ABSTRACT

Research Question

This paper seeks to contribute to the theoretical understanding of team cohesion in sport. While a robust foundation of research on team cohesion in sport exists, there is a dearth of research examining the role of physical proximity. With physical group exercise temporarily suspended due to COVID-19, herein lies an opportunity to examine team cohesion throughout different stages of physical distancing.

Research Methods

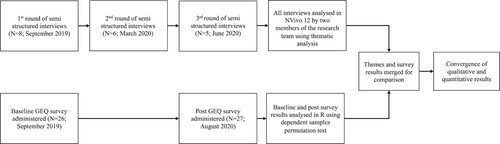

A single case mixed method study was employed comprised of semi-structured interviews (19 total) conducted at three different time points (September 2019; March 2020; June 2020) and a baseline/post administration of the GEQ Survey (September 2019 (N = 26); August 2020 (N = 27)). Qualitative data were analysed in NVivo 12, and survey data were analysed via paired t-tests.

Results and Findings

Levels of team cohesion remained stable throughout the season and during physical distancing on all three cohesion sub-scales (i.e. ATG-T, GI-S, GI-T). Three qualitative themes emerged: task and collective loyalty, resilience through social cohesion, and digital engagement.

Implications

Digital communication can temporarily fill the void of face-to-face interaction but cannot replace it long-term to build team cohesion. Adding physical proximity to the theoretical conceptualization of team cohesion makes the model more contemporary and especially relevant during times of physical distancing (e.g. pandemic, off-season, remote teams).

Practitioners and scholars have long regarded team cohesion as one of the most important small-group variables across the context of work, military, and sport (Burke et al., Citation2014; Golembiewski, Citation1962; Lott & Lott, Citation1965). With respect to the latter, team cohesion has been defined as “a dynamic process that is reflected in the tendency for a group to stick together and remain united in the pursuit of its instrumental objectives and/or for the satisfaction of member affective needs” (Carron & Brawley, Citation2000, p. 94). Given team cohesion’s focus on a dynamic process in which a group strives to achieve its instrumental objectives, team cohesion can be viewed as a natural variable to study in sport since on-field sports teams (groups) are put together to accomplish the instrumental aim of winning (Smith & Stewart, Citation2010).

Sport management researchers have highlighted the importance and implications of high levels of team cohesion (Loughead et al., Citation2016). Given the associated positive consequences – whether it be individual outcomes such as greater personal satisfaction (Burke et al., Citation2014), role clarity (Eys & Carron, Citation2001), greater individual performance (Carron et al., Citation2002), adherence (Hambrick et al., Citation2018), or desired team outcomes such as increased team performance (Fransen et al., Citation2015), team stability (Carron, Citation1982), greater team satisfaction (Burke et al., Citation2014), and opportunities to engage in shared leadership (Loughead et al., Citation2016) – it is not surprising that researchers and management executives have been trying to identify components that enhance team cohesiveness for decades (Burke et al., Citation2014; Carron, Citation1988; Carron et al., Citation1998).

Much of the research on team cohesion within sport has focused on sport teams, and specifically how team cohesion is related to team performance (Brisimis et al., Citation2018; Carron et al., Citation2002). While a robust foundation of research on outcomes of team cohesion in sport exists, there is a dearth of research examining antecedents of team cohesion in this context. With aspects of team cohesion such as face-to-face interactions, in-person communication, and physical group exercise temporarily suspended due to COVID-19, herein lies a unique opportunity to consider physical proximity as a contemporary environmental factor impacting team cohesion in sports. Physical proximity during a season was assumed to be given in elite sport teams in pre-COVID times, as team members and coaches frequently engaged in person during practice sessions throughout a season (Chelladurai, Citation2014; Güllich & Emrich, Citation2006). Yet, even before the pandemic there were episodes where physical proximity was temporarily suspended in elite sport teams (e.g. off-season, national teams; Munroe et al., Citation1999) as well as in off-field sporting enterprises (e.g. global/digital teams, home-office; Cramton, Citation2001; Garrison et al., Citation2010). However, research investigating the potential implications of this physically distanced episode on team cohesion levels in a sporting context has been scarce.

Based on Manoli et al. (Citation2022) as well as Skinner and Smith (Citation2021), this research assumes that the pandemic heightened the relevance of physical proximity in general, with various studies investigating the multifaceted implications of social distancing (i.e. lockdown) on the sport industry. As such, the pandemic depicts an ideal time frame to conduct research on one of the most important small-group variables in sport, team cohesion (Burke et al., Citation2014).

Concomitantly, the pandemic has also highlighted the importance of digital communication (Manoli et al., Citation2022; Naraine & Wanless, Citation2020; Skinner & Smith, Citation2021), but the extent to which these activities could impact team cohesion and replace face-to-face interactions is unknown. “As the impact of this pandemic is likely to influence sport and leisure in the long term, longitudinal research is needed to understand and learn how to shape the industry moving forwards” (Manoli et al., Citation2022, p. 4).

Given the above, the purpose of the present study is to explore the impact of physical proximity on team cohesion in an elite sport context. By reaching its purpose, this study will contribute to the theoretical understanding of team cohesion and aid sport management scholars and practitioners in multiple ways. First, this research enhances the existing conceptual model for the study of team cohesion in sport, originally proposed by Carron (Citation1982), by adding physical proximity to its environmental factors, thereby advancing the model’s application to global pandemics such as COVID-19 as well as other times of physical distancing (e.g. off-season, remote teams).

In this context, it will be examined how team members (i.e. coaches and players) have remained in contact during the pandemic while adhering to social distancing guidelines. Consequently, what, and how various digital communication methods have impacted team cohesion within an elite sport team whilst being physically distant will be determined. By doing so, the extent to which digital communication tools can replicate or replace face-to-face interactions to maintain high levels of team cohesion can be identified and recommendations regarding the management of remote or physically distant (elite sport) teams can be offered.

As such, this study’s’ findings will build a reference point for sport management scholars and practitioners who might face episodes of physical distancing within their teams, be that during the off-season, as a result of a move towards more globalized remote teams, or within an eSport setting.

Theoretical background

Team cohesion

An important aspect of cohesion to consider is the ability of the group to stick together throughout a sport season. However, as Carron et al. (Citation1998) noted, team cohesion dimensions (i.e. Attraction to the Group (ATG), Group Integration (GI), Task Cohesion (T), Social Cohesion (S)) might not be present or salient at all points of time in a season (Eys et al., Citation2007). Wagstaff et al. (Citation2018) investigated cohesion-related behaviours within subgroups of a rugby team and established that athletes were aware of the subgroups across their team and, secondly, the social environment of the team played a key role in the formation of the subgroups and cohesion over time. While Wagstaff et al. (Citation2018) focused on the relationships between athletes and through subgroups of athletes, Jowett and Chaundy (Citation2004) examined the relationships between coaches and athletes, specifically a coach’s leadership behaviour influence on athlete task cohesion and social cohesion. The findings from Jowett and Chaundy (Citation2004) illustrated that a coach’s leadership behaviours had a greater positive influence on the task cohesion aspect of group cohesion when compared to social cohesion. Specifically, a coach’s leadership behaviours were more effective on influencing perceptions of team performance and playing strategy (Jowett & Chaundy, Citation2004). As such, both Jowett and Chaundy (Citation2004), as well as Wagstaff et al. (Citation2018) focused on team, personal, and leadership factors as potential antecedents of the cohesion components and did not consider the relevance of environmental factors in their line of research. To this end, even though these studies illustrate the dynamic nature of cohesion development as well as evidence for coaches, athletes, and groups of athletes to all have a significant influence on the development of cohesion, there is still a need for research investigating the impact of environmental factors, more specifically physical proximity.

