Abstract

This article explores how the Public Television Service (PTS) of the Republic of China-Taiwan, born in 1998, has contributed to promoting the Taiwanese identity through documentaries, by conveying cultural issues in a way that could be shared by the majority of the population, independently of political opinion. Among the main cultural aspects, PTS gave particular attention to respect for other ethnic groups, ecology, traditions, and religion. The first part of the study begins with a summary of the social and political background surrounding the birth of PTS—after the first free elections of 1996—including the development of the two main political parties, their proposals about the relationship with mainland China, and how that feeling has shifted towards a more cultural dimension. The second part includes a thematic analysis (content-discourse analysis with qualitative methodology) of a selection of six awarded documentaries aired around October 2011 (and later), in the year that marked the 100th anniversary of the foundation of the Republic of China, and constituted a crucial moment to relaunch the Taiwanese identity.

1. Introduction

In May 1997, after almost 10 years of arduous negotiations (Tsai Citation2016, 127), the Republic of China (Taiwan),1 established its Public Service Broadcasting (PSB) through a specific law, the Public Television Act,2 and the creation of a new terrestrial channel, the Public Television Service (PTS), which on July 1st, 1998, aired its first program.3 During these 20 years of existence, started paradoxically in the middle of a global environment “dominated by a swelling chorus intoning the last rites for public service broadcasting” (Murdock Citation2005, 213; Tracey Citation1998), PTS had to face some other local challenges.

First of all, PTS has tried to compete, with a small budget,4 against more than 120 TV channels, most of them already on air even before the Cable Radio and Television Act (1993); while many newcomers, including foreign channels, arrived as a result of the increasing penetration of the cable platform and the launching of the satellite platform with the Satellite Broadcasting Act (1999).5 This situation was clearly different compared with that of most of the public stations of the world, which had existed since the 1950s or 1960s in a system of monopoly—obviously with high ratings—and then after a certain point, the State opened access to private channels.6

Second, PTS was born in the middle of the digital transformation process, and the subsequent switch off—imposed by many governments around the world—of the analogical signal (in Taiwan, starting in 2004 and ending in 2014). This meant a huge economic and human effort, but made PTS one of the world pioneers in developing the High Definition signal (the first transmissions became reality in 2006). More recently, in 2016—ahead of many other networks in the world—it initiated its own 4 K (Ultra HD) program of experimental productions and broadcastings (Public Television Service Foundation – PTSF Citation2016, 5).7

Last, but not least, PTS has had to fight intensely—like the majority of Public TV channels in the world (Sarikakis Citation2010)—to defend its independence from the pressure of the different governments that have been in power since its birth (Tsai Citation2016, 122): the Nationalist Party (also known as KMT or Kuomintang Party) and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). The first one, inheritor of the charismatic leader Chiang Kai-shek (1887–1975),8 was already in power during the long gestation of the PTSF, and would remain in charge until the second free presidential elections of 2000.9 With the new century arrived two terms of the Democratic Progressive Party (2000–2004, and 2004–2008), governing in minority and finishing in a judicial process of scandals and corruption, involving the President in charge, Chen Shui-bian, who was put in jail. He and many others in his party claimed that the main reason for the condemnation was his criticism of China and advocacy of Taiwan’s independence (Tania Branigan, “Taiwan court jails former president for corruption”, The Guardian, September 9, 2009). The Nationalist Party KMT won again the elections of 2008 (together with the other Parties forming the Pan-Blue coalition) and repeated its victory in 2012. But in 2016 the power went once more to DPP and its affiliated parties (the Pan-Green camp). For the first time in China, a woman, Ms. Tsai Ing-wen, was appointed President. And it’s not a coincidence that her political message has always revolved around the differences with the “Mainlanders” (Tom Phillips, “Taiwan’s new president Tsai Ing-wen vows to reduce dependence on Beijing”, The Guardian, May 20, 2016).

2. Taiwanese identity: a shift from politics to cultural issues

Actually, during all these years of the democratization process, the most recurrent issue at the political level has been the relationship with the PRC and the singularity of the Taiwanese identity (Fell Citation2011; Tsai Citation2007, 30), making difficult to realign those two political coalitions around a right-left spectrum typical of mature Western democracies, where economic, social and welfare issues determine policy agendas in election times (Shubert and Damm Citation2011, 7). The Democratic Party (DPP), from the beginning of its existence (1986), firmly rejects the idea of the union, and some of their recent partners in the Pan-Green camp would willingly declare independence openly, risking heavy reactions from the Mainland. Others, at the top of DPP, have insisted in the “four No’s” principle: No to declare independence formally, No to organize a popular referendum about the issue, No to change the name ROC to ROT (Republic Of Taiwan), No to the “one State” [with Mainland] concept (Paoluzzi Citation2012, 124).

On the other side, KMT has frequently encouraged strengthening ties with Mainland under special conditions, although lately some of the Pan-Blue camp prefer not to mention the subject, because they know that ordinary people, in the end, feel themselves (sometimes because of their parents) to be Taiwanese or— especially around the administrative elections of 1998—“new Taiwanese” (Tamburrino Citation2001, 100), and that when asked, they are happy with the present status quo (Corcuff Citation2011). As a consequence, according to Shubert and Damm (Citation2011, 228), many supporters of the Blue camp “acknowledge the existence of a Taiwanese identity as distinct from a mainland China identity”.

The reasons for this majoritarian feeling are numerous, but should be found, in the first place, in recent history. The beginning of the issue is commonly placed in the 50 years (1895–1945) of occupation by Japan, which required a total submission, and included the imposition of Japanese language and traditions (Hung Citation2011, 188–243). Later on, when the authorities of mainland China, at the end of WWII, were called by the final pronouncement of the Allied leaders in Postdam (July 26, 1945) to came back to the island and retake power, they were received with great joy by locals, but “it soon became apparent that Taiwan was to be treated as a conquered territory, and its population as a subjugated people” (Hung Citation2011, 247). Indeed, “expectations that the new Chinese rulers would create a more equitable society, in which ethnic identity would not be a barrier to social advancement as it had been under Japanese colonial rule, were short-lived” (Heylen Citation2011, 17). Few Taiwanese were called to occupy decisive posts in the local administration or government (many arrived from Mainland to that function) and so, after a short time, in 1947, the social pressure exploded in a highly violent event, popularly known as “the February 28 Incident” (or “228 Incident”): hundreds of Taiwanese were killed—by armed military patrols—while protesting against the economic restrictions and civil repression; many others were arrested and executed in the following months, on charges of “high treason”.

The experience of political subjugation and suppression was perpetuated under the authoritarian KMT-rule of the so-called “White Terror”, more or less the first two to three decades of the long Martial Law (1949–1987), with 2000 executions of suspected political dissidents and 8000 sentences to long prison terms (Fleischauer Citation2011, 34). There were other cases of oppression in that period of Martial Law, like the “Free China Journal Incident” in 1960,10 or the “Formosa Incident” in 1979,11 but “the 228-Incident today is still very much alive in the collective memory of Taiwan (…). In its role in the construction of a Taiwanese national identity, 228 can certainly be considered a collective trauma” (Fleischauer Citation2011, 45).

According to Tsai, after the years of “Military Confrontation” (1945–1970), Taiwan started a different period of “Competing for Constitutional Legitimacy” (1971–1986), clearly distinguished in the process of configuration of the Taiwanese identity:

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) was formally admitted to the United Nations (UN) in 1971 and replaced the Republic of China (ROC) as a permanent member of the Security Council and the only official representative of “China” in that body. When the United States of America (USA) established formal diplomatic ties with the PRC, the mainland government officially began to refer to Taiwan as a local government of China. (…) A number of activists and intellectuals started to express public dissatisfaction with the identification of Taiwan as part of “One China,” and the independence of Taiwan was for the first time raised in public discussion. Although the tension across the Taiwan Straits seemed to ease somewhat in the 1980s, both sides of the Straits still held a great deal of hostility toward each other and had few if any political contacts with one another. After the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was established in 1986, diverse interpretations of “national identity” began to appear in public discourse (Tsai Citation2007, 6)

From 1987 to 1999, there was a “Cross-Strait Interaction”, a period in which the authorities on the island “adopted a policy to allow mainlanders in Taiwan to visit their relatives in Mainland China, and then further extended it to trade and educational exchanges” (Tsai Citation2007, 7–8). In his study, the same author tackles different aspects—not only political—especially ethnic issues and other domestic circumstances; as a conclusion, he underlines that “political, cultural, and social factors are the three forces that have shaped Taiwanese identity” (Tsai Citation2007, 28).

