Abstract

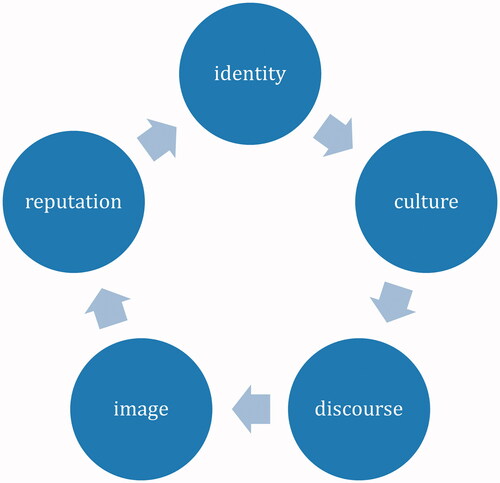

This article is mainly aimed toward those responsible for communications in ecclesial organizations that are experiencing vulnerability. It integrates the perspective of organizational communication with ecclesiological contributions. The first part notes that vulnerability is a common trait of civil and ecclesial organizations, both in the passive sense (potential to be hurt) and in the active sense (capacity to do harm). In the second part, a circular conceptual framework of the process of communication, devised by several academics from the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross, is developed and applied to the Church. In pursuing adherence to reality, this is a valid theoretical framework for inspiring the communication management that is required for dealing with errors and failures. In the description of the process, references are added to the issue of fragility in each of its phases: identity, culture, discourse, image, and reputation. A key word in this sequence is ‘consistency’ (between what an institution is, and how it considers itself; what it does, and what it says). In the third part, this ‘realistic’ conceptual universe is applied to the issue of the abuse of minors committed by ministers of the Catholic Church, guidelines for the communications team are suggested (investigate, listen, accompany, repair), and seven criteria for proper reporting are proposed.

1. Vulnerable organizations: fragile and dependent

Vulnerable comes from the Latin noun vulnus (‘wound’) and the particle abilis (‘able’). It indicates that something or someone is ‘capable of being physically or emotionally wounded’ (Merriam-Webster). We speak of offenses, violations, afflictions, torments, and contusions in the body or the spirit. An information system with security flaws is vulnerable to attacks by hackers, a malnourished person is more vulnerable to disease, and a young person without an elementary education is vulnerable to cultural or political manipulation.

Broadly speaking, this adjective indicates a passive condition: the reality of being hurt. ‘There is a scale of disability on which we all find ourselves,’ states Alasdair Macintyre (Citation2001, 91), one of the authors who has most vindicated the recognition of people’s vulnerability—a ‘fundamental feature of the human condition’ (Citation2001, 18)—as a central aspect of moral philosophy. MacIntyre links vulnerability with dependence, a condition that is most evident in childhood and old age but that accompanies us throughout our whole lives.

The Coronavirus pandemic of 2020 is perhaps the most relevant example of global vulnerability in recent decades. In addition to the millions of sick and hundreds of thousands dead worldwide in the first half of 2020, a great deal of the world’s population was forced to give up something as essential as physical contact.

In the months of lockdown due to COVID-19, millions of human beings discovered that we were fragile and experienced in a new way the mutual dependence and the bonds that unite us with neighbors, healthcare workers, and other essential workers, whose services often exceeded their pay. As Pope Francis stated during a pandemic prayer event: ‘We have realized that we are on the same boat, all of us fragile and disoriented, but at the same time important and needed, all of us called to row together, each of us in need of comforting the other (…). We too have realized that we cannot go on thinking of ourselves, but only together can we do this’ Pope Francis (Citation2020).

After total lockdown, there was a lengthy period regulated by strict rules of social distancing. Those months of physical separation meant the cessation or transformation of many activities. In a timely study, for example, Campbell (Citation2020) reflected on the shift in the activities of many Christian institutions as well as those of other religious confessions. The weeks of lockdown also led to economic hardships and job losses. In 2020 humanity discovered that it was more vulnerable and interdependent.

As a verb, to harm is synonymous with to injure. Its action is transitive: it injures someone or something. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines harm as ‘to damage or injure physically or mentally.’ Continuing with the example of COVID-19, we would include here the cases of persons or institutions whose fragility consisted in not being up to the task: those who more or less consciously put their own economic, political, and institutional interests ahead of the common good.

If, as MacIntyre recalls, vulnerability (in its dual aspect, active and passive) is connatural to the human condition, it will necessarily accompany the life of the organizations. Because beyond a mere technical system, each organization is a set of people, grouped around three fundamental elements: human actions, human necessities, and ‘a formula or way of coordinating actions to meet those needs’ (Pérez López Citation2006, 15).

In the field of organizational communication, studies on communication and vulnerability proliferate—especially from the perspective of the communication management required for disasters or crises suffered or caused by organizations, both civil and ecclesial. Some relevant examples are the books by Walaski (Citation2011), Griffin (Citation2014), or Fearn-Banks (Citation2017). The last one lists as many as 49 factors that usually trigger crises or disasters in businesses and institutions (Fearn-Banks Citation2017, 299). De la Cierva is the author of two specific treatises on crisis communication in the Church, in which a vast bibliography can be found that is closer to the object of this article (De la Cierva Citation2014, Citation2018). The same existence of many studies on the subject is another indirect corroboration that organizations, like human beings, are vulnerable and subject to a certain dependence.

To accept one’s own vulnerability (recognizing it as inevitable and seeing it as possible in the present moment) is a necessary condition for channeling it effectively, limiting the damage that it entails, and promoting alternatives to overcome it in the future. No improvement is possible without this acceptance. It is the common foundation and starting point of the literature on crisis prevention and management.

2. The process of communication and vulnerability in the Church

After this first approach to the issue of the fragility of the organizations, the second part of the article will attempt to offer a theoretical framework that can serve as inspiration in the institutional communication of harm caused by an organization or one of its members.

We are going to use a circular model of the communication process in organizations as our foundation (see ). It is the result of a dialogue between various teachers of the communications faculty of the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross at the beginning of the twenty-first century. It integrates and organizes concepts and intuitions of different organizational communications scholars, and it contributes other original concepts. The first published version is credited to Professor Alfonso Nieto (Citation2006, 11–18). A little later, Juan Manuel Mora published a development more connected with the professional activity of the communications departments, which incorporates the reference to ‘institutional discourse’ (Mora Citation2006). In 2016, Ohu presented a description in English, comparing it with other models (Ohu Citation2016).

This is a realistic paradigm, where the purpose is not to obtain consensus or popularity at any cost, but rather adherence to reality, meaning that that identity and perception (truth and image) coincide in the mind of the audience. This ‘faithful image’ of reality (Nieto Citation2006) produces beneficial and valuable long-term effects, both inside and outside of organizations: cohesion, reputation, and trust.

In addressing each phase of the organizational communication process, the link between vulnerability and the Church is emphasized. Along with the contributions of the authors dealing with communication and organization (Gregory, Griffin, Haslam, Schein, van Riel and others), the following description includes some ecclesiological references, drawn from the Catholic tradition. Understanding how the Church considers herself is essential for a successful communicative response to the vulnerability that is consistent with her being and mission.