Contrary to the positive results of the aforementioned studies, Leeson and Fletcher (Citation2005) found that perceived team cohesion (both T and S) decreased over time among female netball players during their season. As such, these results provide a cautionary note towards how cohesion may decrease on a sport team throughout their season. Although specific reasons for the decrease were difficult to surmise, the authors suggested that one potential reason may have stemmed from survey fatigue as they surveyed the team four times across a 10-week season.

Whereas Leeson and Fletcher performed their study at four time points within a season, Bosselut et al. (Citation2012) examined cohesion in youth sport at the mid-season and end-of-season points. Bosselut and colleagues integrated role ambiguity, as a reciprocal variable to team cohesion. Role ambiguity can be defined as the lack of clear information about the expectations linked to one’s position (Bosselut et al., Citation2012; Kahn et al., Citation1964). The results of Bosselut et al.’s (Citation2012) research illustrate that an important aspect of the reciprocal nature of role ambiguity and social cohesion was the relationships developed between team members at the midpoint of the season. Their observation emphasizes the importance of establishing high levels of social cohesion early in the season to foster greater role clarity going forward. Both studies (i.e. Bosselut et al., Citation2012; Leeson & Fletcher, Citation2005) further supported the conceptualization of team cohesion as a dynamic construct and established the need for future research to investigate how different (sport) teams and/or different age groups maintain group cohesion.

A final aspect of cohesion to mention with direct relation to the current study is linking cohesion to elite sport. Given the current context of elite sport, it would be remiss to not examine how previous research has provided a foundation for understanding cohesion in this context. Kjørmo and Halvari (Citation2002) found that in Norwegian Olympic athletes, group cohesion positively influenced group goal-clarity, which then positively influenced the performance by the athletes. Spink et al. (Citation2010) enhanced the understanding of cohesion in the elite sport context when they examined the relationship between cohesion and an athlete’s likelihood to return to an elite junior hockey team from one season to the next. Overall, Spink and colleagues (Citation2010) found those athletes who perceived their team’s cohesion to be high were the most likely athletes from the team to return for the next season.

Lastly, Damato et al. (Citation2011) discovered that individual-level aspects of high self-efficacy and high frequency of self-talk were positively associated with those individuals’ perception of group-cohesion, specifically, task-cohesion across nine professional men’s soccer teams. With these previous studies forming a foundation of cohesion in the elite sport context, this research draws on their findings to help position the present study in the literature. These studies help point towards the importance of both group and individual considerations of cohesion in the elite sport context, and that both levels can influence the performance of individuals and the group.

Conceptual model of team cohesion

Historically, research on cohesiveness in teams “has been dominated by confusion, inconsistency, and almost inexcusable sloppiness with regard to defining the construct” (Mudrack, Citation1989, p. 45). To address these shortcomings Carron and colleagues (Citation1985) suggested a multidimensional conceptual model (GEQ) that has subsequently guided the theoretical conceptualization and measurement of cohesion in sport teams (Carron & Brawley, Citation2012). Carron et al. (Citation1985) drew on group dynamics (Cattell, Citation1948; Zander, Citation1971) to operationalize team cohesion and their work represents the foundational theorising on team cohesion within sport.

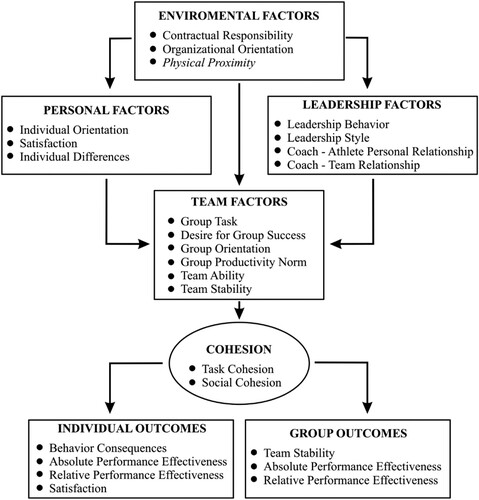

The conceptual model of team cohesion, upon which this study is build, was originally proposed by Carron (Citation1982) and this study’s adaption of it is visualised in . The depicted conceptual model in line with Carron (Citation1982) and Carron et al. (Citation1985) is comprised of antecedents (i.e. environmental factors, leadership factors, personal factors, and team factors), as well as outcomes (i.e. individual outcomes and group outcomes) of the team cohesion construct. It further distinguishes team cohesion into two central dimensions: Group Integration (GI) and Individual Attraction to the Group (ATG) (Carron et al., Citation1985). Whereas GI captures the individual’s perceptions of closeness, similarity, and unity within the group (Carless & De Paola, Citation2000), ATG reflects the individual’s personal feelings and motivations to remain in the group (Carron & Brawley, Citation2012; Widmeyer et al., Citation1985). Both dimensions (GI and ATG) can further be split into task (T) and social (S) subcomponents (Carron & Brawley, Citation2012). While the T subcomponent mainly captures beliefs around collective performance, goals and objectives, the S subcomponent emphasizes the relationships between individuals within the team (Carron & Brawley, Citation2012).

Figure 1. Adjusted conceptual system for cohesiveness in sport teams.

Note: Own illustration based on Carron (Citation1982, p. 131)

Carron (Citation1982) proposed that environmental factors have an impact on all other antecedents (i.e. personal factors, leadership factors, and team factors) placing them at the beginning of the conceptual system of cohesiveness. However, whereas Carron (Citation1982) proposed contractual responsibility as well as organizational orientation as two key environmental factors, this research adds physical proximity as a third environmental factor (see ).

The relevance of environmental factors, in general, and physical proximity has been reinforced by the COVID-19 global health pandemic (Manoli et al., Citation2022; Skinner & Smith, Citation2021) and depicts an important, but less explored pathway for further investigation in sport management. As such, this paper is interested in the environmental antecedents of team cohesion (both T and S) as they relate to physical proximity. provides a synthesized visual representation of the conceptualization of cohesiveness in sport teams based on Carron (Citation1982), highlighting the newly added physical proximity factor in italics, and environmental antecedents in light grey.

Managing work and teams through digitalization

Globally distributed and/or remote work teams have become progressively common, requiring managers to tailor their management style and organizations to emphasize commonalities between team members beyond being based in the same geographical location (Cramton, Citation2001; Garrison et al., Citation2010). However, this was not always the case; team members being bound to physical work locations has been normative behaviour in on-field sports given the nature of work requiring athletes, coaches, officials, fans, and other stakeholders being in the same place at the same time to co-produce the elite sport product (Chelladurai, Citation2014). But, the COVID-19 global health pandemic has significantly disrupted this normative requirement, and sport organizations have shifted to incorporate increased digital communication practices that ensure the maintenance of team cohesion (Naraine & Wanless, Citation2020).

Although digital tools are often perceived to be less rich in terms of stimulating a sense of belonging relative to face-to-face interactions, the manifestation of digital communities (e.g. social media) can breed such belonging, and amplify it (Naraine et al., Citation2020; Naraine & Parent, Citation2016). Video conference and live streaming have also been identified as an important digital tool with the capacity to overcome the limitations of reduced face-to-face interaction. As Atwater et al. (Citation2017) documented, video recordings are significant in forming a bond, especially when it pertains to learning and sharing. Furthermore, live streaming options (e.g. Zoom, Microsoft Teams) have provided greater flexibility to (digitally) interact with one another without navigating common logistical issues such as physically travelling to and to a place of physical interaction (Wymer et al., Citation2020). Thus, video interactions during COVID-19 have shifted the paradigm away from the status quo of face-to-face interaction to embracing digital interaction from the accommodating home environment (Mastromartino et al., Citation2020). However, digital communication as a means of alleviating the absence of physical interaction is not without its challenges. Grant et al. (Citation2013) highlighted difficulties in relationship building and/or maintenance in remote environments. Given this sentiment, an investigation to assess the extent to which virtual can replace in-person interaction in elite sport to maintain high levels of cohesion is warranted.

