ABSTRACT

Using empirical ethnographic data, and citing UK allotments as a case study, this think piece examines changes in the use of urban growing spaces as a response to a national crisis. Despite established links between urban growing spaces and improved health, competition for land globally threatens their existence. In the UK, COVID-19 has drawn attention to the importance of urban allotments as local resources and a means of increasing food security. Even so, some European local authorities quickly closed urban allotments in response to the pandemic. Allotments in their design offer a ready-made socially distanced solution to urban food, mental and physical health challenges. This think piece exposes the divergence between citizens’ actions and government responses to the pandemic.

© 2021 JC Niala. Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group.

On the 26th March, after having verified lockdown rules with the National Allotment Society, while loading my gardening tools into my car, a neighbour called from across the street, ‘So you’re off to dig for victory?’. His comment was not unusual – the language of war and references to the Second World War have become a recurrent theme of discourse in the UK since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. I was going to tend to my allotment plot on a site where I have also been conducting doctoral research for over 18 months, on urban gardeners and urban gardening in Oxford. Allotments are plots rented to individuals for the primary purpose of growing. Traditionally, allotments are the size of 10 poles, which is the equivalent of 250 square metres or about the size of a doubles tennis court. There are anywhere between dozens to over 100 of these plots (reasonably spaced from each other) depending on the size of an allotment site. Allotmenteers rent plots from an allotment association (often overseen by the local council) or a private landlord for between £20-£40 annually.

Since the 1918–1919 (Spanish flu) pandemic, studies have drawn a strong positive correlation between the practice of allotmenteering and improved health (Honigsbaum Citation2013). On the site where I conduct my research, allotmenteers regularly talk about the physical and mental benefits of tending their plots. For example, one woman specifically described her plot as being the key factor in her recovery from debilitating depression. Furthermore, allotment sites also promote a critical, local, climate-friendly impact on food security. Recent research concludes, ‘crop yields achieved by [allotment] own-growers were similar to commercial crop yields’ (Edmondson et al. Citation2020).

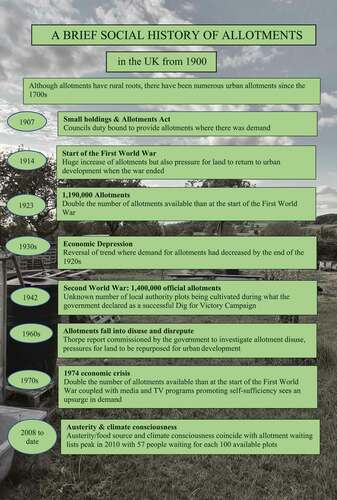

Whilst the rhetoric of the Second World War pervades both political and private dialogue surrounding COVID-19, there are marked differences between citizen and UK government responses when it comes to the use of urban allotments. During the Second World War, the British government initiated a ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign (which my neighbour was referring to) that not only made use of urban allotments but also greatly expanded allotment availability. This use of allotments as a solution to both food and health security stretches over a century of social history in the UK as summarised in .

Figure 1. A brief social history of allotments in the UK

Yet, in its response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs in the UK failed to include urban allotments. Instead, it devised ‘Pick for Britain’, a campaign encouraging people to volunteer or work on farms experiencing labour shortages due to reduced seasonal workers from Europe. This response is bewildering for several reasons. First, a key element of COVID-19 health measures around the world has been to limit movement. Given that part of the scheme was aimed at urban workers on furlough, encouraging their travel to the surrounding countryside would undermine efforts to contain the spread. Second, although they were potential beneficiaries, many farmers did not support the scheme, apprehensive that British urban workers would lack the requisite skills for the rigorous picking season. Some farmers were so concerned, that pre-lockdown, they organised for Romanian workers to be flown in and paid them to remain waiting until the season started (O’ Carroll Citation2020). Third, even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, global campaigns around climate change had increased public awareness of food miles, and innovative solutions grounded in urban farming were beginning to gain traction. There is a paradox that UK urban allotments, a much-appreciated part of material cultural heritage with proven health and food security benefits, and a historically proven to be actionable solution, were not being considered by the government.

