ABSTRACT

The north-western city of Turin, Italy, well known for the FIAT car industry, representing the leading Italian example of a one-company town, ranks the highest Italian level of PM10 air pollution, among the worst in Europe. According to epidemiologists, children’s health in Turin is severely affected by air pollution, primarily originated from private motorized traffic. Based on this data, a complaint against Turin’s Mayor was recently filed by a citizen who hypothesized the City’s violation of the right to a healthy city for everyone. However, children’s right to breathe unpolluted air is even more jeopardized in poorer neighbourhoods, where no traffic restriction policies are implemented, unlike the privileged and wealthy historical centre. Our research approach aimed at experimenting some low-cost interventions, acting simultaneously on the material and cultural conditions negatively influencing both public policies and citizens’ behaviour. Actions with younger children and parents’ participation in monitoring and mapping air quality as well as re-shaping public spaces for a healthier and playable city are presented and discussed as key points for successful implementation and dissemination policies in Turin and elsewhere.

Introduction

The research project ‘Actions against air pollution in Turin for a healthy and playable city’, winners of the Urban95 Challenge competition launched by the Bernard van Leer Foundation, was carried out in Turin (Italy) from June 2017 to March 2018.

Urban95 asks a simple question: if you could see the city from an elevation of 95 cm – the average height of a healthy 3-year-old child – what would you do differently?

Our team of professionals from various fields related to urban sciences: environment, childhood and participatory processes share a deep concern about the severe effects of air pollution on children’s health in Turin. They reformulated the question: what kind of air does a child breathes at 95 cm in Turin? and how could bottom-up strategies help the more socially disadvantaged children to reduce short-run health hazards due to air pollution? Hence, the project set and tested actions for this urgent purpose and, in the long run, to improve the city’s air quality as well as reshaping liveable and playable public spaces.

Air pollution and sick children

Italian society should have seriously taken into account Ward’s warning about our dying cities: ‘Every step the city takes to reduce the dominance of motor traffic makes the city more accessible to the child. It also makes life more tolerable for every other citizen’ (Ward Citation1990, p. 21).

Instead, mobility policies based on private transport and fossil fuels are still dominant, entailing loss of public open space for play and social interaction and intolerable levels of air pollution (Breathelife Citation2018a) whose negative effects on adults and children’s health are widely documented by scientific research and epidemiological studies:

there is a direct correlation between high levels of air pollution (NOx, PM10, PM2.5) and asthma, pneumonia and bronchitis; recent studies on pregnant women’s exposure to smoke suggest that air pollution can cause changes to the offspring’s DNA methylation patterns (Southampton Citation2016);

children are the most exposed and vulnerable to air pollution, even in the foetal phase; when regularly exposed to high levels of air pollution they cannot properly develop their respiratory system, therefore suffering lifetime chronic respiratory failure (Breathelife Citation2018b);

many studies suggest a correlation with lung cancer, especially caused by PM10, and a reduction of life expectancy (Berti et al. Citation2016, Cadum et al. Citation2016);

brain abnormalities have been observed with the risk of cognitive impairment (Guxens et al. Citation2018).

In the urban context, children are the most exposed to air pollution: Particulate Matter can reach larger concentration near ground level (Sun et al. Citation2013). Even inside cars, the air filters do not protect from external air pollution; on the contrary, because the ventilation intake is collecting toxic gases from all the vehicles around, the air can be worse inside than outside (Guardian Citation2017).

Turin, the context and the challenges

Nowadays many countries are implementing measures against air pollution, while Italy lacks policies at any scale. Despite the fact that the entire Po Valley, in Northern Italy is surrounded by mountains, it is severely polluted due to multiple interacting factors, both the urgent site-specific and effective actions as well as long-term plans on a large scale are yet to be adopted. Turin, located in a basin to the west of this polluted territory, shows the most challenging and severe data: PM10 air pollution is ranking the highest at the national level and among the worst in Europe. In 2017 the EU PM10 safety limits were largely exceeded: 118 days per year (limit: 35) with daily values higher than 50mg/m3 and yearly average value equal to 47mg/m3 (limit: 40mg/m3).

In addition to the disadvantages of its topography, Turin suffers from historical City subalternity to the FIAT/FCA corporation and private car mobility. Compared to other European big cities, it has a high motorisation rate (650 cars/1000 inhabitants) and a low pedestrian/bike mobility share, while a dramatic public debt prevents the City from strengthening and modernizing an outdated public transportations system. The case is so severe that a complaint against the Mayor for violating citizens’ right to a healthy city was recently filed by a group of citizens (www.torinorespira.it).

