ABSTRACT

Purpose:

This study asks: (i) To what extent can VSCs be categorised in terms of their digitalisation application practices and usage perspectives, and (ii) how can the identified categories be described in terms of further organisational characteristics?

Methodology:

An online survey was conducted among VSCs in Austria and Germany. A hierarchical cluster analysis was carried out to create categories of digitalisation. N = 367 VSCs were included in the cluster analysis.

Findings:

Four categories of digitalisation were identified: “Doubters” (above-average use of digital tools, digitalisation is seen as comparatively risky), “Open Minds” (digitalisation is seen as an opportunity, high need for support), “Pessimists” (digitalisation is seen as comparatively risky), and “High Performers” (above-average use of digital tools, lowest need for support). The categories also differ in terms of organisational goals, the fit of digitalisation to the attitudes of members and the board, and in relation to the organisational culture.

Practical implications:

The categories can serve as a guideline for which direction digitalisation in the VSC should be developed. Furthermore, the categories provide a classification that could help sports federations more effectively advise their VSCs.

Research contribution:

The study complements previous findings that focus on single areas of digitalisation application by a multi-perspective analysis of digitalisation.

Introduction

Voluntary sports clubs (VSCs) generate individual and societal benefits. These include: the social inclusion of different target groups (e.g. migrants, people with disabilities) (e.g. Jeanes et al., Citation2018; Spaaij, Citation2014), the accumulation of social capital by involving individuals as members of sports clubs (e.g. Block & Gibbs, Citation2017; Smith et al., Citation2018), and wellbeing for individual sport participants through physical exercise that contributes to public health (e.g. Wicker & Thormann, Citation2021).

For VSCs to address the various tasks and challenges directed at them adequately and sustainably, they must deal with various fields of club development, such as professionalisation processes (Nagel et al., Citation2015). In particular, the implementation of digital processes in day-to-day club activities appears helpful, as digitalisation can simplify work processes and make them more efficient. In addition, internal and external communication can be improved to better procure financial resources (Herbert, Citation2017). The basis of digitalisation in organisations is the introduction of new digital tools. However, digitalisation goes beyond that, as changes induced by technological innovations require adjustments in organisational structures in terms of working methods and organisational culture (Herbert, Citation2017).

Existing studies on digitalisation in sport focus primarily on professional clubs in elite sport (Ströbel et al., Citation2021), whereby these often operate in the legal form of a corporation. In addition, most of the studies focus on eSports (see scoping review Riatti & Thiel, Citation2021). In contrast, there are only a few studies on digitalisation in VSCs. These studies focus primarily on specific aspects of digitalisation, such as specific target groups (parents and kids) (Marcenko & Nikoforova, Citation2021), or the use of digital tools to support training during the Covid-19 pandemic (Tjønndal, Citation2020). In addition, some studies focus on factors that influence digital usage behaviour in VSCs. The support of (key) members (Bingley & Burgess, Citation2012), sufficient organisational capacity (Hoeber & Hoeber, Citation2012), as well as club goals that aim at cooperation with other organisations (Ehnold et al., Citation2021) are conducive to transformative digitalisation processes in VSCs. In contrast, a lack of a digitalisation strategy (Ehnold et al., Citation2021), resistance from human resources (employees/volunteers) (Naraine & Parent, Citation2017), and a lack of familiarity with digital tools among decision-makers (Denison & Johanson, Citation2007) have a negative impact.

It is clear that comparatively few findings on digitalisation in VSCs are available, making further studies necessary to elaborate previous findings. The few available studies focus primarily on single areas of application, and findings refer to the current situation of digital usage practices. However, no findings accommodate future developments of digital application practices in VSCs using a differentiated perspective. We can presume that VSCs have different practices to deal with digitalisation due to their different characteristics, conditions, and interests. There are currently no valid findings on what these different digital practices look like and how they differ from each other.

To bridge these research gaps, it is necessary to analyse digitalisation in VSCs more comprehensively, beyond the use of individual tools. From a management perspective, it also seems useful to have a deeper understanding of the club-specific approach to digitalisation that goes beyond mere user behaviour. This could help provide more needs-based support for VSCs in realising the digital transformation process and to make the corresponding consulting processes more effective (Klenk et al., Citation2017).

Thus, the aim of this study is to examine the extent to which different application practices of digitalisation exist in VSCs that can be condensed into certain patterns of action. Therefore, this study asks: (i) To what extent can VSCs be categorised in terms of their digitalisation application practices and usage perspectives, and (ii) how can the identified categories be described in terms of further organisational characteristics?

Conceptual background

Conceptual framework to categorise digital usage practices in VSCs

There is currently no elaborated theoretical framework for the categorisation of digitalisation in VSCs (this also applies to the NPO sector in general). Therefore, appropriate criteria to analyse different forms of digitalisation application practices and usage perspectives are considered in a theory-based manner with reference to the (i) actual usage behaviour of digital tools in every-day club work and anchored in VSC reality. In addition, we focus on aspects related to (ii) the willingness and (iii) the ability of a VSC to become more digital. This approach can be justified as follows: Usage behaviour is frequently considered to categorise usage practices in commercial companies (e.g. Cominola et al., Citation2019; Kaur & Gabrijelčič, Citation2022; Scutariu et al., Citation2022), and therefore also seems appropriate in the context of sports clubs. Willingness and ability are already used in VSC research as central criteria for change processes, e.g. in relation to innovative capacity (Wemmer & Koenigstorfer, Citation2015), the implementation of sport policy programmes (Skille, Citation2008), or the design of specific integration measures (Tuchel et al., Citation2021). These criteria for change processes also apply to digitalisation.

Usage behaviour provides information on how the use of digital tools is actually reflected in an organisation, determines every-day work, and shapes club reality. Digital tools can be of great importance to VSCs, especially in the areas of general administration, tax and financial administration, and communication and public relations (Ehnold et al., Citation2021; Herbert, Citation2017). Given that VSCs are interest-based organisations that focus on the production of sport-related club goods for their members (Robinson & Palmer, Citation2010), the use of digital tools for sport-related tasks (in training and competition) must also be considered. Furthermore, due to the increasing importance of digital education and training in general (Salajan, Citation2019), the corresponding usage behaviour in the VSCs will also be considered.