In line with Kayworth and Leidner (Citation2002), this research assumes that even though remote teams still face similar challenges as traditional teams, they are likely to also face some unique communication challenges which might inhibit the team’s ability to build trust (Jarvenpaa et al., Citation1998) and cohesion. Common challenges of remote work (i.e. lack of face-to-face supervision, social isolation, and distractions at home) have been highlighted by Larson et al. (Citation2020), however, their relevance to the elite sport context to date remains largely unexplored. By drawing on the work of Larson et al. (Citation2020), this study provides the opportunity to investigate the usability of digital tools for the maintenance of team cohesion in elite sport due to the physical distancing requirements of a global pandemic.

In summary, this study builds on the aforementioned research and argues that the COVID-19 pandemic depicts a unique opportunity to investigate how different subcomponents of team cohesion (i.e. S and T) may present themselves throughout a season with varying levels of physical proximity. Specifically, the impact that environmental factors may have on the level of team cohesion due to significant changes in physical proximity resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. By doing so, this research extends the work of Jowett and Chaundy (Citation2004) as well as Wagstaff et al. (Citation2018) by including environmental factors (i.e. physical proximity) through the theoretical application of the four cohesion dimensions of Carron et al. (Citation1985). As such, the study enhances the current understanding of environmental factors that may contribute to cohesion in an elite sport team context, by adding physical proximity to Carron et al.’s (Citation1985) conceptual model of cohesion.

Methods

This study asked to what extent physical proximity affects levels of team cohesion in an elite sport setting. We adhered to the definition of elite sport put forth by Sotiriadou and De Bosscher (Citation2017), that captured high performance and elite sport as those that encompass an athlete or team competing or aiming to compete at the national or international levels in their sport. This research question was broken down into two sub-questions:

S-RQ1: How does physical distancing, as a result of COVID-19, impact levels of team cohesion?

S-RQ2: How can digital communication tools replicate or replace face-to-face interactions to maintain high levels of team cohesion?

These questions were investigated using a single-case study convergent parallel design where both the qualitative and quantitative data were collected simultaneously, and the results were merged for comparison to interpret convergence or divergence with the data sets (Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2011; Skinner et al., Citation2014).

As shown in , the data collection occurred in three stages with equal priority given to both methods throughout the study, thus indicating the study followed a (QUAL + QUANT) ◊ QUAL ◊ (QUAL + QUANT) design (Morse, Citation1991). The research team utilized a pragmatic approach (Morgan, Citation2007), allowing the research team to mix methods to best answer the research questions (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, Citation2004). The rationale for using a mixed methods design was to strengthen the study through method and data triangulation (Denzin, Citation1978; Greene et al., Citation1989), and the research proceeded under the context that “all methods have inherent biases and limitations, so use of only one method to assess a given phenomenon will inevitably yield biased and limited results” (Greene et al., Citation1989, p. 256). Further, the use of multiple individuals in the qualitative data analysis phase provided the study with investigator triangulation (Denzin, Citation1978).

Participants

The participant pool for the study was comprised of players, coaches, and management staff from the USA Women’s Rugby Sevens team. Access to the participants was obtained through a research team member’s connection with the head coach. While access to the team was granted through a personal relationship with the head coach, the research team did not establish relationships with players, coaches, and management staff prior to the interview data collection to maintain proper interviewer and interviewee power dynamics (Seidman, Citation2013). After the study was approved by an institutional research ethics board, consent was obtained from each participant before they participated in the study. All respondents were encouraged to participate in both the surveys and interviews and were informed by the head coach that choosing not to participate in the study would not affect their standing within the team (e.g. playing time). Players that participated in the study had varying tenures with the team, ranging from eight years to less than one year. Coaching staff and management were not apprised of which players completed surveys and interviews to maintain confidentiality through each stage of the data collection.

Rugby Sevens is a unique lens to view the effects of physical proximity on team cohesion. Once COVID-19 abruptly halted the regular practice and tournament schedules, USA players and staff were required to practice social distancing at the team’s training centre in Chula Vista, California. At the time of the initial social distancing order, the remainder of the 2020 schedule – including the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympic– was still in flux and the team continued to prepare for tournament play in the event that competition would resume. Adaptions were made to the players’ physical training regimen that included more individual workouts in the first weeks, followed by the formation of small groups that would participate in on-field sessions thereafter. Unless team members lived with each other or were grouped together for smaller training sessions, social interaction was limited or non-existent to maintain social distancing guidelines.

Quantitative data collection and analysis

Data were collected at two time points (T1S = September 2019; T2S = August 2020) via the 18-item GEQ instrument in line with the theoretical foundation of this research. Each of the items was scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) to capture the respondent’s agreement with the respective statement. In line with Carron et al. (Citation1985), nine items (i.e. ATG) aimed to assess the respondent’s feelings about their personal involvement with the team. Exemplary statements included “some of my best friends are on this team” and “this team does not give me enough opportunities to improve my personal performance”. Whereas the second set of nine items (i.e. GI) were tailored towards the individual’s perceptions of the team as a whole. Example statements of these items included “our team is united in trying to reach its goals for performance” and “our team would like to spend time together in the off-season”. Congruent to Mathieu et al. (Citation2015) and the original GEQ instrument by Carron et al. (Citation1985) further differentiation into social (S) and task (T) related subcomponents was applied.

Internal scale reliability was achieved for the two GI sub-scales of the cohesion construct in T1S (αGI-T1 = 0.67; αGI-S1 = 0.74), whereas Cronbach’s Alpha values for the two ATG sub-scales did not meet desired reliability levels at both points of data collection (αATG-T1 = 0.56; αATG-T2 = 0.60; αATG-S1 = 0.61; αATG-S2 = 0.41). Given the low scale reliability of the ATG-S subscale the scale was dropped from further analysis. Low reliability scores of the ATG-S subscale are a known challenge in team cohesion research and Prapavessis and Carron (Citation1996) as well as Westre and Weiss (Citation1991) similarly reported Cronbach’s alpha values of below 0.60 for the ATG-S dimension. In order to meet the required scale reliability thresholds for the ATG-T subscale at both timepoints, the GEQ2 item “I am not happy with the playing time I get” was dropped from the scale yielding acceptable values of αATG-T1 = 0.73 and αATG-T2 = 0.61.

Due to the competitive nature of Olympic-level rugby, players are sometimes released or sent down to the developmental team – and vice versa – players are brought up and signed contracts with the topflight team. This inherent phenomenon of turnover resulted in 22 matched samples to be analysed for the study. Paired t-tests are known to be robust with sample sizes under 30 and in line with De Winter (Citation2013) and Campbell et al. (Citation1995), the N = 22 matched samples within this study were considered appropriate for statistical analysis.

After the two surveys were administered via the BOS online survey platform, data were cleaned, and negatively worded items (12 in total) were reverse coded. Subsequently, the data were imported into SPSS an analysed via bootstrapped dependent paired t-tests, utilising a 95% confidence interval (Dwivedi et al., Citation2017). Descriptive statistics (i.e. cohesion sub-scale means) were run to familiarize the research team with the data, and bootstrapped dependent sample paired t-test were executed to test for significant differences between the two time points.

