ABSTRACT

Purpose

Identify the challenges and opportunities to develop Para-hockey for participants with intellectual disabilities (ID), and to make recommendations about next steps.

Methodology

Interviews with stakeholders known to be engaged in, and advocating for, ID para-hockey classification, representing Pakistan, New Zealand, the UK, Belgium, Portugal, Argentina and Chile.

Findings and practical implications

There is support and commitment for the development of ID Para-hockey. A collaboration plan should be developed by the International Hockey Federation (FIH) to (a) ensure key stakeholders are aware of FIH’s commitment to this endeavour; (b) link with other stakeholders who have an interest in developing ID sport; (c) learn about good practice in other sports, (d) identify a series of steps to progress a developmental plan. We also see evidence for the need to audit current ID Para-hockey activity internationally.

Research Contribution

This is the first study directly addressing the development of ID Para-hockey. ID Para-hockey is at the start of this developmental journey, and little is known about stakeholder perspectives on the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead.

Originality/Value

It is important, at the outset, to be able to identify what capacities for development exist, and then to consider how these may be built upon.

Introduction and context

The World Health Organisation (WHO) states that around 1.3 billion people, or 16% of the world’s population, experience some sort of disability (WHO, Citation2022a), of whom ∼3% (2.5–3.9%) have intellectual disabilities (ID) (Olusanya et al., Citation2020). People with ID represent one of the least active and most compromised minority groups in terms of physical and mental health, and are associated with poor quality of life, economic dependency and multiple, lifelong service needs (Kinnear et al., Citation2018). However, the majority of these outcomes relate not to the primary health condition, but to the life situation, loss of opportunity and stigma attached to this diagnosis (Hatton & Emerson, Citation2015). Engagement in physical activity and sport is increasingly being evidenced as a way of, not just ameliorating health and social disparities, but also as a way of challenging other people’s attitudes towards people with ID and deconstructing the binary of able/disabled (Marcellini, Citation2018).

This growth in engagement in sport spans from grass roots development to the heights of elite, international sports competition, and is supported through a number of organisations. The Special Olympics (SO) is perhaps the most well-known, supporting over five million athletes, in 32 “Olympic-like” sports (Special Olympics, Citationn.d.). However, the SO sits outside of the main para athlete pathway, operating a very inclusive eligibility system, having their own sports rules, and a less elite performance-based philosophy (Burns, Citation2018). Virtus is the International Federation for Para Athletes with Intellectual Impairments and is an International Paralympic Committee (IPC) recognised International Organisations of Sport for the Disabled (IOSD) for athletes with Intellectual Impairments (II)Footnote1(Virtus, Citationn.d.). Virtus is the internationally recognised body responsible for developing high-performance sport for athletes with ID, and holds contracts with the IPC and multiple International Sports Federations (ISFs) to provide the service of confirming the eligibility of athletes to compete in the impairment category “Intellectual Impairment”. Virtus uses a rigorous procedure to evaluate a portfolio of evidence confirming the diagnosis of ID. All ISFs which have ID athletes competing in either Virtus and/or IPC recognised events use this process.

Founded in 1989 the IPC is a non-profit organisation, supporting 210 member nations to promote Para sport, and it delivers the summer and winter Paralympic Games. Increasingly, the IPC has emphasised inclusion as part of its vision, and to support this through the development of Para sport (IPC, Citation2023a).Footnote2 Athletes with ID have had a turbulent history with inclusion in the Paralympics, having been first included in the winter Games in Tignes, in 1992, but then competing in a separate event after the summer Games in Barcelona in 1992, held in Madrid. In Atlanta, in 1996, they were fully integrated into the main summer Games, but only included 56 athletes. In Sydney, 2000 this grew to 244 athletes, but sadly, after the Games, a scandal emerged revealing that a prominent member of the Spanish team, international disability and ID sports organisations, had purposely cheated, fielding basketball players who did not have ID. After a review, the IPC determined the systems of eligibility were not good enough and suspended all ID athletes until improvements in eligibility could be made (Brittain, Citation2016). A rigorous review, revision and programme of research then took place and, on the basis of this, a vote was taken at the IPC General Assembly in 2009 to re-include ID athletes. However, this clearly remained an area of debate with 63 members voting for, 53 against and 7 abstentions (Lantz & Marcellini, Citation2020). Currently, for ID athletes there are three sports included in the summer Games, in one competition class each, Table Tennis, Athletics and Swimming. There is currently no inclusion in the Winter Games (Gilderthorp et al., Citation2018).

