ABSTRACT

A growing body of research proves that city green spaces provide positive physical and mental health benefits. However, access is not universal. For many people with Autism Spectrum Condition (ASC), our cities can be difficult to navigate, due to the cognitive and social challenges inherent within the Built Environment. Problematically, cities are planned and designed by and for neurotypical people who commonly neglect the needs of those with disabilities. This paper aims to identify the impacts of the Built Environment on the walkability of a city for those with Autism Spectrum Condition. Using film, photography and recordings, two alternative journeys from a transport hub to a public park are analysed. A focus group consisting of parents of children with Autism Spectrum Condition aid the investigation by analysing the material gathered before suggesting potential solutions to the identified challenges. Suggestions included transition zones and provision of dedicated quiet places in the city, compartmentalisation of large spaces, utilising technology before journeys alongside improving safety and signage. Reflecting on the findings, this paper provides a number of urban design principles for the Built Environment, which consider those with Autism Spectrum Condition, that will make our shared Built Environment more inclusive for all.

1. Introduction

This piece of research relates to the city and its Built Environment. The city is a place of commerce, socialising, living and working. It is therefore fast paced and energetic. However, cities can also provide places of potential retreat such as parks and gardens that offer respite away from the dynamic associated with the urban. This juxtaposition within the city gives time for the average city dweller to purposely slow-down and restore, providing a sense of calm among their often-chaotic city lives. Green and blue spacesFootnote1 have been proven as vital for wellbeing through improving not only physical health but also mental health (Bowler et al. Citation2010; Kaplan Citation1995; Roe and McCay Citation2021; Ulrich Citation1983). This fact was strongly evidenced during recent lockdowns as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic when the health and well-being of city residents suffered if they were confined solely to their homes. The escape to greenery for daily exercise has proven essential for morale, physical and mental health (Fong et al. Citation2018, Ulrich et al. Citation1991, Venter et al. Citation2020).

However, the benefit of green space in cities is potentially lessened if there is not adequate access to it for all members of society. Unfortunately, access is not universal. There are many people who cannot comfortably travel to these beneficial city spaces. This can include those with physical, cognitive and social challenges. Included within these groupings can be people with Autism Spectrum Condition. Accordingly, this research identifies the challenges in accessing green spaces, specifically for people with autism, in the case study city of Derry/Londonderry, Northern Ireland.

2. Background

Autism Spectrum Condition (ASC) refers to a range of neurodevelopmental conditions characterised by a degree of impaired social behaviour, communication and language ability, which often align with a narrow range of interests and activities that are both unique to the individual and carried out repetitively (World Health Organization Citation2001). The level of intellectual ability in individuals with ASC is extremely variable and can extend from profound impairment to superior levels. Hence, it is a spectrum condition.

Moreover, many individuals with autism have difficulty in processing everyday sensory information and in cognitive functions (Hinder Citation2004) often compounded by sensorimotor dysfunction that can include difficulties in sensory responsivity and motor movements (American Psychiatric Association Citation2013). These factors combined, as noted by the travel writer with ASC mean that, ‘there are many hurdles to overcome in independent travel such as dealing with regulations and encountering many unknown people’ (Burge Citation2017, p. 3). As a result, this can then lead to people with autism avoiding going out or being unable to make journeys, leading to social isolation.

Globally, an estimated 1 in 160 children have an ASC (Mayada et al. Citation2012). This figure has been reported as higher for the UK at 1 in every 100 (Bancroft et al. Citation2012). In Northern Ireland, the rate of diagnosis of school children with ASC in 2019 was as high as 1 in 30 (Department of Health Citation2019) with more recent figures seeing an increase to 4.5% of school children having a diagnosis of ASC (Department of Health, Northern Ireland Citation2021). Based on studies conducted over the past 50 years, the prevalence of ASC appears to be increasing globally (Matson and Kozlowski Citation2011). There are many possible explanations for this apparent increase, including improved awareness, expansion of diagnostic criteria, better diagnostic tools and improved reporting. Irrespective of the reasons, the fact remains that there are many people with autism and other non-neurotypical conditions in our society for whom the Built Environment is a difficult landscape in which to travel.

Problematically, cities and their green spaces have been planned by and built for neurotypical people. This results in posing an issue of accessibility for people with ASC. As emphatically noted by a parent of a child with ASC,

… accessibility is directly related to the awareness of the people providing the services. If this is poor, the prognosis for accessibility is poor

It is therefore imperative that planners and designers understand the negative implications of designing a city primarily for neurotypical people with no disabilities. Planners and urban designers have a responsibility to ensure integration and inclusion for all. This includes supporting the wellbeing of marginalised sections of the population. Ensuring easy comfortable access to all the full range of amenities that a city can offer its citizens, including its parks and gardens, is an essential consideration within that responsibility.

Whist UK Planning Policy has attempted to promote inclusive and user-friendly urban environments; ASC is still not explicitly considered under any planning policy in the UK. In a Northern Ireland (NI) context, in 2011 the NI Government implemented the Autism Act Citation2011. This placed a statutory requirement on its Department of Health to prepare a report on the implementation of the Autism Strategy and Action Plan by Northern Ireland (NI) Government Departments. The theme of ‘Accessibility’ set out a strategic priority to ‘eliminate the barriers that autistic people face in accessing the physical environment, transport, goods and services’ (The Northern Irish Executive Citation2013, p. 53). Yet, subsequent NI Government Primary Planning Documents such as the Strategic Planning Policy Statement (Department of Environment Citation2015) for NI fail to address specific actions needed to meet the needs of those with disabilities. Additionally, despite the NI Public Health Agency being a key stakeholder in the Derry City Green Infrastructure (GI) Plan 2019–2032, which covers the region where this research was based, disabilities have only been referred to once in the entire document. Accessibility is referred to with explicit reference to the positive impact increased access has to mental health, yet this is with reference to a neurotypical population (Derry City and Strabane District Council Citation2019, p. 23). Autism is not mentioned, highlighting that whilst there is an aspiration for a more inclusive approach to including those with autism within NI society, implementing and ensuring this is proving to be difficult. This unfortunately is a pattern repeated elsewhere.

