Abstract

Mass religious events are often an unprecedented tourist opportunity. A clear example was the meeting of Pope Francis with more than three million young people in July 2016 in Krakow, on the occasion of the 31st World Youth Day. Although it was a mainly religious event, the experience of past editions (for example, Madrid 2011 and Rio de Janeiro 2013) shows the strong impact of WYD on the local tourism and hospitality industry. The official website of such event becomes an informative point of reference and a crossroads where the needs of the users and the offer of the promoters meet. This study analyzes the official website of the WYD Krakow 2016 as a source to promote religious touristic sites.

Introduction

World Youth Day (WYD) is a massive religious event promoted by the Catholic Church every year, as a spiritual and cultural experience aimed at young people. This massive event was launched by Pope John Paul II in 1987, and it has been held since then every other year in Rome and in between in different cities around the world designated by the Holy See. When it is not organized in the Italian capital -where the event has a lower profile-, it gathers hundreds of thousands of young people (i.e. Madrid 2011: 2,000,000 participants; Rio de Janeiro 2013: 3,700,000; Krakow 3,200,000, to name some of them) 1. Although it is not related to a place or a person, this event can be considered as a modern pilgrimage, as it gathers thousands of participants from all over the world with a religious motivation and it includes different acts of worship, as masses, encounters of catechesis, religious music concerts, theatrical performances of Jesus’ passion, meetings with bishops and other leaders, etc. (Norman and Johnson Citation2011).

Having such a huge mass of pilgrims becomes not only a spiritual experience for the participants but also a promotional opportunity for any country. Local tourism and economy benefit also from these events, as the participants usually take advantage of their pilgrimage to visit local places, enjoy gastronomy, buy souvenirs and so on.

When traveling abroad, the great number of possible activities encourage visitors to look for trustworthy sources of information, such as official websites or social media channels of a cultural event or, as it is the case, a religious gathering or pilgrimage (Cantoni et al. Citation2016). Among those channels, social media venues are particularly helpful for breaking news, while websites host more mid-term relevant information. In order to plan an event, these digital sources are very important as they are thought to help and improve the experience of pilgrims (De la Cierva Citation2014), thank also to their almost complete accessibility through smartphones. Through digital channels, people keep continuously updated and have direct access to data and content that are relevant, bypassing the mediation of mass media (De la Cierva et al. Citation2018).

In the WYD in Krakow, digital technologies aimed at young people were relevant, given that the average age of the participants in the event was 22 (with a slight majority of women), and that they were from developed countries (one in four were from Poland. Besides Poland other countries with high representation were Italy, Brazil, France, Spain, Portugal, the United States, Mexico, Argentina and Germany). 46.6% of the visitors to the WYD website during the period of 1 February 2016 to 31 July 2016 accessed it via Smartphone or Tablet, which suggests that the public was familiar with the use of ICT. In our opinion, the Catholic worldwide meeting of the WYD, similar to other huge religious events such as the Hajj in Mecca (Saudi Arabia) or the Kumbh Mela (India), is an opportunity to study the role of ICT (Information and Communication Technologies) in religious tourism.

Literature review

Pilgrimages have been an expression of faith in many religions for centuries, and in recent times they have experienced a resurgence (Digance Citation2003; Eade Citation2015). Traveling for religious motivations frequently reflects the spiritual travel that every believer experiences in his or her personal spiritual life (Turner and Turner Citation1978; Cohen Citation1979; Campo Citation1998; MacCannell Citation1999; Timothy and Boyd Citation2003).

In modern times, developments in communications and cheaper travel have made it easier for pilgrims to set off for holy destinations. Moreover, religious motivations and religious destinations are key factors in the tourism of the 21st century (Olsen and Timothy Citation2006; Raj and Morpeth Citation2007). Jackowski (Citation2000) estimated that around 220–240 million people a year go on pilgrimages, the majority being Christians (150 million), Muslims (40 million), and Hindus (30 million), although he does not quote the origin of this estimation). Some religious pilgrimages gather thousands of participants, but most of them are small and medium sized (Bowdin et al. Citation2006; Rubio and de Esteban Citation2008; Cerutti and Piva Citation2015).

