ABSTRACT

Rationale Sport is increasingly seen as a vehicle through which to address and prevent the high prevalence of violence against women, yet it is also a site for interpersonal gender-based violence. This paper scopes recent empirical research to examine the focus of research into interpersonal gender-based violence against adult women in sport and what sports organisations are doing to respond and prevent such violence. The paper then sets out potential areas for future sport management research.

Design Following Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review framework, we conducted a comprehensive search of published literature since 2000 across 14 databases.

Findings: We identified 15 papers. Findings are presented as a numerical summary and thematic analysis. The numerical summary reveals a lack of studies examining sport organisations’ responses to interpersonal gender-based violence against adult women participating in sport. The thematic analysis shows dominance of sexual violence often within the coach–athlete relationship, a focus on prevalence, and lack of theoretical underpinning.

Practical implications: If sport is to continue being used as a vehicle to prevent violence against women in society more broadly, future research must address all forms of interpersonal gender-based violence against women that may be occurring in sport and examine how sport organisations are addressing such violence.

Research contribution: This paper shows a significant gap in research on adult women experiencing interpersonal gender-based violence in sport, and responses to such violence. It provides a foundation from which to drive future research.

Introduction

In some sports’ cultures sport and violence are often perceived as synonymous terms, whether it be in reference to sanctioned violence of competitive contact sports, an expectation of performance, or “unsanctioned aggression and violence” (Kerr, Citation2005; Spaaij & Schaillée, Citation2019, p. 36). Spaaij and Schaillée (Citation2019) argue “while unsanctioned aggression and violence in amateur sport are most visible and most felt at the individual and interpersonal level, their causes are embedded within social networks and cultural norms within and beyond sports environments” (p. 44). Such culturally embedded violence in sport has long been connected with hegemonic masculinity (Messner, Citation1992). Sport is perceived, and athletic male’s positions within male-dominated sports are perceived, as highly masculinised, where players see themselves as “one of the boys” and unlikely to speak up against peers in relation to violence (Corboz et al., Citation2016, p. 335). Athlete populations are more likely to be violent than non-athlete populations, with the connection between masculinity and violence being made across certain sports (Sønderlund et al., Citation2014). Flood and colleagues, have argued the connections between sport, hegemonic masculinity, and violence against women (Flood, Citation2008; Flood & Dyson, Citation2006). Flood and Dyson (Citation2006, p. 12) argue that “sporting sub-cultures” involve sexist gender norms and are more likely to have violence-supporting attitudes. Also, within male sport cultures “male bonding feeds sexual violence against women and sexual violence against women feeds male bonding” (Flood, Citation2008, p. 50), underpinned by “homosocial codes of silence” in male team sports (Corboz et al., Citation2016, p. 337). Violence-supporting attitudes, sexist gender stereotyping and dominant forms of masculinity are all accepted drivers of violence against women (Our Watch, Citation2021). Yet sport is also recognised as a priority setting, amongst many others, for the delivery of primary prevention activities to reduce violence against women in society more broadly (Liston et al., Citation2017; Our Watch et al., Citation2015; Our Watch, Citation2021).

Given the connection between sport, hegemonic masculinity, and violence against women, the purpose of our review was to scope research that looks at interpersonal gender-based violence against adult women who participate in sport, by men. In the next section, we first provide background on violence against women, as well as sports’ role to date in violence prevention, before detailing the specific aim and method of the review.

Violence against women

Violence against women is most often committed by men (World Health Organization, Citation2021). The United Nations defines violence against women as

any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life. (Articles One and Two of the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women – Proclaimed by General Assembly resolution 48/104 of 20 December 1993)

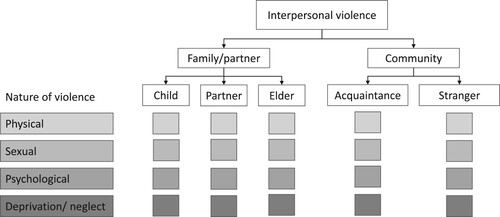

Figure 1. Typology of gender-based interpersonal violence (adapted from World Health Organization, Citation2002).

Sport: a vehicle for primary prevention in a context of gender inequality

Sport has been recognised as a priority setting, amongst many others, for the delivery of primary prevention of violence against women and girls’ activities (Liston et al., Citation2017; Our Watch, Citation2021; Our Watch et al., Citation2015), and much of the existing work on gender-based violence in sport specifically has focused on prevention activities (Mergaert et al., Citation2016). Primary prevention of violence against women is concerned with stopping violence before it occurs (Krug et al., Citation2002). Primary prevention activities target the drivers and reinforcing factors of violence against women such as, amongst others, gender inequality, rigid gender roles and stereotypes (including sexist jokes), and male interactions that support aggression or disrespect of women (Our Watch, Citation2021; Our Watch et al., Citation2015). Sport for development programmes are often heralded as the format through which to deliver such primary prevention activities for the broader population (Miller et al., Citation2012), yet this focus often ignores or downplays the embedded gender inequality and sexist attitudes that are ingrained within sport and experienced by athletes, administrators, officials, and perpetuated by the media and marketing (Clark, Citation2017; Fink, Citation2016; Hindman & Walker, Citation2020; Lynn et al., Citation2004; Pedersen et al., Citation2009; Shaw & Hoeber, Citation2003).

Despite literature on delivering primary prevention activities through sport, it is less clear how much work has been done with regard to a response to interpersonal gender-based violence against adult women participating in the sport setting (Lang et al., Citation2018). Within this context, our primary research question asks what has the focus been of research into interpersonal gender-based violence against adult women by men in sport? Then, given this, what are the potential areas for future sport management research if sport is also expected to be a successful setting for primary prevention of violence against women in society more broadly?