Currently, the majority of ongoing research that explores how planning can improve autonomy of people with ASC focuses on the criteria for the design of closed, separated and private spaces devoted exclusively for people, and in particular, children with ASC (Beaver Citation2003, Citation2006, Citation2010, Humphreys Citation2008, Mostafa Citation2008, Vogel Citation2008, McAllister and Maguire Citation2012). Very little research explores the impact of the overall urban environment for those with ASC, meaning there is no set criterion for ASC considered urban design. Hence, this paper examines some of the problems in a city faced by those with ASC when simply trying to access a public park on foot. As good quality urban planning and design have the ability to both enhance the quality of life and support those with autism, research into this area is justified and meaningful.

The city of Derry/Londonderry was used as a case study, not least as it is a good test case for assessing accessibility. This is due to its busy built environment, uneven (hilly) street topography and both formal and informal street layouts. It is therefore a challenging environment for those with ASC and other non-neurotypical conditions. It does though provide a number of beneficial, restorative spaces within the city. Hence, it offered the opportunity to select journeys that would be representative of many of the negotiations and challenges confronted by those with ASC in other cities.

3. Methodology

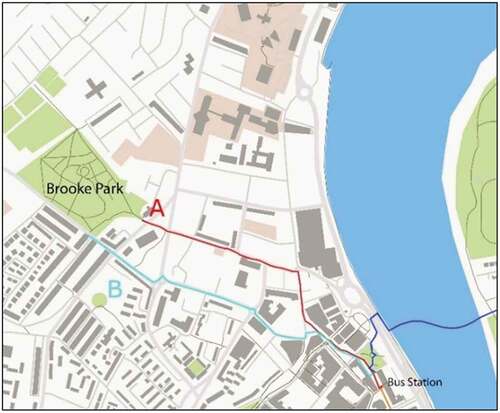

Data was collected through recording two pedestrian routes of similar distance illustrated in overleaf. Both started at a public transport hub, the Foyle Bus Station, and terminated at an open green space in the city, Brooke Park. These represented the most common routes people would take when arriving to the city by bus and then walking to the park. Analysis of the routes sought to identify some of the barriers and negotiations within the urban setting that may inhibit access to these positive green spaces for people with ASC. The fact that the chosen routes include the common challenges of negotiating footpaths, roads and shopping areas hopefully makes the observations and analysis applicable to other cities.

Beginning the analysis at a public transport hub was intentional. Aiding travel for parents and carers of people with ASC is important. Additionally, as there is an increasing number of young adults with ASC, aiding independence of travel without carers is vital. NI Public Transport Company ‘Translink’ has increased the awareness of ASC among their staff by the promotion of the ‘JAM’ (Just a Minute) cards (Now Group Citation2020). This is where staff receive training in helping those displaying the card who might need more time (hence the minute reference) on NI public transport. As a result, there may be an increase in the number of people with ASC using public transport independently. Therefore, the determined walking routes started at the Foyle Bus Station.

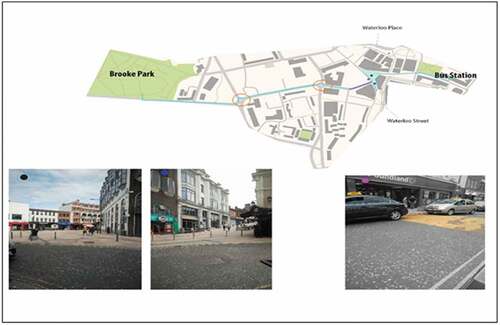

Choosing two routes was also purposeful. This afforded the opportunity to compare negatives and positives in both, thereby bringing a greater degree of criticality to the study. Both routes are approximately 1 mile in length and give a broad representation of the urban condition. This provided a view of accessibility both within the city centre, the less dense fringes of the centre and the open parks. Both routes are representative of commonplace townscape and therefore present the challenges frequently faced by those with ASC. Both started at the Foyle Bus Station and terminated at the entrance to Brooke Park, a large communal public park in Derry/Londonderry with Route A going via Great James Street and Route B via Waterloo Place.

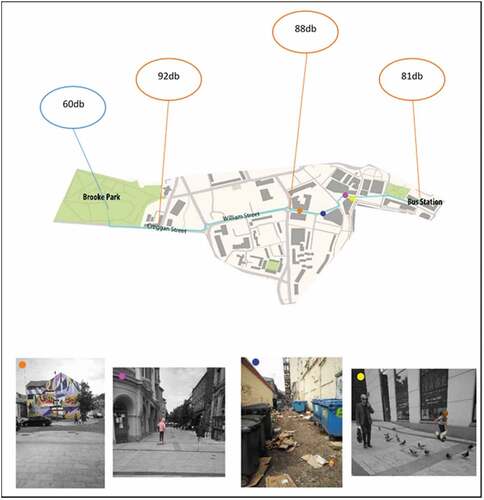

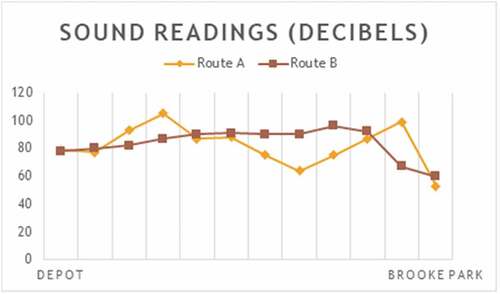

The two routes were filmed and photographed using a Samsung J3 Android phone. This allowed for a record of the journey to be kept meaning it could be then analysed afterwards for difficulties that a person with ASC might have that a neurotypical person would not notice on the walk. Sound readings were also taken at key points along the route. Each was taken for 30 seconds with the average recorded in decibels. This was calculated using an application ‘Sound Meter-Decibel meter & Noise meter’ on the Samsung Android phone. Any caveats with the use of an app on a phone were overcome by the consistency of using only one type of application, meaning, sound readings could be compared relative to previous readings. As weather would have an impact on the journeys, weather conditions and lux (light levels) were also recorded and detailed.

