ABSTRACT

Governments are increasingly recognising the importance of paying attention to the effect of the environment on the health of city inhabitants. In order to achieve a healthy living environment, it’s necessary to specify what a healthy living environment is and to integrate health considerations into decision-making processes. Unfortunately, this still happens too little. This explorative study investigated, with focus groups, whether the views of inhabitants on healthy living environments can play a role in increasing attention to health in spatial planning and decision-making processes. We investigated what inhabitants thought of their environment in relation to their health and which elements were important in creating a healthy living environment. Results showed that inhabitants desire a healthy living environment. In addition to elements in the natural, built, and community environment, inhabitants named three essential conditions that should be taken into account, namely surveillance and law-enforcement, the performance of daily tasks by public institutions, and the involvement of inhabitants in developments in their living environment. These conditions and the perceptions of inhabitants can be valuable information for municipalities. Increased involvement of inhabitants in spatial planning processes would make it possible to incorporate more attention to health in these processes than is currently the case.

Introduction

It was only in the 1970s that lifestyle and living environment were recognised as being equally important for health as biological factors and health-care facilities (Lalonde Citation1974). Since then, considerable research has been done on the relationship between environment and health. Research confirms that various aspects of the living environment have a significant influence on health and well-being (Bird et al. Citation2018). For example, availability of a network of different types of footpaths and bike paths influences physical activity (Salvo et al. Citation2018, Kärmeniemi et al. Citation2018); the presence of different types of green spaces promotes health (van den Berg et al. Citation2015, Krefis et al. Citation2018, Jarvis et al. Citation2020); and noise nuisance from traffic has a negative association with mental health (Putrik et al. Citation2015). In addition to studies that confirm the relationship between environment and health, other studies teach us more about how health relates to factors such as size, use and experience of green spaces, and quality of urban environment in relation to health (Gozalo et al. Citation2019, Grazuleviciene et al. Citation2020, Kruize et al. Citation2020). Other studies that relate to health have focussed on the role of urban design or needs of specific groups like children (Pereira et al. Citation2019) or older people (Mulliner et al. Citation2020, Brüchert et al. Citation2021). Moreover, research has indicated the importance of the environment for the social aspects of health, such as social cohesion, social interaction and opportunities for participation (Perez et al. Citation2020).

To create a healthy living environment, it is vital to devote attention to elements that contribute to health in spatial planning processes by dealing with the design of the environment. In the Netherlands, municipalities bear a major responsibility for the design of the living environment. The responsibility for a healthy living environment is to become even more explicit in the near future with the institution of a new law, the Environment Act (Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal Citation2014, Environment and Planning Act of the Netherlands Citation2021), which places more emphasis on health than in the past. However, it is not easy to achieve this goal and ensure that sufficient attention is paid to health in spatial planning. To get to this point, municipalities must first face substantive (Bird et al. Citation2018), organisational (Verbeek and Boelens Citation2016) and procedural challenges (Lowe Citation2018).

The first requirement for reaching this goal is to answer the question, ‘What is a healthy living environment?’. Traditionally, the spatial planning process has focussed on health through well-known environmental themes like air quality, soil pollution and noise levels (Kent and Thompson Citation2014). Today, especially in the Netherlands, more and more politicians and policymakers are embracing a broader concept of health (Institute for Positive Health Citation2018). This means that in addition to the pure physical health of an individual (ill or not), politicians and policymakers also find it important to consider other factors that determine the state of someone’s health, for example social contacts, or opportunities for participation in activities and for living a healthy lifestyle. While the personal experience and perceptions of inhabitants are meaningful, conditions within society and the immediate living environment are equally so. Poverty, housing shortage and social tensions can directly or indirectly affect inhabitants’ health, for example through increased stress (Cutrona et al. Citation2006).

Secondly, this subject requires that municipal departments of social affairs and city planning work together in spatial planning processes in order to agree on their priorities and ideas as what a particular area needs. However, various studies have shown that while civil servants do see the importance and necessity of cooperation, they still perceive cooperation as difficult because of differences in scope, process, culture, and interests (Carmichael et al. Citation2012, Hendriks et al. Citation2014, Larsen et al. Citation2014). Similarly, the process can also be hampered by language differences between professionals who work with social matters and those who work in city planning (Carmichael et al. Citation2012, Lge-Elegbede et al. Citation2021). In a previous study (Mourits et al. Citation2021), we investigated whether the professionals (civil servants, policymakers, planners, process and project managers, and executives) from these two worlds held a shared view about healthy living environments and how similar (or different) their priorities in spatial planning processes were. This study gave more clarity among professionals about what is meant by a healthy living environment. However, it is not only about what professionals think, but also what inhabitants experience and consider important.

Finally, it is a challenge for municipalities to achieve a proper balancing of interests that produces an integral and well-considered decision. How does one do this and who should be involved? Municipalities have ambitions in various policy areas and these ambitions come together in one specific area of development. Due to limited space and resources, a choice has to be made. Health is still insufficiently included in this weighing of interests, partly because of the two challenges mentioned above. Perhaps the attention for health in this regard can be increased if the views of the inhabitants are taken as the starting point, a stance that political parties in the Netherlands are now increasingly propagating.

