ABSTRACT

Views on gentrification and intersections with health and well-being were explored via semi-structured interviews with nineteen residents (≥60 years) in Porto (Portugal). Participants acknowledged that gentrification led to noticeable transformations in recreational areas, food/beverage establishments, housing, and commercial activities. Participants had contrasting views on gentrification-induced transformations. Some acknowledged positive contributions, while others expressed concerns about higher living costs, scarcity of affordable housing, weakening social cohesion, and aggravated vulnerability to mental health issues. Several participants claimed that the changes, mainly concerning commerce and recreation, seemed directed towards youth. Policymaking driving gentrification should consider older locals’ needs to promote better health.

Introduction

Gentrification, health and well-being

The urban environment plays a significant role in shaping health outcomes (Galea and Vlahov Citation2005). Thus, it is plausible that gentrification affects health through its transformative impact on the urban environment. Gentrification encompasses transformations in the neighborhood’s characteristics due to increased investment in the built environment. These changes attract people with more economic resources than long-time residents as the settings are shaped according to their preferences, such as high-end or modern stores, restaurants, public facilities, and housing (Gant Citation2016). Therefore, the neighborhood’s physical and social environment is modified. For example, infrastructure rehabilitation and the creation of new amenities alter the neighborhood’s physical environment. Moreover, the arrival of new people also changes the neighborhood composition by changing the level of education, income, age, or race, thus transforming the social environment.

Although some of the modifications derived from gentrification might seem advantageous, as they create new amenities and services, regenerate the local infrastructure, and increase the overall value of properties, unfavorable consequences can also arise. The increment in housing, services, and commerce prices originate economic and social pressure, potentially leading to displacement, disempowerment, food insecurity, and increased stress levels (Smith and Thorpe Citation2020). These changes can impact long-term residents by disrupting their networks, diminishing their access to resources, depriving them of amenities, and impeding access to housing due to excessive rents or eviction (Anguelovski et al. Citation2021). In addition, the uncertainty of potential and actual displacement can negatively influence people’s mental health (Tran et al. Citation2020).

Furthermore, the new amenities do not necessarily match the preferences of long-term residents as gentrification changes the characteristics of local stores. This can disrupt former residents’ emotional bonds and attachments as well as demand a higher purchasing power to benefit from these new amenities (Zukin et al. Citation2009). As the neighborhood changes, long-term residents may feel a distressing sense of dispossession and loss of place, which may also be detrimental to their health and well-being (Anguelovski et al. Citation2020, Citation2021, Sánchez-Ledesma et al. Citation2020, Versey Citation2022). Previous studies have also suggested that residents of gentrifying areas are at increased risk of substance abuse and financial insecurity (Anguelovski et al. Citation2021). Moreover, these gentrifying areas become more policed, sometimes in intrusive ways (Versey Citation2022). Consequently, gentrification can affect health and well-being in several different ways.

Aging and health in gentrifying territories

The aging of urban populations brings up new challenges to provide environments where older adults can thrive and support their full involvement and inclusion. Most older adults live in urban spaces. Over 500 million people aged 65 years or over reside in cities, accounting for 58% of all older people (HelpAge International Citation2016). However, there are still few studies analyzing how gentrification affects older adults, and their perspectives about how gentrification affects their health and other aspects of their lives have been largely ignored in many previous studies (Buffel and Phillipson Citation2019).

The health impact of gentrification is inequitably distributed, with some groups being more vulnerable to the detrimental effects of gentrification than others (Hwang and Ding Citation2020). The literature suggests that older adults have a specific vulnerability. This age group may be particularly affected since many have spent much of their adult lives living in the same neighborhood, and their daily lives are usually circumscribed to their immediate neighborhood due to retirement and/or reduced mobility (Torres Citation2020). Older adults living in a gentrified area might be affected if their networks become dispersed and, therefore, lose their social capital that would have otherwise been a key source of psychological resilience and restoration for mental health. For instance, one study conducted in the United States observed that older adults living in gentrified areas had greater risks of anxiety and depression compared to those living in non-gentrified areas (Smith et al. Citation2018). Thus, gentrification might be an intense experience for older adults since their daily lives can be constrained to their nearest neighborhood, and consequently, they might experience a lack of neighborhood support and feelings of indirect displacement (Torres Citation2020). Other studies have also reported that older adults living in gentrified areas are more likely to feel place alienation (Diaz-Parra and Jover Citation2021), social isolation (López et al. Citation2022), rejection and exclusion (Buffel and Phillipson Citation2019).

Study setting, aims, and the value of qualitative approaches

Recently, several Spanish, including Barcelona (Cocola-Gant and Lopez-Gay Citation2020) and Madrid (Ardura Urquiaga et al., Citation2020), and Portuguese cities, such as Lisbon (Cocola-Gant and Gago Citation2019; Mendes, Citation2021) and Porto (Carvalho et al. Citation2019, Chamusca et al. Citation2019), have been identified as gentrification hotspots, with tourism, real estate financialization, and state-led actions playing significant roles in gentrification processes. Gentrification in these cities is transnational in the sense that it links the local scale to global consumption, mobilities, and capital, thus widening the potential profits of real estate ownership and paving the way for urban changes aimed at attracting affluent city users. Indeed, a body of literature argues that the connection of local real estate markets with transnational fluxes of both capital and social groups with high purchasing power and mobile lifestyle aspirations, which is facilitated by the role of technological platforms (namely Airbnb and similar ones) and by local and national governments seeking to attract investment in the 2008 crisis aftermath, is widening rent gaps (Smith Citation1979) in cities across the world, thus fuelling gentrification processes (Sigler and Wachsmuth Citation2016, Citation2020, Cocola-Gant and Lopez-Gay Citation2020, Hayes and Zaban Citation2020).

Porto had a population of 231,800 inhabitants in 2021. There are 60,812 people 65 years or older, and for every young person, there are 2.3 older adults (INE Citation2022). These demographic data show that Porto is an urban setting with a prominent aging population. In recent years, Porto has been undergoing deep and fast-paced changes due to gentrification processes, especially in the city center. These include a rapid increase in tourism, the burgeoning growth of short-term rentals, functional changes of buildings, urban rehabilitation, and soaring housing costs (Fernandes et al. Citation2018, Carvalho et al. Citation2019). However, the topic of how the social and physical changes induced by gentrification in Porto have affected the health of Porto inhabitants, including older adults, is understudied. Studying the case of Porto can shed light on how gentrification can impact the health and well-being of older adults. In addition, examining residents’ opinions on gentrification may help understand which neighborhood-related factors matter most in shaping health outcomes among older adults.