Actually, there are many authors (mentioned by D’Andrea 2012, 22–23) for whom the political identity of a nation resides mainly in the cultural substrate and in the dynamics it generates.

The concept of culture is however very broad, as pointed out by O’Callaghan:

It expresses and communicates our identity and that of the people we interact with. It is what we have in common; infact culture is what makes the ‘we’ possible. (…) In many ways modern culture is an elevated, sophisticated one, containing a great variety of precious anthropological insights and strengths, with a surprising adaptability and openness to absorb, to clarify and to unite (O’Callaghan Citation2017, 25–26 and 37).

Etymologically, as explained by the philosopher Llano, that concept includes all the spiritual dimensions frequent in the anthropology studies:

It seems that the term culture comes from an agricultural metaphor. The land can be cultivated or remain uncultivated. Culture is, then, care, cultivation of the spirit, which constitutes the most radically human dimension of man. It is not strange that the highest, and perhaps the most usual, application of the word worship refers precisely to the veneration of God and, in general, to the divine (Llano 2004, 16).

Indeed, this intimate union between culture and religion is unavoidable from the point of view of anthropology. According to Porcarelli (Citation2002), a double aspect must be taken into account:

There is a convergence on a personal and existential level between religion and culture, inasmuch as culture, in its different expressions—such as art, theatre, literature and the activities of the spirit in general—(…) is historically structured around questions of an existential character, and therefore essentially religious (…). Second, studies of the sciences of religions highlight the strongly cultural characteristics—social, ethnic, anthropological, rituals—of the various religious beliefs and customs, which of the culture of a people end up constituting its own historical memory (Porcarelli Citation2002, 1212).

Even for UNESCO (Citation2002, 4), “culture should be regarded as the set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features of society or a social group, and that it encompasses, in addition to art and literature, lifestyles, ways of living together, value systems, traditions and beliefs.”

Regarding PSB and its cultural mission, Jauert and Lowe add a peculiar dimension:

PSB has an historic and still valid mission to nurture national cultures, something of keenest relevance in view of globalization. But it is far from certain what the national in culture really means today, or ought to mean. (…) The public typically expects their domestic PSB companies to reflect and support shared national cultural distinctions. The dilemma lies in how to work within broader borders but with finer nuances (Jauert and Lowe Citation2005, 15).

In the case of Taiwan, and especially since the 1990s, although the study of the cultural development is quite difficult (Winckler Citation1994, 22), it’s been proved that the issue of identity has been less concentrated in political aspects during election campaigns, leaving room for other aspects—mainly cultural or multicultural—that awaken the interest of the citizens (Corcuff Citation2011, 124; Fell Citation2011, 94).

For Heylen, the whole process of democratization has gone “hand in hand with the active promotion of the creation of a Taiwanese identity by stressing cultural heritage and historical tradition”. She proposes to tackle the question of Taiwanese citizenship from a psychological point of view, because this “feeling of belonging often goes with a certain kind of imagery, which is crucial to finding and moulding one’s relationship with culture and community. Generally speaking, in their cultural planning, state agencies create the social environment that generates this feeling of belonging” (Citation2011, 16).

3. Hypothesis, methodology and sample survey

Starting from that idea, and some other readings about “direct or indirect cultural policies” (Winckler Citation1994, 23) and “national or post-national identity” (Price Citation1995, 40), my hypothesis is this: PTS channel has been one of those “state agencies” that may have contributed to form a social/cultural environment—or psychological feeling—of Taiwanese identity, independent from political ideas.12 Its creation in 1998, only 2 years after the first free presidential elections (1996) and the frequent declarations of its cultural Mission in its official documents, is the starting point for the research. The first question which arises is the following: Could be said that PTS has been determined, from the beginning of its existence, to promote Taiwanese identity through its cultural transmissions? Other interesting objectives invite the researcher to explore: Is it possible to find traces of those issues in its programmes, especially in those transmitted in the beginning of the twenty-first century, in which the society was being depoliticized and acquiring more cultural content? (Corcuff Citation2011). Could be said that documentaries on that TV channel were one of the main audiovisual genres able to convey those cultural values? Are there any typical issues more connected with Taiwanese identity that can be found in a qualitative selection of documentaries from those crucial years? And is it possible to find some patterns in the audiovisual configuration of those issues? (Yin Citation2011, 190).

This is a thematic analysis, based on a qualitative methodology. The principal aim is to discover the main cultural issues that appear in a selection of documentaries and to describe briefly their audiovisual configuration. The reason to choose only documentaries, apart from the difficulty of taking into consideration a sample survey that is too broad, is because I agree that genres are relevant for a definition of PSB (Iosifidis Citation2007, 34) and the documentary is one of its most typical audiovisual genres (Jakubowicz Citation2010, 15). Also, because for the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO Citation2001, 24 and 28) is clear that cultural values can be promoted very effectively mainly by programmes such as documentaries.

On the one hand, documentaries are connected to real life, and viewers usually agree that they can be used for general information, educational purposes and cultural enlightenment (Kilborn and Izod Citation1997, 175–180). Moreover, PTS itself considers that documentaries are an important genre to be proud of, and should be present in international festivals: “Documentary programs have always been the strong point of PTS” (PTSF, Citation2007, 17).13 And it can be said that this trend is still important in the institution, since its current President, Wen Chieh Tsao, appointed in 2016, is a film-maker herself, director and/or producer of awarded documentaries.14 Also Sylvia Feng, President and CEO of PTS from 2007 to 2009, has produced awarded documentaries, among other programmes.15

On the other hand, although “documentaries can never be any more than a representation or an interpretation of events and issues in the real world” and “can never attain the level of objectivity to which they sometimes aspire (…) many viewers may be disposed to believe in the general truthfulness of the account (especially when it has the mark of some institutional authority)”; in this sense, “documentaries can sometimes be powerfully persuasive” (Kilborn and Izod Citation1997, 5). As a consequence, documentaries can be treated as texts with a message to transmit, with a significance; a documentary’s content can be codified, analysed and interpreted, both in an isolated way or as a whole, connected with the world that it reflects (Casetti and Di Chio Citation1997, 210–211).

This qualitative approach to the content of the documentaries is in line with the idea of cultural mission reflected by Bettetini and Giaccardi (Citation1997) in their study about public service in Europe during the 1990s: it is more proficient to attempt a transversal analysis, since content alone does not make culture in a communication system; what matters is the importance it has inside that system, and importance derives from style, formal aspects, capacity of giving a voice to different opinions, general attitude in front of cultural experiences, and so forth (Bettetini and Giaccardi Citation1997, 14–15).

Thus the methodology will include a brief discourse analysis (Schrøder Citation2002, 104) to discover those cultural issues—not only in the audio narratives or language (Price Citation1995, 54), but also in the images offered—and, above all, the way in which those issues are reflected (Casetti and Di Chio Citation1997, 212). In the first place, each documentary will be analysed, paying attention to some formal aspects: the modes/types of each documentary (according with Nichols 2001, 99), their narrative structure or threads, and some other interesting elements, such as music, sequences, shots, and so forth (Bernard Citation2007, 62). That peripheral description will help in understanding later the meaning of those issues and of the whole program. For example, it could be useful to know whether the selected documentaries adopt, totally or in part, the most traditional narrative style, that is to say, the “Expository” mode, characterised by the frequent presence of a voice-over commentary (usually by someone never seen on the screen), that “emphasizes the impression of objectivity and well-supported argument” (Nichols 2001, 107).16

In the second place, each documentary will be considered as a rhetorical discourse, with a main message or values to transmit, and some other secondary messages. That’s why some attention will be also given to content, but only to those issues connected with the feeling of being Taiwanese, always through the qualitative approach and criteria exposed explained by Casetti and Di Chio (Citation1997, 208). In this sense, the percentage with which some value or category may appear it is not too relevant, but rather the configuration that each singular issue is given, in order to present an (at least, apparently) efficacious way of comprehension and conviction.