While it is evident that encouraging inhabitants’ participation in spatial planning is needed to promote democracy and political legitimacy, previous studies have also identified many reasons to encourage it for the sake of health. First of all, it is beneficial to incorporate the desires and perceived needs of inhabitants into environmental plans, because when inhabitants are satisfied with their living environment and perceive its quality as high, they tend to have better self-reported health (Wen et al. Citation2006, Shagdarsuren et al. Citation2017, Salvo et al. Citation2018, Gozalo et al. Citation2019, Kruize et al. Citation2020). Secondly, involvement of inhabitants results in the use of more local knowledge, creates support for environmental plans and improves the quality of the final product (Rydin and Pennington Citation2000, Reed Citation2008, Drazkiewicz et al. Citation2015, Stankov et al. Citation2017). Thirdly, research shows that involvement of inhabitants may serve as a method of health promotion, because it empowers community members (Laverack Citation2006, Broeder et al. Citation2017) and can improve health (Kanarek et al. Citation2006).

The aim of this study is to explore the perceptions of city inhabitants about health in their living environment, and to examine how this knowledge can lead to increased attention to health in spatial planning processes. Therefore, the research questions we ask are: 1) according to inhabitants of the city of Nijmegen, which elements in the urban living environment influence their health; and 2) what are the most important elements for improvement? With this information, we can understand their perspectives and thereby assess the added value of involving them in spatial planning processes.

Materials and methods

For this exploratory study, we found it important that the research method was compatible with the way inhabitants are normally involved in spatial planning processes. Often, inhabitants are approached as a group by means of inhabitants’ meetings. We were interested in the collectively formed opinion of inhabitants about the situation in their own living environment. Therefore, a focus group method was preferred over conducting individual interviews. A focus group discussion can provide a good overview of participants’ subjective experiences (Barbour Citation2008). Moreover, the group interaction between participants allows them to hear, discuss and compare each other’s experiences. This situation provides useful insights into group reasoning and collective point of view (Morgan Citation1997), as well as reflecting the everyday reality of inhabitants’ meetings.

Furthermore, the focus of the study was on the various substantive topics that inhabitants would raise, rather than a systematic analysis of who contributed which topic, or whether there were differences between groups of inhabitants or neighbourhoods. This is in line with everyday practice for spatial planning processes, in which municipalities need to make a trade-off between different contributions based on content and different interests, while devoting less attention to which group of inhabitants made which contribution.

The medical ethics committee for the Arnhem-Nijmegen area approved this study, which was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (October 2013, 64th WMA General Assembly) and in accordance with the Dutch Personal Data Protection Act.

Description of study area

As a study area we chose districts in the city of Nijmegen, the Netherlands. A description of the characteristics of the city and its districts is added as supplementary material. The choice for Nijmegen was due to the fact that a larger exploratory study is being conducted into how to include health in spatial planning projects, using the municipality of Nijmegen as the research object. As a result, we can compare the results of the current study with results from a previous study among professionals.

Recruitment

To ensure that participants were familiar with each other’s living environment, we recruited participants per district and the focus group was held in their own district. The participants were recruited actively during a meeting at a community centre and with snowball sampling, or passively by advertisements in local magazines, flyers distributed in community centres and online advertisements on community webpages. Participants had to be above 18 and living in one of the districts, but there were no other inclusion or exclusion criteria. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before the start of the focus group.

Setting and procedure

The focus groups took place in conference rooms at a local community centre and lasted approximately 90 minutes. Prior to the focus group discussion, all participants completed a short questionnaire including demographic information. At the end of the meeting, all participants received a €10 gift card as compensation for their time.

The focus group interviews were guided by a moderator and supported by an observer (authors K.M. and I.K). The two researchers alternated in the roles of moderator and observer for each focus group.

After all participants had introduced themselves, we started with an introductory question about what it was like to live in their district. Participants had been asked to bring a photo of a situation in their environment that had an influence (positive or negative) on their health. These photos were an easy tool for starting the proceedings: everyone could share their opinion at the beginning and everyone was engaged in the discussion.

Subsequently, the moderator used a semi-structured guide to lead the focus group discussion. This guide was developed and reviewed by the research team (authors K.M., I.K. and G.M) for content and structure. The key questions were 1) ‘In what way does the living environment of [name of district] influence health?’; 2) ‘You have discussed several ideas, but what is the most important one for health?’; and 3) ‘What would [name of district] be like if it was a healthy district?’ This last question was asked to help the authors identify the most important elements for improvement.

Data analysis

Each group was audio recorded, transcribed verbatim and reviewed by authors K.M and I.K. for accuracy. Atlas.ti 8.3.20 qualitative software was used to facilitate data management and analysis.

Initially, transcripts were coded with open coding, meaning that relevant sections were identified (Gibbs Citation2007). Sections were regarded as relevant if they related to the research aims or questions. The authors made an initial code tree together and independently coded the data from all seven focus groups. They met to compare their work on the first three focus groups and reached consensus on the final code tree and coding of these groups. As we noticed that the coding was similar and no new codes had been introduced, groups four to seven were again coded independently by authors K.M. and I.K. Author I.K. compared those codes, discussed uncertainties with author K.M. and decided on the final coding of these groups.

During the open coding, the following types of data were coded separately: data related to the relationship between health and environment according to inhabitants, what inhabitants found important and what inhabitants found to be significant improvements. After the open coding the data was organised, which means some codes were integrated. An overview of the final codes is contained in the supplementary material. An iterative process and the use of axial coding and co-occurring made it possible to answer the research questions. All quotes were filtered that had been encoded because they contained an effect relationship between health and living environment. The quotes were re-read to see what relationship they referred to. All quotes that indicated an explicit effect of environment on health were enumerated and categorised per category. Furthermore, the quotes in which participants explicitly indicated a concept as important were filtered and re-read. The important topics were listed. Finally, the remaining codes were examined to determine whether the results added anything to this study.

