ABSTRACT

Research question

This paper explores the recollections of twelve women’s physical education experiences in England, and the impact of this on their future footballing opportunities; six of whom went on to become semi-professional footballers and six whom did not continue in football post school life.

Research methods

The age range of participants in the qualitative study was from 18 to 37 years. These themes were addressed using Bourdieu’s sensitising notions of symbolic violence and collective expectations. Furthermore, the study embeds itself within the broad critical feminist writings of Judith Butler and the theory of gender performativity.

Results and findings

Following the data collection, reflexive thematic analysis identified limiting narratives of success, sexism, and the significant role that gender played within footballing environments. The study identified key themes around gendered experiences of PE, school sport and community pathways in the context of girls’ and women’s football.

Implications

The recommendations suggest the promotion of a more inclusive landscape for women and girls’ participation in football, and physical education more broadly, is required if we wish to improve women and girls experiences within the sport.

Introduction

Engagement in physical activity (PA) and sport recreation during youth can be a considerable contributing factor to lifelong participation (Laakso et al., Citation2008; Lovell et al., Citation2019; Scheerder et al., Citation2006). More specifically it is well established that positive Physical Education (PE) experiences increase PA levels as an adult (Draper & Stratton, Citation2019; Flintoff et al., Citation2005; MacNamara et al., Citation2011). It is acknowledged that understanding the facilitators and barriers to sport can equip professionals with the correct strategies to promote lifelong sport and PA participation (Bade et al., Citation2019; Corbin et al., Citation2020). Although it is feasible to assume that PA as a whole and, more specifically, PE lessons increase PA levels as an adult, it can also have detrimental effects on those that have negative experiences in sport and PE (Bailey et al., Citation2015; Kirk et al., Citation2000). Current research often lacks specificity and holds bias towards binary notions of either a positive effect or negative effect that PA and PE can have on an individual. Despite sport policy and practice researchers exploring the significant relationship between PE lessons in schools and lifelong participation (Barney et al., Citation2015; Bocarro et al., Citation2008; Cardinal et al., Citation2013; Kulinna et al., Citation2018; Lahti et al., Citation2018) numerous authors highlight diverse issues around the experiences that women and girls face in football within sport and PE (Caudwell, Citation1999; Lewis et al., Citation2018; McSharry, Citation2017; Pope & Kirk, Citation2014; Wangari et al., Citation2017). The bigger issue remains why is such discrimination and overtly negative PE and community football experience such a core “stubborn policy issue” (Durden-Myers & Mackintosh, Citation2022).

This paper explores existing literature within sport, PE and football experiences of women and girls in England. The inaction, status quo and policy inaction is explored in this research endeavour using life history research methodology (Sparkes & Smith, Citation2014). Data was collected in the leeward shadow of the Women’s Euro 2022 Championships. Moreover, it will implement conceptual sensitising tools from Bourdieu’s theoretical framework throughout the research, which is underpinned by a critical feminist perspective, drawing upon key concepts including collective expectations, symbolic violence, and gender performativity (Bourdieu, Citation1989, Citation1990; Butler, Citation1988, Citation1990, Citation2011). The central research question is “what are the experiences of girls PE and football in secondary school (11–18 years old) and how do these experiences shape after school attitudes and behaviour around women and girls football participation?” More specifically the research aims to:

Explore the relationship between girls’ football in secondary school PE and the opportunities and experiences presented after school life in England;

Utilise Bourdieu and Butler’s theoretical insights to understand the experiences of women and girls within football, PE, and post-school participation exploring the role of gender in England;

Explain whether the delivery of girls’ football in PE lessons in England contributes to the social norms constructing and reconstructing gender and how this affects women as footballers their choices, attitudes and beliefs.

Literature review

PE and the contribution to lifelong participation

Whilst PE has been proven to play a key role in positively shaping young individuals living a healthy active lifestyle in adulthood (O’Donnell et al., Citation2020), we also acknowledge how there is a need to examine this research in a less binary manner, bringing to the fore the multiplicity of diverse pathways, processes, and experiences. An example of this polarisation in past research is present in the Lahti et al. (Citation2018) study, which focused on the positive effect that PE can have on an individual with the key finding suggesting daily PE throughout school encouraged participants to lead a more physically active lifestyle in adulthood. This research adds to existing research that embraces PE practices that promise idealised scenarios in terms of, for example, moral and aesthetic development, the building of national identity, or a healthy and fit population seeking to achieve national health objectives through exercise-oriented programmes (Quennerstedt et al., Citation2020). These practices are, in many respects, ideological in their representation.

Whilst it is widely acknowledged that, if experienced positively, PE can promote a healthy active lifestyle and inspire lifelong participation (Durden-Myers et al., Citation2018; Green, Citation2014; Martins et al., Citation2018; Scheerder et al., Citation2006; Trudeau & Shephard, Citation2008). Cardinal et al. (Citation2013) addressed the negative impact that PE lessons can have on an individual but not specifically around football. Women have also reported significantly lower PA levels compared to men, contributing to the evidence that women are less active than men (Active Lives Survey, Citation2019; Sport Wales, Citation2021).

Whilst there is seemingly more freedom of choice and opportunity for girl’s participation within a PE setting, the cultures and values of the curriculum exude male hegemony (Kastrup & Kleindienst-Cachay, Citation2014; Parratt, Citation2016; Stride et al., Citation2022). Flintoff and Scraton (Citation2001) have long argued that core PE lacks priority as many do not take the subject as a GCSE option, causing students to exert minimal effort in the lesson, contributing to PE’s lack of development as a curriculum subject in the twenty-first century. It was recently re-asserted how this status quo in gender hegemony around PE and football remains (Stride et al., Citation2022). Whilst in Europe, there is a movement towards, and acceptance of, a more gender-divergent PE culture that dismantles gender difference (Lundvall, Citation2016), the UK is far behind such a progressive model. With teacher preference of activities driving the PE curriculum, competitive team sports rule and provide a further barrier to gender inclusivity and continued PA outside of a school setting (Griggs & Ward, Citation2012). Coulter et al. (Citation2020) state that positive personal preferences of PE activities correlate to higher PA levels, and a movement away from a “mixed ability all-in” one-size-fits-all curriculum that reacts to both the learner’s interests and needs would create more meaningful PA agency for young people.

In the 2000s many school-aged girls identified that their opportunities to play football were very limited (Welford & Kay, Citation2007). In 2002, boy’s football comprised 32% of the PE curriculum, whereas for girls, this figure was only 13%, with the main driver of school-aged girls-football being out-of-school opportunities (18%) (Green et al., Citation2005). As a result, the vital, positive, entry route for girls into football is predominantly through male family members and peers. However, due to a lack of broader educational exposure, those that continued to engage in the sport as adults experienced negative stereotyping regarding gendered norms and sexuality (Grundlingh, Citation2010). Similarly, Pope and Kirk’s (Citation2014) study suggested women aged 28 + outlined the clear gender divide in their school PE lessons, prohibiting them from playing football as a result of the historic gendered notion of football being a “boy’s game”, framed as a masculine activity by older generations. Pielichaty (Citation2021) examined sibling relationship playing football in the school environment, whilst Everley (Citation2021) analysed the impact of the FA physical literacy programme for girls aged 5–12. In her study she established that this FA programme was a real success in developing leadership and physical literacy in young girls. Whilst interesting to see such studies, it did not look at the historical legacy of those not engaged and the long-term impact of PE as opposed to a “football programme”.

There are still issues in more recent access and provisions from women and girls. The Football Association (FA) reported that only 63% of schools currently offer girls’ football in PE lessons (FA, Citation2021). The FA have in response to this launched their “Let Girls Play” initiative that will aim to have 75% of schools providing equal access to football for girls in PE lessons by 2024. Even with initiatives such as this, access to opportunities in PE continues to ignore the changing societal and sporting landscape and risks isolating girls’ experiences to historic practices.

