ABSTRACT

Community Wellbeing (CW) in the built environment is acknowledged as being ‘greater than the sum of its parts’, a process that emerges when residents negotiate understandings of community within shared spaces. However, methods of evaluation have not caught up. In practice, evaluation methods and frameworks measure CW as an aggregate of individual wellbeing, and operate as a ‘pick and mix’ of dimensions and indicators. Such an approach fails to capture the resident experience as it emerges from (and is shaped by) the local community context. To bridge the gap between theory and practice, we advance participatory mixed methods to integrate CW theory with current building performance assessment methods in support of the development of a novel, evidence-based tool. The first section covers the shift from an aggregate to relational conceptual framework, employing a social practice theory lens to acknowledge how CW emerges from individual and collective interactions. We then situate CW within current building performance assessment methods by reviewing seven CW frameworks. Finally, we recommend improvements to CW assessment based on our own research, including participatory methods, local community engagement, and Photovoice.

Introduction

Recent literature conceives of the development of Community Wellbeing (CW) in the built environment as a dynamic process that emerges when residents interact with their physical environments to negotiate understandings of community within the shared spaces of their buildings (Wiseman and Brasher Citation2008, Atkinson et al. Citation2017). However, in practice, evaluation methods and frameworks continue to measure CW as an aggregate of individual wellbeing, without consideration of the relationships among diverse scales (individual, community, population), dimensions (social, economic, environmental, cultural, political, health), and levels (building, neighbourhood, region) of CW (Coburn et al. Citation2003, Atkinson et al. Citation2017). The problem with measuring and evaluating community wellbeing as an aggregate of individual wellbeing is the failure to capture the resident experience as it emerges from (and is shaped by) the local community context. While conceptually CW is acknowledged as being ‘greater than the sum of its parts’, methods of evaluation have not caught up.

To bridge this gap between theory and practice, this paper turns to social practice theory, which describes collective activities that are co-produced and shared within a population, and further shaped (although not determined) by the material world, such as a building (Shove et al. Citation2012). In relying on social practice theory, we illustrate how these shared practices emerge from engagement – an emergence that can be illuminated by qualitative approaches and analysis. We further review and recommend participatory mixed methods that are used in an attempt to understand the interaction between community and features of the built environment. This understanding is important because the analysis of CW at the building level is novel and can guide how we view and use particular building types such as multi-unit residential, understanding them to be shaping ‘containers’ for collective (and individual) wellbeing.

In this paper, we describe how aggregates of individual wellbeing fail to capture resident experience, and therefore miss out on providing comprehensive evaluations of CW. Our aim for this paper is to integrate CW theory with current building performance assessment methodology to bridge the gap between theory and practice. This research is important because it supports the development of a novel, evidence-based tool. Analysing CW effectively (capturing resident experience) at the building level can help guide how researchers and practitioners evaluate and manage particular building types, such as multi-unit residential buildings. The first section covers how CW is conceptualized in the built environment, and the shift from an aggregated to relational conceptual framework. We then situate CW within current building performance assessment methods, and review seven CW frameworks that aim to integrate relationality into their evaluation in order to identify the gaps between the theory and methodology. By identifying current gaps in CW assessments and recommending participatory mixed methods to address these gaps in analysis, this paper supports the development of an evidence-based tool for capturing resident experience in CW assessments. Finally, we illustrate how using a social practice lens allows us to conceive of the concept of wellbeing as necessarily shared, further demonstrating how wellbeing is dynamic while being temporally- and geographically-bound.

This paper is intended for multidisciplinary researchers and practitioners in architecture, civil engineering, public health, and urban planning, across academic, government, and industry contexts. We acknowledge that our exploration of CW is positioned within the Western knowledge paradigm, as current literature is predominantly published in the Global North. Future research is needed to address CW in Global South settings, but is beyond the scope of this study.

How is community wellbeing conceptualized in the built environment?

Origins of ‘community’ in the wellbeing literature

Individual Wellbeing (IW) is the dominant conception of wellbeing and can generally be defined as a person’s life satisfaction (Atkinson et al. Citation2017, p. 14). This can be evaluated by way of objective indicators, such as income, health or education level, and subjectively through self-perception of life satisfaction. For example, an individual can self-assess whether they feel happy or believe that they are on their way to meeting their life’s potential. Community Wellbeing (CW) shifts wellbeing from an individual property to an inherently collective one. CW, for the purposes of this paper, is a dimension of wellbeing that emerges from a combination of factors (social, economic, environmental, cultural, political) that communities collectively identify and negotiate as essential for flourishing (Wiseman and Brasher Citation2008, p. 258). Current approaches to measuring CW include individual assessments of community scale factors, collection of community scale data, group discussions, and reviewing local policy documents (that target, for example, wellbeing, economic growth, health) (Atkinson et al. Citation2017, p. 14). While CW includes measures of IW, CW itself measures wellbeing at the community scale, moving beyond conceptualizing CW as an aggregate of IW or as a collective term for individual social indicators.

In the conceptual review ‘What is Community Wellbeing?’ (Atkinson et al. Citation2017), the authors argue that attempted assessments of CW conducted by aggregating individual assessments of wellbeing miss the crux of CW, which is what it means to live collectively (p. 16). Instead, these assessments end up capturing ‘population wellbeing’, referring to individual aspects of wellbeing at a population scale. Indeed, population health approaches have been extensively critiqued for their lack of attention to the inherently social production of health and wellbeing (Poland et al. Citation1998, Coburn et al. Citation2003, p. 16). To capture ‘aspects of life of a social grouping as they are lived and experienced together’ (Atkinson et al. Citation2017, p. 14) another approach is necessary. The solution they offer involves assessing community scale activities and resources, such as provision of services or available green space, as well as narratives or case studies of community organizations and their processes, often enlisting the expertise and perspective of community members (p. 6; 16). This approach, they argue, captures what it means to ‘live collectively’ by combining both subjective and objective measures of CW (p. 16). In collecting subjective measures, the authors make a distinction between subjective assessments of the domains of our individual lives (how we feel about our homes, relationships) and subjective assessments of the domain of the collective (how we feel about local safety, mobility; levels of trust in the community) (p. 16). While, for example, subjective data is always an ‘individual expression’, we can collect subjective data that operates at the community scale, such as perceptions of/satisfaction with trust, local safety, local transport, and access to goods and services; (p. 5). This distinction of scale, the ‘domain of the collective’, is a key contribution of Atkinson et al.’s (Citation2017) conceptual review.

Lee and Kim (Citation2015) further distinguish CW from ‘population wellbeing’ to offer a more comprehensive focus on the interactions between individuals who make up a collective; in the case of building-level CW, a ‘geographically bound’ collective. The lack of a clear definition of CW has led to a lack of clarity for researchers about what they are studying when they seek to measure CW, and how best to do it. For example, CW is often used interchangeably with concepts like happiness, life satisfaction, and quality of life (QOL) (Lee and Kim Citation2015). However, CW is multidimensional and more comprehensive than a single indicator can describe. Where a measure like QOL tends to focus on measuring current, fixed capital, CW focuses on a collective’s assets and potential for satisfying present and future needs (Lee and Kim Citation2015, p. 19). The inclusion of ‘aspiration’ (assets that have yet to be capitalized) in analyses of CW indicates that factors of CW may change with a community’s needs and preferences (p. 15).

In other words, wellbeing is dynamic. Morgan et al. (Citation2022) acknowledge the dynamic nature of wellbeing by framing it as a social practice. Wellbeing is understood as an ‘emergent pattern of activity’ learned and adopted by the collective, that accomplishes wellbeing. This approach highlights wellbeing as something that is shared, with changing outcomes across time and space. WB is not achieved through an individual’s actions, rather it is the outcome of an ongoing process of negotiation between the ‘material, social and individual’ (Morgan et al. Citation2022). CW offers an opportunity to expand understandings of wellbeing from an individual to collective property, seeking to capture how people ‘live collectively’ by assessing wellbeing in the ‘domain of the collective’, in addition to that of the individual.