The inner historical city has undergone a wide gentrification process and is the only area where cars’ access to non-residents is restricted to a few hours a day. Neighbourhoods like Vanchiglia just outside the ZTL (Limited Traffic Zone), in addition to being neglected and impoverished because of the occupational crisis, bear the double burden of their own traffic as well as the traffic forced outside the ZTL. Therefore, spatial injustice (Soja Citation2010) doubly affects children living in those neighbourhoods. Many suffer both from their families lower economic, ethnic or social status and the chronic unhealthy air quality (particularly affecting the younger ones), as well as a lack of green and play areas in their neighbourhood. Our choice to act in the Vanchiglia neighbourhood is precisely motivated by the above mentioned critical issues.

Aims and actions undertaken

The aims of the project had been:

to mitigate the air pollution exposure for kids from 0 to 5 years old in the neglected neighbourhood of Vanchiglia by identifying less polluted routes from homes to kindergarten and playgrounds to be reached by biking or walking instead of by car;

to test strategies and methodologies for achieving structural urban transformation, car traffic reduction, pedestrian and bicycle mobility in the disadvantaged area of Vanchiglia.

to help the City Council to implement and disseminate low-cost intervention, acting simultaneously on the material and cultural conditions that negatively influence the issue of air quality.

More precisely the project’s actions have been undertaken along six major themes.

1. awareness creation among citizens on the air quality-child health link:

training with experts of the Regional Environmental Agency (ARPA)

public meetings with health and mobility experts ()

information and training meetings with teachers and children’s parents of the kindergarten ‘Gianni Rodari’ ()

fostering the participation of volunteers.

2. knowledge building among children on main air features, on air pollution sources, mobility and the right to playable public spaces:

labs at the kindergarten ()

urban exploration and discovery ()

setting-up and participation in outdoor activities (bike-pride, Spring party)

3. involvement of the neighbourhood:

bike-pride crossing the neighbourhood's most crowded and polluted street ()

spring party in a square usually invaded by parked cars ()

posting children’s artworks in the neighbourhood

4. monitoring indoor and outdoor air quality (PMx, NOx, O3, VOCs):

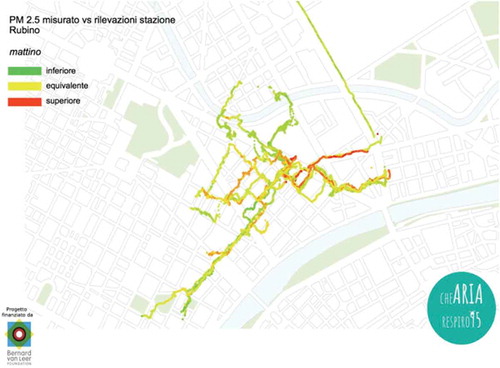

citizen science monitoring campaign carried out by parents in the house-to-school journey by means of portable low-cost devices ()

air quality monitoring in a selected kindergarten classroom (https://cheariarespiro.files.wordpress.com/2018/05/mappatura-aria-outdoor-it-en.pdf)

5. public administration involvement:

meetings and information exchange with: major deputies, neighbourhood administrators, city counsellors, local police department

6. communication (press, TV, web and social media):

sponsorship of events and activities

design, networking and management of internet media

journalists (TV and press) networking

Outputs and achievements

Main outputs of the project have been the following:

a web blog (https://cheariarespiro.wordpress.com/about-2);

an information e-booklet (https://cheariarespiro.wordpress.com/libretto-informativo/) to build citizens’ awareness with 10 questions&answers summarising the main cause/effect relationship of air pollution issues and some mitigation strategies;

a toolbox containing guidelines based on: information, involvement, communication, participation, experimental actions on public spaces, the permanent transformation of public spaces, replicability at small group scale (about 20 to 40 children and 40 to 50 stakeholders). The relevant steps to be performed and the set of actions were addressed to the City Council and any other actors willing to participate in the air quality improvement challenge (https://cheariarespiro.wordpress.com/toolbox-en/).

Other outputs documented on the web blog:

children’s artworks and road signs made during pre-school labs with our team and with teachers’ support ();

neighbourhood air pollution maps (https://cheariarespiro.wordpress.com/about-2/#jp-carousel-2256) ();

design of urban transformations and visual maps ();

methods for temporary transformation of streets and squares into pedestrian areas, available for public use (signposting installations, social activities, play, cycling) ().

