ABSTRACT

Purpose/Rationale:

Helping individuals and teams achieve their goals by being resilient is an established research field in sport. How sport organisations can be resilient in adversity is comparatively neglected, so the purpose is to provide firm foundations for conceptualising organisational resilience in sport management.

Research question:

“How can organisational resilience best be theorised for sport management research and practice?”

Design/Methodology/Approach:

From a critique of the resilience literature, a new Framework for Organisational Resilience Management (FfORM) is developed, based on the theory of organisational resource conversion and the separation of normative and descriptive levels. The FfORM is applied to sport management contexts, including the resilience of National Governing Bodies of Sport (NGBs) to reductions in UK Sport funding.

Results and Findings:

Organisational resilience is conceptualised as a means to an end, to achieve externally generated goals, emphasising its dynamic, temporal nature. The FfORM illuminates the challenges for NGBs in developing organisational resilience because of trade-offs in the actions they take.

Practical implications:

As well as being an evaluation tool, the FfORM will be of utility to sport organisations addressing the unprecedented challenges arising from COVID-19.

Research contribution:

Development of theory on organisational resilience, for use in both sport and other contexts.

1. Introduction

Sport organisations face many challenges because of different stakeholder interests, performance-related funding regimes and the complexity of the macro-environmental context (De Bosscher et al., Citation2019; Feddersen et al., Citation2020; Green, Citation2007; Kasale et al., Citation2018; Pedras et al., Citation2020). The Covid-19 pandemic presents new threats for sport management at both elite and grassroots levels (Parnell et al., Citation2020), as well as possible opportunities (Hammond, Citation2020). In this context, the concept of organisational resilience, for which a standard definition is “the ability of an organisation to anticipate, prepare for, respond and adapt to incremental change and sudden disruptions in order to survive and prosper” (Denyer, Citation2017, p. 5),Footnote1 becomes very relevant to National Governing Bodies of Sport (NGBs) and wider networks of sports organisations (Warner, Citation2020). Internationally, governments have set up “Resilience Funds” to help sport organisations survive the pandemic in the short term (Department of Transport, Tourism and Sport for Ireland, Citation2020; Sport New Zealand, Citation2020), while sports institutions and infrastructure are being linked to the wider resilience of nations (Begović, Citation2020) and local communities (Orr & Kellison, Citation2020).

There is a burgeoning literature on resilience in business and management (Linnenluecke, Citation2017) and public administration (Duit, Citation2016) but very few studies have, hitherto, applied the concept of resilience to sport organisations. The resilience literature in sport is mainly in the field of individual and team performance, as a branch of sport psychology (Bryan et al., Citation2019; Galli & Gonzalez, Citation2015). Sport management literature on organisational resilience is developing in specific sub-fields, such as grassroots responses to natural disasters (Filo et al., Citation2015; Wicker et al., Citation2013), the wider implications of climate change for the management of sport (Dingle & Stewart, Citation2018; Orr & Kellison, Citation2020), sport and national resilience (Sam, Citation2015) and managing crises in sport tourism (Shipway, Citation2018). However, overall, the organisational resilience literature in sport management is in its infancy.

In other disciplines, there have been critical debates on the nature of resilience (Brand & Jax, Citation2007; Hassler & Kohler, Citation2014; Martin & Sunley, Citation2015; Strunz, Citation2012) and literature reviews have argued that the concept is highly context dependent (Duit, Citation2016; Linnenluecke, Citation2017). In view of the early stage of development of the organisational resilience literature in sport management, there is an opportunity to use critiques from other fields and interdisciplinary insights to inform the question, “How can organisational resilience best be theorised for sport management research and practice?”

The organisational resilience literature often makes the normative assumption that resilience is a “good thing” (see Gibson & Tarrant, Citation2010; Valikangas, Citation2010). Gibson and Tarrant (Citation2010) identified eight different conceptual models in use, all aimed at enhancing organisational resilience as an outcome – as an end in itself. In many fields, this approach to theorising about resilience has been identified as a concern, because it may lead to oversimplistic prescriptions which do not reflect the trade-offs in actions to enhance resilience (Boin & Van Eeten, Citation2013; Brand & Jax, Citation2007; White & O'Hare, Citation2014). Therefore, a clear distinction between descriptive and normative theory components is required (Danermark et al., Citation2002; Strunz, Citation2012). This article uses Strunz (Citation2012) transdisciplinary “resilience thinking” research categories to achieve this separation, with the normative level of “target knowledge” (sustainability) being distinguished from “systems knowledge”, at the empirical, descriptive level (resilience). Goals need to be determined first, then resilience becomes an ability to consistently achieve high performance for those system goals, in the face of major disruptions and stressors. Resilience becomes a means to an end, with sustainability being the concept associated with the “ends” of sports organisations.

This perspective requires that prescriptions for organisational resilience need to be underpinned by an understanding of the relations between organisational characteristics, processes and outcomes (Boin & Van Eeten, Citation2013). To provide a framework to enable this to be achieved, this paper draws upon organisational resource conversion (Capon, Citation2009), a general descriptive model of organisational activity, in which human, tangible and intangible resource inputs are converted through organisational processes into outputs. Sports organisations engage in resource conversion to achieve their goals, while being impacted by external stressors which test their resilience.

The resulting Framework for Organisational Resilience Management (FfORM) will be applied to sport management contexts, enabling the transition from the conceptual level to a specific organisational context to be undertaken systematically and transparently. The framework is of utility both for sport management research and to sport organisations seeking to become more resilient, whether that is anticipating future stressors or reacting to disruptions which have recently occurred. The examples given are mainly for NGBs for Olympic sports in the UK, but it could also be used for other types and sizes of sports organisations, in any country. While the applications of the framework have been tailored to sport management, the generic nature of the framework means that it could also be used in other fields. Therefore, the paper makes an incremental contribution to knowledge by addressing an area of relative neglect in the sport management literature, and a revelatory contribution to the interdisciplinary organisational resilience literature, by using multiple lenses to develop a new theoretical framework (Nicholson et al., Citation2018).

The next section reviews the literature on resilience in sport, to identify the research gap in more detail, the key themes for theoretical development and the implications for the definition of resilience. Then the rationale behind the FfORM and its components are explained and applied to the sport management context. A specific example of a major stressor is used in this section, the fluctuations in funding allocated by UK Sport (the body responsible for distributing funding to Olympic/Paralympic NGBs in the UK). Finally, the practical utility of the FfORM is outlined regarding the future challenges for sport organisations arising from the impacts of COVID-19 and suggestions for further research are proposed.

