ABSTRACT

Research question

Diversity and inclusion management (DIM) is central to organizational science and studies of sport’s contribution to diversity and inclusion in society are plentiful, e.g. through the “sport for development” field. But what is the status of existing research about DIM within sport organizations?

Research methods

This paper draws upon an integrative literature review of DIM in sport organizations (n = 124). Data consist of articles gathered from Web of Science and the databases of Human Kinetics, Elsevier, Taylor and Francis and SAGE.

Results and Findings

The analysis generated five categories of findings: a lack of focus on the management part of DIM; the use of “organizational culture” as an all-embracing concept; an instrumental approach to “diversity” in particular; the key role of education in improving future DIM practices in sport; and an Anglo-Saxon bias.

Implications

This article advances the idea of a relational management of “diversity” and “inclusion” in sport organizations for integrative purposes. It is proposed to examine this relational management through a social-scientific approach to three research gaps, which are key to future empirical research on DIM challenges in sport organizations.

Introduction

Since the 1990s, diversity and inclusion management (DIM) has become widespread, a popular way to increase organizational performance and to create an enjoyable working environment where everybody could feel they belonged (Hearn & Louvrier, Citation2016; Janssens & Zanoni, Citation2021). If we accept Ricco’s definition of DIM as “an organizational approach aimed at achieving better organizational results by creating a non-discriminatory, equitable and inclusive work environment” (Ricco, Citation2016, p. 335), it becomes clear that “diversity” and “inclusion” refer to different aspects of organizational life. “Diversity” is relatively easy to quantify, measure and improve, for example, in terms of the percentage of female members of a board, while “inclusion” points to the more relational, informal and human-centric qualities of a workplace. These qualities involve fair treatment, trust and belonging (Winters, Citation2014).

Despite such differences, these concepts are often used interchangeably and without sufficient operational precision in a management setting – for example, is “diversity” a means to inclusion or an end in itself (Shore et al., Citation2018)? – which affects their usefulness as guidelines to empirical studies (Adamson et al., Citation2021; Köllen, Citation2021). In terms of its diversity aims, an organization’s gender equality targets can be reached on paper, but female leaders may still be excluded from the informal parts of organizational culture (Klettner et al., Citation2016). Research has revealed that this discrepancy also exists within sport organizations (Dashper & Fletcher, Citation2013; Evans & Pfister, Citation2021; Gardner et al., Citation2022; McDowell et al., Citation2022; Piggott & Pike, Citation2020).

Yet focusing on “diversity” or “inclusion” separately ignores the mutual relation affecting the organization as a whole. It therefore becomes relevant to analyze them as mechanisms of “organizational integration”. Following Ricciardi et al. (Citation2018), this can be defined as the extent to which distinct and interdependent organizational components (for example, units, functions, mechanisms or roles) adequately respond and/or adapt to each other while pursuing common organizational goals (p. 93). Even though sport as a contributor to diversity and inclusion in society is well documented in the sport-for-development field (Collison et al., Citation2017), diversity and inclusion management in the context of organizational integration is often addressed indirectly in sport studies, judging from reviews of sport journals (Dart, Citation2014; French & Cardinal, Citation2021). Management and organization studies (MOS), a business school-oriented field (Augier et al., Citation2005; Weatherbee, Citation2012) and to some degree the disciplinary home of DIM research (Köllen, Citation2021; Ricco, Citation2016), is similarly thin on sport studies (see Lawley, Citation2020; Ryan & Dickson, Citation2018; Wolfe et al., Citation2005, for notable exceptions).

To improve DIM research in general, the objective of this article is therefore to bridge MOS and sport studies by using the review findings to explore mutual ground in analyzing organizational integration. On that basis, the article identifies key gaps for future research on DIM in sport to fill. The remainder of this article is thus as follows. In the next two sections, the theoretical context and conceptual presentation of “organizational integration”, “diversity” and “inclusion” is introduced. Then, the article turns to the materials and methods used: an integrative literature review (Snyder, Citation2019) of 124 publications included in Web of Science and in the databases of Human Kinetics, Elsevier, Taylor and Francis and SAGE. After presenting five categories of findings based on the identifiable relations between core topics in the data, a discussion follows, which outlines three broader research gaps. Filling these gaps are identified as key to further studies of DIM and organizational integration in sport.

Theoretical context: organizational integration

Between 1945 and 2000, the MOS field evolved into “a quasi-discipline of its own (…) with a standardized set of ancestors, a stylized history” (Augier et al., Citation2005, p. 85). Along the way, the MOS field has “matured and developed its own unique canon, separate from the social sciences and centred in the business school” (Weatherbee, Citation2012, p. 213). By contrast, this article argues that explorations of the relation between diversity and inclusion in a management context would benefit from a social-scientific perspective on organizational integration. Whereas the MOS field looks at organizational integration to improve efficiency and performance (Barki & Pinsonneault, Citation2005; Castañer & Ketokivi, Citation2018), the starting point here is that any social unit requires (at least) two types of integration to exist, social and system. While social integration refers to “the orderly or conflictual relationships between the actors”, system integration focuses on the compatible or incompatible/contradictory relationships between “the parts of the system” (Lockwood, Citation1964; Mouzelis, Citation1997, p. 111). The level of social integration depends on how the actors conceive the difference in question and how they behave in relation to each other. Informal norms and values influence people’s ability and desire to either accept the status quo or strive for change. The level of system integration, conversely, depends on how deeply the structural parts that facilitate cooperation within the organization are institutionalized.

These types of integration in sociological theory are not mutually exclusive, rather the opposite: they are both constraining and enabling for individuals and groups at the same time (Mouzelis, Citation1997; Sewell, Citation1992). Furthermore, “system” is not static and “social” is not in constant flux. Instead, there is an intertwined process where managerial intervention is the key resource to achieve a predictable compatibility between the two (Perkmann, Citation1998). To consider inclusion and diversity management as a possible way to handle the interplay between social and system integration, it is thus relevant to explore an organization’s emerging properties. In contrast to emergentist theories in biology and computer science, where the focus is on chemistry or technology, a social-scientific view explores the social reasons why an organization’s whole is more than the sum of its parts (Le Boutillier, Citation2013). For example, Archer (Citation1996) uses the productivity of Adam Smith’s pin-makers as an example of a power “emergent from their division of labour (relations of production) and not reducible to personal qualities like increased dexterity which did not account for the hundredfold increase in output (mass production), i.e. the relational effect” (Archer, Citation1996, p. 686, italics original). Performance in these roles, therefore, is not just an expression of individual behaviour but also operationalization of an organizational structure (Eldar-Vass, Citation2007).

