ABSTRACT

Purpose/Rationale

Stakeholders of sporting organisations have expressed a myriad of concerns regarding sport organisations’ accountability. Despite growth in the literature, a review and examination of this scholarship remains missing. This paper provides a scoping review on the accountability of sport organisations, and in doing so, map the research field and determine future research opportunities.

Design/Methodology/Approach

Based on the scoping review guidelines of Arksey and O'Malley (Citation2005), four databases were comprehensively searched. Following a thorough search process, 44 articles relating to sporting organisation accountability were reviewed.

Findings

Our analysis reveals a dominance of conceptual and theoretical-based studies with a varied approach to accountability, and evidently a pre-eminence of case study methodologies and lack of explicit theoretical perspectives. International sport organisations, national sport organisations, and government agencies were among the most studied.

Practical implications

Future studies should pursue an integration of discourses, and greater generalisability among organisations. This has the potential to strengthen the theoretical perspectives and guide research that improves accountability practices of sport organisations.

Research contribution

We have mapped the sport organisation accountability literature, as well as identifying research gaps to direct future research. Overall, the results reveal sport organisations’ accountability is a nascent topic with unrealised interdisciplinary potential.

1. Introduction

Major scandals in the twenty-first century have raised a myriad of concerns among sport organisation stakeholders. Unethical and sometimes illegal practices including corruption (Jennings, Citation2011), fraud (Kihl et al., Citation2021), bribery (Philippou, Citation2022), and athlete abuse (Willson et al., Citation2022) are seemingly omnipresent. These issues are widely reported in the media and occur in many countries across multiple sports and sport organisations (Geeraert, Citation2019; Pielke, Citation2013). Accountability is often regarded as a panacea of all these ills and difficulties (Ebrahim, Citation2003; O’Dwyer & Unerman, Citation2008; Williams & Taylor, Citation2013). With adverse publicity and growing public accountability expectations (Busuioc & Lodge, Citation2017; Lefebvre et al., Citation2024; Slack & Shrives, Citation2008; Tweedie, Citation2016), axiomatically the public ask for accountability (Morgan & Wilk, Citation2021). Important questions are raised regarding the nature of sport organisations’ accountability for who and for what. Principal amongst these concerns is the perception that problems are fundamentally rooted in a lack of accountability (Han, Citation2020; Nelson & Cottrell, Citation2016; Pielke, Citation2013).

Despite the almost ubiquitous calls for more accountability in sport organisations, there exist problematic variations in defining, framing, and conceptualising accountability both in sport organisations, and of sport organisations. This may be somewhat unsurprising given the ever-changing, or “chameleon-like”, nature of the accountability concept (Sinclair, Citation1995, p. 231). The social construction of accountability results in an obfuscated and ambiguous meaning (Dubnick, Citation2005; Newman, Citation2004; Williams & Taylor, Citation2013) challenging the navigation of effective accountability studies (Pilon & Brouard, Citation2023). Accountability practices are often contested and conflicting (Lee, Citation2022; Messner, Citation2009; Rana et al., Citation2021), hence research examining accountability practices, mechanisms, and frameworks to complement sport organisations remains fragmented.

With increasing attention and pressures for organisations to be held accountable (Carman, Citation2010; Meenaghan, Citation2013; Morrow, Citation2013), a review of studies examining the accountability of sport organisations is timely to take inventory of the knowledge and guide researchers towards addressing the unethical concerns and practices that are becoming more apparent in sport. Therefore, this paper undertakes a scoping review of research investigating sport organisations’ accountability to provide a stocktake of the key issues and opportunities relating to sport organisations’ accountability and based on our findings, determine future research opportunities. In doing so, we employ the five-stage scoping review protocol outlined by Arksey and O'Malley (Citation2005) to determine:

What characterises the literature investigating organisational accountability in sport?

What do we know regarding sport organisation accountability and how accountability in sport is understood?

What future directions are there for sport organisation accountability research?

A scoping review is well suited to reviewing prior literature on accountability and sporting organisations because this approach offers a wide-ranging and transparent method of mapping a research field (Pham et al., Citation2014) and the opportunity to yield insight into emerging topics (Dowling et al., Citation2018). Scoping reviews are increasingly prevalent in the sport management literature (Baxter et al., Citation2021; Inoue et al., Citation2015; Robertson et al., Citation2021; Shaw & Cunningham, Citation2021; Stegmann et al., Citation2021) and sport governance literature (Dowling et al., Citation2018). These reviews reveal a recent increase in sport governance research and initial attempts to conceptualise sport governance literature, and related concepts, in its entirety. However, we note that previous reviews of the sport governance literature have not adequately addressed the concept of accountability and the wider “accountability and sport” literature. For example, the governance in sport scoping review by Dowling et al. (Citation2018) only mentions accountability twice in the text, and identified only seven articles related to accountability. A surprise finding given accountability is a mainstream concept in accounting and other literature reviews (e.g. Agostino et al., Citation2022; Aleksovska et al., Citation2019; Parker, Citation2011; Williams & Taylor, Citation2013).

There is a rising interest in understanding accounting related practices (Cooper & Johnston, Citation2012) and accountability, along with regulation and commercialisation, are key themes at the nexus between business and sport (Andon & Free, Citation2019). In recent sport governance reviews (Thompson et al., Citation2023) accountability was the most cited governance principle, consequently highlighting future studies should begin with accountability, transparency, and democracy to address non-profit organisation problems. The principles need to be robust and defined for researchers wishing to advance governance (Thompson et al., Citation2023). Yet, the widely used governance principle of accountability has not been reviewed, let alone examined further. Accountability – and its related concepts of transparency, liability, controllability, responsibility, and responsiveness (Koppell, Citation2005) – warrants consideration as a stand-alone concept, and not lost in the all-encompassing governance reviews (e.g. Dowling et al., Citation2018). Governance research in sport is often inspired by corporate governance best practices, but these are not always suited to sport organisations where an imposing universal prescription of sport governance is neither appropriate nor effective, and accountability demands extend across organisational hierarchies (Chappelet & Mrkonjic, Citation2019; Tweedie, Citation2016).

This study makes several contributions to the literature on sport organisations’ accountability. First, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first scoping review examining accountability practices, mechanisms, and frameworks of sport organisations. The wide-ranging and transparent nature of the scoping review approach will enable researchers to better understand a range of issues associated with organisational accountability in sports. Second, the study provides enhanced conceptual clarity regarding accountability in the context of sports organisations to locate mechanisms that improve accountability, that in practice have appeared largely ineffective. Third, this review identifies emergent themes, research gaps, and a research agenda, that inspires researchers and increases the visibility of accountability issues; enticing scholars to embed themselves in pressing, topical, and timely studies.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The next section provides a brief overview of the accountability concept and describes the approach to framing accountability in the present paper. The third section provides the research approach (i.e. methodology). Then we present the findings and analyses of key thematic issues arising from the review. Section five discusses the implications of our findings and proposes avenues for future research, followed by our conclusion in section six.

2. Notions of accountability

Accountability is an omnipresent concept throughout organisations and society. However, agreement on the precise meaning of accountability remains elusive (Dubnick, Citation2005). Definitional ambiguities exist because accountability has numerous dimensions that are both context dependent and context defined (see, for example: Rana et al., Citation2021).

We situate accountability within the broader concept of governance (Dowling et al., Citation2018; Tacon et al., Citation2017). Whilst we agree that accountability intersects with and is a cornerstone of governance, (Geeraert et al., Citation2014), accounting and accountability mechanisms shift how sport is governed (Siddiqui et al., Citation2019). Accountability is even considered a fundamental element for organisations in all societies to act with regard to the consequences imposed by others (Hall et al., Citation2017). Thereby accountability is considered a relational concept between external constituents and the organisation that impact priorities, pressures, decision making, and influence what is deemed legitimate (Andon & Free, Citation2019), while governance is a broad concept capturing managerial, systemic, and political processes (Dowling et al., Citation2018).

A commonly accepted premise of organisation accountability is the principal-agent relationship. Accountability imposes the obligation of the agent to report back to their principal(s) (Bovens, Schillemans, & Goodin, Citation2014; Shaoul et al., Citation2012). The obligation is also referred to as the agent’s responsibility to undertake actions and to account for their actions (Deegan, Citation2009; Gray et al., Citation1996). These accounts assert that individual and collective actions, resource allocation, and results were appropriate and/or successful. Accountability enables an organisation to demonstrate that resources are used for their intended purpose(s) and the appropriateness of resource-allocation decisions (Dubnick & Frederickson, Citation2014). Thus, accountability encourages appropriate (Bovens, Citation2007) and ethical behaviours (Governance Institute, Ethics Index, Citation2021, Citation2021), leading to enhanced confidence, trust, and support from stakeholders (Dubnick, Citation2005).

