RESUMEN

La planificación transformadora reestructura radicalmente los usos del suelo urbano, los diseños y los paisajes urbanos para responder al cambio climático y mejorar la salud y la calidad de vida de la ciudadanía. Examinamos cómo la planificación transformadora puede perder de vista a cuestiones relacionadas con la equidad, apoyándonos en el ejemplo del plan transformador de Barcelona para implementar Supermanzanas (Superblocks in English, Superilles in Catalan). Argumentamos que las preguntas sobre la equidad distributiva y relacional, incluida la evaluación y priorización de necesidades impulsadas por la equidad interseccional; beneficios o cargas locales espacializados; objetivos de justicia de movilidad; la exclusión y la gentrificación verde, junto con la equidad procesal, deben ocupar un lugar destacado en la agenda de la planificación transformadora para lograr la justicia urbana verdadera. También pueden implicar trade-offs claves entre abordar las vulnerabilidades sociales y ambientales.

ABSTRACT

Transformative planning radically restructures urban land uses, designs, and streetscapes to respond to climate change and improve residents’ health and quality of life. We examine how transformative planning may overlook critical questions related to equity relying on the example from Barcelona’s transformative plan to implement Superblocks. We argue that questions about distributional and relational equity, including intersectional equity-driven needs assessment and prioritization; spatialized local benefits or burdens; mobility justice goals; exclusion and green gentrification, together with procedural equity, must be high on the agenda for transformative planning to achieve urban justice for all. They may also involve key trade-offs between addressing social and environmental vulnerabilities.

PALABRAS CLAVE:

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Cities around the world are looking for transformative planning strategies to radically rework urban land use and streetscapes in response to the climate crisis. Transformative strategies are ambitious, operate at the city scale, and target multiple issues including mobility, health, social justice and climate change adaptation (Zografos et al. Citation2020, Bulkeley Citation2021). They often entail major re-designs to street networks and the creation of new public spaces. Among these transformative initiatives, we find the 15-minute city project (Paris, Melbourne), the low traffic neighborhoods (London), or the Superblock projects (Barcelona, Vienna). All have created pedestrian-oriented streetscapes that aim to catalyze change that can reverberate throughout the city. These transformative strategies are attracting attention, especially in the aftermath of the pandemic in which tactical interventions have transformed public space and allowed us to re-imagine what cities could look like (Honey-Rosés et al. Citation2021, Glaser and Krizek Citation2021, Rojas-Rueda and Morales-Zamora Citation2021, Honey-Rosés Citation2022).

While transformative planning aims to reorganize power dynamics and decision-making, in practice these plans are contentious, entangled in top-down planning procedures, under the influence of entrenched interests, and often unable to create the inclusive and democratic spaces promised. Even the most celebrated examples of transformative urbanism still leave basic questions about equity unanswered. Here we outline the critical questions that need interrogation when assessing transformative urban planning. We use Barcelona’s Superblocks as our entry point. Many of these questions are not new but are worth highlighting because they remain overlooked and have been raised by analysts and critics of the Superblocks and related transformational interventions. We argue here that questions about distributional and relational equity in terms of benefits, access, exclusion, and green gentrification as well as procedural equity in terms of participation and community outreach need to be high on the agenda to ensure that transformative planning achieves urban and climate justice for everyone.

Barcelona’s Superblocks as an experiment in transformative planning

Barcelona Superblocks are a traffic management and urban design strategy that prioritizes pedestrians over vehicle traffic with the aim of improving environmental quality and livability for neighborhood units. Barcelona’s Superblock program has received international acclaim as a bold move to re-organize public space and mobility networks (O'Sullivan Citation2017). International headlines such as ‘Barcelona’s radical plan to take back streets from cars’ emphasize the ambitious scale of the initiative (Roberts Citation2019).

