ABSTRACT

In light of rapid global urbanization and development, planners have become more concerned with the quality of life in cities. However, the perceptual connections between the built environment and resident well-being deserve more systematic attention. This study investigates the relationship between the perceived physical and social features of the neighborhood environment and the health-related quality of life for 393 adult residents in Tehran, Iran. A questionnaire was developed to examine participants’ perceptions of neighborhood social and physical factors, along with the World Health Organization’s Quality of Life – Brief Form (WHOQOL – BREF) to measure their health-related quality of life. Using factor analysis, correlations, and multiple linear regressions, the findings suggest that all subcomponents of the physical environment (accessibility, amenity, and legibility) and social environment (participation, sense of community, and satisfaction) impact psychological, social relationships, and environmental health, but that amenities were most powerfully predictive of all three types of socio-environmental health.

Introduction

Understanding the multifaceted determinants of health-related quality of life (QOL) has long been the pursuit of numerous studies globally due to its link with significant outcomes such as overall well-being, productivity, longevity, and healthcare cost (Doumit and Nasser Citation2010, Carta et al. Citation2012). The escalating interest in QOL is largely influenced by the realization that it transcends physical health, encompassing psychological, social, and environmental domains defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) (WHO Citation2012). The physical health domain encompasses the functionality of an individual’s body and overall feeling of wellness. The psychological state domain relates to an individual’s emotional well-being, including positive and negative feelings, and the ability to think, learn, and concentrate. Social relationships cover the quality and depth of an individual’s personal connections, social support systems, and engagement with their community. Lastly, the environmental factors domain considers the impact of the living space, safety, access to healthcare, and a clean environment on an individual’s quality of life (WHO Citation2012). Researchers have mapped various factors – ranging from physical health status, and environmental elements, to social relations – that significantly impact QOL (Kawachi and Berkman Citation2000, Long and Perkins Citation2007, Cao Citation2016). Furthermore, the urbanization processes and fast population growth underline the urgency to address QOL within the urban planning perspective, acknowledging its crucial role in enhancing not just the built environment but the overall well-being of urban dwellers (Mouratidis Citation2021).

Despite the substantial amount of research on QOL, certain areas remain understudied or exhibit a lack of context-specific research such as the influence of the neighborhood environment on health-related QOL (HRQOL) (Ellen et al. Citation2001). Incorporating insights from Iranian studies, our research further distinguishes itself in the context of Iran’s unique urban and social fabric. Previous investigations within Iran have primarily focused on narrow aspects of quality of life (QoL) such as the conceptualization of QoL in the elderly (Hasani et al. Citation2012, Cheraghi et al. Citation2016), the relationship between diseases and QoL, and the effects of physical exercises on QoL (Arastoo et al. Citation2012). For instance, Ghasemi et al. (Citation2019) explored the relationship between urban poverty, perceived family socioeconomic status, and HRQOL in informal settlements, finding no significant direct correlation between poverty levels and HRQOL. Nedjat et al. (Citation2011) conducted a study assessing the subjective QoL within a general Iranian population utilizing the WHOQOL-BREF, discovering low QoL scores significantly influenced by socio-demographic variables. Rezvani et al. (Citation2013) explored QoL in Noorabad, Iran, through subjective and objective indicators, uncovering diverse satisfaction levels across life domains, notably high satisfaction with housing and low satisfaction with employment and environmental conditions. Soleimani et al. (Citation2014) investigated QoL in Tehran’s Darvazeshemiran neighborhood, highlighting that despite benefits like job access and facility proximity, the absence of green spaces and poor housing conditions significantly detracted from overall QoL. Khaef and Zebardast (Citation2016) focused on QoL in Tehran’s deteriorated Javadieh neighborhood, identifying traffic, housing, and infrastructure as critical factors influencing residents’ life satisfaction.

This research contributes to the existing literature by addressing several key gaps identified through a comprehensive literature review. Firstly, unlike many studies that predominantly focus on the elderly population (Bodur and Dayanir Cingil Citation2009, Hasani et al. Citation2012, Cheraghi et al. Citation2016, Tiraphat et al. Citation2017, Khosravi and Tehrani Citation2019, Zhang et al. Citation2019), our research encompasses a broader demographic by covering individuals of various ages living in an urban neighborhood in Tehran, Iran thereby offering a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of neighborhood environments on HRQOL. Secondly, our study stands out by examining both the social and physical aspects of the neighborhood environment and their combined effects on HRQOL moving beyond the singular focus prevalent in previous studies (Grasser et al. Citation2013, Khaef and Zebardast Citation2016, Habibi and Zebardast Citation2018, Yazdanpanah Shahabadi and Sajadzadeh Citation2020). Although several studies have recognized the importance of neighborhood variables, there is a paucity of research that holistically investigates the intersection of various physical and social neighborhood factors (Kawachi and Berkman Citation2000, Heo et al. Citation2020). More often, research tends to focus on single facets of the environment, neglecting the complex interplay of numerous factors within the neighborhood context (Slater et al. Citation2020). Third, this study covers a diverse range of health aspects, including mental, environmental, and social relationship health, to provide a more nuanced understanding of HRQOL determinants. This comprehensive approach addresses the limitations of prior research that often focused on singular health aspects, such as mental or physical health, without considering the multifaceted nature of HRQOL (Frank et al. Citation2005, Olsen et al. Citation2017, An et al. Citation2020). This research explores the influence of social and physical neighborhood conditions on HRQOL dimensions in Tehran and aims to provide insights applicable to similar urban areas in the Middle East and Central Asia, regions that have not been as extensively studied as cities in the West.

Physical environment and quality of life

The physical environment appears to affect well-being and quality of life, described as a person’s capacity to operate efficiently in daily life and subjective well-being in terms of mental, social, and physical health (Killewo et al. Citation2010, Fox and Powell Citation2023). Studies utilizing the WHOQOL-BREF measure have established the influence of neighborhood characteristics on QOL. For instance, Wang et al. (Citation2018) emphasize the critical role of environmental satisfaction, including green spaces, recreational amenities, air and noise quality, safety, and walkability. Further research by Shepherd et al. (2021) demonstrates that residents’ perceptions of neighborhood amenities, such as access to health facilities, public transport, parks, and street lighting significantly affect Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL), linking positive perceptions to higher HRQOL scores. Similarly, using the WHOQOL-BREF instrument, Erin et al. (Citation2012) explored the impact of neighborhood issues like odors, noise, and vandalism on HRQOL among New Zealanders, highlighting how these environmental factors notably affect physical, psychological, and social well-being.

Studies highlighted the importance of neighborhood planning and design in the quality of parks and open spaces, public gathering places, accessibility, mixed housing, and street connectivity (Deitrick and Ellis Citation2004, Cao Citation2016). A Dutch study found that the physical characteristics of a neighborhood, such as building quality, noise, and traffic, are significantly associated with all four QOL components including physical, psychological, social, and environmental domains (Gobbens and van Assen Citation2018). In terms of accessibility, public transportation, street connectivity, and the distance and degree to which destinations such as stores, schools, and local health services can be reached in direct rather than indirect pathways are important factors in increasing the use of local spaces and improving resident’s well-being (Stafford et al. Citation2007, Sugiyama et al. Citation2009).

