ABSTRACT

Rationale/Purpose

Charitable foundations constitute the prime mechanism for the implementation of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in sport. The relationship between the charitable foundation and the founding professional team sport organization (PTSO) is unique. Although extant research has shown that trust can be an instrumental predictor of organizational performance, we know little of the role of its main component, namely trustworthiness, in the context of CSR implementation through charitable foundations.

Design/Methodology/Approach

Drawing on the UK’s football setting, an online survey (n = 124) was used to measure (through CFA and SEM and SPSS AMOS 21) the perceived trustworthiness of charitable foundation employees by their counterparts in PTSOs, and their perceived contribution to the PTSO’s performance.

Findings

Findings reveal PTSO’s employees perceive their counterparts in the foundations as being trustworthy and that their CSR activities contribute to the PTSO’s performance. Trustworthiness is a key predictor of the perception that the implementation of CSR-related initiatives through foundations contribute to the perceived performance of the PTSO.

Practical implications

Managers should facilitate trustworthy behavior between PTSOs’ employees and their counterparts in the foundations. The competence and predictability of employees of the foundation should be enhanced.

Research contribution

This study demonstrates the importance of trustworthiness between employees from organizational entities driven by different goals.

The implementation of corporate social responsibility (CSR) through the establishment of a charitable foundationFootnote1 (Husted, Citation2003) has become a common practice in most industries, including sport (Kolyperas et al., Citation2016; Minefee et al., Citation2015; Pedrini & Minciullo, Citation2011). Sport organizations are unique implementers of CSR due to specific features like passion, commercialization, media scrutiny, a complex set of stakeholders and, strong connections to the community (Babiak & Wolfe, Citation2009; Smith & Westerbeek, Citation2007). Charitable foundations are generally characterized by (a) the dependence on a company for funding, (b) close ties with the founding company because of annual endowments and non-financial resources dependence, and (c) the presence of founding company’s representatives in the board of directors (Minciullo & Pedrini, Citation2015).

In the sporting context, the foundation depends on their founding professional sport team organizations (PTSOs)' network and resources as well as other partners to diversify revenue streams (Bingham & Walters, Citation2013; Kolyperas et al., Citation2016). The partial dependency of the foundation on the PSTO determines the CSR activities and their impact on the beneficiaries, which ultimately have a positive return on the sporting brand (the team and the foundation being considered one organizational unit, see Anagnostopoulos & Winand, Citation2019). Consequently, as indicated by Bingham and Walters (Citation2013) “it is important for charitable organizations to manage the relationship with the funding organizations on which they are dependent” (p. 613). Previous studies (Anagnostopoulos et al., Citation2017; Kolyperas et al., Citation2016) have also shown that foundations seek to secure a large and stable buy-in from PSTO’s employees in exchange for contributing to their business objectives. The principle underpinning these efforts is that performance in both business and social terms cannot be advanced by either the foundation (being “independent”) or the PSTO (being “dependent”) in isolation but rather through mutual and complementary arrangements (Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005).

As such, the nature of the relationship between the charitable foundations and the PTSOs represents a unique CSR implementation mode (Husted, Citation2003) characterized by inter-organizational relationship features. According to Minciullo and Pedrini (Citation2015, p. 216), “charitable foundations differ from other foundations because of their ties with a company (the ‘founding company’); such ties are strengthened by frequent and repeated interactions, committed involvement, and a high level of trust [emphasis added] between the organizations”. Indeed, a common denominator of impactful CSR implementation for both organizational entities is trust (Jamali et al., Citation2011; Kihl et al., Citation2014; Maon et al., Citation2009). Scholarly activity has empirically shown that trust, defined as a firm belief in the reliability, truth, or ability of someone or something, impacts positively upon inter-organizational relationships (Babiak & Thibault, Citation2008; Inkpen & Currall, Citation2004; Vangen & Huxham, Citation2003). Trust is also a critical factor for competitive advantage and consequently the overall organizational performance (Barney & Hansen, Citation1994; Winand et al., Citation2013). The key component of trust, namely trustworthiness (Mayer et al., Citation1995), is an important asset for scaling up both business and social benefits derived from CSR initiatives through this mode. Trustworthiness is defined as the quality of the trustee (in this case, the quality charitable foundation employees have so to be trusted) as perceived by their counterparts in the founding company (i.e. PTSO). Therefore, analyzing the perceived quality of foundation employees helps to further understand their relationship with PTSO employees and, eventually the impact foundation activities have on the PTSO’s perceived performance. Trustworthiness might influence the relationship between both entities, and eventually facilitate timely information, knowledge exchange, resource access (Huxham & Vangen, Citation1996), and might ultimately lead to enhancing the impact of community-oriented work through this CSR implementation mode.

The influence of trust and trustworthiness on the relationship between charitable foundations and founding PTSOs deserves a particular attention because studies in sport management have empirically pointed out “dysfunctional affiliations” (Anagnostopoulos & Shilbury, Citation2013); (missed) opportunities for value co-creation (Kolyperas et al., Citation2016; Walters & Chadwick, Citation2009); communication (mis-)alignments (Cobourn & Frawley, Citation2017); or contrasting portfolios and organizational agendas (Sanders et al., Citation2021). A lack of trust between partners practicing CSR-related programs could influence the quality of the relationship (Ariño et al., Citation2005; Jamali et al., Citation2011), the impact these programs have on the targeted beneficiaries, and ultimately, the overall organizational performance of each party involved in the process. However, the scholarly sport management community knows little about the notion of trust in this unique organizational setting.

Clearly, the noted oversights need a redress. The aim of this study is to increase knowledge on trust by examining its role in the relationship between PTSOs and their charitable foundation responsible for the implementation of CSR. The purpose of the present study, therefore, is threefold. First, to measure the perceived trustworthiness of the charitable foundations by the PTSOs; second, to measure the extent to which the PTSOs perceive that charitable foundations’ activities contribute to the former’s performance; and third, to analyze whether trustworthiness can predict the perceptions from PTSOs’ employees that the foundation’s activities contribute to the former’s performance.

The context of the research is particularly rich and unique as it looks at the UK football industry; that is, the professional football clubs as founding companies and their charitable foundations. English Premier League (EPL) clubs and Scottish Premier League (SPL) clubs largely mandate the implementation of CSR activities through their legally distinct charitable foundations (Anagnostopoulos et al., Citation2014; Anagnostopoulos & Shilbury, Citation2013), responsible for social and educational activities with the community. As such, the present study advances understanding of the interrelations between CSR in professional football clubs.

Understanding the role of trustworthiness (Dietz & Den Hartog, Citation2006) offers both theoretical and managerial implications for well-thought-through CSR programs that have positive impact on social (charitable foundation) and business (founding company/PTSO) performance alike (Molteni & Pedrini, Citation2010). An important theoretical contribution of this study to the relationship between trust and inter-organizational relationship literature is a model that explains how the components of trustworthiness affect the relationship between these entities. By paying attention to the issue of trust in relation to implementing CSR, this study also sheds additional light on this CSR implementation mode and on how trustworthiness and its components shape the work of these charitable foundations.

The article is organized as follows. In the next section, we elucidate on the conceptual foundations of trust and the theoretical approaches that underpin the present study. Next, we offer the contextual background within which this work was conducted, together with a detailed description of the method we employed. We then report the findings of our statistical analysis before we discuss these results vis-a-vis the extant literature on CSR implementation. We conclude by offering the implications for theory development and managerial practice as well as the limitations of this study and suggestions for future avenues of inquiry.

