ABSTRACT

Rationale

Drawing on a conceptual lens informed by ableism and Importance Performance Analysis (IPA), the purpose of this paper is to discover how managers within European National Football Associations (NAs) develop disability football.

Design

This novel study explores the development of disability football from the perspective of 37 European National Football Association (NAs) managers. Results were based on a pan-European questionnaire that assessed managerial viewpoints that subsequently identified the priorities across the region.

Findings

Findings indicate that much resource has been dedicated to developing disability football, in some cases suggesting over-allocation of finance, facilities and human resources. Efforts to enhance levels of disability awareness and the competencies that underpin the development of disability football are needed.

Practical implications

Managers need to invest in developing competence through the formation of inter-organizational partnerships with disability sports organizations.

Research contribution

This paper provides a novel and pragmatic review of the priorities for disability football delivery in Europe. The results provide diagnostic support for quality enhancement.

Introduction

In recent decades, many football (soccer) associations, leagues, and clubs across Europe have begun to implement “Football for All” for people with a disability (PwD) (Atherton & Macbeth, Citation2017). Disability football includes programmes for a range of disability types; football for the blind (B1) or partially sighted (B2 and B3), Deaf football, for people with specific types of physical disability powerchair, frame or cerebral palsy football are offered, and football for people with an intellectual disability. In this paper, we use the term disability football to represent one or more of these types. As this is an emerging field of practice, the development of disability football and the specific programmes offered varies across this region. For example, since March 2008 the Sepp–Herberger-Foundation, the German Disabled Sports Association and the German Association for the Blind and Visually Impaired have been operating a national (German) blind football league, where some teams are also affiliated to the top four (Hertha BSC (Berlin), FC St. Pauli, Schalke 04 and BVB Dortmund) Bundesliga (mainstreamFootnote1) professional clubs (www.blinden-fussball.de). More recently, the Spanish LaLiga Genuine Santander for young players with intellectual disabilities was officially launched in the 2017–2018 season. This is a national football tournament that brings together nearly all the 36 professional clubs of LaLiga 1 and 2 (LaLiga.com, Citation2020). Nevertheless, in other European nations links between mainstream professional football leagues and clubs and their disability football counterparts are at a more embryonic stage and there is a lower level of vertical integration (Atherton & Macbeth, Citation2017).

Football is just one sport that has received attention within a broader academic focus on disability and sport. Darcy et al. (Citation2017) highlight that this literature base is dominated by medical and rehabilitation focused research (Damen et al., Citation2020; Jouira et al., Citation2021), psychological studies (McLoughlin et al., Citation2017; Townsend et al., Citation2020a), and an increase in research into sport and physical activity for PwD as a mechanism to achieve personal (Blauwet, Citation2019; Robertson et al., Citation2018) and societal benefits (Blauwet, Citation2019; Kasum, Citation2019). Despite a growth in disability sport management literature that addresses a range of contexts over the past decade (Cunningham & Warner, Citation2019; Legg et al., Citation2009; Misener & Darcy, Citation2014; Patatas et al., Citation2020; Shapiro & Pitts, Citation2014; Wicker & Breuer, Citation2014), the development of structures and organization of disability football, one subset of the literature has so far lacked wider, pan-regional analysis.

Before outlining our aims and objectives, it is important to define what is understood by disability in the context of this paper and the model followed in our analysis. Disability is defined by the World Health Organization as an “umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions, referring to the negative aspects of the interaction between an individual (with a health condition) and that individual’s contextual factors (environmental and personal factors)” (WHO, Citation2011, p. 4). This definition attempts to reconcile the major models of understanding disability, the medical and the social. We adhere to the social model principles enshrined in the 2006 United Nations Convention for the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPwD). The CRPwD is based on the social model conceptualizations of disability and reinforces disability discrimination policies and legislation in many member countries. The social model posits that there are societal practices that transform an individual’s impairment into a socially constructed disability. At the time of writing, 182 nations out of the 193 member states of the United Nations have signed this global convention; however, disability discrimination legislation can vary within regions, for example, Europe. The CRPwD explains in detail the rights of PwD and sets out suggestions for its implementation through legislation, policy, and administrative measures. Among other contributions, this global convention details the rights of PwD, recognises the historical demand for equal opportunities and treatment for PwD and their companions to enjoy all services of society as offered by sport, while at the same time, prohibits all forms, both direct and/or indirect, of discrimination against them (United Nations, Citation2006). Article 30.5 of the United Nation’s CRPwD enshrines the rights of citizens' access to take part in a cultural life “on an equal basis with others” (UN, Citation2006, online). Participation in cultural activities such as recreation, leisure, the arts, tourism, and sport enrich lives and provides multiple avenues for an individual’s choice and freedom of expression (UN, Citation2006). It is this commitment to the social model, particularly in our own role as non-disabled researchers that social conceptualizations of rights, access and barriers inform our analysis as we explore the priorities of disability football development.

Research questions

Drawing on a conceptual lens combining ableism and Importance Performance Analysis (IPA), the purpose of this paper is to discover how European National Football Associations' (NAs) managers develop disability football. An NA manager is a staff member (either full-, part-time or voluntary) that responsible for planning, organizing, controlling, and leading a national disability football section. Allied to this purpose, our aim is to explore areas of priority and to explicitly analyse the implications of these determinations in our conceptual frame. Once identified, we examined in more detail the assumptions held by those managing disability football within Europe. To achieve this purpose, we sought to address the following research questions:

Research Question 1. Where are the NAs priorities for increasing the inclusion of PwD within European football?

Research Question 2. Where are the NAs priorities for developing disability football?

Research Question 3. What resources and competencies are prioritized to underpin these developments?

Research Question 4. What are the implications of these priorities for the European National Football Associations’ management of disability football?

Literature review

Developing disability football

Tracing the history of disability football, as Atherton and Macbeth (Citation2017) argued, is a significant challenge due to the considerable diversity within the broad label of “disability football”, its low academic and public profile and extremely limited documentation of early developments. One of the earliest documented examples is the organization of a football club for the Deaf in the nineteenth-century Scotland (Atherton et al., Citation1999; Atherton et al., Citation2001) and subsequent major tournaments like the International Silent Games (now the Deaflympics) in 1924 (Atherton & Macbeth, Citation2017; Brittain, Citation2010). However, this historical account of football for a particular impairment group such as Deaf people is the exception rather than the norm. As Brittain (Citation2010, p. 7) stated “there is little evidence of organized efforts to develop or promote sport for individuals with disabling conditions” prior to World War II due to the general belief that “people with physical disabilities should not be involved in competitive sport” (Polley, Citation2011, p. 166). Parallel to the gradual broadening of disability sport in the 1970s, incorporating more people with different disabilities and increasing the range of sports available, inaugural world disability football tournaments only began to emerge in the 1980s after international and national football authorities started to be interested in their development. According to Atherton and Macbeth (Citation2017), until this moment in time “disability football and disability footballers were at best marginalized and at worst totally ignored by national and international football authorities” (p. 280). These examples demonstrate how disability football competitions have evolved and grown, including cerebral palsy (CP) football in 1978 (IFCPF, Citationn.d.), amputee football in 1984 (World Amputee Football Federation, Citationn.d.), and more than a decade later, blind football (under IBSA – International Blind Sports Federation) in 1998 (IBSA, Citation2020a). Despite brief summaries of the development of football for particular impairment groups within specific nations (Frere, Citation2007; Kijanskiy, Citation2008; Macbeth, Citation2009; Macbeth & Magee, Citation2006; see also Atherton & Macbeth, Citation2017 for an in-depth analysis) detailed histories of football played by these groups, other than people with hearing impairments, have yet to materialize.

