ABSTRACT

This article sets the scene for the special issue of Cities & Health Journal on ‘Transforming cities and health: policy, innovation and practice.’ It focuses on systematic transformations to meet sustainability and climate goals whilst also placing health at the heart of policy change and action. Our intention is to raise broad issues drawing on multiple disciplines and provoke engagement with this area of underachievement. We ask:

How do we achieve action and momentum in transformational change?

What are the key components for future transformations in terms of governance, business models, time and sequencing, scaling, leadership and imagination?

Are there limits and barriers to what can be achieved?

Do these demands require a more radical and fundamental change and strategic direction?

In responding we note the policy-action gap and the failure to recognise the complexity in policy responses, the continuing growth of cities and the ongoing inability to address basic health needs, and we speculate about the changes that affect the context in which we work over the next decade. We highlight two case studies, where we are involved, that attempt to close the implementation gap and progress transformations. We then offer some further reflections in relation to research and practice in attempting to transform cities and health together to meet the Paris Agreement on climate change, the implementation of the UN SDGs and actions on biodiversity. In discussion we return to the current pandemic and what this tells us about this moment, future transformations and the possibilities and limits to action.

Preface

This introductory article for the special issue has been written in the period February to May 2020 at a time when the coronavirus has become a global pandemic affecting us all. This continuing context has influenced our writing and indeed at times our focus and concentration.

Introduction – where is the action?

In this paper, we offer some thoughts on urban futures and transformation in the light of the twin and complimentary objectives of sustainable development and human health.

As spaceship earth spins on through the twenty-first century, we will all need to clarify the frontlines in what is increasingly a battle for future population and planetary health. Several sub-systems, on which humanity depends are nearing the limits of their ‘safe operating space’, while others have already overshot. Through quantifying and qualifying these planetary boundaries, Rockström and Steffen hope we can ‘prevent human activities from causing unacceptable environmental change’ (Rockström et al. Citation2009, Steffen et al. Citation2015). These sub-systems underpin the ‘bio-geo-chemical stocks and flows’ that provide our ecosystem services, which in turn support all key determinants for human well-being and the resources for human flourishing (MEA Citation2005).

The demographic and resource significance of urban settlements is now well acknowledged. We argue here that humanity’s approach to physical city development, planning and design, and indeed all aspects of urban spatial governance, is pivotal in supporting both human health and global ecosystem health (Grant et al. Citation2017).

Widespread concern over such factors as the current focus on climate breakdown and the ecological crisis has neither encompassed nor addressed the problem. The academic knowledge base and the wealth of research that underpins it is not at all novel (Whitmee et al. Citation2015). Similarly, in the policy world, these issues are long recognised and the rhetoric is familiar (CEC European Commission Citation1990, Fudge Citation1995, CEC, Citation1996, WHO Citation2019, UN Citation2017, IPCC Citation2001, WEF Citation2020a). But where, we ask, is the action?

The DAVOS 2020 World Economic Forum acknowledged that, what they termed, ‘Powerful economic, demographic and technological forces, are shaping a new balance of power’ (WEF Citation2020a, p. 6). The result being that the balance of power which was once a ‘given’, in terms of alliance structures and multilateral systems, no longer holds.

While grand statements are sometimes needed, the problem only intensifies, when we don’t factor in that, all too often, policy-making institutions mistake policy for action. It is well recognised that what actually happens in practice is often a long way short of policy intentions (Barrett and Fudge Citation1981). Even when lauded through powerful institutions, innovative action, the anticipated ‘step change’, or a call for a new way of doing things, all seem to be easily thwarted or stalled. How often does policy intention really equate with what happens on the ground?

The problems that need to be addressed are not linear but rather layered, inter-connect and complex. Rarely is there a single solution ‘to be discovered’ and then implemented (Chapman Citation2004). Rather, these problems are better posed in terms of societal problem-based learning seeking solutions that equate to the science of the problem (Bawden Citation1985). Lessons learned from complexity science suggest that adverse urban health outcomes emerge from a poor understanding of the complexity and from not engaging with it in a transdisciplinary, integrated fashion (Gatzweiler et al. Citation2017). While a linear problem may be resolved through rigorous experimentation and technological adoption, we face ‘complex problem situations’ requiring a quite different approach (Healey Citation1999, Innes and Booher Citation2016). With a renewed sense of urgency, borne of the ecological crisis, climate breakdown, unacceptable levels of inequity and now accelerated by COVID-19; we need to re-state the problem. What kinds of action support responsive and rapid transformative whole system learning and action?

Thoughts on urban futures, sustainable development and public health

Urbanism will be a dominant concern of governments, policy-makers, planners, investors, businesses, and communities across the globe in the coming decades. It is projected that by 2050, up to 70% of the global population will live in urban areas. Cities and urban governance are being pushed to the forefront of both human and planetary health. However, whether health and equity will be prioritised as a basis for decision-making is open to doubt (Fudge and Fawkes Citation2017).

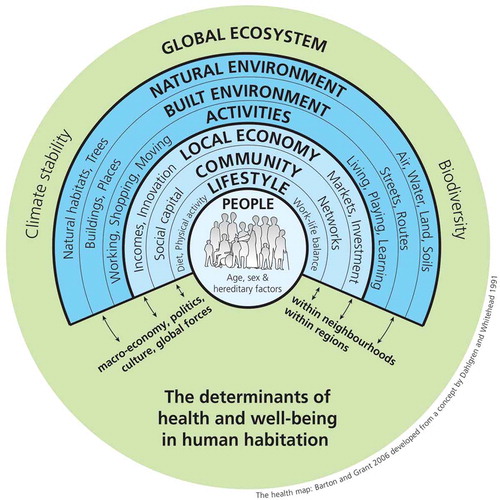

Underlying theories supporting urbanism’s pivotal role can be found in the realm of ecological public health (Lang and Rayner Citation2012), urban health (Rydin et al. Citation2012) and planetary health (Whitmee et al. Citation2015). They are also usefully bonded together into a conceptual tool of the determinants of health in human habitation, ‘The Health Map’, (Barton and Grant Citation2006), building on previous work by Hancock and Perkins (Citation1985) and Dahlgren and Whitehead (Citation1991).

Figure 1. The Health map (Barton and Grant Citation2006).

Therein lies a problem. The knowledge that the way we plan, design and construct human settlements is a key factor in determining both the health of residents and the impact that these habitations have on local and global environments is well established (Barton and Tsourou Citation2000) and has been a major focus of our own work over the last 25 to 30 years. This is now complemented with an increasing number of city-based case studies using systemic actions, in policy areas such as planning, transport, design and construction, as ways of implementing action to support public health and sustainable development (for example, the expansion in many cities of cycling and walking, Brussels, Milan, Bristol). Some of this research has been informed by the evidence base, some has not. Yet as Fudge and Fawkes (Citation2017, p. 1) state, ‘Decisions – made or neglected today – will have impacts over time on human life and ecology, cities and health’.

How can we develop a context for making better decisions? The question is urgent as the decisions needed now are of critical importance and must trigger actions to design and adopt radical processes that are robust and resilient in the context of transformation. Urban contexts are complex and replete with uncertainties; the pace of change is rapid; values and long-range goals are contested; and information is incomplete or embodies various forms of bias.

Can we adopt new forms of policy literacy that can help us make decisions and act?

How do we transfer knowledge from the continuing research and validation behind the ‘sciences’ into the policy arenas and into practice?

What kinds of tools can support us to embed the continually moving edge of leading expertise?

