ABSTRACT

Urbanisation is increasing, while global biodiversity is decreasing. Through ‘urban rewilding’ cities could help tackle this biodiversity crisis, while exploiting the benefits of urban nature for residents. Private residential gardens, which have potential to support significant biodiversity, should be a primary focus. Yet their proportion of vegetated space is decreasing through changes made by residents, negatively impacting biodiversity. Small adaptations to private gardens can turn them into wildlife habitat, but understanding residents’ behaviour is critical to developing intervention strategies for this. This paper presents a scoping review of existing literature on understanding intent-orientated, pro-environmental behaviours with a focus on rewilding in urban gardens. The literature is mapped to assess the state of knowledge; it is then coded, using the ‘COM-B’ model of behaviour, to identify the capability, opportunity and motivation factors forming barriers and facilitators to residents engaging in rewilding activity in their gardens. The results show that all COM-B factors need to be considered to understand urban rewilding behaviour, but that opportunity and motivation factors have more influence, particularly reflective motivation. They indicate that facilitators are more significant than barriers and highlight an important body of work that has implications for practice and policy aimed at influencing urban rewilding.

Introduction

Sustainable urbanisation

Urbanisation is increasing, with the 55% of the world’s population estimated to live in urban areas projected to rise to 68% by 2050 (UN Citation2018). The UN Sustainable Development Goal number 11 aims to make cities resilient and sustainable, including targets to improve access to green spaces, protect natural heritage and reduce the environmental impact of cities by 2030 (UN Citation2015). To support this transition, cities such as London and Adelaide have committed to the National Park City Charter and becoming greener, healthier environments where people and nature are better connected (National Park City Foundation Citation2022).

Biodiversity crisis

In parallel, global biodiversity is decreasing: a 20% decline since 1900 in abundance of native species across most major land habitats has put one million plant and animal species at risk of extinction, with the primary cause being changes in land and sea use (Brondizio et al. Citation2019). To halt this unprecedented biodiversity loss, the UN Sustainable Development Goal number 15 aims to restore life on land, by promoting sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems and reversing habitat degradation (UN General Assembly Citation2015). Urban areas are identified as an ecosystem with importance for biodiversity conservation and ecosystem services in the International Union of Conservation Nature’s ‘Global Ecosystem Typology’ (Keith et al. Citation2022). In addition, human interaction with nature is recognised as fundamental to quality of life by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) through Nature’s Contributions to People, encompassing pollination and seed dispersal; regulation of climate, water and air quality; and cultural benefits from learning and inspiration to physical and psychological experiences (Brondizio et al. Citation2019).

Urban rewilding

‘Urban rewilding’ (Prior and Brady Citation2017) and ‘mini rewilding’ (Stone Citation2019) have been advocated as ways for cities to help tackle the biodiversity crisis, while exploiting the many benefits of urban nature for the functioning of cities and wellbeing of their residents (ZSL Citation2022). ‘Rewilding’, understood as a conservation approach of reinstating natural processes to restore ecosystems (Pettorelli et al. Citation2019), requires rethinking for application to an urban context. For the purposes of this study, rewilding is defined loosely (Jørgensen Citation2015), and interpreted for an urban context as incorporating ‘native plants and animals into urban infrastructure’ (Mills et al. Citation2017).

Urban rewilding has tangible benefits for biodiversity conservation. Some animal species, including foxes, herring gulls, hedgehogs (Hayhow et al. Citation2019) and bumblebees (Samuelson et al. Citation2018) are proving more successful in urban areas than rural areas. Further, species such as peregrine falcons are city specialists, benefiting from their concentrations of tall buildings and feral pigeons (Kettel et al. Citation2018). Conservation measures in cities have achieved increases in numbers of certain bat species (Hayhow et al. Citation2016). Small actions, for example providing ponds, nest boxes and bird food, have been shown to be effective in cities (Sutherland et al. Citation2020), with urban ponds attracting greater biodiversity than rural ones (Hill et al. Citation2016).

Rewilding would also benefit city functioning. Increased vegetation and water cover afford ‘ecosystem services’, natural processes that are beneficial to humans (Costanza et al. Citation1997), which are enhanced by biodiversity (Harrison et al. Citation2014). This can counter environmental problems that are prevalent in cities, from air pollution (Redondo-Bermúdez et al. Citation2021) to overheating (Zhang Citation2020) and surface flooding (Kadaverugu et al. Citation2021), aiding adaptation to climate change (Gill et al. Citation2007).

People living and working in cities would also benefit from urban rewilding, as contact with nature in urban areas offers proven health and wellbeing benefits for residents (Kondo et al. Citation2018), with more biodiverse spaces having the greatest benefit on some health outcomes (Houlden et al. Citation2021). Further social benefits of urban greening include reduction in crime (Kondo et al. Citation2018).

Nevertheless, urban rewilding might also have undesirable impacts on biodiversity, cities and people, which should be confronted. These could affect indigenous wildlife by favouring invasive alien species of plants and animals, and introducing novel diseases (ZSL Citation2022). People could be affected by established communities being displaced through inflation of property prices caused by ‘green gentrification’, and increasing human-wildlife conflict through increased incidence of road collisions, pet attacks, garden pests and vermin (ZSL Citation2022).

Research rationale and aim

In July 2019, the National Park City Foundation declared London as the world’s first National Park City, a movement encouraging Londoners to make London greener, healthier and wilder (Mayor of London Citation2023). The latest policy in England focuses on greening new buildings and spaces with ‘biodiversity net gain’, meaning an improvement in habitat value after land is developed, of 10% soon to become a condition of planning permission in England (UK Parliament Citation2020). The Mayor of London’s Environment Strategy embodies this approach but also acknowledges the need for guidance for residents on managing gardens for biodiversity (Greater London Authority Citation2018).

Private residential gardens should be a primary focus for urban rewilding, as they constitute a significant cumulative land area – one quarter of major UK cities (Loram et al. Citation2007) – and act as wildlife corridors connecting larger green spaces (Vergnes et al. Citation2013). They therefore have potential to support significant biodiversity (Smith et al. Citation2005), especially when considered at a neighbourhood scale (Goddard et al. Citation2009), yet promoting their conservation is often overlooked in favour of larger, public green spaces (ZSL Citation2022). Consequentially, the proportion of vegetated space in private gardens, estimated at 62% in the UK (Bonham et al. Citation2019), is decreasing due to changes in how residents manage their gardens, negatively impacting biodiversity (Smith Citation2011). A recent survey found one tenth of UK householders had replaced their lawn with artificial grass and one quarter had paved over their front garden to create car parking (Aviva Citation2022).

There are many households with access to a private garden, giving individuals the opportunity to adapt their outdoor spaces to positively impact on biodiversity. Data from the Office for National Statistics (Citation2020) suggests that 88% of residents in Great Britain have access to a private or shared garden averaging 333 m2. This comprises 97% of those living in a house and 66% of those living in a flat. Small adaptations to private gardens can turn them into a habitat for wildlife, but understanding residents’ behaviour is critical to developing intervention strategies to enable this (Webb and Moxon Citation2021).

