ABSTRACT

Rationale/Purpose

To understand and evaluate the impact COVID-19 had on the management of grassroots cycling from the perspective of grassroots volunteers and National Governing Body (NGB) staff.

Research Approach

Virtual interviews were undertaken with eight participants made up of six grassroots volunteers and two British Cycling staff. The participants came from across England offering a range of experiences. Thematic analysis was used to identify overarching themes.

Results and Findings

Five main themes were drawn from the research, emphasising the importance of adapting to ever-changing environments to ensure the sustainability of grassroots cycling beyond the pandemic. Themes such as technology’s influence on access and societal connections have clear influence on managing return to activity.

Implications

Recommendations were made with the intention of supporting key stakeholders. These include developing stronger connections between the NGB and grassroots clubs and sharing best practices. To support these recommendations, the authors suggest practitioners might consider adopting principles associated with design thinking approaches to management, in order to overcome challenges in their environments, and to foster innovative and creative approaches.

Research Contribution

In response to calls to gather evidence from those affected by COVID-19, this research captured lived experiences of those directly involved in supporting grassroots cycling throughout the pandemic.

Introduction

Since COVID-19 triggered a United Kingdom (UK) national lockdown in March 2020, it has significantly impacted public life and how society functions, ranging from healthcare and education to the economy and travel (Bradshaw, Citation2020; Kim & Asbury, Citation2020; Lyon & Dhingra, Citation2021; Murphy et al., Citation2020). The industry of sport was no exception and did not escape the consequences stemming from lockdowns and restrictions. Sporting events at all levels, ranging from professional to grassroots were cancelled for the foreseeable future (Yeo, Citation2020). Professional sport enterprises were restricted in their offering of live sport, and grassroots sports organisations were unable to provide the benefits of physical activity (PA) to local communities (Parnell et al., Citation2020).

Acknowledging the implications for grassroots sport and participation in PA, a variety of stakeholders implemented strategies to manage the situation and to keep the nation active during lockdown. The UK government allowed the public to leave their homes once a day to exercise outdoors either alone or with members of their household (Cabinet Office, Citation2020), while Sport England introduced the “#StayInWorkOut” movement (Sport England, Citation2020). British Cycling – the National Governing Body (NGB) for cycling in Great Britain – launched a new “Virtual Ride Series” encouraging cyclists to engage in Zwift (virtual cycling platform) to ensure people remained connected with other cyclists whilst exercising from their homes (British Cycling, Citation2020). Upon sanctioned return to activity limits on number of participants, social distancing, and limits on the sharing of equipment were implemented (British Cycling, Citation2021).

In response to the call to gather more insights from those affected directly by COVID-19 (Staley et al., Citation2021), this research aims to capture the lived experiences of those directly involved in supporting grassroots cycling throughout the pandemic. This research also aims to address some of the current concerns academics have about existing research. For instance, attempts have been made in the short space of time since these events to analyse the impact of COVID-19 on the sporting sector (e.g. Findlay-King et al., Citation2020; Garcia-Garcia et al., Citation2020). However, little attention has been given to community-level sport (Evans et al., Citation2020), specifically the issues community sport clubs (CSC) have faced – and to a further degree the sport of cycling. Indeed, a swell of studies present commentary on the trends in sport participation in the wake of the pandemic (e.g. Elliott et al., Citation2021; Thibaut et al., Citation2021), but largely overlook the repercussions for those responsible for the delivery of participation opportunities.

Therefore, the purpose of this research is to develop a better understanding regarding the management of cycling during the restrictions and when activity was permitted to return, to provide an insight into how clubs adapted their practices to meet community needs (Jonker et al., Citation2012), as well as offering some practical solutions for key stakeholders. Cycling was chosen specifically because it was one of the few sports that continued in some form despite the COVID-19 restrictions.

To address this aim, design thinking has been adopted within this research to help provide practical solutions to key stakeholders. Although an established framework in the field of management for over 10 years (Elsbach & Stigliani, Citation2018; Liedtka, Citation2014; Mootee, Citation2013), design thinking has been previously truant in sport management literature (Joachim et al., Citation2020). However, such a theory has more recently been advocated as a potential framework for both profit and non-profit sports related organisations seeking to develop innovative and creative solutions (Herold et al., Citation2022; Joachim et al., Citation2021).

The following literature review explores the current state of research attached to COVID-19 in respect of existing (grassroots) sport studies, early impact on cycling participation, influence on social wellbeing, and its impact in driving alternative delivery.

Literature review

COVID-19 and (Grassroots) sport research

Perhaps due to its impact on sport, the level of academic commentary surrounding COVID-19 and sport is unrivalled (Skinner & Smith, Citation2021). Research has viewed the effect of COVID-19 from the perspective of several sport business and management fields including sports entrepreneurship (e.g. Ratten, Citation2020), sports law (e.g. Garcia-Garcia et al., Citation2020), sport politics and policy (e.g. Grix et al., Citation2021), sports media (e.g. Kasey et al., Citation2022), and sports tourism and events (e.g. Mirehie & Cho, Citation2022). However, Evans et al. (Citation2020) comment on a sparsity of scholarship focusing on community-level sport. One could thus argue that like the wider ecosystem, grassroots sport is largely forsaken to concentrate on elite sport settings (Grix et al., Citation2021). Such restricted scholarly attention into this landscape is mystifying in view of the fact grassroots sport is frequently termed the lifeblood of sport (Reade & Parnell, Citation2020) that generates substantial social, economic, physical and mental health, and individual development value (National Audit Office, Citation2022). Due to the historical and ongoing pressure to achieve more with limited resources, as well as the increased scrutiny, policy changes, and the need to demonstrate relevance within society, there is a pressing need for greater attention to be paid to grassroots sports (Dowling et al., Citation2021). This study therefore serves to add to the limited body of knowledge via understanding the links between community sport and COVID-19 through exploring the approaches to manage the pandemic from NGB to CSC level.