For that purpose, some concrete scene or dialogue from selected documentaries may be described; nevertheless, the main significance is obtained from the consideration of each program as a whole, with an explicit or implicit intention on the part of the main author (director or producer, but also the entire PTS institution, because they are responsible for the commission or approval of the documentary). As a conclusion, a final interpretation will be attempted around the social function of those audiovisual texts, considered as mediators in the construction of social identities (Casetti and Di Chio Citation1997, 255).

Although some other documentaries of PTS will be mentioned, only a qualitative sample has been selected for this cultural investigation: a total of six awarded documentaries, among those highlighted on the PTS Annual Reports, from 2008 to 2013. I chose the first one from 2008, because that year was the 10th anniversary of PTS, and the institution probably had then reached a mature situation, after the big transformation undergone in 2006 by the Public Service in the ROC, with the creation of the new structure Taiwan Broadcasting System (TBS) and the entrance of other official channels.17 The last documentary, from 2013, responds to particular historical events that occurred in 2011 and 2012, which deserve a brief explanation.

On the one hand, 2011 marked an important event in the history and the feelings of the viewers of PTS, being the 100th anniversary of ROC Taiwan.18 It was a strange occasion, since the proclamation of the Republic of China, on 11 October 1911, was made on the Mainland. That day marked the beginning of the military Wuchang Uprising (aka the Xinhai Revolution), with the collapse of the Qing Dynasty, thus ending thousands of years of imperial dynastic rule. And so, logically, those who most wanted to celebrate were the members of KMT (at that moment in power), less favourable to the independence of the island, and knowing—ironically—that on the Mainland nearly nobody was celebrating, apart from President Hu Jintao and other political Chinese leaders inside an Auditorium.19 But the fact is that the events of that year, for different reasons among parties and communities with diverse ideologies, saw an upsurge of the feeling of the Taiwanese identity: the National Day celebration, or Double Ten National Day (Davison and Reed Citation1998, 53), with the usual military parade—for the first time, in 2011, with a paratrooper show—attracted thousands of people, but also awoke odd sensations in many other Taiwanese citizens.20 All these events were broadcasted on PTS in HD video quality (PTSF Citation2011, 37). It is a fact that documentaries made or commissioned around that peculiar anniversary were aired or awarded in 2012 and 2013 too.

On the other hand, in 2012 there was another event that affected PTS: the Ministry of Culture in ROC Taiwan was founded (see “New Ministry of Culture opened”, Taipei Times, 22 May 2012). According to Tsai, from that moment on, PSB in Taiwan “has been governed by the Ministry of Culture. This puts PTS in a core position for cultural policymaking and that is promising for needed development in Taiwanese democracy and cultural citizenship” (2016, 122). Since the process of adaptation was long—“it took nearly 1 year to reorganise the new TBS’s Board of Directors” (129)—it is reasonable also to consider 2013 as a period in which PTS forged a new cultural audiovisual production to deliver to Taiwanese citizens, and as a kind of “echo” period after the Centennial anniversary (October 2011).

Within the 6 years selected (2008–2013), the documentaries highlighted in each PTSF Annual Report are around four per year. The selection of only one per year was guided by another qualitative criterion: it was based on the number (and quality) of awards; all the documentaries selected should have been awarded, or at least selected, by some international festival, so that—automatically—only those with English language, at least in the form of subtitles, have been included. In the case of doubt about the awards, another secondary criterion was the close relationship of the title of the documentary (and/or its declared content) with the values mentioned in researches about specific cultural studies in Taiwan, like Moskowitz (Citation2011), Hsiau (Citation2010), and Davison and Reed (Citation1998). The attempt was made to choose mainly home-produced documentaries that were also awarded at international festivals. In the case of co-productions or commissioned programmes, it is understood that PTS had a voice in the control of the production—or the technical direction—and they considered it a programme worthy to be shown it to the world.21 Obviously, programs purchased abroad and aired on PTS are excluded, since “public broadcasters must first promote the expression of ideas, opinions and values current in the society where they operate” and, in this regard “it is of foremost importance to give priority to national programs” (UNESCO Citation2001, 20).

For that discourse analysis, it is necessary to study the social context, according to the requirements of a thematic-qualitative methodology (Schrøder Citation2002, 109; Jensen and Jankowski Citation1993, 7 and 95; Dijk 1991, 117). Besides, as explained by Bettetini (Braga and Fumagalli Citation2017, 93): “Meaning [in cinema or television programs] is not created only by the images, the content, the sounds, the words, but also by the time in which the audiovisual offering occurs.”

I consider that the main part of the general context was sufficiently tackled at the beginning of this article, while describing the political-historical situation of Taiwan, connected with the democratization process and the conscience of national/cultural identity. Other references to the context will be made during the analysis, especially those connected with the PTS institution itself, mentioning its foundational documents (taken from the institutional web page or the PTS Annual Reports). Furthermore, some specific context will be explained whenever a documentary requires, adding aspects that directors have not introduced in their story.

3. Analysis of a PTS documentaries selection

As said, documentaries are always present in the scheduled programming of PTS.22 Actually, in the annual breakdown by content of the channel, documentaries often amount to 10% of programming and sometimes even exceed 11% (PTSF Citation2008–2013). Based on their descriptions, they deal with many cultural issues mentioned in the Mission and Vision declaration of the PTSF, from the first years of its existence. For example, they “promote the development of society”, “record important national historical events and viewpoints”, “introduce the rich cultures of various ethnic groups in Taiwan”, “increase our nation’s understanding toward our own and other’s countries cultures” or “help the international community to understand more about Taiwan’s culture and its people” (PTSF Citation2001, 14).

Here I will try to focus in the themes more related to culture, in the wake of that psychological feeling of Taiwanese identity, suggested by Heylen (Citation2011, 16).

Other analyses of documentaries produced in Taiwan have been already done, like Boscarol (Citation2018), or Lin and Sang (Citation2012), but with different perspectives and methodologies. The first one deals with Taiwanese identity—an issue “in constant transit”—and examines some recent independent documentaries (mainly those that represent history) through the use of archive materials and experimental texts and poetry. The other authors cover a period of time prior to 2008 and are not focused mainly in PSB production either, although sometimes they mention it, and are aware of its importance:

Several factors have contributed to the growing popularity of documentary film as a creative, artistic project and as a form of entertainment. The launch of the Public Television Service has provided funding and screening venues for new documentary films; the biennial Taiwan International Documentary Festival has offered unknown filmmakers an opportunity for recognition; and the inclusion of documentary filmaking in the education system has helped [to] produce a new generation of young documentarists (Lin and Sang Citation2012, 2–3).

I think that a selection of only institutional documentaries in reference to national-cultural identity of an island that by many is considered a new country, can produce more fruits because, in agreement with Jauert and Lowe, “Public service broadcasting (PSB) has been mandated with a cultural mission from its inception. (…) In its inaugural period, a cultural mission for broadcasting was part of the social agenda. That mission was defined in ways that were characteristically nationalist” (2005, 13). Moreover, “PSB has greatly contributed to the quality of public discourse, the average standards of knowledge capability, and appreciation for the riches of cultural heritage” (18).

Following is the analysis of the six documentaries selected, taken one per year in the period 2008–2013 and with the criteria mentioned above.

