Today, cities continue to capture the world´s many challenges: escalating income inequality, racial and country of origin divisions, environmental pollution, emergent infectious disease contagion, and unsustainable growth that ignores the climate crisis … Today, we know cities as places that can both threaten and promote health.

–Mary T Bassett, Foreword of Urban Public Health Book: A Research Toolkit for Practice and Impact, Oxford University Press, 2020

Introduction

Urban health research has greatly improved in quality, quantity, and depth over the past 20 years. Just in the last decade, we have seen a large increase in publications, scientific journals, conferences, books, and courses. This growth highlights the fact that there is a large and growing amount of knowledge that could be translated into policies to improve population health and reduce health inequities in cities worldwide. At the same time, social processes such as urbanization, urban renewal, segregation, and gentrification, to name a few, along with the uninterrupted advance of climate change pose evolving challenges to population health, health equity, and environmental sustainability in cities.

The current Cities & Health thematic issue includes several examples of urban health research conducted across the globe focusing on health outcomes such as re-emerging infectious diseases and non-communicable diseases, while further developing urban environment measures and participatory methodologies, among others.

In this editorial, we first review current urban population processes relevant to health and then highlight several methodological challenges and research opportunities for urban health.

Global urbanization trends

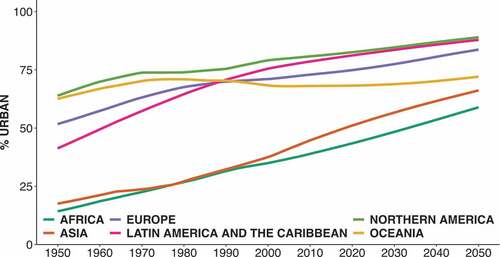

More than half of the world population currently lives in cities, and this number is expected to increase above two thirds by 2050 (UNDP Population Division Citation2018). shows urbanization trends by UNDP region. Urbanization is especially intense in Europe and the Americas, where 75 to 83% of the population currently lives in cities. Latin America has had one of the most rapid increases in urbanization, seeing its proportion urban population double from 1950 to 2020. While Africa and Asia have lower urbanization rates, urbanization has increased rapidly in these regions in recent years, and it is expected that later this century, these regions will be home to most of the world’s urban population.

Figure 1. Proportion of urban population by region.

Urban areas can be defined in several ways (Lovasi et al. Citation2020). First, administratively and politically, for example, US counties and cities, Spanish and Mexican municipios, Chilean comunas., cities can also be defined functionally, by aggregating several administrative or political areas with high levels of integration, for example, US core-based statistical areas, Mexican zonas metropolitanas, or European functional urban areas. To illustrate their differences, consider that in 2015, the administrative municipio of Madrid in Spain housed around 3.1 million people, while its functional urban area housed 6.6 million people. Second, cities can also be defined empirically based on the geographic extent of the built-up area using satellite imagery. For example, the SALURBAL study (Quistberg et al. Citation2019) uses several definitions of ‘cities’ including one based on satellite imagery.

Population health in cities

When studying the different ways and the intensity with which social and physical urban environments affect population health, it is important to bear in mind the different age structures of urban residents. The activity spaces that children and adolescents, adults, older adults, and the very elderly cover in their daily activities differ widely. Non-communicable diseases are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide including urban populations. Urban environments relate to non-communicable diseases through, for example, environmental pollution and physical and social environments conducive to sedentarism and unhealthy consumption of food, alcohol, and tobacco (Franco et al. Citation2015).

However, infectious diseases are also a major challenge for urban settings, including well-known re-emerging diseases, such as tuberculosis, as illustrated by the paper in this issue describing socioeconomic inequities among individuals with tuberculosis in metropolitan Detroit, Michigan, U.S.A. (Noppert and Clarke Citation2020), as well as newer emerging infectious agents such as COVID-19 (Diez Roux Citation2020). Migration, crowded housing, and social and economic interactions along with temperature and other climate-linked changes facilitate transmission at the same time that urbanization disrupts ecosystems increasing the contact with vectors (Ebi et al. Citation2021).

Urban environments can also be both protective and hazardous for mental health. Urban living can not only promote social connections but can also be linked to high levels of stress and social isolation contributing to depression and other adverse mental health outcomes (McCulley et al. Citation2022). Lack of natural spaces in cities has been linked to lower levels of emotional well-being and other dimensions of mental health (McCulley et al. Citation2022).