Data presentation

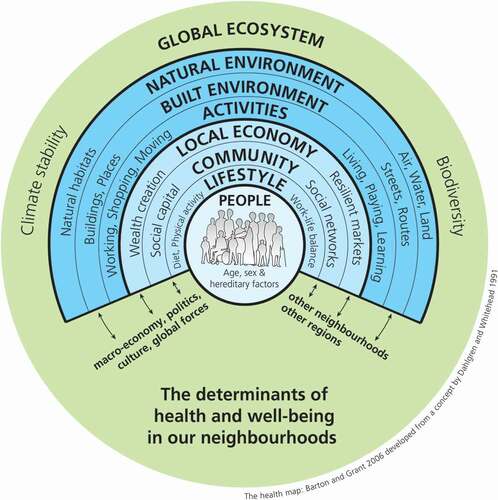

The experiences and perceptions of the inhabitants about the living environment and health are in the focus of this explorative study. However, in order to properly display the results, we used the ‘Health map for the local human habitat’ (Dahlgren and Whitehead Citation1991a, Barton and Grant Citation2006) of Barton and Grant as a framework () to structure the results. This framework is based on the rainbow model of Dahlgren and Whitehead (Citation1991a, Citation1991b) which schematically indicates which determinants, beside the individual, have influence on the health of inhabitants. Barton and Grant expanded the model of Dahlgren and Whitehead with some elements that are relevant for this study, such as other neighbourhoods, global ecosystems and politics. We also compared the results with the results of our earlier study (Mourits et al. Citation2021) which examined how professionals in Nijmegen view a healthy living environment. In the discussion section, we will reflect on the differences between professionals and inhabitants.

The quotations used in this article were translated by a Dutch-English translator from Radboud University Nijmegen in the Netherlands.

Results

Participants

In May 2019, we conducted seven focus group interviews with a total of 35 inhabitants in seven districts of the city of Nijmegen, the Netherlands. Groups ranged in size from three to eight participants and the participants were aged between 30 and 72. The 35 participants had higher levels of income and education than the population of Nijmegen as a whole, and the proportion of women was higher than in the general population. Therefore, this group was not entirely representative of the city’s population ().

Table 1. Demographics participants.

Inhabitants’ general opinions of their living environment and health

The vast majority of the participants explicitly stated that their living environment was a pleasant place to live. At the same time, almost half of the participants also perceived an aspect of the living environment as disturbing or negative. As a participant said:‘Basically, I love living there, otherwise I wouldn’t have stayed there so long. I’m very happy, but these (traffic and air pollution) are things that worry me’.

Participants stated that they often felt that the living environment had a direct effect on their general feeling of health, positive and negative in equal measure. provides an overview of the most often mentioned positive and negative aspects of health according to the participants per district. The overview shows that there were similarities between neighbourhoods, but also differences, especially concerning the negative effects on health.

Table 2. Positive and negative elements of the living environment and their effect on health per focus group.

Using the classification of the ‘Health map for the local human habitat’ (Dahlgren and Whitehead Citation1991a, Barton and Grant Citation2006), we will present and explain the results in more detail below, including what, according to the participants, could be done better or differently to make the environment healthier. However, not every participant had an idea for an improvement in the living environment and some felt that no improvements were necessary. As one participant said, ‘It is a privilege to live in this area’.

Natural environment

The existing natural environment has positive effects on health, namely the presence of tranquillity and the possibilities for exercise in a green and well-appointed public space. In one of the focus groups, a participant described the importance of the natural environment as follows: “I just love the fact that everything’s so green, and so I really like to walk a lot through the neighbourhood. I see all the trees budding and I see birds, and that makes me feel really good. And when I’m at home and I’m not feeling so well, I just go outside and then I think, ‘Oh, it’s so beautiful here’, and then everything feels better, you know?” However, the natural environment had also a negative effect on the participants’ health by causing worry and stress regarding air quality, partly because of the presence of traffic.

Even though the participants were already positive and satisfied with the greenery, they found that there was always room for improvement and more greenery. One of the participants was also actively involved in greening the environment by making a local garden with neighbours: ‘A local garden. Making a bare lawn that’s only good for walking the dog into a really beautiful garden. We’re doing that now’.

Built environment

The presence of car traffic caused worry and stress, partly due to the influence this had on air quality. A participant mentioned, ‘I also sometimes worry about the traffic flow (the S100 highway)’ and ‘It’s getting busier all the time’. Further, participants experienced a negative effect on their health due to noise pollution, which meant that participants slept less. An example one of the participants mentioned was, ’When I wake up at night and have to close the window, I feel less rested in the morning’.

The most frequently mentioned improvements to the environment were being car-free, less traffic and more traffic safety. As one of the participants put it: ‘Fewer traffic diversions, that’s something I hear from a lot of people in the neighbourhood,’ or as a participant in another focus group wished, “I’d actually like to be much more radical than just ‘low traffic’. It would be fantastic if Nijmegen said, ‘We’re going to develop a car-free zone that is for people who have no cars, and is only accessible to people without cars’. That would be a good initiative”.