Competition for sports to be included within the Winter or Summer Paralympic Games is fierce, and represents the pinnacle of Para sport, attracting national funding, prestige and media coverage (Dowling et al., Citation2018). Whilst attaining this goal is complex, and open to many influences, some parameters are clearly definable, such as building participation across nations and regions, driving up the level of competitive performance, and developing IPC code compliant classification systems (IPC, Citation2023b), in addition to meeting a shared vision of “an inclusive world through Para sport” (IPC, Citation2023a). Some ISFs have embraced the opportunity to include athletes with ID as a way of meeting these objectives; the International Hockey Federation (FIH) being one of a number of ISFs to enter into a Memorandum of Understanding with Virtus to promote their sport.

Building on a firm participation rate of around 30 million players internationally, with 137 National Associations, the FIH is taking steps to increase the breadth of inclusion in the sport and develop pathways from grassroots to elite competition, including the growth of field Para-hockey for players with ID (FIH, Citation2019). Currently, there are 15 national hockey Federations (11% of all national Federations), actively involved in the development of Para-hockey, spread over four continents (European Hockey Federation; International Hockey Federation (FIH), Citation2019) and there is evidence that more countries are beginning to develop ID Para-hockey. According to the Asian Hockey Federation (AHF) and Oceanian Hockey Federation (OHF), Afghanistan, Brunei, Tonga, Vanuatu and Papua New Guinea are now providing some ID Para-hockey activities (Development & Education Manager at OHF, personal communication; CEO at AHF, personal communication). Para field hockey is not currently included in the Paralympic Games. Ice sledge hockey is included in the Winter Games, though limited to those with physical impairment in the lower part of the body. The SO showcases floor hockey, an adapted format, similar to ice hockey, but on a court the size of a basketball court. Crucially, in the 2023 Berlin SO World Games, field hockey was introduced as a demonstration sport, involving 130 players. Within Virtus, field hockey remains a demonstration sport, and is yet to be included in any event schedule.

The question then arises as to how a disability sport, such as hockey, can be supported to access what has been described as a pyramid of performance with a broad participation base, and athlete pathways leading to ever more elite and exclusive tiers (events); with the pinnacle being inclusion in the Paralympic Games (Lantz & Marcellini, Citation2020). The embedded logic in this model being that achieving the pinnacle influences participation, and vice versa, growing the whole sport. One way of supporting this development internationally is integrating the responsibility of disability sport provision into non-disability sports organisations, which is the general direction of flow for most sports, including hockey. However, as described by Kitchen et al (Citation2019), little is known about how this process works and how effective it is. In their study of multiple cases they identified successful capacity building strategies, including funding underpinned by staff commitment, developing networks, attracting volunteers and educating the workforce. Nevertheless, they also found that progress can be undermined by a lack of strategic planning involving relevant stakeholders. Other helpful factors identified have included a willingness to adapt to new situations, also influenced by the organisational financial capacity (Casey et al., Citation2012), and the ability to attach to high status organisation to build integrative capacity (Kitchin & Crossin, Citation2018).

Another theme of this research has been to understand not only what the important elements of capacity are but how they can be built (Kitchin et al., Citation2019). This has led to frameworks such as the Theory Of Sports Policy Factors Leading To International Sporting Success (SPLISS) model (De Bosscher, Citation2015), identifying nine key pillars to success. However, other researchers have pointed to the complexity of these organisational contexts, and the need to consider nuances, such as the type of disability, and the socio-cultural contexts of nations (Patatas et al., Citation2021); not to mention being critical of the current over-reliance on theory transferred from able-bodied contexts (Dehghansai et al., Citation2020). As Marin-Urquiza et al. (Citation2023) have recently demonstrated in a study of the structure and organisation of sport for people with ID across Europe, existing configurations have grown organically, are complex and influenced by local agendas. Other researchers have honed in on specific factors associated with developing sports, including how sports classification systems can influence not only athlete pathways but investment in sports, prioritising performance outcomes in terms of medals as opposed to grass root development (Kitchin et al., Citation2019; Patatas et al., Citation2020).

The development of ID Para-hockey is at the start of this developmental journey and little is known about stakeholder perspectives on the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead. Within the framework of capacity building it is important at the outset to be able to identify what capacities for development exist and then to consider how these may be built upon (Kitchen et al., Citation2019). A valuable starting point is to gain the views of those already experienced in the sport with the impairment group (Ravensberger et al., Citation2016). Hence, the research underpinning this paper was exploratory, using a qualitative, collaborative approach with experienced stakeholders to refine the focus of the required development and research needed to advance ID Para-hockey.

The aims of this study were to identify, in the context of the existing organisational interests, i.e. the services offered by Virtus, the strategic aims of FIH and the activities of those delivering ID Para-hockey, the challenges and opportunities to develop ID Para-hockey, and to make recommendations about next steps.