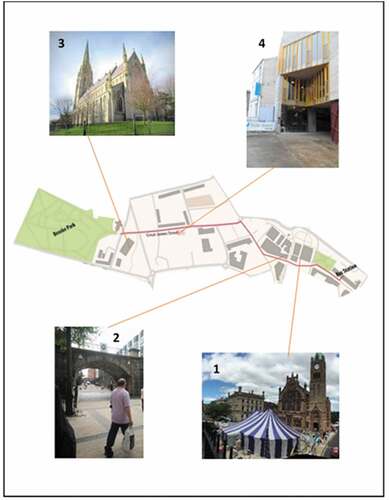

Photographing the journey was a very important aspect of this data collection. Prior research was vital in order to understand what aspects of the built environment might impede people with ASC. Identified barriers restricting independent access to the built environment included Public Awareness, Personal Space, Legibility, Crossings, Noise, Clutter, Lighting and Public Facilities (Sproule Citation2016, Cecchini et al. Citation2018). Whilst arguably subjective, landmarks were also highlighted along each journey (see overleaf). This was because landmarks ease wayfinding along routes as they increase the level of familiarity of the place (Lynch Citation1960).

The intention of using photography and film was to clearly identify any potential barriers as well as any aids to those with ASC on the two chosen routes. It was also an effective method of illustrating and sharing observations afterwards with members of a focus group, which may have been difficult to explain verbally. Hence, the medium provides an opportunity for understanding people who have difficulty conveying their views and feelings (Erdner and Magnusson Citation2011). Another advantage is that this method generated scope for obtaining a comprehensive picture of people’s lifeworlds (Seamon Citation1979), thereby capturing their perceptions of what is a nuisance. Moreover, this data-collection method afforded the potential for obtaining data that traditional interviews could never have provided. However, it needs to be recognised that photography as a data collection method is subjective (Kitchin and Tate Citation2000). To mitigate against this, it was important that the routes were photographed as comprehensively as possible. Then afterwards, with the help of the parents of children with ASC, in a focus group, the most impactful of the issues were identified. Ideally, mapping out and depicting routes must do more than just illustrate the journey. Because sensory issues can often be problematic for those with autism, any record also must give a sense of atmosphere and feeling too. That of course is difficult. However, it was hoped because the parents involved in the focus group would know the city, which would help mitigate against any weakness in using photographs. As parents with children with autism, beyond the children themselves, they would have an intimate knowledge of what their children would find difficult in terms of sensory stimuli.

After the on-site collection and initial analysis, a focus group sharing initial findings and analysis was undertaken with five mothers of autistic children all living in the Derry and Strabane District Council region, of which Derry/Londonderry is the main administrative centre. Council statistics (Derry City and Strabane District Council Citation2019) state that there were 29,325 pupils enrolled in schools across the Council region. That means if taking the Northern Ireland average of ASC incidence at 4.5%, there would be over 1,300 school children with autism in the Council region. The purpose of the focus group was to add rigour to the findings by giving families who have experience of living with children in the opportunity to critique the research and then share their opinions openly with the researchers. All volunteered to take part in the research after a call for participants was circulated by a regional National Autistic Society support group for parents of children. These families meet monthly for group activities such as attending dedicated cinema screening times with dimmed lights, during which the children have the opportunity to get up and walk about. As one parent noted, during these outings, their children ‘don’t have to follow societal rules to be quiet’. The support group also organised a trip to Euro Disney in Paris. This trip again highlighted the lack of level in preparedness in airports for assisting people with ASC where the airport barriers caused anxiety among some of the children.

Intentionally, because the volunteers were drawn from the same parents’ support group, it was hoped that the discussions would be shared, open and relaxed. Information sheets and consent forms were shared with all before participating in accordance with the researchers’ University Ethics Application. Details of the participants are illustrated in .

Table 1. Focus group participants.

The use of a focus group is especially appropriate when dealing with ASC since it is a spectrum condition. Every person is unique, with different symptoms and personality traits. The focus group therefore facilitated discussion and the identification of a broad range of issues pertaining to the study group, which represented a spectrum of ages and abilities. Hence, it is an appropriate and natural method of knowledge gathering about human interaction and everyday life (Cassell and Symon Citation2004). As noted, whilst measuring feeling can be difficult, this method allowed the parents to explain why their children felt a certain way about the built environment, which provided insight into sensory challenges. The relaxed and informal nature of the focus group allowed for an open discourse, which could include other topics useful to the research. However, to ensure the objectives of the research were being met, there were six initial pre-determined questions:

Is your child able to independently navigate around Derry/Londonderry?

What are the main issues faced when undertaking an outing to Derry/Londonderry?

Do you feel like Derry/Londonderry offers enough refuge for people with autism to get away from the sensory overload of the urban environment?

In your experience, does nature have a positive effect on your children? If so, please describe these benefits?

What are the barriers which may prevent you from taking your child out to a city or a green space?

Do you feel that access to Brooke Park is adequate for people with autism?

4. Data analysis

4.1. Route A

Both routes will now be described briefly in turn by way of contextualising the character of the Built Environment covered in the study. Broad observations will be first shared before communicating the more detailed thoughts and recommendations of the focus group. The initial analysis will be described separating sensory challenges and then cognitive and physical challenges.

Route A Foyle Bus Centre to Brooke Park via Great James Street

Weather Dry and sunny. Direct light lux levels 452,545.

Distance 810 metres

Travel Time 15-20 minutes

Vertical Climb 20.7 metres

Average Gradient 1 in 39

The landmarks along the route were recorded as.

The Guildhall and Square

The Walls

St Eugene’s Cathedral

Cultúrann Uí Chanáin

A section of this route, from the Guildhall to Cultúrann Uí Chanáin did not contain any landmarks. This part of the route includes two changes of direction. This section could prove difficult to navigate independently. It is important that street signage be more detailed in areas where there are no landmarks to aid with wayfinding. Larger public spaces (such as Waterloo Place on this route) with many exits may also result in confusion. Pictorial maps or city models may also be a helpful tool of wayfinding in such areas.

4.1.1. Sensory challenges along route A

Many sensory negotiations were encountered on this route, which may build up to create stimuli overload. The day was sunny meaning lux readings were generally high with the highest of 42,545 lux at the Guildhall Square and the lowest reading of 7,340 lux under tree coverage. Very bright light can be distressing to those with an oversensitivity, bringing on headaches. A lack of light can cause objects to become blurred or darkened for those with under-sensitive sight.