Etymologically, accountability is associated with accounting and the provision of financial reports (Bovens, Citation2007). The provision of funds creates a legitimate and formal right to demand an account (Lloyd, Citation2005). Owners and funders are keenly interested in financial information and reporting (Edwards & Hulme, Citation1996). There are a variety of organisational accountability mechanisms that provide for information sharing, taking account, and imposing sanctions on an organisation, with the annual report being the traditional communication medium for discharging financial accountability to the dominant stakeholder group (i.e. shareholders) (Arunachalam & McLachlan, Citation2015). Other mechanisms include regulations, reporting, disclosures and audits (Brennan & Solomon, Citation2008).

Financial accountability is commonly associated with the concepts of transparency (i.e. being open with information) (e.g. Ortega-Rodríguez et al., Citation2020; Williams & Taylor, Citation2013), and disclosure (i.e. providing information to align the organisation and stakeholder interests) (e.g. Coy & Dixon, Citation2004; El-Halaby & Hussainey, Citation2015; Greiling & Spraul, Citation2010). Financial accountability obligations are legally mandated and formalised via nuanced and evolving accounting standards (e.g. International Financial Reporting Standards). However, the dominant focus on financial accountability may be unsuited in some sectors (De Villiers & Hsiao, Citation2017; Van Staden & Heslop, Citation2009).

Accountability is thus seen to be an “ever expanding concept” (Mulgan, Citation2000, p. 556) that has transitioned from a shareholder-centric approach towards a more complex, stakeholder-orientated concept (Brennan & Solomon, Citation2008). Stakeholders are “any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievements of the organisation’s objectives” (Freeman, Citation1984, p. 46). Increasingly, they are concerned with the environmental, social, and ethical dimensions of organisations (Hackston & Milne, Citation1996). Hence, accountability is increasingly more than financial accountability (Gray et al., Citation1996; Van Staden & Heslop, Citation2009) and is concerned with being held to account to all stakeholders (Waddock et al., Citation2017), for wider objectives of provision of goods, services, or other resources for communal social benefit (Van Staden & Heslop, Citation2009). A variety of accountability conceptualisations are possible. These include bureaucratic, professional, political, managerial, or market (Burke, Citation2005), strategic, fiduciary, financial, or procedural (Dhanani & Connolly, Citation2012), or business, transparency, responsibility, or regulatory (Mahmood & Uddin, Citation2021).

In the sport sector, there is the dichotomy of on-field success and off-field financial performance (Perechuda & Čater, Citation2021; Terrien et al., Citation2017). Secondly, there is uncertainty of outcome and difficulties of ensuring constant quality (Stewart & Smith, Citation1999). Third, there is the complexity of the sport ecosystem within which sport organisations are embedded, replete with divergent stakeholders and their divergent objectives (Buser et al., Citation2022). Fourth, many sport organisations are nonprofit, lacking identifiable ownership and profit motives (Van Staden & Heslop, Citation2009), creating multiple accountabilities and ambiguities regarding who/what these organisations are accountable to and accountable for (Ferkins & Shilbury, Citation2015). For profit sport organisations have their own accountability challenges, caught between the pursuit of profit and sport success. Additionally, sport provides high levels of partisan and loyalty, high levels of stakeholder engagement and activism, enduring connections with geographical communities, and strong emotional attachment (Baxter et al., Citation2019b), which may be difficult to capture via financial reporting alone.

Based on the sport context and notions of accountability above, our scoping review of studies examining accountability in sports organisations is guided by a broad and expansive conceptualisation of accountability. In this paper, accountability is taken to mean “the duty to provide an account (by no means necessarily a financial account) or reckoning of those actions for which one is held responsible” (Gray et al., Citation1996, p. 38). The following section describes the scoping review methods used in this study.

3. Methods

3.1. Scoping review approach

Scoping reviews examine the nature, extent, and range of research activity to map key concepts underpinning a research area and deciding if a subsequent systematic review is necessary. This is achieved by summarising previous research, drawing conclusions, and identifying research gaps. For the purposes of this study, a scoping review is defined as a type of research synthesis that aims to “map the literature on a particular topic or research area and provide an opportunity to identify key concepts; gaps in the research; and types and sources of evidence to inform practice, policymaking, and research” (Daudt et al., Citation2013, p. 8).

Our scoping review follows the approach outlined by Arksey and O'Malley (Citation2005), which is the most common method used in scoping reviews (Pham et al., Citation2014). The method is a framework to achieve transparency and reproducibility including the stages of identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, establishing study selection criteria, charting, and sorting data, and reporting. The following subsections describe the method and protocol of the review based on the stages of determining data sources and search strategy, managing citations and study selection, charting the data, then collating, summarising, and reporting results.

3.2. Data sources and search strategy

To ensure a comprehensive coverage of the accounting, sport management, public administration, and other relevant disciplines, four databases were searched: ABI/Inform, ScienceDirect, Scopus, and SportDiscus. Two of the databases contain most of the highly ranked accounting journals, while the other two databases contain most of the highly ranked sport journals. The initial search was conducted in June 2021 and a follow-up search of the four bibliographic databases was conducted in December 2023 to identify any additional studies published after the initial search.

Many sport-management-focused scoping reviews use “sport” as a search term (e.g. Baxter et al., Citation2021; Dowling et al., Citation2018; Roberts et al., Citation2020; Schulenkorf et al., Citation2016; Thomson et al., Citation2019; Walzel et al., Citation2018). To capture the variety of sports, and determine which sports researchers are investigating, the search terms employed in this study were “sport” and “accountability”. This combination of terms was searched for amongst the title, keywords, and abstract of published papers in three databases (ScienceDirect, Scopus, and SportDiscus) and anywhere in the article, except full text, in one database (ABI/Inform). Grey literature was excluded using the electronic database limiters. The full-text search strategy was not delimited to dates. Non-English studies were translated to English with an electronic translator.

3.3. Citation management and study selection

After an initial search, all citations were imported into Microsoft Excel. Here duplicate and remaining non-peer-reviewed articles were removed. Citations were then imported into Covidence, a web-based tool that facilitated relevance screening of title, abstract and full article, as well as data characterisation each article. Covidence provided a transparent means of screening articles for eligibility by multiple reviewers.

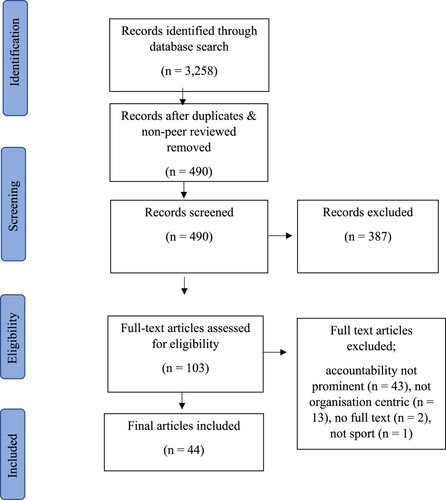

The process of developing inclusion and exclusion criteria was Iterative. The criteria were piloted many times to create a broad, yet consistent and common understanding across the review of constituting organisation accountability. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guided the presentation of the screening and eligibility process. A preparatory database search generated 3258 articles. The exclusion of both non-peer reviewed and grey literature reduced the number of articles. These articles were further screened to remove duplicates and non-English articles. After this process, 490 articles remained.

Titles and abstracts of the 490 articles were then reviewed. Given the widespread use of the word accountability in journal articles, we excluded studies without a focus on accountability, thus emulating the approach of Grossi et al. (Citation2019). Additionally, the focus of accountability was validated with a full-text frequency count of accountability and key-word-in-context for each article. All retained articles used the word accountability at least 10 times. Five studies used the word accountability more than 100 times – Tacon et al. (Citation2017) (n = 190), Torchia et al. (Citation2023) (n = 118), Nelson and Cottrell (Citation2016) (n = 113), Parent (Citation2016) (n = 109), and Millar et al. (Citation2023) (n = 101).

