ABSTRACT

Service-learning is identified as a high-impact teaching practice as it aids the development of business knowledge, human skills and civic responsibility amongst students. In spite of the benefits of service-learning, there are few studies that indicate the relational competencies of faculty members used to facilitate service-learning. This study shows how four relational competencies associated with relational pedagogy: care, interpersonal communication, an attentive presence and trust, facilitated service-learning amongst undergraduate students. Data for this study were drawn from personal reflections of teacher-student interactions during a service-learning course in change management. Findings show that although the demonstration of relational competencies associated with relational pedagogy created a conducive learning space that enabled students to gain practical knowledge, not all students in the study welcomed this approach. Based on the findings of this study, this article provides suggestions to educators in higher education engaged in service-learning and directions for further research.

Introduction

Service-learning, amongst several teaching practices, has been identified as a high-impact teaching practice that aids the development of business knowledge, human skills and civic responsibility amongst students (Blewitt, Parsons, & Shane, Citation2018; Bringle, Citation2017). Given the benefits, scholars have proposed different techniques to facilitate service-learning, including a focus on establishing clear procedures, using reflection and creating multiple contexts to apply service-learning (Celio, Durlak, & Dymnicki, Citation2011; Molee, Henry, Sessa, & Mckinney-Prupis, Citation2011; Yorio & Ye, Citation2012). What remains underresearched are faculty members’ relational competencies used to create a supportive learning environment that encourages students to engage in service-learning and succeed in their studies.

Relational competences of teachers are recognised by scholars as core factors to the success of service-learning (Conville & Kinnell, Citation2010; Jettner, Pelco, & Elliott, Citation2017). Relational competence is the ability of the teacher to develop a supportive teacher-student relationship through interactions with the individual student as a unique being; and consequently the teacher adapts his or her own actions to motivate students to learn without abandoning the leadership role, responsibility and authenticity of being the teacher (Jensen, Skibsted, & Christensen, Citation2015). Aspelin (Citation2012) and Jensen et al. (Citation2015) argue that the relational competence of educators generates better student achievements in the learning process than the classroom management and subject knowledge competence of educators. Therefore, putting a supportive teacher-student relationship at the heart of service-learning would be beneficial for students (Beran & Lubin, Citation2012). Interestingly, there is more emphasis on faculty engaging in research than teaching students through relationships, as seen by the importance of research qualifications, rather than teaching effectiveness, in faculty promotion and tenureship (Yürekli Kaynardağ, Citation2019). A focus on research output can deter a positive teacher-student relationship that improves the quality of learning. Noting that the quality of teacher-student relationship affects the personal, social and academic competences of students (Jensen et al., Citation2015), scholars need to consider the relational competencies in teacher-student relationship that can facilitate service-learning.

In the search for understanding relational competences, this study turns to the works of Aspelin (Citation2017, Citation2012), Ljungblad (Citation2019) and Bingham and Sidorkin (Citation2004) on relational pedagogy and its associated teaching practices that aid the development of relational competences in teachers. In this reflective paper, I present my personal experiences in applying the principles and practices associated with relational pedagogy. In addition, I provide illustrations on how I demonstrated relational competence when facilitating service-learning in a change management course for undergraduate students. Further discussions on my reflections indicate the challenges encountered in the process. In this article, I first provide an overview of service-learning and relational pedagogy. Then, I discuss relational competencies associated with relational pedagogy and how I applied four relational competencies: care, interpersonal communication, an attentive presence and trust. Discussion on the implications of employing relational pedagogy and its associated competencies in a service-learning course is presented in the penultimate section of the paper.

Service-learning: conceptualisation, core components and impact

Service-learning is a form of experiential learning that enables students to gain practical experience of real-world issues related to course content through hands-on experience, personal reflection, community service and development (Hickmon, Citation2015; Kenworthy-U’Ren, Citation1999; Stanton & Giles, Citation2017; Wang & Calvano, Citation2018). It differs from other forms of experiential learning such as cooperative education, internships, gaming simulations, structured exercises, case studies and role-play (Gallagher, Citation2011; Kenworthy, Citation2010; Leigh & Kenworthy, Citation2018). While work-integrated learning, such as internships and cooperative education, provide valuable work experience for students, the focus of such practices is to benefit the students without much emphasis on meeting the needs of community organisations (Gallagher, Citation2011). The differentiation of service-learning is in the degree of emphasis on the server (provider) and the served (recipient), with a focus on students’ learning and community service (Furco, Citation1996). The conceptual definition of service-learning emphasises creating value with the provision of ‘real service, not academic, not made up, not superficial, not tangential’ (Stanton, Cruz, & Giles, Citation1996, p. 67). The value created should be mutually beneficial to both students and community organisations engaged in the learning process in ways that develop the learning experience of students and meet human and community needs in the society (Bringle, Citation2017; Celio et al., Citation2011; Cooper, Citation2014; Kropp, Arrington, & Shankar, Citation2015). On this basis, four predominant aspects are advocated as fundamental components of service-learning: (1) integration of course content with service to the community, (2) students engaging in reflection, (3) students demonstrating civic responsibility, and (4) reciprocity (Beatty, Citation2010; Bringle, Citation2017; Brower, Citation2011; Godfrey, Illes, & Berry, Citation2005; Kenworthy-U’Ren, Citation1999).

The educational approach of service-learning includes the design of course content to reflect the learning outcomes of an academic course and meet the desired goals of community organisations (Brower, Citation2011; Godfrey et al., Citation2005). It goes beyond the traditional didactic approach of precisely providing theoretical concepts to students to making explicit connections amongst the course content, learning objectives and service to communities (Celio et al., Citation2011; Strage, Citation2000). As Brower (Citation2011) argues, the teaching practice of service-learning is not only linking course content to community service but also integrating real-work course projects in the learning process so that students provide professional and valuable service to communities.

The reflection component of service-learning facilitates the connection of theoretical concepts and actual practice (Kenworthy-U’Ren, Citation1999; Molee et al., Citation2011). It also helps to indicate the value of service-learning process and how it has improved students’ knowledge of their individual identities, perspectives, and understandings of the social and business world (Ash, Clayton, & Atkinson, Citation2005; Godfrey et al., Citation2005). The inclusion of civic responsibility as a component of service-learning in management education is consistent with the need for students to engage more in citizenship behaviour in addition to developing a profit-oriented perspective (Godfrey, Citation1999). Students take on the responsibility of understanding the needs and expectations of community organisations, creating approaches to meet community needs and initiating opportunities to actively engage and be committed to the development of the wider society (Gallagher, Citation2011). The reciprocity component implies the mutual benefit of the server and the served engaged in service-learning (Brower, Citation2011; Kenworthy-U’Ren, Citation1999). With reciprocal benefits, students gain personal real-world experiences, and the community organisations benefit from enhanced service delivery and generation of new ideas (Celio et al., Citation2011; Cyr & Kemp, Citation2018).

