Abstract

Poland is one of the most Catholic countries in the world. 33 million out of its 38 million people (92.9% of its population) declare themselves to be Roman Catholic. Church initiatives for the needy, whether poor or immigrants, are everywhere. The Church is a robust and influential institution, strengthened by the pontificate of the Polish Pope, John Paul II, who is considered not only a saint but also a national hero. In many aspects, Poles could be put as an example for Catholics in other countries. But there is an issue in which the Church is not at the vanguard: the fight against sexual abuse. Recent cases have eroded the solid trust Polish people put in their Church. More recently, the documentary Tell No One, released in two parts in May 2019 and May 2020, was a turning point, and the confidence in the institution visibly plummeted. This case study tells the recent story of the issue of sexual abuse by Catholic clergy in Poland, its lights and its shadows. The paper ends with some suggestions for a trust recovery strategy, as recommendations for both Church authorities and their communication offices.

Introduction: the triggering event

The path leading to the church looked like any other road in the Polish countryside. A vivid and joyful memory for thousands of Polish kids – they walked those pathways every Sunday with their parents to their village’s Sunday mass. A 39-year-old Polish woman takes the same path she used as a kid, but there is no joy in her steps. She goes back not for mass but to confront the Catholic priest who reportedly abused her when she was a nine-year-old girl. Using a hidden camera, she questions him: ‘You destroyed my life… are you aware of that?’

This is the opening scene of Tell No One, a 2-hour Polish documentary by the Sekielski brothers, released online on May 11, 2019.Footnote1 The film shares stories of abuse from the victims’ perspective. Survivors confront their abusers on camera, and the video shows how those priests refused to show any repentance and still blame the victims for what happened.

The documentary displayed some examples of the abuse of power in the Church in Poland as a widespread and ever-present behavior. Its free release on YouTube had a record audience (as of May 2020, the documentary has had 23 million views, the equivalent of half of the Polish population). Its impact had the magnitude of a public opinion earthquake. The Episcopal Conference was forced to publicly admit, for the first time, that there is an ongoing crisis.

This article aims to examine the main cases of sexual abuse in Poland since 2018, assess the official response in each event, how media reported on it and what its impact was on public opinion, and review the lessons learned by the Church to prevent and fight sexual abuse and rebuild trust.

Theoretical framework: trust building, scandals and recovery management

Trust is an elusive concept: ‘We perceive trust like air, only when it is scarce or polluted’ (Baier Citation2001, 42). At the same time, its consequences inside organizations are evident. It is a necessary element of internal and external cooperation (Tyler Citation2003), the basis for motivation (Lewis Citation1999) and change management (Sprenger Citation2002). In addition, trust has external consequences: it is a source for competitive advantage (Barney and Hansen Citation1994) while Urban and Sultan (Citation2000, 48) declare trust is the ‘most valuable resource’ for successful companies in the future. For these reasons, trust is becoming more and more relevant for organizational success (Child Citation2001).

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, trust is the ‘firm belief in the reliability, truth, or ability of someone or something.’ In this paper, we will accept the most common definition of institutional trust: the intention to accept vulnerability based on positive expectations regarding another's conduct (Davis, Mayer and Schoorman Citation1995). In this sense, it consists in the tendency to ascribe virtuous intent to another individual or entity (Lewicki, Tomlinson and Gillespie Citation2006).

Trust management became a popular topic after the spate of massive corporate scandals at the beginning of this century: Enron, WorldCom, Parmalat, Arthur Andersen and other giants sparked an interest on how prestigious institutions can lose public trust in the blink of an eye. Soon, experts (Putnam Citation2000; Turnbull Citation2002) showed the connection between the public disapproval created by a scandal and its consequences both in terms of economic value and in the quality and strength of relations with stakeholders.

More or less at that time, Edelman revealed its global Trust Barometer (edelman.com). In the 19 years since its launch, the barometer has become not only a useful tool for companies and institutions to understand their environments, but also a fundamental instrument in deciding their strategies and protecting their reputation.

There are several trust management frameworks available. Some of them are academic, such as the Integrated Stakeholder Trust Management Framework, or ISTMAF, proposed by Pirson (Citation2007); others have a more practical approach, such as Reputation Track or Reptrack (reptrack.com), developed by the Reputation Institute in 2006, which is intended to be used by large corporations or companies in very regulated industries.

Without quantitative and qualitative analysis to support our contextual intelligence (Gregory and Willis Citation2013), it is very difficult, if not impossible, to properly lead an organization. The intuitive scanning, monitorization and decision-making process is maybe the rule for small and local organizations, but it is a dangerous approach when dealing with complex and articulate organizations (Czarnecki Citation2009).

Many institutions that do not take a proactive approach to managing, protecting and fostering trust end up dealing with trust only after a crisis or a scandal. We understand scandal as ‘a crisis, but in addition there will be a revelation of a moral misconduct committed by an individual (regardless of whether it was actually committed or if it is merely a presumption), and the indignation as a consequence of this revelation’ (Fronz Citation2011).

The number of scandals has not diminished in the first two decades of this century. On the contrary, the Institute for Crisis Management (ICM) shows in its annual reports that scandals are more frequent and more severe in their consequences. They affect not only commercial entities but all kinds of institutions: political, educational, cultural, NGOs…and religious organizations.

An interesting finding of various research papers and cases about scandals related to religious institutions is that their stakeholders react the same way as those of other types of institutions (Ivereigh et al. Citation2019). So, it is possible to conclude that general crisis principles and best practices are applicable also to religious institutions (de la Cierva Citation2014).

Crisis management experts (Lukaszewski Citation2013; Walker Citation2015) studied the most effective strategies for recovering from a scandal. To regain trust, three elements are required: first, the organization has to do internal and external audits after the scandal in order to understand its causes (Chase Citation1984); second, a reform plan has to follow (Stiglitz Citation2004): there is no recovery without an internal reform that ensures that the same problem will not be repeated again (Dezenhall and Weber Citation2007). Third and last, the organization has to establish a different relationship with stakeholders based on consensus and transparency (Veil and Husted Citation2012; de la Cierva Citation2018).

These three steps are the core of trust repair, an emerging domain gaining the interest of management scholars (Dirks, Lewicki, and Zaheer Citation2009), and the foundation of effective apologies and promises (Kim, Ferrin, Cooper and Dirks Citation2004; Hearit Citation2006).

Following this framework, the first topic to be addressed will be the issue of sexual abuse by Polish clergy in chronological order, considering the facts, the Church’s official response and the dent it left in the public’s trust toward the Church. Second, some recommendations will follow based on crisis management and trust recovery, drawing from the best practices defined by Talton (Citation2008) and adapted to each type of stakeholder (Pirson and Malhotra Citation2011).

Overview of the Catholic Church in Poland

Christianity in Poland dates back to 966 when Mieszko I, the first ruler of the future Polish state, was baptized along with the whole nation. More than a thousand years of history are visible in Polish churches, chapels and monasteries. Today, churches are packed on Sundays. According to the latest statistics, 32 million out of the 38 million total inhabitants of the country declare themselves Roman Catholic (KAI Citation2018), out of which, in the year 2018, 38% attend Sunday Mass and 17% receive Holy Communion (Annuarium Statisticum Ecclesiae in Polonia Citation2020).

Through the ages, the Church in Poland was filled with iconic figures such as St. Adalbert, St. Queen Jadwiga, St. Faustyna and the legendary communist-resistance Primate of Poland Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski, soon to be beatified. By far the biggest impact in Poland’s modern history was made by Karol Wojtyla, now St. John Paul II. He was not only a pontiff who transformed the universal Church, but he was also the most important reference point for his Polish countryman, Catholics and non-Catholics alike – a rare case of being a prophet at home.

On the political side, in the 50-year-long struggle after the Second World War against the communist regime imposed by the USSR, the Church was probably the most persuasive and effective institution in keeping the Polish identity alive and flourishing. After the victory of Solidarity in the elections on June 4, 1989 (the first free election in the post-soviet era in Central and Eastern Europe), the Church became one of the most influential powers in the country.