Literature review and theoretical foundations

CSR implementation through charitable foundations

Although the social responsibility of the contemporary businesses shall not be limited to community-related projects alone delivered by a company’s charitable “arm” (Walzel et al., Citation2018), the present study aligns itself with the framework proposed by Walker and Parent (Citation2010), which integrates diverse notions regarding the social involvement of sport organizations. Within it, “CSR” refers to the first level of engagement as “a localised, community-based focus (of PTSOs) regarding their social agenda which is focused on local philanthropy and community stewardship” (Walker & Parent, Citation2010, p. 207).

Football is the most investigated context for CSR research in PTSOs (Walzel et al., Citation2018). To date, studies have mostly explored football in the UK (England and Scotland) and European (Spain, Switzerland, Italy, Turkey, Portugal, Belgium, Greece, Germany, and France) contexts, but also in the United States and Asia (see for a review Zeimers et al., Citation2019a). The large domination of CSR in professional football clubs in the UK is due to their strongest institutionalized forms of CSR in European football (Walters & Tacon, Citation2010).

General CSR implementation research investigates the complex strategic and cognitive process underlying the unfoldment of CSR principles and practices within organizations (Maon et al., Citation2009). According to Husted (Citation2003), organizations commonly follow three different approaches to implement CSR: in-house (i.e. internal department), foundation or collaboration. The relationship between the charitable foundation and the founding PTSOs represents an implementation mode with elements of an inter-organizational relationship through which CSR activities are executed (Zeimers et al., Citation2019a). Inter-organizational relationships are defined as “cooperative, inter-organizational relationship(s) that (are) negotiated in an ongoing communicative process, and which rely on neither market nor hierarchical mechanisms of control” (Hardy et al., Citation2003, p. 323). The relationship between a foundation and a PSTO is a unique form of collaboration between distinct organizations from the same brand, with the foundations created and mandated by the PSTOs to address social issues and with which there is a shared understanding of responsibilities and a commitment of resources (Selsky & Parker, Citation2005).

The sport-CSR literature identified unique and distinctive features of professional football clubs and their foundations (for a review see Zeimers et al., Citation2019a). In the sporting context, the foundations are what Anheier (Citation2001) calls “operative foundations”; that is, organizations that implement and coordinate CSR projects. They pursue relevant charitable purposes such as supporting and educating those in need in the local community and promoting community participation in healthy programs (Rowe et al., Citation2019; Thomas, Citation2018). Several studies (e.g. Walters & Chadwick, Citation2009; Walters & Panton, Citation2014) have provided a good picture of the perceived benefits the implementation of these CSR programs can secure.

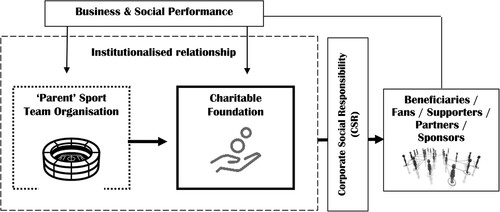

Although some structural links exist between the foundation and the PTSO (i.e. composition of the boards and funding), the organizations are legally separate entities. The foundation is an independent entity, and this is reflected in its ability to take their own decisions, decide on beneficiaries, and draw their own policies and business plans (Thomas, Citation2018). Moreover, it is good practice to ensure that at least a majority of the board of trustees are independent of the PTSO (i.e. are not directors, employees or shareholders of the PTSO) (Thomas, Citation2018). Therefore, these links enable closer and integrated ties between these distinct entities (Anagnostopoulos et al., Citation2017). In this context, the founding PTSO and the charitable foundation hold an institutional relationship; (that is, the PTSO supports the foundation at its discretion by, for example, agreeing to players/coaches engagement, marketing, underwriting losses, and providing facilities and equipment, (see Anagnostopoulos, Citation2013) to exchange resources and achieve distinct but interrelated social and business objectives (Anagnostopoulos & Winand, Citation2019). ().

Trust relationship

Trust is defined as the willingness “to be vulnerable to the actions of another party” (Mayer et al., Citation1995, p. 712) as it is expected that the trustee (i.e. individual who is trusted) will undertake a task of relevance to the trustor (i.e. individual who trusts). Trust is socially embedded between parties, and its nature is shaped by social exchange (Molm et al., Citation2000). Social exchange theory (SET) (Blau, Citation1964) explains different outcomes emerging from interaction between individuals or organizations so that each party in a social exchange relationship should repay any benefits obtained (Lioukas & Reuer, Citation2015). One of these outcomes is the emergence of trust between individuals or organizations, which is rooted in reciprocal exchange (Molm et al., Citation2000). It is expected that the trustee will not exploit the trustor and according to the reciprocity principle, core to SET (Blau, Citation1964), they give benefits to one another directly or indirectly (Molm et al., Citation2007). For example, a founding company supports its charitable foundation with financial and/or contributions-in-kind with the view that the latter will juxtapose a positive image in the community where the former exists and operates.

In the context of inter-organizational relationships, trust is the essence of collaboration because it facilitates or inhibits a situation where parties are investing resources (Bryson et al., Citation2015). Bryson et al. (Citation2006, p. 47) contend that, paradoxically, trust “is both the lubricant and the glue—that is, it facilitates the work of collaboration, and it holds the collaboration together”. Building trust between partners is an ongoing requirement for successful collaborations as they require “much effort and careful relational processes” (Austin & Seitanidi, Citation2012, p. 742). Trust has been found to be crucial for effective sport collaborations (Babiak & Thibault, Citation2008; Lefebvre et al., Citation2021). CSR studies have depicted trust as a necessary condition for a successful CSR implementation (Jamali et al., Citation2011; Maon et al., Citation2009). In the CSR-sport context, Walters and Anagnostopoulos (Citation2012) identified that inter-personal trust is a key attribute of all stages of a social partnership and, of the evaluation process. Zeimers et al. (Citation2020) also found that trust between board members and staff contributed to develop CSR initiatives. In sport governance literature, the role of trust has been examined mainly in relation to collaboration between boards (e.g. O’Boyle & Shilbury, Citation2016) or between board members (e.g. Takos et al., Citation2018) rather than between employees that largely serve the same brand but who have different organizational agendas and different roles in the CSR implementation process (Maon et al., Citation2009).

Although CSR literature has demonstrated that successful CSR activities lead to positive perceived trustworthiness (Lin-Hi et al., Citation2015; Van Herpen et al., Citation2003), charitable foundations are often viewed derogatorily as mere PR vehicles for the founding companies (Minefee et al., Citation2015). The ties between the foundation and the founder are strengthened by a high level of trust between the entities (Minciullo & Pedrini, Citation2015). In addition, the overreliance these charities have on resources from the founding companies leads to an excessive closeness that jeopardizes the foundations’ independence by turning a “trust” relationship into a “power” relationship (Kolyperas et al., Citation2016). Moreover, PSTOs in England (for a national business and policy context review see Bingham & Walters, Citation2013; Walters & Panton, Citation2014) are pressured to establish a foundation to receive funding from the Premier League which might also influence the relationship, and thus trust between clubs and the foundation more than in other industries. Against this background, the question whether employees in PTSOs trust their counterparts in the charitable foundations for concrete or less explicit contribution to the PTSOs’ objectives is a current research and managerial gap.

SET considers constant relationship management and exchange of information as critical for success (Sia et al., Citation2008), and therefore mutual trust between parties play a key role in successful social exchange (Schoenherr et al., Citation2015). It is important that partners communicate and work together in mutual support and that their relationship is based on personal trust, integrity, and honesty (Spence, Citation2016). However, partners are not obliged to return benefits or fully engage in reciprocal exchange. The level of uncertainty surrounding social exchange prompts individuals to trust one another (Cook et al., Citation2013) which holds the risk of non-reciprocity (Molm, Citation1994; Molm et al., Citation2007); that is, a partner giving but receiving little or nothing from the other party. Risk is inherent in the trust relationship and enables exchange partners to prove their trustworthiness to one another (Molm et al., Citation2007).

