ABSTRACT

This paper outlines the role of urban design in the relationship between public space and families with children. The quality of outside play in urban and suburban spaces is crucial for the physical, social and cognitive development of young children. By analysing three important daily living domains – street, green spaces and play spaces – through observations, surveys, workshops and interviews in the city of Eindhoven, The Netherlands, the paper discusses the increasing need for family- and child-directed consumption spaces in city areas. The data also reflect that though there are processes in place that are progressively contributing towards the inclusion of changing urban lifestyles, concerns on importance of outside play, public green spaces, and safety remain high. It is argued that the role of design along with child-friendly indicators and locally important factors need to be better strengthened when planning future family-friendly city spaces. Initiatives such as co-creative design of public space with children and parents, bottom-up neighbourhood design initiatives (e.g. child friendly routes) are some examples. This paper points out the wider significance of spatial transformation of the city’s needs to accommodate various demographics and requirements.

Introduction

Following the current trend of global urbanisation and the growing attraction of cities for families with children, urban environments are becoming principal contexts wherein new generations of children will grow and thrive. This rapid urbanisation has a number of effects including a growing trend where not only young urban professionals are choosing to move into city areas, but also families (Bowles et al. Citation2009, Boterman Citation2012, Karsten Citation2013). It is estimated by the UN that 60% of the world’s children will live in cities by the year 2025. What this is indicative of is that for millions of children the contours of their everyday life and experiences will be shaped by urban environments. Boterman and Karsten (Citation2015) have titled this ongoing urban transition as the march of city families worldwide.

Figure 1. Example of road closed for a play street on Roxwell Road, London. Source: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Figure 2. Workshop with school children in the neighbourhood of Bergen held in January 2017. Source: Sukanya Krishnamurthy.

Figure 3. An example of play space improvements by a participant to include options for winter. On the top left corner, the participant added ‘teenagers forbidden’. Source: Sukanya Krishnamurthy.

Figure 4. Workshop with parents in the neighbourhood of Bergen held in February 2017. Source: Sukanya Krishnamurthy.

Figure 5. Location and demographic information of the four neighbourhoods. Source: Sukanya Krishnamurthy.

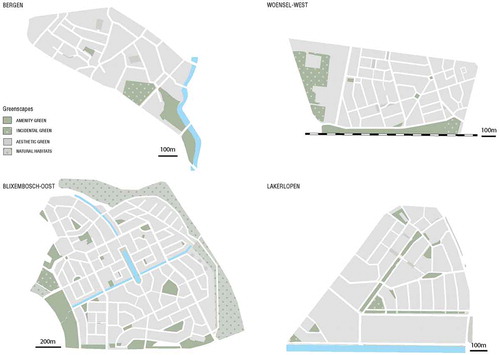

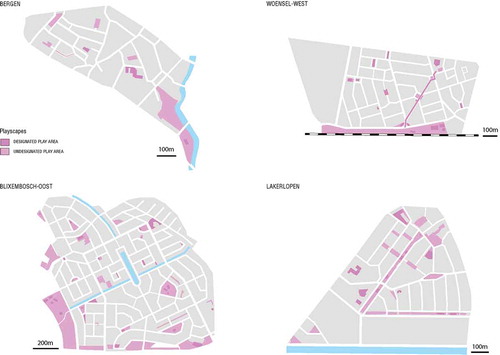

Figure 6. Designated and (observable) undesignated play spaces in the four neighbourhoods. Source: Sukanya Krishnamurthy.

Figure 7. Kindlint or child route in the neighbourhood of Woensel-West. Source: Sukanya Krishnamurthy.

This has renewed an interest on children’s lives in cities within the fields of social sciences, geography, planning and design (Matthews Citation2003, Karsten and Vliet Citation2006b, Wridt Citation2010), and welcomed different perspectives into the broad field of child-friendly urban environments. The impacts of these ongoing demographic shifts have initiated a discussion on urban planning discourses for their inclusiveness of family life in cities. For cities in the global north, families moving into or deciding to stay in inner city areas belong largely to a well-educated middle classes with enough resources to buy themselves an urban family home, and afford daily care of children (Karsten Citation2013). However, for families of lower income concerns related to housing prices and quality, services, living in transient or less than desirable neighbourhoods are pressing. See the following work for more examples, Authier and Lehman-Frisch (Citation2012), Butler (Citation2003), Karsten (Citation2013), Lilius (Citation2014). Not restricted to the global north, countries like India, (where 41.2 million children under the age of six live in urban spaces), Brazil, Peru, Turkey, etc. the challenge of growing up in cities brings concerns related to healthy and safe living conditions, recreational spaces, transport, urban poverty, etc.

Ongoing work on child-friendly cities explores and highlights the role of housing, transportation, community networks, play and green, and governance as important prerequisites for living in the city with children. With the expanding reach of children’s studies within the social sciences, urban analysis is essential to improve contextual understanding of children’s contemporary problems and needs in the city; particularly the designs of neighbourhoods and its influences on the geographies of everyday life for children (Carroll et al. Citation2015). Neighbourhoods where families settle for example, patterns of varied consumption, activities, and needs are more evident (Karsten Citation2013), reflecting an intensive consumption of urban spaces and also new practices of public parenting. Karsten (Citation2014) argues that this transformation goes with the production of a new city. Families as consumers claim their own urban environment through the development of a range of family-friendly facilities that can be summarised in three types: child-directed facilities, family-directed facilities, and child- and family-friendly public space. The rise in family friendly consumption spaces is in part initiated by the families involved, but also by governments, NGO’s and developers (examples include ©London Play Street, funded and supported by a variety of actors, ).

