ABSTRACT

The health consequences of gentrification are little-understood, and researchers have called for qualitative studies to uncover potential causal pathways between gentrification and health. Resident Researchers in a Participatory Action Research study of community health in nine gentrifying neighborhoods across the Boston area hypothesized that financial insecurity is one pathway through which gentrification might harm health. We analyze qualitative data from semi-structured interviews with 40 financially vulnerable respondents to understand how the experience of living in a gentrifying neighborhood produces feelings of financial insecurity, and how such feelings may be harmful to health. Results indicate that experiencing gentrification exacerbates respondents’ sense of exposure to financial risk, while simultaneously reducing the perceived efficacy of available buffers against financial risks. The threats to an individual’s financial security introduced by gentrification-related changes in the neighborhood environment are stressful because they are appraised as taxing and exceeding the coping resources available to individuals. This gentrification-related financial insecurity is a meso-level phenomenon, produced by interactions between respondents and the contexts in which they live, with uncertain and uneven outcomes. Based on our findings, we argue that feelings of financial insecurity are one pathway through which the experience of living in a gentrifying neighborhood shapes health.

Introduction

As efforts to understand the relationship between gentrification and health intensify, there have been calls for research that centers the lived experiences of socially and economically vulnerable residents of gentrifying neighborhoods (Anguelovski et al. Citation2019), who have largely been left out of academic and policy dialogues about gentrification’s effects. In 2015, a consortium of academic researchers, community organizations, and neighborhood residents launched the Healthy Neighborhoods Study (HNS), a mixed methods Participatory Action Research study of community health in nine gentrifying neighborhoods across the Boston metropolitan area (Arcaya et al. Citation2018). A central motivation for our team was to better understand the lived experience of gentrification, particularly with respect to the role of gentrification-related development in shaping neighborhood-level social determinants of health. Resident Researchers (RRs) () and partner organizations expressed concern about the gap between their experiences and researchers’ and policymakers’ assessments of the impacts of gentrification. While research has found mixed evidence as to whether gentrification causes displacement and negative health outcomes (Schnake-Mahl et al. Citation2020), and as community partner organizations perceived policymakers to be more compelled by the rewards of development for the city and region than protecting the livelihoods of longstanding communities, residents in HNS communities reported that their growing insistence that gentrification is harmful to their communities was being disregarded and that they were being denied their right to be heard (DataCenter Citation2013, The Everett Community Health Partnership et al., Citation2019).

Table 1. Key terms.

This paper is driven by two hypotheses developed by HNS RRs over a series of collaborative research design and data analysis workshops conducted between 2016 and 2019 (Binet et al. Citation2019). The first hypothesis is that financial insecurity is a pathway through which gentrification affects health. The second hypothesis challenges narratives that gentrification mainly harms residents through residential displacement, with RRs hypothesizing that stress is a pathway by which gentrification affects health regardless of displacement outcomes. As part of collaborative qualitative data analysis in 2019, groups of RRs coded excerpts of in-depth interview transcripts that comprised answers to questions about financial security. RRs noted that respondents frequently identified housing cost increases as a cause of financial insecurity, and stress as a consequence of financial insecurity.

In this paper, we build on initial collaborative data analysis by more extensively analyzing qualitative data from semi-structured interviews with financially vulnerable residents of gentrifying neighborhoods in the Boston metropolitan area. The analysis explores how the experience of living in a gentrifying neighborhood may cause feelings of financial security, and further, how these feelings of financial insecurity adversely impact health through a stress pathway. We define financial security as an individual’s subjective sense of confidence in their ability to maintain a satisfactory quality of life given their exposures to financial risks and buffers against financial shocks (Bossert and D’Ambrosio Citation2013, Shafique Citation2018). We conceptualize stress as a transactional relationship between an individual and their environment (Lazarus and Folkman Citation1984, Avison and Pearlin Citation2010). Our findings complement quantitative studies of the financial consequences of gentrification (Ding and Hwang Citation2016), answer calls from other public health researchers to explore the role of financial stressors associated with gentrification in producing negative health outcomes (Schnake-Mahl et al. Citation2020), and contribute to the case for the utility of participatory methods in understanding complex health-place relationships.

Background and literature review

Growth and inequality in metro Boston

In recent decades, Boston has experienced considerable economic and job growth in high-wage sectors like finance and the life sciences, with a corresponding influx of socio-economically advanced residents (Metropolitan Area Planning Council Citation2014b, Citation2019, Modestino et al. Citation2019). By 2040, the population of the Boston region is projected to increase by between 6.6%-12.6%, with the highest rates of growth in the city’s inner core (Metropolitan Area Planning Council Citation2014b). Today, the region is witnessing rapid and widespread real estate development driven by high housing demand and economic growth, and shaped by emerging land use considerations such as climate change adaptation pressures. But the rewards of the city’s economic growth are not being equally shared across the population: economic mobility is declining while income inequality and wealth disparities are on the rise (Schuster and Ciurczak Citation2018).

Growth is occurring against the backdrop of an acute regional housing shortage and affordability crisis. Boston has not been constructing enough housing to meet its needs since the 1980s (Modestino et al. Citation2019). Recent projections indicate that housing demand is outpacing population growth due to declining household size, and that the rate of multi-family housing development needs to increase considerably to accommodate demand (Metropolitan Area Planning Council Citation2014a, Citation2014b). However, there is widespread opposition to new housing construction in the region, as well as restrictive zoning that makes constructing apartments illegal in many areas (Bunten Citation2020). These factors combine to make the Boston area one of the country’s most expensive housing markets. Rents in Boston rose 55% between 2009 and 2018, with home prices climbing at a similar rate, and similar increases across the region (Chakrabarti and Bologna Citation2018). Nearly half of renters in Boston are housing cost-burdened, paying over 30% of their income for housing (Modestino et al. Citation2019). Low- and middle-income households face tightly constrained housing options and the shortage of affordable housing options for families with children is particularly acute (Reardon et al. Citation2020).

These housing and economic pressures are more severe for the city’s residents of color. The racial wealth gap in the Boston area is among the widest in the nation: a recent report found that the median net worth of Black households is 8 USD compared to 257,500 USD for white households (Muñoz et al. Citation2015). A key cause of this disparity is decades of discriminatory housing and lending policies and practices at the federal, state and local levels that have inhibited people of color, and Black people in particular, from owning homes and accumulating intergenerational wealth, and leaving Boston as one of the most racially segregated cities in the country (Muñoz et al. Citation2015). During the 2008 housing market crash, foreclosures in Boston were heavily concentrated in inner core areas with high proportions of Black and Latinx residents like Roxbury, Dorchester and Mattapan (Hwang Citation2019). Recent eviction filings have also been disproportionately concentrated in Boston’s communities of color (Robinson and Steil Citation2020). Decades of dispossession and disinvestment have led to low-income, minority neighborhoods becoming the city’s hotspots of gentrification. A recent report found that, while the overall region is increasing in diversity, Boston core neighborhoods, from Downtown to Jamaica Plain, have become higher income and whiter since 1990 (Edozie et al. Citation2019).

Community-based organizations have tried to sound the alarm about development trends that they believe are contributing to gentrification in their communities, and have advocated for policies that would prevent displacement and preserve affordable housing. Examples of these efforts involve lobbying for city-wide policy changes like the Jim Brooks Community Stabilization Act in Boston, protesting unaffordable developments in Lynn, and New Bedford’s Cape Verdean community organizing to preserve the cultural identity of their neighborhood in the face of gentrification (Chakrabarti and Bologna Citation2018, Rios Citation2019, SouthCoastToday Citation2020). However, many of the efforts to shift policy – including the Jim Brooks Act and a state-level push to allow rent control – have been thwarted to date.