More recently, (Kostas, Citation2021, 63) has argued, “how ‘successful’ masculinity, girly femininity, sissies, and tomboys emerged through the material-discursive intra-actions of playgrounds, bodies, football, and heteronormative discourses”. This emergent new field of exploring multiple gendered fluid identities is an academic space we are aiming to locate our work alongside using a novel theoretical framework. Furthermore, a landmark empirical recent revisiting of this broad policy issue in English PE around gender by Stride et al. (Citation2022) suggested teachers’ explanations for teaching PE as single sex often still underpinned by a focus on boys’ physical superiority. One male teacher in this study argued “let’s just say it’s football, for example, and it just happens the four girls might be the worst … the boys might get angry with the girls” (Stride et al., Citation2022, p. 251). Whilst the National Curriculum for PE in England, FA (and school sport), policy and strategy have changed over the last decade, this sustained stubborn position of male views in particular remains an issue when viewed through a critical feminist lens.

Sexism in women’s football

It is widely acknowledged that women involved in football encounter various forms of sexism throughout their careers (Clarkson et al., Citation2022; Culvin, Citation2021; Goldman & Gervis, Citation2021; Lorenzini, Citation2020; Pfister & Pope, Citation2018), with much sexism occurring verbally via sexist, abusive, and derogatory language or expression. The expectation for change is put directly onto the player to solve, with women being told to change their outlook on football and having to exude a more feminine persona in order to cope (Caudwell, Citation1999; Caudwell, Citation2011; Lewis et al., Citation2018; McSharry, Citation2017). By overpowering, disempowering and silencing women and girls’ voices within all football settings, from community participation through to professional coaching pathways, systemic male hegemony typifies these historic views, contributing to an environment that young, impressionable, boys and girls have to accept and reproduce in order to survive (Sawiuk et al., Citation2021).

A seminal paper, often cited within the field of women’s footballing experience, is Caudwell’s (Citation1999) study exploring the relationship between gender, sexuality, and women and girls football experiences. Data-rich, with 437 questionnaires received from FA regional level teams, and a further 14 semi-structured interviews conducted, an overwhelming number of respondents (52.5%) claimed to have experienced difficulty in playing the “traditional male sport”. Twenty-two years later and the findings from this study still remain indicative of aspects of the women’s game discussed in this paper and others (Caudwell, 2010; Clarkson et al., Citation2022; Culvin, Citation2021; Lusted, Citation2011). Many believed they were branded as lesbians by male players because they played football, with players subjected to comments such as “Are you sure that she’s a woman? … Have you had a sex test? … Well, we don’t think number 9 on the other sides [sic] is a woman” (Woman footballer cited in Caudwell, Citation1999, p. 400). Not only highly discriminative and prejudiced, such remarks and attitudes are one of the major contributors to why women and girls drop-out within the sport, with women and girls, both consciously and unconsciously, yearning validation for their PA choices and are uncomfortable being subject to the undermining effects of constant, demeaning, sexist behaviour (Geissler, Citation2012). Further justified by McSharry (Citation2017), sexist behaviour forced some women and girls to feel they had to over-act their femininity (performative femininity) within their football team in order to feel accepted avoid the “butch lesbian” stereotype derived just because they play the sport. This qualitative study deserves acknowledgement as it challenges the stable notion of gender whereby women and femininity, like men and masculinity, are viewed as synonymous (Caudwell, Citation1999). There remains a significant presence of negative societal attitudes towards women and girl football players, and it is vital to acknowledge that the wider socio-cultural, environmental, political and policy factors that underpin PE, women’s and girl’s football have led to meta-narratives that seem to cut across many of the papers in this review.

Framing women and girls football experiences

It is vital to acknowledge the studies that draw upon theoretical insights into the work of gender and the unpicking sporting experiences for young women. McSharry (Citation2017) implemented aspects of Bourdieu’s theoretical framework, with masculine domination and collective expectations as two key concepts explored. Key findings reinforce that males owned and dominated football in PE lessons, and when girls did complete and were of a good ability, boys were left feeling “intimidated” and “emasculated” (collective expectations), with the threat to girls’ participation and effort being controlled by boys in a mixed environment (as supported by Flintoff & Scraton, Citation2001). Talent in football was charged with masculine implications; when a girl displayed skill in football they were frequently “regendered” via comments including “play like a boy”. There was an assumption that boys were more naturally skilled at football and that girls required help and encouragement. Similarly, Lewis et al. (Citation2018) found that FA educators were predominantly men, and existing women coaches were often viewed as inferior because of their gender. An assumption occurred that women lacked knowledge and ability to coach football because of their gender, leaving coaches in the study feeling unwelcomed and a lack of self-worth. Viewing gender through a Bordieuian lens of social acceptance and symbolic violence, this research also identified 9 out of 10 women coaches had experienced numerous accounts of abusive, derogatory, or sexist language, offering a highly uncomfortable, but exposing, insight to coach education and player participation in England.

In order to fully understand the experiences of women and girls within sport, feminist theory is widely utilised in gendered studies. Wangari et al. (Citation2017) implemented liberal feminist theory within their work, suggesting that inadequate funding is a vital limitation in women’s football, with media buy-in (traditional and social) required in order to enable effective change. More specifically, within PE, Roberts et al. (Citation2019) utilised post-structural feminist theory and found concepts of limiting narratives of success in sport, which can become a deterrent to achievement for many girls in PE; girls that achieve success in sport and PE were forced to be modest and not express their talent. At this specific school, the head of PE suggested that even though football became an emerging sport, there were no secondary school FA teams available to the girls. Despite many girls presenting an interest in playing football the limited volunteers and resources could only meet the demand of the boys’ league, presenting an unequal opportunity.

Stride et al. (Citation2019) implemented a middle-ground feminist lens, drawing upon the diverse range of feminist positions, to make sense of women’s experiences within football, finding that, albeit PE generally being positively received, there was a lack of football opportunities for girls in a school setting. Due to the male dominance and gender divide within classes, women and girls football opportunities were limited, and if they were available, it was due to the persistent demand for this delivery from the learners themselves. In addition, post-school dropout was often attributed to negative PE experiences, and the blatant, perpetuated, negative stereotyping that surrounds women and girls participation within the sport (see work by Constantinou et al., Citation2009; Preece & Bullingham, Citation2020 for further development of this discourse).

Caudwell (Citation1999) applied critical feminist politics, supported by Foucauldian interpretations of power, to route gender, and gendered issues within sport, deeply within the socio-cultural rather than the biological: gender as a culture of its own with its own inscription. By highlighting the normative beliefs and taken-for-granted assumptions prevalent within the sport, the barriers to women’s and girl’s participation in football are unmistakably presented. This hybrid model of theoretical framing creates a further dimension, enabling competing feminist theory to challenge societal constructs in a cohesive and powerful manner.