3.1. Spirits of Orchid Island (Nick Upton, Wen Cheng and Shuwa Chang, 2008)

This documentary (53 min), produced in 2007, was aired on 24 May 2008 (PTSF 2008, 23) as one of those programmes in preparation for the 10th anniversary of the channel (PTSF 2007, 17). It is the first PTS documentary made in HD video quality (and Digital Dolby 5.1 Sound). It was selected by more than 10 international festivals, winning the following Awards: Environmental Sustainability at the Earth Vision Festival (USA, 2008), Envirofilm Festival (Slovakia, 2008) and Ecofilms, Rodos International Film & Visual Arts Festival (Greece, 2008).23

It was an international co-production, with which “PTS established mature production procedures for HD programs, transferring foreign production techniques and cultivating local professionals” (PTSF 2007, 17). Directed by Nick Upton, a senior British director, it portrays the wildlife ecology and unique culture of the Tao tribe (PTSF 2008, 23).

Also known as Yami, specially by Japanese, Tao people are from Austronesian descent, and arrived to Taiwan from the Philippines. Numbering around 4000 people, it is today the smallest aboriginal group of Taiwan, and can be found only in Orchid island.24 Known also as Lanyu or Hong Tou Shu or Botel Tobago, Orchid island is the largest of the 13 small isles around Taiwan. It is placed at 90 km south east coast of Taiwan (Hung Citation2011, 31–36).

The HD video quality of this documentary helps to display the profuse ecosystem and spectacular natural landscapes of Orchid Island, enriched by music from the Canadian Matthew Lien, who “applied his long-term experience working with Taiwan’s indigenous musicians to successfully create convincing background music representing the oceanic culture of the Tao tribe.” On the other hand, “an internationally acclaimed writer, Syaman Rapongan, represented the Tao tribe to make this story persuasive” (PTSF 2008, 23).

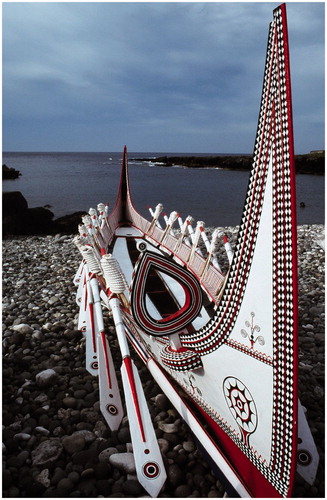

Indeed, the narrative thread of this documentary, pretty obviously (Bernard Citation2007, 42), is that of Syaman: a long interview with him—recorded probably on different days, because of his different clothes, and in several different places, mainly close to the sea or in the forest—together with the presentation of the actions he is doing: cutting a tree, visiting relatives, and so forth. He is a kind of leader, nephew of an elder tribe chief, who taught him—together with his father, he says—to construct wooden dugout canoes (see ) with which his people used to fish. Syaman provides a credible testimony, by his mature appearance and wise words, but also because viewers can see him doing the actions he tells: working skilfully on the wood, visiting elders and explaining the beliefs and traditions of the tribe. Very often he appears on camera, sitting down in a medium shot, and many other times walking; in other moments, his voice can be listened on the background while others are working, fishing, and so forth. Actually, there are few “talking heads”, because even those sitting-shots, after a few seconds, are frequently covered by relevant auxiliary images (B-Roll), and a couple of times from archive images (some traditional feasts that are narrated by Syaman, like the ceremony for launching a big painted plank-boat), which contribute to the credibility of his assertions.

His voice is alternated with another one, from a professional speaker: a neutral “voice-over”—the speaker is never seen on camera—that “proposes a perspective, advances an argument, or recounts history”, typical of the documentaries from the “Expository” mode” (Nichols 2001, 105). The tone is a bit solemn and didactic, but well-thought out in order to carry out the narration. For example, at the beginning, while hundreds of animal species– including fish and sea-snakes–are being shown, the voice says:

Orchid Island’s warm tropical waters sustain over a thousand kinds of fish. But this is not a deserted paradise. A very special people, the Tao, have long harvested the ocean using hand-made boats. Their culture is now threatened, but many spiritual beliefs and links with nature, survive.

One could say that there are typical moments of the “Participatory” mode too, because there is a live interaction with the subjects (Nichols 2001, 116), although no one from the production crew is ever seen or heard. But watching some shots, it is clear that the camera operator travels with the Tao in the canoes, sometimes even records them from the above over the sea, with an evocative sound effect of the oars or the nets dropping into the water. And of course, there are many shots recorded very close to the animals, both underwater and on the surface. Those natural moments are alternated with the pieces of Syaman’s interviews, as a kind of time for relaxation. Some of them are even related to traditions and beliefs too, like the prohibition—by the elders of the tribe—to shoot some kinds of fishes with the harpoon, because of their evil spirits.

In some way, I find some similarities between this documentary and the first produced in history, Nanook of the North (directed by Robert Flaherty, Pathé, USA-France, 1922). This one was silent, but—as it was often used in the past—it included intertitles that worked like a virtual narrator, or put some words in the mouth of the main character. Wisely, Flaherty decided to tell the life of the Inuit tribe, taking only one of them as a protagonist. Moreover, he asked him to make a walrus hunt in the traditional manner, with a harpoon, to record it on camera. In reality, as Flaherty declares in his diary, all the Inuit used the rifle at that time (Barnouw Citation1993, 37). The building of an igloo was also another celebrated sequence in that film, but the interior was found too dark for photography, so half of the igloo was sheared away (38). Also in Spirits of Orchid Island the director chose only one person to follow (Syaman) and concentrated attention on the fabrication of the wooden canoe (cutting trees with an axe, though many use a chainsaw), the traditional way of fishing (when, in reality, most of them currently use the motor boat) and the importance of wooden houses, built largely below ground to avoid the worst of typhoons (although there are many others houses in the island, quite modern, built in concrete).

Actually, the public modern houses, promoted by the central authorities of Taiwan, are shown at the end of the documentary, to illuminate the contrast with living in total contact with nature. Also the polemic aspect of the nuclear waste present in the island, is shown—and underlined by the voice-over—only at the end (min 50): “Taiwan has used Orchid Island as a nuclear waste dump since 1982, and despite many protest, the storage site remains”. Indeed, in 1982 the storage facility was completed, and about 98,700 barrels of nuclear waste from the nation’s three operational nuclear power plants were stored at the Lanyu complex. Protests against it to the authorities of Taiwan have been frequent (Loa Iok-sin, “Tao protest against nuclear facility”, Taipei Times, 21 February 2012) but the answers are always a vague promise to solve the problem in the future (Matthew Strong, “Taiwan to complete repackaging of Orchid Island nuclear waste in 2020”, Taiwan News, 13 October 2018).

In this sense I find that this documentary has a charge of “Reflexive” mode (Nichols 2001, 125), or even has an “Advocate” function (Barnouw Citation1993, 85). Not only because of this issue, but also in general: listening the customs, taboos and creeds narrated by Syaman or the narrator, most of them connected to respect for the forest or for animals, the reaction intended in the public would be a reflection about its own convictions and the respect for the nature that they will leave to future generations. For example, when Syaman is cutting trees, he explains that nobody in the island takes more than one to two trees from the same place. When he is finishing the cut, the narrator adds: “And every tree deserves a prayer” (in that very moment, his cousin, who is working with him, looks at the ceiling in an attitude of prayer).

Another implicit reflection is the general relationship between the Tao and the authorities in Taiwan, and the mediator role of the PSB in that conflict, as declared in one of its official mission statements mentioned above. Clearly the channel, as an institution, wants to help the viewer to think about real respect for other ethnicities that should be based on facts and not on words.

Nonetheless, the intentional messages are generally mentioned with moderation and objectivity by the speaker: “Tao culture has changed much under Taiwan’s rule (…). The island is becoming modern. New constructions with concrete (…) symbolise a loss of culture to many elders”.