At a conceptual level, approaches to ‘futures thinking’ are increasingly used at all levels and in diverse sectors to support decision-making, especially under conditions characterised by complexity. This introductory article draws upon two large current bodies of work to examine to what extent they display characteristics of the robust tools required to guide a transformation in cities towards sustainable development, population health and health equity. In doing so, we draw on the current preparations for the World Sustainable Built Environment Conference: BEYOND 2020. We also consider the development of a transformational plan for the global built environment sector to support and guide it in meeting the demands of the UN SDGs by 2030 and, similarly, the requirements of the Paris Agreement and actions on biodiversity (Campagnolo et al. Citation2018). Further, we draw upon the considerable work on urban policy and health, associated with the New Urban Agenda, in particular, the international guidance on urban and territorial planning for health brought together in a joint UN-Habitat and WHO collaboration.

Context – where are we now in 2020

Urbanisation and demography

To be able to understand the scale and speed of urbanization, it is essential to draw on the work of the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, available in its ‘World Urbanisation Prospects’ report, published every 4 years, the most recent being 2018, which we have summarised in the following commentary.

Globally, more people live in urban than rural areas, with 55% of the world’s population residing in urban areas in 2018. In 1950, 30% of the world’s population was urban, and by 2050, around 70% is projected to be so. There is wide regional variation in urbanisation with Northern America having 82%, Asia approximately 50% and Africa with 43%.

Growth in the urban population is driven by an overall population increase and the shift of the population from rural to urban living. Together, these two factors are projected to add 2.5 billion to the world’s urban population by 2050, with almost 90% happening in Asia and Africa. Just three countries – India, China and Nigeria – are expected to account for 35% of the growth in the urban population between 2018 and 2050. India is projected to add 416 million urban dwellers, China 255 million and Nigeria 189 million.

Urban areas produce around 85% of the world’s GDP but also produce more than 70% of the global greenhouse gas emissions (UN habitat Citation2018, C40 cities 2019).

Close to half of the world’s urban dwellers reside in settlements with fewer than 500,000 inhabitants, while around one in eight live in 33 megacities with more than 10 million inhabitants. By 2030, the world is projected to have 43 megacities, most of them in developing regions.

In addition to the global urbanization processes, there is a further overlay of change in the demography of the world. Results from recent ‘Population Revisions’ (UN Citation2017) shed new light on the global population ageing process. Here we provide a brief summary of this phenomenon, its regional variation and its implications for transformational planning for sustainable futures. The number of older people (over 65 years) is expected to more than double from 841 million in 2013 to over 2 billion by 2050. Older people are projected to exceed the number of children (0–14 years) for the first time in the 2040 s. Fewer working-age adults are supporting this increasing number of older persons. The ‘old-age support ratio’, the number of persons aged 15–64 years per person aged 65 years or over, has been falling in tandem with population ageing. In the global north, this gives rise to worries about the tax base for pensions and social care and support. It also raises questions around the size and competence of the workforce in many different sectors, including the servicing of urban areas, the role of migration and intergenerational equity. During this year (2020) there will be more people over 65 than children under 5 for the first time in history (UN Citation2020a).

As the world continues to urbanize, sustainable development depends increasingly on the successful management of urban growth, especially in low and lower-middle-income countries, where the most rapid urbanization is expected between now and 2050. Integrated policies to improve the lives of both urban and rural dwellers are needed, strengthening the linkages between urban and rural areas and building on their existing economic, social and environmental connectivity.

Urban growth is closely related to the three dimensions of sustainable development: social, economic, and environmental. Well-managed urbanization, informed by an understanding of population trends over the long run, can help to maximize the benefits of high levels of density while minimizing environmental degradation and other potential adverse impacts of a growing number of city dwellers. To ensure that the benefits of urbanization are shared fairly, policies need to ensure access to infrastructure and social services for all, focusing on the needs of the urban poor and other vulnerable groups for housing, education, health care, decent work and a safe environment (UN World Urbanization Prospects Citation2018).

Increasingly, growing urban agglomerations will be the focus for national economic performance and for local and global environmental performance. Both national ‘urban’ policies and the planning, management and governance at the city level become critical in the realization of sustainable urban futures and increasing national competitiveness in global markets. How policy-making and government can bring these two objectives together and create action on the ground that meets the demands of climate change, implementation of UN SDGs and counter the loss of biodiversity, is one of the key questions for the immediate future (UN Citation2015, Citation2018, SDSN-Bertelsmann Stiftung Citation2017, UN Habitat, Citation2018, Kurz Citation2020). The SDGs as a set are indivisible and support each other. , unpacks the set through the portal of city processes and health, placing them at the heart of the set to reflect the issues raised in this paper.

Trends that will influence the period 2020-2030

In this section, we combine changes and innovations that are likely to be evident in the next 10 years that can profoundly influence the context and processes of home and work life, key urban processes and their management and governance and the transformative potential for industry, cities, health, climate change and the built environment. We humbly recognise that predictions like these are often overtaken by other events or new innovations difficult to even consider and understand at this starting moment.

We have identified the changes and innovations in the form of two tables ( and ). The first is on digital, technological and energy innovations that may become common place and will have a major influence on the future of cities, health and well-being. The second is on the wider processes of urban futures. These two sets of innovations in reality will interact and become more integrated issues influencing urban and health futures.

Table 1. Digital, technological and energy innovations.

Table 2. Innovations in urban and health futures.

From these two tables, we can get a sense of what could be possible in the next 10 years in relation to urban and health futures and meeting the various UN SDGs, the Paris agreement on climate change and actions to combat the loss of biodiversity. As the UK Architects declaration on Climate and biodiversity emergency says:

‘The twin crises of climate breakdown and biodiversity loss are the most serious issue of our time. Buildings and construction play a major part, accounting for nearly 40% of energy-related carbon dioxide emissions whilst also having a significant impact on our natural habitats.’ (UK Architects Citation2019)

They go on to declare that, ‘meeting the needs of our society without breaching the earth’s ecological boundaries will demand a paradigm shift in our behaviour. Together with our clients, we will need to commission and design buildings, cities and infrastructures as indivisible components of a larger, constantly regenerating and self-sustaining system.’ (UK Architects Declare Climate and Biodiversity Emergency Citation2019)

They also argue, as do we, that the research and the technology already exist for us to begin the transformation of city, built environment, urban planning and health futures.

Urbanisation, health and health equity

In a big picture, level population health outcomes are worrying. The WHO asserts that the most important asset of any city is the health of its people, essential for fostering good livelihoods, building a productive workforce, creating resilient and vibrant communities, enabling mobility, promoting social interaction, and protecting vulnerable populations (WHO Citation2016). Here we examine the current state of the health of urban populations and highlight underlying trends.

Even in our modern globalised world, the lack of adequate infrastructure for basic water and sanitation services, a provision intrinsic to urban planning, is linked to major infectious diseases and health inequalities in many cities. Today, some 3 in 10 people worldwide, or 2.1 billion, lack access to safe, readily available water at home, and 6 in 10, or 4.5 billion, lack safely managed sanitation (WHO & UNICEF Citation2017). In 2012, globally 12.6 million people died as a result of living or working in an unhealthy environment, nearly 1 in 4 of total global deaths. Environmental risk factors, such as air, water and soil pollution, chemical exposures, climate breakdown, and ultraviolet radiation, contribute to more than 100 different diseases and injuries (Prüss-Ustün et al. Citation2016). Heading this list are stroke, coronary heart disease, diarrhoea and cancers. The environmentally mediated disease burden tends to be much higher in lower income countries with the exception of certain non-communicable diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases and cancers, where the per capita disease burden is greater in the global north. In a rapidly urbanizing world, a large share of this health burden relates to urban environments that are poorly planned, managed and maintained. Globally, non-communicable diseases themselves account for nearly 70% of deaths each year (WHO & UNDP Citation2016) with rapid and unplanned urbanisation a major factor in an upward trend (key facts are illustrated in the box below, ).