Qualitative data collection methods and analysis

In line with a convergent parallel single-case study research design, semi-structured interviews were conducted over the duration of the season to get a more nuanced understanding of changes on the individual level potentially not captured in the quantitative data. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 17 players, 1 staff member, and 1 head coach over three different time periods (T1I September 2019, N = 8; T2I March 2020, N = 6, T3I June 2020, N = 5) using an interview guide (Patton, Citation2015). The interview guide was developed by placing the research questions as the central focus and formulating questions centred on understanding personal accounts of team cohesion, contributing factors to fluctuations in team cohesion, and digital communication strategies employed by the team to maintain and enhance cohesion. Critical studies in the team cohesion literature (e.g. Carron et al., Citation1985; Citation1998) also served as building blocks for interview questions. Further, given that interviews were conducted at various time points that coincided with unique stages of the pandemic and changes to the status of training and competition, additional questions were added to the interview guide to reflect these nuances. All 19 participants were interviewed once at one of the three timepoints of the data collection. Interviews were conducted with two members of the research team present, with one member leading the interview and the other member present for note-taking and follow-up questions (Patton, Citation2015). Interviews were conducted over Zoom and transcribed verbatim. All interview transcripts were then imported to NVivo 12. Subsequently, two members of the research team began both deductive and inductive coding techniques prescribed by Miles et al. (Citation2020).

Deductive coding involves the research team creating a list of a priori codes (e.g. factors that influence cohesion, current level of cohesion) based on the extant literature and contextual knowledge (Miles et al., Citation2020). Next, inductive coding was performed through rounds of open coding (e.g. descriptive and concept), pattern coding (e.g. categories and relationships), and generating meaning through emergent themes (Miles et al., Citation2020). After the two members of the research team engaged in this process, they merged their themes to form the final qualitative themes. Throughout both the deductive and inductive coding rounds, the two researchers compared their individually coded interviews (each researcher coded the same interview) to establish intercoder reliability (Creswell, Citation2012). To establish clarity in each person’s codebook, illustrative examples were detailed by each person to show how each code was operational in the context of the current study (e.g. indicators of cohesion – “Respect of the opportunity. Respect of each other. Respect of the space, the job. We talk a lot about who and what we represent when we become a member of the US national team”). During the comparison stage, any differences in coding were discussed based on each researcher’s interpretation until coming to an agreement. The researchers then coded another interview separately and again discussed the interpretations through a comparative analysis. Once coding was completed, the codes were then collapsed into emergent themes (Creswell, Citation2012).

Results

To provide more nuanced analysis, the qualitative results were used to provide details to the three dimensions of the quantitative GEQ survey (i.e. ATG-T, GI-S, and GI-T). This technique of merging the analyses assisted the research team in analysing the sub-dimensions of the GEQ survey with the themes derived from the qualitative thematic analysis for a deeper interpretation of the overall data set on both and individual and a team level (Damato et al., Citation2011; Fetters et al., Citation2013).

Quantitative results

Results of the bootstrapped paired t-tests test for the three cohesion dimensions (i.e. ATG-T, GI-S, GI-T) are presented in . With all p-values being larger than .05, it can be concluded that team cohesion levels were maintained throughout extended episodes of physical distancing on a team level. More specifically, feelings of unity and closeness on both task and social dimensions, expressed in GI-S and GI-T, as well as the attraction of individual athletes to the group task, expressed in ATG-T, remained stable.

Table 1. Bootstrapped dependent paired t-tests of cohesion dimensions.

As no statistically significant change between T1S to T2S could be observed the focus within the results section as well as the subsequently following discussion will be on the qualitative part of the study.

Qualitative results

This section discusses the qualitative results under the emergent themes that were created from the data.

Tasks and collective loyalty

The first round of interviews was conducted with players that had the most tenure in the team, and they were able to contrast the current coaching staff with previous ones. The team experienced frequent turnover in the coaching staff prior to the study, with one senior player noting “[this is] the first time in six years that we’ve had a coach for a full year”. Players referred to the previous coaching style as “very, very harsh” and that the coach “always made you very aware that you were replaceable.”

These factors precipitated into what players described as poor team culture driven by a lack of transparency and instances where the coaching staff “would bad mouth players to other players”. Due to this environment, a reset of team culture and values was instituted by the current coaching staff, resulting in focusing in on the “why” of the team, and the development of shared ideals, values, and purpose that became the broad driving force for the team.

One of the players noted, “we emphasize culture so much that it's almost in our head all the time”. Players attributed aspects of this shift to regular team meetings that emphasised a safe space to discuss team culture, as a player described: “We have weekly meetings that we call BRAVE meetings, and we discuss our culture and what it means to represent the country and play for this team”. In the second and third round of interviews with players of less tenure, many participants suggested indicators of team cohesion as developing and working toward a common goal as a team (see ).

Table 2. Qualitative themes.

This was broken down by one player and one staff member into “understanding the team’s mission and purpose” and then “working toward that goal”. For one player, this meant understanding the common goal in a tactical sense and “making sure we are on the same page for attack and defensive framework”. Two players indicated that while having a shared understanding of a common goal was important, ensuring team members work hard toward that goal was central to feeling the team was cohesive. The majority of participants that indicated common goals as a builder of team cohesion spoke of it in an idealised sense, rarely connecting the idea to an actual tangible goal. One team member, though, spoke to the common goal of “we're all here because we want a podium at the Olympics, or we’re all here because we want to win gold” as the underlying common goal that the team formed cohesion around.

As for the group task cohesion dimensions (GI-T), participants indicated that the team functions with a high level of cohesion when players understand what their role is within the team and appreciate that their role translates into “everyone doing their job”. They also shared that putting the team first was important to develop and sustain a high level of cohesion. One player disclosed that while the team undoubtedly has “stars” on the roster, “they don't get themselves all the spotlight … It’s kind of like everybody does their role, which allows, you know, [to] be cohesive because there isn't one person who's trying to shine above everybody else”.

Another player described the day-to-day grind of training that resulted in cohesion among the team: “It’s in those like dark moments as well of training when you can look to your left and right and know it’s these girls who are doing the hard yards with you”. In this sense, the team had moved from being driven by macro goals of mission and purpose in the early interviews and found cohesion in the execution of micro, day-to-day tasks that built up collective loyalty.

Resilience through social cohesion

In the first round of interviews before the pandemic – with players of longer tenure – many described the propensity for cliques to form within the team under the previous coaching tenure. One player described how this permeated into social contexts off the field: “They don’t really branch out to try to, you know, get to know other people on the team. They kind of just like, these are my friends, these are the people I'm going to hang out with”. A contributing factor that players mentioned was the difference in backgrounds and life experiences among the players, as one participant described:

I find that on the international team with all of us with different backgrounds and different ages and stuff like that, [it] can be a little bit more difficult to maybe be super cohesive, just cause you're in different stages of your life.

While these differences sometimes served as initial roadblocks to cohesion in a social sense, other players (see ) returned to achieving common goals as a uniter, which was a motivator to move past those differences and find common ground off the rugby pitch. The practice of self-disclosure and vulnerability expressed during the team’s BRAVE meetings also began to transfer from the pitch into social cohesion.

Participants routinely noted that personal connection (individual level) and spending time together (team level) were builders of team cohesion. Even with the absence of physical contact to continue building cohesion, team members and staff indicated that the level of team cohesion during physical distancing was, at the very least, maintained during the crisis, which was confirmed through the quantitative results on a team level (see ). Building cohesion over time appeared to provide enough strength that team members felt unified even without seeing each other as an entire unit.

Other members of the team stated that the crisis had strengthened the team’s cohesion, which is reflected in some individuals higher scores on the cohesion dimension in T2S. One contributing factor to perceived higher levels of social cohesion was that the smaller pods of players were spending more time with each other, and team members were developing relationships with players that they otherwise would not have before physical distancing, as one player noted:

I honestly feel like [a] little more connected, because we've been like, some people who live near each other, we've been working out together. Um, and like some of them were people like I never would have like really hung out with outside of us being at the training centre.