Many of the challenges encountered above were unavoidable negative outcomes of development and life within a city, yet the accumulation of these may be unbearable for someone with ASC. For example, a mother in the focus group explained that her son is extremely sensitive to noise, explaining that it would be difficult to;

Walk into a park with loads of people, so many noises going on.

The possibility of encountering a drilling sound on a walk may prevent the mother from taking her son to the park along that route. The parents also agreed that they could only go to public parks with their young children when the parks were quiet. Therefore, prior knowledge of when the park cleaning machines, lawnmowers or leaf blowers would be used in the park would be useful. As unexpected loud noise levels may ruin a trip to the park for the child with autism who is sensitive to noise, the restorative effects of visiting the park for them and their family would most likely become negated. A mother explained that a trip to a green space can be ruined for a number of reasons, one being unexpected noise. She explained when organising a trip to a green space;

There are factors which mater, such as (the) time of day and how quiet it is.

Another parent stated that she;

avoid(s) big parks as they are too busy. Small pocket parks near home are better.

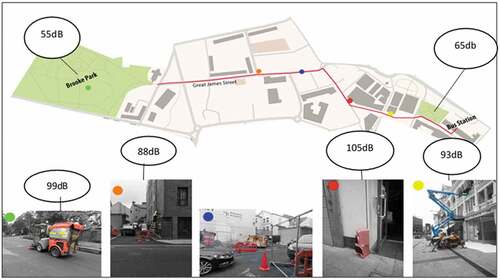

There is no universally accepted criterion for a sound level limit in public city gardens and urban parks. However, the WHO recommends a maximum LAeq value of 55 dB for exterior recreational areas (World Health Organization Citation2001). So, whilst the park offered a quiet environment of 55 decibels (as illustrated in ), anyone accessing it via the selected route would have had to overcome sound levels in excess of 100 decibels, which can be painful and distressing to many people.

4.1.2. Cognitive and physical challenges along route A

Cognitive and physical negotiations of the built environment are the challenges found in the built environment that require mental and physical effort to overcome. Many people with ASC experience proprioceptive and dyspraxic challenges due to impaired sensorimotor skills (Hannant et al. Citation2016, Coll et al. Citation2020). That means they can find it awkward to negotiate uneven surfaces and barriers. Additionally, they can find it difficult to judge personal space and so may also bump into people more frequently than neurotypical people. Those with autism may also have a vestibular sensitivity meaning that they may also have a tendency to look downward to confirm their location of the ground; thus, their sense of danger may be reduced (NAS Citation2020, Mansour et al. Citation2021). Cognitive issues may also include difficulty in concentrating and paying attention and difficulty in comprehending directions. Those with ASC can also present with patterns of apparent strengths and weaknesses in navigational abilities (Smith Citation2015, Ring et al. Citation2018). Hence for many people with ASC, navigating city streets in both the physical and cognitive realms can be distressing and even dangerous.

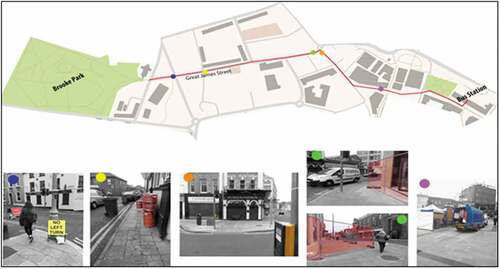

The selected photographs below () highlight some of the clutter produced by bins on streets, bars leaving barrels outside and associated ongoing construction. The distance between objects, be it a bin or construction gate and the road must be wide enough for someone with proprioceptive and processing challenges to get by. For anyone with proprioceptive challenges, this needs to be wider than for a neurotypical person. Furthermore, being forced to the edge of the footpath may be dangerous for someone with this condition. The van in the first picture is also an obstacle, which may not have been expected. The van presents the pedestrian with a decision of how to get around it, without getting in the way of another pedestrian. This could be difficult due to the presence of other people and is likely to increase feelings of anxiety.

Research and autobiographical writings by people with ASC also report traffic as a barrier preventing them from walking in towns or cities (Decker Citation2014, Davidson and Henderson Citation2017, Beale-Ellis Citation2017, Cecchini et al. Citation2018, Bogdashina Citation2016). Traffic lights are an aid to pedestrians and increase safety for people with ASC; however, more information at these points must be given. Standing still for some time at a traffic light may increase restlessness or cause unwanted disruption to a journey, as noted: ‘During journeys she dislikes waiting at traffic lights, due to the disruption’ (National Society of Autism, Adult Services Case Studies ‘Meet Grace’). Also, many neurotypical people crossed at the traffic lights (orange picture) when there was a ‘red man’. This can be confusing to someone with ASC. When considering this issue, all mothers agreed with Parent 4 who advocated;

Traffic lights with (a) timer – (then) you know you will get across.

It was also suggested that:

Signs should be very visual and easy and not (something) that you have to read and think, what does that mean and (then) figure out.

Therefore, there should be more information at traffic light crossings such as countdown timers and safety information signs.

4.2. Route B

Foyle Bus Centre to Brooke Park via Waterloo Street.

Weather Dry and sunny. Direct light lux levels 50,623.

Distance 1110 metres

Travel Time 20 minutes

Vertical Climb 42 metres

Average Gradient 1 in 26

This route has no landmarks beyond Guildhall as illustrated in . However, in comparison, it did have only one change of direction.

4.2.1. Sensory challenges along route B

Route B presented a time in Guildhall Square when more people were around than had been when Route A was recorded. A large group of young people were on a tour, which made the public square difficult to navigate. This might make the journey uneasy for someone with ASC, as might the distraction of the little boy chasing the birds (yellow). These are not elements of the built environment which can be prevented; however, these compounded with the preventable sounds of a skateboarder travelling across the stone paved square and the sight of a rubbish filled alley nearby may unnecessarily add to sensory challenges and unwanted feelings of anxiety.

4.2.2. Cognitive and physical challenges along routes

Basic street-crossing risks present many dangerous situations for pedestrians that require a unique set of skills to be able to navigate safely (Honsberger Citation2015). Teaching autistic children about street crossing safety is very important in the curriculum (Collins et al. Citation1991). However, it is difficult to put practice into reality when safety features of urban design are not maintained as in this example.