Gentrification and its consequences

Gentrification is a process of neighborhood-level socioeconomic ascent by lower income neighborhoods that had previously experienced disinvestment and economic decline (Smith Citation1998). Gentrification is typically characterized by in-migration of middle- and upper-middle class people, often white, as well as increases in housing prices, new amenities, and social and cultural shifts (Schnake-Mahl et al. Citation2020). The mechanisms underlying gentrification – including quickening real estate development and rising real estate costs, patterns of middle- and upper-class inward migration and displacement of pre-existing low-income residents, and state sponsorship – remain debated, as do their causes (Hackworth and Smith Citation2001, Lees et al. Citation2007, Hwang and Lin Citation2016, Brown-Saracino Citation2017). Gentrification has been observed and documented since the 1960s. While early waves of gentrification were characterized by homeowners rehabilitating and moving into older housing in working-class communities, scholars have argued that contemporary gentrification is driven primarily by rental market real estate speculation by developers and investors (Aalbers Citation2019).

To date, residential displacement has been the primary focus of scholarly attention on the potential harms of gentrification. However, analyses using quantitative data have largely found that rates of residential mobility in gentrifying neighborhoods are not substantively different from those in other low-income non-gentrifying neighborhoods (Ellen and O’Regan Citation2011, Ding et al. Citation2015, Hyra Citation2016). Nevertheless, qualitative researchers and community advocates have continued to raise concerns about gentrification’s harmful consequences (see Brown-Saracino Citation2017). As a result, scholars have also explored how gentrification can lead to other forms of displacement, such as socio-cultural and political displacement, as well as how patterns of residential mobility outcomes are stratified by race (Hyra Citation2015, Hwang and Ding Citation2020, Oscilowicz et al. Citation2020). In the effort to more fully understand the potential harms of gentrification, attention has also turned to the health and economic consequences of gentrification for lower-income residents.

Because gentrification results in higher area-level socioeconomic status, scholars have noted potential health benefits that may accrue via poverty deconcentration, better quality food options, improved access to amenities and city services, and new economic opportunities (Freeman Citation2006, Zukin et al. Citation2009, Sullivan Citation2014, Balzarini and Shlay Citation2016, Schnake-Mahl et al. Citation2020). On the other hand, researchers also speculate that gentrification could negatively impact health by exacerbating economic inequality, eroding social cohesion and community integration, and displacing people and businesses in the process (e.g. Anguelovski et al. Citation2019, Cole Citation2020). Regardless of directionality, we should expect exposure to gentrification to interact with race/ethnicity, gender, class, immigration status, and neighborhood tenure to produce different health impacts for different residents (Hill et al. Citation2005, Gibbons and Barton Citation2016, Gibbons Citation2019).

Recent research has also explored the financial consequences of gentrification for low-income residents of gentrifying neighborhoods. Using credit score data, Ding and Hwang (Citation2016) found that residents who were able to stay in gentrifying neighborhoods experienced improved financial health, via improved access to financial services, new labor market opportunities, and increasing home values for homeowners. Those who left experienced worse financial health, via rising housing and living costs, foreclosures, evictions, bankruptcies, financial burdens from moving, and broader declines in housing affordability. Displaced households have also been shown to experience higher levels of financial strain (Desmond Citation2018). Liquidity-constrained homeowners may be burdened by rising property taxes that accompany gentrification but it remains inconclusive whether property tax pressure in fact generates more displacement in gentrifying neighborhoods than elsewhere (Ellen and O’Regan Citation2011, Martin and Beck Citation2018, Hwang and Ding Citation2020). Overall, it has been posited that the financial consequences of gentrification may help explain the relationship between gentrification and health (Schnake-Mahl et al. Citation2020).

Financial security

Definition and drivers

Financial security refers to an individual’s feelings of security, anxiety, and safety in relation to their financial circumstances (Bossert and D’Ambrosio Citation2013). It can be understood as ‘the degree of confidence that a person can have in maintaining a decent quality of life, now and in the future, given their economic and financial circumstances’ and their capacity to prepare for and respond to adverse financial events (Shafique Citation2018, p. 10). Consensus on a precise definition has been elusive because the concept is based on an individual’s comparison of the present with past experiences and future expectations, and because feelings of security are based on personal circumstances (Bossert and D’Ambrosio Citation2013, Rohde et al. Citation2016).

Financial insecurity is not only a problem of low income; it may also reflect job insecurity, risk of poverty, income volatility, and inability to meet basic needs (Rohde et al. Citation2016). Since the 1980s, macro-level forces have increased economic insecurity steadily but unequally for US residents, with African American and Latinx individuals exposed to higher risks of declines in available household resources (Hacker et al. Citation2014). The shift to a work-based approach to welfare provision via the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act and an increased reliance on credit to make ends meet have led to greater month-to-month uncertainty and debt for low-income families (Halpern-Meekin et al. Citation2015). Low-income families also experience the most frequent and largest negative income shocks, which are exacerbated by cuts to public assistance and by large-scale economic shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Ha et al. Citation2020).

Yang and Matthews (Citation2010) suggest that neighborhood-level analysis can contribute to our understanding of the impact of financial security on health because neighborhoods allocate social and physical resources that mediate this relationship and moderate stress. A nation-wide lack of affordable housing is one key meso-level risk that may be a driver of financial insecurity. Between 2000 and 2015, median gross rent increased by 17% across the United States (Ellen and Torrats-Espinosa Citation2020). Although the overall number and share of cost-burdened renters are rising, low-income families are disproportionately impacted, with over half spending more than 50% of their income on housing (Desmond Citation2018). With rent burdens increasing, families are struggling to meet other essential expenses like food, childcare, healthcare, and utilities (Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies Citation2020).

Health impacts

Existing research shows that financial insecurity is an important predictor of self-rated health independently of individual demographic characteristics, job insecurity, and neighborhood disadvantage (Ferrie et al. Citation2003, Haines et al. Citation2009, Prentice et al. Citation2017). Perceived financial insecurity has been shown to negatively impact overall mental health (Rohde et al. Citation2016, Kopasker et al. Citation2018) and is associated with negative physical health effects (Blazer et al. Citation2005, Szanton et al. Citation2008, Rohde et al. Citation2017). The duration of exposure to financial insecurity is a significant determinant of its health impacts, with longer exposures increasing the likelihood of negative outcomes (Niedzwiedz et al. Citation2017). As the cumulative experience of financial insecurity builds, individuals may experience losses in perceived control, and may also become more vulnerable to other types of financial shocks (Pearlin and Bierman Citation2013, Koltai and Stuckler Citation2020). For people with lower socio-economic status, lower feelings of control have been shown to decrease the effectiveness of coping mechanisms, resulting in a ‘double disadvantage’ (Caplan and Schooler Citation2007, p. 43). Finally, we note that one recent study found that when changes in the built environment occur, residents with greater financial strain will likely experience greater declines in mental wellbeing (Foley et al. Citation2018).

Stress

Stress is a continuous process of feedback between the inner lives of individuals and the environments and social systems that they are a part of (Lazarus and Folkman Citation1984, Pearlin Citation1999, p. 396). Following other researchers who have explored the relationship between stress and changes in the built environment (Yang and Matthews Citation2010, Gibbons Citation2019), we use Lazarus and Folkman’s (Citation1984) model to conceptualize stress as a transactional relationship between the individual and the environment, based on two key components: appraisal and coping. Appraisal is the process by which an individual evaluates transactions between themselves and their environment, and is determined by both personal factors such as values and life experiences, and environmental factors such as the novelty, predictability, and uncertainty of events. Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984) identify three specific patterns of appraisal that can lead to different kinds of stress: harm, comprising damage or loss that has already happened; threat, defined as anticipation of imminent harm; and challenge, referring to demands that a person feels confident about overcoming. Coping refers to an individual’s ‘efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person’ (Lazarus and Folkman Citation1984, p. 141). Coping actions can either be problem-focused or emotion-focused. In this model, stress is a relationship between person and environment that is appraised as taxing, exceeding their coping resources, and/or endangering their wellbeing (Lazarus and Folkman Citation1984, p. 19).