In VSCs, organisational changes are often characterised by “muddling through” (Fahlén & Stenling, Citation2019). To implement digital elements in VSCs, therefore, it is important that associated processes are actively developed by the VSCs themselves (willingness) (Skille, Citation2008). Willingness increases when internal or external stimuli are compatible with previous practices and routines of the club’s work and thus generate internal relevance (Balduck et al., Citation2015; Thiel & Meier, Citation2004; Wemmer & Koenigstorfer, Citation2015). For digitalisation, relevance means that the consequences associated with digitalisation are more likely to be perceived as opportunities than risks, and that digitalisation is not rejected a priori (Thiel & Meier, Citation2004). Structural changes in VSCs, such as those associated with digitalisation, can also come about during adaptations to the environment, whereby the scale for change is “set” by the VSC itself (Skille, Citation2008). According to institutional isomorphism theory (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983), a distinction can be made between normative, coercive, and mimetic isomorphism. It is possible that some clubs experience coercive isomorphism, where sport federations either induce or prevent digitalisation. Normative isomorphism could arise when VSCs become more digital in the context of other transformative processes such as professionalisation. Furthermore, it is possible that mimetic isomorphism occurs as clubs learn from and adapt to other clubs in terms of best practice.

The ability to operate digitally is related to the deployment and allocation of assets and resources (capacities) (Doherty & Cuskelly, Citation2020; Hall et al., Citation2003) to achieve organisational goals. VSCs often do not have all the resources they need, so they must acquire missing resources from third parties (Feiler et al., Citation2019; Klenk et al., Citation2017). When VSCs report on specific support related to digitalisation, it becomes clear in which areas their own organisational capacities are considered insufficient and thus external assistance is needed. Human resources are a key asset when dealing with organisational challenges (Doherty & Cuskelly, Citation2020; Misener & Doherty, Citation2009). Therefore, providing support with digitalisation-specific knowledge (e.g. data protection, software solutions) is particularly important. In addition, financial expenses, for example for hardware and software, accompany digitalisation processes. As shown in previous research, insufficient financial resources make it more difficult for VSCs to digitalise their processes (Ehnold et al., Citation2021).

Relationship between categories of digital usage practices and club-specific characteristics

To describe the categories of digitalisation beyond the category-forming variables, their relationship to selected club-specific characteristics is considered. The analysis includes (i) club goals, (ii) club culture, (iii) attitude of the board, and (iv) attitude of the club members. These characteristics in sports club research have been shown to be essential for transformative processes in general (e.g. Doherty & Cuskelly, Citation2020; Nagel et al., Citation2015) and digitalisation processes in particular (Ehnold et al., Citation2021).

If a VSC begins to recognise opportunities of digitalisation because digital tools and processes appear suitable to support their organisational goals (Nagel, Citation2008; Thiel & Mayer, Citation2009), this should have a positive effect on implementing digital tools. There are considerable (because connectable) usage perspectives for digitalisation, especially for club goals that focus explicitly on service orientation or on interactions with external stakeholders (cooperation with schools or commercial enterprises) (Ehnold et al., Citation2021). Here, digital tools are used primarily for communicating with stakeholders (Paek et al., Citation2013) or with the aim of generating financial resources (Priante et al., Citation2021). In addition, it can be assumed that VSCs whose goals are to preserve tradition are disproportionately likely to also have cautious digitalisation practices. One explanation is that these VSCs are less focused on interaction with third parties, growth targets and service orientation play subordinate roles, and therefore the “club should stay the way it is” (Nagel, Citation2008; Nowy et al., Citation2020; Thiel & Mayer, Citation2009).

Furthermore, studies have shown that organisational culture is very important, especially regarding organisational changes (Pavlova, Citation2020; Stenling & Fahlén, Citation2016; Thiel & Meier, Citation2004). Organisational culture is “an underlying system of shared values, beliefs, and assumptions about how things are done in the organization […] formed as a result of members’ collective experiences in dealing with the universal organizational problems” (Doherty & Chelladurai, Citation1999, p. 286). If the organisational culture of a VSC is described as more traditional and conservative, this is associated with a lower willingness (lethargy) to embrace organisational change (Feiler et al., Citation2019; Thiel & Mayer, Citation2009), which has a negative impact on digitalisation processes (Schwarzmüller et al., Citation2018). Thus, the more the topic of digitalisation is seen to fit within the organisational culture and not as a potential threat to values, beliefs, and assumptions, the more likely it is that digital processes can be implemented.

The attitude of the board and the club members towards digitalisation is also used to describe the categories. In VSCs, the board has considerable discretionary scope for decision-making and action during club development processes (Thiel & Mayer, Citation2009). It can therefore be assumed that the importance of digitalisation in the VSC, as well as the concrete implementation of digital tools, are influenced by the attitude of the board as key actors in VSC development (Denison & Johanson, Citation2007; Ferkins & Shilbury, Citation2012; Hoeber & Hoeber, Citation2012). However, organisational changes can also be initiated largely by the members themselves: bottom-up. Therefore, club members’ actions play a crucial role in shaping the social structure (e.g. goals, resources, sport activities) of VSCs (Klenk et al., Citation2017; Nagel et al., Citation2015). Consequently, it can be assumed that the specific interests and needs of the members are also decisive for the extent to which digitalisation is prioritised within the club (Naraine & Parent, Citation2017). Thus, a higher level of acceptance and dissemination of digital tools within the organisational structures and processes can be expected in VSCs with members more open to digitalisation.

In addition to the listed club-specific characteristics, the relationship in terms of number of members, number of divisions, and country affiliation are included in the analysis and thus controlled.

Method

Sample

An online survey was conducted among VSCs in Austria (Styria, Vienna, Vorarlberg, and Upper Austria) and in Germany (North Rhine–Westphalia and Saxony) from September to December 2018 and in March 2019. For this purpose, all VSCs (with a valid e-mail address) in the federal states were contacted by the responsible State Sports Federation (Germany) or by the Austrian General Sport Association. The barrier to participation was thus kept as low as possible, even for clubs with less affinity for digitalisation.