Social and health inequities in current cities

A key component of promoting urban health is understanding and addressing social inequalities in health. Since the place of residence is strongly patterned by social position in most cities, neighborhood characteristics become important contributors to health inequities (Diez Roux Citation2007, Citation2022). A pervasive way in which urban population health is affected by social processes is reflected in differences in disease outcomes across individuals by race social class and also across neighborhoods by levels of poverty and residential segregation (Diez Roux Citation2007, Citation2022). This Cities & Health issue includes a study describing a comprehensive approach to examining urban health inequities in non-communicable disease risk, using data from the city of Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India (Pomeroy-Stevens et al. Citation2021).

Climate change and health inequities in cities

Urban residents are especially vulnerable to the adverse health implications of climate change (Ebi et al. Citation2021). For example, increased temperatures in cities directly impact health and exacerbate the health impacts of other environmental factors such as air pollution (Ebi et al. Citation2021, Kephart et al. Citation2022). Climate change also leads to changes in rainfall; in addition to their direct impact on health-related infrastructure, floods can affect the transmission of infectious diseases through ecologic changes and facilitate vector-borne infections. Urban centers are warmer than the surrounding rural areas due to the urban heat island effect (Ebi et al. Citation2021), a consequence of both the heat absorbing and holding (heat capacity) of most urban building materials and the reduced ventilation and heat-trapping of much urban form (in particular tall buildings). Heat generated directly from human activities and the limited amount of vegetation and water also play a role in this effect (Ebi et al. Citation2021). Hot ambient conditions and associated heat stress can increase mortality and morbidity, as well as increase adverse pregnancy outcomes and negatively affect mental health (Ebi et al. Citation2021). As researchers and policymakers seek to contend with even hotter weather in the future, there is a pressing need to better understand the most effective prevention and response measures that can be implemented, particularly in low-resource settings, and identify sustainable opportunities for climate adaptation and resilience (Ebi et al. Citation2021).

Methodological challenges

We discern three main methodological challenges: the complexity of appropriate geo-referenced data and its availability, the comparability of these data across cities and across settings, and the policy translation of evidence generated through urban health research.

Data availability

Urban health studies generally focus on measuring two essential data points: (a) health outcomes and (b) contextual exposures. The need for different data sources, as well as the challenges inherent in characterizing urban processes and contexts as well as different health outcomes, makes interdisciplinary teams critical. Key sources of health outcomes data include vital registration data, surveys, cohorts, disease registries, and electronic health records (Lovasi et al. Citation2020). When examining a data source for use in urban health, it is important to understand whether the source includes a complete (or almost complete) census of all outcomes (e.g. complete vital registration systems and disease registries, and electronic health records in areas with integrated universal health systems) or a sample (e.g. surveys, cohorts, sample-based vital registration systems or disease registries, and electronic health records in areas without integrated universal health systems). Health outcomes data may be used to obtain representative estimates of population health (e.g. prevalence of diabetes in a specific city or neighborhood) or used in multilevel models to estimate associations with individual or contextual factors (Lovasi et al. Citation2020). Newer statistical methods have also leveraged survey and demographic data to obtain small-area estimates of prevalence of chronic diseases (Lovasi et al. Citation2020).

Contextual data are another key aspect of urban health studies (Lovasi et al. Citation2020). These may include social (e.g. socioeconomic status of a city), physical environments (e.g. neighborhood air pollution), and indicators that straddle both (e.g. overcrowding). Sources for these data include population censuses, which usually include features of individuals and households, surveys (e.g. employment surveys) and panels (e.g. consumption dynamics panels), direct measurement of exposures (e.g. air pollution monitors), remote sensing (e.g. urban extent measured through satellite imagery), and direct observation (e.g. virtual or in-person audits of street conditions) (Lovasi et al. Citation2020). Similar considerations as with health data apply here. A key issue is identifying the geographic scale at which the construct of interest is defined, and some constructs may refer to the city as a whole (e.g. urban fragmentation), but others may characterize smaller areas within cities or neighborhoods (e.g. access to health foods). Different tools can be used to characterize different contextual or environmental characteristics including satellite data, environmental monitoring, census data, rates or observers, or even surveys of residents who can report on the features of their surroundings (Lovasi et al. Citation2020).

