ABSTRACT

COVID-19 has heightened awareness of how housing design and quality can dramatically impact the mental and physical wellbeing of an individual. Adding to existing housing problems, long-term demographic changes, and failures in building maintenance as well as safety and housing design standards, the pandemic has exacerbated existing housing inequalities. Through 50 in-depth interviews with London residents conducted in early 2021, the paper studies how experiences of changing home uses and perception of the quality and design of domestic space affected the wellbeing of participants during the pandemic. The paper focuses on design-related housing aspects such as environmental comfort, the agency to make changes to a home, notions of privacy and security, and a lack of space. This reveals how changes in domestic use and future housing preferences might have a long-term impact on dwelling design. The wide-ranging lived experiences and subjective perceptions of the home call for a more inclusive approach to housing and social policies that consider the value of architectural design. Based on the findings and discussion, the paper concludes with housing design policy recommendations that should be taken into account to improve future housing quality and design.

Introduction

COVID-19 lockdowns restricted many to their homes for most of the day and highlighted serious housing failures and inequities. ‘Stay at home’ orders led to a heightened awareness of both positive and negative aspects of domestic interiors and changed how people experience and interact in their homes. As a result, housing problems and their effects on the physical and mental wellbeing of occupants were brought to the forefront.

Lockdowns cause by the pandemic added significant pressure on domestic space by exacerbating housing marginalisation, precarity, and inequalities around the quality of life and quality of spaces, causing new health and wellbeing challenges (Blundell et al. Citation2020, Richter et al. Citation2021, UNDP Citation2021). Already during the first lockdown (March to June 2020), 67% of social housing tenants in England reported that their mental health had deteriorated (Mind Citation2020). Non-decent and overcrowded housing conditions disproportionately affected those already in vulnerable housing situations and suffering from mental health problems (Moreno et al. Citation2020, Shakespeare-Finch et al. Citation2020). According to the Health Foundation, 39% of people living in overcrowded households in April 2020 showed signs of psychological distress (Tinson and Clair Citation2020) and also caused higher transmission rates of COVID-19 (Bambra et al. Citation2020, Tinson and Clair Citation2020, Kamis et al. Citation2021). 14 out of the 20 local authorities in England and Wales with the highest COVID-19 mortality rates also have the largest proportion of homes with fewer bedrooms than needed (Barker Citation2020). One third of British adults suffered from mental or physical health problems during the lockdowns because of their housing conditions and lack of space (NHF Citation2020).

Studies in Italy (Pancani et al. Citation2021), Chile (Duarte and Jiménez-Molina Citation2022), and Australia (Morris et al. Citation2020, Bower et al. Citation2021) found that the wellbeing of those living in inadequate spaces was more affected than those in secure, spacious homes with better access to amenities. For example, greater exposure to noise disturbances resulted in an 18% increase in anxiety (Bower et al. Citation2021). COVID-19 also changed individual health behaviours such as sleeping, exercising, diet, and alcohol consumption (Villadsen et al. Citation2021), which can affect how homes are used and perceived. While not all lockdown experiences were negative, with many, for example, welcoming aspects of homeworking (Holliss Citation2021), it increased existing housing inequalities. COVID-19 also revealed the impact of differences in available space per person depending on tenure and demographics. Younger people spent lockdown with less space than those in older age groups: older households aged 65+ have almost twice as much usable space than younger households (16-34) who are also twice as likely to lack access to a private garden than those 65 and over (Judge and Rahman Citation2020).

Even before COVID-19, lack of space shortage has a significant impact on health and wellbeing and raises questions about existing space and occupancy standards (Kearns Citation2022). The Building Research Establishment estimates that hazards in poor housing costs the National Health Services (NHS) in England £1.4 billion a year, but that the full societal cost, including long-term mental health, suffering, and trauma treatment is around £18.5 billion per annum (Garrett et al. Citation2021). The Centre for Ageing Better (Citation2021) also found that 4.1 million homes in England fail to meet the UK Decent Homes Standard, with damp, cold, mould, inaccessible, and disrepair causing long-term health problems, including almost 10,000 deaths a year due to cold homes. Poor housing conditions and lack of maintenance can be partially attributed to England having one of the oldest housing stocks in Europe, with 56% of homes in inner London built before 1945 (VOA Citation2015). Older housing requires greater, regular investment in maintenance and modernisation, which is sometimes lacking. Although houses are frequently converted into several dwellings, 26.6% of planning permission units don’t comply with the current nationally described space standard (Clifford et al. Citation2020).

Like other moments in history when health and social crises led to changes in housing policy, regulation, and provision, the pandemic offers an opportunity to re-evaluate design and space standards (Goode Citation2021). In times when habits are altered, interventions may be more effective given the opportunity to ‘renegotiate ways of doing things’ creates a need for new evidence in support of informed decision-making (Verplanken and Roy Citation2016, Richter et al. Citation2021). In England, the impact of housing policies can be traced back to the Housing Act of 1774 following the Great London Fire of 1666, which introduced the first comprehensive set of housing design regulations that led to the proliferation of standardised terrace houses. For this re-evaluation, an analysis of collective and individual changes in occupation and use is important to assess the housing inadequacy, expectations, and experiences that will inform long-term housing strategies and policy.

There is no agreed definition of ‘wellbeing’, which is often understood in overly broad terms (Dodge et al. Citation2012). In addition, the factors that shape relationships between housing and wellbeing are not always perceived equally. Many occupants in homes considered decent reported wellbeing problems during the lockdowns. For example, while statutory overcrowding rates are low, the impact of overcrowding on wellbeing partially depends on perception (Kearns Citation2022). This paper is therefore interested in the subjective perception of wellbeing inside the home, referring to how people individually experience and evaluate their space and the activities carried out in the home. According to the World Health Organisation’s Housing and Health Guidelines (Citation2018), housing should not only provide protection and comfort but also a feeling of home, ‘a sense of belonging, security, and privacy’, as well as positive interactions with the local community and access to public services and outdoor spaces. Consequently, neighbourhood aspects including outdoor spaces, pollution, and crime affect a person’s wellbeing (Young et al. Citation2004, Holding et al. Citation2020, Bower et al. Citation2021). In addition, economic factors such as affordability, income, and employment can determine wellbeing. Therefore, in order to develop inclusive assessment criteria of housing needs and wellbeing, the wider subjective experiences and perceptions of the home need to be taken into account.