To influence behaviour, it is important to specify the behaviour in question as closely as possible. The need for such specificity is highlighted by the vast heterogeneity and inconsistency in pro-environmental behaviours. For example, a person can behave environmentally in terms of recycling while also regularly driving short distances that could otherwise be taken by active travel; the determinants of each of these behaviours are different (Bamberg and Rees Citation2015).

This review aims to scope the existing literature on urban rewilding with regard to understanding the behaviour of adapting private gardens to support biodiversity. An improved understanding of urban-rewilding behaviour will in turn help to develop intervention strategies to influence behaviour change, specifically in London.

Method

The study protocol for this scoping review and the proposed follow-on research has been published previously (Webb and Moxon Citation2021). The methods specific to this scoping review are presented here.

Study design

A scoping review approach was selected as this is an emerging research field with heterogeneity in research questions, variables and approaches.

Search terms

A systematic search of the peer reviewed literature was conducted using the following search string:

(pro-environment* OR ‘pro environmental’ OR ‘positive environmental’ OR ‘positive environment’ OR proenvironment* OR eco-conscious OR ‘eco conscious’ OR bio-diversity OR biodiversity OR re-wild* OR rewild* OR eco-friendly OR ‘eco friendly’ OR green) AND (cities OR town* OR city OR urban* OR suburban OR sub-urban) AND (Behaviour OR Behavior)

A separate search was conducted for gardening for biodiversity using the following search string, searching for the terms within the title or keyword fields only:

(biodiversity OR bio-diversity OR nature OR wildlife) AND garden*[title])

Sources of information

The following databases and search engines were searched:

BioOne

EBSCO Host

Science.gov

PubMed

Google scholar.

The authors also reviewed the grey literature, specifically reports from the UK Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), and third sector organisations such as the British Trust for Ornithology, the Centre for Behaviour and the Environment, Conservation Evidence, Earthwatch Europe, the Greater London Authority, Rewilding Britain, Rewilding Earth, Rewilding Europe, the Royal Horticultural Society, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, the Wildlife Trusts, the Woodland Trust and the World Wildlife Fund. The websites of these organisations were searched using the terms behaviour and rewilding, gardening for nature, gardening for wildlife, and gardening for biodiversity.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This review was inclusive of qualitative and quantitative research methodologies both experimental and observational. Papers not focused on understanding intent-orientated pro-environmental behaviour related to urban rewilding were excluded. Papers not considered research, such as commentary articles or opinion pieces, were excluded. No date range was set.

Screening of the literature

Use of a conceptual framework

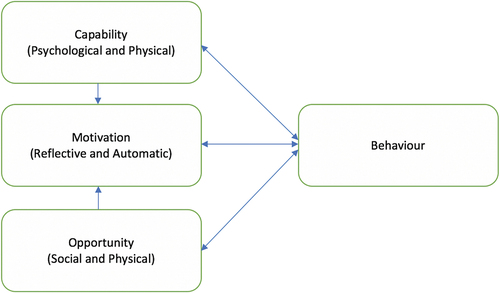

This scoping review used a conceptual behavioural model to screen the literature, to elucidate the understanding and influencing of intent-orientated pro-environmental behaviour with a focus on urban rewilding. The COM-B model shown in postulates that behaviour comes about from an interaction between one’s capability to perform a behaviour, the opportunity, and motivation to carry out that behaviour (Michie et al. Citation2011).

Psychological capability relates to the knowledge or psychological skills, strength or stamina to engage in the necessary mental processes to perform a behaviour; physical capability is the physical skill, strength or stamina. Physical opportunity is opportunity afforded by the environment such as time, resources, locations, cues, or physical affordance to perform a behaviour; social opportunity is the opportunity afforded by interpersonal influences, social cues and cultural norms that influence the way that we think about things. Reflective motivation is the reflective processes involving plans (intentions) and evaluations of a specific behaviour; automatic motivation is the automatic processes involving emotional reactions, desires, impulses, inhibitions, drive states and reflex responses (Michie et al. Citation2023).

The COM-B model was selected as it sits at the centre of a comprehensive intervention development framework, the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) (Michie et al. Citation2011) allowing for the findings to support the development of intervention strategies to facilitate behavioural change.

Screening process

The research team first screened the titles, then the abstracts, before a full review, excluding those not relevant to the research aim at each stage. Due to the large amount of identified literature, the papers were divided amongst the research team members. Where a team member was unsure whether to include or exclude a particular paper, a discussion took place and a decision was made with at least one other research team member. A hand search of the included papers was conducted to identify any additional relevant papers. The final papers included within this scoping review were divided between the research team for data extraction using the components of the COM-B model. In addition, the literature was mapped by date of publication, population and study design, to provide an understanding of the current state of the evidence (James et al. Citation2016). The final coding against the COM-B components was reviewed by the two lead researchers, with differences discussed before the final coding was agreed.

Results

Description of the included literature

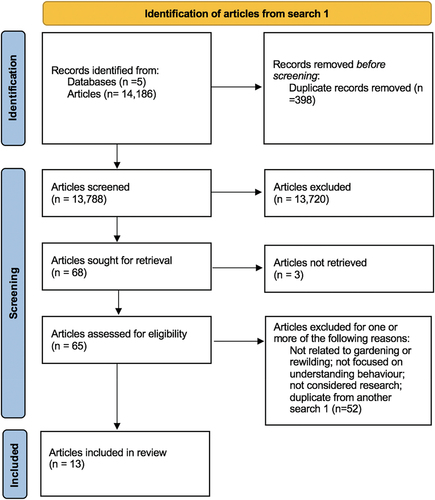

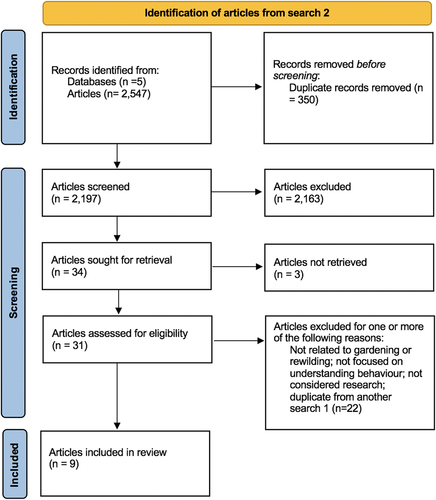

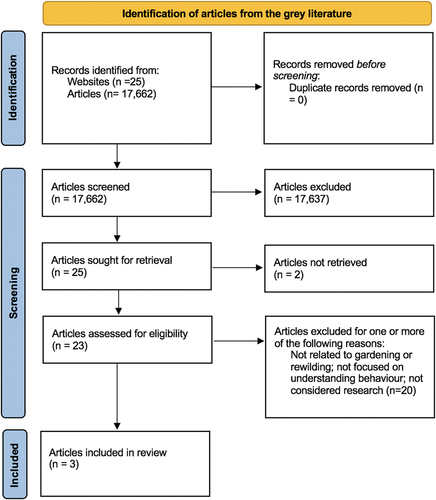

The retrieval of articles from across the three searches is presented in . In total across the three searches 34,395 records were identified; after the duplicates were removed 33,647 remained. Following the screening of the identified articles 25 articles were included in this scoping review. Search 1 was completed in July 2021, search 2 was completed in May 2021, and search 3, of the grey literature, took place in June 2021.