2. Themes in the resilience literature in sport

2.1. Resilience at an individual and team level

While the sport psychology literature has always identified resilience as a dynamic process (Galli & Gonzalez, Citation2015), recently resilience has been viewed as a process of continuous adaptation and growth from stressors (Bryan et al., Citation2019). Hill et al. (Citation2018a) advocate a “dynamical systems approach” which incorporates the “iterativity” of resilience, whereby the current and future state of a system is borne out of its previous states. A given variable can be an effect in one moment and then act as a cause in the next, as resilience is the product of the inter-relationships between individual protective factors and environmental demands (Hill et al., Citation2018a), mediated by further factors such as cognitive appraisal of an event (Hill et al., Citation2018b). A research priority is, therefore, to focus on understanding the “temporal process of resilience” (Hill et al., Citation2018b). However, the when of resilience is not the only key component of theory building; according to Bryan et al. (Citation2018), what, how and where questions also need to be addressed.

As part of the development of the “dynamical systems approach”, Kiefer et al. (Citation2018) suggest that when experiencing a stressor, the goal for the athlete is to thrive in adversity. Rather than just returning to their previous state, they aspire to “antifragility” (Taleb, Citation2012) rather than mere resilience. Changes in training models are seen as critical for achieving resilience (Hill et al., Citation2018a), or even antifragility (Kiefer et al., Citation2018), but the organisations responsible for training methods are not the central focus of this research.

2.2. Research at an organisational level

There have been very few studies that have applied the concept of organisational resilience to the sport sector, although, over ten years ago, Fletcher and Wagstaff (Citation2009) stated that: –

Since international level sport has never been so competitive, NSOs [National Sport Organisations] will likely need to meet the challenges, adversities and changes associated with the developments in elite sport governance. Despite these observations, there is currently no rigorous research that specifically addresses performance management or organizational resiliency in elite sport (p. 433).

Despite this call, the authors are not aware of any studies that have focused specifically on the resilience of elite sport organisations. Use of the term resilience in studies of sports organisations and events have focused on stressors from the natural environment, such as natural disasters (Filo et al., Citation2015; Shipway, Citation2018; Wicker et al., Citation2013) and climate change more generally (Dingle & Stewart, Citation2018). Therefore, the theories of resilience which tend to underpin this work are from natural disaster/climate change studies. For example, Wicker et al. (Citation2013) applied Bruneau et al.’s (Citation2003) multi-dimensional framework for community seismic resilience to sport clubs affected by flooding and a cyclone. Bruneau et al. (Citation2003) asserted that resilience of both physical and social systems can be defined through four properties – robustness, redundancy, resourcefulness, and rapidity. Wicker et al. (Citation2013) identified sources of organisational resilience in the substitutability of resources, the ability to mobilise members during a crisis, the size (number of members) of the organisation, the heterogeneity of the sport and the generalisability of job roles. Filo et al. (Citation2015) built upon the previous study by using Resource Dependence Theory (Hillman et al., Citation2009) for a qualitative study of sport clubs affected by the same natural disasters. The use of this theory from the strategic management literature identified how power relations between different stakeholders were critical in securing resources for recovery.

While there are no studies which have researched resilience of sport organisations to stressors from the sport management systems of which they are a part, many studies have addressed this implicitly. Most notably, there have been many studies researching the effects of reductions in funding due to national policies on targeting financial allocations (Berry & Manoli, Citation2018; Bostock et al., Citation2018; De Bosscher et al., Citation2019) and the effects of austerity (Giannoulakis et al., Citation2017; Parnell et al., Citation2019). These publications have explored the strategies of sport organisations faced with funding cuts, which can be viewed as a major stressor, and evaluated the effectiveness of those strategies.

2.3. What can be learnt from sport?

Despite the uneven development of resilience as a concept in sport, there are some key themes from the extant literature which are relevant for theorising organisational resilience for sport management research and practice. The first theme is the dynamic nature of resilience and how this has been developed at the conceptual level to emphasise the temporal interdependencies and trajectories of systems in sport (Hill et al., Citation2018a). The limitations of cross-sectional research are recognised (Hill et al., Citation2018b; Wicker et al., Citation2013), but few temporal process or longitudinal studies have been undertaken so far. The literal and metaphorical conceptualisations of resilience have in common a reference to time, whether it is the original meaning of “bouncing back” (Martin & Sunley, Citation2015) or the ability to adapt to disruptions in order to survive and prosper (Denyer, Citation2017). However, the timescale used varies immensely, from a few weeks for a hospital recovering from a single stressor, such as an outbreak of a contagious disease, to hundreds of years, when explaining the longevity of the system of local government in England in the face of multiple stressors (John, Citation2014). Therefore, a timeline related to stressor events must be at the heart of the theorisation of resilience.

The second theme is the importance of linking performance management and resilience together. So far, this link has mainly been approached from the angle of the performance of the individual or team (Bryan et al., Citation2019; Molan et al., Citation2019). However, if the focus is on organisational resilience the close relationship with performance is still valid, particularly given the impact of performance management regimes on sport organisations (O’Boyle & Hassan, Citation2014). Sport organisations have a combination of sport, financial, organisational and social factors contributing to their performance, and must take account of the priorities of many different stakeholder groups (Bayle & Robinson, Citation2007; Kasale et al., Citation2018). Using Strunz (Citation2012) transdisciplinary research categories, performance management can be viewed as the operationalisation of the sustainability level where targets are identified, reflecting values and priorities at the system level. In sport, the targets have often been narrowly defined, rather than incorporating a mix of sport, financial, organisational and social criteria (De Bosscher et al., Citation2019; Green, Citation2007; Sam, Citation2012).

An important distinction is the difference between the resilience of the organisation itself as opposed to the resilience of the services provided to its users (Bovaird & Quirk, Citation2013), which is particularly critical where there is a high degree of “publicness”, as is the case for most sports organisations (Bostock et al., Citation2020). Bovaird and Quirk (Citation2013) argue that for such services, the nature of risk and resilience within the service system as a whole needs to be identified and strategies developed which give primacy to the interests of service users, while recognising the multiplicity of stakeholders. This suggests that the identification of system goals is required first, as a separate step, so that there is a firm basis for evaluating different actions to achieve resilience.