Further, only studies focused on organisational accountability, rather than individual accountability (e.g. athletes, coaches), were retained. Hence, articles were excluded if they focussed on athlete performance, athlete’s health disorders, physical education, nutrition, psychology, coaching or training, or other non-sport or non-management focus. The full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria is summarised in .

Table 1. Scoping review: inclusion and exclusion criteria.

This part of the study selection process resulted in the exclusion of 361 articles and the retention of 104 articles.

The lead author then reviewed the full text of all 104 remaining articles with consultation from another team member on abstruse articles. Following our thorough search process (see ), a final total of 44 studies as listed in Appendix 1, broadly consistent with other reviews (Schulenkorf et al., Citation2022), were retained for detailed analysis.

3.4. Charting the data

Data extraction and synthesising key information from the 44 articles involved collecting standard information. The following information was extracted: publication year and authors, academic field, study location, study type (e.g. qualitative, quantitative, theoretical, or conceptual) and data collection (e.g. questionnaires, interviews, annual reports), study population (e.g. national sport organisations, clubs), sport type (e.g. football, basketball), study context issue, and theoretical perspective.

3.5. Collating, summarising, and reporting results

Consistent with previous sport management scoping reviews (Dowling et al., Citation2020; Dowling et al., Citation2018; Inoue et al., Citation2015), a frequency and thematic analysis was conducted on the data. The method of frequency analysis shows the number of occurrences for each variable (Dowling et al., Citation2018) to provide a numeric summary of the nature, extent, and distributions of the studies reviewed. Thematic analysis classifies reviewed studies into common themes based on the proposed research questions, and then presents in a narrative form. In this study, themes were derived through an inductive and iterative open-coding process (Dowling et al., Citation2018), deliberately avoiding pre-existing themes within sport management literature as these would have limited the scope of the findings. An initial set of themes were derived from reviewing all 44 studies. Next, representative studies of each theme were checked (Inoue et al., Citation2015). Subsequently, all studies were reviewed for the existence of each theme. Themes were then amended and refined accordingly and repeatedly compared with all 44 studies. For example, the contextual justification theme identified in Bekker and Posbergh (Citation2022) was amended to “human rights” with the comparison to Cooper (Citation2023). Final themes were discussed and agreed among the authors. The next section presents the findings of the 44 studies analysed.

4. Findings

4.1. Descriptive analysis

This section provides the frequency analysis results based on year, author, academic field, journal, location, research study type, organisation type, sport type, and theoretical contribution.

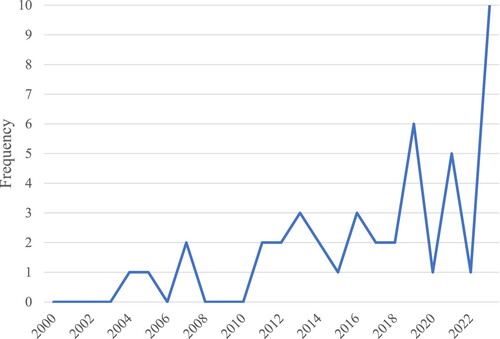

4.1.1. Publication year

An analysis of articles published over time revealed a gradual increase in the number of articles of organisation accountability in sport (see ). Since 2011, there has been at least one article published in each year with six articles published in 2019 and ten articles published in 2023.

4.1.2. Author frequency

Authorship of sport organisation accountability research is not concentrated. The most published authors are Milena Parent (n = 5), Michael Sam (n = 4), Michael Naraine (n = 3), Barrie Houlihan (n = 2), Russell Hoye (n = 2), and Geoffrey Kohe (n = 2), with 78 other (co-)authors.

4.1.3. Academic field

Articles were categorised according to Australian Business Dean Council (ABDC) disciplines. The 44 articles were published in marketing/tourism/logistics (n = 19), accounting (n = 9), management (n = 3), and other (n = 2). Eleven articles were published in journals outside of the ABDC list. The concentration of articles in non-accounting disciplines shows an interest in accountability beyond the accounting discipline.

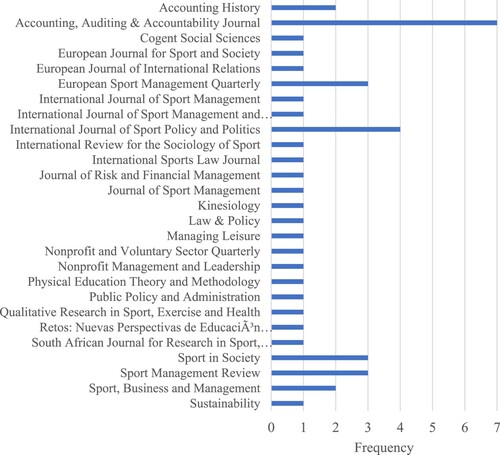

4.1.4. Journals

Six journals have published more than one sport-organisation accountability article. These were Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal (n = 6), European Sport Management Quarterly (n = 3), International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics (n = 4), Sport in Society (n = 3), and Sport Management Review (n = 3), and Accounting History (n = 2). Given the two accounting journals identified here had special issues devoted to issues of sport, sport management journals are more likely to feature sport-organisation accountability studies. Refer to Figure A1 of the Appendix 2 for more details.

4.1.5. Study location

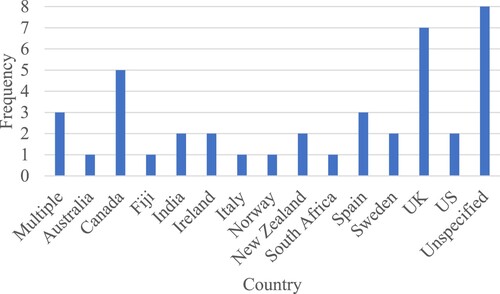

The study locations examined were diverse. Research was conducted on sport organisations from 12 different countries. The United Kingdom (n = 7) and Canada (n = 4) were the most frequent. There were 17 other articles spread across 10 other country locations, and three articles with multiple countries. The Canadian and New Zealand studies are predominantly authored by Milena Parent and Michael Sam respectively. Ten articles did not explicitly state a country as these were largely theoretical or conceptual studies. Refer to Figure A2 of the Appendix 2 for the frequency and range of all study locations.

4.1.6. Study type

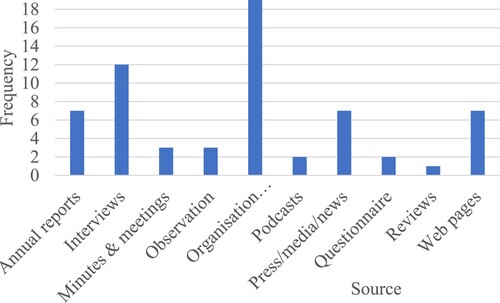

Twelve articles were theoretical or conceptual in nature, including review articles introducing journal special issues identifying accountability themes in the content (Andon & Free, Citation2019; Hyndman et al., Citation2023). The remaining 32 articles (73%) used some form of empirical data. Only five articles used a quantitative methodology exclusively and three articles used a quantitative and qualitative methodology. The high number of articles that used a qualitative methodology (n = 27) reflects the popularity of case studies. Diverse primary and secondary data sources were utilised for the qualitative designs, most commonly using the following: organisation documents (other than annual reports) (n = 19), interviews (n = 12), press/media/news (n = 7), web pages (n = 7), and annual reports (n = 7). All study sources are listed in Figure A3 of the Appendix 2.

4.1.7. Organisation type

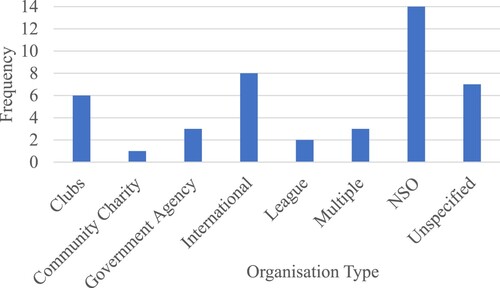

Five articles examined a single international governing organisation including the International Olympic Committee (IOC) (n = 2), the Youth Olympic Games Organising Committee (n = 1), Federation Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) (n = 1), and International Association of Athletic Federations (n = 1). Four articles examined the IOC and another organisation: IOC and FIFA (Henne, Citation2015), IOC and World Athletics (Bekker & Posbergh, Citation2022), the IOC, Commonwealth, and Pan American Games (Parent, Citation2016), the IOC, provincial, municipal, and federal government (Parent et al., Citation2011). One article examined the interrelationships between international and national organisations (Siddiqui et al., Citation2019). The most studied organisations were national sport governing organisations (n = 13). Other articles included clubs (n = 5), government agencies (n = 3), leagues (n = 2), and community charities (n = 1). Refer to Figure A4 of the Appendix 2 for the list of all organisations.