The conditions that surround these exchanged relationships determine the level of trust between parties. These conditions originate from the partners’ characteristics and reputation, the context of the relationship and previous experiences partners had with each other (Lee et al., Citation2012; Ring, Citation1996). Exchanges and direct experiences between partners influence how they view one another, their capabilities and trustworthiness (Lewicki & Bunker, Citation1996). The frequency and significance of exchanges, attributed intentions to the trustee, as well as individual interpretation of the success (or failure) of activities carried out together or for one another are amongst the important factors that condition the trust relationship (Ariño et al., Citation2001; Rousseau et al., Citation1998). When exchanges between same partners are occurring repetitively over time, they are less likely to exploit one another and trust is greater (Molm et al., Citation2007) because the potential for positively resolving disagreements increases, thereby enhancing how partners view each other (Das & Teng, Citation1998).

Components of trustworthiness

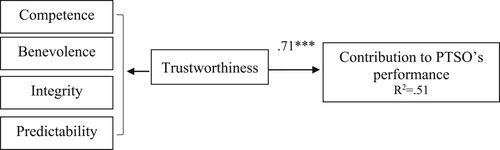

Trustworthiness is the perceived quality of the trustee by the trustor, whereas trust is what the trustor does (Mayer et al., Citation1995; Sharp et al., Citation2013). In line with Dietz and Den Hartog’s (Citation2006) study, perceived trustworthiness is seen as a belief that one’s action will result in positive outcome for oneself and is a strong predictor of the decision to trust someone (Mayer et al., Citation1995). Trustworthiness is composed of distinctive factors with the most commonly cited being competence or ability, benevolence, integrity (Dietz & Den Hartog, Citation2006; Mayer et al., Citation1995), as well as predictability (Cunningham & McGregor, Citation2000; Mishra, Citation1996). Competence refers to the skills and knowledge enabling someone to undertaking specific tasks. Benevolence relates to the perception that a trustee will act in goodwill, and in mutual interest with the trustor. Integrity means the adherence of the trustee to a set of principles (e.g. honesty and fairness) acceptable to the trustor. Finally, predictability refers to the consistency and regularity of the trustee’s behavior (Dietz & Den Hartog, Citation2006; Mayer et al., Citation1995; Sharp et al., Citation2013). From their review on organizational trust, Dietz and Den Hartog (Citation2006) observed the prevailing of “judgments on the trustee’s integrity and benevolence, and the relatively marginalised status of the trustee’s competence and predictability” (p. 572), thereby calling for research that tests which components are critical under specific circumstances.

Once trustworthiness is established so that a party believes another to possess the quality to be trusted, s/he would be more willing to render her/himself vulnerable to the action of the trustee, and to trust.

Trustworthiness and performance

Emerging from the social relationship between parties, trust is positively associated with performance (Barney & Hansen, Citation1994; De Jong et al., Citation2015; Langfred, Citation2004; Porter & Lilly, Citation1996). In the sport context, organizational performance is understood as the achievement of an organization’s objectives which are considered multi-dimensional goals (Winand et al., Citation2010, Citation2013; Citation2014) and is mostly measured in terms of financial outcomes, sporting achievement, customer reach and satisfaction, social impact, management effectiveness, brand awareness and reputation (Boateng et al., Citation2016; Inglis et al., Citation2006; Plumley et al., Citation2017; Winand et al., Citation2010, Citation2014).

Performance is affected by trust and trustworthiness as it solves the uncertainty and vulnerability issues associated with social exchange relationships (De Jong & Elfring, Citation2010), so that individuals in a trusted relationship would engage in productive interaction by enhancing the performance of the organization. Distrust, on the other hand, would be associated with a non-willingness to collaborate so that parties would avoid the relationship to protect themselves from the potential vulnerability associated with the actions of non-trusted parties (Dirks & Ferrin, Citation2001).

Research on organizational trust has been undertaken on organizations that pursuit similar goals; that is, profit (see for example, Ashnai et al., Citation2016), but no research has looked at the influence of trust between organizational units driven by different objectives. More specifically, the founding company is oriented towards profit whereas its charity towards social outcomes (see ). In this organizational setting, however, arguably these objectives are intertwined and supporting each other (Anagnostopoulos & Winand, Citation2019). Through CSR activities the founding company can reduce cost, strengthen legitimacy, build up its reputation and competitive advantage and enhance value creation in the local community and beyond (Austin & Seitanidi, Citation2012; Babiak & Kihl, Citation2018). In return, income generated by the business can potentially allow further delivery of social activities by the charitable foundations (Kolyperas et al., Citation2016). Thus, CSR activities are assumed to benefiting the business of the PTSO and the foundation. Inevitably, trust is necessary for this mutually beneficial relationship. Employees from either organizational unit are affected by this reciprocal relationship (Anagnostopoulos et al., Citation2014).

Pivato et al.’s (Citation2008) study in the context of business-consumers relationships demonstrated that trust plays an important mediating role between CSR activities and company performance. Therefore, it can be argued that trustworthiness between employees from both the PTSO and the charitable foundation might explain the extent to which CSR activities carried out by the charitable foundations (e.g. their social performance) are perceived to benefit the PTSO, and hence to contribute to its overall performance, in terms of reputation and profit-making exercises. While the relationship between CSR and performance is extensively discussed and debated in the CSR and sport management literature, with contrasting findings revealing nonpositive effect on PSTOs (Inoue et al., Citation2011), the potential role of trust to increase performance should be demonstrated in the specific sporting industry (Godfey & Hatch, Citation2007). Furthermore, we suggest testing the effect trustworthiness might have on the perception that trustee’s activities contribute to the performance of the trustor’s organization.

Hypothesis: Trustworthiness of the employees in the charitable foundations influences the perceived contribution of CSR activities to the PTSOs’ performance.

Method

Research setting, sample and procedures

A clear research setting was of paramount importance given that CSR has been described as “vague and ambiguous, both in theory and in practice” (Coelho et al., Citation2003, p. 15). With this in mind, we test our hypotheses on charitable foundations and PTSOs using data from the UK’s football industry. Our choice of empirical setting is motivated by the clear context within which CSR unfolds. Professional football clubs in the UK are legally structured as limited liability companies owned by their shareholders and run by their directors (Morrow, Citation2013). These PTSOs, in turn, constitute the shareholders of the league associations who have the overall responsibility to implement a uniform management system for controlling these football clubs (for both sporting and non-sporting matters). One such non-sporting matter is mandating the funding allocation for CSR-related projects; funding that comes from the EPL’s lucrative television-rights deals (£4.8 bn for domestic rights alone, with an extra £100 for community projects for 2022–2025) that are collectively distributed to the football clubs. CSR-related funding, however, is restricted to the clubs’ (i.e. PTSOs’) charitable foundations, which, in turn, are not only subject to varying degrees of regulation (i.e. Charity Commission for England and Wales), but also accountable to football’s governing bodies (e.g. English and Scottish Premier Leagues, Football League). Thus, unlike mainstream corporate foundations that deal directly with the founding company, professional sport leagues largely mandate the implementation of CSR though central funding mechanisms. This context provides a quasi-natural laboratory (Babiak & Kihl, Citation2018) to examine the role of trust in inter-organizational collaborations for CSR implementation.