Inconsistency in numbers

Sexual abuse of minors is like an iceberg: there are many more cases under the waterline of public knowledge than cases reported to the authorities. Researchers such as London et al. (Citation2008) and specialized NGOs like RAINN, Thorn Organization, Darkness to Light or NSPCC point out that only 20–38% of cases are reported globally.

What is important here is that there is a correlation. Knowing the number of reported cases in an area or in a time-period is useful for finding unreported cases and trying to help those hidden victims, and for implementing preventive measures both to protect minors and to find and bring perpetrators to justice. That is why research on these cases is not a waste of time but a fruitful investment for the future.

In countries where the Catholic Church has requested an investigation on the numbers and typology of cases of sexual abuse by clerics, such as the United States (John Jay College of Criminal Justice Citation2004), Holland (Deetman Report Citation2011), Germany (MHG Study Citation2019) or where there was an official investigation run by the State, such as in Ireland (Ryan Commission Citation2009; Murphy Report Citation2009) and Australia (Royal Commission Citation2017), the findings show similar results: from 1950 to 2000, around 4-6% of Catholic priests abused a minor. On different occasions, the Holy See has mentioned that the global figure is around 3–4% (Vatican Press Office Citation2019).

These figures are consistent with what the Holy See stressed in the Meeting of the Episcopal Conference Presidents on the Protection of Minors in the Church, which took place 21 February 2019 at the Vatican. Several keynote speakers (including Card. Cupich from Chicago, Card. Gracias from Mumbai and Card. Salazar Gómez from Bogotá) underlined that sexual abuse was not present in some countries but was a global issue. Fr. Lombardi (Citation2018), relator of that Meeting, summarized it: ‘Sometimes, there is the illusion that this problem is mainly ‘Western’ or ‘American’ or ‘Anglophone’. With unbelievable naïveté people think that this is only a marginal problem in their own country. In reality, to the careful eye, its presence cannot be missed; it is sometimes latent but always capable of exploding dramatically in the future. There is a need to look reality in the face.’

Pope Francis (Citation2019) confirmed that assessment, stating, ‘We are facing a universal problem, tragically present almost everywhere and affecting everyone.’

In fact, sexual abuse of minors affects the Church in every country on every continent because it is a part of a broader issue: the issue of sexual abuse of minors in general. According to UNICEF (Citation2017), 1 out of every 10 children experiences sexual abuse globally. Numbers are also significant on our continent: according to the International Centre for Missing and Exploited Children (ICMEC Citation2018), 18 million European children are victims of sexual abuse.

Not only frequent, but also unreported: a third of all countries do not collect this info (Chandy Citation2017), and frequently underestimated, because many cases are not reported. That’s why the UN commitment to achieve the 2030 Agenda Sustainable Development Goals, included this goal: "End abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence against and torture of children.’Footnote2

These crimes happen in different settings: family, schools, sports teams, free-time activities, etc., and all have something in common: an environment of trust, which most predators try to exploit to their advantage. As Pope Francis (Citation2019) has repeatedly said, sexual abuse of minors ‘is always the result of an abuse of power, an exploitation of the inferiority and vulnerability of the abused.’

In this context, it would not be surprising to learn that the Church in Poland also had cases of sexual abuse, as in any other country, due to investigative media reports. This, however, was not the case. So far, the number of victims denouncing abuses when they were minors is fairly low compared to other countries.Footnote3

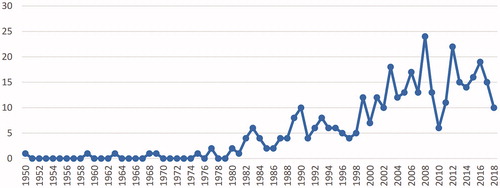

Another relevant difference between universal Church’s data and Polish data is the evolution. According to the available reports in other countries, cases of sexual abuse of minors went down: in the 1950s, affected 2.9% of the clergy; 4.5% in the 1960s, 4% in the 1970s, and only 0.2% after year 2000. The tendency in the Church of Poland, as we’ll see later, show the opposite trend.

Let us explore the causes of these divergences in the following section.

The particular Polish case

Globally, sexual abuse cases by clergy were not uncovered by the Church. Rather, the key roles were played by the media, who triggered official investigations. Local legislation also had an impact: for instance, the US legal system favorized bringing these kinds of criminal behaviors to court, and lawyers generated the publicity of those cases as an effective tool to increase both public uproar and economic compensation.

The Polish case has notable traits that explain the disparity in numbers compared to the rest of the world. In my view, four main factors may have contributed to these differences are: the legacy of communist times, clericalism, Church-media relations and Church-political power in Poland. Even if the four are clearly intertwined, it is worth analyzing them separately.

First, communist legacy

During the almost 50 years of communist rule, the Church in Poland operated in a hostile environment. The Church was ‘the enemy’ of the regime and persecution produced many martyrs, such as blessed Fr. Jerzy Popieluszko, a chaplain of the Solidarity movement in Warsaw, who was murdered by the regime in 1984.

During that half of the century, bishops knew that if anything negative that happened inside the Church was leaked and went public, it could bring massive harm. Most of the bishops in Poland today were prelates or had important responsibilities in the Church in that era. Even the youngest ones, who were teenagers at the time, remember communism quite well.

Persecution of that kind experienced for years encourages a mechanism of silence to circulate in the Church’s vessels. Secrecy was a tool of self-preservation. In addition, the Catholic faithful thought — and many still think today — that they have a moral obligation towards their religion that includes avoiding creating a scandal against the Church.

The Polish case is not unique. According to Fr. Hans Zollner, president of the Center for Child Protection at the Gregorian University, and a member of the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors since 2014, there are three issues that Churches that have gone through communist or other totalitarian regimes must overcome in order to properly face the crisis of sexual abuse of minors.

First, the Church must understand its past role as guardian of freedom during the communist era while at the same time having clergy that abused minors. The Church needs to acknowledge that it was not perfect and that not everyone behaved as they should.

Second, for many years the state institutions, media and psychologists were used against the Church by the regime. For that reason, the Church needs to undergo a transformation so that all three can once again become reliable assets and have the right to help the Church by investigating sexual abuse cases.

Third, truth will set you free — the Church needs to face the truth, even if that truth is difficult to face, and investigate. Only by accepting the truth will the Church be able to move forward: ‘I recognize how difficult it was to grasp the extent and complexity of the problem, to obtain reliable information and to make the right decisions in the light of conflicting expert advice. Nevertheless, it must be admitted that grave errors of judgement were made, and failures of leadership occurred. All this has seriously undermined credibility and effectiveness [of the Church in Poland]’ (Zollner Citation2020).

Second, clericalism

It is well known that Pope Francis regularly singles out ‘clericalism’ as one of the most dangerous threats against the Church, and he connects clericalism with sexual abuse. ‘To say no to abuse is to say an emphatic no to all forms of clericalism’ (Pope Francis Citation2018).

But he is not the first Pope to connect the dots: when the scandal of clerical sexual abuse caught Ireland by storm, Pope Benedict XVI (Citation2010) wrote a letter to Irish Catholics in which he pointed a finger at clericalism as one of the main reasons for the Church’s wrong response to the drama of abuse. The German Pope criticized clericalism as ‘a tendency in society to favor the clergy and other authority figures; and a misplaced concern for the reputation of the Church and the avoidance of scandal, resulting in failure to apply existing canonical penalties and to safeguard the dignity of every person.’ .

Ewa Kusz, vice-director of the Child Protection Center in Poland, underlines: ‘Clerical culture has a role both in the clergy and lay environment. It is a specific group defense mechanism’ (Kusz Citation2018) in which the priest takes a managerial role, standing above the rest of the society in an ‘exclusive club’ (Papesz Citation2018). What is more, lay people only strengthen clericalism by treating the clergy as ‘closer and holier to God by definition, even unstained’ (Kusz Citation2018).

Clericalism had and still has two different effects. First, ‘powerful’ priests exercise such a strong authority over Catholic families that when a child is abused, his or her parents already look at the abuser with such admiration that it makes it hard to believe their own son or daughter. Second, it creates a culture of silence around them – often laity or religious sisters working with priests knew about the abuse, but never said a word in order to not harm the institution, while the child was harmed in an unspeakable way.

