?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Research question

This paper contributes to research concerned with gender comparison in sport, considering handball, traditionally overlooked in studies of competitive balance.

Research methods

We estimate measures of concentration and dominance to analyse the competitive balance in eight European handball leagues (both female and male) in four European countries (Denmark, France, Germany and Spain) during 15 seasons.

Results and Findings

The results show statistically significant differences between the female and the male handball leagues. With the exception of France, the level of concentration is higher in the female than in the male leagues. In terms of dominance, there is less difference between the genders. In terms of evolution, the indicators reflect a deterioration of the competitive balance mainly in the female leagues.

Implications

The analyses suggest that different measures should be put in place to increase the competitive balance in female leagues, through the transfer of resources from the male to the female leagues. To reduce the high level of dominance, a redistribution of resources among the teams should be considered to reduce the “drag effect”.

Research contribution

This is the first time that the most important European handball leagues have been examined to test the gender gap in competitive balance, with statistically significant differences being found.

1. Introduction

Competitive balance (CB) is one of the key concepts in sports economics. Its relevance is derived from the well-known uncertainty-of-outcome hypothesis (Rottemberg, Citation1956), which established that for a championship to be successful, the teams must be of relatively equal strength to ensure fan interest in the competition as well as revenues. Given the fundamental importance of CB, it is not surprising that there is a large and continually growing body of research literature on the subject, particularly on sports teams, that is pre-eminently focused on European football leagues (for a recent review of the relevant literature, see van der Burg [Citation2023]).

Only a minority of studies have dealt with gender comparisons for CB on sports teams. This evidence has again focused on football leagues in Europe, finding lower levels of CB in women’s leagues than in men’s leagues (e.g. Leite & Diniz da Silva, Citation2023; Pollard & Gómez, Citation2014). Similar results have been found for the UEFA Champions Leagues (François et al., Citation2022) and for the FIFA World Cups (Scelles, Citation2021). Nevertheless, Scelles (Citation2021) showed that CB for women is getting closer and closer to that of men’s football.

Although handball in Europe has evolved into a fully commercialised team sport, only a few papers on it have been published in the leading sports management journals (Meier et al., Citation2023). Handball is a particularly complex team sport with intermittent high intensity. It requires an extremely heterogenous repertoire of motor skills and refined team tactics (Saavedra, Citation2018; Wagner et al., Citation2014). These characteristics turn handball into a sport with great potential for the exploration of a variety of significant sports economics and management questions (Meier et al., Citation2023). Across the world, more than 30 million people play handball, and in 2023, there were more than 28,000 clubs and 209 national federations (Statista, Citation2023).

In Europe, handball has traditionally been a male sport, but female participation has significantly increased in many countries. For example, as of 2022, the proportion of female sports licences in France and Spain had climbed to 38% of all handball sports licences (Spanish High Council of Sport [CSD], Citation2023; Institut National de la Jeunesse et de l'Education Populaire [INJEP], Citation2023). In addition, handball in Europe is experiencing a great boost. In the EHF Champions League 2022/23, which is the most famous club competition in the world, the cumulative audience was 81 million for the men’s competition and 9.3 million for the women’s competition, with 63 and 22million fans, respectively, reached via digital channels (European Handball Federation [EHF], Citation2024a). More recently, in the 2024 European Men’s Handball Championship, more than 1 million fans attended the matches at the arena, while another 45 million were reached by television (TV) and social network users counted 400 million (European Handball Federation [EHF], Citation2024b). Logically, the financial figures in the world of handball are not like those in other sports, such as football. The average budget in the French men's handball league is around 5.5 million per club, dropping to 4.5 million in the German league and to 1.3 million in the Spanish league (Lopez, Citation2023).

This paper contributes to research concerned with gender comparisons in sports. The contribution of this work is twofold. First, it analyses a team sport, namely handball, that has traditionally been overlooked in studies of CB. Second, it addresses the distinction between the levels of CB between men’s and women’s handball competitions, an issue that has not previously been examined. Various standard indicators are also employed to facilitate comparisons with future studies. To achieve this, the research followed the theoretical approaches developed by Gerrard and Kringstad (Citation2022) to estimate measures of win dispersion (concentration) and performance persistence (dominance) and analyse CB in eight European handball leagues (female and male) in four European countries during 15 seasons, from the 2007–2008 season to the 2021–2022 season.

The structure of this paper is as follows. Section 2 describes the existing literature on the empirical measurement of CB using end-of-season league outcomes, paying particular attention to gender differences and with a primary focus on handball. Section 3 outlines the data and the measures used to estimate the level of CB for the leagues under study. Section 4 reports the empirical results. Section 5 discusses their implications, and Section 6 summarises the main conclusions.

2. Competitive balance: a gender approach

As CB is one of the key concepts in sports economics, the research literature is broadly split into two main tracks: an analysis of competitive balance (ACB) track and the uncertainty of outcome hypothesis (UOH) track (e.g. Fort & Maxcy, Citation2003; Gerrard & Kringstad, Citation2022). ACB research focuses on the measurement of CB in professional team sports over time and in different leagues. This strand considers two major aspects: level of concentration and level of dominance (Evans, Citation2014; Mondal, Citation2023; Plumley et al., Citation2023). In contrast, UOH research pays attention to the impact of uncertainty of outcome on gate attendance and TV audiences. van der Burg’s (Citation2023) recent literature review has shown that when is low, there is a negative and significant effect on sports demand.

Given the fundamental importance of CB, it is not surprising that there is a large and continually growing body of research literature on the subject, particularly about sports teams. Empirical ACB studies have tended to focus on empirical measures of CB based on end-of-season league outcomes. The assumption that CB is a multidimensional concept (Gerrard & Kringstad, Citation2022) has prompted a proliferation of empirical studies applying different measures of CB, and these studies are often difficult to compare.

