ABSTRACT

We describe neighbourhood community ‘walkabouts’ using photography as a pragmatic, low-cost methodology for engaging with disadvantaged and marginalised communities, to assist local authorities providing and consulting about city services. Using a health lens frame on neighbourhoods as providing or restricting opportunities for play, interaction, physical activity and nutrition for children and families, we conducted two walkabouts using photography in an ethnically diverse European city. The meeting point for Somali and other ethnically diverse community members, practitioners, elected representatives and academics in this action research was a shared wish to improve the neighbourhood public realm for child health and development, family wellbeing and confident childrearing. The methodology brought opportunities to improve local physical environments for communities, to develop relationships with neighbours and authorities, and to influence statutory planning, decision-making and urban investment. Neighbourhood walkabouts with photography can serve as an accessible platform for communication and advocacy, and help decision-makers effectively hear the voices of disadvantaged and marginalised communities.

Introduction

In this paper, we have written to describe and document the methodology we used in an urban health intervention. It was developed to help join up the lived experiences of local disadvantaged and marginalised families with municipal decision-making to improve their physical environments. We used a combination of walkabouts, photography, communication and deliberation.

Targeting resources to improve children’s educational, health and social outcomes depends on effective public involvement and consultation. Young children need opportunities for play, physical activity, social interaction and healthy nutrition and to develop and socialise confidently, and grow up healthy (Hertzman and Boyce Citation2010, Moore Citation2017, Black et al. Citation2017). Disadvantage, poverty and stress disproportionately affect minority ethnic groups, disadvantaged migrants and refugees (Pascoe and Smart Richman Citation2009, Warner and Brown Citation2011, Fazel et al. Citation2012, Mccabe et al. Citation2013, Almeida et al. Citation2013). Migrant children are more likely to live in deprived areas and be socially excluded (Buchanan Citation2004, Sampson and Sharkey Citation2008, Davies et al. Citation2009, Galster Citation2012, Lim et al. Citation2020); social isolation increases vulnerability and vigilance (Hawkley and Cacioppo Citation2010, Talbot Citation2013). Migrants from cultures where ‘it takes a village to raise a child’ may experience challenges bringing up children in the ‘Global North’, without the supportive social networks they have been used to (Allport et al. Citation2019).

There is evidence that, even in disadvantaged communities, local amenities that are safe to access on foot and good to play in can promote healthy child development (Nordström Citation2010, Christian et al. Citation2017). The UNICEF initiative, Child Friendly Cities, expands the traditional rural focus of this UN agency into urban situations, supporting planners to look at cities and towns through the eyes of a child to promote the planning, design and implementation of child-responsive environments (UNICEF Citation2018). With urban planners increasingly aware of the environment’s impact on health and well-being, connecting children’s rights and urban planning principles offers a good starting point for policy-makers (Aerts Citation2018). Understanding the potential of ‘place’ (Agnew Citation2011) to impact health and health inequalities has become a priority for local authorities, public health practitioners and researchers. We have adapted methodologies of Walkabout and Photovoice to support asset-based and change-oriented involvement of disadvantaged migrant communities in improving accessibility and equity of their local services and neighbourhood environments.

Although this paper has at its heart a neighbourhood case study, we believe it contributes to the growing interest in methodologies examining how to listen to the lived experience of marginalized urban communities (Flyvbjerg Citation2006). Traditionally, consultations about the use of the urban realm are used when a new plan, proposal or investment is envisaged. Local authorities use a variety of methods, e.g. meetings, online comments, exhibitions, often within an envelope of statutory time tables. Once collected, it can be far from transparent as to how the responses are analysed (Eriksson et al. Citation2022). In the UK, reducing inequalities is now a duty for service delivery and commissioning organisations (Parliament Citation2012, NHS Citation2019)Footnote1,Footnote2, with increasing attention to services’ responsibility to reverse processes that exclude and marginalise (Downe et al. Citation2009, O’Donnell et al. Citation2016, Luchenski et al. Citation2018). We hope that the methodology described in this paper is a useful addition to the repertoire of approaches to facilitate dialogue between local communities and decision-makers, and to improve local environments in ways that reduce inequalities.

Importance of neighbourhood environment for child development and health

Playful environments can enhance children’s levels of physical activity and fitness (Fjørtoft Citation2001, Sallis and Glanz Citation2006), and enhance their mental health, independence, confidence, social interaction and socialisation (Crespo et al. Citation2001, Bixler et al. Citation2002, Cole-Hamilton et al. Citation2002, Undiyaundeye Citation2014). But how do we define ‘playful’ and healthy local environments for child development? In the West, discourses surrounding children’s play have tended to ignore the different sociocultural contexts that shape children’s play around the world, with community values, beliefs and cultural routines shaping very different ways in which children play and learn in their everyday lives, with important exceptions (O’Brien et al. Citation2000), highlighting the importance of studying the diverse ways children inhabit their cities, to assist in the development of social policies to enhance participation for all children. Studies from many Western countries have documented a dramatic decline in the time and freedom contemporary children are given to independently explore their neighbourhoods (Hofferth and Sandberg Citation2001, Shaw et al. Citation2013, Kyttä et al. Citation2015, Woolley and Griffin Citation2015). Structural environmental factors exert their influence on children’s development by determining the distribution of resources or risks that may alter development, with some of the strongest evidence for these effects occurring at neighbourhood level (Chetty et al. Citation2016, Minh et al. Citation2017, Miller et al. Citation2019, Acevedo-Garcia et al. Citation2020, Wang et al. Citation2020). Therefore, how neighbourhoods can support or hinder children’s development and wellbeing, as well as parents’ collective ‘efficacy’ (Sampson et al. Citation1999, Collins et al. Citation2017, Bell et al. Citation2020) is an important topic this study seeks to address in relation to migrant families.

For the purposes of this study, in our use of the term ‘neighbourhood’, we take a broad approach as found in the review by Minh et al. (Citation2017). Different disciplines may use the term to encompass one, two or several of the institutional, cultural, environmental, geographic and social-interactive contexts of a local place. We acknowledge all these as important factors of neighbourhood, whilst focusing on the physical (environmental and geographic) as our main entry point for discussions with local residents and as a route for potential interventions.

Use of walkabout and photography to understand environments, engage local adults and children in neighbourhood planning and design, and enable change

To examine the role of place in health and development, we need to understand how people perceive and experience their local environment, including the meaning or significance they ascribe to it. Specifically, we need to understand the local context that shapes their interactions with their neighbourhood environment. Participatory action research methods, such as walk-along interviews and Photovoice have been widely used to that purpose (Carpiano Citation2009). Furthermore, participatory methods are particularly suited to populations whose experiences are often under-represented in research, such as refugees, migrants and other disadvantaged groups, with the result that their experiences become marginalised in urban policy (de Graaf et al. Citation2015).

The walk-along interview involves a researcher accompanying and interviewing respondents on a walk in their neighbourhood or local area. The routes are usually chosen by respondents but the researcher could also pre-specify routes to solicit respondents’ views on a particular area. The interview format also varies from open to structured questions. Compared to sit-down interviews, the researcher is able to capture respondents’ interpretation and experiences of their environment while interacting with it in real-time (Kusenbach Citation2003, Carpiano Citation2009). It has been shown to generate more place-specific data than sit-down interviews (Evans and Jones Citation2011) and is a flexible method that can be used alone or in-conjunction with other methods. It could be tailored to include a group of residents rather than an individual, and is known as a walkabout.

Observing whilst walking is an established activity leading to insights to qualitative urban research, helping generate questions for urban living informed by observation of the use of space in real time that might not be easy to capture through other methods. The walking survey, map in hand, with observations and note taking, has been at the foundation of collecting data with a view to improving the design of a place. Traditionally, this activity has been a backbone of urban design research practice and lacks a robust theoretical literature (Pierce and Lawhon Citation2015). Recently, walking interviews have been receiving critical attention as a research method (Jones et al. Citation2008, Finlay and Bowman Citation2017). The ‘on site’ methodology employed in this study blends the participant research who sets the methodological frameworks and helps direct the research gaze, with the engaged community who, immersed in their local environment, are encouraged to notice and comment on elements that address the research foci.