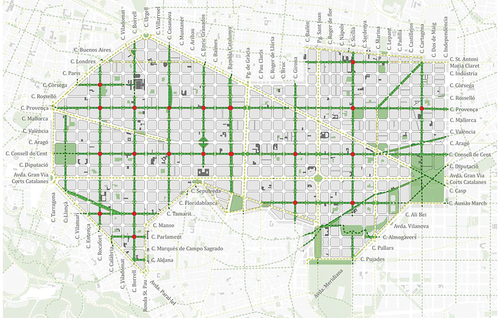

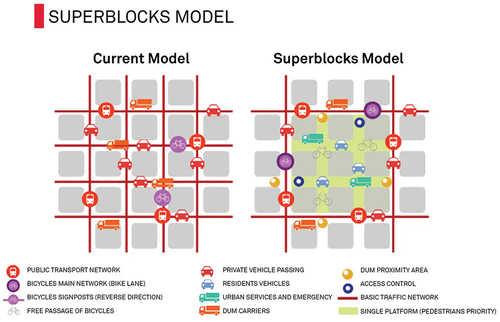

Barcelona’s archetype Superblock entails nine city blocks, in which traffic is diverted in and away from the center block, thereby transforming four vehicular intersections into four public plazas. The neighborhood is pedestrianized and through traffic is pushed to the surrounding arterial streets (Rueda Citation2019). By eliminating through traffic, the Superblock design aims to decrease noise and air pollution, convert car-centered street spaces into green and walkable streets, while strengthening public transit and cycling infrastructure ().

Figure 1. The original superblock model (implemented in Poblenou and Sant Antoni).

As laid out in the early 2010s, the Superblock program proposed a radically new way of organizing the city’s transportation network, that marked clear departure from the past (Honey-Rosés Citation2023). Transportation networks have a huge impact on the urban social fabric, acting both as a generator of inequalities and a catalyzer of existent spatial injustices. Increased barriers to car-travel within the city in the form of less dedicated space, fewer parking, and less direct routes may motivate drivers to choose alternative travel modes. The expected improvement in air quality and sustainability indicators comes from the shifts to active travel and reduced car use. The Superblock model also shares end goals with a broader 15-minute vision for Barcelona (Ferrer-Ortiz et al. Citation2022, Vich et al. Citation2022).

Prior to the implementation of the first pilot Superblock in Poblenou in 2016, the city began to brand pedestrianization initiatives in other neighborhoods as part of the Superblock program, creating confusion between the Superblock city model and other street calming projectsFootnote1. What is interesting about the Superblock archetype is that it is a scalable urban model that can be applied in any grid network, of which there are many around the world (Eggimann Citation2022). And given the capacity of transportation networks to lock-in in future urban development and behaviors, the transformation potential is quite large.

While Barcelona’s Superblocks are praised as an example of transformative urban change and bold response to climate impacts (Zografos et al. Citation2020), its implementation has come with controversy. In what follows, we use Barcelona’s Superblock experience to examine the equity dimensions of transformative planning and the associated controversies involved in implementing radical urban change. We outline core questions that should be considered when assessing the equity dimensions of transformative planning ().

Equity questions for transformative planning

Is transformative planning targeting the neighborhoods that need it the most?

The most obvious question asks if transformational urban change is targeting the neighborhoods most vulnerable to negative environmental conditions and in need of pedestrianization, greater access to public space, and overall improvement in environmental conditions.

In Barcelona, the original Superblock plan outlined a vision for 503 Superblocks throughout the city, creating equalizing and redistributive benefits in all districts (Zografos et al. Citation2020, Eggimann Citation2022). Equality was meant to supercede equity, that is to ensure that all residents could be living in proximity to a Superblock rather than a prioritization of some areas over others because of specific needs. In practice, the Superblock began with a pilot in the Poblenou neighborhood in 2016, followed by another in Sant Antoni in 2018. While both projects have received abundant attention, the Superblock model has not been scaled to its original ambition, demonstrating the financial, administrative, and practical difficulty in implementing such ambitious change.

The pilot Superblocks sites were chosen out of convenience, and to minimize interruptions to city traffic. Thus, social and environmental equity considerations were not part of the site selection process, as field research and interviews we conducted in 2017 (Zografos et al. Citation2020), just after the initial Superblock deployment in 2016, revealed. The intervention was not seen as a way to redress inequities, but rather as a marketable and flagship program that needed to be implemented on a site where it was most likely to be successful. As an innovative and risky urban transformation, success was defined by neighborhood and political acceptance, rather than measurable improvements in environmental quality. This led city planners to select the less densely populated Poblenou neighborhood as the location for the first Superblock followed by Sant Antoni. For the more recent Superblocks (e.g. Green Axes, Eixos Verds in Catalan) however, public space needs and contamination levels became greater selection criteria, although without a consideration of intersecting neighborhood social or housing vulnerability, as more recent interviews we conducted in 2022 confirmed: ‘We are not working on social aspects, this is not our domain. We don’t have any impact on the conditions of a neighborhood with low socio-economic status through our work on, mmh, public space. Our impact on these aspects is very relative. However, if they have some public space deficit, we can intervene, yes. Or if they are contaminated (municipal technician, 2023)’.