Although religious beliefs are the main cause of pilgrimages, these kinds of events are frequently motivated by complementary reasons -other than religion- such as culture, relationships and entertainment (Vukonić Citation1996; Shackley Citation2001). Some authors deny that pilgrimages can be considered as touristic events, as they are strongly conditioned by their religious purpose (Olsen and Timothy Citation2006); others recall that a visit to a sacred place or the participation in a religious event may not be linked to religious reasons (Nolan and Nolan Citation1992; Woodward Citation2004); while the third group of scholars (i.e. Smith Citation1992; Ostrowski Citation2000) describes pilgrimage as the most radical format of religious tourism, in opposition to secular tourism. Ultimately, we can consider tourism and pilgrimages as two sides or faces of a similar journey whose boundaries are difficult to establish and frequently melded (Collins-Kreiner Citation2010; Liutikas Citation2012). However, whether it is driven by religious or other reasons, pilgrimage is always an opportunity for tourism experiences.

Such melting of tourism activities and religious pilgrimages can be better clarified today, thanks to ICT. In fact, religious pilgrimages have proved their ability to adapt to the innovations of modern society and even to appropriate them (Liutikas Citation2012). The internet and mobile devices nowadays facilitate connection and communication in a way that was unimaginable until a few years ago and are very useful innovations for improving the preparation of the events, enhancing the participation in ceremonies and also communicating with pilgrims (Schnell and Pali Citation2013; Narbona and Arasa 2016). Although these tools give us the possibility to have a closer look at the users through the study of digital analytics -what the real interests of pilgrims are, what they request, where they go, how they feel about an event, and so on- large-scale religious events have seldom been analyzed in scientific literature up to this point (Hameed Citation2010; Muaremi et al. Citation2014).

The WYD held in Krakow in July 2016 attracted more than three million young people from 187 countries. For Bilska-Wodecka, Liro, and Sołjan (Citation2017), the motivations of the pilgrims were mainly religious (87%, whose specific interests were: meeting with the Pope, prayer, spiritual development, experiencing the community of the Church, and improving their knowledge of religion), but a significant 52% also expressed interest in tourism during the pilgrimage to Poland (sightseeing, cultural events and knowledge of the site). Moreover, 23% of the pilgrims mentioned also other social purposes (meeting new people, social relationships, escaping from everyday life, recreation and entertainment). Similar results were obtained by other surveys (Gad3 Citation2016). As it has already been demonstrated (Gaweł Citation2017), the impact of WYD on the tourist market was quite significant. Most of the attractions were available both before and after the event. The mere fact of announcing that Krakow was going to host WYD in 2016 contributed considerably to the strengthening of the city’s position on the list of the world’s most popular tourist destinations.

Methodology

This paper aims at shedding light on the relationship between religion and tourism in the era of digital technologies, especially in the context of massive events. In particular, it helps to discover if religious travelers (pilgrims) make use of ICTs to pursue tourism related goals.

In case of the World Youth Day, we have to take into consideration that the main public are young people, more used to new technologies for keeping in contact and dealing with ordinary life. Therefore, WYD is a relevant event to check if digital instruments play a crucial role in promoting these events and giving information to the participants. The data collected by the official website can help us to understand better the interests and behaviors of the users. Although social media are also an interesting tool, official websites are relevant and more of a passive crossroads where users gather to collect useful information. Focusing the analysis on the official website as one of the bests sources of information, also for touristic destinations, it is possible to center our research on two hypothesis:

H1. The official website of a religious event fosters/supports the promotion of surroundings tourism destinations/attractions.

H2. Pilgrims have a similar interest in religious as well as in other tourism destinations/attractions along their journey.