Perceptions of public open space and built environment are critical components of neighborhood, health, and quality of life assessments (Sugiyama et al. Citation2009, Gobbens and van Assen Citation2018). Neighborhood public spaces provided with recreation facilities such as bicycle lanes, walking paths, and swimming pools promote physical activity (Ferrans et al. Citation2005), and contribute to a better overall attitude of the community (Shields and Shooshtari Citation2001). In addition, accessible physical settings that help residents meet their needs within their surrounding area increase individuals’ well-being. Biagi et al. (Citation2018) found that different neighborhood amenities correlate with convenience and are tied directly to the residential QOL. Specifically, the study distinguished between manmade amenities – such as educational, health, and transport services, along with cultural facilities – and environmental or natural amenities, highlighted by the presence of public green spaces and coastal access (referred to as green and blue amenities, respectively). Within this framework, residential QoL is assessed through the lens of capabilities and functionings; it considers the availability of these amenities (capabilities) and the extent to which residents engage with them (functionings), thus providing a nuanced understanding of how amenities impact the lived experiences and well-being of community members. Green space in urban environments reflects an environmental commitment to increase the QOL and promote a sustainable lifestyle in cities (Rautio et al. Citation2018). Green spaces provide urban residents with access to nature and scenic views resulting in improved physical, mental, and environmental health (White et al. Citation2013, Lawrence et al. Citation2019) and negatively associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression (van den Berg et al. Citation2016)

Objective indicators of urban settings (such as neighborhood quality, parks, and mixed housing) have been linked to mental health (Gong et al. Citation2016, Zhang et al. Citation2023). Public spaces and building design can influence emotional reactions. Attractive public places and aesthetically pleasing architecture are associated with an immediate increase in joyful experiences and improved mental health (Bond et al. Citation2012, Seresinhe et al. Citation2019). Modern architecture – defined by asymmetry, a lack of decoration, and an industrial appearance, can result in a poor evaluation of the physical environment and negative emotional responses (Zhang and Lin Citation2011).

Social environment and quality of life

Social factors are also associated with neighborhood and health. Several studies show that social ties, support, and collective participation substantially influence well-being at both the individual (Long and Perkins Citation2007, Gu Citation2020, Amoah and Adjei Citation2023, Scavarda et al. Citation2023) and even the national level (Perkins et al. Citation2021). Social support is positively associated with well-being as it protects an individual from the negative consequences of stressful events by providing positive experiences and a feeling of consistency (Cohen and Wills Citation1985). Individuals with negative perceptions of social support appear to develop more severe mental health problems with more disease outcome symptoms than those with positive perceptions of their social network (Wang et al. Citation2018).

Neighborhood social cohesion, described as cooperation, responsiveness, and connectivity among individuals, fosters interpersonal relationships, which results in well-being and quality of life (Berkman and Kawachi Citation2000). It has been suggested that social relationships and group membership are insufficient to preserve social cohesiveness. Social ties built on mutual trust and control are directed toward specific outcomes, such as keeping public order (Sampson Citation2003). In a residential context where trust and reciprocity are prevalent, it is assumed that relationships between friends and neighbors would be characterized by decent social interactions rather than negative ones. A neighborhood’s social cohesiveness may be related to a reduced prevalence of depression symptoms via more positive social interactions with neighbors (Szreter and Woolcock Citation2004, Scheffler et al. Citation2007).

Higher neighborhood social cohesion is associated with greater social participation (Bowling and Stafford Citation2007, Richard et al. Citation2009). Social participation is described as an individual’s engagement in social activities such as religious, leisure activities, volunteering, political organizations, and voting that facilitate social connections within a community (Bukov et al. Citation2002, Levasseur et al. Citation2010). Social participation is commonly found to improve physical health (James et al. Citation2011), subjective wellbeing (Potočnik and Sonnentag Citation2013, Perkins et al., Citation2021), and mental health (Araya et al. Citation2006). Social engagement supports health by buffering the detrimental consequences of social isolation (Kawachi and Berkman Citation2000). A person living in a neighborhood with little chance for social involvement may have few opportunities to create social solidarity and become socially isolated (Kawachi and Berkman Citation2000). Low social involvement is connected with higher mortality, indicating that individual lifestyle and psychological resources are at least as crucial to health as social support (Araya et al. Citation2006).

A sense of community is a social element connected with various health factors, including well-being and quality of life (Michalski et al. Citation2020). A sense of community relates to values and beliefs about neighbors and the neighborhood (McMillan and Chavis Citation1986), including being aware of community members’ views and feelings surrounding their experiences and interactions in their everyday community setting (Elvas and Moniz Citation2010).

Strong community bonds enhance psychological well-being (Michalski et al. Citation2020) while a lack of it can lead to poorer problem‐focused coping and loneliness (Deckx et al. Citation2018).

Current study

This study was designed to address the identified gaps in the existing literature by examining how physical and social neighborhood characteristics relate to health-related quality of life among residents of an urban neighborhood in Tehran, Iran. In this context, we propose that an individual’s social, psychological, and environmental health domains will demonstrate a positive association with factors such as accessibility, legibility, and availability of amenities in the physical context, and with participation, sense of community, and satisfaction within the neighborhood’s social environment.

Methods

Study setting

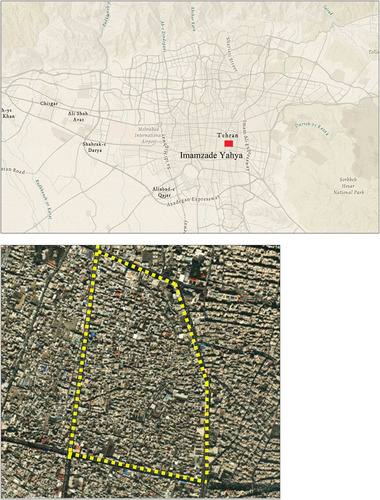

This study targets adults living in one neighborhood located in District 12 of Tehran, Iran (). Most of the neighborhood is used for residential purposes. In 2011, 14024 people across 3833 households resided in this area within an area of around 68 hectares (Ebrahiminia Citation2019). The average household size was 3.6 persons, the gender ratio was 117.7 females per 100 males, and the unemployment was 3.7%. The neighborhood’s high population density, indicative of residents’ relative poverty reflected in their monthly income, has led to several social issues (Arabi et al. Citation2020). These include insufficient facilities, resources, services, and overall welfare due to overcrowding. The area is also marked by instability and a lack of community attachment, evidenced by the relocation of long-standing residents and a substantial influx of immigrants and single-person households.

The neighborhood’s built environment features narrow roads that preclude internal public transportation, yet it is well-connected to the city’s broader transit network, with taxi and bus services available on all four sides and two metro stations accessible from the north. The main thoroughfare, Yahya Ammazadeh Street, varies in width from 5 to 10 meters and runs north-south, with surrounding streets typically narrower than 6 meters and organically developed. Despite being one of Tehran’s oldest urban areas and embodying the city’s historical core, the neighborhood lacks pedestrian-friendly infrastructure such as sidewalks and crossings (). This context, reflecting a blend of historical significance and modern-day challenges, underscores the complexities of urban living and the critical need for targeted improvements to enhance residential QOL in densely populated areas.

Study population and procedures

The first author conducted the recruitment process for adult participants, utilizing a convenience sampling approach from October to November 2017, operating between 9 a.m. and 7 p.m. on weekdays. Recruitment occurred in person and onsite within the neighborhood. Prospective participants all of whom were required to be at least 18 years old and residents of the neighborhood, were introduced to the study focusing on residents’ perceptions of their neighborhood’s social and physical environments and their overall quality of life. The researcher clarified the aim of the research, and participants’ ability to withdraw at any time, and ensured the procurement of informed consent. Upon agreeing to participate, individuals were provided with self-administered survey questionnaires to be completed on paper, and onsite. In certain cases, when the participant was illiterate or elderly and preferred an interview, the researcher carried out the process using the same questionnaire. Our study aimed to engage 393 respondents, a number determined based on the neighborhood population and Cochran’s sampling formula (Cochran Citation1991), considering a maximum acceptable error (d = 0.05), a confidence level (z = 1.96), and (p and q = 0.5). While selecting participants, the study prioritized inclusivity across a range of socio-demographic features, ensuring that all participants were at least 18 years old and residents of the neighborhood. This approach facilitated a comprehensive understanding of the neighborhood’s environmental health and perceptions from a diverse cross-section of the community. This study received ethical approval from the designated committee at Iran University of Science and Technology.