2.1. Identity and vulnerability

The process of organizational communication begins with reflection on the institution’s identity, that set of traits that form its ‘personality’ and distinguish it from others: its origin, history, mission, and values. As Mora states, ‘if those who are part of the organization are not aware of their collective identity, of their corporate purpose, it is easy for problems of disorientation, fragmentation, and division to arise’ (Mora Citation2020, 41, our translation). Reflection on the question of ‘who am I?’ is usually expressed in statutes, codes, and charters. The identity points to the truth, to the being of things, and to the concrete reality of a person or organization.

Van Riel and Formbrun (Citation2007, 67–70) emphasize that the identity of an institution is centralizing (a factor of convergence among all its participants), differentiating (referring to the most original and unique elements), and stabilizing (connecting past, present, and future, ensuring continuity). The institutional identity is vivifying: it is the north star of the activity of communication.

The organization’s identity is a received intangible, which is not generated as a product. It is simply expressed in the communication process. Focusing on identity avoids the danger of turning communication into a kind of dress-up closet for the institution that fits the dress code of every occasion (as if the key were consensus, to be accepted at any cost); or, in a different vein, it avoids the danger of reducing communication to technical aspects, when it is the contents that are essential.

Each institution is marked by its history, its charism, its founder, its statutes, and the geographic area in which it works. In the specific case of the Church, its institutional genome, moreover, is based on the characteristics derived from its membership in a superior entity, ‘people of peoples,’ says the Second Vatican Council, which makes it both universal and localized (Vatican Council II Citation1964, 13). Other differentiating elements that necessarily configure a particular style of communication are the following: having a structure and certain means instituted by Jesus Christ, a doctrine that calls for faith, confers hope, and that manifests itself in charity; an evangelizing mission with a universal scope, etc. (Catechism of the Catholic Church Citation1993, 784–750).

Where do we find vulnerability in the identity of the Church? In her most spiritual dimension, as the mystical body of Christ, Christians have (with Saint Paul) affirmed over the centuries that the Church is ‘holy and without blemish’ (Eph. 5: 27). However, in her most visible, human, and institutional dimension, she shares perfectibility and fallibility with every other organization involved in social action: the Catechism of the Catholic Church recalls that ‘all members of the Church, including her ministers, must acknowledge that they are sinners’ (Citation1993, no. 827). The very Founder of the Church was denied three times by the one who would be His future vicar and sold to death by another one of His twelve immediate collaborators. In number 33 of Tertio Millennio Adveniente, Pope John Paul II wrote: ‘Hence it is appropriate that, as the Second Millennium of Christianity draws to a close, the Church should become more fully conscious of the sinfulness of her children, recalling all those times in history when they departed from the spirit of Christ and his Gospel and, instead of offering to the world the witness of a life inspired by the values of faith, indulged in ways of thinking and acting which were truly forms of counter-witness and scandal’ (Pope John Paul II Citation1994).

Some of Christ’s harshest imprecations allow us to intuit that the nascent Church must have already had to face the scourge of some kind of child abuse: ‘Whoever causes one of these little ones who believe in me to sin—we read in the Gospel of Saint Matthew and the other synoptics— it would be better for him to have a great millstone hung around his neck and to be drowned in the depths of the sea’ (Matt. 18: 6).

Contemplating the reality of the human being and the earthly journey of the Church leads to a first observation that, although obvious, is sometimes overlooked: humans are not only potentially fallible, but we truly are fallible. From a Christian perspective, only God is not so. We cannot omit this observation when considering the deepest identity of the Church. Imperfection forms part of her very being. Recognizing this is a sign of lucidity: accepting one’s mistakes is the indispensable requirement for turning one’s gaze to one’s own values and, from there, becoming promoters of corrective measures.

2.2. The culture of ecclesial organizations and vulnerability

Secondly, identity is embodied in a culture: a collective way of working, organizing, acting, and reacting (what do I do?, how do I behave?). Nieto defines the organizational culture as ‘a collection of attitudes, behaviors and ways of being of an institution’ that express ‘how it relates with its members or persons directly linked to it, as well as with the public to which it directs its products or services’ (Citation2006, 115). Corporate culture is, on the one hand, a ‘tangible expression of the mission’ (Nieto Citation2006, 323). But on the other it has a dimension of intangible good, ‘shared and stable which provides meaning and predictability’ (Schein Citation2004, 14). In coherence with the previous phrase, it would be ‘foreseeable,’ for example, that the culture of an institution that is more or less linked to the Church reflects such essential elements of her identity as social charity, the primacy of grace, the value of each person, evangelizing zeal, pluralism, etc.

The danger in this phase of the process is that the corporate culture will fail to make the organization’s identity transparent, or may even hide it. Gregory and Willis observe that there will always be breaks between values and actions, since ‘organizations are made up of people who are not perfect’ (Citation2013, 66).

As was said earlier based on MacIntyre’s assessment, people forge organizations, but it is also certain that organizations influence individuals. In his study on the psychology of institutions, Haslam approaches the individual-group nexus from this dual approach to social identity: although it is true that individuals contribute to the formation and development of organizations, there are numerous empirical studies that also show that ‘the human groups or organizations transform people, and this makes institutions more than a simple aggregation of their individual contributions’ (Haslam Citation2015, 29, our translation).

Haslam’s approach to social identity is based on the hypothesis that ‘the ability to think as a “we” and not just as an “I”, encourages people to engage in meaningful, integrated, and collaborative organizational behavior’ (30). He distances his approach from depersonalization theories. In this sense, ‘the fact that groups or organizations transform in a certain way the psychology of the individual is seen not as a necessary evil, but as an essential good’ (30, our translations). Applied to the topic at hand, it could be said that organizations have the potential to reflect on their own errors and to establish corrective mechanisms derived from that proposal of meaning that extends over a longer period of time than that of the people who make up the organization at any given moment in its history.

From another perspective, Edgar Schein speaks of the corporate culture as a ‘common set of assimilated responses’ (Schein Citation2004, 83). In times of crisis, when the organizations encounter their vulnerability, ‘they reveal aspects of the culture that had already been built’ (104). And at the same time, the responses to the crisis ‘provide huge opportunities for culture building’ (108).

Church institutions are equally vulnerable in this phase of the process. Thus, some ecclesial structures struggle to ensure that phenomena such as careerism or spiritual worldliness and inaction in the face of certain abuses or clericalism do not become a de facto part of the corporate culture, in opposition to essential principles of Christian identity such as service, humility, austerity, the pursuit of the common good, etc. In his 2014 Christmas message to the Roman Curia, for example, Pope Francis alluded to fifteen diseases to which this central governing body is exposed, including: a sense of immunity, materialism, functionalism, lack of faith, rivalry or vainglory, and the spreading of rumors (Pope Francis Citation2014). The Pontiff also referred to the inadequate response to errors in administration or to errors in the communication of doctrine, among others.

At this point, Anne Gregory’s observation seems appropriate. She refers to the communications department as ‘a brand guardian,’ which ensures consistency between an organization’s being and action (Gregory and Willis Citation2013, 126). A strategic function of the communications department is to detect inconsistencies that are introduced into an organization’s ways of doing things and that blur the projection of its identity. It needs to seek transparency in the strict sense: that it be itself transparently.