While some research argues that policy should not depend on subjective indicators as these change over time (Sunega and Lux Citation2016), others however deem subjective wellbeing an essential measure of consumer preferences and social welfare (Kahneman and Krueger Citation2006). Lived experience studies can play an important role in social policy, as rather than generalising it is more inclusive of marginalised policy perspectives and needs (McIntosh and Wright Citation2018). Indicators of subjective wellbeing will be necessary to identify policy problems and consequences that are not captured by objective measures (OECD Citation2013b, Sunega and Lux Citation2016).

Existing research and surveys on health in relation to housing tend to focus on how environmental factors determine comfort and wellbeing. Studies often equate poor wellbeing to substandard and inadequate housing conditions and economic factors that result in well-known housing problems such as overcrowding, unaffordability or fuel poverty (Oswald et al. Citation2003, OECD Citation2013b, WHO Citation2018, Tinson and Clair Citation2020). Research has also dealt with health risks in relation to demographic characteristics, for instance, how an ageing population calls for greater regulation of housing accessibility and usability (Imrie Citation2003, Milner and Madigan Citation2004). Although during the lockdowns much research on housing was conducted, what is yet to be fully explored is what notions such as ‘quality’, ‘space’, or ‘design’ might mean to occupants and how their perception affects lived experience and wellbeing or shapes future housing expectations. Therefore, while some existing studies consider housing design standards, little attention has been paid to how poor design can affect a user’s mental and physical wellbeing To address this gap, this paper analyses the importance of design and layout to the usability and quality of domestic spaces in relation to subjective wellbeing.

Based on 50 semi-structured interviews of London residents in early 2021, the paper studies the relationship between wellbeing and housing design during the COVID-19 pandemic. Focusing on aspects of design and housing quality, this paper explores the following: 1) why the physical environment mattered to the wellbeing of occupants, 2) why the agency to make changes inside the home was important in lockdown 3) how changing socio-spatial relationships led to a shift in notions of privacy and safety, and 4) how dwelling size became even more problematic during the lockdowns. Individual housing experiences are compared by exploring how people understand design, layout, and housing quality with respect to their wellbeing. This discusses how the wide-ranging lived experiences and subjective perceptions of the home call for a more inclusive understanding of to housing and social policies but also the value that architectural design can bring to housing.

Methods

The research discussed in this paper is part of a larger study on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on home use and experience and subsequent changes in satisfaction with housing conditions and housing design. While this study also included an online survey (n = 1250) (Jacoby and Alonso Citation2022), this paper focuses on 50 semi-structured interviews with residents living in London and their subjective lived experiences at home during the pandemic. Home use and user satisfaction with dwelling space during the lockdown are specifically studied in regard to relationships between spatial environment, housing design, and wellbeing.

The interviews (28 March to 6 May 2021) took place during the phased exit from the third national lockdown in England. Although still mostly confined to their homes, participants were feeling hopeful in anticipation of workplaces, services, schools, and amenities reopening soon. By that time, participants had already experienced two prior lockdowns in 2020 (March – June and November – December 2020) and were thus able to reflect on these past experiences.

Interviewees were recruited through the online survey that took place before the interviews, with 435 of 1,250 respondents who fully completed the survey agreeing to participate in the interviews. From these, participants were selected based on three criteria: 1) respondents living in one- to three-bedroom dwellings to capture the most common property types in London (VOA Citation2015), 2) a balance between respondents who had made changes (n = 109) and those who had not made changes (n = 134) to their home during COVID-19 to understand the different reasons why, and 3) a mix from different London postcodes to ensure that the interview participants represent different experiences across the city.

During the initial research planning, an interview protocol was developed. This included a strategy for how to deal with questions or situations that interviewees might find distressing. The study was approved by the university’s Ethics Committee on 4th February 2021 (Application Number SJ/3/2020). Prior to the interviews, participants were asked for their consent form and to share floor plans and photographs of their home that would explain their housing. Interviews were held online via Zoom. Each interview lasted approximately an hour and participants received a small compensation for their time.

The semi-structured interviews began with general questions about the housing situation of participants: household composition, dwelling type, and daily routines of the participants. Following this, participants were asked about how they experienced COVID-19 at home and how this might have related to issues of housing design and quality. Conversations herby often turned to the experience of dwelling size, the environmental condition of their homes, what a high-quality home meant, changing home uses, and future housing aspirations. In the second half of the interview, topics that emerged during the conversation and seemed central to the particular lived experience of each participant were further explored. This included conversations about how past experiences and cultural expectations inform perceptions of housing conditions or what new types of interactions and experiences arose at home specific to lockdowns and COVID-19, such as working from home or having to self-isolate and shield.

Interview transcripts were analysed using principles of qualitative content analysis through a systematic process of classifying, coding, and identifying themes, with these categories representing both explicit and inferred communication (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005). Prior to the interviews, an initial codebook was developed inductively using the predetermined themes derived from the online survey responses (about the household composition, property type, quality and design of the home, and home use during COVID-19), as well as deductively, taking into account themes emerging from the interviews and notes from the lived experience of individuals (). Members of the team reviewed the codebook and, subsequently, a couple of interviews were coded. The codebook was edited and used again until a final codebook was established. Transcripts were also analysed through document variables to reflect key characteristics including age, gender, postcode, household composition, tenure, number of bedrooms, floors in the home, dwelling type, and number of years lived in the home. Transcribed interviews were coded and analysed using MAXQDA.

Table 1. Deductive and inductive coding categories

Findings

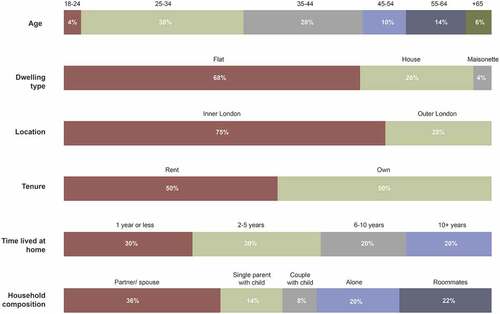

The interviewees represented a wide range of different household types, including working families, students, and pensioners (). In comparison to the interview participants, according to UK data, couples with dependent children made up 22% and one person 29.5% of all households in 2019 (ONS Citation2021b). COVID-19 has revealed the impact of differences in available space per person depending on tenure and demographics. In the interviews, ownership rates and access to private outdoor space was significantly higher in participants 55 years or older compared to those 25-34. Younger people had less space available to them than those from older age groups.