In addition to traffic-oriented adjustments, participants also saw building mixed neighbourhoods with people from different backgrounds, suitable and affordable housing, and affordable public transport as ways to improve the built environment and inhabitants’ health. One participant mentioned building less densely as an important point: ’Build houses less close together. I think that’s the main reason for the problem, so few houses are being built, and those new houses are much too close together’.

Activities

As for activities in the area, participants declared that it was important to have space for children to play, opportunities for walking and opportunities to meet other people. The participants also believed that many improvements could be made to create more opportunities for outdoor exercise. ‘I’d like for them to make more and safer play areas for children’.

Adaptations to create a more exercise-friendly environment were often mentioned in combination with less traffic and more greenery: ‘I think we should allow fewer cars and have much more greenery, so that people will come outdoors much more. If I could design it, I’d want to make it a very low-traffic zone, so that everyone exercised much more by walking or cycling, because there are a lot of overweight people in the neighbourhood’.

In addition to improvements in the public space to promote more exercise and greenery, participants also indicated that more attention must be paid to the services in the neighbourhood. The presence of a shop or café contributes to the ability to feel healthy, as a participant mentioned: ‘One small drawback for me is about cafés and restaurants, and the social contacts that you can build up there. I miss those, and I’ve missed them for a long time’.

Local economy, community and lifestyle

All groups stated that the community and the social living environment in the neighbourhood determined whether inhabitants felt healthy and lived in comfort. Participants found it important to have contact with neighbours, to know each other a little bit and to meet each other during activities or in a local shop. ‘We’ve had a number of neighbourhood parties and they’re really nice because you chat then with people that you don’t normally talk to. And when you come across them the next time, then you do say hello or have a conversation, and I think it’s a shame that these parties have stopped’.

However, opinions differed among participants and districts as to whether these contacts were always successful, and whether they could enhance social cohesion in the neighbourhood and contribute to health. Success was partly determined by differences in people, type of houses in the street (purchased or rental) and new or long-residing inhabitants. According to participants, the social environment or community also came under pressure in several neighbourhoods. The neighbourhood was less pleasant to live in and contact with neighbours had become more difficult. The participants mentioned three factors that contributed to this. The first of these was the presence of more students in the neighbourhoods. Family homes that turn into student homes created a different atmosphere in the neighbourhood. ’I also notice that the number of rooms for rent in the neighbourhood is growing. For cheap houses that cost less than €200,000, I wish that young families could come and live there. But then they’re bought by some real estate person that divides it up into rooms and rents them to students. Now I’ve got no problem with students, it’s just that it changes the neighbourhood so that it can get out of balance. And I notice that having all these rooms for rent doesn’t help things’.

Second, the number of volunteers who were willing to organise public activities for the community was shrinking, and third, people found it increasingly difficult to converse with other inhabitants about their negative behaviour. Participants would appreciate it if inhabitants were more considerate to each other, and adjusted their behaviour accordingly: they felt that would make a big difference. As a participant stated: “Do neighbours take each other into account when driving down the street, making noise in the evening or walking the dog? It’s people who do that, and then children come and play by the water and people let their dogs run around there. Then I think, ‘Get out of here, this is a playground’.”

When discussing improvements, participants indicated that more should be done about safety and surveillance. One participant referred to the following example in a district: ‘I’m thinking of the area around the shopping centre and safety on the streets. Not just the safety, but it should all look better too. I think if nothing changes in the next couple of years, then it’ll be too late. And we need more law enforcement and surveillance of drug dealers, troublemakers’.

The individual (people)

In addition to factors such as natural and built environment, activities and community, participants also indicated more social, personal, subjective and emotional factors that were important. Factors that were mentioned were the possibility of freedom of choice, and the sense of feeling at home, being resilient and in control.

Politics and conditions for a healthy living environment

Besides factors in the living environment that influence the health of the participants, the participants also stated three major conditions that should be taken into consideration when creating and maintaining a healthy living environment in a city, namely surveillance and law enforcement, the performance of daily tasks by public institutions, and the involvement of inhabitants in developments in their living environment.

First mentioned was the specific tasks of authorities, such as the municipality and the police, regarding surveillance and law enforcement. According to the participants, the authorities’ presence in the neighbourhood, their response to signals from inhabitants and their taking action against violations of laws and regulations had a major influence on participants’ living environment and thus on their health and well-being. ‘The city does have policies to prevent making too many houses into student apartments, but they don’t enforce them. They only do it in places that are hotspots. But I hear people who live in some neighbourhoods saying, ‘Hey students, a house is going to become available’. You hear this in lots of neighbourhoods and nobody pays any attention.‘

Second, the performance of daily tasks by public institutions, such as the municipality, the police, and housing associations was important. A participant gave the example of the police: ‘A good community police officer is worth their weight in gold. If they’re the right kind of officer, they can really get people to talk about things with each other. … I never see any community officers around anymore, but it’s still a good thing’. Another observation made about the municipality was that the municipality helped inhabitants to set up their initiatives or provided modest financing, which the participants appreciated. However, participants also mentioned that the choices of decisions made by the municipality concerning certain issues often varied from one neighbourhood to the next. ‘They seem unpredictable. When you check what’s going on, it turns out that somebody just managed to call the right person who knows the next person that should be called. It shouldn’t be that way, but it always turns out that that’s how things are’.