Social practice theory and wellbeing

The literature on wellbeing in the built environment has started to recognize the role of shared spaces in relational processes of place-making. For Wood et al. (Citation2010, Citation2012), and Poldma et al. (Citation2014), the physical accessibility of shared space determines the movement of and between individuals. Through social interactions, individuals attribute personal and collective meanings to space, which are socially constructed. As communities change and new experiences of shared space arise, wellbeing is seen to be a dynamic and interactive process in the built environment. Campbell and Campbell (Citation1988) also describe how positive informal interactions in shared spaces can improve satisfaction with the built environment, in turn improving both individual and collective wellbeing. Raphael et al. (Citation2001) and Francis et al. (Citation2012) add that community structures are necessary to cultivate an overall sense of belonging and connectedness. This sense of community is increasingly facilitated through social media, which contributes to the experience of community structures and spaces (Gatti and Procentese Citation2020, Citation2021). In conceptualizing wellbeing in the built environment, the recognition of social behaviour is then reminiscent of CW frameworks at the neighbourhood and regional level.

These considerations suggest that it may be useful to apply a social practice theory (SPT) lens to the concept of community wellbeing. Instead of conceiving of CW as the ‘combination’ of multiple dimensions, as discussed above, SPT sees wellbeing as emerging from complex interactions of material, experiential and mental phenomena (Schatzki Citation1996, Reckwitz Citation2002, Shove et al. Citation2012). In so doing, it suggests that features of the built environment inform bodily movements, lifestyles, and the formation of community. Wellbeing is thus a relational phenomenon shaped by interactions within and across scales (individual, collective), dimensions (social, economic, environmental, cultural, political, health), and levels (building, neighbourhood, region). The development of a conceptual framework for CW at the building level informed by SPT therefore provides an opportunity to integrate and enrich existing understandings of wellbeing, in ways directly connected to the physical affordances of the built environment. We see this as consonant with a broader ‘relational turn’ in social science and sustainability science (West et al. Citation2020).

A SPT lens thus represents a change in how agency is conceived (Reckwitz Citation2002, Shove et al. Citation2012). The locus of agency shifts from a purely individual level to a more collective . In other words, seeing CW as not simply an aggregate of individual WB measures but as something that exists and operates at a different level. Just as the sum of individual wellbeing measures do not provide an adequate description of CW, so the sum of individual behaviors does not provide an adequate description of social practices. Agency goes beyond individual intentionality to take on an emergent collective characterFootnote1 (Reckwitz Citation2002, Shove et al. Citation2012).

Social practice theory (SPT) therefore offers a novel and fitting lens with which to conceptualize individual and community wellbeing. The theory is constituted by a suite of approaches to understanding human activity, that rely on understanding human activities as collectively shared practices. These activities are co-produced dynamically between people, in constant negotiation and co-creation of ‘what is normally done’, across different times and geographic regions (Slater and Robinson Citation2020). As such, the theory is sociologically based, and the normative activities or practices undertaken are always culturally relevant.

There is an important distinction between personally held preferences or habits, and socially enacted practices. An individual preference for taking the stairs in their building and then doing so regularly indicates a personal habit. A preference for stair-taking in the context that it is widely understood as an option, sanctioned and practiced by others, indicates that taking the stairs is a social practice that may be valorized (e.g. as ‘healthy’ or ‘environmentally conscious’), but perhaps also as more ‘efficient’ for just one or two floors if elevator waits are long, or considerate of others in some contexts. Similarly, the desire to attend an annual summer community BBQ indicates a personal preference, as it reflects a habitual effort to engage in broader social life, sometimes with strangers present. But that a community BBQ is ‘a thing to do’—something that is normal, expected, and sanctioned, and replicated in a neighbourhood (city/culture) on a seasonal basis – indicates that it is a social(ly accepted) practice. Everyone has preferences and habits, that may or may not align with broader social practices. Meanwhile everybody that is a part of a given social fabric knows ‘what is normally done/what can be done’ in a given context, whether they want to engage in that activity or not (Morgan et al. Citation2022, forthcoming). Nor do we mean to suggest that individual preferences are pre-given/pre-constituted and then subsequently ‘rub up against’ social practices, but rather that the two are dialectically co-produced.

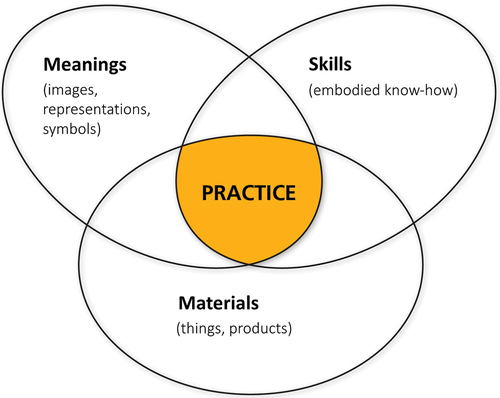

Social practice theory is less a unified theory than a perspective rooted in the work of Bourdieu (Citation1990) and Giddens (Citation1984), and while there are several descriptive models of social practice, the one we use is derived from Shove et al.’s (Citation2012) tripartite model, in which a practice is comprised of three elements: skills, meanings, and materials. (See ). For example, the social practice of opening a window first requires three things: the window itself and the available material object that is a lever with which to open it; the skill or know-how that this lever allows the window to be opened; and the meaning, symbol or idea of opening a window: that it brings in fresh air, or even more abstractly, that doing so might evoke a sense of ‘taking a breather’, or bolster health. For window-opening to be a social practice – an activity that is widely reproduced and generally, practiced without much deliberation – these three elements become unconsciously integrated, so that opening a window is the normal thing done when needed.

Figure 1. A tripartite model of social practices. Inspired by Shove et al.’s tripartite SPT model (Citation2012).

In this approach, wellbeing can emerge from the human activities that arise from the interaction of these elements. Wellbeing does not exist independently of those elements or activities, nor does it arise from the simple sum of individual beliefs and actions. WB meanings do not, by themselves, give rise to CW practices. A practice, characterized as wellbeing, will not lead to CW unless materials and skills are present and acted upon, making CW a property that emerges from the interaction of all three of the SPT framework’s components. However, as meanings change (think of smoking, originally thought of as a liberating practice), practices can fall ‘out of fashion’. Meanings change first (e.g. awareness of the health impacts of smoking, to self and to others), but the practice of smoking doesn’t change until skills (how to use smoking substitutes or other ways of coping) and materials (bans on smoking in certain places) also change. This is how the elements of a non-smoking practice – the meanings, skills and materials – become normalized and a new form of CW emerges. In fact, smoking was actively discouraged through changes in material contexts (e.g. banning of smoking in buildings). The Venn diagram in shows that practices can be described by the three elements of materials, skills and meanings. Relevant to this paper, (community) wellbeing emerges from the performance of a given social practice.

One important contribution from SPT to the study of wellbeing is that activities from which wellbeing might emerge are always collectively ‘curated’. For example, we can envision community wellbeing as (a) a desirable, generally positive state of being that (b) can be pursued and accessed (c) via enacting various culturally sanctioned activities (meditation, volunteering, getting outdoors, baking, self-care, gardening, socializing, etc.). Some theorists have referred to a fairly recent ‘wellbeing turn’ (Smith Citation2019): expecting a sense of wellbeing, as a desired quality, that is achievable through such everyday life activities, is simply one feature of that turn. A SPT-based approach to wellbeing understands human activity to be collectively shared practices that are co-created by a group of people who share a space, shifting agency from purely individual to a collective level. Conceiving of community wellbeing as a relational phenomenon shaped by interactions provides us with the conceptual tools to begin to imagine how the built environment informs the formation of community (West et al. Citation2020). The development of a conceptual framework for CW at the building level informed by SPT therefore provides an opportunity to integrate and enrich existing understandings of wellbeing, in ways directly connected to the physical affordances of the built environment.