The WYD Krakow official website (http://krakow2016.com/ [Please refer endnote 1]) had eight main sections (WYD, News, Spiritual Formation, Infopack, Poland, Media, Download, Contact), where Poland contained the subsections related to tourism (Discover Krakow, Discover Małopolska, Discover Poland, Famous people connected with Krakow, although not all of them were offered in all languages). The inclusion of the section Discover Krakow on the official website was a part of the agreement between the Local WYD Organizing Committee and the KBF (Krakow Bureau of Festivals). Some members of the Polish Touristic Organization (POT) collaborated with the team of Communications (source: Kłosowski, M., Content Manager of the Official Website WYD Krakow 2016; Personal Interview, January 2017).

In order to know how much attention the contents linked to tourism attracted, it is possible to analyze the number of visitors received in each section, a number that reflects the interests of the users. Although those numbers cannot give a complete answer to the question- because users can collect information from other sources, for example, navigation can be considered as indicative of the preferences and interests of the users and pilgrims.

In order to check the validity of H2 through the data collected on the official website, the number of views to pages that give information on religious destinations will be compared to those on other non-religious destinations.

Analysis

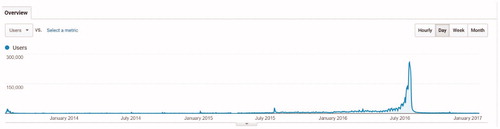

The data produced by the official website of the World Youth Day held in Poland were analyzed making use of the tool Google Analytics. The event took place between 26 July 2016 and 31 July 2016, although the website had been launched three years before (on 25 July 2013). The web had significant activity until 10 September 2016. The website offered contents in nine languages: English, Spanish, French, Italian, Polish, Ukrainian, Deutsch, Portuguese and Russian.

The analysis of the data has been limited to the period with the highest activity: that is to say, from 5 July to 5 August 2016. As shows, the number of visits to the official website of WYD Krakow follows the template of an isolated event: a period of quiet activity in the long and mid-term pre-event, a peak of visits that goes up suddenly in the short-term up to the event and during the event itself and, finally, a drastic collapse of the visits (the area in grey color indicates the period analyzed in this paper) right after the event:

H1 stated that a promotional website for a religious event helps in the promotion of cultural and religious destinations. Websites structure their content in sections, and users concentrate their visits in the sections that offer the content they are looking for. As it has been said, the main bar contained eight sections. Analyzing the number of pageviews accumulated by any of them, it is possible to know which were the most requested contents. From the eight sections, two of them were dedicated to services (Download and Contact), so they have not been included in the analysis. and Graphic 2 shows the results of the English and Polish versions of the website (the analysis has been made on these languages because they represent the domestic public and the most prevalent international one).

Table 1. Distribution of pageviews to the main sections of http://krakow2016.com/ (English and Polish versions). Period: 5 July 2016 to 5 August 2016 (in %). Source: Google Analytics.

The section that gathers the most visits in both languages is ‘WYD’. It contains useful information, like the program, the places where the main gatherings would be held and so on. ‘Discover Poland’, the section aimed at the promotion of tourism, received 4,43% and 1,23% of the English and Polish language visitors, respectively. This number gives an idea of the low interest of the users and consequently, of the modest reach of the promotional efforts of tourism on the official website.

These results may induce to conclude that the touristic contents were almost irrelevant. However, a closer look at the different travel communities of the participants can help to understand better the results: 79% of the youth traveled to the WYD with a religious group, parish or association; 12% with friends; 5% with their family or their school; and 4% alone (Gad3 Citation2016). Those percentages suggest that most of the participants depended on a group leader, responsible for the practical planning of the pilgrimage. That organization in groups is characteristic of these religious events -differently from music concerts or other meetings- because young members of the Catholic Church are commonly organized in local groups (parishes, scout associations, etc). Hence, the group leader has an important role, because is the one who checks the useful information before organizing the trip or, at least, arriving at the place from his office or home. It is possible to suppose that the section ‘Infopack’ is one of the most relevant to the group leaders, as it contains information on food and shelter for pilgrims. Broadening the dates of the data of analysis on the website (From April 2016 to September 2016), the number of visits of the sections ‘Infopack’ and ‘Discover Poland’ are not so different (the Polish language has not been analyzed as the website doesn’t offer the section Infopack for the Polish people). This hypothesis of group leader’s usage is supported by the fact that 52% of the requests of information were from a desktop while 42% were from a mobile device.