This paper positions learnings for urban planning and design within the creation of child-friendly environments through empirical work carried out in Eindhoven (NL). Structured as follows, the first section provides a brief review on planning for families with children. The second section outlines the objectives and methodology used to develop on existing typologies of indicators on three important daily living domains – street, green spaces and play spaces within four neighbourhoods of Eindhoven (NL). Following this, the context of planning for children in cities in the Netherlands is expanded on. The third section positions analyses of the three daily living domains from the case study – street, green spaces and play spaces – through observations, workshops and interviews. This section also discusses the increasing need for family and child directed consumption spaces in city areas. Data from the four neighbourhoods reflect that though there are processes in place that progressively contribute towards the inclusion of changing urban lifestyles, importance of outside play, the concerns on safety, variance of play options, etc. remain high. These concerns can be addressed through planning and design by employing small DIY solutions or larger interventions at the neighbourhoods and/or city level.

Children, planning and cities

The advantages of city living are many, services, social networks, cultural resources, shorter commutes between work and home, and it is this daily combination of tasks, preferences and budgets that motivates families to opt for an urban residential location (Hjorthol and Bjornskau Citation2005). What this implies for urban planning is (re)defining the nature of planning for families in urban areas. Karsten and Vliet (Citation2006a), for example, have identified the lack of understanding and recognition by planners on the importance of the local scale in the everyday lives of children and their parents, and plea for more family inclusive policies. With increasing obesity in children and young people (Niekerk Citation2012), themes such as importance of outside play, independent mobility, health, access to urban green etc. urban planning and design are gaining traction in the creation of child-friendly cities. These foci can be well served by developing an urban understanding of the interdependencies between different dimensions shaping child-friendly spaces and their impacts.

Creating child-friendly communities is central to building strong and vital neighbourhoods, cities and regions. Though planning for children is not new, from the mid-1940s, UNICEF has been advocating for the rights of children, creating initiatives such as ‘Mayor Defender of Children (1992), ‘Child Friendly Cities’ (1996), and developing frameworks for defining and developing a Child-Friendly City. To facilitate this, there is a growing body of research into the development of child-friendly communities. While much of this research focuses on addressing challenges within neighbourhoods for children, the research on the role of design and planning tools for improving practices related to child-friendly communities is still on the rise. Responding to this gap, various initiatives around the world are pushing the conversation on family friendly design strategies for inner cities. Some examples include Playful City USA, a platform started by the non-profit organisation KaBOOM! The platform acts as a program that is dedicated to bringing balanced and active play into the daily lives of all children, particularly those growing up in poverty in America (Kaboom Citation2017). The ‘Child and Youth Friendly City Strategy’ of Surrey (Canada) is an example of increased policy interest for inclusive design with families. Through community engagement, creation of community spaces, housing choice, youth programming and community partnerships, planning can be used to bring together various stakeholders (for a more comprehensive list please see, Krishnamurthy et al. (Citation2018).

Research approach

In order to develop insights into the role of planning and design for family-friendly cities, the paper analyses three important daily living domains – street, green spaces and play spaces – through observations, interviews and workshops in the city of Eindhoven (NL). By using environment-focused planning indicators connected to aspects of the built environment, quantitative and qualitative data were collected. Divided into two phases, the first phase consisted of semi-structured interviews with one of the parents from 204 families living the four neighbourhoods within the study scope. The four neighbourhoods were selected based on the number of children in the neighbourhood under the age of 12, proximity to the city centre, public transport provisions (cycling and bus), diversity of inhabitants (nationalities) and WOZ values (housing values).

The semi-structured interviews with the parents from the neighbourhoods covered, among other topics, housing preferences, play areas, green spaces daily activities, commute, advantages and disadvantages of living in urban environments, and mapping activities to point out preferred walking routes and locations they frequented with their children. The interviews were fully transcribed, and the results of the survey collated using Atlas.ti. The families and parents interviewed used various facilities in and around their neighbourhood (streets, play and green spaces, after-school and school programmes, etc.) on a daily basis in various ways, with positive and negative experiences. Results from the four neighbourhoods were compared with each other to identify the best possible neighbourhood to carry out the next phase for more qualitative research.

Phase two of the work was carried out in a gentrifying inner-city neighbourhood (Bergen) that is facing demographic changes and also had active participation from parents of the neighbourhood and schools in the area. We held two intensive workshops, one with school children at the neighbourhood primary school and one with the parents at the community centre, to address possible design measures for child-friendly cities. For the workshop with children (), we had 14 participants in three sessions progressively increasing in age: starting with four children in the age group of 7–8, eight children in the age group of 9–10, and two children in the age group of 11–12 (in all age groups there was an equal distribution of genders). The workshop included drawing sessions with the children to identify their challenges, places they considered important, where they play etc. ().

With the parents, we posed similar questions to position where they thought their children played and places that they thought needed attention around the neighbourhood (). The eight parents who joined us for an evening workshop were also invited to draw on a map to show their favourite routes in the neighbourhood (they went with their children). Though the parents of the children who participated in the workshop were invited to this event, only two parents joined the workshop. The workshops were independent of each other to enable active participation of the children without the presence of a parent and support the agency of children’s views. In parallel, five neighbourhood coordinators and policy-makers were interviewed to document current attempts at addressing changing needs and existing initiatives for families with children. Finally, we conducted desk-based studies of literature and policy documents on child-friendly initiatives in the city. By using the findings, elements for the construction of alternative urban discourses rooted in the daily experiences and challenges were identified. This paper is a step towards broadening the scope of urban planning and design discourses in the direction of family-friendly cities.