Theoretical framing

This paper actively adopts a feminist critique, with a critical feminist lens being applied that embraces the multi-faceted nature of feminist scholarship. Whilst critical feminist theory evokes multiple meanings, the overarching narrative is consistent: in society men are the “norm” and women are regarded as “irrelevant … or deficient – a ‘problem’” (Wigginton & Lafrance, Citation2019, p. 2). Understanding gender from a societal and cultural perspective, and its transfer into sport, is key to tackling the inequalities women face and challenging gender as a social construct. Caudwell’s (Citation1999) deconstruction of sex, gender, and masculinity/femininity, which incorporates Butler’s (Citation1990) view of sex as a social construct, provides critique of the visual representation of the “sexed body” being subject to gendered (masculine/feminine) socio-cultural norms and standards, contributing to the view of women/femininity and men/masculinity as synonymous (Butler, Citation1990, Citation1999; Caudwell, Citation1999; Scraton & Flintoff, Citation2013). Butler (Citation1990) believes that gender is an effect of the repetitive performance that a subject believes are the norm (gender performativity). Such norms of behaviour, for example, how a girl should walk or how they should wear a dress to appear an elegant “normal” woman, structures the fictive state of gender (Butler, Citation2011; Hey, Citation2006). Therefore, in a sporting context, there are distinct “heteronormative representations of gender” that are embedded into young women and girl athletes (Couture, Citation2016, p. 124; Tredway, Citation2014). With an affinity to Judith Butler’s feminist ideology; the term gender is used to signify biological sex, which in turn determines the accepted masculine and feminine behaviours that an individual is able to display, and thus the gendered experience is a learned performance – an act – imposed by society (Butler, Citation1988, Citation1990, Citation1999); which critiques the structural construction of gender, there is a tendency within this paper to draw more intimately upon post-structural/postmodern feminist positioning, which more closely analyses the historic-cultural landscape to showcase the reasons why society is inequal, helping to further understand and critically explore women and girls experiences and limiting narratives within PE and football.

Due to the complex, multi-faceted, nature of feminist research, in order to provide focused interrogation of the subject matter, conceptual tools from a Bourdieusian theoretical framework are applied to further support the feminist voice within this paper. With the examination of, and reflections on, societal structures at the heart of this study, Bourdieu and Passeron (Citation1977), Bourdieu (Citation1989, Citation1990) provides an insightful critical lens to “capture the reality of different groups, unequal interactions, and situations” (Cushion & Jones, Citation2006, p. 145), with the notion of symbolic violence and collective expectations considered in order to frame the women and girls experience and enable inequalities to best be explored. The application of this approach has been inspired by Lewis et al. (Citation2018) and their feminist critique of coach education.

With power dynamics, and the issues/struggles surrounding these, central to Bourdieusian critique, the connection to post-structural/postmodern feminist perspective is evident, and thus a natural development for the framing of the paper. The issues that surround power are entrenched in the socially constructed realities of society – norms, values and generational beliefs of the past which now inform the present – the origins and consequences of gender relations, and the gender ideology that this (re)produces and resists through the everyday male/female, are given further direct expression within this paper. An extension of McSharry’s (Citation2017) research, Bourdieu is utilised to address the “masculine domination” of sport, and how PE settings maintain the normalisation of gender binaries; “naturalisation, misrecognition and reproduction of masculine domination and subsequent gender inequalities” (p. 343). Essentially, this paper utilises a feminist lens with a collaborating structure underpinned by Bourdieu power theory. We draw upon the notion that, “poststructural theory moves the critical eye from structures to cultures revealing the underpinning discourses and networks of power responsible for maintaining inequity” (Aitchison, Citation2000, p. 181). The next section examines the policy and practice landscape of women and girls football in England.

Women and girls sporting participation context for football

shows the overall levels of physical activity in England. Data from 2019 to 2022 has been intentionally excluded due to the skew from the COVID-19 global pandemic, which has created considerable shifts in participation levels across all sport (Parnell et al., Citation2020; Mills and Mackintosh, Citation2022; Mackintosh, Citation2021).

Table 1. Data showing children and young people physical activity rates in England (Source: Sport England, Citation2019).

In secondary schools, the results suggest that all year groups became more active in comparison to the previous year. However, a gender gap exists from a young age, with boys (51%) being more likely to be active than girls (43%) ().

Table 2. Data showing adult physical activity levels 2019–2020 in England (Sport England, Citation2020).

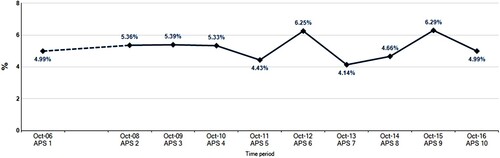

Men (65%) are more likely to live an active life than women (61%), and despite the gender gap existing it has reduced from 3.3% in 2019 to 1.3% in 2020. Moreover, results suggested PA levels decrease with age. Whilst the figures may not seem significantly disproportionate and paint a picture of PA uptake being far more balanced than suggested, the data does not take into account the struggles that women and girls have had to overcome in order to maintain an active lifestyle. The quantitative nature of the data inevitably means that the wider societal context and socio-cultural issues surrounding women and girls activity are hidden, therefore, de-sensitising the lived realities and shared experiences that qualitative data uncovers. Nonetheless, it does provide a starting point in which to be able to talk about difference, as clearly demonstrated within the historical analysis of the long-term football and sport participation patterns identified in the Active People Survey data from 2005–2016. illustrates an increase in over-16 women and girls football participation (at least once a week) within the region of the North-West of this study, a static level of adult women’s football participation for over 10 years. However, this is still disproportionately growing in comparison to the men’s game.

Figure 1. Data showing over-16 female participation rates 2006–2016 (Sport England, Citation2021).

English football policy and practice: a global position

In 2018, the FA (Citation2018) claimed approximately 2.5 million women and girls participated in football at least once in the year, however, the Active People Survey did not correspond to this level of participation (Bell, Citation2019). Most specific to the scope of this study, the single county that was the focus of this study in Cheshire (Citation2020) highlighted that in 2020 there were 3331 teams overall with 369 of the proportion being women’s and girl’s teams. With only 11% of formal teams being women and girls, this illustrates the skew in provision, opportunities and pathways for post-school women’s football. indicates that UEFA’s (Citation2019) Time for Action 2019–2024 has built confident plans for the expansion of the game across Europe. Of particular relevance to this study is the action to increase numbers but also change perceptions and tackle representation. Further to the FIFA (Citation2018) previously set out a strategy to raise participants to 60 million by 2026 in part through education, empowerment and positive impact on lives. As already shown in the previous studies post-1999 in England, there is a considerable challenge in meeting such visions. This is a core connection between the aims of the study and the theoretical approach and methodology employed to explore how despite much-lauded policy change we have seen an apparent status quo in practice and experiences and perceptions of women and girls.

Table 3. Background information on participants showing pseudonyms.

The UEFA (Citation2019) #TimeforAction plan established that by 2024 UEFA expects to double the number of women and girls playing football. The previous 15 years has seen in England around a 50% shortage in over-16 year old women taking part in once a week football (Sport England, Citation2021). Linked to these aspirations, there is also a plan to double the reach of the EURO 2022 championships and to have “changed perceptions of women’s football across Europe” (UEFA, Citation2019, p. 16). As UEFA stake its claim to women and girls football public policy agendas and development processes, so the global body, the Federation Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), have increased its political voice. Here FIFA (2018, p. 5) suggests a desire to grow participation, and double participation levels from 30 to 60 million alongside build foundations to then showcase the game globally. Across both FIFA and UEFA visibility, commercialisation and marketing potential is a constant thread to both organisation’s policy narratives. The micro aggressions, tensions of the women and girls football participant, coach and school child remain unacknowledged at best.