Measures

Outcome

Each participant completed the World Health Organization Quality of Life – Brief Form (WHOQOL – BREF) to quantify their overall quality of life. The WHOQOL-BREF is a valid and reliable measure of health-related quality of life (Ohaeri and Awadalla Citation2009, Kalfoss et al. Citation2021). It was adapted from a longer broad-based subjective assessment of the quality of life that was created to apply to persons living in various cultures and settings (WHO Citation2012). This study used data about three QoL domains which were assessed via multiple questions all using a five-item Likert-type response scale. Psychological health QoL was represented by 6 items (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.7), which represented body image and physical appearance, self-esteem, attention, positive and negative emotions, and personal beliefs. Social health QoL was represented by 3 items (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.66), which represented social support, sexual activity, and personal relationships. Environmental health QoL was represented by 7 items (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85), which represented safety and physical security, access to health and social care, financial resources, participation in and possibilities for recreation and transportation, and opportunities for acquiring new information and skills. Higher scores indicated a greater degree of QoL.

Explanatory factors

Demographic profiles of the participants such as age, gender, education, length of residency in the neighborhood, and home ownership status were collected. In addition, participants were asked to respond ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to a series of questions aimed at capturing their perceptions of both the physical and social aspects of their neighborhood environment. For the physical environment, the questionnaire inquired: “Is the sidewalk width suitable for walking comfortably?’ ‘Are grocery stores conveniently close to your residence?’ ‘Are public places like libraries and mosques easily accessible from your residence?’ ‘Are public spaces such as parks close to your residence?’ ‘ Are there greenery elements like trees and plants in your neighborhood?’ ‘Are trash bins readily available in your neighborhood?’’ Is there flexibility in the arrangement or placement of park seats?’ ‘Are benches available in your neighborhood?’ ‘Is the neighborhood well-maintained and clean?’ ‘Is it easy to find destinations within your neighborhood?’ and ‘Does your neighborhood have a distinctive appearance?’

Similarly, for the social environment, participants were questioned about their community engagement and interpersonal relationships: ‘Have you participated in voting for local decisions?’ ‘Have you engaged in collective decision-making in your neighborhood?’ ‘Have you participated in local rituals or community events?’ ‘Do you enjoy living in your neighborhood?’ ‘Do you feel a sense of belonging to your community?’ ‘Do you feel a strong sense of connection with your neighbors?’ ‘Do you visit your neighbors?’ ‘Do you trust your neighbors?’ ‘Are you interested in moving from your neighborhood?’ ‘Are you satisfied with your neighbors?’ ‘Have you experienced mistreatment by your neighbors?’ and ‘Do you feel safe in your neighborhood at night?’

The physical and social dimensions of the neighborhood were explored through the factors below:

Accessibility

To understand the physical accessibility of the neighborhood, our questionnaire included items on sidewalk width, and proximity to grocery stores, libraries, mosques, parks, and public spaces. This factor assesses how easily residents can navigate and access essential services within their neighborhood (Cronbach’s alpha = .66).

Amenities

We explored the availability of amenities through questions on the presence of greenery elements (trees and plants), trash bins, park seat arrangements, and benches. This factor evaluates the quality and accessibility of neighborhood amenities that contribute to residents’ quality of life (Cronbach’s alpha = .66).

Legibility (navigation & distinction)

Questions about the ease of finding destinations and the distinctiveness of the neighborhood’s appearance were used to assess legibility. This factor focuses on how navigable the neighborhood is and whether it has a unique and distinguishable character (Cronbach’s alpha = .73).

Community participation

The survey addressed community engagement through questions about residents’ participation in local decisions, collective decision-making, and community events. This factor aims to capture the extent of residents’ involvement in their neighborhood’s social life, reflecting the active role they play within their community (Cronbach’s alpha = .72).

Sense of community

We assessed residents’ sense of belonging and connection with their neighbors through queries about trust, belongingness, relations among community members, and interest in moving from the neighborhood. This factor is crucial for understanding the emotional and relational aspects of neighborhood life, highlighting how residents feel about their community (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.71).

Neighborhood satisfaction

Questions related to residents’ satisfaction, including their happiness and contentment with their neighborhood, and feeling of safety, helped to gauge overall neighborhood satisfaction. This factor considers residents’ contentment with their living environment (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.54).

The indicators selected for the physical dimension, including aspects such as sidewalk width, access to essential services, public spaces, presence of greenery elements (trees and plants), and overall neighborhood maintenance, were chosen for their proven impact on enhancing accessibility, safety, recreation, and aesthetic appeal, all of which are essential for the health and well-being of urban residents (Sugiyama et al. Citation2009, Khosravi and Tehrani Citation2019, Lawrence et al. Citation2019). Similarly, the social dimension indicators – encompassing community participation, relationships, sense of belonging, neighborhood satisfaction, and safety – were designed to delve into the core elements of urban social fabric and capital, crucial for mental health and community resilience. Both physical and social indicators have been utilized in various studies to measure the health and quality of life among residents, demonstrating their effectiveness in capturing the multifaceted experiences and perceptions that contribute to urban living quality (Sugiyama et al. Citation2009, Rezvani et al. Citation2013, Khaef and Zebardast Citation2016, Khosravi and Tehrani Citation2019, Zhang and Li Citation2019, Zhang et al. Citation2019).

Approach to data analysis

First, descriptive statistics (frequency, mean, standard deviation) regarding typical respondent sociodemographic characteristics and housing features were calculated. Second, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to investigate the underlying structure of the relationship between 11 items about the physical environment and 12 items about the social environment, due to the large number of measured variables assumed to be related to a smaller number of unobserved factors. Given the binary nature of these survey items, a tetrachoric correlation matrix was employed to accurately estimate the correlations between the dichotomous variables and to ensure that the assumptions necessary for correlation analysis with binary data are met (Bandalos and Finney Citation2019) (Appendix A). Varimax rotation was applied to the extracted factors to enhance the interpretability of the factor structure by maximizing the variance of the squared loadings of a factor across the variables, thereby simplifying the understanding of the relationships among the items.

Bivariate correlations and hierarchical multiple linear regression analyses were then used to evaluate the relationship between all physical and social factors of the neighborhood environment and different health domains. The bivariate linear associations of independent variables (sociodemographic and neighborhood social and physical factors) among each other and with the outcome variables (three health domains) were investigated using Pearson correlation matrices. Three sets of hierarchical multiple linear regressions were employed to estimate the effect of physical and social environment separately and their combination on the respondents’ each environmental, social, and mental health domains.

In each model, the first step of the hierarchical regression included housing ownership as a control variable. For the first model, neighborhood physical features were introduced in the second step. In the second model, social factors including community participation, sense of community, and satisfaction were added in the second step. The third model comprised both physical and social factors in the second step.

Results

Study population

The survey collected data from 393 residents with a response rate of 77% percent. Females made up the majority (54%) of the participants. Forty-eight percent of the respondents were undergraduates, and the mean age was 36.88 (SD = 12.81) (). Nearly 44% had lived in the neighborhood for more than 20 years, and 51% were homeowners. Around 39% lived in an apartment with an area of 60-90 square meters. The mean household size was 4.01 (SD = 1.24).

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of adult residents of Imamzadeh Yahya (N = 393).

Factor analysis and reliability test

Cronbach’s alpha values for physical environment items (α = .68) and social environment items (α = .67) indicated an acceptable level of reliability. The appropriateness of the selected variables for relevant indicators in the surveys was determined using Bartlett’s sphericity test and the Kaiser – Meyer – Olkin (KMO) sampling adequacy measure. Bartlett’s Sphere Test for physical environment items (KMO= .76, sig. = 0.000) and social environments items (KMO= .60, sig. = 0.000) indicated that the construct validity and variance of the measures were adequate across all categories ().