4.1.8. Sport type

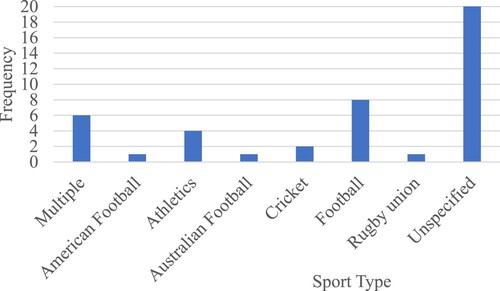

Fifteen articles studied single sports and six articles studied multiple sports, with the IOC and football appearing heavily in the multiple sports. The articles studying single sports were football (n = 6), athletics (n = 4), cricket (n = 2), and the cognate rugby and football sports (i.e. rugby union (n = 1), American football (n = 1), and Australian football (n = 1)). Twenty articles did not explicitly state the sport. Refer to Figure A5 of the Appendix 2 for sport type frequencies.

4.1.9. Theoretical perspectives

The 44 articles utilised 14 theoretical perspectives. The most frequently cited theories were principal agency theory (n = 5), institutional theory (n = 5), institutional logics (n = 6), stakeholder theory (n = 2). To avoid conflict, principal agency theory asserts that a principal has a contractual power to align an agent’s goals and interests to that of the principal and (Halabi, Citation2021) uphold an agent’s behavioual standards. To better understand accountability tensions within the context of sport, an institutional logics perspective is pertinent. Logics refer to “socially constructed, historical patterns of material practices, assumptions, values, beliefs and rules by which individuals produce and reproduce their material subsistence, organise time and space, and provide meaning to their social reality” (Thornton & Ocasio, Citation1999, p. 804). While organisations must respond to the expectations of different institutional logics representing these prevailing belief systems, few studies examined how organisations are held accountable to the norms and pressures associated with different institutional logics. Ten other terms were used by authors as their theoretical perspective. There were no explicit statements of theory in the 24 remaining articles. Refer to for a broad categorisation of theoretical perspectives.

Table 2. Theoretical perspectives explicitly referred to within sport organisation articles.

4.2. Thematic findings

The thematic analysis coalesced around five emergent themes: evolution of accountability research (trends), conceptual justification, accountability definitions, related concepts, and government policy. These themes are discussed in more detail below.

4.2.1. Evolution of sport accountability research

For purposes of this section, evolution of sport accountability research refers to the overall trends in studies of sport and organisational accountability. While diffuse, these articles may be thought of as growing in three broad phases. The early accountability articles in the field of sport management addressed divergent topics whilst each using a single type of data collection (Burger & Goslin, Citation2005; Edwards et al., Citation2004; Havaris & Danylchuk, Citation2007; Houlihan & Preece, Citation2007). The second phase of accountability studies in sport management used more eclectic data collections with more pre-eminence of performance and governance concepts (Chappelet, Citation2011; Geeraert et al., Citation2014; Nelson & Cottrell, Citation2016; Parent, Citation2016; Pielke, Citation2013; Sam & Macris, Citation2014). In the third phase, sport organisation accountability studies began appearing in accounting journals (Baxter et al., Citation2019a; Clune et al., Citation2019; Halabi, Citation2021; Hyndman et al., Citation2023; Millar et al., Citation2023; Rika et al., Citation2016; Siddiqui et al., Citation2019; Torchia et al., Citation2023; Urdaneta et al., Citation2021), continued to feature transparency, governance, and performance topics, with more studies featuring disclosure (Clune et al., Citation2019) and legitimacy (Baxter et al., Citation2019a; Stenling & Sam, Citation2020). Quantitative methods began being used (Muñoz et al., Citation2023; Raiola et al., Citation2023; Svensson & Naraine, Citation2023).

Interestingly, studies published in accounting journals (ABDC code: 1501) and sports management journals (ABDC codes: 1504-1507) showed little evidence of interdisciplinarity insofar as they tended to cite studies from only within their own disciplines. For example, the only accounting study to cite key papers published from sport management journals (Morrow, Citation2013; Pielke, Citation2013) is Urdaneta et al. (Citation2021). Likewise, studies in the sport management journals (Nelson & Cottrell, Citation2016; Parent et al., Citation2021; Parent et al., Citation2018; Sam & Ronglan, Citation2018; Stenling & Sam, Citation2020) cite others within sport management journals (e.g. Chappelet, Citation2011; Geeraert et al., Citation2014; Pielke, Citation2013; Sam & Macris, Citation2014), but do not cite any articles published in accounting journals. The belated accounting research in sport accountability, lack of research outside of marketing and accounting indicated above, and apparent lack of interdisciplinary research among some disciplines limits the exchange and cross-pollination of ideas.

4.2.2. Contextual justification

The contextual justification for each study was identified. Scandals (incorporating match fixing, laundering, corruption, or antidoping) were the most common accountability issue (n = 9) in sport management journals, with human rights, ethics, and integrity (Bekker & Posbergh, Citation2022; Cooper, Citation2023; Kihl, Citation2022; Morales & Schubert, Citation2022) increasing as study contexts. In the context of scandals, studies examined whether organisations, especially international organisations, can be held accountable. Within these studies, accountability is considered as the means to improve internal processes of management and governing boards. Findings showed a limited ability to hold sport organisations to account (Bekker & Posbergh, Citation2022; Chappelet, Citation2011; Geeraert et al., Citation2014; Nelson & Cottrell, Citation2016; Pielke, Citation2013; Renfree & Kohe, Citation2019). Difficulties in holding international organisations to account, on political or economic accountability (Cooper, Citation2023), continues to provide a fruitful topic area of accountability discussion.

Other justifications to examine sport included positive outcomes (i.e. sport value, popularity, health, economics, identity, cultural, or uniqueness) or tensions arising from emotions and passion, participation, and elite performance, economic and social, development of amateur to professional, and commercialisation. These situations provide the appropriate opportunity to examine the tensions between government policy and organisation performance.

4.2.3. Accountability definitions

Most of the studies (n = 18) provided no accountability definition, a finding that is consistent with social enterprise accountability research (Burga & Rezania, Citation2015). The accountability definitions and literature sources provided in 14 articles are summarised in , while Parent (Citation2016) provides definitions from interviewed stakeholders. Sport management journals published 10 articles that provided a definition. Interestingly, defining accountability was one of the few places where sports management scholars cited articles in accounting journals. The common, but not universal, elements to the accountability definitions were (a) giving an account, (b) justifying one’s actions, (c) the actor being held to account with judgement to be made of the actor, and (d) possibility of sanctions on the organisation, with a mix of emphasis on accountability as obligation or response.

Table 3. Accountability definitions used in sport organisation articles.

Three articles were explicit regarding the type of accountability with reference to internal and external (Parent, Citation2016; Parent et al., Citation2017), and upward and downward (Houlihan & Preece, Citation2007). However, Nelson and Cottrell (Citation2016) and Pielke (Citation2013) utilised the most comprehensive accountability typology (i.e. hierarchical, supervisory, fiscal, legal, market, peer, and public reputational accountability). The use of typologies, and the explicit reference to types of accountabilities in sport organisation accountability research, is rare. Therefore, while there is a common understanding that accountability involves holding organisations to account, most studies are vague regarding to whom, and for what.

Arguably, the focus on holding organisations responsible has come at the expense of other accountability purposes. While accountability is commonly considered a universal remedy, the goals of accountability or theoretical mechanism of accountability are rarely used to explain how organisational behaviour is impacted. For example, while Havaris and Danylchuk (Citation2007) refer to accountability goals, there is little description of their case study organisation’s accountability goals. This is important, given that accountability is central to the pursuit of a variety of desirable objectives. Stenling and Sam (Citation2020) and Baxter et al. (Citation2019a) discuss pursuits of legitimacy, while others (Chappelet, Citation2011; Clune et al., Citation2019; Ghai & Zipp, Citation2021; Henne, Citation2015; Parent, Citation2016) refer to transparency. Potential accountability goals include liability, controllability, responsibility, responsiveness, and learning (Williams & Taylor, Citation2013). Consistent with Pielke (Citation2013), this review calls for future studies of sport accountability to explicitly state the accountability goal and type of accountability investigated.