In England the FA are in parallel bold in their aspirations for the impact of policy and strategy change. Detailed analysis of this is beyond the scope of this paper. But it is a worth grounding the local participants in this critical feminist research endeavour. For example, the FA state their objective to create:

Equal football access for all girls at 90% of schools (primary/secondary), with delivery in PE lessons, lunchtimes and after school; 90% of schools (primary/secondary) in England to be part of The FA Girls’ Football School Partnerships network, supported by Barclays; outside schools every girl to have a Wildcats'1 session within easy traveling distance of their home; the majority of grassroots clubs nationally to have an offering for girls; ensure all under-7 to under-12 girls have easy access to an inclusive club with an appropriate competitive pathway within easy access from home. (FA, Citation2020, p. 14)

reimagining how PE is structured, for example, women teachers taking boys’ classes and teaching a range of activities, including those traditionally classed as activities solely for boys as well as those restricted to girls, would go some way to challenging assumptions, beliefs and stereotypes in the hegemonic domain. (Stride et al., Citation2022, p. 255)

Methodology

We view our methodology as determining how the researcher thinks and makes decisions about a study, and how they wish to engage with participants and generated data (Mills, Citation2014). We employ a social constructionist ontology and a critical feminist epistemology which will be the philosophy underpinning this methodology and the wider study. Social constructionism was established in the seminal work of Vygotsky (Citation1986) who advocated the notion that separating learning from social context was not possible. Whilst “ontology considers what types of things there are in the world and what parts the world can be divided into” (McQueen & McQueen, Citation2010, p. 151). Therefore, the ontological dimension of this aligns with the relativist ontology as it views reality as socially constructed and determined in a subjective manner relevant to the time, place, and context (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2003; Refai et al., Citation2015). Epistemology concerns itself with theories of knowledge and how we attain knowledge; feminists have held an interest in epistemology motivated by the idea that knowledge plays a vital part in sex inequality (Phelan, Citation2017) and the way in which gender influences what we take to be knowledge (Anderson, Citation1995).

Smith and Sparkes (Citation2016) suggest that the interview method is used mostly to collect qualitative data in a sport and exercise science setting; an interview offers flexibility in the direction in which the conversation takes, allowing researchers to ask unplanned questions if additional insight on a specific topic is required. Therefore, to capture participant’s experiences of football in PE and after school life, 12 life history interviews (Medcalf & Mackintosh, Citation2019; Smith and Sparkes, Citation2014; Tracy, Citation2020) were conducted that provided flexible development of content based upon responses and the ability for individual difference to be probed (Gale et al., Citation2019; Guest et al., Citation2013; McGrath et al., Citation2018). Whilst the reasoning of this study was abductive, which according to Sparkes and Smith (Citation2014, p. 36) is a combination of inductive and deductive reasoning that:

involves a dialectical movement between everyday meaning and theoretical explanations, acknowledging the creative process of interpretation when applying a theoretical framework to participants’ experiences.

Participants

Purposive and snowballing sampling, which allows the researcher to choose participants based on the individual’s specific characteristics (Sparkes & Smith, Citation2014) and for further participants to be recommended through participant networks (Saks & Allsop, Citation2019), was utilized within this study, allowing for a richer detail of content and context to be collected from each individual and an organic building of data. Whilst there is critique regarding this process, specifically in relation to the (lack of) diversity of the samples generated through such methods (Kirchherr & Charles, Citation2018), the criteria for inclusion in the study was transparent; women aged 18+, with some experience of playing football at school; and open, encouraging a wide range of invested participants to be recruited over a short period of time, and for the voices of a marginalised community (women’s footballers) to be championed (Sharma, Citation2017). We do acknowledge the limitations of such a process of regional sampling and across the clubs and contexts chosen for the study. Larger studies in different FA regions, football clubs and possibly even national contexts could, however, be opened up in future larger scale or longitudinal qualitative studies.

Via purposive sampling six elite women’s players from a North-West England football club were recruited, and a further six women who had participated in football through PE and school were recommended via snowballing. For ethics purposes, all participants have been provided with a pseudonym and any defining characteristics and information, for example, team names and geographic locations, have been redacted (Rubin & Rubin, Citation2005).

To critically analyse the data, a reflexive thematic analysis was employed. Braun and Clarke (Citation2012, Citation2020) imply that at its simplest thematic analysis offers a method to identify themes within a dataset and for describing and interpreting the meaning and importance of such themes. Braun and Clarke (Citation2006, Citation2012, Citation2020) advocate the use of coding frames and implementing multiple coders to identify key themes. This analysis predominantly involves coding, which identifies and labels something of relevance to the research question, whether at a semantic or latent level, building foundations for developing themes. Braun and Clarke (Citation2006, Citation2012, Citation2020) justify the use of thematic analysis as it provides a flexible approach, allowing modification whilst providing rich detailed yet complex accounts of data.

Findings and discussion

Five key themes emerged from the thematic analysis coding, with each theme providing further sub-topics where both competing and collective responses have been highlighted for discussion.

Limiting narratives of success

All participants of the study made it clear that PE in school had a positive or negative effect on whether they participated today. Despite some displaying positive experiences of football in PE due to the relieving pressure and fun nature, many expressed the negative experience PE provided for them describing the lack of opportunity to develop in school, the boy-orientated environment, and teachers dismissing the basics of football. The majority of participants highlighted the male gender being prioritised. Many suggested more attention being placed on boys football creating much more opportunities for them to play football via PE, afterschool clubs, and competitions. In addition, football at lunch time was very much boy-orientated, with teachers often reinforcing this norm. Roberts et al. (Citation2019) found similar in their study as they suggested some teachers had an old-fashioned attitude towards football and due to the limited resources and volunteers, they could only meet demands for the boys to play, creating gender discrimination.

Some participants felt that the boys were praised a lot more for their achievements (e.g. one participant explained they held a sponsor with Nike for their kit whilst girls had to buy their own). Furthermore, all participants held the belief that there is a major requirement to imbed football into the PE curriculum from an early age and those that did experience PE in primary school were more open to playing the sport.

Many participants implied their primary school football team were boys only; therefore, they were not allowed to play and those “lucky” enough to represent the boys team tended to be the only girl. This provided boys with more opportunity to play and develop from a young age, isolating girls, with their only developmental opportunity being to play outside of school at a club level. When participants were able to play in secondary school, they were often irregular, one-time only, sessions that had very little structure. In addition, those that portrayed skill in football could not develop due to the limited teams and competitions, and the lack of girls that put effort into football in PE because it was never delivered regularly as part of the curriculum. Similarly, Flintoff and Scraton (Citation2001) and Stride et al. (Citation2022) 20 or so years later (including Flintoff and Scraton to this field of research practice) noted that because PE was not embedded into the primary curriculum from a young age, when they did play football, many would refuse to exert themselves, leaving those keen footballers with no developmental opportunity in school. Non-footballers highlighted the lack of teams and expressed their opinion on the sport:

The stereotypical football and rugby are boys games and girls never really get that experience from a young age unless for example like my primary school they had a football club. (Sarah)

This key theme of limiting narratives of success heavily aligns with studied papers within the literature review supporting the evidence that PE and sport present women and girls with limiting narratives of success, and male superiority and lack of opportunity being two key contributing factors (Pope & Kirk, Citation2014; Roberts et al., Citation2019; Welford & Kay, Citation2007).

Sexism

The participants identified as the inferior gender was a common overarching theme that emerged from the data analysis. Many of the participants encountered sexism starting as early as primary school, Claire described she was the only girl in the primary school football team receiving comments like,

“Why is there a girl playing” and “why is a girl the captain?” (Claire)

Furthermore, the transition to secondary school facilitated sexism where boys often belittled women and girls achievements for example, Claire received the highest grade in GCSE PE and the boys argued:

… well I would have got that grade if I was being graded as a girl. (Claire)

The boys took pity on me because I was a girl who was playing football. (Julie)

Such comments can leave a young girl confused as to her place in PE and football participation as Julie later described multiple sexist situations:

feeling undermined I think almost like you didn’t belong there, like I remember saying to my mum, mum I don’t know if I should be playing this, there are no other girls.

Progressing into adulthood, the sexism became more evident to the footballers, whether it was subtly through officials questioning whether the rules are the same as the men’s game. These reasserted comments received earlier in PE, community football and opened doubt for these women. Or, as directly stated about football and the link to PE as one person received:

“Well, it’s not like the men’s game, the play is completely different” (Gemma)

Whilst others suggest they are often sexualised with behaviours such as:

Wolf whistled when you are pulling your socks up, or you bend over, or pull your shorts up. (Julie)

It was evident that some footballers experienced overtly sexualised comments whilst the male gender often domineered the sport, leaving participants feeling belittled. An ability to sustain participation in PE and football, or community clubs matches stretching into the elite game became a feature of such life histories. All sexist comments and behaviour addressed in this theme align with Bourdieu’s (Citation2007) concept of symbolic violence, which is discussed in the following theme and will be analysed in greater depth.