Table 3. Urban malaise.

While evidence of the ‘urban advantage’ suggests that city populations often enjoy better health than their rural counterparts, there are substantial differences in health opportunities and outcomes in urban areas. To put that in perspective, urban data in 79 countries showed that children in the poorest one-fifth of urban households are twice as likely to die before their fifth birthday compared to children in the richest one-fifth. In some places, this ratio is actually greater than five (WHO & UN-Habitat Citation2010a, Citation2010b).

And there is a knock-on and detrimental effect on the cost, and hence availability of health-care services. With more people requiring treatment, for avoidable and preventable disease, health-care costs are growing. Thus, the WHO stated, ‘Achieving a healthy and sustainable environment is a key ingredient for preventing disease and enabling viable health care.’ (WHO Citation2017a, p. 1)

One reaction to such statistics would be to focus on national and international health spending and health access in order to plan for a healthier future. Questions such as, ‘How much is spent per head?’, ‘What percentage of GDP can we afford?’, ‘How is the money distributed?’, ‘Who has access to health care?’, and ‘How do the poorest and most vulnerable get more access to health care services?’ However, influenced by a combination of language, lack of understanding, political expediency and sectorial barriers, the dominant focus has been to generate questions related to curing illness and supporting ill people when faced with these stark statistics.

Recent analysis suggests policymakers should pay more attention to broader social and education spending rather than simply health spending (CPP Citation2019). This echoes the WHO Ottawa Charter (WHO Citation1986) but some 30 years on. But we cannot find any national health policy that is based subsequent action on the Ottawa Charter’s core principal that, ‘health promotion is not just the responsibility of the health sector’? The questions needed to trigger transformative action in this sector need to begin by recognising the paradox of the importance of non-health spending for population health. It is essential to again re-think health policy, shifting away from a narrow definition and consider health in all policies and places (CPP Citation2019, Marmot Citation2020).

Case study 1: a transformational plan for the global built environment sector

Background

2015 was a landmark year for multi-lateral cooperation and agreement on international issues pertaining to sustainability and climate change. Both, the Paris Agreement on Climate Change and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (along with its 17 Sustainable Development Goals – SDGs at its core) were adopted by all the UN member states. The 17 SDGs aim at the eradication of deprivation and span all the material dimensions of life – society, economy and the environment – reflecting a shared consensus among nations to prosper sustainably. The proposal to develop SDGs, building upon the earlier Millennium Development Goals for reducing extreme poverty, was first taken up in the 2012 United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The SDGs were eventually adopted in 2015, at the UN Sustainable Development Summit, as the culmination of negotiations following the post-2015 development agenda (United Nations Citation2020a).

Problem description

We are still not yet close to achieving the 169 targets, as identified under the 17 goals and which could be verified from independent data sources (Our World in Data Citation2020). The 2019 Global Sustainable Development Report identified that not only do countries need to exploit knowledge of how interlinked human-social-environmental systems work, but they also need to disseminate the knowledge about it (Nilsson and Stevance Citation2016). The report suggested six ‘entry-points’, representing systems, which would together to inch us closer to the SDGs (Secretary-General Citation2019). The idea is to identify and plan those action points that can trigger a positive impact, spanning a wide breadth of systems, advancing towards the SDGs. A survey by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) revealed that while SDGs are seen as a strategic opportunity, there is still a lack of understanding of a business case for SDGs within their own operations (WBCSD & DNV GL Citation2018). Implementing the SDGs and realizing their intended impact requires that nations meaningfully integrate them into their plans and policies. An implementation plan is required that is developed in a bespoke way to accommodate different economic sectors, geographical regions and takes account of their differences. It also needs to involve and engage all relevant stakeholders including industry, civil society and academia. Additionally, the institutional and administrative infrastructure – legal framework, governing agencies, supporting policies – is needed to provide for a robust foundation. The built environment has been identified as one of the most relevant sectors to achieve the UN SDGs.

The built environment

The built environment represents up to 70% of global wealth (with urban areas producing around 85%), generating 10% of the total GDP and providing 7% of global employment (Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors Citation2019). The sector causes substantial environmental and social impact through land development and management of built infrastructure. It is expected, that with the current trends, cities will host approximately 70% of the world’s population and produce 85% of the economic output by 2050. This growth will come at a cost, manifest in the form of poor air quality, water scarcity, emissions, raw material consumption of up to 90 billion tons per year, and natural habitat destruction (Secretary-General Citation2019).

The construction industry can have a high impact on a few specific goals such as SDG 11 (sustainable cities & communities), 9 (Infrastructure & Innovation) and 7 (affordable & clean energy) but can also influence other goals (World Green Building Council Citation2020). Research has found that 74 of the 169 targets of the agenda (44%) were found to be dependent on construction and real estate activities – of which 29 targets (17%) are directly dependent and 45 targets (27%) are indirectly dependent (Goubran Citation2019). There is also a body of research building upon integrating SDGs into the building design process (Goubran and Cucuzzella Citation2019). There is an entire guide to show how the different SDGs interact with the built environments, called ‘An architecture guide to the UN17 SDGs (Mossin et al. Citation2018). Further clarity and guidance are needed to help all actors involved in the global built environment sector to overcome the enormity of the issues through a transformational program. The programme should commence in 2020 with a view to achieving the UN SDGs by 2030.

Previous research has shown the difficulties in translating sustainability from theory to practice in several research projects (Wallbaum et al. Citation2011, Brunklaus et al. Citation2009, Citation2019, Norling Mjörnell et al. Citation2019). Chalmers University, Gothenburg, and RISE, which were co-hosting the BEYOND 2020 conference in June 2020 (now postponed to November 2020) are working on the same problems towards the conference (World Sustainable Built Environment Conference Citation2020). Chalmers and RISE will build upon the efforts thus invested as well as insights and knowledge gained during the conference and use it as a basis to be developed further in the post-conference period.

Operationalizing the SDGs Voluntary National Review (VNR) mechanism was established to review the progress of nations towards SDGs, and to facilitate knowledge sharing of best practices (United Nations Citation2020b). A total of 213 VNRs have been submitted so far, with many explicitly sharing domestic measures to link SDGs to national budgets. A common theme in all the VNRs is that the countries have involved personnel from multiple sectors and level of authority. They include ministries from across the sectors, cabinet ministers, civil society groups and NGOs. This is aligned with how sustainability thinking is translated at the grassroot level as well – by planning and engaging stakeholders, backed by institutional support. The VNRs also had descriptions of how the SDGs and their targets were being transposed to national-level policies and plans of the respective governments. Or how national issues and priorities of a strategic nature were being correlated with the relevant SDGs. Eventually, the reports dealt with how individual SDGs were being met in the countries, and what were the weaknesses and strengths in this pursuit.

