ABSTRACT

Research question

How is men’s mental health affected within male professional football?

Research methods

Within this qualitative study, eighteen current first-team professional footballers were interviewed from across the English Football League (EFL) to explore how male professional footballers are affected by mental health. Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis (2006) was applied along with “The Silences Framework” [Serrant-Green, L. (2010). The sound of “silence”: A framework for researching sensitive issues or marginalised perspectives in health. Journal of Research in Nursing, 16(4), 347–360] to allow the voices of this marginalised group to be heard.

Results and findings

The five key themes of social networks, environment, masking vulnerabilities, help-seeking and support, and mental health emerged from the data. The mental health theme is split into two sub-themes: impact on self and reaction of others.

Implications

This study makes an original contribution to the knowledge base as it is the first study to innovatively apply The Silences Framework to a sporting context. This study has applied The Silences Framework to show that professional footballers are affected by their mental health, and without appropriate access to support they continue to suffer in silence. This is likely to have negative consequences in their personal life, their football career, and their eventual transition away from being a professional footballer.

Introduction

In the UK, mental health issues within professional football often become headlines in the media (Bennett, Citation2020) and although this can be viewed positively to raise awareness, the intensity of social media platforms can highlight negative societal attitudes towards footballers experiencing mental health issues. Professional footballers have previously been viewed as people who should be immune from mental health issues due to their status, wealth, and adulation (FIFA, Citation2021). Gernon (Citation2016) suggests that society has little sympathy for footballers and there is a belief that footballers are overpaid, arrogant and egotistical, and goes further to say that mental health issues in footballers are not only unrecognised by society but also by the professional footballers themselves, which then exacerbates the silences around mental health in football.

This article explores the lived experiences of male professional footballers within the English Football League (EFL) to understand how men’s mental health is affected within male professional football. The Silences Framework (Serrant-Green, Citation2010) was utilised for this study as it is designed for researching issues which are little researched, silent from policy discourse and marginalised from practice. This study is significant because the lived experiences of professional footballers are a poorly understood phenomenon. This framework highlights that multiple perspectives and personal experiences are valued in constructing knowledge, and defines “Silences” as:

… areas of research and experience which are little researched, understood or silenced. (Serrant-Green, Citation2010, p. 347)

Introducing “the silences framework” (TSF)

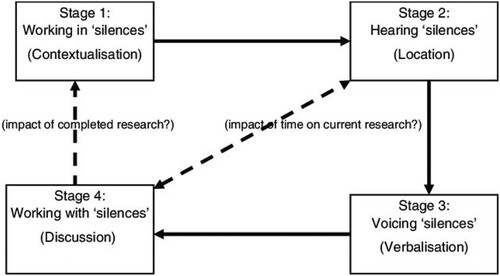

The TSF comprises four key stages to help guide the research process, and these stages will be used to present this article. The stages are as follows:

Stage 1: Working in Silences

Stage 2: Hearing Silences

Stage 3: Voicing Silences

Stage 4: Working with Silences

The first stage of the framework, Working in Silences, contextualises the study by exploring existing knowledge regarding the research subject itself and the characteristics of the situation in which the research takes place. This stage is where the critical literature review takes place, and in this study, this was focused on exploring mental health within football.

The second stage, Hearing Silences, aims to identify the silences at the centre of the planned research, i.e. the silences inherent in conducting this research study, by this researcher, at this time (Serrant-Green, Citation2010). Reflection is therefore required on the “Silences” arising out of the study involving the researcher, research subject and the research participants (Eshareturi et al., Citation2015). Within this stage, it is important to consider the authors’ identity and positionality within the research and in relation to the participants and the setting.

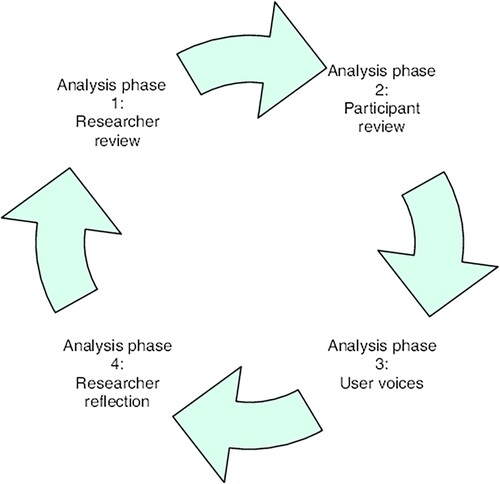

The third stage, Voicing Silences, is where the data collection and analysis take place. This stage is designed to collect the data and expose the situated views and experiences of those involved (Serrant-Green, Citation2010). This includes a four-phase cyclical analysis. In phase one, the data were analysed in reference to the research question to develop the initial findings. In phase two, the research participants were invited to review the initial findings to ensure that their voices were not silenced further. This Silence Dialogue helped to generate the draft 1 findings. In phase three, the user voices of the social networks of the participants were included to see if their views impacted the research question. The aim here was to hear from the Collective Voices reviewers to analyse the evidence through the experience of the research participants. This Collective Voices discussion alongside the consideration of the Silence Dialogue from Phase 2 helped generate the draft 2 findings. In phase four, the findings were reflected upon to present the final study outputs.