Empirical cases: four neighbourhoods in Eindhoven

Eindhoven over the last decade has been increasingly transforming into a city for young adults and families. In 2015, the PBL reported that in the year 2000, the city had an overrepresentation of people in the age groups between 20 and 40. The surrounding region in contrast showed an underrepresentation of this age group. Over the last decade, the disparity between the city and the region has become starker, while the city is attracting younger people the surrounding region is aging (Jong et al. Citation2016). The reasoning behind this shift according to PBL is the presence of various higher educational facilities and its growing innovative high-tech cluster.

Between 2005 and 2016, there is a slight decline within the representation of the population group between 20 and 40 years from 32.5% to 31.8% as a percentage of the total population (CBS Citation2017b). The same pattern of decline is also visible for children between 0 and 14 years from 15.9% to 14.9%. Compared to the other four large cities in the Netherlands Amsterdam, The Hague, Rotterdam and Utrecht where children between 0 and 14 make up, respectively 15.3%, 17.6%, 16.4% and 17.4% of the population (CBS Citation2017b), Eindhoven is a little different.

To analyse how the city is responding to the changes in population and need for better child-friendly planning, the research looked at four different neighbourhoods within the city: De Bergen, Blixembosch-Oost, Woensel-West and Lakerlopen ( gives an overview of the neighbourhoods). With relatively young populations, three of the four neighbourhoods were inner-city, and one was in the suburbs. The cases were selected based on three factors: First, the social economic status and cultural background of the neighbourhood. This was done on the basis of financial indicators such as the average home value (WOZ-waarde) and the average income per household. Ethnic composition of the population was also considered as literature shows that the use of public space and perception of safety varies across different ethnicities.

Second indicator was the location of the neighbourhood within the city. The four neighbourhoods reflected the diverse morphological patterns of Eindhoven. One neighbourhood in the city centre was chosen, one neighbourhood within the inner-city ring, one outside the city ring and one at the edge of the municipal boundary. Third indicator was the housing composition and urban morphological type.

The Netherlands: central role of planning for children

For a long period, families with children were considered to be a non-typical city household within the Netherlands. The rise and decline of play spaces in urban areas can be seen as a metaphor for the changing dynamics of families living in cities. Karsten (Citation2014) describes the historical dynamics of families in cities in Europe with a focus on the Netherlands. At the start of the nineteenth century, streets were the most important space of play for children at the time, but also not the most suitable. However, this changed dramatically with the growth of private car ownership around 1950s coinciding with the advent of mass suburbanisation. The city was seen as overcrowded, unsafe and unhygienic, and the years of suburbanisation of mostly middle-class families led to the almost ‘natural’ idea that families do not belong in the city (Ward Citation1977). The lack of affordable family housing is being one of the main deterrents of living in cities, and the image of space, quietness and green of suburbia influences many parents’ decision to leave the city for suburbia (Boterman Citation2012). Households who stayed within the city were often considered to have weak socioeconomic positions (Musterd and Ostendorf Citation2012).

Today, the county is experiencing a modest countermovement through mostly highly educated professionals who are increasingly choosing to remain in the city after the birth of their children. The city acts as a magnet for young people, especially when they pursue higher education, progressively finding their first job, housing, and eventually starting a family in the same place. The creation of more single-family housing and child-friendly neighbourhoods in places like Leidsche Rijn (Utrecht), IJburg (Amsterdam), and Ypenburg (The Hague) has enabled families to stay in urban areas. And as Zukin (Citation1995) pointed out cities have regained popularity as centres of new employment and possibilities for consumerism and culture, and parents are ‘reinventing’ the city as a place to live (Karsten Citation2014).

With a population of more than 17 million people and growing, the Netherlands is a densely populated country (ranked as the 22nd within density rankings from the World Bank). Currently about 75% of the population live in cities, with the Dutch Environmental Assessment Agency (PBL) projecting that in the following decades three-quarter of the population growth will predominantly take place in urban areas (PBL Citation2016b). As a consequence of constant growth and transformation, the built environment of the Netherlands has substantially grown in the last decades and is characterised by a polycentric urban structure, and as a melting pot of urban cores at relatively short distances from each other.

As a response to and recognising that cities within the Netherlands are ‘engines of the economy’, in 2015, the Dutch Government launched ‘Agenda Stad’ (Rijksoverheid Citation2015), a national urban agenda to promote economic growth, improve liveability and stimulate innovation in urban areas. As an addition to this agenda, the PBL (Citation2016a) published a report titled ‘De stad: magneet, roltrap en spons. Bevolkingsontwikkelingen in stad en stadsgewest’ (The City as a Magnet, an Escalator and Sponge) where a long-term vision of the population and spatial development was envisioned. The metaphor of ‘the magnet, escalator and sponge’ is used to describe the shifting population dynamics in cities and their increasing popularity as places to live. Cities also grow as a result of (im)migration, and this cohort belongs to the age group who are just before or in a stage of life where they are looking to have children (CBS Citation2017a). This can be seen through the growing number of families with children in the four main cities (Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht) of the Netherlands, though this number is decreasing at the national level.