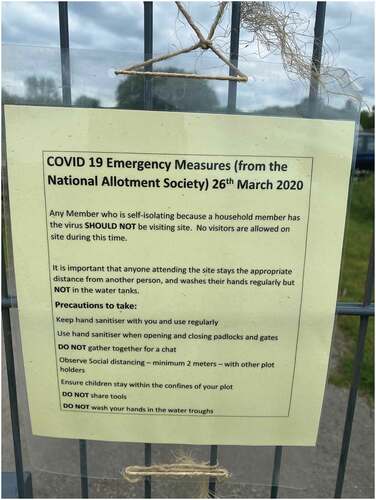

The UK government’s response appears oblivious to both the benefits that urban allotments offer, but also to citizen’s practices since lockdown. Globally, significant increases in the number of people growing in cities have been reported. In the UK, seed companies were quickly overwhelmed with orders. As the weeks of lockdown continued, the allotment site where I have my plot was the busiest I have seen it in the 18 months that I have been growing there. Simmering fears that access to allotments would be summarily curtailed prompted allotmenteers’ strict adherence to National Allotment Society guidelines (see ).

These fears were not unfounded. There were reports (from other sites which are overlooked) that members of the public had called the police when some allotmenteers were seen to be spending more than their allotted daily hour of exercise on the site. Governments of some European countries such as France and Ireland, with more stringent movement restrictions than the UK, swiftly closed down allotments (Mcgrath Citation2020).

The situation in Ireland illuminated critical debates around the difference between the ways in which allotments are categorised, which impacts how they are viewed as possible solutions, especially during the pandemic.

Dublin city councillors [were] split on whether allotments should be reopened.

“It is slightly contradictory to me to be keeping the parks open and be putting these restrictions on allotments,” says Fine Gael Councillor Paddy McCartan.

Says Green Party Councillor Claire Byrne: “They should really be treated as essential foods the same way as supermarkets should.

The nature of allotments allows people to work at a social distance, she says. “Also they are excellent for people’s mental health during this time.”

Independent Councillor Damian O’Farrell says that allotments are not a priority right now.

“Family members are dying, schools are closed and hundreds of thousands are out of work due to COVID-19,” he says.

On Monday, the Green Party put out a statement saying it had called on the government to lift restrictions on allotments.

A response from the Department of Housing – to a query from Green Party Senator Pippa Hackett – said that allotments weren’t exempt from the “stay at home” order as they don’t fall under the food-production exemption (Corrigan Citation2020).

The notion that allotments are not sites of food production is one that has arisen in my research on urban gardening in Oxford. Allotments there are overseen by planning officials (placing them in the same category as buildings and roads) and they also fall under leisure. This is why they were able to be accessed in the UK and not in Ireland, as in the UK, their access was secured as part of the daily exercise allowance.

What is clear from responses across Europe is that even during a global health pandemic, governments are not considering the health and food security potential of allotments. Yet contrastingly, as I gathered from allotmenteers during the course of socially distanced conversations held on allotment sites and via the telephone, many citizens cited their allotments as critical for maintaining physical and mental health and food security. One interviewee described how food grown on her plot, supplemented by surplus produce from other plot holders, had secured her food supply during a period of unemployment. Nearly all allotments have areas where allotmenteers lay out surplus seeds, plants and crops for others to freely access without being seen, sparing shame that can be associated with visiting food banks.

This care was also extended by the National Allotment Society guidance. Given the lengthy waiting lists nationally, allotment committees regularly inspect plots to ensure that they maintained. If not, allotmenteers receive ‘a letter’ of caution which can lead to their eviction. As COVID-19 took hold, the National Allotment Society called for a suspension of inspections and encouraged plot holders to support vulnerable allotmenteers unable to maintain their plots. On the site where I have my plot, allotmenteers either covered or maintained plots for the elderly and vulnerable others. An increased (socially distant) community spirit akin to that often attributed to Second World War Britain became apparent. This also ensured allotments would not become threatened in the future, if they were seen by local authorities to have fallen into disuse, meaning the land could be reclaimed.