The same author then refers to the person who directs communication as the ‘fixer in chief’ since, in addition to being the guardian of values, he or she promotes measures to correct those behaviors that are distant from the institutional identity, in harmony with and at the service of those who govern it (122).

The communications department then becomes a kind of internal cultural leader: a unit that looks at the whole organization through the eyes of communication, which preserves and promotes its fundamental values, and which seeks to exercise a kind of inspirational function over the whole. The key task is to be vigilant so that isolated inconsistencies do not affect or become staples of that culture. In this phase, the inseparable connection between action and communication becomes clear.

2.3. Ecclesial discourse and vulnerability

The third word of the institutional communication process is ‘discourse’ (what do I say?). We project identity and culture in a discourse, in words and rationales that give public reason for the institution’s very existence and its work: ‘The works give meaning to actions, they serve to explain the motivations and help to interpret the goals’ (Mora Citation2020, 42, our translation).

The communicator tries to guarantee that the organizational rhetoric corresponds to the reality of the institution, although he or she also attends to the ‘aspirational’ value of the declarations. This is the phase in which those who deal with communications tend to be the most active. The web page of a diocese is public discourse, as is a press release or conference, its activity in social networks or the public appearances of those who govern it. The efficacy of institutional discourse, as Mora recalls, depends on it being clear, emphatic, and meaningful for the audience (Mora Citation2006, 171).

Generally, Church organizations have been pioneers in developing their own public discourse with a primarily evangelizing purpose, first through art, oral tradition, and culture, and later through the media (Carroggio, Gagliardi, and Mastroianni Citation2013, ch. 2). In the last century, the Catholic Church – and numerous Christian confessions – has also led a remarkable expansion of its activity of corporate communication, in parallel with other organizations, as seen in the proliferation of educational projects with this purposeFootnote1 or in the generalization of communications departments of ecclesial organizations encouraged by the Holy See.Footnote2

The progressive professionalization of the communication of Catholic institutions has favored the passage from an instrumental relationship (to catechize) to a more dialogical and integrative paradigm, in which ‘the cultivation of friendly relations based on mutual reverence between the Church, people and groups’ is encouraged (PCSC [Pontifical Council for Social Communications] Citation1971, 175). It becomes clear that it is not enough to ‘use’ the media to spread the Christian message, but that ‘it is also necessary to integrate that message into the ‘new culture' created by modern communications’ (Pope John Paul II Citation1990, 37), to form part of the great conversation that takes place in them.

In this context, the institutions of the Church also understand that acknowledging errors, asking forgiveness, and dialoguing with difficult and even provocative questions that can arise in this relationship are the appropriate paths to their mission, consistent with their identity. Succeeding in discourse, in the face of negative events that also take place in the Church, can end up becoming part of that ‘evangelization of the smile’ that is produced when one succeeds in ‘giving priority to others, asking forgiveness, not criticizing, showing tenderness’ (Arriagada Citation2016, 125).

When damage is caused, discourse does not resolve everything, but it is still very important. Apologizing for mistakes allows the emotional connection with the offended party to be reopened; when I forgive, I free the other and I free myself, grudges are dissolved, and a new beginning is possible. Moreover, asking forgiveness reaffirms the commitment to the broken value. If, for example, an educational institution expresses sorrow over abuse and announces new preventative or disciplinary measures, it therefore reaffirms its fundamental intention to promote a safe environment for young people.

Words do not resolve the material reparations that correspond to each case (economic reparation, restitution of a good, medical attention, psychological counselling) but they have a real healing and clarifying effect. In such times words are the face and the heart of the institution.

These three stages (identity, culture, and discourse) are the ‘internal’ side of organizational communication, which mainly depends on one’s own initiative. The key word of this sequence would be consistency: among what an institution is, what it thinks of itself, and what it says and does.

On the other hand, the greatest breach of communicative legitimacy occurs when there is a contradiction between one stage and another, that is, between the declared and embodied values. When legitimacy has been undermined, the corrective action requires patience. It implies that the public discourse is focused, during a more or less prolonged period, on certain aspects connected with the damage done, taking away strength from other aspects that are also at the core of the institutional identity.

2.4. Image, reputation and vulnerability

The two remaining words (image and reputation) confirm the ‘external’ stage of the process, since the initiative falls less on the institution.

The ‘image’ is the answer to the question ‘how am I seen?’ It is not only formed from what the organization says, but rather the perceptions, actions, and words of many other actors all play a role: users of social networks, journalists, opinion leaders, individuals with positive and negative experiences that illuminate or cloud the way they see reality, etc.

In the digital culture—horizontal, participatory, open, connective: everyone can speak with everyone—the vulnerabilities of people and organizations are more apparent than in the past, and they have become part of the image that individuals have of each other, both in civil society and in the Church. The transformation of the authority-Church binomial in the digital context has a huge presence in studies such as the one coordinated by Díez and Soukup (Citation2017).

In this context, which is the result of a technological change—of the analog or broadcast paradigm to the digital paradigm, described in an earlier article (Carroggio Citation2016, 19–39)—the organizations cannot claim, and do not have the capacity, to control the messages; now more than ever, the focus of communication must be placed on cultural inspiration.

‘Reputation,’ finally, would be the result of an image maintained over time (how am I regarded?). A good reputation is the main external value of institutional communication: a kind of prestige or social consideration. It is a massive generator of trust.

Mora defines reputation as ‘perceived quality,’ more specifically as ‘the set of positive values—honesty, quality, and leadership—that are usually attributed to an organization and that are calmly shared by large sectors of society’ (Mora Citation2015, 118). Viewed from within, a reputation is the result of ‘consistency between what the organization is, what it does, and what it says’ and of its sincere search to ‘contribute to the society in which it lives’ (Mora Citation2020, 79). For Griffin, ‘reputation is not actively projected; it is earned’ (Griffin Citation2014, 2).

Without a good reputation, a university does not attract students, an NGO does not receive aid, and a media outlet loses its audience. It is a fundamental factor for the institution’s capacity of attraction and facilitates the development of its educational, economic, evangelizing (etc.) mission in an enormous way. Reputation is like social credit, which is strengthened or lost according to good or bad performance and modulated by communication management.

Examples of this observation abound in management literature: errors and injuries produced by members of the organization may affect its reputation if they are not recognized quickly and dealt with effectively (Covey Citation2018). They cause pain that should have been avoided. If, however, they are acknowledged and corrected, mistakes could even strengthen the institution’s reputation in such fundamental areas as humility, credibility, and commitment.

It is striking that amidst the literature on vulnerability found in a cursory internet search, this concept is related to the capacity to be loved: a kind of sincerity that, by showing one’s emotions and fragility, makes us more lovable (Manson Citation2020). This semantic identification involves somewhat obscure logical stretches, but it indirectly confirms the intuition of many organizations that fragility and errors (in some cases, even crimes) do not always necessarily lead to a irreparable social trust.