Based on the online survey conducted before the interviews (n = 1250), respondents spent on average 22-23 hours a day at home during the lockdowns, compared to only 13-14 hours prior, which meant that., for 68% of respondents COVID-19 changed how they and their household used their homes during a typical day (Jacoby and Alonso Citation2022). With an increased time spent at home, the space, size and design of dwellings had a notable impact on lived experiences. The home environment significantly influenced the comfort and mental and physical health of occupants. The main findings related to the home environment, the agency to modify spaces, changing socio-spatial relations, and dwelling size are discussed in the following sections through representative quotes from the interviews.

Home environment

Issues with natural light, temperature, and noise are some of the key stressors found in a home that can adversely impact wellbeing and how daily activities are performed. While problems with environmental factors did not necessarily change, the pandemic led to greater exposure. For example, complaints around thermal comfort and temperature control due to lacking insulation, ventilation, and old heating appliances were common. But during the interviews, less discussed environmental problems such as smell from a nearby waste facility, poor waste management, construction vibration, subsidence, or pests were also described as having an impact on wellbeing.

Noise was the most common, often pre-existing, housing problem exacerbated by the increased time at home during COVID-19. This is captured by a participant stating: ‘I think I’ve probably noticed it more since I’ve been here during the day’. Noise was considerably more of a problem in flats, where people lived in closer proximity. As one participant stated, ‘I feel like I am sharing this flat with my neighbours’, explaining how not being able to escape the noise was stressful, as it is ‘noisy from below, noisy from above, noisy from the side’. Some participants mentioned how construction work near their homes negatively affected their life, and how it was made worse by a sense of helplessness as they felt there was no solution to the problem: ‘You’d imagine drilling through concrete (…) And it’s really stressful, you can’t be wearing earplugs. You can’t concentrate’. Another recalled: ‘When they were demolishing the stuff and the whole ground would start shaking with us being trapped in the home (…) my heart rate, like, as soon as the shaking started, like, you had these spikes, and we couldn’t do anything about it. We actually complained to the council about the shaking, but they don’t really have shaking complaints so they didn’t really take it that seriously and it was just horrible’.

Dampness and mould were the main health hazards repeatedly mentioned in the interviews, caused by a lack of maintenance and poor construction or quality of building materials. Several participants raised how this resulted in health concerns, as it ‘triggered off my asthma’ or led to poor air quality and ‘pain in my chest’. While common issues in housing before COVID-19, prolonged exposure to dampness and mould increased health risks and affect the quality of life. One participant spoke about how the ‘amount of black mould is very depressing when you’re here 24/7’, while another described how they had to change how they use their homes as ‘there’s a corner where our rooms meet, where if you put stuff, if you keep things in that corner, then they just end up growing mould’.

12 out of 50 interviewees had also contracted COVID-19, and their experiences while sick and in isolation changed their perception of the home environment, as they became aware of shortcomings. One individual said that ‘I felt like the place was making me sicker too if that’s possible’. Another stated: ‘We only had lighting in the morning (…) which was beautiful but I never could, like, go into the window and feel that sun, and I think when you’re sick sometimes you need that, to get fresh air’. While many highlighted the negatives, some benefitted from the flexibility offered by their homes. This was the case for a participant and their spouse who slept in their front room to avoid going up the stairs: ‘When we were both really quite ill we probably spent about 10 days in that room. We have a downstairs toilet (…) it did serve a purpose in that we have a choice of rooms to suffer in, I suppose. And the facilities to find comfort and nurse ourselves’.

Agency to make changes inside the home

Being cooped up at home for a long time created a need to simply change one’s everyday surroundings: ‘Even just things like moving the furniture around in the room, just for a different perspective’. Likewise, ‘at the end of the summer, I just painted parts of my flat again a different colour, you know, just to make it feel different’. Overall, the interviews show that people started to think more about their homes, their use, design, and the wider environment. Thus, having control over their space gave occupants agency, which had a positive impact on their mental health and made being in lockdown seem more manageable. In the interviews, participants often discussed how being able to adapt their space during the pandemic to changing daily routines by rearranging furniture or undertaking repairs and renovations improved their living conditions. This included even small changes: ‘We’ve got some shelves in our room that have books on it but also, you know, like a framed art print and some fake flowers, and I just, yeah, it makes me so much happier having colours and fairy lights’. It was about a sense of control over one’s life, ‘having ownership over the space that you have’.

According to the interviews, two thirds of participants made changes to the layout of furniture or bought new furniture to accommodate changes in use. This was equally the case in rental and owner-occupied properties. However, owners talked more about plans for substantial and long-term changes to their homes such as large renovation projects, while renters spoke often about temporary measures such as painting or buying furniture. Changes in rental properties were often seen as difficult, as these had to be permitted by landlords or agents, even where repairs were essential. As one participant explained, ‘I put, like, a blanket on top of the sofa (…) because it was really brown, everything is like this brown, khaki. So, I needed more colour and the contract doesn’t allow us to paint any wall or anything’. In addition, a lack of ownership de-incentivised both financial and personal investment: ‘It’s just difficult when you know you’re living in a house with someone else’s furniture and someone else’s paint choices and I know there are so many things you can do (…) it feels like a waste to invest anything in making it nicer for the rest of the time here’. Apart from a lack of agency, ownership or permission, another critical factor preventing individuals from making necessary changes was a lack of space or knowing what to do. The experience of the pandemic and the importance of agency also influenced future housing choices.

Changing socio-spatial relations

The increased time at home during the pandemic changed people’s experience of domestic space as well as the meaning of key terms associated with the domestic environment such as privacy or safety.

The lockdowns led to a blurring of boundaries between daily activities that previously took typically place outside the home, such as work, exercise, leisure, schooling, and studying. Many participants found that retaining a physical and psychological division of spaces and activities was essential for their wellbeing, particularly maintaining a separation between ‘work’ and ‘home’ life. While some could divide activities using separate rooms, others had to rely on specific actions or routines to signal the start and end of their working day. Some used temporality to manage a lack of space, with many participants expressing how removing work-related equipment at the end of the day was beneficial to mentally disconnect from work. ‘Usually, the monitor moves off the table at the end of the day (…) I don’t have a permanent setup (…) So being able to kind of move it away is also very good as well just to kind of reclaim the space as a kind of, more of, a living area not just purely as a working area’. This strategy, while allowing a distinction between work and leisure, was in many smaller dwellings necessary to make the space available for other activities at different times.

