ABSTRACT

Rationale/Purpose: Traditional European sports clubs are facing increasing pressures to professionalise their services, while also encountering difficulties in the recruitment and retention of the coaching workforce. We used the concept of meaningful work to explore why coaching is worthwhile to coaches and how they have responded to the changes in the structural and narrative context of their work.

Methodology: Drawing on narrative inquiry, we explored the various meanings and justifications that athletics (track and field) coaches assign to coaching in Finland and England. Twenty-three coaches (8 women, 15 men) aged 22–86 participated in narrative interviews that were analysed using thematic narrative analysis.

Findings: The younger coaches mainly constructed coaching as a hobby and more often placed value on personal benefits, whereas many older coaches described coaching as a vocation/calling and emphasised causes that transcend the self (e.g. tradition, duty and leaving a legacy).

Practical implications: Understanding the diverse ways in which coaching is meaningful is vital for supporting the recruitment and retention of the coaching workforce in sport clubs.

Research contribution: The study extends understandings of meaningful work in coaching and how coaching is shaped by the broader structural and ideological contexts of the work.

For the last two decades, European sport organisations have been increasingly expected by governments and coaching agencies to organise their “services” in a more business-like and professional manner (Grix, Citation2009; International Council for Coaching Excellence [ICCE] et al., Citation2013; Taylor & Garratt, Citation2010). Some scholars have warned that, as the voluntary sport sector is shifting from a notion of mutual aid to service delivery, it could be also losing the core resources that have helped sustain it in the past: the traditional coaching ideology, shared values of volunteerism, and member solidarity (Grix, Citation2009; Nichols et al., Citation2005). Furthermore, despite this move towards professionalisation, volunteer-based club systems, where the majority of coaches operate on an amateur basis while pursuing a job or career elsewhere, remains prevalent in many countries (Breuer et al., Citation2015).

While volunteering in sports and other life domains have been traditionally viewed as an activity animated by service ethic and desire to contribute to the community, scholars have argued that younger volunteers are increasingly viewing – and are encouraged to view – volunteering as an avenue for professional development, curriculum vitae building and self-realisation (Dean, Citation2014; Hayton, Citation2016; Hustinx & Lammertyn, Citation2003). In the UK, Hayton (Citation2016) contextualised the emerging importance of “instrumental” volunteering to “citizenship education” (introduced in the early 2000s) and the rising tuition fees of universities that have reinforced employability discourses. His research showed that instrumental motives were especially prevalent in the initial stage of the student volunteering experience, with gaining work experience to enhance employability often cited as the main reason for engagement. Studies with older volunteers have reported that other-oriented motivations (e.g. a sense of contributing, altruism) are often important, but that self-oriented motivations also seem to play a role in explaining commitment (Misener et al., Citation2010; Principi et al., Citation2016). This highlights that the traditional ideal of volunteering as purely altruistic work is probably unrealistic for any account of volunteering (Hustinx & Lammertyn, Citation2003).

While many studies have explored the different types of volunteer coach motivation, no studies have sought to address coach retention from a meaningful work perspective. Organisational researchers outside of sport have centralised the concept of meaningful work as vital for understanding organisational commitment and associated it with “satisfied, engaged and committed employees, individual and organisational fulfilment, productivity, retention and loyalty” (Geldenhuys et al., Citation2014, p. 1). As we will argue, meaningful work can extend our understandings of volunteer coaching by leading us to ask different questions and “diagnose” different kinds of problems than studies that are focused on motivation (e.g. the lack of intrinsic motivation; Hayton, Citation2016). Drawing on narrative interviews with athletics (track and field) coaches of different ages, we explore what kind of meanings they assign to coaching, how they justify why their work is worth the effort, and what culturally available narrative resources they draw upon in doing so. We also aim to make inferences about the possible impacts of the shifting social arrangement of sport clubs on the coaches’ ability to find meaning in their work. The following research questions guided our inquiry:

What work meanings do coaches assign to coaching?

What helps to explain differences in these meanings?

How do coaches justify the worth and value of their work?

The concept of meaningful work

Meaningful work has become a key concept in organisational management and vocational psychology and has been associated with several positive outcomes including higher levels of employee wellbeing, organisational commitment, job performance, job satisfaction, and personal fulfilment (Bailey et al., Citation2019; Geldenhuys et al., Citation2014). Scholars have emphasised that the construct of meaningful work should also include non-paid work and, indeed, volunteering has been discussed as one potential – yet not automatic – avenue for meaningful work (Taylor & Roth, Citation2019). Although there is diversity in measurement, theory and definitions, meaningful work is often conceived as work involving a broader purpose beyond the self and offering possibilities for self-expression and self-development (Martela & Pessi, Citation2018).