For organizations with active DIM efforts, “normative types of relations that refer to the rules of behaviour that pertain to social positions in social organisations” (Le Boutillier, Citation2013, p. 211) are crucial for integrative purposes. The reason is that these relations, e.g. embedded in inclusion practices, stimulate “reflexive emergence” among agents and their structures, which according to Goldspink and Kay (Citation2010):

… results in a unique feedback path between the emergent structure and the individual agents – each agent being an observer of the structure he/she contributes to producing and the process of observation contributes to what emerges. (Goldspink & Kay, Citation2010, p. 61)

Perspectives on the concept of diversity

“Diversity” got its breakthrough as a public concept in the Western world with the American civil rights movement and civil rights legislation of the 1960s. Vertovec (Citation2012, p. 289) claims this movement “was instrumental in establishing, in public discourse as well as in government policy, the framing notion of disadvantaged minorities”. The key mechanism to redress the educational, career and life opportunities for minorities, especially Black Americans, was Affirmative Action (AA). Behind this mechanism lay the idea of “statistical proportionality”, which put simply, was about comparing the numbers of members of designated groups with the distribution of human diversity across society (Vertovec, Citation2012, p. 290). Two decades later, the scaling back of governmental responsibilities in the US made way for developing the business case for diversity with a new-found emphasis on women (Herring, Citation2009).

Since then, six facets of diversity have come to define the debate: (1) Redistribution (akin to Affirmative Action); (2) Recognition (fostering dignity and respect for minority cultures); (3) Representation (shaping institutions so that they mirror society); (4) Provision (educational awareness of “needs-led diversity”); (5) Competition (the business case for diversity); and finally, (6) Organization (diversity management policies and practices) (Vertovec, Citation2012). Yet issues quickly arose. Anthropologists discussed the relation between diversity and difference (Eriksen, Citation2006), economists disagreed about the strength of the causal relation between diversity and growth (Peck, Citation2005), and sociologists questioned the true content of “the post-civil rights mantra of equality” (Embrick, Citation2011, p. 541). Those who favoured pluralism as a moral right and saw business opportunities in strategizing diversity policies as part of the organizational identity had nevertheless wind in their sails (Herring, Citation2009).

Eventually, in organization studies, diversity was increasingly acknowledged as a context-dependent concept (Yadav & Lenka, Citation2020). Until the early 2000s, “affirmative action” after the US model did not exist in France for ethnic and racial minorities (Bender et al., Citation2010, p. 85). However, this “colour-blind” approach was supplemented by the French government in 2004 when it encouraged international businesses to introduce a “Diversity Charter” (Charte de la diversité). Four years later, a “Diversity Label” was announced, which is a public award granted to prevent discrimination and promote diversity (Bereni et al., Citation2020, p. 1943). At the same time, empirical studies of the implementation of the Diversity Charter demonstrated that “diversity” had become a catch-all approach to handle complex social processes, in which diversity was often synonymous with ethnicity and social conditions undermined by neoliberal discourse (Djabi-Saïdani & Pérugien, Citation2019; Sénac, Citation2015).

Perspectives on the concept of inclusion

Inclusion research in MOS studies grew out of diversity management debates (Roberson, Citation2006; Citation2019; Winters, Citation2014). For that reason, these concepts naturally overlap. Inclusion, in comparison with diversity, however, seems to have been less politicized throughout its modern conceptual history. Inclusion came into vogue in the 1990s and in 2015, Mor Barak (Citation2015, p. 87) claimed that “the research into inclusion is relatively new”. Partly as a response to the need for a nuanced typology of organizational characteristics (Cox, Citation1991; Thomas & Ely, Citation1996), partly as a reaction to the functionalist underpinnings of diversity studies (Fredette et al., Citation2016), inclusion became a relevant concept for those advocating the hidden value of nurturing the interaction dynamics in the workplace.

To underline this argument, one of the first in this context to empirically address the relation between diversity and inclusion was Roberson (Citation2006, p. 212) who focused on “a new rhetoric in the field of diversity, which replaces the term diversity with the term inclusion”. Drawing upon Mor Barak and Cherin (Citation1998), Roberson’s point of departure is to see inclusion as “the degree to which individuals feel a part of critical organizational processes” (Roberson, Citation2006, p. 215). Resembling this view, but using a different theoretical perspective, are Shore et al. (Citation2011) who found that inclusion differs from formal representation and recognition procedures related to diversity by exploring instead to what degree “an employee perceives that he or she is an esteemed member of the work group through experiencing treatment that satisfies his or her needs for belongingness and uniqueness” (p. 1265). Conversely, Mor Barak et al. (Citation2016) underline that:

diversity management efforts, particularly those designed to create an organizational climate for inclusion, could be influential in promoting positive outcomes of diversity such as job satisfaction, creativity, and retention while concurrently reducing negative consequences such as mistrust and miscommunication. (Mor Barak et al., Citation2016, p. 306, italics added)

The relation between diversity and inclusion from an organizational integration perspective

Existing literature treats diversity and inclusion as two sides of the same coin, although not necessarily in the context of organizational integration. O’Donovan (Citation2017, p. 20) sees inclusion as “Diversity 2.0” and argue that “the advantages associated with diversity are more likely to be realised under a culture of inclusion”. Moreover, Fredette et al. (Citation2016, p. 46) underline that “functional and social inclusion frequently interact alone and with diversity in their influence on board effectiveness, cohesion, and commitment” (italics added). At the same time, in terms of organizational integration, recognition of the emergent properties transitioned from lower-level entities (individuals or smaller groups) to higher levels (sections or even the entire organization) either comes as a result of, or despite, management activities in a specific context (Nielsen & Dane-Nielsen, Citation2010). Managing diversity is thus not the same as enhancing system integration, nor is social integration necessarily a result of managing inclusion; neither can we equate social and system integration with agency and structure, respectively (Eldar-Vass, Citation2007; Perkmann, Citation1998). As a result, the inadequate treatment of diversity and inclusion in relation to organizational integration in the MOS field, suggests the use of DIM studies in sport as one way to explore this proposition. To that end, the article now turns to the data and methods used.