Combining the two themes above leads to a new definition of organisational resilience, as an ability to consistently achieve high performance for system goals, in the face of major stressors, over a given timescale. Compared to the British Standard/International Standard definition referred to above (Denyer, Citation2017), our definition refers to performance for system goals, rather than for the organisation to “survive and prosper”, and the processes to achieve resilience are not specified. As an example of the dangers in making assumptions about processes and outcomes in definitions of resilience, studies of both private and public sector organisations have found that proactive adaptation does not necessarily increase survival rates (Boin et al., Citation2017).

The “referential contextuality” questions (Virtanen, Citation2013) of how, why, what, where, when and who (H5W) (Barbieri et al., Citation2018; Whetten, Citation1989) have been used in many disciplines, including sport, to develop theories on organisational resilience. As referred to above, Bryan et al. (Citation2018) used what, how, where and when questions for theory building on resilience in sport psychology. In studies of socio-ecological systems, a list of simple questions was formulated, covering resilience of what, resilience to what and resilience for whom (Lebel et al., Citation2006). In economic geography, Martin and Sunley (Citation2015) identified four questions relevant to regional economic resilience: resilience of what, to what, by what means and with what outcome. In public management, White and O'Hare (Citation2014) analysed the impact of resilience as a concept on spatial planning based on three questions, which resilience, why resilience and whose resilience, while Duit (Citation2016) used the questions what is it that is supposed to be resilient and when something can be considered resilient in his critique of the use of the term in public administration. These examples demonstrate the utility of “referential contextuality” questions (Virtanen, Citation2013), but none of these studies address them comprehensively. In particular, there is little attention paid to how in most of these articles.

3. The framework for organisational resilience management (FfORM)

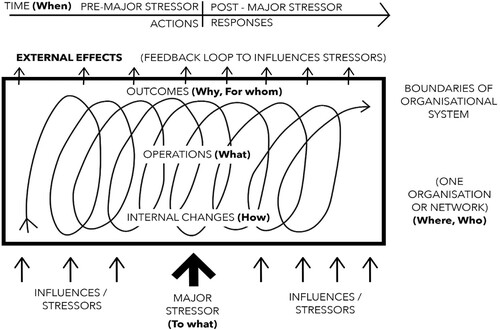

This section will explain the rationale behind, and the components of, the FfORM. It is applied here to the sport management context, although as a general descriptive theory it could be used for any organisational context. It builds upon the themes identified in the discussion of the sport resilience literature concerning the dynamic nature of resilience over time and the links between resilience and performance management. It includes all H5W questions and draws on the resilience literature to add for whom and to what (Lebel et al., Citation2006). The framework is summarised in , with the eight questions shown in bold.

Figure 1. Framework for Organisational Resilience Management (FfORM). Copyright James Bostock and Richard Breese 2021 Creative Commons 4.0 International Licence, BY-SA.

The structure of the framework is based on the organisational resource conversion process (Capon, Citation2009), a development of the strategic management input-throughput-output model which is commonly used in the sports management literature (De Bosscher et al., Citation2019). It involves the identification of an organisation or organisational system, within which resource conversion takes place, with inputs being utilised in operations to achieve outcomes for the organisation/organisational system (Capon, Citation2009) as part of its value chain (Porter, Citation1985). External influences, including minor and major stressors, impact upon the inputs, affecting operations and hence outcomes. includes a major stressor, preceded by anticipatory actions and followed by post-stressor responses. If resilience is defined in performance terms using measurable outcomes, these changes within the organisational system will be aimed at maintaining outcome levels (resilience) or even enhancing them (antifragility), despite the major stressor. Based on Strunz (Citation2012), the normative “sustainability” level of “target knowledge” lies outside the FfORM and will identify which outcomes are the ones to be used for measuring resilience. In addition to the arrows shown in , the relationship between the organisational system and its environment will be two-way, with feedback loops from outcomes back to the influences/stressors.

To demonstrate the application of the FfORM as a whole, the section includes a case study of the challenges facing elite Olympic sport NGBs in the UK from a specific major stressor, the fluctuations in government funding over the last 20 years. These NGBs receive public funding channelled through UK Sport, based on a four year cycle, to support elite level athletes and teams, running training programmes and events, to meet targets set by UK Sport on performance in major international competitions. provides a description of how the different components of the FfORM apply to the case study. The case study is based on data from secondary sources, including time series of funding allocations by sport (see Supplemental file).

Table 1. A conceptual framework for resilience for NGBs funded by UK Sport (Elite Olympic sport).

In the early twenty-first century, funding from UK Sport has been channelled towards sports meeting or exceeding their targets, leading to a concentration of funding on a fewer number of sports (Bostock et al., Citation2018), a trend also found in many other countries (De Bosscher et al., Citation2019; Sam, Citation2012). This alignment of funding with performance means that NGBs managing over time to turn around a reduction in UK Sport funding could be assumed to have displayed resilience, certainly in the funding allocations made for the period 2000–2020. The latest announcement of funding for 2021–2025 includes an increase in the number of sports supported and has had to be made in advance of the postponed Tokyo Games (UK Sport, Citation2020).

Because changes over time are integral to all definitions of resilience, includes a timeline for when, so that the timescales for the study and the points at which resilience is being investigated are clear from the outset. When needs to be related to the nature of the influences and stressors being researched (to what in ). For Olympic sport NGBs, the four-year interval between Olympic Games determines the timing of funding decisions and their implementation (). The changes in funding from one cycle to the next can be very significant, whether measured by the amount involved or the percentage change (Supplemental file).

Resilience studies generally distinguish between the actions undertaken in anticipation and those which address the effects after a stressor has occurred (Wildavsky, Citation1988). Therefore, divides time regarding a major stressor into the prior adjustments before the event and the response afterwards. However, it is very rare for there to be one major stressor, without other subsidiary influencers/stressors also occurring on a frequent basis. While UK Sport’s funding of elite Olympic sport covers a four-year period, NGBs also face annual reviews of performance through measures such as “milestone targets” ().

Where, who and what questions will depend on how organisational boundaries are drawn and the remit of each organisation within this structure. For example, for Olympic sport in the UK there are usually separate NGBs for the elite level, covering the whole of the UK, and for grassroots sport, covering one of the home nations (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland). In contrast, in countries such as Australia and Canada, NSOs generally cover both “high performance” and “participation” levels, but operate in a federated model, overseeing provisional/state organisations which in turn oversee local sports clubs (Parent et al., Citation2018; Pedras et al., Citation2020). The governance structure for each sport in each country determines the administrative boundaries influencing organisational systems, which are always complex and embody a wide range of different stakeholders ((Bostock et al., Citation2020; Parent et al., Citation2018; Pedras et al., Citation2020). For elite sport NGBs in the UK, the relative weakness of “home nation” and regional levels in their governance structure creates a challenge as to how they engage with their stakeholders across the whole of the area they cover. Having separate NGBs for elite and grassroots sport hinders the implementation of policies which rely on the links between them, such as elite sport development pathways (Bostock et al., Citation2018) and legacy benefits of sports mega-events (Grix et al., Citation2017).