Photography has been used in a wide range of community-based, participatory and collaborative approaches to permit people to identify, represent and voice what is of importance to them, and support engagement between disadvantaged or marginalised populations and research or decision-making processes (Wang and Burris Citation1997, Gubrium and Harper Citation2016). It has been used flexibly with different population groups to explore a range of public health issues, including the relationship between place, children, health, play and development (Dennis et al. Citation2009, Nykiforuk et al. Citation2011, Bird et al. Citation2014, Harwood and Collier Citation2019, Gaidhane et al. Citation2020)

We view children as active agents both in their neighbourhood environment and their perceptions of it (Kyttä Citation2004). Children’s perspectives on destinations they visit provide greater understanding of the geographies of home and school and neighbourhood within the context of the adult-dominated, regulated and restricted, auto-centric city (Kyttä et al. Citation2012, Bondi Citation2016, Egli et al. Citation2020). Attempts to centre the experience of children in ‘child-friendly planning & design’ have taken similar approaches (Karsten and van Vliet Citation2006a, Citation2006b, Wridt Citation2010, Carroll et al. Citation2015, Krishnamurthy Citation2019, Ataol et al. Citation2019). Sarti et al. (Citation2018) appreciate ‘the walking tour’s identification of the “small details” which reflect and promote positive experiences of place’ and suggest that equally small changes to the resourcing and physical maintenance of neighbourhoods at a local level might have an exponentially larger impact upon diverse perceptions of personal and community well-being. Teixeira and Gardner (Citation2017) used a similar but more individualist and substantially more intensive approach, with GPS mapping, and young people choosing the route. There would seem to be potential also to link with other interactive and/or visual approaches or methodologiesfor example, film-making (Golden Citation2020).

Context for this work – Somali community in Bristol; local planning, evaluation and consultation process

Somali people represent one of the largest diasporas in the world, estimated at over 1.2 million (Hammond et al. Citation2011). Bristol has the fourth largest Somali community in the UK; at least 5% of Bristol children are now Somali (Mills Citation2014). Poor outcomes for Somali children and youth are an intense topic of discussion and concern locally, nationally and internationally for the Somali diaspora. Many community members share the view that the pre-school years are a critical period for early intervention. As yet largely unexplored is the relevance of ‘place’ in this process. There are many differences between the physical, cultural and psychological environments of rural Somalia and urban UK, which may have wide-ranging implications for young children’s experience of play and interaction, and their subsequent development (Allport et al. Citation2019).

The local area had been subject to a long programme of consultation, investment and change, due to significant indicators of deprivation, during a 10 year nationally funded programme (the £50 m ‘New Deal’ Community at Heart programme 2000–2010). There has been broad conjecture and review of the outcomes e.g. (Cork Citation2020) but we could not find post-occupancy work with residents with regard to their everyday experience of the public realm from a perspective of health and development.

We therefore sought to bring together the experiences of local people, centred around Somali community members, with those of key decision-makers, to facilitate mutual understanding and advocate for environmental improvements to support health, wellbeing, and child development. We therefore took an approach of ‘health lens’ walkabout with photography – to share different perspectives, to articulate needs and opportunities for change visually as well as verbally, and to join in the process of planning and provision of the urban neighbourhood environment in an innovative way.

Methodology

Approach, aims and objectives

The intended focus of our methodology was to involve and support some of Bristol’s refugee and disadvantaged migrant communities in understanding and advocacy about their local neighbourhood environment. The public health focus was to address pre-school and school children’s opportunities to move, play, interact and eat healthily. We took an asset-based approach to this process, with a focus on the local community as a common good, viewing participants as co-producers who could, through our research, identify opportunities and channel strengths (Foot and Hopkins Citation2010, Brooks and Kendall Citation2013). This approach was informed by action research methodologies, looking to develop an approach that would support effective engagement with Bristol City Council officers to enact environmental and public health improvements in the locality.

We therefore adapted a ‘Health Lens Walkabout’ methodology. This had already been developed and piloted by the public health and planning team in Bristol through Walkabouts in five communities facing health disadvantages within their local urban environment (Hewitt Citation2012). These had a broad public realm/health risk focus, lacking the more specific focus of the work described here. The innovations this time were as follows: the inclusion of photography during the walkabout to demonstrate visually what is of importance to participants; the focus on opportunities for play and interaction, and factors that might support or inhibit development, health and wellbeing, for families with young children; and more emphasis on bringing together the right combination of stakeholders for discussion and a photoexhibition launch to promote and enable environmental change.

This approach has two main differences from traditional consultation. First, it was more akin to a post-occupancy evaluation. Although post-occupancy evaluation is commonly used in the building scale, there are also examples at a neighbourhood scale (Boarin et al. Citation2018). Secondly, this approach ensures the community can see and understand the connections between their inputs, how these were handled, and the responses and results at a political and practical level.

The walkabouts

We held two Walkabouts supported through photographic documentary, in highly culturally diverse areas of Bristol, in July 2018 and April 2019. Our overarching stance was within a multi-stakeholder participatory action research paradigm (Kindon et al. Citation2008). The stakeholder group was formed around an established partnership, the Bristol Health Partners Health Integration Team ’Supporting Healthy Inclusive Neighbourhood Environments’, a strategic collaboration of built environment and public health practitioners and academics, and aligned with the local WHO Collaborating Centre for Healthy Urban Environments. This helped to signpost key partnerships and stakeholders to work with. The desired outcome was to help make the voice of the lived experience of parenting heard by those who had agency to improve the situation (see ‘The Hawkesbury Spiral in (Bawden Citation2021).

Participants

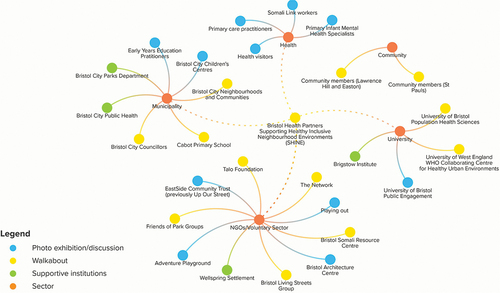

Our stakeholder participants included families (local parents and children from Somali and other ethnically diverse local communities), statutory and voluntary-sector staff (practitioners, commissioners, planners, policy makers and wider stakeholders working in Early Years child development and wellbeing, and/or for improving the local built environment), and researchers. We identified participants through a combination of convenience sampling (for local community members – parents and children), and purposive sampling (for other participants aiming to represent a range of stakeholder groups), with those invited able to signpost to additional relevant stakeholders (a ‘snowball’ approach). Community members, primarily parents and carers of pre-school and primary-school-aged children, embedded and living in each study area, were invited by local community organisations. We drew on pre-existing networks with local communities, as well as statutory and voluntary sector practitioners and policy-makers, to enable both strong attendance and rich dialogue. We adopted a dynamic stance to stakeholder involvement, with participants from within the local neighbourhood as well as wider stakeholders able to come in and out at different stages of the project, according to their own interest, their time-availability and agency to contribute. Between the two walkabout events, and the photoexhibition and discussion events that followed them, approximately 100 people participated in this process (see ).

The Health Lens in application

These walkabouts, lasting three hours in total (for introduction, orientation, walk and post walk discussion) used a ‘Health Lens Walkabout’ approach. The Health Map (Barton and Grant Citation2006) was used as an essential framing device before each walk. The purpose was to sensitise participants to the role that components in their everyday physical built, natural and social environment could play in hindering and/or supporting the health outcomes of that were the focus of this study. In this case, our introduction aimed to sensitise participants in their examination and communication of their neighbourhood as providing or restricting opportunities for physical activity, play, interaction and nutrition for pre-school children and their families.Footnote3 This aspect of the methodology was developed by Grant, building on his previous work using healthy neighbourhood community walkabouts in Bristol (Hewitt Citation2012).