The fourth stage, Working with Silences, covers the discussion section of the research and enables the researcher to reflect upon the practical gains arising from the study. Recommendations arising from the research and the implications of this study for further research emerge within this stage. The below diagram shows TSF and highlights how one stage progresses to the next ().

Figure 1. The silences framework (Serrant-Green, Citation2010).

Stage 1: working in silences

Within elite sports, Albisu (Citation2018) believes that members of a team are expected to make sacrifices and to be loyal to teammates and that camaraderie can produce a culture of silence. Although Moriconi and Cima (Citation2020) report this culture of silence in relation to deviant and corrupt behaviour, this idea of being loyal to teammates may also silence footballers who are struggling with their emotional well-being. According to Donaghey et al. (Citation2011) staying silent can be an adopted communicative choice, and athletes may also stay silent to prevent any potential repercussions from an organisational perspective. Although there is no formal written agreement regarding loyalty between teammates, Albisu (Citation2018) suggests that teammates may not speak out due a fear of ostracism or rejection from others.

Morrison (Citation2014) states that if an employee’s voice is silenced within an organisational context, both performance and employee morale may suffer, so the consequences may be significant. If an athlete feels silenced the potential detrimental impact on their performance will increase the pressure that they experience and therefore exacerbate their levels of stress. Athletes frequently cite performance-related pressure as a source of stress within competitive sports (McKay et al., Citation2008), and according to Arnold and Fletcher (Citation2012), elite athletes are susceptible to hundreds of stressors that may induce common mental disorders. These stressors may increase an athlete’s susceptibility to injury, which is the most significant risk factor for psychological distress amongst professional footballers (Gouttebarge et al., Citation2015), and is one of the most recognised risk factors for psychological distress amongst male elite athletes (Wolanin et al., Citation2015). Gervis et al. (Citation2019) found that long-term injuries can have a significant psychological impact on professional footballers, and in addition to injury, the extreme load of physical training can impact psychological stress (Nixdorf et al., Citation2013). This plethora of stress can have a debilitating effect on the emotional well-being of athletes; however, athletes, particularly footballers, may choose to suffer in silence rather than be perceived to be letting their teammates down. If a man is perceived to have let their teammates down it can contradict the hegemonic male ideal of masculinity. This concept traditionally embodies qualities such as being strong, successful, capable, unemotional, and in control (Connell, Citation2003), and appears important within football. Sports can define and strengthen traditional masculine principles (Amodeo et al., Citation2020) and can be where boys learn values and behaviours such as competition, toughness and winning-at-all-costs (Steinfeldt & Steinfeldt, Citation2012).

Within this study, the “Working in Silences” stage explored the impact of silence in relation to elite sport and professional football and provides the justification for researching this particular subject at this particular time.

Stage 2: hearing silences

Within this stage, it is essential for the researcher to identify their positionality in relation to the subject being investigated. Serrant-Green (Citation2010) suggests that researcher identity forms the central mechanism by which all other silences are heard and located within the context of the study. To explore the lead author’s research identity, it is important to acknowledge the personal and professional drivers for undertaking this research. Positionality necessitates the researcher consciously examining their own identity to allow the reader to understand how the data was gathered and the effect of the researcher’s personal characteristics in relation to the study (Massoud, Citation2022).

The lead author is a Registered Mental Health Nurse (RMN) with over 20 years’ experience within both the National Health Service (NHS) and Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). The lead author’s training and experience in mental health counselling skills have been key to extracting data related to a sensitive subject from a marginalised group. This was helped by having significant experience of facilitating sensitive and confidential discussions with men experiencing mental illnesses, and by having the ability to effectively build trusting therapeutic relationships with men who have experienced trauma and distress.

During the data collection phase of this study, 18 participants were interviewed, all of which had never previously met, or heard of the authors. They all responded to the request to participate in this study as presumably they recognised the importance of mental health within football and felt that they could contribute to the discussion. As the interviews intended to ask questions about a sensitive subject, participant interviews were conducted in a similar way to approaching a clinical meeting with a mental health service user. The interviews were conducted using a person-centred approach and adopted the core conditions developed by Rogers (Citation1957). These core conditions of warmth, empathy, unconditional positive regard, and genuineness were essential to help the lead author acknowledge the participants as the experts of their own problems and to allow the silences to be voiced and heard. The use of these core conditions aided the provision of a safe environment for the participants, which enabled the development of an effective, trusting relationship.