Data and methods

This article is based on an integrative literature review, which aims to “synthesize the literature on a research topic in a way that enables new theoretical frameworks and perspectives to emerge” (Snyder, Citation2019, p. 335). In contrast to the 15–16 other types of literature review (Grant & Booth, Citation2009; Snyder, Citation2019), such as descriptive, scoping or systematic, the critical underpinning of the integrative approach fits with the overall aim of the article. Compared with other literature review types, the integrative one requires “a more creative collection of data, as the purpose is usually not to cover all articles ever published on the topic but rather to combine perspectives and insights from different fields or research traditions” (Snyder, Citation2019, p. 336).

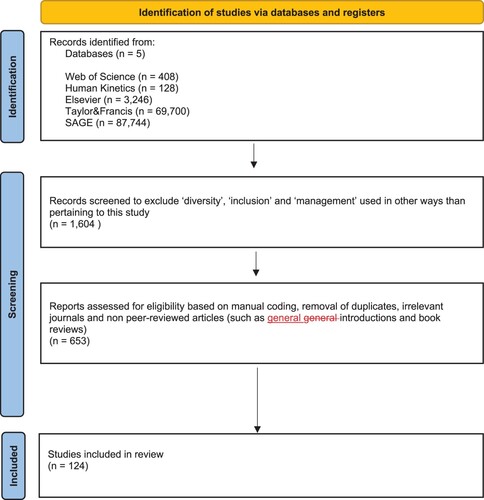

The present review is based on 124 peer-reviewed journal articles written between 1970 and 2022 generated by keyword searches in Web of Science (combinations of SPORT, DIVERSITY, INCLUSION, MANAGEMENT) and in the databases of publication houses Human Kinetics, Elsevier, Taylor and Francis and SAGE (). Web of Science was included because of its all-encompassing collection of journals, whereas the latter four were explored due to their collection of top-ranked sport-related journals. The emergence of “diversity” as a public term in the 1960s, as discussed above, dictated the selection of the time period used. The flow of this process is described in .

Table 1. Review sample (approx. here).

Three challenges occurred along the way. First, words like “diversity”, “inclusion” and “management” are used by scholars in a variety of ways. Examples of excluded studies are those concerning community inclusion, trophic diversity in a study of sport fishing, or articles using “inclusion” as part of their statistical rationale. Focusing on English-language journals only also affects the sample as the topics are discussed in Scandinavian, French and German publications. Second, the search engines of the different data sources have different sensibilities, both to the search terms and to the combination of words. For example, when using the search engine of Human Kinetics, 14 hits appeared on diversity AND inclusion. By contrast, the search generated 45 hits on “diversity”, and 67 hits on “inclusion”. Only five articles appeared when searching for diversity management and inclusion management. Sorting out the material hence led the final sample in .

Table 2. Sample characteristics.

The majority of this sample was published towards the latter end of the selected time-frame between 1991 (the first “hit” in the database) and 2022 (the data gathering ended on February 1). There are small variations in the annual number of publications on these topics until there was a jump from 2019 onwards, indicating a recently rising interest in the topic. Furthermore, the publication of articles in different journals () also indicates that diversity and inclusion management is a topic that are relevant to many fields of sport research.

The generation of analytical patterns was done by a reading of the articles with the aim of scoping their use of diversity and inclusion. Frequency measures were deemed too categorical and replaced with sense-making techniques of the data (Kuckartz, Citation2019). More specifically, this analysis was four-staged according to Kluge’s (Citation2000) model. Stage 1, relevant dimensions of analysis, was defined beforehand due to the theory-based assumption that the interchangeable use of diversity and inclusion in relation to management affected organizational integration. In stage 2, drawing upon the understanding of concepts as combinations of attributes, the search concentrated on articles with relevance for “diversity and inclusion management” on the basis of Weber’s term Kausaladaequanz, or the existence of empirical regularities and correlations (Kluge, Citation2000). In stage 3, meaningful connections, or with Weber’s term, Sinnadequanz (Chiuppesi, Citation2009), between diversity, inclusion and management were grouped into five categories of findings. In stage 4, which is represented by the Discussion section below, this convergence between empirical regularities and meaningful connections and what was missing in this picture was specified as three research gaps.

Results: five categories of findings

The findings were grouped into five, drawing upon patterns of relations in the data identified inductively by the author. The first finding is that few studies focus on DIM as defined at the beginning of this article. However, it surfaces in various combinations and under different names. The qualitative coding revealed that the four most pronounced management aspects of organizational integration were related to “governance”, “structure”, “leadership” and “culture”. Some examples are listed in , which is made in reference to the definition of DIM from the introduction to this article.

Table 3. DIM research in sport – a few examples.

A topic which cuts across these four categories is the role of boards related to recruitment, work practice, work environment and member composition. In the DIM literature in the MOS field, boards symbolize functional, cultural and personal expressions of how companies seek economic benefits (higher performance and better decisions) and push societal reform (women leaders as role models and breaking stereotypes) (Seierstad, Citation2016). Similarly, in this dataset, boards are described as tools to promote diversity in particular and yet they embody “invisible norms” (Ryan & Dickson, Citation2018), and “informal practices” (Piggott & Pike, Citation2020). Whereas most of the board studies in sport focus on gender diversity, they simultaneously treat the notion of inclusion as an implicit part of discussion. An example from the sample is Knoppers, Spaaij and Claringbould’s (Citation2021) study where four types of discursive resistance were identified: meritocracy (competence should be prioritized), neoliberalism (market demands rules), structure (that’s how the organization works), and selectiveness (gender is but one aspect of diversity). Even with quotas, the inclusion of women on boards would be highly challenging because of the “organizational habitus” of national and international sport boards. A term drawing upon the sociology of Bourdieu, this means that for historical and cultural reasons, the board of an organization “produces a form of resistance that is (unconsciously) collectively produced rather than primarily being an act by individual board members” (Knoppers, Spaaij & Claringbould, Citation2021, p. 527). As a result, it demonstrates – without saying so explicitly – that improving gender equality numerically does not necessarily lead to more inclusive cultures.