As CB could be considered a public good (Bourg & Gouguet, Citation2010), it is necessary to regulate economic competition in some sport markets. This regulation is different in the US closed-league model than in the European open-league model (for more details, see Fort [Citation2000]). In the North American closed league systems, sport clubs look to maximise their profit, and this objective must be reconciled with the need to have a CB among teams. In this market, CB is sought by three instruments: the draft system, the salary cap system and the scale of revenue sharing. In the European model, sport clubs are win maximisers to avoid the risk of relegation to a lower division, and consequently, sport clubs must have suitable financial resources (Goddard, Citation2014). Another important difference is that European team sport clubs participate in international competitions (Sloane, Citation2006), mainly in European championships.

Traditionally, CB empirical analysis in Europe has focused on men’s football, since this is the most important team sport in Europe. Academic papers, such as those by Avila-Cano and Triguero-Ruiz (Citation2023), Plumley et al. (Citation2022), Ramchandani et al. (Citation2019, Citation2023a) and Serrano et al. (Citation2023), have shown a decrease in the levels of CB in the major European men’s football leagues, while other researchers have shown relatively stable levels of CB over the last 15 years (Frick et al., Citation2023). Although the findings are mixed, there is some evidence that low levels of CB affect the attractiveness of the competition and investment decisions over the long term by fans and supporters and by external stakeholders, such as broadcasters and commercial partners (Plumley et al., Citation2022; Ramchandani et al., Citation2019). However, it does not seem to be a constant phenomenon across all countries, as noted in the work by Scelles and François (Citation2021). These authors show that while, in general, a higher competitive balance positively affects stadium attendance in European football, it does not influence all countries in the same way. Grouping countries by economic inequality, it is observed that it is in the countries with the highest income inequality values where the existence of greater competitive balance has a more significant impact on higher attendance at sports stadiums.

Other studies have also analysed only men’s participation to estimate the level of CB in other sports. These studies include rugby (Avila-Cano et al., Citation2023), Formula One racing (Gasparetto et al., Citation2024), athletics (Truyens et al., Citation2016) and ice hockey (Arboix-Alió et al., Citation2021). In the case of handball, evidence is very limited. Hantau et al.’s (Citation2014) study was the first to focus on CB in this sport. They found a lack of CB in Romanian women’s handball. Subsequently, Meletakos et al. (Citation2016) and Meier et al. (Citation2023) showed a constant situation of imbalance in, respectively, the male Greek and German leagues.

Some studies have only recently shifted their attention to women’s leagues. This is the case of the analysis developed by Mondal (Citation2023) for the top five women’s football leagues. The author obtained a generally stable level of CB for these women’s football leagues in Europe but with significant differences among national leagues.

Gender comparisons in terms of CB are even scarcer. From a theoretical point of view, gender differences could be argued with the so-called Gould hypothesis (Gould, Citation1996) based on the underlying population of talent. Applied to sports, this hypothesis proposes a positive relationship between playing talent and CB. Gould (Citation1996) argued that the distribution of playing talent in a population follows a normal curve. At the right tail of the talent distribution lie the people with the highest level of ability, and these players show a relatively equal level of talent because of biomechanical limits (Schmidt & Berri, Citation2003). As the population of available players increases, the number of the most talented players grows (François et al., Citation2022). Consequently, the talent pool that sports teams can access will increase, boosting CB in the competition (Scelles, Citation2021; Schmid & Berri, Citation2003). Assuming that the underlying population of talented players is going to be a function of the number of male and female players, it would follow that, in general, CB would be greater in male leagues than in female leagues.

In addition, gender differences in CB may be justified considering the so-called “drag effect” (Zambom-Ferraresi et al., Citation2018) or “integration effect” (Valenti et al., Citation2021, Citation2023), and this happens when the female section of a club benefits from the infrastructure and staff of the professional male section. For example, integrated clubs have become increasingly common in European professional football leagues, such as the English league (Valenti et al., Citation2024) and the German, French and Swedish leagues (Hadwiger et al., Citation2024). This association enhances stadium attendance and visibility for women's teams, benefiting them from the brand spillover effect (Hadwiger et al., Citation2024) and comparably more considerable financial resources (Valenti et al., Citation2024). This situation gives a great advantage to some female clubs over others that do not have a male association. Consequently, it could be expected that the CB will be lower in the women’s leagues than in the male leagues.

Empirical evidence seems consistent with these arguments as it shows a greater level of CB in male team leagues than in female team leagues. Again, this evidence comes from football leagues in Europe, with studies finding lower levels of CB in women’s leagues than in men’s leagues (e.g. Leite & Diniz da Silva, Citation2023; Pollard & Gómez, Citation2014). Similar results have been found for the UEFA Champions Leagues (François et al., Citation2022), the UEFA men’s Nations League (Scelles et al., Citation2024) and for the FIFA World Cups (Scelles, Citation2021). Nevertheless, Scelles (Citation2021) showed for this last competition that CB for women has increased over time, getting closer and closer to men’s football. For some competitions, such as the Summer Olympic Games (Zheng et al., Citation2019) and the Commonwealth Games (Ramchandani & Wilson, Citation2014), the results are similar, with more balanced competition amongst the male athletes than the female athletes. Schmidt and Berri (Citation2003) and Arboix-Alió et al. (Citation2024) confirmed these differences in, respectively, five different team sports and in Spanish rink hockey. In the case of individual sports, the evidence is mixed. According to Leeds (Citation2019), the analysis of individual sports does not provide clear evidence that women and men behave differently in their competitions. Nevertheless, Frick and Moser (Citation2021) confirmed these differences in Nordic and Alpine skiing.