Stress is an important biological pathway linking social conditions to health, predicting increases in both the severity and progression of a wide range of health outcomes including depression, asthma, and cardiovascular disease (Kubzansky et al. Citation2014). Some research claims that stress’ most significant impact on health comes from influencing the body’s overall vulnerability to disease through chronic wear and tear on the body’s regulatory systems, known as allostatic load (McEwen Citation1998). Stress is generated by ‘the psycho-social injuries of inequality structures’ in unequal societies, and perception of one’s position in society relative to others is a major stressor (Elstad Citation1998, p. 600). Moreover, low socio-economic position (SEP) creates disproportionate exposure to stressful living and working conditions, which when paired with the uneven distribution of buffering resources, is a key determinant of health inequities (Krieger Citation2013).

The meso-level context of the neighborhood also determines exposure to stressors, appraisal of stressors, and access to buffer resources. At the neighborhood level, people experience social disorganization such as political neglect, and gain access to coping resources such as social capital (Aneshensel and Sucoff Citation1996). Prior research has identified neighborhood-level characteristics of socio-economic disadvantage, including violence and crime, lack of resources, and lack of economic opportunity as predictors of higher individual-level stress (Hill et al. Citation2005, Matheson et al. Citation2006, Schulz et al. Citation2008, Aneshensel Citation2010). Neighborhoods with higher levels of residential stability and organizational resources like churches have been shown to buffer against stress, for example by facilitating social support and social cohesion (Israel et al. Citation2006, Stockdale et al. Citation2007).

While we are not aware of any studies that have empirically examined gentrification-induced financial insecurity as a source of unhealthy stress, other scholars have speculated that stress may be a pathway between gentrification and a wide range of health outcomes (Anguelovski et al. Citation2019, Gibbons Citation2019, Hyra et al. Citation2019). First, gentrification may cause stress by raising the threat of displacement and social network disruption (Freeman Citation2006, Newman and Wyly Citation2006, Nowok et al. Citation2013, Anguelovski et al. Citation2019). Cultural displacement may also lead to stress via feelings of exclusion and alienation, and to the erosion of health-protective buffers such as community connection, political voice, social cohesion, and community control (Gibbons Citation2019, Gibbons et al. Citation2019, Versey et al. Citation2019). Second, gentrification may lead to stress by increasing fears of rising real estate prices and housing unaffordability (Freeman Citation2006, Gibbons Citation2019, Hyra et al. Citation2019).

Gaps and contributions

Scholars have called for further research to better understand the causal pathways between gentrification and health, and highlighted financial stress as one unexplored mechanism by which gentrification may harm health (Cole Citation2020, Schnake-Mahl et al. Citation2020). Existing research on gentrification has been criticized for a lack of qualitative analysis and resident perspectives to elucidate the experience of living in a gentrifying neighborhood (Anguelovski et al. Citation2019, Hyra et al. Citation2019). While financial insecurity has been shown to negatively impact health, gaps remain in our understanding of how the experience of cumulative and place-based threats to financial wellbeing shape health. The present study provides insight into one potential causal pathway between gentrification and health by elaborating how place-based changes associated with gentrification produce feelings of financial insecurity that are stressful.

Methods

Study design

This analysis emerges from the Healthy Neighborhoods Study, a longitudinal Participatory Action Research study investigating the relationship between neighborhood development and community health in nine gentrifying communities across the Boston metro area () (Arcaya et al. Citation2018). The HNS is centered on a network of 45 ‘Resident Researchers’ (RRs) from each of the study sites, who collaborate with partners from local community-based organizations, public agencies, and academia. RRs live in the study neighborhoods and are diverse in terms of age, nationality, race, tenure in the neighborhood, and experience with research. RRs are involved in instrument design, data-gathering, data analysis, community knowledge share-back, and developing action strategies.

Figure 1a. Blue Hill Avenue, Mattapan, Massachusetts. Credit: Pi.1415926535, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 1b. Central Square, Lynn, Massachusetts. 2016. Credit: Kcboling, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 1c. A bus departs Nubian Square, Roxbury, Massachusetts. Credit: Beantowndude316 from USA, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

In 2016, during our first round of Collaborative Research Design workshops, RRs identified important connections between residents’ experiences of neighborhood changes and the social determinants of health in their communities, including: housing, neighborhood belonging, social support, local businesses, financial security, food security, ability to meet one’s priorities, discrimination, physical health and mental health, and ownership over neighborhood changes. RRs developed a community survey tool to gather quantitative data on residents’ experiences across these domains (Arcaya et al. Citation2018, Binet et al. Citation2019).

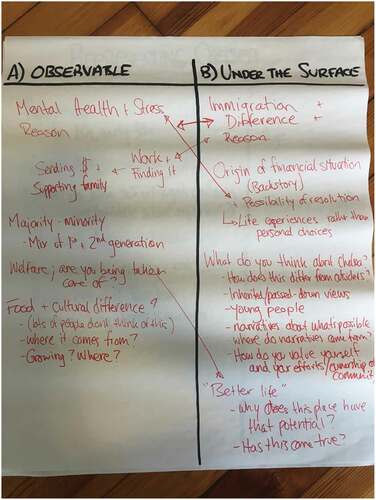

In 2017, RRs participated in a second series of Collaborative Research Design workshops that drew on their experiences fielding the community survey to develop a semi-structured interview tool to gather qualitative data. For example, in one activity, RRs developed crosswalk tables between ‘observable’ variables measured using the survey, and ‘under the surface’ dynamics associated with these variables that they wanted to better understand through interviewing. shows flip chart notes taken during one workshop with RRs in Chelsea, who said that what the survey observed about ‘mental health and stress’ could be better understood by inquiring into the origin of an individual’s ‘financial situation’ and the ‘possibility of resolution.’ RRs also identified themes that cut across the core study topics, such as ‘sense of control and direction in life,’ as priorities for the interview tool. They then worked with academic facilitators to draft, test, revise and finalize interview questions.

Figure 2. Flip chart notes taken as a conversation aide during an interview development workshop with Resident Researchers in Chelsea, MA.

In 2018, the HNS launched a nested longitudinal cohort of 150 respondents who would be contacted annually to complete both the survey and the semi-structured interview. Every third person approached by RRs during survey fieldwork was offered the option of participating in the longitudinal cohort. Respondents who agreed to participate in the cohort provided their contact information, and were re-contacted at a later date to schedule an appointment for their survey and interview. Academic members of the HNS team conducted the interviews in order to protect the privacy of respondents. Interviews ranged between 45 and 120 minutes, and respondents were compensated with a 60 USD Visa gift card for their time. Audio recordings of interviews were professionally transcribed. When respondents did not consent to be recorded, interviewers took hand-written notes.

Data

We generated an analytic subsample of 40 cohort members who reported risk factors for financial insecurity including annual household incomes below 30,000 USD; that it was ‘somewhat hard’ or ‘very hard’ to cover all of their bills and expenses each month; and/or being unemployed (). Using multiple variables to identify respondents at risk of financial insecurity allowed us to capture a diversity of ways in which financial insecurity is created and experienced. Our initial subsample of 40 interview respondents included residents of all nine study communities and allowed us to reach saturation (Saldana Citation2015).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of all eligible respondents and analytic subsample.

The demographic composition of the subsample is largely reflective of all financially vulnerable cohort members, with the exception that no homeowners were included. Roughly 65% were Black or Latinx, 78% were women, and about 75% had children. 62% of the subsample reported an annual household income of under 30,000, USD 35% reported being unemployed, and 73% reported that it was ‘somewhat hard’ or ‘very hard’ to cover their expenses each month. About 32% said that their health was ‘fair’ or ‘poor’.