Given that UK urban allotment sites are at their lowest level of availability since the Second World War, there is an urgency to save the remaining sites whilst the debate around their role and future continues. Governments have failed to heed the compelling arguments for their health and food security benefits; nevertheless, their function as an enduring part of material cultural heritage has saved various sites across the UK. Recent notable examples include the Walsall Road site in Birmingham, where its declaration as a historical site saved it from being repurposed and developed for the 2022 commonwealth games.

There are further areas of research required to understand the purpose and value of urban allotments, and to account for differences between citizen’s use of them and the government’s actions.

While there are more people growing in cities since the start of COVID-19, their motivations for doing so are still not fully understood. Early analysis of my research suggests various explanations. One is that people have more time. Many allotmenteers have cited increased time due to being furloughed. More flexible working from home arrangements have translated into hours saved from long commutes, freeing up more hours to spend at the allotments. For others, the sense of wanting to nurture something during a time of uncertainty and chaos prompted their growing. Others were thinking ahead to suggested food shortages (tomatoes, for example) and were aiming to provide for their families.

More research is also required to find out why government policy has changed. As the pressure on urban land increases, steps have been taken to remove the constraints to allow local authorities to repurpose what was previously growing land. Categorising allotments as sites of food production or nature carries profound consequences as exemplified in Ireland during the pandemic. These categorisations and their impacts need further investigation.

Finally, research is needed to uncover the meaning of urban land. UK examples such as the Walsall Road allotments show that heritage can protect urban growing spaces. Precedents from settler colonial countries such as Australia, Canada and the U.S. have shown that it is the ‘story of the land’, its cultural significance and the ways in which people have used and been connected to it, have been key in securing land rights for indigenous peoples (Brown Citation2006).

If cities are going to build resilience into their health and food systems in the light of future pandemics, then what COVID-19 has illuminated is the urgency to critically analyse the impact of the categorisation and views of urban allotment land within current local authority structures. The categories are vital as they directly lead to the inclusion or exclusion of urban allotments as possible solutions to health and food security.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

JC Niala

JC Niala is a doctoral anthropology researcher at St. Catherine’s College, University of Oxford. Her ethnographic research is based on allotments in the city of Oxford where she also practises urban gardening. Her interests include utopia and the imagination, banal nationalism & practices of cultivation. JC is currently writing a book entitled A Loveliness of Ladybirds based on current research and her experiences of establishing a successful organic farm in an informal settlement in Kibera, Nairobi. The book was shortlisted for the Nan Shephard Nature Writing Prize in 2019.

References

- Acton, L., 2015. Growing space: a history of the allotment movement. Nottingham: Five Leaves Publications.

- Brown, D., 2006. To speak of this land: identity and belonging in South Africa and beyond. Scottsville, South Africa: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

- Campbell, M.C.I., 2013. Allotment waiting lists in England 2013. West Kirby; Corby: Trasition Town West Kirby; The National Allotment Society.

- Corrigan, D., 2020. As some debate whether allotment should reopen, others continue to plant seeds [Online]. Dublin Inquirer. Retrieved from https://www.dublininquirer.com/2020/04/22/as-some-debate-whether-allotment-should-reopen-others-continue-to-plant-seeds

- Edmondson, J.L., et al., 2020. Feeding a city – Leicester as a case study of the importance of allotments for horticultural production in the UK. Science of the Total Environment, 705, 135930. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135930

- Honigsbaum, M., 2013. Regulating the 1918-19 pandemic: flu, stoicism and the Northcliffe press. Medical history, 57, 165–185. doi:10.1017/mdh.2012.101

- Mcgrath, D., 2020. ‘People are upset’: councils close allotments because of Covid-19 [ Online]. Journal Media Ltd. Retrived from https://www.thejournal.ie/allotments-closed-fingal-dublin-vegetables-5064463-Apr2020/

- O’ Carroll, L., 2020. Romanian fruit pickers flown to UK amid crisis in farming sector [Online]. Guardian News and Media Ltd. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/15/romanian-fruit-pickers-flown-uk-crisis-farming-sector-coronavirus