The need to ‘reclaim’ or ‘negotiate’ space was particularly of great importance – as well as a cause of tension – for sharing households and carried significance beyond COVID-19 restrictions. One participant whose roommate was working from the dining room said: ‘[if] she works from home still after the pandemic, I don’t think she’s gonna have the screen anywhere near the dining room, I’m not letting her, to be honest, I hate it’s there, so that’s temporary’. Lack of space not only prevented activities but also created concerns about an equitable use of the home. As one participant reflected: ‘I wish I could have a separate workspace, like a separate room to go to work. Instead of making my family feel like a captor forced them to one part of the house, and I don’t want them to make a noise (…) I wish I had a bigger place so that I could possibly give them a bit more freedom instead of being stuck in a box’.

But those working from their bedroom or unable to move things had to find innovative solutions. Simple acts of removing something from view became psychologically important to restore their home from being a workspace: ‘I’ve got a piece of cloth to cover my computer screen with (…) this is like a mental thing to know work is finished’. Others adapted previous routines that helped them to prepare for or wind down from work: ‘before, I used to cycle to work, so I don’t have that active physical activity which I’ve kind of enjoyed, and so what I do now is, I have a big [walk] every morning’.

A lack of functional separation led to greater challenges in open-plan layouts. Some participants had to create distinct work and living zones by rearranging furniture, or even just mentally: ‘I managed to divide my living room into three spaces (…) so I will have dinner here in between, like just next to my desk but it’s like, in my mind, it’s a different space’. Similarly, someone else said, ‘It’s one big room but it still feels like three different spaces, and little things, like that, segment one big space into smaller zones, I think is helpful’. Where no strategy could be found to at least mentally separate from work, especially difficult in small homes, this often began to affect wellbeing. For a participant living in a studio, this problem was particularly acute: ‘There was no escape at all from work, and my role is actually quite a stressful role. So the impact on me wasn’t just that the space was a bit cluttered, it was just that actually I could never ever wind down because there wasn’t a separate room you could close the door on’. However, not being able to completely separate from work life was even problematic in homes with more space: ‘Before I would use this room to watch a movie or something (…) but I don’t really use this room for that much anymore because I associate it with work so, I suppose, if I had a larger home where I had a study that I could go to and that’s my workspace’.

New privacy problems arose with more working and learning from home. Beyond that of finding a space to work without being disturbed or disturbing others, there was the issue of exposing one’s private home to colleagues and strangers during online meetings, and the problem of maintaining appropriate work confidentiality. Many participants mentioned how video calls caused a lack of privacy unacceptable in a normal workplace. Some online meetings or work settings also required a neutral and professional background, limiting where one could work. Living with two teachers, one participant said: ‘he can’t teach from here, because you can see the bed and everything, so we’ve had to carve out a space in the living room that has no pictures on the wall and nothing you can see in the background’. For another, the challenge was to find a workplace to have confidential conversations while negotiating the needs of their homeworking partner: ‘I have a number of supervisions with my staff so it doesn’t always feel appropriate when you’re sitting about a metre away from somebody else, even if I’ve got headphones and so, if we both needed the space, then I might adapt something in the bedroom. I put the laptop on the top of the chest of drawers. Not necessarily the most ideal because there’s no way to get your legs if you’re sitting in front of the chest of drawers’.

Having sufficient space and flexibility to accommodate various privacy needs was a critical factor in how people experienced the lockdown. But even those living alone had to deal with unexpected intrusions into their privacy affecting their home use and routines. As someone living alone in a small place found: ‘Before, for instance, I would turn the machine on at night, I’d wake up in the morning, I’d hang the clothes and I’d go to work (…) this is the view that the Zoom people would have. I can’t have my clothes drying in the background. My room is really too small to fit the clothing’.

The constant, full occupation of the home during the pandemic thus restricted previously normal, private routines. Especially households with children or roommates spoke about the loss of personal time and space at home: ‘I just wanted to go to bed, but that’s the only time I get that privacy. The only time that I get ‘me’ time, because otherwise in, in the day when they’re around 24/7, I can't have a shower, like, you just can’t even take a phone call’. Another participant said: ‘I love to sit and read a book without interruption. And the most comfortable room for that is the living room, but given everybody works from home now there’s really very rarely ever a situation where I’m on my own and I can actually use that room just for reading’. In addition, in some cases, a lack of privacy was due to the layout of their home: ‘There’s no door between the kitchen and the living room. (…) If you’re watching TV in the lounge room and then if our housemate is in the kitchen cooking dinner, then you have to turn on captions on the TV because you can’t, suddenly, can’t hear and it’s, it’s just a really wacky layout’.

With the pandemic increasing activity around the home, privacy issues related to one’s neighbours that previously seemed insignificant could become a problem. For example, a participant who planned to move stated: ‘That is a bit of an issue for me, it’s probably the main reason I want to move. We have very, very low fences, and I don’t have any privacy out there. We also are very overlooked’. Similarly, another complained: ‘if the upstairs neighbours want to smoke, then they just go right outside the front door, which is also right outside our bedroom. So it means (…) if they don’t have privacy and they need to make a phone call, they’ll do it outside, so it means that quite a lot of the time we’ll get interrupted’.

Like privacy, aspects of security and safety in the home influence feelings of wellbeing and noticeably changed during the pandemic. For example, physical safety began to obtain added meaning related to self-isolation, social distancing, and protection from viral transmission. Additionally, problems of emotional safety and mental health increased due to social isolation and loss of human contact. Even though for many individuals the home became a refugee from the pandemic, others could feel unsafe. These opposing views demonstrate that experiences of safety, like that of other aspects of the home environment, is subjective and contextual. This is evident in how two participants living in a ground floor flat said: ‘this is the problem with being in a flat because I don’t want to have my bedroom at the front of the house. On the ground floor that just unnerved me a little bit, I feel safer and more secure sleeping in the back’. In contrast, the other found that: ‘after I got divorced, I felt secure in this self-contained flat, they had a buzzer entry’.