English Premier League and the Scottish Premier League’s clubs and their foundations are characterized by noteworthy similarities and differences in financial turnover, ownership structure, number and types of foundations, number and types of employees, types of governance and funding structure. Unlike the case of Premier League clubs which has taken a long-standing commitment to CSR through the Community Sports Trust model to implement CSR activities (see Walters & Panton, Citation2014), in one of the few studies that has analyzed Scottish Premier League CSR and their clubs (see for an example Hamil & Morrow, Citation2011), the authors state that only four clubs (Celtic, Grenta, Heart of Midlothian and Inverness Caledonian Thistle) had established separate foundations, trusts or companies to deliver all their clubs’ activities.

Participants targeted in the study were administrative or managerial employees from professional English or Scottish football clubs within one of the first three English divisions or the Scottish Premiership, consisting of a total of 80 football clubs. The absence of a reliable database of these employees (and whether they are top management, middle and, employees which influences their contribution to CSR implementation, see Maon et al., Citation2009) was a challenge overcome by retrieving contact details from official websites of football clubs and a professional online social network. A total of 648 email addresses of employees were collected.

A personal email invitation describing the purpose of the study was sent to each of those 648 employees with a link to a web-based survey created with Qualtrics online survey software. The survey remained open from 24 April 2014 until 1 July 2014. Three follow-up emails were sent to all non-respondents during the data collection period to increase the response rate. Participants’ identifying information was kept separate from survey responses to ensure anonymity and confidentiality. In addition, following Jordan et al.’s (Citation2011) recommendations, a second data collection stage was undertaken between 21 October and 30 November 2015 in order to eliminate the nonresponse error threat on the study’s external validity by comparing early to late respondents. An additional 70 new or late respondents answered the survey, which satisfied the recommended criterion of a minimum of 30 useable responses (Lindner et al., Citation2001). No difference between respondents from the first and second stage was detected for key variables such as components of trustworthiness and contribution to PTSO’s performance. It is thus anticipated that the non-response bias is reduced.

Among the 158 surveys returned, 34 were eliminated. Of those, 15 were incomplete, seven respondents mentioned their club had no charitable foundation, and 12 were not aware if they had. These respondents could not therefore provide reliable answers about a charitable foundation. The relevant sample was reduced to 124, which represents a response rate of 19.1 percent. Despite this medium sample, respondents had knowledge of their football club’s foundation, which is important for the reliability of data. Moreover, this sample size is deemed appropriate with regards to the number of variables investigated according to Wolf et al. (Citation2013). Among the completed questionnaires, 58 (46.8 percent) were from employees within English Premier league football clubs. Importantly, respondents represented 49 different football clubs (61.25 percent of the total number of clubs). On average 2.5 employees were surveyed per club (SD 2.02) with however 18 clubs with one employee participating to the survey.

presents the profile of respondents. Among the 124 respondents, 101 (81.5 percent) were male; 59 (47.6 percent) were under the age of 30, and 41 (33.1 percent) between 31 and 45. Sixty-three respondents (50.8 percent) held an undergraduate degree, and forty-three (34.7 percent) had up to one year of experience in their current role and thirty-seven (29.8 percent) had up to one year of experience in the same football club in which they have been surveyed. The top 3 functions of respondents were in marketing or events (44.4%); media and communication (19.4%) and CEO (9.7%).

Table 1. Profile of the respondents (N = 124).

Instrumentation

In line with the work of Dietz and Den Hartog (Citation2006), trustworthiness was measured through components of competence, benevolence, integrity, and predictability. These components were adapted according to the authors’ scales. Competence was measured by six items such as “I feel very confident about the skills of the charitable foundation employees”. Benevolence was measured through five items such as “I have very good relationships with employees at the charitable foundation”. Integrity was measured through four items such as “The charitable foundation openly shares information about future plans”. Predictability was measured through three items such as “All employees within the charitable foundation follow through with what they say”. A total of 18 items were used to measure components of trustworthiness. The perceived contribution of CSR activities implemented by the foundation to PTSO’s performance was also assessed through five exploratory items such as “The charitable foundation’s activities contribute towards the club’s goals” or “The charitable foundation contributes to the reputation of our club”. All components were measured through a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“I strongly disagree”) to 5 (“I strongly agree”). General performance measures were preferred to narrow measures such as “winning football games” or “making financial benefits”, as foundation activities would impact clubs’ overall performance, not the football team success or club’s financial profit which are not directly related to CSR activities. Moreover, the survey contained measures related to football clubs’ profile (division and size) and respondents’ demographic variables (age, gender, and education), and employees’ previous experience in their current role and in their organization.

Data analysis and measurement tests

A scale for trustworthiness is measured with four main components including competence, benevolence, integrity, and predictability. The particular components were tested for internal consistency by Cronbach’s alpha and deemed acceptable when superior to .60 (Cortina, Citation1993). The respective values of Cronbach’s alpha were .78 for competence, .77 for benevolence, .71 for integrity, and .79 for predictability. The Cronbach’s alpha for contribution to PTSO’s performance was .68. These results confirm that the above measures meet the criterion for internal reliability. Correlational relationship has been used to explore relations between variables under study. Multiple linear regression is used to explain under control variables employees’ perceptions that foundation work contributes to their PTSO performance by foundation employees trustworthiness. Finally, the two-step approach recommended by Anderson and Gerbing (Citation1988) was employed to test the main hypothesis of the study using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), using SPSS AMOS 21.

Results

The four components of trustworthiness (i.e. competence, benevolence, integrity, and predictability) were estimated simultaneously with the construct of perceived contribution to PTSO’s performance. Each of the set of items was constrained to load on the respective construct. The measurement model fit was evaluated based on the following fit indices: chi-square statistic (χ2), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and according to threshold recommended by Hu and Bentler (Citation1999). The initial goodness-of-fit statistics indicated an inadequate model fit with a few items with factor loadings below .40. Five items had to be deleted because of low loadings and the model was tested again. The modified model contained five constructs with 18 items and the overall fit indices of the measurement model were (χ2 = 213,511 CFI = .91; IFI = .92, RMSEA = .08 and SRMR = .070) and met the cut-off values recommended by Hu and Bentler (Citation1998). This evidence showed an overall good model fit to the data, allowing the next step of the analysis.

presents three types of reliability including standardized factor loadings for each indicator per construct, overall scale composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE). Standardized factor loadings were found all statistically significant at p < .001 and above .50, while the majority of the factor loadings were above .70, confirming the posited link between the items and the constructs and providing satisfactory evidence of convergent validity. Furthermore, the CR values of four of the five constructs in the model were above .70 meeting the threshold recommended by Hair et al. (Citation1998) and in the case of integrity were greater than 0.6 meeting the lower criterion set by Tseng et al. (Citation2006). The estimates for AVE for each construct was higher than .50 (Hair et al., Citation1998) with the exception of competence, suggesting that the latent constructs are adequately represented by the selected indications.

Table 2. Measurement properties for the constructs.

Assessing discriminant validity was conducted following the method of Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981). We compared the shared variance (i.e. squared correlation) between each pair of constructs in the model with the AVEs for these constructs, with each AVE estimate to be higher than the squared correlation between two constructs. shows that the AVEs of all constructs in the model were higher than any of the squared inter-correlations between the respective constructs offering evidence of discriminant validity.

Regarding descriptive statistics, results indicate that, on average and overall, employees within football clubs perceive their counterparts in the foundation as being trustworthy (Mean = 4.22; SD = .51). Regarding each component of trustworthiness, results indicate high rating for levels of competence (5 items, Mean = 4.28; SD = .52), benevolence (4 items, Mean = 4.30; SD = .58), integrity (3 items, Mean = 4.24; SD = .57), and predictability (3 items, Mean = 4.07; SD = .66). Football club employees perceived charitable foundations contribute significantly towards their club performance (3 items, Mean = 4.59; SD = .49) by enhancing the club’s reputation and goals, and offering valuable services to the community through the charitable foundation’s activities.