Relationality: the building as an agent

For CW, SPT provides a powerful foundation to reimagine community through collective relationships with the built environment. Current frameworks tend to conceptualize and measure CW at the neighbourhood and regional level (Christakopoulou et al. Citation2001, Miles et al. Citation2008, Cox et al. Citation2010, Buot et al. Citation2017, VanderWeele Citation2019), rather than the building level. The built environment is often overlooked and assessed as only one dimension of CW, the environmental dimension, without capturing its role in other dimensions. As multi-unit residential buildings (MURBs) continue to rise in cities (Reeves Citation2020), recognizing how the built environment is experienced in these buildings is central to individual and community wellbeing. Reeves (Citation2020) points to the new concepts of community – and therefore CW – that emerge from rethinking space as being beyond public or private. For example, common areas in MURBs are hybrid public-private spaces. MURBs offer a rich case study for assessing CW, observing, at the building-level, how collectives engage with their material surroundings to negotiate wellbeing in hybrid (private and shared) spaces.

At the start of the 1990‘s an intellectual movement, the ‘spatial turn’, occurred, which shifted perception of space from static to dynamic (Fuller Citation2017, p. 605). Space became understood as being constituted through the arrangement of bodies and objects and the process of attaching meaning to a particular space (p. 605). The spatial turn revealed the relationality of space, how a place changes when collective shared meaning of it changes. In the words of sociologist Martin Fuller, ‘the built environment is rendered knowable through shared ideas’ (p. 608). Fuller (Citation2017) study of resident leadership in a housing collective highlights the process of community building through negotiating boundaries between private and shared spaces. Fuller examines a MURB under construction in Berlin to show how material objects become loci of meaning making through participatory planning. Associated with this MURB is a housing collective, a ‘Baugruppe’, that owns and manages a third of the building’s units. The Baugruppe is ‘a group of people who collectively plan and finance a new building’ (commonly a multi-unit, residential one) (Fuller Citation2017, p. 604). Involved in the planning of certain aspects of the building (an information hut, raised flowerbeds, and interior windows) the residents negotiated the future community of their building through object-related decision-making. This facilitated the ‘active production of relational space’ through concrete activities the residents engaged in.

When seen through a SPT lens, the shift to a building-level analysis also provides a more relational approach to CW. In their 2016 article ‘Structuring of Wellbeing’, Lee and Kim propose the concept of relationality as a distinct approach to measuring CW. This distinction was prompted by a perceived failure of objective and subjective aspects to capture the collective characteristics of CW, with objective aspects failing to reflect input from community members, and subjective aspects being too individualistic. An intersubjective approach attempts to capture the collective characteristics of CW by collecting data from individuals without having the individual characteristics overshadow the collective ones (Lee and Kim Citation2016, p. 14). Echoing Atkinson et al’.s ‘domain of the collective’, this is accomplished by employing community indicators, as opposed to individual indicators, which include measurements of local trends relating to environment, social and economic aspects, or data used to measure progress of an area over time (p. 18). Consistent with an SPT lens, a relational approach to CW focuses on social practices rather than individual behaviours.

Housing is, therefore, an ‘activity’, and a building a shaping ‘container’ for community. As part of the City of Toronto’s Tower Renewal Project, Toronto Public Health’s ‘Towards Healthy Apartment Neighbourhoods: A Healthy by Design Report’ suggests that MURBs may become ‘community focal points’ for social interactions, economic activity, and health promotion (Toronto Public Health and the Centre for Urban Growth and Renewal Citation2012), as depicted in Fuller’s explanation of the Baugruppe (Fuller Citation2017). The built environment can affect these aspects of community life by influencing residents’ levels of physical activity, social interactions, safety and access to services. Modifications to the built environment can improve CW by re-designing spaces with the intention of providing residents with a sense of ‘convenience, usability and security’, increasing opportunities for gathering, reducing hazards and animating spaces (Toronto Public Health and the Centre for Urban Growth and Renewal Citation2012). Adding an explicit SPT dimension points us towards the social practices that might be consistent with such social interactions, economic activities, and health promotion campaigns, and which in turn could be fostered by specific design decisions.

CW exists at multiple levels, dimensions, and scales. A shift towards the building level can therefore capture the active role of the built environment in shaping community. The building becomes an agent within and around which social practices can form, in turn leading to the emergence of wellbeing. CW frameworks must then recognize both individual and collective relationships with the built environment in conceptualizing and measuring CW.

From CW theory to method and measurement

A common, multidimensional framework

Current frameworks tend to conceptualize and measure CW multidimensionally. Since the social indicators movement in the 1960s, Lee and Kim (Citation2015) and Wiseman and Brasher (Citation2008) describe the trend towards a ‘comprehensive picture’ of CW (p. 360), in the form of a single composite index or a suite of indicators. CW becomes the combination of indicators across multiple dimensions, an effort to broadly capture the determinants of CW (Wiseman and Brasher Citation2008, Lee and Kim Citation2015). For our study, we identified seven multidimensional frameworks that are relevant to assessing CW through SPT: those of Christakopoulou et al. (Citation2001), Miles et al. (Citation2008), Cox et al. (Citation2010) Lee et al. (Citation2011), Buot et al. (Citation2017), Markovich et al. (Citation2018), and VanderWeele (Citation2019). We conducted an open search in Scopus and ProQuest, two interdisciplinary databases, followed by the snowball method with sources from our team’s experience. Keywords included ‘community wellbeing’, ‘measurement’, ‘assessment’ or ‘evaluation’, and ‘framework’. To focus on current conceptions of CW, frameworks for general wellbeing, quality of life, and related constructs (e.g. community resilience, community integration, social inclusion) were excluded. We included only frameworks that distinguished CW from these constructs, most notably by looking at the multiple scales, dimensions, and levels of CW. As an exception, Lee et al.’s (Citation2011)wellbeing index for super tall residential buildings (STRBs) was retained to provide a building-level example that captures the role of community spaces. CW frameworks were filtered to those with three or more dimensions to represent the aforementioned ‘comprehensive picture’ of CW. Our final selection does not aim to capture every CW framework that exists, but highlights cases that represent the current multidimensional trend. Each framework embraces multiple dimensions of CW as a necessary departure from one-dimensional measures such as the GDP (Miles et al. Citation2008, Lee and Kim Citation2015), but no common method exists. provides a comparison of CW methods according to their conceptual approach, scale, scope, dimensions, and data type and source.

Table 1. Measuring community wellbeing: methods across frameworks.

The multidimensional trend in CW frameworks is shifting towards localized, community-engaged dimensions and indicators. CW frameworks tend to be place-based,they rely on the belief that the environments we inhabit influence our habits and relationships (Shove and Pantzar Citation2005), with a focus on the neighbourhood and regional level. Of the seven selected frameworks, only two are dedicated to conceptualizing and measuring CW at the building level: the Wellbeing Index for STRBs (Lee et al. Citation2011) and the Community Wellbeing Framework for Design Professions (Markovich et al. Citation2018). The remaining frameworks connect CW more broadly to local development, suggesting that CW is best defined by individuals and communities according to the ‘conditions’ that are seen by them as ‘essential for them to flourish and fulfill their potential’ (Wiseman and Brasher Citation2008, p. 358). Locally driven CW frameworks have become the subject of regional and national government interest in Australia, Canada, and the UK since the early 2000s (Wiseman and Brasher Citation2008, Cox et al. Citation2010), which have encouraged participatory methods of conception and measurement. Across four of the five frameworks at the neighbourhood and regional level, CW has integrated community engagement through short- and long-term methods, such as community consultations, pilots of the framework, and retrospective review and revision (Christakopoulou et al. Citation2001, Miles et al. Citation2008, Cox et al. Citation2010, Buot et al. Citation2017). Six-by-Six Community Wellbeing (Miles et al. Citation2008) and Community Indicators Victoria (Cox et al. Citation2010), in particular, emerged as local partnerships for CW. At the building level, participatory methods are also present, which raises questions about the compatibility and feasibility of applying neighbourhood and regional level methods to the building, particularly in the long-term, such as defining community within and around the building, maintaining relationships with the building’s community, and opportunities for making changes to the framework over time.