The final point raised by inhabitants was their involvement in developments in their living environment. The participants presented varying views on involvement in spatial developments and municipal planning in the residential environment. On the one hand, there was good dialogue between the municipality and inhabitants through neighbourhood councils. Inhabitants were also given opportunities to start their own construction or maintenance projects, which means that those involved had a good deal of influence on the final result. ‘For example, we drew up the greenery plan ourselves. That means we have an official agreement with the city that we will look after the planting ourselves, form a playground committee, things like that’. On the other hand, participants were also negative because while discussion meetings were held, nothing was done about the suggestions that inhabitants made. Furthermore, participants felt that municipal administrators and project developers were often preoccupied with their own interests. The participants stated that they had little say in changing aspects of a project, although it was sometimes possible to oppose certain plans and prevent them from going ahead. A participant in one of the focus groups gave the following example: ‘And speaking of money, a project developer thought he saw an opportunity there. He had a great big plan to building high buildings with flats, it was horrible. We questioned it but he wanted to use all his money to push his plans through. Thank goodness, the city council finally managed to buy the property for another purpose’.

According to the participants, having a degree of influence and feeling of control over their own environment contributed to their health. As described by one participant, ‘What I find important, the feeling that you can do something about it, in whatever way … we do a lot together with the municipality, and the feeling that it will amount to something makes you feel better’. This was also described as ’having a grip on your direct living environment’.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore the perceptions of city inhabitants about health in their living environment, and to examine how this knowledge can lead to increased attention to health in spatial planning processes. To this end, we held focus groups in the city of Nijmegen and asked the inhabitants to name elements in their urban living environment that influenced their health as well as the most important elements for improvement.

We found that the inhabitants generally perceived their living environment as pleasant and that features of the natural and built environment such as greenery, space and facilities contributed to their perceived health. The presence of greenery in particular was highly appreciated, but inhabitants also declared that they wanted more greenery to create a healthier environment. At the same time, a large proportion of participants felt that certain aspects of the natural and built environment had some negative effect on their health, in particular noise, traffic and air quality. Other improvements were desired in many areas, such as car-free zones, less traffic, improved traffic safety, more meeting and play areas, and more services.

We have used the concept of ‘Health map for local human habitat’ (Dahlgren and Whitehead Citation1991a, Barton and Grant Citation2006) as a framework to present our results. In the process of arranging the findings from this study, we discovered that not all issues that inhabitants came up with have a clear place in such a framework. Some topics that were introduced can fit into multiple categories, like walking (activities/lifestyle), meeting people (activities/community) or safety (built environment/community). In addition, the inhabitants also added experiential, subjective and emotional values. These soft aspects are important to inhabitants in the relationship between health and their living environment, but they do not fit that well into any section of Barton and Grant’s framework. Final decisions in spatial planning development are usually dominated by hard aspects and measures, but the findings of this study show how important soft aspects are for the quality of those decisions. In future investigations of this point, an adjustment of the framework might be needed.

Professionals involved in city planning process should be aware of the existence of the elements that are important for inhabitants. The only question is whether this is sufficiently the case. In a previous study (Mourits et al. Citation2021) in the same city, professionals, many of whom worked for the municipality, indicated that quality (integration of the plan in the area, appearance and implementation) is considered most important in a spatial planning process, followed by the opportunities for exercise and whether the area was accessible, clean and quiet. These are significant factors for creating a healthy living environment, but it is striking that the participants in this study mainly came up with other topics, such as greenery, less traffic and community. However, these topics are not directly those for which professionals see the most opportunities to work on in spatial planning projects; instead, they again mention spatial quality and exercise, in addition to climate (Mourits et al. Citation2021). There seems to be a mismatch between what professionals focus on and what inhabitants would like to pay attention to. Such a mismatch can have the effect that spatial projects, even if they pay attention to exercise, accessibility and tranquillity, have less effect on the perceived health of inhabitants (Gebel et al. Citation2011). Of course, it is important in spatial planning developments that attention is paid to the objective knowledge about the relationship between environment and health. However, we call on civil servants to use multiple sources of knowledge in a planning process and not only objective standards, definitions and models. By inviting inhabitants to share their knowledge, perceptions and experiences about the environment in relation to the effect on their health, extra topics relating to health or having a major impact on their health can be incorporated into the spatial planning process.

Furthermore, even though participants indicated that health is not only about the design of the environment, our results indicated that the inhabitants attached great importance to being involved in spatial planning as a way of promoting their individual health. They wished to have a sense of control over their lives and living environment. This finding is line with previous studies which state that the involvement of inhabitants in planning projects contributes to their health in various ways (Wen et al. Citation2006, Broeder et al. Citation2017, Kruize et al. Citation2020). However, there is still much room for improvement when it comes to the involvement of inhabitants in the process. This situation is reflected in our results, and also emerges from the study by Nadin et al. (Citation2021) about trends across Europe concerning integrated, adaptive and participatory spatial planning. Participants perceived their influence as limited, even though they were allowed to take part in discussion evenings. Perhaps this perception is related to how the municipality deals with the input of inhabitants, as Eriksson et al. indicates. Their study (Eriksson et al. Citation2021) showed the extent of the power exercised by municipal planning actors and how these actors affect the fate of the input provided by citizens. The upcoming New Environmental Law in the Netherlands may provide opportunities to increase the involvement and influence of inhabitants, but both municipalities and inhabitants must act on this opportunity, and the extent to which this will actually happen remains an open question (Helleman et al. Citation2021).