Various studies have shown that families deliberately choose to live in the city and the trend of young people moving from cities to suburbs once they have a family is slowly reversing. Research by Karsten (Citation2007), for example, analyses why these households disconnect the seemingly traditional relationship between families and the suburbs. Underlying their settlement choice is identified as, (1) Time and geographical reasons: Residential location is a key factor to combine childcare with paid work, which often takes place in the same city. Not only the location of the workplace is a strong determinant of their residential location but also the broad range of urban cultural activities that the city has to offer; (2) Social embeddedness: The diverse composition of the city provides many opportunities to connect with other people. This can have a mutual benefit for both the parents and the children. Children connect families who live in close proximity, these connections can then develop into supportive communities with mutual benefits for exchange of assistance and advice; (3) Identification as true urbanites: Families living in cities construct an identity of themselves as resolute families that can deal with negative sides of living in the city. They recognise there are serious considerations for living in the city but define themselves as city people who could not live anywhere else. As Karsten (Citation2007) notes that the choice of residential location is subject to continual reflection and renegotiation.

Questions, however, still remain on whether the increase of families in cities is a structural or a temporary phenomenon. Boterman and Karsten (Citation2015) predict that this trend of urban families in cities will persist for a while. In particular, families with strong cultural capital ties who will want to stay in the city. Traditional lines of separation between domains that exclusively belong to adults and exclusively to children are fading. Some neighbourhoods specialise in this kind of environment. In Amsterdam for example, families as consumers are becoming increasingly visible. Cafes serve ‘babychino’ (a child=friendly variant of cappuccino), cultural programmes in the city targeted at children (museum activities) are a few examples (Leclaire Citation2015). These city neighbourhoods are transforming to welcome the settling of families with children. It will not be the increasing number of migrants, shrinking birth rates, it is the middle-class (and upper classes with affordability) who will bring new children to the city (Boterman Citation2012 with emphasis added by author). Other examples include municipal initiatives from the city of Rotterdam, ‘Building Blocks for a Child Friendly Rotterdam’ or ‘Kindvriendelijke bouwblokken’, or the development of the Kindlint as a safe route for children that encourages independent mobility around the neighbourhood.

Positioning learnings in context

Based on the findings from the quantitative and qualitative data from the four neighbourhoods, we can position specific learnings and challenges of the neighbourhood along certain thematic lines. With the help of indicators based on the urban environment and systematic methods of data collection, cities can assess their levels of addressing child-friendly planning and understand changes overtime.

Streets and perceived safety levels

Despite the various measures taken for street safety within all the four neighbourhoods, perceived safety in the street is low in all of them. In three out of the four neighbourhoods (De Bergen, Woensel-West, Lakerlopen), more than half of the parents admit that they do not find the streets safe for their children to play in. A recurring observation was the number of cars on the street and the attitude of the drivers, apart from these, reasons such as speeding cyclists in De Bergen, bad visibility in the streets of Blixembosch-Oost deter parents from encouraging their children to play outside. While some parents are able to cope with this, like this parent in Lakerlopen, ‘…don’t do stupid things, then it’s safe’, for most parents this was not the case. Interestingly, in De Bergen, children were even less satisfied with their safety than their parents. Of the children who participated in the intensive workshop within the neighbourhood, only one-third of the children found the street safe to play in, but half of the children said they do regularly play in the street anyway (responses were a mix of personal and parents’ choice).

Of all the four neighbourhoods, Blixembosch-Oost was the neighbourhood where parents considered the streets safest. Blixembosch-Oost, a suburban VINEX neighbourhood from the early 90s (for more about the VINEX policy see Galle and Modderman Citation1997), consists mainly of access roads that also have a low intensity of use. Although traffic safety remains a challenge, two-third of the parents were satisfied in this neighbourhood with regard to safety. One parent answered, ‘as a mother I am not satisfied, but in comparison to other neighbourhoods, then yes I am. If I had to give it a grade, it would be a seven (out of 10)’. Though levels of perceived safety were quite high, play activities in this neighbourhood do not take place on the street but more within assigned play areas (e.g. playgrounds). However, the abundance of play facilities around the neighbourhood appears to deter from playing on the streets.

Parents from De Bergen on the other hand were concerned about the speed of traffic, and when asked about how to improve this situation, almost all of them pointed towards traffic calming and more visible safety measures: ‘Make the neighbourhood car-free, make the bike lanes safer and provide less parking for tourists.’ One of the parents mentioned cases where speeding cars crashed into people’s home. Others stressed on creating better signages and control. Interestingly, it was not only traffic-related reasons that contributed to lower perceived safety levels, but also social factors. While these findings are not new, they are in line with earlier research of ‘stranger danger’ that appears to cause parental anxiety in relation to their child’s safety in the neighbourhood (Carver et al. Citation2008). Findings from this research follow the same pattern. Examples include the presence of homeless people in De Bergen, and (activities related to) prostitution and drug abuse in Woensel-West. It was not only the adults who contributed to the feeling of being unsafe but also presence of older children (teenagers) in some locations as the workshop with the children evidenced.

The perceived safety levels can also be related to the popularity of walking around the neighbourhood. The data showed that Woensel-West was the least popular neighbourhood to walk in. Respondents said that though the neighbourhood has improved from previous years parents generally do not let their children walk or play around the neighbourhood unsupervised. Parents regularly check up on them after some time or make agreements about how far the children can go, one example being ‘the kids walk on the streets by themselves. I let them walk to the playscapes sometimes, but after a few minutes I will check if he is alright’. De Bergen and Blixembosch-Oost are considerably more popular neighbourhoods to walk in, with Blixembosch-Oost being recognised for its safety levels and social control.

Designated play versus undesignated play

The importance of outside play has been stressed in literature ranging from health to children’s geography (Hinkley et al. Citation2008, Aarts, Wendel-Vos, Oers, Goor, & Schuit, Citation2010, Vries and Veenendaal Citation2012, Christian et al. Citation2015). Within our research, we found that the majority of children play outside every day, and that they play mostly in designated play areas i.e. places of organised play (such as the playground, sports field, schoolyard, park) rather than undesignated playing areas (such as streets or sidewalks).