Analysis of the relationship between variables () shows that components of trustworthiness and perceived contribution to PTSO’s performance are all significantly positively correlated with coefficients ranging from .43 to .80 (p < .001). This finding indicates that trustworthiness components are important factors in the perceived contribution of the charitable foundation’s CSR activities to the PTSO’s performance.

Table 3. Means and standard deviations and correlation between components.

Regression analysis shows that 33 percent of the variance in foundation’s contribution to PTSO’s performance is explained by trustworthiness (β = .60, p < .001) (, model 3). Under control variables, perceptions by the football clubs’ employees that foundation’s CSR activities contribute to the PTSO’s performance is partially explained by the trustworthiness of charitable foundation employees. Furthermore, when examining components of trustworthiness (, model 3bis), results show that competence (β = .30, p < .05) and predictability (β = .31, p < .05) significantly explain 37 percent of the variance in contribution to PTSO’s performance, with benevolence and integrity being non-significant. Another interesting finding emerging from regression analysis is the significance of the level of experience in the organization by PTSO employees which partially explains perceived contribution to performance (, models 1 and 2).

Table 4. Hierarchical multiple regression predicting contribution to PTSO’s performance from trustworthiness and its components.

describes the tested hypothesis which explores the relationships among trustworthiness and contribution to PTSO’s performance. The SEM analysis of the particular model showed satisfactory fit indices (Hu & Bentler, Citation1998). The chi-square (x2) value was 15.43, with df = 10, and Cmin/DF = 1.54; the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) was .98, the Incremental Fit Indice (IFI) was .98 and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was .06. These results showed that trustworthiness has a significant and positive impact on contribution to PTSO’s performance (β = .71, p < .001), and it offers support for the main hypothesis. The particular model with the four trustworthiness components explains a large portion of the variance (51%) of contribution to PTSO’s performance.

Discussion

The study aimed to answer three research questions. In light of the first one (do PTSOs employees perceive their counterparts in the charitable foundation to be trustworthy?), the conditions that surround the relationship between PTSOs and their charitable foundations may influence the quality of the relationship and how they view each other (Lewicki & Bunker, Citation1996). Previous research (e.g. Ariño et al., Citation2001; Rousseau et al., Citation1998) puts forward that contextual variables, previous experience, attributed intentions, perceived success (or failure) of activities all condition the trust relationship. Within the present research, the local community engagement of employees from either entity (Babiak & Kihl, Citation2018), the shared passion for a similar activity (Anagnostopoulos et al., Citation2016), as well as the perceived success of CSR activities and shared experience (Kolyperas et al., Citation2016) may have played a role in strengthening the level of trustworthiness between employees. This supports the “linked interests” which, according to Austin and Seitanidi (Citation2012), offer incentives for greater close collaboration. Indeed, the common desire to create social good is a key driver for sport organizations when collaborating for CSR (Zeimers et al., Citation2019b).

Without the assumed and reciprocal trust, the risk would be important to deteriorate the relationship (Molm, Citation1994; Molm et al., Citation2007). Trust between parties play a key role in the successful relationship (Schoenherr et al., Citation2015), and this is no different in the present organizational context. In this study, the proximity of each trustor and trustee who both work in a local community environment (even though the PTSO may be internationally known) might reinforce their inter-organizational relationship, as they are frequently working together in CSR activities for the local community. As underlined by previous research (Molm et al., Citation2007), they might be less likely to exploit one another given the close and repetitive relationships, which would lead to higher level of trust. Tenure in the PTSO might consequently allow the development or strengthening of trust, and particularly permit a longer time to assess someone’s trustworthiness under different situations. This is shown in the present study by the significant result for the level of experience of PTSOs’ employees in their organization which partially explains they perceive charitable foundation contributes to their PTSO’s performance but becomes non-significant when trustworthiness is added to the model.

Considering the second research question (do PTSOs employees perceive charitable foundation activities contribute to the performance of the PTSO?) the present study demonstrates that foundation employees undertake tasks that are of significance to PTSOs’ employees and their organization. Programs implemented by foundation employees seemed to be of significance to PTSOs and their employees, which supports Molteni and Pedrini (Citation2010) assumption that CSR programs are perceived to contribute both to social and business performance. Furthermore, in accordance with the reciprocity principle within SET (Blau, Citation1964; Lioukas & Reuer, Citation2015; Molm et al., Citation2007), the contribution that foundation employees make to the performance of the PTSO itself through undertaking CSR activities represents benefits perceived by PTSOs’ employees. These benefits are contributing to the reputation of the PTSO, to the achievement of the PTSO’s goals, and providing services to the community with positive impact. However, while the benefits received from charitable foundations to PTSOs appear evident, it is not clear what the latter receive in exchange. Supposedly, charitable foundation would also trust PTSOs’ employees and benefit from the success of the PTSO itself and the image, brand, and on pitch performance of the PTSO to deliver its CSR activities.

The level of trustworthiness of the trustee perceived by trustor (third research question – does trustworthiness predict the perception that charitable foundation’s activities contribute to the performance of the PTSO?) explains the extent to which the former contributes to the latter’s perceived organization performance. Trustworthiness is hence a strong predictor of the perception that foundation’s activities contribute to the performance of the PTSO (Anagnostopoulos & Winand, Citation2019). Trust has been shown to affect performance through solving uncertainty and vulnerability issue associated with social exchange relationships (De Jong & Elfring, Citation2010). Therefore, the PTSO’s employees would engage in productive relationships with foundation employees that they trust for the delivery of CSR activities benefiting the PTSO itself. From the four components of trustworthiness, competence and predictability were the two significant determinants that explain in this specific collaborative context why PTSOs’ employees perceived their counterparts at the foundations to contribute the PTSOs’ performance. These findings demonstrate the critical influence of competence and predictability in the research on the trust-performance relationships that has been largely disregarded in the trust literature (Dietz & Den Hartog, Citation2006). Competence and predictability are related to performance while benevolence and integrity are more related to how it is achieved, respecting principles, values and ethics. Competence is an assurance that performance can be achieved by the individuals whose responsibility has been given to achieve it while predictability is a perception that can be done within the required timeframe and level needed.

Theoretical implications

The relationship between PTSOs and charitable foundations has been the focus of research in the CSR literature (Minciullo & Pedrini, Citation2015; Pedrini & Minciullo, Citation2011). The present study adds to the CSR and inter-organizational relationships literature by demonstrating the importance of trustworthiness between founding PTSOs and their charitable foundation. Although the goals that underpin their work are different – charitable versus commercial – foundation employees are perceived to be trustworthy by PTSOs’ employees maybe because their overall organizational mission is not that different. While CSR activities lead to positive perceived trustworthiness (Lin-Hi et al., Citation2015; Van Herpen et al., Citation2003), this paper suggests this is also the case with entities driven by different goals. It shows that founding PTSO employees directly value the work of charitable employees and consider it supportive for the PTSO’s success.

Furthermore, this study contributes to identify trustworthiness as a key element of successful inter-organizational relationships (Atouba & Shumate, Citation2020; Babiak et al., Citation2018; Babiak & Thibault, Citation2008). In particular, the study shows that perceived competence and predictability are among the most important qualities of the charitable foundations in explaining the perceived contribution to the success of the “mother” football club. This finding expands Bryson et al.’s (Citation2015) assumption that partners build trust by sharing resources (e.g. information) and demonstrating competency, good intentions, and follow-through (Chen, Citation2010).