Methods

Given the breadth of scope in the question, we reviewed current empirical research using Arksey and O'Malley’s (Citation2005) scoping review framework. Scoping reviews map a research area, particularly “the main sources and types of evidence available … especially where an area is complex (Arksey & O'Malley, Citation2005, p. 21)”. Scoping reviews differ from systematic reviews in that they are broader in scope, using a more expansive review question and inclusion criteria than a systematic review, such as including a wider variety of study designs (Munn et al., Citation2018). Unlike systematic reviews, scoping reviews are not intended to be an exhaustive review of existing literature, nor are they intended to comment on the quality of studies. However, scoping reviews do share similar processes as systematic reviews in that they are rigorously undertaken and provide “a transparent method for mapping areas of research” in order to review a research field “in terms of the volume, nature and characteristics of the primary research” (Arksey & O'Malley, Citation2005, p. 30). As such, scoping reviews highlight key gaps in knowledge and provide accessible information to inform policy makers and administrators/practitioners, and guide future research. Such a review is critical for sport management to identify key gaps for future research and development in this space.

Arksey and O'Malley’s (Citation2005) framework guided the review’s methodological processes in the key areas of (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data; and (5) collating, summarising, and reporting results. In addition, we drew upon Levac et al.’s (Citation2010) development of Arksey and O’Malley’s framework by:

balancing feasibility with breadth and comprehensiveness of the scoping process; using an iterative team approach to selecting studies and extracting data; incorporating a numerical summary and qualitative thematic analysis; identifying the implications of the study findings for policy, practice, or research. (Levac et al., Citation2010, p. 8)

Research strategy

The search strategy had two purposes. The first was to find studies that investigated interpersonal gender-based violence against adult women who participate in sport. The second was to seek studies set in sport-specific contexts. As such, the search terms were as follows: [“intimate partner violence” or “domestic violence” or “intimate partner abuse” or “domestic abuse” or “sexual violence” or “harassment” or “abuse” or “stalking” or “online abuse” or “cyber-bullying”] AND [“community sport” or “sports clubs” or “sports organisations” or “sport”]. Terms were searched in the Title and Abstract fields.

An initial search was conducted on April 11th, 2019 across 14 databases. Databases were chosen to cover a broad number of fields such as social sciences, medical sciences, sport, education, and gender studies and to ensure we captured all potentially relevant studies. Databases include British Education Index, CINAHL, e-book Collection, Educational Administration Abstracts, ERIC, Human Resources Abstracts, LGBT Life, Open Dissertations, SocINDEX, SPORTDisucss, Women’s Studies, Scopus, Embase, and PsychINFO. Results were limited to English language articles only and those published in the years 2000–2019. The choice for limiting articles to those published after 2000 was in part due to project feasibility but also to ensure a focus on a period of change in global objectives to eliminate violence against women following the UN’s Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women in 1993. Whilst the UN’s Declaration took place in 1993, it was 2000 before the General Assembly designated 25 November as the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women. The aim of the day was to “invite” governments, international organisations and non-government organisations to “organise activities” that would raise public awareness of the issue on an annual basis (Articles One and Two of the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women – Proclaimed by General Assembly resolution 54/134 of 7 February 2000).

After a brief pause, a second search was conducted on March 19th, 2020 to find relevant studies published since the last search (i.e. April 2019 to March 2020). Reference lists of all included publications, the authors’ own archives, and targeted topical journals were also searched.

Inclusion criteria

Studies needed to specifically investigate interpersonal gender-based violence against adult women by men. This excluded studies on broader types of maltreatment such as male on male, female on female, abuse not specifically against women by men, and other forms of abuse e.g. drug and alcohol. Furthermore, studies needed to be set in sport contexts such as sports clubs, community sport, and sport organisations to be included. As our focus was on adult women, studies on girls (predominantly under the age of 16–18), child abuse in sport, and adult survivors of child abuse were also excluded. Given our focus on the interpersonal gender-based violence against adult women, we excluded studies that primarily focussed on primary prevention (e.g. gender equality work) or on male sportsmen’ perpetration of violence against women more broadly (e.g. male college athletes abuse of women, not necessarily in the sporting context). We excluded conference proceedings and book reviews.

At the full-text review stage the inclusion and exclusion criteria were further refined. As argued by Levac et al. (Citation2010) in furthering Arksey and O'Malley’s (Citation2005) scoping review method, study selection is “an iterative process involving searching the literature, refining the search strategy, and reviewing articles for study inclusion’s” (p. 4). The first refinement related to the sport context. For inclusion, studies needed to focus on women as victims of interpersonal gender-based violence whilst participating (for example, playing, volunteering, officiating, or coaching) in sport. Thus, papers on women in other roles in sport such as clinical staff or sport media (professionals who may work in the sport environment but not directly for a sport organisation) were excluded. The sport context also needed to be a traditional structured sport. This excluded un-structured sport (e.g. fitness, hiking, social sport), and E-sports. Secondly, studies centred on “safeguarding” were excluded for primarily being a preventative measure against child abuse and thus not related to interpersonal gender-based violence against adult women. Finally, only empirical studies and systematic or scoping literature reviews were included (e.g. editorials, commentaries, narrative literature reviews, and journal special edition introductions were excluded). Studies were also excluded if their results did not differentiate between female and male participants or did not differentiate between child abuse and abuse experienced as an adult.

Identifying relevant studies and paper selection

The study selection and data extraction processes utilised a team with both content and review methodology expertise (Levac et al., Citation2010) and took an iterative and transparent approach. After the team finalised search terms, databases, and inclusion/exclusion criteria, the second author independently conducted the search, and the study selection processes at the title and abstract levels (consulting with the first author as needed). Both authors then concurrently and independently reviewed the full-text papers. Studies where inclusion was not unanimous, and reasons for doubt, were discussed among these two authors and a final consensus agreed upon.

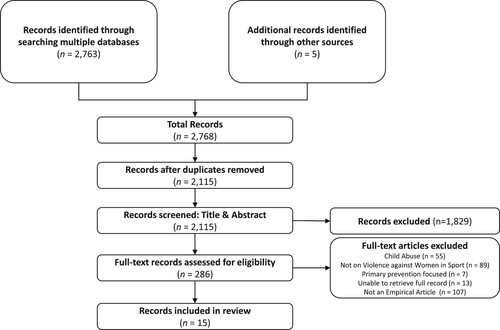

shows our paper selection, following the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (Tricco et al., Citation2018). We found an initial 2763 papers in our electronic database search. Following duplicate removal, this was reduced to 2115 papers. However, once we had undertaken a title and abstract search, and full-text reviews in adherence to our inclusion and exclusion criteria, we agreed upon 15 papers to be included in this scoping review.