Participants gathered for a 30-min introduction to the format of the walkabout. Then, we invited them to form small groups for 90-min walkabouts, looking for each group to include local people, interested stakeholders (from voluntary and statutory backgrounds), and researchers. Each small group had joint leadership (see Appendix: guide for facilitators) by a community member and either an interested stakeholder or researcher, facilitating (bilingual/interpreted) discussion about environmental features, guided by Healthy Neighbourhood Checklist categories (see ).

Table 1. Healthy neighbourhoods checklist categories.

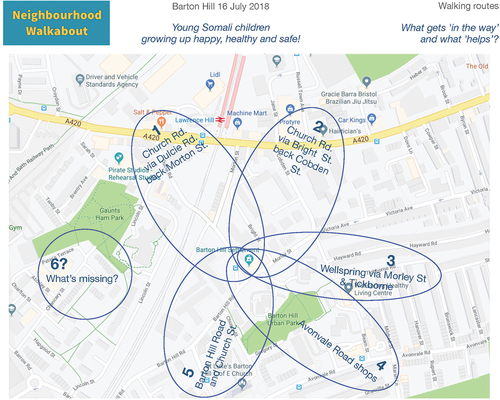

Pre-planned routes (see ) had been prepared in advance by the research team to allow exploration of different aspects of the local environment (e.g. environs of housing blocks, shops, streets and parks and some regular daily routes), with flexibility to adapt these route to take in ad hoc points of interest to participants as the walks were in progress.

In one of these events, we chose to hold it during school holidays to include school-aged children. Those children who took part were able to make comments and take photographs from their own perspectives, and were also invited to contribute on behalf of their pre-school siblings and friends.

One of the events was focused on a single (Somali) cultural community’s experience of a local neighbourhood (Barton Hill and the surrounding area), working together with Bristol Somali Resource Centre and the Barton Hill Activity Club; the other took a whole-neighbourhood perspective, linked to a local primary school (Cabot Primary in St Paul’s), while also working in partnership with a local Somali community organisation (TALO Somali Women’s Advocacy and Empowerment Group).

Documentation and analysis

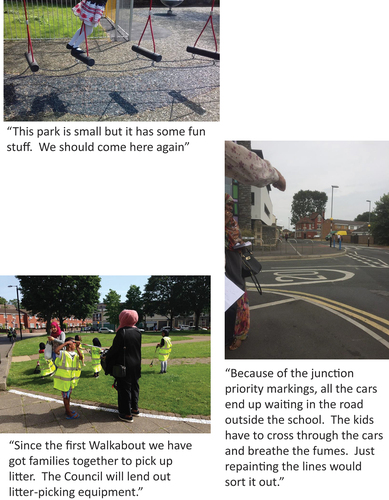

Participants and leaders were encouraged to take photographs during the walkabout, using smartphones or tablets, of scenes/objects of environmental features they considered worthy of later comment and review (see ). Following the sub-group walks, all groups returned to a central meeting point to share the experiences and learning and consider next steps. The groups then reconvened in the meeting room for a 60 min (interpreted) plenary discussion, facilitated by the project team, to explore the groups’ findings, proposed actions, and thoughts about stakeholders who would need to be engaged with in further dialogue and to effect any changes to local environments, which may be sought.

Participants’ photographs from the Walkabout were uploaded and viewed during this meeting to prompt discussion. Discussion was structured to capture what was ‘good’, i.e. worked well in the local environments and supported health; what was ‘bad’, i.e. what detracted from health or healthier lifestyles; and which places they had visited, and which photographs that had been taken, demonstrated opportunities for improvements to the local environment. The analysis was therefore primarily by the participants – drawing on their previous sensitising to the topics in focus from the introductory session presenting the Health Lens approach, and from the discussion during the walkabout process, with facilitators drawing on conceptual models of asset-based community development (Mathie and Cunningham Citation2003, Morgan and Ziglio Citation2007), environmental barriers and facilitators to participation (Schneidert et al. Citation2003), and participatory community research processes (Minkler and Wallerstein Citation2011).

The photographs were subsequently curated into an exhibition in collaboration between participants and facilitators, with an opening event for local community members presenting the exhibition alongside the findings of the walkabout, and the action plan. For the first Walkabout, we had funding for an artist to help curate the photographs taken into an exhibition, through discussion on the day, and with key collaborators in preparation for the exhibition. For the second, a meeting of the organising team (Somali parent group convenor, school Parent-Teacher Association chair, and paediatrician/researcher) identified key themes and selected photos that helped present them.

Photos were chosen for exhibition to help advocate and have an impact with those viewing them, with an audience of local people and at the same time those who had decision-making potential to allocate resources and effect change. Captions were generated via group discussion (and curation), which may or may not represent words from specific individual participants.

Ethical considerations and reflexivity

This paper describes public involvement processes conducted in Bristol, UK, in July 2018 and April 2019, and describes the evaluation of anonymous data collected by the organising team as part of the involvement process. As such, it was not considered to be research using the NHS HRA decision tool (Hra Citation2020) and following discussions with local collaborators and ethical committee leads, ethical committee approval and individual consent for participation and photography was not sought. However, the walkabouts and evaluation were conducted in accordance with accepted ethical standards and recognised professional codes of conduct, approaching consent as a process, with participants able to withdraw from participation at any point. No individual or personal data was sought from individual participants, and individual comments have not been attributed. We informed participants at the event that photographs would be displayed at photoexhibitions and used for further advocacy process including publication. We emphasised that they could contact any of the group convening these events, at any stage, if they did not want their photographs to be shared. The photographs included here have already been displayed in a public exhibition. Community members and leaders of community organisations were present at all stages of the process, ensuring that the issues and images identified for discussion were relevant and important, and unlikely to be considered intrusive, disclosing, or showing people in a poor light (Wang & Redwood-Jones Citation2001). This activity took place within an ongoing relationship between researchers and community organisations seeking to co-produce research and social/environmental change, that aims to be open to feedback and the need to reframe or redirect attention, focus and actionFootnote4, with ongoing attention to reflexivity (Finlay Citation2002, Malherbe et al. Citation2017).

Findings

A wide range of stakeholders attended these Walkabouts, offering perspectives as local children, parents, city staff, health and early years education professionals, academics, and voluntary-sector staff and volunteers.

Participants identified different aspects of the environments they observed and discussed together. We have thematically summarised these as helpful/positive, unhelpful/negative (lacking opportunities, unwelcoming, dirty, or unsafe), and those offering opportunities for improvement, all in terms of opportunities for play and interaction (see and ). Photos taken reflected these discussions – examples have been included with illustrative quotes (see and ).

Figure 4. Examples of environments considered helpful/positive, in terms of opportunities for play and interaction.

Figure 5. Examples of environments considered unhelpful/negative, in terms of opportunities for play and interaction.

Figure 6. Examples of environments offering opportunities for improvement, in terms of opportunities for play and interaction.

Table 2. What supports local health – helpful/positive environmental observations in terms of opportunities for play and interaction.

Table 3. What detracts from local health – unhelpful/negative environmental observations in terms of opportunities for play and interaction.

Table 4. What are the opportunities for improvement?

Conversations along the way shared knowledge (e.g. about the availability of litter-picking equipment; of regular meetings and events; of useful points of contact and statutory processes); built relationships within and between communities and those with different responsibilities; and generated energy for next steps (meetings, grant applications, photoexhibitions etc).

Discussion at community meetings and photoexhibition openings sought to identify ‘quick wins’ of changes to routine activities and work schedules, empower local people to self-organise, consider aspects of change where the voice of disadvantaged communities might need taking to authorities, and to identify more complex issues – interconnected, structural or financial – that would need sustained attention.