4.2.4. Related concepts

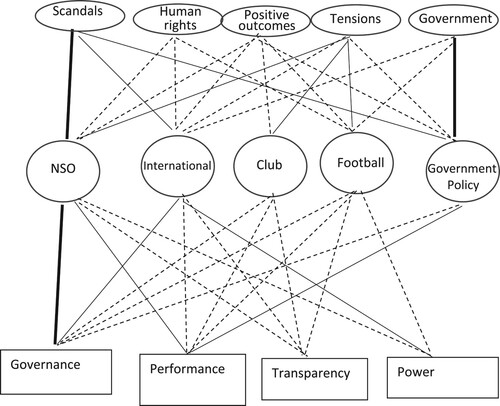

This review identified a variety of concepts related to sport accountability. While these terms are not sufficient to define accountability (Bovens, Citation2007), they are relevant to understanding organisation accountability and thus often discussed together (Parent, Citation2016). In order of prominence, related topic areas identified in the review include governance, performance, transparency, power, and responsibility. Concepts of liability, control, and response were almost non-existent. A mapping of the related accountability concepts is demonstrated in .

Governance featured in 20 (49%) of the accountability articles. Studies considered accountability as one principle of governance (Chappelet, Citation2011; Morales & Schubert, Citation2022; Muñoz et al., Citation2023; Parent, Citation2016; Parent et al., Citation2021; Parent et al., Citation2011), relating to the way in which organisations are accountable to their internal and external stakeholders. These studies highlight the importance of accountability in achieving governance of organisations.

Performance featured prominently in all writings of the most prolific authors (Parent, Citation2016; Parent et al., Citation2021; Parent et al., Citation2017; Parent et al., Citation2018; Parent et al., Citation2011; Sam, Citation2012; Sam & Macris, Citation2014; Sam & Ronglan, Citation2018). Studies that referred to organisation performance implied the requirement of measures to be accountable and vacillated between performance generally (Parent, Citation2016; Parent et al., Citation2021; Parent et al., Citation2017; Parent et al., Citation2011), financial efficiency, and on field sport or elite performance providing performance accountability (Sam, Citation2012; Sam & Macris, Citation2014; Sam & Ronglan, Citation2018).

Accountability has been linked frequently with transparency (Ghai & Zipp, Citation2021; Henne, Citation2015; Parent, Citation2016; Parent et al., Citation2017; Urdaneta et al., Citation2021) and disclosures (Clune et al., Citation2019). Unsurprisingly, this intersection occurred within studies of financial reporting (Clune et al., Citation2019; Urdaneta et al., Citation2021), and accountability stakeholders (Parent, Citation2016).

Power has also been associated with accountability (Geeraert et al., Citation2014; Nelson & Cottrell, Citation2016; Rika et al., Citation2016; Siddiqui et al., Citation2019). Some have argued that accountability mechanisms serve to maintain and enhance the positions of the most powerful especially during times of commercial expansion or shift from amateur to professionalism. Accountability mechanisms serve to protect and advance certain specific interests (Siddiqui et al., Citation2019). For example, stakeholders have exerted hegemony through accounting reports and control of financial resources to hold management responsible for financial losses (Rika et al., Citation2016). Additionally, sport organisations’ public and private position and social power from the humanitarianism and altruistic symbolism of sport provides difficulties to hold organisations to account (Nelson & Cottrell, Citation2016).

Responsibility has been associated with accountability in terms of financial costs (Baxter et al., Citation2019b) and organisational stakeholders (Parent, Citation2016). In the case of stakeholder perceptions, accountability was being responsible for one’s actions of performance, to superiors or external stakeholders.

4.2.5. Government policy

Impacts of government organisation policy on national sport organisations (NSOs) is another salient research theme in the prior literature. A number of studies (Ferguson et al., Citation2023; Houlihan & Preece, Citation2007; Tacon et al., Citation2017) referred to neoliberal and New Public Management (NPM) reform reshaping the context of sport organisations and that government funding imposed obligations and fiscal accountability that required NSOs to report to the government agencies, usually in the context of elite sport (Havaris & Danylchuk, Citation2007; Sam & Macris, Citation2014; Sam & Ronglan, Citation2018; Stenling & Sam, Citation2020). These studies suggest that the demand of accountability derives legitimacy for the government agency, and simultaneously impact NSOs which then demarcate elite and community sport. The performance accountability requirements of reporting in response to receiving government funds, accentuated and perpetuated competition among NSOs, creating “game playing”. While Parent et al. (Citation2018) found legislative changes enhanced the NSO focus on accountability, there are indications that reporting is an “accountancy” approach – minimal reporting, manipulations to meet funder requirements, financial emphasis, and little or no concerns for responsibility to obtain objectives (Havaris & Danylchuk, Citation2007). Outcomes are also restricted at the intersection of policy and practice (Ferguson et al., Citation2023).

5. Discussion and avenues for future research

Sport organisation accountability research is characterised by conceptual studies with the majority of studies lacking explicit theoretical perspectives. One decade-old criticism remains prescient – there is “no ambition of advancing academic theories of accountability” of sport organisations (Pielke, Citation2013, p. 256). This statement, made at a time of few academic articles examining sport organisations’ accountability, resonates with the approach of later studies that continue to omit an explicit naming of accountability related theories. Instead, researchers are content to apply a theory to explain or otherwise analyse a case. Explicit discussion of theoretical perspectives and greater use could be made of quantitative evidence, and greater debate on how accountability can be empirically measured in the context of sport organisations.

This section discusses future research on sport organisations’ accountability, in order of priority and significance. We structure this section according to theoretical perspectives, organisation responses, public reputational accountability, managerial accountability, accountability consequences, and finally organisation contexts.

5.1. Theoretical perspectives

The limited employment of theoretical perspectives discussed above, provides opportunities to develop those already used, as well as utilise additional theoretical perspectives. The foremost principal agency theory for corporate profit organisations has been applied less than institutional approaches in the sport setting containing nonprofit organisations. The interacting effect of logics and accountability remains largely unchartered, so provides another rich research opportunity to examine the interaction of accountability and other institutional logics. The related institutional theory of organisations responding to institutional norms to maintain legitimacy was also applied in five of the studies. Additionally, the institutionalism of increased commercialisation of sport (Geeraert et al., Citation2014; Morrow, Citation2013; Muñoz et al., Citation2023; Siddiqui et al., Citation2019), accountability shift towards greater managerial accountability (Clune et al., Citation2019; Renfree & Kohe, Citation2019) and New Public Management (Ferguson et al., Citation2023; Houlihan & Preece, Citation2007; Sam & Ronglan, Citation2018; Tacon et al., Citation2017) provides an opportunity for further examination. As part of this, we encourage researchers to consider (a) What accountability logics exist within sport organisations and why? (b) How is accountability connected with various institutional logics?

5.2. Organisation responses

Despite judgement, and response or answerability as requirements for full and fair accountability, these accountability components were rarely stated in the literature. Tacon et al. (Citation2017) and Stenling and Sam (Citation2020) have initiated some analysis of enactment and defensive conduct of organisations. Given the number of sport-accountability articles related to corruption, greater examination could be made of organisation responses and legitimising tactics in various forums, using concepts already used in the literature: legitimacy, framing, and silent/shadow/counter accounts. As part of this, we encourage researchers to consider the unique features and network that sport offers for a broader discourse of organisation responses to answer: (a) How do sports organisations react to threats of legitimacy or integrity? (b) How are verbal legitimation tactics used to justify organisational behaviour and choices in sport? (c) What accountability mechanisms have enabled sport organisations to acquire and maintain legitimacy?

5.3. Public reputational accountability

Despite the literature highlighting the inability to hold governing organisations to account, studies have not yet embraced public reputational accountability. “Public reputational accountability refers to the reputation of an organisation among superiors, supervisory boards, courts, fiscal watchdogs, markets and peers” providing a mechanism to hold organisations to account (Pielke, Citation2013, p. 260). Greater investigation of public reputational accountability is called for. A formal, and reasonably public source of legal and fiscal accountability is the annual report. Given the promise of public reputational accountability, and the ubiquity of annual reports, we encourage researchers to consider: (a) What the annual report provides for holding organisations accountable? (b) What is the role of the media in enhancing the accountability of sport organisations? (c) Are public reputational accountability or members and athletes (elsewhere referred to as participatory) accountability legitimate forms?