When connecting/applying CW frameworks that are designed for the neighbourhood and regional level to the building level, considerations therefore arise. Current frameworks at the building level provide limited guidance. Among our selection of frameworks, Lee et al.’s (Citation2011)wellbeing index for STRBs measures Individual Wellbeing more than CW, while Markovich et al.’s (Citation2018) Community Wellbeing: A Framework for the Design Professions provides a ‘concrete’ approach that integrates common building performance assessments, but has not yet been validated beyond a select number of pilots. The next section explores key considerations for conceptualizing and measuring CW at the building level, informed by SPT.

A review of CW methods across frameworks: six considerations

Multiple dimensions – but which ones?

A multidimensional approach to CW must consider how dimensions and indicators are selected for inclusion. The frameworks in show variation in the choice of dimensions, as well as how each is measured. The environmental dimension of CW, for instance, is recognized across six of the seven frameworks, while the social dimension is included in all. Between frameworks, certain dimensions are differently named and may be grouped together. For example, in Community Indicators Victoria, ‘Healthy, safe, and inclusive communities’ captures both the environmental and social dimensions of CW (Cox et al. Citation2010). Within each dimension, the corresponding indicators also vary in number and focus. Miles et al.’s (Citation2008) Six-by-Six framework proposes six dimensions with six indicators each, while Cox et al. (Citation2010) and Markovich et al. (Citation2018) are more expansive.

Without guiding dimensions and indicators for CW, a multidimensional approach presents the risk of a reductive, ‘pick and mix’ approach (Hanc et al. Citation2019, p. 779), as well as the favouring of certain dimensions over others. In Miles et al.’s (Citation2008) Six-by-Six Community Wellbeing framework, a group of Australian researchers piloted a study in Central Queensland that sought to ‘identify sustainable indicators of community wellbeing’ (Miles et al. Citation2008, p. 73). At the neighbourhood and regional level, Miles et al. (Citation2008) note the potential bias towards socioeconomic indicators due to the connection of CW frameworks with local development. At the building level, Hanc et al. (Citation2019) also note the bias towards environmental quality, satisfaction, and comfort. A balance needs to be considered between the pre-determination of CW and adapting dimensions and indicators to a specific community’s social practices. Limiting frameworks to pre-determined dimensions assumes that CW is the same across communities, rather than a reflection of their local context. However, CW frameworks should also capture change over time, while allowing for comparison between communities.

Participatory methods can begin to address reductionist frameworks of CW by including communities in the selection of dimensions and indicators. Five of the seven frameworks identify and validate CW dimensions through preliminary surveys (Miles et al. Citation2008, Buot et al. Citation2017) and community consultations, which include local residents, elected representatives, and academics and building professionals. Three of these five frameworks further attempt to retrospectively review and revise the final selection of dimensions (Miles et al. Citation2008, Cox et al. Citation2010, Markovich et al. Citation2018), although the process is not consistent nor formalized. CW assessments must be localized, but the extent to which dimensions and indicators can feasibly be localized, especially over time, presents another consideration: how community participation is defined.

Defining community participation

Insofar as community participation can inform the selection of CW dimensions and indicators, the depth and breadth of participation must be considered. Beyond the early stages of identifying dimensions and indicators, current frameworks do not consistently include communities as partners in the sense-making of collected measures, nor their retrospective review and revision. Although six of the seven frameworks in build on community input, no clear, common approach exists for operationalizing meaningful participation. As CW is shaped by social practices, methods to capture the diversity of lived experiences are needed to demonstrate how CW varies within and between communities. Since CW emerges from local community contexts, which are diverse, frameworks need to be able to capture these changes over space and time.

Principles for community participation in CW frameworks include circularity/reflexivity, community ownership, and relationship-building. Miles et al.’s (Citation2008) Six-by-Six Community Wellbeing proposes stakeholder consultation at each stage of the framework’s development, review, and revision, but methods do not detail the selection of community members, relative to other stakeholders, nor the process of analyzing community input to inform dimensions and indicators. Markovich et al.’s (Citation2018) Community Wellbeing Framework for the Design Professions also suggests stakeholder engagement to ‘maximize’ community ownership (p. 133), but again fails to provide inclusion and exclusion criteria for participants, the frequency of engagement, and methods for integrating community input. Community Indicators Victoria seeks to build long-term community partnerships through an online database, where communities identify, monitor, and provide feedback on indicators and their methodology; the framework becomes ‘more than local data sets’ (Davern et al. Citation2017), a feedback mechanism to shape CW. However, the extent to which input is collected and integrated is also unclear, and Cox et al. (Citation2010) note the financial limitations to sustaining a system of local community indicators.

CW frameworks require clear, consistent methods for meaningful and sustainable community participation. It should also be noted that most geographic ‘communities’ are not monolithic but instead comprise multiple social strata and communities of interest. Few frameworks attempt to explicitly grapple with the full socioeconomic and perspectival diversity of communities, with most assuming that ‘the community’ somehow speaks with one voice. Of the seven frameworks, Six-by-Six Community Wellbeing, Community Wellbeing Framework for the Design Professions, and Community Indicators Victoria included the most participatory methods, but did not define ‘community’ beyond its distinction from academic, government, or professional stakeholders. Without formal recognition of the diverse nature of community, current frameworks should consider if diverse lived experiences of CW are truly represented/included. A third consideration arises: the role of subjective and objective indicators in capturing these lived experiences.

Subjective vs objective indicators: CW across scales

Multidimensional frameworks should consider how subjective and objective indicators contribute to a ‘comprehensive picture’ of CW (Wiseman and Brasher Citation2008, p. 360). Among the seven frameworks, Lee et al.’s (Citation2011) wellbeing index for STRBs and VanderWeele’s (Citation2019) Community Wellbeing Template measure only subjective indicators, with a focus on individual satisfaction. The remaining frameworks combine subjective and objective indicators, bringing into question the role of each type of data. For Lee (Citation2008), satisfaction and other subjective indicators capture how CW is perceived, with wellbeing seen to originate from personal attitudes, beliefs, and feelings (Lee et al. Citation2011). An equally important role can be suggested for objective indicators: capturing the social practices that shape CW. For example, a subjective indicator such as ‘Feeling part of the community’ can measure how social connectedness is perceived (Cox et al. Citation2010); an objective indicator like the frequency of informal interactions can inform how connectedness arises. Objective indicators ‘ground’ subjective indicators in the context of each CW dimension to understand how it is experienced. Of course, ‘objective’ data are actually more subjective than is usually acknowledged, but here we distinguish individual perceptions from interactions with their context, whether ‘hard’ (e.g. material context) or ‘soft’ (e.g. social, political, cultural contexts).

Both subjective and objective indicators can risk favouring individual over collective understandings of CW (Lee and Kim Citation2016). For subjective indicators, VanderWeele (Citation2019) suggest reframing measures of satisfaction from individual behaviours to social practices. As an example, the Community Wellbeing Template asks residents to self-rate agreement with the statement ‘Everyone in the community trusts one another’, rather than ‘I trust everyone in the community’ (VanderWeele Citation2019). This focus on social practices is consistent with SPT, although individual and collective indicators should be considered as complementary, rather than interchangeable. For objective indicators, Lee and Kim (Citation2016) suggest the measurement of local trends in each dimension. In current frameworks, objective indicators measure CW at the individual (e.g. household income), community (e.g. neighbourhood crime rate), and population scales (e.g. employment rate), which inform how individual and collective contexts can interact to shape CW.

A subjective and objective, mixed scale approach to CW indicators provides a holistic representation of CW as a lived experience. Current and future frameworks may consider if there is an ideal balance between subjective and objective, and individual and collective indicators. Moreover, frameworks should consider how indicators are assessed. For instance, Markovich et al.’s (Citation2018) Community Wellbeing Framework for the Design Professions includes more objective indicators at both the individual and collective scales, but the criteria to assess each indicator is still subjective, which can limit how much of the built context is captured. Understanding how CW is not only perceived, but shaped by interactions with individual and collective contexts is particularly relevant to the building level. A fourth consideration arises: how individual and collective relationships with the built environment contribute to CW.