Against this background, this study aims to understand how older people living in Porto perceive gentrification and how it relates to their health and well-being. Qualitative methods were chosen as the preferred technique for achieving our goals. Qualitative methods can provide rich, nuanced, and contextualized accounts of experiences and views, making them advantageous to study how gentrification may affect the health of older adults while including their point of view. Indeed, there have been recent calls in the literature for greater use of qualitative methods to study the relationship between gentrification and health (Cole Citation2020). Qualitative interviews are well-suited to capture, with depth, a variety of data, including, importantly for us here, representations, behavior, imagined realities, cultural ideas, and emotional states (Lamont and Swidler Citation2014). They have been previously used to study the relationship between gentrification and health (Anguelovski et al. Citation2020, Citation2021, Binet et al. Citation2021, Versey Citation2022).

Methods

We conducted interviews with participants of the EPIPorto project (Ramos et al. Citation2004). This population-based prospective cohort study of Portuguese adults was drawn to evaluate the determinants of health in the adult population residing in Porto. Two researchers (CJS and JPS) conducted semi-structured interviews with EIPorto participants in the Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto. Given our work’s qualitative nature, statistical representativeness or generalization were not considered priorities (Curtis et al. Citation2000).

Qualitative sampling is seldom concerned with attaining representativeness. There are many specifically qualitative sampling strategies, and their general goal is not to warrant representativeness but to select individuals in a way that enables the gathering of rich information concerning the research questions and goals of the study (Patton Citation1990, Green and Thorogood Citation2004). Qualitative research is concerned with exploring and understanding meaning and providing a detailed and nuanced picture of a particular phenomenon, not with revealing or measuring general patterns.

On the other hand, generalization is not consensual among qualitative researchers: some argue that generalization is unimportant in qualitative studies (Carminati Citation2018), while others claim that it remains a relevant concern (Mayring Citation2007). What is largely consensual is that, because qualitative research is rarely, if ever, supported by large representative samples, generalization has mostly a theoretical sense and not the statistical sense that it has in quantitative research (Curtis et al. Citation2000, Carminati Citation2018). For example, a well-designed qualitative case study may falsify a theory – this is generalization, in the sense of making general claims from a small number of cases (Flyvbjerg Citation2006). Other qualitative studies seek generalization by building theories from their results, which is the goal of the grounded theory approach (Glaser and Strauss Citation1967). Many qualitative studies, however, have more modest ambitions concerning generalization, and this is how we see ours: we don’t seek generalization, we hope our conclusions may inform other studies about this under-researched issue and that it may be a small contribution to our broader understanding of this issue through critical assessment and comparison of its results by researchers working on the same topic in different settings and/or using different methods. We think this is a valid goal for qualitative research and certainly one shared by many qualitative studies.

Therefore, we built an intentional sample to study, in-depth, the perspectives of persons with different socio-economic statuses and different house tenure situations to provide a broader and simultaneously richer picture of how gentrification impacts the well-being and health of older adults. We followed the strategy of ‘maximum variation sample’ (Patton Citation1990), an intentional qualitative sampling strategy to identify the central aspects of a given phenomenon across the rich information gathered from diverse individual cases. A large sample size does not have the same importance for qualitative research as it does for quantitative research: interview study samples generally comprise a few tens of interviewees. The sample size is contextual in qualitative research: it must be judged according to each study’s intent. Depending on its purpose, a sample of n = 1 might be adequate for an interview study (Green and Thorogood Citation2004, Boddy Citation2016). Thus, we believe we have interviewed enough people to provide an insightful and in-depth report about how gentrification may affect older adults’ health and well-being.

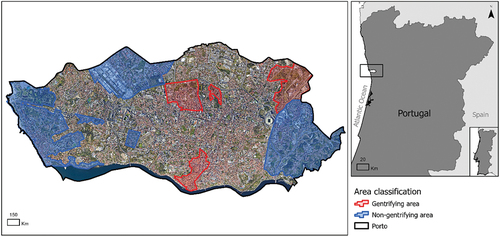

We selected individuals with distinct socio-demographic features, namely, sex (female, male), education (primary, secondary, tertiary), housing tenure (homeowner, tenant), and area of residence (gentrifying and non-gentrifying), to understand how diverse people experience gentrification, health, and well-being. However, this strategy could not capture displacement and excluded people forced out of gentrifying neighborhoods in Porto who could no longer remain in the city. These individuals frequently withdraw from longitudinal cohort studies, resulting in losses to follow-up. In the absence of neighbourhood-level data on income and housing prices, the classification of the area of residence as gentrifying or non-gentrifying was done using the Municipal Property Tax (IMI) values available on the Portuguese Finance Portal over the last 16 years. We compared the IMI values from 2015-2022 (during which the transnational gentrification process intensified in several Porto neighborhoods) with 2006-2009 (when gentrification was not notorious yet (Smith and Thorpe Citation2020)). We classified an area as gentrifying if there was at least a 20% increase in IMI between these two periods and if the 2006-2009 value was not higher than the city’s average. We considered an area as non-gentrifying if there was at most a 10% increase at most in the same tax. Areas in which none of these criteria were verified were not classified, as observed in .

The final classification was in line with what was expected by the researchers, according to their perception of the city.

Prospective participants were invited by telephone by a team member (ET). Nineteen interviews were carried out from the 2nd of September to the 29th of November 2022. The duration of the interviews was between 37 minutes and 17 seconds and 1 hour, 34 minutes and 4 seconds (with an average of 1 hour, 3 minutes, and 47 seconds). The questions included the perception of the gentrification phenomena in Porto and its impacts. We began by asking the following questions: ‘If you think about the last ten years, what are the most important changes you have seen in Porto?’ and ‘In which areas of the city do you notice those changes the most?’. Moreover, we explored the perception of the effect of gentrification on health and well-being by asking in each issue the participant mentioned how those changes influenced their health. We clearly defined what we meant with the term ‘health’ by telling participants at the beginning of the interview that it referred not just to the absence of illness, but to a state of physical, mental, and emotional well-being.

Our guide also included questions about specific topics of interest related to gentrification that were introduced when the interviewee did not address them spontaneously. These topics included changes concerning the following aspects: people, the conservation status of the buildings, public spaces (e.g. public gardens, public squares, parks), types of stores and services, community life and the social ties between people, spaces where people usually meet and engage in convivial practices, and safety in the city. Questions not foreseen in the script were asked to delve deeper into the answers provided, request examples, and explore new aspects raised by the interviewee. Interviews were transcribed from the audio recordings, assuring anonymization of identifying information using pseudonyms, and were coded using the NVivo software (release 1.7). An inductive thematic analysis was conducted by coding from the data, and clustering the codes into themes, following the Braun and Clarke approach (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). A single researcher (CRJ) performed the analysis using annotations to adopt a reflexive approach and maintain coding consistency. These annotations were then reviewed and discussed with a second researcher (JPS). Additionally, the final themes were revised with the rest of the team.