Analysis

Our analysis investigates the hypothesis developed by RRs that gentrification produces financial insecurity that results in stress. The data were analyzed following the ‘flexible coding’ approach recommended by Deterding and Waters (Citation2018) for large interview studies. Transcripts of all interviews were index-coded according to the main themes of the interview guide, attribute codes were applied to each transcript based on respondent’s survey data, and case memos were written for each respondent.

We undertook a four-phase analytic coding process. First, we randomly selected 10 transcripts from the analytic subsample to undergo ‘open’ or ‘initial’ coding, using a mix of thematic and in vivo codes (Charmaz Citation2006, Saldana Citation2015). After cross-referencing with codes generated by RRs during a 2019 collaborative data analysis session focused on financial insecurity, the list was then organized and condensed into an analytical codebook. These codes captured different aspects of the experience of financial insecurity, including causes like income and housing cost, trajectories of financial (in)security over time, and responses to experiences of financial insecurity. This codebook was then used to code all 40 transcripts in the subsample, and further develop thematic memos.

Next, we performed a round of axial coding to better understand the contours of emerging themes and patterns of respondent experience and meaning-making, guided by thematic memos and the aforementioned coding exercise with RRs (Charmaz Citation2006, Saldana Citation2015). Finally, these axial codes were again organized and condensed into theme-specific codebooks. Data within each theme were re-coded using these codebooks, and then analyzed in further detail to the point of thematic saturation. The more granular understanding gained by this round of coding was used to add detail to thematic memos and identify data points to use as examples when writing up the analysis.

Results

We find that living in a gentrifying neighborhood exacerbates financial insecurity for financially vulnerable respondents in two ways. First, gentrification-related changes, particularly rising rents and cost of living that respondents associate with new residential development and the in-migration of wealthier people into the community, as well as the sense of deepening neighborhood-level economic inequality, increase respondents’ sense of exposure to financial risk. Second, the same processes of rising rents and cost of living along with deepening economic inequality undermine key buffers against financial risk indicated by respondents including job access, social cohesion, and collective efficacy. Respondents describe these patterns playing out both at the individual level in their own lives, and at the collective level via their perceptions of how the community as a whole is impacted. After describing these patterns of evidence, we present evidence of how financial insecurity exacerbated by gentrification poses health risks via feelings of stress and exposure to physical health hazards.

When we interpret our results through Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984) stress framework, we find that feelings of financial insecurity are stressful because they are appraised as taxing and exceeding the resources available to cope with the financial challenges posed by gentrification (). This is driven in part by uncertainty about the individual-level impact of place-based processes that are systemic in nature, and doubt about the efficacy of individual-level efforts to cope with these processes. Our results show that stress produced by gentrification-related financial insecurity can impact a variety of domains in respondents’ lives, including: social and family roles, particularly for caregivers; sense of wellbeing, including nutrition and work-life balance; sense of purpose and direction, particularly in relation to work; and living environment, including neighborhood belonging.

Figure 3. Results interpreted through Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984) stress model.

Increased exposures to financial risk

Respondents overwhelmingly reported that the physical, social and economic changes happening in their neighborhood exposed them to financial risks. Many pointed to rising housing costs as the biggest challenge facing their community, and attributed these increased costs to new housing development from which many felt excluded. ‘My rent’s going up. And that’s a scary place now, considering the amount of homelessness we have. And all these lovely high rises are coming up … but we’re not eligible for them. So the answer to the level of stress that could create heart attacks, aneurisms, strokes, it’s right there.’ Rising rents were seen as increasingly unaffordable, and respondents anticipate that this will be harmful to members of their community. ‘The housing that’s being built in the community, the average person that lives in the community, there’s no way they’d be able to afford that housing without having two full-time jobs and sacrificing something on the back-end,’ said a man in his 30s living in Dorchester, a rapidly-gentrifying neighborhood next to downtown Boston.

Respondents often perceived links between rising rents and increasing levels of economic inequality that placed long-time residents at a disadvantage relative to wealthier newcomers for whom the neighborhood represents an economic opportunity. Rent increases ‘have nothing to do with the people living in my neighborhood, and everything to do with the people who want to own my neighborhood,’ the man from Dorchester said. A fellow Dorchester resident explained that ‘it all relates back to the economic equality … I want to put that at the forefront because these rents keep going higher. I’ve seen a number of people have to move out of the city. And if you’re not making it, you’re really not making it.’ A woman in her 30s renting in Mattapan, a majority-Black community neighboring Dorchester with a large immigrant population, situated unaffordable residential development within broader historical patterns of land use. ‘We have not been able to thwart the rapid land-use crisis that we’re experiencing … how we value land based on who lives on the land … the land-use situation is a symptom of wealth inequality. And it’s a systemic issue that needs to be addressed for everybody because … sooner or later everyone’s going to be poor,’ she said.

As a result of rising rents, the threat of displacement felt imminent for some. Many have seen friends and relatives leave their neighborhood due to increasing housing costs, which raised feelings of vulnerability due to loss of social cohesion, as well as fear that the same may soon happen to them. ‘To have them just keep hiking it up and up, it’s not fair … and it pushes families out. Families make good neighborhoods,’ a woman renting in Dorchester said. For some, displacement is already a reality, especially without a good-paying job that can buffer against the shock of rising rents. One respondent described how, upon losing a job, she was unable to continue to afford her housing because rising rents and child-related expenses had left her with no savings to pay her rent and care for her children while being temporarily unemployed. She ended up being forced to move to a shelter with her children. Another respondent in Fall River described a chain of evictions as his family moved between a series of unaffordable housing options across the greater Boston region in an effort to avoid ending up in a shelter.

Respondents described how higher rents also contribute to financial insecurity by narrowing the margins for unexpected events and expenses. ‘When you rent, it feels like money is just flying out the window,’ said a respondent in Roxbury. Without good-paying jobs and affordable housing, respondents were by and large unable to save money, and often forced to make sacrifices on other expenses such as food and childcare in order to afford housing. ‘It’s not going to be unexpected, but it’s going to be a little bit hard … the rent is going to go higher [and] we’re still trying to figure out how we’re going to be able to afford it,’ said a respondent working to help his mother afford their rent in Lynn, a formerly industrial city north of Boston where gentrification is accelerating. Difficulty saving may expose residents to more financial challenges in the future. For example, multiple respondents reported that rising rents inhibited them from responding to emergent housing needs due to increasing family sizes.

In parallel, respondents saw their cost of living increasing in line with new commercial developments, like the revitalized South Bay shopping center in Dorchester, changing the business landscape in their communities. Respondents reported new challenges related to the accessibility of affordable goods and services, especially as transportation within the region becomes costlier. One respondent described how it was too expensive to shop locally, and she had to solicit rides from friends to more affordable grocery stores further outside of the city. Respondents reported that unaffordable food options limited both how much food they bought, and how frequently they could choose options that they deemed healthier. When the rising cost of living introduces or exacerbates unaffordability in every aspect of life, respondents were left feeling like they were unable to contribute to their community: ‘I want to support my community, I do. But if I can go over there and get a loaf of bread for 1 USD and [here] I got to pay 3 USD and I got a 16-year-old girl, then, of course, what are you going to do? … I’m on a budget, a fixed income … I can’t pay them extra 2 to 3 dollars.’

The experience of increasingly unaffordable housing and difficulty meeting basic needs, in a context where exposures to further financial risk are rising and buffers dissolving, undermines respondents’ confidence in their capacity to weather future financial challenges. Respondents report that it feels like their ‘money’s not worth anything’ and they question ‘what are you really getting’ with what they do have access to. Unaffordability is perceived as widespread and structural, extending beyond them as individuals and impacting the community at-large.