Doherty et al. (Citation2022 – published online 2020) first offered attention to the grassroots setting in the form of a commentary piece that drew on evidence-based insights. They attempted to link several key areas to examples of existing knowledge with the issues CSC faced in the wake of the pandemic. Key areas of contemplation, and how they could ultimately build a more resilient future for community sport, related to areas the authors had previous involvement in, specifically: assessing and building capacity; embracing innovation; and adapting top-down directives to the local context. However, this commentary piece is indicative of sport and COVID-19 research more broadly wherein a large proportion of research concerns such narratives rather than empirical study. While publications such as this are valuable to advance the research field, they may not necessarily provide a deeper insight into the industry from those experiencing it. This study begins to address this concern through offering empirical investigation into the experiences of grassroots volunteers and British Cycling staff who supported the return of cycling throughout the pandemic.

In the context of grassroots-level sport, a small number of studies have provided empirical investigation into the impact of COVID-19 (Elliott et al., Citation2021; Findlay-King et al., Citation2020; Mackintosh et al., Citation2020; Nichols et al., Citation2021; Staley et al., Citation2021). Elliott et al. (Citation2021) specifically assessed COVID-19 and the implications on participation rates and retention of youth participants (aged 15–18) in Australia from player, parent, coach, and sport administrator perspectives.

Other research has alternatively examined the challenges of returning to sport post COVID-19 from a CSC perspective (Findlay-King et al., Citation2020; Mackintosh et al., Citation2020; Staley et al., Citation2021; Nichols et al., Citation2021). Each study documented existing challenges previously reported by CSCs (e.g. Doherty et al., Citation2014; Misener & Doherty, Citation2009; Wicker & Breuer, Citation2011) were further aggravated owing to the onset of the pandemic. For instance, the studies highlighted issues concerning human resource in terms of recruitment and retention of volunteers due to heightened demands being placed on volunteers to keep CSCs operational throughout the pandemic, alongside infrastructural resources also being hampered with access to an already restricted number of facilities reducing. The studies further claimed COVID-19 created new challenges for CSCs to resolve, with how to re-engage and recruit new members (Elliott et al., Citation2021; Staley et al., Citation2021) and how this would affect social interaction (Findlay-King et al., Citation2020) being emphasised. Moreover, despite CSC attempts to return to a state seen pre-pandemic (Findlay-King et al., Citation2020), many were anxious of the ability to maintain club culture in response to new health protocols and reduced social activity (Staley et al., Citation2021).

Yet as contended by Staley et al. (Citation2021, p. 19), it is “unwise to treat CSCs as a homogenous group”. For example, culturally, CSCs vary significantly by operational formality across the UK, Germany, and Australia (Nichols et al., Citation2015). Further, CSCs are identified as heterogenous (May et al., Citation2012) and can vary in several ways including their history, their legal structure, their access to facilities, their club culture and formality, the number and demographics of participants and volunteers, their financial circumstance, and where they sit within the wider (sporting) community – each determinant impacting on how a club and sport operates. However, no study to date has focused on cycling from the perspective of those responsible for delivering at the grassroots level.

COVID-19 and cycling participation

According to Rowe et al. (Citation2016), cycling in terms of participation is a tangled landscape due to the varied cyclist typologies which range from cycling for sport purposes to cycling for recreation and commuting reasons. Yet regardless of motive, Active People’s Lives data highlights a downward trend toward cycling participation with cycling for travel in the UK decreasing by 2% within six years (November 2015–2016 to November 2020–2021), while participation in leisure and sport related cycling fell by 11% between May 2016–November 2021 (Sport England, Citation2022). To continue this shift, the number of cycling affiliated clubs has decreased from over 2200 in 2016 (British Cycling, Citation2016) to just over 1700 in 2022 (Ride London, Citation2022). Such trends are interesting given the agenda from UK government to promote cycling through £2 billion being invested to advance the cycling infrastructure in the UK (i.e. Department for Transport, Citation2020), but also Sport England’s continued commitment to growing the number of active cyclists noted in their “Towards an Active Nation” and “Uniting the Movement” strategies (Sport England, Citation2017, Citation2021a).

Given COVID-19 forced sports to change approach to operating in a short timeframe, it is likely some of the historical barriers that restrict sports participation have been perpetuated or re-emerged. For instance, reviewing how the pandemic may affect sport in society, Evans et al. (Citation2020) questioned whether COVID-19 would further exclude “at risk” groups from sport participation. Sport England (Citation2021b) reported that people with a disability, women and girls, ethnically diverse communities, and low socio-economic groups were disproportionally affected by the pandemic in terms of participation. Mackintosh et al. (Citation2020) further explored the challenges being faced when participating in sport during a pandemic concluding, with respect to cycling, those living in areas with accessible green space and accessible infrastructure such as cycle lanes became more active. This augments the earlier systematic review of Fraser and Lock (Citation2010) who observed, amongst other factors, dedicated cycling routes and paths positively affected motivation to cycle. Furthermore, Grix et al. (Citation2021) highlighted austerity measures over the last decade have led to 38% real term cuts in budgets within some local authorities. As a result, many local authorities have outsourced sporting provision, making sport participation more expensive for community members, thereby reducing accessibility for those from low socio-economic groups. Subsequently, although sporting inequality in terms of participation is not a new issue (Kay, Citation2020), it has been exacerbated by the pandemic, emphasising the need for stakeholders to collaborate even more closely than previously to address these issues.

COVID-19 and social well-being in grassroots sport

The role NGBs and CSCs play in the wider sporting ecosystem and community setting pertaining to supporting and encouraging individuals to participate in sport and PA and its resultant impact on social wellbeing should not go underestimated. Indeed, a growing consensus surrounding community sport and PA being a setting that fosters positive social benefits via bringing local communities together exists (e.g. Adams, Citation2014; Forsdike et al., Citation2019). However, when restrictions initially came into force in March 2020, mass gatherings were banned, and people could only exercise either on their own or with their household (Snowdon, Citation2020), often leading to CSCs witnessing their social glue be ripped apart (Staley et al., Citation2021). In turn, CSCs and grassroots sport faced what The International Centre for Sport Security (Citation2021) coined a “ubiquitous paradox” wherein they endeavoured to continue to engage with their local community but needed to do so through social distancing rules to arrest COVID-19 transmission.