Evaluation and impact

Evaluation came from participants’ feedback throughout, from co-applicants’ and collaborators’ notes, from comments on uploaded photographs online and at the exhibition, and from subsequent engagement with Bristol City Council officers, other stakeholders on environmental and public health improvements, and academics.

Community members – adults and children alike, clearly enjoyed the process, and the opportunity to contribute their eyes and their voice to thinking about their local communities. Partner organisations have fed back that involvement in the process helped compare and contrast facilities available in neighbouring parts of Bristol, which helped them focus on local environmental change that might be both desirable and possible, and helped the concerns of those organisations to be part of continuing conversations about change, which has contributed both to constructive wider dialogue between the City structures and community members. There was also increased awareness amongst wider stakeholders of both the issues and the importance of drawing on local community assets for solutions.

The most prominent impact has been that both Walkabouts have influenced the allocation of resources through successful local applications for ‘Community Interest Levy’ (CIL) funding. As an outcome of the first Walkabout, we were able to collaborate with a range of stakeholders in a proposal for CIL funding for improvements to local parks in Lawrence Hill and Easton Wards, designed to improve children’s opportunities and outcomes, family wellbeing and community connectedness. Recently renovated parks may have higher visitation rates and overall greater levels of physical activity by children than unrenovated parks (Cohen et al. Citation2015).

The identification of this funding prompted a group of interested local residents getting together to discuss priorities for support with local families’ early child development. The clarity of thinking from the Walkabout helped to define some key principles and provided decision-makers with an evidence-base of local, but seldom heard, voices (see ). The funding proposal received strong support from wider community members and has successfully been awarded £600,000 to refurbish and improve the play facilities in two parks.

Box 1: “Our children are our future.” Text from: Improving young children’s opportunities for play and social interaction in local parks – Bristol City Council Community Infrastructure Levy Outline project submission March 2019.

A further Community Infrastructure Levy bid followed our second Walkabout, in St Paul’s, Bristol, where £80,000 was awarded to a partnership between Bristol’s Architecture Centre, St Paul’s Adventure Playground, St Paul’s Learning Centre, and the community groups including TALO Somali Women’s Advocacy and Empowerment Group. This aims to connect green spaces, streets, cultures and communities, ‘activating’ three valued community buildings, reconnecting them to their surrounding green spaces.Footnote5 The shared dialogue and photographs helped local groups to become part of the conversation with Councillors that developed this partnership and award.

The success of these processes has contributed to willingness for further engagement on the issues, including public meetings to discuss social networks and social change, and with children and young people currently engaged in workshops to develop as advocates and ambassadors for local environmental change.

Discussion

We report a methodology we have used of neighbourhood community ‘Walkabouts’ using photography – as a low cost, pragmatic, inclusive, asset- and solution-focused approach to co-production, which simultaneously investigates and supports change. The approach we describe would appear to offer academics, statutory and voluntary organisations, and disadvantaged communities an accessible way to develop shared understanding. It can be used to increase attention to marginalised experiences, and facilitate interaction/engagement between community and policy/decision makers about neighbourhood environments.

Ingredients for success

Reviewing the potential for aspects of this methodology to be transferable and inform future practice, we identified specific resources that we felt contributed to successful outcomes, consistent with key principles recommended for councils working in partnership to increase civic participation (Local_Government_Association Citation2021)

The social infrastructure afforded by Somali community members and groups

Established partnership/working relationship between researchers, community organisations and advocates, and local city council officers

The team of researchers and local advocates, with the right skill mix, available to give time to the project

The university’s commitment to and funding for public engagement in research

The resource available locally, in this case the CIL finance, with the potential for redirection towards this community

The continuing engagement and leadership of the principal investigator, coming from a dual perspective of community child health practitioner representing a specific local community, and engaged academic.

Including children, also central to our approach, made the process more enjoyable as well as relevant. Parents needed to know that the event would be enjoyable for their children as well as themselves, which was easier if they already knew other families that would be attending. Networking in advance, and building on established groups, contributed to this.

Food has been very important for bringing people together – at the end of each Walkabout, and for the Photoexhibition launch & discussion events. Our sense is that this (with academic funding) has added substantially to the enthusiasm of people joining in, especially at the Photoexhibition openings/discussions.

Strengths and limitations

We believe this methodology has many strengths. The process simultaneously investigates and supports change, working inclusively through participative, communal, narrative and visual practice; constructed so that community participants feel empowered to reflect and contribute. The walkabout, exhibition and associated stakeholder and public meetings serve as a unique way to engage the wider public and policy-makers and generate discussions for action that can be taken to create a positive built environment for child development and health. We experienced the collaborative, stepwise research process helping to build momentum and create impact, as community members and wider stakeholders iteratively developed a sense of the relevance and importance of the emerging findings. Choosing photographs together for the photoexhibitions and discussions, to portray significant themes, especially about places that offered opportunities for improvements to the local environment, added powerful impact to the developing community advocacy voice. The whole was experienced as a community-building process, at a local neighbourhood level, as well as between communities and local authority staff, and at the same time contributing to strengthening alliances between the varied organisations that look to support change e.g. councillors, public health, voluntary sector and academics e.g. local NGOs such as Playing Out (Ferguson Citation2019).

Its innovative contribution includes considering opportunities for play and interaction as a key public health resource to support child development as well as child and family wellbeing, involving children, working with refugees and disadvantaged migrants, and across language and culture, and combining walkabout with photography in an engaging, joining-up way, all at relatively low cost. Our approach keeps a ‘clear line of sight’ for the community between their inputs, how these were handled, and the responses and results at a political and practical level. This places the current residents and their concerns at the centre of the process. Moreover, as a community at risk of inequity, due to disadvantage, and marginalisation as migrants, it provides them with a higher degree of agency and control compared to the more familiar consultation methods used in urban planning.

Limitations of this methodology include the short period of working, therefore lacking a more lengthy, broad-based community engagement, with the possibility of people and/or groups not having felt included, and the potential for any approach, however participatory and equality-focused, to render some voices more prominent and others more marginalised (Lomax Citation2012). Though we took a collaborative, participatory approach, we recognise that the community should ideally have had more involvement in setting the aims and focus of the event, including planning of walking routes and development of discussion topics and questions. Photographs were primarily taken by adults and school-age children – although our focus was on opportunities for their younger siblings and friends. Different visual/creative methods would be more suitable to supporting the direct participation of children of pre-school age.

Our methodology involved fairly small amounts of professional time & resource, it is difficult to assess whether it was more time consuming than some forms of ‘conventional’ public consultations (e.g exhibition events, postal or online surveys). Arguably, it required a more inquisitive, scholarly and reflective input than would be usual in urban consultation, partly due to the specific nature of the inquiry, and partly to guide the many iterative steps taken part of this methodology. Although more conventional consultations may potentially have uncovered similar issues, the process we describe offered a very effective mechanism for engaging community members who would not usually have the capacity, ability or sense of empowerment to participate meaningfully in a more traditional consultation. The final outcome of these processes is likely to depend on a degree of longer-term involvement, as change processes initiated as a result of the findings are unlikely to proceed smoothly without continuing commitment of energy and networking. Community members can experience frustration with the length of time waiting to see change arriving, with the consequent need for managing expectations. To help address this, the research group has maintained a mutually supportive relationship with local community organisations aiming to help the community achieve longer-term outcomes.

‘Next steps’

Within a body of change-oriented neighbourhood and urban geographic research and practice (e.g. Mecking Citation2018, Monaghan Citation2019, Wyndham-West et al. Citation2022), we believe that walkabouts with photography and photoexhibition have potential application for issues and neighbourhoods in other urban, Western contexts where there is inequality – where communities may not be heard, or where the resources available (however restricted) are not being delivered in an equitable manner. Fink (Citation2012) describes the value of visual images (photographs taken by a professional photographer during a walking tour led by community members) to bring different insights to understandings of which practices, services and resources are embedded in the meanings of community, and for informing policy and practice about the experiences of inequality. Participative, creative or visual, co-produced methodologies can build trust and equalise power that may permit ‘knowledge mobilisation’ in effective ways (Grindell et al. Citation2022). The methodology we report in this paper can be positioned in the dynamic, evolving nexus between communities and those in positions of power, with the advocacy arising from the walkabout and photography process potentially presenting itself in a form that can be acted on – in the expectation that it can meet communities’ identified needs in an achievable way.