Mainly club representatives in a leadership position responded to the online survey. Survey respondents included the club chair (31.6%), another board member (35.2%), or the executive director (18.9%). The survey was only completed by an office staff member in 5.5% of the cases and by another club representative in 1.3% of the cases. No respondent information was supplied in 7.5% of the cases. During this survey, a sample of n = 787 VSCs was generated (n = 453, 57.6% of the clubs were from Germany, and n = 334, 42.4% were from Austria). Both countries have strong similarities in terms of their VSCs (see below for Austria: Weiss & Norden, Citation2015; see below for Germany: Breuer et al., Citation2015). The membership rate in both countries is around 30%. Smaller VSCs with a maximum of 300 members dominate in both countries. In addition, VSCs in both countries are faced with similar challenges. These are mainly in the areas of attracting young people, acquiring volunteers, and access to sports facilities. Due to the comparable structural conditions, a joint analysis of the VSCs from both countries was carried out. In terms of the representativeness of the sample, in Germany smaller clubs (up to 300 members) are underrepresented with 50.1% compared to the population (70%), as are single-sport clubs with 40.7% compared to the population (54.1%). In Austria, smaller clubs are overrepresented with 79% compared to the population (68.1%), and single-sport clubs with 66.3% compared to the population (40%).

Measurement

Since no validated measurement instrument was available to capture the usage behaviour of digital applications/tools in VSCs, 19 usage items were defined for this purpose. The items refer to task areas that were considered in the analysis of the use of digital tools in the everyday work of NPOs (Bertenrath et al., Citation2018). Items on training/competition (Johnson, Citation2020; Torres-Ronda & Schelling, Citation2017) were also included. The following items were used: communication internal/external, reporting of membership data to federations, management of membership data, management of membership fees, game operations/organising competitions, registration of teams for game operations, organisation of training schedules, management of player/athlete licenses, accounting, application of grants and subsidies, tax declarations, planning and monitoring of training processes, match/competition analysis, human resources management, use of digital teaching materials, online learning, broadcasting sports events, volunteer management, and development of alternative revenue streams. Club representatives were asked to indicate if, and to what extent, digital tools are used in their organisations in relation to these 19 items. For valid answers, it was necessary to differentiate between use in the entire club, use in individual divisions, or no use. Thus, possible answers were (0) “no”; (1) “yes, in individual club divisions” and (2) “yes, in the entire club”.

To record perceived opportunities and risks in relation to digitalisation, the club representatives were asked the following question: “How do you rate the opportunities and risks associated with digitalisation in the following areas for your club?” In total, the opportunities and risks related to 17 areas of club work, which were designed based on general findings from NPO research (Bertenrath et al., Citation2018). Sport-specific specifications were made (e.g. gaining and maintaining sponsors, attractiveness of own sporting events). Furthermore, in contrast to Bertenrath et al. (Citation2018), the areas of club work regarding digitalisation were not assigned a priori opportunities or risks. Rather, the respondents had to assess all 17 areas of club work regarding risk versus opportunity using a bipolar Likert-scale (1 = great risks, 6 = great opportunities) (Krebs, Citation2012). This made it possible to achieve greater openness towards the subject of investigation.

Need for support was assessed using the following question: “To what extent does your club need support with digitalisation in the following areas?” In total, the need for support related to nine areas (Bertenrath et al., Citation2018), with eight areas relating to advice/training and one area to financial support. A 5-point Likert scale (1 = does not apply at all, 5 = fully applies) was used.

Organisational goals were surveyed with respect to the following goal dimensions: sport (competitive sport/mass sport), sociability, tradition, external orientation, quality/service orientation (Nagel, Citation2008; Nowy et al., Citation2020). The organisational goals were recorded on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = not important at all, 6 = very important). To describe the clusters, the analysis included the organisational goals “preservation of club tradition” and “promotion of conviviality”, which indicate rather cautious digitalisation behaviour, and the organisational goals “cooperation with other institutions”, “service orientation towards our members”, and “pioneering role in digitalisation in clubs”, which indicate progressive digitalisation behaviour.

The attitude of the members was operationalised using the statement “Our members are sceptical towards new digital technologies in the sports club” (Bertenrath et al. Citation2018). The attitude of the board was operationalised using the statement “Our board is sceptical towards new digital technologies in the sports club”. A specification was made here by explicitly asking about the board and not, as Bertenrath et al. (Citation2018) do, about employees in general.

The core of organisational culture is formed by assumptions, routines, values, and traditions, which are not usually questioned by members, but are perceived as self-evident, as having always been valid, even if individual facets often exist only as diffuse, collective ideas (Schein, Citation2016). To estimate the effect of the organisational culture on digitalisation, we formulated and used the following statement: “Digital processes do not fit with our club culture”. All items used a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all true, 5 = fully true).

Data analysis

For the following categorisation using cluster analysis, a sum score was calculated in a first step over the 19 items of usage behaviour, covering a value range from 0 to 38 points. Points were distributed for each item as follows: 0 points for no use, 1 point for single division use, and 2 points for club use (0–2 points per item).

In a second step, the variables collected regarding the opportunities and risks of digitalisation and the need for support were combined into factors. With regard to the need for support, the item “Financial support for the establishment of suitable IT infrastructure” differs significantly in content from the other eight items, which refer to the need for advice/training. Therefore, based on theoretical plausibility (Backhaus et al., Citation2018), this item represents an independent cluster variable. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was carried out using the principal component analysis (PCA) and the varimax rotation was performed with the remaining eight items and with the items on opportunities and risks of digitalisation. For opportunities and risks of digitalisation, both Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ2 (78) = 2497.93, p < 0.001) and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of sampling adequacy (KMO = 0.92) indicate that the variables are highly suitable for factor analysis (Field, Citation2009). This also applies to the need for advice/training. Here, Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ2 (28) = 2991.84, p < 0.001) and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO = 0.91) indicate similarly good values. Kaiser’s criterion (eigenvalues over 1) was considered to determine the number of extracted factors.

To measure the opportunities and risks of digitalisation, the factors outside and inside were identified, and they explain 56.5% of the variance (). The cluster variable outside comprises opportunities and risks of digitalisation that relate to areas in which there are primarily interactions with actors outside the VSC. In contrast, the cluster variable inside refers primarily to processes that are more inwardly oriented. With this factor structure, 13 out of 17 items measuring opportunities and risks of digitalisation were retained.

Table 1. Overview of the cluster variables.

Regarding the need for advice/training, a one-factor solution was found with all eight items explaining 62.6% of the variance (). The results of reliability analyses with Cronbach’s α (for the factors) and the corrected item-total correlations (for the single items) were generally good (): α values were above 0.80 and corrected item-total correlations were above 0.30 (Hair et al., Citation2010). Therefore, robust measurement was confirmed.