Therefore, some players felt that they formed a common bond through crisis with other members on the team. In other words, the COVID-19 crisis served as an opportunity for team members to express empathy with each other and rally around the commonality of a less than desirable situation. For one player, they viewed the crisis through a lens where it stripped down barriers or guards that people may have had previously: “I think cohesion wise, it’s kind of cool because it’s a vulnerable space to be in and we’re all experiencing it whether it’s an introvert or extrovert”.

Thus, in conclusion qualitative insights obtained through the interviews, indicate that individual athletes either felt that levels of team cohesion were maintained throughout episodes of pandemically enforced physical distancing, or that in especially GI-S had increased due to shared experiences and high levels of interaction within small groups of individuals. While almost all participants viewed positive aspects to interactions with the smaller pods, by the last round of interviews players were yearning for a return to normality and the ability to interact with the larger group in a traditional sense. Team members that indicated the level of team cohesion had plateaued felt that once the team was able to resume “normal” activities, team cohesion would return to pre-pandemic levels. Benefits were derived from the smaller pod settings, and coaches seeking to form social bonds with teammates less likely to interact naturally may seek to implement this tactic in small doses.

Digital engagement replacing face-to-face interaction

After the team was mandated to enact physical distant protocols, the coaching staff turned to digital platforms to facilitate group interaction. Zoom was used for official team meetings, in-depth reflection sessions, and social activities arranged by the coaching staff. The coaching staff utilized these meetings on Zoom to not only provide updates on the fluid situation of training and competition, but also divide the team into small breakout groups and created discussion topics that prompted team members to have conversations around personal topics that required self-disclosure. The meetings on Zoom were the only time when the whole team could “meet”, which was an important outlet for many team members.

To complement the more formal team meetings, the coaching staff arranged multiple social gatherings on Zoom as a way for the team to interact informally through “happy hours” and cooking competitions. Players noted that even though they were all cooking in separate spaces, they felt connected as a group, as one player stated: “We also did a team cooking event, which was another way for us to hang out and talk to each other. We’re finding a lot of ways to still stay in contact with each other even though it’s not physical”.

Additionally, the coaching staff kept in contact with players through social media and provided them with various workouts as one player described: “He sends us all like different skills things to do like he'll tag us on Instagram videos and stuff like that. So, I think that's like a good way to keep us like prepared and getting ready for like the next season.” The coaching staff was able to achieve multiple goals through the social activities and social media training videos: They were able to provide both relevant training and instruction and social support to the players through creative modes.

However, during the last round of interviews in the study (T3I), participants did note that the initial novelty of the social gatherings online was beginning to wear off, which could have been a combination of anticipation of when the team would be able to return to practice and tournament play, and a level of “Zoom fatigue”. One player described the collective group response to more digital meetings as, “ughhh, we have to do a zoom call”. Further, when players were asked a follow-up question about whether a digital medium (i.e. FaceTime) could replace in-person interactions responded, the consensus was that digital engagement was complimentary, but not able to replace it. One player noted that “nothing can replace wrapping your arms around somebody, ya know?” Similarly, another player responded,

I don't think it can replace it. I don't think like having somebody in front of you and like feeling their energy and, you know, looking them directly in the face not through a screen. You know, I think that you can't replace that with technology.

On an interpersonal level, the most prevalent method for players to mimic face-to-face interaction with players outside of their small group was through FaceTime. The use of FaceTime became more important for players after some had returned home following the cancellation of the 2020 season and Tokyo Olympic Games. As one player pointed out, “everybody’s a FaceTime call away so it’s not too bad”. FaceTime interaction was common between players that had formed connections before physical distancing, but players did not indicate that it was used to develop new relationships and engaging with unfamiliar teammates would be awkward. One player shared: “[it’s] a bit harder to connect individually and continue to grow the relationships that like weren't necessarily there before … I would FaceTime people that I'm close with but not people that I'm not close with or message them”.

Social media platforms were also utilized by players to help with sustaining connection, with the most popular being Instagram. Players shared that they regularly would send each other “funny photos” and other content to create touchpoints with each other. Another form of digital engagement that players employed was forming a book club, podcast club, and movie club. It appears the collective of digital platforms discussed in this section had a summative effect on maintaining team cohesion. Different platforms lent themselves to different purposes of interaction (i.e. Zoom happy hours for sustained interaction; Instagram for smaller touch points) and may serve coaches and teams uniquely depending on the cohesion building/maintaining needs.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine how physical distancing impacted team cohesion in an elite sport setting, while also determining if and how digital communication tools could replicate face-to-face interactions to support a high level of team cohesion. Further, this study examined team cohesion through different stages of physical distancing; an aspect that was particularly prudent given the dynamic nature of team cohesion and COVID-19 (Manoli et al., Citation2022; Smith & Skinner, Citation2022).

Physical proximity and team cohesion

Overall, findings illustrated that if opportunities for remote social interaction, such as digital communication (e.g. Zoom), digital social activities (e.g. happy hour, cooking event), and social media exchange (e.g. FaceTime, Instagram) are utilised within an elite sport setting the level of team cohesion can remain stable throughout episodes of physical distancing (Larson et al., Citation2020). As highlighted by participants, self-regulation and execution of team roles were a leading factor for the team to “work smoothly” which is consistent with the findings reported by Anderson and Dixon (Citation2019). Beyond identification and execution of roles, two-way trust of teammates to do their job on the field was an indicator of the team functioning as a cohesive unit. This observation extends the work of Abrantes et al. (Citation2020), who emphasize the relevance of trust in the coach as a moderator of team cohesion.

Quantitative results show that the team was able to maintain their previous level of team cohesion on all three cohesion subscales (i.e. ATG-T, GI-S, GI-T) despite extended periods of physical-distancing, postponement of the Tokyo Olympic Games, and disruption to their competitive season schedule as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, it is important to note that the maintenance of team cohesion during times of physical distancing is largely affected by previously established levels of social cohesion and identification of and with roles.

Given these findings, it could be suggested that teams with higher levels of social cohesion and clearer role assignment are more resilient to crisis situations and are better able to cope with extended periods of physical distancing. Put differently, the impact of physical proximity as an environmental factor of team cohesion is mediated through role assignment captured within the team factor of the conceptual framework of cohesiveness in sport teams (cf. Carron, Citation1982; ). Resilience to crisis, therefore, could be seen as a group outcome variable within the cohesion model, impacted by social cohesion levels, role assignment, and physical proximity.

Digital engagement and face-to-face interaction

Although digital engagement has temporarily filled the void of physical interaction and connection amongst the team, the majority of team members were explicit in that digital engagement could not fully replace face-to-face interaction long-term and ideally should only complement it. As such, physical proximity should be a key factor when selecting appropriate communication strategies to foster or maintain cohesion within elite sport settings. Both digital as well as face-to-face communication strategies have their unique strength and weaknesses and are suited for different levels of physical proximity (Kayworth & Leidner, Citation2002).

Congruent with the literature (cf. Atwater et al., Citation2017; Naraine et al., Citation2020), the importance of digital communication tools to elite athletes during episodes of social distancing were identified. Breakout sessions on Zoom allowed for smaller groups to connect on a deeper level than was accustomed to with face-to-face interaction. However, limitations of digital communication tools (Grant et al., Citation2013) were also emphasized by the players. Physical touch (i.e. hugging) and the nonverbal comforts of someone’s “energy” and “looking them in the eye” were highlighted as elements digital mediums were not able to replicate, even though “keeping up” with a team member’s day-to-day life was attainable. As such, the present findings suggest a balanced approach to both face-to-face and digital communication might provide the best strategy to foster team cohesion throughout a season. That is, digital and face-to-face interaction should be considered as complementary and not in isolation from each other. Put differently, even during episodes where physical proximity is given and face-to-face interactions are the domineering communication strategy, opportunities for digital communication should still be utilised to harness the above-described benefits.