The reciprocal benefit of offering practical experiences to students in a real-world context that resolves business and social issues makes service-learning a high-impact teaching practice (Blewitt et al., Citation2018; Bringle, Citation2017; Cooper, Citation2014). Students gain theoretical knowledge about the subject-matter and hands-on experience in communities (Kenworthy-U’Ren, Citation1999). It also offers a practical approach for students to enhance their understandings of complex problems (Batchelder & Root, Citation1994; Cooper, Citation2014; Salimbene, Buono, LaFrage, & Nurick, Citation2005), and develop their confidence, self-efficacy (Brower, Citation2011; Giles & Eyler, Citation1994), and collaborative and leadership skills (Kropp et al., Citation2015; Leigh & Kenworthy, Citation2018; Poon, Chan, & Zhou, Citation2011). Values toward ethical conduct, active citizenship and volunteerism are additional benefits of service-learning to students (Eyler, Giles, Stenson, & Gray, Citation2001; Poon et al., Citation2011). For community organisations engaged in service-learning, Eyler et al.’s (Citation2001) and Vizenor, Souza, and Ertmer’s (Citation2017) studies noted that organisations were satisfied with service-learning and gained useful service from students. Service-learning’s value for community organisations includes financial resources, new ideas, new connections, access to grants, and improved products and services (Blouin & Perry, Citation2009; Cyr & Kemp, Citation2018).

Contrary, several studies have identified some challenging issues with service-learning (Blouin & Perry, Citation2009; Conville & Kinnell, Citation2010; Vernon & Foster, Citation2002). Within the context of teaching, ill-prepared and less committed students can negatively affect the desired outcomes of service-learning for students and community organisations (Conville & Kinnell, Citation2010; Ferrari & Worrall, Citation2000; Noley, Citation1977; Vernon & Foster, Citation2002). Inadequate preparation of students leads to poor learning outcomes for students. In addition, Conville and Kinnell (Citation2010) argue that ill-prepared students cannot adequately serve community organisations, which leads to a distortion of long-term partnerships between universities and communities. Based on the demands in delivering the four components of service-learning and its intended significant contributions to developing students and building communities, emphasis on the actual delivering process requires more attention. Thus, prior research advocates that faculty members adopt multiple teaching roles – including facilitator, coach, subject-expert and evaluator – when facilitating this experiential learning process (Conville & Kinnell, Citation2010; Kolb, Kolb, Passarelli, & Sharma, Citation2014). While each teaching role is necessary in the delivering of service-learning, creating a personal and supportive teacher-student relationship remains a significant aspect. This relationship can foster students’ active engagement in the subject-matter and enable students to offer valuable contributions to community organisations.

Interestingly there is limited research that demonstrates how instructors create personal and supportive teacher-student relationship to encourage the active engagement of students in service-learning. Existing research on the facilitation of service-learning emphasises on logistics and operational issues such as course design and the sequencing of activities (Aday, Weeks, Sherman, Marty, & Silverstein, Citation2015; Flannery & Pragman, Citation2010; Kenworthy, Citation2010; Motoike, Citation2017; Roman, Citation2015; Snell, Chan, Ma, & Chan, Citation2015). Other studies present an analyses on the reflection component in service-learning (Ash et al., Citation2005; Eyler & Giles, Citation1999; Gelmon, Holland, Driscoll, Spring, & Kerrigan, Citation2001) and approaches to institutionalising service-learning in higher education (Bennett, Sunderland, Bartleet, & Power, Citation2016; Stater & Fotheringham, Citation2009). Given the impact of service-learning on students, communities and universities – and the need for a supportive teacher-student relationship – this paper presents the principles and teaching practices associated with relational pedagogy (see Aspelin, Citation2017; Bingham & Sidorkin, Citation2004; Ljungblad, Citation2019) as a guide to developing relational competencies that can facilitate service-learning in higher education.

Relational pedagogy and relational competencies

Relational pedagogy is based on the philosophy that teaching, learning and education is a relational process (Aspelin, Citation2014; Ljungblad, Citation2019; Pearce & Down, Citation2011). It is based on an anthropological notion that human beings exist in relationships and that the individual is ‘an aspect or a by-product of relationships’ (Aspelin, Citation2014, p. 235). Individuals do not exist separately but exist in relation to someone or something, thus becoming part of a relational process (Aspelin, Citation2014; Murphy & Brown, Citation2012). It is within this relational context, when human beings meet and interact, that the acquisition of knowledge and learning occurs (Bingham & Sidorkin, Citation2004; Pijanowski, Citation2004). Thus, the practices of relational pedagogy emphasise on personal encounters – interhuman relations – between educators and students (Bingham & Sidorkin, Citation2004; Noddings, Citation1984).

It shifts the focus of teaching from student-centred and teacher-centred to a focus on teacher-student relationship, such that the relationship between both entities is ontologically more important than the single entities in the learning process (Aspelin, Citation2014; Biesta, Citation2004; Ljungblad, Citation2019; Pijanowski, Citation2004). Proponents of relational pedagogy (see Aspelin, Citation2014; Ljungblad, Citation2019; Pearce & Down, Citation2011) develop further understanding of the relational approach to teaching from the works of Buber (Citation1970), Noddings (Citation1984) and Bingham and Sidorkin (Citation2004). For instance, building on the works of Buber (Citation1970), studies by Aspelin (Citation2014) and Aspelin and Jonsson (Citation2019) advocate that the learning process shifts from the teacher-centred and student-centred approach to a more relational-interaction approach built on authentic dialogue. The notion is that the teacher and the student should form I and Thou relations based on acceptance, inclusion and trust (see Buber, Citation1970; Hillard, Citation1973; Morgan & Guilherme, Citation2012). This relational approach also highlights Noddings’s (Citation1984) caring teacher-student relationship, where the teacher’s effort focusses on valuing and appreciating students’ needs and learning about students’ interests and desires.

This relatively new approach in educational theory acknowledges the individuality and differences of learners (Bingham & Sidorkin, Citation2004; Ljungblad, Citation2019). It posits students more as human beings and not as academic clients (Thayer-Bacon, Citation2004). In the context of Buber’s (Citation1970) analysis, students are recognised as persons and, not just a means to an end. Students are not merely objects used to demonstrate the subject-knowledge of educators. Thus, the focus is on creating a positive teacher-student relationship that impacts students’ learning outcomes and enhances the experiences of students with teachers, students with their peers and with society at large (Bingham & Sidorkin, Citation2004). In relational pedagogical practices, the development of teacher-student relations largely depends on the relational proficiencies of teachers (Aspelin, Citation2012; Ljungblad, Citation2019). These relational proficiencies include the ability to create and use relational space to develop a trustful and respectful teacher-student relationship. It also facilitates student accessibility, participation and engagement in the learning process (Ljungblad, Citation2019). The relational space is not confined to classroom interactions but other in-between spaces where teachers directly meet with students, such as impromptu and unscheduled visits outside of office hours (Pearce & Down, Citation2011).