Symbolic violence as mainstream in women’s football

Symbolic violence can function through various components working simultaneously, ignoring the arbitrariness of domination, recognising the domination as legitimate, and the victim internalising the domination (Sapiro, Citation2015). Bourdieu (Citation2007) advocates that symbolic violence allows individuals considered symbolically dispossessed to accept the domination, whereby acceptance becomes a fundamental factor of violent relations. Such metaphorical violence can often be revealed in abusive, derogatory, or sexist language or behaviour that can indirectly form social positioning (Bourdieu, Citation2007; Ganuza et al., Citation2019; Lewis et al., Citation2018).

Bourdieu (Citation2001) found that men encouraged women’s oppression and obedience via positive or negative collective expectation, to which is formed through social norms. For example, the McSharry (Citation2017) study found the collective expectation of intimidation and emasculation when girls expressed talent in football as the social norm was that the sport is male-dominated, therefore, only males can portray such talent.

It is widely acknowledged that sexualisation of women and girl generally and as athletes athlete exists (Daniels & Wartena, Citation2011; Nezlek et al., Citation2015; Petty & Pope, Citation2018), as per this study revealed many comments that were highly sexualised similar to:

Can they pull their shorts higher and have tighter tops? (Julie)

Julie, like others above, is indicative of women experiencing has become a form of normalised sexism (Stride et al., Citation2022). The study does not aim to build a neat causality. It does, however, generate insights into how such experiences and their interpretations by the women from their life histories could shape later life patterns and behaviours. Such symbolically violent statements offered evidence of clear misogynistic and opened narrative doors into what may or could have been for women.

This shows symbolic violence, as Bourdieu (Citation2007) outlines the key characteristics involving sexist, abusive, or derogatory language or expression to which this comment portrays. Many participating footballers received reoccurring belittling comments such as:

“You are a girl you don’t know what you’re talking about in football, you are a woman” … “do you know the offside rule?” (Julie)

Such violence evidently existed and whilst some experienced it directly, many were aware of sexism occurring in day-to-day life around the fringes of women’s football spaces. For example, the majority of participants outlined social media and TV media as being key platforms for sexism to occur as numerous participants made comments such as:

It’s like loud noise at a kids party” and “why is this woman commentating a men’s game, its dire”. (Claire)

Such comments were often made solely because someone might be a woman commentator interested in the men’s game. Several participants in the research highlighted such media-led aspects as almost being “accepted” components of the wider woman’s game. Describing this incident as “accepted” and that this was a part of women’s football to which Bourdieu and Wacquant (Citation1992) support as those experiencing symbolic violence accept the domination in their field as they are often misrecognised or unrecognisable (Kim, Citation2004). Similarly, one participant described a clip showing women’s goalkeeper letting a goal in containing comments including:

“You should make the goal smaller” … “why do they play 90 minutes?” and “how long do they play?” (Julie)

Despite the indirect nature, the abusive, sexist, and derogative language inevitably affected the footballers, making them feel “angry” and question whether it was worth playing the sport. This is one of our core theoretical vehicles for helping to explain the potential loss of participants from PE and community sport through to the elite spheres of some of our respondents. Bourdieu (Citation2002) suggests that symbolic violence can lead victims to blame themselves for their suffering, which could perhaps offer an explanation as to why many participants that experienced such violence often blamed themselves and accepted that it was a part of their society.

Collective gendered expectations around football

According to Bourdieu (Citation2001) both masculine domination and compulsory heterosexuality have revealed clear negative collective expectations of women in football as men and bous oppressed women and girls through the enforcement of social norms and stereotypes. McSharry (Citation2017) applied Bourdieu’s perspective of masculine domination to PE to which results shared similarity with this paper. Participants highlighted that boys regularly dismissed girls sporting achievements/grades:

“If I was in your race I would have won by 5 seconds” (Gemma) and “why do they automatically get a 10, we are better than them?” (Amber)

Researchers suggest that boys utilise belittling devices to increase their self-esteem (Clark & Paechter, Citation2007; Larneby, Citation2016; McSharry, Citation2017) and each time they disregard and critique girls, they reaffirm their self-competence and masculinity (Bourdieu, Citation1990). Several footballers that displayed talent experienced being regendered via direct comments such as:

She plays like a boy. (Mary)

you are good for a girl. (Julie)

you are strong like a boy, you don’t get pushed off the ball. (Fatima)

From a male perspective, performing in football portrays effective masculinity, increasing physical capital and ultimately being seen as a valued body (Bourdieu, Citation1984; Hill, Citation2009; Sparkes et al., Citation2007). Therefore, for women and girls to display talent in a male-dominated sport, they must be regendered due to the threat of male privilege. We build suggested future research links with other research with 30 women’s professional players in the professional game women expressed gratefulness for access to a professional game (Clarkson et al., Citation2022). Using Bourdieu, these researchers argue power dynamics here are clearly at play, with evidence suggesting most players felt under-valued and not treated as legitimate professionals. Here parallels seem present with the younger player experiences as people move through talent systems or school PE (Culvin, Citation2021). The critical feminist lens we use offers a powerful counterbalance to other research that has argued FA school-based PE projects offer a largely positive experience for girls. Yet only 63% of girls have access to PE-based football in England post-Women’s World Cup (Youth Sport Trust, Citation2022; online).

Compulsory heterosexuality was also an assumed feature of such practices and policy areas. Bourdieu (Citation2001) suggested that in order to be feminine one must avoid all characteristics and practices that can be associated with manliness, therefore, a collective expectation of society is heteronormative behaviour. This belief could provide an explanation behind the following comments regarding the sexuality of the women and girls who play football. Some footballers in the study expressed their opinion that:

Men assume that every female player is butch or gay. (Claire)

Whilst Gemma argued:

“Lads always ask, ‘oh how many girls in your team are gay?’ and ‘what goes on in the changing rooms?” (Gemma)

Similar to participants of Caudwell’s (Citation1999) study Gemma argues that this is the predominant stereotype of women and girls who play football, however, the inclusive nature assuming all players sexualities is indiscriminative. The stereotype for women and girls who play football to be identified as “gay” and “butch” was a site that Caudwell (Citation1999) found to consist of anxieties regarding gender and sexuality. A point further cemented by Caudwell’s (2010) polemic on this issue. Despite Caudwell (Citation1999) suggesting sexuality was a concern for all participants regardless of sexual identity, some participants of this study disagreed, raised no concern and accepted that:

Every female footballer has been through that “oh you lezza” stage .([Amanda)

Consistent with this, non-footballers suggest that women and girls who play football are perceived as butch because:

If as a woman you play football you aren’t feminine and are immediately assumed to be gay because you are portraying more masculine qualities. (Christina)

Such findings align with Butler’s (Citation1999) beliefs that gender and sex are socially constructed to which women and girls display feminine traits and are heterosexuals, whilst men display masculine traits and direct their desire towards women. Apparent in the Caudwell (Citation1999) findings was the idea that women accepted that individuals assuming players sexuality were inclusive of playing football, and former footballer Kiera who played throughout school, however, stopped when she reached college made a very clear statement supporting this:

I just got used to the fact that boys would call me a butch lesbian or a “rug muncher”. (Kiera)