Considering the long term (April 2016 to September 2016), the comparison between practical contents linked to a pilgrimage (Infopack section) and cultural contents (Discover) related to tourism allows us to conclude that those two activities are not so far apart and most probably the group leaders are the main users of both website’s contents.

Within the section ‘Poland’, 23 specific destinations were proposed to visitors, and each one of them had a single page on the official website with a short description of the history of the place and practical information (no spiritual considerations). Two clicks from the homepage were enough to reach these contents. From the 23 destinations, 6 were religious places, while 17 were civil buildings, parks, scenic spaces or similar.

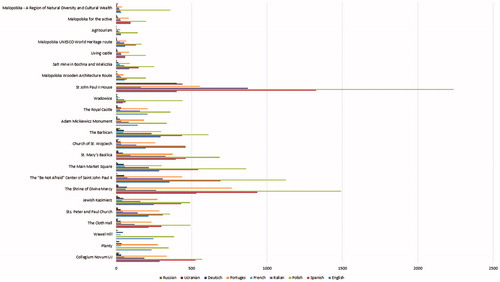

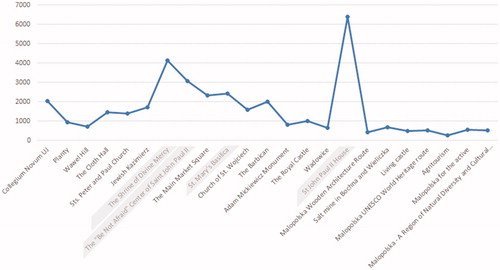

In order to know the specific interests of users on the array of pages aimed to promote tourism in Krakow and its surroundings, collects the number of visits made by users to the pages explaining the different monuments and places (religious destinations are highlighted in grey) inside the ‘Poland’ section.

Table 2. Visits to ‘Infopack’ and ‘Discover’ sections on four different languages from http://krakow2016.com/. Period: 1 April 2016 to 1 September 2016. Source: Google Analytics.

When representing graphically the data ( and ), it is possible to appreciate that the number of visits follows a similar pattern in different languages. The most significant aspect of the results is that the peaks always correspond to four of the religious destinations: St John Paul II House, The Shrine of Divine Mercy, The ‘Be not Afraid’ Center of Saint John Paul II, and Saint Mary’s Basilica.

Conclusions

Analyzing just the official website of a religious event in order to know what impact it has on the promotion of tourism has many limitations. Websites are just a small part of many channels of communication that are used to send messages to the participants. In the case of WYD Krakow 2016, social media played a relevant role, as the main public was ‘millennials’ who are very used to interacting using social networks. Complementary studies may help in proving this hypothesis. Another limitation is that visiting a page on a website doesn’t mean automatically a real will to visit a specific place. Results show the potential interest of some users, but not the effective visit to the places.

In spite of the aforementioned limitations, the data collected may shed some light on the role of an official website on promoting tourism during a big religious event. H1 could not be confirmed, since the number of visits to the tourist pages of the website was very limited. That does not necessarily refute H1 since other causes can be involved: lack of interest of the website team of a specific event in promoting tourism destinations, scarcity of resources to enhance tourism pages, etc. What it can certainly be deduced is that the official website seems to be the more suitable channel to transmit useful and practical information related to the event. At the same time, in order for H1 to be confirmed, not only should the number of visits to the destination-related pages on the website has been higher, but also the pageviews analysis should have been compared/complemented with some other data taken directly from pilgrims, such as interviews asking if they visited other religious and cultural destinations during the event and where they looked for information about such destinations.