Braun and Clarke (Citation2013) have the view that we are likely to have multiple insider and outsider positions. The authors are not professional footballers; therefore, they are outsiders to this industry. Green and Thorogood (Citation2014) discuss insider–outsider research and identify that an outsider position represents a detached analytic pursuit of generalisability, whilst an insider position suggests an informed and influential standpoint in which the researcher is deeply invested. Breen (Citation2007) compares insider and outsider researchers and suggests that generally, insider-researchers are those who choose to study a group to which they belong, while outsider – researchers do not belong to the group under study. Reed and Proctor (Citation1995) developed a position continuum which suggests a range of positions that can be taken throughout the research process. This fits with this research study, although the lead author is a fan and possesses a vast knowledge of football, they are an outsider looking in. However, as the study is researching men and their mental health in the context of work, the lead author is an insider and would share some group identity with the participants.

Recruitment

As research access in football appears to be an “impenetrable fortress” (Roberts et al., Citation2017), this study used the social media platforms Twitter and LinkedIn to recruit participants. Rickwood (Citation2012) believes that social media is an appropriate way to seek volunteers for mental health research. Utilising the lead author’s social media profiles, a recruitment poster was tweeted at regular intervals between November 2017 and September 2019. It was noticed that several current first-team footballers were either tweeting about their own mental health experiences or joining in online conversations regarding mental health. These individuals were then contacted to invite them to participate in the research as they were interested in mental health. Regular tweets and reminders advertising the study were posted and relevant football organisations were tagged to expand the reach. A video promoting the research and encouraging participation was also posted on LinkedIn. This was followed up at three monthly intervals with further posts to advertise the study and call for participants. The key inclusion and exclusion criteria were that participants had to be part of the first-team squad and not the development squad or academy.

Stage 3: voicing silences

Eighteen participants were recruited to take part in this study. All participants were current professional footballers within a first-team squad at EFL club. Four interviews were conducted face to face, five interviews were conducted using Skype or Zoom and the remaining six interviews were conducted by telephone. Interviews ranged from approximately forty-five minutes to approximately ninety minutes. One face-to-face interview only lasted fifteen minutes. Despite the participant’s willingness to be interviewed, his responses were brief and monosyllabic.

All interviews were recorded using the voice recorder app on an iPhone. The recorded audio files were then uploaded to a laptop and filed securely. The interviews that were conducted using Zoom were also video recorded using the Zoom recording facilities and converted into password-protected audio files. In preparation for the data analysis process, all audio recordings of interviews were transcribed verbatim.

The data was analysed by following the four-phase cyclical analysis process identified with TSF as shown in below. In addition to utilising TSF, Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) thematic analysis was used to understand the data and identify key emerging themes and sub-themes.

Figure 2. Phases of analysis in silences framework (Serrant-Green, Citation2010).

TSF highlights the importance of identifying the silences within the data. The Silences are the unspoken things as opposed to the moments just where people do not talk. Themes were identified based on an iterative process that considered patterns of behaviour of ways of thinking, feeling, and acting.

Phase 1 analysis: researcher review and initial findings

Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) six-step thematic analysis framework was used to analyse the data. All interview recordings were uploaded to NVivo and transcribed verbatim. Latent coding was then used to identify hidden meanings or underlying assumptions to interpret the data (Byrne, Citation2021). Inductive coding was used, and 57 codes were developed through a thorough analysis of the transcripts. Codes were combined to generate five key themes. It was anticipated that there would be a theme about mental health as it is the focus of the research, and the semi-structured interviews were based on this concept. The potential for bias was minimised through the process of reflexivity and understanding the lead author’s positionality within the research.

Phase 2 analysis: silence dialogue and draft 1 findings

Phase 2 of the four-phase cyclical data analysis process of TSF is known as the Silence Dialogue. For this phase, a summary of the initial findings of each theme was developed and then sent to each participant for them to sense check and make any additional comments that they felt relevant. Despite much critique of member checking in qualitative research, particularly by Smith and McGannon (Citation2017), who state that it is an ineffective method for the purposes of verification, the inclusion of user perspectives at this stage is essential for providing an additional checkpoint. This also allowed an opportunity to engage in a dialogue with the “silenced” participants about my situated view of the findings (Serrant-Green, Citation2010). Participants were asked if they recognised the themes within their experience of playing professional football. They were given a yes or no option for each theme and the opportunity to add further comments.

Ten participants responded, which is a 55% response rate. The initial findings summary was then amended to include their feedback, and this became the draft 1 findings summary.