Further, the social events arranged by the coaching staff became less common as the pandemic restrictions loosened and meetings on Zoom were reduced as smaller groups of players returned to training. The level of connection participants spoke of when describing interaction through digital engagement versus face-to-face interactions in their smaller groups showed a true dichotomy in the limitations of digital engagement that went beyond the general challenges of remote work highlighted by Larson et al. (Citation2020). Participants noted the absence of tactile connection and the feeling of “forced” social interaction accompanied by the digital engagement that was experienced less in informal face-to-face settings (cf. Grant et al., Citation2013; Kayworth & Leidner, Citation2002). While most participants were supportive of supplementing regular digital interactions with digital social events and activities, multiple team members indicated that they do not think these types of activities will continue once the team returned to regular in-person training and their usual seasonal schedule. These positive player perceptions of coach-lead digital bonding activities contradict the findings of Anderson and Dixon (Citation2019), who emphasized that coach-led activities were perceived as forced and generally negative. Thus, it could be suggested that players during times of physical distancing are more open to coach-led activities and/or that digital engagement, as opposed to face-to-face interaction, provided the perception that digital bonding activities were less forced.

In addition, given that players have been with the team for varying amounts of time, and as demonstrated by Abrantes et al. (Citation2020), tenure influences team cohesion. Selected players may not have had the chance to form strong bonds with their teammates before physical distancing. Thus, those players might have lower perceptions of team cohesion are less inclined to embrace digital tools as a means to build team cohesion.

Theoretical implications

The previous discussion of empirical results in conjunction with the literature review build the foundation for this section summarising the theoretical implications. First, whereas the majority of previous team cohesion research in an elite sport setting investigated the impact of cohesion on group outcomes such as performance (Kjørmo and Halvari, Citation2002), or individual outcomes like the probability of players to return for the next season (Spink et al., Citation2010), this research offers new knowledge regarding the antecedents of team cohesion. It does so by extending the work by Jowett and Chaundy (Citation2004) as well as Wagstaff et al. (Citation2018) to incorporate environmental factors as an important and less explored antecedent of team cohesion in elite sport.

Even though both Jowett and Chaundy (Citation2004) as well as Wagstaff et al. (Citation2018) investigated antecedents of cohesion in a sporting context, they focused on team, personal, and leadership factors and did not consider the relevance of environmental factors in their line of research. As such the present research was the first study to empirically investigate the importance of environmental factors for maintaining team cohesion in an elite sporting context throughout a season.

Third, and perhaps most notably, the conceptual model of team cohesion in sports, originally proposed by Carron (Citation1982), has been made more contemporary by incorporating physical proximity as an important environmental factor of cohesion. More specifically, findings suggest that the impact of physical proximity as an environmental factor of team cohesion is mediated through role assignment, and that resilience to crisis appears to be impacted by social cohesion levels, role clarity, and physical proximity (cf. Bosselut et al., Citation2012; Kahn et al., Citation1964).

As such present findings from the elite sport context regarding the importance of role clarity are in line with observations made by Bosselut et al. (Citation2012) for a youth sport setting. Similarly, the importance of establishing relationships early in the season to maintain social cohesion levels (cf. Bosselut et al., Citation2012) were further emphasised and can be regarded particularly important for episodes of physical distancing.

Finally, reviewing the relevance of findings from Grant et al. (Citation2013) as well as Larson et al. (Citation2020) for an elite sport context led to the emergence of new knowledge regarding the ability of digital communication to replace face-to-face interactions during episodes of physical distancing. That is, as suggested by Larson et al. (Citation2020) for a business context, providing different and “richer” communication technology options, such as video conferencing is temporarily suitable to maintain team cohesion in an elite sport setting. However, even “richer” communication technologies can not fill the void of face-to-face interactions long-term in an elite sport context. As such, the benefits of digital interactions, such as avoiding logistical issues, shorter travel, and greater flexibility (cf. Mastromartino et al., Citation2020; Wymer et al., Citation2020), did not outweigh the value of in-person interactions for participants in this study.

Managerial implications

Practitioners and managers of elite sport teams are encouraged to draw on best practice for the management of remote work teams (cf. Larson et al., Citation2020) and adapt those to fit their specific context. By doing so, they are more likely able to ensure levels of team cohesion remain stable or even increase during times of physical distancing. Additionally, in order to utilize the importance of digital communication tools, it is recommended that sport managers utilize digital instruments (e.g. Zoom, Instagram, FaceTime) to supplement face-to-face interactions.

Moreover, to enhance the resilience of their team’s overall level of cohesion, sport managers are encouraged to create a shared vision and facilitate clear role assignment early in a team’s life cycle, this will provide a sound foundation to maintain team cohesion in periods of physical distancing (cf. Bosselut et al., Citation2012). This study has shown that it takes time to develop and solidify team cohesion, consequently, sport managers are urged to consider a team’s development as an important moderator of the impact of environmental factors and other antecedents on team cohesion (Abrantes et al., Citation2020; Marks et al., Citation2001; Mathieu et al., Citation2015). While the environmental factors in this study pertained to a pandemic and the integration of digital communication, other settings investigating cohesion should heed the individual contextual factors that may offer a more nuanced explanation of the team cohesion model (Carron et al., Citation1985).

Sport managers should explore other ways of physically distant relationship building, such as digital social events (e.g. cooking, happy hours, break out groups), during pandemic as well as non-pandemic times. As such digital communication methods (i.e. Instagram, FaceTime, Zoom) can be used in a more innovative way during times of physical distancing, to maintain levels of cohesion. These methods should especially cater for team members who have a shorter organizational tenure and feel a lower level of belongingness to the team during times of physical distancing (cf. Abrantes et al., Citation2020). In addition, players with shorted tenures should where possible live with players having longer organizational tenures to enable them to continue training together even in the case of pandemically enforced social distancing requirements. These living arrangements would enable a combination of limited physical face-to-face interactions within small groups whilst digital engaging with the rest of the team, in pandemic times. In general, coaches are advised to, were possible and safe to do so, consider an early return to socially distant training in small groups to address limitations of purely digital communication between team members. Finally, as scholars and practitioners have gained a better understanding of social distancing protocols and policies throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the communication with individual players and teams can be made more effective, utilising were possible both digital and face-to-face interactions, in case of another global health crisis.

Limitations and future research

Despite its strength, this study is not without limitations frequently apparent in team cohesion research. More specifically, the low Cronbach’s alpha values of some of the cohesion dimensions (i.e. ATG-S and ATG-T) raised concerns regarding the scale reliability of the GEQ and let to the modification (i.e. ATG-T) and removal (ATG-S) of the respective cohesion dimensions. As indicated previously, mixed scale reliability of the GEQ is a known challenge in team cohesion research and as such findings of the present study are in line with previous research that have reported low scores of internal reliabilities especially of the ATG-S sub-scale (see e.g. Prapavessis & Carron, Citation1996; Westre & Weiss, Citation1991). That said, the validity of the GEQ instrument has a strong theoretical framework and its validity has been repeatedly demonstrated across various studies (Carron et al., Citation1998; Li & Harmer, Citation1996).

Qualitatively, not all players and staff were interviewed during the three interview time points, which limits the scope of input and experiences across the team. Further, as team members were only interviewed once, perceptions of the impact of COVID-19 on team cohesion was limited to the 11 participants interviewed during the pandemic. Notwithstanding these limitations, this study provided the basis for future research on elite sport teams’ transition post-COVID-19.

First, researchers can use insights from this study to explore whether digital technologies can be used by elite sport as well as remote teams to maintain or build team cohesion. The ability for team members to stay connected remotely could assist during off-seasons or longer periods away from a team setting as a consequence of geographical location. Next, while this study examined an elite women’s rugby team, future research would be well served to examine elite men’s teams. In particular, future research may be able to determine if any gender or sport-specific aspects are evident in building or maintaining team cohesion longitudinally.