Lepisto and Pratt (Citation2017) suggested that the literature is characterised by two distinct perspectives that identify different core “problems” and destinations of meaningful work. As they summarised, “a realization perspective focuses on overcoming alienation and asks, ‘does my work reflect and fulfill who I am?’ A justification perspective, by contrast, focuses on overcoming anomie-like conditions and asks, ‘Why is my work worthy?’” (p. 111). The self-realisation perspective has significant overlaps with motivational theories (e.g. self-determination theory), emphasises constructs such as autonomy, self-efficacy, intrinsic motivation and job crafting, and often considers the threat to meaningful work to lie in dull, repetitive and controlled tasks. The justification perspective, on the other hand, focuses on an individual’s ability to account for the moral worth of what they are doing. From this vantage, the potential “problem” individuals are facing is not about lack of intrinsic motivation or flow, but “is perhaps more existential in nature – it suggests fundamental uncertainty or ambiguity regarding the basic worth or value of the work individuals are engaged in” (Lepisto & Pratt, Citation2017, p. 108). Relatedly, Bellah et al. (Citation2008) noted that “finding yourself” discourses of work lack deeper, existential justification; as they summarised:

Ideas of the self’s inner expansion reveal nothing of the shape moral character should take, the limits it should respect, and the community it should serve (…) ideas of potentiality (for what?) tell us nothing of which purposes are worth pursuing (p. 79).

Lepisto and Pratt (Citation2017) further emphasised that the ability to justify work’s worth is tied to a specific socio-historic context and depends on the ability to connect one’s work to broader narratives about “good life” and citizenship – and is therefore closely connected to narrativity and storytelling.

In Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life, Bellah et al. (Citation2008) suggested that people generally have three different orientations to work: job, career, or calling. While job denotes a necessity and career a quest of progress and personal success, a calling is tied to a broader justification of work’s worth that Lepisto and Pratt (Citation2017) discussed. For Bellah et al. (Citation2008), a calling constitutes

A practical ideal of activity and character that makes a person’s work morally inseparable from his or her life. It subsumes the self into a community of disciplined practice and sound judgment whose activity has meaning and value in itself, not just in the output or profit that results from it. (p. 66)

The “neoclassical” concept of calling taps into existential questions about the justification of work and the moral worth of one’s working life which have traditionally been connected to religious beliefs and value systems or notions of destiny or fate (Lepisto & Pratt, Citation2017). On the other hand, the “modernist” notion of calling focuses on self-realisation, with calling considered more like a consuming passion or an avenue for self-actualisation (e.g. Dobrow & Tosti-Kharas, Citation2011). This shift in the meaning of calling runs parallel to the changing meanings of volunteer work, with the focus on self-actualisation and self-development now being more prominent than in the traditional discourses that emphasise moral causes that transcend the self (Hustinx & Lammertyn, Citation2003). In our study, we were cognisant that meanings of vocations and callings are shifting, and that scholars have called for more research into how callings are understood and expressed in various occupations (Dik & Shimizu, Citation2019).

Methodology

Since personal storytelling infuses biographical events and unique experiences into culturally available narrative templates (Smith, Citation2016), narrative inquiry was selected as an ideally suited approach to study how sports coaches make sense of their lives and careers in particular social locations. Although many scholars have advocated the study of narratives from a relativist perspective, a realist perspective has also been implicated in many biographical studies (Steensen, Citation2006). A realist perspective assumes ontological realism (there is a real world independent of our attempts to know it) and epistemological constructivism (our knowledge is fallible and theory-laden), while also emphasising that social science research should aim to explain and not only describe phenomena (e.g. types of narratives and discourses evident in the data). In defending the (critical) realist starting point of biographical research, Steensen (Citation2006) argued that it is necessary to acknowledge the reality of structures that lie behind the stories and analyse the interactions between structure and agency to be able to explain meaning. As Day and Carpenter (Citation2015) argued, “coaches are always influenced by the social and sporting structures within which they operate, so changes inevitably occur in the organization and meanings of the coaching role as relationships change and power balance shifts” (p. 2). In constructing their personal stories, coaches rely on cultural narrative resources that offer specific plots for stories (such as a plot of coaching as a hobby or vocation) and cultural life scripts that are prescriptive plots for how an “ideal” life should unfold and what events, experiences and life foci are normatively expected in different life stages (Berntsen & Rubin, Citation2004). For us, narrative interviewing provided evidence about coaches’ experiences, intentions and meanings, as well as material for making inferences about the types of meaningful work relevant for coaches in the changing structural and ideological landscape of sport coaching (see Hammersley, Citation2003).

Context of the study

The study draws on narrative interviews with 23 athletics (track and field) coaches (15 men, 8 women) aged between 22 and 86 years (median 45 years), who were coaching in two clubs, one in Finland and one in England. The study is part of two broader projects, one on club culture, coaching philosophy and lifelong participation, and other on youth athlete developmental trajectories (Ryba et al., Citation2016). The clubs were selected because they both had a long and successful history and were among the bigger clubs in their region. In both countries, athletics has traditionally been organised by amateurs in volunteer-based sport clubs and success in athletics has been a historically important national identity project (Llewellyn, Citation2012). There are, however, well-documented and long-standing tensions between amateur traditions and pragmatic attempts to professionalise coaching; for example, in Britain where resistance to professional coaches has been ongoing since the first few decades of the twentieth century (Day, Citation2017; Day & Carpenter, Citation2015). In recent years, there have been further and intensifying calls for professionalisation of sport clubs in both the UK and Finland (Grix, Citation2009; Koski & Mäenpää, Citation2018; Taylor & Garratt, Citation2010) which reflect the broader trend of development in European countries (Breuer et al., Citation2015) and throughout the world (Shilbury & Ferkins, Citation2020).