As highlighted by Byers et al. (Citation2021) though, disruption such as COVID-19 offers an opportunity for stakeholders to reconsider their approach to delivering and managing sport at all levels. This is particularly the case given many NGBs, clubs, and sport businesses have seen their revenues drop, weakening their position overall (Garcia-Garcia et al., Citation2020). As previously alluded to, grassroot sports thus adopted a virtual approach to delivery. However, understanding how CSCs were able to continue to meet the demands of their local community during the COVID-19 period is an area yet to be properly understood. Indeed, from a social perspective, there is little consideration of what might be done to support the work being done on the ground from a sport-specific standpoint. Resultantly, this is an area explored within this research to provide others the opportunity to have an insight based on real lived experiences from British cycling and community cycling clubs, enabling practical responses to be developed to support those in need.

COVID-19 and alternative delivery

Gerrish (Citation2020) argued technology is a powerful tool to bring society together through virtual events and other virtual opportunities. From a cycling perspective, one positive British Cycling identified during the pandemic was its investment into digital products (DCMS, Citationn.d.). For instance, Zwift – an online platform employed for its ease of use and ability to connect with others globally (Zwift, Citation2020) – was deployed and saw 12,000 riders on their British Cycling Race Series (DCMS, Citationn.d.). Yet despite this, as Dyer (Citation2020) emphasises, clear challenges in accessing technology from a financial perspective alongside local internet infrastructure providing stable internet speeds exclude those from lower socio-economic backgrounds. The possible health benefits accrued through digital sport thus merely appear to reach those already more likely to participate in sport (Muntz et al., Citation2021). Being aware of these challenges provides event organisers, coaches, volunteers, and governing bodies with the opportunity to develop initiatives to combat them with the intention of improving sport and PA accessibility particularly if society faces similar challenges in the future. Indeed, creating a more equal and inclusive sporting environment are increasing requirements within Sport England’s (Citation2021a) growing agenda rhetorised in its “Uniting the movement” 10-year strategy.

In turn, working collaboratively and understanding the needs of stakeholders and participants is more important than ever before. To enable this, design thinking could be adopted as a framework providing some clarity here. The premise of design thinking surrounds making use of the thinking and doing of expert designers and applying this to non-design practitioners in a bid to focus on achieving innovation through a human-centred approach (Carlgren et al., Citation2016a; Johansson-Sköldberg et al., Citation2013). Design thinking potentially adds value for CSCs in the sense that it offers opportunities for innovation even when resources are limited (Joachim et al., Citation2020). Further, Joachim et al. (Citation2022, p. 428) outline how “traditional approaches to innovation in sport management may not always yield the best outcomes and thus new approaches (such as design thinking) are needed”. By extension, in what could be argued an unprecedented time, more unorthodox/unprecedented thinking may therefore be warranted.

Summary of review

To summarise, current studies within this area provide a useful overview of potential challenges associated with COVID-19 and grassroots sport. However, they have rarely empirically explored the current challenges being faced by both NGBs and volunteers who work with CSCs within communities in depth; instead, often drawing attention to the impact on participants. Such exploration is crucial to ensure the issues unearthed or amplified because of COVID-19 are not perpetuated further to ultimately weaken the value and contribution community sport brings to society. This study therefore examines the challenge attached to re-opening community sport from two perspectives of CSC volunteers and NGB representatives responsible for administering community sport cycling in the UK.

Research methodology

A phenomenological approach enabled the researchers the opportunity to study how a particular individual or group of people have been impacted by a particular situation or environment (Given, Citation2008). The research aimed to allow the researchers to identify key themes whilst also developing a shared understanding both with participants and the industry through the findings (Yakhlef & Essén, Citation2013). As a shared understanding was developed, a set of practical recommendations were developed to enable the workforce to improve overall (Lopez & Willis, Citation2004). The study consisted of semi-structured interviews focusing on individual experiences and how they have been impacted by a particular situation or environment (Given, Citation2008); in this case, the impact of COVID-19 on the delivery of cycling. Interviews allowed for one-to-one discussion with participants in a private setting that allowed participants to share their experiences on the topic or questions being asked (Purdy, Citation2014). The method provides flexibility (Morse, Citation2012), with eight interviews lasting between 40 and 60 min each being undertaken.

Sampling

To ensure both the perspective of the grassroot volunteers and British Cycling views were captured, a small group of grassroot volunteers from cycling clubs across England and British Cycling staff who had worked during March 2020 and March 2021 were invited for interviews. A total of six grassroots volunteers from various cycling clubs and two British Cycling staff were identified for participation through personal networks. The use of the principal investigators’ personal networks was a chief determinant in the selection of British Cycling and community cycling clubs given the challenges noted by Byers (Citation2009) in respect of accessing individuals situated in community-level sport due to scepticism in allowing researchers unknown to the organisation enter. Additionally, cycling was one of the few activities permitted to continue during the lockdowns and thus deemed to warrant further investigation.

Data analysis

Prior to analysis, interview recordings were transcribed so thematic analysis (TA) could take place using NVivo; thus, enabling the identification of key themes to be constructed (Braun & Clarke, Citation2014). Sub-themes were constructed before being organised based on commonality (Byrne, Citation2022) to produce higher-order themes revealing relationships between grassroots cycling, and how the pandemic has impacted various key stakeholders (Bryman, Citation2016). Mind maps were also used during this process to help the researchers visualise the data in a more meaningful way to support their learning and understanding (Reason, Citation2010). Preconceptions and biases, which potentially pose a greater risk within qualitative research (Tufford & Newman, Citation2012), were considered throughout the research process. Therefore, by being more self-aware of the environment and how it links to any past experiences or preconceptions, the results can be seen to be more rigorous (Sorsa et al., Citation2015).