In the case of handball, Haugen and Guvag (Citation2018) explored the CB level in 13 European handball leagues for 2016, making a distinction between the genders. They found that the level of competition is lower in the female handball leagues than in the male ones. More recently, Kringstad (Citation2021) analysed the level of CB between genders in the Danish and German handball leagues in the period 2007–2008 to 2016–2017. His results showed low levels of competition, with the competition in the women’s leagues lower than that in the men’s, although not significantly so.

3. Data and methods

We considered four countries in our study: Denmark, France, Germany and Spain. The selection of these countries was not random. First, the most powerful leagues in this sport are located in Europe, so we chose some of the major European handball leagues: the Danish Men’s League (Handboldligaen), the Danish Women’s League (DHG), the French Men’s League (Liqui Moly Starligue), the French Women’s League (Ligue Féminine de Handball), the German Men’s League (Liqui Moly HBL, Handball-Bundesliga), the German Women’s League (HBL Frauen), the Spanish Men’s League (Liga Asobal) and the Spanish Women’s League (Liga Guerreras Iberdrola). These leagues are considered open based on the promotion–relegation rule. The number of teams varies among leagues. In the women’s leagues, the number of teams in each league is 14 teams. In the men’s leagues, the minimum number is 14 (Handboldligaen) and the maximum is 18 teams (Liqui Moly HBL). However, the competition format is identical, with a regular season of home and away matches followed by playoffs. The champion of the competition plays in the EHF Champions League, while the next four teams compete in the newly formed competitions: the EHF European League and the EHF European Cup.

Constrained by the availability of data, particularly for the women’s leagues, we examined 15 seasons, from 2007–2008 to 2021–2022. The data for all seasons per country and gender were retrieved from www.flashscore.com, an open access website that collects match results for different sports. This website has been widely used to obtain information about different sports (Pollard et al., Citation2017), such as tennis (Williams et al., Citation2021), basketball (Pérez-Chao et al., Citation2024) and handball (Matos et al., Citation2020). Unlike in other team sports, in a handball match, victory earns two points for the winning team, with each team getting one point for a draw. There are no points awarded to a team if it loses the match.

Different measures of CB have been used in the various empirical studies. At the same time, there has been a debate among researchers in recent years about the best measures, and that debate is not yet finished. The pros and cons of different measures of CB in professional team sports have been discussed in more detail by, for example, Lee et al. (Citation2019), Owen and Owen (Citation2022), Owen et al. (Citation2007) and Pawlowski and Nalbantis (Citation2019). This has prompted a proliferation of empirical studies applying different measures that are often difficult to compare. As Frick et al. (Citation2023) argued, we cannot consider one single measure to be the most appropriate indicator in every circumstance and for all sports and leagues, and no measure is inherently superior to the others (Owen & Owen, Citation2022). Each of the measures has strengths and weaknesses if it is attempted to be used as a single summary indicator of a complex phenomenon. For example, in North America, the standard deviation of win percentages is usually applied, but in Europe, this measure is considered as a biased indicator because of the high frequency of tied and drawn matches (Mondal, Citation2023; Pawlowski et al., Citation2010; Plumley et al., Citation2022).

Following Gerrard and Kringstad (Citation2022), it can be assumed that CB is a multi-dimensional concept that can be simplified using a two-dimensional categorisation of measures: a win dispersion or concentration measure; and a performance persistence or dominance measure. These two measures are not naturally, powerfully associated and may not even move in the same direction, as Gerrard and Kringstad (Citation2022) found in their research into 18 male football leagues in Europe. The main difference between these two aspects is that the identity of the team does not matter for concentration level but does matter for dominance level (Evans, Citation2014; Ramchandani et al., Citation2018). In this research, we have followed this framework, measuring the levels of concentration and dominance separately with several indicators.

The most widely-used measure of concentration is the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) and its different versions because it allows comparisons to be made among leagues with different numbers of teams as well as within leagues when the number of teams has changed over time (Owen et al., Citation2007; Owen & Owen, Citation2022). It has specifically been applied to study CB in the European football leagues and the UEFA Champions League (e.g. Depken & Globan, Citation2021; Meier et al., Citation2023; Plumley et al., Citation2022; Ramchandani et al., Citation2023a, Citation2023b; Scelles et al., Citation2022; Serrano et al., Citation2023; Zambom-Ferraresi et al., Citation2018). In our case, we applied the standardised HHI (HHI*) developed by Owen et al. (Citation2007), which is described in detail by Humphreys (Citation2019) and discussed by Owen and Owen (Citation2022) and Avila-Cano et al. (Citation2021) in their methodological papers. The advantage of the normalisation is that HHI* is confined to the interval [0, 1], with 0 indicating perfect balance and 1 representing maximum imbalance:

(1)

(1) where

, and

, so that

, with N being the number of teams.

and

The other measure typically considered in the analysis of CB is the Gini coefficient of the number of league points at the end of the season. Theoretically, the Gini coefficient can take any value between zero and one, where a value of zero denotes perfect equality and a value of one indicates maximal inequality. This last case implies that at the end of the season, one club has won all its matches, and all the other clubs have lost all their matches (Frick et al., Citation2023), but it is impossible for this to happen. The Gini measure has been extensively applied to professional team sports in Europe, which are mostly played as round-robin tournaments (each team plays each other team once at home and once away). The value of the Gini coefficient for end-of-season league points also depends on the number of clubs in the league, but the variations in the maximum values of the Gini coefficient are infinitesimal (Frick et al., Citation2023). The Gini index (Gi) is defined as follows:

(2)

(2) where n is the number of teams,

is the mean number of points obtained in the league and

is the number of points obtained by team i. The teams are ranked, x1 represents the points of the best, x2 denotes the points of the second-ranked team and so forth. This index will result in a value between 0 and 1 where 0 would stand for perfect equality and 1 for perfect inequality.