5.4. Managerial accountability

Many studies demonstrate how sport organisations are unable to be held accountable. This raises the need to examine the processes of organisation accountability and determine the impact of external accountability on internal management and operations of sports organsiations. The relationship between public organisational accountability and individual decision making in sport management studies is neglected in the sport management literature (Kellison, Citation2013). Further research could investigate managers’ perceptions of organisation accountability. The challenges of multiple and excessive accountabilities is an opportunity for sport accountability researchers (Behn, Citation2001; Campbell, Citation2002; Ebrahim, Citation2003; Lee, Citation2004; O’Dwyer & Unerman, Citation2008). More research or systematic reviews are needed to understand the relationship between organisation accountability and both decision making and behaviour. Some specific questions are as follows: (a) What gives rise to behavioural consequences of organisation accountability? (b) What theory (or theories) can best model multiple accountability? (c) How do sport managers, broadly defined, perceive organisation accountability and its associated requirements? (d) How do sport managers, negotiate the demands of multiple accountabilities? (e) How does external accountability impact internal hierarchical accountability?

5.5. Accountability consequences

Accountability is seen as a positive instrument while other research has found accountability systems have unintended behavioural consequences (e.g. lack of trust or dialogue (Swift, Citation2001), overburden (Lee, Citation2004), compliance and proceduralism (Bovens, Citation2005), mission drift (Yang & Northcott, Citation2019), accountability dilemma (Behn, Citation2001; Campbell, Citation2002), accountability paradox (Campbell, Citation2002; Dubnick & Frederickson, Citation2014), crowding out (Ebrahim, Citation2003; O’Dwyer & Unerman, Citation2008), or accountability gaps (Hooks et al., Citation2002; Lee, Citation2004)). Sport organisation accountability research has additionally found accountability legitimises organisations (Siddiqui et al., Citation2019), reinforces the elite sport organisation community (Sam & Macris, Citation2014), and provides hegemony over athletes (Bekker & Posbergh, Citation2022). Sport organisations held to account attempt to defend (Kellison, Citation2013), and protect their interests (Siddiqui et al., Citation2019). Thus, accountability issues may not be solved with more disclosure, or more transparency (Henne, Citation2015). On this basis we encourage researchers to explore the following questions: (a) What factors underpin the consequences of accountability? (b) What is the ideal balance of accountability for sport organisations?

5.6. Organisation contexts

The review highlighted that international sport organisations, national sport organisations, and government agencies were among the most studied. Given the complexity of the sport ecosystem (Buser et al., Citation2022) and accountability as a relational concept, there is value in conducting comparative studies and amongst organisations within the sport ecosystem. This can include comparisons between elite and non-elite organisations, and those with high and low levels of dependency on government funding. There is value in understanding accountability between and amongst organisations, especially those within nested hierarchies (i.e. multi-level governance) (Dickson et al., Citation2010), and more specifically clusters (Gerke et al., Citation2020), federated networks (Millar et al., Citation2022) and cliques (Meiklejohn et al., Citation2016).

6. Conclusion

Our scoping review of accountability in sports organisations demonstrates the nascent nature and unrealised interdisciplinary potential. Despite the accepted accountability movement (Carman, Citation2010), accepted neoliberal accountability movement in the public sector of society, accountability “frenzy” (Cooper, Citation2023), and demands of account giving and checking referred to as an “audit culture” (Tacon et al., Citation2017), the research community have been slow to examine sport organisations’ accountability. The abundant stakeholder concerns of sport organisation practices related to a lack of accountability is “not controversial” (Pielke, Citation2013), with resulting situations declared an accountability crisis (Millar et al., Citation2023; Pielke, Citation2013; Torchia et al., Citation2023), there remains opportunities for research of sport organisation accountability as proposed by our future research agenda.

Extant studies were found to be predominately conceptual, and more specifically, conceptually, and theoretically heterogenous. Their efforts to describe and explain accountability has not yet motivated researchers to pursue theoretical advances. This paper identified a variety of accountability definitions. The absence of a unified definition contributes to fragmented literature where researchers focus on different aspects of accountability. The diversity of definitions also creates conceptual confusion, leading to a lack of generalisability across studies. The need for further research in this area can inform consistent theory development and future systematic reviews. We also found that corruption and scandals are common justifications to pursue research of accountability (Chappelet, Citation2011; Jennings, Citation2011; Pielke, Citation2013). There are many other equally significant justifications to study accountability of sport organisations. Future research should consider using equality, participation, development, integrity, athlete wellbeing, and social outcomes to justify their accountability studies.

Moving forward, based on the themes and issues emerging from our scoping literature review, future research should carefully define the meaning of accountability. This review calls for open and explicit definitions of accountability. When applying the concept, researchers should continue to apply the argument of Gray et al. (Citation1996) to be specific to whom accountability is owed and for what purpose. Such actions would help to clarify conceptual elements in the research including performance, transparency, power, responsibility, and accountability logic.

Future research on sport organisations’ accountability should move beyond conceptual accounts and descriptive case study methodologies to use quantitative methodologies, and large sample sizes for identifying patterns, relationships, and trends across the sector. These approaches aim to generalise findings to reduce the complex concept of accountability into specific dimensions. Importantly, targeted dimensions using single variable sources may facilitate a deeper insight of the context dependent concept and facilitate clearer interpretations to gain a greater understanding of accountability nuances. For example, inquiries about accountability with stronger theoretical foundations such as that provided by institutional logics, as well as a consideration of public reputational accountability especially via annual reports, organisational responses, managerial implications, and the unintended consequences of organisation accountability can be considered.

In closing, we acknowledge the limitation of a scoping review provides no assessment of the quality of papers reviewed. This limitation has been addressed by selecting peer reviewed journals only to ensure a minimum standard of quality. We also again acknowledge the overlap between accountability and governance, a well-researched topic within the sport management literature. However, accountability is a concept of sufficient importance to justify more accountability-focussed studies. We also call for this research to better integrate research from multiple discipline perspectives. Integrating discourses is timely and has the potential to strengthen the theoretical perspectives of each discipline to positively guide the accountability practices of sports organisations, especially for those organisations that are currently struggling with such concepts and expectations as reported by the media globally.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Agostino, D., Saliterer, I., & Steccolini, I. (2022). Digitalization, accounting and accountability: A literature review and reflections on future research in public services. Financial Accountability & Management, 38(2), 152–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12301

- Aleksovska, M., Schillemans, T., & Grimmelikhuijsen, S. (2019). Lessons from five decades of experimental and behavioral research on accountability: A systematic literature review. Journal of Behavioral Public Administration, 2(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.30636/jbpa.22.66.

- Alm, J. (2013). Action for good governance in international sports organisations. Play the Game/Danish Institute for Sports Studies.

- Andon, P., & Free, C. (2019). Accounting and the business of sport: past, present and future. [Accounting and the business of sport]. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 32(7), 1861–1875. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-08-2019-4126

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Arunachalam, M., & McLachlan, A. (2015). Accountability for business ethics in the context of financial markets authority’s corporate governance principles. New Zealand Journal of Applied Business Research, 13(1), 19–34.

- Baxter, J., Carlsson-Wall, M., Chua, W. F., & Kraus, K. (2019a). Accounting for the cost of sports-related violence. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 32(7), 1956–1981. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-02-2018-3364

- Baxter, J., Carlsson-Wall, M., Chua, W. F., & Kraus, K. (2019b). Accounting and passionate interests: The case of a Swedish football club. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 74, 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2018.08.002

- Baxter, J., Kappelides, P., & Hoye, R. (2021). Female volunteer community sport officials: A scoping review and research agenda. European Sport Management Quarterly, 23(2), 429–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2021.1877322

- Behn, R. D. (2001). Rethinking democratic accountability. Brookings Inst Press.

- Bekker, S., & Posbergh, A. (2022). Safeguarding in sports settings: Unpacking a conflicting identity. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 14(2), 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2021.1920456

- Bovens, M. (2005). Public Accountability. In E. Ferlie, L. E. Lynn Jr, & C. Pollitt (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of public management (pp. 182–208). Oxford University Press.

- Bovens, M. (2007). Analysing and assessing accountability: A conceptual framework 1. European Law Journal, 13(4), 447–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0386.2007.00378.x

- Bovens, M. A. P., Goodin, R. E., & Schillemans, T. (Eds.). (2014). The Oxford handbook public accountability. Oxford Handbooks.