However, the participants also emphasised that inhabitants can make a personal contribution to a healthier environment. A good example in the city of Nijmegen is ‘Operation Steenbreek’, in which inhabitants are helped to turn their paved gardens into green ones. By greening their own garden, they contribute to a healthier living environment for the whole street (Operatie Steenbreek Citation2018). This approach is also in line with the capability approach (Chiappero-Martinetti et al. Citation2020) in which people are given the freedom to shape their own lives and environment. This development revolves around putting inhabitants and the community at the centre of the action and offering them the space and support to contribute to societal health. However, with this development it is very important that municipalities remain aware of their role and responsibilities to different groups of inhabitants while ensuring that the general interest is also served (Stevens and Dovey Citation2019). The goal here is to achieve good interaction between inhabitants, organisations and governments to work together on a healthy living environment. In addition, these parties must find the right balance and form of participation, cooperation and use of knowledge and experience. It will be interesting to follow these developments in participation, collaboration and co-production in the coming years.

For this study we chose to stay as close as possible to the practical situation of involving inhabitants in a spatial planning process. This resulted in a choice for the focus group method with an open call for participation per district. The participants in the focus groups were therefore inhabitants who were interested in the subject and had the time to participate. This phenomenon can also be seen in the daily practice of citizen participation. People who are interested and who have time to talk about a subject with the municipality come to meetings. This means that this study has to deal with the same problem as in day-to-day citizen participation, namely that certain inhabitants are not reached and are not heard. It is therefore important that forms of participation are found that do reach these groups of inhabitants. This same observation applies to the method of this type of research. It might be interesting in a future study to opt for a more citizen science approach (Den Broeder et al. Citation2016) based on research in combination with more participatory action-oriented research in a daily spatial planning project (Strydom and Puren Citation2014).

Another inherent limitation of our selection procedure is that it does not allow us to say anything about needs for a healthy living environment within specific groups. It is important that spatial planning should devote attention to differences between groups, which have been identified in previous related studies. For example, the elderly need to be able to continue living independently (Garin et al. Citation2014), and there are several sex-relevant differences in the ways individuals perceive their physical environments (Bengoechea et al. Citation2005). Due to the design of the study, it was also not possible to further explore differences between groups/neighbourhoods or specific topics that came up in the discussions. The densification of the city is a source of tension for inhabitants, and in inner-city development, urban planners must account for various policy objectives that are at odds with each other. Space for greenery and water collection might compete with building houses, accessibility or quality of life. These issues are encountered daily by policy advisers working towards a healthy living environment. Therefore, topics such as the tension in the use of space during densification or between private and public are certainly interesting topics for future research. Another limitation of this study originating from the choice of method is the lack of depth and sharper description of the substantive elements for a healthy living environment, which would also be an interesting subject for further investigation. The more precisely inhabitants indicate what is needed, the better it can be incorporated into the planning. This need for concreteness also emerges in conversations with professionals in a study which we are in the process of completing.

Despite these limitations, the results of this study are relevant for municipalities and professionals involved in spatial planning development. No two municipal environments are the same, and their inhabitants have differing ideas about how to make their personal environment healthier, but it clearly emerges from this study that inhabitants want to be heard and involved in spatial planning projects. An approach that encourages more involvement and participation from inhabitants is certainly something that other cities and municipalities should start working on. Inhabitants have knowledge, perceptions and experiences that can be effectively drawn on in realising an environment that contributes to their health. Their knowledge and experience are an essential supplement to what professionals know and consider important. Since municipalities claim that they are there for the inhabitants, it is logical that they should clearly incorporate inhabitants’ health priorities into their decision-making process. We therefore offer the following recommendations to planners and policymakers. First of all, they should actively strive for the participation of inhabitants in spatial planning processes, at the start, at later moments in the process, and involving inhabitants in the choices to be made. Second, they should make use of different forms of participation, not only consultation meetings, but group discussions and interviews as well. They also need to put extra effort into reaching specific groups. Third, they must be aware of and use different sources of knowledge, both objective and subjective. Each source has its own value in the planning process and can contribute to a healthy living environment. Furthermore, these results are interesting for professionals who work with health promotion in community districts. Motivating and helping inhabitants to be more involved in the design of the neighbourhood is another type of intervention for achieving health goals.

Conclusion

Inhabitants were able to clearly identify what aspects of their living environment influenced their health and indicated three conditions, including involvement in spatial planning processes, that must be met in order to create and maintain a healthy living environment. This knowledge is valuable information for municipalities and professionals involved in spatial planning development. Promoting and increasing the involvement of inhabitants in the planning process will help to create spatial planning developments that promote health more than is currently the case. Future research should explore how involving inhabitants can help municipalities to convert their methods of spatial planning into a health-promoting spatial planning process.

Author contributions

This article was conceptualised by K.M, I.K, G.M. The investigation and the collection of data were undertaken by K.M and I.K. The writing of the original draft was prepared by K.M and reviewed by I.K, G.M and K.V. This article was supervised by G.M. and K.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethical issues

The medical ethics committee for the Arnhem-Nijmegen area approved this study (no.2018-4251). This study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (October 2013, 64th WMA General Assembly) and in accordance with the Dutch Personal Data Protection Act. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (216 KB)Disclosure statement

Researcher K. Mourits also works as a policy adviser for the municipality of Nijmegen.

Data availability statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23748834.2022.2103390

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kristine Mourits

Kristine Mourits is working at Academic Collaboration Centre AMPHI on her PhD research about how health can be included in spatial planning developments. Kristine is also involved as a researcher in the Space2move consortium in the context of the Zonmw programme ‘Make Space for Health’. In addition to her work at AMPHI, Kristine works as a senior policy adviser/social-physical connector for the municipality of Nijmegen.