The circular representation of the organizational communication process shows, among other things, that: (a) actions—the corporate culture and its corrections—communicate the institutional identity more effectively than words (institutional discourse); (b) the truth (the consistency between being and public expression) usually brings about positive results, even though recognizing it in moments of difficulty brings difficulties; (c) paradoxically, some defeats become a vehicle of expression of fundamental values that would be difficult to communicate in favorable circumstances: only from there is it possible to, for example, perceive key values for organizations such as credibility and trust. A central point is that there are no shortcuts to restoring trust after a serious mistake, while ‘recovery is about substance, not words alone’ (Griffin Citation2014, 251).

3. Organizational communication and the abuse of minors in the Church

In this third part the ‘realistic’ model just described is applied to the case of sexual abuse of minors or vulnerable people by ministers of the Catholic Church, of which there has been detailed knowledge in the past 20 years (before 2002 the Catholic dioceses did not have to send claims to Rome). The magnitude of this phenomenon is adequately reflected in the article ‘Child Sexual Abuse in the Context of the Roman Catholic Church: A Review of Literature from 1981–2013,’ by Böhm, Zollner, Ferget, and Liebhardt. Amidst a great deal of other data, for example, it notes that in the United States ‘between 1950 and 2002 found that allegations had been made against 4% of all U.S. priests active at the time, affecting 10,667 children’ (Böhm et al. Citation2014, 640).

The abuses have given rise to scandal, doubts, shock, and perplexity, both among the faithful of the Church itself and those outside. From our standpoint, they represent the greatest breach of communication legitimacy in the Church, because of the enormous contradiction between identity and conduct. At the moment in which we were becoming aware of this reality, John Paul II stated: ‘People need to know that there is no place in the priesthood and religious life for those who would harm the young’ (Citation2002).

In this crisis, the problem has not been the means of communication or other external factors, but the lack of internal consistency, aggravated by the difficulty of recognizing it. In some cases, external factors are contributing to the healing process, more or less consciously. This was reflected by Pope Francis when he pointed out that the scope of this social and ecclesial upheaval ‘has become known primarily thanks to changes in public opinion’ (Citation2019, no. 96).

What is the role of someone responsible for Church communication in the face of these kinds of crimes or claims? What role does (or can) organizational communication play in the management of this process? The ‘realistic’ model of institutional communication involves connecting identity, action, and discourse; reality, communication, and reputation. Two requirements for the communications management emerge from this:

Healing purpose

Faced with these kinds of crimes (wounds brought about by an organization that in turn leave it wounded itself) there is no room for declarative communication, but primarily curative communication (which repairs the damage caused to the victim, asks forgiveness, restores the Christian value that has been broken, and prevents future cases) and secondarily explanatory communication (shares the thinking of an organization, clarifies what is necessary, avoids rumors, and generates new bonds of trust). Without the healing of the wounded, there is no communicative healing possible for the institutions. Without an act of reparation, the process of communication would lose its consistency.

Integrative approach

Secondly, the connection between each phase of the described model suggests dealing with those cases from an integrative perspective, in which the legal, psychological, spiritual, and communicative aspects are coordinated, because action and communication are two sides of the same coin. According to Griffin’s statement, ‘a crisis is a time for cross-functional working’ (Griffin Citation2014, 230). If communication were isolated or limited to the discourse phase, it would be reduced to mere cosmetics. If it were omitted, the damage and suffering of those affected, from victim down to every last member of the faithful, would be increased exponentially. This is a shared competence: the broad and external vision provided by the communications department can improve all stages of an abuse proceeding, even those that are more exclusively the responsibility of the government, legal services, or other departments.

Starting from these two premises, we suggest some basic attitudes for an effective communication management. We group them around five verbs: investigate, listen, support, repair, and inform. These attitudes are like a natural emanation of the ‘internal’ phases of the communication process described above (identity, culture, and discourse), and have been verified in the task of consulting at the service of various Church institutions that have come to the faculty where the writer of this article teaches.Footnote3 In the exposition, we will use a selection of news articles to illustrate with examples some findings and proposals.Footnote4

3.1. Investigating and listening

The attention to the institutional identity is adherence to its values, but at the same time it implies giving precedence to reality, even when doing so may seem inconvenient. That is why the best guarantee of a communication plan related to these kinds of abuses consists in carrying out, in the best way possible, the preliminary investigation on the alleged facts. From a legal standpoint, rigor in the initial investigation is a guarantee of respect both for the alleged victim and the accused.Footnote5 From the communications standpoint, it expresses with facts that the institution wishes to clarify the truth and avoid self-righteousness.

When the engine is the sincere search for the truth, the best efforts of the team managing the case are focused on the investigation. This is manifested in provisions such as favoring third-party investigations (police, prosecutors, or courts)Footnote6 or working with outside experts, avoiding self-referentiality and enabling learning. Walaski mentions three factors that directly reinforce the credibility and trust of and in the communicating subject: ‘the perceptions of knowledge and expertise, the perceptions of openness and honesty, and the perceptions of concern and care’ (Walaski Citation2011, 22).

On the part of the communications team, it implies remaining calm when the media—in its social function of informing—disseminates the facts under investigation, without feeling assaulted by such news. When working consistently with the institutional identity, what prevails is the search for the common good and the reestablishment of values (the healing of the presumed victim and the reinforcement of preventative mechanisms): the essential thing is still to clarify the facts that generate the news, which can sometimes even help to refine the investigation.

A communications manager who is attentive to the investigation avoids hasty hypotheses. One difficulty is that in those cases the truth unfolds gradually: the data arrives little by little. The danger is offering rushed narratives from an incomplete framework; even if these statements are not made with the intention of covering something up or making a denial, they could give that impression. The wisdom of the communicator is in talking about the case in such a way that the story can grow (the research is ongoing) but not change. That is to say, to share only the verified information at each moment, without confirming or denying matters on which one is not certain, to be guided by prudence, whose foundation is knowledge of reality and not only good intentions. (Pieper Citation1999, 31).

A fundamental contribution of the communications department in the investigation phase is to foresee the future development of the public communication of the case. Ana Gálmez, a Church communicator, expressed it this way in a personal conversation in Santiago de Chile on 12 June 2019: ‘I need to prepare a press release on each one of the steps that are being taken, regardless of whether we have to disseminate it or not; thinking about the need to give a public account improves the investigation process itself and helps things to get done in such a way that they will be easily understood by public opinion in general and not only by the experts involved in the case.’

Attention to the organizational identity implies giving primacy to people, and one relevant way of doing that is through listening. Faced with cases of abuse, this is manifested in actions like encouraging personal interviews with the parties involved and creating an open culture that is receptive to problems and stimulates candor and promotes trust, without fear of reprisals; putting the affected person first, demonstrating sensitivity and respect for his or her pain; putting aside one’s own agendas and concentrating on understanding the other person’s point of view before intervening; validating the person making the claim without the need to automatically validate his or her accusations, which will be subject to later discernment; understanding his or her trauma, which exists independently from the confirmation of the facts; not confusing the complaint with an attack or a desire to take advantage; to commit to helping in the best possible way; recommending to the affected person—when applicable—that he or she submit his or her claim to the competent civil authorities.