Looking specifically at baseline air and noise quality conditions, the two pilot sites of Poblenou and Sant Antoni presented contrasting realities. The Sant Antoni site had worse air and noise pollution levels while the Poblenou site was less populated and polluted. Evaluating those Superblocks in 2021, the Barcelona Public Health Agency reported that NO2 concentrations in Sant Antoni decreased by 25% at the central Superblock intersection (Agéncia de Salut Pública de Barcelona Citation2021). Furthermore, sound measurements at the Sant Antoni site showed that noise at night has decreased in some months and increased in others, but overall has remained at similar levels (Agéncia de Salut Pública de Barcelona Citation2021). Thus, the Sant Antoni Superblock seems to have made progress in addressing air pollution while noise levels remain unchanged. Much of this noise now originates in the new street life and commercial activities (e.g. restaurant outdoor dining) replacing car traffic.

In terms of access to green and public space, the new green areas of Sant Antoni have become a well-used asset, by providing new local green and public areas for Sant Antoni families and elderly residents, as well as immigrant families living in the nearby Raval. Although Sant Antoni is relatively close to the Montjuic hill, topography had restrained real access to this large green space for elderly groups and families with children. As for Poblenou, prior to the Superblock, residents already had access to the Parc del Centre and the waterfront, so the green gain is more limited.

If one considers intersectional social and racialized needs and vulnerabilities in Barcelona, the Superblocks are not located in priority neighborhoods with (a) high numbers of working class, immigrant and migrant residents, (b) little and difficult access to proximate green spaces, and (c) high air and noise pollution exposure. For example, the peripheral areas of Nou Barris and Sant Andreu and the area around El Clot remain excluded from the Superblocks, even though they have benefit from the greening of major urban arterials such as La Meridiana or the highways surrounding the city.

In short, social equity concerns have not played a role in the selection of initial Superblock sites. Without explicitly incorporating intersectional equity concerns in transformational projects, these projects risk amplifying existing inequities.

(2) Do transformational projects shift burdens to other sites and neighborhoods?

Transformational projects risk burden shifting between sites and neighborhoods. Are the streets, buildings, and public spaces directly within the Superblocks harnessing greater environmental and social benefits in comparison to those just outside their borders? While transformational projects aim to improve the entire city, there may be spatial inequities at some scales. The original Superblock plan envisioned traffic reduction through the majority of streets in the city grid, with some streets remaining as arterials. In addition to this structural inequity, the plan’s partial implementation, with only a few Superblocks being built, may also have pushed traffic flows to surrounding streets or specific areas.

Earlier on in the implementation stage, in 2019 10,300 vehicles were found to have transited through the Vidadomat street, a 20% increase before the traffic calming intervention in 2017. Sant Antoni residents also reported greater risk perception of traffic accidents in streets that surround the Superblock such as Viladomat, an arterial outside the Sant Antoni Superblock (Agéncia de Salut Pública de Barcelona Citation2021). However more recent health and traffic studies have shown that, while traffic and noise increased in some streets over the short term, traffic evaporation dynamics may now be taking hold at a neighborhood scale. When analyzing traffic intensity before and after the Superblock and other traffic calming strategies throughout all the Eixample, the most recent study from 2022 estimates that traffic levels on intervened streets have decreased by 15% while those in adjacent parallel streets have seen insignificant changes or only 0.7% increase. Streets in the wider vicinity have experienced an average 0.9% decrease in traffic (Nello-Deakin Citation2022).

It is thus worth noting that the traffic reduction achieved on intervened streets did not lead to a redistribution of traffic to adjacent streets, rather, some of the traffic seems to have disappeared, potentially as a result of drivers choosing other modes of transport or outer-neighborhood routes. These more mid-term dynamics suggest that once implementations are scaled, one could see major reductions in traffic volume. In short, transformational projects must examine impacts at the city scale with particular attention to rebound effects and burden shifting. However, it is still early to assess the full scope of possible rebound effects and burden shifting versus wider, mid-term gains due to the Superblocks intervention.