Countries have also been taking the support of knowledge advisory and research organizations to help plan for SDGs, while many organizations have come up with knowledge and data tools to facilitate decision-making. For example, in order to assist countries in identifying intervention areas that could catalyze the efforts to meet SDGs, UNDP has come up with its SDG, ‘Accelerator and Bottleneck Assessment’ tool (ABA). This assists countries in identifying ‘accelerators’ that can trigger positive multiplier effects across the SDGs and targets. It also helps identify solutions to bottlenecks that impede the optimal performance of the interventions that enable the identified accelerators (United Nations Development Programme Citation2017). Previously, during the 2000–2015 MDG phase, UNDP had developed the MDG Acceleration Framework (MAF) (United Nations Development Programme, u.d.).

The Division for Sustainable Development Goals in the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA) is also engaged in providing capacity building support, evaluating progress and thematic support (United Nations Citation2020b). The OECD is assisting regional and local leaders in developing policies and action plans to localize the SDGs (OECD Citation2020). For businesses, there is a guide to implementing SDGs, called SDG compass and IISD has been creating a web tool and platform for SDG related data and publications (International Institute for Sustainable Development Citation2020). Additionally, stakeholders from the business and investment world have been coming forward to support the SDGs and even multi-lateral financing institutions taking an active lead (United Nations Global Compact Citation2020, Asian Development Bank Citation2020). There is even a UN established SDF fund to finance and pilot integrated approaches to sustainable development in specific sectoral areas and advance the Agenda 2030 (SDGF Citation2020).

Description of the project

The built environment is a very relevant sector for achieving UN SDGs due to its global importance. It aids economic development, job creation, and provides the society with needed infrastructure in a highly urbanized world. At the same time, it assumes a greater significance owing to the environmental impact it creates, either through consumption of natural materials, energy or the creation of greenhouse gas emissions. Today, the UN SDGs with their 169 underlying targets describe a pathway towards sustainable development without pointing out specifically the sectorial responsibilities. The project has the long-term goal to provide clear guidance to the global built environment sector to achieve the UN SDGs by 2030. To achieve this goal, the project is divided into two phases, the first phase is called ‘initialization phase’ and the second the ‘global implementation phase’. Our project addresses only the ‘initialisation phase’ from 2020 to 2024 but will prepare the ‘global implementation phase’ that will follow between 2025 and 2030. The ‘initialisation phase’ will terminate with the introduction of an international as well as a Swedish, National Transformational Plan for the built environment. Both will be the result of a combination of mixed methods research (qualitative and quantitative) and their application on different geographies. This will allow taking into consideration regional strengths and varying conditions, e.g. socio-economic, climatic, cultural, etc., and provide clear sector-specific requirements. This is very likely to reveal a different level of importance for the different UN SDGs and underlying targets in the different regions of the world.

At the World Sustainable Built Environment (WSBE) conference BEYOND 2020 (https://beyond2020.se), the organisers have already introduced the idea of sector-specific relevant UN SDGs. The conference organisers and the leaders of this project put the UN SDG 11 ‘Sustainable cities and communities’ in the centre as an overarching aim that the built environment is striving for and selected 10 out of the remaining 16 UN SDGs (https://beyond2020.se/conference/un-sdgs-key-topics/) that are considered most important to realise UN SDG 11. The selection was based on interviews and discussions with relevant stakeholders in the sector, as well as inputs from the Sustainable Built Environment conference series co-owners (such as IISBE, CIB, UN Environment, FIDIC) (https://beyond2020.se/home/sbe-conference-series/) and the International Advisory Board of BEYOND 2020, which includes UN Habitat, UN Global Compact, CIB and ICLEI (https://beyond2020.se/home/international-advisory-board/) (World Sustainable Built Environment Conference Citation2020).

During the postponed WSBE conference, we will have the opportunity to discuss this approach further, which will serve as a valuable source of information and point of departure at the very beginning of our project. Hence, the project will end with an operational plan for the global built environment sector to achieve the UN SDGs for the built environment and a set of recommendations for different stakeholder groups on necessary measures that would be needed to achieve the UN SDGs by 2030.

The Transformational Plan is the starting point for a process of change commencing June 2020 but will then be monitored and reviewed over the next 10 years. We are proposing that the Transformational Plan will guide the built environment sector in its transformation and change over the next 10 years. For accountability and responsibility, we suggest that the WSBE conferences in 2023, 2026 and 2029 continue to monitor and review progress on the implementation of the Transformational Plan and the UN SDGs. In this way, the WSBE conferences take on a new relevance as the ‘responsible place holders’ for the implementation of the UN SDGs by the global built environment sector.

Case study 2: international guidance on urban and territorial planning for health

In tackling the growing burdens of disease and health inequality, the risks and challenges to health arising from urbanisation need to be addressed (Rydin et al. Citation2012). UN-Habitat uses the term ‘urban and territorial planning’ to refer not just to regulations but the complex socio-political phenomenon also often called ‘spatial planning’ (Ernste Citation2012, UN-Habitat Citation2015) that influences investments and decisions, or the lack thereof, which shape places. Urban and territorial planning is a critical enabler, or disabler, of population health and health equity and has a central role in the prevention of disease. Urban policy influences the air we breathe, the quality of space we use, the water we drink, the way we move, our access to food, and also our ability to treat ill-health – through reducing the burden of disease and thus helping to ensure better access to health care. Planning decisions can exacerbate major health risks for the population, or they can foster healthier environments, behaviours and create healthier more equitable and resilient societies.

It is possible to influence location, spatial pattern, and local design of place-based features and amenities in the built environment for the benefit, or dis-benefit of health and health equity (Barton Citation2009). This is applicable to all countries: high-income countries, low- and middle-income countries and also (but not through formal planning policy) to those living in informal settlements.

UN-Habitat recognises both the importance of planning for human settlements and the failure to meet many needs of urban residents, especially those in the rapidly growing and predominantly poor cities of the global south (UN-Habitat Citation2009). Coining the term ‘urban and territorial planning’, UN-Habitat has published international guidance aimed at national and municipal government decision-makers and others, including civil society and built environment professionals (UN-Habitat Citation2015). This initiative started an ongoing programme of influence (UN-Habitat Citation2017, Citation2018) that was accelerated by the New Urban Agenda process (Habitat III Citation2017). In parallel, in the run up to Habitat III, the World Health Organization published a powerful statement that health was ‘the pulse of the new urban agenda’ (WHO Citation2016 – NUA).

Continuing their ongoing and joint focus on urban health [e.g. Global Report on Urban Health: Equitable, Healthier Cities for Sustainable Development (WHO/UN-Habitat Citation2010a)], the two agencies have sought, post Habitat III, to bring a transformational change to support population health through urban planning. Recently, they have developed a sourcebook for urban leaders, health and planning professionals for integrating health within urban and territorial planning (World Health Organization and UN-Habitat Citation2020). The intention is to provide a strong provocation for centring population health, planetary health and health equity in all aspects of urban spatial activity.

An initial scoping led to two tenets that then guided the project. Firstly that health is not just an important ‘output’ of planning, but rather a vital ‘input’ to the process. Public health can bring a treasury of skills, evidence and community-based resources to planning. As a profession, it has a deeply ethical population-based focus with skills of tough political advocacy. To reap these benefits public health actors and decision-makers need to be more closely involved in all aspects of urban and territorial planning. Secondly that there is already a plethora of guidance on how to put health into urban planning. The project needed to build on these sources, not add yet another. It accrued a database with over 400 records of different kinds of resources, belonging to several broad categories such as analytic tool for quantitative analysis, briefings and design guides, comprehensive subject-specific evidence bases, trainings, networks and web-resources.