An initial attitude of listening facilitates the collaboration of both parties: the claimant and the accused. Von Hildebrand wrote: ‘It cannot be said, properly speaking, that those who have no tears for those things which require tears are living’ (Von Hildebrand 1996, 115, our translation). For this task, it is necessary to have ‘living’ people, who are capable of crying over the pain of others. When we are faced with personal wounds, it is not possible to establish an exclusively procedural relationship, since too much formality diminishes or breaks the trust. To listen is to welcome with humanity, with the help of, for example, psychological experts. The most direct way to listen and be heard is to ‘tune in to the feelings, and not only to the intellect’ (Mastroianni Citation2017, 89).

Along with personal listening, the communications team should also favor institutional listening channels. In the case in question, specifically, this means setting up direct spaces for receiving complaints or claims which are easily accessible on institutional websites and attending to them promptly.Footnote7

Communication enhances the solidity of the investigation, and this, as we said at the beginning, is the best plan of communication: to take each step as seriously as possible and in a way that is consistent with the institutional identity. To give preeminence to the truth. And to do so with an attitude of listening, both personal and institutional, that puts the affected person at the center.

3.2. Supporting and repairing

If the verbs ‘investigate’ and ‘listen’ were natural emanations of the first phase of the organizational communication process, then the actions of ‘support’ and ‘repair’ can summarize the two main expressions of the second phase (culture) as far as abuses are concerned.

Support is prolonged listening in time. Managing abuse cases with a pastoral attitude implies, among other things, that the abused person is informed of the most relevant steps being taken. The arduous inner journey that involved reporting the facts to the authorities calls for an empathetic attitude in order to avoid the alleged victim feeling revictimized by what could be considered a bureaucratic or defensive attitude. This kind of support is the first step toward helping the person move forward. The good of people is key for a communication plan that deals with such deep wounds.

Secondly, support comes to the accused person, who is invited to follow the established protocols to clarify the facts. Although it goes beyond the subject of communication, from a Christian perspective, spiritual support seeks that the accused or guilty party (depending on each case), understands and repents for the harm done, faces the penalties with integrity, avoids despair, finds refuge in the mercy of God, and re-orients his life.

Consistent with the realistic model of communication that we have described, when the facts have been clarified, it is fundamental to respect the duties of justice and to make every effort to repair the damage.

The request for forgiveness ‘includes a confession, a plea for forgiveness, and a promise to make corrections’ (Fearn-Banks Citation2017, 40). Again, words coupled with corrective action, because the result of the healing action ‘is in the delivery, not the promise, so this [the communication effort] will be about showing rather than telling’ (Griffin Citation2014, 236).

In addition to the material and economic reparations established in each case by the justice system or an external mediator accepted by the two sides in play, another concrete mode of reparation is to put appropriate mechanisms into effect so that such events do not happen again, or at least so that they can be stopped and reported as soon as possible. One practice of interest in achieving this is to pay attention to the protocols of action and protection that are followed in at-risk areas: that is, to update them, distribute them, and apply them. It is convenient to develop a positive formative and informative action on how to respond if inappropriate behaviors occur.

For example, in articles 8, 9, and 10 of the Vatican State law of March 26th of 2019 about the protection of minors and vulnerable persons, these kinds of measures are established, including a ‘support service’ and a training service to learn to identify and prevent these offenses among the citizens of its small territory.

Another interesting example is the decalogue for dealing with possible cases of sexual abuse (‘Decálogo para afrontar posibles casos de abuso sexual’) promoted by the Federation of Spanish Catholic Religious Schools. Each partner school distributes it to teachers, students, and families, and it is available to everyone on the website. It took a remarkable effort to say so much on one page.Footnote8

Pope Francis calls for ‘the determination to apply the actions and sanctions that are so necessary (…) And all this with the grace of Christ. There can be no turning back’ (Pope Francis Citation2019a, 97). And in the Apostolic Letter Vos Estis Lux Mundi, he states: ‘In order that these phenomena, in all their forms, never happen again, a continuous and profound conversion of hearts is needed, attested by concrete and effective actions that involve everyone in the Church, so that personal sanctity and moral commitment can contribute to promoting the full credibility of the Gospel message and the effectiveness of the Church’s mission’ (Pope Francis Citation2019b).

3.3. Informing

In the third phase (the one we called ‘discourse’), the consistency between being, acting, and saying, calls for an informative attitude with an open and transparent approach.Footnote9 The opposite of this is the mentality of ‘avoiding scandal’ that has been wrongfully established in the praxis of many institutions and that has sometimes encouraged the justification of falsehood and manipulation.

In cases of verified abuse, the organization (as well as the victim) feels that its identity is threatened, and needs to make a public statement about a way of doing things that hurts it inside and out, especially during some of the watershed moments in the process.Footnote10 From this realistic perspective, communication should be framed in the healing process, asking for forgiveness and strengthening preventative measures and the creation of safe environments (Alazraki Citation2019).

The above is compatible with a responsible reflection on the conflict between privacy and openness (Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops 2018, 69–70). Sometimes it is necessary to redirect two opposing situations: the fear that a case that has not yet been verified will reach the realm of public opinion or, on the contrary, the rush to publicize it as a defense mechanism. In this dilemma, it seems necessary not to rush to inform, but rather to wait until one one has all the facts, and at the same time to adapt to the level of publicity requested by the claimant (sometimes they ask for disclosure, and other times they expressly ask that their privacy to be respected: this is how the Holy See acts, for example, when the Pope meets with victims). Of course, it is always necessary to comply with the different laws in each country or region (in some jurisdictions, for example, disclosure is required at the moment the claim is reported, whereas others require that the investigation or trial be concluded firstFootnote11). In sum, depending on the claimant, it is necessary to determine the balance between what constitutes the duty to inform and the ethical requirement to avoid defamation, especially while the process is still ongoing.

In connection with the phase of the discourse (‘informing’) we suggest seven criteria that can help to promote just, professional, and transparent communication. They are a natural result of the theoretical framework described above and the outcome of a dialogue of the author of this article with four communications professionals who—like him—have collaborated in the communication management of various casesFootnote12:

3.3.1. A perspective of the whole

Although the public discourse evolves as the investigation progresses, each piece of information generated by the institution must offer context and reveal the following: the facts and their place in the general abuse crisis; the parameters that guide the management of the case and its consequences (the priority of persons, commitment to the truth, etc.); the feelings of the organization (sorrow, compassion, grief, regret); the measures taken with the person under investigation and with those affected; the modes of referring information that may enhance the investigation; mention of the institution’s prevention and reporting protocols; and other possible measures (for example, a revision of the protocols, if applicable).

When preparing the texts, tension can arise in the institution between opposing sensibilities: those who suspect laxness (it seems to them that not enough is being done) and those who distrust harsh chastisement. Both extremes are ways of putting the organization above the person. In this sense, the view of the whole implies that each communication expresses the whole of the identity, not just a part of it (for example, that it expresses both justice and mercy).