Methodology

As there is no previous research in this specific area this project can be considered exploratory and so has adopted a constructivist ontology and interpretivist epistemology. Solórzano and Yosso (2002) explain that the gathering of “lived experiences” complements social justice research given the value it places on experiential forms of knowledge (cited in Fletcher et al., Citation2023, p. 5). Taken together, this approach has drawn on the lived experiences and expertise of various international stakeholders involved in ID Para-hockey in order to identify and explore the key challenges they face in further developing and legitimising ID Para-hockey.

Given that the focus of this study was on both conceptualising and operationalising an approach to ID para-hockey development, we have adopted an organisational approach; actively recruiting people involved in hockey at national, international and continental levels. There is a relatively small and highly specialised community of people involved within the area of ID Para-hockey and their inclusion in competitions. As such the approach to sampling adopted therefore, was purposive – that is, actively seeking out people known to be engaged in and advocating for, ID para-hockey classification . Inclusion criteria required participants to either have knowledge about classification research in ID sports and/or hold responsibility for developing ID Para-hockey to include more ID players through to elite level. Once identified, potential participants were contacted, either through gatekeepers who already had a personal connection, or directly by Author A through a combination of email, LinkedIn and Twitter. Once connected, stakeholder organisations were asked to facilitate introductions, via snowballing, to further reach potential participants. We employed these techniques for three reasons: firstly, to empower our participants to shape the research via the inclusion of those voices our interviewees believed should be heard; secondly, to ensure the sample did not simply reflect the research team’s existing professional networks; and thirdly, given the lack of available data on Para-hockey development, snowball sampling was key in enabling us to be sure that we had gathered a meaningful sample of voices.

Due to time pressures and busy schedules not everyone who was approached was able to participate in an interview. Over 20 potential participants were contacted. Of these, 10 agreed to be interviewed. While relatively small, our sample does include representation from a range of stakeholder groups and geographic locations from within the ID para-hockey community. Our sample included researchers, development officers, CEOs and coaches, with some participants holding more than one role within their organisation. Testimonies from participants representing Pakistan, New Zealand, the UK, Belgium, Portugal, Argentina and Chile are referred to in this paper. Given the geographic spread of participants, interviews took place over Microsoft Teams and Zoom. The choice of platform was decided by the participants. As some individuals are easily identifiable, to preserve anonymity, reported individual characteristics have been limited (see ).

Table 1. Study participants, organisations and country of residence.

Ethics approval was provided by Leeds Beckett University. Upon contact, all participants were provided with an information sheet and consent form, which clarified that their participation was voluntary, all responses would remain anonymous and confidential, and they had the right to withdraw, without penalty, up until a stated date. They were also invited to ask questions about the process. Once recruited into the study an appointment was made to participate in an interview carried out virtually. The semi-structured interview guide was developed to facilitate exploration of the participants’ involvement in ID Para-hockey, their knowledge and their views in relation to the aims of the study. The interview moved chronologically from questions about the participant’s views on the current status of ID Para-hockey, aspirations for future development, how eligibility is managed, the need to develop a classification process, and how this might be developed. Questions were tailored to be relevant to the specific role or organisation of the participants and were semi-structured to allow deeper exploration of important topics as they arose. An opportunity was provided for all participants to add any additional information they considered important.

A six-phase model of thematic analysis, as described by Braun et al. (Citation2016), was used to analyse the data. All interviews were transcribed and read through several times by Author A. Initially, we were concerned with identifying all interesting and potentially relevant themes. Next, initial codes were generated through systematically coding the entire dataset and subsequently organising codes into themes. These were reviewed by all authors to ensure they were a good reflection of the larger dataset. Once all data were coded the themes were revisited for coherency, refined and operational definitions developed to describe each theme. In terms of quality assurance attention was paid to the 15-point checklist described in Braun et al. (Citation2016).

This iterative coding process involved all authors, each of whom possesses their own biographies, have different lived experiences and, ultimately, have different relationships with sport, para sport and ID hockey. The first author identifies as a White, Belgian, non-disabled, woman. She was asked by the FIH to undertake this exploratory research. The second author is a European, White non-disabled woman, with research and practice experience of classification and sport development for athletes with ID. The third author identifies as a White, British, non-disabled man. He considers himself an academic activist, who works closely with sports organisations on their inclusivity and accessibility priorities. Finally, the fourth author is a White, Belgian, non-disabled female academic, with research and practice experience of classification and coaching for athletes with ID. It is important to say that the FIH’s primary contribution to this study was through referral. There was no financial exchange and thus, the authors were not influenced or constrained by any kind of organisational imperative.

Findings

Three main themes encapsulated participant responses: 1. the status of ID Para-hockey; 2. eligibility and classification processes and 3. the challenges for the future development of ID Para-hockey. All participants contributed to each theme. Quotations are used to illustrate the content of the theme and attributed to the participants shown in . Each of these themes will now be explored in turn.