This issue of Cities & Health includes several examples of analyses linking health to contextual and environmental data. A study conducted in Cook County, IL, describes socioeconomic factors and identifies vulnerable urban areas in relation to asthma prevalence (Lotfata and Hohl Citation2021). In another study, researchers validated a measurement tool, the Method for Observing pHysical Activity and Well-being (MOHAWk) that can be used both in policy or practice (Benton et al. Citation2020). In a third paper, researchers in urban India used a participatory research methodology, photovoice, to record residents perceptions of their environment and experiences with blue spaces in order to understand the links between blue spaces and health (Brückner et al. Citation2021).

Comparability across settings/cities

A challenging aspect of urban health studies, that is at the same time, an opportunity for research, is making valid comparisons across cities and settings. Comparisons require data to be of similar quality and harmonized so that indicators are comparable across settings (Morris Citation2018), a concept known as measurement equivalency. Lack of comparability results in measurement error (Morris Citation2018), which can result in erroneous conclusions regarding differences across cities or regarding associations between urban environments and health outcomes. Measurement error can result in associations that are biased towards or away from the null. For example, if countries or cities with more resources have improved measurement of cancer diagnoses, it may seem as if socioeconomic status is associated with increased cancer incidence, as cancer cases would be undercounted in lower resourced areas. Approaches to the harmonization of measures include carefully planning data collection before the study is conducted, after the study is conducted but before data are released or after data are released (Morris Citation2018). Urban health studies that rely on already collected data usually have to conduct ex post output harmonization (Morris Citation2018) by trying to make measures that were not designed to be directly comparable acquire measurement equivalency.

Policy translation of urban health research results and evidence

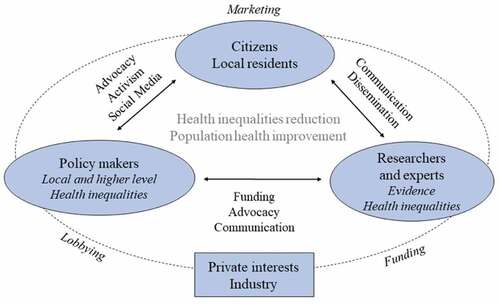

Interdisciplinary research that also partners with communities and policy experts is needed to prevent the major public health challenges of non-communicable diseases, emerging infectious diseases, and mental health problems in cities (McCulley et al. Citation2022). Citizens, policymakers, health professionals, and researchers should be aligned in an urban health agenda to effectively improve population health and help reduce health inequities. To make lasting change, on-the-ground different stakeholders (citizens, policy makers, health professionals ,and researchers) are required to act in different ways (Franco et al. Citation2018). depicts an action model of the elements required to build an urban health agenda (Franco et al. Citation2018). The use of evidence to inform policy and practice is often hampered by a poor fit between academic research and the needs of policymakers and practitioners. Gilles Corti et al. identified several strategies that can improve policy translation of urban health research including the inclusion of policymakers and practitioners as part of interdisciplinary research teams; focusing on explicitly policy-relevant research; adopting appropriate study designs and methodologies (evaluation of policy initiatives as ‘natural experiments’); and adopting dissemination strategies that include knowledge brokers, advocates, and lobbyists (Giles-Corti et al. Citation2015).

Figure 2. Stakeholders, processes, and strategies involved in a neighborhood and health agenda in relation to health inequalities and population health.

Research opportunities

The complexities inherent in understanding and acting on urban health problems require innovative approaches. These include comparisons across urban areas (cities and neighborhoods) within and across countries, the use of mixed methods, the use of systems approaches, and the evaluation of the health and health equity impact of the many policies that occur in urban areas.

Comparisons across urban areas

Comparisons across cities in the same or different countries can shed light on the impact of city-level factors themselves (rather than for example the specific features of neighborhoods), and many of these city features (e.g. urban fragmentation, segregation, and income inequality) are amenable to policy (Lovasi et al. Citation2020, Quistberg et al. Citation2019). City factors may also modify the impact of other characteristics. For example, observing differences in the magnitude of racial/ethnic disparities between cities suggest that race differences in health are not immutable or ‘natural’ but rather result from social processes (e.g. differences in residential segregation across cities).