Ilse Knoops

Ilse Knoops was a student during this study and did a master’s degree in Health Education and Promotion at Maastricht University. This study was part of her graduation internship and thesis. She now works as a health promoter at the GGD Brabant-Zuidoost.

Koos van der Velden

Koos van der Velden is emeritus professor and former head of the Department of Public Health at the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center. His main research topics are infectious diseases control and health systems development.

Gerard Molleman

Gerard Molleman is emeritus professor by special appointment of person-oriented prevention at Radboudumc and former manager of Healthy Living at GGD Gelderland-Zuid. The aim of the chair was to strengthen a sustainable collaboration between public health and primary and secondary care, so that patients can be challenged to participate in health-promoting activities in the neighbourhood.

References

- Barbour, R., 2008. Doing focus groups. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Barton, H., and Grant, M., 2006. A health map for the local human habitat. The journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health, 126 (6), 252-253, doi:10.1177/1466424006070466.

- Bengoechea, E.G., Spence, J.C., and McGannon, K.R., 2005. Gender differences in perceived environmental correlates of physical activity. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity, 2 (1), 1–9. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-2-12.

- Bird, E.L., et al., 2018. Built and natural environment planning principles for promoting health: an umbrella review. BMC public health, 18 (1), 930. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5870-2.

- Broeder, D.L., et al., 2017. Community participation in health impact assessment. A scoping review of the literature. Environmental impact assessment review, 66, 33–42. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2017.06.004

- Brüchert, T., Baumgart, S., and Bolte, G., 2021. Social determinants of older adults’ urban design preference: a cross-sectional study. Cities & health, 1–15. doi:10.1080/23748834.2020.1870845.

- Carmichael, L., et al., 2012. Integration of health into urban spatial planning through impact assessment: Identifying governance and policy barriers and facilitators. Environmental impact assessment review, 32 (1), 187–194. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2011.08.003.

- Chiappero-Martinetti, E., Osmani, S., and Qizilbash, M., 2020. The Cambridge handbook of the capability approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Cutrona, C.E., Wallace, G., and Wesner, K.A., 2006. Neighborhood characteristics and depression: an examination of stress processes. Current directions in psychological science, 15 (4), 188–192. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00433.x.

- Dahlgren, G. and Whitehead, M., 1991a. “The main determinants of health” model, version accessible in: Dahlgren G, and Whitehead M. (2007) European strategies for tackling social inequities in health: levelling up part 2. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

- Dalhgren, G., and Whitehead, M., 1991b. Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Background document to WHO – strategy paper for Europe. Arbetsrapport 2007:14 Institute for Futures Studies. https://ideas.repec.org/p/hhs/ifswps/2007_014.html

- Den Broeder, L., et al., 2016. Citizen science for public health. Health promotion international, 33 (3), 505–514.

- Drazkiewicz, A., Challies, E., and Newig, J., 2015. Public participation and local environmental planning: testing factors influencing decision quality and implementation in four case studies from Germany. Land use policy, 46, 211–222. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.02.010

- Environment and Planning Act of the Netherlands 2021 [ Available from: https://iplo.nl/regelgeving/omgevingswet/english-environment-and-planning-act/?_ga=2.58206250.1862379934.1654697553-27080818.1654697553.

- Eriksson, E., Fredriksson, A., and Syssner, J., 2021. Opening the black box of participatory planning: a study of how planners handle citizens’ input. European planning studies, 30, 1–19.

- Garin, N., et al., 2014. Built environment and elderly population health: a comprehensive literature review. Clinical practice and epidemiology in mental health: CP & EMH, 10, 103. doi:10.2174/1745017901410010103.

- Gebel, K., et al., 2011. Mismatch between perceived and objectively assessed neighborhood walkability attributes: prospective relationships with walking and weight gain. Health & Place, 17 (2), 519–524. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.12.008.

- Gibbs, G.R., 2007. Thematic coding and categorizing. In: Analyzing Qualitative Data [Internet]. London, England: SAGE Publications, Ltd; [38–55]. Available from: http://methods.sagepub.com/book/analyzing-qualitative-data.

- Gozalo, G.R., Morillas, J.M.B., and Gonzalez, D.M., 2019. Perceptions and use of urban green spaces on the basis of size. Urban for urban green, 46, 10.

- Grazuleviciene, R., et al., 2020. Environmental quality perceptions and health: a cross-sectional study of citizens of Kaunas, Lithuania. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17 (12), 14. doi:10.3390/ijerph17124420.

- Helleman, G., et al., 2021. Participatiemoe(d) (Tired of participation or participation courage): Platform Stad en Wijk. Available from: https://platformstadenwijk.nl/2021/06/28/participatiemoed/.

- Hendriks, A.-M., et al., 2014. ‘Are we there yet?’–operationalizing the concept of integrated public health policies. Health policy, 114 (2–3), 174–182. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.10.004.

- Institute for Positive Health, 2018. Helft van alle gemeenten Wil werken met positieve gezondheid (half of all municipalities want to work with positive health) [ Available from: https://www.iph.nl/kennisbank/helft-van-alle-gemeenten-wil-werken-met-positieve-gezondheid/.

- Jarvis, I., et al., 2020. Different types of urban natural environments influence various dimensions of self-reported health. Environmental research, 186, 109614. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2020.109614

- Kanarek, N., Stanley, J., and Bialek, R., 2006. Local public health agency performance and community health status. Journal of public health management and practice, 12 (6), 522–527. doi:10.1097/00124784-200611000-00004.