In the UK, Taylor and Garratt (Citation2010) observed that the new “professional” coach now needs to be certified through a UK-wide system and is expected to work toward official goals of widening participation and social inclusion. Indeed, organisations such as U.K. Sport have made substantial financial investments to develop coaches in the UK (Potts et al., Citation2019) where there are an estimated 3 million active coaches (Thompson & Mcilroy, Citation2017). North (Citation2009) highlighted that part-time and voluntary coaches made up approximately 97% of the coaching workforce (25 and 72%, respectively) in 2009. Yet, increased professionalisation is indicated by more recent assessments of employment and remuneration status. By 2017 it was reported that 57% of coaches worked in a voluntary capacity, providing around 5.2 million coaching hours per week, that 24% coached in a paid capacity, providing around 5.3 million coaching hours, and 18% coached in both a paid and volunteer capacity, providing around 4.5 million hours per week (Thompson & Mcilroy, Citation2017).

The development of sport clubs in Finland has followed a similar pattern, and the government has initiated several support mechanisms to facilitate hiring professional employees (Koski & Mäenpää, Citation2018). Puska et al. (Citation2017) reported that in 2016 there were 1682 professional coaches in Finland (49 in athletics), compared to only 441 coaches in 2002; at the same time, coach education and ethical codes of conduct have been increasingly formalised. However, non-professional coaches and other volunteers (e.g. officials) remain centrally important for running the club activities, and some reports indicate an increasing difficulty in attracting and retaining this workforce. A survey in 2016 indicated that 60% of representatives of sport clubs considered it more difficult to recruit volunteers than before, and approximately half of them evaluated that the number of volunteers has decreased (Koski & Mäenpää, Citation2018). The Finnish coaches who participated in the current research received moderate monetary compensation for their coaching sessions, and the club also had full-time employees responsible for organising the club administration. As such, the Finnish club can be characterised as having “a blended identity”, as opposed to the English club that seemed to embrace “voluntary service identity” (ICCE et al., Citation2013).

Participants and procedure

After ethical approvals for the research were obtained from relevant University ethical committees in Finland and England, gatekeepers in the clubs were contacted to assist with participant recruitment. Emails were circulated with potential participants to describe the purpose of the study and that participation was completely voluntary. Some coaches also helped to facilitate participant recruitment after they had been interviewed themselves. All coaches who responded to the invitation were interviewed. We sought to recruit and engage with a sample that was as diverse as possible in terms of age, level of experience and athlete group to explore variation in how coaches assign meaning to what they do. The final sample was indeed diverse, with coaches’ experience varying from few years to several decades (median 15 years) and athlete groups varying from children and adolescents (N = 7), adolescents and young adults (N = 11), young adults only (N = 1), young and middle-aged adults (N = 1), and Masters athletes (N = 3). All except for one participant were ethnic Finns or British; one participant was originally from an African country. To protect the anonymity of the participants, we have not provided individual demographic information.

The first and the fifth author carried out the interviews in club facilities and cafés depending on participants’ preferences and availability of empty offices. We employed a narrative approach and first invited the coaches to share their stories of becoming a coach. The interviewers mostly followed up with clarifying questions (e.g. “when did that happen?” or “how did you feel about that?”) and invitations to continue the story (e.g. “what happened after that?”). After the coaches had told their stories up to the present moment, we asked them to reflect on justifications of their work (what makes coaching worthwhile for you?), and then drawing inspiration from Bellah et al.’s (Citation2008) distinction between work orientations (job/career/calling), we asked them to think whether they felt that coaching was their hobby, job, career, vocation/calling, or something else. Participants were asked to describe what that particular term meant for them, and the follow-up questions were developed based on coaches’ responses to delve further into meanings of coaching and to gain more context for what was said. The interviews were audio-recorded and lasted 35–89 min (average 59 min). The interviews in Finland were conducted in Finnish and the interviews in England in English.

Data analysis

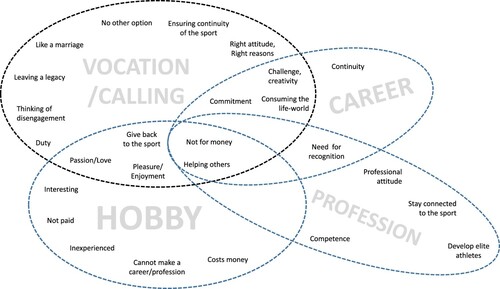

We used thematic narrative analysis to make sense of the data (Riessman, Citation2008; Smith, Citation2016). According to Smith (Citation2016), thematic narrative analysis begins with steps typical to all interview research (transcription, organising the data, familiarisation and note-taking) but then moves to identifying narrative themes or thematic relationships which are patterns or threads that run through the story or set of stories. In our data, we specifically scrutinised the main term chosen by coaches to describe the meaning of coaching (hobby, career, profession, vocation/calling or something else) and the constituent story threads associated with this term. We then sought to understand how these meanings shaped the overall stories the coaches were telling and what other patters emerged repeatedly, and after that compared the identified themes across cases. In line with Smith’s (Citation2016) recommendations, we identified keywords (see ) and key phrases (e.g. “it is not paid” or “it is like a marriage”) that captured meanings identified in the data. We then moved to describing and interpreting the themes. Our interpretation was informed by Lepisto and Pratt’s (Citation2017) conceptualisation of meaningful work as justification. Here, we were asking questions such as “why is coaching worthy work for this coach?” and “what moral and social justifications are given for coaching work here?” As a final step, we represented the findings in a form of realist tale. As Smith (Citation2016) emphasised, since people can always change and create new stories, the product of thematic narrative analysis should be conceived as provisional and not a final word about the participants’ experiences.