Although this body of work is expansive, the preponderance of research on contemporary aspects of disability football has been dominated by a focus on the experiences of players with a range of impairments: deaf people (Atherton et al., Citation2001); adults and girls with intellectual disabilities (Stride & Fitzgerald, Citation2011); partially sighted footballers (Macbeth, Citation2008, Citation2009; Macbeth & Magee, Citation2006; Powis & Macbeth, Citation2020); powerchair footballers (Cottingham et al., Citation2018; Jeffress & Brown, Citation2017; Richard et al., Citation2017) and amputees (van der Niet, Citation2010). Generally speaking, academic research of disability football has covered a range of themes including the social, psychological and health benefits of football; socialization experiences; inclusion and equality issues; empowerment; gender construction; and identity work.

However, there is emerging literature regarding the organization of disability sport focusing on the process of vertical integration, or mainstreaming (e.g. Christiaens & Brittain, Citation2021; Hammond & Jeanes, Citation2018; Howe, Citation2007; Hums et al., Citation2003; Kitchin & Howe, Citation2014; Thomas & Guett, Citation2014; Wicker & Breuer, Citation2014). Mainstreaming is defined as “the process of integrating the delivery and organization of all organized sporting opportunities to ensure a more coordinated and inclusive sporting system” (Kitchin & Howe, Citation2014, p. 66). Research from a management perspective has, so far, centred on the development of inclusive (or not) experiences for disabled fans at stadia of the main European football league clubs (Garcia et al., Citation2017; García & Welford, Citation2015; Paramio-Salcines et al., Citation2016; Paramio-Salcines & Kitchin, Citation2013). The exception is Kitchin and Crossin’s (Citation2018) study exploring how mainstream football clubs went about the process of merging and/or incorporating disability football clubs at the grassroots. From their analysis, clubs who could achieve integrative capacity tended to be larger and have well-established brands.

This process of mainstreaming has led to mainstream football clubs having to take some responsibility for the development of disability football and work with Disability Sport Organizations (DSO) to increase opportunities for disabled footballers at both grassroots and elite levels. Along with attempts to rationalize this development, tensions have arisen from conflict between the priority for participation versus performance. In partially sighted football, Macbeth (Citation2009) found that the prioritization of performance logics as the NAs became more involved brought about several changes to the rules and organization of the game, which contravened aspects of inclusion. Research has further revealed barriers to participation (Macbeth, Citation2009), changes to national talent development plans (Macbeth, Citation2009), the fast-tracking of promising talent (Macbeth & Magee, Citation2006) and problems with classification (Powis & Macbeth, Citation2020). Some of these issues exist, despite the process of mainstreaming. Others, however, have arguably been a result of it. Either way, they represent issues that both NAs and DSOs need to carefully negotiate to ensure that the empowering potential of disability football is not threatened (Atherton et al., Citation2001).

Whilst this body of literature provides insights into challenges within the development of disability football, it has focused on particular impairment groups within specific nations and largely from players’ perspectives. What is lacking, as this study proposes, is a pan-European analysis of disability football developments from the perspective of the NAs who are increasingly becoming the dominant service providers. In any case, in order to contribute to wider discussions about the development of disability sport, the conceptual framework below has been employed in our approach.

Conceptual tools from disability studies and performance management: Ableism and IPA

Disability football is a socially constructed practice. In order to provide analysis beyond description, we sought to undertake an assessment of performance management that was informed by a disability studies perspective. Our first key concept is Ableism which is “the ideology of ability, constitut[ing] a form of cultural imperialism” (Silva & Howe, Citation2019, p. 3) that creates and maintains attitudes, systems and procedures facilitated by individuals and organizations to foster actions that favour non-disabled people. Brittain et al. (Citation2020) suggest that ableism can frame “both the impact of the environment and societal attitudes as forms of social oppression that can lead to barriers to participation” (p. 210). This is particularly applicable to organizational analysis as Brittain et al. go further to indicate that ableism acts as a regulatory mechanism that values everything by normative ideas and in doing so reinforces inequitable power relations. An example of this was revealed by Howe (Citation2007) when a mainstream sports organization was reluctant to integrate their para-sport partner because of fears of diluting their funding pot – this fear being a manifestation of negative attitudes towards PwD. Recent work by Christiaens and Brittain (Citation2021) suggested that voluntary sports clubs believed they were being inclusive by incorporating opportunities for the participation of PwD, but the authors demonstrated the subtleties of ableism in revealing that participation alone does not amount to inclusion. Questions have been raised over whether the sector is run by PwD or for PwD – the consequence of the latter implies that PwD can be service users only, relegating them to positions of moderate or little power (Kappelides & Spoor, Citation2019). This further marginalizes PwD from view and negates the ability for cultures of disability to potentially inform the wider, normative-dominant cultures that inhabit many of our institutions (Goodley, Citation2014). The concept of ableism aligns with our social model, UN CRPWD informed approach in that devalues PwD and leads to “segregation, social isolation, and social policies […] that can limit opportunities for full societal participation” (Brittain et al., Citation2020, p. 212).

As Christiaens and Brittain (Citation2021) have shown, ableism is a useful lens by which to examine the priority of normalcy in sport management settings, and it can also generate management recommendations; however, our focus was pan-European in scope, and as such, we sought a performance management system that could allow managers in different countries, speaking multiple languages to identify how they could manipulate their resource mix to provide better services. To this end, we selected Importance-Performance Analysis (IPA) because of its ease data interpretation by managers and its potential to provide “an effective and efficient method” for collecting managerial viewpoints (Tarrant & Smith, Citation2002, p. 70). There are two limitations of the IPA approach that urge readers to use any findings with relative caution. The first limitation concerns the placement of the grid lines that determine the quadrants using the scale-centred approach (Azzopardi & Nash, Citation2013). To ensure the most accurate position a solution is to use the data-centred approach using the mean scores of both the importance and performance scores to place the crosshairs (Rial et al., Citation2008). The second limitation is the definition of importance and its impact on validity (Azzopardi & Nash, Citation2013; Eskildsen & Kristensen, Citation2006). Additionally, Bottomley et al. (Citation2000) recommended that Likert-style scales are superior when designing the data collection tools. Further discussion of how we accounted for these limitations is included in the method and results in sections below.