One of the key challenges in determining inclusion was how authors referred to the population group being studied and whether they had clearly differentiated between experiences of interpersonal gender-based violence in childhood (more often termed sexual abuse given the power difference between victim and perpetrator, such as child and adult) and experiences of interpersonal gender-based violence in adulthood (sexual assault and harassment) where it was clear there was a mixed cohort. For example, whilst Ohlert et al. (Citation2018) and Leahy et al. (Citation2002) provide examples of the few instances of prevalence of sexual violence and sexual abuse (respectively), both studies ask participants to reflect upon experiences throughout their lives with Ohlert et al.’s (Citation2018) participants reporting that 67% of first incident of sexual violence occurred under 17 years of age. Another challenge here is what age constitutes “adult” when age of consent for sex differs within and across countries (in Australia, for example, the age of consent differs between states, which Leahy et al. (Citation2002) point out in their study of sexual abuse amongst athletes in Australia). As this scoping review was guided by the UN definition of violence against women and the typology of violence (), both of which are broader than sexual violence, we used the age of majority, which in Australia is 18 years of age across all States and Territories. The line is blurred, and as such we may have excluded some studies that could have been argued either way. The smaller number of papers eventually included in the review alert us to the fact that there is less research focused on interpersonal gender-based violence against women participating in sport during adulthood.

Collating, summarising and reporting the results

Following finalisation of the list of included studies, a data extraction table was designed to answer the research question. The data extraction process was conducted independently by the second Author and checked by the first Author. Key data extraction table cells included the sport level (e.g. elite, community, university/college), the type of interpersonal gender-based violence (intimate partner violence/domestic violence; sexual harassment and abuse; online abuse/cyber-bullying), and the study results summary. Even though results were extracted, this paper does not synthesise them. There were substantial differences in theoretical, methodological approaches and measures used across the studies and, as such, the heterogeneity makes it difficult to compare studies on the basis of results.

The qualitative thematic analysis was primarily conducted by the first Author in discussion and agreement with the second Author. The first Author engaged deeply with each of the included studies through several readings. Data were organised through a block and file process that involved grouping segments of the information provided in the studies into a table with headings categorising the contents of columns and which aligned with the research question (Grbich, Citation2007). The final headings were agreed with the second Author (Grbich, Citation2007). These headings represent overarching dominant themes as they arose across the studies – including what was present and what was missing from the included studies.

The results below follow the framework set by Arksey and O'Malley (Citation2005), as refined by Levac et al. (Citation2010): (1) provide a descriptive numerical summary and qualitative thematic analysis; (2) report results in answer to the research questions; (3) consider the meaning of the findings, particularly implications for policy, practice, and future research.

Results

Numerical summary

We present a description of the papers included in the review in . We found one study that examined a sport organisation’s response to violence against adult women (Vertommen et al., Citation2015). The remainder of the papers either focused on prevalence and/or the lived experience of interpersonal gender-based violence against adult women participating in sport.

Table 1. Description of included studies.

The papers in this review are predominantly single quantitative studies (n = 11), with three qualitative studies and one study using mixed methods. The primary quantitative method of data collection was surveys (n = 10) with one study undertaking an analysis of telephone records to a helpline (Vertommen et al., Citation2015). The three qualitative studies used either interviews with between four to six participants (n = 2) or an online ethnography, which is also referred to as a “netography” (Kavanagh et al., Citation2016, p. 787). The mixed methods study used a combination of survey and focus groups (McGovern, Citation2021). McGovern’s (Citation2021) full study actually included both male and female participants, but the paper reported only on female survey responses and three focus groups of female athletes (n = 2) and non-athletes (n = 1).

Most of the studies included in this review originated from the United States (n = 8), followed by Europe (n = 3). Whilst there was a global spread of countries within which these studies took place, there were some noticeable gaps across the South American and Asia/Pacific region, as well as Canada and United Kingdom.

The context or sample populations for the studies included in the review were university/college student dominant (n = 6). This may be because of the structure of sport in the United States being significantly based on school and college participation, and the dominance of United States studies in the review. But also, it could suggest a reliance on these populations because of ready access to female athletes in these contexts. Whilst there were seven studies based on broader community or a mixture of community and university/college population groups, there does appear to be an imbalance in current research knowledge with the focus on university/college populations. Only two studies were focused on adult elite populations.

Thematic findings

With the heterogeneity of many of these studies, it was challenging to establish the overarching themes as part of a qualitative analysis or consider results of the studies in any detailed way. However, four overarching themes regarding scope of studies were identified: forms of violence, the narrow scope of “interpersonal” relationships in sport, prevalence, and paucity of theoretical underpinning.

Forms of violence

The dominant theme arising was the lack of breadth of interpersonal gender-based violence being examined. Most of the studies included in the review examined some form of sexual violence (n = 11), as opposed to other forms of interpersonal gender-based violence against women such as intimate partner violence or dating violence. One study reported on a form of violence called “mobbing” which was explained by the authors to be a term somewhat unique to Serbia and covers various “forms of punishment, humiliation, mistreatment and abuse”, including sexual abuse and harassment (Lazarević et al., Citation2014, p. 155). As can be seen in and , studies that focused on some form of sexual violence looked at either sexual harassment or sexual abuse or sexual harassment and abuse or other concepts such as victimisation and consent. With the remaining three studies, two examined intimate partner violence and one examined dating violence. The final study was quite unique compared to the others, focusing on virtual maltreatment (Kavanagh et al., Citation2016). Kavanagh’s and colleagues’ study opens up the growing social media space as an additional context in which abuse can play out, beyond the traditional physical environment of sport. Such an environment, given its potential for perpetrator anonymity, enables “maladaptive parasocial interaction” (Kavanagh et al., Citation2016, p. 786), where “maltreatment” includes interpersonal violence such as “physical, sexual and emotional abuse as well as bullying and neglect of individuals” (Kavanagh et al., Citation2016, p. 786), otherwise known as cyber-bulling. Although Kavanagh and colleagues acknowledge that “men are disproportionately the perpetrators and women disproportionately the victims of online sexual hostility” (p. 790), the gendered bias in this form of interpersonal violence is not fully explored. Although this study does give insight into the fan/athlete relationship and wider contexts in which interpersonal violence in sport may occur.