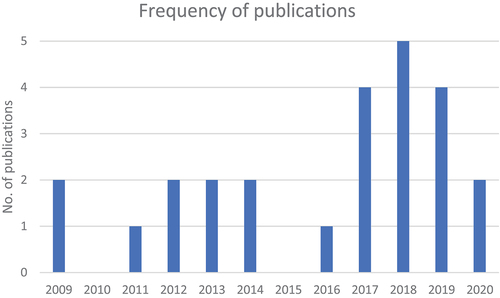

presents the frequency of publications in the area of understanding intent orientated rewilding behaviour in relation to urban gardens. The first paper identified in this review was published in 2009. Greater focus has been placed on this area since 2017, with 4 articles identified in this year, 5 in 2018, 4 in 2019, and 2 in 2020. However, this is clearly still an under-researched subject area.

Seven of the included articles were literature reviews. In most cases, these reviews included literature focused on the psychology of rewilding and conservation behaviours (DEFRA Citation2008, Citation2020, Okvat and Zautra Citation2011, Bauer and von Atzigen Citation2019, Clayton Citation2019, Owens and Wolch Citation2019, Sweeney et al. Citation2019). When coding these articles against the constructs of the COM-B model only factors related to urban rewilding were considered. This, to the knowledge of the authors, is the first scoping review with a specific focus on urban rewilding in relation to private gardens.

The literature review did not reveal any consensus in the field on the definition of urban rewilding in gardens, but the researchers appraised what should be included in, or added to, the study’s adopted definition of incorporating ‘native plants and animals into urban infrastructure’ (Mills et al. Citation2017). The terminology identified as equating to urban rewilding in the literature ranged from the conceptual, such as ‘wilderness and rewilding’ (Bauer et al. Citation2009), ‘nature-based solutions’ (van der Jagt et al. Citation2017) and ‘human-nature interconnectedness’ (Lewis and Townsend Citation2014), to the more pragmatic, such as ‘sustainable gardening practices’ (Coisnon et al. Citation2019), ‘environmentally friendly gardening practices’ (Lewis et al. Citation2018) and ‘pro-biodiversity behaviours’ (Deguines et al. Citation2020). Specific examples of activity identified as rewilding behaviour included ‘selecting plants that benefit birds’, ‘avoiding non-native plants’ and ‘leaving space for wild animals’ (Coisnon et al. Citation2019); preferring ‘a “messier” appearance’ and shunning ‘synthetic chemical pesticides and fertilizers’ (Lewis et al. Citation2018); providing ‘nectar resources’ and ‘features benefiting butterflies’ (Deguines et al. Citation2020); and composting (Nova et al. Citation2020). Conversely, behaviour opposed to rewilding included pesticide use (Deguines et al. Citation2020) and ‘fencing [being] used to exclude predators such as foxes’ (Sweeney et al. Citation2019).

The remaining 18 articles were primary research (Bauer et al. Citation2009, Shwartz et al. Citation2012, van Heezik et al. Citation2012, Goddard et al. Citation2013, van Heezik et al. Citation2013, Canuel et al. Citation2014, Lewis and Townsend Citation2014, Hobbs and White Citation2016, Coldwell and Evans Citation2017, Mumaw and Bekessy Citation2017, van der Jagt et al. Citation2017, Webster et al. Citation2017, Beumer Citation2018, Lewis et al. Citation2018, Maller and Farahani Citation2018 [unpublished], Coisnon et al. Citation2019, Deguines et al. Citation2020, Nova et al. Citation2020). Many made use of survey data (n = 6). Four articles are considered mixed methods primary research with 8 qualitative studies. The primary research took place in many areas across the world including Australia (n = 2), Canada (n = 2), France (n = 2), the Netherlands (n = 1), New Zealand (n = 1), Portugal (n = 1), Switzerland (n = 2), the UK (n = 4) and three studies across multiple European countries.

The 18 articles identified in the search of the peer-reviewed literature were published across a wide range of journals (American Journal of Community Psychology, n = 1; Australasian Journal of Environmental Management, n = 1; Wildlife Research, n = 1; Conservation Biology, n = 1; Ecological Economies, n = 1; Ecology and Society, n = 1; Ecosystems, n = 1; Environmental Research, n = 1; Journal of Environmental Management, n = 1; Gaceta Sanitaria, n = 1; Science of the Total Environment, n = 1; Social Science Research, n = 1; PLoS ONE, n = 3; Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, n = 2; EcoHealth, n = 1), with 1 conference paper, and 3 book chapters.

Understanding urban rewilding in relation to urban private gardens

Analysis of the literature against the COM-B components of psychological capability, physical capability, physical opportunity, social opportunity, reflective motivation and automatic motivation, and the demographic factors related to the behaviour of urban rewilding in private gardens are presented in .

Table 1. The barriers and facilitators for urban rewilding in private gardens.

All COM-B categories were found in the literature with multiple factors that potentially influence behaviour identified. Opportunity and motivation components accounted for more factors than capability components. Reflective motivation generated the most factors, while physical capability generated the least. Encouragingly, more facilitators of than barriers to urban rewilding were found, across all categories except physical capability.

Capability

Psychological capability is more widely cited than physical capability in facilitating urban-rewilding behaviour. A lack of knowledge was identified as a barrier and facilitator to behaviour (DEFRA Citation2008, van Heezik et al. Citation2012, Citation2013, Hobbs and White Citation2016, Coldwell and Evans Citation2017, Clayton Citation2019, Deguines et al. Citation2020). Specifically, ecological awareness (Webster et al. Citation2017, Lewis et al. Citation2018, Bauer and von Atzigen Citation2019) and biodiversity knowledge (DEFRA Citation2008, Coldwell and Evans Citation2017), particularly about common species and their needs (van Heezik et al. Citation2012, Deguines et al. Citation2020), including that gained from participation in wildlife gardening schemes (Mumaw and Bekessy Citation2017, Deguines et al. Citation2020) or visiting the countryside (Coldwell and Evans Citation2017) were facilitators of behaviour. In contrast, low awareness of gardens’ biodiversity value (Beumer Citation2018), poor knowledge of opportunities for gardening for wildlife (Hobbs and White Citation2016) and of species’ native status (van Heezik et al. Citation2012) were barriers. Psychological capabilities, whether barriers or facilitators, were linked to early-life determinants of attitudes to nature (Bauer et al. Citation2009).

