ABSTRACT

Apartment-living is on the increase, despite this, little is known about how it influences food practices. We explored the interrelations between apartment kitchen design and food practices using Photo elicited interviews and an inductive thematic analysis, with a diverse sample of twelve apartment-dwellers across four suburbs of Melbourne, Australia. Participants took 160 photographs representing their food practices to guide interviews. Three themes emerged from the interview analysis: ‘Choices’ which included participants’ cooking preferences, as well as their choice of apartment in which to prepare these meals; ‘Challenges’ which referred to the kitchen design barriers to home cooking including issues relating to storage, food preparation, washing up, ventilation, lighting and recycling and; ‘Changes’ which described the physical adaptations to kitchens and behavioural adaptations to food practices as a result of poor kitchen design. Based on these findings, using a socioecological framework, we describe the proximal and distal interrelationships between kitchen design and food practices; and discuss how these could be further researched to inform future apartment design policy.

Introduction

It is predicted that by 2050, over two thirds of the world’s population will live in cities or urban centres (United Nations Citation2019). Apartment living is a key response to housing and land shortages associated with increasing and changing urban populations. Even countries with a large land mass and a strong history of detached housing such as Australia, are witnessing increasing urbanisation and growth in higher-density apartment-living. In 2021, over 2.5 million people, or approximately 10% of the Australian population lived in apartments (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2021) and apartments in blocks four or more storeys increased their share from 5.4% of Australia’s dwelling stock in 2016, to 7.5% in 2021 (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2021). The shift to high-density housing brings (and reflects) lifestyle changes for many occupants. Food practices, including the planning, purchasing, storage, and preparation of food (Comber et al. Citation2013, Vaughn et al. Citation2013, Olstad and Kirkpatrick Citation2021) are a particular issue that may be influenced apartment-living.

What we eat affects the aetiology of a number of diseases including obesity, diabetes, some forms of cancer, and depression (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Citation2019). The current diets of most Australian adults do not meet dietary guidelines and this contributes substantially to the overall burden of disease (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Citation2019). While food practices play a vital role in the overall well-being of the population (Stokols Citation1992), the interrelations between apartment living and domestic food practices (and particularly changes in food practices as a result of moving into an apartment) remains unknown. Given the growing number of people living in apartments in Australia and internationally, this warrants further attention.

Apartments provide different environments for food practices compared with suburban homes. Research on apartment kitchens to date has tended to focus on spatial layout, to improve adaptability and promote a circular economy (Hagejärd et al. Citation2020, Ollar et al. Citation2022), with limited explicit exploration of how apartment households use kitchens in their food practices. As a higher density form of living, apartment buildings are often located nearer to amenities, services and retailers including food retailers such as cafes, restaurants and fresh food outlets. At the same time, they are often much smaller than detached houses (Oliver Hume Corporation Pty Ltd Citation2015) and may be designed in ways that limit the functional use of space. Indeed, developers (Malinowski Citation2015) and architects (Bestard Citation2016) have argued that individual kitchens may not be necessary in locations where cooking can be outsourced through dining out, home delivery or the use of communal kitchens. Despite these predictions, there is a significant evidence gap in our understanding of the lived experiences of apartment dwellers’ food practices.

Apartment design and apartment living may constrain or enable domestic food practices. A recent analysis found those living in high-rise apartments across Australia spent substantially more of their weekly food budget on eating out compared to those living in other dwelling types (Oostenbach et al. Citation2021). This analysis, however, does not inform us if the choice to eat out is influenced by the location or design of their apartment. It also does not provide any indication of the healthiness of the food consumed; and this warrants attention given cooking at home is linked to health benefits (Mills et al. Citation2020). To our knowledge, only two studies have examined apartment dwelling and food practices. The first, a study from Montreal, examined the food practices of single men living in apartments and found that convenience and budget were key drivers of food choice (Marquis and Manceau Citation2007). A second study limited to families with preschool-age children in Melbourne and Brisbane, noted some challenges to maintaining desired food practices as a result of the constraints of apartment living such as insufficient storage, food preparation areas being restricted to an area immediately adjacent to the stove top making it dangerous for young children to participate and insufficient space for a family dining table (Dunn et al. Citation2021). However, without a more comprehensive evidence base, it remains unclear how apartment living influences food practices.

As little is known on this topic at present, we are at the stage of observing these complex relations, rather than setting out determinist hypotheses. Nevertheless, we do have some preconceptions about the topic. We expect the kitchen to play a role in shaping food practices, but we also expect apartment-dwellers to have a range of coping mechanisms in such kitchens. Further, we expect apartment design to play an indirect role in resident’s lived experiences of food practices in their apartment setting. To this end, a socioecological approach provides a useful conceptual framework to link food practices to individual living conditions, social norms and the broader policy environment. Furthermore, existing research posits the concurrent role of individual, social and environmental influences on food practices (Pitt et al. Citation2017) and socioecological frameworks have been used to link these levels of influence to food behaviours (Story et al. Citation2008).