The second finding is that “organizational culture” is used as a proxy for DIM. One example from the sample is Doherty and Chelladurai (Citation1999, p. 280) who write that “the potentially constructive or destructive impact of cultural diversity is a function of the management of that diversity, which is ultimately a reflection of organizational culture, or ‘how things are done around here’.” Linking this to gender diversity and inclusion, Cunningham (Citation2008, p. 137) argues that “there are informal processes and taken-for-granted norms, values, and assumptions that are perpetuated over time. Thus, the gendered nature of sport organizations is continually reinforced.” To address this taken-for-granted-ness in organizational culture, we need to get away from the distinction between culture as something an organization has and the organization as a culture. While some MOS scholars have argued that this is not an either-or question (Ogbonna, Citation1992), this study reveals that considering “culture” as a verb could help its being addressed more profoundly in DIM research. One example from sport exposing this issue is a study of BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, and People of Color] and LGBTQI+ volunteers and diversity in the US. According to the authors:

many participants felt that DEI [Diversity, Equity and Inclusion] was not an embedded part of the culture. Though many noted that DEI had been a stated priority of the organization in recent years, they also reported that this value had not permeated all levels of the organization. (Legg & Karner, Citation2021, p. 976)

The third finding is that the DIM literature is predominantly characterized by a view of diversity management as a more or less objective tool to reach given goals. One example is given by Cunningham and Melton (Citation2011, p. 647) who posit that sexual orientation diversity contributes positively “to organizational effectiveness through three mechanisms: enhanced decision-making capabilities, improved marketplace understanding, and goodwill associated with engaging in socially responsible practices”. An even more specific example is Yiamouyiannis and Osborne’s (Citation2012) study of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA). Acknowledging the “broader issues related to the policy development process, as well as procedures and practices that serve to either support or impede women’s involvement” (p. 11), the authors also highlight that the NCAA raises its percentage of female leadership representation in line with female athlete presence (43%) to meet “its obligation to foster an inclusive culture and promote career opportunities” (Yiamouyiannis & Osborne, Citation2012, p. 2). However, whereas these findings resemble studies from the MOS field where DIM’s function is to serve business purposes (Scott-Baumann et al., Citation2019; Sénac, Citation2015), several other articles from the review sample discuss how an instrumental view can backfire if diversity is treated as a strategic element instead of an anthropological concern. Knoppers et al. (Citation2021, p. 1) argue that “an uncritical use of the concept of diversity, the invisibility of practices sustaining gender binaries and heteronormativity and the intersection of heteronormativity and White normativity, contribute to sustaining the status quo in sport organizations.” What makes the latter authors’ argument especially compelling is their data source: a subtextual analysis of 32 articles published in leading sport management journals. This kind of conceptual fuzziness can be problematic as it may widen, rather than reduce, the divide between rhetoric and reality in DIM efforts. A similar conclusion is found in Long et al.’s (Citation2005) case study of a governmental standard of best racial equality practice for sports organizations in the UK. In this framework, ethnic minorities are singled out as the “group” to be included in sport organizations through “ethnic monitoring”, normally audits of participants and paid staff members (Long et al., Citation2005, p. 48). Yet, while 62% of those engaged in the standard undertake ethnic monitoring of some kind, the low quality of this monitoring makes the entire process worthless, say the researchers, and they conclude: “It is possible for procedures to be superficially accommodated without there being any necessary organic change” (Long et al., Citation2005, p. 54).

The fourth finding is that education seems to be key to improving future DIM practices in sport. While these articles don’t necessarily examine DIM practices from within, they use much of the existing DIM literature to identify future requirements for sport managers. By focusing on what is missing from the field, these articles demonstrate a commitment to specify the terms in a managerial context. Especially in an Anglo-Saxon context, the current situation and episodes of malpractice demand more effort to make things change. Two strands are particularly debated: awareness of the complexity of the topic and pedagogical frameworks. An example of the former is Sauder et al. (Citation2021) who investigated how sport management students conceptualized diversity and inclusion with the aim of generating a more holistic perspective on the topic. It turned out that the difference between the concepts were formulated rather well by the informants (undergraduate sport management students) but predominantly attributed to race, ethnicity and gender rather than, for example, age, socio-economic status and disability. Their solution to better sport management education in the name of diversity and inclusion is a focus on three elements of “cultural competence”: awareness, knowledge and skills (Sauder et al., Citation2021, p. 8). An example of the latter strand is Leberman and Shaw (Citation2015). The conclusion of their study of female sport management graduates in New Zealand is that “there is a need to redesign existing curricula, and fundamentally change the pedagogy, by focusing more on the development of process skills, rather than on information gathering skills” (Leberman & Shaw, Citation2015, p. 363). The reason is twofold: first, students learn more about planning and organization than relation building and stakeholder management. Second, these skills learned, are derived from a socio-cultural context where employability and career adaptability are gendered to female sport management graduates’ disadvantage.

The fifth finding is DIM studies in sport, similar to those in the MOS field (Augier et al., Citation2005), suffer from an Anglo-Saxon bias which may reduce the transferability of their findings (Farndale et al., Citation2015; Ongori & Angolla, Citation2007; Theodorakopoulos & Budhwar, Citation2015), at least empirically. In total, 96 out of 124 articles – or 77.4% – belong to the Anglo-Saxon sphere. Whereas some bias was expected due to the English-based sample, it may nevertheless have practical and theoretical consequences for the study of DIM in other areas. Consider the abovementioned study by Long et al.’s (Citation2005) of how funding for sport was linked to ethnic monitoring in organizations. French law would make it difficult to adopt the same practice in French sport organizations. What is more, if it had been done, it would have to consider French quota laws, a study of which demonstrated that the Americanized HR view on diversity as business tool veiled the complexity that it was meant to unpack and utilize (Bereni et al., Citation2020, pp. 1955–1956).