Findings

Through the TA five key themes pertaining to the management and delivery of grassroots cycling, resulting in potential challenges for those responsible for overseeing the sport in the wake of COVID-19 were constructed. The five themes related to volunteer workforce capacity, return to activity, social connections, influence of technology on access, and developing alternative approaches – each to subsequently be discussed.

Volunteer workforce capacity

This research highlighted how the pandemic led to challenges in retaining volunteers within cycling during the pandemic. One interviewee, a club volunteer, brought this up in connection to planning cycling events:

We’ve lost several organizers. Each time we’ve had the events they have been cancelled, and then you go back to the organisers and ask: “Can you organize something now to replace it now that we can run it at a later date?” They’ve got out of the habit. People are doing other things now. (Participant 5)

Last year it was hard to make contact with new people ‘cause the obvious way to do that is when you were standing right at the coaching sessions chatting with people. Then they get involved and you can see how they can support the club. (Participant 2)

Most of our beginner stuff we’re doing is fully booked and we actually don’t have enough ride opportunities at the moment. (Participant 1)

Return to activity

British Cycling understood some clubs needed support to ensure they were both compliant with the guidelines, but also to help manage initial activity levels and the eventual return to more formal activity. To achieve this, British Cycling developed a working document called “The Way Forward” (British Cycling, Citation2021). Participant 4, from British Cycling, described how it was regularly updated in line with government announcements so clubs could plan, prepare, and deliver activity safely and legally. Here, they further highlighted how they had shared guidance across their networks, whilst also outlining how they had run webinars to provide clear guidance:

To provide additional context here, this document was shared by British Cycling to educate grassroots volunteers on the current restrictions and activity sanctioned. There were a series of webinars that were led by our HQ team, and they were across clubs, events and recreation. (Participant 4)

We did issue a letter that clubs and groups could take out with them because the problem was when there was a bit of conflict when it was groups of six meeting outside. This applied particularly when lockdown began to ease and sport activities allowed for greater groups of people [number wise]. (Participant 1)

I think that they [British Cycling] needed to be there to be contactable, to actually help deal with some of the stuff that volunteers were dealing with and didn’t really have the expertise to deal with. They even took out the regular coaches. (Participant 6)

People would be having cars driven at them because they were in a group, and they shouldn’t be doing that. They thought we were breaking the law and you get people shouting at you with reports on social media.

Social connections

As discussed within this paper so far, various academics have highlighted how grassroot sport can play an important role within in connecting people within their local communities (e.g. Adams, Citation2014; Forsdike et al., Citation2019; Moustakas, Citation2019). This was evident in the interviews with both the grassroots volunteers and British Cycling staff.

One interviewee emphasised how young people had been isolated and cut-off from their normal day-to-day routines:

I’m talking you know, 15/16-year-olds here. They have had school stopped. They didn’t know what was happening with their GCSE’s or A levels and they had their racing stopped … they had all their social contacts lost. (Participant 6)

The membership goes into a vacuum for months, you can’t go cycling (in groups) and not even making any contacts. (Participant 8)

We really missed the physical contact and being able to just sit down and have a chat about what needs to happen next. (Participant 2)

We saw a lot of people that couldn’t volunteer in their normal capacity go and do something else. So, we saw a lot of cycling clubs do fundraising events. (Participant 4)

Influence of technology on access

As this paper has already alluded to, technology played an important role throughout the pandemic in a variety of ways. The majority of those asked described it as a “blessing” based on its wide range of uses. Several volunteers mentioned how technology had enabled them to provide alternative opportunities to socialise. One highlighted how they had simply come together to have a virtual meal:

We organised a virtual club dinner. You know everybody cook their own dinner and sat down with a glass of wine. (Participant 5)

I think it’s changed how we go about cycling permanently. You know if it’s a rainy day now. Nobody comes out. They’re more than happy to sit on their trainer. (Participant 7)

It was definitely a hindrance for those who didn’t have their own bike. And then all the tech ‘cause you know if you want to buy a Turbo trainer, Zwift subscription and two devices to be able to enter [virtual events]. (Participant 2)

It became extraordinarily expensive during the pandemic because they’re [smart turbo trainers] in short supply and it’s still in fairly short supply and so you’re looking at £1000.

There’s definitely people who struggle with technology who don’t naturally do Teams meetings or Zoom. And you know, I’m not freaked out by this, but some people are. It does, tend to correlate with older people. (Participant 7)

Developing alternative approaches

When discussing with volunteers and British Cycling staff about some of the key lessons they have learnt, their willingness to be creative, adaptable, and to try new things, became clear.

One volunteer highlighted the importance of adopting a creative approach to deal with the changes occurring:

I think the message is actually trying to think creatively about new formats for things and putting them in place and giving it a go. (Participant 7)

And now we do a lot more cross team working. I think before we never realized how much we could, how many opportunities there were to work together. (Participant 1)

Discussion

The challenge of recruiting volunteers to support grassroot sport is one heavily researched pre-COVID (Schlesinger et al., Citation2015; Schlesinger & Nagel, Citation2013). The pandemic has highlighted this to be a challenge further exacerbated by the restrictions imposed to manage the spread of the virus (Staley et al., Citation2021). Further complicating matters were the restrictions on group sizes and the number of volunteer coaches needed to remain at capacity levels offered pre-COVID.