(3) Are transformational projects helping achieve mobility equity and justice?

Mobility justice refers to people’s safety, wellness, and positive experience while being and traveling on the streets and well as their ability to move joyfully and fearlessly (America Walks Citation2023). From a travel behavior standpoint, the Superblocks aim to trigger changes in ways that will reduce car use, lower emissions, and increase active transit. Negative impacts of motorized transport are usually unevenly distributed, with the health of socially vulnerable, working class, racialized and immigrant, communities disproportionately affected by transport-related externalities (Josey et al. Citation2023). One would thus expect that transformative interventions aimed at improving mobility be also directed towards redressing those impacts and benefit these same groups (Aldred et al. Citation2021).

Looking at travel behavior, we observe that Superblocks have increased accessibility levels and active travel infrastructure in already high accessible areas. The Sant Antoni Superblock is located in a highly walkable and accessible site, that in fact is within the 100th percentile for accessibility (Vich et al. Citation2022) and is inhabited by high and middle class groups with no specific mobility issues beyond a general ageing (Ferrer-Ortiz et al. Citation2022). In contrast, the mobility needs of essential, working-class workers who live disproportionately in peripheral areas and commute longer distances (Anguelovski et al. Citation2022) remain unmet or unaddressed by Barcelona’s Superblocks. The program has thus been unable to generate a city-wide change of conditions and address complex mobility equity needs in Barcelona’s historically marginalized neighborhoods. Here we see that while the Superblocks project goals are noble, the urban design changes will likely have limited impacts on travel behavior especially among socially vulnerable population groups.

In terms of social transport disadvantages, women and seniors are also among the most likely to suffer from car-oriented environments (Marquet and Miralles-Guasch Citation2014). The Superblocks in their current state of development have certainly brought some local improvements in that regard. The creation of new and valuable open spaces segregated from car traffic has also provided some much-needed safe socialization and resting public spaces. Among the most benefitted groups are indeed seniors, for whom high quality urban spaces are essential as a place to socialize and get out of home (Akinci et al. Citation2022), and women with children who are among the population groups with more complex travel strategies and the more frequent users of proximity trips and reliant on active transportation (Maciejewska and Miralles-Guasch Citation2020). In that regard, the Superblock in Sant Antoni is particularly well used and appreciated by elderly residents. Improving the infrastructure for active travel and public meetings will thus have a direct impact over quality of life of these groups, helping to bring balance in current mobility inequalities.

However, in other areas, immigrant, and/or even elderly people might not feel comfortable spending time in newly renovated public spaces and streets if they feel they do not socio-culturally belong in them, do not feel welcomed, or if they feel in ‘competition’ with active travel users. For example the elderly have reported a sense of isolation in the Poblenou Superblock (Agència de Salut Pública de Barcelona Citation2021), raising concerns about relational justice.

(4) Is transformational planning playing a role in green gentrification?

The gentrification potential of transformative planning has been well documented around the world (Curran and Hamilton Citation2017, Gould and Lewis Citation2017). Projects with the best of intentions are not immune to market dynamics and land speculation that may burden or displace local residents. Some of the equity concerns surrounding the Superblocks relate to whether they are building secluded islands of environmental privilege through associated gentrification and other exclusionary development dynamics. Green gentrification refers to how urban greening agendas contribute to demographic change and increased housing prices that displace working-class and racialized groups from recently greened areas. When considering spillover effects besides vehicle-traffic levels, quantitative and spatial research conducted in Barcelona has already shown accelerating city-wide green gentrification trends throughout the last two decades, especially due to parks and greenways (Anguelovski et al. Citation2022, Triguero-Mas et al. Citation2022). Barcelona’s urban greening and branding agendas have positioned the city as a global leader in climate-responsive agendas through the re-naturing of urban spaces and the elimination of car dominance in the city (Kotsila et al. Citation2021). This agenda makes Barcelona an attractive city for the arrival of so-called expat workers, international firms, and international real estate investments, thus accelerating gentrification (Cocola-Gant and Lopez-Gay Citation2020).