Phase 3 analysis: collective voices and draft 2 findings

In Phase 3, the inclusion of “user” voices is expanded to include the social networks of participants or others whose cultural, social, or professional situation may impact the research question (Serrant-Green, Citation2010). This expansion of user voices is known as the Collective Voices and the purpose of these voices was to allow people within the wider social networks of the participants to provide their perspectives on the identified silences from stage 1 of the study. Within the phase 1 analysis, the key theme emerging was social networks. Within this, the participants referred to the following networks:

Female family members

Coaches/managers

Club physiotherapists

Counsellors

Sports psychologists

To be commensurate with the recruitment strategy, Twitter and LinkedIn were used to identify and recruit representatives from each of these identified groups. These Collective Voices were invited to participate in the Silence Dialogue review to offer any further insights into the issues identified. A total of ten Collective Voices reviewers, none of whom had any known relationships with the main study participants, provided feedback on the draft 1 findings summary. These included:

A first-team manager at an EFL Championship club

A first-team coach at an EFL League One club

A first-team physiotherapist at an EPL club

A first-team physiotherapist at an EFL League One club

Two psychologists with experience working with professional footballers.

A counsellor who has experience working with professional footballers through the Professional Football Association (PFA)

A counsellor/ Club Chaplain at an EPL club

The mother of a former Championship footballer

The wife of a League Two footballer

The draft 1 findings summary was then revised to reflect the comments from the Collective Voices feedback to arrive at draft findings 2 summary.

Phase 4 analysis: researcher reflection and final study outputs

In this final phase of the analysis, the authors were able to critically reflect on the findings from the previous three phases including the theme summaries, “draft findings 1” and “draft findings 2.” Through this reflection, the authors were able to follow the cyclical four-phase analysis and visit and review the development of the study findings. This process of analysis is central to aligning the Voicing Silences stage to the underpinning screaming silences which are the core of TSF.

It is important to demonstrate methodological rigour and trustworthiness in qualitative research, especially as it can be criticised for being unscientific, anecdotal, and based upon subjective impressions or lacking generalisability (Gray, Citation2014). Trustworthiness is the process of addressing the credibility, transferability, confirmability, and dependability of the current study (Creswell & Poth, Citation2018). To maintain credibility, all participants were offered the opportunity to review and comment on the initial findings developed from the phase 1 analysis. This process was used to generate the draft 1 findings.

The phase 3 or Collective Voices stage of the TSF data analysis process enabled members of the social networks identified by participants to further comment on the study findings. This feedback then informed the development of the draft 2 findings.

Transferability was established by ensuring that a thick description of the participants and research process has been provided. This study clearly describes the need for the research, the context in which the research was carried out, study inclusion criteria, the sample size and demographics, the method of analysis and the theoretical underpinning of the study. All these criteria ensure that there is sufficient detail for the reader to evaluate the extent to which the conclusions arrived at could be transferred to other settings (Korstjens & Moser, Citation2018).

Dependability was ensured by making all documents used to support the research and decision-making processes available for examination. The lead researcher conducted all interviews and transcribed fifteen out of the eighteen interviews to ensure consistency in these processes. The remaining three interviews were transcribed professionally; however, the lead researcher decided to resort to self-transcription to remain immersed in the data. Finally, confirmability was managed through maintaining an accurate audit trail including keeping a complete set of notes on decisions made throughout the research process (Korstjens & Moser, Citation2018).

This study was a doctoral research project conducted by the lead author. The co-authors were the doctoral supervisors who provided critical guidance throughout the project.

Ethical approval before the commencement of data collection was granted by the Faculty of Health and Wellbeing Faculty Research Ethics Committee, Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield, United Kingdom, reference number 2017-18/HWB-HSC-03.

Main findings

The following five main themes emerged: social networks, environment, help seeking and support, masking vulnerabilities, and mental health. The theme of mental health was divided into two sub-themes and labelled as (a) impact on self and (b) reaction of others.

Social networks

As footballers grow up through childhood and adolescence they rely heavily upon their families, and in particular their parents. It is evident from the findings that the main influence of the participants is their mum.

My mum is basically like our boss like she deals with everything. (#Int5)

I think from a very young age my mum instilled some good values in me. I’m fortunate in the fact that I'm 30 years old though I have been drip fed the old school principles and morals. (Int#6)

I’ve been brought up by my mum who’s a strong woman. I’m really a family man, my mum’s my world. (Int#11)

The findings also highlight that living with a professional footballer can be intense. The stress and pressure that players experience could potentially render them volatile and unpredictable and therefore have a detrimental impact on their intimate relationships. It is no surprise that Gernon (Citation2016) suggests that 33% of footballers are divorced within twelve months of career transition.