Practical implications

Practical implications can be drawn from the results and should take into considerations differences in between each league and club (e.g. in terms of CSR mode of implementation, financial turnover, national policy context, and funding structure). First, reinforcing trust relationship between employees is critical even though they have different agendas. Managers should facilitate trustworthy behaviors between PTSOs’ employees and their counterparts in the foundations, which would lead to mutual trust. This may also be the case between employees from distinct departments or entities with the same organizational setting but with different organizational motives. Second, the practice of CSR is valued by employees of the PTSO and those within charitable foundations are also valued and deemed trustworthy by the former. Managers could increase trustworthiness by competence and predictability. This involves developing competent foundation staff through the provision of training in the tasks they have been assigned to ensure that they are able to do the ask efficiently (task delivery). Predictability can be improved by means of a positive work environment encouraging open communication among employees, social skills coaching and related trust measurement or trust building tools. CSR activities implemented by the foundation should be openly and internally communicated to founding PTSO’s employees as the latter consider these activities to influence the achievement of business’s performance. Increased knowledge and communication about the success of CSR activities as well as enhanced collaborative behaviors and involvement would reinforce social work relationships. Third, the level of trustworthiness contributes to increased recognition that CSR activities contribute to the PTSO’s success. Therefore, the aforementioned recommendations are connected and reinforcing trustworthiness would ultimately strengthen the perceptions that charitable foundations implementing CSR activities contribute to the PTSOs’ performance.

Limitations and Further research directions

One limitation is the particular and challenging study context for inviting individuals to participate in the study. The number of potential professional football clubs that can participate in the study is limited as are the number of clubs’ employees. The study also collected answers from a significant proportion of employees with up to one year of experience in the clubs surveyed. While this may reflect the employment context in football, it may have influenced the results given that trust and experience are certainly related. Despite these constraints, the study collected the view of a significant number of employees for most UK football clubs. Thus, ongoing CSR studies should further validate these results on larger samples associated with football foundations in other countries, other sport-related foundations or other CSR implementation modes like collaborations.

We also acknowledge the same-source biased and self-reporting bias which may have influenced the results, as well as the potential social desirability and self-selection bias in the study sample. To reduce the impact of those biases, we have used multiple and original techniques to recruiting as many participants as possible through various means described in the method section. We made participants aware the study guaranteed their anonymity and that they or their clubs would not benefit in any way from the survey results. Furthermore, non-knowledgeable employees were removed from the sample to only keep those that were aware of the existence of a charitable foundation for their PTSO. Nonetheless, similar research looking at inter-organizational trust in another organizational context could be conducted to identify differences with the present study in the context of professional sport. Future research could also integrate a broader perspective of trust, not limited to trustworthiness, and measure the intention to trust and the act of trust, the latter of which represents, according to Hassell (Citation2005) the only true evidence for trust.

Two components of trustworthiness appeared to have a critical importance; that is, competence and predictability. Further research could analyze these components with more details and their influence within the trust spectrum from low to high level of trust. Some areas of competence that are critical in developing trust relationships might also be of interest.

While this study measured trustworthiness of charitable foundation employees as perceived by PTSO employees, further research could measure the reciprocal relationships between PTSO and foundations, or any other parties involved in the relationships (e.g. community members/fans/customers or sponsors/donators). The question that arises would be whether charitable foundation employees trust their counterparts in the founding PTSO as much as they are trusted? This follow-up study could identify the types and the number of employees within foundations and difference in interpersonal trust. In the same vein as this paper, the mutual benefits charitable foundations and PTSOs receive in exchange would need to be explored. Further measures of PTSO performance and successful CSR activities could also be employed to deepen the analysis of the trust relationships between these entities, and their particular impact of specific performance measures.

Conclusion

This research offers empirical insights on the way employees in founding PTSOs perceive CSR activities carried out by their charitable foundation and the employees thereof. It contributes to the ever-expanding literature examining CSR implementation in collaborative implementation mode (see, Husted, Citation2003) where PTSOs establish independent charitable foundations. The study shows that PTSO employees deemed foundation CSR activities contribute to the success of their organization, and that this can be explained by the level of trustworthiness of foundation employees as perceived by the PTSO’s employees. This is the first study to demonstrate the importance of trustworthiness in the relationships between employees from organizational entities driven by different goals.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Community trusts, foundations and community education and sporting trusts are used interchangeably (Walters & Panton, Citation2014).

References

- Anagnostopoulos, C. (2013). Getting the tactics right: Implementing CSR in English football. In J. L. Paramio, K. Babiak, & G. Walters (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of sport and corporate social responsibility (pp. 91–104). Routledge.

- Anagnostopoulos, C., Byers, T., & Kolyperas, D. (2017). Understanding strategic decision-making through a multi-paradigm perspective: The case of charitable foundations in English football. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 7(1), 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-02-2016-0005

- Anagnostopoulos, C., Byers, T., & Shilbury, D. (2014). Corporate social responsibility in team sport organisations: Toward a theory of decision-making. European Sport Management Quarterly, 14(3), 259–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2014.897736

- Anagnostopoulos, C., & Shilbury, D. (2013). Implementing corporate social responsibility in English football: Towards multi-theoretical integration. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 3(4), 268–284. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-05-2013-0009

- Anagnostopoulos, C., & Winand, M. (2019). Board-executive relationship in team sport charitable foundations: Unpacking trust building through ‘exchange currencies’. In C. Anagnostopoulos & M. Winand (Eds.), Research Handbook on sport governance (pp. 236–255). Edward Elgar.

- Anagnostopoulos, C., Winand, M., & Papadimitriou, D. (2016). Passion in the workplace: Empirical insights from team sport organisations. European Sport Management Quarterly, 16(4), 385–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2016.1178794

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Anheier, H. K. (2001). Foundations in Europe: A comparative perspective (No. 18). Centre for civil society, London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Ariño, A., De la Torre, J., & Ring, P. S. (2001). Relational quality: Managing trust in corporate alliances. California Management Review, 44(1), 109–131. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166113

- Arino, A., De La Torre, J., & Ring, P. S. (2005). Relational quality and inter-personal trust in strategic alliances. European Management Review, 2(1), 15–27.

- Ashnai, B., Henneberg, C. S., Naudé, P., & Francescucci, A. (2016). Inter-personal and inter-organizational trust in business relationships: An attitude–behavior–outcome model. Industrial Marketing Management, 52, 128–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.05.020

- Atouba, Y. C., & Shumate, M. D. (2020). Meeting the challenge of effectiveness in nonprofit partnerships: Examining the roles of partner selection, trust, and communication. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 31(2), 301–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-019-00143-2

- Austin, J. E., & Seitanidi, M. M. (2012). Collaborative value creation: A review of partnering between nonprofits and businesses: Part I. Value creation spectrum and collaboration stages. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(5), 726–758. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764012450777

- Babiak, K., & Kihl, L. (2018). A case study of stakeholder dialogue in professional sport: An example of CSR engagement. Business and Society Review, 123(1), 119–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/basr.12137

- Babiak, K., & Thibault, L. (2008). Managing inter-organisational relationships: The art of plate spinning. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, 3(3), 281–302. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSMM.2008.017193

- Babiak, K., Thibault, L., & Willem, A. (2018). Mapping research on interorganizational relationships in sport management: Current landscape and future research prospects. Journal of Sport Management, 32(3), 272–294. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2017-0099

- Babiak, K., & Wolfe, R. (2009). Determinants of corporate social responsibility in professional sport: Internal and external factors. Journal of Sport Management, 23(6), 717–742. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.23.6.717

- Barney, J. B., & Hansen, M. H. (1994). Trustworthiness as a source of competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 15(S1), 175–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250150912

- Bingham, T., & Walters, G. (2013). Financial sustainability within UK charities: Community sport trusts and corporate social responsibility partnerships. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 24(3), 606–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-012-9275-z

- Blau, P. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. John Wiley and Sons.