Gender performativity

There is a well-documented critical feminist approach and research agenda to examine gender equality in sport (Burke, Citation2010; Fielding-Lloyd & Mean, Citation2016; Everley et al., Citation2022). Extending this study in the context of girls PE experiences and later life football participation, the majority of participants spoke to aspects of Judith Butler’s concept of gender performativity. Participants suggested that girls were expected to perform social norms such as “wear a dress”, “be feminine”, “like pink”, and “just look pretty”. Butler (1993) refers to this as “girling” which is the formation of enacted femininity, suggesting that a girl is produced with the expectation of employing ideals of femininity and citing the norm to remain viable (Caudwell, Citation1999). Football as a sport tends to dismiss these factors as:

You get muddy and it isn’t really what girls like or it’s not seen as a girly sport. (Mary)

Consistent to Butler’s (Citation1990, Citation1999, Citation2011) gender performativity theory, Mary suggests that football is a gendered sport due to the rough-natured attributes required to play that only males should display in an attempt to enhance masculinity. Despite the passion footballing participants held for their sport, stereotypes and social norms made them question whether they should be playing a sport considered “a boy’s game”:

Should I be playing netball, should I be living up to this stereotype, should I not be playing football at lunch with the boys it makes you question the things that make you happy just because of someone else’s comments. (Claire)

Questioning the PE and football experience of participation is a potentially subtle third space between playing and not playing. It is a similar “silence” in accommodating the stereotypes and calling into question PE enjoyment that a young woman may have. The subtle nature of this was further expanded by Claire in how she developed her argument later stating that:

Girls play netball and boys play football. Erm and it links into the whole well what a female should, should act like whether that’s right or how a male should display masculinity … the whole femininity and masculine traits some people might not want to be associated with that. (Claire)

Claire suggested some women and girls may not want to be associated with displaying “masculine traits” which was evident in the following comments, offering insight that some non-footballers had Butler’s (Citation1990, Citation1999, Citation2007) idea of gender performativity imbedded into them from a young age as one argued that football is:

Masculine and rough, I think maybe girls aren’t supposed to play it because they are stereotyped to be feminine girls who should play non-contact sport. (Amber)

Similarly, another argued that:

It can be quite rough, and women are not supposed to be viewed in this way, they are supposed to play girly sports such as dance or netball that are maybe quite aesthetically pleasing. (Christina)

Butler (Citation1990) argues that “body practices” required in a sport such as football can present masculine traits that may not be associated with traditional views on women and girls displaying feminine traits, that non-footballers such as Amber and Christina were raised to perform. Choice and trends in delivery and school PE curriculum design are also implicated here as is paralleled by other more recent research (Kostas, Citation2021; Stride et al., Citation2022).

Conclusion

The application of a novel critical feminist lens with conceptual tools accredited to Bourdieu (Citation1989, Citation1990, Citation2001, Citation2007) and Butler (Citation1988, Citation1990, Citation1999, Citation2007, Citation2011) has made it more feasible to demonstrate the complexities of the experiences women and girls as a whole, but, in particular as footballers. We add to existing knowledge by exploring the link between childhood PE experience and longevity in adult football participation by women and girls. We do so by using life history methodologies. Employing a theoretically rich framework has better allowed us to explore the relationship between the delivery of girls football in secondary school PE and its prolonged sustainment after school life, however, it revealed a highly gender-performed society; the sexist and male-domineering nature of male peers, spectators, and “friends”, whilst PE lessons and social media were the key sites for such behaviour to take place. We underpin our research endeavour by developing four core recommendations to challenge the hegemonic status quo. The study excluded male participants, which could have provided an interesting juxtaposition to the data to further understand gendered experiences of football and PE. Likewise, male and female PE teachers, club coaches might also offer a wider picture around the silences, symbolic violence and performativity that are present.

A concept participants regularly referred to through their experiences was gender performativity (Butler, Citation1990): the idea that girls were raised to perform acts that make them a girl, such as “wear a dress”, “be feminine”, “like pink”, and “just look pretty”. Such social norms often led participants to question whether they should be playing this male-dominated sport that only boy’s should play because of the “masculine” traits required to perform (Butler, Citation1990, 1993, Citation2007). A potential opportunity here is to link such gender theory-related research with that of evaluation work in FA programmes (Everley, Citation2021) and new initiatives such as using gender equity training within FA level 1 coaching awards.

Participants raised their opinion that males were often presented with far more opportunities in football at school which was also apparent leading into adulthood, leaving women with limiting narratives of success in sport (Clarkson et al., Citation2022; Pope & Kirk, Citation2014; Roberts et al., Citation2019; Welford & Kay, Citation2007). In addition, a considerable amount of overtly sexist comments and behaviours were directed at participants of the study consisting of males belittling female achievements as they believed they were the superior gender (Cushion & Jones, Citation2006; Lewis et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, participants experienced being regendered and told they “play like a boy” when displaying talent within football with many addressing their sexuality was often indiscriminately assumed by men solely because they play football. The men and boys domination and compulsory heterosexuality that still exists in a sport that has gained such rapid women and girls provision is highly disappointing.

All current women’s football strategies (FA, Citation2020; FIFA, 2018; UEFA, Citation2019) advocate their stance against gender discrimination and believe football can tackle this however; this project has presented contradicting evidence. This supports other evidence that the FA’s governance structures are still overwhelmingly dominated by men (Griggs & Biscomb, Citation2010) with a generally conservative approach to gender equality and promotion of the women’s game (Sequerra, Citation2014). There is also evidence of some resistance to the implementation of equality initiatives in regional governing bodies such as County Football Associations (Lusted, Citation2009, Citation2011). It is concluded that to ensure equality for all genders and to tackle the existing role of gender norms, the following should be considered for future practice: (1) All secondary schools should focus on school sport with football gaining more priority on the curriculum, this should enhance the provision of extracurricular football and school competitions. (2) Schools struggling to form teams should create a team with a local school to compete, however, to avoid this requirements boy’s and girl’s football should receive equal facility times for extracurricular activities and competitions. (3) Teacher training and coach education programmes should provide essential training on gender equality to ensure that equal opportunities are provided to play each sport and social norms, such as girls not playing football are confronted. This is as suggested by principles defined by Stride et al. (Citation2022). (4) Further exploration of the wider landscape of women and girls’ access, opportunity and experience across the sporting landscape is required to ensure that there are multiple sporting pathways through which women and girls can flourish, be it through school, community or elite sport. For example, the FA level 1 award has gender equity training within it, the effectiveness and implications and efficacy of this remain an area for future research.

The paper extends the use, application and insights gained from the theoretical framework employed using Bourdieu and Butler. We encourage others to use these ideas to helper-imagine the dismantling, reformation and rearranging of the curriculum, provide equal opportunity, and educate professionals may allow more girls to play football in PE, presenting long-term impacts in increasing PA and the provision of women’s football for a prolonged period of time, far beyond their school life. Again, we return to the work of (Caudwell, Citation2011, 330) who argues that the view that women not being welcome in the game of football – “ … epitomizes some men’s response to the presence of women on the football pitch”. Ten years on the research agenda in this policy space is starting to genuinely challenge this view. However, sufficient progress is yet to be made in pioneering new safe spaces for women and girls football that are truly empowering and emancipatory, not discriminatory and reliant on constructs of heteronormative norms of behaviour (Stride et al., Citation2022). This most recent theoretical call to arms is a powerful agenda we, as researchers, align with and embrace.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aitchison, C. (2000). Women in leisure services: Managing the social-cultural nexus of gender equity. Managing Leisure, 5(4), 181–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/13606710010001789

- Anderson, E. (1995). Feminist epistemology: An interpretation and a defense. Hypatia, 10(3), 50–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.1995.tb00737.x

- Bade, D., Camilleri, L., Bradford, K., & Carty, C. (2019). Exploring the barriers and facilitators to school and club sport participation for adolescent girls in greater western Sydney. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 22(2), 75–115.