Table 2. Factor analysis of physical environment features (sig. Of Bartlett’s Sphere Test < 0.001, KMO value = 0.60).

Table 3. Factor analysis of social environment features (sig. Of Bartlett’s Sphere Test < 0.001, KMO value = 0.76).

Three distinct categories were represented within the physical environment construct and also within the social environment construct. For the physical environment, after Varimax rotation, the first component had an eigenvalue of 2.26, accounting for 21% of the variance. The second component had an eigenvalue of 2.16, explaining 20% of the variance, and the third component had an eigenvalue of 1.6, accounting for 15% of the variance. Cumulatively, these three components explained 56% of the total variance. For the social environment, the three components accounted for a cumulative variance of 51%. Specifically, the first component had an eigenvalue of 2.28, explaining 19% of the variance; the second component had an eigenvalue of 2.18, accounting for 18% of the variance; and the third component had an eigenvalue of 1.72, explaining 14% of the variance.

For the physical environment (), the pattern matrix revealed factor one (α = .66) to consist of four items: sidewalk width, access to stores, parks, public spaces, and services across the neighborhood. This factor was identified as accessibility and reflected a high internal consistency. The second factor (α = .66) with five items was labeled amenities, and the last factor (α = .73) with two items relating to the neighborhood navigation and distinction was named legibility.

For the social environment (), the first factor (α = .72) contained three components related to neighbors’ participation in voting, collective decision-making, and social events and was called community participation. The second factor (α = .71) was made up of five items, including trust, a sense of belonging, and a strong sense of connection among residents, which was labeled sense of community. The last factor (α = .54), neighborhood satisfaction, consists of four items concerning general residents’ happiness and contentment with the neighborhood.

Table 4. Correlation between social and physical factors and environmental health in Imamzade Yahya neighborhood residents.

Correlation and multiple linear regression analysis

Pearson correlation analysis indicated significant positive correlations between different aspects of the neighborhood’s physical and social environment and residents’ health. Psychological health, environmental health, and social relationship health each demonstrated positive correlations with various factors such as amenities, accessibility, legibility, satisfaction, sense of community, and community participation. It is noteworthy that homeownership was the only housing characteristic correlated across all three health domains. As anticipated, the analysis uncovered modest intercorrelations among several explanatory variables. Notably, community participation was found to correlate with the sense of community, and both of these factors, along with neighborhood satisfaction and accessibility, showed significant correlations with amenities. Despite these intercorrelations, the analysis confirmed that all predictor variables function as discrete and valid constructs, underlining the complexity of factors that contribute to residents’ quality of life in urban environments (see ).

The effects of the physical and social environment, as well as their combination, on the three health domains of environmental, social, and mental health, were scrutinized through three distinct sets of hierarchical multiple linear regression models. Each regression had homeownership introduced at the initial step as a control variable, due to its observed correlation with all three health domains. Other variables such as Age, gender, education, and length of residency were not included in the regression analysis due to a lack of significant correlation.

For environmental health, physical neighborhood features notably explained 24% of the variance in the second model, with the amenities (β = 0.365 p < .001), accessibility (β = 0.187 p < .001), and legibility (β = 0.151 p < .001) each providing significant contributions. The separate social environment model also yielded significant results, with neighborhood satisfaction (β = 0.231 p < .001), and sense of community (β = 0.182, p < .001) being the predictors. The combined social and physical environment model contributed to 27% of the variation in predicting environmental health ().

Table 5. Social and physical factors predicting environmental health of Imamzade Yahya neighborhood residents.

Turning to psychological health, amenities (β = 0.231 p < .001) and accessibility (β = 0.127 p < .05) were found to mediate their relationship with perceived physical neighborhood characteristics. Meanwhile, neighborhood satisfaction (β = 0.169 p < .001) emerged as the only significant predictor in the social factors model. The combination of physical and social factors explained 11% of the variation in mental health ().

Table 6. Social and physical factors predicting psychological health of Imamzade Yahya neighborhood residents.

Lastly, in terms of social relationship health, amenities (β = 0.288 p < .001) was the significant predictor for the physical factor model. The social environment factors model demonstrated significant results with a sense of community (β = 0.177, p < .01) and neighborhood satisfaction (β = 0.149 p < .01) predicting residents’ social relationships. The combined model of physical and social environments highlighted amenities (β = 0.210 p < .001) as a significant predictor, accounting for 11% of the variation in social relationship health ().

Table 7. Social and physical factors predicting social relationship health of Imamzade Yahya neighborhood residents.

Discussion

This study assesses perceptions about the local social and physical environment as correlates of health-related quality of life among residents of the Imamzade Yahya neighborhood in Tehran, Iran. There were three key findings. Firstly, perceptions about three dimensions of the physical environment, namely, accessibility, amenity, and legibility, were associated with three forms of health-related quality-of-life reports. Secondly, the research indicated a significant correlation between social aspects such as participation, neighborhood satisfaction, a sense of community, and the health-related quality of life of the residents. Thirdly, residents demonstrated noticeably better environmental health compared to social relationships and psychological health.

Confirming our hypothesis and supporting the findings of many other research (Gao et al. Citation2017, Özkan and Yilmaz Citation2019), all subcomponents of the physical environment were discovered to have a positive effect on environmental and psychological health and higher QOL. Except for legibility, other aspects substantially influence the social relationship health of community dwellings. It was shown that neighborhood amenities significantly impacted environmental health, social relationships, and psychological health. Biagi et al. (Citation2018) found that a variety of amenities in the residential neighborhood were substantially correlated with convenience and highly linked with the residential quality of life. Since individuals prefer to mainly satisfy their needs within their surrounding environment (Lee et al. Citation2004), convenient physical settings can fulfill these demands and improve their quality of life.

The results indicate that residents with more accessibility experience a higher quality of life. Our results align with prior studies that connected accessibility to life satisfaction (Deitrick and Ellis Citation2004, Cao Citation2016). Being able to walk to purchase some daily necessities and reduced isolation are a few of the numerous positive effects that an accessible area has on social and mental health (Lotfi and Koohsari Citation2009). Accessible urban public spaces such as parks, recreational facilities, and social and cultural services, directly and indirectly, affect people’s quality of life and well-being (Witten et al. Citation2003). A high-quality pedestrian infrastructure promotes walking as a viable means of transportation and stimulates physical exercise that improves several health categories. Sidewalks are the primary pathways for walking, which is considered vital for promoting a healthy community (Sung et al. Citation2015). It has been established that sidewalk width, a buffer between the sidewalk and traffic, and the presence of amenities are strong predictors of overall safety and satisfaction in the physical environment (Landis et al. Citation2001, Marshall and Garrick Citation2010).

This study found that legibility is one of the most important elements of the neighborhood’s physical environment, which enhances people’s health. The monotony of dull, repetitive buildings and spaces is depressing and elicits sentiments of despair (CABE Citation2010). The human brain requires a specific hierarchy of open areas to generate mental maps that help with direction and navigation (Bengtsson and Grahn Citation2014, Moulay et al. Citation2017). The arrangement of architectural features into a cohesive pattern that makes a legible structure instills a sense of emotional stability (Finlay et al. Citation2015), makes the outside environment more attractive, and stimulates outdoor activities (Moulay et al. Citation2017).

Although modern cities offer numerous opportunities for residents to engage with others and build community, neighborhoods remain one of the most prevalent environments in which citizens establish relationships with people and places that contribute to a high quality of life (Sirgy and Cornwell Citation2002). Based on the results, both factual and subjective components of the social environment, such as the satisfaction of social needs, a sense of community, and participation, are crucial for health-related quality of life (Thoits Citation2011, Potočnik and Sonnentag Citation2013, Michalski et al. Citation2020). In this study, neighborhood satisfaction as an element of the social environment proved to have the most significant effect on environmental and psychological health. High neighborhood satisfaction correlates with a greater quality of life, mental health, and well-being (Sirgy and Cornwell Citation2002). Low community satisfaction is associated with people’s desire to move, undermining local cohesion and stability (Oh Citation2003).