I was becoming snappy and this and that. She used to call me Jekyll and Hyde. One minute you’d be all right and the next you’d be down, and she said she’d be walking on eggshells around me because she didn’t know how I’d react. (#Int12)

My wife calls it like living with a ticking time bomb she just sort of never knows when I’m going to sort of kick-off. (#Int8)

I’ve got real good support network, my wife and kids and my close friends so I’ve never felt I’ve always been able to appreciate football for what it is, it’s football it’s my job. (#Int16)

She sacrificed probably more than me. We moved away for four and a half years so it’s just me and her. Her family to be fair came down and supported us but she made as much of a sacrifice as I did. (#Int1)

Environment

The career of a professional footballer can be a comparatively short-term affair, and most players are signed on relatively short, fixed-term contracts (Roderick, Citation2006). The issue of contracts is central to their footballing environment, and they can be a source of stress and uncertainty, particularly as the football labour market can be fragile (McGillivray & McIntosh, Citation2006).

Professional footballers are no different from employees in other industries as they need regular employment and a regular wage to have a good standard of living and pay their rent and bills. When they are unable to play because of injury, players can experience anxiety and constant self-doubt:

Because it was that point where you think you’ve not played for six, seven, eight months, who’s going to (a) offer you a contract to pay all your bills, and (b) well in general who’s going to offer you a contract? Where are you going to go next, sort of thing. I didn’t really have any security at the time. A lot of the money my wife and I at the time invested was in a house, so there was a lot, it was very much pay cheque to pay cheque living, rather than having a security. (Int#9)

And I knew what was coming, I had three months left of my contract and when you’re like that you’re looking elsewhere, you need to be out and playing and be in the shop window to try and get a contract elsewhere. (Int#12)

I mean, I’m only on a short-term contract now. So being 33 years old … and I had a bad leg break two seasons ago that I've managed to come back from at the end of last season. And I’m fully aware that you know, this contract well be my last one in professional football. (Int#7)

Gouttebarge et al. (Citation2015) propose that injury is the most significant risk factor for psychological distress amongst professional footballers and when combined with contract anxiety can have a significant impact on a player. Being injured may affect a player’s ability to work and can create a source of conflict (Roderick, Citation2006). Within football, the player-as-worker is put under pressure to “produce the goods” or else face rejection (Roderick, Citation2003).

Masking vulnerabilities

Football reflects masculine codes like strength, power, and competition (Kaelberer, Citation2020), and embraces the form of masculinity that traditionally relies on the public demonstration of violence, aggression, and physical prowess, alongside a violent rejection of femininity and homosexuality (Adams, Citation2011). This masculinity is reflected throughout football and in particular the team talks either before kick-off or during the half-time interval. These team talks have military characteristics, and the language used can be interpreted in categories of battle orders (Herzog, Citation2019).

you’re going to win the battle against him. (Int#9)

it’s just natural to be strong on the pitch and fight. (Int#10)

Connell’s (Citation2008) concept of hegemonic masculinity also applies to the changing room which is a place where camaraderie and banter are prevalent. Banter is often a tool used to initiate conversations and create cohesion. Participants stressed the need to be able to survive within the dressing room and this implies that players need to have a “thick skin”.

you have to have thick skin, otherwise you just won’t survive, to be honest with you. (Int#7)

I think if you can’t survive in a dressing room then you're not going to survive on a pitch. (Int#2)

It’s very hard to show your vulnerability in a football changing room very, very hard. (Int#7)

Help-seeking and support

Participants have acknowledged that they have been reluctant to seek help which can then have a detrimental effect on them. Almeda et al. (Citation2017) found that help-seeking is most effective when individuals access support when problems first arise, and DeBate et al. (Citation2018) state that the longer the individual delays reaching out the more likely they are to develop unhealthy coping strategies and subsequent adverse emotional outcomes. Wood et al. (Citation2017) discussed the concept of survival within professional football. Due to either the perceived barrier or lack of support players can feel that they must keep going and may only reach out when they reach a crisis point.

well it’s difficult because the tip of the spear’s the manager, isn’t it? So, it’s very difficult to open up to a manager about issues and about things like that when he’s the one that picks you. He’s the one that runs your life. So, if he sees you as being weak, he’s not going to pick you. (#Int11)

If you ever said look, I’m struggling a little bit here, it is probably seen as a weakness to be honest. I’m not saying that’s the same at every club or every coach or every manager but what I sort of experienced I’d say nobody I know has approached a manager to say I’m really struggling a bit. (#Int1)

This is my issue at the moment, so the PFA are nowhere near good enough at telling people where to go if they need help. It's almost like you have to hit rock bottom first before you then get help. There's no preventative help. There's no support. (Int#16)

I think help seeking in football generally should come from the union. I think that it’s impartial. Well, it should be impartial, it should be separate. So, then you’ve got someone you can go to with any issues and get them dealt with any time of the day wherever you are. I think that could help. Having a little slogan saying, you know, we’ll help you with your mental health is not enough. (Int#11)

The help for footballers is there without a shadow of a doubt, I'll be honest, I found that out in in recent weeks, because I've made contact with the PFA and through sporting chance I've been seeing somebody for the last couple of weeks. (Int#8)

Mental health – impact upon self

These findings have identified that the most common symptom of mental health that has had a detrimental impact on several participants within this study is that of anxiety.