Even though the documentary includes several balanced points of view, some big complaints are selected from the interviews. For example, the elder of the tribe says:

The Taiwanese have entered our island. Foreign cultures seem to be destroying ours, so I’m heartbroken. Today our village has only one big boat left and it’s lonely on the beach (…). Young generations should respect the Tao gods of mountains and forest, our flying fish and sea bottom fish. All of these form the Tao’s core values.

To sum up, there are abundant cultural issues in this documentary: the peculiar nature environment of Orchid Island should be protected (ecology), also because it is a unique atmosphere with unique animal species (Scops Owls, Whistling Green Pigeons and Magellan Birdwing butterflies) and coral shore lines. Young generations should respect traditions and elders (watching the sea very often, as it provides wisdom; community religious ceremonies to launch a new boat, to honor its spirit, or to start the times for harvest and fishing); everybody should respect other ethnic identities (including their language), and spiritual beliefs (flying-fish as a kind of deity). There is also a feeling of community, mentioned by both the speaker and Syaman: it is important to work together, celebrate feasts or share the food with relatives and friends (generosity).

Finally, it may be interesting to underline, with a couple of spoken examples, those cultural values and the main message that this documentary contains, seen as a rhetorical discourse. It happens in the last 2 min. After speaking about the responsibility form forming the younger generation, sitting in the limits where the forest becomes the coast, in a medium shot, and with the later apparition of nice images with people rowing in colored canoes and many other having fun on the beach, Seyman says:

That’s why I am living in this island. I learn from my people the harmony between humans and nature. But this kind of wisdom does not form easily, and it’s something for my people to be proud of in today’s world. You must learn to have less desire to plunder nature. Then we’ll have somewhere pleasant to live.

And the voice-over concludes, with a rhythmic background of music performed with flutes and bamboos and bongos:

The future of Orchid Island is uncertain, but the Tao’s pride and belief in old traditions may prove crucial. For now, their unique respect for the sea, for the island that nurtures them and for the spirits that watch over them, lives on.

3.2. Bird without Borders (Dean Johnson, Leh-Chyun Lin and Selena Tsao, 2009)

This HD documentary was aired on 11 June 2009. It is an international co-production (with InFocus Asia Foundation) that lasted 1 year and a half of planning and filming in over five countries, to record the magnificent transnational migration of Black-faced Spoonbills (see ) which is the subtitle of the documentary. PTS produced the Mandarin, Taiwanese, and English versions. The founder and artistic director of the Cloud Gate Dance Theatre, Huai-min Lin, was invited to be the Mandarin voice-over. To give the documentary a more regional flavour, the Taiwanese voice-over was by Chiang Lin, a music composer (PTSF 2009, 21–22). The program was selected by more than 10 international festivals, winning these awards: Gold Remi for Nature/Wildlife of TV&Cable Productions, WorldFest Houston Film Festival (USA 2010) and Special Prize for Biodiversity, Earth Vision (Japan 2010).25

Regarding the type of documentary, it can also be categorised into the “Expository” mode. Indeed, there is, on the first place, a voice-over of the narrator—never seen on camera—quite didactic and sometimes solemn: “This is a story of a promise to return”; “Development is the greatest threat to the last remaining…”; “Disturbing nesting birds can be stressful to both parents and young”.

On the other hand, the five interviews registered (with a forest guard of Tainan, a young graduated ornithologist, a University Professor in Japan, an employee of the Tama Zoo, and a professional bird photographer) are dynamic, recorded not as a boring “talking-head”, but while walking, working or doing something else. In the editing process all the questions of the journalists were cancelled, and interesting auxiliary images (B-Roll) added, which give credibility and spontaneity to the assertions that they offer, even being educative. For example, when one of those birds that has just broken the shell of his egg, in the Japan university laboratory, suddenly appears and looks awkwardly into the camera, while pleasant music is playing in the background, the Professor says with emotion, taking him with care in his hands: “A baby black-faced spoonbill, with the pink fur! (…) Well done, you’re a healthy one”.

In this sense, one could say, again, that there are typical moments of the “Participatory” mode, because there is a live interaction with the subjects (Nichols 2001, 116), although no one from the production team is never seen or heard. It calls to mind the documentary Winged Migration (directed by Jacques Perrin, Galatée Films, France, 2001), in which scientists healed one black-faced spoonbill, attached a GPS tracer to him and left him during the days of usual migration, hoping that he would come back after the whole cycle. But there is a big difference among those documentaries regarding the production process: in the case of the Taiwanese film the production team does not fly amidst the birds as the French team does in filming their documentary.

At the same time, during few but prolonged moments, it seems a documentary from the “Observational” mode (Nichols 2001, 109), thanks to the long natural shots of the birds flying, synchronised with a good audio natural track, recorded in Dolby 5.1 channel.

About the structure, apparently the film is a unique piece of 53 min, but watched with attention, it can be divided in six parts: a teaser-presentation (min 1–2), Tainan (3–13), Japan (13–30), Korea (30–36), Chinese Xingrentuo island (36–45) and return to Taiwan-finale (45–53). Every part contains, at least, one main interview plus people speaking among themselves, while watching birds nesting or having lunch, and so forth.

Cultural issues are distinctively conveyed. First of all, there is a huge call for ecological responsibility: those animals are in danger of extinction, and young people should be educated to take care of them; even adults should admire them (that’s implicit). Some of those interviewed have compassion for them, especially for the one they healed, tagged (“T41”) and fed, that never came back: “I really hope to see it again in Autumn.”—says the young ornithologist—“She’s like an old friend.” At the end of the documentary, when many birds have come back, she (the young ornithologist) is walking along the coast with a sad look, and we hear her voice (recorded in another moment): “I still think about T41 and wonder where she is”.

There is also clearly expressed a kind of pride about the treasures that the island holds: “It’s a migratory bird found only in this area of East Asia”, says the voice-over at the beginning. And the forest guard of Tainan: “The Taiwanese public is very proud of these black-faced spoonbills. The birds are here with us in Taiwan. When other countries talk about the black-faced spoonbill, they’ll say, in Taiwan (…). The habitat around us must be sustained. Conservation must continue”. These last three sentences could be a good summary of the documentary, taken as a discourse with a main message to transmit.

Another issue present is that of internationality; borders of the countries have to be overcome: “countries in Asia must work together and help each other. North Korea, South Korea, China and Taiwan should all get together and discuss ways to work together to save these birds”, says the professor in Japan. And the forest guard in Tainan says something very similar.

Lastly, a kind of local feeling, for the island as a special home, is metaphorically reflected in the nature and implicitly could be applied to all Taiwanese. In this regard, the words of the voice-over at the end of the documentary (while the birds are landing peacefully, with a nice music in the background) are very expressive:

It’s October. (…) At last, after 7 months in a 4000 km return journey, Taiwan shoreline widens on their sight. They have survived an epic migration across East Asia. Over the coming weeks, over half of the black-faced spoonbills population will return home to Taiwan.

3.3. Ferrying across: the Tamsui River (Li-Ping Yu, Cyu Sin Yi, 2010)

Aired on 24 May 2010, this is the first of a four-part documentary series, “Tracing the river to its source”, which examines the delicate, frequently transgressed balance between man and four river systems located, respectively, in Northern, Central, Southern and Eastern Taiwan (PTSF 2011).26

This first part (57 min) of the series won the Earth Vision Award at the 19th Tokyo Global Environmental Film Festival (Japan 2011), the Gold Remi, the Underwater & Marine Science-WorldFest at Houston Film Festival (USA 2011), and an Honorable Mention for Historical & Cultural Perspective at the Montana CINE International Film Festival (USA 2010).27

Li-Ping Yu, the author of the documentary, is a reporter of the PTS program “Our Island.” Her work Hermit Crabs in Plastic Houses (2004) was nominated in the First Green Film Festival in Korea and the 13th Tokyo Global Environmental Film Festival. She was also the producer, among many others, of Song of the Forest and Swing, both documentaries directed by Chin-Yuan Ke in 2010.