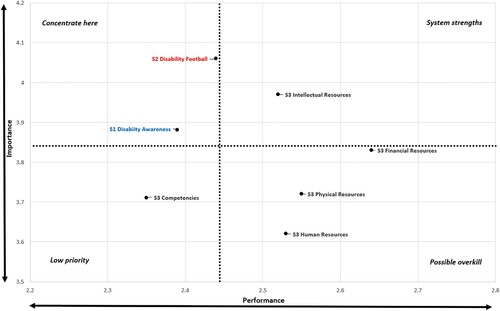

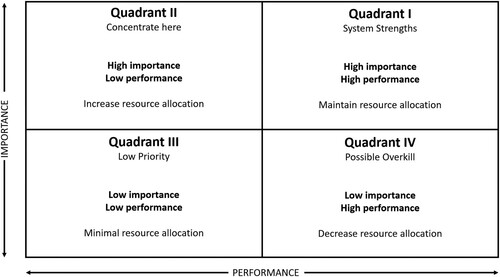

IPA charts a service providers’ perceived importance and performance of any given performance indicator and does so in a relational context between other priorities (Levenburg & Magal, Citation2004). In this paper, the traditional use of IPA analysis is designed to measure a manager’s perspective on both the importance of indicators that explore the development of disability football in mainstream organizations located across the UEFA region and then gauge their opinion on their organizations’ performance against those criteria. By considering both the importance and performance a manager attaches to an attribute, these indicators can be mapped on an IPA chart resulting in one of four possibilities (see ).

Figure 1. An Importance Performance Chart. Source: Adapted from Martilla and James (Citation1977).

When both importance and performance scores are high, the attribute is included in Quadrant I and is deemed a “system strength” and resources in this area should be sustained (Azzopardi & Nash, Citation2013; Griffin & Edwards, Citation2012; Martilla & James, Citation1977). When the importance of an attribute is high and the performance is low, the attribute is classified in Quadrant II as “concentrate here” suggesting that more resources are required. Quadrant III is deemed “low priority” and occurs when an attribute is rated low on both importance and performance, suggesting that no change in resources should occur. Finally, when importance is low and performance is high the attribute falls into Quadrant IV, “overkill” which suggests that resources could be curtailed and allocated to other areas.

The IPA framework has important practical implications for managers because as a diagnostic device, it allows managers to see where their strengths lie, to focus attention on specific areas of priority, to reduce resource allocation in areas of overkill and to critique and reflect upon areas deemed low priority (Rial et al., Citation2008; Tarrant & Smith, Citation2002). By combining IPA with ableism, we wish to explore how these mainstream organizations, originally set up to develop football opportunities for the non-disabled majority, prioritize and perform when it comes to the development of disability football. This conceptual lens will enable us to examine the extent to which ableism could be reinforced and/or challenged.

The context of the disability football industry in Europe

As the study was conducted on disability football in Europe, it is important to outline the context in which this takes place and the role of both mainstream football organizations and DSOs. In Europe, the governance and management of European football remain under the stewardship of the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA), which has 55-member countries (NAs). Under their auspices, much of disability football is delivered through inter-organizational partnerships between NAs, DSO and local grassroots organizations, although there is little understanding of how these partnerships operate, what the objectives are and what motivates the myriad partners. The involvement of NAs in mainstreaming disability football is a relatively recent occurrence (Atherton & Macbeth, Citation2017; Kitchin & Crossin, Citation2018; Macbeth, Citation2008). Prior to this, disability football was provided predominantly by DSOs, most of whom have an impairment-specific but multi-sport focus. Disability football has only just formed an organizing structure that promotes the interests of the sport world-wide. Launched on 3 December 2020, also the UN International Day of Persons with Disabilities, the Para Football Foundation represents the interests of eleven international DSOs, including IBSA, World Amputee Football Federation, Virtus – World Intellectual Impairment Sport, International Committee of Sports for the Deaf (ICSD) and other representative organizations, to develop football opportunities at both grassroots and elite levels for their respective impairment groups.

While only blind (5-a-side) football features at the Paralympic Games, the International Paralympic Committee exerts influence on disability football in ensuring the sport’s standards are acceptable to the wider Paralympic movement. This was seen recently with IPC-led alterations to blind football’s classification system (Runswick et al., Citation2021) and the exclusion of cerebral palsy football from the Paralympic Games sporting programme (Pavitt, Citation2019).

There are currently two football-specific DSOs operating internationally that focus on specific impairments. In 2006 the International Federation of Powerchair Football Association (FIPFA) was formed, with the European Powerchair Football Association (EPFA) representing the European region. As part of their mission, the FIPFA aims to develop opportunities and organize international competition for those with a “diagnosed, severe physical impairment that leads to a verifiable, permanent activity limitation, as a consequence, the athlete needs the use of powered mobility in order to play a sport” (FIPFA, Citation2017). More recently, the International Federation of CP Football (IFCPF) was created in January 2015 to develop CP football independently after 37 years under the umbrella of the “Cerebral Palsy Sport and Recreation Association” (CPISRA). Similarly, at European level, UEFA recommended the creation of a “disability football” unit in 2011. However, this is one of only two out of 15 recommendations from UEFA’s Football and Social Responsibility Strategy Review, that has not materialized (UEFA/Schwery Consulting, Citation2017). Instead, each of these international organizations oversee development and organize both world and regional football competitions for each impairment group. The only European-specific DSOs organizing pan-European leagues and cup competitions are the European Deaf Sports Organisation (EDSO) and the European Powerchair Football Association (EPFA). In partnership with UEFA, the IBSA Blind Football Development Project Europe began in 2012, with recent reports highlighting the support provided by IBSA to develop blind football in over 40 European nations (2019). As the only form of football in the Paralympic Games, blind football tends to receive more attention both nationally and internationally, with the first-ever Women’s World Championships announced for 2020 in Nigeria (IBSA, Citation2019); since postponed until 2021 due to the coronavirus pandemic (IBSA, Citation2020b).

This study illustrates that within each UEFA member nation, the practice of managing disability differs. However, while there is no uniform approach, each NA is in receipt of HatTrick funding which has grown from €1.66 million per NA in 2005 to €4.5 million per NA in 2020 (UEFA, Citationn.d.). These funds are earmarked for the development of football at both participation and performance levels through activities such as facility improvements, education programmes, elite and grassroots development programmes, and administrative costs. For example, in England, the game is governed by the FA, who, under the stewardship of a Disability Football Manager, manage seven elite disability England squads (The FA, Citationn.d.) and elements of grassroots disability football simultaneously. This grassroots commitment is maintained even with the significant financial resources that the FA possess.