Residents surveyed in the Superblocks, especially school-age families surveyed in the vicinity of the new infrastructure as well as housing-rights civic groups (i.e. Observatori dels Barris de Poblenou; La Flor de Maig), report fear of displacement as a result of the urban greening agenda and relate this displacement to the attractiveness and the branding of the Superblock (Oscilowicz et al. Citation2020, Planas-Carbonell et al. Citation2022). While most residents and families value the environmental, climate, and social benefits of low-traffic streets and green spaces, they share experiences and perceptions of physical and socio-cultural displacement and are anxious about the future. They also regret that most new real estate developments built around the Superblocks, such as IT/design office buildings, luxury condos, and hotels are targeting high-income residents and digital nomads rather the district’s long-term residents. A member of a housing association in Poblenou (2021) shared: ‘there is no question that the area around Cristóbal de Moura is nicer than before, but the question is: why is it nicer, and most importantly, for whom?’ (Interview 2021). Cristóbal de Moura is a green, climate-resilient street redeveloped in the vicinity of the Poblenou Superilla, which has seen new high-end buildings pop up since the late 2010s.

The City of Barcelona is aware of these risks and is working to mitigate them through new social housing within the Superblocks and other measures meant to mitigate or prevent gentrification. In Poblenou, for example, the city has invested in the construction of 18 protected units at the intersection of Ciutat de Granada and Almogàvers. Overall, the city has invested in the construction of 2,300 units of such units throughout the entire Sant Martí district where Poblenou is located. The municipality also has a social housing rule in place, through which 30% of newly built units in Barcelona should be reserved for this type of housing. It is still unclear if these housing strategies will be enough to avoid the displacement of working and middle class residents living in the vicinity of the Superblocks, but the current municipal team is clearly working to prioritize housing justice in the Superblocks and beyond.

(5) Is transformational planning contributing to a different model of civic participation?

A final question relates to procedural equity. Here, the Superblocks must be examined in relation to whether and how residents have been involved in assessing needs and (co)designing and (co)using the space.

The location of the original Superblock in Poblenou, was selected based on the relative low number of people that lived there and the low number of vehicles potentially impacted by the traffic re-design. A first pilot project stage included a participatory process engaging with academics, design professionals and also local neighborhood associations. The process was led a centralized manner by the Agència d’Ecologia Urbana (Urban Ecology Agency) in collaboration with the Confederació de Tallers de Projectes d’Arquitectura (Confederation of Architecture Projects Workshops), that is not by the municipality itself but by expert groups. Those included the use of online tools such as maps and surveys to gather input and feedback (Guijarro Turégano Citation2022) and involved working groups made up of local residents, businesses, and community organizations, which were on paper responsible for developing specific aspects of the project. However, critics argue that these participation processes were minimal, not supporting the final street selection, purely information sharing-focused, and limited to what was required by law. They did not involve a true co-design process or any deliberative process. Overall some residents regret that the municipality blundered the implementation by changing the nine block site last minute, just weeks before the first pilot was deployed and by choosing streets with little traffic and affected residents (Zografos et al. Citation2020, Guijarro Turégano Citation2022). In contrast, the construction of the Sant Antoni Superblock involved a stronger and earlier communication process with groups of neighbors, civic associations, and families, and the final project was more well received. The Sant Antoni Superblock project also benefited from a timely renovation of the neighboring historic Sant Antoni public market, which greatly improved the quality of the public space and synergized well with the Superblock objectives.

In 2021 the City embarked on a new participatory process using its online public engagement platform Decidim (‘We decide’), to discuss the reformulation of the Superblock initiative. This process brings together civic groups and associations working together with city staff to collaboratively diagnose public space needs and organize charettes designed to harness residents’ proposals for specific interventions. As of early 2023, civic groups and agencies such as Home Help Service (Servei d’Ajuda a Dominici) are also working to help residents and associations better appropriate the Superblocks for themselves through the vision of ‘Superblocks of Care’, putting emphasis on the need to support social relations and care activities in and around the new public spaces built in the Superblocks. An evaluation of these participatory schemes is yet to be conducted. In the future, the Climate Assembly created in Fall 2022 may serve as a novel yet untested approach to engage with local reference groups around the future of the Superblocks.

(6) Is the reconceptualization of the original form and design of transformative projects addressing equity concerns?