In this case, the narrative thread is the river itself (see ), the Tamsui (or Danshui). Together with its tributaries, form the Taiwan’s third largest river network. Starting from the dirty waters that citizens from Taipei can observe when close enough, for example during the annual Dragon Boat Festival, the action moves up to the uncontaminated purity of the source, beneath the cypress-topped mountains, where some indigenous people, the Atayal, used to have their home. They are the second largest indigenous population in Taiwan, distributed in the northern mountainous regions of eight counties, including Taipei. The Atayal themselves recognize that they are not good about maintaining their traditional culture (Hsieh 1994, 186–192).

Actually, the documentary doesn’t concentrate on those people or traditions, just on some of them, as characters interviewed, but dressed in modern style and doing ordinary actions: cultivating the ground, having dinner with relatives, and so forth. The real protagonist is the water: the first 10 min of the film, the dirty surface (and the bottom and the banks) of the Tamsui when crossing Taipei are portrayed; then, a long part—with some brief excursions back again to the big city—of the various sources of the river, where food harvested from the earth or from the water is unadulterated. At the end, the documentary goes back again to the garbage, to feel the nostalgia and move the public to react.

The discourse, taken globally, is strongly persuasive, and perfectly credible because of the impacting images: both the dirty and the clean ones. And also, thanks to the explanations of the 18 people interviewed, some of them former fishermen who have now become boat guides for excursionists or tourists. There are also some scientists, reservoir workers, and volunteers who clean the area or denounce the illegal discharge of various types of waste into the environment, and some others.

The mode of the documentary is basically “Expository”, with a professional speaker, who narrates in voice-over—never seen on camera—he goes on perhaps too long sometimes, but alternates often with the interviews. His assertions are balanced but full of rhetorical elements, like questions to interpellate the viewer. For example, at the beginning: “What words are adequate to describe the Danshui, this great river that has ferried us through the march of time?” Or, close to the end, in the minute 54, when viewers have come back to the ugly images of Taipei basin: “Can you remember, at her source in the mountains? She began so pure… so clean.” Another one, in the minute 30, while criticising the policy of reservoirs: “Can this really be considered a stream?”

It could be that precisely for this insistence, the style must be considered as a “Reflexive” one. But perhaps it would be better to use the tag of “Prosecutor” in the classic categorisation of Barnouw (Citation1993, 172). The present situation is someone’s fault, it seems to say: it is caused by the lack of responsibility of the citizens, and the insufficient solutions of the local authorities. The author, using the voice-over and the testimonies, gave evidence of many of the problems and keeps pace with possible objections. For example, he says that one can observe the river from the distance and think that it is more or less nice. But it’s important to get closer, because “If we don’t come to the river to see for ourselves, how can we hope to understand the damage already done?” He expresses this idea twice, and probably both times can function as the core of the discourse of the whole documentary: “From an appropriate distance, the Tamsui is truly beautiful. But her deep wounds are obvious upon closer examination.”

Cultural issues conveyed: first, clearly, the ecology and the desire for harmony with the elements of nature, which is a general Chinese value (Davison and Reed 1998, 32). The speaker himself treats the river as a “She”. And one lady says, when entering a boat: “Our slogans are river, mother and love”. This value is more or less in relationship with citizenship and solidarity. And so, there are also people in a village who protest against a possible threat (a new reservoir). One of them shouts, with a megaphone: “We shall resist. We shall protect our homes, we will maintain our sacred trust over the river.”

Religion is also present. “In the mountains, near Zhenxibao in Hsinchu County, the Dali family busily prepares for a new season’s planting. They are thankful for this land passed down through the generations. Even while planting none forget to offer up a quiet prayer”. That was the voice-over, but afterwards the idea is confirmed on camera by a resident of the place, in Jianshi Township, Hsinchu County: “With each strike of the hoe we thank the land; thanking the land and giving thanks to God. This is because of all the good that our land brings, we rely on the land for our livelihood. The land looks after us… and we look after the land.”

The ethnic issue is not important here, but at least is mentioned, as geographical aboriginal places, worthy of protection (those sacred sites for Atayal tribe, mainly). There are also some general nostalgic feelings for the past and for respect to elders, for example in the remembering of the old fishermen, when they could drink directly from the river, and the harvests were abundant (implicit: they were good citizens).

Some other traditions are mentioned: not only the Dragon Boat Feast in the river, but also feasts at family level. It is an opportunity to come back to the origins, where the water is pure, sharing a meal with grandparents and enjoying familiar aromas and atmosphere.

3.4. A Year in the Clouds (Dean Johnson, Frank Smith and Selena Tsao, 2011)

This documentary, a co-production of PTS and IFA Media, was aired on 30 June 2011. It signed a record of awards in the history of the channel (PTSF 2011, 11): among others, Peabody Award (USA 2012); Best Indigenous Native People Document & Honorable Mention for Educational Value at the Montana CINE int’l Film Festival (USA 2011); Asian TV Awards-Nomination for Best Documentary Programme, Best Cinematography, Best Direction (Singapore 2011); Winner of Peoples & Places Category, CINE Golden Eagle (USA 2011); Silver Medal for Environment & Ecology Category, New York Festivals (USA 2012); and Gold Remi Winner of Documentary, WorldFest Houston Film Festival (USA 2012).28

All these awards seem well deserved, because of the excellent quality, both technical and narrative, of the film. During 85 min of High Definition video, recorded with several cameras (including cable-cam aerial technology), the viewer is taken high into the mountains of central Taiwan, into the village of Smangus (the name is the subtitle of the documentary), inhabited by a group of Indigenous people, the Atayal (see number 3.3 here) and surrounded by astonishing flora and fauna (see ). Twenty years ago, the tribe was amongst the poorest on the island, many were forced to seek low paid labor in the cities, but the chief, Icyeh Sulung, discovered great trees that would ensure the tribe’s survival. The rare Chamaecyparis formosensis Matsum forest is estimated to be more than 2000 years old, and the interest from visitors turned Smangus into a prospering eco-tourism center. It’s the only place in Taiwan that now practices common ownership of land and property.29

The narrative thread of the documentary is the calendar. The filming occurred during 15 months, and the editing process has managed to transmit the sensation that one is watching a whole year in the life of that people, feeling with them the changes of seasons: as spring comes to the mountains, the chief is diagnosed with lung cancer, whilst a small group from the tribe rejects the communal system and tries to build a competing tourism business. By summer, a baby girl is born to the tribe, and by the time of the harvest, in Autumn, a wedding takes place. By winter, the viewer has experienced every dimension of the life of these people, and their bonds with the forest surrounding them (PTSF 2001, 11). The documentary finishes in December, with some of them visiting the chief’s home, to sing with him Christmas carols.

The narrative mode chosen is not “Observational”, like documentaries from the American Frederick Wiseman or the French Nicholas Philibert; nor “Participatory”, typical of Anthropological documentaries, like My Year with the Tribe (directed by Will Millard, BBC, UK, 2018). Alternating with the Smangus people’s contributions, there is sometimes a voice-over explaining their life and traditions. So the style is basically “Expository”. But there are plenty of interviews and, more frequently, spontaneous declarations or actions of people from the tribe. As a consequence, the style is a mixture of the three modes, with a low presence of voice-over. When it intervenes, it’s quite descriptive, narrative or even journalistic, although a few times becomes didactic or predictable. For example, just after the birth of the baby (she is in the arms of her mother, now happy, after the hard pains of childbirth): “One day she will be a wife and a mother, ensuring the tribe doesn’t die.”

Cultural issues conveyed: the main one is probably the respect—or even love and admiration—for their own ethnic traditions as well as for other ethnic traditions. The viewer should arrive to that conclusion, after watching the attitude of the Smangus, with the sympathetic configuration offered by PTS producers and director.