Existing academic research has highlighted the importance of face-to-face contact in maintaining a community experience within individual clubs (Lee et al., Citation2019). Whilst government restrictions were designed to protect the health and wellbeing of society, they appeared to lead to a negative impact in terms of wellbeing on community groups such as cycling clubs. Younger club members were likely to experience challenges related to loneliness and isolation, concerns about school, college or university work and a breakdown in routine (Young Minds, Citation2021). This is particularly concerning given the benefits grassroot sport can have for young people for their wellbeing, education, and support in building relationships (Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic has made sport potentially less accessible to individuals from lower socio-economic backgrounds due to the cost and availability of technology (Grix et al., Citation2021). In the past, sports clubs utilised social media platforms and their websites primarily for information sharing (Burgess et al., Citation2020), but this research has demonstrated that these platforms have now been extended to include activity delivery. The increased use of technology has allowed the sports industry to become more adaptable and responsive to its surroundings. Additionally, its greater utilisation is likely to have improved technical competence among both volunteers and staff at British Cycling due to its broader range of applications. According to Hayes (Citation2020), technology can provide a platform for small organisations to reach new and underrepresented groups, potentially increasing diversity. While academics such as Minikin (Citation2010) have argued that technology development has always been a part of grassroots sports, this paper asserts that the pandemic has acted as a catalyst for change in response to new challenges, ensuring that sports continue to serve the needs of local communities.

Age was seen as an issue in embracing technology. This would need to be investigated further, but this does perhaps relate to the work of Levy (Citation2020) who suggests sudden changes can lead to individuals feeling isolated if the support structure is not there to help them adapt. Whilst this is not most of the cycling community, it is an area both grassroot volunteers and British Cycling staff could prioritise in order to support those who have little desire to adopt new technology. One solution could be to ensure a blended approach of virtual and face-to-face activities in the future as the risks of COVID-19 are reduced over time. This will also support those with less disposable income to become re-involved in the sport again and feel part of a community.

What is also clear are the challenges both volunteers and British Cycling staff have faced when adopting technology into their environments at a rapid rate. There is a strong case to be made that some changes will be permanent; an opportunity that British Cycling could consider taking advantage of to develop the sport. One area they may seek to pursue is the promotion of the other benefits of technology adoption for those that are reluctant to return to pre-pandemic levels of activity. Others will take time to be refined or removed with the reversal to face-to-face interactions. This process however will ultimately be down to volunteers, British Cycling staff, parents/guardians, and finally, cyclists themselves. It is important that the impact of any adjustments is evaluated fully to inform future strategy and practice.

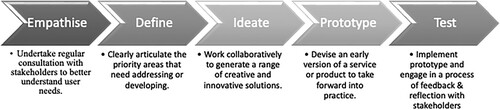

It is clear the pandemic has presented challenges and there has been an acknowledgement from club volunteers and NGB staff that for the sport to move forward there is a need to do things differently. To support this desire to become more innovative and creative, both volunteers and British Cycling staff could consider following a design thinking approach (adapted from Hasso Plattner Institute of Design below – ). Though, there is an argument to be made that they unwittingly engaged in this process to address the many challenges that they faced because of the pandemic. This finding has precedent in sport research with the work from Joachim et al. (Citation2020) similarly observing “incidental” undertaking of design thinking practices within sport for development organisations. Nevertheless, design thinking’s human-centredness, which entails the integration of user perspectives and the active involvement of users in the design process, is a critical element. A design thinking approach encourages individuals and groups/organisations to adopt creativity, innovation, and problem-solving; core elements of strategic thinking (Luchs et al., Citation2016). Joachim et al. (Citation2021) suggested that design thinking practices are desirable for sport management practices and act as a means of enhancing innovation. A design thinking approach aims to provide a potential framework from which users can use to logically work through an iterative process to identify problems and develop solutions. However, design thinking approaches have come under some criticism for being challenging to implement in the workplace, partly because managers need to emphasise to their staff a willingness to listen to new ideas (Carlgren et al., Citation2016b). Given grassroot volunteers have looked to the NGB for support throughout the pandemic, it puts British Cycling in a unique position to share this model with grassroot volunteers to support their future development.

Figure 1. Design Thinking: Grassroots Sport. Source: adapted from Hasso Plattner Institute of Design.

That said, despite the willingness for innovation and change amongst grassroot volunteers and British Cycling staff, Hoeber et al. (Citation2015) suggest radical changes are rare within CSCs. Rather CSCs should seek to adopt smaller more incremental changes to ensure its members are constantly listened too and onboard with the new approaches. To better manage changes, both British Cycling and grassroot volunteers should be aware that radical “innovative” changes take time to become the norm with members (Doherty et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, regular consultation with all stakeholders at all levels should take place which could enable process and monitoring evaluation to take place. This paper does acknowledge the challenge this may present given the challenges around volunteer workforce capacity, but the return of face-to-face social opportunities provide a valuable opportunity/ environment for this to take place.

Conclusion and recommendations

The purpose of this research was to reach out to the cycling community in England to develop an understanding of how COVID-19 has impacted the sport. By creating a snapshot of the experiences of both British Cycling regional staff and club volunteers, this research has highlighted some of their stories. Grassroots volunteers had different challenges when adopting technology, depending on their club demographics such as age and socio-economic situations. Some additional challenges identified included: volunteer workforce capacity, encouraging a return to sport participation, the impact the lack of social connections have to club members, unlocking some of the benefits technology can bring to grassroot sport delivery, but also acknowledging some of the challenges posed by rapid adoption. It has also been noted throughout this research how British Cycling staff have worked to support clubs, wherever possible. Two examples noted within this research include the use of virtual webinars and “The Way Forward” guidance. Yet, this research perhaps highlights some missed opportunities. A clear approach to developing solutions to these challenges could be to adopt the principles associated with the design thinking: grassroots sport model (). Indeed, the research has shown that the club volunteers and British Cycling staff had unwittingly done so in their practices during their return to cycling. Regular consultation with stakeholders (empathise), along with identifying priority areas (define) will enable club volunteers and British Cycling staff to work collaboratively in a creative and innovative manner, all with a view to identifying possible solutions. This could subsequently influence their strategy and the services to be put into practice (prototype). It is imperative that they view this as an iterative process and evaluate the impact of their work.

To aid this process British Cycling and grassroot clubs should continue to seek ways in which to communicate effectively with each other, and their users, the cyclists. This could be achieved in a variety of ways such as workgroups, networking opportunities, or social events, and delivery of such opportunities could be conducted virtually in a synchronous or asynchronous manner. These would provide opportunities to share best practice, experiences, and learning.