- Boateng, A., Akamavi, R. K., & Ndoro, G. (2016). Measuring performance of non-profit organisations: Evidence from large charities. Business Ethics: A European Review, 25(1), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12108

- Bryson, J. M., Crosby, B. C., & Stone, M. M. (2006). The design and implementation of cross-Sector collaborations: Propositions from the literature. Public Administration Review, 66(s1), 44–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00665.x

- Bryson, J. M., Crosby, B. C., & Stone, M. M. (2015). Designing and implementing cross-sector collaborations: Needed and challenging. Public Administration Review, 75(5), 647–663. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12432

- Chen, B. (2010). Antecedents or processes? Determinants of perceived effectiveness of interorganizational collaborations for public service delivery. International Public Management Journal, 13(4), 381–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2010.524836

- Cobourn, S., & Frawley, S. (2017). CSR in professional sport: An examination of community models. Managing Sport and Leisure, 22(2), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2017.1402694

- Coelho, P. R., McClure, J. E., & Spry, J. A. (2003). The social responsibility of corporate management: A classical critique. American Journal of Business, 18(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/19355181200300001

- Cook, K. S., Cheshire, C., Rice, E. R., & Nakagawa, S. (2013). Social exchange theory. In J. Delamater & A. Ward (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (pp. 61–88). Springer.

- Cortina, J. M. (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(1), 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.98

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602

- Cunningham, J. B., & McGregor, J. (2000). Trust and the design of work: Complementary constructs in satisfaction and performance. Human Relations, 53(192), 1575–1591. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267005312003

- Das, T. K., & Teng, B. S. (1998). Between trust and control: Developing confidence in partner cooperation in alliances. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 491–512. https://doi.org/10.2307/259291

- De Jong, B. A., Dirks, K. T., & Gillespie, N. (2015). Trust and team performance: A meta-analysis of main effects, contingencies, and qualifiers. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2015(1), 14561. Academy of Management. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2015.234

- De Jong, B. A., & Elfring, T. (2010). How does trust affect the performance of ongoing teams? The mediating role of reflexivity, monitoring, and effort. Academy of Management Journal, 53(3), 535–549. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.51468649

- Dietz, G., & Den Hartog, D. N. (2006). Measuring trust inside organisations. Personnel Review, 35(5), 557–588. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480610682299

- Dirks, K. T., & Ferrin, D. L. (2001). The role of trust in organizational settings. Organization Science, 12(4), 450–467. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.12.4.450.10640

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313

- Godfey, P. C., & Hatch, N. W. (2007). Researching corporate social responsibility: An agenda for the 21st century. Journal of Business Ethics, 70(1), 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9080-y

- Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis. Englewood cliff. New Jersey, USA, 5(3), 207–2019.

- Hamil, S., & Morrow, S. (2011). Corporate social responsibility in the Scottish Premier League: Context and motivation. European Sport Management Quarterly, 11(2), 143–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2011.559136

- Hardy, C., Phillips, N., & Lawrence, T. B. (2003). Resource knowledge and influence: The organizational effects of interorganizational collaboration. Journal of Management Studies, 40(2), 321–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00342

- Hassell, L. (2005). Affect and trust. In P. Herrmann, V. Issarny, & S. Shiu (Eds.), Trust management (pp. 131–145). Springer.

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424–453. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424

- Husted, B. (2003). Governance choices for corporate social responsibility: To contribute, collaborate or internalize. Long Range Planning, 36(5), 481–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-6301(03)00115-8

- Huxham, C., & Vangen, S. (1996). Working together: Key themes in the management of relationships between public and non-profit organizations. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 9(7), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513559610153863

- Inglis, R., Morley, C., & Sammut, P. (2006). Corporate reputation and organisational performance: An Australian study. Managerial Auditing Journal, 21(9), 934–947. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686900610705028

- Inkpen, A. C., & Currall, S. C. (2004). The coevolution of trust, control, and learning in joint ventures. Organization Science, 15(5), 586–599. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1040.0079

- Inoue, Y., Kent, A., & Lee, S. (2011). CSR and the bottom line: Analyzing the link between CSR and financial performance for professional teams. Journal of Sport Management, 25(6), 531–549. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.25.6.531

- Jamali, D., Yianni, M., & Abdallah, H. (2011). Strategic partnerships, social capital and innovation: Accounting for social alliance innovation. Business Ethics: A European Review, 20(4), 375–391. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8608.2011.01621.x

- Jordan, J. S., Walker, M., Kent, A., & Inoue, Y. (2011). The frequency of nonresponse analyses in the journal of sport management. Journal of Sport Management, 25(3), 229–239. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.25.3.229

- Kihl, L., Babiak, K., & Tainsky, S. (2014). Evaluating the implementation of a professional sport team’s corporate community involvement initiative. Journal of Sport Management, 28(3), 324–337. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2012-0258

- Kolyperas, D., Anagnostopoulos, C., Chadwick, S., & Sparks, L. (2016). Applying a communicating vessels framework to CSR value co-creation: Empirical evidence from professional team sport organizations. Journal of Sport Management, 30(6), 702–719. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2016-0032

- Langfred, C. W. (2004). Too much of a good thing? Negative effects of high trust and individual autonomy in self-managing teams. Academy of Management Journal, 47(3), 385–399.

- Lee, H. W., Robertson, P. J., Lewis, L., Sloane, D., Galloway-Gilliam, L., & Nomachi, J. (2012). Trust in a cross-sectoral interorganizational network: An empirical investigation of antecedents. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(4), 609–631. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764011414435

- Lefebvre, A., Zeimers, G., & Zintz, T. (2021). Local sport club presidents’ perceptions of collaboration with sport federations. Managing Sport and Leisure. Advanced Publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2021.1928536

- Lewicki, R. J., & Bunker, B. B. (1996). Developing and maintaining trust in work relationships. In R. Kramer & T. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in organizations: Frontiers of theory and research (pp. 133–173). Sage.

- Lindner, J. R., Murphy, T. H., & Briers, G. H. (2001). Handling nonresponse in social science research. Journal of Agricultural Education, 42(4), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2001.04043

- Lin-Hi, N., Hörisch, J., & Blumberg, I. (2015). Does CSR matter for nonprofit organizations? Testing the link between CSR performance and trustworthiness in the nonprofit versus for-profit domain. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 26(5), 1944–1974. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-014-9506-6

- Lioukas, C. S., & Reuer, J. J. (2015). Isolating trust outcomes from exchange relationships: Social exchange and learning benefits of prior ties in alliances. Academy of Management Journal, 58(6), 1826–1847. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0934

- Maon, F., Lindgreen, A., & Swaen, V. (2009). Designing and implementing corporate social responsibility: An integrative framework grounded in theory and practice. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(1), 71–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9804-2

- Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, D. F. (1995). An integrative model of organisational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734. https://doi.org/10.2307/258792

- Minciullo, M., & Pedrini, M. (2015). Knowledge transfer between for-profit corporations and their corporate foundations: Which methods are effective? Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 25(3), 215–234. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21125

- Minefee, I., Neuman, E. J., Isserman, N., & Leblebici, H. (2015). Corporate foundations and their governance: Unexplored territory in the corporate social responsibility agenda. Annals in Social Responsibility, 1(1), 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1108/ASR-12-2014-0005

- Mishra, A. K. (1996). Organizational responses to crisis. In R. M. Kramer & T. R. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in organizations. (pp. 261–287). Sage.