There is one more element that adds to both the argument of clericalism and that of abuse of power. It was already pointed out that while the number of abusive priests declined globally since the 1980s and fell drastically after the year 2000, the opposite occurs in Poland.

‘The reason lies in power,’ Fr. Adam Zak, SJ told the author in a conversation on 26 May 2020. The president of the Child Protection Center in Kraków remembers that in the 1980s, communist persecution was still horrific. But at the same time, the Church’s opposition to the regime became much more powerful thanks to Pope John Paul II. His international presence not only gave the Church unprecedented authority, but Western donors – both individual and public – also decided to channel their financial support into suffering Poles through the Catholic Church.

This help was lifesaving for millions of people in a totalitarian country on the verge of hunger, as many other countries under soviet regime experienced.Footnote4 But, according to Zak, it also had a negative side effect: it gave priests incredible power and relevance in Polish society beyond religion, something that had never happened before. Coincidentally, the number of abuses began to rise steadily in Poland precisely in the 1980s.

Lack of media pressure

The third factor that made the Polish case unique is the lack of media pressure. As already mentioned, in most countries, sexual abuse cases were not uncovered by the Church herself, but rather by media. In Poland on the contrary, most media outlets looked at Church leaders and institutions with considerable respect.

Media mirrors society. Most journalists come from the same society that was formed by the harsh reality of the communist era. Senior mainstream journalists, now in their 40 s and 50 s, suffered communism and fought for freedom. After recovering liberty, journalists focused on uncovering the many secrets of the communist regime, as well as on the economic, political and social challenges of transforming a country back into a democracy. Those issues were more newsworthy than child protection, both in general and in the Church.

In fact, media did not begin covering Church scandals until 30 years after the fall of the Berlin wall. This might be a sign that Poland has actually reached a mature post-transformational society and is ready to move forward with investigating the institution’s past – one that was previously considered sacred.

Good relations with the political establishment

In Poland, Catholicism is an integral part of the political arena. This has been the case since the return to democracy: in all cabinets held by different political parties, several practicing Catholics occupied important roles. But this is even truer since 2015, when the conservative Law and Justice party, born in the Catholic milieu, came to power. Senior public officials, most of them identifying as Roman Catholic, defend a cultural and social coalition with the Church. Because of that, they are far from attacking the Church, but instead seek close alliance with the bishops. Because of that, so far, no political or judicial authority in Poland has started an independent investigation such as the Grand Jury of Pennsylvania (Pennsylvania Attorney General Citation2018) or the Federal Australian Government have done abroad.

In summary, media and civil investigations were key in most countries. Only then did some episcopates such as those of the United States, Ireland, Germany and, more recently, France decide to foster their own investigations. Maybe because of the lack of interest both in Polish media and among political authorities, the Church in Poland failed to take the initiative to uncover those cases.

Therefore, the Polish Episcopate has not taken the appropriate steps to properly solve this dramatic issue on its own terms without external pressure — a ‘can’t miss moment,’ as John Allen puts it. As we will see later, someone else is doing this now, and the Church has lost the advantage.

Let’s see in chronological order the three main episodes which broke the so far complete public silence on this matter.

First exception to silence: the village of Tylawa

Tylawa is a tiny post-communist village in Southeastern Poland. That region has an unusually high rate of unemployment, vast rural areas and simple, generous people who lead deep and traditional religious lives. The entire village is present at Sunday Mass and parish pastors are viewed as a little lower than God.

It was exactly in Tylawa where the parish priest, Michal Moskwa, abused several girls during a 35-year span.

In 2001, one of the girls told the mother of her schoolmate what the priest did to her. ‘She told me he was putting his fingers down there and, while doing that, he was saying that he is healing her in the name of Jesus Christ’ (TVN2424 2019).

When the mother asked her daughter’s friend when that happened, she replied: ‘Yesterday.’ The pattern of abuse was soon to be uncovered and it was similar to so many abuse cases: a parish pastor with wealth and power; a small, impoverished town; children whom no one cared about, with alcoholic parents who were often abusive themselves – ‘my sisters were jealous that the priest is giving me so much love,’ Ewa Orlowska, one of the victims, recalled (Orłowska Citation2008).

Lucyna Krawiecka, the lady who first heard the stories, promised herself she would save the girls from further abuse. But she restrained herself from reporting the case to the Church authorities because she was the wife of a Greek Catholic priest. She thought it was not proper to report on a parish pastor of the Latin rite (Gruca Citation2019).

But when Lucyna heard more grim reports of primary school girls (horrible images I prefer not to repeat here), she took courage, recorded the testimonies of the girls and in March 2001 went straight to the archbishop, Jozef Michalik, who asked her to go directly to the prosecutor, which she did in May 2001.

Immediately afterwards, Lucyna went to the media. She told Radoslaw Gruca, investigative reporter for Gazeta Wyborcza, that she asked the archbishop to share the accusations of the families hurt by the priest with him or with someone from his curia. Michalik reportedly answered: ‘This priest has done so much good for his faithful, and now you accuse him of such bad things?’ (Bujara Citation2018).

Gazeta Wyborcza broke the news on June 4, 2001 and made headlines throughout the country. Two days later, Michalik sent an open letter to the faithful in which he wrote: ‘I am obliged to express my sympathy toward your pastor and at the same time express my hope that his fellow priests and you, faithful, who know the Church environment better than the aggressive media do, will not lose trust in your pastor, but will show him closeness and express it in prayer’ (Bujara Citation2018).

Archbishop Michalik is now retired. His biographer, Tomasz Krzyzak, suggests that at that time he believed that the case was an attempt by Greek Catholics to take over one of the Catholic churches in the city, especially since the reporting mother refused to give the bishop names of the victims (Krzyżak Citation2015). As already mentioned, his reaction confirmed Krawiecka’s initial fears.

It was proved in court that that priest had molested six girls, and the details recounted during the trial brought chills. Additionally, the victims recalled that he was abusing them during catechesis, in front of the boys, who were laughing at them: ‘The humiliation was hard to imagine,’ one of the survivors recalled (Gruca Citation2019). That priest was convicted in the second court ruling in 2004 and sentenced to two years in prison. He was also suspended for five years and forbidden from being a catechist for eight years.

As for Church proceedings, he was released from the parish of Tylawa before the court ruling in 2003 and was prohibited from being present in the area of the parish. He was also forbidden from performing any pastoral activities (KAI Citation2019).

What is shocking in this case is that the village turned their back on the victims and on the brave mother who uncovered the story. Even the mother of one of the survivors told her child that she was no longer her daughter and that God will judge her for what she said against the priest. ‘I wanted to be invisible,’ Ewa recalls. After testifying in court, she had to leave her hometown because the villagers called her a traitor and a prostitute (Jabłońska Citation2017).

Even more shocking is the aftermath of the case. On May 22, 2019, private broadcast network TVN24 broke the news that Fr. Moskwa was still saying Mass in southeastern Poland. They also recorded him on a hidden camera saying to a reporter: ‘I didn’t appeal the verdict. Jesus didn’t appeal either’ (TVN24 Citation2019). He admitted he bathed the girls (‘I gave them a bit of pleasure’) and that the parents often asked him whether the girls can spend the night in the parish (it was confirmed by the victims that the priest paid the families that sent the girls to the sleepovers at the priest’s house).

After the news was aired, the local diocese’s curia apologized and released a statement saying that Moskwa was prohibited from any further public appearances and that a Church curator will execute the prohibitions (KAI Citation2019).

Beyond the horrific testimonies of the victims, this story brings attention to the wrongdoings not only in the Church (the prosecutor in the first instance who turned down the case was Stanislaw Piotrowicz, now a politician in the Law and Justice party that is currently ruling the country). It also illustrates that a change of heart takes a long time for the entire Church – not only within Church hierarchy, but also in the faithful in Poland, whose attitude toward the survivors was yet a supplementary harm to what they had already suffered. It also shows that the Church needs to revise its protocols about controlling abusive priests even many years after the convictions.