Using photo-elicited interviews from a pilot study with 12 residents of apartments in Melbourne, the capital city of the State of Victoria in Australia, this study aimed to explore the interrelations between apartment living and food practices. Our focus was on understanding this through the eyes and experiences of those we are seeking to study, with participants reflecting on the layout of their kitchen via the photographs they provided to us. Further, unlike previous studies, we sought to document a range of experiences from all types of apartment dwellers, rather than a specific demographic. Melbourne, in common with other Australian capital cities, has experienced a growth in apartment living over the past twenty years (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2021). Despite this, apartment design guideline requirements in relation to cooking and eating spaces are limited (Foster et al. Citation2020, The State of Victoria Department of Environment Land Water & Planning Citation2021). This study builds on a previous praxis paper (Thornton et al. Citation2022) but is novel in that the links between characteristics of apartment living and food practices have not been examined in Australia or internationally. This is significant in terms of public health nutrition, given that apartment living on a large scale is new and growing in Australia with potential impacts on food practices not yet understood. This research therefore fills a gap in the academic literature on apartment living and food practices, while also contributing guidance for the improved design of those apartments.

Methods

Methodology

A qualitative approach was adopted for this study, as it is well suited to the exploratory nature of the research (Hansen Citation2020) and allowed the documentation of apartment dwellers’ experiences of food practices. Specifically, a qualitative descriptive approach was employed as this is particularly useful in obtaining straightforward responses relevant to addressing practical issues and ultimately to inform apartment design policy (Sandelowski Citation2000).

Participant recruitment

Melbourne was selected as the metropolitan setting to conduct the study, given the range of apartment designs and diverse backgrounds of households in this city. In particular, the suburbs of Moonee Ponds, North Melbourne, Footscray and Docklands were selected as the four suburbs of focus, given these neighbourhoods represented a mix of both high and low socioeconomic areas and distance to the Melbourne Central Business District (CBD) (e.g. inner city and middle suburbs up to 10 km from the CBD).

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Deakin University Human Ethics Committee (approval number HEAG-H 118_2019). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

To recruit participants, over 800 letters inviting residents to participate in a study on the wellbeing of apartment dwellers, were sent to random apartment addresses across the aforementioned suburbs. Of these 800 addresses, we had no way of knowing whether they were occupied and, if so, whether it was by a short-term renter, long term renter, or owner occupier. These addresses were identified using the Victorian Government’s Vicmap Data database. The invited recipients who wished to be involved in the study were then required to complete an online screening questionnaire via a Qualtrics weblink. The screening tool included questions confirming whether or not they live in the apartment, age, sex, postcode, tenure type, number of bedrooms and, in particular, frequency of preparing meals at home. In addition to needing to confirm that they lived in an apartment as the main screening criteria, our study purposefully then selected participants who prepared dinner at home at least twice per week, to ensure we included those with some experience of preparing meals in their apartment kitchens. The other screening questions we used to help contextualise participant responses according to factors such as number of bedrooms (as an indicator of apartment size, tenure type etc.). As a result, of the thirty-three responses received, a total of 18 met the inclusion criteria. All 18 respondents were invited to participate in the study, of these 12 respondents provided consent and agreed to participate.

Data collection

Photo elicited interviews was chosen as the data collection methodology (Harper Citation2002). Members of the research team have previously used Photo elicited interviews as a method and it has proven to deliver rich accounts, both visual and textual on the subject (Warner et al. Citation2016). Specifically, this study used respondent-controlled Photo elicited interviews, which means the participants themselves take photographs prior to the interviews. Benefits of PEI include developing an understanding of complex and varied topics from the participant’s perspective (Pain Citation2012) and previous successful application of Photo elicited interviews to the study of food practices (Marquis and Manceau Citation2007, Lachal et al. Citation2012, O’Connell Citation2013, Mills et al. Citation2017a).

Participants were asked to take up to 15 photographs over a two-week period, which would be used as prompts in a follow-up face to face interview. Participants were provided with a photography manual to provide further guidance on taking their photos, which explained that the photographs may include items such as their kitchen, food storage and preparation space, cooking utensils and other relevant aspects of their dwelling related to food practices. A total of 160 photos were received, ranging from 9 to 17 photos per participant.

Once photographs were received, participants were contacted, and a face-to-face interview scheduled. All interviews were conducted in neutral public locations. A semi-structured interview guide was used, which involved discussing each of the photos with participants, as well as some broader qualitative questions regarding apartment living and food practices. Purposefully, questions in the interview guide were used sparingly, as interviews were guided largely by participants and what they perceived as relevant to discuss regarding their photos, experiences of apartment living and food practices. A total of 10 hours and 40 minutes of interview data was obtained. At the conclusion of the interview, participants were provided with a $AUS50 gift card in recognition of their time contributing to the study. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim by an external company.