A perspective of the whole also means offering the information in its proper spatial and temporal context (it is not the same to report on a case from fifty years ago as it is to report on one that took place five, ten, or twenty years ago: in this time-frame society has greatly evolved on the very concepts of abuse or minors, how to perceive and respond to this kind of crime, etc.). Nor should the social context be overlooked, since this painful sequence of events affects every sphere of society (this contextualization is not to divert or blur responsibility, but to avoid the majority of victims getting silenced because nobody talks about their problem: the communicator of the Church keeps in mind the good of the victims, since it would be unjust to think of some and forget the others).

3.3.2. Proximity

It is critical that internal and external communication develop side-by-side and harmoniously. A good experience is to work in concentric circles: inform the people closest to you, who are usually the most affected by this news and who will have to answer questions in their relational environments, earlier and more thoroughly. This allows us to better express the feelings and values with which we face each case, and to follow a natural order in communication. When faced with this type of news, ‘communication with internal publics before, during, and after a crisis is vital’ (Fearn-Banks Citation2017, 68).

Moreover, the ‘internal’ information about an abuse case has, in a certain sense, a pedagogical function with respect to the community in which the events have taken place: the parish, the diocese, the institution. And it can give it more responsibility in the fight against and prevention of abuses, as Pope Francis said in his ‘Letter to the People of God’ of 20 August 2020.

3.3.3. Specificity

When choosing words, keep in mind the phase that the case is currently in (investigation, discovery, trial, sentence, or appeals) and refer to the facts and people as ‘alleged,’ ‘possible,’ ‘investigated,’ ‘accused,’ ‘claimant,’ ‘victim,’ ‘affected,’ etc. Understand the laws of each country in which ‘sexual abuse’ and ‘harassment’ have different meanings. These notes can be seen in the articles selected as the foundation for this reflection.

Another aspect of accuracy in informing is to clearly distinguish the legal record from the moral record, which are inevitably intertwined. Sexual abuse is both a crime and a sin. Both dimensions are important, and neither should be ignored, especially in the Church’s internal communication. However, to avoid confusion and misinterpretation it is helpful to make the record explicit when the communication situation requires it.

3.3.4. Graduality

Strive to make the facts of the claim clear (physical and psychological harassment, actions with a sexual connotation, touching, rape, etc.). There are degrees in the moral and penal evaluation of each situation, and it would be unjust to allow public opinion to always assume the worst, or on the contrary, to diminish the seriousness of the facts of the claim with ambiguity in the language used.

Precision and a graduated approach are key in communicating the different ecclesial sanctions with which abusers are punished. In these cases, it is necessary to keep in mind the different degrees of crimes and sins (emphasizing that all of them are obviously serious) to which correspond different degrees of punishment.

3.3.5. Proportionality

Each case has a natural area of influence (a province, a country, a linguistic region, etc.) that it makes sense to respect when distributing communications or other materials. The opposite would denote inattention to the personal trauma of those involved and could be seen as a display of transparency, thus making it an end in itself and putting the organization above the people.

At the same time, because the Church is a universal institution, it sometimes happens that local news takes on global resonance; what happens in another country can have an impact on mine and can influence the interpretive framework and attitude of the people around me. It is important not to ignore this reality when managing this kind of information.

3.3.6. Sensitivity

Inform by giving priority to the victim or claimant. This order shows that the main concern of the institution is the person harmed. This implies calm in the face of possible harsh reactions, understanding that they can be a result of the pain suffered.

People’s reputations are a good that has great social importance, and its destruction ‘may deprive the subject of social cooperation, destroying him psychologically and economically’ (Rodríguez Luño Citation2014, 29, our translation). And the book of Proverbs reminds us that ‘A good name is more desirable than great riches, and high esteem, than gold and silver’ (Proverbs 22:1). These considerations invite us to be sensitive in our communication of the facts under examination, and to look for formulas that also combine transparency and respect for the dignity of the inquirer. On the other hand, in complex processes it can happen that the reputation of the claimant is damaged, because of smear campaigns, people choosing sides, and the claimant’s intentions being questioned. In these cases, the culture of the Church organizations should prevent one from entering into that dynamic, but rather to act in accordance with the principles set forth above: truth, pastoral attitude, etc.

3.3.7. Initiative

The evolution of the case sometimes results in new approaches, interviews, or the appearance of associated problems, which will require a response: this involves taking the initiative even in the sphere of information, alongside the process, moving forward when necessary, as can be seen in some of the selected clippings. In this aspect too there is a natural order that begins with those closest to us, especially if they will be affected by a change in a parish priest, the closure of a school, or other measures that impact their daily lives. For the preparation of the spokespersons, a good practice is to write up a document of questions and answers about the ambiguous or most complicated parts of the case. This document is constantly evolving, expanding, and being revised. An attitude of transparency towards the outside depends very much on clarity on the inside: having answers on the inside is part of the way to seriously inform others.

Openness is ultimately transparency: opening the doors, making it possible for different concerned parties to verify that what we are saying is true and genuine.

4. Conclusion

All organizations deal with vulnerability over the course of their history, both in the passive sense and the active sense. The Church, in her most visible, human, and institutional dimension, shares fallibility with every other organization involved in social activity.

The communication management of institutional errors and fragility raises questions about the very purpose of the organizations’ communicative activity. In this sense, we find valid insights in ‘realistic’ communicative paradigms such as the one described in the previous pages. When we face institutional error, it seems especially necessary to establish communication modalities based on the adherence to reality and that have the potential to correct inconsistencies between identity (mission, vision, and values), corporate culture (action), and discourse (words).

The tragedy of the abuse of minors by ministers of the Catholic Church is an unprecedented crisis of legitimacy that challenges those who are dedicated to organizational communication, to whom this article is primarily addressed.

As in any scenario of vulnerability, the acceptance of the terrible reality of the abuses is an unavoidable condition for reconnecting with the heart of the Gospel. During his visit to Chile in January of 2018, Pope Francis recalled: ‘A Church with wounds can understand the wounds of today’s world and make them her own, suffering with them, accompanying them and seeking to heal them’ and thus ‘to pass from being a Church of the unhappy and disheartened to a Church that serves all those people who are unhappy and disheartened in our midst’ (Pope Francis Citation2018).

From a realistic perspective—connected to the identity and mission of the Church—the communication management of this kind of situation should be carried out with a healing purpose and an integrative approach. The communications department collaborates in all stages of a proceeding for abuse (even those that are more exclusively the responsibility of the government, legal services, or other departments) in order to seek the healing of victims and, secondarily, to restore the trust of the various parties involved. Any communication conceived as an end in itself would remain merely cosmetic.

When the communication function is put in the service of healing, rather, it is performed in activities that are beyond the narratives but that are at the base of the task of informing: inquiring, listening, supporting, repairing, and preventing. These are attitudes and actions that are directed toward people who have suffered the consequences of abuse and, at the same time, are the main way to renew the link of the institution with the essential principles of its identity: respect for the dignity of every human being, the desire to promote safe environments for young people, the love of truth, etc. They are attitudes that heal wounds, purify, and redirect towards better service to people. The drastic reduction of the number of claims of abuse in the countries that have followed such guidelines (such as Ireland or the United States) is a good indicator.