Barriers were observed in terms of physical capability, with lack of physical capacity to garden preventing urban rewilding activities being carried out (Lewis et al. Citation2018) and age-related decline sometimes slowing the pace of such activities (Mumaw and Bekessy Citation2017). Developing skills, particularly in relation to the use of tools to monitor and track garden wildlife, were facilitators in the physical capability domain (Hobbs and White Citation2016).

Opportunity

Physical and social opportunity are cited comparably widely as determinants of urban-rewilding behaviour. Physical barriers to urban rewilding included lack of space (Lewis et al. Citation2018, Deguines et al. Citation2020), lack of time (Mumaw and Bekessy Citation2017, Lewis et al. Citation2018), money (Hobbs and White Citation2016, Lewis et al. Citation2018, Bauer and von Atzigen Citation2019) and lack of plant availability (Lewis et al. Citation2018). The physical cue of living in an urbanised environment was also an apparent deterrent to rewilding behaviour (Deguines et al. Citation2020), maybe due to a lack of interaction with the natural world (Clayton Citation2019). The physical environment might impact in the moment behavioural decisions, for example, a period of drought might hinder gardening for biodiversity (Canuel et al. Citation2014).

Physical facilitators comprised access to funding (van der Jagt et al. Citation2017), or a disposable income to spend on supporting resources (van Heezik et al. Citation2013, Canuel et al. Citation2014, Hobbs and White Citation2016, Bauer and von Atzigen Citation2019), access to equipment (Hobbs and White Citation2016) and reliable information and expertise (van der Jagt et al. Citation2017, Coisnon et al. Citation2019). Access to land (van der Jagt et al. Citation2017), resources (Hobbs and White Citation2016), and owning a garden, particularly a large one (Coisnon et al. Citation2019), encouraged rewilding behaviour. Physical cues of living in a more rural context (Coisnon et al. Citation2019) in a suitable location for rewilding (Sweeney et al. Citation2019) were conducive to rewilding behaviour, as was having time to spend gardening (Nova et al. Citation2020), access to local community projects (Shwartz et al. Citation2012, Hobbs and White Citation2016), and an opportunity to interact with nature (Shwartz et al. Citation2012, Hobbs and White Citation2016, Coldwell and Evans Citation2017, Bauer and von Atzigen Citation2019, Owens and Wolch Citation2019, DEFRA Citation2020).

Social barriers to rewilding behaviour included cultural norms concerning societal values for gardens (Sweeney et al. Citation2019); interpersonal influences such as family garden rules (Lewis et al. Citation2018); and sensitivity to neighbours’ concerns or a desire to display one’s personal values about neatness, especially in front gardens (Goddard et al. Citation2013, Mumaw and Bekessy Citation2017, Lewis et al. Citation2018). Nevertheless, displaying personal values about wildness can be a facilitator (Lewis et al. Citation2018), as can social influences (Bauer and von Atzigen Citation2019), observing other gardens, including those of neighbours (Goddard et al. Citation2013, Lewis et al. Citation2018); there is less pressure to conform to neighbourhood standards of tidiness in back gardens (Goddard et al. Citation2013). Positive interpersonal influences on urban rewilding included green-minded people persuading others (DEFRA Citation2008), co-creation (van der Jagt et al. Citation2017, Sweeney et al. Citation2019), wildlife-friendly family garden rules (Lewis et al. Citation2018), encouragement of wildlife-friendly gardening (Deguines et al. Citation2020) and belonging to a community of wildlife observers (Hobbs and White Citation2016, Deguines et al. Citation2020).

Motivation

Reflective motivation is more widely cited than automatic motivation in understanding urban-rewilding behaviour. Barriers and facilitators in the reflective motivation domain are the most widely cited of the COM-B components.

It is suggested that people approach specific conservation practices based on values that are relevant to them (Clayton Citation2019). Reflective motivation forming facilitators involved holding an environmentally focused world view or ‘cultural theory’ perspective (Beumer Citation2018, Bauer and von Atzigen Citation2019), resulting in ecological awareness (Webster et al. Citation2017, Lewis et al. Citation2018) or seeing oneself as part of nature (Bauer et al. Citation2009, Lewis and Townsend Citation2014, Sweeney et al. Citation2019); and having a positive attitude to civic environmentalism and environmental stewardship (van Heezik et al. Citation2013, Lewis and Townsend Citation2014, Mumaw and Bekessy Citation2017, Webster et al. Citation2017, Lewis et al. Citation2018, Owens and Wolch Citation2019, Nova et al. Citation2020). Conversely, having a cultural theory perspective that is not conducive to environmental awareness was identified as a barrier, as was prioritising other factors, such as the garden’s functionality, tidiness or low maintenance requirements (Beumer Citation2018, Lewis et al. Citation2018, Bauer and von Atzigen Citation2019). However, some have a preference for more natural landscapes (Clayton Citation2019).

Valuing gardens for relaxation outdoors (Okvat and Zautra Citation2011, Beumer Citation2018), and being able to choose the pace and extent of rewilding activities (Mumaw and Bekessy Citation2017) were identified as facilitators. Other reflective motivations facilitating urban-rewilding behaviour included helping biodiversity (Goddard et al. Citation2013, Mumaw and Bekessy Citation2017, Lewis et al. Citation2018), native species (Mumaw and Bekessy Citation2017, Maller and Farahani Citation2018) or the environment generally (Mumaw and Bekessy Citation2017, Beumer Citation2018, Lewis et al. Citation2018, Nova et al. Citation2020); creating a retreat (Okvat and Zautra Citation2011) or local green space (Maller and Farahani Citation2018) to enhance one’s connection to nature in the city (Okvat and Zautra Citation2011, Goddard et al. Citation2013, Sweeney et al. Citation2019); and the perception of having local or national environmental impact (Coldwell and Evans Citation2017). Conversely, focusing on having a global impact on environmental issues could be a barrier by deterring local action in one’s own garden (Coldwell and Evans Citation2017). Wanting to practice gardening (Mumaw and Bekessy Citation2017, Coisnon et al. Citation2019), either to increase existing knowledge or try something new (Mumaw and Bekessy Citation2017), and capitalise on its educational value for children (Coisnon et al. Citation2019) were important motivators for rewilding behaviour.

Reflective motivations forming barriers to urban rewilding included wanting to discourage certain species (Maller and Farahani Citation2018), particularly predators (Sweeney et al. Citation2019); and being concerned about human-wildlife conflict or safety and wellbeing (Maller and Farahani Citation2018). Other reasons for not rewilding were aesthetic preferences (Lewis et al. Citation2018), such as a strong attachment to an established garden’s form or style (Mumaw and Bekessy Citation2017), controlling unwanted vegetation (Deguines et al. Citation2020) and preference for ornamental gardens prompting chemical use (Coisnon et al. Citation2019).