The status of ID Para-hockey

This theme concerns observations on the current status of ID Para-hockey, within the wider context of hockey internationally. It was acknowledged that ID Para-hockey was at a developmental, but growing stage, with four nations involved in 2011 and 15 nations by 2020. It was also noted by two of the regional representatives that some countries are already providing opportunities that are yet not officially recognised under the FIH. The extent of these developments was considered highly variable across nations. The Netherlands was identified as possibly the most advanced with Participant B referring to there being 500–600 players with ID already linked to local hockey clubs.

Growth was identified by all as a need. Examples were provided where growth was already occurring. For example, according to Participant F, while in 2018 Argentina had 12 girls with ID playing in Buenos Aires only, by 2022, this figure was closer to 200, and represented girls from across the country. The Portuguese respondent gave a similar example:

There’s an association [ANDDI, which is the National Sport Association for Intellectual Disability in Portugal] who organises sports for all people with disabilities. […]. We have a partnership with ANDDI and then we work with institutions. Now we have 28 institutions playing Para-hockey and we have like 318 players. (Participant D)

[…] last year [2019] I got into Para-hockey […] with a couple of friends and people I know from my club. […] every month, the national federation makes this hockey festival, so we’ve decided to include it [Para-hockey] there to make it more visible. […] We hope that with this massification [spreading of field hockey in Chile], we could include Para-hockey immediately, so it’s not something that you add on later … and you start with hockey and you have Para-hockey with it. Parallel, as important as hockey. (Participant J)

It’s part of the governance review of the IPC that they are encouraging all international sports federations to involve all different impairment groups in sport. So, there is a mandate from the IPC that everybody involved should be doing it.

[…] there are some nations where their government and their funding agents have said: “You need to be inclusive and you really do need to have this as part of your official agenda.” That has happened to a certain extent in Holland and Belgium, in Germany, in England, but on the whole, its volunteers driving the growth of this. […] they [FIH] have a duty to, in my opinion, they’re obliged to, because every sport should be inclusive, fully inclusive. (Participant B)

The big challenge has been that international federations, national federations, continental federations are so busy focusing on major events like the Pro League and the national championships and the continental championships and the income that that generates and the wow factor that that generates. But to get a slice of their time and their resources to develop a new area when a lot of the nations are not well resourced from a staffing level and a finance level [is hard].

We’re trying to get neighbouring countries to work together […] It feels more like you’re doing something inspirational together as friends and partners, rather than the EHF (European Hockey Federation) sending out these documents saying; “have you done this yet?”, putting ticks and numbers in against it. So, it’s that philosophy to bring people together, but you do need active people on the ground that want to do it and those people are unique and they’re individuals. […] And then the key thing for us or FIH is, when we, when that person is highlighted or is someone that you know has got the energy to do it, is then … you throw your full weight and support behind them. And what’s crucial for us is not to miss the opportunity [of a new country wanting to develop Para-hockey]. (Participant C)

We help every country. Like the twinning programme, where countries who are more developed in Para-hockey help other countries […] we are like Holland and Belgium, we are big okay, but we need to get the others big as well. (Participant F)

We usually bring in a Development Officer from Australia and a Development Officer from New Zealand. They share and lead discussions around best practice […] that might be useful in the islands. That provides that connection […] they then have a wider network and we try to twin up Australia with Papua New Guinea, Solomon and Vanuatu, Hockey New Zealand with Tonga, Fiji and Samoa. That’s a closer alignment for each to work together and support the smaller ones. (Participant D)

Eligibility and classification processes

This theme is concerned with the participants’ knowledge and views on the need for, and potential development of, eligibility and classification processes for ID Para-hockey. The existence and role that Virtus plays in establishing the eligibility of ID athletes is known and accepted. Participants did not raise any issues with using this system in relation to the development of ID Para-hockey, aside from the time and financial cost of diagnostic assessments, but generally saw it as a virtue that this process was already established. However, to further develop and legitimise ID Para-hockey, it was recognised that there was a need to develop a classification system.

[…] getting some of our nations to go through national eligibility, which is the first step, but we’ve got to get them through international eligibility which is far more robust and expensive. […] any nation wanting to come to Amsterdam [European Championship] next year and aspire to be in the Championship pool, all have to have done their international eligibility. […] our European Championship will be more recognised by Virtus then as a properly robust run Championship, rather than a type of festival, you know. (Participant B)

[…] eligibility is one element and for Virtus competitions, for sports that are only on the Virtus programme that is enough, just to prove that the athlete has an intellectual impairment, but for IPC competitions that’s not enough [as there also has to be a classification system in place]. (Participant H)