H2 was not confirmed by the data analyzed. However, the analysis of the interests of the visitors that have used the official website of WYD Krakow 2016 as a source of information for tourism shows that religious places have more value to pilgrims than other touristic destinations. When making a pilgrimage, other than the participation in the event itself, pilgrims look for other places to visit but always with a religious touch. This conclusion may inspire enterprises or institutions that organize pilgrimages, as they can attract more people giving more attention to their programs to religious activities and destinations.

Notes on contributors

Juan Narbona graduated from the University of Navarre (Spain) in Communication Sciences, where he worked in the Department of External Communication until 2000. Since then, he has served as Web Editor for the Opus Dei Information Office. He also holds a Doctorate in Institutional Communication from the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross (Santa Croce) and teaches in the area of Digital Communication.

Daniel Arasa has a Bachelor’s Degree in Journalism from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB), Spain, a M.A. in Television and Radio from the Southern Methodist University (SMU), Dallas, TX, and a Ph.D. in Social Institutional Communications by the Pontificia Università della Santa Croce, Rome, Italy. He worked from 1994 to 1997 as a journalist in Europa Press news agency (Spain). In 2011, he started teaching at Santa Croce, where he currently is Associate Professor of Digital and Strategic Communications, Vice Dean of the Communications School and editor of the academic journal Church, Communication and Culture. Moreover, he is member of the Board of Directors of Rome Reports TV, news agency specialized in the coverage of the Pope, the Vatican and the Catholic Church. His main research interest is online religious communication, particularly the Internet communication of Catholic institutions.

Graphic 1. Evolution of visits to the official website of the WYD in Krakow from its launch (25 July 2013) to February 2017.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this paper would like to thank the manager of content for the official website, Mr. Michał Kłosowski, for providing direct access to the data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 The numbers were provided by the organizational committee of each WYD. After the first two gatherings in Rome (in 1984 and 1985), the subsequent international gatherings have taken place in Buenos Aires, Argentina (1987); Santiago de Compostela, Spain (1989); Czestochowa, Poland (1991); Denver, U.S.A. (1993); Manila, Philippines (1995); Paris, France (1997); Rome, Italy, for the Millennium Jubilee (2000); Toronto, Canada (2002); Cologne, Germany (2005); Sydney, Australia (2008); Madrid, Spain (2011); Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (2013); Krakow, Poland (2016); and forthcoming in Panama City, Panama (2019). For more information on general aspects of WYD and similar religious events, see: De la Cierva, S. et al. 2018. Mega events of the Catholic Church: Logbook for organizers and communicators. Independently published.

References

- Bilska-Wodeck, E., J. Liro, and I. Sołjan. 2017. “Motivations of Visitors at the Pilgrimage Center in Krakow (Poland).” Proceedings of the 10th MAC 2017, vol. 10, 205–207.

- Bowdin, G., J. Allen, W. O’Toole, R. Harri, and L. McDonnel. 2006. Events Management. 2nd ed. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann Elsevier.

- Campo, J. E. 1998. “American Pilgrimage Landscapes.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences 558 (1): 40–56.

- Cantoni, L., S. De Ascaniis, E. Marchiori, E. Mele., 2016. “Pilgrims in the Digital Age: A Research Manifesto.” International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage 4 (3).

- Cerutti, S., and E. Piva. 2015. “Religious Tourism and Event Management: An Opportunity for Local Tourism Development.” International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage 3 (1). Available at: http://arrow.dit.ie/ijrtp/vol3/iss1/8

- Cohen, E. 1979. “A Phenomenology of Tourist Experiences.” Sociology 13 (2): 179–201.

- Collins-Kreiner, N. 2010. “Geographers and Pilgrimages: Changing Concepts in Pilgrimage Tourism Research.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 101 (4): 437–448.

- De la Cierva, S. 2014. Communication in Church Events. The Making of Wyd Madrid 2011. Rome: Edusc.