Second, an abuse of power in the making at Poznan

The first and most visible tremble of the hierarchical structure of the Church in Poland was the case of the archbishop of Poznan Juliusz Paetz (1935–2019). In 2002, reporter Jerzy Morawski broke the news in the national daily newspaper Rzeczpospolita. Using credible sources, all anonymous, he said that Paetz had abused several young seminarians for years, abusing his position as their superior. The ‘prize’ of consenting to homosexual activities was the opportunity to study abroad.

Poznan is one of the most important and biggest dioceses in the country. It was the final destination for Paetz after his time at the Vatican, where he was the Secretary for the Synod of Bishops between 1967 and 1976.

Morawski broke his story by saying: ‘None of my informants – clergy or lay people – agreed to publicly disclose their names. However, they did not refuse to talk. They said they were convinced that the press publication will help in what they could not cope with themselves. And they said that it will help the Church. It is about the sexual harassment of clerics and priests by Archbishop of Poznan Juliusz Paetz’ (Morawski Citation2002). There are things the Polish public knows about the case. But some details, even 20 years later, are still unknown.

We know that the case had been reported to the Vatican before Rzeczpospolita broke the news. In fact, John Paul II sent some trusted advisors to Poznan to investigate at the Poznan seminary for four months. Paetz was removed from office soon after. But the Church never made the information public.

We do not know for sure who accused the bishop, but media received some hints. ‘One of the heroes of the case was the rector of the seminary, Fr. Tadeusz Karkosz,’ Tomasz Krzyzak, a renowned Polish journalist and Church analyst, told the author of this paper in a conversation on 2 May 2020. Karkosz closed the doors of the seminary to his own archbishop, asking him not to visit the seminary again once he learned that his seminarians were abused. Karkosz was later removed from the post and died unexpectedly at the age of 53. It was probably he who reported the case to the Vatican, but after almost 20 years the details have yet to be released by the Church.

We do not know either who brought the report to the Pope. Most journalistic sources, say it is probable that the pontiff’s source was Wanda Poltawska, one of the Pope’s closest life-long friends. According to unofficial sources, John Paul II reportedly cried when he read those documents.

In any case, this event was a milestone for Polish journalism: ‘I was not the first journalist who knew about the case,’ Morawski wrote. ‘There were other journalists who learned about this scandal before me. They had the texts ready, but they were afraid to publish them’ (Ławnicki Citation2019).

Additionally, since the proceedings of the case are still secret, many inquiries then-left-unanswered are still valid questions today. For instance, what was the role played by the deputy bishop of Poznan at the time, now-Archbishop of Kraków, Marek Jedraszewski?

In a testimony played to the bishops at the Vatican during the Meeting on the Protection of Minors in the Church in February 2019, one of the victims compared the abuse crisis to a cancer in the Church, and another survivor acknowledged that ‘it is not enough to remove the tumor and that's it,’ but stressed that there must be measures in place to ‘treat the whole cancer’ (Arocho Esteves Citation2019). For the Church in Poland, the case of Paetz is exactly that – a rotten cancer that spread into to many cells of the Church around the country and until it is fully and transparently removed, Church structures will not be able to move forward.

Third, a Polish nuncio abroad

Polish papers also covered another scandal by a Polish clergyman. But this time it did not happen on Polish land.

In July 2013, only four months after Francis was elected Pope, media broke the story that the papal nuncio in the Dominican Republic, Archbishop Jozef Wesolowski, had been accused by multiple altar boys of sexual misconduct. It was the archbishop of Santo Domingo, Cardinal Nicolas Lopez Rodriguez, who personally informed the Pope in late July ‘that there had been ‘serious accusations’ against Wesolowski,’ said the Vatican statement signed by Fr. Federico Lombardi, director of the Holy See press office (Pullella Citation2013).

In August, the papal diplomat was recalled from the Dominican Republic and on August 21, 2013 (Onet Citation2018), the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith began the trial. The former nuncio was arrested on September 23, 2014 (Ansa Citation2014) and was under house arrest for 60 days in the Collegio Apostolico dei Penitenzieri, a residence for clerics inside the Vatican.

His trial began on July 11, 2015. The archbishop had been accused of forcing sexual acts, downloading and using child pornography and harming the victims’ mental health, as well as depraving the faithful (Wiadomości Citation2014). One day before the trial was to start, Wesolowski was admitted to Policlinico Gemelli and, after being released from the hospital, died of a heart attack on August 28, 2015 (Vatican Press Office Citation2015).

The disgraced nuncio was buried in Czorsztyn on September 5, 2015. During the ceremony, a moment of silence replaced the homily. Nonetheless, some fragments of Wesolowski’s letters to his family were read aloud, in which the prelate professed his innocence: ‘I am cheerful because I did not commit these terrible deeds. My main fault was being imprudent walking by the sea and having contacts with street children, who later proved to be involved in drug trafficking and prostitution. It is true that I helped many of them, I visited them in prison, prepared them for the sacraments (…). It is so hard to prove it all now, and three of them accuse me of hurting them’ (Dziennik Citation2015).

Concelebrating the funeral was the auxiliary bishop of Kraków, Jan Szkodon, who will be the protagonist of another event described later in this paper.

Both the cases of Archbishop Paetz and nuncio Wesolowski were also extensively covered by Polish media, secular and Catholic alike. Additionally, some books were published about the abuse of power in the Church in the context of those particular cases, highlighting the hypocrisy and abuse caused by the priests.

Those stories made a dent on Polish public opinion: for the first time, high-ranking Church authorities had undergone internal but public investigations. But their impact inside the Church was even deeper: those cases coincided with a steep increase in the number of denunciations of sexual abuse by clerics. What was happening?

The Polish answer to the Holy See's new guidelines

The first Vatican document directly addressing sexual abuse of minors after the first manifestations of the coming tsunami in the United States was Pope John Paul II’s motu proprio Sacramentorum sanctitatis tutela, published in 2001. The new law put the acts of sexual abuse by clergy into the category of ‘most grave delicts’ (Pope John Paul II Citation2001).

From then on, all cases of sexual abuse of minors were to be directed to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, whose prefect was John Paul II’s closest collaborator, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger. When the real dimensions of the plague of sexual abuse were uncovered first by the Spotlight investigation in Boston, and soon also by other news organizations in other cities, Pope John Paul II (Citation2002) met with the authorities of the Episcopal Conference of the United States, and famously stated: ‘there is no place in priesthood for those that harm the young’.

It was his successor, Benedict XVI who had to face the crisis spreading into European countries, first in Ireland in 2009, and afterwards in his homeland of Germany in 2010. But the epicenter, in media terms, was still in America. During a press conference on a plane during his trip to the United States on March 15, 2008, Benedict XVI strongly confirmed the words of his predecessor: ‘We will absolutely exclude pedophiles from the sacred ministry; it is absolutely incompatible, and whoever is really guilty of being a pedophile cannot be a priest. (…) These are the two sides of justice: one, that pedophiles cannot be priests and the other, to help in any possible way the victims’ (Pope Benedict XVI Citation2008).

The German pope has also shown compassion to the victims of sexual abuse, meeting with them during most of his apostolic trips – especially those to the United Kingdom, Germany, Australia and Malta (here, even against the request of local bishops).

For Joseph Ratzinger as a person, both while leading the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith for more than 25 years, or as the Roman Pontiff, sexual abuse of minors was one of the most crucial issues. He confirmed and systematized John Paul’s motu proprio with a series of new ‘Norms on More Grave Delicts,’ which were sent to the bishops in a letter dated May 21, 2010 (Lombardi Citation2018). It is important, for the content of this paper, to stress that Benedict’s motu proprio was published, while the previous one was promulgated but not made public.

Another milestone in Benedict XVI’s pontificate happened a year later, in May 2011, when the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith circulated a letter to all the episcopal conferences with the aim of ‘assisting conferences in developing guidelines for dealing with cases of sexual abuses of minors perpetrated by clerics’ in light of the ‘new norms’ established by the Pope in 2010 (Vatican Resources Citation2020).

Every episcopal conference was asked to prepare its own guidelines or to revise those already existing and to send the new version to the Congregation within one year to allow for any observations to be made (Lombardi Citation2018).