The third concentration measure is the concentration ratio of points, normally the points of the top five teams (CR5), which is applied in many studies (e.g. Meier et al., Citation2023; Pawlowski et al., Citation2010; Serrano et al., Citation2023; Zheng et al., Citation2019). The concentration ratio (CR) is expressed as:

(3)

(3) where r is the number of teams to be analysed and

is the market share of team i (the points obtained as a proportion of the total points of all the teams in the league). We calculated this index considering just five teams per season (CR5), regardless of the total number of participants in a league.

As concentration and dominance are not necessarily correlated with each other (Mondal, Citation2023; Plumley et al., Citation2023), we included in our analysis some measures to estimate the level of team dominance in each league, following previous empirical studies (Curran et al., Citation2009; Plumley et al., Citation2023; Ramchandani et al., Citation2018, Citation2023a, Citation2023b). We considered two indicators as our measure of dominance: the number of different teams that won each league title, and the number of different teams to finish in the top five positions in each league.

4. Empirical results

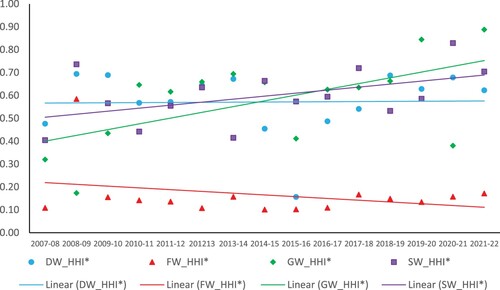

Following the methodological approach described in section 3, the first indicator for measuring the level of concentration is HHI*. and show the evolution of this indicator among the four female and four male European handball leagues. As we can see in , the levels of concentration for the women’s leagues show great differences for the period under analysis, with a negative trend for two out of the four leagues. The level of concentration increases over the last 15 years in the German and Spanish female leagues, while the French female league shows a slight improvement and the Danish league stays virtually constant.

Figure 1. Level of concentration among the female handball leagues. HHI* indicator. DW: Danish women’s league; FW: French women’s league; GW: German women’s league; and SW: Spanish women’s league.

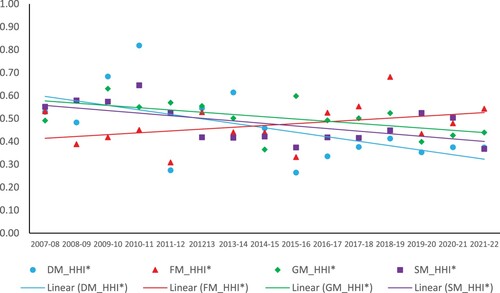

Figure 2. Level of concentration among the male handball leagues. HHI* indicator. DM: Danish men’s league; FM: French men’s league; GM: German men’s league; and SM: Spanish men’s league.

In the case of the male leagues, the evolution shown in is quite similar during the period, with a slightly decreasing trend for the concentration levels. Curiously, the French league is again the exception with a clear tendency to increase the concentration level during the period.

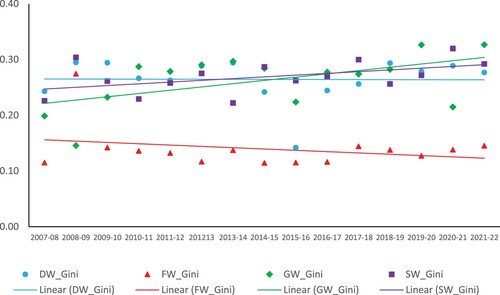

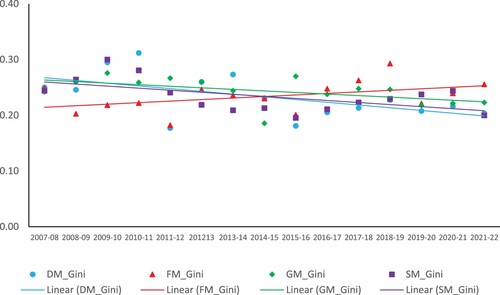

show, respectively, the HHI* values, the Gini indexes and the CR5 indicators for the leagues under study. The tables indicate that the level of concentration is higher in the female leagues than in the male leagues, except for the French league for the HHI* indicator and the Gini index.

Table 1. HHI* indicators for the handball leagues.

Table 2. Gini indexes for the handball leagues.

Table 3. CR5 indicators for the handball leagues.

For the Gini indexes in , a comparison of the countries shows that there are no differences among the male leagues during the period. There are some differences among the female leagues, with the Gini index for the French women’s league lower than the rest of the leagues. In terms of evolution, and show how the Gini index increases for the female leagues, apart from the French league, showing a deterioration of CB. In the male leagues, the evolution is the opposite, with the level decreasing for the Danish, German and Spanish leagues. In this case, the concentration increases only for the French male league.

Figure 3. Level of concentration among the female handball leagues. Gini indicator. DW: Danish women’s league; FW: French women’s league; GW: German women’s league; and SW: Spanish women’s league.

Figure 4. Level of concentration among the male handball leagues. Gini indicator. DM: Danish men’s league; FM: French men’s league; GM: German men’s league; and SM: Spanish men’s league.

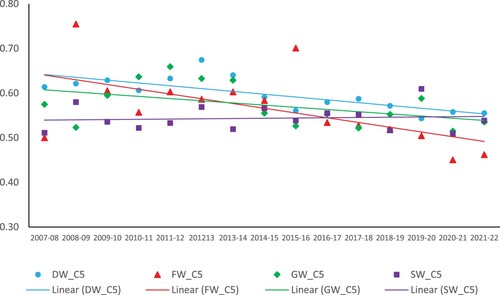

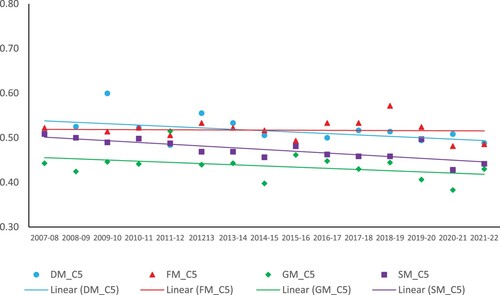

For the CR5 indicators, indicates a higher level of concentration among the female leagues compared to the male leagues, with the highest difference in the German leagues. In terms of evolution, shows a slight decrease in the CR5 for the female leagues during the 15 years for all the leagues, reaching the lowest value in the French case. displays a small decrease in the male leagues only in the case of the Spanish male league, with a stable trend for the rest of the countries.