Table 2. Terms and definitions of violence referred to in included papers.

Given the heterogeneity of the studies, it is unsurprising that they each use unique terms, and a variety of associated definitions (see ). The varying terminologies used across the studies show a lack of consensus in sport research or consistent approach to understanding the overall phenomenon of interpersonal gender-based violence against adult women. It makes such studies challenging to synthesise and highlights significant gaps in the current research literature for sport broadly, and the management of sport specifically.

Narrow scope of ‘interpersonal’ relationships in sport

The overlap and/or differentiation of terms also highlights another key finding. Sexual violence studies in this review predominantly focus on abuse or harassment within the coach–athlete relationship (Ahmed et al., Citation2018; Fejgin & Hanegby, Citation2001; Johansson & Larsson, Citation2017; Volkwein-caplan et al., Citation2002). Three papers reported on the perception of coaches’ behaviours and their prevalence amongst student-athletes using similar survey instruments (across India, Israel, and the United States) (Ahmed et al., Citation2018; Fejgin & Hanegby, Citation2001; Volkwein-caplan et al., Citation2002). The behaviours ranged from physical proximity whilst providing instruction through to sexual advances being made. Volkwein-caplan et al. (Citation2002) found that for most behaviours, except for direct sexual advances, student non-athletes were more likely to perceive behaviours as sexual harassment. This raises the question as to acceptability and normalisation of behaviours in the sporting context. Prevalence rates were starkly different between the studies. Approximately a third of female athletes in India had experienced what they perceived to be unwanted sexual behaviour or inappropriate verbal/physical behaviour by a male coach whilst 14% of the Israeli athletes had experienced what they considered to be sexual harassment by a male coach. In the United States, prevalence rates ranged from 2% to 19% for perceived sexual advances and sexist comments amongst student-athletes. However, Johansson and Larsson (Citation2017) explore intimate relationships between elite athletes and their coaches. Their paper highlights a potential fine line between an intimate relationship and an abusive intimate relationship where power imbalances are at place in the sporting context. Yet they frame their paper around the phenomena of sexual abuse rather than intimate partner violence, which would seem potentially more relevant. Intimate partner violence is defined by the World Health Organization (Citation2021) as “behaviour by a current or former male intimate partner” that “causes physical, sexual or psychological harm” (p. 4). This can include physical violence, sexual violence, psychological violence (including intimidation, belittling, humiliating) and controlling behaviours, otherwise known as coercive control, that can include isolating the victim, monitoring movements, and restricting access to services such as medical care. Johansson and Larsson’s (Citation2017) framing could be related to such definitions, with sexual abuse pertaining more to victims who are underage or cannot consent (not suggested within the paper itself, given the participants are aged 26–30). There may be a question in the sport context as to when an intimate relationship becomes sexual “abuse”, or sexual violence as part of intimate partner violence. Both Bendolph (Citation2005) and Milner and Baker (Citation2017) provide a definition of intimate partner violence, whilst Cantor et al. (Citation2021) provide a definition of dating violence, that incorporates this broader range of behaviours within interpersonal relationships. This is something that sport may need to explore in more detail, to ensure sufficient policy and practices are in place to protect both athletes and coaches.

Studies that focus on intimate partner violence predominantly examine sport participation as a protective factor against such violence (Bendolph, Citation2005; Milner & Baker, Citation2017). Bendolph’s (Citation2005) graduate dissertation examines potential links between competitive sport participation as a protective factor for African-American women, under the premise that sport is beneficial for women’s self-efficacy and self-esteem. Bendolph (Citation2005) found that there was no difference in intimate partner violence experiences between African-American women who had and had not participated in competitive sport. However, with a sample size of only 30 women, Bendolph acknowledges this sample was insufficient to enable significance in findings and therefore reduced the strength of her findings. Similarly, Milner and Baker (Citation2017) used the theory that sport participation is associated with improved self-esteem for women and therefore could be a protective factor against intimate partner violence. In contrast to Bendolph, their study used a nationally representative sample (n = 8043) and found that sport participation was a protective factor against intimate partner violence. Such contradictory results, and being US-centric, suggest further research is required.

However, intimate partner violence is rarely examined within the sport context, and yet abuse in some coach–athlete relationships may be considered intimate partner violence/dating violence (beyond sexual abuse). Furthermore, what about intimate partner violence that goes beyond the coach–athlete relationship? Other intimate relations occur in sport, whether it be between athletes, administrators, volunteers, or officials.

When considering the scope of the research on interpersonal relationships in sport, what appears to be another gap in the current research is the role of sport in responding to women athletes, coaches, administrators, volunteers, officials, or family members who are experiencing intimate partner violence either within or outside of sport. The particular case of Kenyan distance runner Agnes Tirop, murdered at home by her husband, heralds the importance of sports’ response.