While ‘many episcopal conferences did not respect the deadline’ (Lombardi Citation2018), the Church in Poland did. The Polish Episcopal Conference quickly followed the rules coming from the Vatican. This is, step by step, what the Polish bishops did in the period of 2013–2019:

In June 2009 (even before the 2010 letter of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith), the Polish Bishops’ Conference approved guidelines on Church procedures regarding clergy accused of sexual abuse of minors under the age of 18 (Polish Bishops’ Conference Citation2019a).

In June 2013, Fr. Zak became the coordinator of the protection of minors at the Polish Bishops’ ConferenceFootnote5 and opened the Child Protection Center in Kraków. Zak has become one of the most active promoters of change in the Church in Poland. Under his direction, the Center has trained over 5,000 people in the last 5 years and has become the reference point not only in Poland but also in Eastern Europe.

In October 2013, official statements declared the Church’s position on this subject: ‘We strongly emphasize – there is no tolerance for pedophilia. This is the position of the entire Church in Poland – both clergy and secular Catholics’ (Polish Bishops’ Conference Citation2019a).

In June 2014, the conference ‘How to understand and respond to sexual abuses by the clergy,’ successfully organized by the Child Protection Center in Kraków, shed light and knowledge on the problem. The conference ended with a penitential liturgy presided by the bishop of Plock, Piotr Libera. The mass was also concelebrated by the longtime secretary of Pope John Paul II Cardinal Stanisław Dziwisz, the Primate of Poland Archbishop Wojciech Polak, Bishop Grzegorz Rys (at the time auxiliary bishop of Kraków, now archbishop of Lodz) and the Apostolic Nuncio, Archbishop Celestino Migliore (Gość Niedzielny Citation2014). Many interpreted this as a hopeful and eloquent sign of Church repentance for the sins of her own sons. The church was packed with faithful.

In October 2014, the Polish Episcopal Conference adopted the ‘Guidelines for initial canonical investigation in the event of clerical charges of acts against the Sixth Commandment of the Decalogue with a minor under the age of eighteen.’ The Guidelines were approved by the Holy See in 2015 and amended in 2017 (Polish Bishops’ Conference Citation2019b).

In September 2018, the Polish bishops met in Plock and made the following announcement: ‘Children and young people are a constant concern of the Church, which requires, among other measures, to protect minors against abuse. The position on this matter is still valid and unchanging: zero tolerance for sin and the crime of pedophilia in the Church and in society’ (Child Protection Center Citation2018a).

In November 2018, the Polish bishops declared: ‘We have a firm will to cleanse ourselves from sin and the crime of abuse. (…) We repeat after Pope Francis: ‘the pain [of children and young people] and the pain of their families is our pain.’ (…) We apologize to God, the victims of abuse, their families and the community of the Church for all the wrongs inflicted on children and young people and their relatives by clergy, consecrated persons and lay church workers. We ask the Lord to give us light, strength and courage to firmly combat moral and spiritual corruption, which is the basic source of sexual abuse of minors. We ask the Lord to give effectiveness to our efforts to create an open and child-friendly environment in the Church’ (Archdiocese of Kraków Citation2019).

In January 2019, following specific instructions from the Holy See, Archbishop Gadecki, President of the Polish Bishops’ Conference, invited all those hurt by sexual abuse to meet with him prior to the Meeting on the Protection of Minors in the Church, to be held in the Vatican.

In March 2019, Polish Bishops published a survey with the number of members of the clergy who had been accused of abusing minors from 1990 to 2018 and stated, ‘we strongly condemn all forms of exploitation of minors’ (Child Protection Center Citation2018a). Archbishop Wojciech Polak, the Primate od Poland was named Delegate of Child Protection of the Polish Bishops’ Conference. As the succession of documents and statements listed above clearly shows, the Church in Poland was very diligent in transcribing the new guidelines coming from Rome into local norms. Let us study now whether these new rules really did change the way Church authorities were dealing with cases of sexual abuse and how much a conversion, a change of hearts and minds that Pope Francis was demanding of the whole Church (Pope Francis Citation2016, Citation2017) actually transformed the institutional culture of the Church in Poland.

Sound advice unheard

In June 2013, the bishops appointed Fr. Adam Zak as coordinator of child protection of the Polish Bishops’ Conference.

The choice could not have been better. Zak, a longtime assistant for Eastern Europe of the Superior General of the Society of Jesus in Rome, personally assisted Peter Hans Kolvenbach and his successor Adolfo Nicolas when the Jesuits were going through a historical crisis in Germany and other countries. In 2014 he convinced the bishops that education is key in prevention and started a Kraków -based Center for Child Protection.

For years, however, Zak seemed to be the only one who predicted what was really coming. In 2017 and 2018, he wrote two special reports for the President of the Polish Bishops’ Conference, archbishop Stanislaw Gadecki, urging that the reaction of the Church in Poland toward cases of sexual abuse be proactive.

Zak warned that the documentaries which were being produced would have a great impact on public opinion and that immediate institutional reaction and a new approach from the bishops would be needed. He urged many decisions: training for bishops and for pastors to deal with those cases, promoting a prevention system, giving the green light to Catholic media on information policy, and creating contact points to make it easier for people to report… But he was not heard.

The tireless Jesuit has been an important ombudsman for the faithful through the years. To quote two of his famous interviews with Catholic media: ‘We are on the verge of a creepy crisis: we start to believe too much in guidelines and in what we’ve already done, so much so that we think the scale of the issue is smaller than elsewhere’ (Zak Citation2017); ‘I have no reason to believe that things in the Church in Poland were done differently than in the United States or Ireland’ (Zak Citation2018).Only six months later, those words would prove to be prophetic.

A remarkable press-conference

At the beginning of March 2019, the episcopate organized a press conference to release an official survey on the number of cases of sexual abuse in Poland since 1950 and reported between 1990 and June 2018.

According to the survey, there were 625 victims during that timeframe and 382 abusive members of the clergy; 270 of the cases were closed and 68 priests were expelled from priesthood (Child Protection Center Citation2018b).

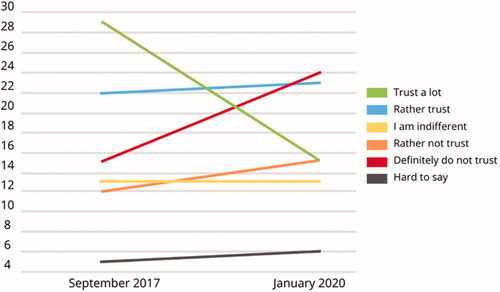

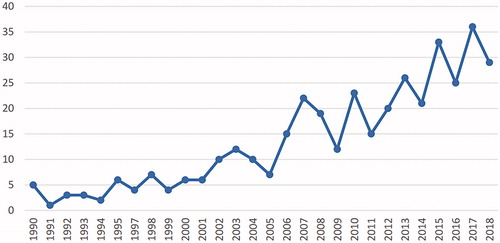

Some data were remarkable. For instance, compared to reports released by other episcopates, the timeframe of reported cases was actually quite recent and yet displayed an exponential growth in reports overtime: in 2001, 5 priests were denounced in the whole country, while in 2017 the number increased to 35 (See ).

The time in which these crimes were committed shows a different trend than in other countries. Most of the cases in Poland are recent – the majority of them were committed after 1990 (See ).

Figure 1. Number of cases reported in years (Child Protection Center Citation2018b).

Figure 2. Abuses by year (Child Protection Center Citation2018b).

The press conference was intended to be a persuasive sign of change in the spirit of responsibility, accountability and transparency, which were the core principles of the Vatican Meeting on the Protection of Minors in the Church, which took place only three weeks prior.

Three bishops were seated at the table in front of cameras and reporters of all major mainstream Polish media: President of the Polish Bishops’ Conference, Archbishop Stanislaw Gadecki; his deputy, Archbishop of Kraków Marek Jedraszewski; and Archbishop Wojciech Polak, the newly appointed Delegate for the Protection of Children.

The appointment of Polak as the Delegate for Protection of Children was a major step for the Church in Poland. The fact that the first person in charge of this new role was the Primate displayed the importance Polish bishops were assigning to this new mission. Footnote6

The words from the vice-president of the Episcopate felt like a cold shower. Jedraszewski told the media: ‘The Church must be impeccably resolute in the fight against evil, but she must also call for conversion, penance and show mercy to the perpetrators, if they show sincere regret,’ adding that the ‘zero tolerance’ principle is totalitarian and originates from Nazi traditions (Guzik Citation2019a).