Method

Participants

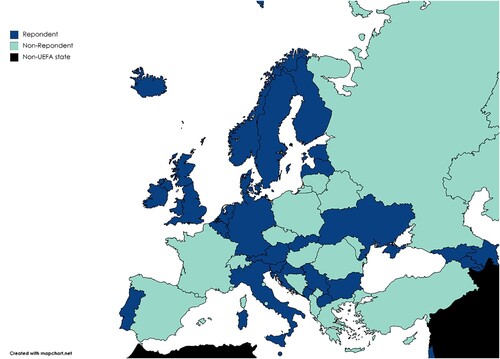

A survey was administered online by email, due primarily to issues of time, cost saving and access to a large and diverse sample (Andrew et al., Citation2011). Managers responsible for the development of disability football in the 55 NAs of UEFA were surveyed between November 2016 and April 2017. The inclusion criteria set was for managers with responsibility for development of disability football. When there was no such manager in place, then managers responsible for the development of football were included. In discussions with UEFA, the specification of the person responsible to complete this questionnaire was not prescribed and as such, names, gender, age, disability, and email addresses were not collected. While this could have added another layer to the analysis, our primary goal was to increase the sample size and it was felt by UEFA that this level of detail would reduce the response rate. Details were collected on job title, but as this was a non-compulsory field, only 22 respondents completed this question, some of these were generic titles such as consultant or project manager. We chose to survey the entire population, meaning that our sample was limited to those who responded. Out of 55 NAs, a total of 37 NAs managers completed the online survey, which represents an initial response rate of 67.2%. From this sample, 33 responses were deemed usable, reducing the overall response rate to 56%.Footnote2 shows a map of the total number (33) of NAs that completed the survey. According to Andrew et al. (Citation2011), the typical level of response rate for emailed questionnaires tends to range between 10% and 20% and, as such, our response rate was relatively strong.

Data collection

In order to ensure a pan-European reach, we chose a self-administered online survey design using IPA and followed the principles devised by Martilla and James (Citation1977) and in accordance with the approach used by sport and leisure management scholars (Rial et al., Citation2008; Tarrant & Smith, Citation2002; Zhang et al., Citation2011). The selection and testing of the questionnaire/online survey content involved four steps: defining the areas of interest (indicators), selecting a panel of experts, having those experts evaluate the questionnaire, and selecting the appropriate items for each indicator.

The initial questionnaire was designed by three members of the research team working iteratively from the literature review and in discussion with industry personnel, and by drawing on data from semi-structured interviews from previous publications (Kitchin & Crossin, Citation2018; Paramio-Salcines & Kitchin, Citation2013) resulting in 28 attributes covering the development of European disability football. The questionnaire was initially tested for face validity across a panel of six experts involved in disability football, disability rights and academia – some of whom had personal experience with disability. The panel of experts provided useful feedback on the final indicators and items to include in the survey, such as rewording for clarity, the exclusion of certain attributes and the inclusion of additional ones (as per Zhang et al., Citation2011).

The final survey consisted of 36 items covering the following seven indicators: (i) disability awareness, general issues in social responsibility in relation to disability football; (ii) disability football, containing items about its promotion, conduct and evaluation; and a series of resource indicators (iii) financial resources; (iv) physical resources; (v) intellectual resources, containing items specific to the branding of disability football; (vi) human resources; and (vii) competencies, items about how the various resources are implemented. The items first asked respondents to assess their perception of importance, anchored on a 5-point Likert-type scale (where 1 = definitely unimportant, 3 = neither not important nor important, and 5 = definitely important). The items then asked respondents to assess their perception of performance, anchored on a 5-point scale (where 1 = we could do better, 3 = satisfactory, and 5 = we excel). This survey design ensured we adhered to the Bottomley et al. (Citation2000) suggestion that Likert-type scales are superior to other techniques.

The questionnaire was divided into three sections to facilitate the interpretation and response process of the indicators. Section 1 consisted of four background questions, including name, job title, organization, and the history of the respondents’ involvement in the provision of disability football. Additionally, six IPA items focused on the disability awareness were included. Section 2 consisted of nine IPA items related to the disability football indicator. Section 3 presented 21 IPA indicators examining the resources and competencies indicators, including financial (2 IPA items), physical (3 IPA items), intellectual (4 IPA items), human (5 IPA items) resources and competencies (7 IPA items) that supported disability football. shows the sections and items of the questionnaire.

Table 1. The final survey indicators and items.

Due to the pan-European nature of the research, the survey was translated from English to three different languages (French, Spanish and German) to increase the accessibility across the European football industry. Back-translation performed by us, this was limited to NA name and job role, all of the IPA items consisted of quantitative data.

Data analysis

In the first step of the analysis, the internal reliability of particular indicators of the survey was tested for internal consistency through Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficients. Alpha values of 0.70 or higher were considered acceptable as a general guideline (Cronbach, Citation1951). In a second step of the analysis, the overall mean scores of importance and performance levels were calculated for each of the seven indicators under study. In step three, the differences between the perceived importance and the performance level of respondents were calculated for each indicator, using paired t-test for comparison purposes. The Bonferroni correction was applied to account for the multiple comparisons of the seven indicators under analysis, with a p value less than .0071 considered statistically significant (i.e. the original p value of .05 divided by seven tests being performed). Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d and their interpretation was based on the following criteria: 0.20 ≤ d < 0.20 small, 0.50 ≤ d < 0.80 medium, d ≥ 0.80 large (Cohen, Citation1988). Finally, in step four, the corresponding IPA grid was plotted to visually depict the respondents’ ratings for each indicator according to its means scores of importance and performance. The overall mean values of importance and performance were set as the reference values of the y-axis and x-axis, respectively. The statistical package SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for the analysis.

Results

shows Cronbach’s α coefficients of each indicator for the importance and performance scores. For all cases except one, the results showed Cronbach’s α coefficients above 0.76 (ranging from 0.794 to 0.958), offering evidence of fairly high to excellent internal consistency (Taber, Citation2018). In the case of the Physical Resources indicator (3 items) and the performance scores, the Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.689, slightly below the acceptable value of 0.7, which could indicate a problem with the items of the indicator (e.g. need to delete a specific item). However, the corrected item-total correlation coefficients ranged from 0.446 to 0.757, all above the 0.2 value recommended for including an item in a scale (Streiner & Norman, Citation1995).

Table 2. Cronbach’s α coefficients of each indicator under study for the importance and performance scores.

The initial analysis of the history of the respondents’ involvement in the provision of disability football revealed that each National Association has been delivering disability football for different time periods with an average of 10.4 years (SD = 8.67). Of all respondents that reported, 36% (n = 12) had between 0- and 5-years’ experience, while 9% (n = 3) reported over 21 years’ experience.

presents the overall mean scores of importance and performance for the seven indicators under analysis and the statistics and effect sizes of the tests performed. The results showed that the importance level was greater than their performance level for all the indicators, with importance-performance gap scores ranging from 1.09 to 1.62 points. The results showed that these differences were statistically significant for all the indicators once the Bonferroni correction was applied (all p < .0071). Large effect sizes (d ≥ 0.80) were found for all tests.

Table 3. Statistics and effect sizes of the tests for the overall mean scores of importance and performance for the seven indicators under analysis.

shows the IPA chart that enables the classification of disability football indicators according to their importance and performance. Sections 1 and 2 are standalone indicators both appearing in the Concentrate Here quadrant, whilst Section 3 contains four indicators, spread across three quadrants. Consistent among these results is higher performances in resource allocation than in areas of competence and training. In response to a limitation of IPA outlined earlier, these were accounted for as follows. One limitation in using the IPA chart as a diagnostic tool is the implications of crosshair placement subjectivity. If indicators fall very near the crosshairs, the item may shift from a strength to an area of concern, and as such, the item may or may not require further action. Below our results will show that no indicators fell on the crosshairs negating this limitation.