Research quality

In line with the realist philosophical position underpinning the study, we constantly sought to identify threats to the validity of our interpretive account (Ronkainen & Wiltshire, Citation2019). We drew on Maxwell’s (Citation2017) concepts of descriptive, interpretive and theoretical validity to guide the process. Descriptive validity refers to accurately capturing what the participants have said (e.g. how many told that they considered coaching to be a hobby, career or vocation). One particular issue was the Finnish word “kutsumus” which can be translated to vocation or calling; we decided to translate the Finnish word to “vocation/calling” to preserve both possible meanings. Interpretive validity refers to our attempts to understand what it means for participants to describe coaching as a career, hobby or vocation/calling, and what other meanings, intentions and hopes were communicated in their overall narratives. To stay close to the data, we represent the results using participants’ own expressions and concepts as much as possible. Finally, theoretical validity refers to scrutinising how well the developed explanation holds for the studied phenomenon and whether alternative theoretical explanations could be more plausible. In our study, all authors were involved in developing, refining and challenging the interpretive account.

Results

In the analysis, we identified both specific meanings that were associated with hobbies, professions, careers and vocations/callings and overlapping themes that transcended these labels (see ). For example, most coaches were animated by the desire to help athletes develop and maintained that money was not the primary reason to coach. Several coaches contemplated on various perspectives (e.g. it could be a profession and a vocation), whereas three coaches did not identify with any of the hobby, profession, vocation/calling or career constructs (e.g. “it is more than a hobby, but it is not a career” and “I guess it is something you enjoy”).

As the analysis progressed, we became increasingly aware of age-related patterns in how participants constructed meaning in coaching and other volunteer work in the sport club. We have illustrated these differences by discussing the findings in three categories based on the age group and the social status: (1) student-coaches in their 20s and early 30s; (2) coaches in their 30s and 40s with an established work career; and (3) coaches in their 50s and older. Age was also an important difference between the national samples: the group of student-coaches only included participants from Finland, and only two of the participants in the sample from England were under 50 years old. Our main focus was not on national differences, because it seemed likely that the age difference was a confounding factor in how coaching was storied. Instead, we focus on the generational differences and how the patterns of structural and cultural changes in sport clubs identified both in England and in Finland shaped the story construction. In the following account, all names of the participants are pseudonyms.

Student-coaches: coaching as a (paid) hobby

All coaches who were university students and could be described as young adults (age 22–32, N = 6) chose to describe coaching (at least partly) as a hobby, while for some, the meanings of coaching were also layered. These coaches were Finnish and were student-coaches who had been coaching for 2.5–15 years (mean 8.75 years), which means that many of them were already fairly experienced coaches. Overall, the student-coaches’ stories often emphasised both intrinsic (sense of accomplishment, doing something interesting, pleasure) and extrinsic (gaining work experience, receiving payment) benefits, which challenges some of the literature indicating a prevalence of instrumental motives in student volunteers. Moreover, similar to older coaches, younger coaches frequently mentioned their desire to help athletes develop and share their knowledge with others, thus drawing on the shared cultural narratives about sports coaching as an other-oriented activity. However, some of them found it difficult to specifically articulate why coaching was worthwhile and why they wanted to do it, as Jonna (20s) exemplifies: “I don’t know. Maybe that you see the result of your work, concretely. That’s really nice. And so it doesn’t feel like a job.”

While the young coaches chose to describe coaching as a hobby, for many of them the career-related meanings (progress in the world of work) also gave shape to the narratives that were shared and provided a justification for commitment to coaching. For instance, several coaches were studying towards a sport- or health-related degree, and in volunteer coaching, they could combine their “hobby” with career development. As Marja (20s) mentioned, “I am studying a field that is related to this, so it is easy to justify that this is something that interests me, and it is also good for like a future profession and work-life”. After completing his studies, Sami (20s) aspired to become a professional coach and explained that “you should find a job that you enjoy doing”.

The student-coaches generally considered receiving payment for coaching and professionalisation of coaching to be positive developments. Although coaching was predominantly viewed as a hobby, it could be “a paid hobby”:

Marja (20s): Well it is more of a hobby, yes, but the club does pay as well. So it is a good way to earn a little while studying. If I were not coaching, I would have to do some other work. So it is good that you can have that kind of hobby.

I know all the feedback that you get [working in a sports club] and how it is, how much the parents will demand and complain. I think the recognition and valuing of the coach has gone down so much. I’m not sure if I could handle it, like full-time. Especially if I went to a club where I was the only one paid full-time staff. Then they would just keep pushing you all the work.