Data analysis

An inductive analytical approach was used and considered appropriate given the limited knowledge base on this topic. Analysis was guided by the six-step process of Braun and Clark (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). This included data immersion by the research team through reading and re-reading the transcripts, coding of the transcripts, the creation of categories to collate codes, and based on these categories, themes were identified. Exemplar photographs and quotes were identified to highlight key findings. The analysis was led by the first author and theme identification confirmed through a reflexive process whereby the first author refined the themes in discussion with the other authors.

Results

Study sample

The characteristics of the pilot study sample are outlined in . The sample was diverse, with a mixture of residential locations, and apartment size (as determined by the number of bedrooms). Half of the participants were renters and the age of participants ranged from 18 – over 64 years.

Table 1. Participant study sample.

There were also a variety of histories around apartment living, from those new to it, to those who had lived in apartments most of their lives. Some were downsizing, while for others their apartment was an early step in their independent housing experience. Nevertheless, three common themes emerged that describe participant’s experiences of food practices in relation to their apartment living: choices, challenges and changes.

Interview themes

Choices

Participants’ choices related to their preference for home cooked meals, as well as their choice of apartment in which to prepare these meals. We recognise that ‘choice’ is always constrained by social and material structures, and that both conscious reasoning and less conscious conventions and understandings are involved. While our study purposefully selected participants who prepared dinner at home at least twice per week, participants’ reasons for choosing home cooking were multi-faceted.

For some this choice was for financial reasons. However, more often it was connected to their need/desire to consume specific diets, live sustainably or to eat ‘healthily’. One participant explained:

I am very very conscious about what I eat … , if I’m by myself, I almost will never go out … to a restaurant … I can control what I order but I can’t control what’s in the food … I tend only to go out if someone’s invited me out … It’s kind of a trade-off – it’s always nice to have a really delicious meal, even if it is unhealthy, particularly with your friends, but then I’ve got my other goals … (P10)

Although all spoke of the availability of restaurants in their neighbourhood, as well as home food delivery options, these tended to be reserved for specific occasions, such as visits from family:

Say the kids come and we’ll buy pizzas. Not so healthy but you don’t do it every night. They don’t mind. Then we go for dessert somewhere. (P12)

There were also ethical concerns that influenced their choice to use (or avoid) home delivery services:

… . so, these guys on the corner, they’re the Uber Eats type brigade and there’s always a handful of motorbikes and they’re just sort of sitting around … I feel really guilty because I’ve heard that they really don’t get paid much and I think it’s such hard work to deliver this stuff and so much packaging … people in my apartment building will get breakfast delivered and I think there’s a cafe within 30 metres… So, everyone is different but it’s just really not my thing. (P3)

Several participants did choose to order meal boxes that contain ingredients for food preparation at home. This was for both the convenience of having pre-prepared menus as well as having the food provided (especially single portions) however, most participants described preparing their own meals from scratch.

Given the preference for home cooking, it was unsurprising that there was consideration of their apartment’s kitchen size and facilities in their choice of where to live. Participants spoke about how they had chosen not to live in apartments that did not provide obvious facilities to support home cooking. For example, one participant described how he rejected apartments that did not offer an oven and stovetop:

When we were looking for apartments, I was really shocked to find they didn’t all have that (an oven and four rings on the stove) … . The idea of not being provided with that would not work for me, that’s camping and yet I keep seeing it. (P11)

Others spoke of the need for adequate dining space in choosing an apartment:

I think having looked at quite a lot of apartments over the last three months … Most of them you can’t fit a dining table in anywhere, so it’s really not conducive to eating at home unless you microwave dinners, really. (P7)

Food preparation areas were also an important consideration, with one participant noting:

One of the things I liked about my apartment is it’s got this (fixed) island bench … that’s actually quite important for me … a lot of apartments these days … . they don’t have a bench – the kitchen is built into a wall, so you’ve got like a little cut out which will have your stove and your cupboards above it and a fridge next to it and I really hate that … (P10)

Overall, participants were generally accepting of their choice of apartment kitchen, noting it: ‘wasn’t their dream kitchen’ and was ‘a little cramped but workable’ (P4). One participant summed this up explaining:

Challenges

Despite speaking of overall general satisfaction with their apartment kitchens, particularly in comparison with others they had seen, participants described a number of challenges to their everyday food practices. These related to the design of their kitchen facilities, rather than solely the size.