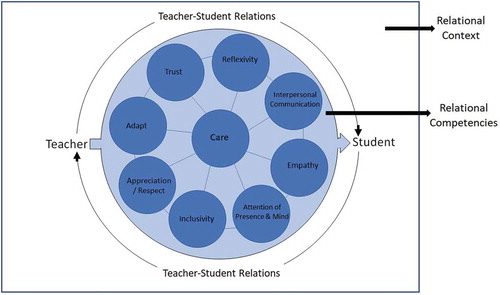

Key attributes to demonstrate relational proficiencies of educators and develop relational space include care, empathy, appreciation, respect, trust, interpersonal communication, an attentive presence, creativity, flexibility, constructive sense of humour and taking responsibility as an educator (Aspelin, Citation2014; Aspelin & Jonsson, Citation2019; Brownlee & Berthelsen, Citation2006; Crownover & Jones, Citation2018; Jensen et al., Citation2015; Noddings, Citation1984; Reeves & Le Mare, Citation2017; Thayer-Bacon, Citation2004). It also includes inclusivity that recognises the uniqueness and diversity of students in higher education (Ljungblad, Citation2019). Gleaning from the literature on relational pedagogy (Aspelin & Jonsson, Citation2019; Bingham & Sidorkin, Citation2004; Jensen et al., Citation2015; Ljungblad, Citation2019; Vidmar & Kerman, Citation2016), this study has developed a conceptual framework to illustrate the interrelated sub-elements of teachers’ relational competencies. The sub-elements are not inclusive of all the elements of the relational competencies of teachers. Nonetheless, the sub-elements presented act as analytical categories to support a positive teacher-student relationship.

The model in illustrates the interrelated nature of the elements of relational competency within the context of teacher-student relationship. The teacher-student relational context is the relational space in which both entities interact and learn (Biesta, Citation2004; Jensen et al., Citation2015). The element of care is the teacher’s ability to show concern and interest in the development of students as human beings (Margonis, Citation2004; Thayer-Bacon, Citation2004). It involves the ability to listen receptively to students and continually observe their behavioural expressions during dialogic interactions with the teacher and their peers (Nel Noddings, Citation2012). In response to the expressed needs and interests of the students, the teacher acts positively to channel the same needs towards the attainment of educational goals. As Thayer-Bacon (Citation2004) argues, the demonstration of care is not manipulative or harmful but is instead good and supportive. The interrelated element of interpersonal communication involves interactions with students to provide clarity of meanings explicitly. Information is presented in plain terminology that the students can easily understand without getting confused and frustrated (Aspelin & Jonsson, Citation2019; Pearce & Down, Citation2011). As Aspelin and Jonsson (Citation2019) noted, teachers, through both verbal and nonverbal communicative competence, make themselves understood while demonstrating to their students that they understand them.

Attention and presence of mind require the awareness of self as a responsible educator and the mindfulness of students as social beings in the process of becoming knowers (Romano, Citation2004; Thayer-Bacon, Citation2004). Within this element, teachers show presence of mind, calm their thoughts and emotions, remain attentive and sensitive (Jensen et al., Citation2015). As Jensen et al. (Citation2015) argue, an attentive presence enables teachers to respond to students’ needs and involve students in the learning process. The element of respect and appreciation implies showing regard for oneself (as a teacher) and respect for each student. The teacher remains authentic to self while understanding and acknowledging the identities, perspectives, experiences and interests of students. The informed awareness of each student leads to a change of perspective where the teacher demonstrates competency of being adaptable by channelling the student’s needs to the learning outcomes. The element of trust is demonstrated by being confident, open and receptive to students’ ability to engage in the learning process (Aspelin & Jonsson, Citation2019; Bingham & Sidorkin, Citation2004). Other aspects of the model – such as ongoing reflective practice, empathy, and inclusivity – are interrelated within the sub-elements.

These relational competencies are essential for educators to understand each student’s uniqueness and facilitate student engagement with the service-learning process. Interestingly, few studies provide details on developing and demonstrating relational competencies of educators (Aspelin & Jonsson, Citation2019; Jensen et al., Citation2015). While there is research on classroom management and subject-specific teaching competencies, ‘the same cannot be said about relational competence’ (Jensen et al., Citation2015, p. 203). In the next section, I present my reflections on the literature on relational pedagogy and how I applied four relational competencies associated with relational pedagogy while facilitating service-learning in a change management course for undergraduates. These competencies – care, interpersonal communication, an attentive presence and trust – though presented in this study as distinct terms, should be understood as analytical categories that are interrelated and linked to other elements of the model. Specifically, this paper responds to two questions:

How does the literature on relational pedagogy describe these four relational competencies?

How did I apply these four relational competencies in delivering service-learning in management education?

Methods

This study used a case study methodology to explore the application of relational competencies in a change management course. Data used in this study were generated through primary and secondary research. Primary data used in this study was drawn from personal reflections on a service-learning course for students in their fourth year of management studies in a large public undergraduate university in Western Canada. Research-diary records on my interactions with students, participant observation, and document analysis of students’ written reflections were used to generate findings. A total of 30 students enrolled in the course on change management and worked with three different community organisations. All the students were registered in the bachelor of commerce program with a major in management. There were more male students (63%) than females (37%). Most of the students were between 20–26 years old (70%).

Secondary data on relational competencies were drawn from the literature on relational pedagogy. The study reviewed conceptual and empirical articles on relational pedagogy. Five databases were used to search for relevant peer-reviewed articles, including ProQuest, EBSCO, Science Direct, Emerald Insights and Google Scholar. Key search words used include relational pedagogy, relational competencies and teaching method. Academic journals that presented relevant data for analysis include Journal of Thought, Education Inquiry, International Journal of Inclusive Education, and Teacher Development: An International Journal of Teachers’ Professional Development, and Australian Educational Researcher. While the review mainly focused on academic articles, it also included a book that was considered relevant and largely cited: Bingham and Sidorkin (Citation2004) No Education without Relation. A report on the main findings is presented herein. First, this article presents an overview of the business course and students’ subsequent engagement with community partners. Then, it presents an explanation of four relational competencies and my reflections on how these competencies were applied when delivering service-learning.

Service-learning in a change management course

Service-learning and its four related components were incorporated in a change management course offered to 30 students in the 2019 fall term. The course was designed to enable each student to understand and apply change management theories in an organisational context, develop change implementation plans with further consideration of ethical business principles and provide options for assessing and managing resistance. The course content was designed to reflect academic learning objectives. It included key topics on theories of change; internal and external drivers for change; the role of a change agent in private, public and non-governmental organisations; and ethical business principles for change management. Following the reflective and reciprocal components of service-learning, I created two individual reflective assessments. The first assessment, scheduled midway through the course, provided each student with the opportunity to (1) reflect on their understanding on the topics on organisational change management, (2) indicate how they will apply what they have learned on organisational change outside academia, and (3) state specific goals they aim to achieve when delivering the service component of the course to community organisations. The second reflective assessment was set to be completed by each student at the end of the course and was designed to assess the specific value each student provided to community organisations and what value they gained from engaging with the same community organisations. This reflective assessment requires deep reflective thinking on what students learned about real organisational issues and how they would respond if offered a job position as a change analyst in the same or a similar organisation.