- Kärmeniemi, M., et al., 2018. The built environment as a determinant of physical activity: a systematic review of longitudinal studies and natural experiments. Annals of behavioral medicine, 52 (3), 239–251. doi:10.1093/abm/kax043.

- Kent, J.L. and Thompson, S., 2014. The three domains of urban planning for health and well-being. Journal of planning literature, 29 (3), 239–256. doi:10.1177/0885412214520712.

- Krefis, A.C., et al., 2018. How does the urban environment affect health and well-being? a systematic review. Urban science, 2 (1), 21. doi:10.3390/urbansci2010021.

- Kruize, H., et al., 2020. Exploring mechanisms underlying the relationship between the natural outdoor environment and health and well-being – results from the PHENOTYPE project. Environment international, 134, 105173. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2019.105173.

- Lalonde, M., 1974. A new perspective on the health of Canadians; a working document. Ottawa Ministry of National Health and Welfare Canada.

- Larsen, M., et al., 2014. Intersectoral action for health: the experience of a Danish municipality. Scandinavian journal of public health, 42 (7), 649–657. doi:10.1177/1403494814544397.

- Laverack, G., 2006. Improving health outcomes through community empowerment: a review of the literature. Journal of health, population, and nutrition, 24 (1), 113–120.

- Lge-Elegbede, J., et al., 2021. Exploring the views of planners and public health practitioners on integrating health evidence into spatial planning in England: a mixed-methods study. Journal of public health, 43 (3), 664–672.

- Lowe, M., 2018. Embedding health considerations in urban planning. Planning theory & practice, 19 (4), 623–627. doi:10.1080/14649357.2018.1496979.

- Morgan, D.L., 1997. Qualitative research methods: focus groups as qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc

- Mourits, K., van der Velden, K., and Molleman, G., 2021. The perceptions and priorities of professionals in health and social welfare and city planning for creating a healthy living environment: a concept mapping study. BMC public health, 21 (1), 1085. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11151-7.

- Mulliner, E., Riley, M., and Maliene, V., 2020. Older people’s preferences for housing and environment characteristics. Sustainability, 12 (14), 5723. doi:10.3390/su12145723.

- Nadin, V., et al., 2021. Integrated, adaptive and participatory spatial planning: trends across Europe. Regional studies, 55 (5), 791–803. doi:10.1080/00343404.2020.1817363.

- Operatie Steenbreek, 2018. Het goede van een groene tuin (The good of a green garden).

- Pereira, M., Nogueira, H., and Padez, C., 2019. The role of urban design in childhood obesity: a case study in Lisbon, Portugal. American journal of human biology, 31 (3), 9. doi:10.1002/ajhb.23220.

- Perez, E., et al., 2020. Neighbourhood community life and health: a systematic review of reviews. Health & Place, 61, 11. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102238.

- Putrik, P., et al., 2015. Living environment matters: relationships between neighborhood characteristics and health of the residents in a Dutch municipality. Journal of community health, 40 (1), 47–56. doi:10.1007/s10900-014-9894-y.

- Reed, M.S., 2008. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: a literature review. Biological conservation, 141 (10), 2417–2431. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2008.07.014.

- Rydin, Y. and Pennington, M., 2000. Public participation and local environmental planning: the collective action problem and the potential of social capital. Local environment, 5 (2), 153–169. doi:10.1080/13549830050009328.

- Salvo, G., et al., 2018. Neighbourhood built environment influences on physical activity among adults: a systematized review of qualitative evidence. International journal of environmental research and public health, 15 (5), 897. doi:10.3390/ijerph15050897.

- Shagdarsuren, T., Nakamura, K., and McCay, L., 2017. Association between perceived neighborhood environment and health of middle-aged women living in rapidly changing urban Mongolia. Environmental health and preventive medicine, 22 (1), 50. doi:10.1186/s12199-017-0659-y.

- Stankov, I., et al., 2017. Policy, research and residents’ perspectives on built environments implicated in heart disease: a concept mapping approach. International journal of environmental research and public health, 14 (2), 17. doi:10.3390/ijerph14020170.

- Stevens, Q. and Dovey, K., 2019. Pop-ups and public interests: agile public space in the neoliberal city. In: M. Arefi and C. Kickert, eds. The Palgrave handbook of bottom-up urbanism. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-90131-2_20#citeas

- Strydom, W. and Puren, K., 2014. From space to place in urban planning: facilitating change through participatory action research. WIT transactions on ecology and the environment, 191, 463–476.

- Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal, 2014. Memorie van toelichting omgevingswet (explanatory memorandum of the environment act). The Hague, The Netherlands. Available from: https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/kst-33962-3.html.

- van den Berg, M., et al., 2015. Health benefits of green spaces in the living environment: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Urban forestry & urban greening, 14 (4), 806–816. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2015.07.008.

- Verbeek, T. and Boelens, L., 2016. Environmental health in the complex city: a co-evolutionary approach. Journal of environmental planning and management, 59 (11), 1913–1932. doi:10.1080/09640568.2015.1127800.

- Wen, M., Hawkley, L.C., and Cacioppo, J.T., 2006. Objective and perceived neighborhood environment, individual SES and psychosocial factors, and self-rated health: an analysis of older adults in Cook County, Illinois. Social science & medicine, 63 (10), 2575–2590. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.025.