This study showed a sense of community as the best predictor of healthy social relationships, followed by neighborhood satisfaction and participation. Strong, integrated communities offer residents friendships, social ties, community engagement, and access to community services, all of which lead to resident satisfaction and quality of life (Dassopoulos et al. Citation2012). The quantity and types of relationships between neighbors influence their sense of community. A sense of community and attachment to place is highly associated with well-being among diverse groups. Early studies imply that regardless of age (Zhang and Zhang Citation2017), nationality (Cicognani et al. Citation2008), or income (Jorgensen et al. Citation2010), a high level of social contact results in a shared emotional relationship and sense of community, which promotes a safer, more inclusive, and greater quality of social life (Keyes Citation1998). Additionally, lacking a sense of community leads to poor mental health and depression (Deckx et al. Citation2018). In agreement with our findings, a Columbian study (Leung et al. Citation2013) found that increased trust among neighbors enabled them to minimize negative emotions, stress, and anxiety. A higher degree of trust increases a person’s sense of safety and self-esteem, leading to improved mental health and the start of collective and coordinated efforts that might directly boost health by avoiding or postponing the illness and physical incapacity (Lucumí et al. Citation2015).

The results are consistent with existing research on the relationship between community participation and life satisfaction, greater quality of life, and well-being among community-dwelling individuals (Bertelli-Costa and Neri Citation2021, Peng et al. Citation2021). A study discovered favorable correlations between neighborly assistance, social activity or group engagement, and self-reported health (Lee et al. Citation2015). Regular participation in residential community-based activities enhances residents’ sense of a pleasant, meaningful, and joyful experience (Bonaiuto et al. Citation2016). Participating in community activities, engaging with neighbors, investing, voting, and volunteering are examples of a resident’s community involvement (Li and Loo Citation2017, Johnston and Lane Citation2018). Increased engagement within a community reduces individual fears, anxieties, and constraints, and it improves social mobility toward creating opportunities and social empowerment (Hoe et al. Citation2018). Moreover, participating in community activities helps residents get a deeper and more nuanced understanding of community organizational behavior and forge closer bonds with one another (Johnston and Lane Citation2018). Community-level participation may contribute to the enhancement of public welfare, the development of public trust, the elimination of health inequities, and the improvement of living standards and quality of life (Hayes et al. Citation2019).

This research extends beyond theoretical boundaries to inform policy and urban development strategies, with empirical evidence from the Imamzade Yahya neighborhood shaping nuanced approaches to enhancing urban living conditions in comparable settings. Enhancing the physical and social environments of urban neighborhoods emerges as a crucial strategy for improving residents’ quality of life (Khaef and Zebardast Citation2016, Zhang and Li Citation2019, Zhang et al. Citation2019). Specifically, urban design initiatives should focus on increasing accessibility to essential services, incorporating green spaces and recreational areas, and ensuring neighborhoods are pedestrian-friendly with well-maintained infrastructures (Stafford et al. Citation2007, Sugiyama et al. Citation2009, Gobbens and van Assen Citation2018, Lawrence et al. Citation2019). For example, Barcelona has pioneered the creation of ‘superblocks’, where traffic is restricted to the perimeter, allowing interior streets to become pedestrian zones filled with green spaces, playgrounds, and social areas. This initiative has improved air quality, reduced noise pollution, and enhanced the social and recreational life of residents, making neighborhoods safer and more vibrant (World Economic Forum Citation2019). Similarly, Melbourne’s ‘Urban Forest Strategy’ has focused on creating pedestrian-friendly zones and increasing green spaces by planting thousands of trees and developing parks and green corridors, which improve air quality, reduce urban heat, and promote physical activity and social interaction (Lehmann Citation2021). In the Netherlands, Utrecht has implemented innovative solutions to increase accessibility to green spaces, such as transforming car parking spaces into parks and communal areas. The city’s efforts to enhance public transportation and create extensive bicycle infrastructure have also made it one of the most bike-friendly cities in the world. These changes have improved accessibility and encouraged sustainable modes of transportation (Gemeente Utrecht Citation2021).

For social well-being, fostering community engagement through participatory decision-making processes, enhancing neighborhood satisfaction, and cultivating a strong sense of community are paramount. In Detroit, community engagement was central to neighborhood revitalization, with residents participating in decision-making workshops and providing input on housing, transportation, and public spaces. This approach improved neighborhood satisfaction and ensured that development reflected the community’s needs, fostering a strong sense of ownership and community cohesion (Burrowes Citation2019). Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) in various California cities involved residents working alongside researchers to identify environmental health issues and advocate for policy changes. This collaboration led to significant improvements in air quality and increased community awareness about health risks, empowering residents and fostering a stronger sense of community (Minkler et al. Citation2012). Such initiatives can lead to more cohesive, vibrant communities, ultimately elevating the overall health-related quality of life (Kawachi and Berkman Citation2000, Long and Perkins Citation2007, Cao Citation2016). Implementing these recommendations could serve as a blueprint for creating healthier, more sustainable urban living spaces, particularly in societies similar to Iran or those with comparable urban structures.

This study has limitations. First, the cross-sectional design prevents any assumptions of causality. Second, convenience sampling prevents generalizing the survey results to the larger population. Third, objective data about the local physical environment were not collected, meaning perceptions may not always align with reality. Additionally, the comparatively low alpha for neighborhood satisfaction indicates that this measure should be interpreted with caution. Despite these limitations, this study uncovers key insights into the correlation between perceived local physical and social environments and the health-related quality of life in the culturally and historically rich neighborhood of Tehran, a setting unique to the QOL literature, which is largely focused on Western contexts. In addition, this study stands out as the first to thoroughly examine the multifaceted interplay between various physical and social neighborhood characteristics and their direct impact on each component of health-related quality of life across all adult age groups within an Iranian context.

Future research should consider a longitudinal design and use objective measurements of health and neighborhood factors to avoid some of these limitations. Imamzade Yahya neighborhood with a cultural, religious, and historical background, organic texture, and indigenous residents in Tehran, the second-largest metropolitan area in the Middle East, provides a unique setting that fills a gap in the QOL literature, which is primarily focused on Western samples, however, results may not be generalizable to communities in other countries. In addition, a larger sample from multiple neighborhoods would allow testing of a larger, more complex [e.g. multi-level] modeling, which would be more commensurate to the complexity of the relationships between the physical environment, individuals’ perceptions, and health-related quality of life.

Conclusion

This study identified several social and physical environmental characteristics of urban residential neighborhoods that are related to the well-being and quality of life among Iranian adults. Specifically, the results demonstrated that perceived neighborhood physical environment had a greater influence on QOL than did social context. Amenities, such as public benches and physical maintenance, were the strongest predictor of various QOL health domains. Among the social and housing demographics of residents, only homeownership was shown to be substantially associated with QOL. This study also holds implications for the creation of environmental interventions and proposed policies by providing policymakers and health administrators with evidence-based information on particular social and physical environment effects on residents’ quality of life.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23748834.2024.2365501.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Shadi Omidvar Tehrani

Shadi Omidvar Tehrani is a Ph.D. student in the Community Research and Action program in the Department of Human and Organizational Development at Vanderbilt University. She holds a master’s degree in Urban Designing from the Iran University of Science and Technology. Her research interests lie at the intersection of the built environment and public health and through her work, she aims to understand the complex processes that drive gentrification and the ways in which gentrification affects the social and economic fabric of communities.

Jessica M. Perkins

Jessica M. Perkins, PhD, MS, is an interdisciplinary social and behavioral scientist and an Assistant Professor at Vanderbilt Peabody College of Education and Human Development. Dr. Perkins research broadly assesses social norms and social networks as drivers of HIV prevention and treatment and co-occurring behaviors and attitudes. Specifically, she focuses on identifying misperceptions about health-promoting norms within local networks as opportunities to implement norms-based strategies to encourage individual and collective change.