Relational interactions in the built environment

At the building level, current frameworks should consider how CW emerges from individual and collective interactions with features of the built environment. Among the seven frameworks, Lee et al.’s (Citation2011) wellbeing index for STRBs and Markovich et al.’s (Citation2018) Community Wellbeing Framework for the Design Professions integrate the built environment in indicators across all dimensions. In contrast, the remaining frameworks address the built environment within the environmental dimension alone, while limiting indicators to safety, security, and comfort. The environmental dimension of CW, more discrete, is distinct from CW in the built environment as a whole. For instance, the built environment closely overlaps with the social dimension. Discrete indicators such as the self-rated strength of informal interactions (Christakopoulou et al. Citation2001) fail to recognize the material context in which social practices arise. Integrated indicators may include satisfaction with shared spaces (Lee et al. Citation2011) and perceived access to social gathering spaces (Markovich et al. Citation2018). Without integrating the built environment across dimensions and indicators, it is not clear if and how a strong environmental dimension reflects or relates to other dimensions of CW, and vice versa.

Building-specific methods can demonstrate how the built environment shapes social practices towards CW. Markovich et al. (Citation2018) assess built features that are conducive to social practices. For example, their framework uses building plans and drawings to determine if building frontages are welcoming, and if lighting design and placement promotes a sense of safety. However, if these indicators are objective, the criteria to assess each indicator is subjective. It is also not clear if such data sources are interpreted through participatory methods, which limits CW from capturing how individuals and communities actually interact with the built environment. The framework may benefit from extending community participation from framework development and revision to data collection.

Participatory methods at the building level are required to recognize the relational nature of CW between individuals and communities and their built environment. CW frameworks call for greater attention to the built environment beyond the neighbourhood or region levels, beyond a single dimension or indicator. This presents a fifth and final consideration: how CW is considered as a whole, equal to or greater than the sum of multiple scales (individual, community, population), levels (building, neighbourhood, region), dimensions (social, economic, environmental, cultural, political, health).

Is the whole greater than the sum of the parts?

A multidimensional approach needs to consider how CW is interpreted as a whole. Current frameworks propose an aggregate measure of CW, the addition of multiple dimensions, without considering the relationships between dimensions. Five frameworks measure each dimension as a suite of indicators, without clear methods to combine indicators within dimensions, nor compare between dimensions. Two frameworks measure a composite index, based on the relative weighting of each dimension at a singular point in space and time (Lee et al. Citation2011, Buot et al. Citation2017). Christakopoulou et al. (Citation2001) suggest that this discrete approach is practical for data collection and analysis, as well as the profile of a community’s overall strengths and weaknesses. However, for VanderWeele (Citation2019), while CW is not independent of the sum of each part, it also extends beyond multiple scales, dimensions, or levels. Wiseman and Brasher echo the need for an ‘ecological’ understanding of CW to unravel its closely interconnected nature, including the interactions between each part, and achieve a truly ‘comprehensive picture’ (p. 360).

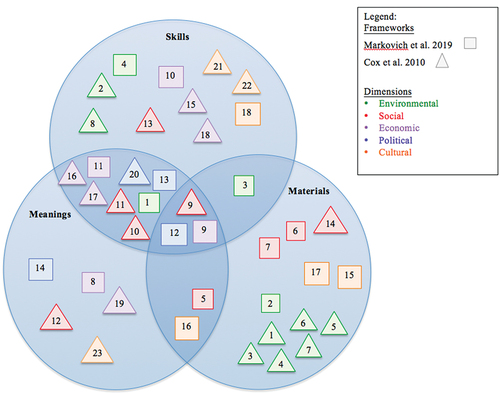

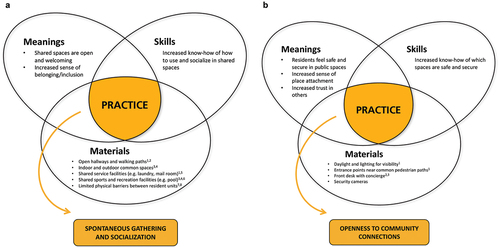

The tripartite model of SPT provides an alternative to look at CW through skills, meanings, and materials, as opposed to scales, dimensions, and levels. A mapping exercise of CW indicators can demonstrate how CW emerges from the interaction of all three SPT elements, becoming greater than their sum. For example, shows how Markovich et al.’s (Citation2018) indicator ‘access to spaces for spontaneous, informal, creative enjoyment’ brings together the know-how of socializing (skill), a sense of welcoming and belonging (meaning), and shared spaces (material) to produce the social practice of spontaneous gathering and socialization, from which CW can emerge. As well, ) shows how Lee et al.’s (Citation2011) indicators of ‘security against crime’ and ‘safety of public space’ bring together the know-how of safety and security (skill), a sense of place attachment and trust (meaning), and open spaces (material) to produce the social practice of community connections.

Figure 2. What are the skills, meanings, and materials that bring about CW?

The tripartite model can further map CW indicators between frameworks to demonstrate if social practices are captured. In an assessment, this tool can be used to illustrate community examples of an indicator. In both research and community work, a team can take a single indicator and complete the Venn diagram accordingly. This exercise does not need to be undertaken by professionals of the built environment. The model is useful insofar as it provides practitioners an opportunity to map out how CW emerges in their local contexts. ( is an example of mapping indicators from two popular CW frameworks: Markovich et al.’s (Citation2018) building-level Community Wellbeing for Design Professions Framework, represented by square data points, and Cox et al.’s (Citation2010) regional level Community Indicators Victoria, represented by triangles. Each data point corresponds to an indicator, matched to the table that follows, and points are colour coded according to their CW dimension (environmental, social, economic, political, cultural). While this mapping exercise is does not include all seven frameworks, it provides a starting point to show how CW frameworks can be compared through SPT. The distribution of indicators suggests that more indicators at the building level from Markovich et al.’s (2019) framework capture the overlap between skills, meanings, and materials, in comparison to Cox et al.’s (Citation2010) framework at the regional level. The indicators at the centre of the Venn diagram could perhaps also be considered ‘ideal’ for representing CW in relation to the built environment.

Applying SPT allows for a holistic interpretation of CW as the interaction of skills, meanings, and materials, beyond the sum of multiple scales, dimensions, and levels. Shifting from an aggregate, additive approach can capture the interactions that shape CW, which extends the locus of agency from the individual to the collective, and therefore allows for emergence. The tripartite mapping exercise calls for more guidance to integrate SPT in existing frameworks, draw conclusions about how indicators correspond to each of the three SPT elements, and, overall, translate SPT from theory to practice.

Capturing change: CW over space and time

Together, considerations for CW frameworks point to the need to recognize and accommodate change over space and time. CW is not static, however there are practical trade-offs to a highly localized, longitudinal study of CW for each community. When selecting dimensions and indicators, participatory processes of consultations, pilots, and retrospective review and revision require time. Cox et al. (Citation2010) also note the financial costs of this long-term maintenance. The extent to which frameworks may change could also prevent comparisons of CW if measures are not consistent between communities, as well as for the same community over time. In the balance between specificity and universality, additional considerations are required to continue to capture diverse lived experiences of CW in interaction with local, individual and collective contexts. Potential methods could be to limit the adaptability of CW frameworks to a certain number of dimensions and indicators; plan for retrospective review over a longer, but still regular timeline (e.g. every five years); and integrate community participation with existing processes, such as those conducted by government. From theory to practice, practicality therefore calls for the assessment of costs and benefits for CW methods.