In line with the project-based service-learning approach, a group field assignment was designed to enable students, through group work, to collaboratively design a change management plan to resolve change management issues presented by community organisations. Students were expected to include measures to evaluate and reduce challenges against change initiatives in community organisations. Then, I selected case studies on change management from different scholarly journals and media reports on both national and global issues that triggered changes within organisations. The selection of these cases and reports was to facilitate students’ initial understanding of changes within the workforce and its impact on society. Secondly, the articles were meant to stimulate discussions on suitable approaches to manage change and foster a relational space amongst students and their peers, as well as students and the instructor (myself). Lastly, the cases were intended to prepare students for the actual challenge of designing a change management plan for community organisations.

Next, in collaboration with administrators from the office of experiential learning and students’ placement, we purposively selected community organisations to partner with to enhance the learning experiences of students in the course, while also advancing the business or social endeavours of the community organisations. The selection of community organisations were based on four criteria: (1) the need for support with an ongoing or proposed change within their organisations, (2) the ability to provide easy access to company information, (3) the availability to work with students and myself in providing valuable service, and (4) the availability to attend three in-class sessions to hold discussions with students during term time formally.

In the first in-class session, agencies of community organisations were expected to present their change management needs to 30 students. The second in-class session provided an opportunity for further interactions with the specific group of students assigned to their change management projects. The last session provided opportunities for students to present their change management reports to the community partners. Based on these set criteria, we selected three community organisations – two not-for-profit firms and one private firm – to engage in the learning process. Two organisations operated in the health and aviation sector, and one as a cooperative civil society.

Delivering service-learning through relational competencies

The implementation stage of service-learning is a critical phase that ‘requires fearless facilitation and artful sequencing of topic and activities’ (Motoike, Citation2017, p. 137). Scholars argue that the process involves student preparation, which entails the teachers actively motivating students to understand the importance and benefits of service-learning, setting guidelines to meet deadlines, discussing requirements of students (Conville & Kinnell, Citation2010) and communicating with participating organisations. As Motoike (Citation2017) noted, the implementation phase moves from a sequence of lower to higher risk and presenting concrete to abstract information. Then, instructors are expected to guide students to explore abstract and complex aspects of the course content and community engagement to improve the learning process. Students, through the guidance of instructors, are expected to learn theoretical concepts. They are also expected to provide resources including intellectual knowledge, skill or practical work that demonstrates their understanding of course content and civic responsibility to help resolve community-identified issues (Brower, Citation2011). The next section presents self-reflections on the descriptions of relational competences in the literature on relational pedagogy and my demonstration of four relational competencies while delivering service-learning. Discussed herein includes relational competencies of care, interpersonal communication, an attentive presence and trust.

Situated practice of care

Crownover and Jones (Citation2018) and Ljungblad’s (Citation2019) studies indicate that to demonstrate the situated practice of care, instructors need to create a relational space to enable teacher-student interactions. It is not just a space confined to the physical classroom, but also the ‘in-between’, where students and teachers interact (Biesta, Citation2004, p. 15). This relational space requires faculty members to approach students as human beings – distinct individuals – constantly in the process of becoming. In the situated practice of care, thoughtful consideration is given to the current position of students, with an emphasis on the opportunities for them to emerge as responsible adults in the course of the relationship (Noddings, Citation1984). As Noddings (Citation1984) argues, the teacher bears the responsibility of enhancing students’ learning experiences by demonstrating oneself as one-caring. This requires adequate time to understand the historical and cultural background of each student as well as his or her unique nature when facilitating service-learning.

As an educator engaged in service-learning, I face diverse students from different sociocultural backgrounds, skilled or unskilled, with some students having more or less prior work experience, while others confronted with family responsibilities and even physical disabilities. The demonstration of care by understanding each student’s capabilities and individuality is paramount to facilitate the provision of an equal learning experience for all students. The first step to demonstrate genuine care and interest is to make attempts to understand each student and encourage students’ voices in sharing their identities. This is quite a challenging feat to accomplish amongst 30 undergraduate students. I discovered that some students are generally extroverts and open to discussing their individualities. Other students are reluctant to easily and openly express their identities because they are unsure about their individualities. Some students are also not excited about sharing their identities. Other students instead disguise their identities for several reasons related to career achievements, setbacks, family issues and health issues.

Knowing that an understanding of the individuality and capability of each student is paramount in the demonstration of relational pedagogy, as it aids in the construction of meanings shared during class discussions and the level of support provided to each student, I made considerable efforts to share my own identity. This was done in anticipation that sharing my identity would enable students to do the same. Discussions started with my historical trajectory of obtaining an undergraduate degree in media studies and two postgraduate degrees in business administration, to facilitating business management studies in institutes of higher learning. Other aspects of my family life and my interest in helping resolve management issues in organisations were shared in a relaxed and conversational manner. Then I informed students on how I have embraced service-learning as a means to develop students’ practical understanding of theoretical concepts in business management. I also explained how the same learning process contributes to the advancement of society through engagement with community organisations. I intentionally disclosed certain aspects of my individuality at the start of the course in anticipation that it would stimulate a reciprocal response from students during cooperative groups in-class sessions.

Similar to the concept of personal relationship, I observed that being open to discuss my upbringing and approach to service-learning in management education encouraged students to be comfortable in sharing their identities and their reasons for studying change management. Within these first weeks of interactions with a focus on sharing the individualities of students and myself as well as our current academic positions, interests, and future goals, I came to understand the unique personalities, capabilities and goals of some students. An extract of my self-reflections presented below indicates how, in my situated practice of care, I learnt about the academic and family challenges students face and the career opportunities and restrictions they encountered. I also learned about their strong interests in other aspects of life and their keen desires to take up managerial positions regardless of their ages, yet with an anxious perspective to deal with managerial responsibilities and workers’ acceptance of their identities as young people.

Felix seems to be more focused on his laptop than keenly engaging in any discussion except when prompted. So I walked up close to him while maintaining direct eye contact to initiate a conversation. Further observations and discussions with him revealed his keen interest in hockey as a lead player in the games. Intense visual focus on the games during class times seem more important to him than topics on managing change. Steven, his friend, is a bit chatting and openly discusses his own plans to continue with a family business of farming. But, upon reflecting on his bodily expressions while sharing his plans, I determined that he did not seem pleased to take up that responsibility. It appears that his parents expect him to continue in managing the family business, thus resulting in his path towards attaining an undergraduate degree with a management major.

In my situated practice of care, I recognised that listening carefully to respond appropriately to their emotions, paying attention to their interactions with others, and keenly observing their bodily expressions are important to understand who they are and their present state. The demonstration of care through my vocal and bodily expressions is also important in creating a comfortable relational space for learning. I observed that the more I move away from the podium and sat close to students, showing genuine interest to understand each student, the more some students sought to gain my attention so I would engage in discussions with them. Interestingly, I discovered that a relationship context in which the teacher seeks prior knowledge of students by identifying Who they are, at the start of the service-learning process, stimulates most students’ interest in engaging in the learning process.