Yet despite so many resources, and long-standing recognition of concepts such as ‘healthy urban planning’ (Barton and Tsourou Citation2000) and the WHO healthy cities initiative, as well as pockets of innovation. A question remained as to why so little systemic action? This lead to the development of the concept of ‘entry points’. The ‘sourcebook’ attempted to provide a series of ‘entry points’ for actors and decision-makers, outlining a framework of when, why and how to use the many kinds of guidance that are available now and will become available in the future. It identified the widest possible opportunities for health to be brought into planning, both as an input and as an output, across formal and informal planning processes that happen in all countries, high, middle and low income.

It argued that a good entry point is one that:

Resonates with all actors and decision-makers governmental, professional and civil society to collaborate in identifying alignment of purpose with exiting plans and objectives.

Results in co-benefits actions across the widest range of sustainable development goals with climate and equity as core issues and ranging from eco-system services to economic interests.

Provides access to a range of different types of interventions and techniques that can embed health in multi-level projects and processes such, as, urban policy or spatial frameworks, area-based strategies and programs, and transport, design and governance.

Such entry points can be categorized by settings, outcomes, conceptual principles or approaches and sectoral actions ().

Table 4. Examples from the many entry points for health to engage as an input and outcome in urban design and territorial planning. This list is not exhaustive but serves to indicate the value of the concept (World Health Organization and UN-Habitat, Citation2020).

Too often the planning system throws up what are seen as barriers to engagement, such as, the wrong type of participation, an inadmissible evidence base, a closed window for consultation, the argument not correctly framed, a weak planning system. Through this initiative, the WHO and UN-Habitat encourage participants to overcome such barriers and instead find multiple entry points that can have a systemic influence on what makes places healthy.

The next step is to use the sourcebook to support training in these approaches to embed health and emphasise its importance.

The purpose of the intervention was never to provide a prescription of what to do in any one situation. Rather, it is to open up an ongoing health-based dialogue about urban settlements. The intention is to provide and maintain a transformative window through which spatial planning and public health can collaborate again, as they have previously (Hebbert Citation1999). With disease prevention and health equity as its pulse, urban and territorial planning must become the heart of communicable and non-communicable disease reduction whilst minimising our footprint on the planet.

Transforming city and health futures: discussion

This introductory article for the special issue has been written in the period February to May 2020 at a time when the coronavirus crisis rapidly developed into a global pandemic. As a result of this public health emergency, governments around the world have developed a range of strategic policy and action responses. The business as usual rhetoric has not been possible and the interventions have had to be urgent, comprehensive and extreme in most cases. Public health and the safeguarding of the most vulnerable have been prioritized over the economy, markets and economic futures initially. However, we are witnessing this balance shifting somewhat as the ‘lockdown policies’ are loosened.

This continuing context has influenced our writing and indeed at times our focus and concentration. Nevertheless, it has also proved to be a very enlightening and intriguing opportunity to witness and reflect upon governmental responses to emergencies. We have seen and continue to assess the varying strategies for handling this crisis, and for many in the global north, the exposure of the effects of austerity and its impact on equity. It has also shone a very positive light on those involved in the health-care services and public health at all levels plus the reaction of communities and civic volunteerism to support the most vulnerable.

As a result of the rapid policy shifts, the radical change and locking down of normal life, we are able to also witness positive changes to the environment and air quality (Venice waterways, NO2 maps across Europe, Bristol’s One City Plan, Guardian 2020). As we stand back from this all-encompassing virus and the global responses, we cannot help but wonder optimistically whether this preconditions us all to the scale of changes that will be required in relation to the Paris Agreement on climate, the implementation of the UN SDGs and the actions needed in relation to biodiversity. Or more pessimistically, whether it prefigures the reactive and challenging actions that will be required in future crises if we fail to act decisively.

Looking to the future, with the pandemic receding, will we revert to pre-coronavirus times or will this experience lead to new ways of organizing society and transforming our futures? Given what has been achieved, what policy sets are now more possible to combat different forms of emergency, including those arising from climate breakdown? Can other responses be as swift and decisive leading to transformative futures? It has become clear that ‘austerity’ was a political choice and not an inevitable global economic norm, and it now seems possible to rethink the economic future in the light of examples of more socialized economic strategies. As Michael Marmot (Guardian Citation2020) suggests, should we not be placing health equity at the heart of all policymaking? To do so, would give rise to better environmental, social and healthcare policy and, we would argue, better urban policy.

As the world moves cautiously from ‘lockdown’ to a different ‘normality’, a whole range of issues and scenarios present themselves for discussion. In this article, we raise a number of these issues to strategically focus on an agenda for research, policy development and practice to stimulate readers and colleagues to develop further. Our two case studies and reflections have highlighted, in particular, questions about:

The transformation of governance and business models.

New roles for central, regional and local governments.

Collaboration, multi-disciplinarity and innovation across sectors within strategic frameworks.

Transformation and the question of time, sequencing and effective step change.

The need for in-depth work on the nature of and response to global ‘tipping points’.

Further exploration into ‘entry points’ as a means of achieving successful interventions.

The need for new forms of leadership, imagination and strategic direction that prefigure ‘joined-up futures’.

Economic policies and priorities that anticipate and prepare for further pandemics and global change in relation to climate and environment.

The roles of global institutions and how they might be transformed for improved effectiveness.

The nature of aid and development and the real practice of ‘leaving no one behind’

Why are we focusing on transformational change?

On the one hand, it is a response to the clear and large gap between policy and required change and action on the ground. In discussing this, we can refer to the large literature and research carried out in the period of ‘implementation studies’ conducted from the 1970s to the early 1990s. We do not intend to rehearse this work here but readers who wish to go into this in more depth can do so through the following key references (Dror Citation1968, Citation1971, Pressman and Wildavsky Citation1973, Dunsire Citation1978, Hjern and Porter Citation1980, Barrett and Fudge Citation1981). Suffice it to say that all too often from these investigations, policy-making institutions often assumed policy once expressed meant action. Whereas what actually happens in practice may appear, from the policymaker’s perspective, to be a long way short of the original policy intentions (Barrett and Fudge Citation1981). Often the issues and problems being dealt with are not linear but complex. There is no simple solution to be ‘discovered’ and then simply implemented. Hence, the thinking and strategic change to meet complex issues such as climate breakdown or the implementation of the UN SDGs requires a different approach and at a minimum one that matches the nature of the complexity.

In the first case study, on the implementation of the UN SDGs by the global built environment sector, we find that whilst there are numerous policies, objectives and exhortations developed by the UN and others, there is still a large ‘gap’ between the hope that these objectives will be universally adopted and the reality of a fragmented response. There are added difficulties in challenging and changing everyday practice collectively from very different actors and also changing their overall business. The ‘gap’ remains and in some ways is used as a ‘defence against action and change’. This may often be expressed as perceived lack of clarity and urgency about what needs to happen, in some cases, such a ‘defence’ is used to mask an opposition to any form of change in the foreseeable future. It would appear that the collective intellectual understanding has not been reached and the anxiety, or competitiveness, of not meeting the new policy expectations has not developed sufficiently to reach a tipping point for change. What then is required for industry and government to accept that they need to disrupt and change current practices and move to a wider transformation? Wallbaum and Fudge (Citation2020) argue for the need for what they call ‘bridging communication and learning capability’, so that actors can be supported in transforming their way of working in association with others and through these start to meet and implement the objectives of, for example, the UN SDGs. We see an attempt at this by two major global institutional actors, in terms of urban development for planetary and human health, our second case study. At the same time, there needs to be more transparency on how different parts of the sector are performing in relation to the whole. There is always a risk that ‘policy’ and political statements may become a substitute for action or ‘symbols of action’ without providing the support or mechanisms for the implementation of the policy intentions.