Rewilding was more likely to be undertaken if it was compatible with the gardener’s aesthetic (Mumaw and Bekessy Citation2017, Beumer Citation2018, Lewis et al. Citation2018) and functional preferences (Mumaw and Bekessy Citation2017, Coisnon et al. Citation2019). Observing positive results of citizen science initiatives (Deguines et al. Citation2020) also facilitated rewilding. Positive interactions with local wildlife (Mumaw and Bekessy Citation2017) and having sources of ideas (Lewis et al. Citation2018) were shown to motivate people to carry out rewilding activities.

Automatic motivations involving negative emotional responses to nature, such as feeling threatened by it or compelled to control its appearance, were seen as barriers to urban-rewilding behaviour. However, feeling these concerns were addressed appropriately by a trustworthy source was found to be a facilitator (Bauer et al. Citation2009). Other facilitators were automatic behaviour prompted by positive past experiences (Lewis et al. Citation2018), including a connection to nature in childhood (Lewis and Townsend Citation2014), which can determine attitudes to nature in later life (Bauer et al. Citation2009, Bauer and von Atzigen Citation2019). The anticipation of satisfaction from attracting wildlife (Goddard et al. Citation2013) is a facilitator of behaviour. Simply carrying on with environmental activities one is already doing (DEFRA Citation2008) is also categorised under automatic motivation. Beliefs, such as having trust in environmental associations (Coisnon et al. Citation2019), having an environmental identity (Clayton Citation2019), a national identity in regard to native species (van Heezik et al. Citation2012, Citation2013) and an innate connection to nature (Clayton Citation2019) were also facilitators of behaviour.

Demographic factors

A high ethnicity-deprivation index (Coldwell and Evans Citation2017) was identified as a barrier to urban rewilding. The potential for cultural differences was highlighted in the literature and should be investigated in future research (Bauer and von Atzigen Citation2019). Ethnic minority groups in both the USA and European countries seem to prefer more managed and less natural landscapes compared to the white majority in those regions (Clayton Citation2019). The fact that indigenous or immigrant perspectives might differ from those of the dominant culture is a reminder that not everyone values unmanaged nature to the same extent. People from rural areas look more favourably on rewilding (Bauer and von Atzigen Citation2019

National characteristics, namely living in a country with high GDP or Environmental Performance index (Coisnon et al. Citation2019) were reliable indicators of rewilding behaviour, suggesting government influence. Demographic facilitators were high socio-economic status (Coldwell and Evans Citation2017), home ownership (DEFRA Citation2008, Citation2020, Coisnon et al. Citation2019) and education level (DEFRA Citation2008, Coisnon et al. Citation2019). Having a left-wing political outlook, being female (Coisnon et al. Citation2019), having a larger household size (with children) (Coisnon et al. Citation2019) and time at the property (Bauer and von Atzigen Citation2019) were also facilitators. Age is a facilitator. However, this seems to be context specific, as younger (Bauer and von Atzigen Citation2019) middle- (DEFRA Citation2008) and older-aged people (van Heezik et al. Citation2013) were all identified as looking more favourably on urban rewilding. Interestingly, having either a high or low household income could be a facilitator (DEFRA Citation2008). National characteristics (Coisnon et al. Citation2019), such as having a strong national identity associated with native species (van Heezik et al. Citation2012) can be a facilitator, as can owning a pet cat or dog (Beumer Citation2018), arguably an indicator of being an animal lover generally. Those already engaged with wildlife or nature organisations are more likely to engage in urban rewilding (Bauer and von Atzigen Citation2019).

Discussion

The aim of this scoping review was to understand the literature on intent-orientated pro-environmental behaviours, with a focus on urban rewilding, framed using the COM-B model of behaviour. The focus of this paper is on understanding urban-rewilding behaviour in private gardens, in relation to capability, opportunity and motivation factors.

The results show that all COM-B categories are important in understanding urban-rewilding behaviour in private gardens, although the number of factors related to having the opportunity and feeling motivated to carry out rewilding activities appear to be greater than those related to being capable of doing rewilding activity. Reflective motivation is the determinant with the greatest number of factors that could influence rewilding behaviour. Facilitators seem to be more numerous than barriers, although this might perhaps be explained by the reviewed papers generally being framed in a positive manner to promote conservation action.

The state of the literature

The literature on urban rewilding in relation to gardens is in its infancy with the first journal publication coming in 2009; only 18 papers have been published in peer-reviewed journals since (up to June 2021). No one journal is dedicated to the topic of urban rewilding with the 18 publications spread across 15 titles. Moreover, the literature does not show a consensus on how urban rewilding should be defined or what it should include and exclude in the context of gardens. Behaviour is context specific and therefore more research is needed to better understand how to encourage residents to make adaptations, or refrain from detrimental practices for wildlife and biodiversity. The aim of this scoping review is to support such work in London, the world’s first National Park City; no published research literature was found specific to this context. Therefore, the next stage of this body of work is to collect primary data from Londoners on urban-rewilding behaviour in relation to adaptations to private gardens, using the findings of this scoping review to feed into the study design. Understanding current rewilding behaviour in private gardens is an important first step before trying to positively influence this behaviour through practice and policy.

Implications for practice and policy

Successful practice interventions will need to impart the psychological skills needed for residents to be capable of participating in rewilding, such as an awareness of the biodiversity value of urban gardens, ideally instilling these skills from an early age. In practice it is often assumed that increasing knowledge will lead to behaviour change. While knowledge is a necessary condition underlying behaviour change, it is rarely enough to change behaviour on its own (Geiger et al. Citation2019). Projects should also tackle any physical barriers to rewilding by allowing residents to participate at their own pace.

Projects that address concerns about insufficient time, space, funding and plant availability limiting residents’ opportunity to take part in rewilding are likely to be effective, as are those that encourage buy-in at community level across a neighbourhood. Projects could benefit from highlighting the many motivations for rewilding, such as connecting with nature, educational value, creating a green retreat and helping the environment locally; in parallel, they would be advised to either mitigate or encourage greater tolerance of demotivators, such as disliked species, health and safety fears and undesirable aesthetics. Moreover, intervention projects should show how rewilding can be compatible with residents’ functional and aesthetic preferences in respect to their gardens, and offer a trustworthy source to allay fears about nature. Projects should be inclusive of residents with pets, and those of both high and low incomes, but advocate different approaches to rewilding to suit different budgets and aim to minimise pets’ impact on wildlife (Moxon Citation2021).

Policy interventions might need to focus on creating a greener public environment around residential areas to show the potential opportunities for local greening and rewilding; and modelling maintenance practices in public spaces that shift local or regional perceptions around the aesthetics of rewilding. At national level, a clear message from the government about the value of rewilding private gardens could well be influential. Policy that increases interaction with local wildlife may be beneficial in motivating residents to conduct urban rewilding in their own gardens. This is timely, as UK conservation policy is currently under scrutiny. Conservation charities the Wildlife Trusts, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) and the National Trust branded new government proposals for removing EU protections for nature, relaxing planning laws in ‘investment zones’ and reviewing nature-friendly farming schemes an ‘attack on nature’ (RSPB Citation2023). Such changes could undermine the UK Government’s pledge to restore 30% of land and sea for nature by 2030 through the goals in its Environmental Improvement Plan (Citation2023) (UK Gov). Meanwhile it raises concerns around existing policy, such as Biodiversity Net Gain, which allows for the gains to be made on a different site to the development (UK Parliament Citation2020).