Decisions on the boundaries of the organisational system are linked to the why and for whom questions. Why be resilient needs to be considered alongside for whom, because all key outcomes against which resilience is measured have different implications for different stakeholders (Kasale et al., Citation2018). Developing the arguments made above based on Bovaird and Quirk (Citation2013), in a sporting context a crucial distinction concerns the sustainability/resilience of an organisation, such as an NSO, and the sustainability/resilience of the sports clubs and activities that it supports. This would be manifested in decisions such as the allocation of resources for core staff and back-office functions for the NSO as opposed to grants for athletes and teams. Based on Bovaird and Quirk’s (Citation2013) argument, the who of resilience should include all clubs and paid staff/volunteers managing sporting activities, and for whom should cover all those playing the sport, who are the “service users” for the NSO in the organisational system. Measures should be taken to ensure that the interests of service users are given due recognition amongst all the stakeholders in why and for whom debates. In terms of Kasale et al.’s (Citation2018) theoretical model of performance management for NSOs, the organisational system would be drawn to include the micro- and meso-environments of the NSO. Those stakeholders from the macro environment, comprising international sport federations, government, national sport agencies, sponsors, media and wider community interests would be outside the organisation system and would be the source of influences/stressors on that system.

Why and for whom questions inform system goals, and hence the link between normative (sustainability) and descriptive (resilience) levels. The full range of outcomes from the organisational system can be treated as a descriptive attribute in the FfORM (see ), but key outcomes to achieve organisational goals will form the indicators for which consistently high performance in the face of external stressors is sought. For NSOs, the full range of outcomes will include sport, financial, organisational and social indicators (Bayle & Robinson, Citation2007) but for elite sport, funding decisions in the early twenty-first century have been dependent on performance in major sport events (De Bosscher et al., Citation2019; Sam, Citation2012). The key outcomes for which sustained high performance is required have, therefore, been imposed, with financial resources tied to a narrow range of sporting achievements, at the expense of social indicators (Green, Citation2007). There are sports for which the sustainability of the elite level has been threatened where UK Sport targets have not been met (Bostock et al., Citation2018).

The range of activities for what (“operations” in ) will be determined by the division of responsibilities between organisations for each sport and the decisions made on where and who. As referred to above, in the UK, elite-level NGBs receive funding from UK Sport to support individual athletes, teams and programmes, and to manage and participate in international sport events. Amongst the NGBs operations, it may be just specific activities which are affected by a major stressor, such as a prestigious event cancelled due to a natural disaster (Miles & Shipway, Citation2020), or it could be that a major stressor leaves the NGB to decide where the cuts are to be made amongst its different activities. Major UK Sport funding cuts require the NGB to consider the relationships between inputs (how), operations (what) and outcomes (why, for whom) in order to determine their priorities (Bostock et al., Citation2020).

To what is concerned with the type of influences and stressors involved. In their critique of resilience in research on regional economies, Martin and Sunley (Citation2015) reviewed the debate as to whether resilience to what should only cover sudden and unexpected events or also gradual changes. They concluded that resilience is mainly concerned with sudden shocks, but that gradual changes can reach a “tipping point” beyond which they become a disruptive shock. An example of this amongst UK NGBs is GB Badminton, who saw a steady decline in UK Sport funding after the 2005-2009 funding cycle, and then experienced a tipping point when they lost their UK Sport funding after Rio 2016 (Ingle, Citation2017).

incorporates the “slow burn” pressures referred to by Martin and Sunley (Citation2015). The term “influences/stressors” is used because it is not always easy to categorise all the external factors influencing an organisation or organisational system into opportunities with benign or positive implications and threats which will cause stress. For example, British Cycling recently received a 17% increase to their funding allocation between Tokyo and Paris Games, making them the highest-funded UK NGB (UK Sport, Citation2020), which might lead to arguments as to how that funding is used, potentially acting as a stressor.

illustrates a situation where there is one major stressor, but a variety of other influences/stressors happening on a regular basis. Using the NGB funding example, a major stressor occurs when the four-year Olympic funding cycle allocation is made, while less significant financial decisions and adjustments also occur at other times during the funding period (). Usually, these are minor stressors, but occasionally annual reviews can see entire funding streams removed, such as British Water Polo losing their £4.5 m funding one year into the cycle for the Rio Olympics (Gibson, Citation2014).

Related to the distinction between the resilience of a sports organisation and the resilience of the system of which they are a part, some stressors mainly affect NSOs as organisations, while others mainly affect the sport supported by the NSO. provides a list of common stressors and categorises them in terms of whether they are mainly linked to the playing of sport or to sport organisations, or both. Often these stressor categories are linked, for example, safety incidents leading to new legislation on equipment. Some stressors are isolated major events, such as the Hillsborough Disaster, while in other cases there may be regular small stressors with occasional major events, such as climate change effects on sport stadia (Dingle & Stewart, Citation2018).

Table 2. Types of stressors affecting sport organisations.

The variety of different types of stressor in illustrate the dangers of treating resilience as a general organisational attribute, as in some of the models summarised by Gibson and Tarrant (Citation2010). For example, the actions that might be required to prevent scandals affecting the sport are very different from those in anticipation of natural disasters. At the national level, broad-brush policies to build resilience through sport, for example, by concentrating resources on fewer elite sports, may have unintended consequences which increase, rather than reduce, vulnerability (Sam, Citation2015).