Discussion: three research gaps

Seen as a whole, the findings from the literature review reveal three research gaps. First, conceptualizations of diversity and inclusion need to be more precise when used to develop an organizational integration of people and parts. However, sport studies can contribute to refinements in DIM research and enrich the conceptual debate within the MOS field. Apart from viewing the sport organization’s whole as an integrated entity whose emergent properties depend on DIM actions, it is important to treat various types of diversity differently in relation to context and situation. Much of the reviewed literature concentrates on gender diversity and female representation on boards, whereas focusing on that alone would not necessarily be sufficient to understand how to improve organizational integration. Other diversity items such as ethnicity, identity, disabilities, behavioural types or cultural preference should also be considered, either through intersectionality theories or nuances of diversity categories (Hearn & Louvrier, Citation2016). In the introduction to a special issue of Sport Management Review, the authors exemplify this claim by underlining that “Indigenous Australians have links to one or more ancestral tribes with distinctive languages and customs; they are, therefore, ethnically divergent despite being typecast in popular thought as homogeneous – whether in terms of ‘race’ or Aboriginality” (Adair et al., Citation2010, p. 2). Since it can be argued that many sport organizations in various countries consist of “diversities” (Tiesler et al., Citation2021), this pluralism will in studies affect the leeway in managing e.g. organizational culture as a “tool” to improve employees’ sense of inclusion and how the organization performs on diversity measures.

Second, prior research demonstrates the necessity of coupling inclusion and diversity to manage sport organizations in concurrence with their values and societal expectations. If we see organizational culture (cf. the second finding in the Findings section) as coordinating the sociality of DIM, sport studies consider the social science perspectives more broadly than the MOS field, which, apart from a handful of examples with Tatli’s (Citation2011, Citation2017) use of theories by the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, only applies these perspectives of diversity and inclusion to a limited degree. For example, Mor Barak argues that “workforce diversity is not about anthropological differences among individuals that make them special or unique; diversity is about belonging to groups that are different than whatever is considered mainstream in society” (Citation2015, p. 85). This position, however, misses the social inclusion/exclusion dynamics within groups and organizations that has been debated in the social sciences for decades, notably with explorations of integrative mechanisms like rituals, norms, in-group solidarism and initiation rites (Lamont & Molnàr, Citation2002; Mortensen, Citation1999; Ross, Citation1975). Related to sport, Evans and Pfister (Citation2021, p. 317) claim in their meta-study that, despite political initiatives towards gender equality in Scandinavian sport organizations, inequality remains due to “patriarchal language, gendered stereotypes and person-profiling (…) resulting in specific emotional and practical challenges for women in sports leadership positions” (see also Pfister & Radtke, Citation2006, for similar findings in German sport). A way to address this issue in an educational setting, as discussed above, could be to ask students to explore the norms of inclusion and diversity initiatives in the context of organizational integration. Knowledge about this dynamic is likely to stimulate “reflexive emergence” (Goldspink & Kay, Citation2010) and make the emerging properties of a sport organization more easily available for, for example, managers who wish to include LGBTQ strategies to develop organizational culture (Lawley, Citation2020; Romano et al., Citation2021).

Third, it is relevant to use a social-scientific approach to treat DIM as a means to an end, but necessary to avoid instrumentalization of it by combining strategic (diversity) and cultural (inclusion) concerns in the search for organizational integration. In the context of organizational integration, this furthermore means considering both the internalist and externalist expectations of proper DIM actions to sport as an institution in society (Perkmann, Citation1998). For example, Beattie and Lower-Hoppe (Citation2022), one of few studies explicitly linking diversity, inclusion and organizational culture, analyzed the transformation of Dallas Mavericks after the new CEO used organizational integration – although not named as such – as a lead motive to transform the club towards a more diverse and inclusive organization. In other words, the new CEO could not have achieved similar results in terms of organizational change if more access for the workforce to both formal and informal arenas were not enabled. The study of Dallas Mavericks thus exemplifies the necessity of harmonizing social and system integration to enhance organizational integration. Following Perkmann (Citation1998), an arena for doing so is “sites of agency”, where systemic incompatibilities can be addressed by managers, but only under certain circumstances. Yiamouyiannis and Osborne (Citation2012), for example, claim that: “Unless the power structure of the organization is committed to appropriate gender representation, there is little hope for achieving gender equity within intercollegiate athletics” (p. 11). For DIM studies, this is relevant as systemic incompatibilities are dysfunctional interactions between parts of a system (Perkmann, Citation1998, p. 495), for example, between inclusion and diversity initiatives as exemplified above with Evans and Pfister (Citation2021), which can only by rectified if perceived as dysfunctional by social actors (Perkmann, Citation1998). This, in turn, requires an organizational culture that is inclusive enough to allow such perceptions to surface and be dealt with. A broader outlook than that represented by the MOS field thus enables sport researchers to combine the multiple dimensions of both diversity and inclusion in novel ways theoretically and methodologically.

Conclusion

This article has conducted an integrative literature review (N = 124) to address the status of diversity and inclusion management (DIM) within sport organizations. The results showed that the field, overall, focuses on diversity rather than inclusion, is quite instrumental by orientation, has an Anglo-Saxon bias, problematizes the educational aspect of DIM, and shows few traces of the thinking and developments prevalent in the diversity and inclusion management field as defined at the beginning of this article. Conceptually, it therefore corresponds to some degree with the MOS field, which can be claimed to be the home of DIM research, in its treatment of “diversity” and “inclusion” in context of organizational integration. At the same time, the findings from the review reveal an empirical insight into topics relating to diversity, inclusion and the relation between them in a sport management context – for example through organizational culture – that, to a greater extent than the MOS field at present, should ignite more theoretical interest and concern for conceptual clarity with regards to organizational integration.