To perform a categorisation based on the five cluster variables, only cases with complete answers across all variables were included. In addition, outliers were eliminated from the sample. Using hierarchical cluster analysis (single linkage method with squared Euclidean distances) (Backhaus et al., Citation2018), eight such cases were identified and excluded from the following observations. After this two-stage exclusion procedure, n = 367 cases (VSCs) were considered for the further cluster analysis.

The cluster solution was determined using a hierarchical cluster analysis (Ward’s method with squared Euclidean distances). The hierarchical procedure was chosen because it does not demand the number of clusters a priori. The quality of the cluster solution was examined regarding interpretability, stability in comparison with a partitioning procedure (k-means method; Volkovich et al., Citation2013), and heterogeneity between and homogeneity within clusters (Backhaus et al., Citation2018). Z-scores were used to compare the clusters and identify meaningful differences. The mean values of the cluster variables for the respective cluster were also reported. The differences between the clusters in terms of organisational characteristics were analysed to describe the identified clusters further. This was done using the one-factorial Brown-Forsythe ANOVA with post-hoc test according to Games-Howell.

Results

Determining the optimal cluster solution

Considering the largest change in the heterogeneity measure (error sum of squares) in the dendrogram (Everitt, Citation2011), a four-cluster solution was preferred and retained based on content plausibility. The percentage of cases that were assigned to both the principal component analysis and to the partitioning cluster analysis (k-means) was good at 79.01%. Although agreement varied between 85.10% (Cluster 4) and 70.93% (Cluster 3), this was still a good result in terms of stability (Backhaus et al., Citation2018).

Using a one-factorial Brown-Forsythe ANOVA (Brown-Forsythe correction due to non-homogeneous variances), significant differences were found between clusters with regard to the cluster variables (). In addition, the Games-Howel post-hoc test illustrated that only three cluster variables were not significantly different between two clusters: Usage pattern (clusters 2 & 3), Opportunities/Risks: Outside (clusters 1 & 3), and Need for support: Advice/Training (clusters 3 & 4).

Table 2. Cluster description in terms of the cluster variables.

An indicator of homogeneity is the relationship between the cluster-specific distribution of the expected scores and the distribution in the overall group (Backhaus et al., Citation2018). The F-values measuring homogeneity were good, as most of them were below the critical level of 1 (Schendera, Citation2010). This indicator showed that the homogeneity in Cluster 4 was reduced by the factors Need for support: Finance (F = 1.34) and Need for support: Advice/Training (F = 1.51). Apart from these two indicators of incomplete homogeneity within the clusters, all remaining dispersion measures were satisfactorily low.

Description of the identified categories (cluster) of digital usage practices

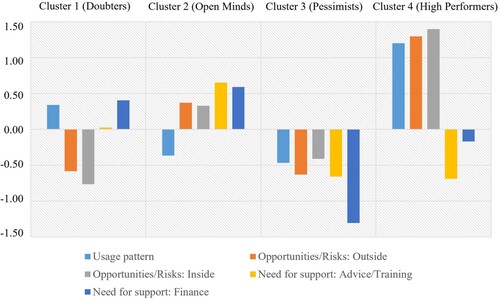

Four categories of digitalisation were identified and labelled according to the specifics of each form of digitalisation ( and ).

Cluster 1: “Doubters”(n = 98, 26.7%). This cluster showed an above-average use (z = .34; M = 19.99) of digital tools. Compared to the other three clusters, this cluster considered digitalisation riskier for external (z = −.58; M = 4.08) and for internal processes (z = −.77, M = 3.21). This category showed an average need for support regarding advice/training (z = .03, M = 3.09), and an above-average need for financial support (z = .41; M = 4.37).

Cluster 2: “Open Minds” (n = 136, 37.1%). VSCs in this cluster were characterised by below-average use of digital tools (z = −−.37; M = 14.26). However, they also considered digitalisation to be rich in opportunities for external (z = .37; M = 4.90) and internal processes (z = .33; M = 4.23). At the same time, this cluster showed the strongest need for support through advice/training (z = .65; M = 3.77) and regarding financial support (z = .59, M = 4.61).

Cluster 3: “Pessimists” (n = 86, 23.4%). This cluster showed significantly below-average values across all cluster variables. This applied to the scope of use (z = −.47, M = 13.42), the opportunities/risks assessment for external (z = −.63, M = 4.04) and internal processes (z = −.41; M = 3.55), the need for support through advice/training (z = −.66; M = 2.41), as well as the need for financial support (z = −1.31, M = 2.13).

Cluster 4: “High Performers” (n = 47, 12.8%). VSCs in this cluster showed above-average use (z = 1.20; M = 26.98) of digital tools. Likewise, digitalisation was seen as offering significantly more opportunities for both external (z = 1.30; M = 5.69) and internal processes (z = 1.40; M = 5.26) compared to the other three clusters. In contrast, VSCs in this cluster had the lowest need for support through advice/training (z = −.69; M = 2.38), and the second lowest need for financial support (z = −.17; M = 3.62).

Further characteristics of the identified digitalisation categories (cluster)

The following results were found using a one-factorial Brown-Forsythe ANOVA with post-hoc test according to Games-Howell: The analysed organisational goals “cooperation with other institutions”, “service orientation towards our members”, and “pioneering role in digitalisation in clubs” show that cluster 2 and especially cluster 4 had (significantly) higher agreement values than the other two clusters (). The approval ratings for the organisational goals “preservation of club tradition” and “promotion of conviviality”, however, were quite similar across all clusters. Cluster 4 had the lowest approval ratings, both in terms of members’ and board members’ sceptical attitudes, and in terms of non-fit with organisational culture. There were significant differences between cluster 4 and the other clusters, particularly regarding members’ sceptical attitudes and non-fit with organisational culture ().

Table 3. Characterisation of the digitalisation cluster, differentiated by organisational goals, fit with the organisational culture, fit with the attitudes of members and board, country, divisions, and number of members.

No significant differences between the clusters were identified regarding characteristics of country affiliation or number of members or divisions (). Cluster 3 (Pessimists) only showed a tendency towards above-average representation among clubs with a comparatively low number of members and in clubs from Austria. Cluster 4 (High Performers) showed a tendency towards above-average representation among multi-sports clubs and clubs from Germany.