For example, while kitchen cupboard space was recognised as being limited within many of the respondent’s apartments, particular reference was made to challenges posed by the height, location and design of the cupboards, which impacted on their use and functionality. As a result, there were restrictions on the cooking equipment and utensils that could be stored, the quantity of food they could purchase and access to food items in their pantry limited food practices. For example, one participant in describing their low, deep storage cupboard explained:

That’s one of those hell cupboards … you make all these horrible cracking noises when you are getting down and opening it … . And then you’ve got to sort through everything … I don’t know what we’ve got in there and you know it’s a disincentive to bake … (P9) ()

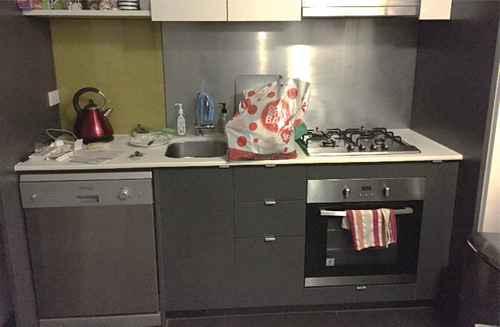

Most residents identified that bench space was limited with P1 arguing: ‘bench space in my new apartment basically doesn’t exist’ (). Consequently, this was a challenge for food preparation:

… the working space is so small it just decreased the access infinitely and I was just puzzled, you know, I couldn’t understand how do I cook? Every time I took the ingredients out, I felt that I don’t know what to do or where to go … (P6)

The size of the oven and stovetop was also a challenge to desired food practices, limiting what could be placed in the oven and whether multiple items could be on the stovetop at any one time:

Oven drives me mad. You can’t cook a family roast in the oven. (P11)

We only cook basic foods at home, like meat and three veg, stir fry or something. Anything more complex that requires multiple things on the stove top, it’s got five elements … but they are so close together so if you’ve got a 32 cm pan on one, it kind of blocks everything else so you can’t really have two things going at the same time. (P7) ()

There were variations between apartments in terms of whether one sink or two sinks were present. Perhaps unexpected was the absence of a drying area next to the sink. Combined, the location, size and number of sinks and the absence of a drying area was challenging:

We’ve only got this one little sink. We can’t even fit a whole plate in there. (P8)

… . the sink area … it’s not cut out for washing pots. It doesn’t have a draining area. (P11) ()

There was widespread recognition among participants of the interplay between food practices and environmental responsibility. However, the desire to collect food packaging and dispose of this responsibly by recycling, rather than through the building garbage chute was challenged by limited space, or poor design of recycling waste storage areas in their kitchens. For example, one participant explained:

I end up with packaging - one person – the amount of packaging I end up with is phenomenal, it blows my mind. So, it is never going to fit inside the little space I have available. (P10) ()

Poor apartment ventilation was a frequent challenge. Three main factors contributed to this: the quality of the rangehood; the overall apartment design and the (in)ability to open windows or doors. Ventilation was problematic for cooking smells that lingered within the apartment and spread to communal areas. Furthermore, participants spoke of the frustration of ventilation issues regularly triggering smoke alarms in their apartment and the overall building.

… our apartment has really bad air flow. In fact, we’ve really got no air flow … a lot of time the fire alarms will go off because people will burn what they’re cooking and they’ll think oh, I’ll just open up my apartment door. And then it just sends off the alarms inside the building. (P9)

Lighting in the kitchen area of apartments was a final challenge to desired food practices. One participant explained:

The lighting wasn’t really designed for a kitchen, so it isn’t very well lit … so unless it is a really bright evening in the summer, I have to be careful when I’m chopping … you need that light … . We could put a lamp or something but that would be – Where are you going to plug it in? Where’s the wire going to go? (P11)

Changes

All the participants spoke of making some sort of changes to their food practices because of the challenges posed by their apartment kitchen design. In terms of physical changes, decluttering (or the process of removing or disposing of unwanted or infrequently used items) was commonly described. This was particularly the case for those who had downsized from a house. Decluttering was generally seen in positive terms, as a new start to re-organise themselves and live a healthier lifestyle:

We’re also mindful we don’t buy extra or things that we don’t need … we don’t keep any unnecessary things … at first, I was quite shocked but now I feel it’s a positive shift because with less things I guess it’s a bit easier to just manage and operate and also – our mindset is becoming different more around healthy food, healthy living. (P6)

A key finding was the range of physical changes participants had undertaken to make their cooking and eating spaces work for the food practices. At the simplest level, participants spoke of having to prioritise the items they had immediately available for use in their kitchens:

We try not to keep too many appliances out because otherwise you just have no bench space at all. (P2)

However, often participants had to make structural changes to their kitchens to accommodate everyday items key to their food practices. For some this involved purchasing a freestanding cupboard, shelving or for P12 ‘an island bench and that travels with us on wheels’.