When healing is put at the center, it becomes natural to inform with transparency, even when it might seem inconvenient for the institution. In this task it is advisable to act with the victim or complainant in order to determine the balance between what constitutes the duty to inform, the respect for his or her privacy, and the ethical requirement to avoid defamation, especially while the enquiry is still ongoing. Informing fairly and justly is easier if, in addition, the institution offers a broad and contextualized interpretation of the case (perspective of the whole), if it maintains priority lines of communication with the most closely concerned parties (proximity), if it uses appropriate language in the description of various situations (specificity), if it takes into account the particular moral assessment of each case (a graduated approach), if it respects the natural area of influence of each complaint or investigation (proportionality), if it ensures that every communicative act preserves the dignity of those involved (sensitivity), and if it remains open and attentive to the evolution of the case, so as to know how to lead in the sphere of information, which runs parallel to the process (initiative).

One essential aspect that emerges from the process of organizational communication and that is fundamental in the communication of ‘wounds’ is that of the preeminence of action, the common thread of the previous reflections. This is how one scholar of trust puts it: ‘Good words have their place. They signal behavior. They declare intent. They can create enormous hope. And when those words are followed by validating behavior, they increase trust, sometimes dramatically. But when the behavior doesn’t follow or doesn’t match the verbal message, words turn into withdrawals’ (Covey Citation2018, 197). In such cases, ‘the answer might be in better actions rather than better words’ (Griffin Citation2014, 236). The communication function has value insofar as it contributes to the quality of actions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Marco Carroggio

Marco Carroggio is an Associate Professor at the School of Church Communications of the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross. He teaches Organizational Communications and Management.

Notes

1 The last two decades have seen the rise of, for example, the School of Church Communications at the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross (founded in Rome in 1995), the university course Comunicación y Religión en la Era Digital (Communication and Religion in the Digital Era) for religious communicators organized by Blanquerna, at the Universitat Ramon Llull (in Barcelona in 2004) or various certificates of specialization in the web, such as the Diplomatura en comunicación de la Iglesia (Diploma in Church Communication) promoted jointly by Meraki and the Universidad Católica de Cuyo (in San Juan de Cuyo in 2014), among others.

2 In 1971 the Holy See published the pastoral instruction Communio et Progressio, which was drawn up based on a mandate from the Second Vatican Council. This document contains a specific call to foster the function of media relations in the ecclesial organizations: “Every bishop, all episcopal conferences or bishops’ assemblies and the Holy See itself should each have their own official and permanent spokesman or press officer to issue the news and give clear explanations of the documents of the Church so that people can grasp precisely what is intended. These spokesmen will give, in full and without delay, information on the life and work of the Church in that area for which they are responsible. It is highly recommended that individual dioceses and the more weighty Catholic organizations also have their own permanent spokesmen with the sort of duties explained above” (PCSC 1971, no. 22).

3 In this task of consultation and in the subsequent systemization, the help of my colleagues Rodrigo Ayude and Jaime Cárdenas (both from the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross, Rome, Italy) and Juan Pablo Cannata (Universidad Austral, Buenos Aires, Argentina) has been invaluable.

4 As support for this part, we reviewed the information on abuse in the Catholic Church published in five different journals during the period of January-June 2019: The Irish Times (Ireland), El Mercurio (Chile), Corriere della Sera (Italy), The New York Times (United States), and El País (Spain). Three fundamental criteria were taken into account in selecting journals: a) that they were the leading general information newspaper in their respective country; b) that they belonged to areas of with a broad Catholic tradition in which numerous cases of abuse had been recorded; c) they were accessible with a basic subscription with the Meltwater monitoring tool, which facilitates analysis and direct consultation of the texts. The resulting number of journalistic pieces was 76. The tool used was www.meltwater.com, a paid service that collects and analyzes the publications why underlined? I don't think it's necessary in the most relevant online information portals in the world. In addition to the traditional service of clipping, it offers useful resources for the analysis of users’ digital behavior.

5 Some elements that ensure quality include: documenting the complaint with the signature of the accused and, if possible, of a third party that certifies the declaration; diligently applying and documenting the steps of public protocol, informing the affected parties of the steps being taken, etc.

6 In this area, for example, the new provisions appropriated by the USCCB to make it easier to report any bishops suspected of abuse or cover-up, as explained in one of the articles in the above-mentioned selection: The New York Times (United States, 13 June 1019). Accessed 28 May 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/13/us/catholic-bishops-abuse.html (Cf. also Erlandson, Citation2019).

7 The Apostolic Letter “Vos Estis Lux Mundi” formally states that the dioceses, eparchies, and other ecclesiological bodies institute “one or more stable and easily accessible systems for reporting” and making claims (Pope Francis Citation2019b, 1). One of the selected news articles (Corriere della Sera, Italy, 9 May 2019) refers precisely to the obligation imposed by the Holy See to have a public office for handling claims. Accessed 28 May 2020. https://roma.corriere.it/notizie/cronaca/19_maggio_09/pedofilia-motu-proprio-papa-francesco-obbligo-segnalare-abusi-4854b41e-7242-11e9-861b-d938f88a2d19.shtml

8 El País has a write-up about it. Accessed 28 May 2020. https://elpais.com/sociedad/2019/03/18/actualidad/1552920699_534077.html

9 One of the selected articles refers to this transparency (The Irish Times, Ireland, 19 February 2019), in which the Cardinal Primate of that nation connects it to the pain of the victims. Accessed 28 May 2020. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/social-affairs/religion-and-beliefs/catholic-primate-says-abuse-survivors-rightly-demand-church-transparency-1.3799657.

10 Three instances of special notoriety in which it may be appropriate to provide official information are: a possible information leak at any time (even unknown to the institution); the launching of an investigation (the intention of the publication is then mainly to invite the participation of possible persons who can provide further evidence, when it is presumed that there may be others affected); the concluding of an investigation and the measures to be taken by the institution.

11 In one of the selected press clippings, for example, we can see how an institution informs people about the opening of the investigation based on a complaint with possible sexual connotations, thus facilitating the arrival of new elements for the investigation, a guarantee for both the denouncer and the accused (El Mercurio, Chile, 1 February 2019). Accessed 28 May 2020. https://www.emol.com/noticias/Nacional/2019/02/01/936418/Prelatura-del-Opus-Dei-informa-que-recibio-dos-denuncias-en-contra-un-sacerdote-de-la-congregacion.html.

12 In addition to the already mentioned Rodrigo Ayude (Pontifical University of the Holy Cross) and Juan Pablo Cannata (Universidad Austral), the following professionals also participated in the discussion: Piotr Studnicki (Coordinator of the Office for the Protection of Minors of the Polish Bishops’ Conference) and Thierry Bonaventura (Media officer at the Council of European Bishops Conferences, from 2005 to 2018).

References

- Alazraki, Valentina. 2019. “Comunicación: para todas las personas,” Speech to the Summit on the Protection of Minors in the Church. February 23. Accessed 28 March 2019. http://www.vatican.va/resources/resources_alazraki-protezioneminori_20190223_sp.html

- Arriagada, Eduardo. 2016. “Dialogare Sui Valori Nelle Reti Sociali.” In Missione Digitale. Comunicazione Della Chiesa e Social Media, edited by G. Tridente and B. Mastroianni. Roma: Edusc. 111–134.