Most participants who contracted COVID-19 spoke about the fear of infecting household members and the greater social isolation but also the sense of insecurity this could cause: ‘My son’s a shielder, (…) and so he did keep away or I kept away from, I was still moving around the house, but my son locked himself in his room’. To effectively self-isolate was often impossible, as homes are traditionally designed for sharing. After a participant became sick after having to share essential facilities with their roommate, they found that: ‘the hardest bit was when we both had to come out to cook or use the bathroom (…) it could have been better off if we had our own ensuite’. As another pointed out, social distancing requirements substantially restricted the normal use of their shared home: ‘if someone is on their balcony, then I can’t go on my balcony, because we will be less than two metres apart from each other’.

Overall, social distancing also made people feel unsafe outside their homes, with some having to rely on public spaces such as local parks to find relief from their indoor confinement, as 13 out of 50 interviewees had no immediate access to outdoor space. A participant with children expressed the dilemma of going outside for their wellbeing but not feeling safe at the same time: ‘We had no outdoor space where we could sit comfortably and safely, or even privately (…) and it was playing on our mental health. Because in the summer when it got a bit brighter we didn’t really have anywhere to go. We would start to slowly take walks to the park, and that didn’t last very long because the first warm day everyone was. I felt very uncomfortable and very unsafe to be in the park with the boys’. The pandemic made participants more aware of their surroundings, such as their building or neighbourhood, which could increase their sense of insecurity: ‘Some of the people don’t like children playing in the communal areas. They said it is too noisy, which is sad and regrettable because in COVID children need to. I wish (…) they could go out and just feel safe to go in the communal area’.

Dwelling size and space

As the findings around privacy and safety during the pandemic show, they often directly relate to dwelling size and occupancy rates that determine available space. Perceptions and preferences around dwelling size fundamentally changed in some cases with the lockdown experience. While living centrally or close to public transport and work was previously often a priority that led to compromise on dwelling size, many began to question this as working from home made these choices obsolete: ‘We no longer feel that we need to be near tube station, although I might regret that, eventually I have to go back to the office’.

Some participants had expected in the past to spend much of their time away from home: ‘I was living in a studio, because, as I said, for me, it was a, you know, just a place to, where I go to bed and that’s it. So I didn’t really need much space, other than my own kitchen, my own bathroom, so these things are important for me, but I didn’t really need, for instance, working space. On the contrary, like, for me not having a working space is good (…) was a good way of separating the workplace from my flat’. However, with everything now compressed into the home, some found that they needed more space: ‘Home is no longer just a place for me where I sleep, I do expect home to, like, I do think I need a free space to actually put up a hobby area in the home, put up my music stand’.

With the amount of available space generally fixed for most participants, the experience of space shortage greatly depended on individual circumstances. In the worst cases, the pandemic caused feelings of being trapped and claustrophobia. One participant recalled what it was like after contracting COVID in her flat: ‘It was awful. It was absolutely awful. It was in the previous flat so it was just, it was just, ridiculous. I hated every second of it. (…) And yeah, I was just so tiny, it just felt like a prison, like we couldn’t even, like, go to the rooftop, so we’re just stuck there’. In particular, homeworking caused many problems including health-related issues, with interview participants reporting physical pain due to unsuitable furniture for work. Not having enough space led to a physical limitation of activities. This was most evident where activities would normally have taken place outside the home before, such as exercising. Among several similar replies, one participant said ‘I can’t do my arm sideways, one hits the unit that the TV’s on and the other one will hit the sofa, you know because the room isn’t wide enough to have all of those things’. Another participant mentions: ‘it is frustrating (…) there are days where I just want to exercise in my room and I can’t, because it’s too small, but I also can’t go to the living room because there’s my flatmates enjoying their time, (…) So I do feel that I’m being constrained by the space I live in now’. But space shortage also related to the repetition of more common domestic activities: ‘One of my biggest issues was storage because I was using the flat for a lot more than I used to, like cooking, and I needed more food. I ended up buying more pots and pans and things like this. My bike, I wasn’t using it that much so I kept it indoors, everything just seemed to be more’.

To those who had negative experiences of their previous homes, moving could make a significant difference to their quality of life: ‘Everything changed when we came here. I think my productivity just went up. I started working, way better. I had more energy, and also I had space to exercise, which I didn’t have in the previous flat (…) and I wasn’t feeling that I wasn’t affecting [his] space, he had his own private space and I had my own private space, and I think I had space to be myself, to my individuality’. Many of the quarter of participants who had moved, compared their new homes to their previous ones to illustrate positive changes in their living environment and justify their reasons for moving. Having more space or a different living arrangement became an important factor. For example, one participant said: ‘It was moving from a studio environment to being able to have sort of separate spaces. So, the space that we’re in now felt a lot bigger, with being able to have that balcony that you walk out on, a separate living space and kitchen and a separate bedroom’.

When asked about how much space is adequate, some participants complained how living ‘in these tiny rooms, it’s unhealthy’ and others suggested how ‘minimum requirements for bedroom space should be bigger’ or have ‘equal-sized bedrooms (…) divided a bit better’. Participants who felt they had more than enough space also emphasised that perhaps this should be the average space provision since they ‘have been able to do things that not everybody could but should be able to’. Most reflections were comparative in nature, even where more objective measures such as square meterage were considered. As one participant mused: ‘I guess, by London standards, it’s probably not a bad size. I think it’s somewhere around 65 square metres’. Another also discussed how their space compared to others with the same size, but how the layout was significant for usability: ‘I think that the one-bedroom flats in this estate have roughly the same square meterage as this. So, but the layout of my [flat] gives me this extra room (…) like that feels good for me because I like having an extra room, like I don’t think it would be more valuable for me to have a bigger living space’. Thus, dwelling size and usability are apparently understood in comparison to individual circumstances and experiences.

The COVID-19 experience made participants conscious of the effect of housing choices, with some participants feeling ‘proud’ and ‘happy’ for having chosen their homes based on clear ‘criteria in mind’, which ‘really paid off during lockdown because I haven’t felt as claustrophobic’. Others who moved during the lockdowns and re-evaluated their priorities found that choosing the right homes based on their new needs was ‘a massive factor in my mental wellbeing (…) I wake up, look around, just so happy to actually manage to live here’.

Discussion

As the interviews demonstrate, the suitability and quality of housing during the pandemic were largely perceived by occupants in terms of usability, but significantly depended on individual expectations and experiences. This finding aligns with international studies by the OECD, UN or WHO that increasingly focus on subjective quality of life indicators to measure living conditions (OECD Citation2013a, Randall et al. Citation2014, Sunega and Lux Citation2016). Among these indicators, personal security, environmental quality, and work-life balance are important measurements (OECD Citation2013a). Thus, the key concerns arising from the lived experiences of the pandemic are not necessarily new, but reveal a shift in meaning and greater housing inequalities.