This is the island bench we bought. It’s got drawers. It’s got a big wide work top and drawer with all the utensils in it and saucepans, dinner plates. It works well. (P12) ()

Others made more permanent structural adjustments:

… . for example, with cutlery and all the plates and everything … . The way we actually dealt with that is my husband built in a separate cabinet which had all the drawers and the microwave space, so it all is there now. That way we were able to manage the space. (P6) ()

Some participants described how they adjusted to their limited space by moving food practices into other areas of their apartment:

I have had a big bag of rice and there’s nowhere to put it. So, it’s like that’s going under the bed until we need it … also – I’ll buy like a case of beer … that’s going in my bedroom somewhere. (P2)

Because I never use the laundry sink for anything else, I have a box in there for my recycling … . So that’s another use of my limited storage space. (P4)

Despite the above examples, some participants were unable to make physical changes to enable them to support their desired food practices. For example, P9 wanted to build more storage, to save money by buying food in bulk, but noted ‘for two people on low incomes as ourselves, you’ve got to have money to make money’. Where physical changes could not be made, participants had to alter their desired food practices. For instance, participants spoke of changing what they cooked and avoiding certain foods because of the poor ventilation in their apartments.

… It will impact cooking eggs or something, a smell will last around for a long time … if I cook steak or something, I’m likely to set the alarms off … . That might make me think now I’m going to cook something else; I’m not going to do that … I cooked salmon on the stove the other night and my daughter could smell it hours later. (P5)

Limited bench space and small stove tops also prohibited the cooking of meals that were complicated or required space. This in turn meant that some participants could not entertain in their apartments. One participant explained:

I can’t make anything too big and adventurous that requires an awful lot of laying out of ingredients. So, bread is usually a bit of an out. Because of the rolling space. I mean, it shouldn’t be … it becomes particularly difficult if I want to make something for a lot of people … . If I’m going to cook for four or five people, then we may as well just eat out. (P9)

Difficulty in accessing stored items also limited food practices with some participants describing giving up on cooking certain foods because it was too hard to access the necessary items.

It’s very hard to get things that I actually want to use … to get things down to a height I can reach them. I do have osteoporosis and I have broken a wrist a couple of times, so I prefer not to be climbing … Well, it lessens one’s enthusiasm. Yeah, demotivates you. (P5)

Overall, we observed a number of changes and adaptions in food practices precipitated by the design of apartment kitchens for our respondents. While participants had ‘chosen’ their new dwellings for a range of reasons, once they occupied them, they often found that their kitchens did not allow expected food practices or directed them in new ways. The usually smaller spaces were embraced as part of the package of down sized, higher density living. However, the design limitations that became apparent once the apartment was occupied led to a range of adaptations – in what food was purchased, how it was stored or prepared and how many people were catered for. In addition to new or modified food practices, there were also changes in the kitchen itself – with new benches and cupboards added or other parts of the apartment used for food preparation or storage.

Discussion

The findings from our study provide new insights into the interrelationships between apartment kitchen design and food practices. These findings fill a knowledge gap given the overall paucity of evidence on the general domestic built environment and food practices (Le Bel and Kenneally Citation2009) and provide a unique contribution since housing/kitchen design is rarely considered as a determinant of home cooking (Mills et al. Citation2017b). Our findings are also significant given the growing trend in apartment living in Australia (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2021) and many other developing economies. Here, we discuss these interrelationships through a socioecological lens, from proximal to distal influences on the food practices of apartment dwellers, as well as identifying implications for public health, nutrition and apartment design policy development (see ).

Figure 9. Socioecological analysis of the interrelationships between apartment kitchen design and food practices.

At the proximal level, apartment dweller’s food practices in our study were a product of their personal circumstances (e.g. the need to downsize or to access affordable housing) and preferences (e.g. their desire for home cooking) and these in turn, contributed to the choices they made about their apartment kitchens. This interplay between the individual and their immediate environment is similar to that described previously in conceptual frameworks and research on food practices in other settings (Stokols Citation1992, Brug Citation2008, Story et al. Citation2008, Pitt et al. Citation2017). Uniquely, in the current study, this interrelationship was found to be disrupted by both restrictions in the size of the kitchen, along with poor design of key elements of the kitchen.

Poorly designed storage areas, where food items and cooking equipment were difficult to locate and then access, was a constraint to home cooking in the current study, aligning with research noting that proximity and visibility of food can influence intake (Privitera and Creary Citation2013). The size and location of benches and stovetops also proved a challenge to home cooking. In line with research focusing on families with children in apartments (Dunn et al. Citation2021), the current study found that where bench space was located in the area immediately adjacent to stove tops, this restricted participant’s ability to prepare a meal, particularly when this involved cooking for more than one person or using a range of ingredients. Significantly, our study thus indicates that restrictions in food practices experienced by participants was not just a function of having a smaller kitchen.