Prevalence

A key focus of many of the papers reviewed, included at least in part the prevalence of interpersonal gender-based violence incidences (n = 12). As shows, prevalence varies between studies, from 1.92% (Volkwein-caplan et al., Citation2002) to 86.8% (Lazarević et al., Citation2014) for any form of sexual violence. However, it is not clear to what extent many of the prevalence rates relate to or across sexual harassment and/or sexual assault, given the terminology used across the studies differs extensively. For example, athletes reported unwanted sexual behaviours (Ahmed et al., Citation2018); sexist comments (Volkwein-caplan et al., Citation2002); verbal or physical advances (Volkwein-caplan et al., Citation2002); forms of sexual coercion (McGovern, Citation2021) and threatened or forced to have sex (Fasting et al., Citation2008; McGovern, Citation2021). It is clear women participating in sport are also victims of intimate partner or dating violence with intimate partner violence ranging from 30.5% to 40% (Bendolph, Citation2005; Milner & Baker, Citation2017) and 59.7% for dating violence (Cantor et al., Citation2021). The global estimate for prevalence of any form of intimate partner violence or sexual violence is 30% of women (World Health Organization, Citation2021). These studies, whilst not necessarily comparing the same type of harassment or abuse, clearly show that the prevalence among female sports participants is high – whether that be experiencing such violence inside or outside the sporting context. Thus, there is much work here for sports’ organisations to do in responding to women’s experiences. A key gap is understanding the prevalence rates for other roles women hold in sport, such as coaches, officials, volunteers, or administrators. The sample population of all but one of the studies focused on athletes. Vertommen et al. (Citation2015) referred to 2% of calls to the helpline related to victims that included coaches, medical staff, and other personnel (gender unspecified). The need to respond to interpersonal gender-based violence against adult women is highlighted by Vertommen et al.’s (Citation2015) report on calls made to a helpline set up by Netherlands Olympic Committee and the Netherlands Sports Confederation. This was the only study to examine a sport organisation’s response to interpersonal gender-based violence. The helpline is a 24-hour, 7 day a week service providing counselling and referral support for sexual harassment and abuse in sport. The aim of the helpline appears to have been to respond to child abuse in sport, however Vertommen et al. (Citation2015) report that over 50% of total female calls were made in relation to female victims aged over 16 years.

Table 3. Prevalence rates across included studies.

Paucity of theoretical underpinning

Our final key finding from the scoping review is the absence of theoretical underpinning for most of the papers included in the review. Theoretical underpinning of research is vital to guide the development of a research study and to drive sense-making that goes beyond the study at hand to a greater insight into the complexity of the social world (Collins & Stockton, Citation2018). Ahmed et al. (Citation2018) used social role theory in their assessment of perceptions of acceptable sexual behaviour of coaches and occurrence of sexual harassment. Fasting et al. (Citation2008) used the Sport Protection Hypothesis. Given the gendered power relations that are embedded in sport and which impact women’s sport experiences (LaVoi, 2016; Mansfield et al., Citation2018) as well as the embodiment of such gendered power relations through violence against women makes it somewhat surprising that feminist theories have not been drawn upon in developing or analysing this phenomenon. Research that uses such theory can better identify gendered power, challenge inequalities, and spur change (Knoppers & McLachlan, Citation2018). There is significant feminist theory development within sport management (Aitchison, Citation2005; Shaw & Hoeber, Citation2003; Thorpe & Chawansky, Citation2017; Zipp et al., Citation2019) that could be used to frame future studies of violence against women in sport, whether it be the lived experience of women athletes, officials or administrators, or sport organisations and management’s response to violence against women.

Discussion and recommendations for future research

This review has highlighted several gaps in the current research literature that is poignant for sport management to connect with and fill, with the key finding being only one study had examined sports’ organisations response to interpersonal gender-based violence against women in sport. It is surprising that despite studies reporting on prevalence of such violence and exploring women’s lived experiences, there is very little research that examines the best ways for sports organisations to respond to and ultimately prevent such violence being experienced by adult women participating in sport. Even the helpline reported on by Vertommen et al. (Citation2015) appeared to focus on child abuse and it was only in the capturing of data that we can see female athlete victims needing the service, as well as those potentially in other sport-related roles.

Interpersonal gender-based violence potentially includes numerous forms of abuse covering, as the UN definition covers, “physical, sexual or psychological harm” and can include “threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty” that may occur across public and private spheres. The topics of papers that we excluded indicate that research has predominantly focused to date on (gendered) child abuse in sport (including adults with a child abuse history in sport). This is not surprising, given the extensive work of Kari Fasting and Celia Brackenridge over the past 30 years on this topic (Brackenridge & Rhind, Citation2014; Fasting et al., Citation2011; Fasting & Brackenridge, Citation2002), the focus on institutional child abuse and child protection particularly in sport (Commonwealth of Australia, Citation2017), and subsequent media focus on high profile cases of sexual abuse of children in elite level sport (Mountjoy, Citation2019; Mountjoy et al., Citation2020; Nite & Nauright, Citation2020).

Whilst it is important to examine sexual violence across women’s lives, the drivers behind and subsequent prevention of and responses to child sexual abuse or child abuse more broadly differ from those in relation to adult women. We need studies to provide either greater differentiation in results of mixed cohorts to better understand the impact of this form of abuse as it relates to women across their life-course, providing experiences that span childhood and adulthood, or we need more studies that examine and address each phenomenon alone in sport together with sport organisation’s response to it. However, focusing purely on sexual violence also ignores the many other potential forms of interpersonal gender-based violence that may be occurring in sport as Kavanagh and colleagues’ (Citation2016) paper on virtual maltreatment argue.

Considering the term “interpersonal”, this review also highlights the need for sport to consider all the interpersonal relationships that may occur in the sport context. Intimate partner violence, for example, may exist in the coach–athlete intimate relationships but it may also appear in any intimate relationship within the sport context for example between athletes, administrators, and officials. There is also a growing body of work on emotional abuse between coaches and athletes, often framed as bullying (Kerr et al., Citation2016, Citation2020; Stirling & Kerr, Citation2008). Whether this form of abuse/violence intersects with violence against women (particularly through mixed gender coach-athlete and mixed gender teams as raised by Kerr et al., Citation2016) and intimate partner violence more specifically (across both heterosexual and homosexual relationship) is worth exploring. Violence beyond the heteronormative relationship and that takes account of the many intersections of inequalities, such as women with a disability, transgender women, and culturally and linguistically diverse women, is already recognised as a gap in current research in the sport context (Kirby et al., Citation2008). Similarly, following Kavanagh and colleagues’ (Citation2016) development of typologies of virtual maltreatment, a greater examination of gendered virtual maltreatment is required that addresses the multiple interpersonal relationships existing across sport and across both elite and community levels.