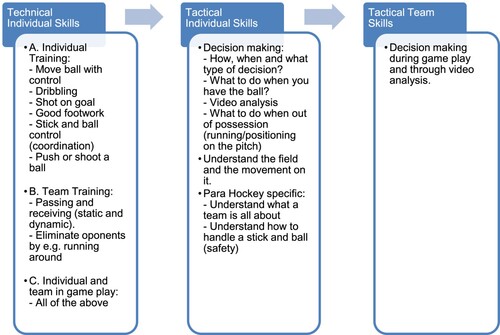

If you think of it as three different tiers, so you have individual technical skills, individual tactical skills and then team tactics. You can’t do team tactics unless you know individual tactics and you can’t do individual tactics unless you can do the technical skills. (Participant C)

One participant (A) went beyond some of the research challenges of developing a classification system and mentioned the need for the translation of the system into operation and some of the wider challenges this brings in terms of, for example, training coaches and classifiers:

And I suppose that one of the other criteria the IPC look at is the qualification training of the classifiers. How is the system going to operate? So, it’s not just, is it a good system?

Challenges and the future development of ID Para-hockey

All the participants had similar views about the challenges facing the development of ID Para-hockey. However, depending upon their role and organisational position the trajectory of development was seen differently.

As the data were collected during the early period of the COVID-19 pandemic all participants commented on the effect this had had on the competition schedule, and how it had slowed development and expansion. For Participant B:

Covid-19 obviously has had a big impact on all of us. Unfortunately, this year, whilst we’ve done reports and we’ve done Skypes and Zooms, but on the ground, work has been extremely difficult for every nation. […] We were hoping to be there by 2022 [with 14 additional nations playing Para-Hockey (ID)], but obviously we’ve lost a year … obviously it’s [development work] all on the back burner. We’ve lost a full year really.

It’s probably because there is no competition going on at the moment. So, because there’s a cost to get everybody through the process people are not going to invest in that unless there are competitions for people to be in.

Because of this, the pandemic you know, I’m worried. Most of my players are in institutions … and some of the cases we have are in that kind of institution. For now, we don’t have any problems for people with disabilities, but some of the institutions have older people and disabled people. They are almost in the same house, the same building. So, I’m a little bit concerned about that. (Participant F)

[…] it [eligibility] can be quite an expensive and notorious process to get all the evidence required for the international eligibility, which stops people more at a national level from competing, right? … We’ve done this on a shoe string, getting a little bit of money here and a little bit of money there, but there has to be some investment in it.

[…] the big problem for all the hockey in Portugal, is money, is sponsors, you know. We want to do more, but we can’t because we don’t have money. Last year they [the government] just, they took out all the money for Para-hockey.

Participants also referred to the lack of basic materials and equipment needed to play the sport, but a few participants cited innovative ways to manage this. For example, in Oceania the development of a “Champions give back” programme where established teams and players donated unrequired equipment, often given by sponsors. In this region they also developed cheaper plastic sticks and balls, which were safer and more encouraging for new players, although they also cited the problems and costs of distributing these resources. In addition to the lack of financial resources, many participants referred to the lack of time and human resources to properly implement ID Para-hockey. Currently, participants referred to relying heavily on a small group of dedicated volunteers:

You have to find someone, if the Federations won’t do it, you have to find someone, and quite often it’s a dedicated parent of a child. […] You have to find someone who’ll say: “I don’t accept that, I’m gonna start it up!”. (Participant B)

Para-hockey I’m doing for free. […] I’m so passionate about that […]. (Participant F)

Expertise – you know there are a few people spread very thinly around this [eligibility and classification process]. Resources in terms of actually getting funding – we’ve done this on a shoe string, getting a little bit of money here and there, but in the future there has to be some investment in it. (Participant A)

They don’t believe they [athletes with an ID] could do this. (Participant I)

I think we have to convince people. Here it’s … any disability it’s not easy to deal with. The country is just starting to change in terms of that. … . We need a mentality change. (Participant J)

The priority in our nations and some of the developing nations and nations from third world are poverty. If the people can have at least two meals a day or if they have a shelter to live or not. (Participant G)

To be taken seriously by the IPC and by Special Olympics really, in terms of full status sport, we’ve got to have 24 nations active across a minimum of 3 continents. (Participant B)

[…] I think the most important reason is just the total number of athletes in the Games that is already, let’s say over the limit of what is acceptable for making the organisation possible. […] Yeah, and then indeed a team sport is always, maybe a bit more difficult than another sport, because when you put a new team sport on the programme, that means that you are putting like a large number of athletes on the programme. […] That’s a bit the disadvantage of bringing in a team sport. (Participant H)

The future development of ID Para-hockey

All participants were clear that two things needed to occur. Firstly, the sport needed to grow and would need help from a range of stakeholders to do so. Secondly, the ID Para-hockey community needed to collaborate by sharing good practice. In terms of growth, some participants had developed specific strategies targeting geographical locations and organisations where hockey is already well established:

[…] by growing the number of nations and staging more successful Para-hockey events we hope to inspire more nations to start Para-hockey ID. […] Asia in particular is key to our growth strategy as hockey is such a major sport across Asia. So, we need to work closely with Asian Hockey Federation and form strong partnerships to encourage growth. (Participants B)

What’s really important for them [nations] to focus on now is the growth within their own countries and having their own systems and leagues and matches and clubs. That’s the fundamental number one thing. […] We say our objective is to grow more people playing Para-hockey … within nations at every level. (Participant C)

So, I think that the important thing we need to do … Have ownership, strong ownership [as the AHF], then it’s more predictable where we are heading to at this moment. (Participant G)

I think initially it’s sharing of what has worked […] so that we’re not reinventing the wheel or making the same errors, it allows us to know what could be the barriers, but also, you know, sort of fast track us on what works really well. (Participant D)

In summary, most participants spoke with quiet optimism about the future of Para-hockey, but were cognisant of the identified barriers. Some participants preferred to focus on the short-term barriers, principally COVID-19 and its impacts. Others reflected on the long-term project ahead. With greater recognition of the steps and complexity involved in developing ID Para-hockey and developing a classification system has come a greater appreciation of the longer timescales and resources required:

Exciting, a challenge, but exciting. If we do get rid of Covid then there’s no reason why we can’t push on and become a stronger part of the hockey family. (Participant B)

We are doing very patient, good work, you know. So, yeah, I think we gonna see more teams in the Europeans for the next year or next years, for sure. (Participant F)

Discussion

This is the first study directly addressing the development of ID Para-hockey and the findings affirm that there are ambitions and strategies in place to grow Para-hockey and to include athletes with ID in that development. Some nations, which already have field hockey as an established sport, are now adding ID Para-hockey initiatives to their existing programmes. Other nations, where field hockey is not already established, are endeavouring to grow ID Para-hockey in unison with the development of mainstream hockey and Para-hockey for other impairment groups. Such initiatives cover the spectrum from grassroots, recreational play, to elite competition, with the pinnacle aspiration being Paralympic inclusion.

In terms of identifying organisational capacities which have been shown to aid the development of Para sport it is useful to reference the nine pillars in the SPLISS framework (De Bosscher, Citation2015; Dowling et al., Citation2018). Pillar one refers to financial support which was identified as a need in this research, and that not being a Para sport reduced access to funding, whilst perhaps paradoxically increased the desire to achieve this status to access resourcing. As both Wong (2013) and Darcy (2018) identify, team sports are additionally expensive and this impacts more on financially poorer, often less-developed nations (cited in Dowse & Fletcher, Citation2018; Richardson & Fletcher, Citation2022). In this study some of the nations involved in grassroot development have lower GDPs, some do not have hockey as non-para sport established, and even some of the richer nations find funding limited, suggesting that financial support for ID Para-hockey is a significant challenge. Pillar two refers to an integrated approach to policy development and it is a strength that the FIH are explicitly targeting ID Para-hockey as a growth area, and are working with both Virtus and the SO to promote participation. However, as Kitchin et al. (Citation2019) point out, without the translation of strategy into planned implementation, sustained development can be compromised.

Pillar three, foundation and participation, is perhaps the biggest current strength in ID Para-hockey as a number of factors previously identified as leading to success exist here. This includes a body of committed volunteers, active participation by athletes, networking and a commitment to share good practice (McLean et al., Citation2021). What was clear in this research, further reflected the findings of Marin-Urquiza et al. (Citation2023), that these “bottom-up” developments, and the ensuing networks, were quite specific to the national contexts; requiring any strategic developments to be cognisant of this (Patatas et al., Citation2021). Pillars four to seven, namely talent identification, athlete career and post-career support, coaching provision and coach development were not strongly represented in the themes, perhaps as developmentally these issues are beyond current development.

Pillars eight, (inter)national competition, and nine, scientific research, were issues which surfaced in the findings. There was an understanding that to promote national and international competition within Virtus there was a need to establish the eligibility of the athletes to compete in the ID category as the first stage of sports classification, but finding the necessary financial resources was seen as challenging. However, this is not unique to Para-hockey, or indeed ID sport, and other researchers have identified the classification process as a constraint (Dehghansai et al., Citation2020). Research was identified as a necessary step, specifically in relation to developing the full classification system. However, the comments made by the participants demonstrated the rich depth of knowledge which is required to develop a classification for this impairment group exists (Van Biesen et al. Citation2020).