All these outputs proved to be useful in order to achieve the following children-oriented goals:

children’s consciousness building on air pollution sources, on adults’ responsibilities and on their right to well-being, play and safe living conditions.

children’s health hazard mitigation: both urban transformations and habits are long term issues, effects will occur in the aftermath of the project and will be increasingly measurable as the project will be replicated at city and metropolitan level. Nonetheless the pollution maps that have been produced can be used immediately to choose the less polluted streets.

children’s well-being: their ideas and desires about public space transformation have been turned into possible reality within the participated Spring day, thus providing a lively experience of a ‘playable city’. It also enhanced the self-esteem and confidence of adults as actors of transformation.

children’s reliance upon their parents’ stronger willingness to change, following their involvement in citizen science monitoring activity and participation in the project.

children’s environmental education provided by their teachers now more aware of environmental and health challenges and hazards, thanks to their involvement in the project.

Scaling up and implementing strategies

The best practices we developed in the project should be adopted by the City Council and Metropolitan Administration and scaled up by replication in all the kindergartens, reaching thus about 100,000 children under 5 years old out of 2 million inhabitants. For this purpose, on our blog, we had given free access and information to the methodology used for every performed action, the steps for consciousness building of personal responsibility towards children among parents, public administration and general population, scientific and popular literature review and open data on environment, air pollution measurements, etc. From the web blog, any user can also download the already cited toolbox and e-booklet.

Lessons learned

We outline some key points for the successful implementation of similar projects:

the number of public spaces reclaimed for children should be as numerous as possible;

neighbourhood inhabitants should be widely involved in the project’s activities;

when the promoters of Actions are NGOs or Social Movements, support from Public Administration and Environmental Regional Agencies has to be strongly claimed: information campaigns on health hazards, participatory processes on urban transformation and green mobility, etc., need permits, access to sensible data and structures.

We expect that the positive messages outlined above are likely to drive virtuous behaviours which, in turn, contribute to air pollution reduction.

Furthermore, we recall that some obstacles always hinder the successful implementation of similar projects:

it is difficult to replace bad habits (e.g. car use for mobility) with good ones;

inertia and lengthy time-scale of Public Administrations’ actions for urban changes (e.g. public transports enhancement, bike mobility support, public spaces’ reshaping and democratization, etc.) are killing citizen’s enthusiasm and expectations.

Future plans

We plan to support the City Council (official partner of our project) in a scaling up and wide metropolitan dissemination of the project’s outputs.

After the end of our project, we have been invited by the City Commission for Urban Planning and Mobility to present and discuss the outcomes of our project.

Among other specific issues, we suggested that the Mayor should create a special Office ruled by a children’s ombudsman whose task – among others – should be to implement the toolbox guidelines.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Elisabetta Forni

Elisabetta Forni is an Urban and Environmental Sociologist at Turin’s Politecnico (Italy) with long lasting experience on children in the city research. Author of various books and articles on that specific issue.

Emanuele Negro

Emanuele Negro is a Senior Environmental Physicist, with long lasting experience on energy, environment and sustainable development.

Chiara Carlucci

Chiara Carlucci is a freelance architect. She studied and worked in Berlin on her thesis 'Children’s right to the city', acquiring a deep knowledge on urban planning, children’s participation and mobility.

Angela Nasso

Angela Nasso is an architect, specializing in Urban Planning, Local Development and Environmental/territorial policies, citizen’s participation, stakeholders networking and sustainable mobility.

Mirjam Struppek

Mirjam Struppek graduated in Berlin and works as independent urbanist and festival curator on the sustainable liveability of public space transformed through new media and artistic participatory interventions.

References

- Berti, G., et al., 2016. Susceptibility factors and long term effects of air pollution: mortality among 3 sub-cohorts of the Italian Longitudinal Study. Results of the LIFE MED HISS project (LIFE12 ENV/IT/000834). doi: 10.1289/isee.2016.3936.

- Breathelife, 2018a. Available from: http://breathelife2030.org/solutions/ [Accessed 20 July 2018].

- Breathelife, 2018b. Available from: http://breathelife2030.org/the-issue/ [Accessed 20 July 2018].

- Cadum, E., et al., 2016. Long-term effects of air pollution in Turin, Northern Italy. In: Population-based cohort study, Life12 Med-Hiss Final Conference, Turin.

- Guardian, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/jun/12/children-risk-air-pollution-cars-former-uk-chief-scientist-warns [Accessed 20 July 2018].

- Guxens, et al., 2018. Air pollution exposure during fetal life. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.01.016

- Soja, E., 2010. Seeking Spatial Justice. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Southampton, 2016. Retrieved from: https://www.southampton.ac.uk/news/2016/04/health-impact-of-air-pollution.page [Accessed 20 July 2018].

- Sun, Y., et al., 2013. The vertical distribution of PM2.5 and boundary-layer structure during summer haze in Beijing. Atmospheric Environment, 74, 413–421.

- Ward, C., 1990. The child in the city, The Architectural Press, Oxford, 1978. New ed. London: Bedford Square Press.