Also, as we raised earlier, studies are needed that examine the role of sport organisations in responding to women athletes, coaches, administrators, volunteers, officials, or family members who may be experiencing gender-based interpersonal violence. Issues of terminology suggest that sport should engage with the terminology of interpersonal violence that draws upon more globally consistent definitions to better enable multidisciplinary collaboration between the sport industry and other key fields in this space, such as health and law/justice (United Nations, Citation2017; World Health Organization, Citation2002; Citation2013). As such, research in sport management may provide more comprehensive prevalence data to establish the foundation for prevention and response. Such foundational work can then move beyond the concept of sport for development, a primary setting for primary prevention work. Instead, sport management could establish appropriate early intervention and crisis response that applies to both women experiencing violence whilst participating in sport, and those female athletes who may be experiencing violence outside of the sporting context (but may still impact their sport participation). This must happen at every level of sport, from community-based sport, university/college sport settings and elite sport. If sport does not address and prevent violence against women occurring within sport, how can it be used as a setting to deliver a successful strategy for the primary prevention of violence against women in society more broadly?

Finally, engaging with theory to underpin research into sports organisations’ addressing interpersonal gender-based violence is vital if we are to not only explore new ways of knowing, but also new ways of doing in our responses to such violence. Such actions might include policy development, implementation and practice, reflection upon and change of organisational culture, sport organisation communication or marketing campaigns, or the development and delivery of training programmes for coaches and administrators.

Our recommendations for future sport management research then fall into the following five broad research themes:

the response of sport organisations to interpersonal gender-based violence against women,

an examination of all potential forms of gender-based interpersonal violence against adult women across all contexts of sport (physical and virtual),

experiences of interpersonal gender-based violence amongst non-athletes participating in sport, including coaches, officials, volunteers, or administrators,

experience of interpersonal gender-based violence beyond the heteronormative relationship and that takes account of the many intersections of inequalities,

exploring the application of theory to the understanding of interpersonal gender-based violence in sport as well as to the development of appropriate responses to such violence.

Conclusion and limitations

There is currently a significant gap in research focusing on adult women experiencing interpersonal gender-based violence in sport, and sport organisations’ response to such violence. Despite there being some focus on sexual violence of adult women, particularly the coach–athlete relationship, research in the sport context has been somewhat quiet on the forms of violence occurring and subsequently investigating appropriate prevention and response.

The strengths of this review correspond with the general strengths inherent in all scoping reviews. Scoping reviews can help explore the range and nature of research on topics, especially relatively new and disparate research topics that have not been comprehensively reviewed before (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005), such as interpersonal gender-based violence against women participating in sport. The broad scope captures literature on and around a central question. This allowed us to see what had been researched and where the gaps were. This meant being able to scope what had been researched on the size (prevalence) and nature (lived context) of the issue of interpersonal gender-based violence against women participating in sport. This is knowledge that should precede, and indeed inform, efforts to respond to interpersonal gender-based violence against women. Our scoping review findings suggest that research into the size and nature of violence against adult women in sport is still in its infancy, and thus, future research should explore this to in-turn help inform the research, policy, and practices of sport managements’ response to the issue.

The limitations of this scoping review, again, correspond with the general limitations of scoping reviews. Unlike systematic reviews, scoping reviews do not seek to identify a fully exhaustive list of relevant research that comprehensively represents all studies in a particular area. As such, we do not claim to have identified all the extant research literature on the prevalence, lived context, and response to violence against women in sport. Additionally, scoping reviews, including ours, do not assess nor make conclusions about the quality of studies conducted on the topic of interest (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). In part, this is due to a greater focus on breadth of analysis rather than depth of analysis on a narrower group of studies. For this reason, we have not appraised the quality of studies identified in our review. The final limitation of scoping reviews is that unlike systematic reviews, they do not synthesise study findings to achieve a single decisive conclusion about a research question. Scoping reviews, such as ours, instead seek to produce a descriptive and narrative summary of the available studies (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). For this reason, we have not drawn any conclusions about potential effectiveness of sport organisations response to violence against women. In addition, our inclusion and exclusion criteria for this scoping review limited both the context for women’s sport participation, through the exclusion of e-sports and unstructured forms of sport, as well as non-heteronormative relationships. However, these limitations provide more opportunities for future sport management research particularly examining e-sports as it is being considered for inclusion at future Olympic Games.

In a final reflection on knowledge and evidence production in the field of sport management, we note the value of comprehensive and systematic summaries and syntheses of new knowledge in this still maturing field of scholarship. We support Dowling and colleagues’ (Citation2018) call for more scoping reviews in sport management to help advance understanding, promote collaboration, and better contribute to evidence-based policy and practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the scoping review.

- Ahmed, M. D., van Niekerk, R. L., Ho, W. K. Y., Morris, T., Baker, T., Ali Khan, B., & Tetso, A. (2018). Female student athletes’ perceptions of acceptability and the occurrence of sexual-related behaviour by their coaches in India. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 42(1), 33–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924036.2017.1310661

- Aitchison, C. C. (2005). Feminist and gender research in sport and leisure management: Understanding the social-cultural nexus of gender-power relations. Journal of Sport Management, 19(4), 422–441. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.19.4.422

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Bekker, S., & Posbergh, A. (2022). Safeguarding in sports settings: Unpacking a conflicting identity. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 14(2), 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2021.1920456

- Bendolph, L. N. (2005). The occurrence of abusive relationship patterns among African-American females: The impact of competitive sports. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 66(5-B), 2809.

- Brackenridge, C. (1997). ‘He Owned Me Basically … ’ women’s experience of sexual abuse in sport. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 32(2), 115–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/101269097032002001

- Brackenridge, C. (2001). Spoilsports: Understanding and preventing sexual exploitation in sport. Taylor & Francis Ltd.

- Brackenridge, C. H., & Rhind, D. (2014). Child protection in sport: Reflections on thirty years of science and activism. Social Sciences, 3(3), 326–340. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci3030326

- Cantor, N., Joppa, M., & Angelone, D. (2021). An examination of dating violence among college student-athletes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(23–24), NP13275–NP13295. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520905545

- Clark, D. (2017). Boys will be boys: Assessing attitudes of athletic officials on sexism and violence against women. The International Journal of Sport and Society, 8(1), 31–50. https://doi.org/10.18848/2152-7857/CGP/v08i01/31-50

- Collins, C. S., & Stockton, C. M. (2018). The central role of theory in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918797475

- Commonwealth of Australia. (2017). Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Abuse. Final Report Volume 14.