To top it off, president Gadecki added that pedophilia in the Church is actually an ‘ideologically coined’ slogan and ‘quite skillfully chosen’ by the enemies of the Church, and while the problem exists, the media uses it to destroy peoples’ trust in the clergy (Guzik Citation2019a).

Those comments coming from the highest representatives of the Church in Poland, partnered with the blatant absence of any words of apology towards the victims, sparked outrage among Catholics and citizens in general. Only Polak was compassionate toward the victims, stating, ‘Each of the victims should arouse in us, the clergy, pain, shame and guilt.’

Zbigniew Nosowski wrote after the press conference: ‘The bishops’ presidency does not understand that their approach to sexual abuse may be a ‘to be or not to be’ in the Church for many Catholics’ (Nosowski Citation2019). Also, in an interview with Crux, he added: ‘The hierarchy in the Church has to finally get it that their words in any other social aspect will remain unheard if they will not deal with sex abuse first’ (Guzik Citation2019a).

That press conference was a sign that the cultural conversion was not yet ensured. Some people considered it ‘just a miscommunication’ and underestimated the real root of the problem: the missing cultural transformation of the Church in Poland. The true crisis was only about to occur, and reality was about to be uncovered.

Like in the oceans, where big waves come in groups of three, the Church in Poland was about to be hit by three big, rolling waves.

The first wave: Gdansk, 2018

It was precisely in Gdansk were the Soviet Empire began to collapse. The city made history in 1980 when an electrician by the name of Lech Walesa founded Solidarity, the first trade union in a communist country. Alongside Walesa was an eccentric chaplain, Fr. Henryk Jankowski. All across Poland, the priest was as famous as Walesa, and his popularity in Gdansk resulted in a big statue of him in front of St. Bridget’s Church, an important landmark of the Solidarity movement.

In December 2018, now 64-year-old Barbara Borowiecka told Gazeta Wyborcza that Jankowski abused her ‘between 10 and 20 times’ (Aksamit Citation2018). She claimed she was 12 when the abuse began. The priest was well known in the whole neighborhood as ‘the one who chased the kids,’ Borowiecka reported to the paper.

The report provided many graphic details of Jankowski’s long trail of sexual abuse. For instance, there is the story of a Borowiecka’s friend: she was raped by the priest, got pregnant and, after telling her father, committed suicide. The article also recalls the words of Archbishop Tadeusz Goclowski, the previous archbishop of Gdansk now deceased: ‘A serious problem that has been worrying me for several years is your attitude toward young men and boys’ (Aksamit Citation2018), suggesting that the secret about the priest was not as private as it was previously thought. In March 2019, the statue of Jankowski was removed by the outraged Gdansk community in a scene that bore a resemblance to the tumbling of many statues of Lenin and Stalin at the fall of the Communist Regime in Eastern Europe, only with a smaller crowd and an added special symbolic touch: protesters put children’s underwear in the statue’s hands.

Public uproar only intensified when people learned that the case had been reported to the Archbishop three months earlier, and that he had done nothing. Moreover, Archbishop Slawoj Leszek Glodz wanted the statue back on the podium after it had lain on the ground for several hours. It was Solidarity leaders themselves who decided to take it down for good.

After nine months of silence from the side of the curia, Glodz closed the case. In a letter sent to Borowiecka, one of the aforementioned victims, the chancellor of the diocese explained that it was the Vatican Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith that halted the investigation, stating, ‘it is impossible when the person is dead’ (Więź Citation2019). The case was closed as of October 2019.

The public did not stay silent after this decision. On November 3, 2019, a group of 100 faithful came to the Gdansk curia to call for the resignation of Glodz: ‘Christ says that we need to care about the little ones, the victims of abuse. We are to care of persecuted priests. We should seek out all those who have left the Church shocked by what is happening,’ Justyna Zorn, one of the organizers of the protest, told Gazeta Wyborcza (Gałązka Citation2019).

Facing the threat of protests in front of the nunciature, Archbishop Salvatore Pennacchio, Apostolic Nuncio in Warsaw, invited the faithful of Gdansk to a private audience on March 2, 2020. The group asked the Vatican Ambassador what has been done regarding the abuse of power by the archbishop of Gdansk in sexual abuse cases and what action will be taken as reparation for the victims (Dobiegała Citation2020).

The faithful of Gdansk also sent a petition to Pope Francis, asking him to intervene in the face of the forsaking of victims by their archbishop.

It is unclear whether it was a consequence of the public unrest, however, after the intervention of the nunciature in the Archdioceses of Gdansk, the commission to investigate the case of Jankowski was reopened in April 2020. In a letter published by Więź, the chancellor of the Gdansk curia announced that the Apostolic Nunciature in Warsaw requested Archbishop Glodz to investigate the case (Więź Citation2020a).

The commission is still working ‘to gather information, in a historical and moral aspect" regarding the prelate, while ‘the collected material will be forwarded to the Apostolic Nunciature in Warsaw.’ Such action, the chancellor of the curia argued, results from the decision of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, which had already ruled that canonical criminal proceedings against the deceased were impossible (Więź 2020).

Therefore, the commission is not technically working on a trial of the deceased cleric. Instead, it is studying the moral grounds of searching for truth in the past – mainly for peace and justice for those who could have possibly been hurt by Jankowski.

When this investigation is finished and sent to the Vatican, it is up to the Holy See to decide how the case will go forward. One possibility is that Glodz will face another investigation – of abuse of power. It is unlikely that he be removed as archbishop, as he is retiring this very year, 2020.

The second wave: Tell No One, 2019

May 11, 2019, the day of St. Stanislaus, one of the major yearly festivities of the Church in Poland, was the date chosen by producers and brothers Marek and Tomasz Sekielski to premiere their long-awaited documentary Tell No One. The documentary’s director, Tomasz, an experienced television journalist, anchor and investigative reporter, depicted what is rarely seen on video – victims confronting their abusers.

The result was a powerful portrait of sexual abuse by Catholic clergy in Poland. The movie is like a blow to the face of the hierarchy in front of the whole country. This is not a coincidence: ‘I hope that everyone who sees the movie will think about it for several days. And that this film will actually hurt,’ were Tomasz’ explicit intentions.

More precisely, he aimed directly at the Church hierarchy in Poland. He thought that Polish bishops were not following the steps marked by Pope Francis, but instead remained frozen, unresponsive and unreactive, as if this problem was not their problem.

In fact, that was the bishops’ reaction to the first movie accusing priests of being sexual predators – Clergy, released in the fall of 2018. The story was considered ‘a scandalizing image far from reality’ by some, and a ‘blockbuster image of the modern Polish Church’ for others. Nearly two months after its premiere screening, over 5 million people watched it in movie theaters (Gazeta Wyborcza Citation2018). On that occasion, the Polish episcopate was neither shocked nor wanting to talk about it. The case was thrown into the basket of ‘it’s just fiction, so there’s no reason to worry about it.’

Even if Clergy was a fictional and much exaggerated image of the problems that the Church is facing, it was at the same time the first sign of a cultural change in the public sphere – that talking publicly about the dirty laundry inside the Church was considered acceptable. It was like crying ‘the Emperor is naked’, as in the H. Ch. Andersen’s tale: people saw the problems inside the institution and the Church couldn’t avoid it any longer.

The film had a major impact on society and public debate about what Poles can say about the Church in the public sphere; nevertheless, it did not have much impact on Church communications and structures. ‘It’s just fiction’, was the motto.

On the contrary, cases in the documentary Tell No One, released 8 months later, were true. Real people were harmed. The wrongdoings and secrecy of the Church were in plain sight for everybody to see.

In the introduction of this paper, I told the story of a woman who confronted her abuser. Thirty years earlier, the priest abused her around the time of her First Communion. In a conversation with the elderly cleric, who is now leading a peaceful life in a Church retirement home, she finds out that her suspicions about not being the sole victim were confirmed. When she walks out from the room, devastated, she cries out to the hidden camera: ‘I just knew there were other victims, I knew it!’ She had never reported the crime to anyone but kept the secret for 32 years, just as the priest had asked her to do.