Ethical considerations

The Ethics Committee of the Instituto de Saúde Pública da Universidade do Porto granted ethical approval (CE22210). Written informed consent was obtained from the participants. The interviews were audio recorded and destroyed after their transcription and anonymization were completed. Pseudonyms were used in the interview quotes.

Results

presents the participants’ characteristics. Older adults were between 62 and 88 years old (with an average age of 74.6 years). Among the 19 interviewed, 12 (63.2%) were female, 10 (52.6%) lived in gentrified areas, and 12 (63.2%) were homeowners. The majority of older adults had primary education, 8 (42.1%), followed by 7 (36.8%) older adults with an upper secondary education and 4 (21.1%) with tertiary education.

Table 1. Summary of the socio-demographic characteristics of the nineteen participants.

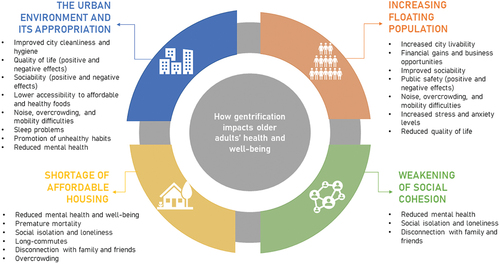

Participants discussed the most important changes they noticed in Porto in the last ten years and reflected on how those changes could influence health and well-being. Although not all the discussed changes were about gentrification, others were, and sometimes they were spontaneously mentioned by the interviewees. This section will focus on the changes that could be linked to gentrification. These were assigned to four distinct themes: the urban environment and its appropriation, the increase of the city’s floating population, the shortage of affordable housing, and the weakening of social cohesion. We will also explore the interviewees’ ideas about how these changes shape health and well-being in the city. summarizes the implications for health and well-being associated with each theme.

Figure 2. Overview of the themes identified and the effects of gentrification on older adults’ health and well-being.

The urban environment and its appropriation

A theme that was deeply discussed was the transformation of the city’s physical space either by renovating the areas with the creation or renovation of leisure spaces and buildings or by changes related to commerce, including the opening of multiple new food and beverage outlets. According to most residents, these modifications caused an increase in the cost of living and changed how people used the city’s facilities. However, some also said that the city’s changes might enhance opportunities for well-being.

One undisputed observation among participants was the changes in food and beverage outlets. They reported a higher number of these all over Porto, but especially in the city center, with many renewed spaces imbued with a more modern atmosphere. Although the city presently offers diverse cuisines, this diversity does not reflect older people’s preferences. Usually, according to participants, these new places are targeted at tourists and are overpriced.

But people more or less my age, or even a bit younger, they notice ‘that’. They notice ‘that’. The value, because prices have increased. And they don’t even like the … they don’t even like some of the food. Like those hamburgers, everything is very pretty, isn’t it? (Female, 62 years, secondary education. Homeowner in a non-gentrified area)

Even some interviewees claim there is inequality in access for older people in terms of cost and challenges related to mobility limitations. Even though they might not be directed to their age group, an interviewee mentioned that these new outlets might give youth additional opportunities for meeting and having fun. The stated negative aspects of these places were the disturbance to the locals due to the noise and overcrowding and how the escalating prices could affect their quality of life.

I try to avoid the downtown area, I only get there when I need to, because it’s a lot of confusion to be there in the middle of all that, isn’t it? (Male, 71 years, secondary education. Living in a rented house in a gentrified area)

Moreover, most participants noticed more ‘third places’ to meet people in the city. Third places are usually public or commercial spaces outside of the home and the workplace, such as parks or cafes, where people have the option to spend time with each other or on their own. These spaces promote social interaction and allow people to bond and strengthen their social networks (Oldenburg and Brissett Citation1982). Our participants describe these new places, mostly those downtown, which include new coffee shops with terraces, bars, and nightclubs. However, older people do not use these spaces. Most argue younger people are the ones who widely attend them, while older adults prefer green spaces to get together with people. Another participant mentioned that having new establishments in the city brought new opportunities for people to have fun. However, it could also promote unhealthy habits, such as binge drinking. On the one hand, older adults consider that having new places to be sociable is relevant for learning, discussing, and enhancing friendships. On the other hand, they acknowledge that some of these new places can be detrimental to health as they can encourage the consumption of alcohol and unhealthy foods, besides sleep deprivation for those who use them.

One participant observed that there should be more locations for people to be physically active while socializing, as sitting in a coffee shop will not do the job. Nevertheless, it was also mentioned that these changes contributed to the disappearance of traditional commerce, which could have a negative mental effect on people who enjoyed attending those places.

But how does it [changes in commerce] affect [health]?

In a mental way. A younger person sees it as normal, but we, as elders with life experience and that went through the old things and now it’s different. (Male, 72 years, primary education. Living in a rented house in a gentrified area)

Residents commented on the closure of traditional commerce, such as the retail sale of ready-to-wear clothes, groceries, jewellery, clothing, footwear, and headgear stores. In the place of those retailers, they state a change in the type of open shops. Usually, restaurants, stores devoted to tourism, barbershops, or laundries are prominently the substitutes, especially downtown.

In turn, emblematic stores of the city disappear and are transformed or renovated to places residents do not use, either for considering the replacement of lower quality or irrelevant to residents’ interests.

It saddens me, because there were stores that where emblematic in the city, and I’m thinking of the store where the tickets to Lello bookstore [a major tourist attraction in Porto] are sold, because it was a fantastic department store where I liked to go often, and now it’s nothing, it’s a place where tickets are sold. (Female, 70 years, tertiary education. Living in a rented house in a gentrified area)

These transformations in Porto’s commerce led one interviewee to say that it was more difficult to find particular goods. However, people stated that they found options to fulfil their needs in their daily lives, but those changes could be an obstacle for older people with mobility difficulties.

Yes, I see that older people hum … it’s harder for them to go to the supermarket, I often don’t go myself. ‘Oh, I must go to the supermarket!’ I won’t go. It’s farther away, I don’t feel like going. While when there was the grocery shop just around the corner, I’d say: ‘I’m going there to get some eggs’, and I went there in a minute. (Female, 70 years, tertiary education. Living in a rented house in a gentrified area).

It is essential to notice that, according to several participants, traditional commerce was not overrun by the new spaces directed to leisure and tourism. Instead, the latter occupied the void that the former left when it waned due to the emergence of large commercial spaces, mainly in the suburbs.

Furthermore, most participants preferred traditional commerce, justifying this preference with the attention and care put into the relationship with the client. They reported that this branch’s transformation affected mainly their mental state.

