2012. Performance evaluation of school environs: evolving an appropriate methodology building. Ace-Bs 2012 Bangkok, 50, 479–491.

- King, K.E. and Clarke, P.J., 2015. A disadvantaged advantage in walkability: findings from socioeconomic and geographical analysis of national built environment data in the United States. American journal of epidemiology, 181, 17–25. doi:10.1093/aje/kwu310

- Kirshner, B. and Jefferson, A., 2015. Participatory democracy and struggling schools: making space for youth in school turnarounds. Teachers college record, 117, n6.

- Lashua, B.D., 2015. Zombie places? Pop up leisure and re-animated urban landscapes. In: S. Gammon and S. Elkington, ed. Landscapes of leisure. Springer, 55–70.

- Lefebvre, H., 1991. The production of space. Oxford, UK; Cambridge, Mass., USA: Blackwell.

- Loxham, A., 2013. The uses and abuses of public space: urban governance, social ordering and resistance, Avenham park, preston, c. 1850-1901. Journal of historical sociology, 26, 552–575. doi:10.1111/johs.2013.26.issue-4

- Lynch, K., 1981. A theory of good city form. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

- Marshall, C. and Rossman, G.B., 2006. Designing qualitative research. 4th. Thousands Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications.

- Nam, Y., 2014. Crowd flux analysis and abnormal event detection in unstructured and structured scenes. Multimedia tools and applications, 72, 3001–3029. doi:10.1007/s11042-013-1593-7

- Nassauer, J.I., 2012. Landscape as medium and method for synthesis in urban ecological design. Landscape and urban planning, 106, 221–229. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.03.014

- Patnode, C.D., et al., 2010. The relative influence of demographic, individual, social, and environmental factors on physical activity among boys and girls. International journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity, 7. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-7-79

- Pint, K., 2013. Bachelard’s house revisited: toward a new poetics of space. Interiors, 4, 109–123.

- Sarkar, S., 2012. Environmental philosophy from theory to practice. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Shirtcliff, B., 2015a. Sk8ting the Sinking city. Interdisciplinary environmental review, 16, 97–122. doi:10.1504/IER.2015.071016

- Shirtcliff, B., 2015b. Surfing the youtube. In: T. Keane, ed. Incite change / change insight. Manhattan, KS: Kansas State University, 53–64.

- Shirtcliff, B., 2016. Big data in the big easy. Journal of landscape, 34, 49–64.

- Stevens, Q., 2006. The shape of urban experience: a reevaluation of Lynch’s five elements. Environment and planning B: planning and design, 33, 803–823. doi:10.1068/b32043

- Tayebi, A., 2013. Planning activism: using social media to claim marginalized citizens’ right to the city. Cities (London, England), 32, 88–93. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2013.03.011

- Villanueva, K., et al., 2016. Can the neighborhood built environment make a difference in children’s development? building the research agenda to create evidence for place-based children’s policy. Academic pediatrics, 16, 10–19. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2015.09.006

- Vivoni, F., 2009. Spots of spatial desire Skateparks, Skateplazas, and urban politics. Journal of sport and social issues, 33, 130–149. doi:10.1177/0193723509332580

- Voorhees, C., et al., 2011. Neighborhood environment, self-efficacy, and physical activity in urban adolescents. American journal of health behavior, 35, 16.

- Wang, X., et al., 2014. An abnormal crowd behavior detection algorithm based on fluid mechanics. (Report). Journal of computers, 9, 1144. doi:10.4304/jcp.9.5.1144-1149

- Ward, M., 2013. Observations on contemporary urbanism and sustainability. Architecture Australia, 102 (5), 51–52. SEPT/ OCT.

- Whyte, W.H., 1980. The social life of small urban spaces. New York, NY: Project for Public Spaces.

- Woolley, H., Hazelwood, T., and Simkins, I., 2011. Don’t skate here: exclusion of skateboarders from urban civic spaces in three northern cities in England. Journal of urban design, 16, 471–487. doi:10.1080/13574809.2011.585867