Douglas D. Perkins

Douglas D. Perkins, MA, PhD, is a professor of Human and Organizational Development at Vanderbilt University and founding director of the PhD Program in Community Research and Action. His current research focuses on the global development of applied community research and professional fields, including community psychology, community sociology, community development, community social work, development anthropology, development economics, public health, community geography/planning, local public administration/policy studies, popular/community education, faith-based community action, and interdisciplinary community studies.

References

- Amoah, P.A. and Adjei, M., 2023. Social capital, access to healthcare, and health-related quality of life in urban Ghana. Journal of urban affairs, 45 (3), 570–589. doi:10.1080/07352166.2021.1969245.

- An, J., et al., 2020. Mental health of urban residents in the developed cities of the Yangtze river delta in China: measurement with the mental composite scale from the WHOQOL-BREF. Current Psychology, 39 (3), 810–820. doi:10.1007/s12144-019-0142-6.

- Arabi, M., Saberi Naseri, T., and Jahdi, R., 2020. Use all generation of crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED) for design urban historical fabric (Case study: the central area of Tehran metropolis, Eastern Oudlajan). Ain Shams engineering journal, 11 (2), 519–533. doi:10.1016/j.asej.2019.11.003.

- Arastoo, A., et al., 2012. Factors affecting quality of life in elderly diabetic residents of the Kahrizak Geriatric Nursing Home of Tehran. Iranian journal of endocrinology and metabolism (IJEM), 14 (1), 18–24.

- Araya, R., et al., 2006. Perceptions of social capital and the built environment and mental health. Social science & medicine, 62 (12), 3072–3083. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.037.

- Bandalos, D. and Finney, S., 2019. Factor analysis: exploratory and confirmatory 98–122. doi:10.4324/9781315755649-8.

- Bengtsson, A. and Grahn, P., 2014. Outdoor environments in healthcare settings: a quality evaluation tool for use in designing healthcare gardens. Urban forestry & urban greening, 13 (4), 878–891. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2014.09.007.

- Berkman, L.F. and Kawachi, I., 2000. Social epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bertelli-Costa, T. and Neri, A.L., 2021. Life satisfaction and participation among community-dwelling older adults: data from the FIBRA study. Journal of health psychology, 26 (11), 1860–1871. doi:10.1177/1359105319893020.

- Biagi, B., Ladu, M.G., and Meleddu, M., 2018. Urban quality of life and capabilities: an experimental study. Ecological economics, 150, 137–152. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.04.011.

- Bodur, S. and Dayanir Cingil, D., 2009. Using WHOQOL-BREF to evaluate quality of life among Turkish elders in different residential environments. JNHA-The journal of nutrition, health and aging, 13 (7), 652–656. doi:10.1007/s12603-009-0177-8.

- Bonaiuto, M., et al., 2016. Optimal experience and personal growth: flow and the consolidation of place identity. Frontiers in psychology, 7, 1654. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01654.

- Bond, L., et al., 2012. Exploring the relationships between housing, neighbourhoods and mental wellbeing for residents of deprived areas. BMC public health, 12 (1), 48. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-48.

- Bowling, A. and Stafford, M., 2007. How do objective and subjective assessments of neighbourhood influence social and physical functioning in older age? Findings from a British survey of ageing. Social science & medicine, 64 (12), 2533–2549. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.009.

- Bukov, A., Maas, I., and Lampert, T., 2002. Social participation in very old age: cross-sectional and longitudinal findings from BASE. The journals of gerontology series B: psychological sciences and social sciences, 57 (6), 510–P517. doi:10.1093/geronb/57.6.P510.

- Burrowes, K., 2019. Detroit shows how placemaking can undo neighborhood segregation. Urban Institute. Available from: https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/detroit-shows-how-placemaking-can-undo-neighborhood-segregation. [Accessed 15 July 2019].

- CABE, 2010. Community green. Available from: https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-work/skills-learning/resources/community-green/.

- Cao, X.J., 2016. How does neighborhood design affect life satisfaction? Evidence from twin cities. Travel behaviour and society, 5, 68–76. doi:10.1016/j.tbs.2015.07.001.

- Carta, M.G., et al., 2012. Quality of life and urban/rural living: preliminary results of a community survey in Italy. Clinical practice and epidemiology in mental health: CP & EMH, 8 (1), 169. doi:10.2174/1745017901208010169.

- Cheraghi, Z., et al., 2016. Quality of life in elderly Iranian population using the QOL-brief questionnaire: a systematic review. Iranian journal of public health, 45 (8), 978. doi:10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_265_16.

- Cicognani, E., et al., 2008. Social participation, sense of community and social well being: a study on American, Italian and Iranian university students. Social indicators research, 89 (1), 97–112. doi:10.1007/s11205-007-9222-3.

- Cochran, W.G., 1991. Sampling techniques. 3rd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

- Cohen, S. and Wills, T.A., 1985. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological bulletin, 98 (2), 310–357. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310.

- Dassopoulos, A., et al., 2012. Neighborhood connections, physical disorder, and neighborhood satisfaction in Las Vegas. Urban affairs review, 48 (4), 571–600. doi:10.1177/1078087411434904.

- Deckx, L., et al., 2018. A systematic literature review on the association between loneliness and coping strategies. Psychology, health & medicine, 23 (8), 899–916. doi:10.1080/13548506.2018.1446096.

- Deitrick, S. and Ellis, C., 2004. New urbanism in the inner city: a case study of pittsburgh. Journal of the American planning association, 70 (4), 426–442. doi:10.1080/01944360408976392.

- Doumit, J. and Nasser, R., 2010. Quality of life and wellbeing of the elderly in Lebanese nursing homes. International journal of health care quality assurance, 23 (1), 72–93. doi:10.1108/09526861011010695.

- Ebrahiminia, D., 2019. (99+) applying urban agriculture principles in neighborhood scale case study: Imamzadeh Yahya neighborhood of Tehran. Manzar Journal and delaram, ebrahiminia–Academia.edu—. Available from: https://www.academia.edu/44361170/Applying_Urban_Agriculture_Principles_in_Neighborhood_Scale_Case_Study_Imamzadeh_Yahya_Neighborhood_of_Tehran?auto=download.

- Ellen, I.G., Mijanovich, T., and Dillman, K.-N., 2001. Neighborhood effects on health: exploring the links and assessing the evidence. Journal of urban affairs, 23 (3–4), 391–408. doi:10.1111/0735-2166.00096.

- Elvas, S. and Moniz, M.J.V., 2010. Sentimento de comunidade, qualidade e satisfação de vida. Análise Psicológica, 28 (3), 451–464. doi:10.14417/ap.312.

- Erin, M.H., et al., 2012. Perceptions of neighborhood problems and health‐related quality of life. Journal of community psychology, 40 (7), 814–827.

- Ferrans, C.E., et al., 2005. Conceptual model of health‐related quality of life. Journal of nursing scholarship, 37 (4), 336–342. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2005.00058.x.

- Finlay, J., et al., 2015. Therapeutic landscapes and wellbeing in later life: impacts of blue and green spaces for older adults. Health & place, 34, 97–106. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.05.001.

- Fox, N.J. and Powell, K., 2023. Place, health and dis/advantage: a sociomaterial analysis. Health: An interdisciplinary journal for the social study of health, illness and medicine, 27 (2), 226–243. doi:10.1177/13634593211014925.

- Frank, L.D., et al., 2005. Linking objectively measured physical activity with objectively measured urban form: findings from SMARTRAQ. American journal of preventive medicine, 28 (2, Supplement 2), 117–125. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2004.11.001.