Other students showed less interest in sharing their identities and only offered a few statements about their future goals when asked. Subsequent reflections on their interactions and emotions after each class discussion enabled me to reflect on myself and question if my relational approach in discussing in groups had excluded these students or perhaps, they required a one-on-one discussion? Further self-reflection led to discussions with these students and introducing topics that may be of interest to them, including career, family and academic-focused matters. This initial discussions with these students to understand their individualities, though time-consuming, helped me to understand these students better and create a comfortable relational space for teacher-student interactions. However, while it improved student-teacher interactions with most students, four students were less engaged than others and were not receptive to my relational approach to teaching. It appeared that two of the four students were not accustomed to this teaching approach. The other two had enrolled in the course as a mandatory option to complete their degrees and not out of their own volition. Thus, they occasionally attended in-class sessions and remained less engaged. Nevertheless, I continued an ongoing situated practice of care. This ongoing process of care was also demonstrated during interpersonal communication with students and in positioning an attentive presence during service-learning.

Interpersonal communication

Empirical studies indicate that interpersonal communication is a core competency demonstrated in the practice of relational pedagogy (Aspelin & Jonsson, Citation2019; Pearce & Down, Citation2011). Biesta (Citation2004) argues that interpersonal communication is more about teacher-student participation and transformation while sharing meanings and knowledge. The demonstration of ongoing communicative competence is therefore required for a teacher to achieve adequate degree of attunement in teacher-student relationship such that emotions are channelled towards educational goals (Aspelin & Jonsson, Citation2019).

In this context, the aspect of giving each student a voice during interpersonal communication is emphasised (Brower, Citation2011; Ljungblad, Citation2019; Margonis, Citation2004). As Ljungblad (Citation2019) noted, each student’s voice is heard, listened to and used in response to the voices of others. Based on this understanding, I interacted formally and informally (friendly) with the students, discussing the learning outcomes, the expectations of service-learning, and the challenges and benefits of the learning process as a group. I also discussed with students the benefits of service-learning for the development of individual students and the specific change management needs of community organisations (Conville & Kinnell, Citation2010). The communication process was relational and ongoing throughout the implementation phase of service-learning. It is within this ongoing relational context of the interactions between students and myself on the different topics on change management, I observed that learning occurred. I observed that ongoing interpersonal communication is not only confined to face-to-face encounters as Ljungblad (Citation2019) noted, but is also achievable through other communication channels, such as official emails, telephone calls, text messages, and educational technology apps (Blackboard Learn, Socrative). Through these different communication channels, I learned how students could articulate their understandings of change management. For example, most students indicated theories of change, drivers for change and characteristics of a change agent as significant points they learned. Others shared important aspects of communication and transparency during an organisational change process:

The change agent is the person or people who lead the rest of those affected through the change. However, this isn’t a simple task. A change agent must be resilient, determined, and committed to implementing, and they must have strong communication skills in order to highlight the effects the change will have to those it will affect. (Steven)

So far during the class, one of the most important concepts to me has been the process of implementing change, and more specifically, the way employees are treated when managing change … If one doesn’t communicate the change properly, or is not transparent enough, it can be a cause of disillusioned staff. (Sharon)

These shared conversations, in plain language, demonstrate the students’ knowledge of the course. The findings indicate the value of sharing meaningful ideas and knowledge in clear and simple terms. This enabled me to observe the students’ transformation as they learned change management concepts. It also enabled me to assess their readiness to work with community organisations on change management projects.

Prior to having the students work with community organisations, I invited administrators from the experiential learning and students’ placement office to provide students with guidelines on conference calls, email etiquette and the university confidentiality agreement with community partners. Taking a relational teaching approach, I also offered students the opportunity to share their expectations for delivering the service-learning component to organisation partners. Students’ expectations ranged from ‘good communication process with community organisations’ to ‘providing a reasonable timeline to community organisations to implement proposed change’, ‘satisfying community partners’, ‘building a reputation for the university’ and ‘creating added value’ for themselves:

I think that the most important part will be communication. Communication is the key to change management … I believe that the timeline of the change will be very important; it needs to be a change that has a reasonable timeline, so our partners want to implement the proposed change. (Felix)

Hard work done by myself and my group would be complimented by satisfaction from XXXX [community partner], that we did a good job that they like. This is a goal of my own … because a change management process is only worthwhile if the client is happy with the results. If the client were not happy with the report, then we would feel as if we didn’t learn enough in the class or we didn’t work hard enough and apply the right material. (Kevin)

Interpersonal communication and ongoing discussions with students revealed their keen interests and expectations to offer valuable service to community organisations while developing competent skills required of practising change agents. These expectations from students were taken into consideration during the delivery of service-learning projects to community organisations.

An attentive presence

Demonstrating an attentive presence is significant in teaching as it enables faculty members to gain further understanding of students (Jensen et al., Citation2015; Margonis, Citation2004). Romano’s (Citation2004) studies indicates that the demonstration of an attentive presence requires educators to be observant of each student, make considerable attempts to be aware of the expressed emotions of students and be responsive to these emotions. It requires engaging with students, paying particular attention to their contributions and challenging them to explain further, narrate and share their learning experiences or knowledge gained through dialogue (Jensen et al., Citation2015). It also requires faculty members to be approachable and available to discuss rising issues. As noted in Margonis’s (Citation2004) study, a teacher’s attentive presence and subsequent interactions with students can influence the laziest, most resentful and least appreciative student to demonstrate a committed, courteous, enthusiastic and cooperative behaviour.

It was observable that as we progressed on the course, few students come ill-prepared to class, remained uninvolved, focussed on social media during learning sessions and became impatient with the duration of class times. Others from disadvantaged indigenous and international communities found it quite challenging to understand teaching practices in a Western context. My attentive presence in addition to interpersonal communication was vital in supporting the transformation of these students to becoming intellectually engaged citizens. A practical step used to demonstrate an attentive presence was situating myself in the position of each student. In addition, encouraging further discussion from such students to resolve the specific change management need of organisation partners, via telephone and face to face interactions during scheduled and non-scheduled work hours, helped to demonstrate an attentive presence. Demonstrating an attentive presence enabled me to offer support to students who were nervous about interacting with community organisations by reassuring them of their capabilities and knowledge they had developed in the change management course.

Offering timely responses also helped me demonstrate an attentive presence. To better achieve this, I often pose the question: If I were in the same position as an undergraduate in this learning context, what would I most prefer from an instructor? This question emanates from Romano (Citation2004) imaginative compassion of ‘feeling and seeing the world from the student’s point of view’ (p. 161). My response to this question in different situations and with different students led to one-on-one in-class sessions with uninvolved students, the introduction of practise activities to stimulate the interests of students on topics presented and prompt responses to emails on request to resolve subject-knowledge issues. It also led to the introduction of new teaching techniques midway through the course, such as recording audio of collaborative discussions amongst the students, community partners and myself. In addition, I offered formative assessments and feedback to students on group presentations before their final student presentations to organisation partners. I also adjusted assignment expectations to accommodate students’ needs and achieve the learning outcomes. For instance, my formative assessments of group presentations enabled students to express their findings and recommendations in a relaxed manner. The subsequent feedback on their presentations helped guide students in the design and delivery of their presentation slides for the final group presentation to community organisations. Also, I adjusted the final reflection assessment from a 1000-word limit to 1500-word limit based on students’ request and the learning objectives of the course. This enabled the students to express in more details what they had learned as change agents. This approach resonates with Aspelin’s (Citation2014) and Jensen et al.’s (Citation2015) ideologies of the teacher’s change of perspective and approach where the students’ needs, expectations and contributions are not only considered valid to facilitate their learning experiences but also transform the teaching process.