Researchers with an interest in this field should also consider the limitations of this review. First, the categorizations of this article are open to debate. Neither “the MOS field”, “DIM research”, nor the review sample gathered to represent “sport studies”, are well-defined entities. It should also be noted that several of the studies on organizational integration disagree with each other on aspects of emergent properties (see for example, Le Boutillier, Citation2013, for a critique of Eldar-Vass, Citation2007), which allows for new debates on the intermingling of structures, cultures and people in an organizational context. Second, due to the diversity of review methods, there are alternative ways to identify data and make analytical choices when sorting the literature review findings. Third, since the data gathering stopped in 2022 new research in sport, diversity and inclusion has been published, which sheds light on this article’s topic (see e.g. Turconi et al., Citation2022).

Despite these shortcomings, this article has used a combination of theories on organizational integration and an integrative literature review to identify three research gaps which should be filled to bridge MOS and DIM research in sport further. These gaps emerged from the review findings, which showed that while sport organizations acknowledge their role in society when it comes to promoting diversity and inclusion, there is a lot left to study regarding DIM efforts and conceptual clarity and operationalization within sport organizations. Following the discussion, the conclusion is that these gaps are most likely to be filled by a social-scientific, rather than a merely MOS-driven, approach to DIM. The reason is that the former addresses socio-cultural complexity in the name of organizational integration in a way that MOS research does not. This approach is crucial to consider because of the historical, contextual and situational characteristics of DIM in sport. A conceptually integrative outlook and theoretical underpinning connected to organizational integration as presented in this article, therefore widens the research opportunities related to DIM conceptualizations and practices.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adair, D., Taylor, T., & Darcy, S. (2010). Managing ethnocultural and “racial” diversity in sport: Obstacles and opportunities. Sport Management Review, 13(4), 307–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2010.06.002

- Adamson, M., Kelan, E., Lewis, P., Śliwa, M., & Rumens, N. (2021). Introduction: Critically interrogating inclusion in organisations. Organization, 28(2), 211–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508420973307

- Archer, M. (1996). Social integration and system integration: Developing the distinction. Sociology, 30(4), 679–699. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038596030004004

- Augier, M., March, J., & Sullivan, B. (2005). Notes on the evolution of a research community: Organization studies in Anglophone North America, 1945–2000. Organization Science, 16(1), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1040.0108

- Barki, H., & Pinsonneault, A. (2005). A model of organizational integration, implementation effort, and performance. Organization Science, 16(2), 165–179. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1050.0118. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25145958

- Beattie, M. A., & Lower-Hoppe, L. M. (2022). The Marshall plan: How diversity and inclusion transformed the Dallas mavericks’ organizational culture. Sport Management Education Journal, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1123/smej.2020-0043

- Bender, A. F., Klarsfeld, A., & Laufer, J. (2010). Equality and diversity in the French context. In A. Klarsfeld (Ed.), International handbook on diversity management at work: Country perspectives on diversity and equal treatment (pp. 83–108). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Bereni, L., Epstein, B., & Torres, M. (2020). Colour-blind diversity: How the “diversity label” reshaped anti-discrimination policies in three French local governments. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 43(11), 1942–1960. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2020.1738523

- Castañer, X., & Ketokivi, M. (2018). Toward a theory of organizational integration. Organization Design (Advances in Strategic Management), 40, 53–80. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0742-332220180000040002

- Chiuppesi, M. (2009). Indexes, scales and ideal types – a fuzzy approach. The Lab’s Quarterly, 1, 17–34. http://www.thelabs.sp.unipi.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Pasquinelli-Paolo-Some-Aspect-of-the-Quality-in-a-Living-Complex-System-2009.pdf

- Collison, H., Darnell, S., Giulianotti, R., & Howe, P. D. (2017). The inclusion conundrum: A critical account of youth and gender issues within and beyond sport for development and peace interventions. Social Inclusion, 5(2), 223–231. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v5i2.888

- Cox, T. H., Jr. (1991). The multicultural organization. Academy of Management Executive, 5, 34–47. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.1991.4274675

- Cunningham, G. B. (2008). Creating and sustaining gender diversity in sport organizations. Sex Roles, 58(1–2), 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9312-3

- Cunningham, G. B., & Melton, E. N. (2011). The benefits of sexual orientation diversity in sport organizations. Journal of Homosexuality, 58(5), 647–663. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2011.563664

- Dart, J. (2014). Sports review: A content analysis of the international review for the sociology of sport, the journal of sport and social issues and the sociology of sport journal across 25 years. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 49(6), 645–668. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690212465736

- Dashper, K., & Fletcher, T. (2013). Introduction: Diversity, equity and inclusion in sport and leisure. Sport in Society, 16(10), 1227–1232. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2013.821259

- Djabi-Saïdani, A., & Pérugien, S. (2019). The shaping of diversity management in France: An institutional change analysis. European Management Review, 17(1), 229–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/EMRE.12343

- Doherty, A. J., & Chelladurai, P. (1999). Managing cultural diversity in sport organizations: A theoretical perspective. Journal of Sport Management, 13(4), 280–297. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.13.4.280. https://journals.humankinetics.com/view/journals/jsm/13/4/article-p280.xml

- Eldar-Vass, D. (2007). For emergence: Refining archer’s account of social structure. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 37(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.2007.00325.x

- Embrick, D. G. (2011). The diversity ideology in the business world: A new oppression for a new age. Critical Sociology, 37(5), 541–556. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920510380076

- Eriksen, T. H. (2006). Diversity versus difference: Neo-liberalism in the minority debate. In R. Rottenburg, B. Schnepel, & S. Shimada (Eds.), The making and unmaking of difference (pp. 13–36). Transcript.