Additionally, this study examined changes in one team’s cohesion levels taking varying degrees of physical proximity as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic into account. While other crises are unpredictable, future research can aim to capture whether low or high levels of team cohesion influence how a team handles a similar crisis situation. The findings of this study suggest that a high level of team cohesion can be maintained during pandemically enforced physical distancing; however, the results should not be generalized to other periods of physical distancing (e.g. off-season, remote teams) without further investigation.

Another future opportunity exists to build on the work of Bruner et al. (Citation2014), Senécal et al. (Citation2008), as well as Widmeyer and Ducharme (Citation1997) to better understand the relationship between team cohesion and goal attainment in light of varying degrees of physical proximity. The participants in this study qualitatively identified winning an Olympic gold medal as a potential binding agent for cohesion, and the formation of a goal and progress a team makes toward attaining or missing a goal would be useful both theoretically and practically.

Finally, future research can examine the methods by which team cohesion is assessed and studied. Despite growth in the team cohesion research (e.g. Burke et al., Citation2014; Carron et al., Citation1985; Carron & Brawley, Citation2012; Loughead et al., Citation2016), ambiguity in its conceptualization and measurement persists. Future research can determine how quantifying interactions among participants during live sessions, such as with sociograms or social network analysis, adds further insight into team cohesion levels in elite sport.

Concluding comments

This study added physical proximity as an environmental factor to the theoretical conceptualization of team cohesion in sports originally established by Carron (Citation1982). The modified model (see ) is considered more contemporary and meaningful for sport management scholars and practitioners considering an increase in episodes of physical distancing within a sporting context (i.e. off-season, remote teams, COVID-19 Pandemic). In addition, this study emphasised that digital engagement can only temporarily fill the void of physical interaction within elite sport teams. As such, digital communication cannot and should not fully replace face-to-face interactions in elite sport settings long-term as it is less suited to form new relationships between team members.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ben Corbett, Chris Brown of USA Rugby, Keegan Dalal, Brock University, and Lindee Declerq, Brock University.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abrantes, A. C., Mach, M., & Ferreira, A. I. (2020). Tenure matters for team cohesion and performance: The moderating role of trust in the coach. European Sport Management Quarterly, 22(3), 313–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2020.1784247

- Anderson, A. J., & Dixon, M. A. (2019). How contextual factors influence athlete experiences of team cohesion: An in-depth exploration. European Sport Management Quarterly, 19(3), 353–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2018.1527381

- Atwater, C., Borup, J., Baker, R., & West, R. E. (2017). Student perceptions of video communication in an online sport and recreation studies graduate course. Sport Management Education Journal, 11(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1123/smej.2016-0002

- Bosselut, G., McLaren, C. D., Eys, M. A., & Heuzé, J.-P. (2012). Reciprocity of the relationship between role ambiguity and group cohesion in youth interdependent sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 13(3), 341–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.09.002

- Brisimis, E., Bebetsos, E., & Krommidas, C. (2018). Does group cohesion predict team sport athletes’ satisfaction? Hellenic Journal of Psychology, 15(1), 108–124.

- Bruner, M. W., Eys, M. A., Wilson, K. S., & Côté, J. (2014). Group cohesion and positive youth development in team sport athletes. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 3(4), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000017

- Burke, S. M., Davies, K. M., & Carron, A. V. (2014). Group cohesion in sport and exercise settings. In M. R. Beauchamp & M. A. Eys (Eds.), Group dynamics in exercise and sport psychology (2nd ed., pp. 147–163). Routledge.

- Campbell, M. J., Julious, S. A., & Altman, D. G. (1995). Estimating sample sizes for binary, ordered categorical, and continuous outcomes in two group comparisons. BMJ, 311(7013), 1145–1148. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.311.7013.1145

- Carless, S. A., & De Paola, C. (2000). The measurement of cohesion in work teams. Small Group Research, 31(1), 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/104649640003100104

- Carron, A. V. (1982). Cohesiveness in sport groups: Interpretations and considerations. Journal of Sport Psychology, 4(2), 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsp.4.2.123

- Carron, A. V. (1988). Group dynamics in sport. Spodym.

- Carron, A. V., & Brawley, L. R. (2000). Cohesion: Conceptual and measurement issues. Small Group Research, 31(1), 89–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/104649640003100105

- Carron, A. V., & Brawley, L. R. (2012). Cohesion: Conceptual and measurement issues. Small Group Research, 43(6), 726–743. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496412468072

- Carron, A. V., Brawley, L. R., & Widmeyer, N. W. (1998). The measurement of cohesiveness in sport groups. In J. L. Duda (Ed.), Advances in sport and exercise psychology measurement (pp. 213–226). Fitness Information Technology.

- Carron, A. V., Colman, M. M., Wheeler, J., & Stevens, D. (2002). Cohesion and performance in sport: A meta analysis. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 24(2), 168–188. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.24.2.168

- Carron, A. V., Widmeyer, W. N., & Brawley, L. R. (1985). The development of an instrument to assess cohesion in sport teams: The group environment questionnaire. Journal of Sport Psychology, 7(3), 244–266. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsp.7.3.244

- Cattell, R. B. (1948). Concepts and methods in the measurement of group syntality. Psychological Review, 55(1), 48–63. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0055921

- Chelladurai, P. (2014). Managing organizations for sport and physical activity: A systems perspective (4th ed.). Taylor & Francis.

- Cramton, C. D. (2001). The mutual knowledge problem and its consequences for dispersed collaboration. Organization Science, 12(3), 346–371. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.12.3.346.10098

- Creswell, J. W. (2012). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage.

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L.. (2011). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research (2nd). Sage.

- Damato, G., Heard, P., Grove, J., & Eklund, R. (2011). Multivariate relationships among efficacy, cohesion, selftalk and motivational climate in elite sport. Pamukkale Journal of Sport Sciences, 2(1), 6–26.

- Denzin, N. K. (1978). The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- De Winter, J. C. (2013). Using the student’s t-test with extremely small sample sizes. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 18(10), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.7275/e4r6-dj05

- Dwivedi, A. K., Mallawaarachchi, I., & Alvarado, L. A. (2017). Analysis of small sample size studies using nonparametric bootstrap test with pooled resampling method. Statistics in Medicine, 36(14), 2187–2205. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.7263

- Eys, M. A., & Carron, A. V. (2001). Role ambiguity, task cohesion, and task self-efficacy. Small Group Research, 32(3), 356–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/104649640103200305

- Eys, M. A., Carron, A. V., Bray, S. R., & Brawley, L. R. (2007). Item wording and internal consistency of a measure of cohesion: The group environment questionnaire. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 29(3), 395–402. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.29.3.395

- Fetters, M. D., Curry, L. A., & Creswell, J. W. (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48(6), 2134–2156. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12117

- Fransen, K., Van Puyenbroeck, S., Loughead, T. M., Vanbeselaere, N., De Cuyper, B., Broek, G. V., & Boen, F. (2015). The art of athlete leadership: Identifying high-quality athlete leadership at the individual and team level through social network analysis. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 37(3), 274–290. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2014-0259

- Garrison, G., Wakefield, R. L., Xu, X., & Kim, S. H. (2010). Globally distributed teams. ACM SIGMIS Database: The DATABASE for Advances in Information Systems, 41(3), 27–48. https://doi.org/10.1145/1851175.1851178

- Golembiewski, R. T. (1962). The small group: An analysis of research concepts and operations. University of Chicago Press.