However, not all the students’ expectations were granted. For instance, the students requested to present their final group projects to only their assigned community organisations. In further discussion with students, I presented the rationale for creating the opportunity for each student group to present to the entire class as well as community organisations and myself (instructor). First, I calmly explained that it provided more learning opportunities for the audience (students, instructors and community organisations) to understand the feasibility of applying different change management theories and initiatives to resolve organisational change needs. Second, I explained that it presented opportunities for the audience to learn different presentation formats and skills to help advance our business and academic careers. Next, I clarified that it helped ensure fair grading/performance evaluations of each group, as students can easily attest to student groups that performed better than others. Lastly, I explained that it helped to get undergraduates accustomed to making presentations to a fairly larger audience than small groups, which is required from practising change agents. Most undergraduates came to understand the benefits of paying reasonable attention to their requests regarding group presentations as well as engaging in constructive dialogue during service-learning:

After the group presentations on Thursday, I took the time to reflect on comments fellow students raised about presenting to the community partners in front of classmates. I found listening to classmates’ presentations valuable in my learning and growth related to change management planning. It provided me with the opportunity to see how other people approached, interpreted and proposed solutions for the change and how it was similar and different from how our team did … I hope presenting in front of classmates continues, as I find the value it provides outweighs the fear people may have in presenting to fellow students. (Sandra)

Another thing I learned about myself is that I can present in front of larger groups that aren’t all my peers in class. This was a first for me, and I felt nervous about this before the presentation. Presenting in front of someone completely new is a challenging experience, but I learned that I am able to present professionally. (Kevin)

The above expressions from students indicate that my attentiveness in response to their needs and expectations was important to improve their learning experience. It was equally important for them to align their expectations to the overall benefit for students, educators, and community organisations.

Trust

In relational pedagogy, trust has been identified as a vital component of teacher-student relationship that enables students to accept information, advice or care from the teacher (Bingham & Sidorkin, Citation2004; Crownover & Jones, Citation2018). In addition, trust is acknowledged as a component of the relationship that enables the teacher to demonstrate confidence in the student’s ability to express their perceptions without fear of being discounted, alienated, embarrassed or belittled (Aspelin & Jonsson, Citation2019). In service-learning, the demonstration of trust extends beyond creating a safe relational space for open communication; it also entails the ability to allow a free flow of interaction amongst the students and teachers, students and community organisations, and students with their peers. The interactions with community organisations and their peers are often beyond the direct control of educators. Thus, it could lead to unpredictable events in which students are more knowledgeable about community organisations than the teacher or engage in further discussions with community organisations that could discredit the teaching practices of the teacher or bring disrepute on the standards of the university. On the contrary, it could also lead to great opportunities for students to become more conscious of who they are, the needs of community organisations and their contributions to the general society. Students’ discussions with community organisations could also contribute to building the reputation of faculty members as well as the university.

The preceding reflections on the potential benefits of trust indicate the importance of building a trustful teacher-student relationship during service-learning. Two approaches that enabled me to develop trustful teacher-student relationship were (1) being conversant about the subject-matter on change management and open to discovering new findings through research in this field of study and (2) sharing practical examples of personal experiences in delivering service-learning and change management processes in organisations. Regarding the subject-expert role, Kolb et al.’s (Citation2014) study indicates the need for faculty members to assist students in understanding and connecting their reflections to the subject-matter. In the context of delivering service-learning, practical examples of change management shared from personal experience, scholarly research, public documents and current media reports served as a means to help students understand the course content. Opening up further discussions with students using practical examples on related topics in a receptive way encouraged students to participate in the relational space, leading to some level of trust in the teacher-student relationship. However, to build my confidence in the ability of students to interact professionally with community organisations and their peers and to provide valuable service to the advancement of communities, I relied on four sources of information: (1) ongoing discussions within our teacher-student relationship, (2) individual reflections on change management submitted by each student, (3) proposed change management plan submitted by each group of students, and (4) signed contractual agreement between student groups and community partners. For instance, discussions in a conversational manner with students on a referral change management plan for a not-for-profit organisation helped increased my confidence in the students’ commitment to the service-learning project:

[Reading from a paper] So, we are hoping to have three main recommendations with a couple of smaller sub-recommendations. So for our first one, we are thinking of their [community organisation] referral forms to be all online. So, people [service-users] have to print them, fill them out and then scan the forms back before they submit the forms. So we are going to make an online document. Or at least try to create a format of an online document.

Okay.

Then, the second would be like a checklist so that people can get their stuff ready before they submit it.

Sure. So they [community organisation] don’t have that now?

They don’t have that.

They [service-users] hand in the application forms to XXXX [community organisation], and they [community partner] have to come back and say to their clients, “you need to give us this, this and this. So, it takes forever.

So they [community partner] will need an online kind of checklist. Do they have the money for that?

Even if, we could create something like a format for them.

Oh … ! A format to enable them to see what the real online checklist will look like. That would be nice. Okay good. I like that.

The above dialogic interaction presents three key aspects that facilitated the flow of interactions to give student a ‘voice’ in the conversations and helped provide confidence in their suggestions. Firstly, the interactive discussions with the students demonstrated my willingness to listen openly and acknowledge the perspectives of the students. This helped create the flow of interactions such that the students were comfortable to share their ideas. Secondly, the use of words, sentences and questions in a conversational tone and plain English language enabled the students and me (instructor) to gain further knowledge on the relevance and feasibility of the proposed change plan. For instance, using the probing question ‘Do they have the money for that?’ focused the students’ attention on the financial implications of their plans. This resulted in the modification of initial plans to create a sample (format) version of an online checklist form for community partners. Thirdly, I used affirmative terms such as ‘That would be nice’ and ‘I like that’ to commend the students’ efforts and demonstrate my acceptance of the modified plans. As a result of this, I was able to build my confidence in their ability to offer valuable service to community partners, and it also gave the students some confidence.

Subsequent discussions with students and my feedback on their submitted reports helped build my confidence in their readiness to work together with their peers and community organisations. The signed contractual agreement between the student groups and community partners helped ensure the confidentiality of information. Each of the four sources of information helped develop my trust in the ability of students to deliver actionable knowledge on change management to community organisations professionally. While it is arguable that educators cannot develop total confidence in the ability of undergraduate students to offer valuable service to community organisations and take ownership of their learning process, providing opportunities for discussions and feedback can help educators to develop confidence in the ability of students to learn and offer valuable community service. A trustful student-teacher relationship can help develop further collaboration between students, teachers and organisation partners. This may help provide actionable knowledge that can transform and build local communities.