Discussion

As this paper represents an attempt to engage research in the practice space, our results stimulate a discussion on the priorities for the development of disability football across Europe. When considering these results within our conceptual framework we urge reader caution in assuming anything that falls within a “low priority” or “concentrate here” is somehow evidence of poor practice. To determine this outright, further research is required and we outline this in the section that follows.

To address research question 1 (Where are the NAs priorities for increasing the inclusion of PwD within European football?), the indicator of Disability Awareness was positioned in the “concentrate here” quadrant. Greater investment in developing the importance of this area is needed. Disability awareness training has been proven important in employment and educational settings in overcoming barriers that PwD face (Hayward et al., Citation2021), and by educating non-disabled staff in institutional settings about ableist oppression (Lalvani & Broderick, Citation2013; Townsend et al., Citation2020b) which can also be extended to critiquing the ableist basis from which much sport coaching has evolved (Townsend et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, it can positively influence hiring practices (Houtenville & Kalargyrou, Citation2012), suggesting that it can help redress the underemployment of PwD in all workplaces (Darcy et al., Citation2016) and begin to erode non-disabled privilege. These results provide evidence of the underlying importance of transferring not just the administrative responsibilities that comes with mainstreaming (Thomas & Guett, Citation2014), but developing awareness and investing in competencies that have the potential to challenge institutionalized ableism (Kitchin & Crossin, Citation2018; Macbeth, Citation2009). The sport also needs to examine the evidence on which the coaching of disability football is based, if coaching practices are developed in the context of disability awareness and acknowledging the diversity of disability, they are less likely to carry ableist thinking (Townsend et al., Citation2015). Additionally, it is plausible to suggest that investment in ongoing disability awareness training for all members of NA staff, not just those who work in disability football is needed to develop broader understanding of disability within NA’s that would enhance competencies across the organizations impacting on the decision makers in senior management positions.

For research question 2 (Where are the NAs priorities for developing disability football?), results indicate that disability football is in the “concentrate here” quadrant. Caution is urged as the margins between the mean lines in are minimal and the possibility of being scored a “system strength” could have been achieved. Given the diversity of programs offered that comprise disability football an organization’s level of resourcing can be stretched between many types of programmes. Full provision of all types of disability football would require access to a combination of indoor and outdoor pitches across a variety of surfaces along with various accessible amenities (support networks and facilities, see Darcy & Taylor, Citation2009) to support this. For example, football for people with different types of physical disabilities (cerebral palsy, amputee, spinal injury) requires that each has access to certain specialized equipment and facilities that may not be available to all NAs, depending on their size and resources.

The third question asked what resources and competencies are prioritized to underpin these developments? The results suggest some inconsistencies. While there are strengths in providing resource allocation to the area of disability football – particularly in the area intellectual resources – there is a “Low Priority” score for the competencies that underpin equality. Additionally, some resource allocations are “Possible Overkill” – where performance is rated than importance. While the availability of finance, facilities and staff should underpin all other areas, this “overkill” reflects the importance of an area has not been matched in its performance. In other words, throwing resources at disability football does not lead to a system strength because suitable investments in organizational competencies appear to be of relative low importance and performance.

In order to develop competence, a greater focus on inter-organizational partnerships is required. Inter-organizational partnerships have been shown as effective ways for non-profit organizations to overcome organizational weaknesses and achieve mutual benefits (Babiak et al., Citation2018; Jones et al., Citation2020), particularly in areas of social responsibility (Zeimers et al., Citation2019). Organizational motivations for these partnerships are an important area of inter-organizational partnership research (Le Pennec & Raufflet, Citation2018). However, from our contextual discussion above the motivations for developing disability football can vary between the myriad organizations that are involved in this field. We know that from previous research the challenges faced in prioritizing objectives are difficult when internal stakeholders view them as outside their sport’s traditional remit (Howe, Citation2007; Macbeth & Magee, Citation2006; Rowe et al., Citation2018). Macbeth and Magee (Citation2006) studying the English context of partially sighted football development found that conflicting objectives exacerbated interorganizational tensions. In England, the DSO for partially sighted football’s need to develop the grassroots was mostly incompatible with the NAs quest for performance-focused competitive success. Furthermore, Thomas and Guett (Citation2014) regarded National Sports Organizations as autonomous bodies that were generally poor at accepting the new responsibilities of mainstreaming disability sport (see Howe, Citation2007). As previous evidence from this context suggests that non-sport organizations from the disability community have expertise that enhance the services of mainstream sports organizations (Kitchin & Crossin, Citation2018; Macbeth, Citation2008), we reinforce the point that inter-organizational partnerships in this area are therefore vital of both organizational learning and capacity building (Babiak et al., Citation2018; Jones et al., Citation2020).

In addressing the final research question (What are the implications of these priorities for the European National Football Associations’ management of disability football?) we consider the implications of these priorities. Without the ambition to develop competence through disability awareness training and/or effective inter-organizational partnerships, then decisions regarding resource allocation are likely to be ill-informed and do little to undo or challenge long-standing ableist practices and transform these mainstream organizations into inclusive ones. Examples of areas that could warrant further investigation are revealed within the survey items. Although these are only aspects of a wider indicator the low importance and low priority given areas around research and competencies reflect thinking that existing practices are the most appropriate. Perhaps the lack of prioritization for disability awareness and the competencies that underpin genuine integration (Hums et al., Citation2003; Kitchin & Crossin, Citation2018) require more direct influence from the regional governing body. If UEFA are to genuinely champion diversity, inclusion, and accessibility in football like they claim (UEFA, Citation2019), instead of simply increasing the number of people playing disability football, then they need to invest increasing disability rights awareness. Disability rights awareness would acknowledge that ableism is a “guiding frame-work for how disability sport is organized” (Hammond et al., Citation2019, p. 319) and that ableist beliefs are present in the football workforce, as they are in other sport settings (Christiaens & Brittain, Citation2021). Indeed Townsend et al. (Citation2015, p. 93) suggest these beliefs treat PwD as a “homogenous group” and, the creation of a diverse variety of disability football programs, along with further engagement from disability football partners will start to broaden the football workforce’s understanding of disability. Adopting this leadership position would enable UEFA to increase its legitimacy in developing disability football, particularly in light of the complex governance of disability football. To do this, we draw on Christiaens and Brittain’s (Citation2021) suggestion that policy makers (in the present study’s case UEFA) should facilitate more effective collaborations between inter-organizational partners and funding allocations in the HatTrick programme should reflect this.