Older people also expressed that attending conventional stores allowed them to be more active by walking to the shops due to the closeness of their residence, and it also gave rise to sociability moments with friends.

I think it affects [health] somewhat, because, I mean … people would go to the street, they took the opportunity to walk, isn’t it? Because they used to walk from store to store. And, besides taking the opportunity to walk, they’d buy their stuff, they were … I mean … I don’t know. I think they were more entertained. Usually, friends would go [shopping] together. And after that they would have tea or a snack at a pastry store. (Female, 72 years, secondary education. Homeowner in a gentrified area)

Furthermore, the closure of traditional commerce made some streets more deserted, especially at night, leading to feelings of insecurity.

Another thoroughly discussed topic was the renovation or the new construction of buildings in the city. Participants believed that building renovation was mostly associated with the growth of short-term rentals, although they discussed situations where it was meant for long-term housing. New buildings were primarily identified as hotels and residential buildings. Despite emphasizing that the changes are more pronounced downtown, the participants saw it throughout the city, especially the emergence of hotels and local accommodations. People were satisfied with these renovations as they recognized Porto was degraded, making them low-spirited. They claim these alterations beautified the city, giving it a new life.

One obvious thing is the rehabilitation of old houses all around Porto, mainly for short- term rentals, which is infernal. Nowadays I’m aware that this is the trend, which has a very big advantage, which is the restructuring of the houses. (Male, 63 years, tertiary education. Living in a rented house in a non-gentrified area).

These new hosting locations are described as a source of income for people who own them and for merchants, along with generating job prospects. They also acknowledge that the changes in the colleges’ area are noticeably related to student accommodation, and one participant mentioned the appearance of new spaces for co-working. Interviewees stated that the housing conditions and quality have been improved, offering a higher quality of life. However, this is also one reason for the rising cost of housing, according to the interviewees.

If people are going to invest in building renewal, they must get the profit from somewhere, they are not going to put rents … unless its supported rents, isn’t it? (Female, 81 years, secondary education. Living in a rented house in a non-gentrified area)

Although people deem these modifications in construction favorable and advantageous to the city, they also criticize that it takes away green spaces, thus removing meeting spaces and creating concrete cities.

Participants claim that the changes in the city increased the cost of living for residents, notably in housing and commerce, more pronouncedly in tourist areas. Thus, some consequences described were that due to price increases, some people have more difficulty having a balanced diet and could lead to people meeting less often. Older women, mainly from gentrified areas, referred that the price increase would aggravate the low purchasing power, especially of older adults, since they are not working anymore and would not have a monthly income, for example, to pay for medication and food. As mentioned, the increase in the cost of living makes people incapable of buying what they need or going out for dinner as much as they would like to; in other words, they are just surviving on what they have.

The cost of living increases, but the money that people get by the end of the month is the same, this concerning those … even retired people, and people receiving the minimum wage, the minimum wage increases x every year, isn’t it? But it is not enough. (Female, 78 years, tertiary education. Homeowner in a gentrified area)

One participant said having policies to solve this problem would be beneficial. Another participant suggested that people should be consulted before changes occur to actively participate in the city’s transformations.

Increasing floating population

Transnational gentrification processes are linked to a local increase of a transnational transient population in a permanent state of movement, comprised mainly of tourists, students, and temporary migrants (Cocola-Gant Citation2018, Carvalho et al. Citation2019) – a floating population. Participants observed an increase in the number of these people in the city. People living in a non-gentrified area noticed a higher number of tourists downtown. In contrast, people living in a gentrified area, except for one interviewee, claimed that the increment of tourists was all around Porto. Participants said that having more tourism in the city contributed to discovering new cultures and realities, which one participant admitted positively affected her as she enjoyed meeting people.

I think that it’s always good for the country to be open to people for abroad. Other cultures, other people … (Female, 69 years, tertiary education. Homeowner in a non-gentrified area)

Another beneficial effect was the opening of more hotels, bars, and coffee shops that provided additional job opportunities. One interviewee said that the interest shown by visitors also arouses residents to get to know their city. Other opinions suggest that having more people in the city could promote being sociable and that the city had a new life. One participant underlined the importance of this since Porto inhabitants were decreasing in number because of having an older population. Everyone agreed that tourists added economic value by generating new commerce prospects. Lastly, according to the participants, the increase in local accommodation could be a great form of additional net income. One of the participants rented part of the home to tourists, which was described as sometimes stressful because it was added work and constrained home behavior, but valuable to gain some more money to face growing expenses with medicines.

I also have a short term rental […] my husband is very sick, so he has a lot of problems. […] So, to help us, because it’s a fortune just with the pharmacy [expenses], isn’t it? […] To me it’s an advantage, because I can live better, isn’t it? (Female, 77 years, secondary education. Homeowner in a gentrified area)

Nevertheless, it was believed that tourism also caused the rising cost of living and increased hustle and noise, which could influence people psychologically by increasing stress and anxiety levels. In addition, people said visitors would occupy more of residents’ space, who could lose their routines and stop doing what they enjoy, for example, being unable to have a table on a coffee terrace due to overcrowding. Moreover, it was mentioned that the arrival of more tourists could make less housing available.

Well, the tourists, the negative influence of the tourists is also that they made everything more expensive. That is a very large negative, you may sometimes want … well, you want a bit of peace and quiet and you don’t have it, it’s the noise, it’s like that, you want a place in the terrace and you won’t find it, this is Porto’s negative. (Female, 78 years, tertiary education. Homeowner in a gentrified area)

Participants also talked about the higher number of students in the city, and few people commented on the arrival of more immigrants; however, participants did not specify who these immigrants were, in other words, if they were temporary or permanent, affluent or deprived. Even though some participants did not describe how these new people in the city influence life in Porto, several noted that they could bother residents for the nightlife’s hustle.

Some people complain a lot about the noise by night […]. During the night, some people … it depends on the neighbourhood, in some neighborhoods people complain about the noise. And our buildings are generally old, they are not prepared for the noise, isn’t it? (Female, 78 years, tertiary education. Homeowner in a gentrified area)

However, two participants highlighted the benefits of having more students: one stated that it helped develop transportation, housing, and retail; the other one said that students help the community with voluntary activities, such as keeping company to those who are alone.

People also mentioned having difficulty circulating through the city as it is overcrowded. Although there was an improvement in the city’s space and establishments, some secondary education homeowners claimed that there were some constraints in circulating through urban space. These constraints were derived from the higher influx of people, which augmented the city’s confusion. One older adult revealed that he felt uncomfortable due to experiencing greater difficulty in walking on the streets due to crowding, for instance, in busier commerce streets.