As the findings also show that, an increased time spent at home during the pandemic gave participants greater awareness of both negative and positive aspects of their housing conditions, as has been observed also in other studies (Brown et al. Citation2020). Some participants used the words ‘not aware’ or ‘just noticing’ or ‘didn’t think about that’ to describe how their views on their homes changed. A representative statement of this experience is ‘I never saw it as an issue before, until lockdown’. This was particularly evident around issues related to environmental comfort, such as noise, that could occur at different lengths, intensities, or circumstances during lockdown. This supports findings in other surveys that found noise complaints increasing by 47.5% in London during the lockdown (Tong et al. Citation2021). Not only an increase in volume affected people’s wellbeing but also the saturation of noise, frequently coming simultaneously from people at home, traffic noise, and neighbours (Torresin et al. Citation2022).

Despite often directly related to their housing conditions, participants did not always relate their negative experiences to poor housing quality or design. Similarly, Attwood et al. (Citation2004) found that links between environmental conditions and wellbeing are not always apparent to occupants or observers. In fact, during the interviews, some participants were reluctant to speak negatively about their home, as they associated it with a safe space during the pandemic. However, when talking about what a well-designed home should be like, some declared ‘the opposite of mine’, using their home to illustrate shortcomings. Reflecting on how they lived in their homes during the pandemic, some realised how important housing design was to their everyday life. A well-designed home was described by one participant as ‘a space where you can go that isn’t impinging on someone else’s space in any way’ or ‘you know something is well designed when you don’t notice it’. Understanding the value of design enabled some participants to express their housing preferences more clearly and gave them a more specific definition of housing quality. It enabled some to ‘know what I’m looking for in a new place’.

With greater awareness of the shortcomings of their dwellings, the pandemic almost immediately changed the participant’s housing preferences. The interviews show a shift in the locations and housing types deemed desirable. While housing choices are commonly based on trade-offs, with access to certain amenities or a particular lifestyle preference coming at the expense of living in a smaller home (Preece et al. Citation2021), the pandemic made participants re-evaluate this. In particular, the lack of space made participants ‘reconsider being in London’ or how ‘with the checklist that I want, we’d have to leave London to get that’. Many interviewed thus considered moving or had moved, as ‘there was no point paying if we couldn’t take advantage of any of that’. Similar findings were reported in other surveys during the pandemic that found that one in seven wants to leave London as a result of the pandemic, however, many are unable to due to financial uncertainty, the cost of moving, or living in social housing (GLA Citation2021). As observed in the findings space, privacy, and security became priorities over concerns with living in central London or close to work and public transport. Also, a more articulate demand for flexibility in home use and layout emerged to coping with changing daily activities and routines.

This meant that in the interviews, several participants expressed the wish to change to move from a flat to a house. This is consistent with other studies during COVID-19 that observed an increase in demand for semi-detached and detached houses over flats and a reduced interest in central urban living (Amerio et al. Citation2020, Carmona et al. Citation2020, Mattarocci and Roberti Citation2020, Tinson and Clair Citation2020, Guglielminetti et al. Citation2021, Judge and Pacitti Citation2021). This comes as no surprise, given depression and anxiety is highest in people living in dense urban areas (Fancourt et al. Citation2020). Although a survey found that only 51% of private renters in England felt safe at home during the pandemic (Shelter Citation2020), in the interviews many participants spoke about how they had become aware of the value of good design for their wellbeing and how their home made them feel ‘safe and comfortable’ during COVID-19.

Consistent with research showing the positive effect of physical home improvements on mental health (Clark and Kearns Citation2012, Curl et al. Citation2014, Pevalin et al. Citation2017, Bower et al. Citation2021), many participants made changes to their space, particularly, to separate work, school, and home activities in a common response to lockdown-related changes in use (Brown et al. Citation2020). Wellbeing was also tied to the control, or perceived control, over their home (Brown et al. Citation2020, Channon Citation2020), with the interviews demonstrating how satisfaction and comfort in a home derived from the ability to personalise, rearrange, or redecorate it.

The findings demonstrate that having adequate space for daily activities is essential for healthy social-spatial relationships. As participants reported, having to improvise work or homeschool setups in living rooms, dining rooms, kitchen, or bedrooms, made it often difficult to separate them from traditional ‘home’ activities such as relaxing, playing, or household chores. As also found by others, this could significantly deteriorate mental wellbeing, reinforcing how essential a home designed for adequate detachment from work is to employee wellbeing (Wheatley et al. Citation2021). Many remote workers were not prepared for having to manage blurring boundaries between work and personal life, as also observed in studies by Toniolo-Barrios and Pitt (Citation2021) and Richter et al. (Citation2021). However, the interviews highlighted how dwelling size is often subjectively perceived in terms of individual needs and usability, and shaped by lived experience and socio-cultural expectations. One participant sharing a four-bedroom house with only their spouse found ‘the benefit of every room that we have, we don’t have a room that’s unused’, while another living in a flat without any living space still felt ‘this is perfect’.

But the wellbeing of participants was not only influenced by the amount or quality of space, with many emphatic that simply spending more time at home had an impact on their wellbeing, as it felt ‘like you are in a prison, even though it’s a nice place’. Some emphasised positive experiences, especially when able to work from home without restrictions, which offered comfort and made them feel ‘more relaxed’, as ‘I can get whatever I need when I needed’. Similarly, the Opinions and Lifestyle survey reported that 85% of adults currently homeworking express interest in a ‘hybrid’ model of working from home in the future, as they found this to be ‘an improvement to work-life balance’ (ONS Citation2021a).

Conclusion

The pandemic has led to some behavioural changes at home, which are likely to at least partially remain. Given the shift in housing preferences and demands, planners and designers need to re-evaluate the existing evidence base that might determine future planning needs. The continued need for homeworking will have implications for how we live, understand our work-life balance, and relate to our neighbourhoods and local communities. The lived experiences of the home as captured in this study highlights a need for the current nationally described space standards (2015) to account for a broader range of uses and activities when defining dwelling usability. Greater regulatory intervention is needed to ensure that space and occupancy standards are aligned. As the interviews reveal, the technical definition and measurement in square metres of spaces standards is alien to how most occupants evaluate their homes. While there is substantial research on how a lack of space and poor-quality housing adversely affects wellbeing, stronger evidence is needed to determine internal space standards and support making them mandatory. To improve housing quality and design, the following policy recommendations should be considered:

Making minimum space standards mandatory across all tenures and sectors while giving greater flexibility in the distribution of floor space to meet them. For example, permitting smaller but more rooms for uses such as homeworking.