- Corboz, J., Flood, M., & Dyson, S. (2016). Challenges of bystander intervention in male-dominated professional sport: Lessons from the Australian football league. Violence Against Women, 22(3), 324–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801215602343

- Dowling, M., Leopkey, B., & Smith, L. (2018). Governance in sport: A scoping review. Journal of Sport Management, 32(5), 438. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2018-0032

- Fasting, K., & Brackenridge, C. (2002). Sexual harassment and abuse in sport: International research and policy perspectives. Whiting & Birch.

- Fasting, K., & Brackenridge, C. (2009). Coaches, sexual harassment and education. Sport, Education and Society, 14(1), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573320802614950

- Fasting, K., Brackenridge, C., & Sundgot-Borgen, J. (2003). Experiences of sexual harassment and abuse among Norwegian elite female athletes and nonathletes. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 74(1), 84–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2003.10609067

- Fasting, K., Brackenridge, C., & Sundgot-Borgen, J. (2004). Prevalence of sexual harassment among Norwegian female elite athletes inrelation to sport type. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 39(4), 373–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690204049804

- Fasting, K., Brackenridge, C., & Walseth, K. (2002). Consequences of sexual harassment in sport for female athletes. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 8(2), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600208413338

- Fasting, K., Brackenridge, C., & Walseth, K. (2007). Women athletes’ personal responses to sexual harassment in sport. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 19(4), 419–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200701599165

- Fasting, K., Brackenridge, C. H., Miller, K. E., & Sabo, D. (2008). Participation in college sports and protection from sexual victimization. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 6(4), 427–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2008.9671883

- Fasting, K., Chroni, S., Hervik, S. E., & Knorre, N. (2011). Sexual harassment in sport toward females in three European countries. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 46(1), 76–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690210376295

- Fasting, K., Chroni, S., & Knorre, N. (2014). The experiences of sexual harassment in sport and education among European female sports science students. Sport, Education and Society, 19(2), 115–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2012.660477

- Fasting, K., & Sand, T. S. (2015). Narratives of sexual harassment experiences in sport. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 7(5), 573–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2015.1008028

- Fejgin, N., & Hanegby, R. (2001). Gender and cultural bias in perceptions of sexual harassment in sport. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 36(4), 459–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/101269001036004006

- Fink, J. S. (2016). Hiding in plain sight: The embedded nature of sexism in sport. Journal of Sport Management, 30(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2015-0278

- Flood, M. (2008). Men, sex, and homosociality: How bonds between men shape their sexual relations with women. Men and Masculinities, 10(3), 339–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X06287761

- Flood, M., & Dyson, S. (2006). Building cultures of respect and non-violence: A review of literature concerning adult learning and violence prevention programs with men. AFL and VicHealth.

- Grbich, C. (2007). Qualitative data analysis: An introduction. Sage Publications Ltd.

- Hindman, L. C., & Walker, N. A. (2020). Sexism in professional sports: How women managers experience and survive sport organizational culture. Journal of Sport Management, 34(1), 64–76. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2018-0331

- Johansson, S., & Larsson, H. (2017). ‘This might be him; the guy I’m gonna marry’: Love and sexual relationships between female elite-athletes and male coaches. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 52(7), 819–838. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690215626593

- Kavanagh, E., Adams, A., Lock, D., Stewart, C., & Cleland, J. (2020). Managing abuse in sport: An introduction to the special issue. Sport Management Review, 23(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2019.12.002

- Kavanagh, E., Jones, I., & Sheppard-Marks, L. (2016). Towards typologies of virtual maltreatment: Sport, digital cultures & dark leisure. Leisure Studies, 35(6), 783–796. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2016.1216581

- Kerr, G., Jewett, R., Macpherson, E., & Stirling, A. (2016). Student-Athletes’ experiences of bullying on intercollegiate teams. Journal for the Study of Sports and Athletes in Education, 10(2), 132–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/19357397.2016.1218648

- Kerr, G., Willson, E., & Stirling, A. (2020). “It was the worst time in my life”: The effects of emotionally abusive coaching on female Canadian national team athletes. Women in Sport & Physical Activity Journal, 28(1), 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1123/wspaj.2019-0054

- Kerr, J. H. (2005). Rethinking aggression and violence in sport. Routledge.

- Kirby, S. L., Demers, G., & Parent, S. (2008). Vulnerability/prevention: Considering the needs of disabled and gay athletes in the context of sexual harassment and abuse. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 6(4), 407–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2008.9671882

- Knoppers, A., & McLachlan, F. (2018). Reflecting on the use of feminist theories in sport management research. In L. Mansfield, J. Caudwell, B. Wheaton, & B. Watson (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of feminism and sport, leisure and physical education (pp. 163–179). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Krug, E., Dahlberg, L., Mercy, J., Zwi, A., & Lozano, R. (2002). World report on violence and health. World Health Organization.

- Lang, M., Mergaert, L., Arnaut, C., & Vertommen, T. (2018). Gender-based violence in EU sport policy: Overview and recommendations. Journal of Gender-Based Violence, 2(1), 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1332/239868018X15155986979910

- Lazarević, S., Dugalić, S., Milojević, A., Koropanovski, N., & Stanić, V. (2014). Unethical forms of behavior in sports. Facta Universitatis: Series Physical Education & Sport, 12(2), 155–166.

- Leahy, T., Pretty, G., & Tenenbaum, G. (2002). Prevalence of sexual abuse in organised competitive sport in Australia. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 8(2), 16–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600208413337

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien Kelly, K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/17485908569

- Liston, R., Mortimer, S., Hamilton, G., & Cameron, R. (2017). A team effort: Preventing violence against women through sport. Our Watch.