Policy and practice interventions should be mindful of the demographic factors involved in urban rewilding of private gardens and the prevalence of these characteristics in the intervention location, in particular the ethnicity-deprivation index. It will perhaps be most productive to prioritise changing the behaviour of those more likely to be receptive to urban rewilding, before targeting harder to reach groups.

This scoping review focuses on understanding behaviour. It is acknowledged that understanding behaviour is the first step in bringing about change and that a further review of the mechanisms to influence change at a practice and policy level is required. The BCW lends itself to identifying and categorising such mechanisms, as it includes nine possible intervention functions (education, training, persuasion, incentivisation, coercion, enablement, modelling, environmental restructuring and restriction) and seven policy categories (environmental/social planning, communications/marketing, legislation, service provision, regulation, fiscal measures and guidelines) that have been shown to influence behaviour (Michie et al. Citation2023).

The evidence included within this review indicates that all intervention functions except coercion, and all policy categories could have a bearing on influencing urban rewilding behaviour in private gardens. These findings suggest a need for action across multiple areas to maximise impact. This might include raising awareness of urban rewilding benefits among the public and schools (van Heezik et al. Citation2012, Goddard et al. Citation2013); engaging more urban residents in citizen-science, community gardening and council-run wildlife gardening programmes (Mumaw and Bekessy Citation2017, Deguines et al. Citation2020); reviewing the target audience and framing of messaging from urban-rewilding campaigns (van Heezik et al. Citation2012, Coisnon et al. Citation2019); prohibiting chemical use in gardens (Canuel et al. Citation2014); and offering grants, tax incentives or product giveaways to support rewilding (DEFRA Citation2008, van der Jagt et al. Citation2017, Beumer Citation2018).

Implications for research

This paper has focused on the scoping review’s findings on understanding urban-rewilding behaviour in city gardens in relation to capability, opportunity and motivation factors. Given that research into urban rewilding in city gardens is in its infancy, the findings make an important contribution to an emerging field by offering a comprehensive review of existing literature from a cross-disciplinary perspective. This will form a basis for the work of other researchers investigating urban rewilding, across disciplines and internationally, advancing an important and timely topic.

The findings will also inform planned follow up research from the authors, detailed below, focused on urban rewilding in the gardens of London (London Metropolitan University Citation2022):

Phase 2: Mixed-methods research, including interviews and a quantitative survey, to understand the capability, opportunity and motivational factors influencing urban-rewilding behaviour in London.

Phase 3: Development of an intervention strategy to promote urban-rewilding behaviour, using the Behaviour Change Wheel framework.

Phase 4: Testing of the intervention strategy with before and after impact assessment.

It will be important to assess whether the scoping review’s findings are reflected by these more practical stages of the study, and indeed the London context. With London experiencing increasing development pressure coupled with decreasing vegetation in its residential gardens, facilitating behaviour change in the rewilding of private gardens is critical to tackling nationally declining biodiversity levels. Further, London’s status as a globally influential capital and pioneering commitments as a National Park City (Mayor of London Citation2023) will ensure the study has relevance to other cities worldwide.

These stages will also offer an opportunity to further explore the definition of urban rewilding and what related behaviour constitutes in the context of private gardens. This will be considered in Phase 2 by exploring the interview and survey participants’ definitions of urban rewilding, and any correlation to demographic factors, and with focus groups in Phase 3. In addition, further cross-disciplinary research to investigate and refine the definition of urban rewilding will be needed outside of this study.

Strengths and limitations of this paper

A core strength of the review is the use of multiple systematic searches to ensure specific and comprehensive scoping of the topic. Another strength is the use of the COM-B model to categorise the barriers and facilitators to urban-rewilding behaviour enabling future progression to intervention development using the BCW (Michie et al. Citation2014).

A limitation of the review is that only literature available in English was included, therefore unique insights from papers in other languages could have been missed. While this is not expected to significantly affect later phases of this study, which is focussed on a UK context, it is a gap that could be addressed by other researchers. In addition, while the screening stage was verified by two researchers, for feasibility the coding stage was divided among individual researchers. It is acknowledged that this could have resulted in bias and error at this stage. However, this was mitigated against by all researchers following the COM-B framework and the two lead researchers discussing any points of contention. A deliberate limitation of the paper is that it covers only understanding urban-rewilding behaviour, as this aspect enables substantial debate in isolation. However, a companion paper following the same format will address influencing urban-rewilding behaviour and the two papers can be read either separately or together, depending on the reader’s area(s) of interest.

Conclusion

The scoping review has revealed an important body of work in the nascent field of understanding urban-rewilding behaviour in private gardens. Applying the COM-B model of behaviour has enabled urban-rewilding behaviour to be understood in relation to capability, opportunity and motivation factors, with respect to both barriers and facilitators. This will have ongoing value in providing a foundation for further research in the field. Moreover, it will allow intervention designers to propose practice and policy for rewilding private gardens in cities that is based on an understanding of current behaviour.

Author contributions

SM and JW were co-investigators and wrote the final manuscript, with SM as lead author. JW designed the study. JW and AS conducted the searches. SM, JW and AS conducted the screening. SM, AS, JW and MS conducted the coding. SM and JW conducted the analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Geolocation information

This scoping review includes literature from across the world but aims to support the development of intervention strategies specifically in London, UK.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Siân Moxon

Siân Moxon is a senior lecturer in sustainable design at London Metropolitan University’s School of Art, Architecture and Design. Siân’s practice-led design research explores urban biodiversity within the Cities group at the Centre for Urban and Built Ecologies (CUBE). Siân leads the ‘environment challenge’ for London Met Lab and the Art, Architecture and Design Education Declares working group. Siân is an architect, author and founder of the award-winning Rewild My Street urban-rewilding campaign.

Justin Webb

Justin Webb is an Associate Professor of Public Health at London Metropolitan University. Justin has been working in the field of public health for over 15 years both as a practitioner and as a researcher. Justin’s former roles include working as the Director of the Centre for Workplace and Community Health at St Mary’s University and as a National Engagement Manager for Macmillan Cancer Support, leading on the charity’s healthy lifestyles programme. Justin’s research interest is in understanding and changing behaviour to improve health.

Alexandros Semertzi

Alexandros Semertzi is an Associate Lecturer in Psychology and Public Health at London Metropolitan University. Alexandros has been working as a Research Assistant since 2021 for 3 projects related to Public Health at London Metropolitan University. He is currently in his final year completing his PhD in Cognitive Neuroscience. Alexandros’s research interest is in attention, memory, and neuroscience of behaviour change for health improvement.