I go to a main street and, sometimes, [in] Santa Catarina [street], I have trouble moving around. [There’s] a lot of people, years ago it wasn’t like that. (Male, 76 years, secondary education. Homeowner in a non-gentrified area)

This meant some people would abstain from visiting places or enjoying their weekend walks. Furthermore, it was said that the increase in the number of people in the city would be detrimental to those who prefer a quieter city. However, there was also a contrasting opinion from another participant who thought it was not harmful to the city being busier. Participants also noted that, despite having developments in Porto, they could not take advantage of these improvements for the reasons mentioned above, which generally led to a diminished quality of life.

As to security, there was no consensus. Some people affirmed that the city was more insecure during night-time because of problems related to the nightlife industry, primarily downtown, affecting mainly young people. Others also commented that having more people in the city could lead to more robberies, with some believing that the most targeted people would be tourists. Nevertheless, there was also a contrary opinion that the city was safer, mainly in the tourist areas.

Shortage of affordable housing

The housing crisis due to lack of affordability was a salient topic in the interviewees’ discourses. People stated that nowadays there is difficulty in living in Porto. Some older people said that the changes in the city would increase vulnerability to poor mental health and well-being.

During the interviews, it was mentioned that housing is offered in the city, but not at fair prices. Participants claimed that the housing cost had an exponential increase, which some attributed to a lack of price regulation and greater demand. Consequently, only wealthier people and homeowners can remain in Porto, leaving younger people particularly out of the city as they look for slightly more affordable housing on its outskirts. Another consequence pointed out by an interviewee was that younger people are deprived of getting their independence and starting their families as they do not have enough financial means to leave their parents’ house.

It is [related to health], because one becomes disheartened, one becomes disheartened. For example, my son becomes disheartened, because it’s like my son says: ‘I’m old enough to live, not to live with my parents’. Therefore, for someone … it’s a bit frustrating. Because, they begin a relationship, they want to marry, how can they?” (Female, 71 years, primary education. Homeowner in a gentrified area)

In addition, one interviewee said the increase in housing prices could put too much pressure on older adults since their children cannot move out of their homes, which could mean an increase in mental health problems. Curiously, people renting did not testify to the rise in house pricing.

There are a lot of people, a lot of sons that were forced to leave their house and return to their parents, I know … and then it begins to saturate right? They begin to saturate, because, in the case of the family I know, they were three in the house, then another three arrived, the daughter and two girls, and there was that … in the beginning, everything was ok, but then one becomes getting nervous for nothing, right? (Female, 74 years, primary education. Howeowner in a non-gentrified area)

Participants expressed dissatisfaction regarding people being evicted from their houses. Interviewees suggested that creating short-term rentals, like those listed in AirBnB, was the main driver of the evictions. Participants said this phenomenon would be more distressing for older people, especially those with reduced financial means. This would cause disorientation, a sense of losing their place, loss of local social ties, and disruption in their friendship circle. Most people pointed out that the effects on health and well-being would be mainly psychological, being that one participant referred it could contribute to developing depression, and some even said it could even lead to death due to sadness, and displaced people would yearn for the days they lived in their original place.

Look, I’m going to tell you a story. A while ago, I was having breakfast in a patisserie around. And then there was a very old weeping lady. What had happened? She had been evicted. She didn’t know where she was going, she didn’t know where she was going to live, because the house where she was, which was rented, suddenly, the owner decided to move her out to make a sort-term rental. And she was desperate. (Male, 63 years, tertiary education. Living in a rented house in a non-gentrified area)

Older adults were widely aware of the eviction problems. Participants criticized removing people from their houses, particularly those with lower incomes. Although it was said that they might have moved to homes with better housing conditions, the loss of their local friends and separation from family members could cause people to feel isolated and lacking support. The loss of the affective part attached to their previous neighborhood where they lived most of their lives could make people miss their place and be constantly upset by the move.

For this reason, participants said it would be more difficult for older adults than younger generations to better adapt to the change. Some older adults even revealed that they knew of some cases where the evicted person died after a while due to moving out.

I think there are people who … who, in these situations – and I have known some cases – practically no longer have an interest in existing.

Situations of leaving the place where they were?

Situations of leaving the place they were. I mean, that was their cradle. They lost their cradle … they stopped being what they were. Besides sadness, right? I knew some cases of this nature. People even died because they ended up having … they stopped having pleasure in life. (Male, 67years, secondary education. Homeowner in a gentrified area)

Therefore, one participant said it would be essential to have better planning when initiating urban redevelopment and to manage the process with more kindness and humanity toward people.

Weakening of social cohesion

Interviewees claimed that gentrification in Porto caused a change in the dynamics of residents’ social ties. The modification of interpersonal relations due to being further away from the city center was very present in the inhabitants’ discourse, especially when discussing family ties. It was mentioned that living on the outskirts heavily affected the daily lives of families as their routines would be somewhat stressful during the weekdays, mainly related to the time-consuming commutes. Consequently, people said it could build up tension within the family and affect their mental health.

Yes, because then there is a lot more nervousness, there’s a lot more… schedules and everything. Maybe they have to get up earlier in the morning, ‘come on’, there’s a friction that begins there, and that originates, a lot of times, a bad feeling, and … because the person is simply no longer in her comfort zone, and she has to adapt. And sometimes … some people’s age won’t allow that, while others don’t … others had friends here and there, and then… (Female, 62 years, secondary education. Homeowner in a non-gentrified area)

Another factor stated as weakening family relationships was that parents would be physically distant from their children and grandchildren, which over time, people would start to drift away. One interviewee confided that it could bring some discomfort for the children and the parents as they cannot move out of the parent’s house, and each part should have its own space. For this particular interviewee, it was a growing preoccupation since there was uncertainty about what would happen to her son’s accommodation when she passed away, as the house they were living in was rented.

Because if he had his little spot, he would feel better, and we would too. And to know that he is there, he has his house, he could be there … I know he would be well [Interviewer: Exactly]. Now, one day I’ll go away and I don’t know how he’ll stay. It’s very complicated. (Female, 76 years, primary education. Living in a rented house in a gentrified area)

Nevertheless, a few people felt that gentrification has little or no effect on people’s family relationships.

Regarding community ties, few people mentioned changes in relationships due to gentrification. Once again, some people said that displacement could lead to losing previous community ties. It was noticed that people could become more distant. Even the people who gave other reasons for changes in community ties rather than things related to gentrification added that it could affect people’s mental health for not having, for example, someone to whom they could talk.

Overall, older people had difficulties explicitly identifying how the changes affected their health. Therefore, even though they pointed put many transformations with potential health implications, it was not surprising that some older people felt that there was no link between gentrification and health and well-being. Two other participants said that the influence of gentrification on older people’s health would depend on the person’s personality and preferences, meaning that some could benefit and others not.