Weak or eroding buffers against financial insecurity

Respondents identified good jobs as essential for feeling financially secure in the face of rising rents and a higher cost of living. However, some respondents reported that it ‘doesn’t matter if you have a good job’ because wages will continue to be outpaced by rising costs of living regardless of personal circumstances. Others further argued that the new jobs being created by commercial development in their community weren’t enough to keep up with rising rents: ‘A café don’t pay well enough for somebody to survive in Brockton. Because rent is super high over here, and the bills, and working at a café is not really going to cut it,’ a woman in her 20s with two young children said. Some respondents reported trying to take on extra work to cover increases in rent, but one noted that ‘you shouldn’t have to work 20 more hours to cover a little increase in rent. You should be able to still work 40 hours and cover that little increase in rent.’ Rising rents and cost of living undermine the effectiveness of good, reliable jobs as a buffer against financial insecurity, further threatening residents’ ability to stay in their neighborhoods.

In addition to income-related buffers against financial insecurity, respondents also identified social cohesion as a potential buffer against financial insecurity. However, many felt that social cohesion in their communities was being eroded by the financial pressures of gentrification, which inhibited residents from socializing with their neighbors. One respondent in her 40s living in Roxbury reflected that ‘one big barrier that we have in our community is social cohesion … because of economics, money … It’s sad because things are so expensive and then money is short. And people can become isolated and they don’t want to come out … ’ This pattern was seen as a threat to the strength of their community to collectively influence their conditions. Another respondent from Dorchester explained how the need to take on additional work to make ends meet comes at the expense of the ability to engage with one’s community. ‘I know there’s a number of women who are working multiple jobs or multiple shifts … a lot of the times, they’re exhausted by the time they get home. And that leads to them not being able to read that community newsletter as much as they normally would want to … ’ Moreover, there are community-wide consequences to an ever-greater number of individuals on shaky financial footing, another respondent noted: ‘I have found, when your bottom falls out … it costs the city more … than if we had the supports to keep people healthy, a healthy community … And I don’t think they realize that yet because they’re busy building the city.’ The sense that the community is being left behind to fend for itself against those with more wealth and social standing, without the capacity to rebuild the social cohesion necessary to maintain collective stability, is one of collective insecurity.

Respondents expressed a newfound sense of exclusion as they witnessed their neighborhoods change only for the benefit of newcomers. ‘It’s not families anymore, it’s three roommates, and … they’ll pay it without even a blink of an eye … it kicks families out.’ Some even feel targeted: ‘that’s like being racist too in some kind of way when you just make everything so high and you know that’s a low-income area already and then you put the rent up – you know we can’t afford it.’ A respondent from Chelsea, dubbed ‘the new “it” zip code’ in The Boston Globe (Ross Citation2014), encapsulated what many others echoed as a growing sense of financial exclusion: ‘you’re seeing they’re building these nice places, and you’re a decent person, you wish you could be there, but you have to stay stuck where you are … it seems to be more for outsiders now … the little people are getting left behind or discarded.’ For some, what results is a sense of loss and frustration: ‘The rent is high and you can get a job but the jobs are paying 11 USD an hour. And it just seems like you keep hitting a brick wall … ’

The contribution of financial insecurity to stress

This section reports on the ways in which respondents connected feelings of financial insecurity to stress. Although not all respondents made direct connections from gentrification to financial security to stress, we assume that since all respondents live in gentrifying areas and our data show that they associate the experience of living in gentrifying areas with increased financial insecurity, that gentrification is partly responsible for the feelings of financial insecurity that respondents linked to stress.

Respondents identified feelings of stress as the main outcome of the process whereby gentrification intensified exposures to and eroded buffers against financial insecurity. This stress impacted respondents in important life domains: wellbeing, role/responsibilities, purpose/path, and environment (). Respondents who describe feeling stressed about finances said that it detracts from their ability to look after their own wellbeing. ‘It just doesn’t leave us with the mental capacity to take care of ourselves and notice, “Hey, I’m not doing so well.”’ Similarly, a young respondent from Chelsea said that because of her financial situation, ‘I’m always stressed. Stressed so much … which kind of carries on into my ability to seek help, and stuff like that.’ Another respondent, when asked about how her financial situation affects her well-being, said ‘At one point, I got really stressed out, and I couldn’t eat and I was just a mess. And then I got really sick. Ended up in the hospital for stress … It messed me up.’ Examples like these show how the experience of being financially insecure in a gentrifying neighborhood limited respondents’ access to coping mechanisms that could have helped them manage their stress.

Relatedly, stress can also emerge in relation to roles and responsibilities, such as being a caregiver for young children. One respondent described her difficulty paying outstanding childcare fees for her grandchildren as summer childcare options in her neighborhood, Roxbury, got more expensive. ‘I’m trying to take care of them, trying to take care of my health, trying to do what I can do. But I think it’s all about money … it was a lot of stress on me. It took its toll, I was under a lot of stress. I was worrying.’ Another described the stress of dealing with her children’s health challenges as a working single mother. ‘Most every winter, he gets asthma. But he gets pneumonia with it, so it’s like you’re always running.’

As part of efforts to cope with financial insecurity, respondents reported being stuck in stressful jobs, insecure jobs, jobs that exacerbate existing injuries and cause pain, or experiencing stress from working more than one job. Consequences included lack of sleep and exhaustion, diminished sense of control, and a loss of self-worth. Respondents also reported that balancing work with other roles and responsibilities, such as childcare, amidst rising rents and cost of living, was leading to greater stress, feelings of social isolation, and less rest. Overall, respondents who indicated that they were looking for new jobs felt stress from the sense that whatever job market growth there was in the community would not be sufficient to help them keep up with the rising cost of living. ‘I just don’t know how to feel here anymore,’ said one respondent about her gentrifying neighborhood, ‘because I’ve never tried so hard to get ahead and things just go so far backwards in my life.’ Respondents perceived a lack of reliable, well-paying jobs that could have helped them cope with the stress brought on by rising rents and cost of living.

Another source of stress for financially insecure respondents is substandard or unsafe housing due to a lack of other affordable options, and associated health risks. Respondents described issues including pests, mold, lead, disrepair, and poor insulation in the winter. One respondent described her struggles staying warm: ‘during the winter, it’s really bad. I’m scared right now because I know the [heat] bill’s probably going to be like 300 USD … and then I pay my rent late … And it just gets hard … I want to eat healthy, but the cheaper stuff is really unhealthy. So I’d rather be really unhealthy and not starve, than be healthy and starve after the third week of the month.’ Another respondent described that her grandchildren had asthma and allergies from mold in their apartment and mice in their building. ‘I’m very blessed that I have a roof over my head and I don’t have to live in a shelter … but just still sometimes, I think, you have to get what goes along with it.’ Addressing these issues, and the health consequences that result from them, creates additional financial challenges for respondents such as medical costs, the costs of cleaning and repairs, and/or the costs of moving. If gentrification continues to undermine the material and psychological coping resources available to financially insecure people, role-, job- and housing-related stressors and their consequences may intensify.

Resident reports of health consequences

Despite the difficulties of perceiving the effects of stress on one’s own health, several respondents reported examples of proximate health consequences linked to stress. When stress became overwhelming and unmanageable beyond available coping resources, respondents shared that they had to make tradeoffs between essential needs like food and housing, with physical costs like poor nutrition. Another tradeoff included sacrificing housing quality for affordability, with one respondent directly linking mold and pests to allergies and asthma among her children. Respondents also noted that their mental health was being impacted by the stress of financial insecurity, including via: sense of exclusion, working to the point of exhaustion, and depression. Ultimately, being financially insecure in a gentrifying neighborhood exposed respondents to more stressful living and working conditions linked to negative health outcomes.