This feeling is connected with the love/harmony with the nature typical of Chinese mentality, but even more accentuated in Taiwanese culture (Davison and Reed 1998, 32–33); that is love for their own land too. This can be observed in some scenes commented by the voice-over: during the scene of the millet harvest, it says: “It is a crop that symbolizes the tribe’s bond with the earth and the spirit around them”. But it’s expressed mainly by the members of the Atayal tribe: “These are our lands. Our ancestors left us this land. We have to make the most [good] use of it, to pass it on the next generation”. Particularly significant are the two sequences of children going out to the forest, accompanied by adults, to be taught about the traditions of the ancestors, listening the sounds of the birds, and so forth. When they arrive to the place, which is also an attraction for the tourists in other expeditions, one of them declares with emotion: “This is our mother cypress trees. Look carefully and don’t forget.” Then, he complains about some other trees that have been cut illegally and badly damaged, to obtain a bunch of money. “Although they get rich, life will punish them”, he comments. In other similar occasion, they represent a kind of ceremony to enter adulthood in the forest. The youths are dressed in tunics and headbands, and each one receives a knife:

This hunting knife is inherited from our ancestors. It’s an essential survival tool. When you go hunting in the mountains, don’t kill everything. Don’t take all animals back. Our ancestors said to only take what you need.

Afterwards they come back to the village, singing happily a tune from their own tradition: “My Tayan children. Work hard and be happy. The land is not big enough for us to live in. You hike along the river over the mountains.”

Another big cultural issue observed is religion. They pray daily during the first general meeting in the morning, guided by the chief, but also very often in other moments of the day. Usually they express their beliefs on camera, a mixture between Christian faith and beliefs from their ancestors. For example, the documentary includes two animal sacrifices. One of them not seen but announced: “We are slaughtering one head of cattle as a gift to God. We want to commemorate our ancestors too.” In the other one, performed by the grandmother in charge of the school, she introduces the ceremony:

We thank you God for this new beautiful day. You are the ruler of the Universe. We are here with all the village children to teach them our ancestors’ culture. May you bless everyone with a new life and strong body.

Then she explains the sense in an interview in front of the camera:

We perform a ritual and we sacrificed a chicken. We smeared its blood over the seeds of the crops. Our ancestors told us we should give respect to the spirits of our ancestors and the earth. If we do this, the spirits will bless us with an abundant harvest.

Other moments of prayer take place during and after the abundant harvest, or in the school, to “pray the Lord Jesus for the illness of the chief”. And, more institutionally, there are two ceremonies inside the Presbyterian church, guided by the priest of the village, with long and emotional scenes presented.

Other secondary themes conveyed in the documentary are the following (a few of them implicit): the importance of teamwork; dialogue to avoid conflicts and promote solidarity; the sense of community; the secondary role of money; the significance of living simple lifestyles, with time devoted to the family; the respect for elders; the appreciation of women’s worth; the value of human life.

As per the main message taken as a discourse, the synthesis in this case is difficult. It might be summarized by the statement of a youth at the end of the documentary, during Christmas, who says to the camera that he is very happy, because he will become a father in few months, and feels like a “real man”. He works in the manage office of the tribe, but sometimes appears helping the adults in teaching, even at school. He is aware of the delicate moment, in which the leader is close to death (in an interview in front of the camera he gets very emotional). Now, considering it as a possible synthesis of the documentary’s message, he declares: “We aim to pass down the traditional culture to the younger generation. Hopefully they will remember it and help to pass on our ancestor’s culture”.

3.5. The 6th Sense (Elmar Bartlmae, Bessie Du and Jessie Shih, 2012)

This documentary (52 min) was aired on 3 March 2012. It was a co-production with Leonardo Film Production (Germany) and WDR, ARTE, and LIC. Winner of First Prize in the category of Education and Science of the 16th China Programme Exhibitions Awards (2013). It’s also known (with small variants in the final cut) by the title Earthquake Snakes. Animals and the Science of Earthquake Prediction (46 min).30

The director is the German Elmar Bartlmae, who interviewed scientists of various fields in search of scientific evidence of earthquake prediction by animals, for example, snakes (see ). The production was shot in Japan, the US, Taiwan, Italy, China, and Germany. This variety of geographical settings make this documentary less significant than the rest for this research. However, some aspects of its style and content can be highlighted.

Regarding the mode, it’s “Expository”. There is a voice-over, very journalistic (sometimes didactic, but not persuasive, except at the very end of the documentary, to transmit the final message). It contains also interviews with more than 20 professors of Seismology, Zoology, Geophysics, or Astrophysics. Nearly all of them appear in the modality of talking heads, but sometimes they are shown speaking while doing experiments in the fields, graphics on the computer, while standing behind a fish tank, and so forth.

Concerning cultural issues conveyed: the main one is the use of science at the service of society. Connected with that, it is cooperation among different countries to pursue that goal. In that sense, it’s interesting to see how the public channel has made an effort to show that Taiwan itself is one of the international partners. Indeed, three Taiwanese scientists are interviewed: Jen-Hung Cheng, Geographer (min 3–4); Chien-Hsin Chang, Geophysicist (min 13–15), and Jann Yenq Liu, Astrophysicist (min 47–49). The last two, were recorded in the middle of their work, allowing the viewer to think that it may be a key piece in the achievement of the global discovery.

This fact is in accordance with some of the missions mentioned in the institutional documents. For example, inside the “TBS vision for 2011-2013” (PTSF 2012, 2) these sentences are found:

Taiwan Broadcasting System will remain dedicated to producing quality and professional programming, developing new media platforms, and promoting Taiwanese values (…).

Becoming a Valued Medium Trusted by the Public (…) Connecting Taiwan to the World: Broaden the international perspective of Taiwan’s viewing public; Realize the potential of international cooperation.

Other secondary cultural issues observed in the documentary (mainly implicit): Care for the animals (even during experiments), science to serve the public welfare, value of human life, promotion of global collaboration.

To finish, I offer this reasoning with which the main message of this documentary, taken as a discourse, could be summarized: in the last earthquakes many deaths could have been avoided if the authorities had warned with more time. Scientific experiments have demonstrated that some animals have a sixth sense to predict earthquakes, although this technique is difficult to apply and control. If scientists had more funding, thanks to international cooperation, effective implementation would be achieved sooner.

3.6. A Town Called Success (Frank Smith, Rob Taylor, Jessie Shih, 2013)

Aired on 16 August 2013, this documentary won, among other awards, the Bronze World Medal in Environment & Ecology at New York Festivals-International TV & Film Awards, (USA, 2013), and the CINE Golden Eagle Awards, Televised Documentary & Performance-People, Places & Arts (USA, 2014).31

It is a co-production of PTS and IFA Media, with director Frank Smith and cinematographer Rob Taylor, both from the UK. They utilized high-speed digital photography on land, in the sky and on the sea to capture the unique drama of marlin-spearing fishermen, based in Chenggong (literally known as “Success”), inside Taitung County, East coast of Taiwan (PTSF 2013, 6–7).

The mode of this documentary is quite “Observational”, because there is no voice-over at all and no formal interviews. But, at the same time, it possesses certain characteristics of “Expository” mode. First, because many people who appear on camera frequently explain their lifestyle, looking at the member of the crew, who is close to the camera and probably has asked some questions before recording. Second, because there are some informative sentences (six times), in the form of long intertitles—white characters over black screen—that provide information about the place or about the life of these men. For example, at the beginning: “Winter is high season for the most valuable. As Black Merlin began to migrate from Japan past Chenggong”. Then, in minute 12: “Taiwan’s fishing boats are competing for fewer and fewer fish. Local researcher Wei Chuan Chiang has persuaded local fishermen to help him track the health of billfish stocks”.

A few times the tone used by the virtual narrator is a bit rhetorical, perhaps underlining aspects that have been said by others or the viewer can suspect. In general, they are useful. For example, another two: “The crew’s average age is 60 years old. Each one handles a harpoon that weighs 20 kilos”. And, nearly to the end: “In November the harpooners celebrate their Sea Deity’s birthday”.