Our work raises some important issues for planning and public health about effective consultation. We use the word ‘effective’ here as an explicit reference to an outcome that tackled a community recognised need. The communities were able to access resources, via Community Infrastructure Levy in this case, leading to improvements in the local public realm. We hope that what we present here supports those struggling with questions of how to work with marginalised communities that have a defined health need, and are less likely to engage with standard local authority consultation methods. Our approach may not directly accord with decision-makers being able to ‘look through the eyes of a child’, but we believe it opened their eyes to how those parenting young children perceive their everyday environment.

This approach brought together distinct, often siloed, dimensions of the local authority; in this case political, public health and planning/design dimensions to focus on an issue relating to health inequality. We are not claiming this aspect as being unique in itself, however the more usual contact between these elements in local authority work may involve several different committees and committee cycles, with associated sub-groups action and officer reports. The threshold to start such a process would arguably have been an insurmountable barrier, and even if it had been able to lead to some similar outputs, the soft outcome of community empowerment through agency, would not have been achieved. As a methodology, this approach echoes several aspects of more recent engagement models, which also draw on participatory action research such Citizen Assembly (Česnulaitytė Citation2020) and Poverty Truth Commission (Poverty_Truth_Network Citation2022) albeit at a micro-scale and with a tightly defined local problem to solve. To note also, these approaches lie in stark contrast to another trend in citizen engagement, which see a rise in digital communications and online consultations that risk exacerbating inequalities (Boland et al. Citation2022). We suggest a method that places people-to-people discussion and relationship building as being essential components.

How may the funding systems themselves contribute towards inclusivity? In this case, it has been important to make a very direct connection between the health need and both identifying and successfully bidding to an existing funding pot. How might elements of this approach be possible elsewhere? Which aspects of funding systems might make them more open to this more ‘bottom-up’ approach? What are the implications for a similar approach in terms of its initiation; the existence and/or availability of the actors to make it happen; and the efficiency of use of resources compared to more standard ways of working for local authorities?

Recent experiences with COVID-19 and Black Lives Matter have focused the UK government’s attention towards geography, health and diverse communities, making this potentially productive area of policy-making, despite its multi-sectoral complexity. Multiple domains of policy are relevant including housing, parks, communities, education, child health & mental health, safety/safeguarding, environmental health/clean air, roads, and planning (Allport Citation2021). Social prescribing Link Worker roles being developed across the country (https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-8997/) could potentially lead Walkabouts as part of their roles. Further, universities have been asked to develop the ‘third pillar’ of their contribution – of civic responsibility to wellbeing and to communityFootnote6 – supporting approaches such as this may be one very effective way to take this forward (Goddard et al. Citation2016). Engaged academics’ ongoing local relationships and co-production processes may have a very important role to play in mediating trust and power processes without creating consultation fatigue.

A key aspect of future research into creative, locally-involved, engaged approaches would seem to be linking them to theories of change, and attempting to evaluate what builds energy and creativity for change, for example in partnership with commissioners, policymakers and practitioners in a timely, locally-contextualised way (Wye et al. Citation2015, Haining Citation2018). To be effective, evidence of need and potential for change need to align with the ‘drivers’ for policy-makers, commissioners, and practitioners (Places Citation2012), for example helping hard-pressed managers and commissioners meet budgetary targets while at the same time addressing UK health services’ commitment to tackling inequalities (Friedli Citation2013, NHS Citation2019). The emerging understanding of the role of early experiences in shaping children’s early predispositions offers new mechanisms by which social and physical environments may shape child development from before birth (Hertzman and Boyce Citation2010, Minh et al. Citation2017). This re-emphasises the importance of joined-up thinking between health and local authority commissioning and practice, to improve neighbourhood community experience, and to respond to priorities, such as providing trauma-responsive services (Bhushan et al. Citation2020, Morris et al. Citation2021).

Conclusion

Walkabouts with photography can be low-cost, effective methods to engage disadvantaged, diverse, minority ethnic and/or migrant communities in shaping change in their neighbourhood environment, empowering local change, and facilitating effective, equitable service delivery. Careful support through interpreters and established stakeholder community organisations is also vital. In England and Wales our methodology may be a route to supporting improvements in local environments through ‘Community Interest Levy’ funding directed by priorities established in the processes. In other countries, it may be possible to have impact through other ways to redirect available local resources toward ‘seldom heard’ and/or marginalised groups. We found a broad, pragmatic and responsive approach to stakeholder involvement at each stage was essential.

Geolocation information

51.454514 N, 2.587910 W (Bristol). More detailed Geolocation coordinates for the individual walkabouts could be added if requested.

Acknowledgment

We offer our thanks to all participants, child and adult, for their rich contributions at all stages of the process. We thank Bristol Somali Resource Centre, Barton Hill Activity Club, Wellspring Healthy Living Centre, The Network Community Development project, TALO Somali Women’s Advocacy and Empowerment Group, Cabot Primary School leadership team and Parent–Teacher Association – we would like in particular to acknowledge Abdullahi Farah, Samira Musse, Rhian Loughlin, Muhyadin Saed, Hibo Mahamoud and Caroline Ennion. The University of Bristol’s Public Engagement Department and Brigstow Institute have been supportive throughout, as well as financial assistance with refreshments/catering, photographic curating and printing, frames, and creche staff – we especially have appreciated support from Mireia Bes Garcia and Gail Lambourne. We also thank colleagues from the Sustainable Healthy Inclusive Neighbourhood Environments (SHINE) Health Integration Team, Bristol Health Partners, Living Streets, Bristol Architecture Centre including Georgina Bolton and Shankari Raj, Playing Out, Madge Dresser, and Bristol City Councillors (especially Marg Hickman, Ruth Pickersgill, Afzal Shah and Hibaq Jama) and Council staff including Nicola Ferris, April Richmond, Keith Houghton, Keith Chant, and Richard Fletcher.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tom Allport

Tom Allport is a Consultant Paediatrician for Sirona Care & Health in Bristol’s Community Children’s Health Partnership, and Honorary Senior Lecturer in the Centre for Academic Child Health in the University of Bristol. Working with children of forced migrant families in Bristol experiencing developmental difficulties has led him to study the experiential and interactional worlds of migrant families in British cities, and the ways in which ‘place’ can shape activity and opportunity. From this has emerged ideas and interventions termed ‘Find your village’, to support those who come to the ‘Global North’ from cultures where ‘it takes a village to raise a child.

Marcus Grant

Marcus Grant is Editor-in-Chief of Cities & Health and former deputy director of the World Health Organisation’s Collaborating Centre for Healthy Cities. With a background in ecological systems and urbanism, he is a practitioner-scholar working in healthy urban planning and planetary health. He is an expert advisor to the WHO and UN-Habitat, contributing to “Health as the Pulse of the New Urban Agenda’ and author of the WHO/UN Sourcebook: Integrating health into urban and territorial planning. Marcus is a Fellow of the Faculty of Public Health, a member of the Landscape Institute and is based in Bristol, England.

Vanessa Er

Vanessa Er is an Assistant Professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. She has an academic background in nutrition and have expertise in mixed method research. Her research interests include ethnic minority health, health inequalities, and the application of systems theory and complexity science in public health research. She is an advocate of participatory action research.

Notes

1. Online version of the NHS Long Term Plan – Chapter 2: More NHS action on prevention and health inequalities. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/online-version/chapter-2-more-nhs-action-on-prevention-and-health-inequalities/.

2. Reducing health inequalities associated with COVID-19: A framework for healthcare providers. NHS Providers and The Provider Public Health Network (November 2020) https://nhsproviders.org/media/690551/health-inequalities-framework.pdf.