- Evans, A. B., & Pfister, G. U. (2021). Women in sports leadership: A systematic narrative review. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 56(3), 317–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690220911842

- Farndale, E., Biron, M., Briscoe, D. R., & Raghuram, S. (2015). A global perspective on diversity and inclusion in work organisations. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(6), 677–687. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.991511

- Fredette, C., Bradshaw, P., & Krause, H. (2016). From diversity to inclusion: A multimethod study of diverse governing groups. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 45(1), 28–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764015599456

- French, M. T., & Cardinal, B. J. (2021). Content analysis of equity, diversity, and inclusion in the recreational sports journal, 2005–2019. Recreational Sports Journal, 45(1), 69–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558866121998382

- Gardner, A., Love, A., & Waller, S. (2022). How do elite sport organizations frame diversity and inclusion? A critical race analysis. Sport Management Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/14413523.2022.2062975

- Goldspink, C., & Kay, R. (2010). Emergence in organizations: The reflexive turn. E:Co Emergence: Complexity and Organization, 12(3), 47–63.

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Hearn, J., & Louvrier, J. (2016). Theories of difference, diversity and intersectionality: What do they bring to diversity management? In R. Bendl, I. Bleijenbergh, E. Henttonen, & A. J. Mills (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of diversity in organizations (pp. 62–82). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199679805.013.28

- Herring, C. (2009). Does diversity pay? Race, gender, and the business case for diversity. American Sociological Review, 74(2), 208–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240907400203

- Janssens, M., & Zanoni, P. (2021). Making diversity research matter for social change: New conversations beyond the firm. Organization Theory, 2(2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/26317877211004603

- Klarsfeld, A., Ng, E., & Tatli, A. (2012). Social regulation and diversity management: A comparative study of France, Canada and the UK. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 18(4), 309–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959680112461091

- Klettner, A., Clarke, T., & Boersma, M. (2016). Strategic and regulatory approaches to increasing women in leadership: Multilevel targets and mandatory quotas as levers for cultural change. Journal of Business Ethics, 133(3), 395–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2069-z

- Kluge, S. (2000). Empirically grounded construction of types and typologies in qualitative social research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(1), Art. 14. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0001145

- Knoppers, A., McLachlan, F., Spaaij, R., & Smits, F. (2021). Subtexts of research on diversity in sport organizations: Queering intersectional perspectives. Journal of Sport Management. Published online ahead of print 2021. https://journals.humankinetics.com/view/journals/jsm/aop/article-10.1123-jsm.2021-0266/article-10.1123-jsm.2021-0266.xml

- Knoppers, A., Spaaij, R., & Claringbould, I. (2021). Discursive resistance to gender diversity in sport governance: sport as a unique field?. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 13(3), 517–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2021.1915848

- Köllen, T. (2021). Diversity management: A critical review and agenda for the future. Journal of Management Inquiry, 30(3), 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492619868025

- Kuckartz, U. (2019). Qualitative content analysis: From Kracauer’s beginnings to today’s challenges. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 20(3), Art. 12. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-20.3.3370

- Lamont, M., & Molnàr, V. (2002). The study of boundaries in the social sciences. Annual Review of Sociology, 28(1), 167–195. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.141107

- Lawley, S. (2020). Spaces and laces: Insights from LGBT initiatives in sporting institutions. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 33(3), 502–514. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-11-2018-0342

- Leberman, S., & Shaw, S. (2015). “Let’s be honest most people in the sporting industry are still males”: The importance of socio-cultural context for female graduates. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 67(3), 349–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2015.1057212

- Le Boutillier, S. (2013). Emergence and reduction. Journal for the Theory of Social Behavior, 43(2), 205–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/jtsb.12013

- Legg, E., & Karner, E. (2021). Development of a model of diversity, equity and inclusion for sport volunteers: An examination of the experiences of diverse volunteers for a national sport governing body. Sport, Education and Society, 26(9), 966–981. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2021.1907325

- Lockwood, D. (1964). Social integration and system integration. In G. K. Zollschan & W. Hirsch (Eds.), Explorations in social change (pp. 370–383). Routledge.

- Long, J., Robinson, P., & Spracklen, K. (2005). Promoting racial equality within sports organizations. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 29(1), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723504269883

- McDowell, J., Pickett, A. C., & Pitts, B. G. (2022). Introduction to the special issue on diversity and inclusion in sport management education. Sport Management Education Journal. Published online ahead of print 2022. https://doi.org/10.1123/smej.2022-0006

- Mor Barak, M. E. (2015). Inclusion is the key to diversity management, but what is inclusion? Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 39(2), 83–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2015.1035599

- Mor Barak, M. E., & Cherin, D. (1998). A tool to expand organizational understanding of workforce diversity. Administration in Social Work, 22(1), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1300/J147v22n01_04

- Mor Barak, M. E., Lizano, E. L., Kim, A., Duan, L., Rhee, M.-K., Hsiao, H.-Y., & Brimhall, K. C. (2016). The promise of diversity management for climate of inclusion: A state-of-the-art review and meta-analysis. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 40(4), 305–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2016.1138915

- Mortensen, N. (1999). Mapping system integration and social integration. In I. Gough & G. Olofsson (Eds.), Capitalism and social cohesion (pp. 13–37). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mouzelis, N. (1997). Social and system integration: Lockwood, Habermas, Giddens. Sociology, 31(1), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038597031001008

- Neal, J. W., & Neal, Z. P. (2013). Nested or networked? Future directions for ecological systems theory. Social Development, 22(4), 722–737. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12018

- Nielsen, C., & Dane-Nielsen, H. (2010). The emergent properties of intellectual capital: A conceptual offering. Journal of Human Resource Costing & Accounting, 14(1), 6–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/14013381011039771

- O’Donovan, D. (2017). Inclusion: Diversity management 2.0. In C. Machado & J. Davim (Eds.), Managing organizational diversity (pp. 1–28). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54925-5_1

- Ogbonna, E. (1992). Managing organisational culture: Fantasy or reality? Human Resource Management Journal, 3(2), 42–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.1992.tb00309.x

- Ongori, H., & Angolla, J. E. (2007). Critical review of literature on workforce diversity. African Journal of Business Management, 1(4), 72–76. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM.9000171

- Peck, J. (2005). Struggling with the creative class. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 29(4), 740–770. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2005.00620.x

- Perkmann, M. (1998). Social integration and system integration: Reconsidering the classical distinction. Sociology, 32(3), 491–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038598032003005