One of the participants discussed experiencing panic attacks throughout his childhood and into adulthood:

You always look at the bad side first. Any little thing that can happen you're always worrying about everything, it’s like quite exhausting because constantly panicking about every little scenario. (Int#3)

I was in quite a bad way to the point where I would go in train, go in for breakfast at nine, we'd leave about 1 every day and I'd literally just go home to bed close the curtains and I wouldn't leave my bed until the next day. I had no social life wouldn't talk to anyone. (Int#3)

I wasn’t depressed but I was very down. I questioned my career. I questioned whether or not I wanted to play anymore, I questioned my motivation, all that kind of thing and, you know, it was hard. I was waking up every morning absolutely zonked. I was getting 10 hours sleep, waking up and I felt like I had one hour’s sleep. (Int#11)

Mental health – reaction of others

It is evident from the findings that stigma regarding mental health and mental illness continues to exist within professional football. This stigma correlates with being judged. Judgement from others is a core concept within football, and that can create uncertainty and doubt. Footballers are constantly judged, by their manager and coaches, teammates, fans, and the media.

And it is a hard thing, people judge you daily I think in our work environment. You’re always told you’re not good enough, you need to do this better, you need to do that better and if you don’t do this he’s playing and you haven’t pulled up trees in training this week, he looked better, he looked sharper so I’m playing him. (Int#12)

But behind closed doors, sometimes people don't understand how tough it can be. Since the age of six, I've constantly been judged and been told whether I am or aren't good enough, whether I'm good enough to be in a team where I'm not good enough to be in a team or if I am good enough to be discovered, I'm not good enough to be at these clubs. Those are the daily things that we go through as footballers, that's a tough thing to deal with. But that's our norm that's what we are expected to do every day, you know, we constantly live our life based on someone else's opinion. That can be a tough thing to deal with. You know, it can be tough, especially when you might go to one club, it doesn't work out and you go to another and it doesn't work out and you kind of in two or three clubs and you think to yourself why? Am I good enough? Those things can start to build momentum and play on your mind. (Int#13)

it’s like a taboo subject, you don't really mention it. Whenever I mentioned it to the physio it was kind of like whispered upon. We'd have secret conversations about it, no-one wanted to really let it out of the room. (Int#3)

Stage 4: working with silences

This study set out to “give voice” to first-team professional footballers in relation to their lived experiences of mental health and mental illness. Despite being an outsider to the football industry, the response rate indicates that a group of professional footballers were keen to have their voices heard.

It is important to acknowledge that female professional footballers also experience mental health challenges. Although this study only considers male professional football, there are opportunities for further research to explore the experiences of female footballers; similarly, this article has not focussed on the issues for retired professional footballers and this is an area of further research.

Within this study, the stories of eighteen professional footballers who were current players at the time of the interview have been captured. Although some of the participants have played in the EPL at some point during their career, we were unable to recruit participants directly from EPL clubs. Football is a closed shop (Roderick, Citation2003), and our experience of attempting to recruit players from EPL clubs reinforces this view. Law (Citation2019) discusses the challenges of attempting to recruit a sample of professional footballers to engage in qualitative research. He suggests that without having an “insider” status gaining access to professional football players for qualitative research, is almost impossible. This correlates with our experience of attempting to recruit premier league footballers.

A further limitation is that two-thirds of the study participants (66.6%) identified as white British, five participants (27.7%) were from a Black Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) background and one (5.5%) was white European. Black players make up 30% of professional footballers in England and Wales (Bennett Citation2021), and although the BAME sample within this study is almost 30%, the small sample size is not fully representative of the BAME population of the EPL and EFL.

There should be further research to explore mental health literacy within professional football. Research should be conducted to understand and evaluate the level of knowledge about mental health risk factors and causes, their understanding of specific disorders or presentations of psychological distress, and potential treatment and therapeutic interventions, all within the context of football. The findings can be transferable to professional football leagues around the world. Further research is recommended to understand the mental health issues internationally and to understand the transcultural issues that affect mental health within football globally.

This study has been the first study within sport to utilise TSF. It would be beneficial to apply this framework to other sporting groups who experience marginalisation and under-representation. Further testing of TSF to hear the unheard silences within football, in addition to applying the framework to exploring mental health issues across other elite sports would be advantageous.