There are some limitations to this research, specifically the small number of participants and a likelihood of positive response bias in terms of those who chose to participate. However, the participants do present a comprehensive range of perspectives, organisationally, functionally and geographically. Those who participated were unanimously committed to increasing the inclusion of ID players in Para-hockey, but as experts in their field they were not naïve to the challenges and obstacles in the way, and all had direct experience of working in the area. As such a number of conclusions can be reached from the interviews carried out in this study:

There is a commitment to grow Para-hockey for players with ID, and there is ongoing work across the world to accomplish this aim;

This development is supported by the FIH who see it as a priority;

There is a recognised resource requirement to accomplish this aim, a lack of funding is being supplemented through sharing good practice and the will and commitment of dedicated individual volunteers.

Paralympic inclusion has many challenges and is unlikely in the near future, but to open the potential of this pathway a classification system should be developed for ID Para-hockey and endorsed by the FIH. However, this should not constrain national developments, where such a system is not required.

Conclusion

To further develop ID Para-hockey a number of recommendations can be made from this initial study. This study demonstrated a mixed picture in terms of knowledge and development geographically and across stakeholders. It has been evidenced by the previous research that successful progress results when there is a strategic plan with steps to implementation, and positive collaborations between stakeholders (Dehghansai et al., Citation2020). Hence, it is recommended that a collaboration plan is developed by FIH, to (a) ensure key stakeholders are aware of FIH’s commitment to this endeavour; (b) link with other stakeholders who have an interest in developing ID sport; (c) share good practice from ongoing projects, and learn about good practice in other sports, (d) identify a series of steps to progress a developmental plan. Moreover, as researchers committed to social justice and voice, we would advocate for the involvement of ID Para-athletes (from within and beyond hockey) throughout this development.

A positive start has been made in this direction by the publication of “Hockey4All: Roadmap for Para-hockey (ID)” by the EHF (Citation2019), which demonstrates a strategic commitment in this area. We also see evidence for the need to audit current ID Para-hockey activity internationally so active nations, clubs and groups can be mapped and a network for communication established. Not only will this aid communication, but it will benchmark progress and provide data for funding applications. To increase inclusion, there is a need to further promote ID Para-hockey within both the Special Olympics and Virtus. This in turn will promote the use of the Virtus eligibility system to register ID Para-hockey players both at national and international levels, and increase competition opportunities. Finally, this research has identified the need to establish links with classification researchers, which could be accomplished by working with the Virtus Academy (https://thevirtusacademy.com/) to develop a strategy about resourcing and establishing collaborative partnerships to develop an ID-Para-hockey classification system.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Intellectual Impairment (II) is an umbrella term used by both Virtus and the IPC which reflects the conceptual basis of sports classification. In Paralympic classification the type of impairment is drawn from the taxonomy described by World Health International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (WHO, Citation2001) and is based on the functional ability of the athlete not diagnosis. However, to be eligible for an impairment group there must be an underlying health condition as described by the WHO International Classification of Diseases (ICD) (WHO, Citation2022b) in this case the underlying health condition is Intellectual Disabilities (ID) (Van Biesen et al., Citation2020). In this paper whilst reference is made to both II and ID, depending on the context, for these purposes they are essentially the same group of athletes.

2 The “ownership” and use of the terms “para” in relation to sport is a contested one, with para sport often used as a generic term, whilst the IPC asserts rights over the use of the word “Para” and associated terms (see IPC guide to Para and IPC terminology (2021)). In this paper we have adopted the IPC use of the word Para meaning that the International Federation for Hockey is recognised by the IPC as adhering to specified standards of competition.

References

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Weate, P. (2016). Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In Brett Smith & Andrew Sparkes (Eds.), Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise (pp. 213–227). Routledge.

- Brittain, I. (2016). The Paralympic games explained. Routledge.

- Burns, J. (2018). Intellectual disability, special Olympics and Parasport. In I. Brittain & A. Beacom (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of Paralympic studies (pp. 417–437). Palgrave.

- Casey, M. M., Payne, W. R., & Eime, R. M. (2012). Organisational readiness and capacity building strategies of sporting organisations to promote health. Sport Management Review, 15(1), 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2011.01.001

- De Bosscher, V. (2015). Theory of sports policy factors leading to international sporting success (SPLISS). In G. B. Cunningham, J. S. Fink, & D. Alison (Eds.), Routledge handbook of theory in sport management (pp. 93–109).

- Dehghansai, N., Lemez, S., Wattie, N., Pinder, R. A., & Baker, J. (2020). Understanding the development of elite parasport athletes using a constraint-led approach: Considerations for coaches and practitioners. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 502981. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.502981

- Dowling, M., Legg, D., & Brown, P. (2018). Comparative sport policy analysis and Paralympic sport. In I. Brittain & A. Beacom (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of Paralympic studies (pp. 249–272). Palgrave.

- Dowse, S., & Fletcher, T. (2018). Sports mega-events, the non-West and the ethics of event hosting. Sport in Society, 21(5), 745–761. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2018.1401359

- European Hockey Federation (EHF) & International Hockey Federation (FIH). (2019). Active and target Para-hockey nations. Unpublished manuscript.