Poor ventilation and lighting of apartment kitchens as barriers to home cooking is worthy of specific mention. Ventilation issues were a particularly common concern amongst our participants and limited what could be cooked, while poor lighting impacted on food preparation. Significantly, while ventilation and lighting of apartments has been discussed at length in a recent review on apartment residents’ wellbeing (Foster et al. Citation2020) and in research on spatial criteria for adaptive capacity in kitchen design (Ollar et al. Citation2022), to our knowledge there has been no research on these as a barrier to home cooking in apartments.

Many participants had modified physical aspects of their kitchen environment to enable them to continue home cooking, such as using non-kitchen areas for storage, purchasing or building extra storage and kitchen benches. However, this was not always possible due to the cost involved, or in the case of ventilation for example, not being able to alter inherent design. When modifications were not possible, residents had to adjust what they ate e.g. not cooking eggs, fresh meat and fish because of lingering smells and fire alarm activation, not baking or cooking ‘complicated meals’. This is particularly significant, given that the foods avoided by apartment-dwellers in our study are those recommended for regular consumption in the current Australian Dietary Guidelines. Our findings also add to previous research (Hagejärd et al. Citation2020), which noted unsuitable kitchen preparation areas and storage impeded the use of vegetables in meals. Further, another study found that poor domestic kitchen design can make cooking unsafe and no longer enjoyable for older residents (Forlizzi et al. Citation2004). Taken together, these findings suggest that poor apartment kitchen designs, which act as disincentives to food preparation are a public health concern, given the health benefits of home cooking (Wolfson et al. Citation2020).

Turning to the more distal interrelationships between apartment kitchen design and food practices, our study reveals several examples of societal-level influences on kitchen design, which may impact on apartment dwellers’ food practices. Aligning with recent assumptions that apartment dwellers in locations surrounded by dining and takeaway opportunities may not be interested in home cooking (Malinowski Citation2015, Bestard Citation2016), participants in our study described viewing apartments for sale and rent in Melbourne which had kitchens that would not support home cooking. Furthermore, the observation that storage design was particularly challenging for a less physically able participant in the current study, supports the contention that apartment development in Australia has been aimed at an imagined demographic of able people, transitioning to single dwellings (Fincher Citation2007), rather than providing permanent homes for a diversity of residents (Whitzman and Mizrachi Citation2012).

Apartment kitchen design is also a product of the policy environment. Initially, the boom in Australian apartment construction from the early 2000s occurred in a policy vacuum (Fincher Citation2007). Specific apartment design guidelines have only been developed in the past five years and even then, they are limited. In Victoria, guidelines on kitchen design are restricted to recommendations on providing ‘kitchen layouts with sufficient space for cooking, cleaning, food preparation and storage’ (The State of Victoria Department of Environment Land Water & Planning Citation2021). There is no detail on ‘sufficient space’, or the specific design of kitchen storage or cooking areas. Furthermore, our research suggests the need to consider universal design policy in the context of kitchen design guidelines. Here, there is some evidence with regards to design features that could be included to support a wider diversity of apartment dwellers. For example, one study outlines five criteria for the universal design of kitchens (Kang and Lee Citation2016), while another, a range of practical design features to support food practices for elderly residents (Maguire et al. Citation2014). Despite these latter examples, our findings indicate significant gaps in evidence-based kitchen design policy to support home cooking, for the growing diversity of apartment-dwellers in countries such as Australia. These gaps are also highlighted in recent research exploring international policy on apartment design, albeit targeted specifically to families with children (Andrews et al. Citation2021) as well as a recent scoping review on kitchen design and home food practices (Sal Moslehian et al. Citation2023).

Limitations and further research

Our paper provides a unique insight into the interrelationship between apartment kitchen design and food practices from the perspective of a diverse group of 12 apartments dwellers in Melbourne. As qualitative research, it sought to understand the detail of participants’ lived experiences and was not designed to provide findings generalisable to all apartment-dwellers. Insights thus form the basis not of policy recommendations but of further research. Such research might be undertaken to explore these issues more broadly with a larger sample or specific groups and perhaps be more systematically connected to particular suburban areas, socio-economic or demographic cohorts or different regulatory regimes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our research has identified the choices, challenges and changes that form the basis of the interrelationships between apartment kitchen design and food practices, for a group of apartment dwellers in Melbourne. Through the application of a socioecological lens, these experiences were discussed within the broader contexts of societal expectations regarding apartment living and the broader policy environment. As there was a paucity of research on this topic, ours was a small exploratory study to identify key concerns and thus further research is required to provide a stronger evidence base, on which to inform future policy development. Given the growing trend in apartment-living, there is a pressing need to develop this evidence base to support healthy food practices among existing and future residents.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the work of Stephanie Rich who interviewed the participants in this study and the participants themselves, for their time taken contributing to our research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fiona J. Andrews

Fiona J. Andrews is an Associate Professor and Co-leader of HOME, a Strategic Research and Innovation Centre at Deakin University. Her research is concerned with understanding the relationship between the built environment and health, aiming to inform housing and neighbourhood design that better supports wellbeing. She is particularly interested in residents’ lived experiences of the design of their homes and hence uses qualitative methodologies, having developed specific expertise in photo-narrative methods. Her research has helped inform both local and state government housing policy.