The “middle” group: negotiating shifting meaning of coaching

While the youngest age group was characterised by a “hobbyist” orientation often focused on self-realisation, the middle group of coaches (who had an established work career and were in their 30s and 40s; N = 6, four in Finland and two in England), were ambiguous and fluid in words that they used to describe and justify their coaching. Hobby, profession, vocation/calling, and (volunteer) career were all used often, while some coaches also felt that none of these words were accurate but struggled to articulate a better concept. A common denominator for these coaches’ stories – as opposed to younger and less experienced coaches – was the emphasis on the continuity and seriousness of their commitment to coaching. As Harri (40s) put it,

From the word career, one thinks of the career at work and for me, this is something else … I don’t know how to put it, the career is a bad word to describe it, even if it is the only career that has come along all the way [my adult life]. But it is kind of a volunteer career.

I think it is some kind of vocation/calling. At least [in the beginning] it was clear, there was no other option for my life than to become a coach. I do not know where it came from. Well, I was studying sport science, and I was an athlete. It was the closest thing I could do in the sport (pause). However, it might have changed since. Then, well at one phase, it was partly a job, [then] it changed to be more like a hobby. However, even if I keep looking at it from different angles, I would still see it as some type of vocation/calling, but not the kind that is forcing you to do it.

I have thought that vocation/calling, that is it. And also, it could be a profession or a career. When I was younger, I was thinking that it is no problem for me to do this free of charge. Also now, I partly think this way. I would probably do it for free if I had to. However, for the future and the other coaches as well, so that coaching would get more recognition, it should be more professional. It needs to be thought about as a profession or a career.

The sport has saved my life. I’m not kidding you. I was a young lad, running around, trying to find my way, very hyperactive. And I just needed something. [In sport] I found something that I know will make me feel good. It gave me that satisfaction and everything else that sport gives you. So obviously, coming back to why I would want to coach voluntarily. So why I’m doing that – I still feel connected to the sport and the club that has given me everything. Now it is my turn to put me in a position to help local kids coming through.

The older coaches: tradition, duty and leaving a legacy

Most of the coaches who were in their 50s or over (N = 11, six in England and five in Finland) emphasised that their coaching was a volunteer activity, indicating a sense that amateur motives were considered somehow more “pure”. From these coaches, all except two had been coaching for 20 years or more, with two coaches boasting over 40 years of experience. While some of the coaches in Finland considered the development of the club (increase of professionalisation and more activities on offer) to be positive, the coaches in England made sure to emphasise the amateur ethos of their club and their own involvement. Referring explicitly to the aspect of coaching as a non-paid activity, two of the coaches in England described coaching as a hobby (because people are not paid for hobbies). However, it was clear from the overall narratives of these coaches that the “hobby” involved a strong commitment to the club and a sense of moral duty to contribute, something that was largely absent from younger coaches’ stories about coaching as a hobby. Some coaches explained that there was no one else who was qualified or that no one else had offered to help and that their volunteer roles in the sport often included being an official, board member, club statistician, club president and so forth. Many of them mentioned that they enjoyed their coaching, but at times when they did not particularly enjoy it, they would still do it because it was their moral duty. As Mark (50s) reflected on his current relationship with coaching:

If I am completely honest, I am probably here because I feel committed to being here. Because there are no other coaches around in my event, there is nobody to take over. If I am not here, sessions do not happen. And I feel guilty just leaving the youngsters and some of the older athletes that I look after. You know, they are keen and I don’t want to let them down.

Two coaches in their 50s described coaching as similar to a profession in the sense that they had a fully professional attitude to their coaching work. For them, coaching was not “a hobby” because that had a connotation of not taking it seriously, whereas these coaches were strongly committed to working to offer the best possible advice for each athlete. As Tomi (50s) reflected: “Well, my first goal is to be remembered as a person who did for his athletes what could be done.” Their emphasis on accumulated expertise and experience linked to the theme of “giving back” and helping athletes to reach their goals (which was also a theme shared by younger coaches), but they also linked this narrative to a broader concern of leaving a legacy.

Five coaches in their 50s and older described coaching without hesitation as a vocation/calling in the neo-classical sense where it gains meaning as a commitment to working towards a cause that transcends the self. In a follow-up question to what it means in his coaching, Mika (50s) offered:

A vocation/calling means that in your heart, you feel that it is yours. It is almost like a marriage. It, it lasts. Even if it does not go so well sometimes, and other times it goes well, it lasts. Because the foundation is so strong, you feel that is something that is yours. A vocation/calling means that the thing gives you a lot but also that you have something to give. That you feel that you can give.

A lot of the reasons why, characteristics of the person that makes them want to do this, they don’t look good. Mm. Unless you are like completely altruistic. Mother Theresa like, just totally giving, mm, then there is usually self-interest involved (…) coaches are probably screwed up people (laughing) because you have got to be opinionated, you have got to be confident, overconfident, you probably got to be happy controlling people. None of these is an ideal characteristic, is it? A perfectly rounded human being …

Finally, many of the older coaches were careful to emphasise the broader justification of their work and the importance of preserving both the club and the sport as a whole for future generations. Some of them lamented the current state of athletics (compared to the glorious past) and commented on sports policy (often in a highly critical voice when it came to participation targets and perceived decline of performance in some events). When asked about his views on the future of the club and his role within it, John (50s) responded: “Listen, nobody is bigger than the club, it has a long history behind it.” Mika (50s) also considered ensuring the continuity of the sport and his club more important than his athletes’ success:

Well, the fundamental idea that I’ve had with all my athletes, even if they would not become elite competitors in the senior level, that they would still maintain this kind of spark for athletics that I have. So that they would continue being involved in athletics, in the club, as a coach, as an instructor, an official, an organiser for the competitions, in the administration. Actually, these are more important tasks than doing the sport. These people make it possible for others to keep doing the sport.