Discussion

The purpose of this paper is to explore whether and how gentrification adversely impacts the health of economically vulnerable residents of gentrifying neighborhoods by contributing to feelings of financial insecurity. Resident Researchers in a longitudinal Participatory Action Research (PAR) study of the relationship between gentrification and community health challenged the idea that gentrification harms residents through displacement alone. They suggested that stress was another possible harm, and hypothesized that stress may result from feelings of financial insecurity that emerge in response to the experience of living in a gentrifying neighborhood. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed semi-structured interview data gathered from financially vulnerable individuals living in the study neighborhoods. We found that neighborhood changes associated with gentrification but not necessarily mediated by displacement – such as rising rents, residential and commercial development, and community fragmentation – exacerbate respondents’ financial insecurity by increasing their sense of exposure to financial risks and eroding perceived buffers against financial shocks. As a result, respondents appraised future financial challenges as more serious and difficult to overcome, resulting in greater feelings of financial insecurity. Our results also show that financial insecurity acts as a form of stress that impacts respondents’ ability to look after their own wellbeing and adds pressure to important roles such as caregiving.

Our findings show the importance of meso-level, place-based changes in producing financial insecurity, despite an overwhelming focus in existing literature on micro- and macro-level determinants at the expense of meso-level explanations that ‘center on the processes by which people interact with the places in which they live.’ (Whitehead et al. Citation2016, p. 55). Respondents indicated that their financial challenges result from the place-based manifestation of processes that are systemic in nature and unlikely to be resolved through individual action. Respondents experienced uncertainty because of this, knowing that the changes they see will negatively impact some neighborhood residents, perhaps but not necessarily themselves, and that this would in turn exacerbate economic inequality within the neighborhood. Respondents also indicated that community-level consequences of financial insecurity – such as a loss of social cohesion – impact the community’s power over their conditions, compounding the sense of vulnerability to the financial pressures of unmitigated gentrification and resulting economic inequality.

Interpreted through Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984) stress framework, our results show that when respondents have feelings of financial insecurity brought on by their experience of gentrification, these feelings are appraised as stressful because the threats, harms and challenges associated with financial insecurity – especially the inability to afford housing while also covering other basic expenses, the threat of displacement, the inability to satisfactorily fulfill one’s caregiving responsibilities, lost sense of community, and the difficulty of staying healthy – exceed the coping mechanisms available to respondents. Problem-based coping resources – such as social support, opportunities for better-paying jobs, or more affordable housing options – that could act as buffers against financial risks are minimal or inaccessible, and progressively eroding as gentrification proceeds. Emotion-based coping resources are also being undermined, for example via insufficient time for self-care, however these also pose relatively little potential of alleviating stress rooted in one’s finances.

Although literature shows that the health consequences of stress include non-obvious, subclinical, wide-ranging, cumulative, lagged, and/or latent effects that would be difficult or even impossible for residents to report directly, we nevertheless heard reports of immediate and identifiable physical costs directly related to stress, including poor nutrition, sacrificed housing quality and resulting exposure to asthma triggers such as mold and pests, and mental health impacts stemming from a sense of exclusion, working to the point of exhaustion, and depression. Cellular aging, increased susceptibility to infection through decreased immune function, dysfunction of the endocrine system, and other physiological impacts shown in the literature cannot be accounted for directly in our analysis, such that the specific health consequences reported in this study severely under-represent the true health cost of gentrification-related stress (Segerstrom and Miller Citation2004, Glaser and Kiecolt-Glaser Citation2005, Kubzansky et al. Citation2014, Oliveira et al. Citation2016).

In sum, data on the lived experience of financial insecurity in gentrifying neighborhoods suggest that gentrification has far-reaching implications for stress, and consequently for health, that extend beyond the experience of displacement. These results suggest that even residents able to stay in place throughout periods of gentrification face health risks caused by rapid socioeconomic ascent, despite the fact that stably housed long-time residents are generally viewed as potential beneficiaries of gentrification.

Limitations

We note four limitations to our analysis. First, while we were readily able to identify a subsample of the HNS interview cohort who were likely to be experiencing financial insecurity, due to the socio-economic profile of the cohort we were not able to identify a viable analytic subsample of cohort members who were likely to be financially secure. Thus, we were unable to explore the counterfactual situation of how gentrification might produce feelings of financial security. Second, the analytic subsample did not include any homeowners despite 10% of eligible respondents being homeowners (). We therefore could not examine gentrification’s influence on financial security among homeowners. We note that Resident Researchers reported challenges recruiting respondents who were homeowners and respondents residing in wealthier areas of their neighborhoods. Third, while our interview questionnaire asked about respondents’ feelings of financial security, the questionnaire did not ask for a detailed financial history, thus limiting our ability to more accurately delineate the interplay between perceived neighborhood changes and prior financial events in producing feelings of financial insecurity. Finally, since financial security is a subjective phenomenon, we could not be completely certain about the comparability of these feelings or the factors contributing to them across respondents.

Implications

Our findings demonstrate the importance of designing research on experiences and health effects of gentrification in collaboration with community residents. RRs initially hypothesized that financial security was a link between the experience of living in a gentrifying neighborhood and stress, and their participation in collaborative research design workshops shaped the interview tool used to gather the data we analyzed. During collaborative data analysis workshops, RRs also informed the codes used in our analysis and the themes that guided our analytical memos, for example by highlighting unique dimensions of stress faced by caregivers. Our study demonstrates that future research into the relationship between gentrification and health can be strengthened by employing participatory methods to center resident experiences in hypothesis generation, the design of research tools, and data analysis.

Substantively, our analysis shows that neighborhood-level changes associated with gentrification produce stress for low-income residents via exacerbating feelings of financial insecurity. Our findings complement quantitative studies of the financial consequences of gentrification to show how these consequences are experienced by individuals, and how they become embodied via stress. In turn, these findings contribute to our understanding of stress as a key pathway between gentrification and health outcomes by highlighting the role of the subjective experience of gentrification in producing stress. By producing stress, gentrification may not only negatively impact the health of low-income neighborhood residents, but also deepen health inequities by contributing to racial and economic disparities in allostatic load (McEwen Citation1998, Geronimus et al. Citation2006). Moreover, our findings about role-based stress for caregivers raise the question of whether stress is a mechanism through which negative experiences of gentrification have intergenerational consequences for health and wellbeing (Fullilove Citation2005, Yost Citation2014).

Our analysis indicates that much of gentrification-related financial insecurity is a meso-level phenomenon, produced by interactions between respondents and the contexts in which they live. This finding highlights the limitations of only measuring the harms of gentrification by way of monetary costs, instances of displacement, and other outcomes that would be uniformly negative regardless of context or personal characteristics. Instead, it indicates that gentrification-related harms may also come from processes with uncertain outcomes that may vary group by group and place by place, and which may negatively impact wellbeing through psychosocial pathways, such as by exacerbating inequalities, even in the absence of negative individual-level material outcomes. Future research into financial insecurity resulting from neighborhood changes would benefit from explicit focus on meso/community-level explanations of how the subjective experience of financial insecurity is produced. The contributions of individual- vs. community- vs. societal-level factors to financial insecurity may lead to different outcomes in terms of stress.

The results suggest that investments in buffers against financial insecurity in gentrifying neighborhoods, such as rent control, preservation of affordable housing, increased access to affordable childcare, and the creation of well-paying jobs for the community, can be seen as health-promoting interventions. Crucially, our data also show that respondents see social and cultural properties of their neighborhoods as important protections against financial insecurity. Investing in strategies to preserve social and cultural cohesion, social support, and resident control over neighborhood changes may also promote health by mitigating feelings of powerlessness and exclusion that respondents linked to financial insecurity and ensure more robust coping mechanisms for stress associated with financial insecurity. The importance of social infrastructure and community control over neighborhood changes as buffers against the impacts of gentrification indicates that residents and community-based organizations should play central roles in designing interventions that alleviate financial insecurity and stress.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the members of the Healthy Neighborhoods Research Consortium for their participation in the study. In particular we would like to thank the Resident Researchers and Site Coordinators who participated in the 2019 Collaborative Data Analysis workshop on financial security for their contribution to the analysis: Dina Abreu, Carl Baty, Marshall Delpé, Yrma Fiestas, Josée Genty, Robyn Gibson, Goldean Graham, Gail Latimore, Leilani Mroczkowski, Marcia Picard, Andrea Tulloch, Joseph Vann, and Vanessa Vieira; as well as our colleagues Andrew Seeder, Kayla Tabb, and Matt Weinstein for co-facilitating and note-taking during the workshop. We are also grateful to Samara Ford for their support with data analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Andrew Binet

Andrew Binet, MCP, is a PhD candidate in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning at MIT. His research sits at the intersection of planning and health, and focuses on how the urban environment shapes relations of care and social reproduction.