Evaluation of students’ performance

The in-person discussions with students, their final individual reflective essays, group field report and formal presentations indicated that the students had gained a practical understanding of change management in organisations. In addition, the subsequent discussion with students indicated their awareness of the intricacies and requirements of organisational members to function within the work environment. While not all the students performed optimally as I expected, the discussions with students revealed their different levels of understanding change management and future plans to engage with the local community. Students who worked with the private aviation company acknowledged the significance of deliberately promoting a positive relationship between top managers and frontline staff during organisational change. They noted that the intentional efforts of management to engage in one-on-one discussions with organisational members would help identify reasons for resistance towards change efforts and mitigate challenges that may arise as a result of workers’ resistance. Other students who worked with not-for-profit organisations became aware of the financial resources required to implement desirable change initiatives and the profound impact this has on organisational members’ options for change.

On the change management needs of the cooperative civil society, the student groups presented a communication plan, a resistance management strategy, a detailed implementation plan and a change-messaging guide with a supplementary scheduling video. Few students volunteered, outside the remit of the course, to work with the cooperative organisation. It was interesting to note that Felix, who was least interested at the start of the course, opted to financially support and act as an advocate for the civil society group. This indicates the intentions and deliberate acts of students to engage in citizenship behaviour as a result of their service-learning experience.

In assessing the performance of students, agencies of community organisations lauded the efforts and contributions of some students, making commendations such as ‘the reports are exceptional’, ‘a fabulous job’, ‘spectacular’, ‘they did a great job in outlining their deliverables’, and ‘we had some take-aways we learned’. They also noted some recommendations from the students that were not applicable to their organisations due to limited financial resources. Interestingly, they recognised and appreciated my efforts in facilitating this learning opportunity to work with the students. While I cannot completely link the overall performance of students to the demonstration of relational pedagogical practices, it is beyond doubt that certain elements of relational competencies impacted the performances of some students. This includes competencies such as interpersonal communication in sharing meanings and expectations in plain language, demonstration of an attentive presence in response to students’ requests for adjusting assessments, the provision of formative feedback on their group presentations and midway assessments of their final group field reports.

Discussion

This study aimed to respond to two research questions:

How does the literature on relational pedagogy describe these four relational competencies?

How were these four relational competencies demonstrated in delivering service-learning in management education?

In response to the first research question, the review of the literature on relational pedagogy indicated a general consensus on the descriptions of the relational competencies of interpersonal communication, an attentive presence and trust. For instance, Jensen et al.’s (Citation2015), Romano’s (Citation2004) and Aspelin’s (Citation2019) studies all show that an attentive presence is demonstrated by being observant, sensitive and responsive to the feelings, emotions, reactions and contributions of students. Several studies described interpersonal communication in relational pedagogical practices as free-flowing interactions that give both entities a voice in conversations to share feelings and meanings (Biesta, Citation2004; Margonis, Citation2004; Pijanowski, Citation2004). In addition, Pearce and Down (Citation2011) indicated a core aspect of clarity in communicating with emphasis on using plain language for easy comprehension. Regarding trust, Aspelin and Jonsson (Citation2019) and Bingham and Sidorkin (Citation2004) described a trustful teacher-student relationship as the ability for both entities to be open to accepting shared information without fear of being discounted, disregarded, alienated or belittled.

Interestingly in the description of care, scholars have presented several terms to explain its meaning. These include ‘being involved’, ‘understanding’, ‘good’, ‘helpful’, ‘respectful’, ‘appreciating and attending to students’ needs’ ‘spending time with students outside of scheduled class times’, ‘showing concern’, ‘listen attentively’, and ‘recognising individuality’ (Margonis, Citation2004; Noddings, Citation2012; Reeves & Le Mare, Citation2017; Thayer-Bacon, Citation2004). This indicates that while general meanings of the relational competencies of interpersonal communication, attentive presence and trust can be gleaned from related literature, the aspect of care remains vague. Thus, in theorising about relational pedagogical practices, there should be thoughtful consideration on conceptualising the relational competence of care, as it can be expressed via other competencies. Also, the realisation that the element of care can be expressed via other competencies posits care as the basis from which other competencies such as respect/appreciation, being adaptable, trust, reflexivity, interpersonal communication, empathy, attention of presence of mind, and inclusivity can be expressed. This study, in providing a conceptual framework on the interrelated sub-elements of teachers’ relational competencies (see ), shows how the relational competence of care can be expressed in other competencies. Thus, it indicates that the element of care serves as a hub that influences the demonstration of other competencies.

Given the significance of relational competencies to the learning experiences of students, there have been concerns on how educators can develop and demonstrate these relational competences (see Aspelin & Jonsson, Citation2019; Hollweck, Reimer, & Bouchard, Citation2019). This reflective essay provides descriptions of how relational competences are demonstrated in facilitating service-learning. The process involves deliberate attempts for educators to share their identities, cultural backgrounds, academic, and career achievements in a relaxed and conversational manner to help build rapport and trust with students. Then, educators can seek knowledge on the sociocultural and academic backgrounds of each student to gain a better understanding of ‘Who’ they are, their capabilities and situational context. This process moves the approach from telling, in which instructors emphasise on informing students (see Reeves & Le Mare, Citation2017), to sharing, in which instructors offer opportunities for students to be part of the teaching relationship. Sharing gives students a sense of belonging and a chance to voice their own identities, perspectives and experiences. Gaining further information about each student can enable instructors to better prepare class content and facilitate subsequent discussions to enhance individual students’ engagement in the learning process. In addition, it can stimulate students’ interests in service-learning, which may result in positive outcomes on the project deliverables to community partners.

This study also indicates that the process of cultivating a supportive teacher-student relationship extends beyond face-to-face interactions and encounters in-class sessions (Pearce & Down, Citation2011) to interactions via emails, text messages, telephone calls and educational technology apps. Extending the nature of the relational communication dynamic through these channels of communication can increase engagement with students and, in turn, provide more opportunities for a teacher to understand their interests, challenges, academic knowledge and future goals. In this way, educators can develop relational communication by extension, in that extension presents continuous opportunities to demonstrate the authentic sense of caring.

Implications of relational pedagogy on service-learning in higher education

The practice of relational pedagogy with its related teaching competencies offers some potential benefits that enhanced my delivery of service-learning in management education. Firstly, the practice of relational pedagogy shifts the teaching focus from student-centred and teacher-centred to a teacher-student relationship (Aspelin, Citation2014; Ljungblad, Citation2019). The emphasis on this relationship context prepares the mindset of the educator to approach service-learning as a collaborative learning experience between the teacher and the student. Within this collaborative learning space, both entities share their identities, interests, educational and sociocultural backgrounds, and challenges. The motives for learning and teaching is also shared to foster genuine care and trustful teacher-student relationship. This pedagogical orientation and collaborative approach towards teaching and learning helped prepare me, as an educator, to move beyond being knowledgeable about the subject-matter to embracing further understanding of the individuality of each student. Further knowledge of each student enabled me to adapt teaching techniques and assessments to encourage students to participate in service-learning. Interpersonal interactions and engagement with each student assisted in promoting an equitable learning experience for students. For instance, attention was also accorded to students who were nervous, introverted, uninvolved in the learning process and perceived as disadvantaged students (see Pearce & Down, Citation2011).