- Pfister, G., & Radtke, S. (2006). Dropping out: Why male and female leaders in German sports federations break off their careers. Sport Management Review, 9(2), 111–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1441-3523(06)70022-5

- Piggott, L. V., & Pike, E. C. (2020). “CEO equals man”: Gender and informal organizational practices in English sport governance. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 55(7), 1009–1025. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690219865980

- Ricciardi, F., Zardini, A., & Rossignoli, C. (2018). Organizational integration of the IT function: A key enabler of firm capabilities and performance. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 3(3), 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2017.02.003

- Ricco, R. (2016). Diversity management: Bringing equality, equity, and inclusion in the workplace. In J. Prescott (Ed.), Handbook of research on race, gender, and the fight for equality (pp. 335–359). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-0047-6.ch015

- Roberson, Q. M. (2006). Disentangling the meanings of diversity and inclusion in organizations. Group & Organization Management, 31(2), 212– 236. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601104273064

- Roberson, Q. M. (2019). Diversity in the workplace: A review, synthesis, and future research agenda. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 6(1), 69–88. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012218-015243

- Romano, E. K., Rich, K. A., & Quesnel, D. (2021). Leveraging sports events for LGBTQ2+ inclusion: Supporting innovation in organizational culture and practices. Case Studies in Sport Management, 10(1), 36–40. https://doi.org/10.1123/cssm.2021-0012

- Ross, J.-K. (1975). Social borders: Definitions of diversity [and comments and reply]. Current Anthropology, 16(1), 53–72. https://doi.org/10.1086/201517. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2740948

- Ryan, I., & Dickson, G. (2018). The invisible norm: An exploration of the intersections of sport, gender and leadership. Leadership, 14(3), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715016674864

- Sauder, M. H., Deluca, J. R., Mudrick, M., & Taylor, E. A. (2021). Conceptualization of diversity and inclusion: Tensions and contradictions in the sport management classroom. Journal of Hospitality Leisure Sport & Tourism Education, 29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2021.100325

- Scott-Baumann, A., Gibbs, P., Elwick, A., & Maguire, K. (2019). What do we know about the implementations of equality, diversity and inclusion in the workplace? In M. Özbilgin, F. Bartels-Ellis, & P. Gibbs (Eds.), Global diversity management. Management for professionals (pp. 11–23). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-19523-6_2

- Seierstad, C. (2016). Beyond the business case: The need for both utility and justice rationales for increasing the share of women on boards. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 24(4), 390–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12117

- Sénac, R. (2015). La promotion de la diversité dans la fonction publique: de l’héritage républicain à une méritocratie néoliberale. Revue française d'administration publique, 153(1), 165–182. https://doi.org/10.3917/rfap.153.0165

- Sewell, W. H. (1992). A theory of structure: Duality, agency, and transformation. American Journal of Sociology, 98(1). https://doi.org/10.1086/229967

- Shore, L. M., Cleveland, J. N., & Sanchez, D. (2018). Inclusive workplaces: A review and model. Human Resource Management Review, 28(2), 176–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.07.003

- Shore, L. M., Randel, A. E., Chung, B. G., Dean, M. A., Holcombe Ehrhart, K., & Singh, G. (2011). Inclusion and diversity in work groups: A review and model for future research. Journal of Management, 37(4), 1262–1289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310385943

- Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104, 333–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

- Tatli, A. (2011). A multi-layered exploration of the diversity management field: Diversity discourses, practices and practitioners in the UK. British Journal of Management, 22(2), 238–253. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2010.00730.x

- Tatli, A. (2017). Diversity management as a career: Professional identity of diversity managers as a multi-level and political construct. In J.-F. Chanlat & M. F. Özbligin (Eds.), Management and diversity (international perspectives on equality, diversity and inclusion, Vol. 4) (pp. 283–317). Emerald. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2051-233320160000004014

- Theodorakopoulos, N., & Budhwar, P. (2015). Guest editors’ introduction: Diversity and inclusion in different work settings: Emerging patterns, challenges, and research agenda. Human Resource Management, 54(2), 177–197. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21715

- Thomas, D. A., & Ely, R. J. (1996). Making differences matter: A new paradigm for managing diversity. Harvard Business Review, 74(5), 79–90.

- Tiesler, N. C., Bös, M., & Sielert, D. (2021). Thinking beyond boundaries: Researching ethnoheterogenesis in contexts of diversities and social change. New Diversities, 23(1), 1–10. https://newdiversities.mmg.mpg.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/2021_23-01_01_Editorial.pdf

- Turconi, L., Shaw, S., & Falcous, M. (2022). Examining discursive practices of diversity and inclusion in New Zealand Rugby. Sport Management Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/14413523.2021.2014182

- Vertovec, S. (2012). “Diversity” and the social imaginary. European Journal of Sociology, 53(3), 287–312. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000397561200015X

- Weatherbee, T. G. (2012). Caution! This historiography makes wide turns: Historic turns and breaks in management and organization studies. Management & Organizational History, 7(3), 203–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744935912444356

- Wieczorek-Szymańska, A. (2017). Organisational maturity in diversity management. Journal of Corporate Responsibility and Leadership, 4(1), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.12775/JCRL.2017.005

- Winters, M.-F. (2014). From diversity to inclusion: An inclusion equation. In B. M. Ferdman & B. R. Dean (Eds.), Diversity at work: The practice of inclusion (pp. 205–228). Jossey-Bass.

- Wolfe, R. A., Weick, K. E., Usher, J. M., Terborg, J. R., Poppo, L., Murrell, A. J., Dukerich, J. M., Core, D. C., Dickson, K. E., & Jourdan, J. S. (2005). Sport and organizational studies: Exploring synergy. Journal of Management Inquiry, 14(2), 182–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492605275245

- Yadav, S., & Lenka, U. (2020). Diversity management: A systematic review. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 39(8), 901–929. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-07-2019-0197

- Yiamouyiannis, A., & Osborne, B. (2012). Addressing gender inequities in collegiate sport: Examining female leadership representation within NCAA sport governance. Sage Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244012449340