The ample availability of designated play areas in all the four neighbourhoods can be identified as the primary reasons for this behaviour (see ). We should note here that though designated areas are easy to identify visually and spatially, undesignated playing areas are more difficult to determine. More so as these spaces cannot be identified through analysis and observation alone but need input from children and/or parents to point out where else play happens. Between the four neighbourhoods, outside play in designated areas were most evident in Blixembosch-Oost (by observation) and undesignated play areas were most evident in De Bergen (by observation and the workshops).

The number of designated play areas in Blixembosch-Oost (almost double in comparisons other neighbourhoods) appears to encourage outside play. Though number of parents complained about the quality of playgrounds and that there were not enough spaces tailored for older children. ‘We need more spaces for teenagers; all playgrounds are for little children. And I see teenagers hanging around the playgrounds’, says one parent of two children under the age of 10. Parents appeared largely satisfied with the quality and number of available facilities. Other observations included the need for variety of playgrounds, natural, sport, and creating more attractive play and activity spaces (urban farms for example). In comparison with Blixembosch-Oost, quarter of outside play in Woensel-West happened on the streets. Identified as a transition neighbourhood (along with Lakerlopen), Woensel-West is the only neighbourhood in the city where the Kindlint () was introduced to provide a safe route for children through the neighbourhood connecting school, playgrounds and the park (Wassenberg and Milder Citation2008). Based on a workshop with elementary school children in the neighbourhood about the Kindlint, the children are yet to grasp the meaning or knowledge of the various safety elements along the route (e.g. posts for a safe crossing). Interestingly, the children indicated various elements along the route – designated or not – as places for play. Though levels of perceived safety were low, children were still allowed to play on the streets, more so as the number of designated play spaces were low.

Between all the four neighbourhoods, parents emphasised the need for more centralised and diverse play spaces, and improvements to the playing environment. Like a participant in Woensel-West said: ‘I want the play areas to be bigger and more together. Not one piece of play‐equipment on every street, but a bigger dedicated place where not only children but also parents can gather’.

A common observation was the absence of activities for parents or waiting spaces while the children played in designated spaces. It was also striking that all the answers about possible improvements were about designated play areas and nothing was mentioned about adapting undesignated play areas. One of the advantages of undesignated play spaces is the accessibility for all children (Wilson Citation2012). The workshop with children in De Bergen revealed that the children appreciated undesignated play areas because they were close to their homes, especially when designated play areas were difficult to reach or further away. Moreover, with undesignated spaces, children can temporarily own and imagine various possibilities about these spaces, encouraging a large variety of play themes: what game can I play here? (Frost Citation1992). Car-parks that are accessed by placing a brick under the garage doors, some appropriation of sidewalks and private courtyards (e.g. Bourbonhof in De Bergen) were some examples. As streets were considered unsafe by children in De Bergen, a private courtyard of a gated community appeared to be a popular alternative to cope with the capricious city environment.

Of the interviewed children in De Bergen, there was also a big difference in preference of play spaces between genders. Girls were more negative about the place and identified bad maintenance as a deterrent to play, the variety of play equipment and the threat of older teenagers were other nuisances pointed out. Boys wanted to see improvements on the maintenance of the soccer field and additions of more sport facilities. Interestingly, they both point out that more attention needs to be paid to diversity of ages within the neighbourhood.

Urban green spaces

Urban green spaces (UGS) over the past years have become central to a number of research themes, sustainability, physical health, mental health and safety (Barrera et al. Citation2016). Studies show that accessibility to and the presence of green attracts play, which is important for physical, social and cognitive development of young children (Louv Citation2005, Amoly et al. Citation2014). Children’s access to local child-friendly environments, including green spaces, contributes to sustainable development in several ways, like diminished car transportation and support for children’s healthy development, physically active free play and concern for the environment (Jansson et al. Citation2016).

The issue of accessibility to UGS is one of the crucial aspects of sustainable urban planning, and it is linked to the growing concern about the well-being of urban population, particularly in children (Gupta et al. Citation2016). Studies from the perspective of the child on the design of urban green spaces show that children felt that the management of their local environments was not adapted to their preferences (Roe Citation2006). This appears to be the case for Eindhoven as well in terms of use and accessibility to urban green spaces (). While the data were collected independently for play and green, in practice, however, they are closely related to each other. The embedding of playgrounds in green areas often provides opportunities for play (natural playgrounds for example) or just an informal patch of green in front or back of the house.

Within the inner-city neighbourhood of De Bergen, the park is the most visited greenscape for play according to findings from the children’s workshop. This was confirmed by the data from the survey with the parents. Remarkably, this park has no specific play facilities for children. The children invent their own games or make creative use of what is already there, like using an art object as a playset to climb on. The design of the Anne Frankplantsoen (De Bergen’s city park) and its enclosed character also provides possibilities for informal group play, like hide and go seek for example. During the workshop, an eight-year-old girl described how through their own imagination she created a park that was the exclusive domain of the children. This description fits in line with the research that shows that play in a natural environment is more varied than play in non-natural play spaces. Play in natural environments is also more sensational, explorative and constructive (Berg, Koenis, & Berg Citation2007). Natural playgrounds, like the ones that can be found in Blixembosch-Oost, are especially suitable for this.