Figure 5. Level of concentration among the female handball leagues C5 indicator DW: Danish women’s league; FW: French women’s league; GW: German women’s league; and SW: Spanish women’s league.

Figure 6. Level of concentration among the male handball leagues C5 indicator. DM: Danish men’s league; FM: French men’s league; GM: German men’s league; and SM: Spanish men’s league.

To test whether the differences between the values of the indicators of concentration for the male and female leagues are statistically significant, we first estimated the Shapiro–Wilk test of normality for each league and indicator (HHI*, Gini and CR5). in the Annex displays these estimations. In some cases (the Danish and French female leagues and the German male league), normality cannot be accepted for some indicators (values in red italics). Consequently, for these leagues and indicators, we applied the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test, while for the other cases, we used the equality of means test. indicates the results for these tests for each country and indicator. The results show that there are statistically significant differences between the male and female leagues, with a higher concentration among the female leagues apart from Germany for the Gini and HHI* indexes.

Table 4. Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney (WMW) test and equality of means test (T_TEST).

Finally, shows the level of dominance in the four European female and four European male leagues. In the case of the first indicator, that is, the number of different winners in the league, there are no real differences between the women’s and the men’s leagues, with the exception of the Spanish leagues in which there are more female winners than male winners. The highest number of league titles by a single club is 12: Barcelona in the case of the Spanish male league and Metz in the case of the French female league. In the French male league, two clubs (Paris Saint Germain and Montpellier) account for 93% of the winners. In these leagues, we could consider that there is a high level of dominance. To the contrary, the Danish leagues show the lowest level of dominance. In the case of the number of different top-five teams in each league, there are more teams among the female leagues than among the male leagues, except for the German leagues. In general, the differences among the leagues are lower for the top five positions than in the case of winners.

Table 5. Level of dominance in handball for the period 2007–2008 to 2021–2022.

5. Discussion

Our results verify the previous empirical studies in terms of gender differences in CB among leagues, particularly for the European football leagues (the studies of François et al., Citation2022; Kringstad, Citation2018; Leite & Diniz da Silva, Citation2023). For the European handball leagues, our results confirm the previous studies developed by Haugen and Guvag (Citation2018) and Kringstad (Citation2021). Nevertheless, our study is the only one that has found statistically significant differences between the male and the female handball leagues. Differences shown by Kringstad (Citation2021) were not statistically significant, and Haugen and Guvag (Citation2018) did not check for these differences.

From a theoretical point of view, the results are consistent with the Gould hypothesis (Gould, Citation1996) and the arguments developed by other authors (e.g. François et al., Citation2022; Treber et al., Citation2013). This hypothesis has been applied to explain the evolution of North American Major League Baseball (Schmidt & Berri, Citation2003) and for national football teams in international competitions (Scelles, Citation2021; Scelles et al., Citation2024), but this is the first time it has been applied to explain European team sports in domestic leagues. A higher level of sporting talent should be expected in men’s competitions, leading to increased competition among the handball men’s teams and a better CB. This could be the main argument to explain the differences that are shown in concentration by gender.

It is interesting that the Gould hypothesis seems valid for explaining the concentration level but not the dominance level. For the latter case, we show no clear differences by gender although there are some intraleague differences at the national level. This is the case of the French male and female leagues and the Spanish men’s league. In general, our results suggest a concentration of resources and players in certain teams in these three leagues that take advantage of their resources and synergies, and this has a negative effect on the uncertainty of the winning team. In the case of the women’s handball leagues, this higher level of dominance related to the men’s leagues could be associated with the situation in the male leagues. This is known as the “drag effect” (Zambom-Ferraresi et al., Citation2018) or “integration effect” (Valenti et al., Citation2021, Citation2023), and it happens when the female section of a club benefits from the infrastructure and staff of the professional male section. This situation gives a great advantage to some female clubs over others that do not have a male section. Although this effect is not widespread in handball in Europe, some clubs do benefit from it in some leagues, as is the case of the Granollers club in the Spanish league and the Danish Holstebro, Skanderborg and Silkeborg clubs.

At the same time, some handball teams have an advantage because the handball section receives financial and technical support from other sport sections, particularly from the football section. This situation could be called a “broad drag effect”, and in our study, happens in the case of Barcelona, Paris Saint German and BVD Dortmund.

Both effects could help us to understand the high value of winner dominance in some leagues. In these cases, a more equal distribution of revenues should be made among teams to reduce the high level of dominance shown. We would recommend that small teams with poorer infrastructure and fewer and less well-qualified staff receive better quotas in the league budget distribution during a period and for specific purposes. This recommendation is linked to the operation of North American professional team sports leagues to achieve better CB. From the European perspective, following this model might be afforded through the EHF. In addition, the incorporation of training compensation clauses in handball players’ transfer contracts akin to those present in football could acknowledge the investment and dedication of smaller clubs in nurturing handball talent. At the end, these measures would reduce the competitive distance among handball clubs, thereby increasing the attractiveness of competition, and would attract new fans, sponsors and so on.