- Bailey, R., Cope, E., & Parnell, D. (2015). Realising the benefits of sports and physical activity: The Human Capital Model. Retos, 28, July, pp. 147–154.

- Barney, D., Pleban, F. T., Wilkinson, C., & Prusak, K. A. (2015). Identifying high school physical education physical activity patterns after high school. The Physical Educator, 7(2), 278–293.

- Bell, B. (2019). ‘Women’s euro 2005 a ‘watershed’ for women’s football in England and a new era for the game?’. Sport in History, 39(4), 445–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/17460263.2019.1684985

- Bocarro, J., Kanters, M. A., Casper, J., & Forrester, S. (2008). School physical education, extracurricular sports, and lifelong active living. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 27(2), 155–166. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.27.2.155

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction a social critique of the judgement of taste. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1989). Social space and symbolic power. Sociological Theory, 7(1), 14–25. https://doi.org/10.2307/202060

- Bourdieu, P. (1990). In other words: Essays towards a reflexive sociology. Stanford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (2001). Masculine domination. Stanford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (2002). The weight of the world: Social suffering in contemporary society. Stanford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (2007). Sketch for a self-analysis. University Of Chicago Press.

- Bourdieu, P, & J-C, Passeron. (1977). Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. London: Sage.

- Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. J. D. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. Polity Press.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper (Ed.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology (3rd ed., pp. 57–71). APA books.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2020). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis?’ Qualitative Research in Psychology. [Online] ‘First online’ published online 12th August 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Burke, M. (2010). A feminist reconstruction of liberal rights and sport. Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 37(1), 11–28.

- Butler, J. (1988). Performative acts and gender constitution: An essay in phenomenology and feminist theory. Theatre Journal, 40(4), 519–531. https://doi.org/10.2307/3207893

- Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. Routledge.

- Butler, J. (1999). Gender trouble. Routledge.

- Butler, J. (2007). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. Routledge.

- Butler, J. (2011). Bodies that matter: On the discursive limits of “sex”. Routledge.

- Cardinal, B. J., Yan, Z., & Cardinal, M. K. (2013). Negative experiences in physical education and sport: How much do they affect physical activity participation later in life? Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 84(3), 49–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2013.767736

- Caudwell, J. (1999). Women’s football in the United Kingdom: Theorizing gender and unpacking the Butch lesbian image. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 23(4), 390–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723599234003

- Caudwell, J. (2011). Reviewing UK football cultures: continuing with gender analyses (Vol. 5, pp. 323–329). Soccer and Society.

- Cheshire, F. A. (2020). Cheshire FA handbook 2019/20. Football Association. [Online] Retrieved January 8, 2021, from cheshire-fa.pdf.

- Clark, S., & Paechter, C. (2007). ‘Why can’t girls play football?’ Gender dynamics and the playground. Sport, Education and Society, 12(3), 261–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573320701464085

- Clarkson, B. G., Culvin, A., Pope, S., & Parry, K. D. (2022). Covid-19: Reflections on threat and uncertainty for the future of elite women’s football in England. Managing Sport and Leisure, 27(1–2), 44–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1766377

- Constantinou, P., Manson, M., & Silverman, S. (2009). Female students’ perceptions about gender-role stereotypes and their influence on attitude toward physical education. Physical Educator, 66(2), 85–96.

- Corbin, C. B., Kulinna, P. H., & Sibley, B. A. (2020). A dozen reasons for including conceptual physical education in quality secondary school programs. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 91(3), 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2019.1705211

- Coulter, M., Scanlon, D., MacPhail, A., O’Brien, W., Belton, S., & Woods, C. (2020). The (mis)alignment between young people’s collective physical activity experience and physical education curriculum development in Ireland. Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education, 11(3), 204–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/25742981.2020.1808493

- Couture, J. (2016). ‘Triathlon magazine Canada and the re-construction of female sporting bodies. Sociology of Sport Journal, 33(2), 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2015-0010

- Culvin, A. (2021). Football as work: The lived realities of professional women footballers in England. Managing Sport and Leisure, 1–14.

- Cushion, C., & Jones, R. L. (2006). Power, discourse, and SV in professional youth soccer: The case of Albion Football Club. Sociology of Sport Journal, 23(2), 142–161. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.23.2.142

- Daniels, E. A., & Wartena, H. (2011). Athlete or sex symbol: What boys think of media representations of female athletes. Sex Roles, 65(7), 566–579. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-9959-7

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2003). Introduction The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The landscape of qualitative research theories and issues (2nd edition). Sage.

- Draper, N., & Stratton, G. (2019). Physical activity: A multi-disciplinary introduction. Routledge.

- Durden-Myers, E. J., Green, N. R., & Whitehead, M. E. (2018). Implications for promoting physical literacy. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 37(3), 262–271. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2018-0131

- Durden-Myers, E. J., & Mackintosh, C. (2022). The structural and micropolitical realities of physical literacy professional development in the United Kingdom: Navigating professional vulnerability. Sport, Education and Society, iFirst 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2022.2137792

- Everley, S. (2021). Physical literacy and the development of girls' leadership: An evaluation of the English Football Association's Active Literacy through storytelling programme, 50, 668–683.

- Everley, S. (2022). Physical literacy and the development of girls’ leadership: An evaluation of the English football association’s active literacy through storytelling programme. Education 3-13, 50(5), 668–683. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2021.1898433

- FIFA. (2018). Womens' Football Strategy. Zurich: FIFA.

- Fielding-Lloyd, B., & Mean, L. (2016). Women training to coach a men’s sport: Managing gendered identities and masculinist discourses. Communication and Sport, 4(4), 401–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167479515588720

- Flintoff, A., Long, J., & Hylton, K. (2005). Youth, sport and active leisure: Theory, policy and participation. Leisure Studies Association.

- Flintoff, A., & Scraton, S. (2001). Stepping into active leisure? Young women’s perceptions of active lifestyles and their experiences of school physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 6(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/713696043

- Football Association. (2021). Let Girls Play aims to give all girls equal access to football by 2024. Available at: www.thefa.com/news/2021/oct/11/letgirlsplay-20211011

- Football Association. (2018). Women’s and Girls’ Football in Numbers. [Online] Retrieved January 21, 2021, from https://www.thefa.com/-/media/thefacom-new/files/womens/fa_womens_girls_in_numbers_infographic_2017-18.ashx?la=en

- Football Association. (2020). Inspiring positive change- The FA strategy for women’s and girl’s football: 2020–2024. Football Association. [Online] Retrieved January 8, 2021, from inspiring-positive-change-womens-football-strategy-202024.pdf.

- Gale, L. A., Ives, B., Potrac, P., & Nelson, L. (2019). Trust and distrust in community sports work: Tales and the “shop floor”. Sociology of Sport Journal, 36(3), 244–253. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2018-0156

- Ganuza, N., Karlander, D., & Salo, L. (2019). A weave of SV: Dominance and complicity in sociolinguistic research on multilingualism. Multilingua, 39(4), 451–473. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2019-0033

- Geissler, D. A. (2012). From Masculine Myths to Girl Power Realities: The Athletic Female Body and The Legend of Title IX. Ph.D. University of Illinois.

- Goldman, A., & Gervis, M. (2021). “Women are cancer, you shouldn’t Be working in sport”: Sport psychologists’ lived experiences of sexism in sport. The Sport Psychologist. [Online]. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2020-0029

- Green, K. (2014). Mission impossible? Reflecting upon the relationship between physical education, youth sport and lifelong participation. Sport, Education and Society, 19(4), 357–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2012.683781

- Green, K., Smith, A., & Roberts, K. (2005). Young people and lifelong participation in sport and physical activity: A sociological perspective on contemporary physical education programmes in England and Wales. Leisure Studies, 24(1), 27–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/0261436042000231637

- Griggs, G., & Biscomb, K. (2010). Theresa Bennett is 42 … but what’s new? Soccer and Society, 11(5), 668–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2010.497370

- Griggs, G., & Ward, G. (2012). Physical education in the UK: Disconnections and reconnections. The Curriculum Journal, 23(2), 207–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2012.678500

- Grundlingh, M. (2010). Boobs and balls: Exploring issues of gender and identity among women soccer players at Stellenbosch university. Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender, 24(85), 45–53.