- Gao, Y., et al., 2017. Understanding the relationship between travel satisfaction and subjective well-being considering the role of personality traits: a structural equation model. Transportation research part F: Traffic psychology and behaviour, 49, 110–123. doi:10.1016/j.trf.2017.06.005.

- Gemeente Utrecht, 2021. Cycling | gemeente Utrecht. Available from: https://www.utrecht.nl/city-of-utrecht/mobility/cycling/.

- Ghasemi, S.R., et al., 2019. Health-related quality of life in informal settlements in Kermanshah, Islamic republic of Iran: role of poverty and perception of family socioeconomic status. Eastern Mediterranean health journal, 25 (11), 775–783. doi:10.26719/emhj.19.013.

- Gobbens, R.J. and van Assen, M.A., 2018. Associations of environmental factors with quality of life in older adults. The gerontologist, 58 (1), 101–110. doi:10.1093/geront/gnx051.

- Gong, Y., et al., 2016. A systematic review of the relationship between objective measurements of the urban environment and psychological distress. Environment international, 96, 48–57. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2016.08.019.

- Grasser, G., et al., 2013. Objectively measured walkability and active transport and weight-related outcomes in adults: a systematic review. International journal of public health, 58 (4), 615–625. doi:10.1007/s00038-012-0435-0.

- Gu, N., 2020. The effects of neighborhood social ties and networks on mental health and well-being: a qualitative case study of women residents in a middle-class Korean urban neighborhood. Social science & medicine, 265, 113336. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113336.

- Habibi, S. and Zebardast, E., 2018. Exploring the physical-environmental domains of quality of life; the experience of midsize cities in Iran. Urban research & practice, 11 (4), 426–440. doi:10.1080/17535069.2017.1381761.

- Hasani, F., et al., 2012. Factors affecting quality of life of the elderly in the residential homes of Tehran. Journal of Birjand University of Medical Sciences, 18 (4), 320–328.

- Hayes, J.E., et al., 2019. Investigation of non-community stakeholders regarding community engagement and environmental malodour. Science of the total environment, 665, 546–556. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.137.

- Heo, J., et al., 2020. Community determinants of physical growth and cognitive development among Indian children in early childhood: a multivariate multilevel analysis. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17 (1), 182. doi:10.3390/ijerph17010182.

- Hoe, K.C., et al., 2018. Community participation for rural poverty alleviation: a case of the Iban community in Malaysia. International social work, 61 (4), 518–536. doi:10.1177/0020872816673890.

- James, B.D., et al., 2011. Relation of late-life social activity with incident disability among community-dwelling older adults. Journals of gerontology series A: Biomedical sciences and medical sciences, 66 (4), 467–473. doi:10.1093/gerona/glq231.

- Johnston, K.A. and Lane, A.B., 2018. Building relational capital: the contribution of episodic and relational community engagement. Public relations review, 44 (5), 633–644. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2018.10.006.

- Jorgensen, B.S., Jamieson, R.D., and Martin, J.F., 2010. Income, sense of community and subjective well-being: combining economic and psychological variables. Journal of economic psychology, 31 (4), 612–623. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2010.04.002.

- Kalfoss, M.H., et al., 2021. Validation of the WHOQOL-Bref: psychometric properties and normative data for the Norwegian general population. Health and quality of life outcomes, 19 (1), 13. doi:10.1186/s12955-020-01656-x.

- Kawachi, I. and Berkman, L., 2000. Social cohesion, social capital, and health. Social epidemiology, 174 (7), 290–319.

- Keyes, C.L.M., 1998. Social well-being. Social psychology quarterly, 61 (2), 121–140. doi:10.2307/2787065.

- Khaef, S. and Zebardast, E., 2016. Assessing quality of life dimensions in deteriorated inner areas: a case from Javadieh neighborhood in Tehran metropolis. Social indicators research, 127 (2), 761–775. doi:10.1007/s11205-015-0986-6.

- Khosravi, H. and Tehrani, S.O., 2019. Local environment, human functions and the elderly depression and anxiety. Ageing international, 44 (2), 170–188. doi:10.1007/s12126-017-9312-8.

- Killewo, J., Heggenhougen, K., and Quah, S.R., 2010. Epidemiology and demography in public health. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Landis, B.W., et al., 1 2001. Modeling the roadside walking environment: pedestrian level of service. Transportation research record, 1773 (1), 82–88. doi:10.3141/1773-10.

- Lawrence, R.J., Forbat, J., and Zufferey, J., 2019. Rethinking conceptual frameworks and models of health and natural environments. Health: An interdisciplinary journal for the social study of health, illness and medicine, 23 (2), 158–179. doi:10.1177/1363459318785717.

- Lee, H.C., Park, H.-B., and Jung, W.L., 2004. An analysis on the factors to affect the settlement consciousness of in habitants. The Korean association for policy studies, 13 (3), 147–167.

- Lee, J.-A., Park, J.H., and Kim, M., 2015. Social and physical environments and self-rated health in urban and rural communities in Korea. International journal of environmental research and public health, 12 (11), 14329–14341. doi:10.3390/ijerph121114329.

- Lehmann, S., 2021. Growing biodiverse urban futures: renaturalization and rewilding as strategies to strengthen urban resilience. Sustainability, 13 (5), Article 5. doi:10.3390/su13052932.

- Leung, A., et al., 2013. Searching for happiness: The importance of social capital. In: A. D. Fave, ed. The exploration of happiness. Heidelberg: Springer, 247–267.

- Levasseur, M., et al., 2010. Inventory and analysis of definitions of social participation found in the aging literature: proposed taxonomy of social activities. Social science & medicine, 71 (12), 2141–2149. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.041.

- Li, L. and Loo, B.P., 2017. Mobility impairment, social engagement, and life satisfaction among the older population in China: a structural equation modeling analysis. Quality of life research, 26 (5), 1273–1282. doi:10.1007/s11136-016-1444-x.

- Long, D.A. and Perkins, D.D., 2007. Community social and place predictors of sense of community: a multilevel and longitudinal analysis. Journal of community psychology, 35 (5), 563–581. doi:10.1002/jcop.20165.

- Lotfi, S. and Koohsari, M.J., 2009. Measuring objective accessibility to neighborhood facilities in the city (A case study: zone 6 in Tehran, Iran). Cities, 26 (3), 133–140. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2009.02.006.

- Lucumí, D.I., et al., 2015. Social capital, socioeconomic status, and health-related quality of life among older adults in Bogotá (Colombia). Journal of aging and health, 27 (4), 730–750. doi:10.1177/0898264314556616.

- Marshall, W.E. and Garrick, N.W., 2010. Street network types and road safety: a study of 24 California cities. Urban design international, 15 (3), 133–147. doi:10.1057/udi.2009.31.

- McMillan, D.W. and Chavis, D.M., 1986. Sense of community: a definition and theory. Journal of community psychology, 14 (1), 6–23. doi:10.1002/1520-6629(198601)14:1<6:AID-JCOP2290140103>3.0.CO;2-I.

- Michalski, C.A., et al., 2020. Relationship between sense of community belonging and self-rated health across life stages. SSM-population health, 12, 100676. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100676.

- Minkler, M., et al., 2012. Community-based participatory research: a strategy for building healthy communities and promoting health through policy change. PolicyLink. Available from: https://www.policylink.org/resources-tools/building-healthy-communities-and-promoting-health-through-policy-change.

- Moulay, A., Ujang, N., and Said, I., 2017. Legibility of neighborhood parks as a predicator for enhanced social interaction towards social sustainability. Cities, 61, 58–64. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2016.11.007.

- Mouratidis, K., 2021. Urban planning and quality of life: a review of pathways linking the built environment to subjective well-being. Cities, 115, 103229. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2021.103229.

- Nedjat, S., et al., 2011. Quality of life among an Iranian general population sample using the world health organization’s quality of life instrument (WHOQOL-BREF). International journal of public health, 56 (1), 55–61. doi:10.1007/s00038-010-0174-z.