Conclusions, limitations, and further research

The findings from this novel study demonstrate that the development of European disability football has particular strengths and weaknesses. Strengths include the NAs leveraging their intellectual resources to promote disability football across their countries and the wider UEFA region. We also revealed some weaknesses that could be addressed by investment in better training or the creation of better inter-organizational partnerships. We informed the analysis of these performance findings through the lens of ableism to explore the possibilities of its influence on priorities. We do not attempt to say that ableism is the reason why the results are the way they are; however, NAs should realize that investments in the competencies around equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) could enhance the social awareness of the football workforce to champion these principles. The prioritization of EDI could benefit PwD and also women, ethnic minorities, first nations people and LGBTQI+ communities, and intersections of these. While our analysis was focused on NAs in the UEFA region, we argue that investment in organizational learning about the competencies that underpin effective partnerships in sport development are relevant for all mainstream sports organizations and their efforts to develop disability sport, or indeed sport for any marginalized community (Babiak et al., Citation2018).

Our primary limitation in this research was that it was conducted by a group of non-disabled researchers. The principle of Nothing About Us, Without Us (Charlton, Citation1998) was in part covered by consulting with the industry experts who were also PwD so that we could “ground” the research instruments to those with personal experience of disability; however, our approach and perspective is influenced by our non-disabled status. As with all quantitative surveys, there are some limitations in our approach. In line with the aims of this study, purposive sampling was used to obtain a sample from the NAs, mainstream football organizations within to the UEFA region. The absence of France and Spain from these results was disappointing as insights from these two large nations and the specific contexts of disability football in each lessens the overall picture. Nevertheless, we were able to attract NAs from across Europe both large (the inclusion of England, Germany and Italy covers 3/5 of nations who have the “big leagues”) and small. Future endeavours will seek to ensure that even more countries within this region are included.

There are several avenues for further research in this and related areas. Firstly, the ableism-IPA conceptual lens has provided and contextualized areas of importance, areas to improve and refine, and a number of areas that are deemed low priority. Secondly, this study has focused upon the managerial perspectives of those within NAs and, as such, the perspectives of the participants and the organizational partners (DSOs, clubs, leagues, charities, etc.) are needed on a similar scale to provide additional data for a more holistic understanding of the area. Nevertheless, these findings provide a foundation for both further research and practical action in the development of disability football across Europe. Thirdly, greater frequency of inter-organizational partnerships between NAs and organizations at the grassroots with DSOs is required, ensuring that not only players but staff too can experience and learn from different cultural approaches to the development of disability football. We posit that if current exchanges of DSO and NA staff occurs solely at major tournaments, then this limits the possibility of sharing knowledge around grassroots football cultures, which as a separate area of practice could benefit coaches’ competencies (knowledge and understanding of disability). This learning could then ensure that NAs provide “Football for All” that is not based on the normative expectations of the non-disabled majority who, arguably have always organized football, but one that could facilitate grassroots opportunities for football culture and disability sport culture to learn from each other.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In this paper, we use the term mainstream as a reference to non-disabled social institutions, specifically football clubs/association that are transitioning into more inclusive organizations (Kitchin & Crossin, Citation2018).

2 Surveys were deemed unusable as they were significantly incomplete, in one case only the demographic data was supplied, in the other three the respondents had indicated some importance scores only with no corresponding scores for performance. Despite SPSS being able to handle missing data, we felt too much data was missing from these four responses.

References

- Andrew, D. P. S., Pedersen, P. M., & McEvoy, C. D. (2011). Research methods and design in sport management. Human Kinetics.

- Atherton, M., & Macbeth, J. (2017). Disability and football. In J. Hughson, K. Moore, R. Spaaij, & J. Maguire (Eds.), Routledge handbook of football studies (pp. 279–292). Routledge.

- Atherton, M., Russell, D., & Turner, G. H. (1999). Playing to the flag: A history of deaf football and deaf footballers in Britain. The Sports Historian, 19(10), 38–60. doi:10.1080/17460269909445807

- Atherton, M., Turner, G. H., & Russell, D. (2001). More than a match: The role of football in Britain’s deaf community. Soccer and Society, 2(3), 22–43. doi:10.1080/714004857

- Azzopardi, E., & Nash, R. (2013). A critical evaluation of importance-performance analysis. Tourism Management, 35, 222–233. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2012.07.007

- Babiak, K., Thibault, L., & Willem, A. (2018). Mapping research on interorganizational relationships in sport management: Current landscape and future research prospects. Journal of Sport Management, 32(3), 272–294. doi:10.1123/jsm.2017-0099

- Blauwet, C. A. (2019). More than just a game: The public health impact of sport and physical activity for people with disabilities (The 2017 DeLisa lecture). American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 98(1), 1–6. doi:10.1097/PHM.0000000000001063

- Bottomley, P. A., Doyle, J. R., & Green, R. H. (2000). Testing the reliability of weight elicitation methods: Direct rating versus point allocation. Journal of Marketing Research, 37(4), 508–513. doi:10.1509/jmkr.37.4.508.18794

- Brittain, I. (2010). The paralympic games explained. Routledge.

- Brittain, I., Biscaia, R., & Gérard, S. (2020). Ableism as a regulator of social practice and disabled peoples’ self-determination to participate in sport and physical activity. Leisure Studies, 39(2), 209–224. doi:10.1080/02614367.2019.1694569

- Charlton, J. I. (1998). Nothing about us, without us: Disability oppression and empowerment. UCLA Press.

- Christiaens, M., & Brittain, I. (2021). The complexities of implementing inclusion policies for disabled people in UK non-disabled voluntary community sports clubs. European Sport Management Quarterly, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2021.1955942

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Cottingham, M., Hums, M., Jeffress, M., Lee, D., & Richard, H. (2018). Women of power soccer: Exploring disability and gender in the first competitive team sport for powerchair users. Sport in Society, 21(11), 1817–1830. doi:10.1080/17430437.2017.1421174

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. doi:10.1007/BF02310555

- Cunningham, G. B., & Warner, S. (2019). Baseball 4 all: Providing inclusive spaces for persons with disabilities. Journal of Global Sport Management, 4(4), 313–330. doi:10.1080/24704067.2018.1477518

- Damen, K. M. S., Takken, T., de Groot, J. F., Backx, F. J. G., Radder, B., Roos, I. C. P. M., & Bloemen, M. A. T. (2020). 6-minute push test in youth who have spina bifida and who self-propel a wheelchair: Reliability and physiologic response. Physical Therapy, 100(10), 1852–1861. doi:10.1093/ptj/pzaa121

- Darcy, S., Lock, D., & Taylor, T. (2017). Enabling inclusive sport participation: Effects of disability and support needs on constraints to sport participation. Leisure Sciences, 39(1), 20–41. doi:10.1080/01490400.2016.1151842

- Darcy, S., & Taylor, T. (2009). Disability citizenship: An Australian human rights analysis of the cultural industries. Leisure Studies, 28(4), 419–441. doi:10.1080/02614360903071753

- Darcy, S., Taylor, T., & Green, J. (2016). ‘But I can do the job’: Examining disability employment practice through human rights complaint cases. Disability & Society, 31(9), 1242–1274. doi:10.1080/09687599.2016.1256807

- Eskildsen, J. K., & Kristensen, K. (2006). Enhancing importance–performance analysis. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 55(1), 40–60. doi:10.1108/17410400610635499

- FIPFA. (2017). The FIPFA classification rulebook. https://fipfa.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Classification-Rulebook.pdf

- Football Association, the (FA). (n.d.). An introduction to disability football at the FA. http://www.thefa.com/get-involved/player/disability/disability-football-overview

- Frere, J. (2007). The history of ‘modern’ amputee football. In Centre of Excellence Defence Against Terrorism (Ed.), Amputee sport for victims of terrorism (pp. 1–7). IOS Press.