3. Our invitation asked ‘Are you interested in what helps young children grow up happy, healthy and safe?’.

4. Short film about the ‘Find your village’ approach streamable from https://vimeo.com/374652881/79fae10d7e.

5. https://www.architecturecentre.org.uk/what-we-do/st-pauls-green-way/; https://www.bristol247.com/news-and-features/features/new-trail-in-st-pauls-brings-communities-together/.

6. For example, the University of Bristol is seeking to draw up a Civic University Agreement that sets out its vision of mutually-rewarding relationships with local communities; see also Truly Civic: Strengthening the connection between universities and their places. UPP Foundation 2019.

References

- Acevedo-Garcia, D., et al., 2020. Racial and ethnic inequities in children’s neighborhoods: evidence from the new child opportunity index 2.0. Health affairs, 39 (10), 1693–1701. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00735.

- Aerts, J., 2018. Shaping urbanization for children: a handbook on child-responsive urban planning. New York: UNICEF.

- Agnew, J., 2011. Space and place. In: J.A. Agnew and D.N Livingstone, eds. Handbook of geographical knowledge. New York: Sage.

- Allport, T., et al., 2019. ‘Like a life in a cage’: understanding child play and social interaction in Somali refugee families in the UK. Health & place, 56, 191–201. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.01.019.

- Allport, T.D., 2021. Improving outcomes for young children in refugee families: lessons from Somali parents’ experience of play and social interaction opportunities in the UK. Bristol, UK: Policy Bristol, University of Bristol. Available from: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/policybristol/policy-briefings/improving-outcomes-refugee-families/ [Accessed 12 Feb 2023].

- Almeida, L.M., et al., 2013. Maternal healthcare in migrants: a systematic review. Maternal and child health journal, 17 (8), 1346–1354. doi:10.1007/s10995-012-1149-x.

- Ataol, Ö., Krishnamurthy, S., and van Wesemael, P., 2019. Children’s participation in urban planning and design: a systematic review. Children, youth and environments, 29 (2), 27–47. doi:10.7721/chilyoutenvi.29.2.0027.

- Barton, H. and Grant, M., 2006. A health map for the local human habitat. The journal of the royal society for the promotion of health, 126 (6), 252253. doi:)10.1177/1466424006070466.

- Bawden, R., 2021. Towards action research systems. In: O. Zuber-Skerritt, ed. Action research for change and development. Melbourne, Australia: Routledge.

- Bell, M.F., et al., 2020. Children’s neighbourhood physical environment and early development: an individual child level linked data study. Journal of epidemiology and community health, 74 (4), 321–329. doi:10.1136/jech-2019-212686.

- Bhushan, D., et al., 2020. Roadmap for resilience: the California surgeon general’s report on adverse childhood experiences, toxic stress, and health. Office of the California Surgeon General. doi:10.48019/PEAM8812.

- Bird, J., Colliver, Y., and Edwards, S., 2014. The camera is not a methodology: towards a framework for understanding young children’s use of video cameras. Early child development and care, 184 (11), 1741–1756. doi:10.1080/03004430.2013.878711.

- Bixler, R.D., Floyd, M.F., and Hammitt, W.E., 2002. Environmental socialization: quantitative tests of the childhood play hypothesis. Environment and behavior, 34 (6), 795–818. doi:10.1177/001391602237248.

- Black, M.M., et al., 2017. Early childhood development coming of age: science through the life course. The Lancet, 389 (10064), 77–90. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31389-7.

- Boarin, P., Besen, P., and Haarhoff, E., 2018. Post-Occupancy evaluation of neighbourhoods: a review of the literature. Building research & information, 29 (2), 168–174. doi:10.1080/09613210010016857.

- Boland, P., et al., 2022. A ‘planning revolution’ or an ‘attack on planning’in England: digitization, digitalization, and democratization. International planning studies, 27 (2), 155–172. doi:10.1080/13563475.2021.1979942.

- Bondi, L., 2016. Emotional geographies. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. ISBN 1317144619.

- Brooks, F. and Kendall, S., 2013. Making sense of assets: what can an assets based approach offer public health? Critical public health, 23 (2), 127–130. doi:10.1080/09581596.2013.783687.

- Buchanan, A.E.A., 2004. The impact of government policy on social exclusion among children aged 0–13 and their families. London: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. SOCIAL_EXCLUSION_UNIT. HMSO. Available from: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/10998/7/impact_report_Redacted.pdf.

- Carpiano, R.M., 2009. Come take a walk with me: the “Go-Along” interview as a novel method for studying the implications of place for health and well-being. Health & place, 15 (1), 263–272. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.05.003.

- Carroll, P., et al., 2015. Kids in the city: children’s use and experiences of urban neighbourhoods in Auckland, New Zealand. Journal of urban design, 20 (4), 417–436. doi:10.1080/13574809.2015.1044504.

- Česnulaitytė, I., 2020. Models of representative deliberative processes. Innovative Citizen Participation and New Democratic Institutions: Catching the Deliberative Wave. Paris, France: OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/36f3f279-en.

- Chetty, R., Hendren, N., and Katz, L.F., 2016. The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: new evidence from the moving to opportunity experiment. The American economic review, 106 (4), 855–902. doi:10.1257/aer.20150572.

- Christian, H., et al., 2017. Relationship between the neighbourhood built environment and early child development. Health & place, 48, 90–101. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.08.010.

- Cohen, D.A., et al., 2015. Impact of park renovations on park use and park-based physical activity. Journal of physical activity & health, 12 (2), 289–295. doi:10.1123/jpah.2013-0165.

- Cole-Hamilton, I., Harrop, A., and Street, C., 2002. The value of children’s play and play provision: a systematic review of literature. New Policy Institute. Available from: http://www.sportdevelopment.org.uk/playliterature2002.pdf [Accessed 12 Feb 2023].

- Collins, C.R., Neal, Z.P., and Neal, J.W., 2017. Transforming social cohesion into informal social control: deconstructing collective efficacy and the moderating role of neighborhood racial homogeneity. Journal of urban affairs, 39 (3), 307–322. doi:10.1080/07352166.2016.1245079.

- Community Places, 2012. Achieving alignment. Belfast, UK: Community Places. Available from: https://www.communityplanningtoolkit.org/achieving-alignment [Accessed 12 Feb 2023].

- Cork, T., 2020. Twenty years after the new deal, what’s the future for Barton Hill? Bristol Live/Bristol Post, 26 Jan 2020, updated 18 Feb 2020. Available from: https://www.bristolpost.co.uk/news/bristol-news/twenty-years-after-new-deal-3764198 [Accessed 27 Nov 2022].

- Crespo, C.J., et al., 2001. Television watching, energy intake, and obesity in US children: results from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 155 (3), 360–365. doi:10.1001/archpedi.155.3.360.

- Davies, A.A., Basten, A., and Frattini, C., 2009. Migration: a social determinant of the health of migrants. Eurohealth, 16, 10–12.

- de Graaf, L., van Hulst, M., and Michels, A., 2015. Enhancing participation in disadvantaged urban neighbourhoods. Local government studies, 41 (1), 44–62. doi:10.1080/03003930.2014.908771.

- Dennis, S.F., Jr., et al., 2009. Participatory photo mapping (PPM): exploring an integrated method for health and place research with young people. Health & place, 15 (2), 466–473. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.08.004.

- Downe, S., et al., 2009. ‘Weighing up and balancing out’: a meta‐synthesis of barriers to antenatal care for marginalised women in high‐income countries. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics & gynaecology, 116, 518–529.

- Egli, V., et al., 2020. Understanding children’s neighbourhood destinations: presenting the kids-PoND framework. Children’s geographies, 18 (4), 420–434. doi:10.1080/14733285.2019.1646889.