Confusion ensued at the point where Waterloo Place met Waterloo Street (see ). The crossing over to Waterloo Street is located outside a Poundland Store, about 20 metres from the meeting of the streets. Most pedestrians crossed on the corner. This direct desire line was popular because the designated crossing was worn away and therefore unclear, in addition to having taxis parked on the crossing (purple photo). This would be confusing for someone with autism as there are no clear instructions on what to do at this point. Roundabouts may cause a similar problem or where there is a crossing with no traffic lights. It is up to the pedestrian’s judgment where and when to cross. These areas need more information and instruction, not only for people with autism but also for neurotypical children.

4.3. Route comparison

Whilst here were fewer sensory negotiations along route B compared to route A, there were many more street-crossings and traffic-related issues despite there only one change of direction. This route had less unexpected construction and, other than traffic noise, there were few other unexpected sensory issues. This is depicted in , which identifies points of construction that caused a spike in the audio levels in Route A, compared to a relatively flat line for Route B.

Hypersensitivity to sound is one of the most common sensory processing dysfunctions for those with ASC (Gomes et al. Citation2004). The following quote highlights the unease that the noise of a passing car can cause they would explode inside me and make me lose all sense of the way my body related to my surroundings. It was like being flung out into space – woosh – quite without warning. Sometimes I screamed and covered my ears (Gerland Citation2003, p. 28). Three of the parents agreed that their children were hypersensitive to sound with one parent recalling a time when her son asked:

Can you hear that? And it might be a car revving in the background outside, something that I would have in the very back of my mind.

Preference of routes would be subject to individual sensory conditions; for one individual, the constant noise of traffic on route B may be more of a nuisance than the unexpected occasional unexpected noise increase on route A or vice versa.

Evaluating routes in terms of not just distance but also cognitive, physical and sensory challenges provides planners with a guide to creating the best access routes to green spaces in an urban environment. The best route may not be the shortest but may instead have the least number of permanent sensory and cognitive challenges. Safety measures at road crossings may be easily improved, for instance, by using pictorial signage along route B, and although lowering the overall noise of traffic is not easy, a real-time app would be effective in updating real-time construction work and traffic, which are temporary elements of the urban environment.

5. Discussion and focus group suggestions

Presenting the initial findings and spending time with the focus group confirmed that quiet spaces such as sensory gardens, public parks and pocket parks are very beneficial to people with ASC. They allow for refuge from sensory pressures and help reduce anxiety when in urban environments. Comments highlighting the positive aspects of specific green spacesFootnote2:

St. Columb’s Park is spaced out and you don’t bump into people.

The playtrail in Derry is worth going to.

(Parent 2)

Oakfield Park is (a) great size and has small parts within (allowing visitors) to go away and come back.

(Parent 4)

The focus group also agreed that an uninterrupted, smooth and safe journey to any destination is desirable. However, in order to make this desire a reality, the focus group contended that interventions are necessary in our built environment. These are identified and described below.

5.1. Transition zones

An autonomous autistic person may access the city centre via public transport. If so, the bus or train station is their first point of contact with the city. Anxiety levels are likely to be increased by the journey, meaning that the transport station has an important role in either heightening or reducing this feeling. This potential makes the station an important transition zone. In effect, the transport hub (in this case Foyle Bus Centre) becomes the specific part of the city mediating between two different conditions, namely, that of being on a bus and the streetscape outside of the Bus Station. In the design of autism friendly schools, transition zones ‘help the user adjust their senses as they move from one level of stimulus to the next’ (McAllister and Maguire Citation2012). Such transition zones might not only be helpful at transport hubs but also between covered car parks and outside areas. They could also be useful at the entry points to large, enclosed shopping centres. A parent from the focus group highlighted that ‘the more neutral the colours are, the better’ for these zones.

Design Elements that would aid in a public transport stop or terminus becoming a comfortable transition zone might include:

Inclusion of translucent panels above exit walkways, thereby helping mediate between the interior and exterior realms where daylight would be slowly introduced.

Inclusion of wayfinding tools such as maps or models.

Use of low arousal colours such as cream (not yellow or white) used for walls.

Ensuring the area is kept clean and rid of any obstruction.

Ensuring that construction work should adhere to very clear guidelines relating to footpath width and pre-agreed hours when using heavy machinery.

On an urban design scale, cities should be thought of as places of varying sensory intensities. Derry/Londonderry provides a good example where the city centre and shopping areas present many sensory challenges while the historic core inside City Walls are quieter and calmer in comparison. Streets which link these two conditions could then also be thought of as transition zones. These transitional spaces would help prepare and mediate for the transition between the places of different characters in a city. For example, in Derry/Londonderry, Pump Street runs perpendicular to the busy Ferryquay Street. Pump Street is a one-way street, which includes smaller independent shops. It is also the main link to the Garden of Reflection and St. Columb’s Cathedral, two spaces of quiet retreat from the centre. This street has the potential to put an individual at ease, rather than bombard them with sensory stimuli. Knowledge on where such transitional streets would aid parents/carers of autistic children and independent autistic adults when deciding what route to take to a destination. Design considerations to keep the transitional zones autism friendly would include ensuring that.

Advertisements, street art and elements that might constitute visual distraction are made illegal on identified transition streets.

Bollards are used only when essential and space between bollards is appropriate,

Greenery is added to the street,

Colours of buildings are muted,

Cyclists dismount and skateboarders walk,

Signage would be painted on the pavement rather than on poles,

Traffic speed is lowered.

These streets would provide time for those with autism to pause and ready themselves for the faster paced city beyond. Here, there would be low stimuli with ideally, no unexpected objects or activities present and with clutter completely removed. As a result, such designated areas of the city would be a safe section of their journey for those with autism. For businesses or outlets wanting to advertise in such areas, it is understood that signage can be an important part of their business advertisement. A potential solution to this negative outcome would be to incorporate these businesses onto an independent business map of the city and advertise these within buildings.