Mina Samangooei

Mina Samangooei is a practicing architect and academic, with research focusing on the role that food production in and on buildings plays for the future of cities. Mina’s PhD looked at behaviour theory in relation to people cultivating edible plants on buildings, which has been brought into practice through workshops and other live projects. Mina is a Senior Lecturer in Architecture and Technology at Oxford Brookes University, leading undergraduate and postgraduate modules and conducting research with collaborators.

References

- Aviva, 2022. Gardens being uprooted in favour of driveways and artificial grass, new research reveals. Available from: https://www.aviva.com/newsroom/news-releases/2022/07/gardens-being-uprooted-in-favour-of-driveways-and-artificial-grass-new-research-reveals/.

- Bamberg, S. and Rees, J., 2015. Environmental attitudes and behavior: measurement. International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences, 699–705. doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-097086-8.91066-3.

- Bauer, N. and von Atzigen, A., 2019. Understanding the factors shaping the attitudes towards wilderness and rewilding. Rewilding, 142–164. doi:10.1017/9781108560962.008.

- Bauer, N., Wallner, A., and Hunziker, M., 2009. The change of European landscapes: human-nature relationships, public attitudes towards rewilding, and the implications for landscape management in Switzerland. Journal of environmental management, 90 (9), 2910–2920. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.01.021.

- Beumer, C., 2018. Show me your garden and I will tell you how sustainable you are: Dutch citizens’ perspectives on conserving biodiversity and promoting a sustainable urban living environment through domestic gardening. Urban forestry & urban greening, 30, 260–279. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2017.09.010.

- Bonham, C., Williams, S., and Grimstead, I., 2019. Green spaces in residential gardens. Available from: https://datasciencecampus.ons.gov.uk/projects/green-spaces-in-residential-gardens/.

- Brondizio, E.S., et al., 2019. Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Available from: https://ipbes.net/global-assessment.

- Canuel, M., et al., 2014. Development of composite indices to measure the adoption of pro-environmental behaviours across Canadian provinces. PLoS ONE, 9 (7), e101569. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101569.

- Clayton, S., 2019. The psychology of rewilding. In: N. Pettorelli, S. Durant, and J. Du Toit, eds. Rewilding. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 182–200. doi:10.1017/9781108560962.010.

- Coisnon, T., Rousselière, D., and Rousselière, S., 2019. Information on biodiversity and environmental behaviors: a European study of individual and institutional drivers to adopt sustainable gardening practices. Social science research, 84, 102323. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2019.06.014.

- Coldwell, D.F. and Evans, K.L., 2017. Contrasting effects of visiting urban green-space and the countryside on biodiversity knowledge and conservation support. PLOS ONE, 12 (3), e0174376. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0174376.

- Costanza, R., et al., 1997. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature, 387 (6630), 253–260. doi:10.1038/387253a0.

- Deguines, N., et al., 2020. Assessing the emergence of pro-biodiversity practices in citizen scientists of a backyard butterfly survey. The science of the total environment, 716, 136842. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136842.

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 2008. A framework for pro-environmental behaviours. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/69277/pb13574-behaviours-report-080110.pdf.

- Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 2020. Biodiversity 2020: a strategy for England’s wildlife and ecosystem services. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/69446/pb13583-biodiversity-strategy-2020-111111.pdf.

- Geiger, S.M., Geiger, M., and Wilhelm, O., 2019. Environment-specific vs. general knowledge and their role in pro-environmental behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00718.

- Gill, S.E., et al., 2007. Adapting cities for climate change: the role of the green infrastructure. Built environment, 33 (1), 115–133. doi:10.2148/benv.33.1.115.

- Goddard, M.A., Dougill, A.J., and Benton, T.G., 2009. Scaling up from gardens: biodiversity conservation in urban environments. Trends in ecology & evolution, 25 (2), 90–98. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2009.07.016.

- Goddard, M.A., Dougill, A.J., and Benton, T.G., 2013. Why garden for wildlife? Social and ecological drivers, motivations and barriers for biodiversity management in residential landscapes. Ecological economics, 86, 258–273. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.07.016.

- Greater London Authority, 2018. London environment strategy. Available from: https://www.london.gov.uk/programmes-and-strategies/environment-and-climate-change/london-environment-strategy.

- Harrison, P.A., et al., 2014. Linkages between biodiversity attributes and ecosystem services: a systematic review. Ecosystem services, 9, 191–203. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.05.006.

- Hayhow, D.B., et al., 2016. State of nature 2016. Available from: https://www.rspb.org.uk/globalassets/downloads/documents/conservation-projects/state-of-nature/state-of-nature-uk-report-2016.pdf.

- Hayhow, D.B., et al. 2019. The State of Nature 2019. Available from: https://nbn.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/State-of-Nature-2019-UK-full-report.pdf

- Hill, M.J., et al., 2016. Urban ponds as an aquatic biodiversity resource in modified landscapes. Global change biology, 23 (3), 986–999. doi:10.1111/gcb.13401.

- Hobbs, S.J. and White, P.C.L., 2016. Achieving positive social outcomes through participatory urban wildlife conservation projects. Wildlife research, 42 (7), 607. doi:10.1071/wr14184.

- Houlden, V., Jani, A., and Hong, A., 2021. Is biodiversity of greenspace important for human health and wellbeing? A bibliometric analysis and systematic literature review. Urban forestry & urban greening, 66, 127385. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127385.

- James, K.L., Randall, N.P., and Haddaway, N.R., 2016. A methodology for systematic mapping in environmental sciences. Environmental evidence, 5 (1). doi:10.1186/s13750-016-0059-6.

- Jørgensen, D., 2015. Rethinking rewilding. Geoforum, 65, 482–488. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.11.016.

- Kadaverugu, A., Nageshwar Rao, C., and Viswanadh, G.K., 2021. Quantification of flood mitigation services by urban green spaces using InVEST model: a case study of Hyderabad city, India. Modeling earth systems and environment, 7 (1), 589–602. doi:10.1007/s40808-020-00937-0.

- Keith, D.A., et al., 2022. A function-based typology for Earth’s ecosystems. Nature, 610 (7932), 513–518. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05318-4.

- Kettel, E.F., et al., 2018. Breeding performance of an apex predator, the peregrine falcon, across urban and rural landscapes. Urban ecosystems, 22 (1), 117–125. doi:10.1007/s11252-018-0799-x.

- Kondo, M.C., et al., 2018. Urban green space and its impact on human health. International journal of environmental research and public health, 15 (3), 445. doi:10.3390/ijerph15030445.

- Lewis, M. and Townsend, M., 2014. ‘Ecological embeddedness’ and its public health implications: findings from an exploratory study. EcoHealth, 12 (2), 244–252. doi:10.1007/s10393-014-0987-y.

- Lewis, O., Home, R., and Kizos, T., 2018. Digging for the roots of urban gardening behaviours. Urban forestry & urban greening, 34, 105–113. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2018.06.012.

- London Metropolitan University, 2022. WildWays. Available from: https://www.londonmet.ac.uk/research/centres-groups-and-units/the-centre-for-urban-and-built-ecologies/research-projects-and-funding/wildways/.