Examples from the sport management literature illustrate that the relationship between external stressors and internal resources is critical for the how of resilience, whether at the individual level (Bryan et al., Citation2019) or the organisational level (Filo et al., Citation2015; Wicker et al., Citation2013). When an organisational system is subjected to stressors, it will draw upon existing resources and make changes to those and other resources. For example, it might use financial reserves to employ additional temporary staff. Those internal changes to inputs will feed through to changes in operations. The how of resilience includes proactive actions before the stressor, and reactive actions to maintain functions after the stressor has occurred (Fletcher & Sarkar, Citation2016). Those internal changes will affect the outcomes for the organisational system. Success in achieving sustained high performance for key outcomes for organisational goals, despite the stressor(s) will demonstrate resilience, and will contribute to sustainability. However, the changes in the resource conversion process do not happen linearly, and changes are not all related to external influences/stressors. Instead, as shown in , a spiral is a more appropriate way to represent the complex inter-relationships and inter-actions between inputs, operations, and outcomes, which will include internal feedback mechanisms. The spiral reflects the complex inter-relationships in “dynamical systems” (Hill et al., Citation2018a).

The performance management literature in sport has identified factors which enhance performance and those which inhibit performance, which will link to the how of resilience (Bayle & Robinson, Citation2007; Kasale et al., Citation2018). Those factors include some which are concerned with the mix of resources, such as the balance of paid staff and volunteers, and others which are less tangible, such as the nature of the organisational culture (Bayle & Robinson, Citation2007). Since resilience is concerned with the actions taken in response to an external stressor, the factors which will enhance or inhibit resilience must be identified on a contingent basis.

There may be efforts from within the organisational system to influence the external environment, and external effects arising from internal outcomes. For example, in the UK, NGBs have lobbied at times for changes to the “No Compromise” system of funding for elite sport (Bostock et al., Citation2020). Also, the future of that funding system is affected by its overall success, as measured through the medal tables at major championships. Therefore, refers to feedback loops affecting future stressors.

The how of resilience is bound up with when, given the temporal nature of definitions of resilience. Guidance for organisations has been developed for both prior planning for disturbances and adaptive capacity to respond to the unexpected (Fletcher & Sarkar, Citation2016; Lee et al., Citation2013). As all actions have resource implications, choices must be made on the balance between investments in prior planning and adaptive capacity.

Continuity and change in organisations are often viewed as alternatives, but they can also be conceptualised as mutually co-evolving, as two aspects of a single process (Malhotra & Hinings, Citation2015), which could be appropriate in addressing how to build resilience. For example, continuity in some elements of an organisation, such as the competences vested in core employees, is required to enable the organisation to be agile and adaptable in unstable environments (Lengnick-Hall et al., Citation2011). The target-driven, top-down stream of policies imposed by both UK Sport (Bostock et al., Citation2018) and Sport England (Thompson et al., Citation2021) have meant that NGBs have engaged in tactical changes in order to achieve those targets, in which the skills and experience of staff in the bureaucracy of performance management become central to both the fortunes of the NGB itself and funding for the sport.

In the face of uncertainty in future funding, one of the critical decisions for UK NGBs is how they profile the funding they receive, over a four-year period (when and how in ). As represented in the FfORM (see ), the funding profile will determine the level and type of resources deployed, in turn leading to the level and range of activities delivered over time, which will result in a variety of outcomes. To increase the chances of achieving targets for the Olympic games at the end of the funding period, NGBs are likely to front-load funding to support the elite athletes whose development might enable them to achieve a medal. This is, however, a risky strategy if the hoped-for results do not materialise since it will leave few resources for the final months of the funding period. Bostock et al. (Citation2020) found that three NGBs which received large cuts in funding between the 2009 and 2013 and 2013 and 2017 cycles were in a perilous financial situation at the end of 2012/beginning of 2013 because of front-loading, and, as a result, had to make severe and immediate cutbacks. Prior planning (Lee et al., Citation2013) for the potential major stressor of a funding cut would suggest back-loading of funding.

In some sporting contexts there can be a trade-off between sporting success and financial success (Wicker & Breuer, Citation2014; Winand et al., Citation2010), but the “No Compromise” funding principle has led to financial allocations being directly reliant on previous sporting success demonstrated through achieving medals (Bostock et al., Citation2018). As NGBs have limited control over podium places at the Olympic/Paralympic Games, due to injury, underperformance or an athlete exceeding expectations, key outcomes are difficult to predict. Therefore, there are no easy answers in balancing conflicting pressures in deciding how to profile funding over the four-year period.

The potential major stressor of the change in funding becomes real at the point when UK Sport announces the allocations to NGBs, usually in December, to take effect from the following April. Signals of possible changes in policy are sometimes provided in advance but are not always acted on. Bostock et al. (Citation2020) found evidence of denial on the part of some NGBs in response to such signals, a common reaction to adverse changes (Carnall & By, Citation2014). The phenomenon of signals of a looming crisis becoming evident shortly before it happens, but possibly being ignored or downplayed, is one which is common in the analysis of resilience in other fields (Denyer & Pilbeam, Citation2016; Lee et al., Citation2013).

After the major stressor has occurred, the how of resilience depends on the level of disruption involved. The longer-term aim of NSOs faced with reductions in funding may be to turn around their fortunes to achieve podium places at major championships, but the level of cuts required may lock them into path dependency so that this becomes ever more unlikely. Bostock et al. (Citation2020) found that the changes that had to be made in three NGBs losing their funding in 2013 reduced activities to a minimum, even threatening their survival as organisations. The “post-major stressor adjustments” (see ) were therefore extreme cutbacks in these examples, which limited options later.

Analysis of NGB funding allocations (Supplemental File) identifies only one example demonstrating resilience, where a significant loss of UK Sport funding has been followed by a subsequent sustained upturn (prior to the change in funding methodology implemented for the Paris funding cycle) because Olympic Games targets have been met or exceeded despite the reduction in funding. This was British Shooting, for whom a reduction of 51% after Beijing, where they did not achieve their target, was followed by successive increases of 60% after London and 76% after Rio. However, the margins between success and failure were finely balanced, sometimes hinging on a single shot, with success at Rio being achieved through two bronze medals (Olympics, Citationn.d.).

The announcements of funding for the 2021–2025 cycle include a new “three-tier” system – a World Class Programme for those sports competing for Olympic Games, a smaller Progression fund based around a 12-year cycle of development, and the National Squads Support Fund which will help sports at the initial development stage (UK Sport, Citation2020; UK Sport, Citation2021). This alters the policy context for NGB decision-making, but the underlying dilemmas and trade-offs around issues such as funding profiles remain.

4. Conclusions and further research

The article addresses a gap in the sport management literature on resilience in being focused at the organisational level. It builds on key themes in the individual/team sport resilience literature in taking a temporal, dynamic approach and linking resilience to performance management. The FfORM avoids reifying resilience and making unwarranted normative assumptions. Instead, resilience is treated as a means to an end to achieve priority outcomes, which are determined outside the FfORM. This facilitates explicit consideration of trade-offs in any actions to seek to become resilient.