The authors recognise this research carries some limitations. Whilst British Cycling staff and club volunteers were interviewed, club members were not, leaving their experiences to be speculated rather than evidenced. A logical progression would thus be to gather insights into how COVID-19 impacted their cycling experiences, and, more importantly, their views on how British Cycling and cycling clubs managed this period. Additionally, this research focuses on the sport of cycling for reasons set out within this paper and therefore excludes other sports and their experiences. There is a need for broader research around the impact COVID-19 has had on grassroot clubs across a range of sports, as well as highlighting case studies which could look at specific underrepresented groups such as women, disabled, and the LGBTQ+ and ethnic diverse communities. The research was also a snapshot in time due to it being carried out during the pandemic. Therefore, future research could seek to re-engage with grassroots cycling clubs and British Cycling to assess the longer-term impact and changes that have occurred because of the pandemic. Finally, with the design thinking model suggested as a tool practitioners and volunteers might wish to consider, future research focusing on specific case studies where this tool has been deployed to test its value in the community could be prioritised.

To summarise, through design thinking, an understanding of how British Cycling and cycling club volunteers have navigated the COVID-19 period has been established. From this, the paper has subsequently begun to address what Evans et al. (Citation2020) stress as the need to transition from academic opinion pieces and commentaries to more empirically grounded research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adams, A. (2014). Social capital, network governance and the strategic delivery of grassroots sport in England. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 49(5), 550–574. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690212462833

- Bradshaw, A. (2020). Coronavirus culture: The questions social scientists are asking about our new day-to-day life. https://theconversation.com/coronavirus-culture-the-questions-social-scientists-are-asking-about-our-new-day-to-day-life-147771

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2014). What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 9(1), 26152. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v9.26152

- British Cycling. (2016). British Cycling reaches 125,000 members milestone. Retrieved [Online] August 16, from https://www.britishcycling.org.uk/about/article/20160815-about-bc-news-British-Cycling-reaches-125-000-members-milestone-0

- British Cycling. (2020). British Cycling launches virtual ride series. https://www.britishcycling.org.uk/road/article/20200319-road-British-Cycling-launches-virtual-ride-series-0

- British Cycling. (2021). The way forward: Planning a safe return to sanctioned cycling activity and facility use. https://www.britishcycling.org.uk/zuvvi/media/media/other/The_Way_Forward_-_Issue_1_-_April_2021.pdf

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Burgess, S., Parker, C. M., & Bingley, S. (2020). Mapping the online presence of small local sporting clubs. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 72(4), 433–448. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24423

- Byers, T. (2009). Research on voluntary sport organisations: Established themes and emerging opportunities. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, 6(2), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSMM.2009.028803

- Byers, T., Gormley, K., Winand, M., Anagnostopoulos, C., Richard, R., & Digennaro, S. (2021). COVID-19 impacts on sport governance and management: A global, critical realist perspective. Managing Sport and Leisure, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1867002

- Byrne, D. (2022). A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Quality & Quantity, 56(3), 1391–1412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y

- Cabinet Office. (2020). Staying at home and away from others (social distancing). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/full-guidance-on-staying-at-home-and-away-from-others/full-guidance-on-staying-at-home-and-away-from-others

- Carlgren, L., Elmquist, M., & Rauth, I. (2016a). The challenges of using design thinking in industry – Experiences from five large firms. Creativity and Innovation Management, 25(3), 344–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12176

- Carlgren, L., Rauth, I., & Elmquist, M. (2016b). Framing design thinking: The concept in idea and enactment. Creativity and Innovation Management, 25(1), 38–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12153

- DCMS. (n.d.). Written evidence submitted by British Cycling: Impact of Covid-19 on DCMS Sectors. [Online] https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/7587/pdf/

- Department for Transport. (2020). £2 billion package to create new era for cycling and walking. [Online] Retrieved May 9, from https://www.gov.uk/government/news/2-billion-package-to-create-new-era-for-cycling-and-walking

- Doherty, A., Millar, P., & Misener, K. (2022). Return to community sport: Leaning on evidence in turbulent times. Managing Sport and Leisure, 27(1–2), 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1794940

- Doherty, A., Misener, K., & Cuskelly, G. (2014). Toward a multidimensional framework of capacity in community sport clubs. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 43(2), 124–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764013509892

- Dowling, M., Mackintosh, C., Lee, S., & Allen, J. (2021). Community sport development: Managing change and measuring impact. Managing Sport and Leisure, 26(1–2), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1854265

- Dyer, B. (2020). Cycle E-racing: Simulation or a new frontier in sports technology? International Journal of Esports, 1(1). https://www.ijesports.org/article/38/html

- Elliott, S., Drummond, M. J., Prichard, I., Eime, R., Drummond, C., & Mason, R. (2021). Understanding the impact of COVID-19 on youth sport in Australia and consequences for future participation and retention. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 448. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10505-5

- Elsbach, K. D., & Stigliani, I. (2018). Design thinking and organizational culture: A review and framework for future research. Journal of Management, 44(6), 2274–2306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317744252

- Evans, A. B., Blackwell, J., Dolan, P., Fahlén, J., Hoekman, R., Lenneis, V., McNarry, G., Smith, M., & Wilcock, L. (2020). Sport in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic: Towards an agenda for research in the sociology of sport. European Journal for Sport and Society, 17(2), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2020.1765100

- Findlay-King, L., Reid, F., & Nichols, G. (2020). Community Sports Clubs’ response to Covid-19. [Online] Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://sway.office.com/7vwbaHlJwaF3OTlE

- Fitzpatrick, D., Parnell, D., & Drywood, E. (2020). Submission of evidence on the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on grassroots football: An agenda to protect our game and communities. Submitted to the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee. https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/7252/html/

- Forsdike, K., Marjoribanks, T., & Sawyer, A. (2019). ‘Hockey becomes like a family in itself’: Re-examining social capital through women’s experiences of a sport undergoing quasi-professionalisation. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 54(4), 479–494. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690217731292

- Fraser, S. D. S., & Lock, K. (2010). Cycling for transport and public health: A systematic review of the effect of the environment on cycling. European Journal of Public Health, 21(6), 738–743. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckq145

- Garcia-Garcia, B., James, M., Koller, D., Lindholm, J., Mavromati, D., Parrish, R., & Rodenburg, R. (2020). The impact of Covid-19 on sports: A mid-way assessment. The International Sports Law Journal, 20(3–4), 115–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40318-020-00174-8

- Gerrish, D. (2020). Together: What does Coronavirus mean for the digital future of the physical activity sector? https://www.ukactive.com/blog/together-what-does-coronavirus-mean-for-the-digital-future-of-the-physical-activity-sector/

- Given, L. M. (2008). The SAGE encyclopaedia of qualitative research methods. SAGE.