In March 2021 the city announced that the Superblock program was pivoting away from the creation of neighborhood units within nine city blocks and instead focusing on the creation of Green Axes (Eixos Verds) (City of Barcelona 2021)Footnote2(). While not explicit, the city essentially abandoned the original nine Superblock archetype, but retained its commitment to the core values of pedestrianized spaces that inspired the Superblock idea in the first place, creating considerable confusion within the city, but also for international observers.

The new framing aspires to re-scale the original nine block archetype for the entire city, meaning that city planners aim to transform the entire Eixample district into a pedestrianized space. In this sense, they aspire for a Superblock Barcelona. Instead of pushing traffic onto arterials the goal is that traffic does not even enter the city.

The recent shift stems from a municipal vision to reach more residents and neighborhoods rather than creating what some municipal leaders have called ‘ghettos’ of privilege. The shape and extent of the Green Axes is meant to spread the benefits of greening throughout the city and avoid green gentrification. Yet the planned green axes are predominately in middle to higher-income neighborhoods of the Eixample district, the area with some of the most acute air pollution in Barcelona. The planned green streets, including Consell de Cent and Girona, will become highly desirable and attractive, while neighboring streets will remain untouched and potentially carry more vehicle traffic. Although the new L9 Metro line and local train line connectors are meant to create incentives for public transit and thus reduce car usage, those do not address risks of green exclusion.

Broader questions of mobility justice also remain in place. While the new bike and bus infrastructure throughout the greened Eixample increases active mobility options, they still do not target the mobility needs of many working class residents, most of them essential workers, who live in the peripheral neighborhoods or Barcelona or even outside the city, and whose longer-distance mobility needs exceed those of a District wide mobility. Last, fears of green and commercial gentrification are still being raised with the axes model. While the city bought buildings in 2022 through the Eixample to convert them into protected housing and is attempted to limit the opening of new leisure venues and businesses along the greened avenues, internal divisions within the local government are leaving the final magnitude and impact of these measures uncertain.

Conclusion

Several cities are proposing city-scale urban transformations that have the potential to address our climate crisis while meeting health and social needs. While we applaud the scale and scope of these efforts, key questions concerning who benefits from these projects remain overlooked. Using Barcelona’s Superblock an example of transformational urban change, we see that the boosterism and international acclaim overlooks this essential question.

Equity concerns have emerged from residents and critics, with some conflicting equity considerations between social and environmental vulnerabilities. These considerations are particularly important in a city like Barcelona where the worse air and noise contamination is not only affecting lower-income neighborhoods, that is traditional environmental justice communities, but also middle-class neighborhoods. Many questions remain open, complex to answer, requiring longitudinal spatial, quantitative, and qualitative data. Researchers are only starting to be able to grasp some of the impacts of the Superblocks on urban residents, public space use and access, climate abatement, and sustainable and equitable mobility.

Our analysis raises important questions for research and practice: Should short term inconveniences and negative noise and air pollution impacts in some areas be accepted for city-wide gain? How can we achieve genuine intersectional mobility and green space justice? Furthermore, there is a clear opportunity cost in investing political effort and capital in developing the Superblocks in their current locations. In a city with high accessibility levels such as Barcelona, the social gains derived from increasing accessibility and public space quality are small if these policies are not being implemented strategically in places that need it most.

Barcelona’s Superblock model has evolved over the last decade. A fragmented implementation of the original Superblock model might produce greater inequities. Switching to a system of green protected axes on the other hand might have greater equity benefits as those cover a larger swath of the city and potentially benefit wider and more varied population groups. However, the Green Axes approach risks watering down the synergies of spatially clustered neighborhood units found in the original Superblocks, especially with regard to travel behavior, transportation habit change, and new public space. What is also potentially lost with the axes approach is a truly transformational strategy, as well as the capacity to significantly innovate from a strategic planning perspective. The effect of the intervention ends up being similar to conventional street greening and pedestrianization, as many cities around the globe are already doing.

A natural and recommended next step for the city is to develop Superblocks in ways that can prioritize equity so that socially vulnerable residents can be sure to benefit from the transformative and tactical interventions, both from a mobility and public space perspective and with housing and real anti-estate speculation measures in place. While the original Superblock idea envisioned a sea of high-quality protected public spaces traversed by selected traffic arteries, the implementation struggles and controversy around the project might end up producing privileged green and protected axes traversing a sea of business-as-usual car-dominated grid. Refined and continued participatory models are also needed, through the voices of more invisible or marginalized groups are included in planning processes and where city planners are able to account for their socio-ecological needs rather than prioritize the vision of urban designers and architects.