The funding cycle for NGBs illustrates the dilemmas associated with trade-offs, through the example of profiling of funds over the four-year period. Such dilemmas are not addressed in diagnostic tools on resilience as a general organisational attribute. For example, “Our organisation maintains sufficient people and resources to cope with unexpected change”, is one of the statements in a well-known tool, the OrgRes Diagnostic (Resilient Organisations, Citationn. d.). Such an approach implies a back-ended profile in the funding cycle for elite sport, but this could prejudice the ability to achieve key outcomes, critical to future funding from UK Sport.

The FfORM requires explicit consideration of scoping issues, in particular, the boundaries of the organisational system. The complex organisational relationships in sport management and the variety of stakeholders mean that this gives the analysis of resilience a transparency which might not occur when resilience is treated as a general organisational attribute.

The FfORM has been used in this article as a post hoc evaluation tool, using secondary sources to assess the resilience of UK NGBs to changes in funding for elite sport. The FfORM has been shown to be useful for reinterpreting existing research findings with a resilience lens and identifying future research priorities, for example, into the profiling of funding by NSOs, and the implications for activities and outcomes. Secondary data suggests where detailed case study research would be useful, for example, into the story behind the resilience of British Shooting. The sport management research applications of the FfORM are not limited to elite Olympic sport NGBs, but also to other sport themes, such as sport participation and disability sport. The FfORM could be applied to community-level sport organisations, adjusting the scale of the organisational system boundaries and hence the nature of the external stressors/influences.

The FfORM could also be used as a management tool by sports organisations. The FfORM enables key activities to be linked together, such as scanning the macro-environment for potential stressors and evaluating their significance, recognising trade-offs and stakeholder interests in the allocation of resources and aligning resource use to the achievement of key outcomes. This enables the benefits and disbenefits of different strategies for resilience to be addressed holistically. It provides a way of contextualising organisational attributes found in tools for assessing resilience, such as the OrgRes Diagnostic (OrgRes Dianostics, Citation2021). For example, the attribute “our employees have a clear understanding of organisational priorities in a crisis” relies on key outcomes having been identified first. Many of the other statements in the OrgRes Diagnostic depend on how the organisational system is defined, such as “if key people are unavailable, there are always others who can fill their role”. In sport, the large number of relatively small organisations and the mix of professional staff and volunteers makes the boundaries of the organisational system critical for addressing such issues.

For the development of theory, propositions can be formulated for testing relationships between the different FfORM components for sports organisations, worded precisely to reflect the complexities discussed in this article. For example, it is crucial to draw the distinction between the resilience of the organisation itself and the resilience of the activities provided to sports participants. Examples of such propositions, which could be used together in system modelling based on the FfORM, are:

Sports organisations which prioritise outcomes before making changes in their operations will be resilient in maintaining/enhancing performance indicators for those outcomes (why, for whom and what)

Sports organisations which work collaboratively in networks of sports organisations will be resilient in maintaining/enhancing performance indicators for target beneficiaries (Where, who, why and for whom)

Sports organisations with the capacity to substitute resources (for example, through financial reserves, selling assets, capacity to increase reliance on volunteers rather than paid staff) will be resilient in maintaining/enhancing their operations (How and what)

Sports organisations which monitor potential major stressors and try to be proactive in planning for them will be resilient in maintaining/enhancing their resource base (When, to what and how).

All previous major stressors for sport management are dwarfed by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, which affects every aspect of sporting activity at both elite and grassroots levels and will challenge the resilience of sport organisations globally (Parnell et al., Citation2020). The pandemic can be incorporated into the FfORM as a “mega-stressor”, with a variety of different effects on the organisational system. In the short term, the cancellation of events and restrictions on sporting activities has led to underutilised resources and losses in income for most sports (Miles & Shipway, Citation2020). The postponement of the Tokyo Olympics/Paralympics to 2021 took funding for elite sport into “uncharted territory” (BBC, Citation2020). Funding profiles and key decision dates for future allocations will vary across sports and between nations; as indicated above, NGB allocations for 2021–2025 were announced by UK Sport in December, 2020. Using the FfORM, a timeline of future stressors can be mapped out, providing a basis for anticipatory actions. For example, sports might plan for adjustments to funding allocations following the Tokyo Games using different performance scenarios. However, the complex interplay of different types of stressor and the continuing uncertainties in the external environment and organisational relationships in sport limit the degree to which tools such as the FfORM can act as forecasting models.

The key argument in this article is that organisational resilience in sport needs to be theorised within a wider management framework. The article has had to be selective in the range of management issues linked to resilience which have been explored. By developing the linkages between the FfORM and the literature on change management, risk management and other themes, both in sport and in other fields, there is potential for further theoretical developments and practical applications.

Supplementary_Material

Download MS Word (39.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 This is the definition which underpins the British Standard (BS6500:2014) and International Standard (ISO22316: 2017) for Organisational Resilience.

References

- Barbieri, P., Ciabuschi, F., Fratocchi, L., & Vignoli, M. (2018). What do we know about manufacturing reshoring? Journal of Global Operations and Strategic Sourcing, 11(1), 79–122. https://doi.org/10.1108/jgoss-02-2017-0004

- Bayle, E., & Robinson, L. (2007). A framework for understanding the performance of national governing bodies of sport. European Sport Management Quarterly, 7(3), 249–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184740701511037

- BBC. (2020, March 25). Olympic and Paralympic sport funding into “uncharted territory” – Grainger. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/olympics/52036792

- Begović, M. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on society and sport a national response. Managing Sport and Leisure, 25(6), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1779115

- Berry, R., & Manoli, A. (2018). Alternative revenue streams for centrally funded sport governing bodies. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 10(3), 429–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2017.1387587

- Boin, A., Kofman, C., Kuilman, J., Kuipers, S., & van Witteloostuijn, A. (2017). Does organizational adaptation really matter? How mission change affects the survival of U.S. Federal independent agencies, 1933-2011. Governance, 30(4), 663–686. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12249

- Boin, A., & Van Eeten, M. (2013). The resilient organization. Public Management Review, 15(3), 429–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.769856

- Bostock, J., Breese, R., Ridley-Duff, R., & Crowther, P. (2020). Challenges for third sector organisations in cutback management: A sporting case study of the implications of publicness. Public Management Review, 22(2), 184–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1577911

- Bostock, J., Crowther, P., Ridley-Duff, R., & Breese, R. (2018). No plan B: The Achilles heel of high-performance sport management. European Sport Management Quarterly, 18(1), 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2017.1364553

- Bovaird, T., & Quirk, B. (2013). Risk and resilience. Chapter 5 In C. Staite (Ed.), Making sense of the future: can we develop a new model for public services? (pp. 1–6). Institute of Local Government Studies, University of Birmingham.