Mixed-methods

Understanding the relationship of the social and physical urban environment with different population health outcomes and developing adequate and efficient preventive strategies will require the work of multiple disciplines, often with diverse methodological approaches including large-scale quantitative observational studies as well as qualitative studies of the ways in which people relate to and are affected by urban environments (Franco et al. Citation2015). The use of mixed-methods comprehensive approaches to complex urban health problems is important to designing public policies to improve urban health and address urban health inequities.

Policy evaluation

In order to stimulate the development and evaluation of urban health policies, The Lancet launched series in Giles-Corti et al. (Citation2016) and Giles-Corti et al. (Citation2022) exploring how integrated multi-sector city planning policy, including urban design and transport planning, can be used as an important force for health. The 2022 series offered a framework incorporating 11 integrated urban system policies and 11 interventions as well as methods and open-source tools to create upstream policy and spatial indicators for urban policy evaluation; to unmask spatial inequities; to inform interventions and investments; and to accelerate transitions to net zero, healthy, and sustainable cities (Giles-Corti et al. Citation2022).

Systematic and rigorous policy evaluation for urban health presents two important methodological challenges: first, the importance of policy surveillance, which allows for a systematic measurement of the policy environment in different cities. This also allows for the characterization of the specific features of policies, allowing also for the creation of policy databases, which can be linked to health data and used in policy evaluation efforts. The use of these databases has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, including, for example, the COVID-19 US State Policies at Boston University. Second, the need to carefully consider the statistical methods that are needed to draw meaningful conclusions such as difference-in-difference, controlled interrupted time series; synthetic controls allow comparisons of actually observed outcomes with the counterfactual that would have been observed had a policy not been implemented.

Systems modeling

However, policies and their combination are not always implemented in ways that allow for their evaluation or are not implemented in the contexts in which we would be interested in evaluating them. Simulation methods can be used to evaluate the plausible impact of policies under varying conditions and across contexts that may buffer or exacerbate their effects. A variety of systems-based simulation methods can be used for this purpose (Luke and Stamatakis Citation2012). More qualitative and participant engaged approaches can also be used to engage policymakers, and other stakeholders in identifying the key components of a system, their implications, and the possible levers for intervention in the context of these dynamics (Hovmand Citation2014). Systems approaches can also help identify non-intuitive effects and unintended consequences of established policies or even help identify new potential interventions or policies that had not been previously explored. Systems modeling also presents new challenges including the need to develop systemic conceptual models and the availability of the evidence and data needed to parametrize these models so that they reflect reality.

Conclusions

As social inequalities and segregation increase, and climate change advances unimpeded, the continuing process of urbanization poses both challenges and opportunities to improve population health in the billions of urban residents across the planet. This Cities & Health thematic issue brings together research studies across the globe that focus on varied health outcomes including re-emerging infectious diseases as well as non-communicable diseases. Importantly, these studies highlight the need for new and varied methods and support the need to always apply an inequality lens to urban health problems.

To conduct the most relevant and policy-oriented urban health research worldwide, we need to generate innovative data collection and analyses within interdisciplinary teams sharing data and results across cities. Designing meaningful research that can yield the types of evidence needed for urban policies and translating this evidence into population health improvement and health inequities reduction are pressing challenges in our urbanized (and urbanizing) world.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Manuel Franco

Manuel Franco, Social and Urban Epidemiologist, is an associate faculty at the University of Alcalá and adjunct faculty in two institutions in the USA: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the City University of New York CUNY Graduate School of Public Health.

Ana V. Diez Roux

Ana V. Diez Roux is Dean of the Dornsife School of Public Health at Drexel University, where she directs the Urban Health Collaborative and leads the Wellcome Trust-funded Urban Health in Latin America (SALURBAL) research project: http://lacurbanhealth.org. Her research areas include social epidemiology and health disparities, environmental health effects, urban health, psychosocial factors in health, cardiovascular disease epidemiology, and the use of multilevel methods. She is internationally known for her research on the social determinants of population health and the study of how neighborhoods, particularly urban neighborhoods, affect health.

Usama Bilal

Usama Bilal is Assistant Professor in the Urban Health Collaborative and the Department of Epidemiology & Biostatistics at Drexel's Dornsife School of Public Health. His primary research interest is the macrosocial determinants of health, specifically nutrition-related conditions and their upstream causes. Most of his work focuses on the role that city- and neighborhood-level dynamics have in generating disease, and the use of complexity methodologies to study the emergent properties of urban environments. He has earned degrees from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (PhD), Universidad de Alcala (MPH) and Universidad de Oviedo (MD).