5.2. Road safety

Road safety is an issue for many children and adults with autism (Clements and Zarkowska Citation2000). It was recommended by the focus group that more detailed information be given at road crossings. This might include images to aid understanding. There are many reasons why images are useful at road crossings for those with autism, including the facts that,

PECs (Picture Exchange Communication Systems) are often used in communication between a person with autism who will present a single picture of a desired item or action to a ‘communicative partner’ who immediately honours the exchange as a request (Charlop-Christy et al. Citation2002, Howlin et al. Citation2007, Jurgens et al. Citation2009).

For those with autism, visual supports are used to structure daily routines (Drybjerg and Vedel Citation2007, Gammeltoft and Nordenhof Citation2007, Gaudion and McGinley Citation2012, Tola et al. Citation2021).

Visual supports can help to provide structure and routine, encourage independence, build confidence, improve understanding, avoid frustration and anxiety, and provide opportunities to interact with others.

The parents in the focus group also suggested that signs should be straightforward, so the individual does not have to decipher the meaning.

Signs should be very visual and easy and not that you have to read it and think, what does that mean and figure it out

Signs would be extremely useful at a busy road crossing. In order to streamline the process of addition of road safety signage, road crossings could be listed based on a hierarchy of danger shown in . For example, traffic lights minimize danger so do not need a full instruction list as the decision when to cross is not up to the individual. To overcome the problem of crossing at the wrong time, a simple sign stating to wait for the green man would be sufficient. However, traffic lights have been found to be disruptive to the schedule of a journey. Here, a countdown timer would reduce the potential for anxiety. While roundabouts on a main road with no traffic lights are more dangerous, thus the signage should be more detailed here with clear instructions. A suggested hierarchy of road crossings is illustrated below.

5.3. Provision of quiet spaces located away but close to main public spaces

Derry/Londonderry presented the perfect opportunity to create spaces on routes slightly away from main thoroughfares. These are not specifically placed separate to the city centre, yet they offer the possibility of quiet and retreat. It is important that planners and urban designers identify these spaces and:

incorporate comfortable street furniture,

keep the space free of too many stimuli,

add greenery,

reduce bright, fluorescent lighting.

The focus group highlighted the importance of creating spaces that are useable for all members of the public. This would reduce the level of stigma associated with autism and the ‘need to be taken away’.

I could say oh look at this quiet place we can go to for a while and then come back to the main area. Sometimes it can feel like a punishment [to the child], like we are taking you away because you are the problem

Provided there is effective upkeep, this could be a safe place of refuge. Such spaces equate in character to quiet rooms in an educational environment. They should not, however, be isolated or distant as they need to facilitate integration. In effect, what is needed is quiet that is readily accessible, as described as:

Space to go to, without being far away from everything else.

5.4. Compartmentalisation

The focus group commented on the need for large public green spaces to have multiple uses and spaces. This would mean if one part of the park was becoming distressing to the child or adult, they could then move on to a different environment within the overall space. The individual does not feel forced to leave the park; rather, they can move on from a distressing area to more serene area. This deals with the issue of isolation and exclusion highlighted in the focus group. This design makes the large space feel more manageable. It is important that inner city green spaces incorporate this design principle, rather than only purpose-built spaces. Gaudion and McGinley’s (Citation2012) design guide for gardens for adults with autism is a tool, which can be used to create compartmentalised green spaces. The guide includes a criterion for creating a variety of green spaces within one area. Each of these spaces having a definition and therefore a specific design, listed as: escape, exercise, occupation, sensory, social, transition and wilderness. Providing a variety of activity spaces allows a person to engage in social activities on their own terms. Any future proposed greenways or green spaces should be required to follow a compartmentalisation design guide in order to provide a variety of uses and quiet spaces of retreat.

6. Conclusion

There are of course limitations to the outlined study. Firstly, it would be both arrogant and wholly wrong to think that implementing the suggestions made here alone might solve the challenges inherent in the city for those with ASC. Planning and design input is only one component to consider and one that ideally requires input from other experts, carers, therapists, parents and wherever possible, the those with autism themselves. However, it is an important element and if handled thoughtfully, one that can both aid the person with ASC feel more comfortable and confident on our cities.

Secondly, there are of course other considerations when dealing with the city worthy of additional study that fell outside the remit of this study, these might include transport, streetscape and different building typologies. Further interdisciplinary study would need to be undertaken to test both these and the suggestions made in the paper.

However, what can be stated with authority is that to facilitate the implementation of the outlined long-term design goals, it is essential that planners and policymakers change their neurotypically driven mindset of city planning and design. The issue of accessibility for people with disabilities and ASC should become common knowledge to those working in the built environment sector. To do so, a design guide for creating inclusive cities and communities for people with disabilities, making specific reference to people with ASC, needs consideration at a strategic level, then implemented at a city and town level. Future regeneration projects should include these interventions and design principles in the planning stages and through to implementation.

Innovators in the discipline of planning research should also identify pioneering solutions to the problem of neurotypical design in the built environment. For example, software has the potential to be beneficial to people with disabilities; ‘I still get anxious, and I get lost when I go out, but I am going to buy a sat-nav to help me’ (NAS, Stories, Karen 39). A feature of Google Maps, available in cities such as London, calculates routes, taking into account the needs of wheelchair users (Akasaka Citation2018). Presently, GAP REDUCE is an ongoing Italian research project concentrating on the needs of adults with ASC using Google Maps to show markers and routes with a database for Points of Interest (Congiu et al. Citation2018, Citation2020). This is similar to another app, PIUMA, which provides spatial support in the form of a personalized crowdsourcing map-agenda (Cena et al. Citation2017). Such apps are beginning to address the issues of unexpected interruption on journeys, providing alternative routes for not just those with autism, but also for their families and carers who might be planning journeys and would benefit from up-to-date data. In the interim for cities such as Derry/Londonderry, an alternative temporary version of an app is a cheaper, paper map of fixed negotiations, with a website link providing real-time information on construction disruption. The map should also have written information and rules on road safety and could serve as an educational tool for those teaching and looking after those with autism.

The city is a place often chaotic with sensory overload, which can be manageable for some, but not for all. The challenge is not only to increase the number of restorative spaces in the cityscape but to make radical changes in terms of on street advertisement, pedestrianisation, road safety, wayfinding tools, transition zones and biophilic design.