- Brand, F., & Jax, K. (2007). Focusing the meaning (s) of resilience: Resilience as a descriptive concept and a boundary object. Ecology and Society, 12(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.5751/es-02029-120123

- Bruneau, M., Chang, S., Eguchi, R., Lee, G., O’Rourke, T., Reinhorn, A., Shinozuka, M., Tierney, K., Wallace, W., & Von Winterfeldt, D. (2003). A framework to quantitatively assess and enhance the seismic resilience of communities. Earthquake Spectra, 19(4), 733–752. https://doi.org/10.1193/1.1623497

- Bryan, C., O’Shea, D., & MacIntyre, T. (2018). The what, how, where, and when of resilience as a dynamic, episodic, self-regulating system: A response to Hill et al. (2018). Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 7(4), 355–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000133

- Bryan, C., O’Shea, D., & MacIntyre, T. (2019). Stressing the relevance of resilience: A systematic review of resilience across the domains of sport and work. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 12(1), 70–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984x.2017.1381140

- Capon, C. (2009). Understanding the business environment (3rd ed). Routledge Pearson Education Limited. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780080915258

- Carnall, C., & By, R. T. (2014). Managing change in organizations (6th ed). Pearson Higher Education.

- Danermark, B., Ekstrom, M., Jakobsen, L., & Karlsson, J. (2002). Explaining society, critical realism in the social sciences, critical realism interventions. Routledge.

- De Bosscher, V., Shibli, S., & Weber, A. (2019). Is prioritisation of funding in elite sport effective? An analysis of the investment strategies in 16 countries. European Sport Management Quarterly, 19(2), 221–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2018.1505926

- Denyer, D. (2017). Organizational resilience: A summary of academic evidence, business insights and new thinking. BSI and Cranfield School of Management. https://www.bsigroup.com/LocalFiles/EN-HK/Organisation-Resilience/Organizational-Resilience-Cranfield-Research-Report.pdf

- Denyer, D., & Pilbeam, C. (2016). Managing change in extreme contexts. Routledge.

- Department of Transport, Tourism and Sport for Ireland. (2020, June 19). Ministers announce COVID-19 funding support for the sport sector [Press release]. https://www.gov.ie/en/press-release/1da81-ministers-announce-covid-19-funding-support-for-the-sport-sector/

- Dingle, G., & Stewart, B. (2018). Playing the climate game: Climate change impacts, resilience, and adaptation in the climate-dependent sport sector. Managing Sport and Leisure, 23(4–6), 293–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2018.1527715

- Duit, A. (2016). Resilience thinking: Lessons for public administration. Public Administration, 94(2), 364–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12182

- Feddersen, N., Morris, R., Abrahamsen, F., Littlewood, M., & Richardson, D. (2020). The influence of macrocultural change on national governing bodies in British Olympic sports. Sport in Society, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2020.1771306

- Filo, K., Cuskelly, G., & Wicker, P. (2015). Resource utilisation and power relations of community sport clubs in the aftermath of natural disasters. Sport Management Review, 18(4), 555–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2015.01.002

- Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2016). Mental fortitude training: An evidence-based approach to developing psychological resilience for sustained success. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 7(3), 135–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2016.1255496

- Fletcher, D., & Wagstaff, C. (2009). Organizational psychology in elite sport: Its emergence, application and future. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 10(4), 427–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2009.03.009

- Galli, N., & Gonzalez, S. (2015). Psychological resilience in sport: A review of the literature and implications for research and practice. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13(3), 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197x.2014.946947

- Giannoulakis, C., Papadimitriou, D., Alexandris, K., & Brgoch, S. (2017). Impact of austerity measures on national sport federations: Evidence from Greece. European Sport Management Quarterly, 17(1), 75–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2016.1178795

- Gibson, O. (2014, March 19). “This is a very dark day for sport” – funding appeals rejected by UK Sport. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2014/mar/19/uk-sport-olympic-funding-basketball-funding

- Gibson, C., & Tarrant, M. (2010). A conceptual models’ approach to organisation resilience. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 25(2), 6–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2011.563826

- Green, M. (2007). Olympic glory or grassroots development? Sport policy priorities in Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom, 1960–2006. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 24(7), 921–953. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523360701311810

- Grix, J., Brannagan, P., Wood, H., & Wynne, C. (2017). State strategies for leveraging sports mega-events: Unpacking the concept of “legacy”. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 9(2), 203–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2017.1316761

- Hammond, A. (2020). Financing sport post-COVID-19: Using Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) to help make a case for economic recovery through spending on sport and recreation. Managing Sport and Leisure, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1850326

- Hassler, U., & Kohler, N. (2014). Resilience in the built environment. Building Research & Information, 42(2), 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2014.873593

- Hill, Y., Den Hartigh, R., Meijer, R., De Jonge, P., & Van Yperen, N. (2018a). Resilience in sports from a dynamical perspective. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 7(4), 333. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000118

- Hill, Y., Den Hartigh, R., Meijer, R., De Jonge, P., & Van Yperen, N. (2018b). Reply – The temporal process of resilience. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 7(4), 363–370. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000143

- Hillman, A., Withers, M., & Collins, B. (2009). Resource dependence theory: A review. Journal of Management, 35(6), 1404–1427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309343469

- Ingle, S. ((2017, February 20). GB Badminton “staggered” after UK Sport rejects seven Tokyo funding appeals. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2017/feb/20/gb-badminton-staggered-uk-sport-funding-olympic

- John, P. (2014). The great survivor: The persistence and resilience of English local government. Local Government Studies, 5(40), 687–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2014.891984

- Kasale, L., Winand, M., & Robinson, L. (2018). Performance management of national sports organisations: A holistic theoretical model. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 8(5), 469–491. https://doi.org/10.1108/sbm-10-2017-0056

- Kiefer, A., Silva, P., Harrison, H., & Araújo, D. (2018). Antifragility in sport: Leveraging adversity to enhance performance. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 7(4), 342–350. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000130