We do things for the right reasons, for the club. Things that are in the interest of the club and its members. And no one has any egos or their own set agenda. We are here to run an athletics club and we want to be successful. And I think it is because the committee and the secretary, we all have been there for a long time. And I would say I hope this will all continue long after we’re all gone.

Discussion

Through the analysis of narrative interviews, we sought to discern how athletics coaches make meaning of their involvement in coaching and what narrative resources they tap into in justifying coaching as worthwhile work. We showed that coaches at different life stages tended to describe coaching with different core metaphors (hobby, career, profession, and vocation or calling) and that these metaphors were also associated with different levels of reflection and meaning-making in coaching. Taken together, all participants’ stories exemplify that sports coaching is strongly culturally scripted as an other-oriented activity with notable personal benefits. This observation supports Hustinx and Lammertyn’s (Citation2003) assertion that “we are not confronting a complete rupture between two historically different social forms [of volunteer commitment]” (p. 171); however, the sport volunteer sector’s ideological shift from mutual aid to market-driven service delivery (Grix, Citation2009; Nichols et al., Citation2005) was reflected more strongly in younger coaches’ stories. Older coaches, while also acknowledging the personal benefits of coaching, more often made meaning of coaching within traditional sport volunteering cultural narratives that centralise mutual aid and “giving back” to the sport. The rupture of the cultural horizon of meaning could render it more difficult for clubs to maintain a shared vision of why they are making a meaningful contribution to society and to sustain member solidarity. This rupture might be particularly pronounced in clubs that still retain the “voluntary service identity” (ICCE et al., Citation2013) such as the English club in our study.

Reading the coaches’ stories through the conceptualisation of meaningful work as justification (Lepisto & Pratt, Citation2017) reveals that different core metaphors of coaching were also associated with different accounts of why coaching is a worthwhile activity. While the younger coaches who predominantly considered coaching a hobby seemed motivated by both intrinsic (e.g. enjoyment) and extrinsic (e.g. gaining work experience) factors, their stories were fairly thin in justifying the worthiness of coaching work and connecting it to wider existential considerations about what is good and valuable. Since justifications depend on narrative resources that are at individuals’ disposal, it seems plausible to suggest that the new service-delivery models of sport clubs and coaching provision might not provide new coaches strong interpretive resources for justifying why the coaching work is worth doing (beyond the personal benefits). Other scholars (e.g. Dean, Citation2014; Hayton, Citation2016) have argued that there might be a sustainability problem in the volunteer sector because young volunteers adopt instrumental approaches to volunteering; from a meaningful work perspective, the “problem” might not (only) be located in their lack of intrinsic motivation, but in the more existential issue of being able to justify why coaching is worthy work. In contrast, the older coaches, many of whom described coaching through the neoclassical concept of vocation/calling, were articulate about why coaching is worthwhile and how their efforts contribute to causes that transcended the here-and-now (e.g. preserving the club and the sport to future generations, leaving a legacy). This conceptualisation of meaningful work as justification brings a different perspective to coach recruitment and retention research which has often centred on the construct of motivation (e.g. Dean, Citation2014; Hayton, Citation2016). That is, it will direct us to look into different aspects of the coaching experience in addition to intrinsic (e.g. sense of enjoyment) and extrinsic (e.g. employability) types of motivation.

The coaches in our research who perceived coaching as a neoclassical vocation or calling appeared to hold dual motives of what Cuskelly et al. (Citation2002) described as “marginal” sport volunteers (e.g. giving back to the sport, a sense of duty/obligation, “there was no one else”) and “career” volunteers (e.g. the love of the sport, desire to pass on knowledge, value congruence with the club). While Cuskelly et al. (Citation2002) found that “career” volunteers were more committed than “marginal” volunteers, in our study it was clear that the motives of duty and giving back to the sport were significant aspects of why many coaches were committed to their work. As Lepisto and Pratt (Citation2017) argued, when meaningfulness of work is derived from the justification perspective (the moral worth of work), people might be more persistent in pursuing it despite the self-sacrifices that can be required. Indeed, the sense of moral duty and responsibility is often associated with neoclassical callings, where people are willing to put the benefit of others or a greater cause ahead of their own desires and needs (e.g. Bunderson & Thompson, Citation2009). As Nichols et al. (Citation2005) also noted, traditional notions of citizenship involve an idea that some individuals and groups are willing to make sacrifices for the benefit of others and the community. This highlights that research into motivations of coaches needs to be complemented with research into the meaning and existential significance of coaching work for the individuals involved.

While the findings indicate that younger and older coaches tell partly different stories to make sense of the meaning of coaching in their lives, the underlying reasons for these findings should be interpreted with caution and in relation to multiple possible explanations. From a narrative perspective, we observed that participants’ stories followed closely the culturally scripted “ideal” life course development (Erikson, Citation1959), with young adults storying coaching more (although not exclusively) from a self-focused perspective, and coaches in mid- and later life drawing on more generative and self-transcendent understandings of coaching. While the younger coaches could be characterised as “new” volunteers (Hustinx & Lammertyn, Citation2003), it is still possible that, as they age, they will shift from an understanding of coaching as a hobby to a career, profession or vocation/calling. Meanings in volunteering often change over time (Cuskelly et al., Citation2002; Hayton, Citation2016). From a narrative theoretical perspective, it is again plausible to suggest that participants’ self-narratives may well change over time as they accumulate more experiences, contemplate on why coaching is worthwhile, and shift to a different developmental position in the culturally scripted life course.