- Eriksson, E., Fredriksson, A., and Syssner, J., 2022. Opening the black box of participatory planning: a study of how planners handle citizens’ input. European planning studies, 30 (6), 994–1012. doi:10.1080/09654313.2021.1895974.

- Evans, J. and Jones, P., 2011. The walking interview: methodology, mobility and place. Applied geography, 31 (2), 849–858. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2010.09.005.

- Fazel, M., et al., 2012. Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in high-income countries: risk and protective factors. The Lancet, 379 (9812), 266–282. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60051-2.

- Ferguson, A., 2019. Playing out: a grassroots street play revolution. Cities & health, 3 (1–2), 20–28. doi:10.1080/23748834.2018.1550850.

- Fink, J., 2012. Walking the neighbourhood, seeing the small details of community life: reflections from a photography walking tour. Critical social policy, 32 (1), 31–50. doi:10.1177/0261018311425198.

- Finlay, L., 2002. Negotiating the swamp: the opportunity and challenge of reflexivity in research practice. Qualitative research, 2, 209–230.

- Finlay, J.M. and Bowman, J.A., 2017. Geographies on the move: a practical and theoretical approach to the mobile interview. The professional geographer, 69 (2), 263–274. doi:10.1080/00330124.2016.1229623.

- Fjørtoft, I., 2001. The natural environment as a playground for children: the impact of outdoor play activities in pre-primary school children. Early childhood education journal, 29 (2), 111–117. doi:10.1023/A:1012576913074.

- Flyvbjerg, B., 2006. Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative inquiry, 12 (2), 219–245. doi:10.1177/1077800405284363.

- Foot, J. and Hopkins, T., 2010. A glass half-full: how an asset approach can improve community health and well-being. London: Improvement and Development Agency. Available from: https://www.local.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/glass-half-full-how-asset-3db.pdf [Accessed 12 Feb 2023].

- Friedli, L., 2013. ‘What we’ve tried, hasn’t worked’: the politics of assets based public health 1. Critical public health, 23 (2), 131–145. doi:10.1080/09581596.2012.748882.

- Gaidhane, A., et al., 2020. Photostory—a “Stepping Stone” approach to community engagement in early child development. Frontiers in public health, 8, 578814. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.578814.

- Galster, G.C., 2012. The mechanism(s) of neighbourhood effects: theory, evidence, and policy implications. In: M. van Ham, D. Manley, N. Bailey, L. Simpson, and D. Maclennan, eds. Neighbourhood effects research: new perspectives. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-2309-2_2.

- Goddard, J., Hazelkorn, E., and Vallance, P., 2016. The civic university: the policy and leadership challenges. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 178471772X.

- Golden, T., 2020. Reframing photovoice: building on the method to develop more equitable and responsive research practices. Qualitative health research, 30 (6), 960–972. doi:10.1177/1049732320905564.

- Grindell, C., et al., 2022. Improving knowledge mobilisation in healthcare: a qualitative exploration of creative co-design methods. Evidence & policy, 18 (2), 265–290. doi:10.1332/174426421X16436512504633.

- Gubrium, A. and Harper, K., 2016. Participatory visual and digital methods. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. ISBN 1315423014.

- Haining, S., 2018. How commissioners use research evidence. NIHR. Available from: https://evidence.nihr.ac.uk/collection/how-commissioners-use-research-evidence/ [Accessed 23 Sep 2022].

- Hammond, L., et al., 2011. Cash and compassion: the Somali Diaspora’s role in relief, development & peacebuilding. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Available from: https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/4f61b12d2.pdf [Accessed 12 Feb 2023].

- Harwood, D. and Collier, D.R., 2019. Talk into my GoPro, I’m making a movie!”: using digital ethnographic methods to explore children’s sociomaterial experiences in the woods. The Routledge international handbook of learning with technology in early childhood. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. ISBN 1315143046.

- Hawkley, L.C. and Cacioppo, J.T., 2010. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of behavioral medicine, 40 (2), 218–227. doi:10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8.

- Hertzman, C. and Boyce, T., 2010. How experience gets under the skin to create gradients in developmental health. Annual review of public health, 31 (1), 329–347. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103538.

- Hewitt, S., 2012. Healthy neighbourhood checks – review of outcomes. Officer report on behalf of the healthy city group of Bristol partnership. Bristol, UK: Bristol City Council.

- Hofferth, S.L. and Sandberg, J.F., 2001. Changes in American children’s time, 1981–1997. Advances in life course research, 6, 193–229. doi:10.1016/S1040-2608(01)80011-3.

- Hra, N., 2020. HRA decision tool - do I need NHS REC review? In: Ukri, M.R.C., NHS Health Research Authority, ed. ISBN: https://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/ethics/ [Accessed 11 Feb 2023].

- Jones, P., et al., 2008. Exploring space and place with walking interviews. Journal of research practice, 4, D2.

- Karsten, L. and van Vliet, W., 2006a. Children in the city: reclaiming the street. Children, youth and environments, 16, 151–167.

- Karsten, L. and van Vliet, W., 2006b. Increasing children’s freedom of movement: introduction. Children, youth and environments, 16, 69–73.

- Kindon, S., Pain, R., and Kesby, M., 2008. Participatory action research. International encyclopaedia of human geography. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier. ISBN 0080449107.

- Krishnamurthy, S., 2019. Reclaiming spaces: child inclusive urban design. Cities & health, 3 (1–2), 86–98. doi:10.1080/23748834.2019.1586327.

- Kusenbach, M., 2003. Street phenomenology: the go-along as ethnographic research tool. Ethnography, 4 (3), 455–485. doi:10.1177/146613810343007.

- Kyttä, M., 2004. The extent of children’s independent mobility and the number of actualized affordances as criteria for child-friendly environments. Journal of environmental psychology, 24 (2), 179–198. doi:10.1016/S0272-4944(03)00073-2.

- Kyttä, M., et al., 2015. The last free-range children? Children’s independent mobility in Finland in the 1990s and 2010s. Journal of transport geography, 47, 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2015.07.004.

- Kyttä, A.M., Broberg, A.K., and Kahila, M.H., 2012. Urban environment and children’s active lifestyle: SoftGIS revealing children’s behavioral patterns and meaningful places. American journal of health promotion, 26 (5), e137–148. doi:10.4278/ajhp.100914-QUAN-310.

- Lim, M.H., Eres, R., and Vasan, S., 2020. Understanding loneliness in the twenty-first century: an update on correlates, risk factors, and potential solutions. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 55 (7), 793–810. doi:10.1007/s00127-020-01889-7.

- Local Government Association, 2021. Working in partnership – how councils can work with the voluntary and community sector to increase civic participation, Local Government Association. Available from: https://www.local.gov.uk/publications/working-partnership-how-councils-can-work-voluntary-and-community-sector-increase#conclusion [Accessed 13 Feb 2023].

- Lomax, H., 2012. Contested voices? Methodological tensions in creative visual research with children. International journal of social research methodology, 15 (2), 105–117. doi:10.1080/13645579.2012.649408.

- Luchenski, S., et al., 2018. What works in inclusion health: overview of effective interventions for marginalised and excluded populations. The Lancet, 391 (10117), 266–280. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31959-1.

- Malherbe, N., et al., 2017. Photovoice as liberatory enactment: the case of youth as epistemic agents. In: M. Seedat, S. Suffla and D. Christie, eds. Emancipatory and participatory methodologies in peace, critical, and community psychology. New York: Springer. ISBN 3319634887.

- Mathie, A. and Cunningham, G., 2003. From clients to citizens: asset-based community development as a strategy for community-driven development. Development in practice, 13 (5), 474–486. doi:10.1080/0961452032000125857.

- Mccabe, A., et al., 2013. Making the links: poverty, ethnicity and social networks. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Mecking, O., 2018. Can local walking groups help solve urban issues? The Guardian, 14 Nov. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2018/nov/14/the-dutch-cities-using-walking-to-tackle-issues-from-vandalism-to-broken-streetlights.