Just as our cities are populated by a wonderful diversity of people, we need to recognize this in providing a range of ‘rooms’ in the city that offer a variety of atmospheres and qualities. This would not only benefit those with autism but society at large. The American architect and educator Louis Kahn famously stated that a plan, whether it be of a house or a city is basically ‘a society of rooms’ (Kahn and Lobell Citation2008, p. 44). This simple but elegant idea is telling that not only are all of our environments, rooms of one sort or another, whether garden, park or street, all interconnect and are themselves a ‘society’. With this in mind, greater consideration of adjacencies, legibility and the transition spaces between different ‘rooms in the city’ would provide a richer range of urban environments that could appeal all.

This will result in a more inclusive society with far reaching positive effects, not only of benefit to those with autism but for all of those with and without disability in our society.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Keith McAllister

Keith McAllister is a RIBA Chartered Architect and a Senior Lecturer in Architecture at Queen’s University Belfast. As the extremely proud father of a wonderful son with autism, his particular research interest is in the relationship between Architecture and those with Autism Spectrum Condition (ASC) with an ongoing emphasis on highlighting the need for and benefits to all of a genuinely more inclusive built environment.

Aine McBeth

Aine McBeth is a project officer with Connect the Dots and brings a diverse multidisciplinary background with a BA in Human Rights, Geography & Economics and a Planning MSc. She has experience in research, policy review and policy writing. In past experiences Áine focused on collaboration with communities on the development of planning strategies in their locality. She is passionate about hearing from those usually left out of consultation processes, giving a voice to the underrepresented.

Neil Galway

Dr Neil Galway is a RTPI-accredited planner and the Director of Postgraduate Education in Planning in the School of the Natural and Built Environment. His research focuses upon planning policy and practice with an emphasis on shared spaces and inclusive design. Neil engages extensively with communities and the planning and other built environment professions as part of both his research and teaching.

Notes

1. Green space being an area of grass, trees or other vegetation set apart for recreational or aesthetic purposes in an otherwise urban environment. Blue space being water in a city such as a river, streams, canals, lakes and fountains.

2. St. Columbs Park is a seventy acre public park in central Derry/Londonderry; the Playtrail is a public exterior play and educational area including a woodland walk to the north of the Derry/Londonderry and Oakfield Park is a landscape of parklands, lakes, mature woodlands with walking trails and a heritage railway located just across the border in County Donegal.

References

- Akasaka, R., 2018. Introducing “wheelchair accessible” routes in transit navigation. Accessed from: https://blog.google/products/maps/introducing-wheelchair-accessible-routes-transit-navigation/

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (5th edition). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Bancroft, K., et al., 2012. The Way We Are: autism in 2012. London, UK: The National Autistic Society.

- Beale-Ellis, S., 2017. Sensing the city. An autistic perspective. London, UK: Jessica Kinglsey Publishers.

- Beaver, C., 2003. Breaking the mould. Communication, 37 (3), 40.

- Beaver, C., 2006. Designing environments for children and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Paper presented to the International Conference on Autism, Cape Town 22 August.

- Beaver, C., 2010. Autism-friendly environments, the autism file. 34: 82–85. Available from: https://issuu.com/gaarchitects4/docs/05_christopher-beaver-the-autism-fi

- Bogdashina, O., 2016. Sensory Perceptual Issues in Autism and Asperger Syndrome, Second Edition: Different Sensory Experiences - Different Perceptual Worlds. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Bowler, D.E., et al., 2010. A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health, 10 (456). doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-456

- Burge, G., 2017. Travelling on the autism spectrum. Morrisville, NC: Lulu.

- Cassell, C. and Symon, G., 2004. Essential guide to qualitative methods in organisational research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Cecchini, A., et al., 2018. Mobility policies and extra-small projects for improving mobility of people with autism spectrum disorder. Sustainability. 10 (9), 3256. doi:10.3390/su10093256

- Cena, F., et al., 2017. Personalized interactive urban maps for autism: enhancing accessibility to urban environments for people with autism spectrum disorder. In: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing, Maui, Hawaii. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery, 9–12.

- Charlop-Christy, M., et al., 2002. Using the picture exchange communication system (PECS) with children with autism: assessment of PECS acquisition, speech, social-communicative behavior, and problem behavior. Journal of applied behavior analysis, 35 (3), 213–231. doi:10.1901/jaba.2002.35-213

- Clements, J. and Zarkowska, E., 2000. Behavioural concerns and autistic spectrum disorders: explanations and strategies for change. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Coll, S.M., et al., 2020. Sensorimotor skills in autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. Research in autism spectrum disorders, 76, 101570. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2020.101570

- Collins, B.C., Wolery, M., and Gast, D.L., 1991. A survey of safety concerns for students with special needs. Education and training in mental retardation, 26, 305–318.

- Congiu, T., et al., 2018. Gap Reduce. A research & development project aiming at developing a tool for planning quality of urban life of people with autism spectrum disorder. In: A. Leone and C. Gargiulo (eds.), Environmental and territorial modelling for planning and design. Naples: FedOA Press, 383–391.

- Congiu, T., et al., 2020. Gap reduce. A research and development project to promote quality of urban life of adult people with autism spectrum disorder. European journal of public health 30 (Supplement 5). doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckaa165.1395

- Davidson, J. and Henderson, V.L., 2017. The sensory city: autism, design and care. In: C. Bates, K. Imri, and K. Kullman, eds. Care and design, bodies, buildings, cities. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 74–94.

- Decker, E.F., 2014. A city for Marc. An inclusive urban design approach to planning for adults with autism. ( Master’s dissertation). Manhattan, USA: Kansas State University. Available from: http://inclusivecity.blogspot.com/2016/06/a-cityfor-marc-perfect-city-for-people.html

- Department of Environment, 2015. Strategic planning policy statement for Northern Ireland (SPPS) Web Pages.

- Department of Health, 2019. The Prevalence of Autism (including Asperger’s syndrome) in School Age Children in Northern Ireland 2019. Available at https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/articles/autism-statistics

- Department of Health, Northern Ireland, 2021. Prevalence of Autism (including Asperger Syndrome) in school age children in Northern Ireland. Available from: https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/news/publication-prevalence-autism-including-aspergers-syndrome-annual-report-2021

- Derry City and Strabane District Council, 2019. Derry City green infrastructure (GI) plan 2019-2032.