- García, B., & Welford, J. (2015). Supporters and football governance, from customers to stakeholders: A literature review and agenda for research. Sport Management Review, 18(4), 517–528. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2015.08.006

- Garcia, B., de Wolff, M., Welford, J., & Smith, B. (2017). Facilitating inclusivity and broadening understandings of access at football clubs: The role of disabled supporter associations. European Sport Management Quarterly, 17(2), 226–243. doi:10.1080/16184742.2016.1246584

- Goodley, D. (2014). Dis/ability studies: Theorising disablism and ableism. Routledge.

- Griffin, T., & Edwards, D. (2012). Importance–performance analysis as a diagnostic tool for urban destination managers. Anatolia, 23(1), 32–48. doi:10.1080/13032917.2011.653630

- Hammond, A., & Jeanes, R. (2018). Federal government involvement in Australian disability sport, 1981–2015. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 35(5), 431–447. doi:10.1080/09523367.2017.1337000

- Hammond, A., Jeanes, R., Penney, D., & Leahy, D. (2019). ‘I feel we are inclusive enough’: Examining swimming coaches’ understandings of inclusion and disability. Sociology of Sport Journal, 36(4), 311–321. doi:10.1123/ssj.2018-0164

- Hayward, L., Fragala-Pinkham, M., Schneider, J., Coe, M., Vargas, C., Wassenar, A., Emmons, M., Lizzio, C., Hayward, J., & Torres, D. (2021). Examination of the short-term impact of a disability awareness training on attitudes toward people with disabilities: A community-based participatory evaluation approach. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 37(2), 257–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2019.1630879. Advance online publication.

- Houtenville, A., & Kalargyrou, V. (2012). People with disabilities: Employers’ perspectives on recruitment practices, strategies, and challenges in leisure and hospitality. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 53(1), 40–52. doi:10.1177/1938965511424151

- Howe, P. D. (2007). Integration of Paralympic athletes into athletics Canada. International Journal of Canadian Studies, 35(35), 133–150. doi:10.7202/040767ar

- Hums, M. A., Moorman, A. M., & Wolff, E. A. (2003). The inclusion of the paralympics in the Olympic and Amateur Sports Act: Legal and policy implications for integration of athletes with disabilities into the United States Olympic Committee and national governing bodies. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 27(3), 261–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193732503255480

- IBSA. (2019). Call for bids to host IBSA Blind Football Women's World Championships. http://www.ibsasport.org/news/1812/call-for-bids-to-host-ibsa-blind-football-womens-world-championships

- IBSA. (2020a). About football. https://blindfootball.sport/about-football/overview/

- IBSA. (2020b). IBSA blind football women’s worlds postponed to 2021. https://www.ibsasport.org/news/2012/ibsa-blind-football-womens-worlds-postponed-to-2021

- IFCPF. (n.d.). History of CP football. https://www.ifcpf.com/history

- Jeffress, M. S., & Brown, W. J. (2017). Opportunities and benefits for powerchair users through power soccer. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 34(3), 235–255. doi:10.1123/apaq.2016-0022

- Jones, G. J., Misener, K., Svensson, P., Taylor, E., & Hyun, M. (2020). Analyzing collaborations involving nonprofit youth sport organizations: A resource dependency perspective. Journal of Sport Management, 34(3), 270–281. doi:10.1123/jsm.2019-0054

- Jouira, G., Srihi, S., Ben Waer, F., Rebai, H., & Sahli, S. (2021). Dynamic balance in athletes with intellectual disability: Effect of dynamic stretching and plyometric warm-ups. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 30(3), 401–407. doi:10.1123/jsr.2020-0100

- Kappelides, P., & Spoor, J. (2019). Managing sport volunteers with a disability: Human resource management implications. Sport Management Review, 22(5), 694–707. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2018.10.004

- Kasum, G. (2019). Disabled sports – steps towards a reduced exclusion and a new value paradigm of the Serbian society. Physical Culture / Fizicka Kultura, 73(1), 22–23. https://doaj.org/article/d892a77d4a3a426d91531f8853e21e45

- Kijanskiy, I. (2008). The role of socially-focused marketing in the development of amputee football in Russia. In Centre of Excellence – Defence Against Terrorism (Ed.), Amputee sports for victims of terrorism (pp. 83–86). IOS Press.

- Kitchin, P. J., & Crossin, A. (2018). Understanding which dimensions of organisational capacity support the vertical integration of disability football clubs. Managing Sport and Leisure, 23(1/2), 28–47. doi:10.1080/23750472.2018.1481764

- Kitchin, P. J., & Howe, P. D. (2014). The mainstreaming of disability cricket in England and Wales: Integration ‘one game’ at a time. Sport Management Review, 17(1), 65–77. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2013.05.003

- LaLiga.com. (2020). ‘Qué es Laliga Genuine Santander? https://www.laliga.com/laliga-genuine-santander/que-es

- Lalvani, P., & Broderick, A. A. (2013). Institutionalized ableism and the misguided “disability awareness day”: Transformative pedagogies for teacher education. Equity and Excellence in Education, 46(4), 468–483. doi:10.1080/10665684.2013.838484

- Legg, D., Fay, T., Hums, M. A., & Wolff, E. (2009). Examining the inclusion of wheelchair exhibition events within the Olympic Games 1984-2004. European Sport Management Quarterly, 9(3), 243–258. doi:10.1080/16184740903023997

- Le Pennec, M., & Raufflet, E. (2018). Value creation in inter-organizational collaboration: An empirical study. Journal of Business Ethics, 148(4), 817–834. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-3012-7

- Levenburg, N. M., & Magal, S. R. (2004). Applying importance–performance analysis to evaluate e-business strategies among small firms. E-Service Journal, 3(3), 29–48. doi:10.2979/esj.2004.3.3.29

- Macbeth, J. L. (2008). Equality issues within partially sighted football in England. In C. Hallinan & S. Jackson (Eds.), Social and cultural diversity in a sporting world (pp. 65–80). Emerald.