- Lebel, L., Anderies, J., Campbell, B., Folke, C., Hatfield-Dodds, S., Hughes, T., & Wilson, J. (2006). Governance and the capacity to manage resilience in regional socialecological systems. Ecology and Society, 11(1), Article 19, https://doi.org/10.5751/es-01606-110119

- Lee, A., Vargo, J., & Seville, E. (2013). Developing a tool to measure and compare organizations’ resilience. Natural Hazards Review, 14(1), 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)nh.1527-6996.0000075

- Lengnick-Hall, C., Beck, T., & Lengnick-Hall, M. (2011). Developing a capacity for organizational resilience through strategic human resource management. Human Resource Management Review, 21(3), 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2010.07.001

- Linnenluecke, M. (2017). Resilience in business and management research: A review of influential publications and a research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 19(1), 4–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12076

- Malhotra, N., & Hinings, C. (2015). Unpacking continuity and change as a process of organizational transformation. Long Range Planning, 48(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.08.012

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2015). On the notion of regional economic resilience: Conceptualization and explanation. Journal of Economic Geography, 15(1), 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbu015

- Miles, L., & Shipway, R. (2020). Exploring the COVID-19 pandemic as a catalyst for stimulating future research agendas for managing crises and disasters at international sport events. Event Management, 24(4), 537–552. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599519X15506259856688

- Molan, C., Kelly, S., Arnold, R., & Matthews, J. (2019). Performance management: A systematic review of processes in elite sport and other performance domains. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 31(1), 87–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1440659

- Nicholson, J., LaPlaca, P., Al-Abdin, A., Breese, R., & Khan, Z. (2018). What do introduction sections tell us about the intent of scholarly work: A contribution on contributions. Industrial Marketing Management, 73, 206–219. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2018.02.014

- O’Boyle, I., & Hassan, D. (2014). Performance management and measurement in national-level non-profit sport organisations. European Sport Management Quarterly, 14(3), 299–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2014.898677

- Olympics. (n.d.). Shooting. Olympics.org. https://www.olympic.org/rio-2016/shooting

- OrgRes Dianostics. (2021). Resilient organisations. https://orgrestool.resorgs.org.nz/

- Orr, M., & Kellison, T. (2020). Sport facilities as sites of environmental and social resilience. Managing Sport and Leisure, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1855081

- Parent, M. M., Naraine, M. L., & Hoye, R. (2018). A new era for governance structures and processes in Canadian national sport organizations. Journal of Sport Management, 32(6), 555–566. doi:10.1123/jsm.2018-0037

- Parnell, D., May, A., Widdop, P., Cope, E., & Bailey, R. (2019). Management strategies of non-profit community sport facilities in an era of austerity. European Sport Management Quarterly, 19(3), 312–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2018.1523944

- Parnell, D., Widdop, P., Bond, A., & Wilson, R. (2020). COVID-19, networks and sport. Managing Sport and Leisure, 1–7. http://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1750100

- Pedras, L., Taylor, T., & Frawley, S. (2020). Responses to multi-level institutional complexity in a national sport federation. Sport Management Review, 23(3), 482–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2019.05.001

- Porter, M. (1985). Competitive advantage; creating and sustaining superior performance. Free Press.

- Resilient Organisations. (n. d.). OrgRes Diagnostic - The OrgRes Tool. http://orgrestool.resorgs.org.nz/orgres-tool/

- Sam, M. (2012). Targeted investments in elite sport funding: Wiser, more innovative and strategic? Managing Leisure, 17(2-3), 207–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/13606719.2012.674395

- Sam, M. (2015). Sport policy and transformation in small states: New Zealand’s struggle between vulnerability and resilience. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 7(3), 407–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2015.1060715

- Shipway, R. (2018). Building resilience and managing crises and disasters in sport tourism. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 22(3), 265–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775085.2018.1498152

- Sport New Zealand. (2020, July 8). Sport New Zealand Sector update [Press release]. https://us6.campaign-archive.com/?u=ef741df6f3215cebd8c693760&id=157ea79611

- Strunz, S. (2012). Is conceptual vagueness an asset? Arguments from philosophy of science applied to the concept of resilience. Ecological Economics, 76, 112–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.02.012

- Taleb, N. N. (2012). Antifragile: How to live in a world we don’t understand. Allen Lane.

- Thompson, A., Bloyce, D., & Mackintosh, C. (2021). “It is always going to change” – examining the experiences of managing top-down changes by sport development officers working in national governing bodies of sport in England. Managing Sport and Leisure, 26(1–2), 60–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1800507

- UK Sport. (2020, December 18). UK Sport outlines plans for £352million investment in Olympic and Paralympic sport. https://www.uksport.gov.uk/news/2020/12/18/paris-cycle-investment

- UK Sport. (2021, March 30). UK Sport to invest £2.4m in eight further sports as part of National Squads Support Fund. https://www.uksport.gov.uk/news/2021/03/29/national-squads-support-fund

- Valikangas, L. (2010). The resilient organization: How adaptive cultures thrive even when strategy fails. McGraw-Hill.

- Virtanen, T. (2013). Context in the context – missing the missing links in the field of public administration. In C. Pollitt (Ed.), Context in public policy and management (pp. 3–21). Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781781955147.00008

- Warner, E. (2020, 15 October). National governing bodies must develop “independent resilience” and try not to rely on state support. iSportConnect. https://gbwr.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/National-Governing-Bodies-Must-Develop-%E2%80%98Independent-Resilience%E2%80%99-And-Try-Not-To-Rely-On-State-Support-%E2%80%93-iSPORTCONNECT.pdf

- Whetten, D. A. (1989). What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 490–495. http://doi.org/10.2307/258554

- White, I., & O’Hare, P. (2014). From rhetoric to reality: Which resilience, why resilience, and whose resilience in spatial planning? Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 32(5), 934–950. https://doi.org/10.1068/c12117

- Wicker, P., & Breuer, C. (2014). Examining the financial condition of sport governing bodies: The effects of revenue diversification and organizational success factors. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 25(4), 929–948. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-013-9387-0

- Wicker, P., Filo, K., & Cuskelly, G. (2013). Organizational resilience of community sport clubs impacted by natural disasters. Journal of Sport Management, 27(6), 510–525. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.27.6.510

- Wildavsky, A. (1988). Searching for safety. Transaction Books.

- Winand, M., Zintz, T., Bayle, E., & Robinson, L. (2010). Organizational performance of Olympic sport governing bodies: Dealing with measurement and priorities. Managing Leisure, 15(4), 279–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-013-9387-0