We also recognize that the full positive (and negative) impacts of such strategic transformations are still to be fully assessed and account for mid-term and long-term impacts – impacts that political cycles and media tend to ignore by nature – and we call for a true monitoring of each intervention alone and all interventions together. Here, it is important to measure socio-ecological impacts at the local and city scale of different superblock models as well as their replicability. Health impact assessments as well as social equity impact assessments are underway with the support of the City of Barcelona and conducted by local research centers and agency (e.g. Barcelona Public Health Agency, ISGlobal, Institute for Environmental Sciences and Technology-Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona), which demonstrates a strong commitment to understanding the intersectional impacts and challenges the Superblock model.

Overall, when universal implementation of transformative urbanism is not possible, planners end up with difficult tradeoffs, between spatial equity and travel behavior change capacity and between environmental improvements and social justice. The Barcelona experience demonstrates that ensuring equity principles in transformative planning depends on our capacity to implement interventions at the city-scale, throughout the city grid, with special attention to underprivileged areas with different spatial and socio-economic characteristics. Deciding which trade-offs are most acceptable and just is thus maybe one of the key challenges for future strategic planning and climate justice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Isabelle Anguelovski

Isabelle Anguelovski, Jordi-Honey Rosés, and Oriol Marquet are urban planners and geographers at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and the Institute for Environmental Sciences and Technology. They research how to make cities healthier, green, proximate, and just and how climate responses can better address these goals.

Jordi Honey-Rosés

Isabelle Anguelovski, Jordi-Honey Rosés, and Oriol Marquet are urban planners and geographers at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and the Institute for Environmental Sciences and Technology. They research how to make cities healthier, green, proximate, and just and how climate responses can better address these goals.

Oriol Marquet

Isabelle Anguelovski, Jordi-Honey Rosés, and Oriol Marquet are urban planners and geographers at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and the Institute for Environmental Sciences and Technology. They research how to make cities healthier, green, proximate, and just and how climate responses can better address these goals.

Notes

1. Street calming and traffic management programs in Horta, Les Corts and Gràcia were developed by the Superblock program of the city, and labelled as such but did not follow the complete conceptual model envisioned. They entailed traffic re-direction but were developed in old city street patterns and not in a city grid. In this way, these early experiences share more resemblance to classical street calming projects that eliminated vehicle traffic in old city centers, which has been seen throughout Europe since the 1980s. For our purposes here, these initial neighborhood improvements did not follow the underlying city model that defines the Superblocks in Barcelona’s grid system and are not entirely comparable experiences.

References

- Agencia de Salut Pública de Barcelona, 2021. Salut als Carrers. Barcelona. https://www.aspb.cat/documents/salutalscarrers/

- Akinci, Z.S., et al., 2022. Urban vitality and seniors’ outdoor rest time in Barcelona. Journal of transport geography, 98, 103241. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2021.103241.

- Aldred, R., et al., 2021. Equity in new active travel infrastructure: a spatial analysis of London’s new low traffic neighbourhoods. Journal of Transport Geography, 96, 103194. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2021.103194.

- America Walks, 2023. Mobility justice. https://americawalks.org/resources/mobility-justice/

- Anguelovski, I., et al., 2022. Green gentrification in European and North American cities. Nature communications, 13 (1). doi:10.1038/s41467-022-31572-1.

- Bulkeley, H., 2021. Climate changed urban futures: environmental politics in the anthropocene city. Environmental politics, 30 (1–2), 266–284. doi:10.1080/09644016.2021.1880713.

- Cocola-Gant, A. and Lopez-Gay, A., 2020. Transnational gentrification, tourism and the formation of ‘foreign only’ enclaves in Barcelona. Urban Studies, 57 (15), 3025–3043. doi:10.1177/0042098020916111.

- Curran, W. and Hamilton, T., 2017. Just green enough: urban development and environmental gentrification. London and New York: Routledge.

- Eggimann, S., 2022. The potential of implementing superblocks for multifunctional street use in cities. Nature sustainability, 5 (5), 406–414. doi:10.1038/s41893-022-00855-2.

- Ferrer-Ortiz, C., et al., 2022. Barcelona under the 15-minute city lens: mapping the accessibility and proximity potential based on pedestrian travel times. Smart cities, 5 (1), 146–161. doi:10.3390/smartcities5010010.