Discussion

Our study reveals older persons’ complex relationships with gentrification processes and between these and their health. Although it was not common for participants to consider that the ongoing changes in Porto affected their health, they often described them in a way that might pose challenges to people living in the city, namely older people, and may impact their health. In order to understand participants’ difficulty in describing precisely how gentrification might impact health, several issues should be considered. Firstly, the nature of gentrification itself, a complex phenomenon that might have multiple origins and affect different groups in diverse ways (Cole et al. Citation2021). Secondly, given its complexity, it might affect health in contradictory ways, bringing benefits and harm simultaneously (Schnake-Mahl et al. Citation2020). Finally, gentrification is a process that gradually unfolds over time at varying pace, and, given the long pre-clinical phase of some health outcomes, at least some of its health effects will take time to reveal themselves (Tulier et al. Citation2019).

Gentrification may benefit some long-time residents who manage to stay (Brummet and Reed Citation2019, Sýkora et al. Citation2022). Our interviewees identified some benefits in how Porto has been changing, namely its physical environment and how people relate to it. Living in a renewed and well-maintained city, where life on the streets and visitors fuel the local economy, was seen as beneficial. One interviewee has found a way to get a complementary income from Airbnb, one of the mechanisms facilitating transnational gentrification across the city (Wachsmuth and Weisler Citation2018, Chamusca et al. Citation2019, Cocola-Gant and Gago Citation2019), although facing new nuisances in everyday life. However, gentrification also poses challenges to the aging inhabitants of Porto, with possible negative repercussions on their health.

Gentrification processes often have an age dimension, as urban development often targets younger affluent social groups (Moos Citation2016, Moos et al. Citation2019). This dimension seems to be at play in Porto, as people claim that the city is changing in ways that provide more places and opportunities for younger people to gather and enjoy themselves, but not older people. Moos has argued that gentrification processes are often simultaneous with a different but gentrification-related process of ‘youthification’ (Moos Citation2016). This brings a double burden to aging residents of gentrifying neighborhoods. First, as housing costs and commerce prices increase, they may find an economic strain, as older people often have limited income and few opportunities to expand it (Smith et al. Citation2018). This might be especially pressing in Porto and other Portuguese cities where the pace and scope of gentrification are notorious, as income from retirement pensions is generally low in the country (OECD Citation2019), and most older adults struggle with multiple health issues (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Citation2019). This means that a substantial amount of their income must be spent on treatments and medicines, but rising housing costs and other economic pressures may force difficult decisions that ultimately harm both their mental and physical health.

Second, local commerce and amenities may change in a way that caters to the needs and preferences of younger people, potentially excluding older adults (Burns et al. Citation2012, Buffel and Phillipson Citation2019). Previous research has shown that gentrifying commerce may exclude older people by pricing them out or presenting features not aligned with their needs and preferences (Torres Citation2020). Gentrification and loss of third places that older people value can result in loneliness (Astell-Burt et al. Citation2022), exclusion (Burns et al. Citation2012), and place alienation (Diaz-Parra and Jover Citation2021); all factors that may make a neighborhood a ‘lonelygenic environment’ (Feng and Astell-Burt Citation2022). The complex contingency of this issue with respect to age is readily observable in trendy tourist areas such as many central Porto neighborhoods, with a noisy and crowded commercial atmosphere holding attraction for younger transient migrants (Cocola-Gant and Lopez-Gay Citation2020), but presenting safety concerns and other potentially negative health consequences for older adults (Cocola-Gant Citation2023).

Older people often wish to age where they live (Ratnayake et al. Citation2022), but as they become more dependent on their immediate surroundings due to decreasing mobility and wealth become more restricted (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Citation2015). Changes like those linked to gentrification may pose additional financial, social, emotional and, consequently, health challenges. Thus, the impact of gentrification on their lives goes well beyond the daunting threat of physical displacement. Furthermore, as our research reveals, even older people who can accommodate changes and maybe even benefit from them may suffer an emotional penalty due to concerns for relatives or friends who are vulnerable to housing and economic insecurity. As has been previously argued, displacement may also negatively impact those older adults who manage to stay, as their social connections may shrink (Buffel and Phillipson Citation2019, Torres Citation2020). This may also have a health cost.

The main limitation of this study is the non-inclusion of people who underwent or were threatened by physical displacement, which, as both our results and previous research (Anguelovski et al. Citation2020, Citation2021)) suggest, may be one of the most health-significant impact of gentrification. Therefore, the issues highlighted by the interviewees could be potentially even more pronounced if those who were displaced were also in our sample. This was a qualitative study to explore how older people living in Porto feel gentrification affects their health and well-being. Therefore, their accounts were not linked to objective health data available in the cohort. Future studies about the topic within this (and other cohorts) should harness the rich quantitative health data available and adopt a mixed or multi-methods approach to enrich the study results and conclusions. In a time where gentrification has gone global and transnational, we hope this article may inspire further research on the issue, particularly in the European periphery, where the consequences of transnational gentrification are a pressing issue in several cities (Hayes and Zaban Citation2020). Our study improves available knowledge about the consequences of gentrification for older adults, a group that faces important challenges concerning urban change to which insufficient attention has been paid. Given its ubiquity and prominence in the contemporary urban landscape and its particular health needs, it is essential to advance further knowledge on how gentrification may affect the health of older adults. It provides nuanced views on the relationship between gentrification, well-being, and health in older age in a city currently undergoing a quick trend of transnational gentrification from a diverse sample of interviewees from gentrifying and non-gentrifying neighborhoods, thus providing a broader view of the phenomenon. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first studies of its kind in Portugal.

Conclusion

Gentrification-led changes seem to bring benefits and potential harms to older adults’ health and well-being. The consequences highly noted were mostly related to mental health and worsening quality of life, while the advantages of gentrification changes were related to a lively and clean city. Gentrification might thus be seen as a challenge to, and an opportunity for, promoting healthy aging. It is imperative to note that, while many older people seek to age in place and some become more dependent on their immediate surroundings, gentrification threatens renters with displacement while changing places in a way that might alienate many older people. Therefore, urban policymaking should consider the needs of older locals to support flourishing in the later stages of life.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the participants enrolled in EPIPorto for their kindness.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Cláudia Jardim Santos

Cláudia Jardim Santos is PhD candidate in Public Health integrated into the LAB “Health and Territory” of the Laboratório para a Investigação Integrativa e Translacional em Saúde Populacional. She completed her bachelor’s degree in biomedical sciences with a minor in pharmaceutical biomedicine at the University of Aveiro. She concluded her Master’s degree in Public Health at the Institute of Public Health of the University of Porto. Cláudia is most interested in addressing critical public health issues especially related to the spatial variations of disease in populations and the mechanisms of neighbourhood effects on health.