- FIH. (2019). Rules of Para-hockey for Athletes with an Intellectual Disability (ID) including explanations. The International Hockey Federation: http://www.fih.ch/inside-fih/our-official-documents/rules-of-hockey/.

- Fletcher, T., Dashper, K., & Albert, B. (2023). Whiteness as credential: Exploring the lived experiences of ethnically diverse UK event professionals through the theory of racialised organisations. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(11), 3903–3921.

- Gilderthorp, R., Burns, J., & Jones, F. (2018). Classification and intellectual disabilities: An investigation of the factors that predict the performance of athletes with intellectual disability. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 12(3), 285–301. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.2017-0018

- Hatton, C., & Emerson, E. (2015). Introduction: Health disparities, health inequity, and people with intellectual disabilities. In Chris Hatton & Eric Emerson (Eds.), International review of research in developmental disabilities (Vol. 48, pp. 1–9). Academic Press.

- IPC. (2023a). Strategic Plan: 2023-2026. Retrieved August 23, 2023, from https://www.paralympic.org/publications

- IPC. (2023b). Draft IPC Classification Code (version 2023). Retrieved August 23, 2023, from https://www.paralympic.org/classification-code-review

- Kinnear, D., Morrison, J., Allan, L., Henderson, A., Smiley, E., & Cooper, S. (2018). Prevalence of physical conditions and multimorbidity in a cohort of adults with intellectual disabilities with and without down syndrome: Cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 8(2), e018292. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018292

- Kitchin, P. J., & Crossin, A. (2018). Understanding which dimensions of organisational capacity support the vertical integration of disability football clubs. Managing Sport and Leisure, 23(1-2), 28–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2018.1481764

- Kitchin, P. J., Peile, C., & Lowther, J. (2019). Mobilizing capacity to achieve the mainstreaming of disability sport. Managing Sport and Leisure, 24(6), 424–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2019.1684839

- Lantz, E., & Marcellini, A. (2020). Sports games for people with intellectual disabilities. Institutional analysis of an unusual international configuration. Being disabled, becoming a champion (pp. 49–62). Routledge.

- Marcellini, A. (2018). The extraordinary development of sport for people with dis/abilities. What does it all mean? Alter, 12(2), 94–104.

- Marin-Urquiza, A., Burns, J., Morgulec-Adamowicz, N., & Van Biesen, D. (2023). Structure and organization of sport for people with intellectual disabilities across Europe. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 1(aop), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.2022-0212

- McLean, S., Read, G. J., Ramsay, K., Hogarth, L., & Kean, B. (2021). Designing success: Applying cognitive work analysis to optimise a Para sport system. Applied Ergonomics, 93, 103369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2021.103369

- Olusanya, B. O., Wright, S. M., Nair, M., Boo, N., Halpern, R., Kuper, H., Abubakar, A. A., Almasri, N. A., Arabloo, J., & Arora, N. K. (2020). Global burden of childhood epilepsy, intellectual disability, and sensory impairments. Pediatrics, 146(1).

- Patatas, J., De Bosscher, V., De Cocq, S., Jacobs, S., & Legg, D. (2021). Towards a system theoretical understanding of the Parasport context. Journal of Global Sport Management, 6(1), 87–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/24704067.2019.1604078

- Patatas, J. M., De Bosscher, V., Derom, I., & De Rycke, J. (2020). Managing Parasport: An investigation of sport policy factors and stakeholders influencing para-athletes’ career pathways. Sport Management Review, 23(5), 937–951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2019.12.004

- Ravensbergen, H. J., Mann, D. L., & Kamper, S. J. (2016). Expert consensus statement to guide the evidence-based classification of Paralympic athletes with vision impairment: a Delphi study. British journal of sports medicine, 50(7), 386–391. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095434

- Richardson, K., & Fletcher, T. (2022). Blind football and sporting capital: Managing participation among youth blind football players in Zimbabwe. European Sport Management Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2022.2127827

- Special Olympics. (n.d.). What we do. Retrieved August 22, 2023, from https://www.specialolympics.org/what-we-do?locale=en

- Van Biesen, D., Burns, J., Mactavish, J. J., Van de Vliet, P., & Vanlandewijck, Y. C. (2020). Conceptual model of sport-specific classification for Para-athletes with intellectual impairment. Journal of Sports Sciences, 39(sup1), 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2021.1881280

- Virtus. (n.d.). About us. Retrieved August 22, 2023, from https://www.virtus.sport/about-virtus

- World Health Organisation. (2001). International classification of functioning, disability, and health: ICF. WHO.

- World Health Organisation. (2022a). Disability. Retrieved August 23, 2023, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health

- World Health Organisation. (2022b). ICD-11: International classification of diseases (11th revision). WHO.