Abstract

Within the measurement of learning gain, there has been significant focus on how an assessment of student engagement should play a key role. This article highlights how one of the core vehicles for measuring student engagement, the UK Engagement Survey, contains some additional, direct metrics that go beyond engagement itself that can make a significant contribution. Specifically, metrics assessing how students spend their time and how this impacts on skills provide clear insight on how institutions can help students participate in activities which are likely to have most impact on how they develop.

Keywords:

In this piece, we put forward the case for the UK Engagement Survey (UKES) to be adopted as a principal tool for providing a comprehensive measure of Learning Gain. Specifically, we highlight how moving beyond a narrow focus on student engagement with academic studies, to incorporate wider elements that are included in UKES but not generally well known, can provide rich evidence of immediate value to the sector to help identify how learning gain can be maximised.

The Higher Education Academy’s UK Engagement Survey (UKES)Footnote 1 is widely recognised as the only major undergraduate survey in UK higher education that comprehensively measures students’ perceptions of engagement with their studies. The core, compulsory items focus on ‘those educational activities known to contribute to effective learning’ (Buckley, Citation2015, p. 3), and are poised to play a key role in the measurement of learning gain, having been included in the national pilot projects currently taking place.Footnote 2

HEFCE’s definition of Learning Gain is wide-ranging: ‘The improvement in knowledge, skills, work-readiness and personal development made by students during higher education’ (HEFCE, Citation2015). However, by focussing attention and interest on the measures within UKES which measure student engagement with their academic studies, we risk overlooking a valuable source of data which measures other dimensions of learning gain.

We will therefore draw attention to additional elements included within UKES, specifically self-reported skills development and the amount of time spent on a range of non-study activities, which provide evidence of perceived learning gain as defined by HEFCE. Analysis of this data and the links between them can help to identify specific interventions which might enhance student learning gain.

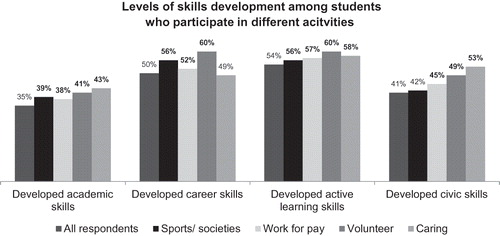

The 2016 UKES data illustrate the types of statistical links that such complementary datasets can reveal. As the Figure showsFootnote 3 , students across the whole survey report different levels of development of the various skills factors – academic skills, career skills, active learning skills and civic skills. However, by comparing scores among the whole sample, with students who have taken part in particular types of non-study activity, we can see that in most cases, students who have taken part in such activity report significantly higher levels of skills development.

Figure 1. Levels of skills development among students who participate in different acitvities.

In the context of learning gain, these results are valuable, in that they represent clear evidence of students’ perceptions of distance travelled in terms of skills, as well as highlighting the different roles played by different non-academic activities in potentially contributing to this.

With reference to one non-academic activity in particular, the data is pertinent to the debate around the benefits and necessity of finding paid employment while at university. While not suggesting that students’ skills do not benefit from time in employment, the results imply that the benefits associated with working for pay may be less significant than for other activities, such as volunteering or caring. These findings are supported by comparable findings in the 2016 HEPI-HEA Student Academic Experience Survey, which highlights that students who spent significant amounts of time in paid employment do not believe that they are learning as much as students who spend a small amount of time in this way (Neves & Hillman, Citation2017).

The issue of how students spend their time, and how HEIs can help to create the right opportunities for their students, is a complex one which requires detailed consideration. However, by providing evidence of skills gain, UKES and other data such as the Student Academic Experience survey can play a valuable role.

Learning gain pilots are in the early stages, and we look forward to these projects producing a range of rich and impactful findings not only on how learning gain can be measured, but also how the factors that support high levels of learning gain can be identified. This article highlights, however, that there is already information available in the shape of UKES, specifically student perceptions of skills development and how they spend their time, which, as well as helping to shape robust measurement, can contribute strongly to current and relevant debates around how learning gain can be improved.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Developed under license from the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) in the U.S. Copyright 2017, The Trustees of Indiana University.

3 Based on data analysis conducted by QA Research, March 2017.

References

- Buckley, A. (2015). UKES – students’ perceptions of skills development . York : Higher Education Academy.

- HEFCE . (2015). £4 million awarded to 12 projects to pilot measures of learning gain . Retrieved from http://www.hefce.ac.uk/news/newsarchive/2015/Name,105306,en.html

- Neves, J. , & Hillman, N. (2017). HEPI / HEA 2017 student academic experience survey, 2017 . York : Higher Education Academy.