- Böhm, Bettina, Hans Zollner, Jörg M. Fegert, and Hubert Liebhardt. 2014. “Child Sexual Abuse in the Context of the Roman Catholic Church: A Review of Literature from 1981–2013.” Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 23 (6): 635–656. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2014.929607.

- Campbell, Heidi. 2020. “The Distanced Church.” In Reflections on Doing Church Online, edited by Heidi Campbell. Texas: Digital Religion Publications.

- Carroggio, M., F. Gagliardi and B. Mastroianni. 2013. “La Relazione Con i Media.” In L’ufficio Stampa Delle Istituzioni Senza Scopo di Lucro, edited by Heidi Campbell. Roma: Aracne.

- Carroggio, Marc. 2016. “Lo Scenario Digitale: una Comunicazione a Cerchi Concentrici.” In Missione Digitale. Comunicazione Della Chiesa e Social Media, edited by Giovanni Tridente and Bruno Mastroianni. Roma: Edusc. 19–39.

- Catechism of the Catholic Church. 1993. Vatican: Libreria Editrice Vaticana.

- CCCB (Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops). 2018. Protecting Minors from Sexual Abuse. Ottawa: CCCB.

- Covey, Stephen M. 2018. The Speed of Trust: The One Thing That Changes Everything. New York: Free Press.

- De la Cierva, Yago. 2014. La Iglesia, Casa de Cristal. Madrid: BAC.

- De la Cierva, Yago. 2018. Scenari di Crisi Nella Chiesa: Esercizi per la Prevenzione, la Pianificazione e il Training di Comunicatori Ecclesiali. Roma: Aracne.

- Díez, M., and P. Soukup. 2017. Authority and Leadership: Values, Religion, Media. Barcelona: Fundació Blanquerna.

- Erlandson, Greg. 2019. “Bishops take another try at addressing abuse, accountability among their own.” Catholic News Service, July 6. Accessed 13 March 2020. https://www.catholicnews.com/services/englishnews/2019/bishops-take-another-try-at-addressing-abuse-accountability-among-their-own.cfm

- Fearn-Banks, Kathleen. 2017. Crisis Communications: A Casebook Approach. 5th ed. New York: Routledge.

- Gregory, Anne, and Paul Willis. 2013. Strategic Public Relations Leadership. London: Routledge.

- Griffin, Andrew. 2014. Crisis, Issues and Reputation Management. London: Kogan Page Limited.

- Haslam, Alexander. 2015. Psicologia Delle Organizzazioni. Romagna: Maggioli.

- Macintyre, Alasdair. 2001. Animales Racionales y Dependientes. Barcelona: Paidós.

- Manson, Mark. 2020. “Vulnerability: The Key to Better Relationships.” Accessed 8 June 2020. https://markmanson.net/vulnerability-in-relationships.

- Mastroianni, Bruno. 2017. La Disputa Felice. Firenze: Franco Cesati Editore.

- Mora, Juan Manuel. 2006. “Dirección Estratégica de la Comunicación en la Iglesia.” Communication & Society 19 (2): 165–184.

- Mora, Juan Manuel. 2015. “Cultivar la Reputación Con Ayuda de la Comunicación.” In El Futuro de la Comunicación, edited by Elena Gutiérrez and Jordi Rodríguez Virgili. Madrid: Lid.

- Mora, Juan Manuel. 2020. El Valor de la Reputación. Pamplona: Eunsa.

- Nieto, Alfonso. 2006. Economia Della Comunicazione Istituzionale. Milano: Franco Angeli.

- Ohu, Eugene Agboifo. 2016. “Cultural Intelligence Sounding the Death Knell for Stereotypes in Business Communication.” Global Advances in Business and Communications Journal 5 (1): 1–26. Accessed 20 November 2020. http://commons.emich.edu/gabc/vol5/iss1/2.

- PCSC (Pontifical Council for Social Communications). 1971. “Communio et Progressio.” Document On the Means of Social Communication. Written by Order of the Second Vatican Council. May 23. Accessed 8 March 2019. http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/pontifical_councils/pccs/documents/rc_pc_pccs_doc_23051971_communio_en.html

- Pérez López, Juan Antonio. 2006. Fundamentos de la Dirección de Empresas. Madrid: Rialp.

- Pieper, Josef. 1999. La Prudenza. Brescia: Morcelliana.

- Pope Francis. 2014. “Presentation of the Christmas Greetings to the Roman Curia.” December 22. Accessed 12 January 2020. http://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/speeches/2014/december/documents/papa-francesco_20141222_curia-romana.html

- Pope Francis. 2018. “Apostolic Journey to Chile: Meeting with Priests, Consecrated Men and Women, and Seminarians, Cathedral of Santiago.” January 16. Accessed 5 January 2020. http://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/speeches/2018/january/documents/papa-francesco_20180116_cile-santiago-religiosi.html

- Pope Francis. 2019a. “Christus Vivit.” Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation to Young People. March 25. Accessed 5 January 2020. http://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/apost_exhortations/documents/papa-francesco_esortazione-ap_20190325_christus-vivit.html

- Pope Francis. 2019b. “Vos estis lux mundi.” Letter in the form of Motu Proprio. May 7. Accessed 7 January 2020. http://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/motu_proprio/documents/papa-francesco-motu-proprio-20190507_vos-estis-lux-mundi.html

- Pope Francis. 2020. “Extraordinary Moment of Prayer in time of pandemic.” March 27. Accessed 7 January 2020. http://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/homilies/2020/documents/papa-francesco_20200327_omelia-epidemia.html

- Pope John Paul II. 1990. “Redemptoris Missio. On the permanent validity of the Church's missionary mandate.” December 7. Accessed 12 January 2020. http://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_jp-ii_enc_07121990_redemptoris-missio.html

- Pope John Paul II. 1994. “Tertio Millennio Adveniente.” Apostolic Letter on Preparation for the Jubilee of the Year 2000, November 10. Accessed 17 January 2020. https://w2.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_letters/1994/documents/hf_jp-ii_apl_19941110_tertio-millennio-adveniente.html

- Pope John Paul II. 2002. “Meeting with the US cardinals,” Rome, April 23. Accessed 20 November 2020. http://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/speeches/2002/april/documents/hf_jp-ii_spe_20020423_usa-cardinals.html

- Rodríguez Luño, Ángel. 2014. Diffamazione. Roma: Edusc.

- Schein, Edgar. 2004. Organizational Culture and Leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Van Riel, C. B., and Charles Formbrun. 2007. Essentials of Corporate Communication. New York: Routledge.

- Vatican Council II 1964. “Lumen Gentium.” Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, November 21. Accessed 9 March 2020. http://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_const_19641121_lumen-gentium_en.html

- Von Hildebrand, Dietrich. 1996. The Heart. South Bend: St. Augustine’s Press.

- Walaski, Pamela. 2011. Risk and Crisis Communications: methods and Messages. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.