The study findings should be interpreted with several limitations in mind. First, in relying on single narrative interviews that focused on the overall patterns of meaning, the study did not shed light on inconsistencies, ambiguities, and shifts of meaning in coaching. While the study provides initial insight into meaningful work in coaching, the study gives limited attention to the complex processes of how justifications and career meanings are developed, contested and transformed over time. Due to the demographic differences in our samples in the two countries (as well as the limits of space), we could not draw conclusions on the role of national culture differences in how coaching is meaningful for participants. Similarly, we could not delve into issues such as class, gender and many other elements of cultural identity and how they shape participants’ stories. Nevertheless, we hope that this initial investigation of hobbies, careers and callings in sport coaching will stimulate future research to meaningful work in coaching. Longitudinal studies would be extremely valuable for understanding how meaning in coaching develops over time and what implications it has for coaches’ well-being and commitment.

Conclusions

The present study contributed to literature on coach recruitment and retention from the perspective of meaningful work, showing that there can be significant differences in how younger and older sport coaches find meaning in coaching and how they justify it as worthy work. We offered an alternative perspective to that offered by research on coach motivations, suggesting that the “problems” the volunteer coach sector is facing might not solely lie in actors’ lack of intrinsic motivation, but relate to the justification of coaching as a morally worthy activity. Given that many coaches who had a strong sense of work significance and purpose drew on the traditional volunteering ideology and neoclassical notions of vocation and calling, the broader structural and cultural shifts towards a neoliberal notion of volunteering can be seen as a source of concern. From a practical perspective, sport clubs need to be aware of different meanings that volunteers of different age and experience assign to coaching. Sport clubs ought to also focus on clarifying the values they stand for and be aware that some of the narrative resources that have been vital for constructing meaningful coaching work (at least with the older generation of coaches) are becoming marginalised in the new culture of professionalisation. While scholars have warned against managerialist approaches to “management of meaning” (which signifies invading the existential domain of workers; Lips-Wiersma & Morris, Citation2009), increasing awareness of diversity in how volunteers construct meaning in coaching and creating opportunities to sustain meaning and fulfilment appears like a reasonable suggestion.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our participants for sharing their stories, Callum Tonge for assistance in the data collection, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Dik and Duffy (Citation2009) suggested that vocation and calling are conceptually distinct in that only calling involves a source beyond the self (“transcendent summons”). However, this distinction is not widely adopted, some scholars use the terms interchangeably, and others use one of them only. Generally, the literature now favours calling over vocation.

References

- Bailey, C., Yeoman, R., Madden, A., Thompson, M., & Kerridge, G. (2019). A review of the empirical literature on meaningful work: Progress and research agenda. Human Resource Development Review, 18(1), 83–113. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484318804653

- Bellah, R. N., Madsen, R., Sullivan, W. M., Swidler, A., & Tipton, S. M. (2008). Habits of the heart, with a new preface: Individualism and commitment in American life. University of California Press.

- Berntsen, D., & Rubin, D. C. (2004). Cultural life scripts structure recall from autobiographical memory. Memory & Cognition, 32(3), 427–442. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03195836

- Breuer, C., Hoekman, R., Nagel, S., & van der Werff, H. (2015). Sport clubs in Europe. Springer.

- Bunderson, J. S., & Thompson, J. A. (2009). The call of the wild: Zookeepers, callings, and the double-edged sword of deeply meaningful work. Administrative Science Quarterly, 54(1), 32–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2009.54.1.32

- Cuskelly, G., Harrington, M., & Stebbins, R. A. (2002). Changing levels of organizational commitment amongst sport volunteers: A serious leisure approach. Leisure/Loisir, 27(3-4), 191–212. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2002.9651303

- Day, D. (2017). The British athlete “is born not made” Transatlantic tensions over sports coaching. Journal of Sport History, 44(1), 20–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5406/jsporthistory.44.1.0020

- Day, D., & Carpenter, T. (2015). A history of sports coaching in Britain: Overcoming amateurism. Routledge.

- Dean, J. (2014). How structural factors promote instrumental motivations within youth volunteering: A qualitative analysis of volunteer brokerage. Voluntary Sector Review, 5(2), 231–247. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1332/204080514X14013591527611

- Dik, B. J., & Duffy, R. D. (2009). Calling and vocation at work: Definitions and prospects for research and practice. The Counseling Psychologist, 37(3), 424–450. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000008316430

- Dik, B. J., & Shimizu, A. B. (2019). Multiple meanings of calling: Next steps for studying an evolving construct. Journal of Career Assessment, 27(2), 323–336. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072717748676

- Dobrow, S. R., & Tosti-Kharas, J. (2011). Calling: The development of a scale measure. Personnel Psychology, 64(4), 1001–1049. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01234.x

- Duffy, R. D., & Dik, B. J. (2013). Research on calling: What have we learned and where are we going? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83(3), 428–436. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.06.006

- Erikson, E. H. (1959). Identity and the life cycle: Selected papers. International Universities Press.