What then is transformational change and the need for transformational guidance and support? There exists already a wide literature on change and managing change that draws on a number of disciplines, including management studies, organizational studies, behavioural change, psychotherapy, innovation studies, social movements, political movements. We do not intend to rehearse these here but we are interested in focusing on the concept of transformation particularly in relation to cities and health.

The concept of transformation has been developed from a number of sources. The key research through the Dutch research centre DRIFT operates in the broad area of system innovation and sustainability transition studies (Grin et al. Citation2010, Loorbach et al. Citation2017, Kohler et al. Citation2019). They define transitions as, ‘long term processes of radical and structural change at the level of societal systems’ such as different sectors, cities, regions or indeed nation-states. Grin et al define a sustainability transition as a ‘radical transformation towards a sustainable society, as a response to a number of persistent problems confronting contemporary modern societies’ (Grin et al. Citation2010).

In the field of transition studies, DRIFT is acknowledged for its research on transition management through its approach that includes visioning, learning and experimentation (Loorbach Citation2010, Loorbach et al. Citation2017). They include in their approach ‘economic, political and cultural perspectives’ in recognizing the significance of ‘social challenges’ within the overall sustainability goals. Similarly, there is also a body of work from researchers that focuses more on the social understanding of the behaviour, detail and sequencing of change. This work is perhaps best exemplified by Shove et al. (Citation2012) and the expansion of this globally. There is also a substantial body of work from Simon Guy and Simon Marvin that has taken place at in the UK that focuses on transitions and cities (Guy et al. Citation2010, Horne and Fudge Citation2014, Fudge and Fien Citation2015, Hodson and Marvin Citation2016, Stissing Jensen et al. Citation2018) and the perennially live issue of how to build out from islands of innovation (Wallner et al. Citation1996).

These bodies of research, based on practice change in the real world, provide insights into methodologies, approaches and conceptual frameworks. Given our focus on the transformation of cities and health, what then should we be thinking about in relation to a research and practice agenda that would guide us in this endeavour?

How transitions can be accelerated and which policy mix and tools might influence the process positively.

How to encourage the decline of existing non-sustainable systems.

Engaging with the politics of transitions.

How to use the agency of actors involved in transition processes.

How to diffuse ‘green innovations’ and achieve ‘take up’ more widely.

How to move beyond ‘islands of innovation’ and achieve scale.

How to manage uneven dimensions of transition as a result of geography, cultural contexts and stages of development.

These deep and complex issues will form part of the work to be developed in the preparation of the Transformational Plan for the Global Built Environment Sector commencing later this year on how it will meet the UN SDGs by 2030.

Another dilemma is the temporal aspects of change. Alongside the handling of short, medium and long-term futures, organisations need to hold these aspects together in their planning and action processes. Organisations have to develop a capability of operating in the ‘here and now’ while scanning the future in terms of a foresight competence. (Barrett and Fudge Citation1981, Sharpeet al. Citation2016, Fawkes and Fudge Citation2017)

There are a number of examples that demonstrate different aspects of the issue of time. In the case of the European Sustainable Cities Project 1991–2005, which at its peak, around year 2000, involved over 2500 towns and cities in Europe. Whilst on one level long-term change was achieved, other priorities took over, challenging or diluting the original intentions and achievements. Is there then a fixed period for any new innovations to run their course? Similarly, at times when foresight can be just what is required, the organization fails to ‘hear’ or ‘respond’ to these demands as they are perceived as being too far away from current reality in terms of practice norms and political pressures. How can organisations balance this requirement to be both scanning the future and handling the everyday, holding both scenarios together in some middle ground planning/policy intelligence and imagination? Do we need to revisit, explore and develop the work of Etzioni (Citation1967, Citation1968) on mixed scanning as a philosophical, behavioural and practical approach in transforming futures?

As we move on to commence the work on transformation and you, the reader, explore the articles in this special issue of Cities & Health, what seem to be the key questions we need to take with us on these journeys so that we may be able to take the next steps actively? For us they include:

How do you operationalize transformation?

What methodologies and tools can be employed to achieve transformations?

How can one operate at speed and scale to actively make a difference?

Who are the key actors that need to be involved in transformational partnerships?

What are the implications for policy, action and governance processes?

What are the implications for existing and future business models, economic models and markets and how do you support these changes?

What are the key changes we need to make personally, professionally, organizationally and politically?

How is the transformational project best communicated, such that it can gain legitimacy and support to become a movement for change?

In the 21st century, whilst residing within a major pandemic globally and with more wicked issues affecting us still to be addressed – climate breakdown, implementing the UN SDGs, actions to tackle biodiversity and supporting the health of a growing urban population – what fundamental rethinking and imagination are required?

Our thinking is that this is an important moment and we need to understand the significance of this at both the philosophical and political levels as we move to action. Anthony Painter in a recent article points out that ‘Habermas was concerned with the increasing invasion and colonisation of what he describes as the “lifeworld” by the instrumental rationality of “the system”’ (RSA Journal Citation2019). He elaborates further by pointing out that ‘the system’ has two components: power from administrative authority the domain of the state and money from the markets and those that make up the market. Habermas argued that the ‘lifeworld is where human interaction is sacrosanct’ and Painter went further to say ‘it is where families, community, friendship, creativity, civic life, art, culture and our personal relationship with nature are to be found. It is a place of ethics, human connection and meaning.’

In the circumstances we face, the pandemic, the post-pandemic economy and climate change, it can be argued that all sorts of organisations and institutions need to find new means of alignment with our goals, values and passions, our ‘lifeworld’. This applies, we think, to international institutions as much as it does to public services and to private businesses. Painter argues that ‘the system spreads further and further into the lifeworld’ whereas ‘it should be the opposite; we should be expanding the humanistic lifeworld further into the system and all of its components’.

Reflecting on these thoughts can transformative actions deliver what is required through the existing albeit adjusted political ideologies? Or, are there severe limits to what can be achieved? What are these main barriers and limits that we will need to address and how difficult are they to overcome? Or do these demands require a more radical and fundamental rethinking of the nature of capitalism, the dominant economic model of growth, consumption and our way of life? Can we transform our own thinking and our futures following our experience and learning locally and globally from the pandemic such that we can rethink the recovery, the economy and the relationship with the natural world?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Colin Fudge

Colin Fudge is Professor of Urban Futures and Design at Chalmers University, Sweden; Senior Adviser to the EU Climate KIC; Global Adviser for the UN Global Compact: Cities Program and for UN Habitat and is King Carl Gustav XVI, Royal Professor of Environmental Science, Sweden. Colin works on urban futures and design, sustainable development, urban health and urban design He is Emeritus Professor in RMIT, Australia and in Bristol, U.K. He has worked in universities at President and Vice-President levels in Europe and Australia and at Deputy Secretary and Director levels in government and cities in the UK and Australia. From 1993 to 2005, he was President of the EU Urban Environment Expert Group for the European Commission.

Marcus Grant

Marcus Grant is Editor-in-Chief of Cities & Health and former deputy director of the World Health Organisation’s Collaborating Centre for Healthy Cities. With a background in ecological systems and urbanism, he is a practitioner-scholar working in healthy urban planning, healthy place-making and planetary health. He is an expert advisor to the WHO and UN-Habitat, a contributor to “Health as the Pulse of the New Urban Agenda’ and author of the WHO/UN Sourcebook: Integrating health into urban and territorial planning (2020). Marcus is a Fellow of the Faculty of Public Health, a member of the Landscape Institute and is based in Bristol, England.