Conclusion

This study has identified that there remains a reluctance for players to seek help for mental health symptoms and therefore they continue to suffer in silence. To improve the experiences of professional footballers and change their suffering in silence, professional football clubs should develop a holistic, person-centred approach to mental health. To support a holistic approach professional football clubs should appoint a well-being officer. This role would also act as a mental health champion, support existing structures in place within the club, and should have a particular focus on psychological well-being. The well-being officer would take action to raise awareness of mental health and challenge stigma. These individuals would also act as role models for other players to reach out to them to discuss their emotional well-being. These mental health champions should also be trained in mental health first aid. There should be further signposting to the support offered by the PFA, and acknowledgement that some players prefer accessing support away from football. Professional football clubs should employ qualified counsellors to improve access to psychological support, and there needs to be an increase in the number of clubs offering psychotherapeutic support to their players where appropriate.

There should be an increased focus on mental health support for released players. Many participants in this study have been released by a professional football club at some point in their career and as discussed, being released can trigger feelings of anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem. As Green (Citation2009) suggests that 99% of academy players do not make it through the youth development systems. Therefore, there will be a substantial population of young men being released from professional football who may then develop signs and symptoms of psychological distress. Professional football clubs should improve their aftercare packages for released players to include access and signposting to appropriate therapeutic support services.

If these recommended changes are introduced, they will have a positive impact on the mental health of both current and former footballers. The culture around help-seeking will improve, and there will be fewer male athletes suffering in silence.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adams, A. (2011). “Josh wears pink cleats”: Inclusive masculinity on the soccer field. Journal of Homosexuality, 58(5), 579–596. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2011.563654

- Albisu, I. (2018). Best practices for whistleblowing in sport. In Anti-corruption helpdesk, transparency international. Retrieved October 15, 2019, from https://knowledgehub.transparency.org/helpdesk/best-practices-for-whistleblowing-in-sport

- Almeda, V., Baker, R., & Corbett, A. (2017). Help avoidance: When students should seek help, and the consequences of failing to do so. Teachers College Record, 119(3), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811711900303

- Amodeo, A., Antuoni, S., Claysset, M., & Esposito, C. (2020). Traditional male role norms and sexual prejudice in sport organizations: A focus on Italian sport directors and coaches. Social Sciences, 9(12), 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9120218

- Arnold, R., & Fletcher, D. (2012). A research synthesis and taxonomic classification of the organisational stressors encountered by sports performers. Journal of Sport Exercise and Psychology, 34(3), 397–429. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.34.3.397

- Baguley, C., Briddon, J., & Bramley, J. (2011). Helping people recover from anxiety. In S. Pryjmachuk (Ed.), Mental health nursing; and evidence-based introduction (pp. 147–182). Sage.

- Bennett, M. (2020). Understanding the lived experience of mental health within English professional football [PhD]. University of East Anglia.

- Bennett, M. (2021). Behind the mask: demedicalising race and mental health in professional football. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 8(4), 264–266.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research; a practical guide for beginners. SAGE.

- Breen, L. (2007). The researcher ‘in the middle’: Negotiating the insider/outsider dichotomy. The Australian Community Psychologist, 19(1), 163–174.

- Byrne, D. (2021). A worked example to Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Quality & Quantity, 56(3), 1391–1412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y

- Claringbould, I., & Adriaanse, J. (2015). “Silver cups versus ice creams”: Parental involvement with the construction of gender in the field of their son’s soccer. Sociology of Sport Journal, 32(2), 201–219. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2014-0070

- Connell, R. (2003). Masculinities, change, and conflict in global society: Thinking about the future of men's studies. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 11(3), 249–266. https://doi.org/10.3149/jms.1103.249

- Connell, R. (2008). Masculinity construction and sports in boys’ education: A framework for thinking about the issue. Sport, Education and Society, 13(2), 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573320801957053

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). Sage.

- Dahò, M. (2020). The use of “the talking mask” in prison: An example case report. International Journal of Psychoanalysis and Education, 12(1), 76–83.

- DeBate, R., Gatto, A., & Rafal, G. (2018). The effects of stigma on determinants of mental health help-seeking behaviors among male college students: An application of the information-motivation-behavioural skills model. American Journal of Men's Health, 12(5), 1286–1296. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988318773656

- Donaghey, J., Culliinane, N., Dundon, T., & Wilkinson, A. (2011). Reconceptualising employee silence: Problems and prognosis. Work, Employment and Society, 25(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017010389239

- Eshareturi, C., Serrant, L., Galbraith, V., & Glynn, M. (2015). Silence of a scream: Application of the silences framework to provision of nurse-led interventions for ex-offenders. Journal of Research in Nursing, 20(3), 218–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987115577848

- FIFA.com. (2021). Martinez: Mental health is an issue we all face. Retrieved August 29, 2022, from https://www.fifa.com/news/martinez-mental-health-is-an-issue-we-all-face

- Gernon, A. (2016). Retired: What happens to footballers when the game’s up? Pitch Publishing.