Louise C. Johnson

Louise C. Johnson is a human geographer and Honorary Professor at Deakin and Melbourne Universities. She taught for 45 years in Australian and New Zealand universities and has a solid record of research, policy development and community activism. She has researched Geelong’s textile and creative industries and socio-spatial disadvantage and published extensively on Australian cities, planning and suburbs producing six books and over 120 articles and chapters. In 2011 she received the Institute of Australian Geographers Australia and International Medal in recognition of her contribution to urban, social and cultural geography.

Ralph Horne

Ralph Horne is a geographer interested in urban sustainability, in particular, low carbon transitions in housing and households. The spatial, material and contingent social and policy structures at play are the main focus of his work on both the making and shaping of urban environments. He is also Associate Deputy Vice Chancellor, Research and Innovation for the College of Design and Social Context at RMIT University. He combines research leadership and participation in research projects concerning the environmental, social and policy context of production and consumption in the urban environment.

Lukar E. Thornton

Lukar E. Thornton is an Assistant Research Professor within the Department of Marketing at the University of Antwerp, Belgium. He previously studied and worked in Australia and has 20 years of experience in the collection and analysis of geospatial, quantitative and qualitative data related to social and environmental influences on health behaviours.

References

- Andrews, F.J., et al., 2021. Best practice design and planning guidelines for family-friendly apartments. Urban policy & research, 41 (2), 164–181. doi:10.1080/08111146.2022.2146669.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2021. Census of population and housing: housing census.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2019. Australian burden of disease study: impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2015. In: Australian Burden of disease series no. 19. Cat. no. BOD 22. Canberra: AIHW.

- Bestard, C., 2016. The “kitchenless” house: a concept for the 21st Century. Arch daily, 17 (8). https://www.archdaily.com/793370/the-kitchenless-house-a-concept-for-the-21st-century.

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V., 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3 (2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Brug, J., 2008. Determinants of healthy eating: motivation, abilities and environmental opportunities. Family practice, 25 (Supplement 1), i50–i5. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmn063.

- Comber, R., et al., 2013. Food practices as situated action: exploring and designing for everyday food practices with households. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems. Paris, France. 2481340: ACM, 2457–2466.

- Dunn, K., Andrews, F.J., and Warner, E., 2021. The cooking and eating experiences of Australian families with children, living in private, inner-city, high-rise apartments. Housing & society, 50 (1), 70–89. 19 Oct 2021: doi:10.1080/08882746.2021.1989858.

- Fincher, R., 2007. Is high-rise housing innovative? Developers’ contradictory narratives of high-rise housing in Melbourne. Urban Studies, 44 (3), 631–649. doi:10.1080/00420980601131894.

- Forlizzi, J., DiSalvo, C., and Gemperle, F., 2004. Assistive robotics and an ecology of elders living independently in their homes. Human–computer interaction, 19 (1–2), 25–59.

- Foster, S., et al., 2020. The high life: a policy audit of apartment design guidelines and their potential to promote residents’ health and wellbeing. Cities. 96. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2019.102420.

- Hagejärd, S., et al., 2020. Designing for circularity—addressing product design, consumption practices and resource flows in domestic kitchens. Sustainability, 12 (3), 1006. doi:10.3390/su12031006.

- Hansen, E.C., 2020. Successful qualitative health research: a practical introduction. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin, 2006.

- Harper, D., 2002. Talking about pictures: a case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies, 17 (1), 13–26. doi:10.1080/14725860220137345.

- Kang, K.-Y. and Lee, K.-H., 2016. Application of universal design in the design of apartment kitchens. Journal of Asian architecture and building engineering, 15 (3), 403–410. doi:10.3130/jaabe.15.403.

- Lachal, J., et al., 2012. Qualitative research using photo-elicitation to explore the role of food in family relationships among obese adolescents. Appetite, 58 (3), 1099–105. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2012.02.045.

- Le Bel, J.L. and Richman Kenneally, R. 2009. Designing meal environments for ‘mindful eating‘. In: H.L. Meiselman, ed. Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition, Meals in Science and Practice. Woodhead Publishing, 575–593. doi:10.1533/9781845695712.8.575.

- Maguire, M., et al., 2014. Kitchen living in later life: exploring ergonomic problems, coping strategies and design solutions. International journal of design, 8 (1), 73–91.