Increase minimum standards for built-in storage.

Complementing existing technical evidence underpinning housing design standards with lived experiences, home use studies, and demographic data.

Including a wider range of home uses and household compositions in housing provision and design standards to cater to demographic shifts, for example, a growing ageing population, a rise in single-person homes, and an increase of non-related adults living together.

Making access to private outdoor space compulsory.

Supporting and funding local authorities to better enforce regulations in place that protect people from poor-quality homes.

Providing more grants for home improvements, particularly adaptations that will help reduce carbon emissions and improve environmental comfort inside the home.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lucia Alonso

Lucia Alonso is an architect and researcher. Currently she is a Research Associate in the Laboratory for Design and Machine Learning at the Royal College of Art.

Sam Jacoby

Sam Jacoby is Professor of Architectural and Urban Design Research, Research Lead of the School of Architecture, and Director of the Laboratory for Design and Machine Learning at the Royal College of Art.

References

- Amerio, A., et al., 2020. COVID-19 lockdown: housing built environment’s effects on mental health. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17 (16), 5973. doi:10.3390/ijerph17165973.

- Attwood, D.A., Deeb, J.M., and Danz-Reece, M.E., 2004. Environmental factors. Ergonomic solutions for the process industries, 111–156. doi:10.1016/b978-075067704-2/50006-4

- Bambra, C., et al., 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. Journal of epidemiology and community health, 74 (11), 964–968. doi:10.1136/jech-2020-214401

- Barker, N., 2020. The housing pandemic: four graphs showing the link between COVID-19 deaths and the housing crisis. Inside Housing. Available from:https://www.insidehousing.co.uk/insight/insight/the-housing-pandemic-four-graphs-showing-the-link-between-covid-19-deaths-and-the-housing-crisis-66562 [Accessed 8 February 2022].

- Blundell, R., et al., 2020. COVID‐19 and inequalities. Fiscal studies, 41 (2), 291–319. doi:10.1111/1475-5890.12232

- Bower, M., et al., 2021. ‘Trapped’, ‘anxious’ and ‘traumatised’: COVID-19 intensified the impact of housing inequality on Australians’ mental health. International journal of housing policy, 1–32. doi:10.1080/19491247.2021.1940686

- Brown, P., et al., 2020. Lockdown. Rundown. Breakdown: the COVID-19 lockdown and the impact of poor-quality housing on occupants in the North of England. The Northern Housing Consortium. Available from: https://www.northern-consortium.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Lockdown.-Rundown.-Breakdown.pdf

- Carmona, M., et al., 2020. Home comforts. Place Alliance. Available from: http://placealliance.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Place-Alliance-Homes-and-Covid-Report_2020.pdf

- Centre for Ageing Better, 2021. Getting our homes in order: How England’s homes are failing us. Available from: https://ageing-better.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021-02/Getting-our-homes-in-order.pdf

- Channon, B., 2020. How home design can impact our mental health. What Works Wellbeing. Available from: https://whatworkswellbeing.org/blog/how-home-design-can-impact-our-mental-health/

- Clark, J. and Kearns, A., 2012. Housing improvements, perceived housing quality and psychosocial benefits from the home. Housing studies, 27 (7), 915–939. doi:10.1080/02673037.2012.725829.

- Clifford, B., et al., 2020. Research into the quality standard of homes delivered through change of use permitted development rights. Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/902220/Research_report_quality_PDR_homes.pdf

- Curl, A., et al., 2014. Physical and mental health outcomes following housing improvements: evidence from the GoWell study. Journal of epidemiology and community health, 69 (1), 12–19. doi:10.1136/jech-2014-204064

- Dodge, R., et al., 2012. The challenge of defining wellbeing. International journal of wellbeing, 2 (3), 222–235. doi:10.5502/ijw.v2i3.4.

- Duarte, F. and Jiménez-Molina, L., 2022. A longitudinal nationwide study of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Chile. Frontiers in psychiatry, 13. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.744204

- Fancourt, D., et al., 2020. Covid-19 social study results release 14. UCL. Available from: https://www.COVIDsocialstudy.org/_files/ugd/3d9db5_d6f91f3ff2324a00a3273f466ceb699d.pdf

- Garrett, H., et al., 2021. The cost of poor housing. BRE Group. Available from: https://files.bregroup.com/research/BRE_Report_the_cost_of_poor_housing_2021.pdf

- Goode, C., 2021. Pandemics and planning: immediate-, medium- and long(er)-term implications of the current coronavirus crisis on planning in Britain. The Town planning review, 92 (3), 377–383. doi:10.3828/tpr.2020.50.

- Greater London Authority (GLA), 2021. Housing in London 2021: the evidence base for the London Housing Strategy. GLA Housing and Land. Available from: https://data.london.gov.uk/dataset/housing-london

- Guglielminetti, E., Loberto, M., and Mistretta, A., 2021. The impact of COVID-19 on the European short-term rental market. Covid economics: vetted and real-time papers, 68 (10.2), 115–138.

- Holding, E., et al., 2020. Exploring the relationship between housing concerns, mental health and wellbeing: a qualitative study of social housing tenants. Journal of public health, 42 (3), e231–e238. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdz076

- Holliss, F., 2021. Working from home. Built environment, 47 (3), 367–379. doi:10.2148/benv.47.3.367.

- Hsieh, H.F. and Shannon, S.E., 2005. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative health research, 15 (9), 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Imrie, R., 2003. Housing quality and the provision of accessible homes. Housing studies, 18 (3), 387–408. doi:10.1080/02673030304240Jacoby.

- Jacoby, S. and Alonso, L., 2022. Home use and experience during COVID-19 in London: problems of housing quality and design. Sustainability, 14 (9). doi:10.3390/su14095355

- Judge, L. and Rahman, F., 2020. Lockdown living housing quality across the generations. The Resolution Foundation. Available from: https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/app/uploads/2020/07/Lockdown-living.pdf

- Judge, L. and Pacitti, C., 2021. The resolution foundation housing outlook (no. Q2). The Resolution Foundation. Available from: https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/app/uploads/2021/04/Housing-Outlook-Q2-2021.pdf

- Kahneman, D. and Krueger, A.B., 2006. Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20 (1), 3–24. doi:10.1257/089533006776526030.