Secondly, the demonstration of relational competencies associated with relational pedagogy is significant in the delivery of service-learning due to the negative implications of unsuccessful community-engaged learning (Blouin & Perry, Citation2009). Poor delivery of service-learning may lead to low students’ satisfaction, a poor learning process, and a low value on the quality of projects or service delivered to community organisations (Blouin & Perry, Citation2009; Conville & Kinnell, Citation2010). It may also result in the perceived ineffectiveness of the teacher, poor university-community relationships, and a bad reputation for the university. In an attempt to mitigate such adverse effects, scholars have focused on improving specific service-learning content, such as the planning phase, with a focus on selecting appropriate community organisations and projects and setting clear expectations for students and community organisations (Conville & Kinnell, Citation2010). Other studies have indicated the need for faculty to let students self-select community projects, encourage communication between the server and the served and create adequate time to complete projects (Aday et al., Citation2015; Brower, Citation2011; Celio et al., Citation2011). The aspect of constructing a rigorous and authentic reflection component in service-learning is also identified as an additional aspect that aids in the effective delivery of service-learning (Ash et al., Citation2005; Eyler & Giles, Citation1999; Gelmon et al., Citation2001). While the consideration and inclusion of these components are significant, it is pertinent to note that the actual facilitation and delivery of the same components largely depend on the relational competencies demonstrated by faculty members.

An educational relational approach void of demonstrating relational competencies makes the service-learning process a mere instrumental teaching practice. In the instrumental approach, the content of subject-matter disciplines is passed on to students to receive, decipher, memorize and reproduce or regurgitate the same information. In addition, the teacher-centred instrumental approach to learning presents a strict distance between teachers and students, which can alienate some students in the learning process (see Pearce & Down, Citation2011). This may lead to low motivation and disinterest of students on the course; and, subsequently, low deliverables to community organisations. With the intent of providing service-learning to foster students’ active learning and civic engagement, the creation of relational space of care and trust, and demonstration of these relational competencies becomes a vital aspect in the delivering of service-learning.

Further analysis of the demonstration of four relational competencies indicates that the same competencies could be demonstrated in other forms of experiential learning and teaching practices that promote positive teacher-student relationship to support students’ learning experience. This includes career-oriented experiential learning such as practica, cooperative education and internships (Bringle, Citation2017) gaming simulations; structured exercises, case studies; and role-play (Gallagher, Citation2011; Kenworthy, Citation2010). However, educators may need to adapt their interactions with students to fit the objectives of the given teaching practice when demonstrating relational competencies.

On the challenges of relational pedagogy in service-learning

There were some challenges identified while facilitating service-learning in management education through the demonstration of relational competencies. Two main difficulties identified were (1) the differing expectations that students had for the teaching approach and (2) limited duration of delivering the course and related change management projects to community organisations.

Differing expectations that students had for the teaching approach

Students in higher education are often fully cognizant of their individualities and expectations for the learning process. They predetermine aspects of their individualities they wish to share and part of the course they intend to learn regardless of the outcomes of their decisions or the teaching efforts of the faculty member. Other students are predisposed to the teacher-centred instrumental approach of learning and thus indicate a preference for a transactional businesslike relationship with their educator. The actions (or inactions) of these students present a challenge to the teacher trying to demonstrate relational competencies to foster a caring and trustful teacher-student relationship. One way to potentially lessen the impact of students’ actions on the learning process is for the teacher to spend more time with them to understand the rationale for their actions while still maintaining set boundaries. The process of understanding students’ learning perspectives without interfering in their personal lives may create a dynamic relationship of care (Margonis, Citation2004). In addition, educators can provide a debriefing of relational pedagogical practices at the start of the course so that students are better informed on their pedagogical stance (see Aspelin, Citation2014). While this information cannot guarantee a change in their orientation to learning, it will create an awareness of relational pedagogical methods. An awareness of relational pedagogy may influence students’ acceptance of engaging in a dialogical teacher-student relationship. Alternatively, educators can openly accept these students for who they are, while channelling the attention of students to the attainment of the learning outcomes of the course. The latter is the least viable option as it leaves faculty members in limbo with little understanding of the student.

Limited duration of delivering service-learning and related change management projects to community organisations

Fostering a caring and trustful teacher-student relationship with each student towards the facilitation of service-learning does require adequate time beyond the designated 15-week period of teaching. Similar to Pearce and Down (Citation2011) study, time constraints due to the limited duration of completing an academic course thwarts the intention of forming a trustful teacher-student relationship with each student. This becomes more challenging with a large class size or number of students (Roman, Citation2015; Thayer-Bacon, Citation2004). To mitigate this challenge, educational institutions can include additional faculty members who uphold relational pedagogical practices and previous students with experience in service-learning to assist in facilitating service-learning (see Kropp et al., Citation2015). Alternatively, institutions can reduce the class size, so each student is accorded adequate time to learn collaboratively. In addition, a service-learning course can be delivered through independent learning or via semesterisation (two or three academic semesters) for one year or more. Both approaches can help educators to better assess each student’s progress in the learning process over time. Lastly, the content of the service or project to be delivered to community organisations should be manageable such that students, in collaboration with faculty members and community organisations, can provide actionable knowledge within term time and gain knowledge from their individual experiences on a service-learning course.

Limitations and further research

This study presents a single perspective on demonstrating relational competencies associated with relational pedagogy in management education. The findings mainly depend on my self-reflections on service learning in a change management course. Thus, it does not take into consideration the perspectives and experiences of other faculty members and students engaged in service-learning. However, it provides a unique perspective of applying relational pedagogical practices in higher education. Additional knowledge to improve the findings can be derived from studies exploring, concurrently, educators’ perspectives and students’ viewpoints on their relational practices. Findings from these studies may assist in providing a collaborative identification of core relational pedagogical practices vital to students’ engagement in service-learning.

In addition, further studies, using digital video recordings, can analyse visual demonstrations of faculty members’ relational competencies and students’ responses during in-class sessions (Aspelin, Citation2019; Aspelin & Jonsson, Citation2019; Ljungblad, Citation2019). Such an analysis may provide more depth of information than self-reflections on the demonstration of relational pedagogical practices in institutes of higher education, as it would capture actions and inactions that are not easily recollected and articulated by scholars. Using visual methodologies would allow for more interactional analysis and nuanced understanding of actual demonstrations and reactions of faculty members and undergraduate students to relational pedagogical practices in service-learning. Future studies can also explore other interrelated relational competencies that were not fully analysed in this study, such as reflection practice (intrapersonal communication), empathy and flexibility. Additional insights derived from further studies using visual research methods and exploring other relational competencies can improve the professional development of faculty members.

Conclusion