Blixembosch-Oost is the neighbourhood with the most greenery from the cases researched. Because of its suburban character, it has the highest volume of private gardens, which also contributes to the green character of the neighbourhood. Most of the greenery in Blixembosch-Oost have double functions, as a playground as well as a grass field for aesthetic purposes. This doubling of functions translates to a high quantity of different play opportunities in this neighbourhood. This quantity and quality of green also appears to contribute to the high rate of outdoor play in designated spaces in Blixembosch-Oost.

With the other neighbourhoods, quality and access to green was much lower. A number of parents raised this issue including a parent in Lakerlopen: ‘A larger park would be nice, there are a large number small green patches in the neighbourhood, but still a single large one would be nicer’. Parents also gave examples of what they would like in terms of the greening of streets and the addition of play spaces. Findings of the workshop also highlighted importance of greening schoolyards. These findings fit in the line with a push towards increasing green Dutch schoolyards (NOS Citation2017).

Impacts and role of the socio-cultural environment

Within a community, the physical (built and natural) environment cannot be detached from social, economic and political realities of the neighbourhood. While the role of the physical environment is central to the well-being of children, from the need for walking and cycling facilities to the preservation of green space, social and cultural features also shape behaviours and permeate into activities within the neighbourhood. Though contestations exist within research on parental values among high-, middle- and low-class families on raising children, the difference between access to activities and amenities was evident through this work. The relatively affluent neighbourhood of Blixembosch-Oost appears to have very different forms of activities and social capital in comparison with Woensel-West or Lakerlopen (parent groups, neighbourhood organisations, children’s play groups etc.). With diverse immigrant status ranging from Turkish, Moroccan, other African and Asian backgrounds, Woensel-West and Lakerlopen typify a very visible generational upward mobility of migrant families. The gentrifying De Bergen is a neighbourhood composed of mostly well-educated upper-middle-class families where almost all have a native or highly skilled immigrant background.

Given the diversity in the spatial layouts and demographic composition of these neighbourhoods, it is noteworthy, that the parents from all four neighbourhoods were generally satisfied with the wide range of services and the quality of the social environment in their neighbourhood. For example, in Blixembosch-Oost, parents and children felt very welcomed in various local business and valued the friendly environment of semi-private and commercial spaces within the neighbourhood. The neighbourhood also had the highest number of private and commercial activities available for children through neighbourhood organisations. Blixemkids, one such example, is a group of volunteers organising activities for children, an interviewee expands: ‘We celebrate Sinterklaas for example, and on National play day Blixemkids brings waterslides, inflatable bouncers and more’. Although positive, multiple interviewees identified the importance of (and absence of) a mixture of people from different backgrounds: ‘We think the culture of the people in this neighbourhood is “too white”. Nowadays we live in a multicultural society and I want my children to grow up knowing this multicultural society’.

In contrast to Lakerlopen, where activities for children are not as common (‘there are a few activities, and they’re organised just once a year’, says one parent) and support groups for parents are less known or even wanted. A parent who is aware of such activities highlights ‘There is a support group for parents at the elementary school, but we don’t go or need that (she didn’t expand on the reasoning)’. Based on the small sample size here, it is hard to position the reason behind this. Conversations with neighbourhood co-ordinators also highlighted low levels of participation within activities organised by the neighbourhood association. One of the interviewees’ observed that the organisation itself, and therefore the activities, might be a bit outdated since there are only seniors on the boards of these organisations. In line with Bell et al. (Citation2008), who underpin the importance of having a varied group of citizens participating in community groups to create the feeling of communal ownership for the success of any participation process.

By far the most diverse neighbourhood within the study, Woensel-West has been successful in banding together to realise the Kindlint (child-route) and organise various community activities. The diversity of this neighbourhood also leads parents to comment on the need for more inter-communal activities. ‘…add more common activities for different groups, promote more mixing of people or children with different backgrounds’, observed one parent. Some parents raised concerns on the presence of the red-light district close by and others noted that the differences in socioeconomic status implied variance in access to amenities. ‘While they have the means to access services and special care, not all families have that ability (lower income, lesser social networks). Also, improvement of (mis)communication between people in the neighbourhood through lack of Dutch language comprehension’. The observations from the parents are noteworthy example of how different community concerns need to be addressed and mitigated

An interesting observation was found in De Bergen, where semi-private and commercial spaces were considered least inviting for parents with children. Although there are some very positive rated commercial spaces (e.g. those especially aimed towards children), residents identify the conflict of interest between the commercial (restaurants, bars etc.) and the living areas as an issue for future improvement. While commercial activities formerly exclusively belonged to adults, parents note that lines between adult- and child-oriented spaces are fading.

The neighbourhood has been successful in encouraging various co-creative initiatives for child-friendly environments, while attracting skilled native and international workers. Reflecting on the active involvement of its residents and civil society organisations, Stadstuin de Bergen located in the heart of de Bergen is one such example (). The aim of the resident led initiative is to transform a decayed parking space and playground in its close proximity into an environment that facilitates interaction between residents, children and civil organisations. Funded through the municipality and in kind by the various neighbourhood organisations and local entrepreneurs, activities such as greening, children’s play activities, possible activities for care facilities for differently abled people are some of the possibilities that are being explored.

Conclusions and recommendations

In the context of the Netherlands, the visibility of children in cities is growing and importance of children’s geography in planning and design is becoming increasingly relevant. With growing diversity in urban areas, cities need to develop mechanisms through which the interests of young children and families are better represented and articulated within planning and design.