- Grix, J., Brannagan, P. M., Grimes, H., & Neville, R. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on sport. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 13(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2020.1851285

- Hasso Plattner Institute of Design. (n.d). An introduction to design thinking – PROCESS GUIDE. [Online] Stanford: Hasso Plattner Institute of Design. https://www.web.stanford.edu/~mshanks/MichaelShanks/files/509554.pdf

- Hayes, M. (2020). Social media and inspiring physical activity during COVID-19 and beyond. Managing Sport and Leisure, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1794939

- Herold, D. M., Joachim, G., Frawley, S., & Schulenkorf, N. (2022). Human-centred design thinking as a framework for sport event coordination. In Managing global sport events: Logistics and coordination (pp. 109–127). Emerald.

- Hoeber, L., Doherty, A., & Hoeber, O. (2015). The nature of innovation in community sport organizations. European Sport Management Quarterly, 15(5), 518–534. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2015.1085070

- Joachim, G., Schulenkorf, N., Schlenker, K., & Frawley, S. (2020). Design thinking and sport for development: Enhancing organizational innovation. Managing Sport and Leisure, 25(3), 175–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2019.1611471

- Joachim, G., Schulenkorf, N., Schlenker, K., Frawley, S., & Cohen, A. (2021). No idea is a bad idea: Exploring the nature of design thinking alignment in an Australian Sport Organization. Journal of Sport Management, 35(5), 381–394. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2020-0218

- Joachim, G., Schulenkorf, N., Schlenker, K., Frawley, S., & Cohen, A. (2022). “This is how I want us to think”: Introducing a design thinking activity into the practice of a sport organisation. Sport Management Review, 25(3), 428–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/14413523.2021.1948260

- Johansson-Sköldberg, U., Woodilla, J., & Çetinkaya, M. (2013). Design thinking: Past, present and possible futures. Creativity and Innovation Management, 22(2), 121–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12023

- Jonker, L., Elferink-Gemser, M., & de Roos, I. M. (2012). The role of reflection in sport expertise. The Sport Psychologist, 26(2), 224–242. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.26.2.224

- Kasey, S., Breitbarth, T., Zubcevic-Basic, N., Wilson, K., Emma, S., & Karg, A. (2022). The (un)level playing field: Sport media during COVID-19. European Sport Management Quarterly, 22(1), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2021.1925724

- Kay, T. (2021). Sport and social inequality. Observatory for Sport in Scotland. https://www.oss.scot/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Sport-Social-Inequality-Tess-Kay-review-paper-1.pdf

- Kim, L. E., & Asbury, K. (2020). “Like a rug had been pulled from under you”: The impact of COVID-19 on teachers in England during the first six weeks of the UK lockdown. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(4), 1062–1083. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12381

- Lee, M., Murphy, K., & Andrews, G. (2019). Using media while interacting face-to-face is associated with psychosocial well-being and personality traits. Psychological Reports, 122(3), 944–967. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294118770357

- Levy, A. (2020). Coronavirus: How times of crisis reveal our emotional connection with strangers. https://theconval-our-emotional-connection-with-strangers-136652

- Liedtka, J. (2014). Innovative ways companies are using design thinking. Strategy & Leadership, 42(2), 40–45. https://doi.org/10.1108/SL-01-2014-0004

- Lopez, K. A., & Willis, D. G. (2004). Descriptive versus interpretive phenomenology: Their contributions to nursing knowledge. Qualitative Health Research, 14(5), 726–735. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732304263638

- Luchs, M., Swan, S., & Griffin, A. (2016). Design thinking: New product development essentials from the PDMA. Wiley.

- Lyon, D. J., & Dhingra, S. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 and Brexit on the UK economy: Early evidence in 2021. https://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/cepcovid-19-021.pdf

- Mackintosh, C., Ives, B., & Staniford, L. (2020). COVID-19 Research Report: The impact of the Pandemic on Community Sport provision and participation. https://www.mmu.ac.uk/media/mmuacuk/content/documents/research/COVID-19-RESEARCH-REPORT-The-impact-of-the-Pandemic-on-Community-Sport-provision-and-participation.pdf

- May, T., Harris, S., & Collins, M. (2012). Implementing community sport policy: Understanding the variety of voluntary club types and their attitudes to policy. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 5(3), 397–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2012.735688

- Minikin, B. (2010). Information technology and voluntary sport organisations. In L. Robinson & R. Palmer (Eds.), Managing voluntary sport organisations (pp. 239–256). Routledge.

- Mirehie, M., & Cho, I. (2022). Exploring the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on sports tourism. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 23(3), 527–546. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSMS-04-2021-0081

- Misener, K., & Doherty, A. (2009). A case study of organizational capacity in nonprofit community sport. Journal of Sport Management, 23(4), 457–482. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.23.4.457

- Mootee, I. (2013). Design thinking for strategic innovation: What they can’t teach you at business or design school. John Wiley & Sons.

- Morse, J. (2012). The implications of interview type and structure in mixed-method designs. In J.F. Gubrium, J.A. Holstein, A.B. Marvasti, & K.D. McKinney (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of interview research: The complexity of the craft (pp. 193–205). SAGE Publications, Inc..