- Oh, J.-H., 2003. Social bonds and the migration intentions of elderly urban residents: the mediating effect of residential satisfaction. Population research and policy review, 22 (2), 127–146. doi:10.1023/A:1025067623305.

- Ohaeri, J.U. and Awadalla, A.W., 2009. The reliability and validity of the short version of the WHO quality of life instrument in an Arab general population. Annals of Saudi medicine, 29 (2), 98–104. doi:10.4103/0256-4947.51790.

- Olsen, J.R., Dundas, R., and Ellaway, A., 2017. Are changes in neighbourhood perceptions associated with changes in self-rated mental health in adults? A 13-year repeat cross-sectional study, UK. International journal of environmental research and public health, 14 (12), 1473. doi:10.3390/ijerph14121473.

- Özkan, D.G. and Yilmaz, S., 2019. The effects of physical and social attributes of place on place attachment: a case study on Trabzon urban squares. Archnet-IJAR: international journal of architectural research, 13 (1), 133–150. doi:10.1108/ARCH-11-2018-0010.

- Peng, C., et al., 2021. Expanding social, psychological, and physical indicators of urbanites’ life satisfaction toward residential community: a structural equation modeling analysis. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18 (1), 4. doi:10.3390/ijerph18010004.

- Perkins, D.D., et al., 2021. Well-being as human development, equality, happiness and the role of freedom, activism, decentralization, volunteerism and voter participation: a global country-level study. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 4131.

- Potočnik, K. and Sonnentag, S., 2013. A longitudinal study of well‐being in older workers and retirees: the role of engaging in different types of activities. Journal of occupational and organizational psychology, 86 (4), 497–521. doi:10.1111/joop.12003.

- Rautio, N., et al., 2018. Living environment and its relationship to depressive mood: a systematic review. International journal of social psychiatry, 64 (1), 92–103. doi:10.1177/0020764017744582.

- Rezvani, M.R., Mansourian, H., and Sattari, M.H., 2013. Evaluating quality of life in urban areas (case study: Noorabad city, Iran). Social Indicators research, 112 (1), 203–220. doi:10.1007/s11205-012-0048-2.

- Richard, L., et al., 2009. Staying connected: neighbourhood correlates of social participation among older adults living in an urban environment in Montreal, Quebec. Health promotion international, 24 (1), 46–57. doi:10.1093/heapro/dan039.

- Sampson, R.J., 2003. The neighborhood context of well-being. Perspectives in biology and medicine, 46 (3), S53–S64. doi:10.1353/pbm.2003.0059.

- Scavarda, A., Costa, G., and Beccaria, F., 2023. Using photovoice to understand physical and social living environment influence on adherence to diabetes. Health: An interdisciplinary journal for the social study of health, illness and medicine, 27 (2), 279–300. doi:10.1177/13634593211020066.

- Scheffler, R.M., Brown, T.T., and Rice, J.K., 2007. The role of social capital in reducing non-specific psychological distress: the importance of controlling for omitted variable bias. Social science & medicine, 65 (4), 842–854. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.042.

- Seresinhe, C.I., et al., 2019. Happiness is greater in more scenic locations. Scientific reports, 9 (1), 4498. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-40854-6.

- Shields, M. and Shooshtari, S., 2001. Determinants of self-perceived health. Health reports, 13 (1), 35–52.

- Sirgy, M.J. and Cornwell, T., 2002. How neighborhood features affect quality of life. Social indicators research, 59 (1), 79–114. doi:10.1023/A:1016021108513.

- Slater, S.J., Christiana, R.W., and Gustat, J., 2020. Peer reviewed: recommendations for keeping parks and green space accessible for mental and physical health during COVID-19 and other pandemics. Preventing Chronic Disease, 17. doi:10.5888/pcd17.200204.

- Soleimani, M., et al., 2014. The assessment of quality of life in transitional neighborhoods. Social indicators research, 119 (3), 1589–1602. doi:10.1007/s11205-013-0563-9.

- Stafford, M., Chandola, T., and Marmot, M., 2007. Association between fear of crime and mental health and physical functioning. American journal of public health, 97 (11), 2076–2081. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.097154.

- Sugiyama, T., et al., 2009. Physical activity for recreation or exercise on neighbourhood streets: associations with perceived environmental attributes. Health & place, 15 (4), 1058–1063. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.05.001.

- Sugiyama, T., Thompson, C.W., and Alves, S., 2009. Associations between neighborhood open space attributes and quality of life for older people in Britain. Environment and behavior, 41 (1), 3–21. doi:10.1177/0013916507311688.

- Sung, H., et al., 2015. Effects of street-level physical environment and zoning on walking activity in Seoul, Korea. Land use policy, 49, 152–160. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.07.022.

- Szreter, S. and Woolcock, M., 2004. Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. International journal of epidemiology, 33 (4), 650–667. doi:10.1093/ije/dyh013.

- Thoits, P.A., 2011. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. Journal of health and social behavior, 52 (2), 145–161. doi:10.1177/0022146510395592.

- Tiraphat, S., et al., 2017. The role of age-friendly environments on quality of life among Thai older adults. International journal of environmental research and public health, 14 (3), 282. doi:10.3390/ijerph14030282.

- van den Berg, M., et al., 2016. Visiting green space is associated with mental health and vitality: a cross-sectional study in four European cities. Health & place, 38, 8–15. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.01.003.

- Wang, J., et al., 2018. Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: a systematic review. BMC psychiatry, 18 (1), 156. doi:10.1186/s12888-018-1736-5.

- White, M.P., et al., 2013. Would you be happier living in a greener urban area? A fixed-effects analysis of panel data. Psychological Science, 24 (6), 920–928. doi:10.1177/0956797612464659.

- WHO, 2012. The world health organization quality of life (WHOQOL). Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-HIS-HSI-Rev.2012.03.

- Witten, K., Exeter, D., and Field, A., 2003. The quality of urban environments: mapping variation in access to community resources. Urban studies, 40 (1), 161–177. doi:10.1080/00420980220080221.

- World Economic Forum, 2019. Barcelona’s “superblocks” could save lives and cut pollution, says report. World economic forum. Available from: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/09/barcelona-superblocks-air-pollution-cities/ [Accessed 13 Sep 2019].

- Yazdanpanah Shahabadi, M.R. and Sajadzadeh, H., 2020. Social aspect of quality of urban life: how does social capital affect desire of residents to continue living in historical neighborhoods? Evidence from Tehran, Iran. Journal of place management and development, 13 (4), 493–511. doi:10.1108/JPMD-10-2018-0072.

- Zhang, C.J., et al., 2019. Objectively-measured neighbourhood attributes as correlates and moderators of quality of life in older adults with different living arrangements: the ALECS cross-sectional study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16 (5), 876. doi:10.3390/ijerph16050876.

- Zhang, F. and Li, D., 2019. Multiple linear regression-structural equation modeling based development of the integrated model of perceived neighborhood environment and quality of life of community-dwelling older adults: a cross-sectional study in Nanjing, China. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16 (24), 4933. doi:10.3390/ijerph16244933.

- Zhang, H. and Lin, S.-H., 2011. Affective appraisal of residents and visual elements in the neighborhood: a case study in an established suburban community. Landscape and urban planning, 101 (1), 11–21. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2010.12.010.

- Zhang, T., Sun, Y., and Yuan, X., 2023. Is mixed-housing development healthier for residents? The implications on the perception of neighborhood environment, sense of place, and mental health in urban Guangzhou. Journal of urban affairs, 0 (0), 1–20. doi:10.1080/07352166.2023.2180379.

- Zhang, Z. and Zhang, J., 2017. Perceived residential environment of neighborhood and subjective well-being among the elderly in China: a mediating role of sense of community. Journal of environmental psychology, 51, 82–94. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.03.004.