Holger Wallbaum

Holger Wallbaum is a professor in sustainable building at the Division of Building Technology, research group Sustainable Building, and in the Area of advance Building Futures. Holger works within sustainable building on concepts, tools and strategies to enhance the sustainability performance of construction materials, building products, buildings as well as entire cities. His main research interests are related to ecological and economic life cycle assessment of construction materials, buildings and infrastructures, sustainability assessment tools for buildings, social-cultural and climate adapted design concepts, the refurbishment of the building stock as well as dynamic building stock modelling and its visualization.

References

- Asian Development Bank, 2020. ADB and the sustainable development goals. [Online] Available from: https://www.adb.org/site/sdg/main

- Barrett, S. and Fudge, C., 1981. Policy and action: essays on the implementation of public policy. London: Methuen.

- Barton, H., 2009. Land use planning and health and well-being. Land use policy, 26, S115–S123. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2009.09.008

- Barton, H. and Grant, M., 2006. A health map for the local human habitat. The journal for the royal society for the promotion of health, 126 (6), 252–253. 1466-4240.

- Barton, H. and Tsourou, C., 2000. Healthy urban planning. London: SPON.

- Bawden, R.J., 1985. Problem-based learning: an Australian perspective. In: D. Boud, ed.. Problem based learning in education for the professions. Sydney: HERDSA, 43–57.

- Brunklaus, B. and Sala, S., 2019. Designing sustainable lifestyles - from societal structure to personal choices. LCM conference 1-4 September 2019 in Poznan/Polen. Theme 4 Sustainable Markets. Session chair ID 4.7.

- Brunklaus, B., Tove, M., and Baumann, H., 2009. Managing stakeholders or the environment? The challenge of relating indicators in practice. Corporate social responsibility and environmental management, 16 (1), 27–37.

- Campagnolo, L., et al., 2018. supporting the UN SDGs transition: methodology for sustainability assessment and current worldwide ranking, Economics. Vol. 12. Kiel: Kiel Institute for the World Economy.

- Chapman, J., 2004. System failure why governments must learn to think differently. Demos. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2003.11.002

- CPP, 2019. Beyond the NHS: addressing the root causes of poor health. London: Centre for Progressive Policy.

- Dahlgren, G. and Whitehead, M., 1991. “The main determinants of health” model, version accessible. In: G. Dahlgren and M. Whitehead, eds. European strategies for tackling social inequities in health: levelling up Part 2. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/103824/E89384.pdf

- Dror, Y., 1968. Public policy making re-examined. Scranton, Penn.: Chandler.

- Dror, Y., 1971. Design for Policy sciences. New York: Elsevier.

- Dunsire, A., 1978. Implementation in a bureaucracy: the execution process, I. Oxford: Martin Robertson.

- Ernste, H., 2012. Framing cultures of spatial planning. Planning practice & research, 27 (1), 87–101. doi:10.1080/02697459.2012.661194

- Etzioni, A., 1967. Mixed scanning: a third approach to decision making. Public administration review, 27 (5), 385–392.

- Etzioni, A., 1968. The active society. New York: Free Press.

- European Commission, 1990. Green paper on the urban environment. Brussels: EU.

- European Commission, 1996. European sustainable cities report. Brussels: Expert Group on the Urban Environment.

- European Commission, 2018. ESPAS. Available from: europa.eu

- Fudge, C., 1995. International healthy and ecological cities congress: ‘Our City, our Future’, Rapporteurs report. Copenhagen: WHO.

- Fudge, C. and Fawkes, S., 2017. Science meets imagination – cities and health in the twenty-first century. Cities & health, 1 (2), 101–106. doi:10.1080/23748834.2018.1462610

- Fudge, C. and Fien, J., 2015. Multifaceted engagement for urban sustainable futures in Melbourne and Southeast Asia in Merrett and Kain eds co-producing knowledge for sustainable cities. London: Routledge.

- Gatzweiler, F.W., et al., 2017. Lessons from complexity science for urban health and well-being. Cities & health, 1 (2), 210–223. doi:10.1080/23748834.2018.1448551

- Goubran, S., 2019. On the role of construction in achieving the SDGs. Journal of sustainability research, 1, e190010. Available from: http://doi.org/10.20300/jsr20190010

- Goubran, S. and Cucuzzella, C., 2019. Integrating the sustainable development goals in building projects. Journal of sustainability research. GRI, UNGC & WBCSD, 2015. SDG Compass: The guide for business action on SDGs, S.l.: GRI, UNGC & WBCSD.

- Grant, M., et al., 2017. Cities and health: an evolving global conversation. Cities & health, 1 (1), 1–9. doi:10.1080/23748834.2017.1316025

- Grin, J., Rotmans, J., and Schot, J., 2010. Transitions towards sustainable development. UK: Routledge.

- Guy, S., et al., 2010. shaping urban infrastructures, earthscan. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Habitat III, 2017. New urban agenda. Quito: UN.

- Hancock, T. and Perkins, F., 1985. The mandala of health. Health education, 24 (1), 8–10.

- Healey, P., 1999. Institutionalist analysis, communicative planning, and shaping places. Journal of planning education and research, 19 (2), 111–121. doi:10.1177/0739456X9901900201

- 2014. Health policy brief: the relative contribution of multiple determinants to health outcomes,” Health affairs, 21 August. Available from: www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/

- Hebbert, M., 1999. A city in good shape: town planning and public health. Town planning review, 70 (4), 433. doi:10.3828/tpr.70.4.n06575ru36054542

- Hjern, B. and Porter, D.O., 1980. Implementation structure: a new unit of administrative analysis. Unpublished mimeo, International Institute of Management Berlin. Vienna: Institute for Advanced Studies.

- Hodson, and Marvin, S., 2016. Cities, regions and shaping technological transitions. Open University, June 2006.

- Horne, R. and Fudge, C., 2014. International perspectives: low carbon urban Australia in a time of transition. In: C. Miller and L. Orchard, eds. Australian public policy: progressive ideas in the neoliberal ascendancy. Bristol: Bristol University Press and University of Chicago Press, 279–298.

- Innes, J.E. and Booher, D.E., 2016. Collaborative rationality as a strategy for working with wicked problems. Landscape and urban planning, 154, 8–10. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.03.016

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2001. Third assessment report from the IPCC, summary for policymakers, final. UNEP, United Nations

- International Institute for Sustainable Development, 2020. Our focus on the sustainable development goals. [Online].

- Köhler, J., et al., 2019. An agenda for sustainability transitions research: state of the art and future directions. Environmental innovation and societal transitions 31, 1–32.

- Kurz, R., 2020. UN SDGs: disruptive for companies and for universities? In: S. Idowu, R. Schmidpeter, and L. Zu, eds. The future of the UN SDGs CSR sustainability, ethics and governance. Chay: Springer, 279–290.

- Lang, T. and Rayner, G., 2012. Ecological public health: the 21st century’s big idea? An essay by Tim Lang and Geof Rayner. BMJ, 345, e5466. doi:10.1136/bmj.e5466

- Loorbach, D., 2010. Transition Management for sustainable development. Wiley online, Governance, 23 (1), 161–183.

- Loorbach, D., et al., (Eds), 2017. Governance of urban sustainability transitions. New York: Springer.