Discussion

This study provides in-depth insights into the different application practices of digitalisation in VSCs. Since the proportions of the individual clusters range from 12.8% to 37.1%, all clusters have sufficient practical relevance without any one cluster appearing too dominant. About half of the VSCs, viewed in relative terms, tend to be pessimistic or sceptical about digitalisation (cluster 1 & cluster 3), whereby digitalisation is associated more with external rather than internal opportunities. VSCs only use the opportunities associated with digitalisation (Herbert, Citation2017; Legner et al., Citation2017) to a limited extent. In addition, the organisational goal “we want to play a pioneering role in digitalisation” is ascribed the least importance. These findings support previous studies that show VSCs are relatively reserved regarding innovative developments (Thiel & Mayer, Citation2009; Tjønndal, Citation2017; Torres-Ronda & Schelling, Citation2017; Wemmer & Koenigstorfer, Citation2015). Unlike most NPOs, whose services are provided to third parties and where the use of digital tools has therefore gained significant importance (Halpin et al., Citation2020), VSCs are more internally focussed organisations. They are often designed for tradition (preservation of the tried and established) and sociability (Thiel & Meier, Citation2004). However, as the present results show, the scope of digital tool use and openness towards digitalisation increase when VSCs pursue more externally oriented goals, or goals regarding innovation/modernisation, such as “cooperation with other institutions”, “service orientation towards members”, or the “assumption of a pioneering role in digitalisation” (cluster 2 & cluster 4). VSCs pursuing these objectives will be confronted to a greater extent with demands from internal and external stakeholders. This corresponds with the notion of normative isomorphism (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983), which fosters the implementation of digital tools in the club.

NPOs face the challenge of digitalisation, especially in providing financial and human (capabilities and skills) resources (Nahrkhalaji et al., Citation2018). As cluster 2 (Open Minds) shows, the lack of appropriate resources coincides with comparatively low levels of digital tool use, even though digitalisation is assessed as an important opportunity for VSCs.

In contrast, VSCs that already have a significantly above-average use of digital tools (cluster 4) show a below-average need for financial support. This can be explained by the fact that digital processes can be used to generate financial resources (Herbert, Citation2017), whereby the further expansion of digital infrastructures and usage options is largely self-financing. It is not surprising that the need for advice/training is highest in cluster 2 (Open Minds), as external advice is mainly sought when the challenges are considered important for the VSC and cannot be adequately addressed with internal resources (Klenk et al., Citation2017).

It is also clear that the “fit of digital processes to organisational culture” varies among the four clusters. Not surprisingly, the “Doubters” (cluster 1) and the “Pessimists” (cluster 3) felt that digitalisation processes are less compatible with the club culture. Digitalisation in organisations requires a shift towards a “digital culture” (Kokt & Makumbe, Citation2020; Pavlova, Citation2020), so that the accompanying changes, some of which can be fundamental, due to digitalisation (Frandsen, Citation2016; Schwarzmüller et al., Citation2018; Torres-Ronda & Schelling, Citation2017) can be assessed as a chance rather than a threat. It has also been shown that in VSCs where members are more positive and open towards digitalisation processes, there is also a higher degree of uptake of digital tools, because they seem to be easier to establish there (Naraine & Parent, Citation2017). There is a significant but small content effect (lower effect size) regarding the attitude of the board towards digitalisation processes. This confirms the findings of previous studies, in which the sceptical attitude of board members towards digitalisation processes was also accompanied by a more cautious approach in implementing digitalisation measures (Denison & Johanson, Citation2007; Hoeber & Hoeber, Citation2012).

No clear effects were identified for country affiliation or number of members or divisions. In addition, differences in terms of country affiliation were also attributed to differences in the sample (and population) between Germany and Austria in terms of membership and number of divisions (see sample). Although there is a slight tendency for clubs with comparatively few members to belong disproportionately to cluster 3 (Pessimists) and for multi-sport clubs to belong disproportionately to cluster 4 (High Performers), the effects are not straightforward. There are relevant and opposing effects of club size, which can “neutralize” each other in their effect. Firstly, larger VSCs with a broader range of sports have cost advantages, due to economies of scale (Wicker et al., Citation2014), which favour the digitalisation process. Secondly, larger VSCs may be more inclined to imitate other digital pioneers as best practice cases (mimetic isomorphism, DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983), especially if there is uncertainty around decisions to be taken. Thirdly, however, differences in interests between members increase in larger VSCs, which makes change processes more difficult (Wicker & Breuer, Citation2013).

Practical implications

What implications and points of awareness arise from the data and the underlying analyses regarding digitalisation application practices and usage perspectives in VSCs? First of all, it should be pointed out that although this study generates findings on digitalisation practices in VSCs, no direct strategies on the topic can be derived from it. This does not mean that no practical implications can be given, but the types of digitalisation identified cannot be used to derive general “if-then” instructions on how to deal with digitalisation in VSCs. The following central implications can be noted:

The criteria used for the cluster analysis and description provide a practical way for VSCs to record their own digitalisation application practices and usage perspectives and to compare them with other clubs. The analysis enables the VSC to draw conclusions about digitalisation in a holistic sense, as well as regarding individual criteria (“Where do we stand?”). Based on this, the current usage behaviour can be compared with potential applications of digital tools. Needs and possibilities can be addressed depending on the goals. The clusters can serve as a guideline for the direction in which digitalisation in the VSC should develop – for example, from cluster 1 to cluster 2 and finally to cluster 4 (“Where do we want to go?”). To support this development, VSCs can refer to the criteria elaborated here (“How will this be achieved”). In terms of organisational goals, for example, a stronger external focus seems appropriate. This not only creates occasions for the use of digital tools, but above all can generate resources and establish networks that support the development of resources (for digitalisation) (Doherty & Cuskelly, Citation2020; Wicker et al., Citation2013).

The present analysis can sensitise executives in the VSC (stimulation of reflection processes; Lim et al., Citation2021) to the fact that their own attitude towards digitalisation is a central success criterion for digitalisation in the VSC. As key actors, the people serving on the board play a significant role in making digitalisation a reality in the VSC. At the same time, in the course of external consultation, the attitude of the executives must be addressed in the form of functional argumentation about the advantages of digitalisation (more effective work processes, reduced workload, etc.).

The identified clusters also make clear that far-reaching digitalisation in VSCs is only possible if the members are open to it. For executives, this means strengthening member commitment to digitalisation by determining which problems can be countered by which digital tools. In addition, it is important to actively involve the members in processes of digitalisation, to reduce uncertainties and overcome reservations.