Gabriela Zayas del Rio

Gabriela Zayas del Rio is an MCP candidate in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning at MIT. Her research interests encompass the fields of urban planning and public health particularly focused on the links between urban environments and mental health.

Mariana Arcaya

Mariana Arcaya, ScD, is an Associate Professor of Urban Planning and Public Health at MIT. Her research explores dynamic relationships between geographic contexts, particularly neighborhoods, and health.

Gail Roderigues

Gail Roderigues is an advocate, educator and coordinator of community health and wellness at the Southcoast YMCA and Voices for a Healthy Southcoast. Gail has been a coordinator for the Healthy Neighborhoods Study for over 5 years, supporting and advocating the work of resident Researchers and using her community knowledge and relationships to shape key questions.

Vedette Gavin

Vedette Gavin, MPH, MPA, is a Senior Research Consultant at the Conservation Law Foundation (Boston, MA) where she leads community-based participatory research studies and evaluation projects that explore the relationships between neighborhoods, structural and social determinants of health, community power, and wellbeing.

References

- Aalbers, M.B., 2019. Introduction to the forum: from third to fifth-wave gentrification. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 110 (1), 1–11. doi:10.1111/tesg.12332.

- Aneshensel, C.S., 2010. Neighborhood as a social context of the stress process. In: W.R. Avison, et al., eds. Advances in the conceptualization of the stress process. New York: Springer, 35–52. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-1021-9_3.

- Aneshensel, C.S. and Sucoff, C.A., 1996. The neighborhood context of adolescent mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 37 (4), 293–310. doi:10.2307/2137258.

- Anguelovski, I., et al., 2019. Gentrification and health in two global cities: A call to identify impacts for socially-vulnerable residents. Cities & Health, 1–11. doi:10.1080/23748834.2019.1636507.

- Arcaya, M.C., et al., 2018. Community change and resident needs: designing a participatory action research study in Metropolitan Boston. Health & Place, 52, 221–230. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.05.014

- Avison, W.R. and Pearlin, L.I., Eds., 2010. Advances in the conceptualization of the stress process: essays in honor of Leonard I. Pearlin. New York, NY: Springer.

- Balzarini, J.E. and Shlay, A.B., 2016. Gentrification and the right to the city: community conflict and casinos. Journal of Urban Affairs, 38 (4), 503–517. doi:10.1111/juaf.12226.

- Binet, A., et al., 2019. Designing and facilitating collaborative research design and data analysis workshops: lessons learned in the healthy neighborhoods study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16 (3), 324. doi:10.3390/ijerph16030324.

- Blazer, D.G., Sachs-Ericsson, N., and Hybels, C.F., 2005. Perception of unmet basic needs as a predictor of mortality among community-dwelling older adults. American Journal of Public Health, 95 (2), 299–304. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2003.035576.

- Bossert, W. and D’Ambrosio, C., 2013. Measuring economic insecurity (No. 2013/008). WIDER. Available from: http://www.wider.unu.edu/publications/working-papers/2013/en_GB/wp2013-008/

- Brown-Saracino, J., 2017. Explicating divided approaches to gentrification and growing income inequality. Annual Review of Sociology, 43 (1), 515–539. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053427.

- Bunten, D.M. (2020, January 17). YES: it will protect tenants: as gentrification extends into ever more communities, rent control offers Boston the clearest means available for protecting the tenants and communities at risk. Boston Globe, A.11.

- Caplan, L.J. and Schooler, C., 2007. Socioeconomic status and financial coping strategies: the mediating role of perceived control. Social Psychology Quarterly, 70 (1), 43–58. doi:10.1177/019027250707000106.

- Chakrabarti, M. and Bologna, J. (2018, May 16). How Boston’s big attempt at rental law reform failed. In Radio Boston. WBUR.

- Charmaz, K., 2006. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. 1st ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Cole, H.V.S., 2020. A call to engage: considering the role of gentrification in public health research. Cities & Health, 1–10. doi:10.1080/23748834.2020.1785176.

- DataCenter, 2013. An introduction to research justice. Oakland, CA: DataCenter.

- Desmond, M., 2018. Heavy is the house: rent burden among the American urban poor. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 42 (1), 160–170. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12529.

- Deterding, N.M. and Waters, M.C., 2018. Flexible coding of in-depth interviews: a twenty-first-century approach. Sociological Methods & Research, 0049124118799377. doi:10.1177/0049124118799377.

- Ding, L. and Hwang, J., 2016. The consequences of gentrification: a focus on residents’ financial health in Philadelphia. Cityscape, 18 (3), 27–55.

- Ding, L., Hwang, J., and Divringi, E., 2015. Gentrification and residential mobility in Philadelphia (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2675379). Social Science Research Network. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2675379

- Edozie, R.K., et al., 2019. Changing faces of greater Boston. Boston, MA: Boston Indicators, The Boston Foundation, UMass Boston and the UMass Donahue Institute.

- Ellen, I.G. and O’Regan, K.M., 2011. How low income neighborhoods change: entry, exit, and enhancement. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 41 (2), 89–97. doi:10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2010.12.005.

- Ellen, I.G. and Torrats-Espinosa, G., 2020. Do vouchers protect low-income households from rising rents? Eastern Economic Journal, 46 (2), 260–281. doi:10.1057/s41302-019-00159-y.

- Elstad, J.I., 1998. The psycho-social perspective on social inequalities in health. Sociology of Health & Illness, 20 (5), 598–618. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.00121.

- The Everett Community Health Partnership, GreenRoots, Research Action Design, & MIT CoLab, 2019. Greater Boston anti-displacement toolkit. Available from: https://www.greaterbostontoolkit.org/en

- Ferrie, J.E., et al., 2003. Future uncertainty and socioeconomic inequalities in health: the Whitehall II study. Social Science & Medicine, 57 (4), 637–646. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00406-9.

- Foley, L., et al., 2018. Longitudinal association between change in the neighbourhood built environment and the wellbeing of local residents in deprived areas: an observational study. BMC Public Health, 18 (1), 545. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5459-9.

- Freeman, L., 2006. There goes the ’Hood: views of gentrification from the ground up. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

- Fullilove, M.T., 2005. Root shock: how tearing up city neighborhoods hurts America, and what we can do about it. New York, NY: One World/Ballantine.

- Geronimus, A.T., et al., 2006. “Weathering” and Age patterns of allostatic load scores among blacks and whites in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 96 (5), 826–833. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.060749.

- Gibbons, J., 2019. Are gentrifying neighborhoods more stressful? A multilevel analysis of self-rated stress. SSM - Population Health, 7, 100358. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100358

- Gibbons, J. and Barton, M.S., 2016. The association of minority self-rated health with black versus white gentrification. Journal of Urban Health, 93 (6), 909–922. doi:10.1007/s11524-016-0087-0.

- Gibbons, J., Barton, M.S., and Reling, T.T., 2019. Do gentrifying neighbourhoods have less community? Evidence from Philadelphia. Urban Studies, 0042098019829331. doi:10.1177/0042098019829331.

- Glaser, R. and Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K., 2005. Stress-induced immune dysfunction: implications for health. Nature Reviews Immunology, 5 (3), 243–251. doi:10.1038/nri1571.