A second male victim also confronts his abuser in the film. Fr. Franciszek Cybula was a well-known figure in Poland, as for many years he was the personal chaplain of Lech Wałęsa, legendary leader of the Solidarity union and later President of Poland.

When the victim, who was in primary school when the abuse occurred, confronts his abuser, Cybula downplays his responsibility by saying, ‘You wanted it, you wanted that little closeness.’

Cybula died just before the film was finished. The documentary shows his funeral, where the Bishop Glodz of Gdansk and many other high-profile priests praised the deceased cleric. The bishop knew about the allegations: they were officially reported three months before Cybula’s death.

Tell No One was the first Polish large-scale journalistic investigation conducted using crowdfunded money that brought to light all abuse mechanisms written about in literature: secrecy, a web of silence and manipulation around the victim, abusing children from families in need, incorrect Church response, abuse of power, but above all, a sad phenomenon – a Church terribly afraid to face the truth and lacking proper investigation of the cases, not to mention a complete lack of compassion toward survivors.

Public reception of the film, with only a few exceptions, was overwhelmingly favorable. Both conservative and liberal media praised the filmmakers for the courage displayed in showing the grim reality of handling sexual abuse in the Church in Poland. For the first time in Polish public opinion, the victims were put in the ‘Spotlight,’ so to speak, and this brought the country to a halt.

Social media reaction mirrored the reaction seen in mainstream media: ‘The film is powerful, hard to watch, very accurate and very painful. The Sekielski brothers’ documentary may become a part of the Polish-Polish ideological war over values. But it shouldn’t, because it is a fine, professional and engaging work,’ commented the Polska Times (Citation2020).

In fact, if the ideological war was about to happen, it would be declared by the right-wing conservative media that usually put themselves in the role of Church defenders. After Tell No One’s release, even the right-wing website wpolityce.pl published these words written by Lukasz Adamski, journalist and film critic: ‘The documentary by the Sekielski brothers is shocking and painful. Without looking at the political or religious debate (…) this film is about victims looking into the eyes of those who hurt them.’Footnote7

Other media headlines included: ‘An important lesson for all of us,’ ‘The Irish scenario in practice,’ and ‘This film needs to cause an earthquake in the episcopal conference.’Footnote8 Jesuit website deon.pl published editorials of two leading experts on abuse. One of them, psychologist Fr. Jacek Prusak SJ, wrote: ‘How to believe after the Sekielski film? We need to go through a period of mourning.’Footnote9 Fr. Zak stated: ‘Pastors understand they need to see what skeletons they have in their closet.’Footnote10

What commentators both in secular and catholic media had in common is the mix of compassion, desperation and anger: ‘After a two-hour screening, the viewer will not only be deeply moved, but above all, very angry. He will be convinced that the principle of ‘zero tolerance’ repeated by bishops is simply just an empty phrase,’ Tomasz Krzyzak wrote in Rzeczpospolita, adding: ‘There will be no spectacular dismissal of bishops after the documentary, although questions about their responsibility in some cases must arise’ (Krzyżak Citation2019).

Krzyzak had foreseen something that the faithful felt under their skin – that the film will be an earthquake that will not cause bishops to change. And this made the faithful visibly lose trust in the Church.

Commenting on the film, a priest working in the Polish Episcopal Conference for many years said, ‘Unfortunately, only movies like this one can force the hierarchy to face the problem. In this sense, the documentary could help the bishops. But I am afraid the film will not be enough to wake up the Episcopal Conference, because bishops will only wake up if Pope Francis requires the resignation of one of them for disregarding the law’ (Guzik Citation2019b).

The faithful did not believe in real change either. In a poll conducted nine months after the release of the documentary, the Church noted a visible decrease in trust. In 2016, 58% of respondents said they trusted the Church; in 2017, the number dropped to 52.7%; by the beginning of 2020, the number was down to only 39.5 percent (Dąbrowska Citation2020).

Those who put a lot of trust in the Church made up 29.9% in 2017, compared to only 15.7% in 2020. shows the impact that Tell No One and the Church’s response had on the Church in Poland.Footnote11

The signal sent by the faithful was clear in as early as July 2019. A public opinion poll conducted by the biggest poll provider, CBOS, showed that 87% of Poles stated that an insufficient reaction from the Church to the cases of pedophilia is lowering the authority of the institution.Footnote12 Fifty-eight percent of the respondents said that the scale of abuse in the Catholic Church is bigger than we know from the cases that were already published. Only 30% of the respondents thought that the problem is exaggerated by the media. Worth noting is the fact that 51% of the respondents thought that the Church’s reaction to the documentary was not sufficient. Let us look, then, at the actual reaction.

Only after the documentary premiered, the dioceses revealed what happened to the predatory priests. Three of those featured in the film were removed from priesthood – two before the film’s debut, and the third filed a request for laicization after the documentary’s release. Two more were banned from public ministry but remain in priesthood.

The Church's response: things start moving

Tell No One was the first media investigation of child sexual abuse on a large scale in the history of the Church in Poland. The Sekielski brothers’ documentary had done in Poland what the famous Spotlight investigation did in the United States: tell the story of sexual abuse by clerics that was obstructed by Church authorities.

The film displayed to Polish people in full scale the vast dimensions of the problem on their own land, which most considered the most Catholic country in the world. In the blink of an eye, a ‘foreign problem’ was exposed in their own backyard, accompanied by the realization that many people in the Church knew it, lied about it and were unable to do the right thing by taking the side of the abused. On the contrary, they preferred to protect the Church’s good name and ignored the victims and their suffering.

The documentary hit the Church in Poland with the force of an earthquake. And not many expected as quick and emphatic a reaction as the one it received within only a few hours of its release – a Copernican revolution, precisely in the homeland of Copernicus.

The first to react was the Primate, Archbishop Polak. Immediately after the release of the movie, Polak issued a video statement saying, ‘The enormous suffering of the people who have been hurt triggers pain and shame.’ Then, after referring to the new papal legislation on sex abuse, he added: ‘No one in the Church can escape responsibility.’

An equally emphatic statement came from Archbishop Gadecki, the president of the Polish Bishops’ Conference. His change, after his unfortunate comments at the press conference in March 2019, when he said that pedophilia in the Church is actually an ‘ideologically coined’ slogan and ‘quite skillfully chosen’ by the enemies of the Church, was remarkable. He said: ‘With sadness and compassion I watched the film produced by Mr. Sekielski, for which I am thankful to the director. (…) In the name of the Polish Bishops’ Conference I would like to say sorry to all those hurt. I am well aware that nothing is going to take away the harm experienced,’ and adding, ‘I am sure that this film will contribute to an even stronger condemnation of the crime of pedophilia, which cannot take place in the Church’ (Wiara Citation2019).

Not everybody in the Church in Poland took that side of the debate. For example, Archbishop Glodz of Gdansk told the Polish TV news program Fakty: ‘I don’t watch any old stuff.’ But the trend was unstoppable even for him, and under the pressure of the Bishops Conference, he had to apologize soon after, stating he ‘was not willing to offend any of those harmed by church sexual abuse.’

So, what in fact had changed in Church authorities after Tell No One?

Three elements must have come to mind for the bishops: we can no longer deny the problem, as it was customary for decades; we can no longer ignore the victims, because now they have the attention of the whole society; and we can no longer ignore the faithful, who are raising their voices and demanding decisive action and even resignations.

There were actually some expected dismissals in June 2019, when Maltese Archbishop Charles Scicluna, Adjunct Secretary of the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and Pope Francis’s point man on sex abuse, travelled to Poland to address both the bishops and the diocesan delegates for the protection of children.

His trip was scheduled months before the release of Tell No One, and even before the February Vatican sexual abuse summit, but it was hard not to see the connection between the lack of action and change of heart in the Polish bishops and him coming to the country.

‘Victims are not enemies of the Church,’ Scicluna told the Polish Episcopate, ‘but wounded sheep.’ Scicluna praised the plans and procedures decided by the Episcopal Conference throughout the years. But then he asked: ‘What are the facts?’Footnote13

In an interview for National Polish Television, TVP, Scicluna also encouraged the victims to report both sexual abuse and abuse of power. Referring to Vos estis lux mundi, the Maltese archbishop stressed that, ‘for the first time in the history of the Church, a norm establishes a positive obligation to denounce.’