In view of the fact that VSCs that are rather pessimistic or sceptical about digitalisation (cluster 1 & cluster 3) show the strongest non-fit of the organisational culture to digital processes, neither “appeal” nor “coercive measures” seem to be effective measures for promoting digitalisation. Rather, the potential offered by digitalisation for the VSC as well as possible strategies for dealing with the challenges of digitalisation need to be presented. This can initiate a long-term cultural change towards a more “digital culture” (Kokt & Makumbe, Citation2020; Pavlova, Citation2020), which, as shown, also goes hand in hand with extensive digitalisation in the VSC.

Digitalisation practices in VSCs are accompanied by a multitude of facilitating and inhibiting factors, whereby the concrete causal relationships are still largely unclear. For VSCs and their executives, this results in the need for club-specific analyses of the current situation and future development potential, whereby the typification presented in this study offers a target-focused orientation.

The identified categories provide a classification that could help sports federations more effectively advise their VSCs by specifically addressing their respective profiles of digitalisation. The results show that some VSCs (cluster 3, Pessimists) are rather cautious in dealing with digitalisation. Since the VSCs in this cluster require below-average support in the form of advice/training and financial support, this decision does not seem to be problem-driven. Federations should therefore not prioritise this cluster regarding support or advisory projects. This also applies to cluster 4 (High Performers). VSCs in this cluster seem to cope well with the challenges of digitalisation, which is why, with comparatively high levels of use, they only require sporadic external support. In contrast, cluster 1 (Doubters) and especially cluster 2 (Open Minds) show a higher need for support. It would be a good idea for federations to provide more support to these VSCs, for example by providing low-cost (administrative) software or the possibility of financial subsidies. In addition, VSCs are increasingly asking for advice and training. With their own or mediated expertise, federations can start here and offer appropriate advice and training.

In addition, it is important for federations to reflect on the extent to which their own actions and requirements influence the use of digitalisation in VSCs. For example, available findings indicate that the prescribed use of federation software certainly increases the extent to which digital tools are used in VSCs (Ehnold et al., Citation2021), in the sense of coercive isomorphism (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983). However, this requirement does not necessarily have an impact on the importance of digitalisation in the VSC (Ehnold et al., Citation2020). Nevertheless, this can be a starting point for VSCs to implement digitalisation processes on a step-by-step basis.

Limitations and future research

It is important to note that

the data collected in this study is based on information provided by one person with management responsibilities within each organisation. This means that the member perspective remains underrepresented, which can lead to selective treatment of the topic or bias the results. This is particularly true regarding members’ attitudes towards digitalisation. Here, it is not the actual attitude that is presented, but the assumed expectations of the manager regarding the members’ attitudes towards digitalisation. This is accompanied by a validity problem. However, for the practical actions (of executives) in the VSCs, the perception of attitudes is more relevant than their actual manifestation (Klenk & Nagel, Citation2012). Further studies should start here and include the members’ perspective in the analysis of digitalisation. This would make it possible to compare data from executives and members and, by means of multi-level analyses, generate insights into the interactions at the club and member level.

Sample bias cannot be ruled out. It is possible that a disproportionate number of digitally affine VSCs participated in the study. As a result, there may have been an overestimation of opportunities and usage behaviour, which in turn could have had an impact on the size of the clusters. The size of the clusters should also be interpreted with caution for another reason, as the sample refers to individual federal states in Germany and Austria and not to the entire countries, which may limit generalisability. However, the focus of this paper is on the analysis of digitalisation types, the significance of which remains intact even with limited representativeness. Future studies should take this problem into account by including all VSCs of a country or region as the population for the empirical study. Surveys of VSCs are particularly suitable for this purpose, such as those conducted in Germany as part of the Sport Development Report or the Survey on Volunteering. These surveys are highly representative and robust against non-response bias.

It should be noted that the data in the present study were collected before the COVID-19 pandemic. To what extent digitalisation practices in VSCs have changed or continue to change because of COVID-19 should be investigated in future (longitudinal) studies. However, this study serves as a possible baseline study regarding digitalisation practices in VSCs before the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is important to critically reflect whether the cluster variables depict digitalisation practices in an overly aggregated or undifferentiated manner. This applies to the “need for financial support”, which was operationalised using only one item. On the other hand, usage behaviour is depicted using a sum score of 19 items, which prevents a differentiated consideration of various usage dimensions. In further studies, special attention should be given to the operationalisation of the variables. In particular, it should be ensured that the individual constructs that describe digitalisation behaviour in VSCs and serve as the basis for the analysis are operationalised with a comparable degree of complexity. In addition, special attention must be paid to the validity of the survey instruments to ensure that the theoretical constructs are also adequately represented from an empirical perspective.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Backhaus, K., Erichson, B., Plinke, W., & Weiber, R. (2018). Multivariate Analysemethoden [Multivariate analysis methods] (15th ed.). Springer Gabler.

- Balduck, A. L., Lucidarme, S., Marlier, M., & Willem, A. (2015). Organizational capacity and organizational ambition in nonprofit and voluntary sports clubs. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 26(5), 2023–2043. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-014-9502-x

- Bertenrath, R., Bayer, L., Fritsch, M., Lichtblau, K., Placke, B., Schmitz, E., & Schützdeller, P. (2018). Digitalisierung in NGOs. Eine Vermessung des Digitalisierungsstands von NGOs in Deutschland [Digitalisation in NGOs. A measurement of the digitalisation status of NGOs in Germany]. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from https://www.iwconsult.de/fileadmin/user_upload/projekte/2018/Digital_Atlas/Digitalisierung_in_NGOs.pdf

- Bingley, S., & Burgess, S. (2012). A case analysis of the adoption of Internet applications by local sporting bodies in New Zealand. International Journal of Information Management, 32(1), 11–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2011.05.001

- Block, K., & Gibbs, L. (2017). Promoting social inclusion through sport for refugee-background youth in Australia: Analysing different participation models. Social Inclusion, 5(2), 91–100. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v5i2.903

- Breuer, C., Feiler, S., & Wicker, P. (2015). Sports clubs in Germany. In C. Breuer, R. Hoekman, S. Nagel & H. van der Werff (Eds.), Sport in Europe. A cross-national comparative perspective (pp. 187–208). Springer International Publishing.