- Molm, D. L., Takahashi, N., & Peterson, G. (2000). Risk and trust in social exchange: An experimental test of a classical proposition. American Journal of Sociology, 105(5), 1396–1427. https://doi.org/10.1086/210434

- Molm, L. D. (1994). Dependence and risk: Transforming the structure of social exchange. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57(3), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.2307/2786874

- Molm, L. D., Collett, J. L., & Schaefer, D. R. (2007). Building solidarity through generalized exchange: A theory of reciprocity. American Journal of Sociology, 113(1), 205–242. https://doi.org/10.1086/517900

- Molteni, M., & Pedrini, M. (2010). In search of socio-economic syntheses. Journal of Management Development, 29(7/8), 626–636. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621711011059059

- Morrow, S. (2013). Football club financial reporting: Time for a new model? Sport, Business, and Management: An International Journal, 3(4), 297–311. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-06-2013-0014

- O’Boyle, I., & Shilbury, D. (2016). Exploring issues of trust in collaborative sport governance. Journal of Sport Management, 30(1), 52–69. https://doi.org/10.1123/JSM.2015-0175

- Pedrini, M., & Minciullo, M. (2011). Italian corporate foundations and the challenge of multiple stakeholder interests. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 22(2), 173–197. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.20048

- Pivato, S., Misani, N., & Tencati, A. (2008). The impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer trust: The case of organic food. Business Ethics: A European Review, 17(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8608.2008.00515.x

- Plumley, D., Wilson, R., & Ramchandani, G. (2017). Towards a model for measuring holistic performance of professional football clubs. Soccer & Society, 18(1), 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2014.980737

- Porter, T. W., & Lilly, B. S. (1996). The effects of conflict, trust, and task commitment on project team performance. International Journal of Conflict Management, 7(4), 361–376. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb022787

- Ring, P. S. (1996). Fragile and resilient trust and their roles in economic exchange. Business & Society, 35(2), 148–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/000765039603500202

- Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 393–404. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1998.926617

- Rowe, K., Karg, A., & Sherry, E. (2019). Community-oriented practice: Examining corporate social responsibility and development activities in professional sport. Sport Management Review, 22(3), 363–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.05.001

- Sanders, A., Keech, M., Burdsey, D., Maras, P., & Moon, A. (2021). CEO perspectives on the first twenty-five years of football in the community: Challenges, developments and opportunities. Managing Sport and Leisure, 26(1-2), 7–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1771198

- Schoenherr, T., Narayanan, S., & Narasimhan, R. (2015). Trust formation in outsourcing relationships: A social exchange theoretic perspective. International Journal of Production Economics, 169, 401–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2015.08.026

- Selsky, J. W., & Parker, B. (2005). Cross-sector partnerships to address social issues: Challenges to theory and practice. Journal of Management, 31(6), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279601

- Sharp, E. A., Thwaites, R., Curtis, A., & Millar, J. (2013). Trust and trustworthiness: Conceptual distinctions and their implications for natural resources management. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 56(8), 1246–1265. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2012.717052

- Sia, S. K., Koh, C., & Tan, C. X. (2008). Strategic maneuvers for outsourcing flexibility: An empirical assessment. Decision Sciences, 39(3), 407–443. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.2008.00198.x

- Smith, A. C., & Westerbeek, H. M. (2007). Sport as a vehicle for deploying corporate social responsibility. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 25(1), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.9774/GLEAF.4700.2007.sp.00007

- Spence, L. J. (2016). Small business social responsibility: Expanding core CSR theory. Business & Society, 55(1), 23–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650314523256

- Takos, N., Murray, D., & O’Boyle, I. (2018). Authentic leadership in nonprofit sport organization boards. Journal of Sport Management, 32(2), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2017-0282

- Thomas, B. (2018, 30 November). Key points for sports organisations on the use of charitable foundations. LawinSport. https://www.lawinsport.com/topics/item/key-points-for-sports-organisations-on-the-use-of-charitable-foundations

- Tseng, W. T., Dörnyei, Z., & Schmitt, N. (2006). A new approach to assessing strategic learning: The case of self-regulation in vocabulary acquisition. Applied Linguistics, 27(1), 78–102. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/ami046

- Vangen, S., & Huxham, C. (2003). Nurturing collaborative relations: Building trust in interorganizational collaboration. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 39(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886303039001001

- Van Herpen, E., Pennings, J. M., & Meulenberg, M. T. (2003). Consumers’ evaluations of socially responsible activities in retailing (No. MWP-04). Lsg Marktkunde en Consumentengedrag.

- Walker, M., & Parent, M. M. (2010). Toward an integrated framework of corporate social responsibility, responsiveness, and citizenship in sport. Sport Management Review, 13(3), 198–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2010.03.003

- Walters, G., & Anagnostopoulos, C. (2012). Implementing corporate social responsibility through social partnerships. Business Ethics: A European Review, 21(4), 417–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8608.2012.01660.x

- Walters, G., & Chadwick, S. (2009). Corporate citizenship in football: Delivering strategic benefits through stakeholder engagement. Management Decision, 47(1), 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740910929696

- Walters, G., & Panton, M. (2014). Corporate social responsibility and social partnerships in professional football. Soccer & Society, 15(6), 828–846. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2014.920621

- Walters, G., & Tacon, R. (2010). Corporate social responsibility in sport: Stakeholder management in the UK football industry. Journal of Management & Organization, 16(4), 566–586. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1833367200001942

- Walzel, S., Robertson, J., & Anagnostopoulos, C. (2018). Corporate social responsibility in professional team sports organizations: An integrative review. Journal of Sport Management, 32(6), 511–530. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2017-0227

- Winand, M., Rihoux, B., Robinson, L., & Zintz, T. (2013). Pathways to high performance: A qualitative comparative analysis of sport governing bodies. Non-Profit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 42(4), 739–762. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764012443312

- Winand, M., Vos, S., Claessens, M., Thibaut, E., & Scheerder, J. (2014). A unified model of non-profit sport organizations performance: Perspectives from the literature. Managing Leisure, 19(2), 121–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/13606719.2013.859460

- Winand, M., Zintz, T., Bayle, E., & Robinson, L. (2010). Organizational performance of Olympic sport governing bodies. Dealing with measurement and priorities. Managing Leisure, 15(4), 279–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/13606719.2010.508672

- Wolf, E. J., Harrington, K. M., Clark, S. L., & Miller, M. W. (2013). Sample size requirements for structural equation models: An evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 73(6), 913–934. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164413495237

- Zeimers, G., Anagnostopoulos, C., Zintz, T., & Willem, A. (2019a). Corporate social responsibility (CSR) in football: Exploring modes of CSR implementation. In S. Chadwick, D. Parnell, P. Widdop, & C. Anagnostopoulos (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of football business and management (pp. 114–130). Routledge.

- Zeimers, G., Anagnostopoulos, C., Zintz, T., & Willem, A. (2019b). Unpacking collaboration among nonprofit organizations for social responsibility programs. Non-profit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 48(5), 953–974. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764019837616

- Zeimers, G., Lefebvre, A., Winand, M., Anagnostopoulos, C., Zintz, T., & Willem, A. (2020). Organisational factors of corporate social responsibility implementation: A qualitative comparative analysis of sport federations. European Sport Management Quarterly, 21(2), 173–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2020.1731838