He might not be a papal envoy, but his visit was a threshold of hope. Two months after the visit, the Primate Polak was equipped with the Office of Child Protection, operating right inside the building of the Bishops headquarters in Wyszynski Square in Warsaw.

To lead this brand-new child protection unit, Polak named Fr. Piotr Studnicki, and the episcopate approved the appointment. His background in communications with a degree from a Pontifical University, his academic expertise as professor of crisis management for the Church and his involvement as Cardinal Dziwisz’s spokesperson in Kraków indicates that transparency would be considered an indispensable element in dealing with the sexual abuse of minors. His experience includes the issue of sexual abuse, since he served as an unofficial spokesperson of the Child Protection Center in Kraków for over a year.

Studnicki saw this assignment as a chance to start new chapter in fighting sexual abuse in the country. Much like the Vatican’s Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors, the Polish Office of Child Protection does not deal with specific allegations, which is the task of special diocesan advocates. Instead, it deals with safeguarding procedures and helping survivors of sexual abuse.

The first victory for the Primate and Studnicki was the voting on the St. Joseph Foundation – a fund for victims, for which the bishops gave the green light as recently as October 2019. It is an organization that will be able to concretely help victims after they report a case. It will offer professional help immediately for those harmed, including legal support, psychological therapy and educational scholarships, among other services.

Most importantly, the funds come directly from the pockets of priests and bishops, not from donations of the faithful. A lay woman, Marta Titaniec, was appointed to chair the foundation and Robert Fidura, a victim of child sexual abuse, was given a seat on its advisory board.

It is a fact that, after the documentary Tell No One, there was a visible change in public discourse. Bishops were talking publicly about the issue, something previously unheard of.

Yet, there was an important element missing: making survivors a priority. The conversion of heart that Pope Francis was insisting with his words and with his deeds (the Argentinian Pope made meetings with victims an almost weekly routine) was nowhere to be seen. Bishops were still reserved about meeting with them.

In summary, Tell No One promoted a big change: more people, more resources and more communication were put into protecting minors and taking care of victims of sexual abuse by the clergy.

Nevertheless, it was an incomplete turnaround. That year, Francis closed the circle on the issue with his Vos estis lux mundi, a papal document establishing the responsibilities of bishops in case they failed to adhere to the norms regarding sexual abuse accusations. It was the fulfillment of the responsibility and accountability principles preached in the Vatican’s Meeting on the Protection of Minors in the Church. Bishops should feel responsible and accountable not only for their deeds but also for those of their brothers in the episcopate.

But no Polish bishop dared to force Archbishop Glodz of Gdansk to investigate the Jankowski case, and neither did Apostolic Nuncio Penacchio.

It is possible that the Holy See might just be patiently waiting until the bishop of Gdansk reaches the age of retirement in 2020. Nevertheless, doing so would be a contradiction of those principles proclaimed from Rome and would leave for his successor the difficult and unpleasant task of not only investigating Jankowski but also making his predecessor accountable for not fulfilling the new Church laws and not standing by the side of those who were hurt.

The open case of the auxiliary bishop of Kraków

It was during the coldest days of winter in Poland, February 2020, when the case involving incumbent auxiliary bishop of Kraków, bishop Jan Szkodon, a personality of the local Church for decades with a crystalline reputation, emerged.

For decades, Jan Szkodon was a significant figure in Kraków – the archdiocese of St. John Paul II. From 1979, he was the spiritual director of the seminary for over a decade, until he was consecrated bishop in 1988. He was known for his deep spirituality and artistic sophistication – he enjoyed painting on canvas and writing poetry. For years he was seen as a sensitive figure of the Church in Kraków (Guzik Citation2020).

Unexpectedly on February 2020, a year before his retirement, a young civil servant and mother accused him of abusing her in 1998, when she was a 15-year-old girl. In an article published by daily newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza, Monika (not her real name) claimed she was often a guest at the bishop’s apartment, and ‘Whether summer or winter, he always felt hot,’ she recalled. ‘He took off his cassock and his shirt and remained in tank top and trousers unzipped halfway’ (Wójcik Citation2020).

According to the woman, Szkodon encouraged her to undress, touched her breasts, thighs and bit her ears. ‘Monika, God has sent you to me. He wants to teach me tenderness through you’ (Wójcik Citation2020), he allegedly told the girl.

The day before the Polish paper published its report, Szkodon released a statement declaring his innocence: ‘These accusations violate my good name, which I intend to defend’ (Archdiocese of Kraków Citation2020a).

Reactions from the bishops varied from distancing themselves from the case altogether to standing in defense of bishop Szkodon to defending the victim.

Archbishop of Kraków Jedraszewski did not release any official statement. His spokesperson informed the media that Szkodon had left the archdiocese for an undisclosed location and that ‘the archdiocese was not aware of the accusations that the bishop is facing’ (Skowrońska Citation2020).

Archbishop Emeritus of Kraków Cardinal Stanisław Dziwisz, in a statement released a day after the accusations, stated that ‘the allegations hurt many people for whom Bishop Jan is an authority, a father and a friend. We are all expecting the allegations to be thoroughly and quickly explained’ (Archdiocese of Kraków Citation2020b).

When Gazeta Wyborcza published the exposé, the case of Szkodon was already being investigated by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. Polak commented on the case: ‘Any information of that kind brings pain to the Church,’ he said at a press conference. ‘It is a call that we shall always care about – the safe environment for children in the Church. And it is a call to each and every one in the Church.’

The alleged victim of Szkodon did not use the diocesan channels to denounce. In May 2019, she reported the case directly to the Nunciature (she also reported to state prosecutors in August and public officials opened an investigation, which they subsequently had to close due to the fact that the statute of limitations had expired).

‘The first letter on this matter arrived at the Nunciature on May 27, 2019 and was forwarded to the Holy See the same day,’ the Nunciature said in a February 12, 2020 statement (KAI Citation2020).

Nevertheless, it took eight months for Church investigators to listen to the alleged victim: Monika was not asked to testify until January 2020. During that time, Szkodon was performing his duties as an auxiliary bishop of Kraków. On the day of her deposition, January 23, 2020, the nuncio Pennacchio met with Monika personally.

If the bishop is found guilty by the Vatican, he could be the first Polish bishop to not only be removed from office, but also expelled from the priesthood.

If this case was not shocking enough, an even stronger blow was about to hit the Church in Poland in 2020.

The third wave: Hide and Seek, 2020

Almost exactly a year after the first part of the tell-all documentary revealing tales of sexual abuse, the Sekielski brothers released the second part of their investigation called Hide and Seek.Footnote14 This time it documented not only the sexual abuse of children by priests, but also the abuse of power by the Church hierarchy. This time around, the filmmakers once again carefully chose an important date for the Church in Poland – the documentary premiered just before the celebrations of the Centenary of Karol Wojtyła.

The film showed that, although child protection procedures in the Church have technically been in place for years, many Church authorities were still indifferent to the plight of the victims of sexual abuse.

The film tells the story of brothers Jakub and Bartek Pankowiak, who were abused in their own apartment, while their parents were in the kitchen next door. Jakub was 13 years old when he and his family – his parents and three siblings – moved to the new parish apartment in Pleszewo in the Diocese of Kalisz in central Poland in 1996.

His father was the organist at the parish church: ‘We thought it was a gift from heaven,’ Jakub said about his new home. Even if it was modest, it was more spacious than their previous household, and the parish subsidy meant there was more money available to direct at the care of one of his brothers who was terminally ill.

‘We were the fish that were the easiest to catch,’ said Bartek Pankowiak, Jakub’s younger brother. He was 8 years old when the abuse started. Both brothers were abused by Fr. Arkadiusz Hajdasz, but at first neither knew the other was also being victimized.

The priest was allegedly giving the boys guitar lessons while their parents were busy in the kitchen, but instead he was kissing and fondling each boy in their bedrooms. The brothers were afraid to tell their parents: if their father lost his job as parish musician, the life of their sick brother would be put in danger.