- Brennan, N. M., & Solomon, J. (2008). Corporate governance, accountability and mechanisms of accountability: An overview. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 21(7), 885–906. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570810907401

- Burga, R., & Rezania, D. (2015). A scoping review of accountability in social entrepreneurship. Sage Open, 5(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015614606

- Burger, S., & Goslin, A. (2005). Compliance with best practice governance principles of South African sport federations. South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education & Recreation (SAJR SPER), 27(1), 27–36.

- Burke, J. C. (2005). The many faces of accountability. In J. C. Burke (Ed.), Achieving Accountability in Higher Education: Balancing Public, Academic, and Market Demands (pp. 1–24). Wiley.

- Buser, M., Woratschek, H., Dickson, G., & Schönberner, J. (2022). Toward a sport ecosystem logic. Journal of Sport Management, 1(aop), 1–14.

- Busuioc, M., & Lodge, M. (2017). Reputation and accountability relationships: Managing accountability expectations through reputation. Public Administration Review, 77(1), 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12612

- Campbell, D. (2002). Outcomes assessment and the paradox of nonprofit accountability. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 12(3), 243–259. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.12303

- Carman, J. G. (2010). The accountability movement: What’s wrong with this theory of change? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 39(2), 256–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764008330622

- Chappelet, J.-L. (2011). Towards better Olympic accountability. Sport in Society, 14(3), 319–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2011.557268

- Chappelet, J.-L., & Mrkonjic, M. (2019). Assessing sport governance principles and indicators. In M. Winand, & C. Anagnostopoulos, (Eds.), Research handbook on sport governance (pp. 10–28). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Clune, C., Boomsma, R., & Pucci, R. (2019). The disparate roles of accounting in an amateur sports organisation. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 32(7), 1926–1955. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-06-2018-3523

- Cooper, J. (2023). Protecting human rights in sport: Is the Court of Arbitration for Sport up to the task? A review of the decision in Semenya v IAAF. The International Sports Law Journal, 23(2), 151–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40318-023-00239-4.

- Cooper, C., & Johnston, J. (2012). Vulgate accountability: Insights from the field of football. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 25(4), 602–634. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513571211225060

- Coy, D., & Dixon, K. (2004). The public accountability index: Crafting a parametric disclosure index for annual reports. The British Accounting Review, 36(1), 79–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2003.10.003

- Daudt, H. M., van Mossel, C., & Scott, S. J. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-48

- Deegan, C. (2009). Financial accounting theory. McGraw Hill.

- De Villiers, C., & Hsiao, P.-C. K. (2017). Why organizations voluntarily report–agency theory. In C. De Villiers & W. Maroun (Eds.), Sustainability accounting and integrated reporting (pp. 49–56). Routledge.

- Dhanani, A., & Connolly, C. (2012). Discharging not-for-profit accountability: UK charities and public discourse. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 25(7), 1140–1169. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513571211263220

- Dickson, G., Phelps, S., & Waugh, D. (2010). Multi-level governance in an international strategic alliance: The plight of the Phoenix and the Asian football market. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 22(1), 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1108/13555851011013191

- Dowling, M., Leopkey, B., Inoue, Y., Berg, B. K., & Smith, L. (2020). Scoping reviews and structured research synthesis in sport: Methods, protocol and lessons learnt. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 12(4), 765–774. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2020.1817126

- Dowling, M., Leopkey, B., & Smith, L. (2018). Governance in sport: A scoping review. Journal of Sport Management, 32(5), 438–451. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2018-0032

- Dubnick, M. (2005). Accountability and the promise of performance: In search of the mechanisms. Public Performance & Management Review, 28(3), 376–417.

- Dubnick, M. J., & Frederickson, H. G. (2014). Accountable governance: Problems and promises. Routledge.

- Ebrahim, A. (2003). Making sense of accountability: Conceptual perspectives for northern and southern nonprofits. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 14(2), 191–212. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.29

- Edwards, M., & Hulme, D. (1996). Too close for comfort? The impact of official aid on nongovernmental organizations. World Development, 24(6), 961–973. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(96)00019-8

- Edwards, A., Skinner, J., & Gilbert, K. (2004). Sport management: Varying directions towards the narrative. Kinesiology, 36(2), 220–232.

- El-Halaby, S., & Hussainey, K. (2015). The determinants of social accountability disclosure: Evidence from Islamic banks around the world. International Journal of Business, 20(3), 202.

- Ethics Index 2021. (2021). https://www.governanceinstitute.com.au/advocacy/ethics-index/.

- Ferguson, K., Hassan, D., & Kitchin, P. (2023). Policy transition: Public sector sport for development in Northern Ireland. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 15(2), 211–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2023.2183976

- Ferkins, L., & Shilbury, D. (2015). The stakeholder dilemma in sport governance: Toward the notion of “stakeowner”. Journal of Sport Management, 29(1), 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1123/JSM.2013-0182

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Cambridge University Press.

- Geeraert, A. (2019). The limits and opportunities of self-regulation: Achieving international sport federations’ compliance with good governance standards. European Sport Management Quarterly, 19(4), 520–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2018.1549577

- Geeraert, A., Alm, J., & Groll, M. (2014). Good governance in international sport organizations: An analysis of the 35 Olympic sport governing bodies. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 6(3), 281–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2013.825874

- Gerke, A., Woratschek, H., & Dickson, G. (2020). The sport cluster concept as middle-range theory for the sport value framework. Sport Management Review, 23(2), 200–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.12.004

- Ghai, K., & Zipp, S. (2021). Governance in Indian cricket: Examining the Board of Control for Cricket in India through the good governance framework. Sport in Society, 24(5), 830–845. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2020.1819598

- Grant, R. W., & Keohane, R. O. (2005). Accountability and abuses of power in world politics. American Political Science Review, 99(1), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055405051476

- Gray, R., Owen, D., & Adams, C. (1996). Accounting & accountability: Changes and challenges in corporate social and environmental reporting. Prentice hall.

- Greiling, D., & Spraul, K. (2010). Accountability and the challenges of information disclosure. Public Administration Quarterly, 34(3), 338–377.

- Grossi, G., Kallio, K.-M., Sargiacomo, M., & Skoog, M. (2019). Accounting, performance management systems and accountability changes in knowledge-intensive public organizations: A literature review and research agenda. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 33(1), 256–280. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-02-2019-3869

- Hackston, D., & Milne, M. J. (1996). Some determinants of social and environmental disclosures in New Zealand companies. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 9(1), 77–108. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513579610109987

- Halabi, A. K. (2021). The annual general meeting for Australian football clubs: An accountability and entertainment event. Accounting History, 26(1), 123–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/1032373220953509

- Hall, A. T., Frink, D. D., & Buckley, M. R. (2017). An accountability account: A review and synthesis of the theoretical and empirical research on felt accountability. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(2), 204–224. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2052

- Han, Y. (2020). The impact of accountability deficit on agency performance: Performance-accountability regime. Public Management Review, 22(6), 927–948. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1679237

- Havaris, E. P., & Danylchuk, K. (2007). An assessment of sport: Canada’s Sport Funding and Accountability Framework, 1995-2004. European Sport Management Quarterly, 7(1), 31–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184740701270329

- Henne, K. (2015). Reforming global sport: Hybridity and the challenges of pursuing transparency. Law & Policy, 37(4), 324–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/lapo.12044

- Hood, C. (2010). Accountability and transparency: Siamese twins, matching parts, awkward couple? West European Politics, 33(5), 989–1009. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2010.486122

- Hooks, J., Coy, D., & Davey, H. (2002). The information gap in annual reports. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 15(4), 501–522. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570210440577

- Houlihan, B., & Preece, A. (2007). Independence and accountability: The case of the drug free sport directorate, the UK’s National Anti-Doping Organisation. Public Policy and Administration, 22(4), 381–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952076707081584

- Hyndman, N., Lapsley, I., & Philippou, C. (2023). Exploring a soccer society: Dreams, themes and the beautiful game. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 37(2), 433–453. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-08-2023-6622

- Inoue, Y., Berg, B. K., & Chelladurai, P. (2015). Spectator sport and population health: A scoping study. Journal of Sport Management, 29(6), 705–725. https://doi.org/10.1123/JSM.2014-0283

- Jennings, A. (2011). Investigating corruption in corporate sport: The IOC and FIFA. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 46(4), 387–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690211408845

- Kay, T. (2012). Accounting for legacy: Monitoring and evaluation in sport development relationships. Sport in Society, 15(6), 888–904. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2012.708289

- Kellison, T. B. (2013). A framework of the highly visible sport manager’s ethical decision-making process. International Journal of Sport Management, 14(3), 357–378.