Some of those sentences function also as labels that divide the documentary (75 min) in four parts, which coincide more or less with the seasons. Nevertheless, the narration has a lot of unity, thanks to the unique boat and crew that the producer team has selected to follow. They travel together in the boat in different days (although that is not reason enough to apply the tag of “Participatory” mode), enter their homes or the restaurants for dinner or drink, go to the hospital with the captain when he has a pinched nerve in his back, and so forth. Another secondary narrative thread, very effective, is the listening (four times) to the Weather Forecast report at the local radio station, while they are returning from the sea or making preparations to go out. Yet another resource, less effective but useful as a counterpoint are some images on land, such as women doing shopping, a dog in the middle of the street, and so forth.

The protagonist is, without a doubt, the crew’s captain, Chen Yong Fu, a local legend (see ). He has been a harpooner for over 45 years, and lately he has found personal and social difficulties with continuing to work. He makes his energetic work compatible with a gentle character during free time, frequently full of nostalgia, for his dying trade:

Harpooners love the thrill of the hunt. The exhilaration of spotting a fish… Even the nerves are part of the thrill. Gillnets are indiscriminate. Everything that becomes entangled dies. Where’s the thrill in that? (…) Gillnetting has become prevalent all along the eastern coastline. But once fish stocks diminish, these boats will all vanish. In the end, there will be no fish to catch.

Social and generational change, together with tradition and nostalgia for past times in general, are probably the main cultural issues in this documentary. For example, many of the characters tell how they started fishing. These are the words of the captain, pronounced one night, sitting on his boat, sharpening hooks, after saying that he is proud about his son getting a PhD (but it’s implicit that he misses someone who can replace him; in the background, a nice and calm violin tune):

I love the ocean. I was never interested in studying. When I was 14, my father took me out to fish with him. He was very strict and insisted I learn everything. I couldn’t slack off and he yelled at me for the smallest mistake. My father taught me everything.

And his wife, while preparing dinner in the kitchen, speaking as if she were alone, smiles but shows resignation in front of the harsh reality (viewer already knows that captain needs surgery and rest, because of his pain in the back, and she had said that he should quit fishing):

Infact, our son really respects his father. If interested, he could take over from his father, when he retires. But young people hate to be nagged. They have their own way of doing things He’ll come back when he wants to. He is thinking about it. [brief silence] The boat is ours, and his father… he is a great harpooner”.

The social change is also reflected in the mixing of classes inside families or groups of friends: “People used to look down on fishermen”, says the captain to explain his parent’s difficulties with him marrying a daughter of a schoolteacher. Now, all his present colleagues are happy with his son, who has become friends with them—one of the crew says that, in the middle of a drinking relax time—despite having higher education– “To him, we’re all the same.”

There is a sense of friendship and community, among spearing fishermen, compatible with a deep-rooted fondness for gambling and competition. That is mentioned or implicitly observed several times during the documentary: on the one hand, phone calls between colleagues in the middle of the ocean to see how work is going or to ask for help; on the other, an official contest in the harbour to reward whoever gets more fish (frequent discussions about the rules), or private conversations about who is better on cards, who is able to drink more, and so forth. In this sense, one could see some machismo to the detriment of women’s dignity. After a good catch, having dinner together, with their wives present, one member of the crew says to the captain, laughing: “Your wife should drink a little more! A lot more! You deserve some tender loving tonight!” Even more striking are the words of the captain’s wife herself, in front of him (both smiling) few minutes before the feast to celebrate the relatively good income of the entire year: “We have hired pole dancers, it’ll busy! Pole dancers is good for the eyes. It keeps fishermen’s eyes sharp for marlin spotting”.

The way animals are treated during the documentary may also be shocking for the eyes of modern civilization. Harpooning is crude already. To see big marlins drowning is painful too. But hitting them with a club during 5–6 s—although the fisherman usually does it to make the flesh softer, and the viewer realizes that fish is already dead—would be very risky, and probably unacceptable, on a Western television channel. Even more when the man is shouting words similar to “Bring your family here! Bring your friends here!”.

On the contrary, love and even admirable tenderness for parents and elders are very explicit, there is for example the member of the crew who takes care of his father who is very old, has lunch with him, does the shopping (“I am his kid. It’s the least I can do”) and speaks proudly about his father’s past as a harpooner: “He was a skilled harpooner back in his days. He would always hit fish that others missed. He was a true grafter and legendary for spotting fish”.

Popular religion (Davison and Reed 1998, 37) is also very important in this documentary. This can already be checked in the initial teaser, where a procession through the streets is shown, in slow motion, with four men carrying a platform on their shoulders with above a big statue of a marlin, and around them a crowd who assists, some of them lighting firecrackers and throwing them into the air. A title explains the meaning: “Every year the harpoon fishermen of Chenggong, Taiwan, pray to the gods for a bountiful season”. Also, in the Sea Deity’s birthday mentioned above, many people are praying in a temple, holding incense sticks. One of them prays aloud clasping his hands and bowing his body: “To our 1000-year-old Sea Deity. I’ve been your humble servant for the last 15 years. My only request is for you to keep us fishermen safe. Allow us to make a decent catch, and earn a living.” Moreover, this religiosity is also present in ordinary conversations. In the middle of the documentary, Captain Chen takes a rest with his wife and some friends after selling a big fish in the market and recalls how hard he prayed at the temple the day before in the hope of catching a nice marlin.

The relationship with Mainland is another issue that is briefly shown in a conversation between Captain Chen and a very old friend of his, while they are drinking and speaking about the bad situation of the fishing trade and the future: “Try to be content with yourself. The deity will help you. You are debt free. You have money saving. (…) You are always speaking about traveling to China… I wouldn’t dare.” The captain doesn’t seem comfortable with that conversation and just says: “Forget it”.

Another secondary cultural issue, implicit, is the civil responsibility that the public channel promotes by presenting the heroic life of a group of people. That was exactly the main objective of “the father of documentary,” John Grierson, when he produced the pioneer genre-films about working-class groups, starting also a public institution like the General Post Office Film Unit. One of those documentaries, in this case directed by himself, few years before, as a first test, was Drifters (UK, 1928): a documentary about North Sea herring fishermen, “an epic of steel and steam” (Barnouw Citation1993, 88). On its own, A town called Success—as stated on the official website—would be an endearing “tale of the last spear fishermen, fighting to preserve their cultures and the oceans around Taiwan”. But it is not a fairy tale: those exemplary lives are real, worth knowing and admiring, at least in their positive aspects.

4. Conclusions

The shift from politics to cultural issues in the concept of Taiwanese identity from the 1990s can be traced in some programmes aired by PTS, especially in those aired in the years around the Centennial of the R.O.C. (10 October 2011). A thematic analysis of a qualitative selection of international awarded documentaries (2009–2013) shows that there are some constant cultural issues, represented with a configuration that can be shared for people of different ideologies.

The main one—very present in all the six documentaries selected for the analysis—is the appreciation for the richness of the island, both human and natural. There can be found admirable people from many different ethnicities or cultures who deserve respect from everyone, avoiding antagonisms of the past (Rubinstein Citation2007, 536). And this is promoted by showing their traditions and their cultural values in a good light. There is also a unique flora and fauna, frequently displayed or intensively described through images and words (in documentaries examined in 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, and 3.4 sections). That knowledge should be encouraged institutionally to educate the audience towards a true ecology, which must lead to a better contact and harmony with natural areas or, at least, a real interest in the protection of the environment, particularly the water. Also, knowledge of the life of animals can contribute to an improvement of society (sections 3.5 and 3.6).

Among the traditions, the religious sense occupies an important place. It can be seen in four of the documentaries selected for the analysis (sections 3.1, 3.3, 3.4 and 3.6). Christianity coexists with other religions and beliefs in deities connected with nature, especially for aboriginals—conversion to Christianity among aboriginals has been a continuing phenomenon since the 1950s (Hsieh 1994, 192)—with manifestations not only inside temples, but also in the ordinary life, private conversations, work spaces, spontaneous expressions, and so forth. Together with these traditions, there can be found a deep value for human life, an appreciation for the elders and the family in general, and for the happiness of the birth of a child.