- Cominola, A., Nguyen, K., Giuliani, M., Stewart, R. A., Maier, H. R., & Castelletti, A. (2019). Data mining to uncover heterogeneous water use behaviors from smart meter data. Water Resources Research, 55(11), 9315–9333. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019WR024897

- Denison, T., & Johanson, G. (2007). Surveys of the use of information and communications technologies by community-based organisations. The Journal of Community Informatics, 3(2), 2. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from https://openjournals.uwaterloo.ca/index.php/JoCI/article/view/2378/2926

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

- Doherty, A., & Cuskelly, G. (2020). Organisational capacity and performance of community sport clubs. Journal of Sport Management, 34(3), 240–259. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2019-0098

- Doherty, A. J., & Chelladurai, P. (1999). Managing cultural diversity in sport organizations: A theoretical perspective. Journal of Sport Management, 13(4), 280–297. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.13.4.280

- Ehnold, P., Faß, E., Steinbach, D., & Schlesinger, T. (2021). Digitalization in organized sport – Usage of digital instruments in voluntary sports clubs depending on club’s goals and organizational capacity. Sport, Business and Management, 11(1), 28–53. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-10-2019-0081

- Ehnold, P., Steinbach, D., & Schlesinger, T. (2020). Priorität oder Randerscheinung? Eine Analyse zur Relevanz der Digitalisierung in Sportvereinen [Priority or marginal phenomenon? An analysis of the relevance of digitalization in voluntary sports clubs]. Sport und Gesellschaft, 17(3), 231–261. https://doi.org/10.1515/sug-2020-0016

- Everitt, B. (2011). Cluster analysis (Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics) (5th ed.). Wiley.

- Fahlén, J., & Stenling, C. (2019). (Re)conceptualizing institutional change in sport management contexts: The unintended consequences of sport organizations’ everyday organizational life. European Sport Management Quarterly, 19(2), 265–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2018.1516795

- Feiler, S., Wicker, P., & Breuer, C. (2019). Public subsidies for sports clubs in Germany: Funding regulations vs. empirical evidence. European Sport Management Quarterly, 19(5), 562–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2018.1541915

- Ferkins, L., & Shilbury, D. (2012). Good boards are strategic: What does that mean for sport governance? Journal of Sport Management, 26(1), 67–80. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.26.1.67

- Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS (Introducing Statistical Methods Series) (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Frandsen, K. (2016). Sports organizations in a new wave of mediatization. Communication & Sport, 4(4), 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167479515588185

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Hall, M. H., Andrukow, A., Barr, C., Brock, K., de Wit, M., & Embuldeniya, D. (2003). The capacity to serve: A qualitative study of the challenges facing Canada’s nonprofit and voluntary organizations. Canadian Centre for Philanthropy.

- Halpin, D. R., Fraussen, B., & Ackland, R. (2020). Which audiences engage with advocacy groups on Twitter? Explaining the online engagement of elite, peer, and mass audiences with advocacy groups. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 50(4), 842–865. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764020979818

- Herbert, L. (2017). Digital transformation: Build your organization’s future for the innovation age. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Hoeber, L., & Hoeber, O. (2012). Determinants of an innovation process: A case study of technological innovation in a community sport organization. Journal of Sport Management, 26(3), 213–223. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.26.3.213

- Jeanes, R., Spaaij, R., Magee, J., Farquharson, K., Gorman, S., & Lusher, D. (2018). ‘Yes we are inclusive’: Examining provision for young people with disabilities in community sport clubs. Sport Management Review, 21(1), 38–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2017.04.001

- Johnson, A. (2020). Manufacturing invisibility in “the field” distributed ethics, wearable technologies, and the case of exercise physiology. In J. J. Sterling, & M. G. McDonald (Eds.), Sports, society, and technology: Bodies, practices, and knowledge production (1st ed., pp. 41–72). Springer.

- Kaur, R., & Gabrijelčič, D. (2022). Behavior segmentation of electricity consumption patterns: A cluster analytical approach. Knowledge-Based Systems, 251, 109236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2022.109236

- Klenk, C., Egli, B., & Schlesinger, T. (2017). Exploring how voluntary sports clubs implement external advisory inputs. Managing Sport and Leisure, 22(1), 70–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2017.1386587

- Klenk, C., & Nagel, S. (2012). Freiwillige Sportorganisationen als Interessenorganisationen?! Ursachen und Auswirkungen von Ziel-Interessen-Divergenzen in Verbänden und Vereinen [Sports clubs as mutual interest organizations? Causes and effects of divergences between club goals and member interests in volunteer sports organization]. Sport und Gesellschaft, 9(1), 3–37. https://doi.org/10.1515/sug-2012-0102

- Kokt, D., & Makumbe, W. (2020). Towards the innovative university: What is the role of organisational culture and knowledge sharing? SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 18. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v18i0.1325

- Krebs, D. (2012). The impact of response format on attitude measurement. In S. Salzborn, E. Davidov & J. Reinecke (Eds.), Methods, theories, and empirical applications in the social sciences: Festschrift for Peter Schmidt (pp. 105–113). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Legner, C., Eymann, T., Hess, T., Matt, C., Böhmann, T., Drews, P., Mädche, A., Urbach, N., & Ahlemann, F. (2017). Digitalization: Opportunity and challenge for the business and information systems engineering community. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 59(4), 301–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-017-0484-2

- Lim, S., Brower, R. S., & Berlan, D. G. (2021). Interpretive leadership skill in meaning-making by nonprofit leaders. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 32(2), 307–328. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21477

- Marcenko, I., & Nikoforova, A. (2021). Digitalization in sports to connect child’s sport clubs, parents and kids: Simple solution for tackling social and psychological issues. In S. Cherfi, A. Perini & S. Nurcan (Eds.), Research challenges in information science: 15th International conference, RCIS 2021, Limassol, Cyprus, May 11–14, 2021, Proceedings (Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing, 415, B and 415) (pp. 595–601). Springer.

- Misener, K., & Doherty, A. (2009). A case study of organisational capacity in nonprofit community sport. Journal of Sport Management, 23(4), 457–482. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.23.4.457

- Nagel, S. (2008). Goals of sports clubs. European Journal for Sport and Society, 5(2), 121–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2008.11687815

- Nagel, S., Schlesinger, T., Wicker, P., Lucassen, J., Hoekmann, R., van der Weerf, H., & Breuer, C. (2015). Theoretical framework. In C. Breuer, R. Hoekman, S. Nagel & H. van der Werff (Eds.), Sport in Europe. A cross-national comparative perspective (pp. 14–36). Springer.