Connecting CW to building performance assessment

Across CW frameworks, the six considerations explored in our study reflect broader trends in building performance assessment. Current methods in building performance assessment are evolving from objective measures of performance to include measures of how the built environment is experienced. For instance, Coleman et al.’s (Citation2018) regenerative sustainability approach proposes process outcomes, alongside traditional performance outcomes, to bridge the gap between the lived and measured experiences of building occupants. Process outcomes refer to how people engage with the building, while performance outcomes tend to be limited to specific, objective measures such as air quality, energy consumption, water consumption, etc. In residential buildings, Moser’s concept of person-environment congruity similarly evaluates the alignment between objective environmental features and subjective resident needs, taking into consideration the individual and collective context of built environments. For Amaratunga et al. (Citation2002), mixed methods are necessary to capture and connect meaning in building-level research: understanding the ‘life-world’ of occupants, beyond the objective features of the built environment (p. 25). Qualitative methods such as pre- and post-occupancy evaluations can complement the traditionally quantitative performance of buildings to shift the focus towards people. As the ‘wellbeing in buildings revolution’ advances (Hanc et al., p. 768), mixed methods reflect the complexity of defining, then measuring, wellbeing within diverse local contexts (Syhlonyk and Seasons Citation2020).

For CW, emerging approaches in building performance assessment can begin to inform the new relational measurement of wellbeing in the built environment, centering individual lived experiences. Beyond building performance assessment, SPT provides a relational lens to further locate agency at a collective scale, drawing attention to the social practices from which CW is emergent.

What methods can improve the assessment of CW in the built environment?

There are a variety of approaches that can be integrated into practice to improve the assessment of CW in the built environment. Two examples include the use of participatory methods – such as surveys, interviews, and observational approaches – and the engagement of the local community and local governance structures. We also introduce Photovoice as a novel tool to engage residents in CW assessment and connect back to local governance mechanisms.

Participatory methods: including residents in processes of evaluation

Participatory methods are research practices that include residents in the development, sense-making and validation processes of the evaluation tools taken up by a project. Understood as an intersubjective, relational dimension of wellbeing, attempts to assess CW should strive to be engaging, ‘iterative’ processes that include residents throughout the project. For example, at the University of British Columbia’s flagship net-positive living lab, the Centre for Interactive Research on Sustainability CIRS), occupants could engage as participants in research on the building itself. One study (Coleman Citation2016) sought to understand the impact of moving into a novel built environment, on the development of ‘new normals’ in occupant health, productivity and wellbeing. Surveys and interviews were conducted prior to moving into the building, and again after (Pre-to-Post-Occupancy Evaluation or PPOE). Unusually for building projects, potential occupants were engaged in a workshop about the design goals and building tour before moving in, and they were also provided compelling narratives about the regenerative features of the building. Occupant expectations of the building’s features and performance were high, but these were offset by occupants’ forgiveness of perceived shortcomings and differences (Coleman and Robinson Citation2018). Potential new normals – social practices – were identified within tenant groups as developing due to context (including climbing the conveniently-placed stairs instead of the elevator; using headphones or leaving open spaces to have conversations; or greater recycling rates in the building compared to a conventional building (Wu et al. Citation2013). The effort to engage occupants before, and during occupancy, using multiple participatory and somewhat longitudinal methods, aided in a more rounded evaluation that offered a richer description of occupancy and social practices in-situ, going beyond typical post occupancy surveying.

Accordingly (and as mentioned in ), examples of participatory methods include the use of surveys, interviews and observational approaches. A first example of participatory methods are surveys. In the Six by Six Community Wellbeing framework, Miles et al. (Citation2008) identified an over-reliance on planning bodies (local and state governments) using empirical measurements of wellbeing, such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP) indicating economic capital, to evaluate CW (p. 79). In response they distributed a survey instrument concurrently with a local government customer satisfaction survey to a sample of approximately 400 households. The survey consisted of three sections: customer satisfaction, self-reported wellbeing, and demographics (p. 81). In their analysis they contrasted this community survey data with government census data (p. 88). They highlight the need to broaden the working definition of wellbeing to include non-material aspects of CW, to build upon existing understandings of social capital, and to benchmark the values of social participation (p. 79).

Interviews are a second, indispensable qualitative tool insofar as they put emphasis on people’s lived experience and help contextualize and make sense of quantitative data. They are useful for supplementing and re-interpreting quantitative analysis, and, as such, are useful for validating research in the built environment (Amaratunga et al. Citation2002, p. 22). Interviews allow residents to describe their ‘life worlds’ and for researchers to gather descriptions of resident experiences of the built environment. Putting a twist on the traditional interview, two pilot studies were conducted in the Alexis Nihon Mall in Montreal, Canada (Poldma et al. Citation2014). The researchers used a collaborative, action-research approach to centre the lived experiences of participants, using ‘live conversational walk-throughs’ (p. 211) to record participants’ impressions and narratives of the space in real time. The goal of these pilots was not focused on wellbeing, but understanding the participants’ social experiences of the built environment, the relationship between the ‘social construction of space’ and the ‘personal lived experiences’ of participants (p. 207). However, this pilot method emphasizes collaboration by proceeding with ‘investigators and participants interacting in the research process together’, an approach that could offer rich insight for measuring wellbeing in the built environment (p. 210).

A final example of a participatory tool is the observational approaches Huang (Citation2006) used to identify the activities of residents. Investigating the relationship between the courtyard design of high-rise housing complexes in Taipei, and residents’ social interactions with each other, Huang employed observational templates and site plans to record her observations. Before observations began, inventory was taken of the spaces to log space types and design elements (Huang Citation2006, p. 197). The observational sheets were site plans with five space-types (seating, circulation) and ten design elements (route, open areas, play areas, plants) sketched on (p. 202). Additional context was provided for the observations in the form of participant demographics and statistics on typical movement flow, location activity and activity type (p. 198). Observations of the number and position of residents and their activity type (necessary, optional, social) were then logged, and a ‘percentage of social interaction’ was calculated by the ratio between the number of interactions in the courtyards and the number of total observations. Placing an emphasis on resident ‘activity’ frames spaces as ‘interactional’ arenas and recognizes lived experience as a dimension of wellbeing worthy of being included in assessments of CW.

Community engagement: local governance and community development initiatives

Beyond involving participants in the process of CW data collection, local community engagement means that CW measures are attuned to local contexts. Local community engagement involves the integration of CW assessments with local governance and community development initiatives. To be sensitive to local priorities and goals, CW should be integrated within broader community development efforts. In relational and practice-based measures of wellbeing, it is important to establish a common framework of concepts and measurements that can be re-applied to local contexts. Cox et al. (Citation2010) describes CW indicators as ‘statistical tools for translating broad community goals into clear, tangible and commonly understood outcomes’ (Cox et al. Citation2010, p. 72). A SPT lens suggests adding material and skills-oriented dimensions to such goals. It is through the intersection of these three dimensions (skills, meanings, and materials) that CW will be enacted. In deciding CW indicators, there is a need to explore how citizens, community organizations and representatives are engaging in relationships and dialogue with one another (Cox et al. Citation2010, p. 73), and with the built environment. Key steps in establishing systems for identifying local CW indicators include partnership between community development practitioners and governing bodies, identification of appropriate data sources, and the design and implementation of strategies that build capacity for citizen engagement in the identification of such indicators (Cox et al. Citation2010, p. 80). These steps aid in fostering effective linkages between community wellbeing indicator data and relevant policy making processes.

In the 2019 article, ‘Cultivating Community Wellbeing’ (2019), the authors propose that CW indicators should be guided by the principles of ‘purpose, place, and relation’ (Cloutier et al. Citation2019, p. 1). These principles were chosen through applied research and conversations within the discipline. This approach encourages ‘principle-based interactions’ over ‘metric-driven interactions’, such that CW contributes to asset-based community development. Principle-based interactions are defined as community development efforts that are driven by the desire to foster greater connectivity and resilience within a space and its community. The result is an Assets Based Community Development (ABCD) approach to assessing CW, which offers a framework for incorporating both internal/external environments by beginning with a ‘community-led inventory’ of assets (gifts, talents, skills) at the individual, organizational and community levels, followed by a discussion of community needs; assets and needs are then matched (p. 5). ABCD harkens backs to Fuller’s study of the Baugruppe, where residents held a central role in the continued planning and ownership of shared spaces. Described as ‘participatory building’, the existence of the Baugruppe placed agency in the residents to identify and match their community’s assets and needs (Fuller Citation2017). Adding a material component to the assets and needs would tie the analysis back to the specific material affordances of the built environments in which CW is being enacted.