- Kamis, C., et al., 2021. Overcrowding and COVID-19 mortality across U.S. counties: are disparities growing over time? SSM - population health, 15, 100845. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100845

- Kearns, A., 2022. Housing space and occupancy standards: developing evidence for policy from a health and wellbeing perspective in the UK context. Building research & information, 1–16. doi:10.1080/09613218.2021.2024756

- Mattarocci, G. and Roberti, S., 2020. Real estate and the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe. New World Post COVID-19, 177–190. doi:10.30687/978-88-6969-442-4/013

- McIntosh, I. and Wright, S., 2018. Exploring what the notion of ‘lived experience’ offers for social policy analysis. Journal of social policy, 48 (3), 449–467. doi:10.1017/s0047279418000570.

- Milner, J. and Madigan, R., 2004. Regulation and innovation: rethinking ‘inclusive’ housing design. Housing studies, 19 (5), 727–744. doi:10.1080/0267303042000249170

- Mind, 2020. The mental health emergency: how has the coronavirus pandemic impacted our mental health?. Available from: https://www.mind.org.uk/media-a/5929/the-mental-health-emergency_a4_final.pdf

- Moreno, C., et al., 2020. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The lancet psychiatry, 7 (9), 813–824. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30307-2.

- Morris, A., et al., 2020. The experience of international students before and during COVID-19: housing, work, study, and wellbeing. University of Technology Sydney. Available from: https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2020-07/apo-nid307336.pdf

- National Housing Federation, 2020. Housing issues during lockdown: health, space and overcrowding. Available from: https://www.housing.org.uk/globalassets/files/homes-at-the-heart/housing-issues-during-lockdown—health-space-and-overcrowding.pdf

- OECD, 2013a. ”How’s Life? At a Glance”, in How’s Life? 2013: measuring well-being. OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/how_life-2013-6-en

- OECD, 2013b. OECD guidelines on measuring subjective well-being. OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/9789264191655-en

- Office for National Statistics (ONS), 2021a. Business and individual attitudes towards the future of homeworking, UK: April to May 2021. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/articles/businessandindividualattitudestowardsthefutureofhomeworkinguk/apriltomay2021 [Accessed 25 November 2021].

- Office for National Statistics (ONS), 2021b. Families and households. [Dataset]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/families/datasets/familiesandhouseholdsfamiliesandhouseholds [Accessed 2 March 2021].

- Oswald, F., et al., 2003. Housing and life satisfaction of older adults in two rural regions in Germany. Research on aging, 25 (2), 122–143. doi:10.1177/0164027502250016

- Pancani, L., et al., 2021. Forced social isolation and mental health: a study on 1006 Italians under COVID-19 lockdown. Frontiers in psychology, 12. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.663799

- Pevalin, D.J., et al., 2017. The impact of persistent poor housing conditions on mental health: a longitudinal population-based study. Preventive medicine, 105, 304–310. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.09.020

- Preece, J., et al., 2021. Urban rhythms in a small home: COVID-19 as a mechanism of exception. Urban studies, 004209802110181. doi:10.1177/00420980211018136

- Randall, C., Corp, A., and Self, A., 2014. Measuring national well-being: life in the UK, 2014. Office for National Statistics.

- Richter, I., et al., 2021. Looking through the COVID-19 window of opportunity: future scenarios arising from the COVID-19 pandemic across five case study sites. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 1–12. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.635686

- Shakespeare-Finch, J., et al., 2020. COVID-19: an Australian perspective. Journal of loss & trauma, 25 (8), 662–672. doi:10.1080/15325024.2020.1780748

- Shelter, 2020. Only half of private renters feel safe in their home during the pandemic. Available from: https://england.shelter.org.uk/media/press_release/only_half_of_private_renters_feel_safe_in_their_home_during_the_pandemic [Accessed 1 February 2022].

- Sunega, P. and Lux, M., 2016. Subjective perception versus objective indicators of overcrowding and housing affordability. Journal of housing and the built environment, 31 (4), 695–717. doi:10.1007/s10901-016-9496-3

- Tinson, A. and Clair, A., 2020. Better housing is crucial for our health and the COVID-19 recovery. The Health Foundation. Available from: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/long-reads/better-housing-is-crucial-for-our-health-and-the-COVID-19-recovery

- Tong, H., Aletta, F., Mitchell, A., Oberman, T., and Kang, J., 2021. Increases in noise complaints during the COVID-19 lockdown in Spring 2020: A case study in Greater London, UK. Science of the total environment, 785, 147213. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147213

- Toniolo-Barrios, M. and Pitt, L., 2021. Mindfulness and the challenges of working from home in times of crisis. Business horizons, 64 (2), 189–197. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2020.09.004Torresin.

- Torresin, S., et al., 2022. Indoor soundscapes at home during the COVID-19 lockdown in London – part II: a structural equation model for comfort, content, and well-being. Applied acoustics, 185, 108379. doi:10.1016/j.apacoust.2021.108379

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2021. Coronavirus vs. inequality. UNDP. Available from: https://feature.undp.org/coronavirus-vs-inequality/

- Valuation Office Agency (VOA), 2015. Dwellings by property build period and type, LSOA and MSOA. London Datastore. Available from: https://data.london.gov.uk/dataset/property-build-period-lsoa

- Verplanken, B. and Roy, D., 2016. Empowering interventions to promote sustainable lifestyles: testing the habit discontinuity hypothesis in a field experiment. Journal of environmental psychology, 45, 127–134. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.11.008

- Villadsen, A., Patalay, P., and Bann, D., 2021. Mental health in relation to changes in sleep, exercise, alcohol and diet during the COVID-19 pandemic: examination of four UK cohort studies. Psychological medicine, 1–10. doi:10.1017/s0033291721004657

- Wheatley, D., Hardill, I., and Buglass, S., 2021. Handbook of research on remote work and worker well-being in the post-COVID-19 era (Advances in human resources management and organizational development). 1st ed. IGI Global.

- World Health Organization, 2018. WHO Housing and Health Guidelines. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/276001/9789241550376-eng.pdf

- Young, A.F., Russell, A., and Powers, J.R., 2004. The sense of belonging to a neighbourhood: can it be measured and is it related to health and well being in older women? Social science & medicine, 59 (12), 2627–2637. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.05.001.