- Dyrbjerg, P. and Vedel, M., 2007. Everyday education: visual support for children with autism. London, England: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Erdner, A. and Magnusson, A., 2011. Photography as a method of data collection: helping people with long-term mental illness to convey their life world. Perspectives in psychiatric care. 47 (3), 145–150. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6163.2010.00283.x

- Fong, K.C., Hart, J.E., and James, P., 2018. A review of epidemiologic studies on greenness and health: updated literature through 2017. Current environmental health reports, 5 (1), 77–87. doi:10.1007/s40572-018-0179-y

- Gammeltoft, L. and Nordenhof, M.D., 2007. Autism, play, & social interaction. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Gaudion, K. and McGinley, C., 2012. Green spaces: outdoor environments for adults with autism. London: Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design, Royal College of Art.

- Gerland, C., 2003. A real person: life on the outside. London: Souvenir Press.

- Gomes, E., et al., 2004. Auditory hypersensitivity in children and teenagers with autistic spectrum disorder. Arquivos de neuro-psiquiatria, 62 (3b), 797–801. doi:10.1590/S0004-282X2004000500011

- Hannant, P., et al., 2016. Sensorimotor difficulties are associated with the severity of autism spectrum conditions. Frontiers in integrative neuroscience, 10, 28. doi:10.3389/fnint.2016.00028

- Hannant, P., Tavassoli, T., and Cassidy, S., 2016. The role of sensorimotor difficulties in autism spectrum conditions. Frontiers in neurology, 7, 124. doi:10.3389/fneur.2016.00124

- Hinder, S., 2004. Keynote address to Good Autism Practice Conference, Oxford, 19 April 2004.

- Honsberger, T., 2015. Teaching individuals with autism spectrum disorder safe pedestrian skills using video modelling within situ video prompting. Thesis (PhD). Florida Atlantic University.

- Howlin, P., et al., 2007. The effectiveness of picture exchange communication system (PECS) training for teachers of children with autism: a pragmatic group randomised controlled trial. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 48 (5), 473–481. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01707.x

- Humphreys, S., 2008. Architecture and autism. Hasselt: UDDA.

- Jurgens, A., Anderson, A., and Moore, D.W., 2009. The effect of teaching pecs to a child with autism on verbal behaviour, play, and social functioning. Behaviour change, 26 (1), 66–81. doi:10.1375/bech.26.1.66

- Kahn, L. and Lobell, J., 2008. Between Silence and Light. Spirit in the Architecture of Louis I. Kahn. Boston & London: Shambhala Publishers Inc.

- Kaplan, S., 1995. The restorative benefits of nature: toward an integrative framework. Journal of environmental psychology 15 (3), 169–182. doi:10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2

- Kitchin, R. and Tate, N., 2000. Conducting research in human geography: theory, methodology and practice. London: Routledge.

- Lynch, K., 1960. The image of the city. Cambridge, MA: The Technology Press and the Harvard University Press.

- Mansour, Y., Burchell, A., and Kulesza, R.J., 2021. Central auditory and vestibular dysfunction are key features of autism spectrum disorder. Frontiers in integrative neuroscience, 15, Article ID: 743561. https://scirp.org/reference/referencespapers.aspx?referenceid=3256309

- Matson, J.L. and Kozlowski, M.A., 2011. The increasing prevalence of autism spectrum disorders. Research in autism spectrum disorders. 5 (1), 418–425. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2010.06.004

- Mayada, E., et al., 2012. Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders, Autism research, 5 (3), 160–179. doi:10.1002/aur.239

- McAllister, K. and Maguire, B., 2012. Design considerations for the autism spectrum disorder-friendly key stage 1 classroom, Support for learning. 27 (3), 103–112. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9604.2012.01525.x

- Mostafa, M., 2008. An architecture for autism: concepts of design intervention for the autistic user, International journal of architectural research, 2 (1), 189–211.

- National Autistic Society: sensory Difference, 2020. Available from: https://www.autism.org.uk/about/behaviour/sensory-world.aspx

- The Northern Irish Assembly, 2011. Autism Act (Northern Ireland).

- The Northern Irish Executive, 2013. NI autism strategy (2013-2020) and action plan (2013-2016).

- Now Group, 2020. Just A Minute Card. Available from: https://www.jamcard.org/

- Ring, M., et al., 2018. Allocentric versus egocentric spatial memory in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 48 (6), 2101–2111. doi:10.1007/s10803-018-3465-5

- Roe, J. and McCay, L., 2021. Restorative cities: urban design for mental health and wellbeing, London: Bloomsbury.

- Seamon, S., 1979. A geography of the lifeworld: movement, rest and encounter. 1st ed. London: Routledge.

- Smith, A.D., 2015. Spatial navigation in autism spectrum disorders: a critical review. Frontiers in psychology, 6, 31. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00031

- Sproule, E., 2016. Inclusive urban design considerations for people living with autism spectrum disorder. Thesis (MSc). University of Surrey.

- Tola, G., et al., 2021. Built environment design and people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): a scoping review, International journal of environmental research on public health, 18 (6), 3203. doi:10.3390/ijerph18063203

- Ulrich, R.S., 1983. Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In: I. Altman and J.F. Wohlwill, eds. Behaviour and the natural environment. New York: Plenum Press, 85–125.

- Ulrich, R.S., et al., 1991. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. Journal of environmental psychology 11 (3), 201–230. doi:10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80184-7

- Venter, Z., et al., 2020. Urban nature in a time of crisis: recreational use of green space increases during the COVID-19 outbreak in Oslo, Norway. Environmental research letters. 15 (10), 10. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/abb396

- Vogel, C.L., 2008. Classroom design for living and learning with autism, Autism Asperger’s Digest. Available from: https://www.zearautismresources.com/uploads/1/3/4/5/134550915/designshare__classroom_design_for_living_and_learning_with_autism_1_.pdf

- World Health Organization, 2001. Occupational and community noise, WHO fact sheet N258. Geneva: World Health Organization.