- Miller, P., Votruba-Drzal, E., and Coley, R.L., 2019. Poverty and academic achievement across the urban to rural landscape: associations with community resources and stressors. RSF: the Russell Sage foundation journal of the social sciences, 5 (2), 106–122. doi:10.7758/rsf.2019.5.2.06.

- Mills, J., 2014. Community profile - Somalis living in Bristol. Bristol, UK: Bristol City Council.

- Minh, A., et al., 2017. A review of neighborhood effects and early child development: how, where, and for whom, do neighborhoods matter? Health & place, 46, 155–174. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.04.012.

- Minkler, M. and Wallerstein, N., 2011. Community-based participatory research for health: from process to outcomes. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

- Monaghan, J., 2019. Engagement of children in developing healthy and child-friendly places in Belfast. Cities & health, 3 (1–2), 29–39. doi:10.1080/23748834.2018.1527175.

- Moore, R.C., 2017. Childhood’s domain: play and place in child development. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. ISBN 1315121891.

- Morgan, A. and Ziglio, E., 2007. Revitalising the evidence base for public health: an assets model. Promotion & education, 14 (2_suppl), 17–22. doi:10.1177/10253823070140020701x.

- Morris, A.S., et al., 2021. The heart of the matter: developing the whole child through community resources and caregiver relationships. Development and psychopathology, 33 (2), 533–544. doi:10.1017/S0954579420001595.

- NHS, 2019. The NHS Long Term Plan. Available from: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/.

- Nordström, M., 2010. Children’s views on child-friendly environments in different geographical, cultural and social neighbourhoods. Urban Studies, 47 (3), 514–528. doi:10.1177/0042098009349771.

- Nykiforuk, C.I., Vallianatos, H., and Nieuwendyk, L.M., 2011. Photovoice as a method for revealing community perceptions of the built and social environment. International journal of qualitative methods, 10 (2), 103–124. doi:10.1177/160940691101000201.

- O’Brien, M., et al., 2000. Children’s independent spatial mobility in the urban public realm. Childhood, 7 (3), 257–277. doi:10.1177/0907568200007003002.

- O’Donnell, C.A., et al., 2016. Reducing the health care burden for marginalised migrants: the potential role for primary care in Europe. Health policy, 120 (5), 495–508. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.03.012.

- Parliament, U., 2012. Health and Social Care Act. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2012/7/contents/enacted.

- Pascoe, E.A. and Smart Richman, L., 2009. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychological bulletin, 135 (4), 531. doi:10.1037/a0016059.

- Pierce, J. and Lawhon, M., 2015. Walking as method: toward methodological forthrightness and comparability in urban geographical research. The professional geographer, 67 (4), 655–662. doi:10.1080/00330124.2015.1059401.

- Poverty Truth Network, 2022. What is a poverty truth commission? Poverty Truth Network. Available from: https://povertytruthnetwork.org/commissions/what-is-a-poverty-truth-commission/ [Accessed 13 Dec 2022].

- Sallis, J.F. and Glanz, K., 2006. The role of built environments in physical activity, eating, and obesity in childhood. The future of children, 16 (1), 89–108. doi:10.1353/foc.2006.0009.

- Sampson, R.J., Morenoff, J.D., and Earls, F., 1999. Beyond social capital: spatial dynamics of collective efficacy for children. American sociological review, 64 (5), 633–660. doi:10.2307/2657367.

- Sampson, R.J. and Sharkey, P., 2008. Neighborhood selection and the social reproduction of concentrated racial inequality. Demography, 45 (1), 1–29. doi:10.1353/dem.2008.0012.

- Sarti, A., et al., 2018. Around the table with policymakers: giving voice to children in contexts of poverty and deprivation. Action research, 16 (4), 396–413. doi:10.1177/1476750317695412.

- Schneidert, M., et al. 2003. The role of environment in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Disability and rehabilitation, 25, 588–595.

- Shaw, B., et al., 2013. Children’s independent mobility: a comparative study in England and Germany (1971-2010). London, UK: Policy Studies Institute.

- Talbot, D., 2013. Early parenting and the urban experience: risk, community, play and embodiment in an East London neighbourhood. Children’s geographies, 11 (2), 230–242. doi:10.1080/14733285.2013.779450.

- Teixeira, S. and Gardner, R., 2017. Youth-led participatory photo mapping to understand urban environments. Children and youth services review, 82, 246–253. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.09.033.

- Undiyaundeye, F., 2014. Outdoor play environment in early childhood for children. European journal of social science education and research, 1 (1), 14–17. doi:10.26417/ejser.v1i1.p14-17.

- UNICEF, 2018. Child friendly cities and communities handbook, Available from: https://www.unicef.org/eap/reports/child-friendly-cities-and-communities-handbook [Accessed 11 Feb 2023].

- Wang, C. and Burris, M.A., 1997. Photovoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health education & behavior, 24 (3), 369–387. doi:10.1177/109019819702400309.

- Wang, D., Choi, J.-K., and Shin, J., 2020. Long-term neighborhood effects on adolescent outcomes: mediated through adverse childhood experiences and parenting stress. Journal of youth and adolescence, 49 (10), 2160–2173. doi:10.1007/s10964-020-01305-y.

- Wang, C.C. and Redwood-jones, Y.A., 2001. Photovoice ethics: perspectives from Flint photovoice. Health education & behavior, 28, 560–572.

- Warner, D.F. and Brown, T.H., 2011. Understanding how race/ethnicity and gender define age-trajectories of disability: an intersectionality approach. Social science & medicine, 72 (8), 1236–1248. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.034.

- Woolley, H.E. and Griffin, E., 2015. Decreasing experiences of home range, outdoor spaces, activities and companions: changes across three generations in Sheffield in north England. Children’s geographies, 13 (6), 677–691. doi:10.1080/14733285.2014.952186.

- Wridt, P., 2010. A qualitative GIS approach to mapping urban neighborhoods with children to promote physical activity and child-friendly community planning. Environment and planning B, planning & design, 37 (1), 129–147. doi:10.1068/b35002.

- Wye, L., et al., 2015. Evidence based policy making and the ‘art’of commissioning–how English healthcare commissioners access and use information and academic research in ‘real life’ decision-making: an empirical qualitative study. BMC health services research, 15 (1), 430. doi:10.1186/s12913-015-1091-x.

- Wyndham-West, C.M., Odger, A., and Dunn, J.R., 2022. A narrative-based exploration of aging, precariousness and housing instability among low-income older adults in Canada. Cities & health, 6 (3), 587–601. doi:10.1080/23748834.2021.1919976.

APPENDIX

‘Are you interested in how young Somali children grow up happy, healthy and safe?’

‘Walkabout’ [place, date]

Guide for facilitators of small groups (aiming for 5-7 people)

After we have explained the process, please can you lead a group around the local area – we will give you a map to follow. Groups will be led by pairs of facilitators, English- and Somali-speaking.

Responsibilities:

With your co-facilitator, please can you help the group look for examples of ways in which the local environment helps and what gets in the way of pre-school children’s opportunities in the aspects of life we are focusing on:

play

being active

eating healthily

meeting up with other children

Please:

encourage people to find, and comment on aspects of the local area they know

help them keep (roughly) to the suggested route (it is fine to go on diversions but it would be good if you can make it round most of the route suggested)

get photos taken (by participants and facilitators) of features the group identify as examples

if possible, help people make notes of what each photo shows

discuss with the group what three key messages they would like to feed back to the whole group

help them stay safe – remind them to keep an eye out for traffic and not stand in the road!

help the group return to the starting point for shared discussion at 12.15

when you get back, point participants towards the team uploading photos

Please can you bring a phone or camera with you to take photos, and the wire that connects it to a computer if possible. We will have some iPads or tablets for use – you can lend these to participants. Please make sure any borrowed iPads/tablets are returned!

Somali-catered refreshments will be provided after the discussion.

Any questions before or on the day to:

[organisers + tel numbers]