The results of this research from four neighbourhoods in Eindhoven on child-friendly public spaces both confirm patterns of consumption and use as reported in literature, and also add new insights for urban design. The role that urban planning and design can play in highlighting the validity and agency of children’s geography in planning processes is vital within the changing profile of cities. It is useful here to distinguish between the following, role of urban planning and design can play in highlighting the importance of children’s geographies, the levels of possible interventions, bottom-up and top-down, and accommodating for changing demographics in cities. However, more research is needed to position differences between needs of young and older children, gendering of spaces, needs for early childhood development, etc. This can be seen through the issues raised regarding safety, awareness, maintenance, and more family-friendly spaces, which can be addressed at various scales and levels of interventions.

Some possible urban design interventions include:

Adding playful street furniture: Streets are potential places for children to learn and play. Research identifies adding urban furniture around the neighbourhood could facilitate observing children at play. Adding a bench between the street and home can have two functions, a buffer between private and public spaces, and increase opportunities to connect with neighbours and other children.

Climbable objects: Any object can become an element to scramble up on: a piece of art in the park, some steel objects on the sidewalk, a tree trunk etc. For children, climbing on objects is more than just fun. Scaling an object teaches them vital lessons, such as dexterity, risk assessment, focus and planning. They have to decide how high they are comfortable to climb and find the best way to get there.

Possibility for sidewalk games: Outside play is not restricted to designated play spaces only but should extend to public space at large. Playing games on the sidewalk encourages more types of social play, introduces a larger variety of play themes, and increases social interaction. Sidewalks also provide access to all children to use it as a play space.

Playful street crossings: Cities today are actively aiming to improve their neighbourhoods through a multitude of interventions. By creating interesting street crossings, neighbourhoods can increase their aesthetic appeal, benefit pedestrians and raise awareness. Streets crossings can be community projects, art installations by famous artists or children’s school projects. The scale and scope depend on its residents.

Designing for flexible use: Schoolyards are locations that are only used at certain times of the day and mostly only during weekdays. School yards have a potential to become much more than just a playground during school hours. For example, they can be opened up as play spaces in the weekend, neighbourhood event spaces, summer activities etc. Other examples including designing playscapes for various abilities rather than age can include elements for both younger and older children, without being prescriptive on age or who uses what.

Neighbourhood child route: Cities are now responding to the growing trend of attracting families within their boundaries by actively looking at family-friendly developments. Though there is a long way to go to create family-friendly cities, incremental shifts can create more awareness. Neighbourhood child routes can be created with the residents of a neighbourhood to connect community and child identified important spaces. By connecting them visually, the route can become a play-route to various destinations or a destination in itself with a number of play elements. This can increase independent mobility for older children, road safety, visual awareness and community building, by putting children at the centre of the exercise.

Acknowledgements

The author of this paper would like to thank the Bernard van Leer Foundation for funding this work (project no. NET-2016-084).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sukanya Krishnamurthy

Dr Sukanya Krishnamurthy is an Assistant Professor of Urbanism and Urban Architecture at the Faculty of the Built Environment at Eindhoven University of Technology (Netherlands). Her main focus lies at the interface of urban and cultural geography, where her scholarship analyses how cities can use their resources and values for better inclusive and sustainable development.

References

- Aarts, M.-J., et al., 2010. Environmental determinants of outdoor play in children: a large-scale cross-sectional study. American journal of preventive medicine, 39 (3), 212–219. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2010.05.008

- Amoly, E., et al., 2014. Green and blue spaces and behavioral development in Barcelona schoolchildren: the BREATHE project. Environmental health perspectives, 122 (12), 1351–1358. doi:10.1289/ehp.1408215

- Authier, J.Y. and Lehman-Frisch, S., 2012. Le Goût des Autres: gentrification Told by Children. Urban studies, 50 (5), 994–1010. doi:10.1177/0042098012465127

- Barrera, F.D.L., Reyes-Paecke, S., and Banzhaf, E., 2016. Indicators for green spaces in contrasting urban settings. In: Ecological indicators. Vol. 62, 212–219.

- Bell, J., Vromen, A., and Collin, P., 2008. Rewriting the rules for youth participation: inclusion and diversity in government and community decision making [online]. Commonwealth of Australia. Available from: https://docs.education.gov.au/node/29376

- Boterman, W., 2012. Residential practices of middle classes in the field of parenthood [online]. Amsterdam: UvA. Available from: http://dare.uva.nl/search?arno.record.id=420437

- Boterman, W. and Karsten, L., 2015. De opmars van het stadsgezin. In: F.V. Dam, ed. De stad: magneet, roltrap en spons. Den Haag: PBL, 118–127.

- Bowles, J., Kotkin, J., and Giles, D., 2009. Reviving the city of aspiration. New York: Center for an Urban Future.

- Butler, T., 2003. London calling. The middle classes and the remaking of inner-London. Oxford: Berg Press.

- Carroll, P., et al., 2015. Kids in the city: children’s use and experiences of urban neighbourhoods in Auckland, New Zealand. Journal of urban design, 20 (4), 417–436. doi:10.1080/13574809.2015.1044504

- Carver, A., Timperio, A., and Crawford, D., 2008. Perceptions of neighborhood safety and physical activity among youth: the CLAN study. Journal of physical activity & health, 5, 430–444. doi:10.1123/jpah.5.3.430

- CBS, 2017a. 2016: grote steden groeien door geboorten en immigratie. Available from: https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2017/01/2016-grote-steden-groeien-door-geboorten-en-immigratie

- CBS, 2017b. Bevolking en huishoudens. Available from: http://statline.cbs.nl/Statweb/selection/?DM=SLNL&PA=82245NED&VW=T

- Christian, H., et al., 2015. The influence of the neighborhood physical environment on early child health and development: a review and call for research. Health and place, 33, 25–26. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.01.005

- Frost, J.L., 1992. Play and playscapes. Albany, NY: Delmar. G.