- Glaser, M. and Krizek, K.J., 2021. Can street-focused emergency response measures trigger a transition to new transport systems? Exploring evidence and lessons from 55 US cities. Transport policy, 103, 146–155. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2021.01.015.

- Gould, K.A. and Lewis, T.L., 2017. Green gentrification: urban sustainability and the struggle for environmental justice. London and New York: Routledge.

- Guijarro Turégano, B., 2022. Repensar los cruces. La implementación del modelo Superilles: el caso de la Superilla del Poblenou de Barcelona (2016-2021). Doctoral Thesis. Universitat de Barcelona.

- Honey-Rosés, J., et al., 2021. The impact of COVID-19 on public space: an early review of the emerging questions–design, perceptions and inequities. Cities & Health, 5 (S1), S263–S279. doi:10.1080/23748834.2020.1780074.

- Honey-Rosés, J., 2022. Urban resilience in perspective: tracing the origins and evolution of urban green spaces in Barcelona. In: I. Ruiz-Mallén, H. March and M. Satorras, eds. Urban resilience to the climate emergency. Springer, 45–63.

- Honey-Rosés, J., 2023. Superilles: Recerca i experimentació. In: Superilles Barcelona. Ajuntament de Barcelona, 436–461.

- Josey, et al, 2023. Air pollution and mortality at the intersection of race and social class. New England journal of medicine, 388, 1396–1404. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa2300523.

- Kotsila, P., et al., 2021. Barcelona’s greening paradox as an emerging global city and tourism destination. In: I. Anguelovski and J.J. Connolly, eds. The green city and social injustice: 21 tales from North America and Europe. New York, London: Routledge, 22.

- Maciejewska, M. and Miralles-Guasch, C., 2020. Evidence of gendered modal split from Warsaw, Poland. Gender, Place & Culture, 27 (6), 809–830. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2019.1639631.

- Marquet, O. and Miralles-Guasch, C., 2014. Walking short distances. The socioeconomic drivers for the use of proximity in everyday mobility in Barcelona. Transportation research part a: policy and practice, 70, 210–222. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2014.10.007.

- Nello-Deakin, S., 2022. Exploring traffic evaporation: findings from tactical urbanism interventions in Barcelona. Case studies on transport policy, 10, 2430–2442.

- Oscilowicz, E., et al., 2020. Young families and children in gentrifying neighbourhoods: how gentrification reshapes use and perception of green play spaces. Local environment, 25 (10), 765–786. doi:10.1080/13549839.2020.1835849.

- O'Sullivan, F., 2017. Barcelona's Car-Taming 'Superblocks' Meet Resistance. Bloomberg City Lab. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-01-20/barcelona-s-superblocks-expand-but-face-protests

- Planas-Carbonell, A., et al., 2022. From greening the climate-adaptive city to green climate gentrification? Short-lived benefits and mixed social effects in Boston, Philadelphia, Amsterdam and Barcelona. Urban climate. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4053652.

- Roberts, D., 2019. Barcelona’s radical plan to take back streets from cars. Vox. https://www.vox.com/energy-and-environment/2019/4/9/18300797/barcelona-spain-superblocks-urban-plan

- Rojas-Rueda, D. and Morales-Zamora, E., 2021. Built environment, transport, and COVID-19: a review. Current environmental health reports, 8 (2), 138–145. doi:10.1007/s40572-021-00307-7.

- Rueda, S., 2019. Superblocks for the design of new cities and renovation of existing ones: barcelona’s case. In: M. Nieuwenhuijsen and H. Khreis, eds. Integrating human health into urban and transport planning. Cham: Springer, 135–153.

- Triguero-Mas, M., et al., 2022. Exploring green gentrification in 28 global North cities: the role of urban parks and other types of greenspaces. Environmental research letters, 17 (10), 104035. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac9325.

- Vich, G., Gómez-Varo, I., and Marquet, O., 2022. Measuring the 15-minute city in Barcelona. A geospatial three-method comparison. Resilient and sustainable cities: research, policy and practice, 39, 39–60.

- Zografos, C., et al., 2020. The everyday politics of urban transformational adaptation: struggles for authority and the Barcelona superblock project. Cities, 99, 102613. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2020.102613.