- Macbeth, J. L. (2009). Restrictions of activity in partially sighted football: Experiences of grassroots players. Leisure Studies, 28(4), 455–467. doi:10.1080/02614360903071696

- Macbeth, J. L., & Magee, J. (2006). ‘Captain England? Maybe one day I will’: Career paths of elite partially sighted footballers. Sport in Society, 9(3), 444–462. doi:10.1080/17430430600673464

- Martilla, J. A., & James, J. C. (1977). Importance-performance analysis. Journal of Marketing, 41(1), 77–79. doi:10.1177/002224297704100112

- McLoughlin, G., Weisman Fecske, C., Castaneda, Y., Gwin, C., & Graber, K. (2017). Sport participation for elite athletes with physical disabilities: Motivations, barriers, and facilitators. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 34(4), 421–441. doi:10.1123/apaq.2016-0127

- Misener, L., & Darcy, S. (2014). Managing disability sport: From athletes with disabilities to inclusive organisational perspectives. Sport Management Review, 17(1), 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2013.12.003

- Paramio-Salcines, J. L., Downs, P., & Grady, J. (2016). Football and its communities: The celebration of Manchester United FC’s ability suite. Soccer in Society, 17(5), 770–791. doi:10.1080/14660970.2015.1100435

- Paramio-Salcines, J. L., & Kitchin, P. J. (2013). Institutional perspectives on the implementation of disability legislation and services for spectators with disabilities in European professional football. Sport Management Review, 16(3), 337–348. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2012.11.002

- Patatas, J. M., De Bosscher, V., Derom, I., & De Rycke, J. (2020). Managing parasport: An investigation of sport policy factors and stakeholders influencing para-athletes’ career pathways. Sport Management Review, 23(5), 937–951. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2019.12.004

- Pavitt, M. (2019). Paralympic Games sports for Paris 2024 unchanged from Tokyo 2020 as cerebral palsy football misses out on place. Inside the Games. https://www.insidethegames.biz/articles/1074653/paralympic-games-sports-for-paris-2024-unchanged-from-tokyo-2020-as-cerebral-palsy-football-misses-out-on-place

- Polley, M. (2011). The British Olympics: Britain’s Olympic heritage 1612–2012. English Heritage.

- Powis, B., & Macbeth, J. (2020). “We know who is a cheat and who is not. But what can you do?”: Athletes’ perspectives on classification in visually impaired sport. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 55(5), 588–602. doi:10.1177/1012690218825209

- Rial, A., Rial, J., Varela, J., & Real, E. (2008). An application of importance-performance analysis (IPA) to the management of sport centres. Managing Leisure, 13(3–4), 179–188. doi:10.1080/13606710802200878

- Richard, R., Joncheray, H., & Dugas, E. (2017). Disabled sportswomen and gender construction in powerchair football. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 52(1), 61–81. doi:10.1177/1012690215577398

- Robertson, J., Emerson, E., Baines, S., & Hatton, C. (2018). Self-reported participation in sport/exercise among adolescents and young adults with and without mild to moderate intellectual disability. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 15(4), 247–254. doi:10.1123/jpah.2017-0035

- Rowe, K., Sherry, E., & Osbourne, A. (2018). Recruiting and retaining girls in table tennis: Participant and club perspectives. Sport Management Review, 21(5), 504–518. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2017.11.003

- Runswick, O. R., Ravensbergen, R. H. J. C., Allen, P. M., & Mann, D. L. (2021). Expert opinion on classification for footballers with vision impairment: Towards evidence-based minimum impairment criteria. Journal of Sports Sciences, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2021.1881301

- Shapiro, D. R., & Pitts, B. G. (2014). What little do we know: Content analysis of disability sport in sport management literature. Journal of Sport Management, 28(6), 657–671. doi:10.1123/JSM.2013-0258

- Silva, C. F., & Howe, P. D. (2019). Sliding to reverse ableism: An ethnographic exploration of (Dis)ability in sitting volleyball. Societies, 9(2), 41. doi:10.3390/soc9020041

- Streiner, D. L., & Norman, G. L. (1995). Health measurement scales: A practical guide to their development and use (2nd ed). Oxford University Press.

- Stride, A., & Fitzgerald, H. F. (2011). Girls with learning disabilities and ‘football on the brain’. Soccer & Society, 12(3), 457–470. doi:10.1080/14660970.2011.568111

- Taber, K. S. (2018). The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research in Science Education, 48(6), 1273–1296. doi:10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2

- Tarrant, M. A., & Smith, E. K. (2002). The use of a modified importance-performance framework to examine visitor satisfaction with attributes of outdoor recreation settings. Managing Leisure, 7(2), 69–82. doi:10.1080/13606710210137246

- Thomas, N., & Guett, M. (2014). Fragmented, complex, and cumbersome: A study of disability sport policy and provision in Europe. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 6(3), 389–406. doi:10.1080/19406940.2013.832698

- Townsend, J., Stone, G. A., Murphy, E., Crowe, B. M., Hawkins, B. L., & Duffy, L. (2020a). Examining attitude change following participation in an international adaptive sports training. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 54(3), 276–290. doi:10.18666/TRJ-2020-V54-I3-10112

- Townsend, M., Henry, J., & Holt, R. R. (2020b). Learning disability training and probation officer knowledge. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities and Offending Behaviour, 11(2), 117–131. doi:10.1108/JIDOB-10-2019-0018

- Townsend, R. C., Smith, B., & Cushion, C. (2015). Disability sports coaching: Towards a critical understanding. Sports Coaching Review, 4(2), 80–98. doi:10.1080/21640629.2016.1157324

- UEFA. (2019). UEFA and Fare unite to promote diversity and inclusion. UEFA.com https://www.uefa.com/insideuefa/social-responsibility/news/0256-0f8e71416375-a2a5c778baa3-1000–uefa-and-fare-unite-to-promote-diversity-and-inclusion/?referrer=%2Finsideuefa%2Fnews%2Fnewsid%3D2630269

- UEFA. (n.d.). HatTrick programme overview. UEFA. https://www.uefa.com/MultimediaFiles/Download/uefaorg/HatTrick/02/61/77/48/2617748_DOWNLOAD.pdf

- UEFA/Schwery Consulting. (2017). UEFA’S Football & social responsibility: Strategy review and recommendations. https://www.uefa.com/MultimediaFiles/Download/uefaorg/General/02/60/04/99/2600499_DOWNLOAD.pdf

- UN – United Nations. (2006). Convention of the rights of persons with disabilities (CRPwD). https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html

- van der Niet, A. G. (2010). Football in post-conflict Sierra Leone. African Historical Review, 42(2), 48–60. doi:10.1080/17532523.2010.517396

- WHO – World Health Organization. (2011). World report on disability. WHO.

- Wicker, P., & Breuer, C. (2014). Exploring the organizational capacity and organizational problems of disability sport clubs in Germany using matched pairs analysis. Sport Management Review, 17(1), 23–34. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2013.03.005

- World Amputee Football Federation. (n.d.). Amputee Soccer – the beginnings. http://www.worldamputeefootball.com/history.htm

- Zeimers, G., Anagnostopolous, C., Zintz, T., & Willem, A. (2019). Examining collaboration among nonprofit organizations for social responsibility programs. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 48(5), 953–974. doi:10.1177/0899764019837616

- Zhang, J. J., Lam, E. T. C., Cianfrone, B. A., Zapalac, R. K., Holland, S., & Williamson, D. P. (2011). An importance–performance analysis of media activities associated with WNBA game consumption. Sport Management Review, 14(1), 64–78. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2010.03.001