- Gervis, M., Pickford, H., & Hau, T. (2019). Professional footballers’ association counselors’ perceptions of the role long-term injury plays in mental health issues presented by current and former players. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 13(3), 451–468. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.2018-0049

- Gouttebarge, V., Frings-Dresen, M., & Sluiter, J. (2015). Mental and psychosocial health among current and former professional footballers. Occupational Medicine, 65(3), 190–196. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqu202

- Gray, D. (2014). Doing research in the real world (3rd ed.). SAGE.

- Green, C. (2009). Every boy's dream. Bloomsbury.

- Green, J., & Thorogood, N. (2014). Qualitative methods for health research (3rd ed.). SAGE.

- Herzog, M. (2019). Footballers as soldiers. Rituals of masculinity in twentieth century Germany: Physical, pedagogical, political, ethical and social aspects. STADION, 43(2), 250–269. https://doi.org/10.5771/0172-4029-2019-2-250

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T., & Layton, J. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

- Jeanes, R., & Magee, J. (2011). Come on my son! Examining fathers, masculinity and “fathering through football”. Annals of Leisure Research, 14(2-3), 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2011.616483

- Kaelberer, M. (2020). Inclusive masculinities, homosexuality and homophobia in German professional soccer. Sexuality & Culture, 24(3), 796–808. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-019-09665-9

- Kola-Palmer, S., Lewis, K., Rodriguez, A., & Kola-Palmer, D. (2020). Help-seeking for mental health issues in professional rugby league players. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.570690.

- Korstjens, I., & Moser, A. (2018). Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. European Journal of General Practice, 24(1), 120–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/13814788.2017.1375092

- Law, G. (2019). Researching professional footballers: Reflections and lessons learned. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 1609406919849328. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919849328

- Massoud, M. (2022). The price of positionality: Assessing the benefits and burdens of self-identification in research methods. Journal of Law and Society, 49(S1), S64–S86. https://doi.org/10.1111/jols.12372

- McGillivray, D., & McIntosh, A. (2006). ‘Football is my life’: Theorizing social practice in the Scottish professional football field. Sport in Society, 9(3), 371–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430430600673381

- McKay, J., Niven, A., Lavallee, D., & White, A. (2008). Sources of strain among elite UK track athletes. The Sport Psychologist, 22(2), 143–163. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.22.2.143

- Moriconi, M., & Cima, C. (2020). To report, or not to report? From code of silence suppositions within sport to public secrecy realities. Crime, Law and Social Change, 74(1), 55–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-019-09875-0

- Morrison, E. (2014). Employee voice and silence. The Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 173–197. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091328

- Nixdorf, I., Frank, R., Hautzinger, M., & Beckmann, J. (2013). Prevalence of depressive symptoms and correlating variables among German elite athletes. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 7(4), 313–326. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.7.4.313

- Reed, J., & Proctor, S. (1995). Practitioner research in health care. Chapman & Hall.

- Rickwood, D. (2012). Entering the e-spectrum: An examination of new interventions for youth mental health. Youth Studies Australia, 31(4), 18–27.

- Roberts, S., Anderson, E., & Magrath, R. (2017). Continuity, change and complexity in the performance of masculinity among elite young footballers in England. The British Journal of Sociology, 68(2), 336–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12237

- Roderick, M. (2003). Work, self and the transformation of identity: A sociological study of the careers of professional footballers [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Leicester.

- Roderick, M. (2006). The work of professional football: A labour of love. Routledge.

- Rogers, C. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of the therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21(2), 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0045357

- Serrant-Green, L. (2010). The sound of “silence”: A framework for researching sensitive issues or marginalised perspectives in health. Journal of Research in Nursing, 16(4), 347–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987110387741

- Smith, B., & McGannon, K. R. (2017). Developing rigor in qualitative research: Problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357

- Steinfeldt, J., & Steinfeldt, M. (2012). Profile of masculine norms and help-seeking stigma in college football. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 1(1), 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024919

- Wixey, D. (2011). Talking football: An exploration into banter [Unpublished batchelor’s thesis]. University of Wales.

- Wolanin, A., Gross, M., & Hong, E. (2015). Depression in athletes: Prevalence and risk factors. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 14(1), 56–60. https://doi.org/10.1249/JSR.0000000000000123

- Wood, S., Harrison, L. & Kucharska J. (2017). Male professional footballers’ experiences of mental health difficulties and help-seeking. The Physician and Sportsmedicine, 45(2), 120–128.