- Galle, M. and Modderman, E., 1997. Spatial planning in the Netherlands current developments and debates. Netherlands journal of housing and the built environment, 12 (1), 9–35.

- Gupta, K., et al., 2016. GIS based analysis for assessing the accessibility at hierarchical levels of urban green spaces. Urban forestry and urban greening, 18, 198–211. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2016.06.005

- Hinkley, T., et al., 2008. Preschool children and physical activity: a review of correlates. American journal of preventive medicine, 34 (5), 435–441. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.02.001

- Hjorthol, R. and Bjornskau, T., 2005. Gentrification in Norway: capital, culture or convenience? European urban and regional studies, 12, 353–371. doi:10.1177/0969776405058953

- Jansson, M., Sundevall, E., and Wales, M., 2016. The role of green spaces and their management in a child-friendly urban village. Urban forestry and urban greening, 18, 228–236. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2016.06.014

- Jong, A.D., Vriens, J., and Beets, G., 2016. De stad: magneet, roltrap en spons. Bevolkingsontwikkelingen in stad en stadsgewest. Available from Den Haag: http://www.pbl.nl/sites/default/files/cms/publicaties/PBL_2015_De%20stad_magneet,%20roltrap%20en%20spons_1610.pdf

- Kaboom, 2017. The state of play. Available from: https://kaboom.org

- Karsten, L., 2007. Housing as a way of life: towards an understanding of middle-class families’ preference for an urban residential location. Housing studies, 22 (1), 83–98. doi:10.1080/02673030601024630

- Karsten, L., 2013. From yuppies to yupps: family gentrifiers consuming spaces and re-inventing cities. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie, 105 (2), 175–188. doi:10.1111/tesg.12055

- Karsten, L., 2014. De Stad 3.2, of hoe gezinnen de stad opnieuw uitvinden. Stedebouw & ruimtelijke ordening, 95 (3), 10–16.

- Karsten, L. and Vliet, W., 2006a. Children in the city: reclaiming the street. Children, youth and environments, 16 (1), 151–167.

- Karsten, L. and Vliet, W.V., 2006b. Increasing children’s freedom of movement: introduction. Children, youth and environments, 16 (1), 69–73.

- Krishnamurthy, S., et al., 2018. Child-friendly urban design: observations on public space from Eindhoven (NL) and Jerusalem (IL). Netherlands: Eindhoven University of Technology.

- Leclaire, A., 2015. Het stadskind drinkt pumpkin latte. Available from: https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2015/11/07/het-stadskind-drinkt-pumpkin-latte-1553798-a1032327

- Lilius, J., 2014. Is there room for families in the inner city? Life-stage blenders challenging planning. Housing studies, 29 (6), 843–861. doi:10.1080/02673037.2014.905673

- Louv, R., 2005. Last child in the woods. North Carolina: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill.

- Matthews, H., 2003. Inaugural editorial: coming of age for children’s geographies. Children’s geographies, 1 (1), 3–5. doi:10.1080/14733280302183

- Musterd, S. and Ostendorf, W.J.M., 2012. Inequalities in European cities. International Encyclopedia of housing and home, 4, 49–55.

- Niekerk, F., 2012. De duurzame stad is vaak niet kindvriendelijk. Dilemma’s voor kindvriendelijke ruimtelijke planning. Rooilijn, 45 (1), 44–51.

- NOS, 2017. Lekker vies worden op het groene schoolplein. Available from: http://nos.nl/artikel/2165920-lekker-vies-worden-op-het-groene-schoolplein.html

- PBL, 2016a. De stad: magneet, roltrap en spons. Bevolkingsontwikkelingen in stad en stadsgewest. Den Haag: Plan Bureau voor de Leefomgeving.

- PBL, 2016b. PBL/CBS prognose: groei steden zet door. Available from: https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2016/37/pbl-cbs-prognose-groei-steden-zet-door

- Rijksoverheid, 2015. Agenda stad: samenwerken aan de toekomst van stedelijk Nederland. Available from: https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/brochures/2015/01/09/agenda-stad-factsheet

- Roe, M., 2006. ‘Making a wish’: children and the local landscape. Local environment, 11 (2), 163–182. doi:10.1080/13549830600558465

- van den Berg, A.E., Koenis, R., and van den Berg, M.M.H.E., 2007. Spelen in het groen. Effecten van een bezoek aan een natuurspeeltuin op speelgedrag, de lichamelijke activiteit, de concentratie en de stemming van kinderen. Wangeningen: Alterra.

- Vries, S.D. and Veenendaal, W.V., 2012. Belang van buitenspelen. Literatuurstudie naar de gezondheidswaarde, de sociale en de economische waarde. Lichamelijke Opvoeding, 2, 37–39.

- Ward, C., 1977. Child in the city. London: Architectural Press.

- Wassenberg, F.A.G. and Milder, J., 2008. Evaluatie van het project Kindlint in Amsterdam. Onderzoeksinstituut OTB. Available from Delft: https://repository.tudelft.nl/islandora/object/uuid%3A80ee632e-ed87-493f-89d4-ae938a01e3e4

- Wilson, P., 2012. Beyond the gaudy fence. International journal of play, 1, 30–36. doi:10.1080/21594937.2012.659860

- Wridt, P., 2010. A qualitative GIS approach to mapping urban neighborhoods with children to promote physical activity and child-friendly community planning. Environment and planning B, 37 (1), 129–147. doi:10.1068/b35002

- Zukin, S., 1995. The cultures of cities. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.