As women’s leagues are less developed than men’s leagues, women’s leagues suffer from a much lower media appeal, financial support and sponsors, and fan presence (Leite & Diniz da Silva, Citation2023). This situation brings other consequences, such as a poorer material structure throughout the sports chain (sporting facilities, coaches, referees, etc.). One suggestion to reduce these differences between the genders is to distribute financial resources from the men’s leagues to the women’s leagues and to make a more equal distribution of these revenues among the women’s teams. This is a controversial measure that perhaps could not be separately developed in each national league, but it could be afforded by the EHF. At the same time, sport national authorities could support female handball with public resources, as is the case of the Spanish women’s league. These measures would increase uncertainty and competitiveness in the female leagues, attracting fan interest and new financial resources.

Some explanations can be put forward for the higher variability in the female leagues compared to the male leagues in the CB values for the period. As has happened with other sports, the process of professionalisation has not been as generalised and intensive in female teams as in male teams. For this reason, in the female competitions, there are teams with fewer resources competing against teams with much greater resources, potentially in the same league. But as has happened with other sport teams, some of these female clubs with fewer resources could unexpectedly have a good season; however, they will not be able to retain their best players in the next seasons. This could explain the high variability in the CB values between seasons in women’s handball leagues and the higher number of different teams in the top five each season.

Two limitations of this study are that it only measures the CB for eight European handball leagues (male and female) and does not measure either the drivers for the level of CB or the effects on fan interest. Still, the results and limitations should be a basis for further research. First, the inclusion of other European and non-European handball leagues in future studies could make it possible to discover gender differences in this sport around the world. Second, future research should determine drivers for these differences in CB for handball. This could help to verify whether the distribution of playing quality talent among teams is different between the genders and whether this could explain the gap in CB. Third, further research should consider the impact of these differences in CB on handball fan interest (e.g. arena attendance, TV audience and online viewership).

6. Conclusions

This paper analysed the gender differences in CB for four European handball leagues, those of Denmark, France, Germany and Spain, during a period of 15 years, from the 2007–2008 season to the 2021–2022 season. We distinguished between two aspects of CB: level of concentration and level of dominance. For the first, we considered three different indicators: HHI*, the Gini index and CR5. To measure the level of dominance, we included two indicators: the number of different teams that won each league title and the number of different teams to finish in the top five positions in each league. From a theoretical point of view, the so-called Gould hypothesis and the “drag” or “integration” effect support our empirical results.

In terms of levels of concentration, our results show that there are statistically significant differences between the female and male handball leagues under study, with a generally higher level of concentration for the female leagues than for the male leagues. From an evolution perspective, the indicators, except for the French female league, reflect a deterioration of CB among the female European handball leagues, with an increase in the concentration levels, particularly when this level is measured through the HHI* and the Gini index. In terms of dominance, the levels of dominance are lower in the men leagues than in the female leagues. There are some differences among countries. For example, the French leagues and the Spanish men’s league have a reduced number of different winners, showing a relative high level of dominance in the last 15 seasons.

Acknowledgement

Open access funding provided by Universidad Pública de Navarra.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arboix-Alió, J., Buscà, B., Aguilera-Castells, J., Fort-Vanmeerhaeghe, A., Trabal, G., & Peña, J. (2021). Competitive balance in male European rink hockey leagues. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 145, 33–38. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2021/3).145.05

- Arboix-Alió, J., Trabal, G., Moreno-Galcerán, D., Buscà, B., Arboix, A., Vaz, V., Sarmento, H., & Hileno, R. (2024). The effect of situational variables on women’s rink hockey match outcomes. Applied Sciences, 14(9), 3637. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14093627

- Avila-Cano, A., Owen, P. D., & Triguero-Ruiz, F. (2023). Measuring competitive balance in sports leagues that award bonus points, with an application to rugby union. European Journal of Operational Research, 309(2), 939–952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2023.01.064

- Avila-Cano, A., Ruiz-Sepulveda, A., & Triguero-Ruiz, F. (2021). Identifying the maximum concentration of results in bilateral sports competitions. Mathematics, 9(11), 1293–1219. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9111293

- Avila-Cano, A., & Triguero-Ruiz, F. (2023). On the control of competitive balance in the major European football leagues. Managerial and Decision Economics, 44(2), 1254–1263. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.3745

- Bourg, J. F., & Gouguet, J. J. (2010). The political economy of professional sport. Edward Elgar.

- CSD, Spanish High Council of Sport. (2023, October 15). Licences for sport. https://www.csd.gob.es/es/federaciones-y-asociaciones/federaciones-deportivas-espanolas/licencias

- Curran, J., Jennings, I., & Sedgwick, J. (2009). Competitive balance’ in the top level of English football, 1948–2008: An absent principle and a forgotten ideal. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 26(11), 1735–1747. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523360903133087

- Depken, C., & Globan, T. (2021). Domestic league competitive balance and UEFA performance. International Journal of Sport Finance, 16(4), 196–205. https://doi.org/10.32731/ijsf/164.112021.03

- European Handball Federation, EHF. (2024a). European Handball 2023. EHF Business Reports. https://www.eurohandball.com/en/what-we-do/publications/business-reports/

- European Handball Federation, EHF. (2024b). Summary of the EHF Euro. Retrieved May 15, 2024, from https://ehfeuro.eurohandball.com/news/en/coverage-of-men-s-ehf-euro-2024-28-january/

- Evans, R. (2014). A review of measures of competitive balance in the “analysis of competitive balance” literature. Birkbeck Sport Business Centre Research Paper Series V7(2).