- Kihl, L. A. (2022). Development of a national sport integrity system. Sport Management Review, 26(1), 24–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/14413523.2022.2048548

- Kihl, L. A., Misener, K. E., Cuskelly, G., & Wicker, P. (2021). Tip of the iceberg? An international investigation of fraud in community sport. Sport Management Review, 24(1), 24–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2020.06.001

- Koppell, J. G. S. (2005). Pathologies of accountability: ICANN and the challenge of “multiple accountabilities disorder”. Public Administration Review, 65(1), 94–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2005.00434.x

- Lee, J. (2004). NGO accountability: Rights and responsibilities. Programme on NGOs and Civil Society, CASIN.

- Lee, S. (2022). When tensions become opportunities: Managing accountability demands in collaborative governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 32(4), 641–655. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muab051

- Lefebvre, A., Parent, M. M., Taks, M., Naraine, M. L., Séguin, B., & Hoye, R. (2024). Aligning governance, brand governance and social media strategies for improved organizational performance: A qualitative comparative analysis of national sport organizations. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 14(1), 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-03-2023-0031

- Lloyd, R. (2005). The role of NGO self-regulation in increasing stakeholder accountability. One World Trust, 1, 15.

- Mahmood, Z., & Uddin, S. (2021). Institutional logics and practice variations in sustainability reporting: Evidence from an emerging field. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 34(5), 1163–1189. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-07-2019-4086

- Meenaghan, T. (2013). Measuring sponsorship performance: Challenge and direction. Psychology & Marketing, 30(5), 385–393. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20613

- Meiklejohn, T., Dickson, G., & Ferkins, L. (2016). The formation of interorganisational cliques in New Zealand rugby. Sport Management Review, 19(3), 266–278.

- Messner, M. (2009). The limits of accountability. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 34(8), 918–938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2009.07.003

- Millar, J., Mueller, F., & Carter, C. (2023). Grassroots accountability: The practical and symbolic aspects of performance. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 37(2), 586–607. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-06-2022-5865

- Millar, R., Plumley, D., Wilson, R., & Dickson, G. (2022). Federated networks in England and Australia cricket: A model of economic dependency and financial insecurity. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 13(2), 161–180.

- Morales, N., & Schubert, M. (2022). Selected issues of (good) governance in North American professional sports leagues. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(11), 515. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15110515

- Morgan, A., & Wilk, V. (2021). Social media users’ crisis response: A lexical exploration of social media content in an international sport crisis. Public Relations Review, 47(4), 102057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2021.102057

- Morrow, S. (2013). Football club financial reporting: Time for a new model? Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 3(4), 297–311. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-06-2013-0014

- Mulgan, R. (2000). “Accountability”: An ever-expanding concept? Public Administration, 78(3), 555–573. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00218

- Muñoz, J., Solanellas, F., Crespo, M., & Kohe, G. Z. (2023). Governance in regional sports organisations: An analysis of the Catalan sports federations. Cogent Social Sciences, 9(1), 2209372. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2209372

- Naudí, S. A., Sanromà, J. C., Martin, R. S., Medina, F. X., Rovira, M. M., & Torné, S. M. (2019). Exploring charity sport events in Barcelona province: A phenomenon on the rise, albeit with pending issues. Retos: nuevas tendencias en educación física, deporte y recreación, 35, 229–235.

- Nelson, T., & Cottrell, M. P. (2016). Sport without referees? The power of the International Olympic Committee and the social politics of accountability. European Journal of International Relations, 22(2), 437. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066115589386

- Newman, J. (2004). Constructing accountability: Network governance and managerial agency. Public Policy and Administration, 19(4), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/095207670401900402

- O’Dwyer, B., & Unerman, J. (2008). The paradox of greater NGO accountability: A case study of Amnesty Ireland. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(7–8), 801–824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2008.02.002

- Ortega-Rodríguez, C., Licerán-Gutiérrez, A., & Moreno-Albarracín, A. L. (2020). Transparency as a key element in accountability in non-profit organizations: A systematic literature review. Sustainability, 12(14), 5834. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145834

- Parent, M. M. (2016). Stakeholder perceptions on the democratic governance of major sports events. Sport Management Review (Elsevier Science), 19(4), 402–416.

- Parent, M. M., Hoye, R., Taks, M., Thompson, A., Naraine, M. L., Lachance, E. L., & Séguin, B. (2021). National sport organization governance design archetypes for the twenty-first century. European Sport Management Quarterly, 23(4), 1115–1135. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2021.1963801

- Parent, M. M., Kristiansen, E., & Houlihan, B. (2017). Governance and knowledge management and transfer: The case of the Lillehammer 2016 Winter Youth Olympic Games. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, 17(4-6), 308–330. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSMM.2017.087441

- Parent, M. M., Naraine, M. L., & Hoye, R. (2018). A new era for governance structures and processes in Canadian National Sport Organizations. Journal of Sport Management, 32(6), 555–566. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2018-0037

- Parent, M. M., Rouillard, C., & Leopkey, B. (2011). Issues and strategies pertaining to the Canadian governments’ coordination efforts in relation to the 2010 Olympic Games. European Sport Management Quarterly, 11(4), 337–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2011.599202

- Parker, L. D. (2011). Twenty-one years of social and environmental accountability research: A coming of age. Paper presented at the Accounting Forum.

- Perechuda, I., & Čater, T. (2021). Influence of stakeholders’ perception on value creation and measurement: The case of football clubs. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 12(1), 54–76. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-03-2021-0035.

- Pham, M. T., Rajić, A., Greig, J. D., Sargeant, J. M., Papadopoulos, A., & McEwen, S. A. (2014). A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Research Synthesis Methods, 5(4), 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1123

- Philippou, C. (2022). Anti-bribery and corruption in sport mega-events: Stakeholder perspectives. Sport in Society, 25(4), 819–836. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2021.1957836

- Pielke, R., Jr. (2013). How can FIFA be held accountable? Sport Management Review, 16(3), 255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2012.12.007

- Pilon, M., & Brouard, F. (2023). Accountability theory in nonprofit research: Using governance theories to categorize dichotomies. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 34(3), 585–599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-022-00482-7

- Raiola, G., D’Elia, F., Esposito, G., Altavilla, G., & D’Isanto, T. (2023). The accountability of football as a form of public good on local communities: A pilot study. Physical Education Theory and Methodology, 23(2), 263–270. https://doi.org/10.17309/tmfv.2023.2.15

- Rana, T., Steccolini, I., Bracci, E., & Mihret, D. G. (2021). Performance auditing in the public sector: A systematic literature review and future research avenues. Financial Accountability & Management, 38(3), 337–359. https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12312

- Renfree, G., & Kohe, G. Z. (2019). Running the club for love: Challenges for identity, accountability and governance relationships. European Journal for Sport and Society, 16(3), 210–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2019.1623987

- Rika, N., Finau, G., Samuwai, J., & Kuma, C. (2016). Power and performance: Fiji rugby’s transition from amateurism to professionalism. Accounting History, 21(1), 75–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1032373215623017

- Roberts, J., & Scapens, R. (1985). Accounting systems and systems of accountability—understanding accounting practices in their organisational contexts. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 10(4), 443–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(85)90005-4

- Roberts, V., Sojo, V., & Grant, F. (2020). Organisational factors and non-accidental violence in sport: A systematic review. Sport Management Review, 23(1), 8–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2019.03.001

- Robertson, J., Dowling, M., Washington, M., Leopkey, B., Ellis, D. L., & Smith, L. (2021). Institutional theory in sport: A scoping review. Journal of Sport Management, 1(aop), 1–14.

- Sam, M. (2012). Targeted investments in elite sport funding: Wiser, more innovative and strategic? Managing Leisure, 17(2/3), 207–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/13606719.2012.674395

- Sam, M. P., & Macris, L. I. (2014). Performance regimes in sport policy: Exploring consequences, vulnerabilities and politics. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 6(3), 513–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2013.851103

- Sam, M. P., & Ronglan, L. T. (2018). Building sport policy’s legitimacy in Norway and New Zealand. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 53(5), 550–571. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690216671515