In ‘From National to Local’, Smale and Hilbrecht (Citation2017) outline guidelines for community engagement based on the Canadian Index of Wellbeing’s (CIW) pilot of the Community Wellbeing Survey. This pilot survey asks randomly selected members of a community, ages 16 and over, to rate their perceived (individual) wellbeing over a range of subjective questions that cover eight identified domains of wellbeing (including environment, leisure and culture, community vitality, and so on). In the study, Smale and Hilbrecht sent out a self-administered questionnaire (CIW Community Wellbeing Survey) through an online form and a mail-back option. Their pilot study showcased the use of public data sources that pop up in several of the CW frameworks. Community partners, such as municipal governments and community foundations, administer these surveys as part of larger community outreach programs. Following the survey, an initial report is provided to each community partner with details of the results for each domain, measures of wellbeing and a demographic of residents. The survey provides substantial demographic data to help make sense of the wellbeing data. The use of public data sources enhances wellbeing data by providing local context and engaging local stakeholders through the public data collection process creates opportunity to receive feedback on the data collection tools and indicators from a local knowledge perspective. Again, we suggest that specific data on the material affordances of the specific environments in question would also be important to collect, from a SPT perspective.

We recognize that authentic community engagement is necessary to assess CW. As the community development, participatory research, and planning literatures have demonstrated, ‘engagement’ is often a top-down, bureaucratic process that can marginalize and exclude, instead maintaining the interests of those who are in power (Taylor Citation2007, Ospina et al. Citation2021, Poland et al. Citation2021). Power dynamics in CW assessment are inherent as formal institutions hold the power to determine who can participate, for instance in defining, identifying dimensions and indicators, measuring, and acting upon CW (Taylor Citation2007). If CW assessment is to be integrated with local governance and community development initiatives, power must be shared to transform traditional engagement into co-creation and co-production (Taylor Citation2007, Poland et al. Citation2021). This includes allocating time and resources to build long-term, collaborative structures and spaces, as well as ensuring the diversity of community members beyond the ‘usual suspects’ (Taylor Citation2007, p. 307, Ospina et al. Citation2021). Current methods to understanding CW through community participation are increasingly facilitated by digital media (Gatti and Procentese Citation2020, Citation2021) – including Photovoice.

Photovoice: a novel addition to mixed methods

Building on current participatory approaches identified in this section, we propose the data collection tool ‘Photovoice’ to understand how residents interact with and make sense of the built environment in their daily lives. Wang and Burris developed Photovoice (PV) in Wang and Burris (Citation1997) as a form of community based participatory research. Photovoice involves participants taking photographs in response to prompts to illustrate how they experience community issues. These photos are meant to represent the participant’s daily lives and give insight into how spaces and objects are meaningful to them in relation to the research topic. Participants are asked to provide a title and brief description for each image. Individual interviews and focus groups are often held following completion of the image taking to discuss the significance and meaning of the images as a group, practicing a form of community sense-making. Photovoice is performed by residents during the image-taking portion of the exercise, and engages both residents and researchers during sense-making activities.

PV analysis happens in three stages: researchers (and at other times participants) choosing the images that best represent the community’s needs/assets and material circumstances, contextualizing the images via photo-review sessions and focus groups, and identifying emergent themes (Wang et al. Citation2004). The PV method is useful in taking a social practice approach, because it reveals much about the built environment context of human activity, and also because participants can show, in addition to tell, their activities and associated meanings from these photos. An understanding of community-held wellbeing as it emerges in context (through photos, captions, and iterative group discussion) can be constructed, in a way not accessible through surveys with their pre-determined questions and scope. In particular, ‘new normals’ and emerging practices within a building community may be identified through Photovoice activities, for example during group discussion sessions when participants are agreeing with or contesting ‘what is normally done’ in or around the building. Indeed, participant interaction in group discussion may itself also be of interest for how group norms are established and/or asserted (see Lehoux et al. Citation2006). For these reasons, there has been an uptake of Photovoice as research tool. However, we imagine that, where time and resources allow, it would be valuable as a practical tool, to be integrated into processes for building management, insofar as it provides information about how residents interact with their buildings.

Implications for the development of a novel, evidence-based tool

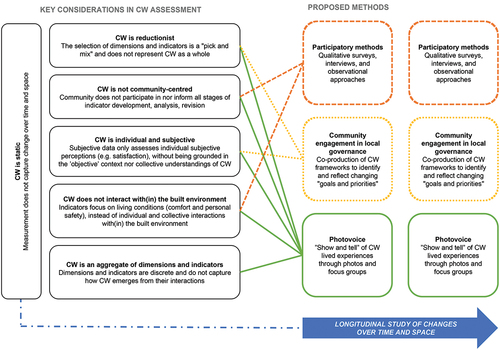

This paper identifies six considerations for current and future methods to conceptualize and measure CW. By applying an SPT lens to CW, shifting the locus of agency from the individual to the collective, methods must consider how to prevent the reductionist, ‘pick and mix’ approach to choosing CW dimensions and indicators; promote community participation at all stages of CW assessment, development, and implementation; collect subjective and objective data at the individual and collective scales; recognize how CW emerges through interactions with and within the building, beyond the aggregate of multiple dimensions, scales, and levels; and finally, capture changes to CW over time. Without these considerations, conceptual and methodological frameworks fail to represent the lived experience of CW in local, material contexts, including the emergence of CW through individual and collective interactions with the built environment.

demonstrates how each consideration for CW can be addressed through participatory methods, community engagement, and Photovoice. These methods were highlighted and suggested for working towards an assessment of CW that captures CW as a dynamic process that emerges from people ‘living collectively’. Participatory methods such as interviews, surveys, and observational sheets can include residents in the development, sense-making, and validation of CW measures and interventions. The engagement of the local community also invites and requires the integration of CW assessments into local governance structures and community development initiatives. Increased efforts to engage the local community can reframe the overreliance on assessments of individual wellbeing to centre collective goals and priorities. Photovoice, a novel data collection tool, can reveal social practices through residents representing how they experience the built environment, such as in shared spaces, which brings together subjective and objective data at both the individual and collective levels that may otherwise be missed in surveys and interviews. Together, these three methods can be repeated over time to capture how CW evolves.

There are a variety of approaches that can be integrated into practice to improve the assessment of CW in the built environment. Using participatory, interactive approaches can help us to characterize emergent CW, periodically over time and in-place. Of the three methods proposed in this paper, feasibility is an additional consideration that may place limitations on participation, whether financially or timewise. How participatory tools, community engagement, and PhotoVoice are selected and combined should ultimately be contextualized to the local community, emerging in the same way as CW. Conceptualizing and measuring CW according to the considerations and methods proposed in this paper is therefore an opportunity to apply SPT to understand wellbeing in the built environment, as articulated by Morgan et al . (Citation2022).

Conclusions

In conclusion, methods for measuring CW that take a relational, practice-based, as opposed to a standardized, individual-level, and aggregate, approach may provide a stronger basis for understanding CW by capturing the interaction between the multiple scales (individual, collective), dimensions (social, economic, environmental, cultural, political, health), and levels (building, region, neighbourhood) that inform CW in the built environment. At the building level, current frameworks fail to recognize how CW emerges from skills, meanings, and materials, which results in (mis)understandings of CW centering the individual and overlooking the ways in which collectivities are greater than the sum of their parts. Additionally, evaluating CW as an aggregate of individual wellbeing fails to capture the resident experience as it emerges from the local community context. Employing a SPT lens bridges these gaps by decentering the individual agent. This allows for CW research to acknowledge three things: (1) the agency of the material world, such that buildings and neighbourhoods can be configured to better meet community needs (2) the existence of collective properties within their community and culture (3) the procedural nature of co-producing wellbeing, where there can be emergent properties and strength in numbers.