José Pedro Silva

José Pedro Silva holds a PhD in sociology, specialty of sociology of environment and territory. He has worked on several research topics, generally using qualitative methodological approaches. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4845-854X

Thomas Astell-Burt

Thomas Astell-Burt is an Australian Research Council (ARC) Future Fellow at the University of Sydney and a Founding Co-Director of the Population Wellbeing and Environment Research lab (www.PowerLab.site). With over 230 publications, Professor Astell-Burt is cited by Expertscape as the world’s leading scientist on parks and recreation out of over 10,000 researchers globally. Professor Astell-Burt is currently investigating social prescribing and other novel social, behavioural, and environmental solutions to loneliness and its deadly consequences (e.g., depression, diabetes, dementia) using a range of methods including Geographic Information Systems, cohort studies, multilevel modelling, and randomised trials. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1498-4851

Henrique Barros

Henrique Barros graduated in Medicine in 1981. He is Full Professor of Epidemiology at the University of Porto since 1999. He is currently member of the Executive Commission of the National Ethical Committee for Clinical Investigation (CEIC), President of the Institute of Public Health, University of Porto, Executive Board Member of ASPHER and Past-President of the International Epidemiological Association (2017-20). He has developed research in national and international projects in clinical and perinatal epidemiology and cardiovascular, infectious, and cancer diseases, resulting in (co)authorship of hundreds of scientific publications in international journals. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4699-6571

Ema Torres

Ema Torres graduated in Sociology, from the Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, where she completed her Master’s degree in the same area. She has collaborated with ISPUP since 2017, integrating the Geração XXI project to perform administrative tasks. Between 2020 and 2023, she was a trained interviewer in three different epidemiologic studies. Ema also collected information to prepare Municipal Health Plans for Maia municipality, in 2021, and Gondomar municipality, in 2023. Between November 2021 and May 2023, she was part of the “Health and Territory” laboratory, where she performed administrative and interviewing tasks, mainly in the EPIPorto cohort.

Ana Isabel Ribeiro

Ana Isabel Ribeiro is an epidemiologist and health geographer. She is a Researcher at the Public Health Institute of the University of Porto and the leader and founder of Lab Health and Territory where she directs a program of research exploring the impact of the neighbourhood’s social and biophysical features on individuals’ health. She has authored >100 publications and led major research projects on urban and environmental health. She also participated in different European projects. Moreover, Ana holds the position of Invited Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Medicine (University of Porto), being actively engaged in training and student supervision. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8880-6962

References

- Anguelovski, I., et al., 2020. Gentrification and health in two global cities: a call to identify impacts for socially-vulnerable residents. Cities & health, 4 (1), 40–49. doi:10.1080/23748834.2019.1636507.

- Anguelovski, I., et al., 2021. Gentrification pathways and their health impacts on historically marginalized residents in Europe and North America: global qualitative evidence from 14 cities. Health & place, 72, 102698. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2021.102698

- Aruda Urquiaga, A., et al, 2020. Platform-mediated short-term rentals and gentrification in Madrid. Urban Studies, 57, 3095–3115.

- Astell-Burt, T., et al., 2022. Green space and loneliness: a systematic review with theoretical and methodological guidance for future research. Science of the total environment, 847, 157521. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157521

- Binet, A., et al., 2021. ‘It feels like money’s just flying out the window’: financial security, stress and health in gentrifying neighborhoods. Cities & health, 6 (3), 536–551. doi:10.1080/23748834.2021.1885250.

- Boddy, C.R., 2016. Sample size for qualitative research. Qualitative market research: An international journal, 19 (4), 426–432. doi:10.1108/QMR-06-2016-0053.

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V., 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3 (2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Brummet, Q. and Reed, D., 2019. The effects of gentrification on the well-being and opportunity of original resident adults and children. FRB of Philadelphia Working Paper No. 19-30. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3421581

- Buffel, T. and Phillipson, C., 2019. Ageing in a gentrifying neighbourhood: experiences of community change in later life. Sociology, 53 (6), 987–1004. doi:10.1177/0038038519836848.

- Burns, V.F., Lavoie, J.P., and Rose, D., 2012. Revisiting the role of neighbourhood change in social exclusion and inclusion of older people. Journal of aging research, 2012, 148287. doi:10.1155/2012/148287

- Carminati, L., 2018. Generalizability in qualitative research: a tale of two traditions. Qualitative health research, 28 (13), 2094–2101. doi:10.1177/1049732318788379.

- Carvalho, L., et al., 2019. Gentrification in Porto: floating city users and internationally-driven urban change. Urban geography, 40 (4), 565–572. doi:10.1080/02723638.2019.1585139.

- Chamusca, P., et al, 2019. The role of Airbnb creating a “new”-old city centre: facts, problems and controversies in Porto, Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles. Madrid, Spain. doi:10.21138/bage.2820.

- Cocola-Gant, A., 2018. Struggling with the leisure class: tourism, gentrification and displacement.

- Cocola-Gant, A., 2023. Place-based displacement: touristification and neighborhood change. Geoforum, 138, 103665. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2022.103665

- Cocola-Gant, A. and Gago, A., 2019. Airbnb, buy-to-let investment and tourism-driven displacement: a case study in Lisbon. Environment & planning A: Economy & space, 53 (7), 1671–1688. doi:10.1177/0308518X19869012.

- Cocola-Gant, A. and Lopez-Gay, A., 2020. Transnational gentrification, tourism and the formation of ‘foreign only’ enclaves in Barcelona. Urban Studies, 57 (15), 3025–3043. doi:10.1177/0042098020916111.

- Cole, H.V.S., 2020. A call to engage: considering the role of gentrification in public health research. Cities & health, 4 (3), 278–287. 10.1080/23748834.2020.1760075.

- Cole, H.V.S., et al., 2021. Breaking down and building up: gentrification, its drivers, and urban health inequality. Current environmental health reports, 8 (2), 157–166. doi:10.1007/s40572-021-00309-5.

- Curtis, S., et al., 2000. Approaches to sampling and case selection in qualitative research: examples in the geography of health. Social science & medicine, 50 (7–8), 1001–1014. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00350-0.

- Diaz-Parra, I. and Jover, J., 2021. Overtourism, place alienation and the right to the city: insights from the historic centre of Seville, Spain. Journal of sustainable tourism, 29 (2–3), 158–175. doi:10.1080/09669582.2020.1717504.

- Feng, X. and Astell-Burt, T., 2022. Lonelygenic environments: a call for research on multilevel determinants of loneliness. The lancet planetary health, 6 (12), e933–e934. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00306-0.