- Fort, R. (2000). European and North American sports differences(?). Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 47(4), 431–455. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9485.00172

- Fort, R., & Maxcy, J. (2003). “Competitive balance in sports leagues: An introduction”. Journal of Sports Economics, 4(2), 154–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002503004002005

- François, A., Scelles, N., & Valenti, M. (2022). Gender inequality in European football: Evidence from competitive balance and competitive intensity in the UEFA men’s and women’s Champions League. Economies, 10(12), 315. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10120315

- Frick, B., & Moser, K. (2021). Are women really less competitive than men? Career duration in Nordic and Alpine skiing. Frontiers in Sociology, 5(January), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2020.539766

- Frick, B., Quansah, T. K., & Lang, M. (2023). Talent concentration and competitive imbalance in European soccer. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 5(March). https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2023.1148122

- Gasparetto, T., Orlova, M., & Vernikovskiy, A. (2024). Same, same but different: Analyzing uncertainty of outcome in Formula One races. Managing Sport and Leisure, 29(4), 651–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2022.2085619

- Gerrard, B., & Kringstad, M. (2022). The multi-dimensionality of competitive balance: Evidence from European football. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 12(4), 382–402. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-04-2021-0054

- Goddard, J. (2014). The promotion and relegation system. In J. Goddard & P. Sloane (Eds.), Handbook on the economics of professional football (pp. 23–40). Edward Elgar.

- Gould, S. (1996). Full house: The spread of excellence from Plato to Darwin. Three Rivers Press.

- Hadwiger, J., Schmidt, S. L., & Schreyer, D. (2024). Integrated women’s football teams can attract larger stadium crowds. European Sport Management Quarterly, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2024.2347287

- Hantau, C., Alexandru, A., Yannakos, A., & Hantau, C. (2014). Analysis of the competitional balance in the Romanian women handball. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 117, 672–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.02.280

- Haugen, K. K., & Guvag, B. (2018). Uncertainty of outcome and rule changes in European handball. European Journal of Sport Studies, 6, 12. https://doi.org/10.12863/ejssax6x1-2018x2

- Humphreys, B. R. (2019). Una guía práctica para medir el balance competitivo. Funcas, Papeles de Economía Española, 159, 43–60.

- INJEP, Institut National de la Jeunesse et de l'Education Populaire. (2023, September 24). Observatoire de la jeunesse, du sport, de la vie associative et de l'éducation populaire. https://injep.fr/publication/les-licences-annuelles-des-federations-sportives-en-2022/

- Kringstad, M. (2018). Is gender a competitive balance driver? Evidence from Scandinavian football. Cogent Social Sciences, 4(1), 1439264. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2018.1439264

- Kringstad, M. (2021). Comparing competitive balance between genders in team sports. European Sport Management Quarterly, 21(5), 764–781. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2020.1780289

- Lee, Y. H., Kim, Y., & Kim, S. (2019). A bias-corrected estimator of competitive balance in sports leagues. Journal of Sports Economics, 20(4), 479–508. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002518777974

- Leeds, M. A. (2019). In there a gender difference in the response to competitive settings. In P. Downward, B. Frick, B. Humphreys, T. Pawlowski, J. Ruseski, & B. P. Soebbing (Eds.), The Sage handbook of sports economics (pp. 516–524). Sage Publications.

- Leite, W., & Diniz da Silva, C. (2023). Can socio-cultural predictors help explain the home advantage gap in European men’s and women’s football? Soccer and Society, 24(5), 725–736. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2022.2116012

- Lopez, T. (2023, January 29). Medalist team in a low-budget league. La Vanguardia. https://www.lavanguardia.com/deportes/20230129/8716788/balonmano-mundial-hispanos-seleccion-medallista-liga-asobal-mileurista.html

- Matos, R., Amaro, N., & Pollard, R. (2020). How best to quantify home advantage in team sports: An investigation involving male senior handball leagues in Portugal and Spain. RICYDE, Revista Internacional de Ciencias del Deporte, 16(59), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.5232/ricyde2020.05902

- Meier, H. E., Jetzke, M., & Terwolbeck, A. (2023). Industry hierarchy in team sport industries, team tactics and competitive advantage: The empty goal option in league handball. European Sport Management Quarterly, 23(5), 1587–1609. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2022.2048045

- Meletakos, P., Chatzicharistos, D., Apostolidis, N., Manasis, V., & Bayios, I. (2016). Foreign players and competitive balance in Greek basketball and handball championships. Sport Management Review, 19(4), 391–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2015.09.002

- Mondal, S. (2023). She kicks: The state of competitive balance in the top five women’s football leagues in Europe. Journal of Global Sport Management, 8(1), 432–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/24704067.2021.1875629

- Owen, P. D., & Owen, C. A. (2022). Simulation evidence on Herfindahl–Hirschman measures of competitive balance in professional sports leagues. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 73(2), 285–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/01605682.2020.1835449

- Owen, P. D., Ryan, M., & Weatherston, C. R. (2007). Measuring competitive balance in professional team sports using the Herfindahl–Hirschman index. Review of Industrial Organization, 31(4), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-008-9157-0

- Pawlowski, T., Breuer, C., & Hovemann, A. (2010). Top clubs’ performance and the competitive situation in European domestic football competitions. Journal of Sports Economics, 11(2), 186–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002510363100

- Pawlowski, T., & Nalbantis, G. (2019). Competitive balance: Measurement and relevance. In P. Downward, B. Frick, B. Humphreys, T. Pawlowski, J. Ruseski, & B. P. Soebbing (Eds.), The Sage handbook of sports economics (pp. 154–162). Sage Publications.