Notes on contributors

Wellbeing in the Built Environment is a multidisciplinary research team led by Drs. John Robinson, Marianne Touchie, Alstan Jakubiec, and Blake Poland at the University of Toronto. Our two interrelated SSHRC projects, ‘Practicing Wellbeing in the Built Environment’ led by Dr. Robinson and ‘Creating a Residential Baseline for Community Wellbeing with Pilot Social and Student Housing Evaluations’ led by Dr. Touchie, share methods to assess how residential, commercial, and hybrid environments impact overall wellbeing. The overarching goal is to understand how to develop net positive environmental and human performance outcomes in the built environment, including the transition from passive occupants to active inhabitants to contribute to improved wellbeing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Some scholars (Braidotti Citation2017, Citation2018, Jeong et al. Citation2018, Walsh et al. Citation2020) have argued strongly that we also need to take account of non-human agency. That takes us beyond the scope of this paper, but for an example in the buildings field, see Gram-Hanssen (Citation2019).

References

- Amaratunga, D., et al. 2002. Quantitative and qualitative research in the built environment: application of “mixed” research approach. Work study.

- Atkinson, S., et al. 2017. What is community wellbeing? Conceptual review. What Works Wellbeing. https://whatworkswellbeing.org/resources/what-is-community-wellbeing-conceptual-review/.

- Bourdieu, P., 1990. The logic of practice. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Braidotti, R., 2017. Critical posthuman knowledges. The South Atlantic quarterly, 116 (1), 83–96. doi:10.1215/00382876-3749337.

- Braidotti, R., 2018. A theoretical framework for the critical posthumanities. Theory, culture & society, 0263276418771486. doi:10.1177/0263276418771486

- Buot, M.M., et al., 2017. Developing community wellbeing index (CWBi) in disaster-prone area of the Philippines. Journal of nature studies, 16 (1), 63–75.

- Buot, M.M. and Dulce, M.Z.C., 2019. An index to determine community wellbeing along coastal community in Leyte, Philippines. Environment Asia, 12 (1), 56–67.

- Campbell, D.E. and Campbell, T.A., 1988. A new look at informal communication—the role of the physical environment. Environment and behavior, 20 (2), 211–226. doi:10.1177/0013916588202005

- Christakopoulou, S., Dawson, J., and Gari, A., 2001. The community well-being questionnaire: theoretical context and initial assessment of its reliability and validity. Social indicators research, 56 (3), 321–351. doi:10.1023/A:1012478207457

- Cloutier, S., Ehlenz, M.M., and Afinowich, R., 2019. Cultivating community wellbeing: guiding principles for research and practice. International Journal of community well-being, 2 (3–4), 277–299. doi:10.1007/s42413-019-00033-x

- Coburn, D., et al., 2003. Population health in Canada: a brief critique. American journal of public health, 93 (3), 392–396. doi:10.2105/AJPH.93.3.392

- Coleman, S., 2016. Normalizing sustainability in a regenerative building: the social practice of being at CIRS. doi:10.14288/1.0319909

- Coleman, S., et al., 2018. Rethinking performance gaps: a regenerative sustainability approach to built environment performance assessment. Sustainability, 10 (12), 4829. doi:10.3390/su10124829

- Coleman, S. and Robinson, J., 2018. Introducing the qualitative performance gap: stories about a sustainable building. Building research & information, 46 (5), 485–500. doi:10.1080/09613218.2017.1366138

- Cox, D., et al., 2010. Developing and using local community wellbeing indicators: Learning from the experience of community indicators Victoria. The Australian journal of social issues, 45 (1), 71–88. doi:10.1002/j.1839-4655.2010.tb00164.x

- Davern, M.T., et al., 2017. Best practice principles for community indicator systems and a case study analysis: how community indicators Victoria is creating impact and bridging policy, practice and research. Social indicators research, 131 (2), 567–586. doi:10.1007/s11205-016-1259-8

- Francis, J., et al., 2012. Creating sense of community: the role of public space. Journal of environmental psychology, 32 (4), 401–409. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2012.07.002

- Fuller, M.G., 2017. Great spatial expectations: on three objects, two communities and one house. Current sociology, 65 (4), 603–622. doi:10.1177/0011392117694071

- Gatti, F. and Procentese, F., 2020. Open neighborhoods, sense of community, and Instagram use: disentangling modern local community experience through a multilevel path analysis with a multiple informant approach. TPM - testing, psychometrics, methodology in applied psychology, 27 (3), 313–329. doi:10.4473/TPM27.3.2

- Gatti, F. and Procentese, F., 2021. Experiencing urban spaces and social meanings through social media:unravelling the relationships between Instagram city-related use, sense of place, and sense of community. Journal of environmental psychology, 78, 101691. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101691

- Giddens, A., 1984. The constitution of society: outline of the theory of structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Gram-Hanssen, K., 2019. Automation, smart homes and symmetrical anthropology: non-humans as performers of practices? In: Y. Strengers, ed. Social practices and dynamic non-humans. Palgrave Macmillan, 235–253. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-92189-1_12

- Hanc, M., McAndrew, C., and Ucci, M., 2019. Conceptual approaches to wellbeing in buildings: a scoping review. Building research & information, 47 (6), 767–783. doi:10.1080/09613218.2018.1513695

- Ho, D.C.W., et al., 2008. A survey of the health and safety conditions of apartment buildings in Hong Kong. Building and environment, 43 (5), 764–775. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2007.01.035

- Huang, S.C.L., 2006. A study of outdoor interactional spaces in high-rise housing. Landscape and urban planning, 78 (3), 193–204. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2005.07.008

- Jeong, S.S.K., et al., 2018. Composing new understandings of sustainability in the Anthropocene. Cultural studies of science education, 13 (1), 299–315. doi:10.1007/s11422-017-9829-x

- Lee, Y.-J., 2008. Subjective quality of life measurement in Taipei. Building and environment, 43 (7), 1205–1215. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2006.11.023

- Lee, J., Je, H., and Byun, J., 2011. Well-being index of super tall residential buildings in Korea. Building and environment, 46 (5), 1184–1194. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2010.12.010

- Lee, S.J. and Kim, Y., 2015. Searching for the meaning of community well-being. In: S.J. Lee, et al, ed. Community well-being and community development. springerbriefs in well-being and quality of life research. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-12421-6_2

- Lee, S.J. and Kim, Y., 2016. Structure of well-being: an exploratory study of the distinction between individual well-being and community well-being and the importance of intersubjective community well-being. In: Y. Kee, S.J. Lee, R. Phillips, eds. Social factors and community wellbeing. Switzerland: Springer, pp. 13–37.

- Lehoux, P., Poland, B., and Daudelin, G., 2006. Focus group research and “the patient’s view. Social science & medicine, 63 (8), 2091–2104. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.05.016

- Lowe, M., et al., 2013. Liveable, healthy, sustainable: what are the key indicators for Melbourne neighbourhoods? Place, health and liveability research program. Melbourne, AU: University of Melbourne. https://socialequity.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/1979574/Liveability-Indicators-report.pdf.

- Markovich, J., Angelo, M.S.D., and Dinh, T., 2018. Community wellbeing: a framework for the design professions. Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada.

- Miles, R.L., et al., 2008. Measuring community wellbeing: a Central Queensland case study. The Australasian journal of regional studies, 14 (1), 73.

- Morgan, G., et al., 2022. Forthcoming.

- Ospina, S.M., Burns, D., and Howard, J., 2021. Introduction to the handbook: navigating the complex and dynamic landscape of participatory research and inquiry. In: D. Burns, J. Howard, & S. Ospina. The SAGE handbook of participatory research and inquiry. SAGE Publications Ltd, 3–16. doi:10.4135/9781529769432.n1