- Fernandes, J., et al., 2018. Gentrification in Porto: problems and opportunities in the past and in the future of an internationally open city. GOT - Journal of geography and spatial planning, 15 (15), 177–198. doi:10.17127/got/2018.15.008.

- Flyvbjerg, B., 2006. Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative inquiry, 12, 219–245.

- Galea, S. and Vlahov, D., 2005. Urban health: evidence, challenges, and directions. Annual review of public health, 26 (1), 341–65. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144708.

- Gant, A.C., 2016. Holiday rentals: the new gentrification battlefront. Sociological research online, 21 (3), 112–120. doi:10.5153/sro.4071.

- Glaser, B.G. and Strauss, A.L., 1967. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New Brunswick, USA: Aldine Transaction.

- Green, J. and Thorogood, N., 2004. Generating and Analysing Data. In: Qualitative methods for health research, 102–104.

- Hayes, M. and Zaban, H., 2020. Transnational gentrification: the crossroads of transnational mobility and urban research. Urban Studies, 57 (15), 3009–3024. doi:10.1177/0042098020945247.

- HelpAge International, 2016. Ageing and the city: making urban spaces work for older people. London: HelpAge International.

- Hwang, J. and Ding, L., 2020. Unequal displacement: gentrification, racial stratification, and residential destinations in Philadelphia. American journal of sociology, 126 (2), 354–406. doi:10.1086/711015.

- Ine, 2022. Estimativas de População Residente, Portugal, NUTS I, II e III e Municípios. Exercício Ad hoc 2020 e 2021 [Online]. Available from: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_destaques&DESTAQUESdest_boui=540837471&DESTAQUESmodo=2 [Accessed 7 Jun 2023].

- Lamont, M. and Swidler, A., 2014. Methodological pluralism and the possibilities and limits of interviewing. Qualitative sociology, 37 (2), 153–171. doi:10.1007/s11133-014-9274-z.

- López, P., Rodríguez, A.C., and Escapa, S., 2022. Psychosocial effects of gentrification on elderly people in Barcelona from the perspective of bereavement. Emotion, space and society, 43, 100880. doi:10.1016/j.emospa.2022.100880

- Mayring, P., 2007. On generalization in qualitatively oriented research. Forum qualitative sozialforschung/forum: Qualitative social research, 8 (3). doi: 10.17169/fqs-8.3.291.

- Mendes, L. 2021. Transnational gentrification and the housing market during pandemic times, Lisbon style. Urban geography, 42, 1003–1010.

- Moos, M., 2016. From gentrification to youthification? The increasing importance of young age in delineating high-density living. Urban Studies, 53 (14), 2903–2920. doi:10.1177/0042098015603292.

- Moos, M., et al., 2019. Youthification across the metropolitan system: intra-urban residential geographies of young adults in North American metropolitan areas. Cities, 93, 224–237. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2019.05.017

- OECD, 2019. Oecd reviews of pension systems: Portugal.

- OECD/European Observatory On Health Systems and Policies, 2019. Portugal: country health profile 2019.

- Oldenburg, R. and Brissett, D., 1982. The third place. Qualitative sociology, 5 (4), 265–284. doi:10.1007/BF00986754.

- Patton, M.Q., 1990. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Newbury Park: SAGE Publications, inc.

- Ramos, E., Lopes, C., and Barros, H., 2004. Investigating the effect of nonparticipation using a population-based case-control study on myocardial infarction. Annals of epidemiology, 14 (6), 437–441. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2003.09.013.

- Ratnayake, M., et al., 2022. Aging in place: are we prepared? Dela journal of public health, 8 (3), 28–31. doi:10.32481/djph.2022.08.007.

- Sánchez-Ledesma, E., et al., 2020. Perceived pathways between tourism gentrification and health: a participatory photovoice study in the Gòtic neighborhood in Barcelona. Social science & medicine, 258, 113095. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113095

- Schnake-Mahl, A.S., et al., 2020. Gentrification, neighborhood change, and population health: a systematic review. Journal of urban health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 97 (1), 1–25. doi:10.1007/s11524-019-00400-1.

- Sigler, T, and Wachsmuth, D., 2016. Transnational gentrification globalisation and neighbourhood change in Panama’s Casco Antiguo. Urban Studies, 53, 705–722. doi:10.1177/0042098014568070.

- Sigler, T. and Wachsmuth, D., 2020. New directions in transnational gentrification: tourism-led, state-led and lifestyle-led urban transformations. Urban Studies, 57, 3190–3201. doi:10.1177/0042098020944041.

- Smith, G.S. and Thorpe, R.J., Jr., 2020. Gentrification: a priority for environmental justice and health equity research. Ethnicity & disease, 30 (3), 509–512. doi:10.18865/ed.30.3.509.

- Smith, N., 1979. Toward a theory of gentrification a back to the city movement by capital, not people. Journal of the American planning association, 45 (4), 538–548. doi:10.1080/01944367908977002.

- Smith, R.J., Lehning, A.J., and Kim, K., 2018. Aging in place in gentrifying neighborhoods: implications for physical and mental health. The gerontologist, 58 (1), 26–35. doi:10.1093/geront/gnx105.

- Sýkora, J., et al., 2022. ‘It is natural’: sustained place attachment of long-term residents in a gentrifying Prague neighbourhood. Social & cultural geography, 24 (10), 1941–1959, doi:10.1080/14649365.2022.2115534.

- Torres, S., 2020. “For a younger crowd”: place, belonging, and exclusion among older adults facing neighborhood change. Qualitative sociology, 43, 1–20.

- Tran, L.D., et al., 2020. Impact of gentrification on adult mental health. Health services research, 55 (3), 432–444. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13264.

- Tulier, M.E., et al., 2019. “Clear action requires clear thinking”: a systematic review of gentrification and health research in the United States. Health & place, 59, 102173. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102173

- United Nations Department Of Economic And Social Affairs, 2015. Income poverty in old age: an emerging development priority [Online]. Available from: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/ageing/documents/PovertyIssuePaperAgeing.pdf.

- Versey, H.S., 2022. Gentrification, health, and intermediate pathways: how distinct inequality mechanisms impact health disparities. Housing policy debate, 33 (1), 6–29. doi:10.1080/10511482.2022.2123249.

- Wachsmuth, D. and Weisler, A., 2018. Airbnb and the rent gap: gentrification through the sharing economy. Environment & planning A: Economy & space, 50 (6), 1147–1170. doi:10.1177/0308518X18778038.

- Zukin, S., et al., 2009. New retail capital and neighborhood change: boutiques and gentrification in New York City. City & community, 8 (1), 47–64. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6040.2009.01269.x.