- Pérez-Chao, E. A., Portes, R., Ribas, C., Lorenzo, A., Leicht, A., & Gómez, M. A. (2024). Impact of spectators, league and team ability on home advantage in professional European basketball. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 131(1), 177–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/00315125231215710

- Plumley, D., Mondal, S., Wilson, R., & Ramchandani, G. (2023). Rising stars: Competitive balance in five Asian football leagues. Journal of Global Sport Management, 8(1), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/24704067.2020.1765700

- Plumley, D., Ramchandani, G., Mondal, S., & Wilson, R. (2022). Looking forward, glancing back; competitive balance and the EPL. Soccer and Society, 23(4–5), 466–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2022.2059855

- Pollard, R., & Gómez, M. A. (2014). Comparison of home advantage in men’s and women’s football leagues in Europe. European Journal of Sport Science, 14(Suppl. 1), S77–S83. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2011.651490

- Pollard, R., Prieto, J., & Gómez, M. A. (2017). Global differences in home advantage by country, sport and sex. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 17(4), 586–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2017.1372164

- Ramchandani, G., Plumley, D., Boyes, S., & Wilson, R. (2018). A longitudinal and comparative analysis of competitive balance in five European football leagues. Team Performance Management, 24(5–6), 265–282. https://doi.org/10.1108/TPM-09-2017-0055

- Ramchandani, G., Plumley, D., Davis, A., & Wilson, R. (2023a). A review of competitive balance in European football leagues before and after financial fair play regulations. Sustainability (Switzerland), 15(5), 4284. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054284

- Ramchandani, G., Plumley, D., Mondal, S., Millar, R., & Wilson, R. (2023b). You can look, but don’t touch’: Competitive balance and dominance in the UEFA Champions League. Soccer and Society, 24(4), 479–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2023.2194512

- Ramchandani, G., Plumley, D., Preston, H., & Wilson, R. (2019). Does size matter? An investigation of competitive balance in the English Premier League under different league sizes. Team Performance Management, 25(3–4), 162–175. https://doi.org/10.1108/TPM-10-2018-0064

- Ramchandani, G., & Wilson, D. (2014). Historical and contemporary trends in competitive balance in the Commonwealth Games. International Journal of Sport Science, 35, 75–88. http://www.cafyd.com/REVISTA/ojs/index.php/ricyde/article/viewFile/198/121

- Rottemberg, S. (1956). The baseball players’ labor market. Journal of Political Economy, 64(3), 242–258. https://doi.org/10.1086/257790

- Saavedra, J. M. (2018). Handball research: State of the art. Journal of Human Kinetics, 63(1), 5–8. https://doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2018-0001

- Scelles, N. (2021). Policy, political and economic determinants of the evolution of competitive balance in the FIFA women’s football World Cups. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 13(2), 281–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2021.1898445

- Scelles, N., & François, A. (2021). Does a country’s income inequality affect its citizens’ quest for equality in leisure? Evidence from European men’s football. Economics and Business Letters, 10(2), 133–139. https://doi.org/10.17811/ebl.10.2.2021.133-139

- Scelles, N., François, A., & Dermit-Richard, N. (2022). Determinants of competitive balance across countries: Insights from European men’s football first tiers, 2006–2018. Managing Sport and Leisure, 27(3), 267–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1784036

- Scelles, N., François, A., & Valenti, M. (2024). Impact of the UEFA Nations League on competitive balance, competitive intensity, and fairness in European men’s national team football. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2024.2323012

- Schmidt, M. B., & Berri, D. J. (2003). On the evolution of competitive balance: The impact of an increasing global search. Economic Inquiry, 41(4), 692–704. https://doi.org/10.1093/ei/cbg037

- Serrano, R., Acero, I., Farquhar, S., & Espitia Escuer, M. A. (2023). Financial fair play and competitive balance in European football: A long term perspective. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 13(1), 74–92. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-05-2021-0060

- Sloane, P. (2006). The European model of sport. In W. Andreff & S. Szymanski (Eds.), Handbook on the economics of sport (pp. 299–303). Edward Elgar.

- Statista. (2023, February 7). Key figures on handball participation worldwide. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1364943/handball-participation-key-figures/

- Treber, J., Levy, R., & Matheson, V. A. (2013). Gender differences in competitive balance in intercollegiate basketball. In E. M. Leeds & M. A. Leeds (Eds.), Handbook on the economics of women in sports (pp. 251–268). Edward Elgar.

- Truyens, J., De Bosscher, V., & Heyndels, B. (2016). Competitive balance in athletics. Managing Sport and Leisure, 21(1), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2016.1169213

- Valenti, M., Peng, Q., & Rocha, C. (2021). Integration between women’s and men’s football clubs: A comparison between Brazil, China and Italy. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 13(2), 321–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2021.1903967

- Valenti, M., Scelles, N., & Morrow, S. (2023). The impact of ‘super clubs’ on uncertainty of outcome in the UEFA women’s champions league. Soccer & Society, 24(4), 509–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2023.2194514

- Valenti, M., Scelles, N., & Morrow, S. (2024). The determinants of stadium attendance in elite women’s football: Evidence from the FA Women’s Super League. European Sport Management Quarterly, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2024.2343485

- van der Burg, T. (2023). Competitive balance and demand for European men’s football: A review of the literature. Managing Sport and Leisure, https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2023.2206815

- Wagner, H., Finkenzeller, T., Würth, S., & Von Duvillard, S. P. (2014). Individual and team performance in team-handball: A review. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 13, 808–816.

- Williams, L. V., Liu, C., Dixon, L., & Gerrard, H. (2021). How well do Elo-based ratings predict professional tennis matches? Journal of Quantitative Analysis of Sports, 17(2), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1515/jqas-2019-0110

- Zambom-Ferraresi, F., García-Cebrián, L. I., & Lera-López, F. (2018). Competitive balance in male and female leagues: Approximation to the Spanish case. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 18, 1323–1329. https://doi.org/10.7752/jpes.2018.s3196

- Zheng, J., Dickson, G., Oh, T., & De Bosscher, V. (2019). Competitive balance and medal distributions at the Summer Olympic Games 1992–2016: Overall and gender-specific analyses. Managing Sport and Leisure, 24(1–3), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2019.1583076

Annex

Table A1. Shapiro–Wilk test of normality.