- Loorbach, D., Frantzeskaki, N., and Avelino, F., 2017. sustainability transitions research: transforming science and practice for societal change. Annual review of environment and resources, 42 (1), 599–626. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-102014-021340

- Marmot, M. (2020) from article in guardian newspaper May McKinsey private communication, London.

- MEA, 2005. Millennium ecosystem assessment. Ecosystems and human well-being: current state and trends. Washington, DC, États-Unis: World Resources Institute. Available from https://sustainable-development-goals.iisd.org/

- Mossin, N., et al., 2018. An architecture guide to the UN 17 sustainable development goals. Copenhagen: KADK.

- Nieuwhausen, M. and Khries, H., Eds. 2019. Integrating human health into urban and transport planning. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Nilsson, M. and Stevance, A.-S., 2016. Understanding how the SDGs interact with each other is key to their success. [Online] Available from: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/07/understanding-interactions-is-key-to-making-the-sdgs-a-success/

- Norling Mjörnell, K., Femenias, P., and Annadotter, K., 2019. Renovation strategies for multi-residential buildings from the record years in Sweden – profit-driven or socioeconomically responsible? Sustainability, 11 (24), P6988.

- OECD, 2020. Achieving the SDGs in cities and regions. [Online]. Available from: http://www.oecd.org/about/impact/achievingthesdgsincitiesandregions.htm [Accessed 1 February 2020

- Our World in Data, 2020. SDG tracker. [Online]. Available from: https://sdg-tracker.org/ [Accessed 1 February 2020

- Painter, A., 2019. A crisis of legitimacy? RSA journal (3).

- Pressman, J. and Wildavsky, A., 1973. Implementation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Prüss-Ustün, A., et al., 2016. Preventing disease through healthy environments: a global assessment of the burden of disease from environmental risks. Bonn: WHO.

- Rockström, J., et al., 2009. A safe operating space for humanity Identifying. Nature, 461 (September), 472–475. doi:10.1038/461472a

- Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, 2019. Implementing the UN sustainable development goals. London: Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors.

- Rydin, Y., et al., 2012. Shaping cities for health: complexity and the planning of urban environments in the 21st century. The Lancet, 379 (9831), 2079–2108. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60435-8

- SDGF, 2020. Sustainable development goals fund. [Online]. Available from: https://www.sdgfund.org/

- SDSN-Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2017. SDG index and dashboards report. Germany: Sustainable Development Network.

- Secretary-General, I. G. o. S. a. b. t., 2019. Global sustainable development report 2019: the future is now – science for achieving sustainable development. New York: United Nations.

- Sharpe, B., et al., 2016. Three horizons: a pathways practice for transformation. Ecology and society, 21 (2), 47. doi:10.5751/ES-08388-210247

- Shove, E., Watson, M., and Pantzar, M., 2012. The dynamics of social practice: everyday life and how it changes. Sage Publications Limited.

- Steffen, W., et al., 2015. Planetary boundaries: guiding human development on a changing planet. Science, 347 (6223), 1259855–1259856. doi:10.1126/science.1259855

- Stissing Jensen, J., Cashmore, M., and Späth, P., 2018. The politics of urban sustainability transitions: knowledge, power and governance. UK: Routledge.

- UK Architects Declare Climate and Biodiversity Emergency, 2019. https://www.architectsdeclare.com

- UN, 2015. Transforming our World: the 2030. New York: Agenda for Sustainable Development, United Nations.

- UN, 2018. World urbanization prospects. New York: UN-Habitat, United Nations.

- UN-Habitat, 2009. Global report on human settlements 2015. UN

- UN-Habitat, 2015. International guidelines on urban and territorial planning. Nairobi: UN-Habitat.

- UN-Habitat, 2017. Implementing the international guidelines on urban and territorial planning 2015-2017. Nairobi: UN-Habitat.

- UN-Habitat, 2018. Leading the change: delivering the new urban agenda through urban and territorial planning. Nairobi: UN-Habitat.

- United Nations, 2020a. Sustainable development goals. [Online] Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgs [Accessed 1 February 2020

- United Nations, 2020b. Voluntary national reviews database. [Online] Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/vnrs/ [Accessed 1 February 2020

- United Nations Development Programme, 2017. SDG accelerator and bottleneck assessment. New York: United Nations Development Programme.

- United Nations Global Compact, 2020. How your company can advance each of the SDGs. [Online] Available from: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/sdgs/17-global-goals

- Wallbaum, H. and Fudge, C., 2020. Private communication in the development of the case study one.

- Wallbaum, H., SabrinaKrank,, and RolfTeloh, 2011. Prioritizing sustainability criteria in urban planning processes. Journal of urban planning and development, 137 (1), 20-28.

- Wallner, H.P., Narodoslawsky, M., and Moser, F., 1996. Islands of sustainability: a bottom-up approach towards sustainable development. Environment & planning A, 28 (10), 1763–1778. doi:10.1068/a281763

- WBCSD & DNV GL, 2018. Business and the SDGs: A survey of WBCSD members and global network partners. Geneva: World Business Council for Sustainable Development.

- WEF, 2020a. The global risks report 2020 15th edition. Geneva: World Economic Forum.

- Whitmee, S., et al., 2015. Safeguarding human health in the anthropocene epoch: report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health. The lancet, 386 (10007), 1973–2028. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60901-1

- WHO 1986, Ottawa Charter For Health Promotion, 1986. First International Conference on Health Promotion, Ottawa, Canada, 17–21 November 1986. Geneva: World Health Organization

- WHO 2016 Health as the pulse of the new urban agenda: united Nations conference on housing and sustainable urban development, Quito, October.

- WHO, 2017a. Preventing noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) by reducing environmental risk factors. Geneva: World Health Organization. (WHO/FWC/EPE/17.1).

- WHO, 2018a. Ambient (outdoor) air quality and health. Key facts. Available from: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-%28outdoor%29-air-quality-and-health.

- WHO, 2018b. Burden of disease from the joint effects of household and ambient Air pollution for 2016; Summary of results, Available from: https://www.who.int/airpollution/data/AP_joint_effect_BoD_results_May2018.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed 11 December 2018.

- WHO, 2018c. Global action plan on physical activity 2018–2030: more active people for a healthier world. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- WHO, 2018d. WHO housing and health guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- WHO, 2019. Health, environment and climate change. Seventy-second world health assembly A72/15. Provisional agenda item 11.6. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- WHO & UNDP, 2016. Noncommunicable diseases: what municipal authorities, local governments and ministries responsible for urban planning need to know. World Health Organization and United Nations Development Programme.

- WHO & UNICEF, 2017. Progress on drinking water, sanitation and hygiene: 2017 update and sustainable development goal baselines. Geneva: World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund.

- World Economic Forum, 2018.

- World Green Building Council, 2020. Green building & the sustainable development goals. [Online] Available from: https://www.worldgbc.org/green-

- World Health Organization and UN-Habitat, 2010a. Global report on urban health: equitable, healthier cities for sustainable development. Nairobi: UN-Habitat.

- World Health Organization and UN-Habitat, 2010b. Hidden Cities: unmasking and overcoming health inequities in urban settings. Geneva-Kobe: WHO.

- World Health Organization and UN-Habitat, 2020. Integrating health in urban and territorial planning: a sourcebook. Geneva: WHO, Nairobi: UN-Habitat.

- World Sustainable Built Environment Conference, 2020. Beyond 2020. [Online] building-sustainable-development-goals. Available from: https://beyond2020.se/ [Accessed 1 February 2020].