- Loram, A., et al., 2007. Urban domestic gardens (X): the extent & structure of the resource in five major cities. Landscape ecology, 22 (4), 601–615. doi:10.1007/s10980-006-9051-9.

- Maller, C. and Farahani, L., 2018. Snakes in the city: understanding urban residents’ responses to greening interventions for biodiversity. Available from: https://apo.org.au/node/178346.

- Mayor of London, 2023. London National Park City. Available from: https://www.london.gov.uk//what-we-do/environment/parks-green-spaces-and-biodiversity/london-national-park-city.

- Michie, S., et al., 2023. The behaviour change wheel: a guide to designing interventions. Available from: http://www.behaviourchangewheel.com/.

- Michie, S., Atkins, L., and West, R., 2014. The behaviour change wheel: a guide to designing interventions. Great Britain: Silverback Publishing.

- Michie, S., van Stralen, M.M., and West, R., 2011. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation science, 6 (1). doi:10.1186/1748-5908-6-42.

- Mills, J.G., et al., 2017. Urban habitat restoration provides a human health benefit through microbiome rewilding: the microbiome rewilding hypothesis. Restoration ecology, 25 (6), 866–872. doi:10.1111/rec.12610.

- Moxon, S., 2021. Beauty and the beast: confronting contrasting perceptions of nature through design – siân moxon. Available from: https://journal.urbantranscripts.org/article/beauty-and-the-beast-confronting-contrasting-perceptions-of-nature-through-design-sian-moxon/.

- Mumaw, L. and Bekessy, S., 2017. Wildlife gardening for collaborative public–private biodiversity conservation. Australasian journal of environmental management, 24 (3), 242–260. doi:10.1080/14486563.2017.1309695.

- National Park City Foundation, 2022. Welcome to the National Park City movement. National Park City Foundation. Available from: https://www.nationalparkcity.org/.

- Nova, P., et al., 2020. Urban organic community gardening to promote environmental sustainability practices and increase fruit, vegetables and organic food consumption. Gaceta Sanitaria, 34 (1), 4–9. doi:10.1016/j.gaceta.2018.09.001.

- Office For National Statistics, 2020. Access to gardens and public green space in Great Britain - Office for National Statistics. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/environmentalaccounts/datasets/accesstogardensandpublicgreenspaceingreatbritain.

- Okvat, H.A. and Zautra, A.J., 2011. Community gardening: a parsimonious path to individual, community, and environmental resilience. American journal of community psychology, 47 (3–4), 374–387. doi:10.1007/s10464-010-9404-z.

- Owens, M. and Wolch, J., 2019. Rewilding cities. In: N. Pettorelli, S. Durant, and J. Du Toit, eds. Rewilding. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 280–302. doi:10.1017/9781108560962.014.

- Pettorelli, N., et al., 2019. Rewilding. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Prior, J. and Brady, E., 2017. Environmental aesthetics and rewilding. Environmental values, 26 (1), 31–51. doi:10.3197/096327117x14809634978519.

- Redondo-Bermúdez, M., et al., 2021. ‘Green barriers’ for air pollutant capture: leaf micromorphology as a mechanism to explain plants capacity to capture particulate matter. Environmental pollution, 288, 117809. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117809.

- RSPB, 2023. Attack on nature: the story so far. Available from: https://www.rspb.org.uk/our-work/rspb-news/rspb-news-stories/attack-on-nature-the-story-so-far/ [Accessed 3 May 2023].

- Samuelson, A.E., et al., 2018. Lower bumblebee colony reproductive success in agricultural compared with urban environments. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: biological sciences, 285 (1881), 20180807. doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.0807.

- Shwartz, A., et al., 2012. Urban biodiversity, city-dwellers and conservation: how does an outdoor activity day affect the human-nature relationship? PLoS ONE, 7 (6), e38642. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038642.

- Smith, C., 2011. London: Garden City? Available from: https://www.lbp.org.uk/downloads/Publications/HabitatInfo/LondonGardenCity.pdf.

- Smith, R.M., et al., 2005. Urban domestic gardens (V): relationships between landcover composition, housing and landscape. Landscape ecology, 20 (2), 235–253. doi:10.1007/s10980-004-3160-0.

- Stone, H., 2019. What is rewilding? (Extended version). Available from: https://rewildingnews.com/2019/01/24/what-is-rewilding-extended-version/.

- Sutherland, W.J., et al., eds., 2020. What works in conservation 2020. Open book publishers [Preprint]. doi:10.11647/obp.0191.

- Sweeney, O.F., et al., 2019. An Australian perspective on rewilding. Conservation biology, 33 (4), 812–820. doi:10.1111/cobi.13280.

- UK Government, 2023. Environmental improvement plan 2023. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/environmental-improvement-plan [Accessed 3 May 2023].

- UK Parliament, 2020. Environment bill 2019-21 (Bill 220). London: Crown copyright. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/environment-bill-2020.

- UN, 2018. 68% of the world population projected to live in urban areas by 2050, says UN | UN DESA | United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/2018-revision-of-world-urbanization-prospects.html.

- UN General Assembly, 2015. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development | Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Available from: https://sdgs.un.org/publications/transforming-our-world-2030-agenda-sustainable-development-17981.

- van der Jagt, A.P.N., et al., 2017. Cultivating nature-based solutions: the governance of communal urban gardens in the European Union. Environmental research, 159, 264–275. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2017.08.013.

- van Heezik, Y., et al., 2013. Garden size, householder knowledge, and socio-economic status influence plant and bird diversity at the scale of individual gardens. Ecosystems (New York, NY), 16 (8), 1442–1454. doi:10.1007/s10021-013-9694-8.

- van Heezik, Y.M., Dickinson, K.J.M., and Freeman, C., 2012. Closing the gap: communicating to change gardening practices in support of native biodiversity in urban private gardens. Ecology and society, 17 (1). doi:10.5751/es-04712-170134.

- Vergnes, A., Kerbiriou, C., and Clergeau, P., 2013. Ecological corridors also operate in an urban matrix: a test case with garden shrews. Urban ecosystems, 16 (3), 511–525. doi:10.1007/s11252-013-0289-0.

- Webb, J. and Moxon, S., 2021. A study protocol to understand urban rewilding behaviour in relation to adaptations to private gardens. Cities & health, 7 (2), 273–281. doi:10.1080/23748834.2021.1893047.

- Webster, E., Cameron, R.W.F., and Culham, A., 2017. Gardening in a changing climate. Available from: https://www.rhs.org.uk/science/gardening-in-a-changing-world/climate-change.

- Zhang, R., 2020. Cooling effect and control factors of common shrubs on the urban heat island effect in a southern city in China. Scientific reports 2020, 10 (1). doi:10.1038/s41598-020-74559-y.

- ZSL, 2022. Rewilding our cities. Available from: https://issuu.com/zoologicalsocietyoflondon/docs/zsl_rewilding_our_cities_report.