- Guest, G., Namey, E. E., & Mitchell, M. L. (2013). Collecting qualitative data: A field manual for applied research. SAGE Publications.

- Harris, J. (2005). The image problem in women’s football. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 29(2), 184–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723504273120

- Hey, V. (2006). The politics of performative resignification: Translating Judith Butler’s theoretical discourse and its potential for a sociology of education. Taylor & Francis, 27(4), 439–457.

- Hill, J. L. (2009). Challenging “a man’s game”: women’s interruption of the habitus in football. Paper presented at: The British Education Research Association Annual Meeting. University of Manchester, Manchester, 2-5th September.

- Kastrup, V., & Kleindienst-Cachay, C. (2014). “Reflective co-education” or male-oriented physical education? Teachers’ views about activities in co-educational PE classes at German secondary schools. Sport, Education and Society, 21(7), 963–984. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2014.984673

- Kim, K. M. (2004). Can Bourdieu’s critical theory liberate us from the SV? Cultural Studies-Critical Methodologies, 4(3), 362–376. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708603254896

- Kirchherr, J., & Charles, K. (2018). Enhancing the sample diversity of snowball samples: Recommendations from a research project on anti-dam movements in Southeast Asia. PLoS One, 13(8). [Online] Published 22nd August 2018. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201710

- Kirk, D., Fitzgerald, H., Wang, J. C. K., & Biddle, S. J. H. (2000). Towards girl-friendly physical education The Nike/ YST girls in sport partnership project final report. Institute of Youth Sport.

- Kostas, M. (2021). Real’ boys, sissies and tomboys: Exploring the materialdiscursive intra-actions of football, bodies, and heteronormative discourses. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 43(1), 63–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2021.1999790

- Kostas, M. (2021). Real boys', sissies and tomboys exploring the material discursive intra-actions of football, bodies and heteronormative discourses. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 1–23.

- Kulinna, P. H., Corbin, C. B., & Yu, H. (2018). Effectiveness of secondary school conceptual physical education: A 20-year longitudinal study. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 15(12), 927–932. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2018-0091

- Laakso, L., Telama, R., Nupponen, H., Rimpela, A., & Pere, L. (2008). Trends in leisure time physical activity among young people in Finland, 1997-2007. European Physical Education Review, 14(2), 139–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X08090703

- Lahti, A., Rosengren, B. E., Nilsson, J.-A., Karlsson, C., & Karlsson, M. K. (2018). Long-term effects of daily physical education throughout compulsory school on duration of physical activity in young adulthood: An 11-year prospective controlled study. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 4(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2018-000360

- Larneby, M. (2016). Transcending gender hierarches? Young people and football in Swedish school sport. Sport in Society, 19(8–9), 1202–1213. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2016.1159194

- Lewis, C., Roberts, S. J., & Andrews, H. (2018). Why am I putting myself through this? Women football coaches’ experiences of the Football association’s coach education process. Sport Education and Society, 23(1), 28–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2015.1118030

- Lorenzini, S. (2020). Between racism and sexism, the case of female soccer players. An intercultural and gender based pedagogical reflection. Intercultural Education- Theories, Practice, Research, 18(1), 122–137.

- Lovell, T. W. J., Fransen, J., Bocking, C. J., & Coutts, A. J. (2019). Factors affecting sports involvement in a school-based youth cohort: Implications for long-term athletic development. Journal of Sports Science, 37(22), 2522–2529. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2019.1647032

- Lundvall, S. (2016). Approaching a gender-neutral PE culture? An exploration of the phase of a divergent PE-culture (Vol. 19, pp. 640–652). Sport in Society.

- Lusted, J. (2009). Playing games with “race”: Understanding resistance to “race” equality initiatives in English local football governance. Soccer and Society, 10(6), 722–739. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970903239941

- Lusted, J. (2011). Negative equity? Amateurist responses to race equality initiatives in English grass-roots football. In D. Burdsey (Ed.), Race, ethnicity and football: Persisting debates and emergent issues (pp. 207–221). Routledge.

- Mackintosh, C. (2021). Foundations of Sport Development. London: Routledge.

- MacNamara, A., Collins, D., Bailey, R., Toms, M., Ford, P., & Pearce, G. (2011). Promoting lifelong physical activity and high-level performance: Realizing an achievable aim for physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 16(3), 265–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2010.535200

- Martins, J., Marques, A., Rodrigues, A., Sarmento, H., Onofre, M., & Carreiro da Costa, F. (2018). Exploring the perspectives of physically active and inactive adolescents: How does physical education influence their lifestyles? Sport, Education and Society, 23(5), 505–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2016.1229290

- McGrath, C., Palmgren, P. J., & Liljedahl, M. (2018). Twelve tips for conducting qualitative research interviews. Medical Teacher Journal, 41(9), 1002–1006. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1497149

- McQueen, P., & McQueen, H. (2010). Key concepts in philosophy. Palgrave MacMillan.

- McSharry, M. (2017). It’s just because we’re girls: How female students experience and negotiate masculinist school sport. Irish Educational Studies, 36(3), 341–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2017.1327366

- Medcalf, R., & Mackintosh, C. (2019). Researching difference in sport and physical activity. Routledge.

- Mills, C., Mackintosh, C., & Bloor, M. (2022). From boardroom to tee: Understanding golf volunteers during an era of change. Sport in Society, 25(11), 2213–2233.

- Mills, J. (2014). Qualitative methodology: A practical guide. Sage.

- Nezlek, J. B., Krohn, W., Wilson, D., & Maruskin, L. (2015). Gender differences in reactions to the sexualisation of athletes. The Journal of Social Psychology, 155(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2014.959883

- O’Donnell, C., Sandford, R., & Parker, A. (2020). Physical education, school sport and looked-after-children: Health, wellbeing and educational engagement. Sport, Education and Society, 25(6), 605–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1628731

- Parnell, D., Widdop, P., Bond, A., & Wilson, R. (2020). COVID-19, networks and sport, Managing Sport and Leisure, 27, 78–84.

- Parratt, C. M. (2016). The female tradition, gender, class, sex and sport in northern England, 1960s–1970s. In D. Kirk, & P. Vertinsky (Eds.), The female tradition in physical education: Women first reconsidered (pp. 141–152). Routledge.

- Petty, K., & Pope, S. (2018). A new age for media coverage of women’s sport? An analysis of English media coverage of the 2015 FIFA women’s world Cup. Sociology, 53(3), 486–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038518797505

- Pfister, G., & Pope, S. (2018). Female football players and fans: Intruding into a man’s world. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Phelan, K. M. (2017). A question for feminist epistemology. Social Epistemology, 31(6), 514–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2017.1360409

- Pielichaty, H. (2021). Negotiating sibling relationships in girls' and womens' football. In Families, Sport, Leisure and Social Justice. London: Routledge.

- Pope, S., & Kirk, D. (2014). The role of physical education and other formative experiences of three generations of female football fans. Sport, Education and Society, 19(2), 223–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2011.646982

- Preece, S., & Bullingham, R. (2020). Gender stereotypes: the impact upon perceived roles and practice of in-service teachers in physical education. Sport, Education and Society. [Online] ‘First online’ published 20th November 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2020.1848813

- Quennerstedt, M., McCuaig, L., & Mårdhc, A. (2020). The fantasmatic logics of physical literacy. Sport Education and Society, 26(8), 846–861. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2020.1791065