- Lynn, S., Hardin, M., & Walsdorf, K. (2004). Selling (out) the sporting woman: Advertising images in four athletic magazines. Journal of Sport Management, 18(4), 335–349. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.18.4.335

- Mansfield, L., Caudwell, J., Wheaton, B., & Watson, B. (2018). The Palgrave handbook of feminism and sport, leisure and physical education. Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- McGinley, M., Rospenda, K. M., Liu, L., & Richman, J. A. (2016). It isn’t all just fun and games: Collegiate participation in extracurricular activities and risk for generalized and sexual harassment, psychological distress, and alcohol use. Journal of Adolescence, 53(1), 152–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.10.001

- McGovern, J. (2021). Strong women never mumble: Female athlete attitudes about sexual consent. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(1–2), 751–780. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517730022

- Mergaert, L., Arnaut, C., Vertommen, T., & Lang, M. (2016). Study on gender-based violence in sport: Final report. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Messner, M. A. (1992). Power at play: Sports and the problem of masculinity. Beacon Press.

- Miller, E., Tancredi, D. J., McCauley, H. L., Decker, M. R., Virata, M. C. D., Anderson, H. A., Stetkevich, N., Brown, E. W., Moideen, F., & Silverman, J. G. (2012). “Coaching boys into men”: A cluster-randomized controlled trial of a dating violence prevention program. Journal of Adolescent Health, 51(5), 431–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.01.018

- Milner, A. N., & Baker, E. H. (2017). Athletic participation and intimate partner violence victimization: Investigating sport involvement, self-esteem, and abuse patterns for women and men. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32(2), 268–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515585543

- Mountjoy, M. (2019). ‘Only by speaking out can we create lasting change’: What can we learn from the Dr Larry Nassar tragedy? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(1), 57–60. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-099403

- Mountjoy, M., Brackenridge, C., Arrington, M., Blauwet, C., Carska-Sheppard, A., Fasting, K., Kirby, S., Leahy, T., Marks, S., Martin, K., Starr, K., Tiivas, A., & Budgett, R. (2016). International Olympic Committee consensus statement: Harassment and abuse (non-accidental violence) in sport. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(17), 1019–1029. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096121

- Mountjoy, M., Vertommen, T., Burrows, K., & Greinig, S. (2020). #Safesport: Safeguarding initiatives at the Youth Olympic Games 2018. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54(3), 176–182. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-101461

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143–143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- Nite, C., & Nauright, J. (2020). Examining institutional work that perpetuates abuse in sport organizations. Sport Management Review, 23(1), 117–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2019.06.002

- Ohlert, J., Seidler, C., Rau, T., Rulofs, B., & Allroggen, M. (2018). Sexual violence in organized sport in Germany. Sportwissenschaft, 48(1), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12662-017-0485-9

- Our Watch. (2021). Change the story: A shared framework for the primary prevention of violence against women in Australia ((2nd ed.)).

- Our Watch, Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS), & VicHealth. (2015). Change the story: A shared framework for the primary prevention of violence against women and their children in Australia.

- Pedersen, P. M., Choong Hoon, L., Osborne, B., & Whisenant, W. (2009). An examination of the perceptions of sexual harassment by sport print media professionals. Journal of Sport Management, 23(3), 335–360. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.23.3.335

- Rintaugu, E. G., Kamau, J., Amusa, L. O., & Toriola, A. L. (2014). The forbidden acts: Prevalence of sexual harassment among university female athletes. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation & Dance, 20(3.1), 974–990.

- Roberts, V., Sojo, V., & Grant, F. (2020). Organisational factors and non-accidental violence in sport: A systematic review. Sport Management Review, 23(1), 8–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2019.03.001

- Rodriguez, E. A., & Gill, D. L. (2011). Sexual harassment perceptions among Puerto Rican female former athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 9(4), 323–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2011.623461

- Sand, T. S., Fasting, K., Chroni, S., & Knorre, N. (2011). Coaching behavior: Any consequences for the prevalence of sexual harassment? International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 6(2), 229. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.6.2.229

- Shaw, S., & Hoeber, L. (2003). “A strong man is direct and a direct woman is a bitch”: Gendered discourses and their influence on employment roles in sports organizations. Journal of Sport Management, 17(4), 347. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.17.4.347

- Sønderlund, A. L., O’brien, K., Kremer, P., Rowland, B., De Groot, F., Staiger, P., Zinkiewicz, L., & Miller, P. G. (2014). The association between sports participation, alcohol use and aggression and violence: A systematic review. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 17(1), 2–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2013.03.011

- Spaaij, R., & Schaillée, H. (2019). Unsanctioned aggression and violence in amateur sport: A multidisciplinary synthesis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 44, 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.11.007

- Stirling, A. E. (2009). Definition and constituents of maltreatment in sport: Establishing a conceptual framework for research practitioners. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 43(14), 1091. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2008.051433

- Stirling, A. E., & Kerr, G. A. (2008). Defining and categorizing emotional abuse in sport. European Journal of Sport Science, 8(4), 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461390802086281

- Sundgot-Borgen, J., Fasting, K., Brackenridge, C., Torstveit, M. K., & Berglund, B. (2003). Sexual harassment and eating disorders in female elite athletes – A controlled study. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, 13(5), 330–335. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0838.2003.00295.x

- Thorpe, H., & Chawansky, M. (2017). The gendered experiences of women staff and volunteers in sport for development organizations: The case of transmigrant workers of Skateistan. Journal of Sport Management, 31(6), 546–561. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2017-0147

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- United Nations. (2017). Glossary on sexual exploitation and abuse. Thematic glossary of current terminology related to sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) in the context of the United Nations: Second edition.

- Vertommen, T., Schipper-van Veldhoven, N. H., Hartill, M. J., & Van Den Eede, F. (2015). Sexual harassment and abuse in sport: The NOCNSF helpline. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 50(7), 822–839. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690213498079

- Volkwein-caplan, K., Schnell, F., Devlin, S., Mitchell, M., & Sutera, J. (2002). Sexual harassment of women in athletics vs academia. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 8(2), 69–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600208413340

- Women’s Sport Foundation. (1994). An educational resource kit for athletic administrators: Prevention of sexual harassment in athletic settings.

- World Health Organization. (2002). World report on violence and health.

- World Health Organization. (2013). Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women. WHO clinical and policy guidelines.

- World Health Organization. (2021). Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: Global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women.

- Zipp, S., Smith, T., & Darnell, S. (2019). Development. Gender and Sport: Theorizing a Feminist Practice of the Capabilities Approach in Sport for Development. Journal of Sport Management, 33(5), 440–449. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2019-012