References

- Benton, J.S., et al., 2020. Method for observing pHysical activity and wellbeing (MOHAWk): validation of an observation tool to assess physical activity and other wellbeing behaviours in urban spaces. Cities & health, 6 (4), 818–832. doi:10.1080/23748834.2020.1775383.

- Brückner, A., et al., 2021. Photovoice for enhanced healthy blue space research: an example of use from urban India. Cities & health, 6 (4), 804–817. doi:10.1080/23748834.2021.1917967.

- Diez Roux, A.V., 2007. Neighborhoods and health: where are we and were do we go from here? Revue d’épidémiologie et de Santé Publique, 55 (1), 13–21. doi:10.1016/j.respe.2006.12.003.

- Diez Roux, A.V., 2020. Population health in the time of COVID‐19: confirmations and revelations. The milbank quarterly, 98 (3), 629. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.12474.

- Diez Roux, A., 2022. Social epidemiology: past, present, and future. Annual review of public health, 43 (1), 79–98. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-060220-042648.

- Ebi, K.L., et al., 2021. Hot weather and heat extremes: health risks. The lancet, 398 (10301), 698–708. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01208-3.

- Franco, M., et al., 2018. Towards a policy relevant neighborhoods and health agenda: engaging citizens, researchers, policy makers and public health professionals. SESPAS report 2018. Gaceta sanitaria, 32, 69–73. doi:10.1016/j.gaceta.2018.07.002.

- Franco, M., Bilal, U., and Diez-Roux, A.V., 2015. Preventing non-communicable diseases through structural changes in urban environments. Journal of epidemiology and community health, 69 (6), 509–511. doi:10.1136/jech-2014-203865.

- Giles-Corti, B., et al., 2015. Translating active living research into policy and practice: one important pathway to chronic disease prevention. Journal of public health policy, 36 (2), 231–243. doi:10.1057/jphp.2014.53.

- Giles-Corti, B., et al., 2016. City planning and population health: a global challenge. The lancet, 388 (10062), 2912–2924. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30066-6.

- Giles-Corti, B., et al., 2022. What next? Expanding our view of city planning and global health, and implementing and monitoring evidence-informed policy. The lancet global health, 10 (6), e919–926. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00066-3.

- Hovmand, P.S., 2014. Community based system dynamics. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Kephart, J.L., et al., 2022. City-level impact of extreme temperatures and mortality in Latin America. Nature medicine, 28 (8), 1700–1705. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01872-6.

- Lotfata, A. and Hohl, A., 2021. Spatial association of respiratory health with social and environmental factors: case study of Cook County, Illinois, USA. Cities & health, 6 (4), 791–803. doi:10.1080/23748834.2021.2011538.

- Lovasi, G.S., Diez-Roux, A.V., and Kolker, J., 2020. Urban public health: a research toolkit for practice and impact. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Luke, D.A. and Stamatakis, K.A., 2012. Systems science methods in public health: dynamics, networks, and agents. Annual review of public health, 33 (1), 357. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101222.

- McCulley, E.M., et al., 2022. Urban scaling of health outcomes: a scoping review. Journal of urban health, 99 (3), 409–426. doi:10.1007/s11524-021-00577-4.

- Morris, K.A., 2018. Measurement equivalence: a glossary for comparative population health research. Journal of epidemiology and community health, 72 (7), 559–563. doi:10.1136/jech-2017-209962.

- Noppert, G.A. and Clarke, P., 2020. Making the invisible visible: the current face of tuberculosis in Detroit, Michigan, USA. Cities & health, 6 (4), 684–692. doi:10.1080/23748834.2020.1769286.

- Pomeroy-Stevens, A., et al., 2021. Exploring urban health inequities: the example of non-communicable disease prevention in Indore, India. Cities & health, 6 (4), 726–737. doi:10.1080/23748834.2020.1848327.

- Quistberg, D.A., et al., 2019. Building a data platform for cross-country urban health studies: the SALURBAL study. Journal of urban health: bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 96 (2), 311–337. doi:10.1007/s11524-018-00326-0.

- UNDP Population Division. 2018. World urbanization prospects: the 2018 revision. United Nations Publications. Available from: https://population.un.org/wup/.