- Ha, Y., et al., 2020. Patterns of multiple instability among low-income families with children. Social Service Review, 94 (1), 129–168. doi:10.1086/708180.

- Hacker, J.S., et al., 2014. The economic security index: a new measure for research and policy analysis. Review of Income and Wealth, 60 (S1), S5–S32. doi:10.1111/roiw.12053.

- Hackworth, J. and Smith, N., 2001. The changing state of gentrification. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 92 (4), 464–477. doi:10.1111/1467-9663.00172.

- Haines, V.A., et al., 2009. Socioeconomic disadvantage within a neighborhood, perceived financial security and self-rated health. Health & Place, 15 (1), 383–389. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.01.011.

- Halpern-Meekin, S., et al., 2015. It’s not like I’m poor: how working families make ends meet in a post-welfare world. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

- Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, 2020. America’s rental housing 2020. Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, 44.

- Hill, T.D., Ross, C.E., and Angel, R.J., 2005. Neighborhood disorder, psychophysiological distress, and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46 (2), 170–186. doi:10.1177/002214650504600204.

- Hwang, J., 2019. Racialized recovery: postforeclosure pathways in Boston neighborhoods. City & Community, 18 (4), 1287–1313. doi:10.1111/cico.12472.

- Hwang, J. and Ding, L., 2020. Unequal displacement: gentrification, racial stratification, and residential destinations in Philadelphia. American Journal of Sociology, 126 (2), 354–406. doi:10.1086/711015.

- Hwang, J. and Lin, J., 2016. What have we learned about the causes of recent gentrification? Cityscape; Washington, 18 (3), 9–26.

- Hyra, D., 2015. The back-to-the-city movement: neighbourhood redevelopment and processes of political and cultural displacement. Urban Studies, 52 (10), 1753–1773. doi:10.1177/0042098014539403.

- Hyra, D., 2016. Commentary: causes and consequences of gentrification and the future of equitable development policy. Cityscape; Washington, 18 (3), 169–177.

- Hyra, D., et al., 2019. A method for making the just city: housing, gentrification, and health. Housing Policy Debate, 1–11. doi:10.1080/10511482.2018.1529695.

- Israel, B.A., et al., 2006. Engaging urban residents in assessing neighborhood environments and their implications for health. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 83 (3), 523–539. doi:10.1007/s11524-006-9053-6.

- Koltai, J. and Stuckler, D., 2020. Recession hardships, personal control, and the amplification of psychological distress: differential responses to cumulative stress exposure during the U.S. Great Recession. SSM - Population Health, 10, 100521. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100521

- Kopasker, D., Montagna, C., and Bender, K.A., 2018. Economic insecurity: A socioeconomic determinant of mental health. SSM - Population Health, 6, 184–194. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.09.006

- Krieger, N., 2013. Epidemiology and the people’s health: theory and context. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Kubzansky, L.D., Seeman, T.E., and Glymour, M.M., 2014. Biological pathways linking social conditions and health. In: L.F. Berkman, I. Kawachi, and M.M. Glymour, eds. Social epidemiology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 512–561. doi:10.1093/med/9780195377903.003.0014.

- Lazarus, R.S. and Folkman, S., 1984. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer.

- Lees, L., Slater, T., and Wyly, E., 2007. Gentrification. 1st ed. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Martin, I.W. and Beck, K., 2018. Gentrification, property tax limitation, and displacement. Urban Affairs Review, 54 (1), 33–73. doi:10.1177/1078087416666959.

- Matheson, F.I., et al., 2006. Urban neighborhoods, chronic stress, gender and depression. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 63 (10), 2604–2616. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.001.

- McEwen, B.S., 1998. Stress, adaptation, and disease: allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 840 (1), 33–44. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09546.x.

- Metropolitan Area Planning Council, 2014a. Middle-income housing: demand, local barriers to development, & strategies to address them in select inner core communities. Boston, MA: Metropolitan Area Planning Council.

- Metropolitan Area Planning Council, 2014b. Population and housing demand projections for Metropolitan Boston. Boston, MA: Metropolitan Area Planning Council.

- Metropolitan Area Planning Council, 2019. Red line life science study. Boston, MA: Metropolitan Area Planning Council.

- Modestino, A., et al., 2019. The greater Boston housing report card 2019: supply, demand and the challenge of local control. Boston, MA: Boston Foundation, 121.

- Muñoz, A.P., et al., 2015. The color of wealth in Boston. Boston, MA: Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 35.

- Newman, K. and Wyly, E.K., 2006. The right to stay put, revisited: gentrification and resistance to displacement in New York City. Urban Studies, 43 (1), 23–57. doi:10.1080/00420980500388710.

- Niedzwiedz, C.L., et al., 2017. Economic insecurity during the Great Recession and metabolic, inflammatory and liver function biomarkers: analysis of the UK Household Longitudinal Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 71 (10), 1005–1013. doi:10.1136/jech-2017-209105.

- Nowok, B., et al., 2013. Does migration make you happy? A longitudinal study of internal migration and subjective well-being. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 45 (4), 986–1002. doi:10.1068/a45287.

- Oliveira, B.S., et al., 2016. Systematic review of the association between chronic social stress and telomere length: A life course perspective. Ageing Research Reviews, 26, 37–52. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2015.12.006

- Oscilowicz, E., et al., 2020. Young families and children in gentrifying neighbourhoods: how gentrification reshapes use and perception of green play spaces. Local Environment, 25 (10), 765–786. doi:10.1080/13549839.2020.1835849.

- Pearlin, L.I., 1999. The stress process revisited. In: C.S. Aneshensel and J.C. Phelan, eds. Handbook of the sociology of mental health. Boston, MA: Springer US, 395–415. doi:10.1007/0-387-36223-1_19.

- Pearlin, L.I. and Bierman, A., 2013. Current issues and future directions in research into the stress process. In: C.S. Aneshensel, J.C. Phelan, and A. Bierman, eds. Handbook of the sociology of mental health. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer Netherlands, 325–340. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-4276-5_16.

- Prentice, C., McKillop, D., and French, D., 2017. How financial strain affects health: evidence from the Dutch National Bank Household Survey. Social Science & Medicine, 178, 127–135. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.02.006

- Reardon, T., Philbrick, S., and Partridge Guerrero, J., 2020. Crowded in and priced out: why it’s so hard to find a family-sized unit in greater Boston. Boston, MA: Metropolitan Area Planning Council. Available from: https://metrocommon.mapc.org/reports/10

- Rios, S., 2019, October 9. Developers have discovered Lynn. What comes next? In Bostonomix. WBUR.

- Robinson, D. and Steil, J., 2020. Evictions in Boston: the disproportionate effects of forced moves on communities of color. Boston, MA: City Life Vida Urbana, 108.

- Rohde, N., et al., 2017. Is it vulnerability or economic insecurity that matters for health? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 134, 307–319. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2016.12.010

- Rohde, N., et al., 2016. The effect of economic insecurity on mental health: recent evidence from Australian panel data. Social Science & Medicine, 151, 250–258. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.12.014

- Ross, M. (2014, December 8). Welcome to Chelsea, the new “it” zip. Boston Globe, A.13.

- Saldana, J., 2015. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Schnake-Mahl, A.S., et al., 2020. Gentrification, neighborhood change, and population health: a systematic review. Journal of Urban Health, 97 (1), 1–25. doi:10.1007/s11524-019-00400-1.

- Schulz, A.J., et al., 2008. Do neighborhood economic characteristics, racial composition, and residential stability predict perceptions of stress associated with the physical and social environment? Findings from a multilevel analysis in Detroit. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 85 (5), 642–661. doi:10.1007/s11524-008-9288-5.

- Schuster, L. and Ciurczak, P., 2018. Boston’s booming … but for whom? Building shared prosperity in a time of growth. Boston, MA: Boston Indicators, 48.