- Grant, C. A., Wallace, L. M., & Spurgeon, P. C. (2013). An exploration of the psychological factors affecting remote e-worker’s job effectiveness, well-being and work-life balance. Employee Relations, 35(5), 527–546. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-08-2012-0059

- Greene, J. C., Caracelli, V. J., & Graham, W. F. (1989). Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 11(3), 255–274. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737011003255

- Güllich, A., & Emrich, E. (2006). Evaluation of the support of young athletes in the elite sports system. European Journal for Sport and Society, 3(2), 85–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2006.11687783

- Hambrick, M. E., Schmidt, S. H., & Cintron, A. M. (2018). Cohesion and leadership in individual sports: A social network analysis of participation in recreational running groups. Managing Sport and Leisure, 23(3), 225–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2018.1554449

- Jarvenpaa, S. L., Knoll, K., & Leidner, D. E. (1998). Is anybody out there? Antecedents of trust in global virtual teams. Journal of Management Information Systems, 14(4), 29–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.1998.11518185

- Johnson, R. B., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher, 33(7), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X033007014

- Jowett, S., & Chaundy, V. (2004). An investigation into the impact of coach leadership and coach-athlete relationship on group cohesion. Group Dynamics, 8(4), 302–311. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2699.8.4.302

- Kahn, R. L., Wolfe, D. M., Quinn, R. P., Snoek, J. D., & Rosenthal, R. A. (1964). Organizational stress: Studies in role conflict and ambiguity. Wiley.

- Kayworth, T. R., & Leidner, D. E. (2002). Leadership effectiveness in global virtual teams. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(3), 7–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2002.11045697

- Kjørmo, O., & Halvari, H. (2002). Two ways related to performance in elite sport: The path of self-confidence and competitive anxiety and the path of group cohesion and group goal-clarity. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 94(3), 950–966. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.2002.94.3.950

- Larson, B. Z., Vroman, S. R., & Makarius, E. E. (2020, March). A guide to managing your (newly) remote workers. Harvard Business Review, March, 1–6. https://hbr.org/2020/03/a-guide-to-managing-your-newly-remote-workers

- Leeson, H., & Fletcher, R. B. (2005). Longitudinal stability of the group environment questionnaire with elite female athletes. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 9(3), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2699.9.3.147

- Li, F., & Harmer, P. (1996). Confirmatory factor analysis of the group environment questionnaire with and intercollegiate sample. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 18(1), 49–63. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.18.1.49

- Lott, A. J., & Lott, B. E. (1965). Group cohesiveness as interpersonal attraction: A review of relationships with antecedent and consequent variables. Psychological Bulletin, 64(4), 259–309. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0022386

- Loughead, T. M., Fransen, K., Van Puyenbroeck, S., Hoffmann, M. D., De Cuyper, B., Vanbeselaere, N., & Boen, F. (2016). An examination of the relationship between athlete leadership and cohesion using social network analysis. Journal of Sports Sciences, 34(21), 2063–2073. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2016.1150601

- Manoli, A. E., Anagnostopoulos, C., Ahonen, A., Bolton, N., Bowes, A., Brown, C., Byers, T., Cockayne, D., Cooper, I., Du, J., Geurin, A., Hayday, E. J., Hayton, J. W., Jenkin, C., Kenyon, J. A., Kitching, N., Kirby, S., Kitchin, P., Kohe, G. Z., … Winand, M. (2022). Managing sport and leisure in the era of COVID-19. Managing Sport and Leisure, 27(1-2), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2022.2035963

- Marks, M. A., Mathieu, J. E., & Zaccaro, S. J. (2001). A temporally based framework and taxonomy of team processes. The Academy of Management Review, 26(3), 356. https://doi.org/10.2307/259182

- Mastromartino, B., Ross, W. J., Wear, H., & Naraine, M. L. (2020). Thinking outside the ‘box’: A discussion of sports fans, teams, and the environment in the context of COVID-19. Sport in Society, 23(11), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2020.1804108

- Mathieu, J. E., Kukenberger, M. R., D'innocenzo, L., & Reilly, G. (2015). Modeling reciprocal team cohesion–performance relationships, as impacted by shared leadership and members’ competence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(3), 713–743. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038898

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2020). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (4th ed.). SAGE.

- Morgan, D. L. (2007). Paradigms lost and pragmatism regained. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(1), 48–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/2345678906292462

- Morse, J. M. (1991). Approaches to qualitative-quantitative methodological triangulation. Nursing Research, 40(2), 120–123. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-199103000-00014

- Mudrack, P. E. (1989). Group cohesiveness and productivity: A closer look. Human Relations, 42(9), 771–785. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872678904200902

- Munroe, K., Estabrooks, P., Dennis, P., & Carron, A. (1999). A phenomenological analysis of group norms in sport teams. The Sport Psychologist, 13(2), 171–182. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.13.2.171

- Naraine, M. L., & Parent, M. M. (2016). Illuminating centralized users in the social media ego network of two national sport organizations. Journal of Sport Management, 30(6), 689–701. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2016-0067

- Naraine, M. L., Pegoraro, A., & Wear, H. (2020). #Wethenorth: Examining an online brand community through a professional sport organization’s hashtag marketing campaign. Communication & Sport, 9(4), 625–645. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167479519878676

- Naraine, M. L., & Wanless, L. (2020). Going all in on AI. Sports Innovation Journal, 1, 49–61. https://doi.org/10.18060/23898

- Patton, M. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (4th ed.). Sage.

- Prapavessis, H., & Carron, A. V. (1996). The effect of group cohesion on competitive state anxiety. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 18(1), 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.18.1.64

- Seidman, I. (2013). Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences. Teachers College Press.

- Senécal, J., Loughead, T. M., & Bloom, G. A. (2008). A season-long team-building intervention: Examining the effect of team goal setting on cohesion. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 30(2), 186–199. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.30.2.186

- Skinner, J., Edwards, A., & Corbett, B. (2014). Research methods for sport management. Routledge.

- Skinner, J., & Smith, A. C. T. (2021). Introduction: Sport and COVID-19: Impacts and challenges for the future (volume 1). European Sport Management Quarterly, 21(3), 323–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2021.1925725

- Smith, A. C. T., & Skinner, J. (2022). Sport management and COVID-19: Trends and legacies (volume 2). European Sport Management Quarterly, 22(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2021.1993952

- Smith, A. C. T., & Stewart, B. (2010). The special features of sport : A critical revisit. Sport Management Review, 13(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2009.07.002

- Sotiriadou, P., & De Bosscher, V. (2017). Management high-performance sport: Introduction to past, present and future considerations. European Sport Management Quarterly, 18(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2017.1400225

- Spink, K. S., Wilson, K. S., & Odnokon, P. (2010). Examining the relationship between cohesion and return to team in elite athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11(1), 6–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2009.06.002

- Wagstaff, C. R. D., Arthur, C. A., & Hardy, L. (2018). The development and initial validation of a measure of coaching behaviors in a sample of army recruits. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 30(3), 341–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2017.1384937

- Westre, K. R., & Weiss, M. R. (1991). The relationship between perceived coaching behaviors and group cohesion in high school football teams. The Sport Psychologist, 5(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.5.1.41

- Widmeyer, N. W., Brawley, L. R., & Carron, A. V. (1985). The measurement of cohesion in sport teams: The group environment questionnaire. Sports Dynamics.

- Widmeyer, N. W., & Ducharme, K. (1997). Team building through team goal setting. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 9(1), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413209708415386

- Wymer, S., Thompson, A.-J., & Martin, A. (2020). Diminishing the distance during social distancing: An exploration of Australian sport organisations’ usage of social live streaming services throughout COVID-19. In P. M. Pedersen, B. J. Ruihley, & B. Li (Eds.), Sport and the pandemic: Perspectives on COVID-19’s impact on the sport industry (pp. 61–69). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003105916

- Zander, A. (1971). Motives and goals in groups. Academic Press.