- Nahrkhalaji, S. S., Shafiee, S., Shafiee, M., & Hvam, L. (2018). Challenges of digital transformation: The case of the non-profit sector. 2018 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM) (pp. 1245–1249).

- Naraine, M. L., & Parent, M. M. (2017). Examining social media adoption and change to the stakeholder communication paradigm in not-for-profit sport organizations. Journal of Amateur Sport, 3(2), 55–81. https://doi.org/10.17161/jas.v3i2.6492

- Nowy, T., Feiler, S., & Breuer, C. (2020). Investigating grassroots sports’ engagement for refugees: Evidence from voluntary sports clubs in Germany. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 44(1), 22–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723519875889

- Paek, H., Hove, T., Jung, Y., & Cole, R. T. (2013). Engagement across three social media platforms: An exploratory study of a cause-related PR campaign. Public Relations Review, 39(5), 526–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2013.09.013

- Pavlova, E. (2020). Enhancing the organisational culture related to cyber security during the university digital transformation. Information & Security: An International, 46(3), 239–249. https://doi.org/10.11610/isij.4617

- Priante, A., Ehrenhard, M. L., van den Broek, T., Need, A., & Hiemstra, D. (2021). “Mo” together or alone? Investigating the role of fundraisers’ networks in online peer-to-peer fundraising. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 51(5), 986–1009. https://doi.org/10.1177/08997640211057456

- Riatti, P., & Thiel, A. (2021). The societal impact of electronic sport: A scoping review. German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research, 52(6), 433–446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12662-021-00784-w

- Robinson, L., & Palmer, D. (2010). Managing voluntary sport organisations. Routledge.

- Salajan, F. D. (2019). Building a policy space via mainstreaming ICT in European education: The European Digital Education Area (re)visited. European Journal of Education, 54(4), 591–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12362

- Schein, E. H. (2016). Organizational culture and leadership (5th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Schendera, C. F. G. (2010). Clusteranalyse mit SPSS: Mit Faktorenanalyse [Cluster analysis with SPSS. With factor analysis]. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from http://www.oldenbourg-link.com/isbn/9783486710526

- Schwarzmüller, T., Brosi, P., Duman, D., & Welpe, I. M. (2018). How does the digital transformation affect organizations? Key themes of change in work design and leadership. Management Revue, 29(2), 114–138. https://doi.org/10.5771/0935-9915-2018-2-114

- Scutariu, A.-L., Susu, S., Huidumac-Petrescu, C.-E., & Gogonea, R.-M. (2022). A cluster analysis concerning the behavior of enterprises with E-commerce activity in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce, 17(1), 47–68. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer17010003

- Skille, E. Å. (2008). Understanding sport clubs as sport policy implementers. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 43(2), 181–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690208096035

- Smith, R., Spaaij, R., & McDonald, B. (2018). Migrant integration and cultural capital in the context of sport and physical activity: A systematic review. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 20(3), 851–868. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-018-0634-5

- Spaaij, R. (2014). Refugee youth, belonging and community sport. Leisure Studies, 34(3), 303–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2014.893006

- Stenling, C., & Fahlén, J. (2016). Same same, but different? Exploring the organisational identities of Swedish voluntary sports: Possible implications of sports clubs’ self-identification for their role as implementers of policy objectives. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 51(7), 867–883. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690214557103

- Ströbel, T., Stieler, M., & Stegmann, P. (2021). Digital transformation in sport: The disruptive potential of digitalization for sport management research. Sport, Business & Management, 11(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-03-2021-124

- Thiel, A., & Mayer, J. (2009). Characteristics of voluntary sports clubs management: A sociological perspective. European Sport Management Quarterly, 9(1), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184740802461744

- Thiel, A., & Meier, H. (2004). Überleben durch Abwehr – Zur Lernfähigkeit des Sportvereins [Survival through resistance – About the learning capability of sports organizations]. Sport und Gesellschaft, 1(2), 103–124. https://doi.org/10.1515/sug-2004-0202

- Tjønndal, A. (2017). Sport innovation: Developing a typology. European Journal for Sport and Society, 14(4), 291–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2017.1421504

- Tjønndal, A. (2020). #Quarantineworkout: The use of digital tools and online training among boxers and boxing coaches during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2020.589483

- Torres-Ronda, L., & Schelling, X. (2017). Critical process for the implementation of technology in sport organizations. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 39(6), 54–59. https://doi.org/10.1519/SSC.0000000000000339

- Tuchel, J., Burrmann, U., Nobis, T., Michelini, E., & Schlesinger, T. (2021). Practices of German voluntary sports clubs to include refugees. Sport in Society, 24(4), 670–692. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2019.1706491

- Volkovich, Z., Toledano-Kitai, D., & Weber, G.–W. (2013). Self-learning K-means clustering: A global optimization approach. Journal of Global Optimization, 56(2), 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10898-012-9854-y

- Weiss, O., & Norden, G. (2015). Sport clubs in Australia. In C. Breuer, R. Hoekman, S. Nagel, & H. van der Werff (Eds.), Sports economics, management and policy: Vol. 12. Sport clubs in Europe: A cross-national comparative perspective (pp. 29–45). Springer International Publishing.

- Wemmer, F., & Koenigstorfer, J. (2015). Open innovation in nonprofit sports vlubs. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27(4), 1923–1949. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-015-9571-5

- Wicker, P., & Breuer, C. (2013). Understanding the importance of organisational resources to explain organisational problems: Evidence from nonprofit sport clubs in Germany. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 24(2), 461–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-012-9272-2

- Wicker, P., Breuer, C., Lamprecht, M., & Fischer, A. (2014). Does club size matter: An examination of economies of scale, economies of scope, and organisational problems. Journal of Sport Management, 28(3), 266–280. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2013-0051

- Wicker, P., & Thormann, T. F. (2021). Well-being of sport club members: The role of pro-environmental behavior in sport and clubs’ environmental quality. Sport Management Review. Advance online publication.

- Wicker, P., Vos, S., Scheerder, J., & Breuer, C. (2013). The link between resource problems and interorganisational relationships: A quantitative study of Western European sport clubs. Managing Leisure, 18(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/13606719.2012.742226