- Geldenhuys, M., Laba, K., & Venter, C. M. (2014). Meaningful work, work engagement and organisational commitment. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 40(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v40i1.1098

- Grix, J. (2009). The impact of UK sport policy on the governance of athletics. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 1(1), 31–49. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940802681202

- Hammersley, M. (2003). Recent radical criticism of interview studies: Any implications for the sociology of education? British Journal of Sociology of Education, 24(1), 119–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690301906

- Hayton, J. W. (2016). Plotting the motivation of student volunteers in sports-based outreach work in the North East of England. Sport Management Review, 19(5), 563–577. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2016.06.004

- Hustinx, L., & Lammertyn, F. (2003). Collective and reflexive styles of volunteering: A sociological modernization perspective. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 14(2), 167–187. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023948027200

- International Council for Coaching Excellence (ICCE), Association of Summer Olympic International Federations (ASOIF), & Leeds Metropolitan University (LMU). (2013). International sport coaching framework version 1.2. Human Kinetics.

- Koski, P., & Mäenpää, P. (2018). Suomalaiset liikunta-ja urheiluseurat muutoksessa 1986−2016. Opetus- ja kulttuuriministeriön julkaisuja, 25.

- Lepisto, D. A., & Pratt, M. G. (2017). Meaningful work as realization and justification: Toward a dual conceptualization. Organizational Psychology Review, 7(2), 99–121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2041386616630039

- Lips-Wiersma, M., & Morris, L. (2009). Discriminating between ‘meaningful work’ and the ‘management of meaning’. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(3), 491–511. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0118-9

- Llewellyn, M. P. (2012). ‘The best distance runner the world has ever produced’: Hannes Kolehmainen and the modernisation of British athletics. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 29(7), 1016–1034. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2012.679026

- Martela, F., & Pessi, A. B. (2018). Significant work is about self-realization and broader purpose: Defining the key dimensions of meaningful work. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 363. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00363

- Maxwell, J. A. (2017). The validity and reliability of research: A realist perspective. In D. Wyse, L. E. Suter, E. Smith, & N. Selwyn (Eds.), The BERA/SAGE handbook of educational research (pp. 116–140). SAGE.

- Misener, K., Doherty, A., & Hamm-Kerwin, S. (2010). Learning from the experiences of older adult volunteers in sport: A serious leisure perspective. Journal of Leisure Research, 42(2), 267–289. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2010.11950205

- Molloy, K. A., Dik, B. B., Davis, D. E., & Duffy, R. D. (2019). Work calling and humility: Framing for job idolization, workaholism, and exploitation. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 16(5), 428–444. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2019.1657489

- Nichols, G., Taylor, P., James, M., Holmes, K., King, L., & Garrett, R. (2005). Pressures on the UK voluntary sport sector. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 16(1), 33–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-005-3231-0

- North, J. (2009). The UK coaching workforce. Sports Coach UK.

- Potts, A. J., Didymus, F. F., & Kaiseler, M. (2019). Exploring stressors and coping among volunteer, part-time and full-time sports coaches. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(1), 46–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2018.1457562

- Principi, A., Schippers, J., Naegele, G., Di Rosa, M., & Lamura, G. (2016). Understanding the link between older volunteers’ resources and motivation to volunteer. Educational Gerontology, 42(2), 144–158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2015.1083391

- Puska, M., Lämsä, J., & Potinkara, P. (2017). Valmentaminen ammattina Suomessa 2016. Jyväskylä: Kilpa-ja huippu-urheilun tutkimuskeskus KIHU:n julkaisusarja 53.

- Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage.

- Ronkainen, N. J., & Wiltshire, G. (2019). Rethinking validity in qualitative sport and exercise psychology research: A realist perspective. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2019.1637363

- Ryba, T. V., Aunola, K., Kalaja, S., Selänne, H., Ronkainen, N. J., & Nurmi, J. E. (2016). A new perspective on adolescent athletes’ transition into upper secondary school: A longitudinal mixed methods study protocol. Cogent Psychology, 3(1), 1142412. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2016.1142412

- Shilbury, D., & Ferkins, L. (2020). An overview of sport governance scholarship. In D. Shilbury & L. Ferkins (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of sport Governance (pp. 3–17). Routledge.

- Smith, B. (2016). Narrative analysis in sport and exercise: How can it be done. In B. Smith & A. Sparkes (Eds.), Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise (pp. 260–273). Routledge.

- Steensen, J. (2006, August 11–13). Biographical interviews in a critical realist perspective [Paper presentation]. IACR Annual Conference, University of Tromsø.

- Taylor, B., & Garratt, D. (2010). The professionalisation of sports coaching: Relations of power, resistance and compliance. Sport, Education and Society, 15(1), 121–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13573320903461103

- Taylor, R., & Roth, S. (2019). Exploring meaningful work in the third sector. In R. Yeoman, C. Bailey, A. Madden, & M. Thompson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of meaningful work (pp. 257–273). Oxford University Press.

- Thompson, B., & Mcilroy, J. (2017). Coaching in the UK. Coach survey. The National Coaching Foundation.