- Malinowski, S.D.C., 2015. Developer bets big on apartments with shared eating spaces. The Washington Post, 28 Apr. Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/where-we-live/wp/2015/04/28/d-c-developer-bets-big-on-apartments-with-shared-eating-spaces/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.4ecfe1b27940.

- Marquis, M. and Manceau, M., 2007. Individual factors determining the food behaviours of single men living in apartments in montreal as revealed by photographs and interviews. Journal of youth studies, 10 (3), 305–16. doi:10.1080/13676260701216158.

- Mills, S., et al., 2017a. Home food preparation practices, experiences and perceptions: a qualitative interview study with photo-elicitation. Public library of science ONE, 12 (8), e0182842–e. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0182842.

- Mills, S., et al., 2017b. Health and social determinants and outcomes of home cooking: a systematic review of observational studies. Appetite, 111 (1), 116–134. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2016.12.022.

- Mills, S.D.H., et al., 2020. Perceptions of ‘home cooking’: a qualitative analysis from the United Kingdom and United States. Nutrients, 12 (1), 198. doi:10.3390/nu12010198.

- O’Connell, R., 2013. The use of visual methods with children in a mixed methods study of family food practices. International journal of social research methodology, 16 (1), 31–46. doi:10.1080/13645579.2011.647517.

- Oliver Hume Corporation Pty Ltd, 2015. Melbourne new apartment sizes shrinking again. 11 Feb. Available from: https://www.oliverhume.com.au/about/media/melbourne-new-apartment-sizes-shrinking-again/.

- Ollar, A., et al., 2022. Is there a need for new kitchen design? Assessing the adaptative capacity of space to enable circularity in multi-residential buildings. Frontiers architectural research, 11 (5), 819–916. doi:10.1016/j.foar.2022.03.009.

- Olstad, D.L. and Kirkpatrick, S.I., 2021. Planting seeds of change: reconceptualizing what people eat as eating practices and patterns. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity, 18 (1), 32. doi:10.1186/s12966-021-01102-1.

- Oostenbach, L.H., et al., 2021. The role of dwelling type on food expenditure: a cross-sectional analysis of the 2015-2016 Australian household expenditure survey. Public health nutrition, 24 (8), 2132–2143. doi:10.1017/S1368980020002785.

- Pain, H., 2012. A literature review to evaluate the choice and use of visual methods. International journal of qualitative methods, 11 (4), 303–319. doi:10.1177/160940691201100401.

- Pitt, E., et al., 2017. Exploring the influence of local food environments on food behaviours: a systematic review of qualitative literature. Public health nutrition, 20 (13), 2393–405. doi:10.1017/S1368980017001069.

- Privitera, G.J. and Creary, H.E., 2013. Proximity and visibility of fruits and vegetables influence intake in a kitchen setting among college students. Environment & behavior, 45 (7), 876–886. doi:10.1177/0013916512442892.

- Sal Moslehian, A., Warner, E., and Andrews, F.J., 2023. The impacts of kitchen and dining spatial design on cooking and eating experience in residential buildings: a scoping review. Journal of housing and the built environment, 38 (3), 1983–2003. doi:10.1007/s10901-023-10027-z.

- Sandelowski, M., 2000. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in nursing & health, 23 (4), 334–40. doi:10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334:AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G.

- The State of Victoria Department of Environment Land Water & Planning, 2021. Apartment design guidelines for Victoria.

- Stokols, D., 1992. Establishing and maintaining healthy environments. Toward a social ecology of health promotion. The American psychologist, 47 (1), 6–22. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.47.1.6.

- Story, M., et al., 2008. Creating healthy food and eating environments: policy and environmental approaches. Annual review of public health, 29 (1), 253–72. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090926.

- Thornton, L., et al., 2022. Pie in the sky: exploring food practices amongst those living in apartments within Melbourne, Australia. Cities & health, 6 (4), 667–70. doi:10.1080/23748834.2020.1774955.

- United Nations, 2019. World urbanization prospects. 2018 revisions. New York: United Nations.

- Vaughn, A.E., et al., 2013. Measuring parent food practices: a systematic review of existing measures and examination of instruments. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity, 10 (1), 61. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-10-61.

- Warner, E.F., Johnson, L., and Andrews, F.J., 2016. Exploring the suburban ideal: residents’ experiences of photo elicitation interviewing (PEI). International journal of qualitative methods, 15, 1–9.

- Whitzman, C. and Mizrachi, D., 2012. Creating child friendly high-rise environments: beyond wastelands and glasshouses. Urban policy & research, 30 (3), 233–249. doi:10.1080/08111146.2012.663729.

- Wolfson, J.A., Leung, C.W., and Richardson, C.R., 2020. More frequent cooking at home is associated with higher healthy eating index-2015 score. Public health nutrition, 23 (13), 2384–2394. doi:10.1017/S1368980019003549.