- Moustakas, L. (2019). Sport and social cohesion within European policy: A critical discourse analysis. European Journal for Sport and Society. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2021.2001173

- Muntz, M., Müller, J., & Reimers, A. K. (2021). Use of digital media for home-based sports activities during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from the German SPOVID survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4409. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094409

- Murphy, T., Akehurst, H., & Mutimer, J. (2020). Impact of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic on the workload of the orthopaedic service in a busy UK district general hospital. Injury, 51(10), 2142–2147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2020.07.001

- National Audit Office. (2022). Grassroots participation in sport and physical activity. [Online] Retrieved January 25, 2022, from https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Grassroots-participation-in-sport-and-physical-activity-Summary.pdf

- Nichols, G., Findlay-King, L., & Reid, F. (2021). Community Sports Clubs’ response to Covid-19, July 2020 to February 2021: Resilience and innovation. Retrieved January 25, 2023, from [Online] https://sports-volunteer-research-network.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Community-sports-clubs-response-to-C-19-April-2021.pdf

- Nichols, G. S., Wicker, P., Cuskelly, G., & Breuer, C. (2015). Measuring the formalization of community sports clubs: Findings from the UK, Germany and Australia. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 7(2), 283–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2015.1006661

- Parnell, D., Widdop, P., & Bond, A. (2020). COVID-19, networks and sport. Managing Sport and Leisure, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1750100

- Purdy, L. (2014). Interviews. In L. Nelson, R. Groom, & P. Potrac (Eds.), Research methods in sports coaching (pp. 161–170). Routledge.

- Ratten, V. (2020). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and sport entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26(6), 1379–1388. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-06-2020-0387

- Reade, J., & Parnell, D. (2020). Forget the Premier League, it’s grassroots football that we need to preserve! [Online] Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://research.reading.ac.uk/research-blog/forget-the-premier-league-its-grassroots-football-that-we-need-to-preserve/

- Reason, M. (2010). Mind maps, presentational knowledge, and the dissemination of qualitative research. ESRC Working Paper. University of Manchester.

- Ride London. (2012). Why Join a Cycling Club? [Online] 18th March, https://www.ridelondon.co.uk/training/training-hub/why-join-a-cycling-club

- Rowe, K., Shilbury, D., Ferkins, L., & Hinckson, E. (2016). Challenges for sport development: Women’s entry level cycling participation. Sport Management Review, 19(4), 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2015.11.001

- Schlesinger, T., Klenk, C., & Nagel, S. (2015). How do sport clubs recruit volunteers? Analyzing and developing a typology of decision-making processes on recruiting volunteers in sport clubs. Sport Management Review, 18(2), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2014.04.003

- Schlesinger, T., & Nagel, S. (2013). Who will volunteer? Analysing individual and structural factors of volunteering in Swiss sports clubs. European Journal of Sport Science, 13(6), 707–715. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2013.773089

- Skinner, J., & Smith, A. C. T. (2021). Introduction: Sport and COVID-19: impacts and challenges for the future (Volume 1). European Sport Management Quarterly, 21(3), 323–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2021.1925725

- Snowdon, C. (2020). Liberty after the lockdown. https://iea.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Liberty-after-the-lockdown.pdf

- Sorsa, M. A., Kiikkala, I., & Åstedt-Kurki, P. (2015). Bracketing as a skill in conducting unstructured qualitative interviews. Nurse Researcher, 22(4), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr.22.4.8.e1317

- Sport England. (2017). Active Lives Survey 2015–2016 Year 1 Report. [Online] https://www.activehw.co.uk/uploads/active-lives-survey-yr-1-report.pdf

- Sport England. (2020). Join the movement. https://www.sportengland.org/news/join-movement

- Sport England. (2021a). Uniting the movement: A 10-year vision to transform lives and communities through sport and physical activity. [Online] https://sportengland-production-files.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2021-02/Sport%20England%20-%20Uniting%20the%20Movement%27.pdf?VersionId=7JxbS7dw40CN0g21_dL4VM3F4P1YJ5RW

- Sport England. (2021b). The impact of coronavirus on activity levels revealed. [Online] Retrieved April 29, from https://www.sportengland.org/news/impact-coronavirus-activity-levels-revealed

- Sport England. (2022). Active People’s Lives Survey – Trends. [Online] https://activelives.sportengland.org/Result?queryId=72829

- Staley, K., Randle, E., Donaldson, A., Seal, E., Burnett, D., Thorn, L., Forsdike, K., & Nicholson, M. (2021). Returning to sport after a COVID-19 shutdown: Understanding the challenges facing community sport clubs. Managing Sport and Leisure, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2021.1991440

- The International Centre for Sport Security. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on grassroots sports: Experiences from a constantly changing and challenging scenario. International Centre for Sport Security.

- Thibaut, E., Constandt, B., De Bosscher, V., Willem, A., Ricour, M., & Scheerder, J. (2022). Sports participation during a lockdown. How COVID-19 changed the sports frequency and motivation of participants in club, event, and online sports. Leisure Studies, 41(4), 457–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2021.2014941

- Tufford, L., & Newman, P. (2012). Bracketing in qualitative research. Qualitative Social Work, 11(1), 80–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325010368316

- Wicker, P., & Breuer, C. (2011). Scarcity of resources in German non-profit sport clubs. Sport Management Review, 14(2), 188–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2010.09.001

- Yakhlef, A., & Essén, A. (2013). Practice innovation as bodily skills: The example of elderly home care service delivery. Organization, 20(6), 881–903. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508412458535

- Yeo, T. J. (2020). Sport and exercise during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 27(12), 1239–1241. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487320933260

- Young Minds. (2021). Coronavirus: Impact on young people with mental health needs. https://youngminds.org.uk/about-us/reports/coronavirus-impact-on-young-people-with-mental-health-needs/#covid-19-january-2021-survey

- Zwift. (2020). Zwift Raises $450 Million Investment; Series C Round Led by KKR. https://news.zwift.com/en-WW/191648-zwift-raises-450-million-investment-series-c-round-led-by-kkr