- De la Cierva, S., et al. 2018. Mega Events Of The Catholic Church: Logbook For Organizers And Communicators. Independently published.

- Digance, J. 2003. “Pilgrimage at Contested Site.” Annals of Tourism Research 30 (1): 143–159.

- Eade, J. 2015. “Pilgrimage Studies – An Expanding Field.” Material Religion the Journal of Object Art and Belief 11 (1): 1–4.

- Gad3 2016. Research on Krakow's 2016 WYD participants. Avalilable at: https://www.slideshare.net/GAD3_com/research-on-krakows-2016-wyd-participants

- Gaweł, Ł. 2017. World Youth Day Krakow 2016. Selected Study Results. Warsaw: Narodowe Centrum Kultury [National Centre for Culture].

- Hameed, S. 2010. “ICT to Serve Hajj: Analytical Study.” Computer and Communication Engineering (ICCCE), 2010 International Conference on, Kuala Lumpur, 2010; 1–7.

- Jackowski, A. 2000. "Religious Tourism: Problems With Terminology". In Peregrinus Cracoviensis, edited by A. Jackowski, 63–74. Kraków: Institute of Geography, Jagiellonian University.

- Liutikas, D. 2012. “Experiences of valuistic journeys: motivation and behaviour”. Contemporary Tourist Experience: Concepts and Consequences, edited by R. Sharpley. and P. Stone, 38. London: Routledge.

- MacCannell, D. 1999. The Tourist: A New Theory Of The Leisure Class. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Muaremi, A., A. Bexheti, F. Gravenhorst, J. Seiter, S. Feese, B. Arnrich, and G. Tröster. 2014. “Understanding Aspects of Pilgrimage Using Social Networks Derived from Smartphones.” Pervasive and Mobile Computing 15: 166–180.

- Narbona, J., and D. Arasa. 2016. “The Role and Usage of Apps and Instant Messaging in Religious Mass Events.” International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage 4 (3).

- Nolan, M. L., and S. Nolan. 1992. “Religious Sites as Tourism Attractions in Europe.” Annals of Tourism Research 19 (1): 68–78.

- Norman, A., and M. Johnson. 2011. “World Youth Day: The Creation of a Modern Pilgrimage Event for Evangelical Intent.” Journal of Contemporary Religion 26 (3): 371–385.

- Olsen, D. H., and D. J. Timothy. 2006. “Tourism and Religious Journeys”. In Tourism, Religion and Spiritual Journeys, edited by DJ. Timothy and DH. Olsen, 1–21. New York: Routledge.

- Ostrowski, M. 2000. "Pilgrimages or Religious Tourism", Peregrinus Cracoviensis, Zeszyt 10, 53–61.

- Raj, R., and N. D. Morpeth. 2007. “Introduction: Establishing linkages between Religious Travel and Tourism”. In Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage Festivals Management: An International Perspective, edited by R. Raj and ND. Morpeth, 1–14. Wallingford: Cabi International.

- Rubio, A., and J. de Esteban. 2008. “Religious Events as Special Interest Tourism.” A Spanish Experience. Pasos. Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural 6 (3):419–33.

- Schnell, T., and S. Pali. 2013. “Pilgrimage Today: The Meaning-Making Potential of Ritual, Journal of.” Mental Health”, Religion and Culture 16 (9): 887–902.

- Shackley, M. 2001. Managing Sacred Sites: Service Provision And Visitor Experience. London: Continuum.

- Smith, V. L. 1992. “Introduction: The Quest in Guest, in Pilgrimage and Tourism.” Annals of Tourism Research 19 (1): 1–17.

- Timothy, D. J., and S. W. Boyd. 2003. Heritage Tourism. Harlow: Pearson Education.

- Turner, V., and E. Turner. 1978. Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Vukonić, B. 1996. Tourism and Religion. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- Woodward, S. C. 2004. “Faith and Tourism: Planning Tourism in Relation to Places of Worship.” Tourism and Hospitality Planning and Development 1 (2): 173–186.